1. Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally, with projections estimating over 2 million new cases annually by 2035, driven by factors such as smoking, environmental exposures, and genetic predisposition [

1]. Early detection significantly enhances survival outcomes, with the five-year survival rate for non-small cell lung cancer rising from 5% in advanced stages to nearly 60% when diagnosed at Stage I [

2]. However, conventional diagnostic approaches, such as low-dose computed tomography (CT) scans and biopsies, frequently fail to detect early-stage disease, exhibiting high false-positive rates and imposing substantial patient burden [

3]. Consequently, there is an urgent need for non-invasive, precise methods to improve early detection and patient prognosis. Metabolomics, the comprehensive analysis of small-molecule metabolites in biofluids like plasma, offers a promising strategy for identifying early metabolic dysregulations linked to lung cancer, including altered amino acid and energy metabolism [

4,

5]. Specific metabolites, such as glycine, serine, glutamine, and lipids like sphingosine and phosphorylcholine, have emerged as potential biomarkers, reflecting tumor-driven changes in cellular proliferation and membrane synthesis [

6,

7]. Despite its potential, the high-dimensional and intricate nature of metabolomic data poses challenges for traditional machine learning techniques, necessitating advanced analytical tools [

8]. Recent advancements in Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have proven effective in modeling relational data, making them ideal for capturing complex interactions within biological systems, such as those between patients, metabolites, pathways, and diseases [

9,

10,

11,

12]. GNNs have been applied to multi-omics data for cancer prognosis and subtype classification, including lung cancer [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, their application in metabolomics-driven early detection remains largely unexplored, even with the enriched relational context provided by databases like the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) [

18].

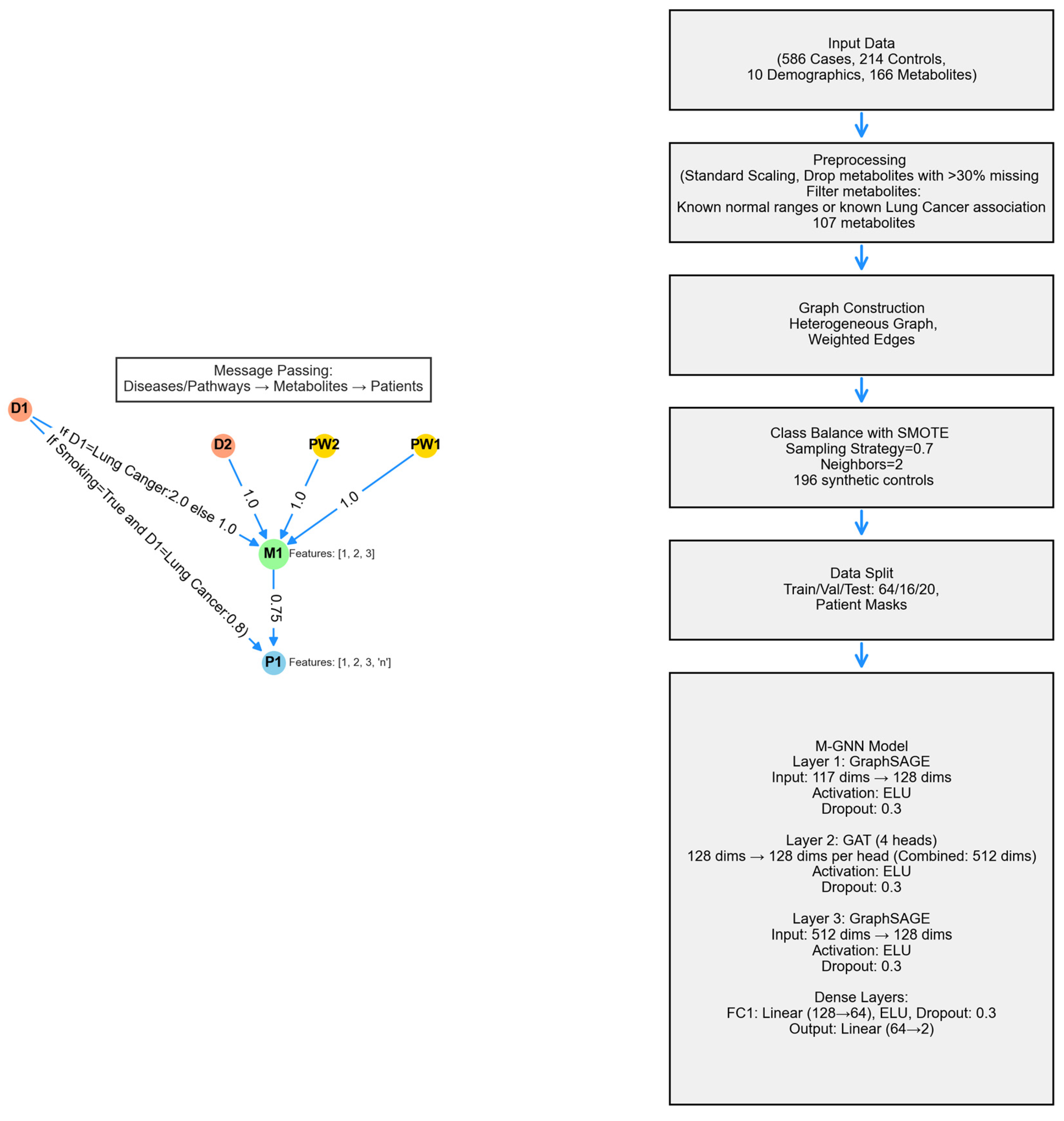

This study presents M-GNN, a graph neural network framework developed for the early detection of lung cancer. The framework makes a complex graph from metabolomics data, which includes 800 plasma samples (586 cases and 214 controls), combining metabolite expression levels with patient features and enhanced with HMDB annotations. GraphSAGE and Graph Attention Network (GAT) layers were utilized to enable inductive learning, aiming to improve predictive accuracy and identify significant metabolic predictors [

9,

19]. Building on previous metabolomics research [

20,

21,

22,

23], this approach offers a scalable and interpretable tool for precision oncology. Our work seeks to advance lung cancer screening, contributing to improved survival rates and personalized treatment strategies.

2. Results

Patient indices were split with random seeds to ensure robustness into 80% training+validation and 20% testing, with the former subdivided into 80% training and 20% validation (64/16/20 split), and masks intersected with a patient mask (

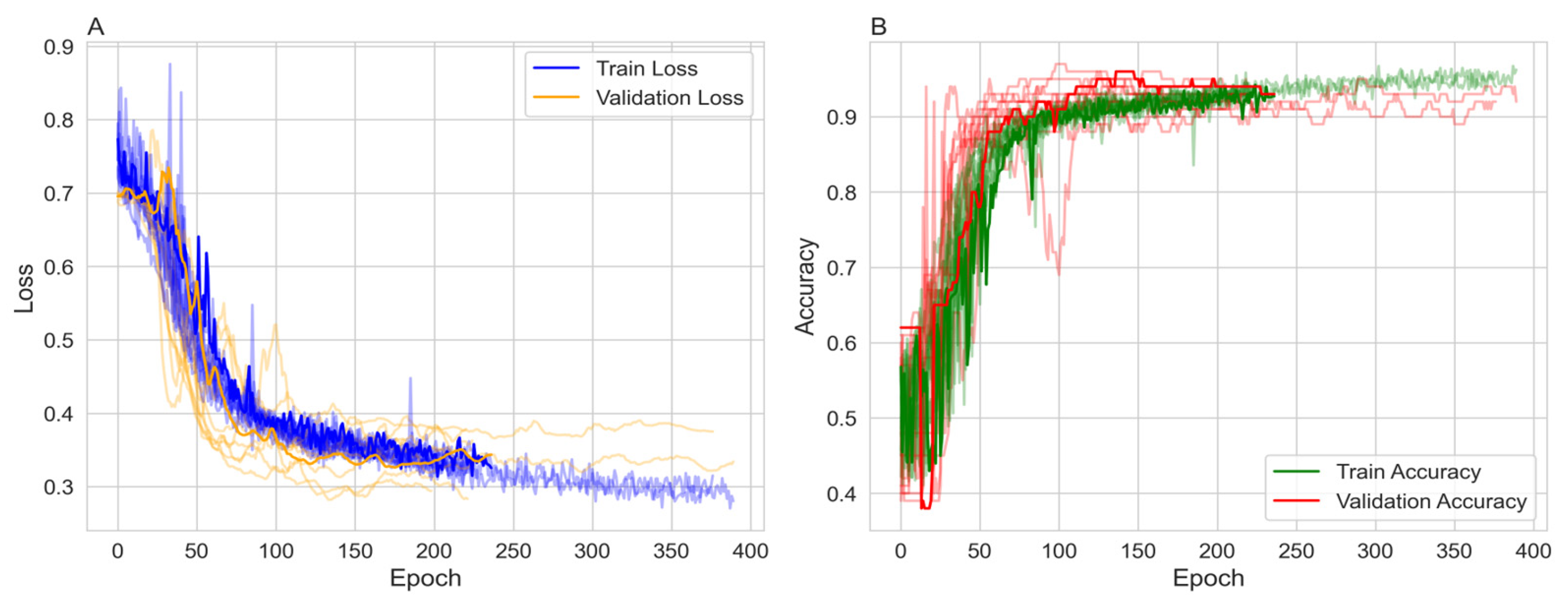

) to focus on labeled patient nodes only. Class imbalance was addressed using the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) with a sampling strategy of 0.7 and 2 neighbors, increasing the minority class from 214 to 410. To ensure robustness the model was run over ten random seeds, each with a different data split. The model was trained over 1,000 epochs with early stopping. The majority of the 10 runs stopped between 170 and 386 epochs and reached stable training and validation accuracies ranging from 89% to 95% (

Figure 1).

Figure 1A shows the training and validation loss. Both losses decrease over time, with the training loss exhibiting more variability but stabilizing around 0.3 to 0.4. The validation loss decreases more smoothly, also stabilizing in a similar range, indicating effective learning without significant overfitting in terms of loss.

Figure 1B presents the training and validation accuracy, both of which increase over epochs. The training accuracy reaches approximately 90% to 95%, while the validation accuracy reaches around 0.89 to 0.95, with some fluctuations. The higher training accuracy after 200 epochs suggests a degree of overfitting, although the validation accuracy remains high.

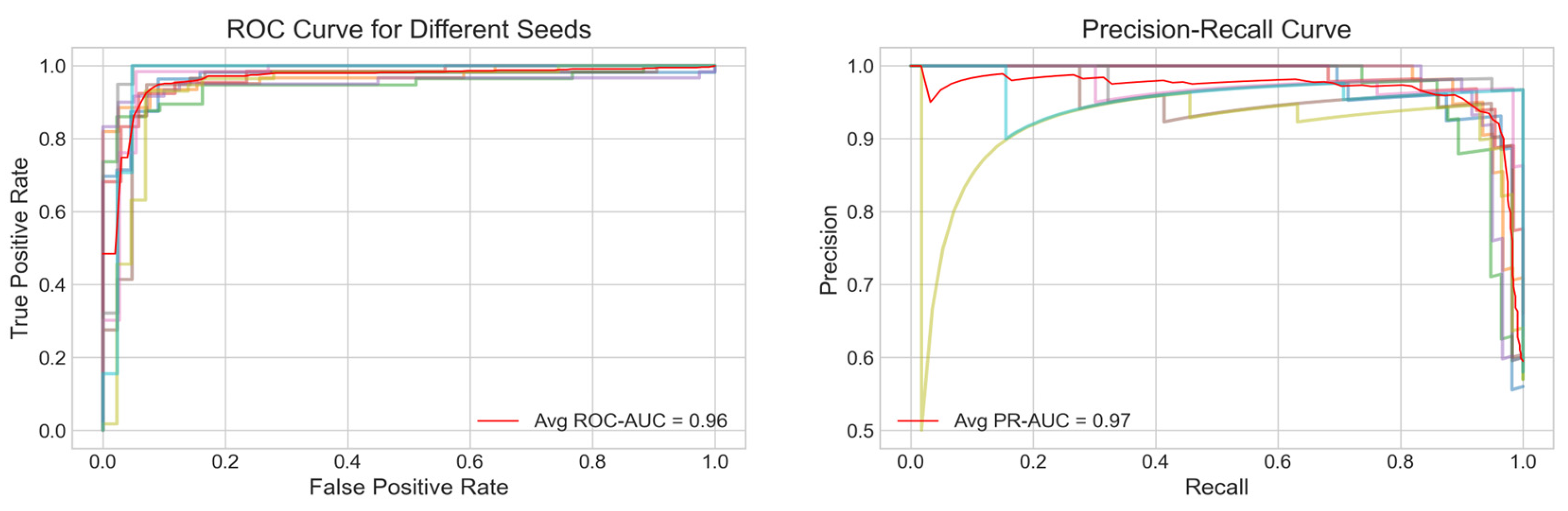

The performance of the model was evaluated using several metrics, including the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, Precision-Recall (PR) curve, accuracy and F1 score.

Figure 2A displays the average ROC curve across the ten trials, achieving an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.96 indicating a strong discriminatory power of the model. Similarly,

Figure 2B presents the average PR curve with a PR AUC of 0.97, demonstrating high precision and recall balance, which is particularly important for imbalanced healthcare datasets.

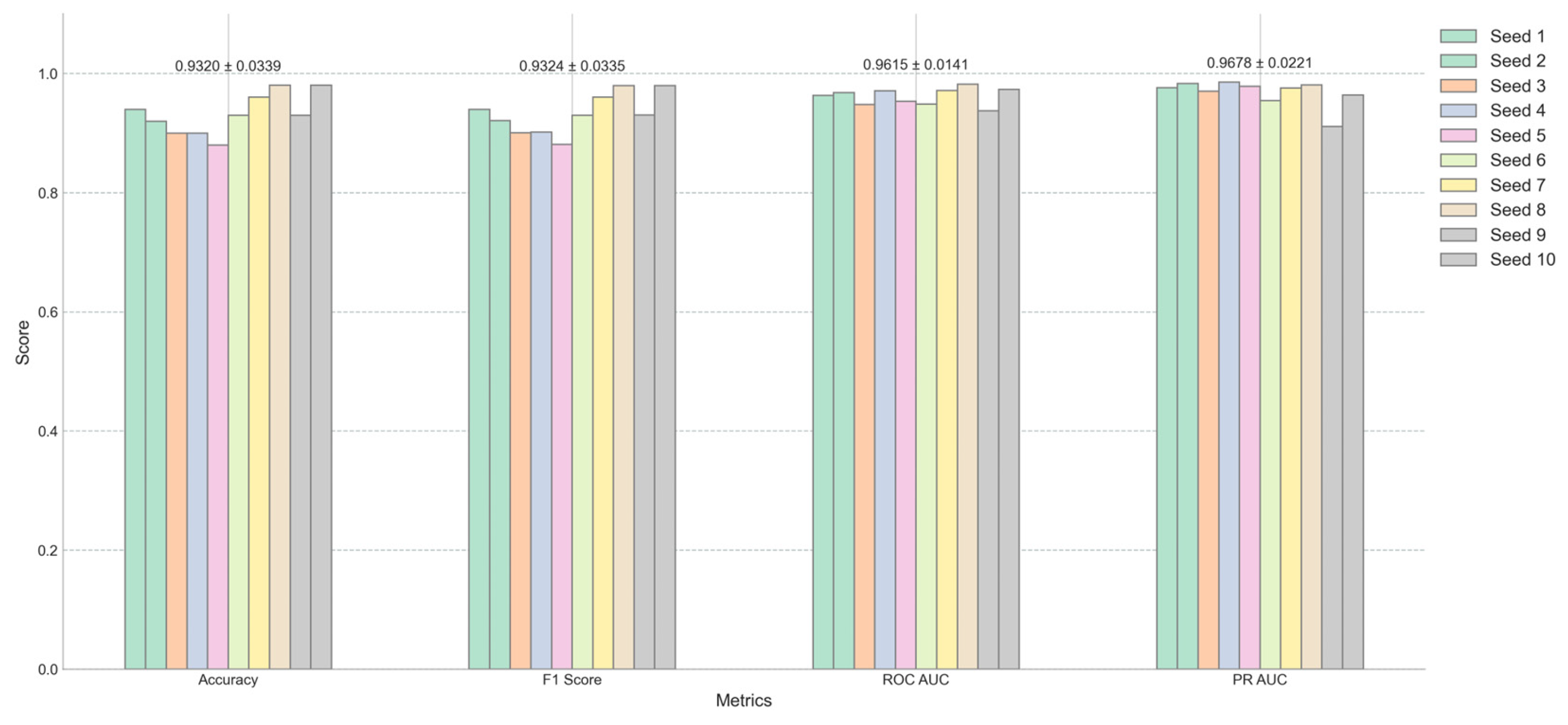

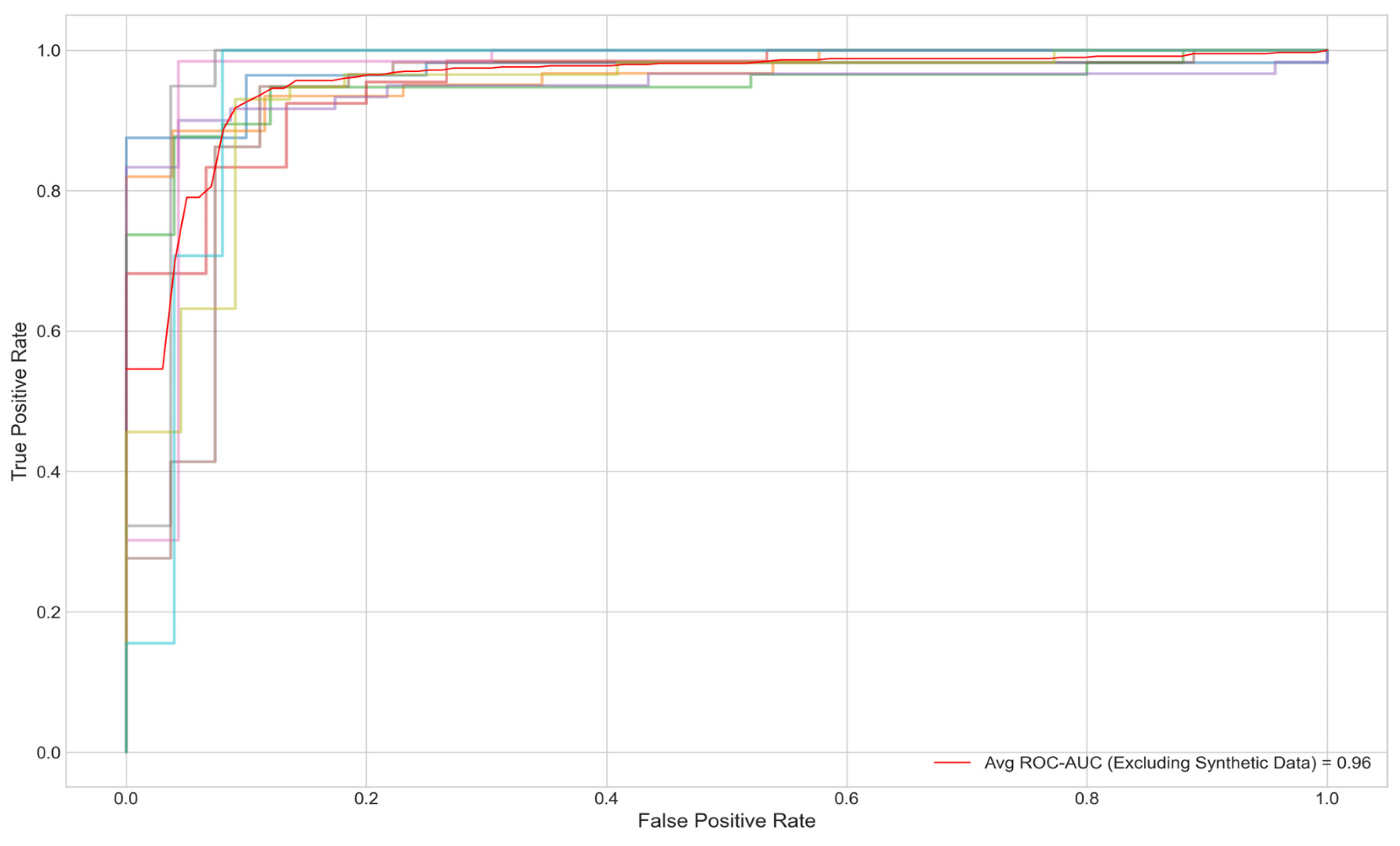

Figure 3 offers a detailed view of the model’s performance across different random seeds for four key metrics: Accuracy, F1 Score, ROC AUC, and PR AUC. The average scores and their standard deviations, as annotated above each group, are as follows: Accuracy is 0.9320±0.0339, F1 Score is 0.9324±0.0335, ROC AUC is 0.9614±0.0141, and PR AUC is 0.9678±0.0221. The small standard deviations for ROC AUC and PR AUC suggest that the model’s performance is consistent and robust across different initializations. Furthermore, when synthetic minority class data was excluded from the test set, the AUC remained at .95% (

Figure 4).

Overall, the results demonstrate that the model achieves high performance across multiple metrics, with robust and consistent results across different random seeds. The training process shows effective learning, with some indications of overfitting that may warrant further regularization or early stopping strategies. The M-GNN methodology provides a comprehensive and integrative framework that effectively captures the intricate interplay among patient-specific metabolite expression, biological pathways, and disease associations. By constructing a heterogeneous graph enriched with HMDB-derived features and leveraging a multi-layer GraphSAGE architecture, the framework not only models fine-grained metabolic details but also contextualizes these within broader metabolomic networks. This robust multilayered approach underscores the potential of this approach to deepen our understanding of metabolic dysregulation in lung cancer and pave the way for enhanced precision in clinical diagnostics and targeted therapeutic strategies.

3. Discussion

The varying connectivity patterns between node pairs play a crucial role in modeling metabolic interactions. Patient-metabolite connections follow a one-to-one structure, ensuring a direct mapping of metabolic activity, while metabolite-pathway and metabolite-disease relationships exhibit a one-to-many nature, reflecting the broader complexity of metabolic networks. The one-to-many relationships observed in metabolite-pathway and metabolite-disease connections highlight the intricate roles metabolites play in multiple biological processes. These associations, as annotated in the HMDB, emphasize the interconnected nature of metabolic pathways and disease states, which are critical for understanding disease mechanisms. By leveraging this structural diversity, M-GNN effectively captures both individual patient-metabolite interactions and the broader relational context of metabolic pathways and diseases. This dual-level representation enhances the model’s predictive accuracy.

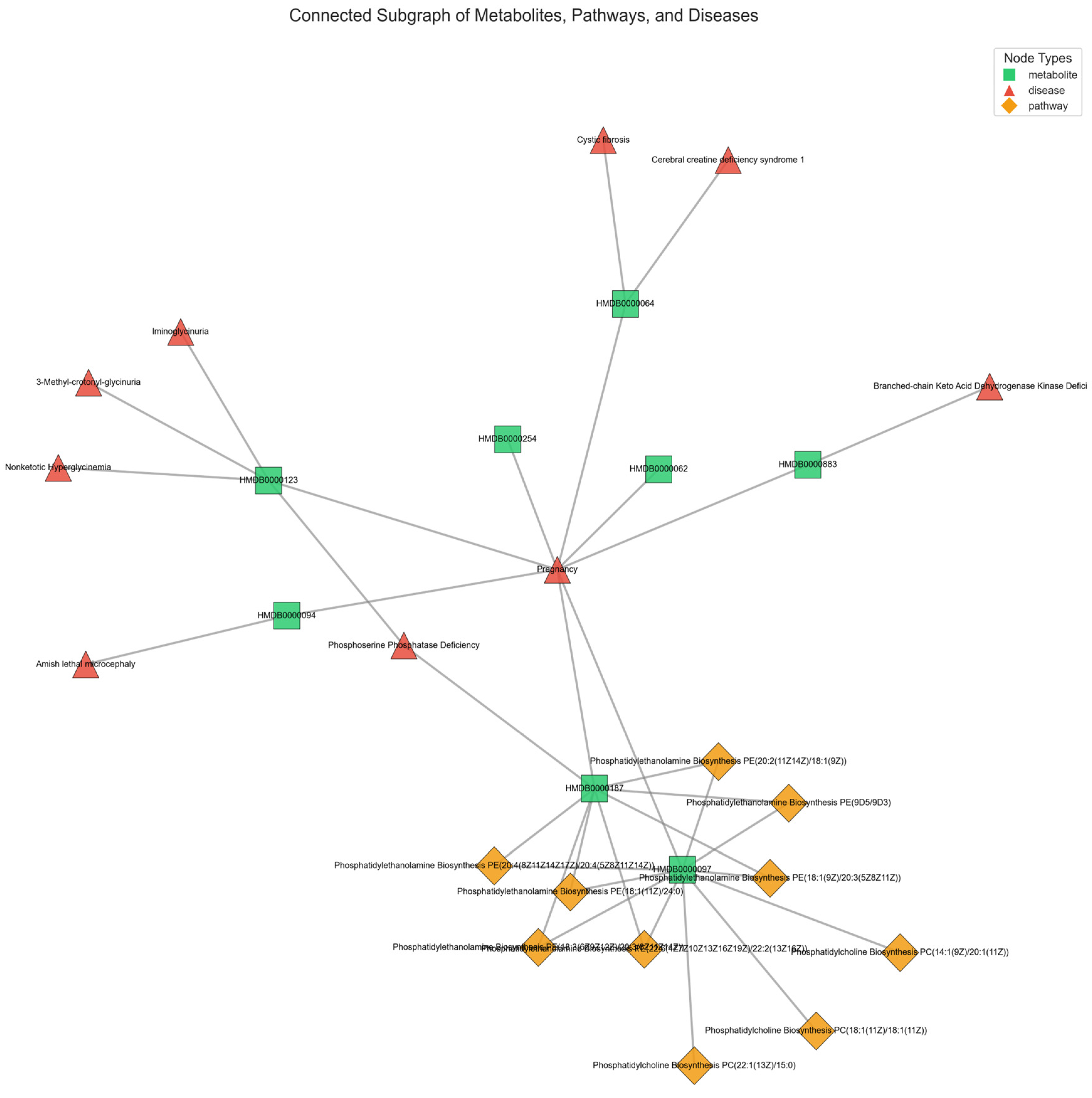

Figure 5 provides a representative illustration of the intricate connectivity within the metabolic network. The visualization highlights how metabolites contribute to multiple pathways and diseases, reinforcing the need for models that can integrate such complex associations for improved disease prediction.

The M-GNN model achieves a test accuracy of 93% and a ROC-AUC of 0.96, surpassing traditional tabular machine learning benchmarks, such as the 83% accuracy reported using conventional methods on similar metabolomics datasets [

8]. These results, visualized in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, demonstrate rapid convergence in less than 400 epochs and robust discriminative power, particularly for early-stage lung cancer cases (70% Stages I-II), aligning with the metabolomics-driven early detection paradigm [

22,

25].

Feature importance was extracted using SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to quantify the influence of each feature on the model’s predictions. SHAP values were computed by sampling 100 times from the test dataset, and the mean absolute SHAP value for the positive class (class 1) was calculated across all test samples. The most important feature overall was cigarette pack years, highlighting the critical role of smoking in lung cancer risk alongside metabolic biomarkers. Among the 16 metabolites known to be associated with lung cancer, two—Choline and Taurine—were captured as part of the top 30 most important features identified by the model. Abnormal choline metabolism is a hallmark of malignant transformation, as it is essential for the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine, a key cell membrane component, and for cell signaling pathways that regulate proliferation and apoptosis. Elevated choline has been strongly linked to tumor aggressiveness and progression in lung cancer [

26]. Conversely, taurine is known for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which are critical in mitigating oxidative stress and modulating cellular proliferation. Alterations in taurine levels in lung cancer patients may reflect underlying metabolic adaptations to the tumor microenvironment, including increased oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling [

27].

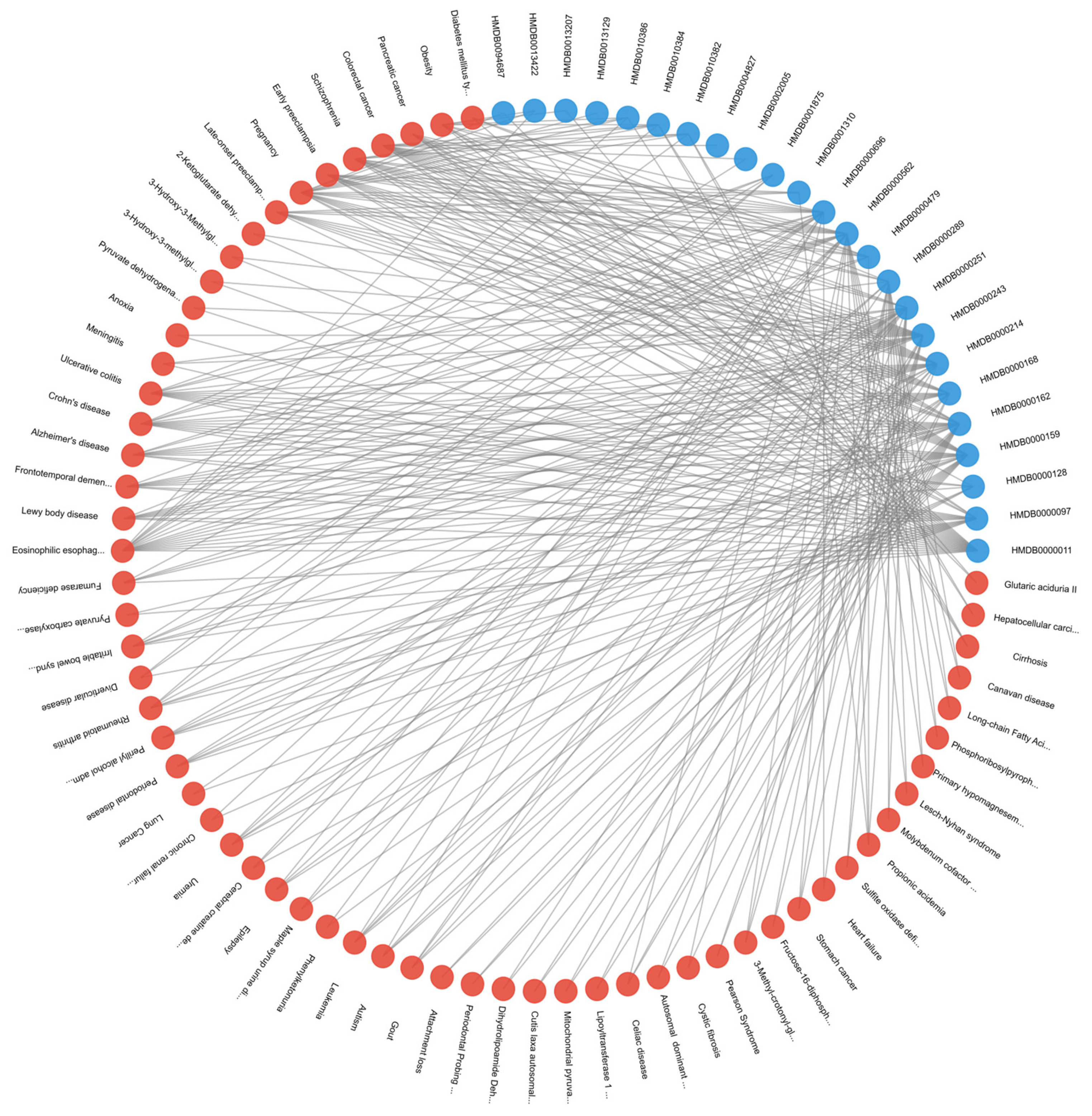

The three most frequently observed pathways linked to the most influential metabolites—Dimethylglycine Dehydrogenase Deficiency, Glycine–Serine–Threonine Metabolism, and Transcription/Translation—are implicated in a diverse array of diseases. Conditions ranging from metabolic syndromes (e.g., Diabetes mellitus type 2, Obesity) to multiple cancers (e.g., Pancreatic, Colorectal) demonstrate established connections with these pathways. In lung cancer specifically, the hijacking of one-carbon and amino acid metabolism (particularly glycine, serine, and threonine) fosters accelerated tumor growth, augmented nucleotide production, and balanced redox homeostasis [

28]. Moreover, inflammation-driven disorders such as Rheumatoid arthritis, Ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease share pro-inflammatory and transcriptional dysregulation mechanisms with malignancies, thereby generating an environment conducive to cancer progression [

29]. As illustrated in

Figure 6, which depicts diseases associated with at least two of the top 30 metabolites, lung cancer cells further capitalize on dysregulated transcription and translation to amplify oncogene expression and suppress tumor-inhibiting pathways [

30]. Consequently, these overlapping metabolic and regulatory processes underscore the reliance of lung cancer on core biosynthetic networks that integrate mitochondrial function and epigenetic control.

Despite these strengths, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the reliance on synthetic data to augment the minority class (controls) via SMOTE introduces potential biases. While the synthetic samples improved class balance and maintained an AUC of 0.96 when excluded from testing 5, they may not fully replicate the variability of real-world metabolomics profiles, risking overfitting to simulated patterns. Validation with larger, real-world datasets is essential to confirm generalizability. Second, the computational complexity of graph-based methods poses scalability challenges. With 3,508 nodes and 114,415 edges, processing times increase significantly with larger cohorts, limiting clinical deployment feasibility. Optimizing with attention mechanisms, such as those in GAT layers, or pruning non-essential edges could mitigate this issue. Third, the model’s focus on 107 metabolites would benefit from enhanced feature selection to manage dimensionality.

The M-GNN model results demonstrate that incorporating metabolomics data into a GNN-based framework significantly refines lung cancer detection and prognosis, aligning with the broader trend of using graph architectures for complex biomedical challenges [

31]. While prior imaging-based GNN studies have excelled in survival analysis and early-stage detection using CT scans [

32], our multi-omics approach underscores the value of integrating metabolite profiles and clinical factors to capture the metabolic intricacies of tumor biology. Moreover, such fusion strategies can be extended to genomic and transcriptomic data, as recently shown in dynamic adaptive deep fusion networks [

33], potentially improving predictive accuracy and uncovering novel therapeutic targets. Taken together, these findings illustrate how GNN methodologies can bridge the gap between diverse data modalities, enabling precision oncology solutions that are both highly accurate and biologically interpretable.

4. Materials and Methods

Metabolite Graph Neural Network (M-GNN) intoduced in this paper constructs a heterogeneous graph that integrates metabolomics and demographic data with biological pathways and diseases. To explore the relationships among pathways, diseases, and metabolites, we analyzed the 107 metabolites in our dataset that either have established normal ranges in the Human Metabolome Database or are associated with lung cancer within HMDB. Subsequently, we extracted all pathways involving these metabolites and identified diseases known to be associated with them, as documented in HMDB. Additionally, we enriched the metabolite nodes with HMDB-derived normal adult ranges, including Lower Limit, Upper Limit, and Average Expression Levels. Patient features were systematically categorized into two groups: demographic variables, encompassing attributes such as Gender, Race, Smoking Status, Smoking Current, and Smoking Past, Age, Height, Weight, BMI, Cigarette Packs per Year, and metabolite measurements associated with 107 metabolites. To ensure consistency, numerical features were normalized to a [0,1] scale using the StandardScaler, with missing values imputed based on K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN). The KNN imputation method estimated missing values based on the two nearest neighbors, applying a uniform weighting scheme.

A heterogeneous graph G=(V,E) was constructed using NetworkX to model relational dependencies among patients, metabolites, diseases, and pathways, drawing inspiration from graph-based biological modeling. Patient nodes contained 10 demographic features and 107 metabolite expression levels, while metabolite nodes utilized the 3 HMDB normal range features. Disease and pathway node features were set to [0]. Patients were linked to metabolites via weighted edges defined as the metabolite expression levels, with edge type defined as has_concentration. Metabolites were connected to diseases (weight 1.0, relation=associated_with) and pathways (weight 1.0, relation=involved_in). Patient node labels were set to [0,1], while all other node labels were defined as [-1].Patients with a history of smoking were linked to Lung Cancer disease node, with a weight of 0.8 and a relation type of risk_factor, to reflect increased risk. For the 16 metabolites known to be associated with lung cancer, the corresponding edge weight was set to 2. The graph was converted to a PyTorch Geometric Data object, encoding node features x∈R|V|×117, labels y∈R|V|, symmetrized edge indices, and weights.

The M-GNN model integrates edge weights into its graph convolutional layers through an adjacency matrix module, followed by a sequence of convolutional and dense operations. Edge weights were transformed using a sigmoid function and scaled by a learnable parameter , initialized at 0.5, which the model adjusts during training to fine-tune their influence.

The first convolution layer, defined as a SAGEConv begins with a standard unweighted mean aggregation of neighbor features. Subsequently, edge weights are applied by scaling the features of source nodes with their corresponding edge weights and normalizing by each target node’s degree to replicate SAGEConv’s mean aggregation logic. This weighted result is then blended with the original unweighted aggregation using a 50-50 average (Equation 1), ensuring that edge weights augment the aggregation without overshadowing the original node feature signals.

The weighted adjacency matrix

incorporates a learnable scaling parameter

that modulates the edge weights before multiplying them with the corresponding node features. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

where the source node weights

extract edge weights

for source nodes

, based on their connectivity to target nodes

.

Initially,

is set to a constant value of 0.5. It is subsequently updated by incorporating the weighted contributions of source node features

scaled by

. The degree of each node,

, is computed as:

ensuring a minimum degree of 1. Finally, the updated node features

are normalized and averaged, incorporating the effects of the adjacency matrix and node connectivity.

The model’s second layer is a GATConv layer, where scalar edge weights (edge_weight) are incorporated as edge attributes, influencing attention coefficients and allowing the model to dynamically prioritize connections. This layer outputs a 512-dimensional feature representation by concatenating 128 channels from four attention heads. Batch normalization is then applied, followed by an ELU activation and dropout (0.3) for regularization. Next, a SAGEConv layer further processes the features, reducing the dimensionality to 128. A weighted adjacency adjustment is performed, where contributions from source nodes are aggregated and normalized using the degree of target nodes, as described in the initial SAGEConv layer above. This adjustment balances feature propagation and ensures stability in the learned representations. The processed features undergo batch normalization, ELU activation, and dropout (0.3). The final stage consists of two fully connected layers: the first reduces feature dimensionality from 128 to 64, applying ELU activation and dropout (0.3), while the second generates the final logits for two-class classification. A diagram of the model architecture is shown in

Figure 7.

Training was conducted using the AdamW optimizer, configured with a learning rate of

and a weight decay of

. To dynamically adjust the learning rate, a ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler was employed, reducing the learning rate by a factor of 0.5 if validation loss did not improve for 100 consecutive epochs, with a minimum learning rate threshold of

. To handle the remaining class imbalance in the dataset asfter SMOTE, a weighted cross-entropy loss function was utilized. Class weights were computed based on the inverse frequency of class occurrences in the training labels, normalizing them to sum to one. Additionally, label smoothing (0.1) was applied to prevent overconfidence in predictions and improve generalization. The model was trained for up to 1,000 epochs, with an early stopping mechanism implemented if the validation F1 score did not improve for 100 consecutive epochs. Evaluation was performed on a held-out test set using multiple performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) to provide a comprehensive assessment of classification performance. To ensure reproducibility, the 10 random seeds were fixed across all stages of training and evaluation. The heterogeneous graph is composed of 107 metabolite nodes, 231 disease nodes, and 2,014 pathway nodes—totaling 3,508 nodes connected by 114,415 edges. Most connections (206,572 edges) reflect the expression levels of metabolites from 800 actual participants and 196 simulated controls, while 5,873 edges link pathways to metabolites.

Table 1 provides a summary of the graph.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces M-GNN, a Graph Neural Network framework leveraging GraphSAGE, designed for early lung cancer detection using a heterogeneous graph integrating metabolomics and demographic data from 800 plasma samples (586 cases, 214 controls), enriched with Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) annotations. The model achieved a test accuracy of 93% and an ROC-AUC of 0.96, converging within 400 epochs and exhibiting consistent performance across ten random seeds. The model effectively captures complex metabolic interactions, identifying key biomarkers like choline and taurine, and highlighting smoking history (cigarette pack years) as a dominant risk factor. Despite its strengths, limitations include potential biases from synthetic data and computational demands of graph-based methods suggesting future refinements with attention mechanisms or real-world datasets. M-GNN advances precision oncology by offering a scalable, interpretable tool for lung cancer screening, with potential to enhance survival rates through early detection and personalized treatment strategies. Future work should focus on validating the framework with clinical cohorts and optimizing computational efficiency to broaden its applicability in metabolomics-driven diagnostics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, RAB, J-FH, WRF and MV; Data curation, J-FH; Formal analysis and interpretation, MV, JW, EH; Funding acquisition, RAB, J-FH, PST. Methodology, J-FH, RAB, PST; Project administration, RAB; Project manager, GH; Resources, RA, GH, J-FH, BR, PST; Writing—original draft, MV, WRF; Writing—review and editing, MV, WRF, RAB, J-FH, PST, JW, EH. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported, in part, by Biomark Diagnostics Inc. (Richmond, BC, Canada).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (Ethics File #: H2012:334; approval date, December 12, 2022) prior to study implementation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to sample donation to the IUCPQ Biobank-Respiratory Health Research Network, Canada. .

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Infrastructure support was provided by the St. Boniface Hospital Foundation and the University of Manitoba and the Institut Universitaire de Cardiologie et de Pneumologie de Québec—Université Laval (IUCPQ), and the Cooperative Health Tissue Network (USA) for providing the plasma samples and patient data.

Conflicts of Interest

RAB is President and CEO of BioMark Diagnostics Inc. and is a shareholder. GH is President of BioMark Diagnostic Solutions Inc. J-FH is Executive Director of BioMark Diagnostic Solutions Inc. PST. is a minor shareholder of BioMark Diagnostics, Inc. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References

- Luo, G.; Zhang, Y.; Etxeberria, J.; Arnold, M.; Cai, X.; Hao, Y.; Zou, H. Projections of lung cancer incidence by 2035 in 40 countries worldwide: Population-based study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2023, 9, e43651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. 2024. Lung cancer survival rates. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/lung-cancer/ detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html. Accessed March 17, 2025.

- Wolf, A.M.D.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Shih, T.Y.; Walter, L.C.; Church, T.R.; Fontham, E.T.H.; Elkin, E.B.; Etzioni, R.D.; Guerra, C.E.; Perkins, R.B.; Kondo, K.K.; Kratzer, T.B.; Manassaram-Baptiste, D.; Dahut, W.L.; Smith, R.A. Screening for lung cancer: 2023 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 50–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyfried, T.N.; Shelton, L.M. Cancer as a metabolic disease. Nutr Metab 2010, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S. Metabolomics for investigating physiological and pathophysiological processes. Physiol Rev 2019, 99, 1819–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callejon-Leblic, B.; García-Barrera, T.; Pereira-Vega, A.; Gómez-Ariza, J.L. Metabolomic study of serum, urine and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid based on gas chromatography mass spectrometry to delve into the pathology of lung cancer. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2019, 163, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haince, J.-F.; Joubert, P.; Bach, H.; Bux, R.A.; Tappia, P.S.; Ramjiawan, B. Metabolomic fingerprinting for the detection of early-stage lung cancer: from the genome to the metabolome. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, S.A.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Mao, K.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Y. High-resolution metabolomic biomarkers for lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 11805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.L.; Ying, Z.; Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2017, 1024–1034.

- Patil, P.; Vaida, M. Patil, P.; Vaida, M. Learning gene regulatory networks using graph Granger causality. Proceedings of 14th International Conference, 2022, 10–19.

- Vaida, M.; Purcell, K. Hypergraph link prediction: Learning drug interaction networks embeddings. 18th IEEE International Conference On Machine Learning And Applications (ICMLA), 2019, 1860–1865.

- Zhang, Z.; Cui, P.; Zhu, W. Deep learning on graphs: A survey. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng 2020, 34, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Lyu, T.; Xiong, F.; Wang, J.; Ke, W.; Li, Z. Predicting the survival of cancer patients with multimodal graph neural network. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 2021, 19, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, S.; Liu, G.; Wu, W.; Wang, S. DeepMoIC: Multi-omics data integration via deep graph convolutional networks for cancer subtype classification. BMC genomics 2024, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, F.; Vakanski, A.; Zhang, B.; Elbashir, M.K.; Mohammed, M. Comparative analysis of multi-omics integration using graph neural networks for cancer classification. IEEE Access 2025, In Press.

- Song, H.; Yin, C.; Li, Z.; Feng, K.; Cao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Sun, H. Identification of cancer driver genes by integrating multiomics data with graph neural networks. Metabolites 2023, 13, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, H.Y.; Zhao, L.; Lee, C.C.; Chen, C.Y. A novel graph neural network methodology to investigate dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors in small cell lung cancer. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wishart, D.S.; Tzur, D.; Knox, C.; Eisner, R.; Guo, A.C.; Young, N.; Cheng, D.; Jewell, K.; Arndt, D.; Sawhney, S.; et al. HMDB: the Human Metabolome Database. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, D521–D526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velickovic, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Lio, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1710.10903v. [Google Scholar]

- Bamji-Stocke, S.; van Berkel, V.; Miller, D.M.; Frieboes, H.B. A review of metabolism-associated biomarkers in lung cancer diagnosis and treatment. Metabolomics 2018, 14, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Yao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, T.; Cai, W.; Zhou, D.; Yin, F.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Xie, C.; et al. An end-to-end deep learning method for mass spectrometry data analysis to reveal disease-specific metabolic profiles. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.; Rolfo, C.; Maksymiuk, A.W.; Tappia, P.S.; Sitar, D.S.; Russo, A.; Akhtar, P.S.; Khatun, N.; Rahnuma, P.; Rashiduzzaman, A.; et al. Liquid biopsy in lung cancer screening: The contribution of metabolomics. Results of a pilot study. Cancers 2019, 11, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Meng, W.Y.; Li, R.Z.; Wang, Y.W.; Qian, X.; Chan, C.; Yu, Z.F.; Fan, X.X.; Pan, H.D.; Xie, C.; et al. Early lung cancer diagnostic biomarker discovery by machine learning methods. Transl Oncol 2021, 14, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wang, Y.; Guan, J.; Li, J.; Han, R.; Hao, J.; Wei, Z.; Shang, X. An end-to-end heterogeneous graph representation learning-based framework for drug-target interaction prediction. Brief Bioinform 2021, 22, bbaa430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbashir, M.K.; Almotilag, A.; Mahmood, M.A.; Mohammed, M. Enhancing non-small cell lung cancer survival prediction through multi-omics integration using graph attention network. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glunde, K.; Bhujwalla, Z.M.; Ronen, S.M. Choline metabolism in malignant transformation. Nat Rev Cancer 2011, 11, 835–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.L.; Pan, H.D.; Yan, P.Y.; Mi, J.N.; Liu, X.C.; Bao, W.Q.; Lian, L.R.; Zhang, C.F.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.R.; et al. Serum taurine affects lung cancer progression by regulating tumor immune escape mediated by the immune microenvironment. J Adv Res 2024, S2090-1232(24)00389-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Tian, C.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, M.; Wang, K. 2023. The role of serine metabolism in lung cancer: From oncogenesis to tumor treatment. Front Genet 2023, 13, 1084609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vendramini-Costa, D.B.; Carvalho, J.E. 2012. Molecular link mechanisms between inflammation and cancer. Curr Pharm Des 2012, 18, 3831–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otálora-Otálora, B.A.; López-Kleine, L.; Rojas, A. 2023. Lung cancer gene regulatory network of transcription factors related to the hallmarks of cancer. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2023, 45, 434–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A comprehensive survey on graph neural networks. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 2021, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Long, Y.; Huang, F.; Ng, K.S.; Lee, F.M.Y.; Lam, D.C.L.; Fang, B.X.L.; Dou, Q.; Vardhanabhuti, V. Imaging-based deep graph neural networks for survival analysis in early stage lung cancer using CT: A multicenter study. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 868186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Wu, W.; Hou, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Qiang, Y.; Wang, L. DADFN: dynamic adaptive deep fusion network based on imaging genomics for prediction recurrence of lung cancer. Phys Med Biol 2023, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).