1. Introduction

Pancreatic cancer remains one of the most aggressive malignancies, with surgical resection serving as the only potentially curative treatment despite dismal long-term survival rates [

1]. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is central to curative therapy; however, the perioperative period is critical, as the anesthetic technique employed can significantly influence immune function and tumor biology. General anesthesia (GA) with endotracheal intubation triggers a robust neuroendocrine stress response, resulting in elevated catecholamines and pro-inflammatory cytokines that may impair natural killer cell function and promote tumor dissemination [

2,

3]. Moreover, GA induces significant alterations in the plasma metabolome, which could further impact tumor behavior [

4]. In contrast, epidural anesthesia (EA) attenuates these adverse responses, providing superior postoperative pain control and fostering a more favorable immunologic and metabolic milieu [

5,

6,

7].

Emerging evidence suggests that the anesthetic technique used during oncologic surgery may significantly influence both perioperative and long-term cancer outcomes. General anesthesia (GA) with endotracheal intubation provokes a pronounced stress response—and is associated with deleterious metabolomic shifts—that may impair immune function and promote tumor dissemination. In contrast, epidural anesthesia (EA) attenuates this neuroendocrine response, improves postoperative pain control, and may favorably modulate tumor biology [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Additionally, Chen et al. reported that intraoperative epidural ropivacaine infusion positively impacted oncologic outcomes in pancreatic cancer patients [

12], while a meta analysis by Ang et al. does not support or refute the association between the use of regional anesthesia and a lower incidence of cancer recurrence compared to general anesthesia in cancer resection surgery [

13].

Hence, optimal surgical stress management necessitates the implementation of the most effective anaesthetic techniques. Potent pain management, prompt mobilisation, and swift recovery are recommended to decrease the occurrence of complications as well as tumor recurrence. Historical studies by Nakashima et al. [

14] and Ueo et al. [

15] demonstrated the feasibility of performing major abdominal surgery under EA without endotracheal intubation—even in elderly patients. Subsequent recent research, such as the pilot study on neuraxial anaesthesia in hepato-pancreatic-bilio surgery have provided additional evidence about the feasibility the utilisation of EA alone for complex hepatobilary and pancreatic surgery [

16]. The aforementioned fact prompted several research groups to assess the impact of epidural analgesia on short-term postoperative clinical and oncological outcomes in prospective controlled trials involving pancreatic surgeries [

17,

18].

In light of these observations, this study aims to assess the feasibility and compare the early clinico-oncological outcomes in pancreatic cancer patients undergoing pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD) performed under epidural anaesthesia without endotracheal intubation (EA) versus those receiving general anaesthesia (GA)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using a prospectively maintained database at Burjeel Hospital, Abu Dhabi. The institutional review board approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. We included pancreatic cancer patients who underwent either PPPD or total pancreatectomy with or without splenectomy (TPS) between January 2015 and December 2022. Patients were stratified into:

Epidural Anesthesia Protocol with maintained spontaneous ventilation without intubation.

Patients underwent continuous monitoring utilising standard equipment, which included blood pressure measurement, pulse oximetry, electrocardiography, temperature assessment, and end-tidal CO₂ analysis. Before the procedure, a central line catheter was inserted in the internal jugular vein and patients were administered a fluid load of 1 litre of Ringer’s lactate, in addition to 1 mg of midazolam and 50 µg of fentanyl. A thoracic epidural was subsequently administered at the T6–T7 interspace. Following the confirmation of negative aspiration and the administration of a test dose, an 8 mL bolus of 0.5% ropivacaine was administered, succeeded by 150 µg of intrathecal morphine. A continuous infusion of 0.25% naropin was subsequently maintained at a rate of 7 mL per hour. Arterial line inserted in left radial artery and to maintain Middle arterial pressure above 65 mmHg, a continuous infusion of noradrenaline at an average dosage of 0.12 ± 0.06 mcg/kg/min was used to control hypotension caused by spinal anesthesia (

Figure 1). After surgery, all patients received 4 mg intravenous ondansetron to prevent post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV)

General Anesthesia Protocol with endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Patients were continuously monitored using standard equipment, including blood pressure measurement, pulse oximetry, electrocardiography, temperature assessment, and end-tidal CO₂ analysis. Prior to induction, intravenous access was secured and patients received a fluid load of 1 liter of Ringer’s lactate, along with appropriate premedication (2 mg of midazolam and 50 µg of fentanyl). Following preoxygenation, anesthesia was induced using intravenous agents—typically propofol—and neuromuscular blockade was achieved with a suitable agent (rocuronium) to facilitate endotracheal intubation. Endotracheal intubation was then performed under direct visualization, and anesthesia was maintained with a volatile agent (sevoflurane) in an oxygen–air mixture, supplemented with additional opioids as needed. Standard monitoring was continuously maintained throughout the procedure. An epidural catheter was inserted in both study groups and maintained for 3–5 days to provide postoperative analgesia and shifted extubated to the intensive care unit for short term observation.

2.2. Surgical Techniques of Pylorus Preserved Pancreatico-Duodectomy (PPPD)

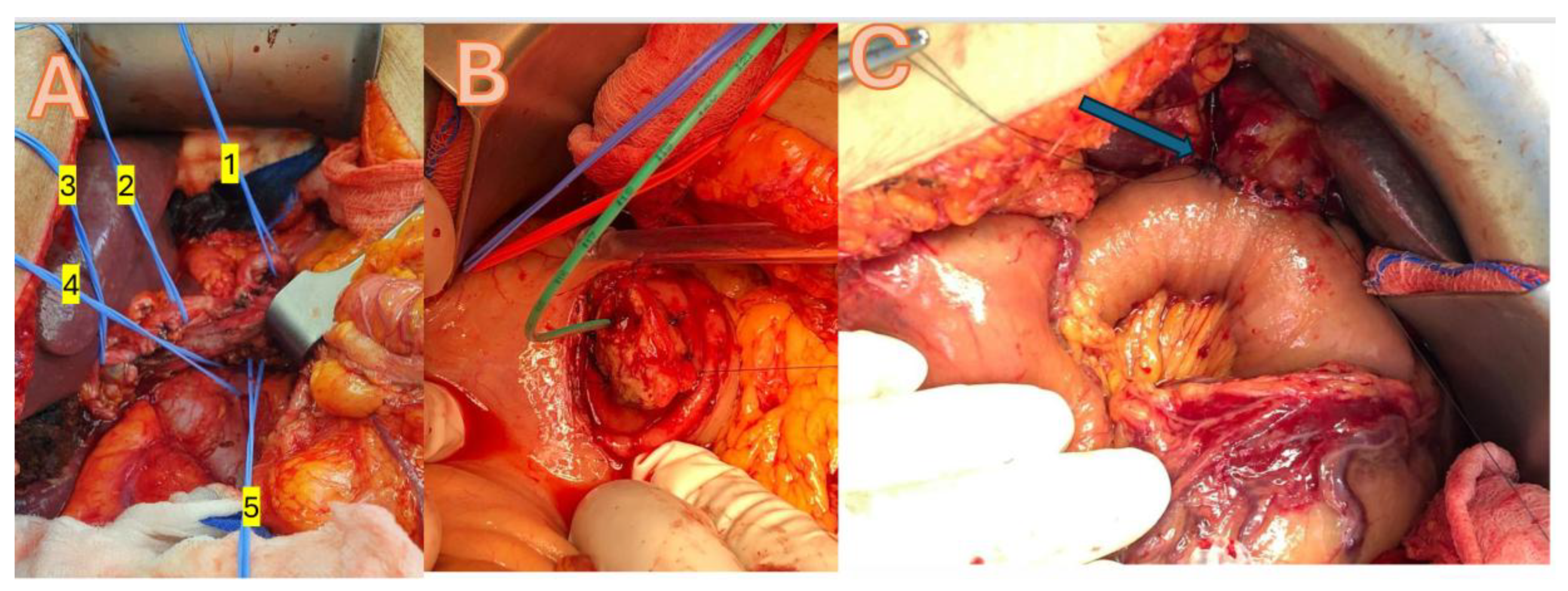

A median laparotomy or roof-top incision was used to gain access, with a Condor Abdominal Retractor employed to optimize exposure. Dissection was facilitated by the use of Harmonic and LigaSure energy devices, ensuring precise tissue division and hemostasis. Vascular clips were applied for vessel control, and anastomoses were performed using PDS 3.0 and 4.0 sutures. Reconstruction is achieved through a pancreatico-gastrostomy, incorporating a duct tube to maintain pancreatic duct patency and promote effective drainage, all while preserving the pylorus for optimal gastrointestinal continuity (

Figure 2).

2.3. Data Collection

Data collected included demographic variables (age, gender, ASA classification), operative details (procedure type, duration, conversion rates), postoperative outcomes (hospital stay, complications, ICU admissions), and oncologic parameters (R0 resection status, lymph node yield, histological tumor stage). Postoperative complications were graded using standard criteria, and pain management efficacy was assessed via patient-reported pain scores and analgesic requirements.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The student’s t-test was used to compare the means of continuous variables. When the sample size was small, we used the chi-squared test to compare continuous variables, and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Non-parametric variables were distinguished between groups using the Mann-Whitney test. The statistical test ANOVA was used to assess if there are any statistically significant differences among the means of the three groups. SPSS 29.0 was used for all statistical testing (IBM, SPSS® Chicago, IL, USA). To draw conclusions from the data, a p value of less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Operative Data

A total of 22 patients (15 males, females) with a mean age of 50.7 years (range 27–74) were included. No significant differences in preoperative demographics, including ASA classification, were observed between the GA and EA groups despite that patient in the GA group have higher Body mass index (

Table 1). The immunological parameter showed trend towards EA group without reching statistically significance (

Table 2).

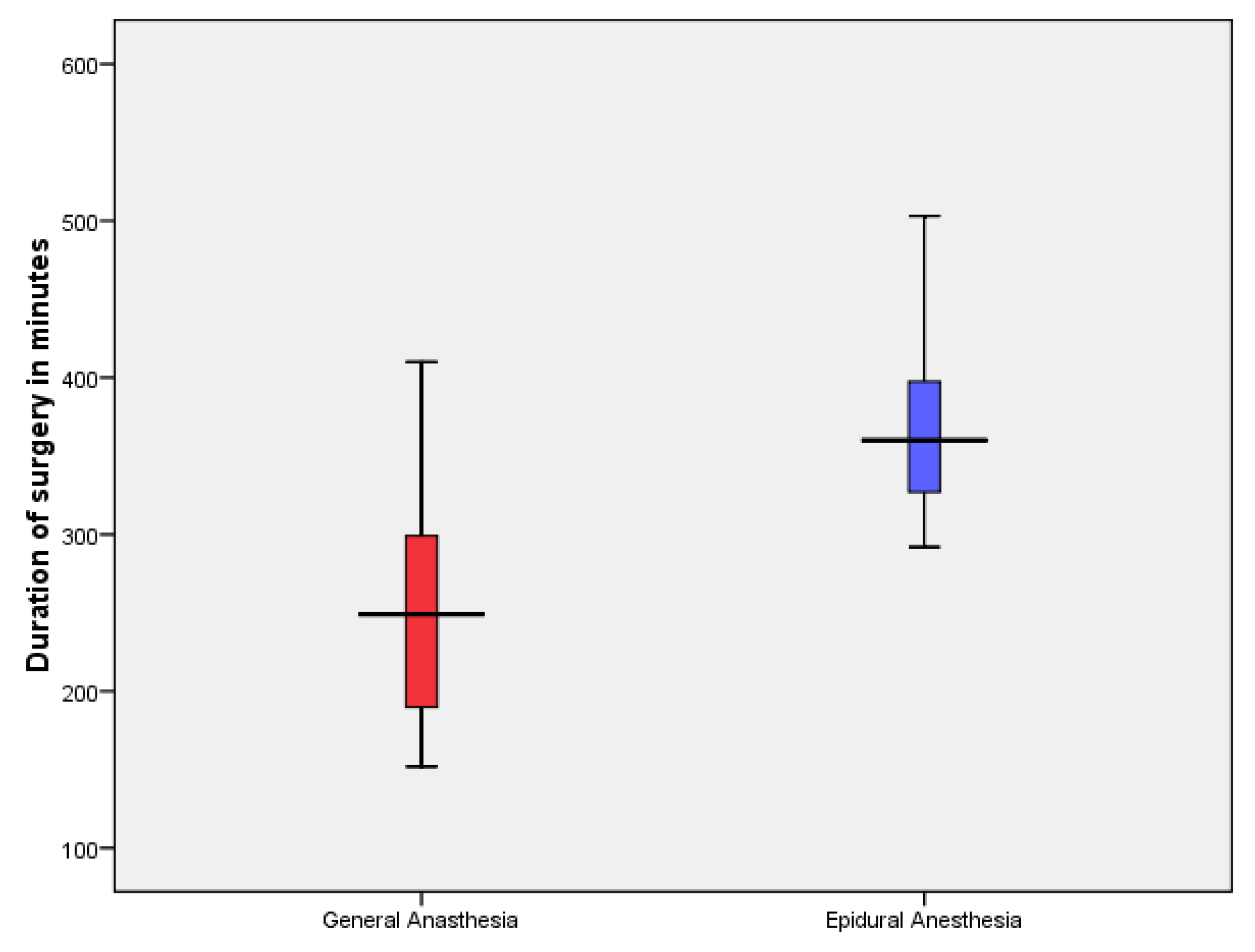

In the GA group, 13 patients underwent PPPD and one underwent Total pancreatectomy with splenectomy (TPS). In the EA group, six patients underwent PPPD and two underwent TPS. The average surgery time was significantly longer in the EA group (

Figure 3). However, The average hospital stay was 17.6 days (range 8-44) without statistically difference between the two groups, also the specific Biochemical parameter did not differ between the two groups (

Table 3).

3.2. Feasibility and Safety Outcomes

In the EA group, seven patients completed the procedure entirely under epidural anesthesia without conversion, while one patient undergoing total pancreatectomy with splenectomy required conversion to general anesthesia due to intraoperative respiratory acidosis. No mortality or major cardiopulmonary complications were observed during hospitalization, aside from one patient in the GA group who developed COVID-19 and required prolonged ventilation for 10 days before recovery. Overall, surgical complications were minimal: two GA patients developed pancreatic fistula type B, one EA patient experienced a biliary leak (all managed conservatively), and the COVID-positive GA patient underwent revision laparoscopy on postoperative day 30 for an iatrogenic bowel perforation following interventional radiology drain insertion for chylous ascites

3.3. Oncologic Outcomes and Postoperative Complications

All patients achieved an R0 resection. Moreover, the EA group demonstrated a significantly higher lymph node yield and a greater number of lymph node metastases (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Pancreatic cancer remains one of the most lethal malignancies, with recurrence and metastasis posing significant challenges even after surgery. Emerging evidence indicates that the anesthetic techniques employed during cancer surgery may influence oncologic outcomes by modulating the body’s immune response, stress levels, and inflammatory processes, potentially affecting the risk of cancer recurrence and metastasis [

19].

Our study demonstrates that pyloric-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy performed under epidural anesthesia without endotracheal intubation is both feasible and safe in selected pancreatic cancer patients. The high rate of successful EA completion—with only one conversion due to respiratory acidosis—and even better oncologic outcomes (as measured by tumor marker drop postoperatively , rate of lymph node metastasis and total number of lymph node yields) indicate that EA does not compromise the surgical radicality required for effective treatment.

A major advantage of EA is its capacity to mitigate the perioperative neuroendocrine stress response. GA with intubation elevates catecholamines and inflammatory cytokines, which may impair natural killer cell function and promote tumor dissemination . Additionally, GA-induced metabolic alterations, as demonstrated by recent metabolomic studies may further influence tumor behavior. In contrast, EA reduces these deleterious responses, thereby establishing a more favorable immunologic and metabolic environment. Recent evidence supports the beneficial role of EA in optimizing perioperative outcomes after pancreatic surgery [

20].

while the study by Hou-Choun et al. reported that propofol anaesthesia was associated with improved survival in open pancreatic cancer surgery compared to desflurane anaesthesia, although the study was based on a limited sample size [

21]. The study by Ren et al. showed no significant difference in overall survival and disease-free survival between total intravenous anesthesia and volatile anesthesia [

22]. Furthermore, long-term outcomes from the PAKMAN randomized study revealed no significant survival difference between patients receiving perioperative thoracic epidural analgesia and those managed with patient-controlled intravenous analgesia [

23].

Our study demonstrated that patients in the EA group experienced a longer hospital stay compared to those in the GA group, without an associated increase in morbidity. These findings align with previous research, which reported that epidural analgesia was linked to a prolonged length of stay—most notably affecting early discharge in patients undergoing open pancreaticoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy [

24].

Our study demonstrated that EA is a safe and feasible technique for complex pancreatic head resections. No major technical drawbacks were observed, and EA was successfully performed in all cases except one, which required conversion to GA at the end of surgery due to respiratory acidosis. Our cohort, comprised solely of patients with malignant pancreatic head cancer, is comparable to many series reported in the literature. The mean operative time of 300 ± 87 minutes was within the range of previously published data and was not adversely affected by the absence of neuromuscular blockade [

16,

25]. Additionally, the use of EA did not increase the risk of bleeding or compromise hemodynamic stability. Despite minor challenges related to the patient’s breathing, no significant issues occurred during the most complex surgical maneuvers, including the management of major vessels and lymphadenectomies as shown in

Figure 2.

Effective pain control was achieved in all cases, enabling early mobilization and timely resumption of oral intake. No patient died within the first 90 days after discharge, although long-term survival data were unavailable due to the multicultural composition of our cohort. There were no significant differences in postoperative inflammatory or tumor markers between the groups. Only one patient required conversion from EA to GA at the end of the procedure, likely due to an anesthesiologist handover driven by hospital working hours policy rather than respiratory acidosis, and this conversion was performed smoothly. The overall cohort experienced a longer hospital stay compared to more recent studies [

26,

27], primarily due to the pivotal nature of the study and the wide geographical referral of patients, which necessitated a more cautious approach to discharge. However, the length of stay remained comparable to that reported in studies from the past decade [

28].

Our study is the first to compare anesthesia type with lymph node yield and metastatic ratio in major abdominal procedures like pancreatic head resection. While most literature has focused on surgical technique, specimen processing, or neoadjuvant therapy as determinants of lymph node yield, our findings demonstrate that even major pancreatic resections yield more lymph nodes and higher lymph node metastasis detection when performed under epidural anesthesia—without endotracheal intubation or muscle relaxants—indicating that this anesthesia approach does not compromise oncological radicality. Finally, a propensity weighted analysis in renal cell carcinoma by Yen et al. illustrate that the association between anesthetic modality and oncologic outcomes may vary by tumor type. These diverse findings underscore the complex interplay between anesthetic technique and oncologic outcomes [

29].

The study’s limitations include its retrospective design, which may introduce biases such as selection and recall bias, and a restricted patient cohort that reduces statistical power and limits the generalizability of the findings, potentially under-representing infrequent events.

5. Conclusions

Our study supports the safety and feasibility of performing major pancreatic head resections for cancer under epidural anesthesia without endotracheal intubation. We found that this approach does not significantly increase morbidity or mortality compared to procedures conducted under general anesthesia. Furthermore, short-term oncological outcomes measured by complete tumor resection, the number of lymph node metastases, and total lymph node yield appear to be comparable, if not superior, to those achieved with general anesthesia. However, to establish definitive conclusions regarding long-term outcomes, larger randomized controlled trials are needed. These studies will provide further insights into the efficacy and long-term oncological benefits of epidural anesthesia in pancreatic surgery, ultimately guiding clinical practice and optimizing patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

Data curation, I.G.; investigation, I.H.; writing, reviewing and editing, L.H and M. I.; promotion and inspiration, W.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Burjeel Hospital in Abu Dhabi (BH/REC/Institutional Review Board/033/22). All patients who took part in the study signed a written informed consent form when they were admitted.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the results of this study can be requested from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Burjeel Holdings founder and chairman, Dr. Shamsheer Vayalil, who is both the impetus behind our mission to improve the level of service that we provide to the community, as well as our primary source of inspiration and the motivation for carrying on our work. Additionally, we would like to thank John Sunil, Manish Jain, Mohamed Sarfroz Rahiman and Deepan Gd, who make up the senior management team at Burjeel Hospital, for guiding us with their passionate support, insightful comments and constructive criticism about this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 29;362(17):1605-17. [CrossRef]

- Sessler DI. “Regional Anesthesia and Cancer Recurrence.” Anesthesiology. 2009;111(6):1234–1242.

- Exadaktylos AK, Buggy DJ, Moriarty DC, Mascha E, Sessler DI. “Can regional anaesthesia reduce the risk of tumour metastasis?” Anesthesiology. 2006;105(4):657–659.

- Oncotarget. “Perioperative changes in the plasma metabolome of patients receiving general anesthesia for pancreatic cancer surgery.” Oncotarget. 2021;12:996–1010. [CrossRef]

- Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, et al. “The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After.” Surgery. 2017;161(3):584–591.

- Hovaguimian F, Raptopoulos S. “Pancreaticoduodenectomy: outcomes and complications.” J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(5):1013–1021.

- Macario A, Weinger M, Truong P, Lee M. “Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to avoid? The perspective of patients.” Anesth Analg. 1999;89(3):652–658.

- Ramly MS, Buggy DJ. Anesthetic Techniques and Cancer Outcomes: What Is the Current Evidence? Anesth Analg. 2024 Oct 4. [CrossRef]

- Hiller JG, Perry NJ, Poulogiannis G, Riedel B, Sloan EK. Perioperative events influence cancer recurrence risk after surgery. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018 Apr;15(4):205-218. [CrossRef]

- Plücker J, Wirsik NM, Ritter AS, Schmidt T, Weigand MA. Anaesthesia as an influence in tumour progression. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021 Aug;406(5):1283-1294. [CrossRef]

- Piegeler T, Roesner S, Drover D, et al. “Impact of anesthetic technique on cancer recurrence: a systematic review.” Eur J Cancer. 2019;104:113–121.

- Chen W, Xu Y, Zhang Y, Lou W, Han X. “Positive Impact of Intraoperative Epidural Ropivacaine Infusion on Oncologic Outcomes in Pancreatic Cancer Patients Undergoing Pancreatectomy: A Retrospective Cohort Study.” Cancer. 2021;12(15):4513–4521. [CrossRef]

- Ang E, Ng KT, Lee ZX, Ti LK, Chaw SH, Wang CY. Effect of regional anaesthesia only versus general anaesthesia on cancer recurrence rate: A systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2020 Dec;67:110023. [CrossRef]

- Nakashima H, Ueo H, Takeuchi H, et al. “Pancreaticoduodenectomy under epidural anesthesia without endotracheal intubation for the elderly.” Int Surg. 1995;80(2):125–7.

- Ueo H, Takeuchi H, Arinaga S, et al. “The feasibility of epidural anesthesia without endotracheal intubation for abdominal surgery in patients over 80 years of age.” Int Surg. 1994;79(2):158–62.

- Rocca A, Porfidia C, Russo R, Tamburrino A, Avella P, Vaschetti R, Bianco P, Calise F. Neuraxial anesthesia in hepato-pancreatic-bilio surgery: a first western pilot study of 46 patients. Updates Surg. 2023 Apr;75(3):481-491. [CrossRef]

- Pak LM, Haroutounian S, Hawkins WG, Worley L, Kurtz M, Frey K, Karanikolas M, Swarm RA, Bottros MM. Epidurals in Pancreatic Resection Outcomes (E-PRO) study: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018 Jan 26;8(1):e018787. [CrossRef]

- Negrini D, Ihsan M, Freitas K, Pollazzon C, Graaf J, Andre J. “The clinical impact of the perioperative epidural anesthesia on surgical outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: A retrospective cohort study.” Surgery Open Science. 2022;10(suppl C):91–96.

- Choi H, Hwang W. Anesthetic Approaches and Their Impact on Cancer Recurrence and Metastasis: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers (Basel). 2024 Dec 22;16(24):4269. [CrossRef]

- Longo, F.; Panza, E.; Rocca, L.; Biffoni, B.; Lucinato, C.; Cintoni, M.; Mele, M.C.; Papa, V.; Fiorillo, C.; Quero, G.; et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) in Pancreatic Surgery: The Surgeon’s Point of View. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6205.

- Lai HC, Lee MS, Liu YT, Lin KT, Hung KC, Chen JY, Wu ZF. Propofol-based intravenous anesthesia is associated with better survival than desflurane anesthesia in pancreatic cancer surgery. PLoS One. 2020 May 21;15(5):e0233598. [CrossRef]

- Ren J, Wang J, Chen J, Ma Y, Yang Y, Wei M, Wang Y, Wang L. The outcome of intravenous and inhalation anesthesia after pancreatic cancer resection: a retrospective study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022 May 30;22(1):169. [CrossRef]

- Klotz R, Ahmed A, Tremmel A, Büsch C, Tenckhoff S, Doerr-Harim C, et al. “Thoracic Epidural Analgesia Is Not Associated With Improved Survival After Pancreatic Surgery: Long-Term Follow-Up of the Randomized Controlled PAKMAN Trial.” Anesth Analg. 2024 Feb 9. [CrossRef]

- Kim SS, Niu X, Elliott IA, Jiang JP, Dann AM, Damato LM, Chung H, Girgis MD, King JC, Hines OJ, Rahman S, Donahue TR. Epidural Analgesia Improves Postoperative Pain Control but Impedes Early Discharge in Patients Undergoing Pancreatic Surgery. Pancreas. 2019 May/Jun;48(5):719-725. [CrossRef]

- Seiler CA, Wagner M, Bachmann T, Redaelli CA, Schmied B, Uhl W, et al. Randomized clinical trial of pylorus-preserving duodenopancreatectomy versus classical Whipple resection-long term results. Br J Surg. 2005;92(5):547–556. [CrossRef]

- Takchi R, Cos H, Williams GA, Woolsey C, Hammill CW, Fields RC, Strasberg SM, Hawkins WG, Sanford DE. Enhanced recovery pathway after open pancreaticoduodenectomy reduces postoperative length of hospital stay without reducing composite length of stay. HPB (Oxford). 2022 Jan;24(1):65-71. [CrossRef]

- Nikfarjam M, Weinberg L, Low N, Fink MA, Muralidharan V, Houli N, Starkey G, Jones R, Christophi C. A fast track recovery program significantly reduces hospital length of stay following uncomplicated pancreaticoduodenectomy. JOP. 2013 Jan 10;14(1):63-70. [CrossRef]

- Xie YB, Wang CF, Zhao DB, Shan Y, Bai XF, Sun YM, Chen YT, Zhao P, Tian YT. Risk factors associated with postoperative hospital stay after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a retrospective study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126(19):3685-9. PMID: 24112164.

- Yen FY, Chang WK, Lin SP, Lin TP, Chang KY. “Association Between Epidural Analgesia and Cancer Recurrence or Survival After Surgery for Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Propensity Weighted Analysis.” Front Med. 2022;9:782336. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).