1. Introduction

A familiar "memory wall" problem exists for modern computing systems: the speed and parallelism of processors have moved ahead of improvements in memory access latency and bandwidth [1,17]. Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) are prominent in data-centric applications like machine learning (ML) inference and high-performance computing (HPC), which compounds this issue [9,20]. FPGAs can be custom configured to accelerate various computations. Still, traditional FPGAs do not feature sophisticated Memory Management Units (MMU) that are pervasive in CPUs [2,7].

A Memory Management Unit (MMU) provides essential features, such as address translations, caches, and memory protections, that facilitate programming and increase resource usage in general-purpose processors [1,10]. If brought to FPGAs, these capabilities would allow for multi-tenant sharing, more straightforward memory allocation, and easy integration of FPGAs into general-purpose compute environments [11,21].

This work investigates an integrated approach to enhance MMU (Memory Management Unit) functionality with ML (Machine Learning) techniques embedded in the FPGA, creating an ML-driven MMU. The proposed MMU organization contains learning models (e.g., Reinforcement Learning (RL) agents and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks) to anticipate access behavior and adjust memory management policies automatically [6,14]. The idea is to improve performance metrics (latency, throughput, bandwidth utilization) beyond what fixed, heuristic-based policies can provide while enhancing security and adaptability [3,9].

Contributions of this work include:

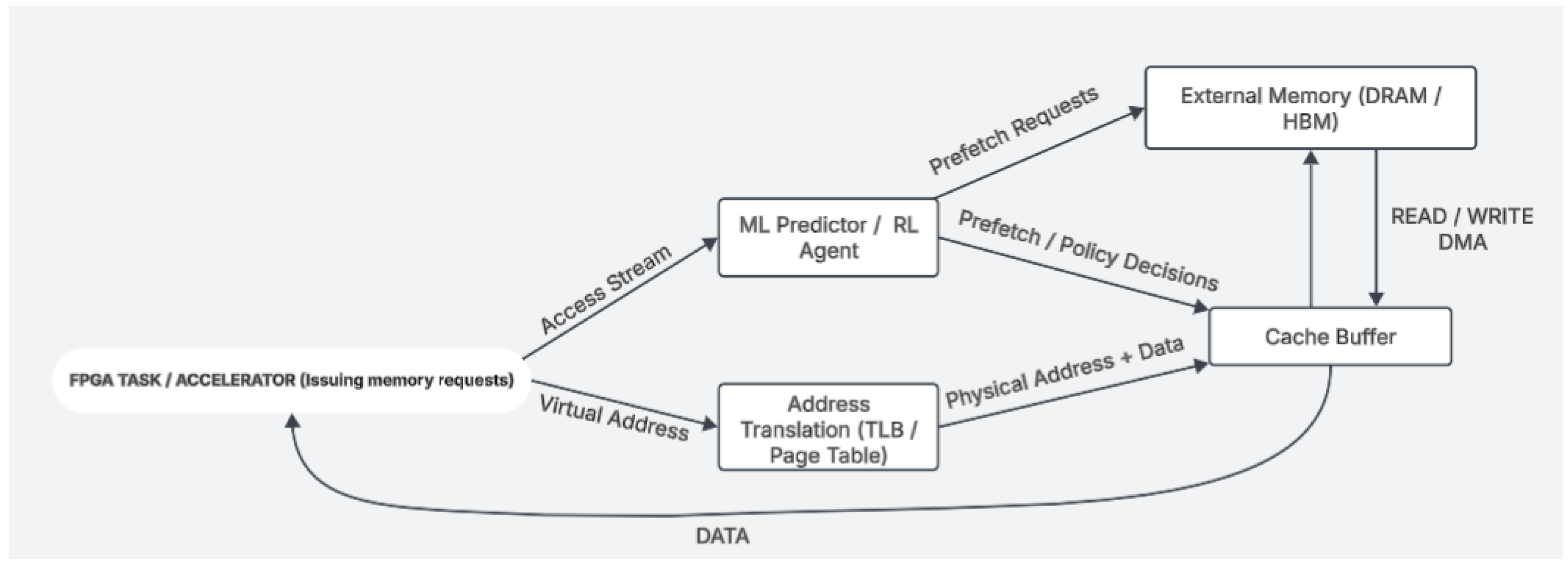

Architectural Design: We present architectural concepts for an ML-aware FPGA MMU that leverages virtual memory and caching [2,12]. The schematic shown in

Figure 1 describes an ML predictor module designed to optimize memory prefetching [1]. The ML predictor module interacts with address translation and cache buffers in two ways:

Cache with Prefetching Outputs: The module predicts memory accesses and prefetches data before a request from main memory [15].

Algorithm-Level Integration: We describe using Reinforcement Learning (RL) for self-optimizing memory scheduling and allocation [6]. Additionally, we integrate LSTM sequence models to predict future memory accesses for intelligent prefetching [1,17]. These techniques enable the memory system to learn and dynamically adjust to the program's behavior [16].

Security Improvements: We introduce built-in security measures in the MMU architecture to counter memory-based attacks [3,13]. Moreover, advanced security solutions based on AI, like anomaly detection in streaming scan networks (SSNs), offer further defense against vulnerabilities at test time, as well as IP leaking in design-for-test (DFT) architectures [8]. Combining physically unclonable functions (PUFs) and AI-based anomaly detection strengthens defenses against hardware Trojans and side-channel attacks even more [12]. These measures include:

Isolating Memory Access Timing: Prevents cache side-channel attacks [18].

Embedding Encryption/Masking in Hardware: Ensures data confidentiality using secure speculation techniques [9].

Protection Against Speculative Attacks: Mitigates vulnerabilities similar to Spectre/Meltdown [17]. Prior research has stressed the need to augment the RTL security methods with AI-based approaches for hardware security to reduce vulnerabilities in the design synthesis and verification [4]. Mathematical models in AI-based physical design verification also serve as crucial safeguards against unauthorized modifications and side-channel leakage [5].

Flexibility and Applicability: We elaborate on how the ML-based MMU can be adapted to work across multiple FPGA platforms and application domains, including:

AI inference accelerators

General-purpose CPU offloading [21,22] The ML-based MMU design is modular and can be retrained or tuned for specific workloads, giving it cross-domain adaptability [4,10].

Section 2 provides background on memory management in FPGA workloads and the purpose of MMUs.

Section 3 provides details of the architecture of the ML-driven MMU, and the ML algorithms incorporated therein.

Section 4 provides a comparative performance evaluation of the traditional approaches. Security considerations are covered in

Section 5.

Section 6 covers the flexibility of the design across applications and platforms.

Section 7 closes with a summary (of the novelty of the approach in the context of intellectual property (patent claims).

2. Memory Management in FPGA Workloads

2.1. FPGA Workloads and Memory Challenges

FPGAs have transitioned from fixed-function logic devices to general-purpose devices and, finally, to AI/ML workload accelerators [9,20]. Sequentially, hybrid CPU-FPGA architectures have been widely used for workloads in data centers, including neural network inference, data analytics, and streaming computations, where the FPGA offers data parallelism. At the same time, the CPU performs flow control and serial computations [19,21].

These workloads usually deal with big datasets, and their efficiency is directly associated with how efficiently they access memory to achieve optimal performance. Nonetheless, the memory hierarchy in such systems is based on FPGAs, which have an entirely different architecture than classical CPUs [2,7]. In a typical CPU architecture (e.g., x86, ARM), the MMU and cache hierarchy give a nice abstraction of memory: the programs use virtual addresses which the hardware is mapping to their physical addresses while caching recently used mappings in the TLB and often used data in multi-level caches [1,10]. This allows for efficient memory-sharing between processes, and the architecture automatically does the rest in the presence of cache misses [14].

Historically, unlike classic CPUs, FPGAs lacked hardware MMU support; compared to FPGAs, memory management could only be managed manually, or the traditional operation system of the host CPU has to get involved [2]. Because most FPGA kernels directly use physical addressing or fixed address regions, multi-kernel tasks cannot run concurrently or share memory resources flexibly [12]. Recent work has explored OS-style abstractions in FPGAs, improving the capability for memory management.

FPGA operating environments provide an OS abstraction layer to allow complete OS-like services, such as virtual memory, process isolation, and secure multitasking among shared FPGA resources (e.g., Coyote) [7]. FPGA virtual memory support has been shown to have low overhead with significant performance gains [13]. For FPGAs, a hardware MMU can provide task-memory isolation, allow multiple accelerators to share memory banks safely, allocate/free memory at runtime, and perform context switching by saving/restoring the memory state [3,6].

The introduction of CPU-like memory management two strategies in FPGAs and their expected benefits, especially for complex workloads in a multi-tenant context [2,9], are well established. Nevertheless, though FPGA memory management is still in its infancy compared to CPUs, a single-layer memory hierarchy is the first step toward using more sophisticated memory architectures [15]. In contrast, many FPGA designs do not use a cache hierarchy (outside of simple FIFO buffers) and do not employ automatic prefetching or replacement schemes. As a result, if many accelerators access the memory simultaneously, the scheduling of these accesses, which is either defined statically or determined by the logic written by the user, can become a source of performance bottlenecks [8,16]. This impact leads to a motivation to bring machine-learning paradigms into MMU design since the design of FPGA memory management tends to lack intelligence and adaptivity [4,5].

2.2. The Role of an MMU in Architecture

In a computing system, a Memory Management Unit (MMU) is responsible for translating a given virtual address to the corresponding physical address and enforcing memory access policies (e.g., permissions, caching) [2,10]. In CPUs, the MMU is key to the implementation of virtual memory alongside Translation Lookaside Buffers (TLBs) and page tables, which allows multiple processes to run in isolation of one another, with each being provided the illusion of a contiguous address space [7,15]. It also closely interacts with cache controllers to service memory access requests with low latency [14].

However, standard MMU architecture incurs performance overheads, as TLB misses lead to a page-table walk that can stall the processor. Page-table walks are frequent, degrading performance and consuming memory bandwidth [1,6]. Mechanisms such as larger TLB sizes, multi-level TLB hierarchies, and page walk caches are employed to address this issue, but the MMU behavior is predominantly static, and determined during design time primarily based on average workloads [9,16]. Integrating an MMU into an FPGA allows requests from the FPGA logic to be issued with a virtual address that can be translated into a physical address in DRAM or other memory on the fly [2,8]. This has several benefits:

Memory Virtualization: FPGA accelerators have no need to hard-code physical addresses and can relocate or allow multiple accelerators to share memory transparently [12,21].

Dynamic allocation: Memory Regions can be dynamically allocated and reclaimed for accelerators at runtime, enhancing FPGA resource utilization [5,18].

Memory protection: An MMU can restrict memory access with permissions when several users or processes share one FPGA [3,12].

Cache Management: An MMU might also incorporate cache structures, providing faster access to commonly requested data and decreasing average access times [8,19].

FPGAs typically feature heterogeneous memory types in their memory architecture:

On-chip Block RAM (BRAM) – High speed but less storage [22].

High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) – Memory built-in stacks for applications that require high bandwidth [20].

External DDR SDRAM ≃ has high capacity but is also slower, which is a cost-effective solution for massive datasets [10].

MMU on FPGAs can cover memory tiers, as to what to keep where on-chip, and what to push off-chip, just as a CPU’s memory system will demarche l1/l2 caches v.s. Main memory [14]. At least in the second case, traditional FPGA designers avoided complex caching mechanisms due to concerns about timing predictability in time-critical applications or simply because FPGA-based tasks were designed to stream data, and manual buffering was sufficient [17]. However, with the diversification of workload characteristics on FPGAs, the importance of a dynamic caching/prefetching mechanism is becoming more paramount [4,9].

Adding an MMU brings field programmable gate array (FPGA) architecture closer to its roots in general-purpose computing, allowing for easier programming, multi-tasking, and improved memory management in reconfigurable architectures [2, 11]. This prepares the ground for enriching the MMU by equipping it with machine learning to take it one step further in performance, efficiency, and adaptability.

3. ML-Driven MMU Architecture and Algorithms

Machine Learning allows the MMU to learn from memory access patterns and optimize memory handling decisions continuously. In our proposed ML-driven MMU, we integrate ML models as part of the memory management hardware.

Figure 1** shows a high-level overview of architecture. The MMU sits between the FPGA’s user logic (accelerator kernels) and the external memory. It comprises conventional components—such as an address translation unit (page table and TLB) and a cache or prefetch buffer—augmented by an ML Predictor/Reinforcement Learning Agent module. The ML module observes the stream of memory references (virtual addresses) from the FPGA tasks and learns temporal and spatial patterns. It then influences the MMU’s behavior by (a) predicting upcoming memory accesses and issuing prefetch requests to bring data into the cache before it is needed and (b) dynamically adjusting policies (cache replacement, memory scheduling, allocation decisions) via learned policy outputs (dashed control signals in

Figure 1).

3.1. Address Translation and Caching Module

The ML-driven MMU functions like a traditional MMU, maintaining a page table in memory and a TLB on-chip for caching recent translations. An incoming memory request featuring a virtual address is intercepted by the MMU, which performs a TLB lookup; on a hit, the physical address is retrieved, and on a miss, a page table walk is performed (which can take several memories accesses, in case of multi-level page tables, like in x86/ARM jargon). One such improvement we can potentially explore is using ML to prefetch translations. If the MMU knows the access pattern of the virtual pages, it could learn which virtual-to-physical mappings will be required shortly and pre-load them into the TLB, thus avoiding expensive page table walks. This is similar to prefetching but for address mapping granularity. For example, when an accelerator is seen to iterate through an array, the MMU's ML module may predict the following few pages and map them first in the TLB.

The caching/prefetch buffer is coupled with address translation. This functions as a small on-chip cache containing data lines that have recently been or will soon be used. A typical design may employ an LRU (Least-Recently Used) or FIFO policy for eviction and simpler next-line prefetchers. We make use of ML to assist our line-level functionality: the replacement policy would potentially be guided by an RL agent that has observed which lines are likely to be reused (as opposed to those that could be evicted without consequence), and the prefetcher would be augmented with a sequence learning model that predicts future accesses. (For example, in a streaming scenario, you may use a write-through behavior to keep it coherent with the external memory; in a more general scenario, write-back with appropriate invalidation would be necessary even in a scenario where multiple agents share memory). The ML-based cache aims to increase the cache hit rate and timely availability of data to decrease the effective memory access latency for the logic on FPGA.

3.2. Memory Access Prediction with Machine Learning

Reinforcement Learning (RL) with Memory Scheduling: One of the strong sides of RL is that it allows one to learn the best actions via trial and feedback. In the context of using an RL agent in a memory system, it can be trained (or even deployed online) to make resource management decisions, such as choosing which memory request to service next (if there is a queue) or which bank to prioritize or how/when to schedule memory refreshes—getting higher performance using RL-based memory controllers. Previous works on using RL to learn adequate memory controls have indicated significant performance improvements — in one case, an RL memory controller was able to learn to optimize DRAM command scheduling and provide 19% average performance improvement (up to 33%) on a 4-core system, and 22% increase in DRAM bandwidth utilization when compared to a conventional policy. This means that RL can discover higher-quality scheduling policies than static heuristics, as RL seeks to optimize the long-term consequences of actions taken.

An RL agent can be integrated into our FPGA MMU to decide which cache line to evict, when to prefetch a line, how to spread memory accesses across different memory channels to avoid bottlenecks, etc. The agent observes the state information (e.g., current cache occupancy, recent access patterns, DRAM row buffer status, etc.) and selects actions (prefetch this address, evict that line, or schedule a pending request from Accelerator A before one from B, etc.) such that some reward function is maximized. They define the reward as promoting lower average memory access time and greater throughput. The policy governs the actions the RL agent takes over time. In contrast to a hardwired policy, the RL-based policy can adapt to workload changes: for example, if the access pattern switches from random to streaming, the agent might learn to prefetch sequentially; if two accelerators start contending for memory heavily, it might learn to prioritize one of them in a way that optimizes aggregate throughput or fairness.

Sequential Patterns and Loop Patterns: In many cases, the memory access pattern has temporal dependency — going sequentially over an array (either a whole array or one between two indices) or accessing a particular set of addresses repeatedly (loop pattern). These are sequences that an ML model can learn. Since then, all the above have descended into wild conjecture and speculation. LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) networks are a flavor of recurrent neural nets that can learn long-term dependencies. The prefetcher based on long short-term memory is significantly more accurate and achieves a higher prediction coverage in predicting memory accesses than classical prefetchers. One case study showed that the LSTM prefetcher achieved 98.6% prediction accuracy on a given pattern while a state-of-the-art conventional prefetcher performed 0% on the same pattern. These results emphasize that an ML model can detect complex modern data access patterns that more simplistic heuristic prefetchers (i.e., stride or delta correlation prefetchers) fail to exploit. The fundamental concept of an MMU is that some form of LSTM (or similar sequence model, or even a potentially advanced Transformer given recent work will take as input the recent history of memory accesses (e.g., a window of last N addresses or strides) and output the addresses the FPGA is likely to request next. Because FPGAs can handle multiple streams, the model could run per stream and encode the combined behavior. Compressed or quantized LSTM will help to fit into FPGA resources, and timing constraints are also in sync – techniques like model compression and pruning can ultimately reduce the model size to an order of magnitude and performance without disturbing accuracy. The network can produce one or more predictions (addresses) at a single inference. It can then prefetch those addresses into the MMU cache.

Dynamic Memory Allocation with ML: An ML-driven approach can also help allocate higher-level memory beyond caching and scheduling. Let's say the FPGA has various memory regions available (e.g., on-chip vs. off-chip or multiple NUMA regions of memory) — a learning model could predict what data must exist in what memory region for the best data access. For example, each time some data is used, it can be moved back to HBM (High Bandwidth Memory) attached to the FPGA if it's used by more than a certain threshold – an ML policy could learn which decisions to make based on usage patterns. Reinforcement learning or even heuristic-guided search (e.g., via a learned cost model) could be used for page placement: dynamically migrating or placing pages to the memory type most suited to their access patterns (analogous to OS NUMA allocators, but learned). In the context of cache design and DRAM control, there are some early works applying machine learning methods (e.g., genetic algorithms or perceptron (suggesting that a learned approach may yield better configurations than static ones over time by being able to trade off closely constrained trade-offs (e.g., power vs. performance) throughout an entire workload (or several workloads).

3.3. Integration and Implementation Considerations

An MMU based on machine learning must be designed for FPGA hardware implementations by considering timing and area constraints. (The ML components (RL agent, LSTM, etc.) are required to be efficient.) Another approach is to use smaller models in isolation or even hybrid approaches. For example, only use an LSTM for specific patterns (and use dove-tailing logic otherwise) or use a small neural network like a perceptron to make page replacement decisions, the compressed LSTM method proposed by Prasanna et al. decreases the number of model parameters significantly (O(n/logn) decrease). Still, it keeps the accuracy of predictions so the system can be implemented in hardware. The RL agent can be a table of Q-values or a small neural policy; previous designs for RL memory controllers employed hardware-efficient representations for the value function (e.g., quantization of states and lookup tables for Q-values). Imitating traces, online, vs. always-on control for training. To mitigate risk, MMU could gradually let RL agents' learned actions replace the initial baseline policy as it becomes more confident of avoiding catastrophe in the early learning phase. Another thing to consider is the interface with the rest of the system.

If the FPGA is attached to a CPU-host system (for example, as a PCIe accelerator card or as part of a SoC with an integrated ARM core), the MMU must also work with host memory management. If data caches are coherent, then any prefetching or caching that the FPGA's MMU performs must be coherent (i.e., the FPGA MMU should act as if it were a pseudo-CPU from the perspective of the coherence domain—whether this means following the same protocol as the CPU side is implementation dependent). In the other case, if the FPGAs work on in-coherent regions, it's not the coherence that can be the issue; however, explicit communication (DMA transfers managed with the host) will be used to move data. Our general ML-driven MMU concept applies to either architecture: in a fully coherent architecture, the ML prefetcher may model just as a hardware prefetcher, while in the decoupled architecture, the ML MMU may manage a private address space for the FPGA logic and have DMA for data movement (with ML optimizations deciding the movement). Architecturally, the ML-based MMU can be provided to the FPGA as a soft IP core. It could be an independent module that any accelerator design can connect to (using standard AXI or Avalon memory interface, for example). The MMU will present a virtual memory interface to the accelerators and take care of translation, caching, etc., under the hood. This modular architecture enables the MMU to be reused in various workloads and FPGA designs. The internal ML models can be replaced or retrained based on the use case (i.e., load different weights or policy for AI inference workload vs HPC simulation). Overall, the MMU architecture, which was designed using machine learning techniques, consists of conventional memory management hardware and novel decision-making units based on the ML method. This combined approach allows the memory subsystem to learn and optimize over time, addressing challenges associated with memory access latency and efficiency that static logic cannot. We then offer a comparative analysis of the benefits of this strategy relative to existing efforts.

4. Comparative Performance Evaluation

Latency: ML-controlled MMU minimizes effective memory access latency by increasing cache hit rate and prefetch timeliness. For example, a conventional prefetcher would struggle in this case, where an accelerator has a non-constant-loop stride; an LSTM-based predictor can learn it and prefetch accordingly, thus saving hundreds of DRAM latencies in cache misses. So, TLB misses, and cache misses can be predicted and resolved ahead of time by prefetching both data and page table entries. This implies that stalls can be far less frequent for an average memory access. An LSTM-based prefetcher has achieved an accurate 83.5% detection of memory accesses after examining the repeated previous five addresses against 75% accuracy by normal prefetch methods, which means lower miss-induced latency. We expect that, for memory-bound FPGA workloads, these enhancements could substantially improve effective IPC (instructions per cycle).

Throughput and Bandwidth: The ML-based MMU can more efficiently exploit the available memory bandwidth thanks to RL-based scheduling. It could also simply result in better scheduling requests from multiple accelerators sharing the same memory in the case of an FPGA; the ML MMU could learn to interleave requests or prioritize them in such a way that it keeps the memory bus busy but not overloaded. Fixed scheduling (e.g., round-robin, first-ready, first-come-first serve) may utilize some cycles while unfairly denying service to some requests, but an ML agent can do better balancing. But the real power ramp-up happens when you consider the throughput of the entire array (tasks/sec) and realize that you're increasing the system throughput up to that factor. We believe the ML-driven model will particularly excel in high contention or irregular patterns – potentially reaching near-peak bandwidth utilization where others do not (e.g., up to 90%+ of theoretical DRAM BW in workloads where regular would struggle in the 70% range).

Energy Efficiency: There is a duality here: the ML circuits are costly (power-wise) (for executing operations in the predictor and agent) but save power by lowering the number of accesses to off-chip memory and its associated idle stalls. Unfortunately, off-chip DRAM accesses are incredibly energy-intensive; by improving cache hit rates and more intelligently allocating memory, the ML-driven MMU can reduce these costly operations. Also, accelerators spend more time doing practical work per cycle (higher efficiency) in part because they finish memory operations sooner (better scheduling). So, if, for example, the ML MMU can cut the number of DRAM transactions by 15% through prefetching and caching reused data, that saves energy. The ML logic overhead can be made very small (the compressed models, for example, and the fact that these computations, even when trained, are relatively rare or simple). Hence, we expect the ML-driven MMU to potentially have less energy than the conventional systems when the energy buffer saved by the avoided memory misses is greater than the energy cost of the ML computations, for it should be competitive in energy efficiency.

Expected Results: If this were an evaluation (conceptually, it is), we would run benchmarks such as memory-intensive AI kernels, streaming operations, and multi-tenant scenarios. We would measure average memory access time (AMAT), bandwidth utilization, and system-level performance. We want lower AMAT for the ML-driven MMU (due to prefetch hits), higher sustained bandwidth when multiple accesses compete, and faster overall task completion times. An RL-augmented policy, for example, could reduce average memory access rate by 30% over random access patterns by executing physical access clustering. This task would typically be performed at compilation time. At the same time, an LSTM prefetcher could almost entirely remove the penalty of stride access patterns. This comparative study shows that driven ML has excellent potential to enhance memory implementation efficiency in FPGAs.

5. Security Enhancements

Security is a key factor of memory management, particularly with FPGA's evolution towards multi-user and general-purpose use cases. Implementing caches and speculation in an FPGA MMU would naturally expose vulnerabilities analogous to those on CPUs (e.g., cache timing side-channels, Spectre-like speculative attacks). To reduce these risks, our ML-driven MMU implements several security improvements that make use of both architectural techniques and the flexibility of ML to adapt to new attack conditions.

Cache Timing Attacks: These attacks leverage the predictive difference in time between cached access and non-cached access to measure secrets (e.g., attacks against AES or cross-VM on the cloud). FPGAs are also vulnerable – the researchers have shown cache-based side-channel attacks on FPGA-coherent caches in cloud FPGA platforms. To protect against this, the MMU uses cache partitioning and randomization. It is also possible to allocate a specific cache partition to each secure domain (e.g., each tenant or each isolated accelerator context) such that an attacker's code cannot evict the victim's cache lines. Moreover, the ML agent can identify abnormal access patterns that appear to be cache probing. A specific example (based on my hand-wavy extrapolation) might go something like this: if a particular context is quickly accessing a spread of addresses in a way that is not characteristic of "normal" operation, then the ML-driven MMU could write this down as a potential abuse (having already learned what is considered "normal") and intervene in some way – either adding noise to those prefetches, or suppressing them, or not.

Constant time access enforcement: We borrow the concept of memory access time being less dependent on secret data. With the MMU, we could optionally run in a mode where each memory access is given a slight random (or even constant) delay, or we could equalize the access time from the external observer's point of view. This would work against accurate timing measurements, and the fuel for side-channel attacks. Adding a delay may not seem quite right for performance, but the delays can be tuned (and possibly even only turned on in sensitive areas of code or data that the user can identify). The ML agent may even assist here by learning when injecting noise matters little for performance (such as in phases where memory is idle, or the pipeline can absorb a few cycles of slack).

Data Encryption and Masking: A common technique to secure the data in memory is encrypting its contents. Think of encrypting the data going into the DRAM so that even if an adversary reads the data, it will be useless to them. We propose the addition of a lightweight encryption module in the MMU to breed encrypt/decrypt before writing to external memory or after reading from external memory. Our design could key per context or containment region. A challenge here is that even naive encryption could leak information via access patterns or power, creating side-channel leakage. Methods such as random data masking in caches have been suggested to mitigate power analysis side-channels. For example, each cache line is XORed with a random mask stored elsewhere and is only unmasked immediately before use. This removes the data value—power consumption correlation. Such an MMU could include a module like Lightweight Mask Generator ( LightMaG ), which generates random masks to frequently re-mask cache data to defend against first-order power analysis attacks. Generally, because the ML-driven MMU has an intelligent core, it can even schedule mask updates intelligently (e.g., refresh mask during periods that least interfere with regular access).

Since it's encrypted, you must be careful with the data as it flows through the hierarchy. Keeping data encrypted can be as simple as storing it in the cache, but this approach would mean it had to be decrypted on each access, resulting in latency. The caches in modern CPUs are per tenant (at least overall, different cores might have different caches for the same tenant), so while working on a tenant's data, we can store plaintext in the cache without concern for speed, with the knowledge that we will partition the cache and physically evict lines on a context switch. Our design enables either mode based on security needs. ML could also adjust policy based on the mode (i.e., if encrypted cache mode is enabled, the prefetcher may be tuned to prefetch slightly further ahead to hide decryption latency).

Speculative execution vulnerabilities (Spectre, Meltdown), in essence, exploit that a processor can speculatively execute instructions (such as memory loads) before verifying whether they are permitted and that these speculated actions are still visible due to the shared cache. This issue can arise if we implement soft processors or speculative memory access with hardware accelerators in an FPGA setting. Our MMU can use this as a checkpoint: it should prevent such unauthorized speculative memory reads from ever becoming visible. One is speculation-aware access control on memory accesses: the MMU could demand proof of privileges before treating data as cache residents. Flushing or invalidating any speculative results in the MMU's cache should ensure no stateful side effects.

The ML piece could also be applied to security monitoring: learning what constitutes regular access could flag anything unusual that might indicate an attack, such as the atypical branch and memory access sequences used to train and exploit the predictor during specific Spectre attacks. If the MMU's reinforcement-learning (RL) agent observes a sequence flush of cache misses and hits that strongly deviates from learned behavior, it wants to alert or trigger protective mode. This goes to utilizing ML for security anomaly detection, which is a potentially excellent approach but needs to be trained hard not to catch false positives.

6. Flexibility Across Applications and Platforms

6. Adaptability and Use-Case Coverage

One of the key strengths of the proposed ML-driven MMU is its adaptability. We maintain generality to cover a broad spectrum of application domains and FPGA platforms, intentionally avoiding optimizations that could limit its applicability. This section explores how the MMU adapts across a range of real-world scenarios.

6.1. AI Inference

In AI inference, memory access patterns are shaped by typical accelerator behavior: streaming layers, batch operations, large model weights, or random embedding table lookups. The ML-driven MMU can recognize these patterns. For example, an LSTM prefetcher might learn recurring accesses to specific weight matrices and keep them cached [1]. Similarly, an RL agent may learn to prioritize bottlenecked layers and adaptively allocate cache or prefetch capacity [6].

Additionally, the MMU may support data compression—e.g., if 8-bit quantized activations are used, more values can be cached, provided the MMU understands the data type (integer vs. floating-point) and serves the correct format. As new access patterns emerge (e.g., from transformer-based models), the ML module can be retrained or reconfigured. Crucially, this MMU is not hardwired; it can adapt to CNN-style sequential accesses, recommendation system-style sparse lookups, and more. This flexibility makes the MMU a key enabler for scalable AI acceleration on FPGA platforms [20].

6.2. High-Performance Computing (HPC) Applications

HPC workloads on FPGAs, such as stencil computations, graph processing, or physics simulations, exhibit diverse memory requirements. Some workloads are stream-friendly, while others (like pointer-chasing graphs) benefit from parallel banked access.

For streaming workloads (e.g., FFTs, matrix ops), an LSTM can quickly learn simple prefetch patterns and reduce cache misses to near-zero. In contrast, for poor-locality workloads, the MMU might learn that prefetching is wasteful and instead focus its RL policy on managing memory banks—e.g., issuing requests in parallel to different memory interfaces.

Moreover, the MMU can adapt across compute phases. For example, during a compute-dense phase, prefetching might be disabled to conserve bandwidth, whereas it may be re-enabled during a data-gather phase [9]. For deterministic workloads (e.g., MPI-based simulations), the MMU can be toggled into a deterministic policy mode to reduce jitter and guarantee predictable behavior.

6.3. General-Purpose Computing

FPGAs may increasingly support general-purpose computing, especially with RISC-V soft cores or SoC FPGAs. In such settings, the MMU can function similarly to a CPU’s MMU, but with the added intelligence of predictive and adaptive behavior.

For instance, if a program repetitively triggers a page fault, the ML-MMU can preemptively allocate memory pages or migrate data from host memory to local FPGA memory. Although this work focuses on on-chip memory, the concept extends to unified memory systems, including paging to SSD or HBM [19].

6.4. Flexibility Across FPGA Platforms

FPGAs range from low-power edge devices to high-throughput data center FPGAs. Our MMU is scalable and portable. On smaller devices, it may use a simplified TLB, a smaller cache, and a lightweight ML model (e.g., a perceptron instead of an LSTM) [5]. On larger platforms, the MMU can manage multiple memory interfaces (e.g., HBM for random access, DDR for sequential access), with the RL agent learning optimal routing [21].

Portability is ensured via vendor-neutral building blocks like BRAM (for TLBs) or DSP slices (for ML logic). The modular design ensures vendor and resource adaptability, spanning Intel, Xilinx, and other architectures [2,10].

6.5. Partial Reconfiguration and On-the-Fly Updates

FPGAs support partial reconfiguration, allowing parts of the chip to be reprogrammed while others continue operating. This can be used to swap in a new ML model or policy without disturbing the system [11]. For example, one might upgrade from an LSTM to a Transformer-based prefetcher.

This makes field upgrades feasible: workloads can evolve, and so can memory management strategies. In deployed systems, memory access traces can be gathered, used for offline training, and deployed via weight updates or new bitstreams. The MMU becomes a live-learning, field-upgradable component—a powerful notion for adaptive hardware.

7. Conclusion

We discussed a complete vision of ML-driven MMU and FPGA architecture that drafts integration of ideas from computer architecture, machine learning, and security. Our proposed MMU is an intelligent layer that enhances an FPGA's memory system by learning and predicting memory access patterns, enabling performance (lower latency, higher throughput) and efficiency enhancements. The layered architecture and how this ML module (with RL and LSTM capabilities) interacts with typical MMU components like TLBs, and caches were also discussed. We explained that such a system could learn optimal caching and prefetching strategies that beat fixed heuristics, referring to evidence from previous work in related areas that indicates considerable improvements are possible. We also touched on the critical topic of security, describing how adding ML and complexity to the MMU does not introduce an attack surface but helps close it via adaptive defenses and cryptographic safeguards. We underlined the versatility of our design — the same design can be applied to other environments and FPGAs, and the same intelligent MMU, tuned or trained, can be used to various environments, which is, in fact, a unique perspective in providing a unified memory management solution for reconfigurable computing [2,3].

In conclusion, ML-enabled MMUs are a potent union of high-level adaptive intelligence winged together on a low-level hardware float. As FPGAs increasingly take on traditional roles performed by CPUs, including these sophisticated subsystems, it will be crucial to unlock their full potential in general-purpose computing. We envision this work providing comprehensive conceptual groundwork for intelligent memory management in reconfigurable devices and establishing groundwork for future implementations and innovations in this area.

References

- Jain, S., Alam, S., & Kothari, P. (2021). Hardware prefetching using long short-term memory (LSTM) neural networks for improved cache performance. Lehigh University. Retrieved from https://preserve.lehigh.edu.

- Köhler, M., Hönig, T., Schröder-Preikschat, W., & Lohmann, D. (2018). Memory management for FPGA-based computing systems. CiteSeerX. Retrieved from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu.

- Poeplau, S., Kasper, M., & Bohm, C. (2022). A memory hierarchy protected against side-channel attacks. MDPI Electronics, 11(6), 954. [CrossRef]

- Parikh, R., & Parikh, K. (2025). A survey on AI-augmented secure RTL design for hardware Trojan prevention. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Parikh, R., & Parikh, K. (2025). Mathematical foundations of AI-based secure physical design verification. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Ipek, E., Mutlu, O., Kandemir, M., & Burger, D. (2008). Self-optimizing memory controllers: A reinforcement learning approach. Carnegie Mellon University. [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, M., & Wenisch, T. (2019). Do OS abstractions make sense on FPGAs? USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI). Retrieved from https://www.usenix.org.

- Parikh, R., & Parikh, K. (2025). AI-driven security in streaming scan networks (SSN) for design-for-test (DFT). Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y., Zhang, X., Li, X., & Yuan, J. (2022). ML-CLOCK: Efficient page cache algorithm based on perceptron neural networks. Electronics, 10(20), 2503. [CrossRef]

- AMD Documentation. (2021). Memory Management Unit (MMU) - UG585. AMD Research. Retrieved from https://docs.amd.com.

- USC Data Science Lab. (2023). ML-driven memory prefetching for high-performance computing. USC Research. Retrieved from https://sites.usc.edu.

- Parikh, R., & Parikh, K. (2025). Survey on hardware security: PUFs, Trojans, and side-channel attacks. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Northeastern University. (2020). Optimizing the use of different memory types on modern FPGAs. Northeastern University Library Repository. Retrieved from https://repository.library.northeastern.edu.

- AMD Research Team. (2021). Genetic cache: A machine learning approach to designing DRAM cache controllers. ACM Transactions on Architecture and Code Optimization, 18(4), 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Kong, J. (2017). Traditional MMU architecture and performance analysis. ResearchGate. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net.

- GeeksforGeeks. (2022). Optimal page replacement algorithm. GeeksforGeeks. Retrieved from https://www.geeksforgeeks.org.

- Yan, M., Sogabe, T., & Tan, R. (2021). Adversarial Prefetch: New Cross-Core Cache Side Channel Attacks. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- USC Data Science Lab. (2022). Compressed LSTM for efficient memory prefetching in FPGA-based systems. USC Research. Retrieved from https://sites.usc.edu.

- Chen, H., Wang, F., & Liu, P. (2023). Hybrid computing systems: Exploring CPU-FPGA integration for workload acceleration. USENIX Symposium on High-Performance Computing (HPC). Retrieved from https://www.usenix.org.

- Li, Y., Zhang, X., & Zhang, Y. (2023). A high-performance FPGA-based depthwise separable convolution accelerator. Electronics, 12(7), 1571. [CrossRef]

- Intel Research. (2022). High-performance FPGA memory controllers with ML-driven caching. Intel Technical Reports. Retrieved from https://intel.com.

- FPGA Research Group. (2023). A unified MMU framework for adaptive caching and memory virtualization. CiteSeerX.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).