Submitted:

24 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

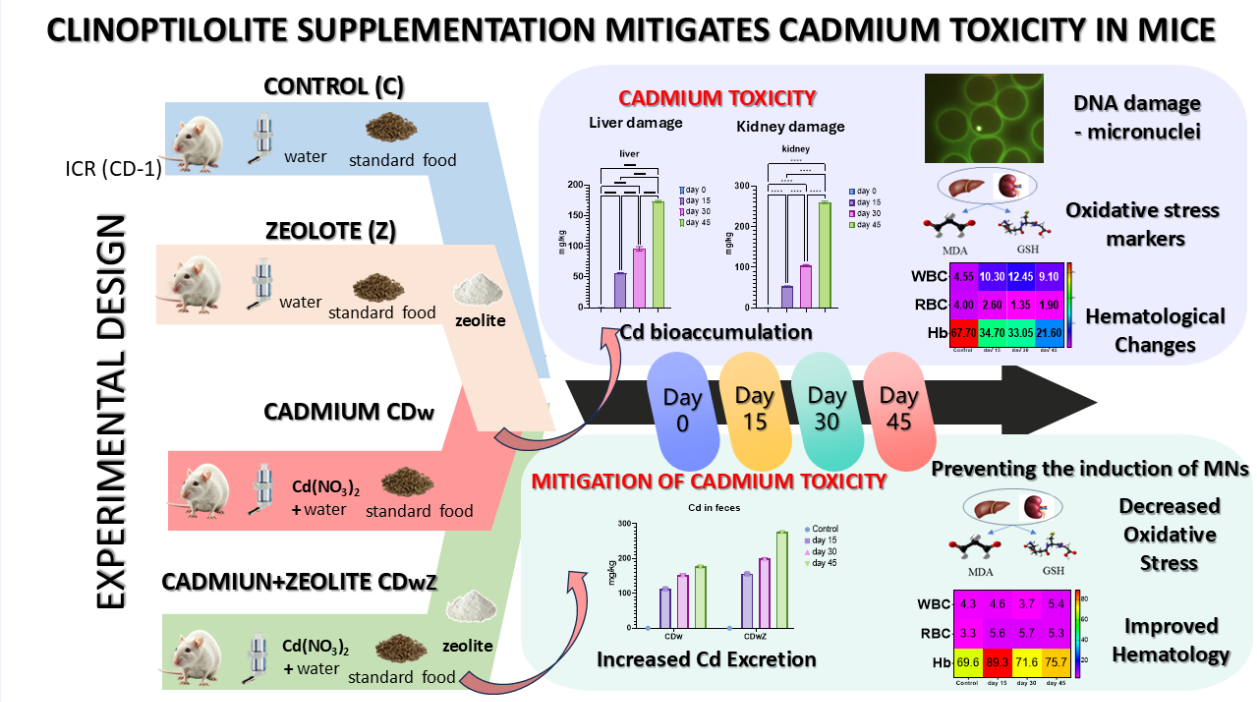

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

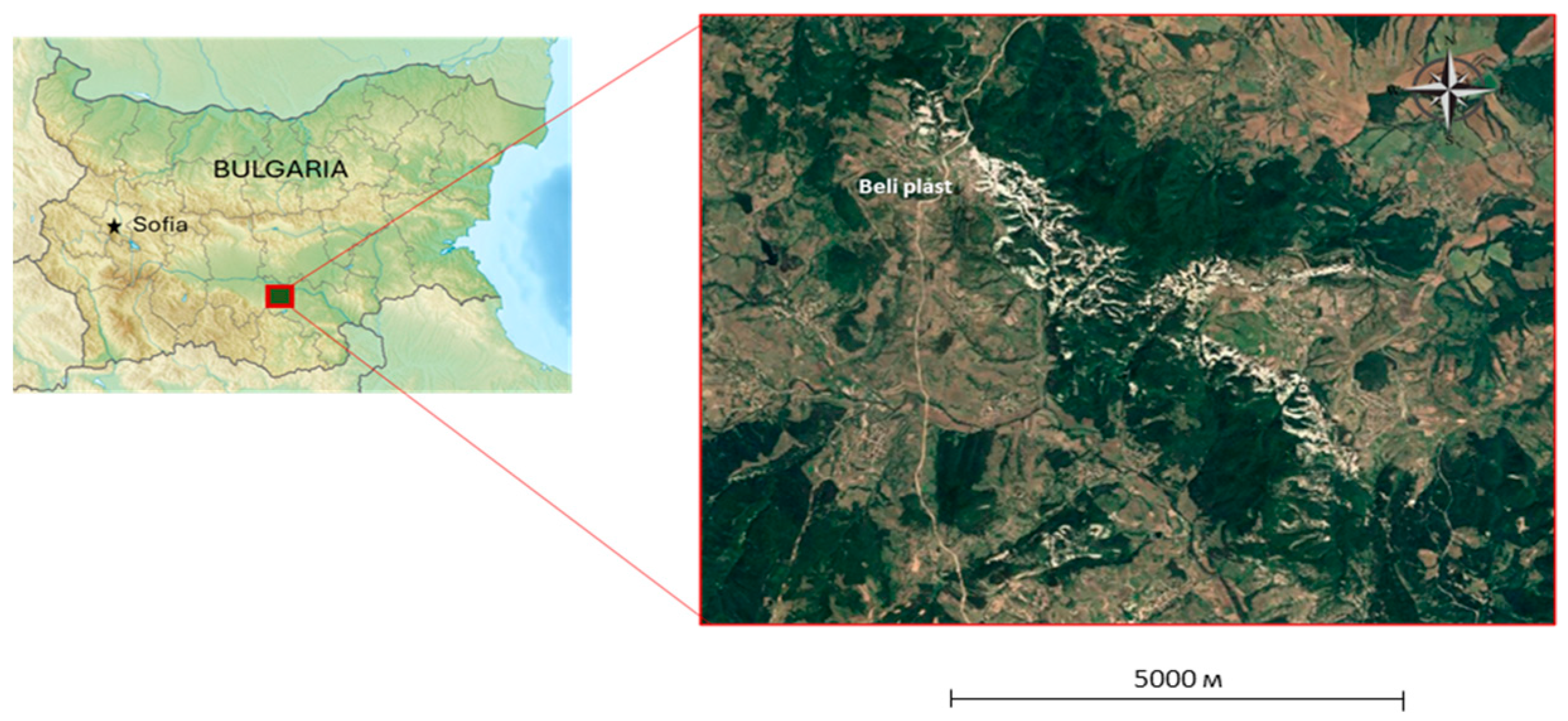

2.1. Clinoptilolite

2.1.1. Samples Collection

2.1.2. Preparation of Na-Exchanged Clinoptilolite Sorbent

2.1.3. Characterization Methods

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Experimental Animals and Husbandry

2.4. Heavy Metal Loading

2.5. Weight and Organ Index Assays

2.6. Hematology

2.7. Oxidative Stress Markers

2.8. Micronucleus Test

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

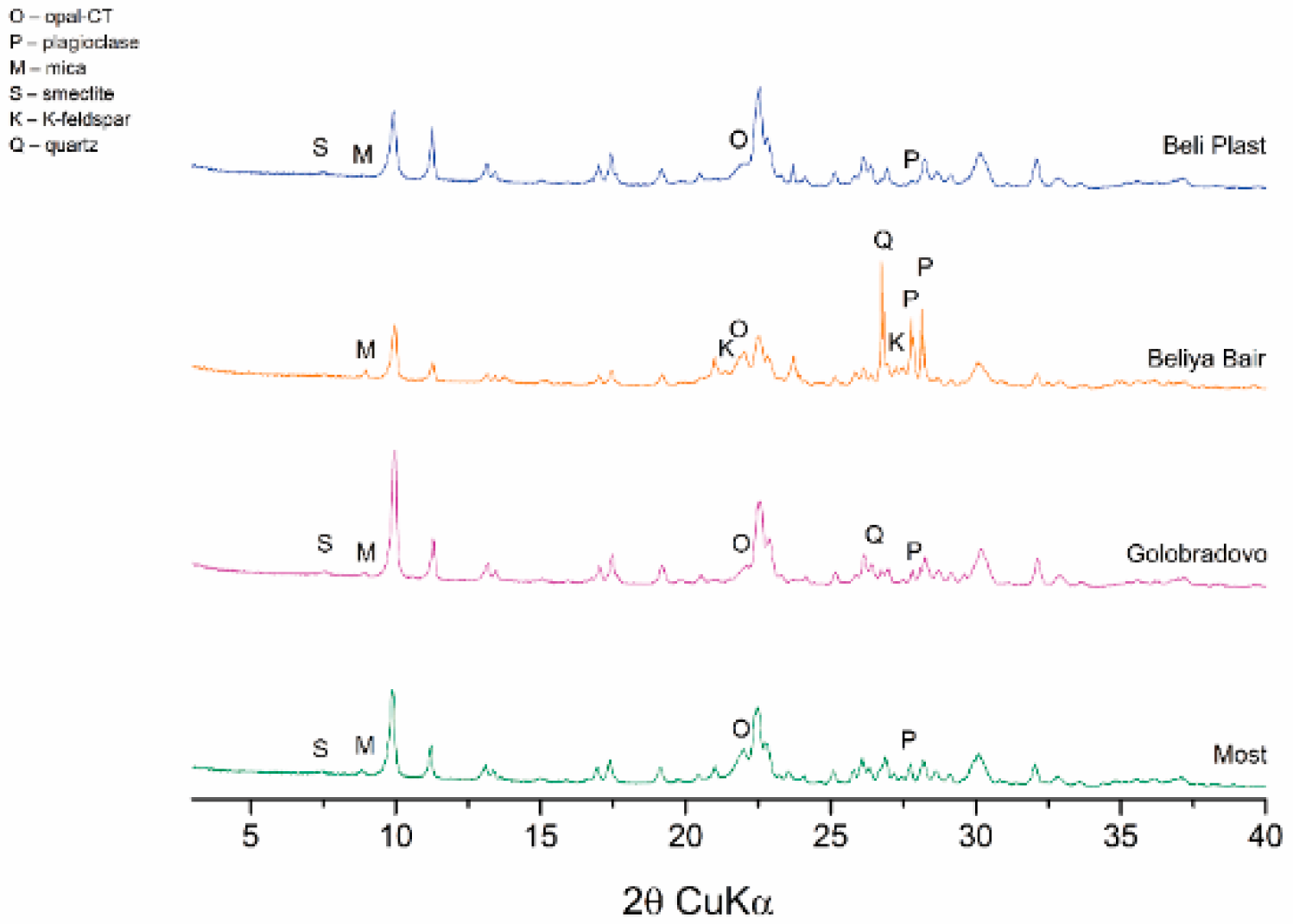

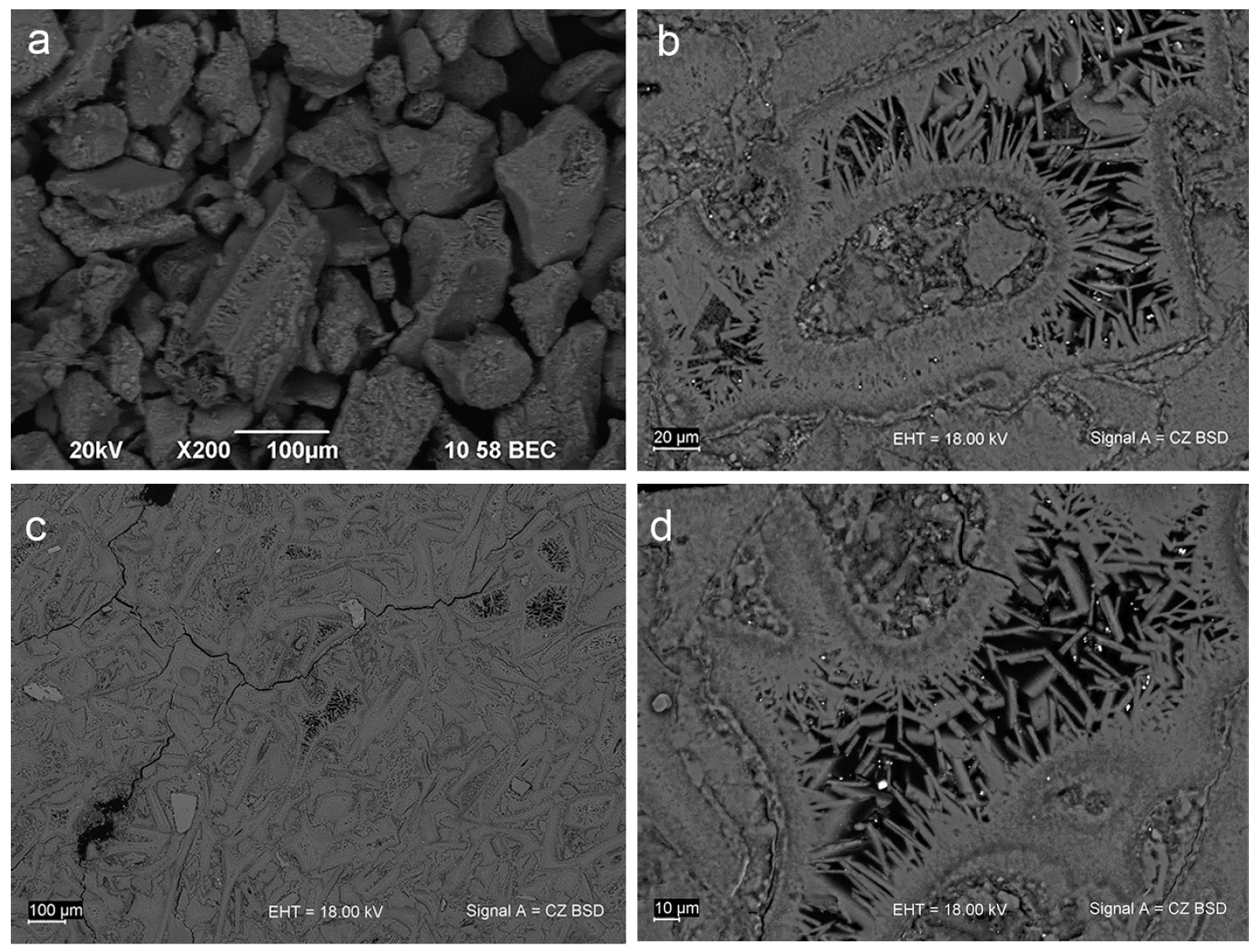

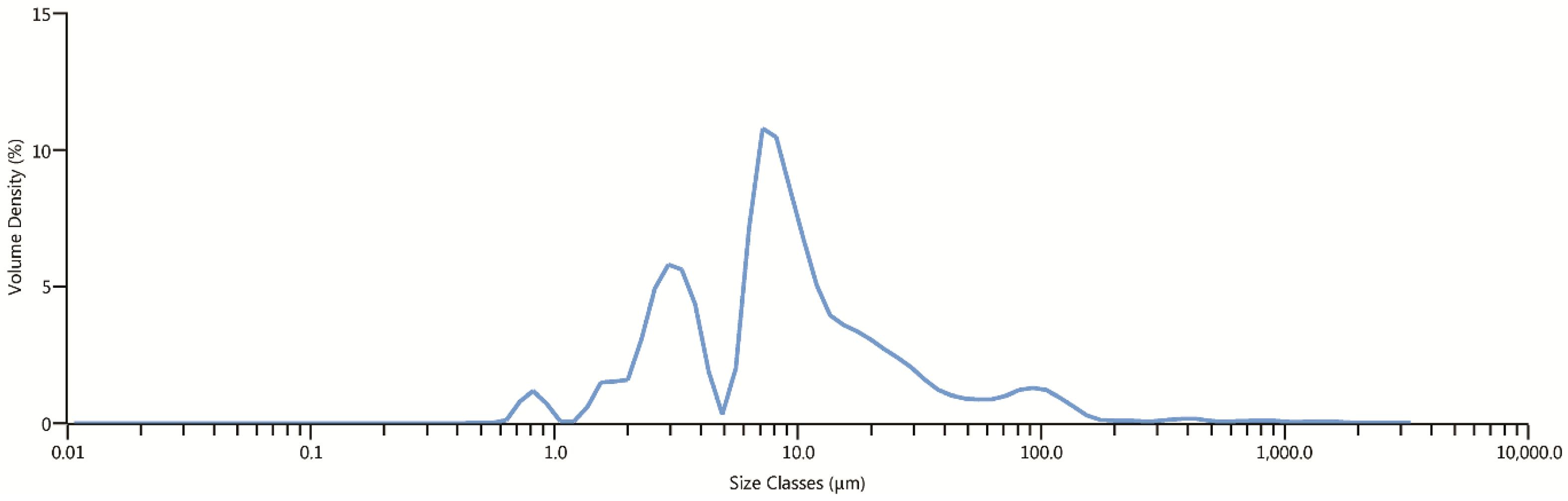

3.1. Characterization of the Natural and Na-Exchanged Clinoptilolite Tuff

3.2. Heavy Metal Bioaccumulation

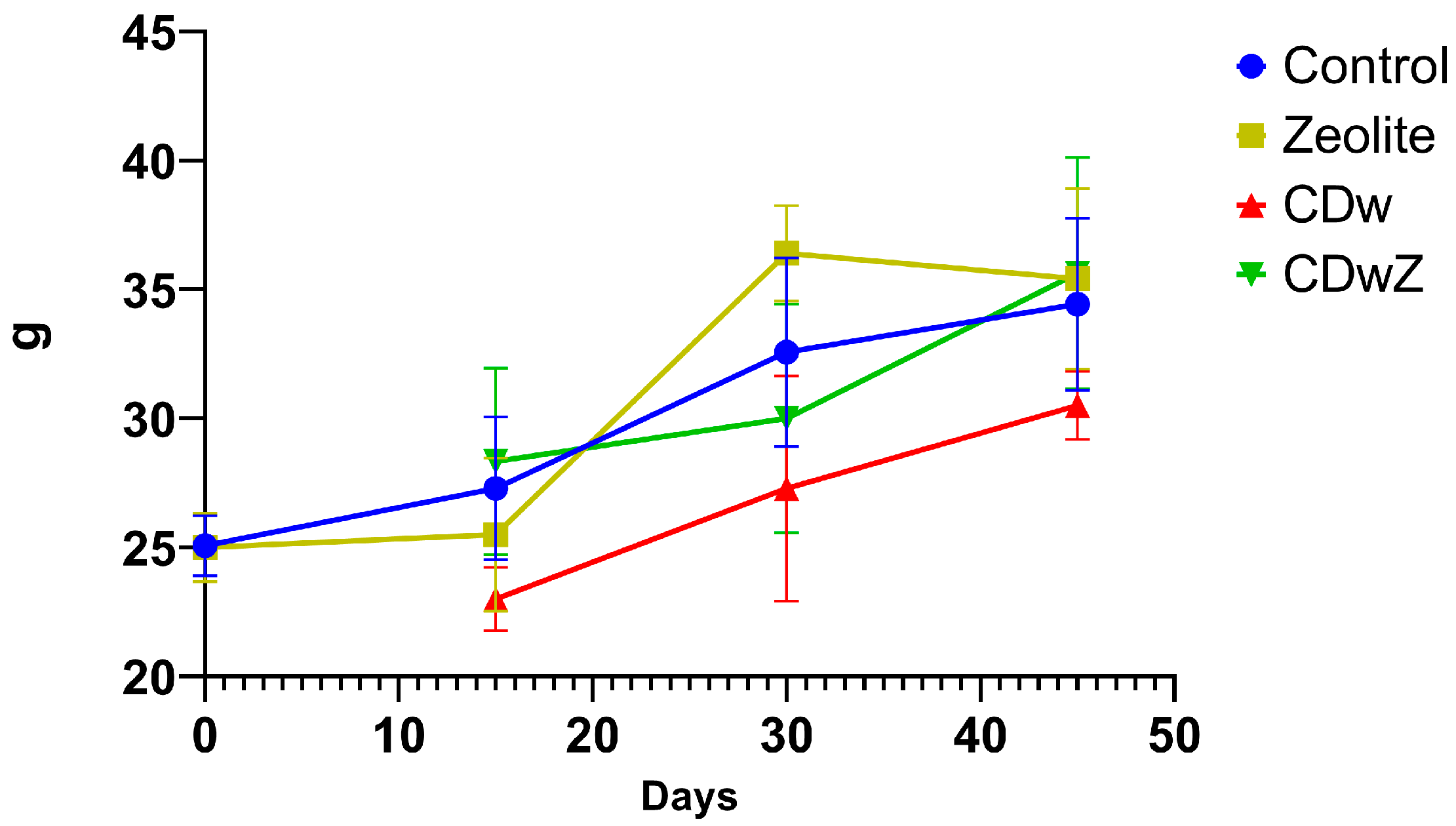

3.3. Growth Rate

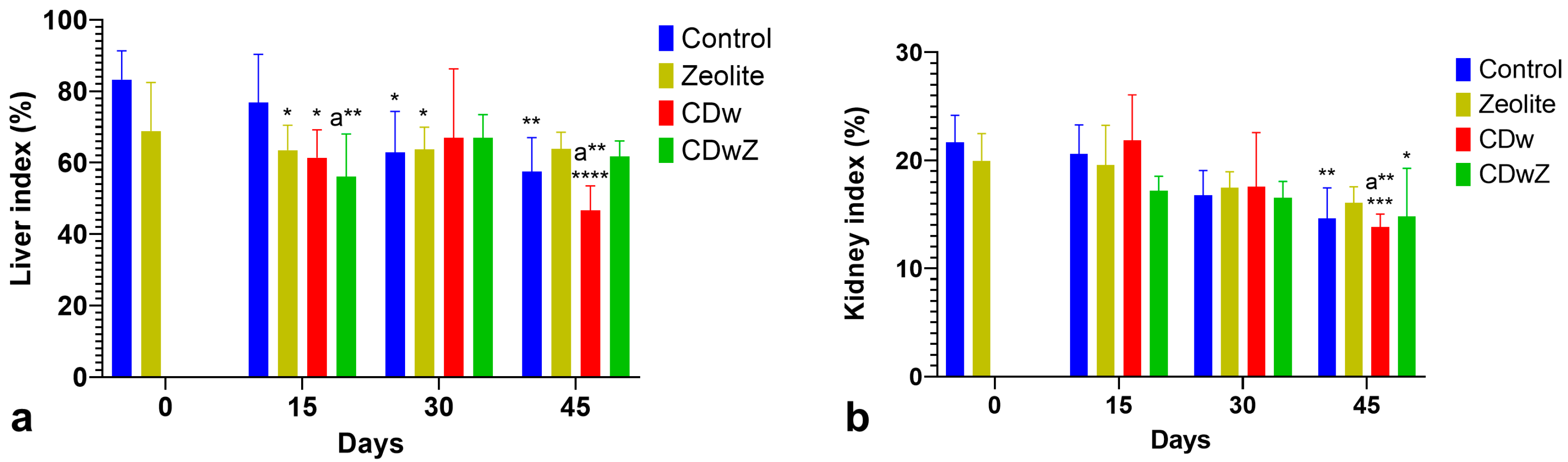

3.4. Organ Index Changes

3.5. Hematology

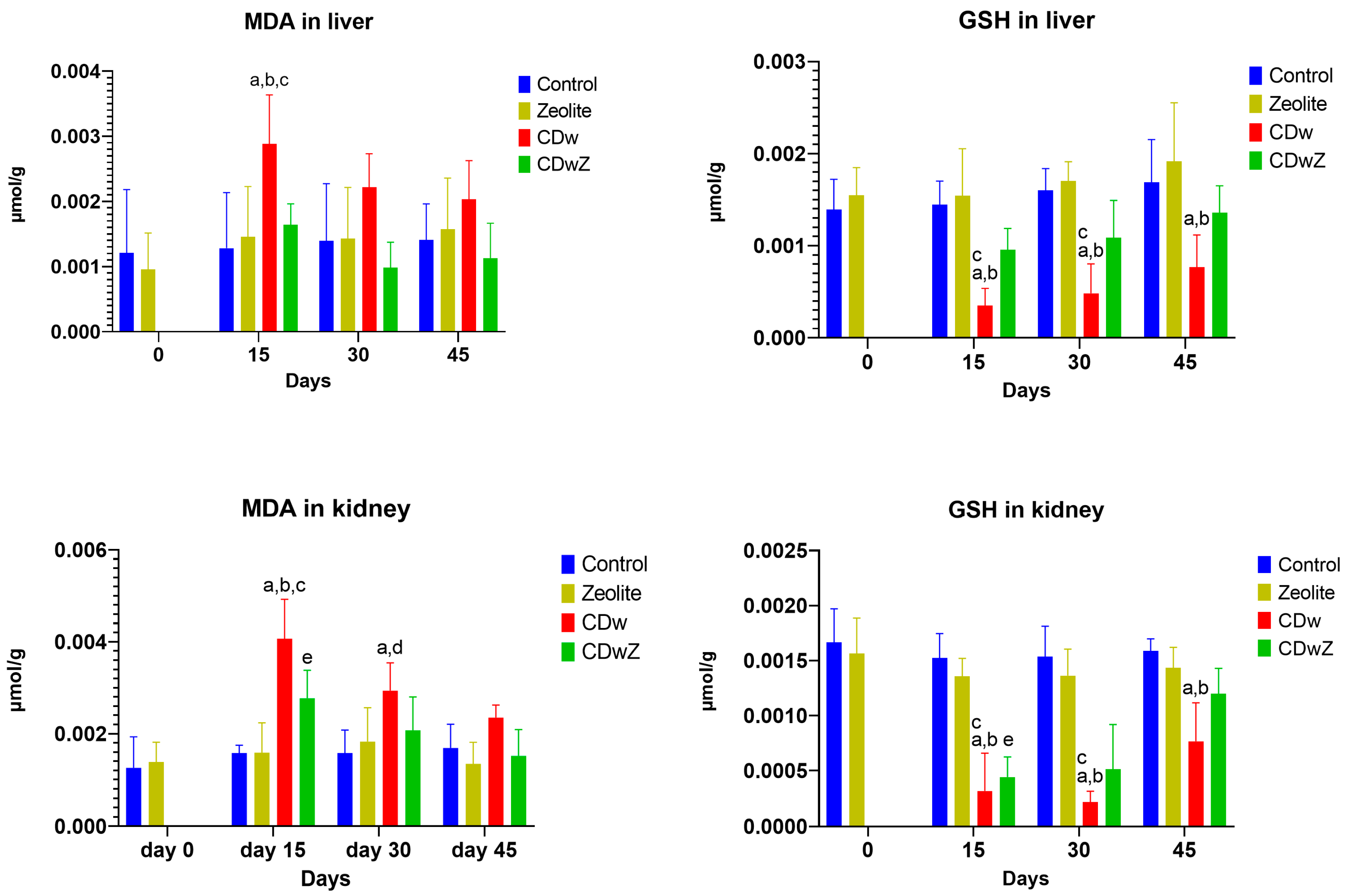

3.6. Oxidative Stress

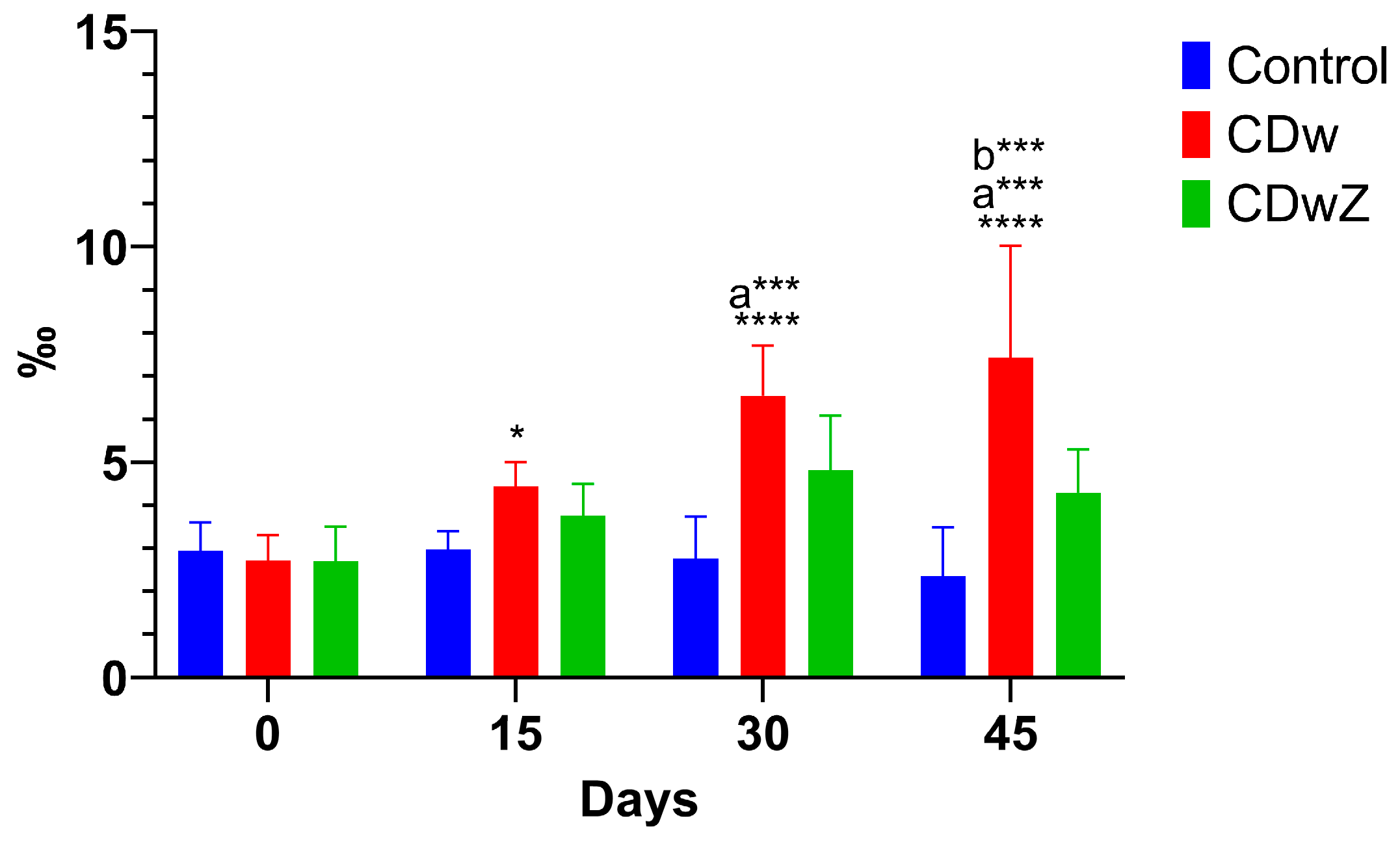

3.7. Micronucleus Test

4. Discussion

4.1. Sorption Properties of Modified Natural Zeolite-Clinoptilolite

4.1. Cadmium Toxicity and Bioaccumulation

4.2. Growth Rate

4.3. Hematology

4.4. Oxidative Stress

4.5. Genotoxic Effects

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martinez-Morata, I.; Sobel, M.; Tellez-Plaza, M.; Navas-Acien, A.; Howe, C.G.; Sanchez, T.R. A State-of-the-Science Review on Metal Biomarkers. Curr Environ Health Rep 2023, 10, 215–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumpton, F.A. La Roca Magica : Uses of Natural Zeolites in Agriculture and Industry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1999, 96, 3463–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bish, D.L.; Ming, D. Reviews in Mineralogy & Geochemistry: Occurrence, Properties, Applications. Natural Zeolites 2001, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, D.S.; Alberti, A.; Armbruster, T.; Artioli, G.; Colella, C.; Galli, E.; Grice, J.D.; Liebau, F.; Mandarino, J.A.; Minato, H.; et al. Recommended Nomenclature for Zeolite Minerals: Report of the Subcommittee on Zeolites of the International Mineralogical Association, Commission on New Minerals and Mineral Names. Mineral Mag 1998, 62, 533–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doebelin, N.; Armbruster, T. Stepwise Dehydration and Change of Framework Topology in Cd-Exchanged Heulandite. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2003, 61, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, A.B.; Slaughter, M. Determination and Refinement of the Structure of Heulandite. American Mineralogist: Journal of Earth and Planetary Materials 1968, 53, 1120–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, A. The Crystal Structure of Two Clinoptilolites. TMPM Tschermaks Mineralogische und Petrographische Mitteilungen 1975, 22, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, K.; Takeuchi, Y. Clinoptilolite: The Distribution of Potassium Atoms and Its Role in Thermal Stability. Z Kristallogr Cryst Mater 1977, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J.W.; Bish, D.L. Equilibrium in the Clinoptilolite-H 2 O System. American Mineralogist 1996, 81, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, T.; Gunter, M.E. Stepwise Dehydration of Heulandite-Clinoptilolite from Succor Creek, Oregon, USA: A Single-Crystal X-Ray Study at 100 K. American Mineralogist 1991, 76, 1872–1888. [Google Scholar]

- Langella, A.; Pansini, M.; Cappelletti, P.; de Gennaro, B.; de’ Gennaro, M.; Colella, C. Cu2+, Zn2+, Cd2+ and Pb2+ Exchange for Na+ in a Sedimentary Clinoptilolite, North Sardinia, Italy. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2000, 37, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksiev, B.; Djourova, E.G. On the Origin of Zeolite Rocks. C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 1975, 28, 517–520. [Google Scholar]

- Aleksiev, B.; Djourova, E.G. Mordenite Zeolitites from the Northeastern Rhodopes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1976, 29, 865–867. [Google Scholar]

- Yanev, Y.; Cochemé, J.J.; Ivanova, R.; Grauby, O.; Burlet, E.; Pravchanska, R. Zeolites and Zeolitization of Acid Pyroclastic Rocks from Paroxysmal Paleogene Volcanism, Eastern Rhodopes, Bulgaria. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie - Abhandlungen 2006, 182, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanev, Y.; Ivanova, R. Mineral Chemistry of the Collision-Related Acid Paleogene Volcanic Rocks of the Eastern Rhodopes, Bulgaria. Geochemistry, Mineralogy and Petrology 2010, 48, 39–65. [Google Scholar]

- Dolanc, I.; Ferhatović Hamzić, L.; Orct, T.; Micek, V.; Šunić, I.; Jonjić, A.; Jurasović, J.; Missoni, S.; Čoklo, M.; Pavelić, S.K. The Impact of Long-Term Clinoptilolite Administration on the Concentration Profile of Metals in Rodent Organisms. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltcheva, M.; Metcheva, R.; Popov, N.; Teodorova, S.E.; Heredia-Rojas, J.A.; Rodríguez-de la Fuente, A.O.; Rodríguez-Flores, L.E.; Topashka-Ancheva, M. Modified Natural Clinoptilolite Detoxifies Small Mammal’s Organism Loaded with Lead I. Lead Disposition and Kinetic Model for Lead Bioaccumulation. Biol Trace Elem Res 2012, 147, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topashka-Ancheva, M.; Beltcheva, M.; Metcheva, R.; Rojas, J.A.H.; Rodriguez-De la Fuente, A.O.; Gerasimova, T.; Rodríguez-Flores, L.E.; Teodorova, S.E. Modified Natural Clinoptilolite Detoxifies Small Mammal’s Organism Loaded with Lead II: Genetic, Cell, and Physiological Effects. Biol Trace Elem Res 2012, 147, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcheva R, B.M. Zeolites versus Lead Toxicity. J Bioequivalence Bioavailab 2015, 07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraljević Pavelić, S.; Simović Medica, J.; Gumbarević, D.; Filošević, A.; Pržulj, N.; Pavelić, K. Critical Review on Zeolite Clinoptilolite Safety and Medical Applications in Vivo. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Ahmad, H.; Wang, T. Effects of Clinoptilolite on Growth Performance and Antioxidant Status in Broilers. Biol Trace Elem Res 2013, 155, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montinaro, M.; Uberti, D.; Maccarinelli, G.; Bonini, S.A.; Ferrari-Toninelli, G.; Memo, M. Dietary Zeolite Supplementation Reduces Oxidative Damage and Plaque Generation in the Brain of an Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Model. Life Sci 2013, 92, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trottier, B.; Athot, J.; Ricard, A.C.; Lafond, J. Maternal–Fetal Distribution of Cadmium in the Guinea Pig Following a Low Dose Inhalation Exposure. Toxicol Lett 2002, 129, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Xu, S. Cadmium-Induced Oxidative Stress Promotes Apoptosis and Necrosis through the Regulation of the MiR-216a-PI3K/AKT Axis in Common Carp Lymphocytes and Antagonized by Selenium. Chemosphere 2020, 258, 127341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Nie, G.; Yang, F.; Chen, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Dai, X.; Liao, Z.; Yang, Z.; Cao, H.; Xing, C.; et al. Molybdenum and Cadmium Co-Induce Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis through Mitochondria-Mediated Pathway in Duck Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells. J Hazard Mater 2020, 383, 121157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Chen, Z.; Song, W.; Hong, D.; Huang, L.; Li, Y. A Review on Cadmium Exposure in the Population and Intervention Strategies Against Cadmium Toxicity. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 2021, 106, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Reynolds, M. Cadmium Exposure in Living Organisms: A Short Review. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 678, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genchi, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Lauria, G.; Carocci, A.; Catalano, A. The Effects of Cadmium Toxicity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemir, F.M.; Caglayan, C.; Darendelioğlu, E.; Küçükler, S.; İzol, E.; Kandemir, Ö. Modulatory Effects of Carvacrol against Cadmium-Induced Hepatotoxicity and Nephrotoxicity by Molecular Targeting Regulation. Life Sci 2021, 277, 119610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, C.D.; Liu, J.; Diwan, B.A. Metallothionein Protection of Cadmium Toxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2009, 238, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.; Aziz, A.T.; Saggu, S.; VanWert, A.L.; Zidan, N.; Saggu, S. Additive Toxic Effect of Deltamethrin and Cadmium on Hepatic, Hematological, and Immunological Parameters in Mice. Toxicol Ind Health 2017, 33, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saggu, S.; Rehman, H.; Aziz, A.T.; Alzeibr, F.M.A.; Oyouni, A.A.A.; Zidan, N.; Panneerselvam, C.; Trivedi, S. Cymbopogon Schoenanthus (Ethkher) Ameliorates Cadmium Induced Toxicity in Swiss Albino Mice. Saudi J Biol Sci 2019, 26, 1875–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, A.; Darma, A.I.; Abdullahi, I.L.; Musa, B.U.; Imam, F.A. Heavy Metals Mixture Affects the Blood and Antioxidant Defense System of Mice. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2023, 11, 100340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bist, P.; Singh, D.; Choudhary, S. Blood Metal Levels Linked with Hematological, Oxidative, and Hepatic-Renal Function Disruption in Swiss Albino Mice Exposed to Multi-Metal Mixture. Comp Clin Path 2023, 32, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amedu, N.O.; Omotoso, G.O. Evaluating the Role of Vitexin on Hematologic and Oxidative Stress Markers in Lead-Induced Toxicity in Mice. Toxicol Environ Health Sci 2020, 12, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Bashir, S.; Mumtaz, S.; Shakir, H.A.; Ara, C.; Ahmad, F.; Tahir, H.M.; Faheem, M.; Irfan, M.; Masih, A.; et al. Evaluation of Cadmium Chloride-Induced Toxicity in Chicks Via Hematological, Biochemical Parameters, and Cadmium Level in Tissues. Biol Trace Elem Res 2021, 199, 3457–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matović, V.; Buha, A.; Ðukić-Ćosić, D.; Bulat, Z. Insight into the Oxidative Stress Induced by Lead and/or Cadmium in Blood, Liver and Kidneys. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2015, 78, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q. Protective Effect of Melatonin against Chronic Cadmium-Induced Hepatotoxicity by Suppressing Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis in Mice. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2021, 228, 112947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, R.K.; Anderson, M.E.; Meister, A. Glutathione, a First Line of Defense against Cadmium Toxicity. The FASEB Journal 1987, 1, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupina, K.; Goginashvili, A.; Cleveland, D.W. Causes and Consequences of Micronuclei. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2021, 70, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapisso, J.T.; Marques, C.C.; Mathias, M. da L.; Ramalhinho, M. da G. Induction of Micronuclei and Sister Chromatid Exchange in Bone-Marrow Cells and Abnormalities in Sperm of Algerian Mice (Mus Spretus) Exposed to Cadmium, Lead and Zinc. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis 2009, 678, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitkovska, V.I.; Dimitrov, H.A.; Chassovnikarova, T.G. Chronic Exposure to Lead and Cadmium Pollution Results in Genomic Instability in a Model Biomonitor Species (Apodemus Flavicollis Melchior, 1834). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2020, 194, 110413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çelik, A.; Mazmanci, B.; Çamlica, Y.; Aşkin, A.; Çömelekoğlu, Ü. Induction of Micronuclei by Lambda-Cyhalothrin in Wistar Rat Bone Marrow and Gut Epithelial Cells. Mutagenesis 2005, 20, 235–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, A.; Büyükakilli, B.; Çimen, B.; Taşdelen, B.; Öztürk, M.İ.; Eke, D. Assessment of Cadmium Genotoxicity in Peripheral Blood and Bone Marrow Tissues of Male Wistar Rats. Toxicol Mech Methods 2009, 19, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahmy, M.A. .; Aly, F.A. In Vivo and in Vitro Studies on the Genotoxicity of Cadmium Chloride in Mice. Journal of Applied Toxicology: An International Journal 2000, 20, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belliardo, C.; Di Giorgio, C.; Chaspoul, F.; Gallice, P.; Bergé-Lefranc, D. Direct DNA Interaction and Genotoxic Impact of Three Metals: Cadmium, Nickel and Aluminum. J Chem Thermodyn 2018, 125, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltcheva, M.; Ostoich, P.; Aleksieva, I.; Metcheva, R. Natural Zeolites as Detoxifiers and Modifiers of the Biological Effects of Lead and Cadmium in Small Rodents: A Review. BioRisk 2022, 17, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA Heavy Metal Emissions in Europe.

- Ramezani, M.; Enayati, M.; Ramezani, M.; Ghorbani, A. A Study of Different Strategical Views into Heavy Metal(Oid) Removal in the Environment. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2021, 14, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, D.; Maiti, S.K. Sources, Bioaccumulation, Health Risks and Remediation of Potentially Toxic Metal(Loid)s (As, Cd, Cr, Pb and Hg): An Epitomised Review. Environ Monit Assess 2020, 192, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 744/2012 Annexes I and II to Directive 2002/32/EC of the European Parliament and the Council as Regards Maximum Levels for Arsenic, Fluorine, Lead, Mercury, Endosulfan, Dioxins, Ambrosia Spp., Diclazuril and Lasalocid A Sodium and Action Thresholds for Dioxins, Official J. of the EU, 1–8.

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 651/2013 The Authorisation of Clinoptilolite of Sedimentary Origin as a Feed Additive for All Animal Species and Amending Regulation (EC) No 1810/2005, Official J. of the EU, 1–3.

- Stefanova, I.; Djurova, E.; Gradev, G. Sorption of Zinc and Cadmium on Zeolite Rocks. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry Letters 1988, 128, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoff, S.; Auborn, K.; Marmar, J.L.; Hurley, I.R. Link between Low-Dose Environmentally Relevant Cadmium Exposures and Asthenozoospermia in a Rat Model. Fertil Steril 2008, 89, e73–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caflisch, C.R. Effect of Orally Administered Cadmium on in Situ PH, PCO 2, and Bicarbonate Concentration in Rat Testis and Epididymis. J Toxicol Environ Health 1994, 42, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Nam, J.H.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, K.S.; Hwang, D.Y. Annual Tendency of Research Papers Used ICR Mice as Experimental Animals in Biomedical Research Fields. Lab Anim Res 2017, 33, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friberg, L. Cadmium and the Kidney. Environ Health Perspect 1984, 54, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şehirli, Ö.; Tozan, A.; Omurtag, G.Z.; Cetinel, S.; Contuk, G.; Gedik, N.; Şener, G. Protective Effect of Resveratrol against Naphthalene-Induced Oxidative Stress in Mice. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2008, 71, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; MacGregor, J.T.; Gatehouse, D.G.; Adler, I.-D.; Blakey, D.H.; Dertinger, S.D.; Krishna, G.; Morita, T.; Russo, A.; Sutou, S. In Vivo Rodent Erythrocyte Micronucleus Assay. II. Some Aspects of Protocol Design Including Repeated Treatments, Integration with Toxicity Testing, and Automated Scoring. Environ Mol Mutagen 2000, 35, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, R.L.; Gao, S. Composition of the Continental Crust. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 1–51.

- Tzvetanova, Y.; Tacheva, E.; Dimowa, L.; Tsvetanova, L.; Nikolov, A. Trace Elements in the Clinoptilolite Tuffs from Four Bulgarian Deposits, Eastern Rhodopes. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 2023, 84, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apreutesei, R.E.; Catrinescu, C.; Teodosiu, C. SURFACTANT-MODIFIED NATURAL ZEOLITES FOR ENVIRONMENTAL APPLICATIONS IN WATER PURIFICATION. Environ Eng Manag J 2008, 7, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraljević Pavelić, S.; Micek, V.; Filošević, A.; Gumbarević, D.; Žurga, P.; Bulog, A.; Orct, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Preočanin, T.; Plavec, J.; et al. Novel, Oxygenated Clinoptilolite Material Efficiently Removes Aluminium from Aluminium Chloride-Intoxicated Rats in Vivo. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2017, 249, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances Used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP). Scientific Opinion on the Safety and Efficacy of Clinoptilolite of Sedimentary Origin for All Animal Species. EFSA Journal 2013, 11, 3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltcheva, M.; Tzvetanova, Y.; Todorova, T.; Tsvetanova, L.; Aleksieva, I.; Gerasimova, T.; Chassovnikarova, T. Does Natural Clinoptilolite Induce Toxicity in Small Mammals? Acta Zool Bulg 2024, 76, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Kalinin, I.; Tomchuk, V. Removal of Heavy Metals Using Sorbents and Biochemical Indexes in Rats. Ukrainian journal of veterinary sciences 2023, 14, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Iznaga, I.; Shelyapina, M.G.; Petranovskii, V. Ion Exchange in Natural Clinoptilolite: Aspects Related to Its Structure and Applications. Minerals 2022, 12, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.E.; Olin, T.J.; Bricka, R.M.; Adrian, D.D. A Review of Potentially Low-Cost Sorbents for Heavy Metals. Water Res 1999, 33, 2469–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizidou, M.; Townsend, R.P. Exchange of Cadmium into the Sodium and Ammonium Forms of the Natural Zeolites Clinoptilolite, Mordenite, and Ferrierite. Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions 1987, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen Gupta, S.; Bhattacharyya, K.G. Adsorption of Metal Ions by Clays and Inorganic Solids. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 28537–28586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A.; Gunay, A.; Debik, E. Ammonium Removal from Aqueous Solution by Ion-Exchange Using Packed Bed Natural Zeolite. Water SA 2002, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Peng, Y. Natural Zeolites as Effective Adsorbents in Water and Wastewater Treatment. Chemical Engineering Journal 2010, 156, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C.J. Zeolites: Physical Aspects and Environmental Applications. Annual Reports Section “C” (Physical Chemistry) 2007, 103, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkuna, O.; Leboda, R.; Skubiszewska-Zie¸ba, J.; Vrublevs’ka, T.; Gun’ko, V.M.; Ryczkowski, J. Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Natural Zeolites: Clinoptilolite and Mordenite. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2006, 87, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bist, R.B.; Subedi, S.; Chai, L.; Regmi, P.; Ritz, C.W.; Kim, W.K.; Yang, X. Effects of Perching on Poultry Welfare and Production: A Review. Poultry 2023, 2, 134–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelić, K., H.M. Medical Applications of Zeolites. In Handbook of zeolite science and technology; CRC press., 2003; pp. 1453–1491.

- Kristo, A.S.; Tzanidaki, G.; Lygeros, A.; Sikalidis, A.K. Bile Sequestration Potential of an Edible Mineral (Clinoptilolite) under Simulated Digestion of a High-Fat Meal: An in Vitro Investigation. Food Funct 2015, 6, 3818–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haemmerle, M.M.; Fendrych, J.; Matiasek, E.; Tschegg, C. Adsorption and Release Characteristics of Purified and Non-Purified Clinoptilolite Tuffs towards Health-Relevant Heavy Metals. Crystals (Basel) 2021, 11, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, C.D.; Liu, J.; Choudhuri, S. METALLOTHIONEIN: An Intracellular Protein to Protect Against Cadmium Toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 1999, 39, 267–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsenhans, B.; Strugala, G.; Schäfer, S. Small-Intestinal Absorption of Cadmium and the Significance of Mucosal Metallothionein. Hum Exp Toxicol 1997, 16, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shu, Y. Cadmium Transporters in the Kidney and Cadmium-Induced Nephrotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2015, 16, 1484–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmańczuk, A.; Markiewicz, W.; Burmańczuk, A.; Kowalski, C.; Roliński, Z.; Burmańczuk, N. Possibile Use of Natural Zeolites in Animal Production and Environment Protection. J Elem 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, D.; Katsoulos, P.D.; Panousis, N.; Karatzias, H. The Role of Natural and Synthetic Zeolites as Feed Additives on the Prevention and/or the Treatment of Certain Farm Animal Diseases: A Review. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2005, 84, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraljević Pavelić, S.; Saftić Martinović, L.; Simović Medica, J.; Žuvić, M.; Perdija, Ž.; Krpan, D.; Eisenwagen, S.; Orct, T.; Pavelić, K. Clinical Evaluation of a Defined Zeolite-Clinoptilolite Supplementation Effect on the Selected Blood Parameters of Patients. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świergosz-Kowalewska, R. Cadmium Distribution and Toxicity in Tissues of Small Rodents. Microsc Res Tech 2001, 55, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, C.P.; Lill, A.; Reina, R.D. Use of Erythrocyte Indicators of Health and Condition in Vertebrate Ecophysiology: A Review and Appraisal. Biological Reviews 2017, 92, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powolny, T.; Scheifler, R.; Raoul, F.; Coeurdassier, M.; Fritsch, C. Effects of Chronic Exposure to Toxic Metals on Haematological Parameters in Free-Ranging Small Mammals. Environmental Pollution 2023, 317, 120675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, M.; Akçıl, E. The Effects of Chronic Cadmium Toxicity on the Hemostatic System. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb 2006, 35, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazima, B.; Manoharan, V.; Miltonprabu, S. Oxidative Stress Induced by Cadmium in the Plasma, Erythrocytes and Lymphocytes of Rats. Hum Exp Toxicol 2016, 35, 428–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, D.; Valberg, L. Relationship between Cadmium and Iron Absorption. American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content 1974, 227, 1033–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiguchi, H.; Teranishi, H.; Niiya, K.; Aoshima, K.; Katoh, T.; Sakuragawa, N.; Kasuya, M. Hypoproduction of Erythropoietin Contributes to Anemia in Chronic Cadmium Intoxication: Clinical Study on Itai-Itai Disease in Japan. Arch Toxicol 1994, 68, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolanjiappan, K.; Manoharan, S.; Kayalvizhi, M. Measurement of Erythrocyte Lipids, Lipid Peroxidation, Antioxidants and Osmotic Fragility in Cervical Cancer Patients. Clinica Chimica Acta 2002, 326, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minetti, M.; Pietraforte, D.; Straface, E.; Metere, A.; Matarrese, P.; Malorni, W. Red Blood Cells as a Model to Differentiate between Direct and Indirect Oxidation Pathways of Peroxynitrite. In; 2008; pp. 253–272.

- Demir, H.; Kanter, M.; Coskun, O.; Uz, Y.H.; Koc, A.; Yildiz, A. Effect of Black Cumin (Nigella Sativa) on Heart Rate, Some Hematological Values, and Pancreatic β-Cell Damage in Cadmium-Treated Rats. Biol Trace Elem Res 2006, 110, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Boshy, M.E.; Risha, E.F.; Abdelhamid, F.M.; Mubarak, M.S.; Hadda, T. Ben Protective Effects of Selenium against Cadmium Induced Hematological Disturbances, Immunosuppressive, Oxidative Stress and Hepatorenal Damage in Rats. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 2015, 29, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmez, H.H.; Donmez, N.; Kısadere, I.; Undag, I. Protective Effect of Quercetin on Some Hematological Parameters in Rats Exposed to Cadmium. Biotechnic & Histochemistry 2019, 94, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppasamy, R.; Subathra, S.; Puvaneswari, S. Haematological Responses to Exposure to Sublethal Concentration of Cadmium in Air-Breathing Fish, Channa Punctatus (Bloch). J Environ Biol 2005, 26, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Morsy, A. S.; Manal, M.; Gad-El-Moula, H.; Dooa, O.; Hassan, M. S.; Nagwa, A.A. Blood picture, metabolites and minerals of rabbits as influenced by drinking saline water in Egypt, Global Journal of Advanced Research, 3(11) (2016) 1008-1017.

- Martin-Kleiner, I.; Flegar-Meštrić, Z.; Zadro, R.; Breljak, D.; Stanović Janda, S.; Stojković, R.; Marušić, M.; Radačić, M.; Boranić, M. The Effect of the Zeolite Clinoptilolite on Serum Chemistry and Hematopoiesis in Mice. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2001, 39, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojzis, J.; Nistiar, F.; Kovac, G.; Mojzisova, G. Preventive Effect of Zeolite in VX Poisoning in Rats. Veterinarni medicin 1994, 39, 443–449. [Google Scholar]

- Waisberg, M.; Joseph, P.; Hale, B.; Beyersmann, D. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Cadmium Carcinogenesis. Toxicology 2003, 192, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pond, W. G.; Ming, D. W.; Mumpton, F. A. Zeolites in animal nutrition and health: a review. Natural zeolites 1995, 93, 449. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Qu, W.; Kadiiska, M.B. Role of Oxidative Stress in Cadmium Toxicity and Carcinogenesis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2009, 238, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Liu, S.; Luo, Y.; Pu, J.; Deng, X.; Zhou, W.; Dong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, G.; Yang, F.; et al. Procyanidin B2 Alleviates Uterine Toxicity Induced by Cadmium Exposure in Rats: The Effect of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2023, 263, 115290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Morris, H.; Cronin, M. Metals, Toxicity and Oxidative Stress. Curr Med Chem 2005, 12, 1161–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Qi, K.; Zhang, L.; Bai, Z.; Ren, C.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X. Glutathione Might Attenuate Cadmium-Induced Liver Oxidative Stress and Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation. Biol Trace Elem Res 2019, 191, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Singh, R.; Shekhar, A. Oxidative Stress in Cadmium Toxicity in Animals and Its Amelioration. In Cadmium Toxicity Mitigation; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 391–411. [Google Scholar]

- Souza-Arroyo, V.; Fabián, J.J.; Bucio-Ortiz, L.; Miranda-Labra, R.U.; Gomez-Quiroz, L.E.; Gutiérrez-Ruiz, M.C. The Mechanism of the Cadmium-Induced Toxicity and Cellular Response in the Liver. Toxicology 2022, 480, 153339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saribeyoglu, K.; Aytac, E.; Pekmezci, S.; Saygili, S.; Uzun, H.; Ozbay, G.; Aydin, S.; Seymen, H.O. Effects of Clinoptilolite Treatment on Oxidative Stress after Partial Hepatectomy in Rats. Asian J Surg 2011, 34, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-El-Zahab, H.S.H.; Hamza, R.Z.; Montaser, M.M.; El-Mahdi, M.M.; Al-Harthi, W.A. Antioxidant, Antiapoptotic, Antigenotoxic, and Hepatic Ameliorative Effects of L-Carnitine and Selenium on Cadmium-Induced Hepatotoxicity and Alterations in Liver Cell Structure in Male Mice. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2019, 173, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; He, C.; Shen, C.; Guo, J.; Mubeen, S.; Yuan, J.; Yang, Z. Toxicity of Cadmium and Its Health Risks from Leafy Vegetable Consumption. Food Funct 2017, 8, 1373–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Li, Y.; Shi, L.; Hussain, R.; Mehmood, K.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, H. Heavy Metals Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Animals: Molecular Mechanism of Toxicity. Toxicology 2022, 469, 153136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorova, T.; Alexieva, I.; Ostoich, P.; Dimitrova, M.; Boyadzhiev, K.; Lyubomirova, L.; Beltcheva, M. Different Lead- and Cadmium-Induced Oxidative Stress Profiles in the Liver and Kidneys of Subchronically-Exposed Mice. Acta Zool Bulg 2023, 75, 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Mabbott, N.A.; Donaldson, D.S.; Ohno, H.; Williams, I.R.; Mahajan, A. Microfold (M) Cells: Important Immunosurveillance Posts in the Intestinal Epithelium. Mucosal Immunol 2013, 6, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaiotov, S.; Tancheva, L.; Kalfin, R.; Petkova-Kirova, P. Zeolite and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2024, 29, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Zheng, W. Cadmium Exposure: Mechanisms and Pathways of Toxicity and Implications for Human Health. Toxics 2024, 12, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Du, J.; Ge, J.; Liu, S.-B. DNA Damage-Inducing Endogenous and Exogenous Factors and Research Progress. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2024, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.; Cavalie, I.; Camilleri, V.; Gilbin, R.; Adam-Guillermin, C. Comparative Genotoxicity of Aluminium and Cadmium in Embryonic Zebrafish Cells. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis 2013, 750, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viau, M.; Sonzogni, L.; Ferlazzo, M.L.; Berthel, E.; Pereira, S.; Bodgi, L.; Granzotto, A.; Devic, C.; Fervers, B.; Charlet, L.; et al. DNA Double-Strand Breaks Induced in Human Cells by Twelve Metallic Species: Quantitative Inter-Comparisons and Influence of the ATM Protein. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| SiO2 | TiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3(t) | MnO | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | SO3 | LOI | H2O– | Total | |

| Natural clinoptilolite tuff | 71.08 | 0.12 | 10.88 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 1.03 | 2.78 | 0.31 | 2.76 | 0.15 | 9.3 | 2.31 | 101.77 |

| Na-exchanged sample | 69.42 | 0.14 | 10.63 | 0.82 | 0.08 | 0.58 | 0.9 | 4.26 | 2.46 | 0 | 9.13 | 3.56 | 101.98 |

| Samples Oxides |

P1-17 | P1-19 | P1-12 | P1-13 | P1-14 | P1-15 | P1-16 |

| SiO2 | 69.07 | 70.74 | 66.90 | 68.19 | 66.97 | 67.88 | 68.46 |

| Al2O3 | 12.70 | 12.82 | 13.44 | 13.38 | 13.38 | 12.31 | 12.34 |

| MgO | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.81 |

| CaO | 3.86 | 3.93 | 4.51 | 4.52 | 4.54 | 3.76 | 3.89 |

| Na2O | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.09 |

| K2O | 3.06 | 2.92 | 2.66 | 2.59 | 2.52 | 2.83 | 2.84 |

| Total | 89.69 | 91.45 | 88.50 | 89.66 | 88.39 | 87.77 | 88.43 |

| Atoms per formula unit (apfu) | |||||||

| Si | 29.588 | 29.664 | 29.106 | 29.235 | 29.136 | 29.661 | 29.691 |

| Al | 6.412 | 6.337 | 6.892 | 6.761 | 6.861 | 6.340 | 6.308 |

| Mg | 0.524 | 0.563 | 0.545 | 0.562 | 0.590 | 0.573 | 0.524 |

| Ca | 1.772 | 1.766 | 2.103 | 2.076 | 2.116 | 1.760 | 1.808 |

| Na | 0.150 | 0.114 | 0.127 | 0.083 | 0.059 | 0.093 | 0.076 |

| K | 1.672 | 1.562 | 1.476 | 1.416 | 1.398 | 1.577 | 1.571 |

| Days | Organs | |||||

| CDw (x̅±SD) | CDwZ (x̅±SD) | |||||

| Liver | Kidneys | Feces | Liver | Kidneys | Feces | |

| 0 | 0.3±0.1 | 0.2±0.1 | 0 | 0.3±0.1 | 0.2±0.1 | 0 |

| 15 | 56.2±1.1a,d | 53.1±1.8a | 113.0±2.8a | 44.2±1.6a | 39.1±0.9a | 156.0±3.2a |

| 30 | 96.0±3.6a,b,d | 104.0±12.6 a,b | 153.0±13.4a,b,d | 78.0±12.1a,b | 74.6±11.8a,b | 200.0±22.1a,b |

| 45 | 173.0±11.9a,c,d | 260.0±23.1 a,b,c | 177.0±13.1a,b,c,d | 90.0±12.3a,b,c | 100.0±12.4a,b,c | 276.0±22.6a,b,c |

| Parameters | WBC (g/L) | LYM (109/L) | GR (109/L) | ||||||||||

| Groups | C | Z | CDw | CDwZ | C | Z | CDw | CDwZ | C | Z | CDw | CDwZ | |

| Days | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 4.3± 1.7 |

4.3± 1.7 |

- | - | 3.1± 1.2 |

3.2± 1.2 |

- | - | 2.2± 0.8 |

2.6± 0.9 |

- | - | |

| 15 | 3.7± 1.5 |

3.6± 1.7 |

9.6± 1.9 b, c |

4.6± 2.0 |

3.8± 0.8 |

2.1± 1.2 |

3.8± 1.2 |

2.2± 1.3 |

1.5± 0.4 |

1.1± 0.5 |

1.3± 0.3 |

0.8± 0.5 |

|

| 30 | 6.0± 1.3 |

7.2± 2.2 |

11.7± 2.5 b, c |

6.0± 1.3c |

3.5± 1.4 |

3.8± 1.5 |

2.5± 1.8 |

2.8± 1.4 |

2.1± 0.7 |

2.7± 0.6* |

1.0± 0.6 b |

1.5± 0.7* |

|

| 45 | 6.6± 3.2 |

7.8± 2.1* |

8.1± 3.1 | 10.1± 7.4* |

4.2± 2.7 |

4.4± 1.4 |

3.3± 2.5 |

4.2± 1.0 |

4.0± 2.9* |

2.7± 0.8* |

1.9± 1.5 |

3.2± 1.2*a |

|

| MO (109/L) | RBC (1012/L) | Hb (g/L) | |||||||||||

| 0 | 2.6± 0.14 |

2.8± 0.19 |

- | - | 3.3± 1.3 |

3.7± 1.0 |

- | - | 69.6± 22.1 |

68.3±19.8 | - | - | |

| 15 | 1.1± 0.03 |

1.0± 0.05 |

12.9± 0.22 b |

2.1± 0.06b |

3.7± 0.6 |

3.4± 0.5 |

2.3± 1.5 |

5.6± 1.2 |

54.4± 12.9 |

70.0± 43.5 |

36.3± 24.0 b, c |

45.0± 5.9 |

|

| 30 | 2.6± 0.14 |

0.9± 0.01 |

10.4± 0.62 b |

1.7± 0.03b |

5.3± 2.0 |

3.9± 1.4 |

3.1± 1.9* |

5.7± 3.8 |

81.1± 29.5 |

79.3±2 8.3 |

28.3± 16.6 b, c |

56.0± 25.2 |

|

| 45 | 4.1± 0.26 |

1.1± 0.07 |

12.4± 0.18*a |

2.2± 0.06 |

.9± 2.6* |

4.2± 1.3 |

1.8± 1.2*a, b, c |

5.3± 3.5 |

82.9± 37.3 |

89.3± 10.6 |

22.7± 11.7*b |

69.9± 14.4 b |

|

| Hct (L/L) | MCV (fL) | MCH (pg) | |||||||||||

| 0 | 0.25± 0.09 |

0.24± 0.09 |

- | - | 46.8± 1.6 |

46.8± 1.6 |

- | - | 15.3± 1.0 |

15.3± 1.0 |

- | - | |

| 15 | 0.26± 0.08 |

0.19± 0.06 |

0.22± 0.06 |

0.12± 0.07 |

48.7± 5.4 |

48.8± 6.5 |

42.2± 2.4c |

50.0± 4.4 |

15.6± 1.5 |

15.1± 1.6 |

12.5± 0.3 b, c |

15.5± 1.0c |

|

| 30 | 0.25± 0.12 |

0.19± 0.07 |

0.23± 0.14 |

0.27± 0.09 |

46.8± 1.6 |

48.2± 3.0 |

41.7± 4.1 |

44.4± 3.0 |

15.3± 1.0 |

14.0± 1.2 |

13.0± 1.1 b |

13.7± 0.7 |

|

| 45 | 0.26± 011 |

0.21± 0.05 |

0.24± 0.15 |

0.07± 0.04a |

44.0± 4.5 |

50.4± 1.3 |

44.7± 3.5 |

41.9± 2.7b |

14.0± 1.8 |

14.9± 0.5 |

13.5± 3.0 |

14.2± 1.3 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).