1. Introduction

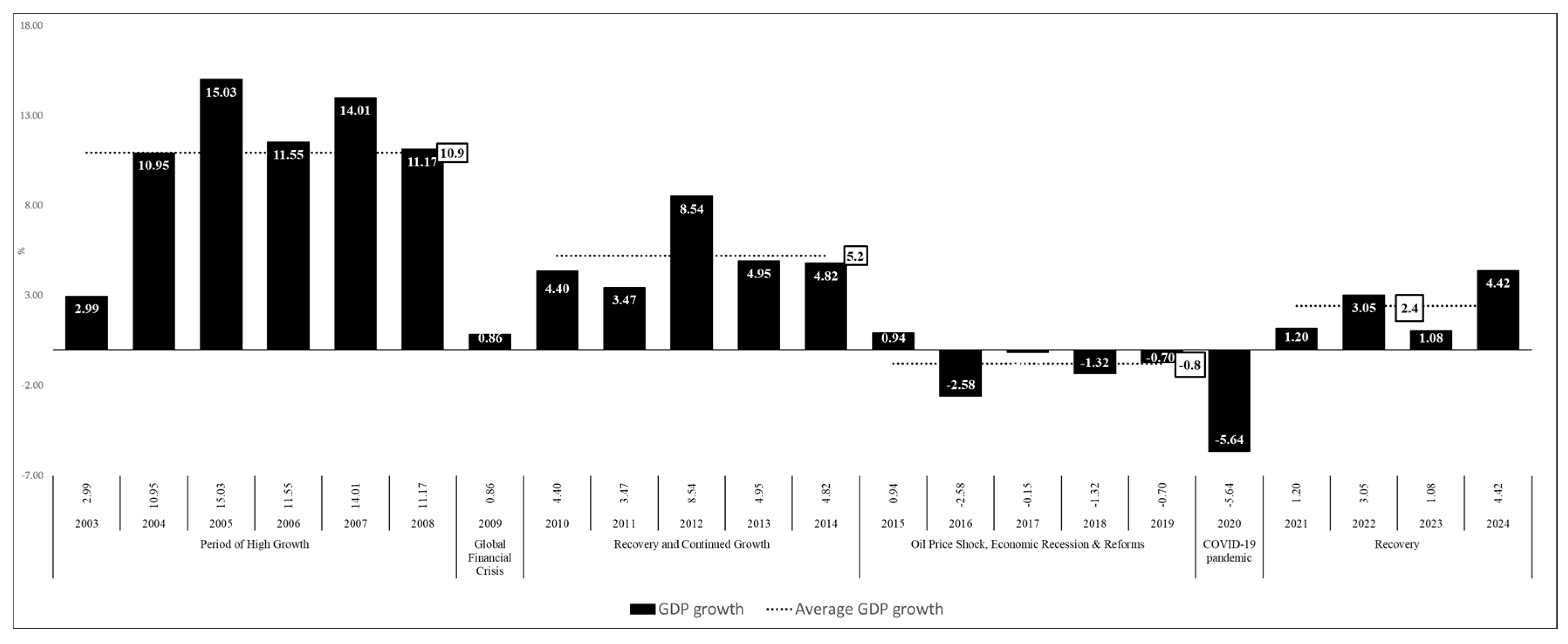

Since gaining independence in 1975, Angola’s economy has experienced significant transformations, marked by socialist policies, civil war (1975–2002), and economic instability. According to

Figure 1 below, post-war, from 2002 to 2014, Angola saw rapid oil-driven growth averaging 10 percent, enabling infrastructure development but deepening dependence on oil. The 2014 oil price collapse led to recession (2016–2020), currency depreciation, and inflation. Since 2018, reforms focusing on exchange rate liberalization, fiscal consolidation, and diversification have stabilized the economy, though structural challenges persist. The economy rebounded modestly in a post-recession, growing 4.4 percent in 2024, a fourth-year consecutive growth, averaging 2.4 percent, but oil remains central to Angola’s economy, accounting for about 29 percent of GDP, 59 percent of government revenues, and 94 percent of exports (INE, Ministry of Finance of Angola and BNA). Nevertheless, diversification efforts are yielding results, as agriculture is regaining its position as the primary driver of non-oil GDP, fueled by increased credit to the agricultural sector [

1,

2].

Inflation in Angola has historically been volatile due to war, economic transitions, and external shocks. The country faced hyperinflation in the 1990s, exceeding 4,000 percent, driven by excessive money printing and fiscal mismanagement. Post-war reforms and oil revenue stabilization helped reduce inflation, which fell from 430 percent in 2000 to around 12 percent in 2006. Monetary policy has played a crucial role in inflation control. The “hard kwanza” policy introduced in 2003, involving exchange rate stabilization and foreign financing of deficits, helped control inflation. From 2003, tighter monetary policy reduced inflation, but persistent money growth, remonetization, and reserve accumulation kept inflation dynamics unstable.

The 2014 oil crisis and exchange rate depreciation led to inflation exceeding 36 percent in 2016–2017.

Figure 2 shows Angola’s monthly inflation (month-on-month, MoM) trajectory from January 2015 to October 2024. Inflation peaked at 4.26 percent in July 2016, likely due to currency depreciation and economic instability. From 2017 to 2021, inflation remained volatile but relatively stable. A sharp decline occurred in early 2022, reaching 0.07 percent, possibly due to policy interventions. Inflation rebounded in 2023, peaking before settling at 1.70 percent in late 2024. The trend reflects inflationary pressures, economic adjustments, and policy impacts over time.

The relationship between money growth and inflation has been complex. Before 2015, Angola relied on foreign reserves to stabilize prices through exchange rate management. However, declining oil revenues forced a shift toward tighter monetary policies. Money supply fluctuations were notable, with growth peaking at 29 percent in 2021. Periods of excessive money growth, particularly in 2019 and 2020, may have contributed to inflation acceleration.

Angola’s fiscal policy has improved since 2000, with government expenditures declining from 60 percent of GDP in 2000 to 35 percent in 2008. However, spending increased post-2007, leading to a rising non-oil primary deficit. Inflation remains sensitive to global commodity prices, exchange rate movements, and fiscal discipline.

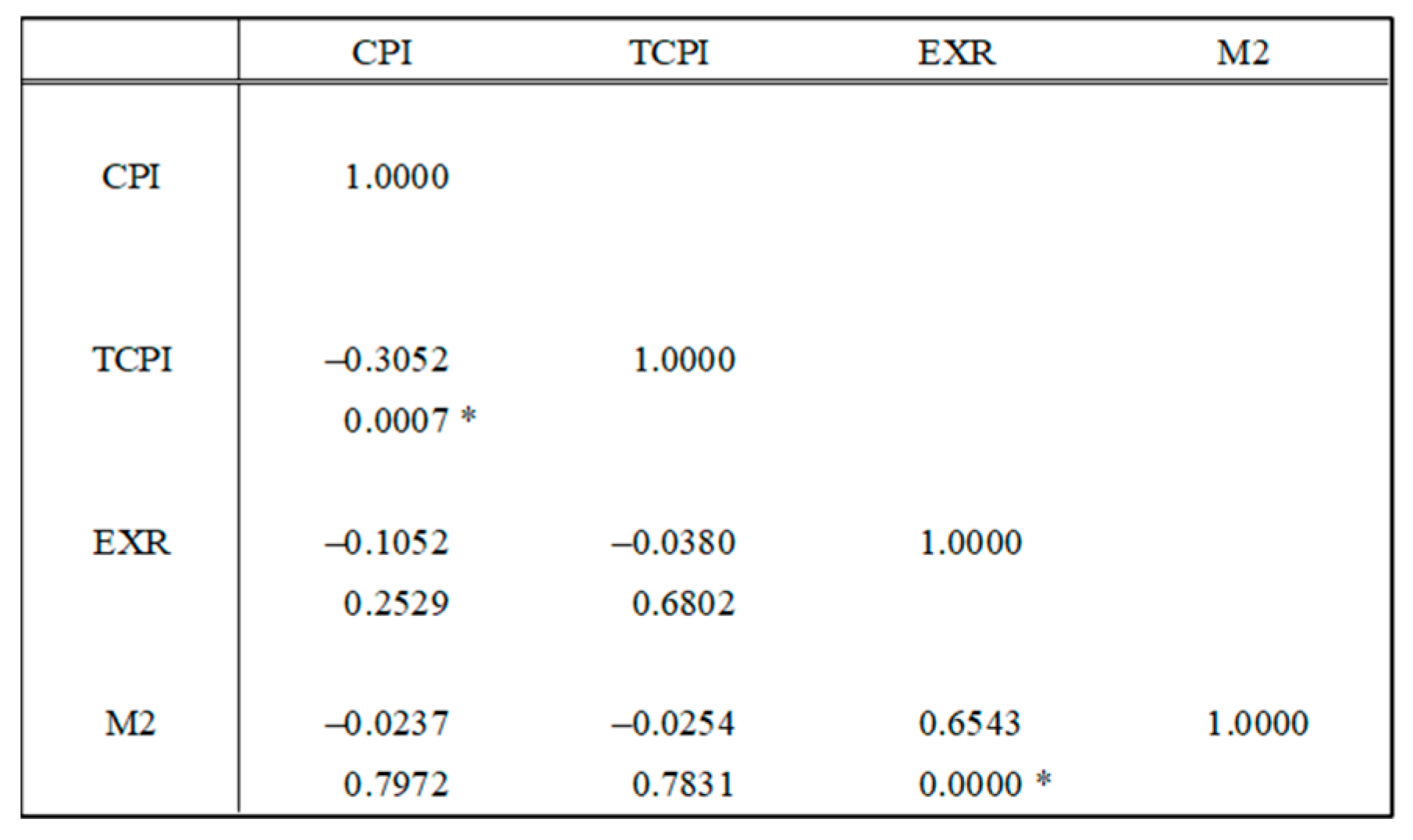

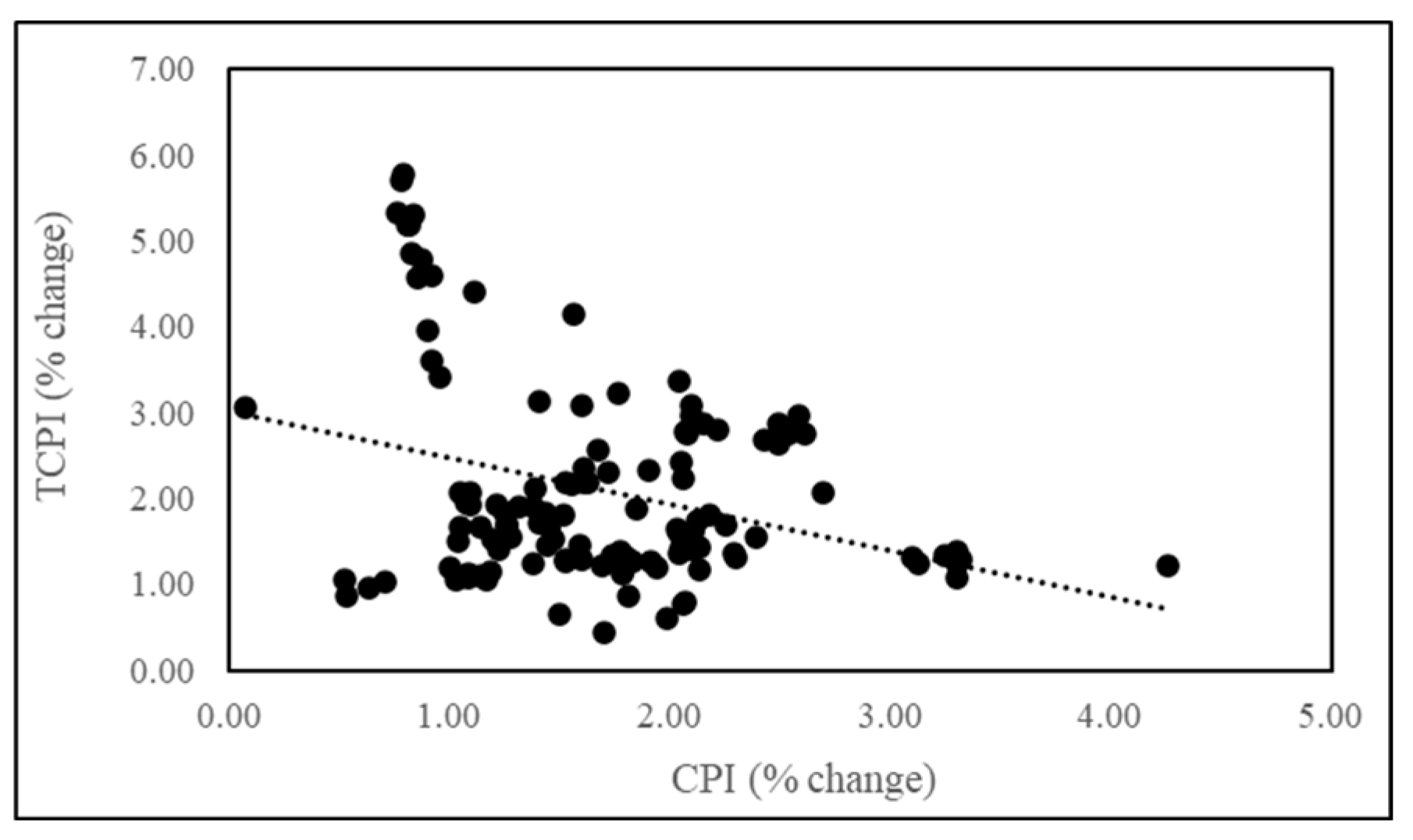

Looking at the variables considered for this study,

Figure 3 shows weak correlations between CPI and M2 (–0.0237) and EXR (–0.1052), while TCPI has a significant negative correlation (–0.3052, p = 0.0007).

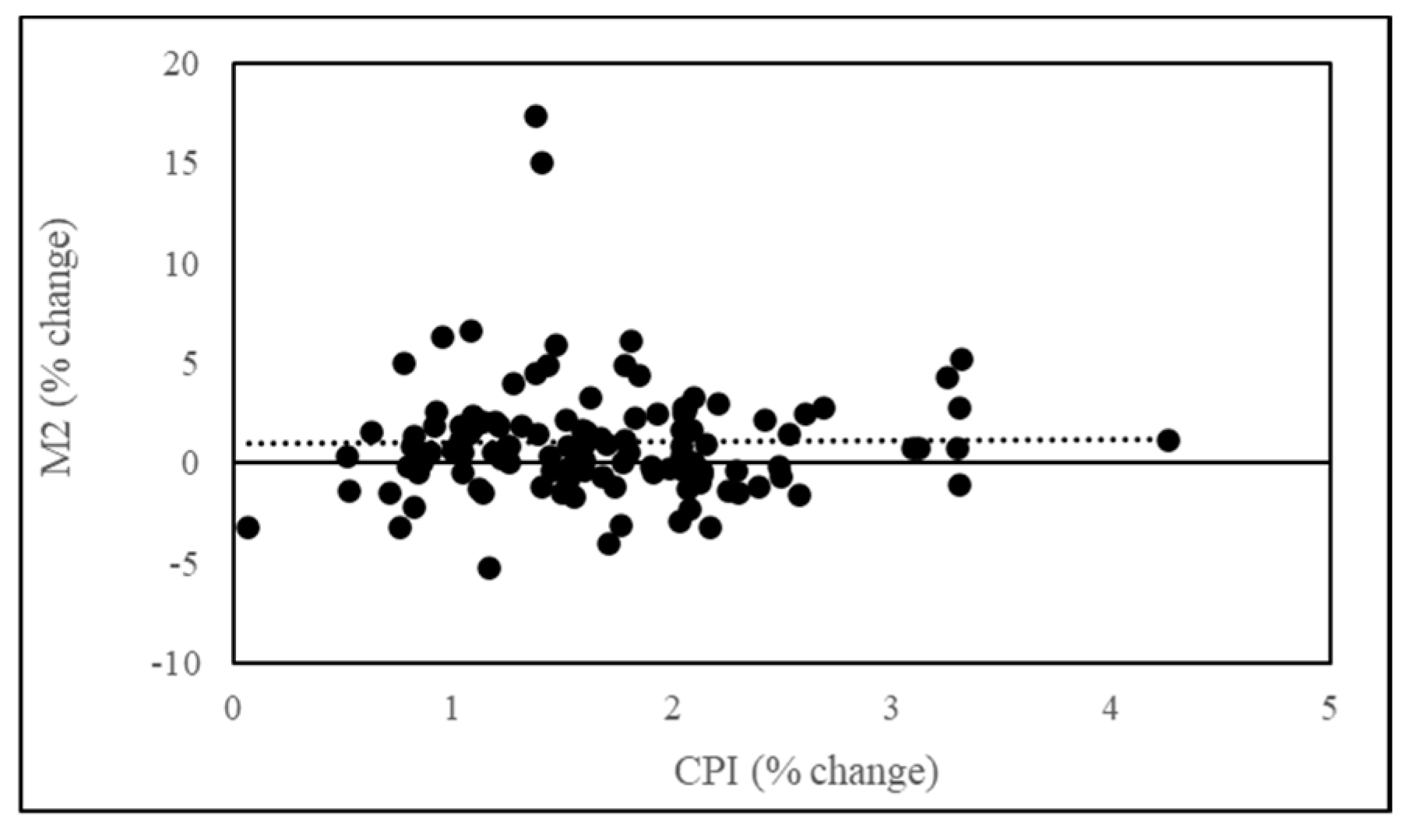

Figure 4 confirms no strong relationship between inflation and M2.

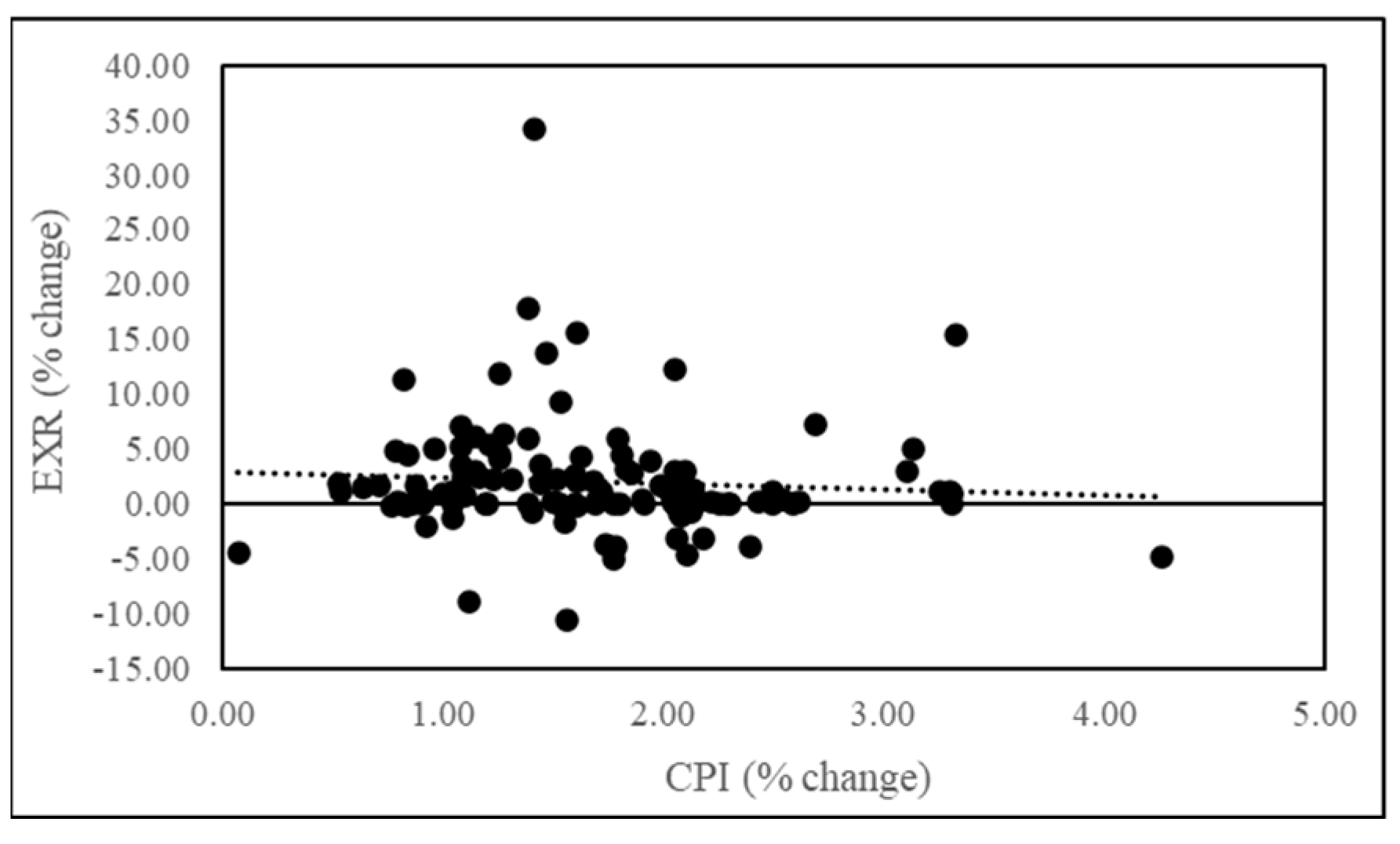

Figure 5 shows a weak link between CPI and EXR.

Figure 6 highlights a negative trend between inflation and TCPI. These weak linear associations suggest further analysis using an econometric model to capture lagged effects.

Hence, this study proposes to quantify the impact of the determinants of inflation in Angola and to propose what policy measures might help ensure stable prices in Angola.

1.1. Research Questions

This research seeks to answer the following research questions:

- (i)

Which independent variables contribute the most to inflation in Angola?

- (ii)

What policy recommendations are necessary to help mitigate the impact of independent variables on inflation in Angola?

1.2. Research Objectives

This research primarily aims to analyze and measure the relationship between inflation and identified determinants in Angola. Using an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model and subsequent diagnostic tests, the study evaluates the significance of these factors in influencing inflation over both short- and long-term horizons, while also identifying the direction of causality. Understanding the bidirectional link between inflation and selected variables is essential for formulating effective monetary policy in Angola. Furthermore, this study seeks to explore similar findings and policy recommendations from international experiences through an in-depth literature review.

1.3. Hypothesis

The null and alternative hypotheses will be examined in line with this study’s objectives to assess whether the identified variables influenced inflation between 2015 and 2024:

The hypotheses will be evaluated at a 5 percent significance level for both short- and long-term relationships. If the probability associated with the t-value is greater than the significance level, the null hypothesis will be retained. However, if the probability of the t-value is less than the significance level, the null hypothesis will be rejected.

1.4. Significance of the Research

The uniqueness of this study lies in the fact that no previous research has examined the determinants of inflation in Angola for the period 2015–2024, nor has imported inflation been considered as a contributing factor. The findings can aid Angolan policymakers in formulating more effective macroeconomic policies and implementing measures to stabilize prices, benefiting both the economy and society.

4. Data, Estimation Results and Discussion

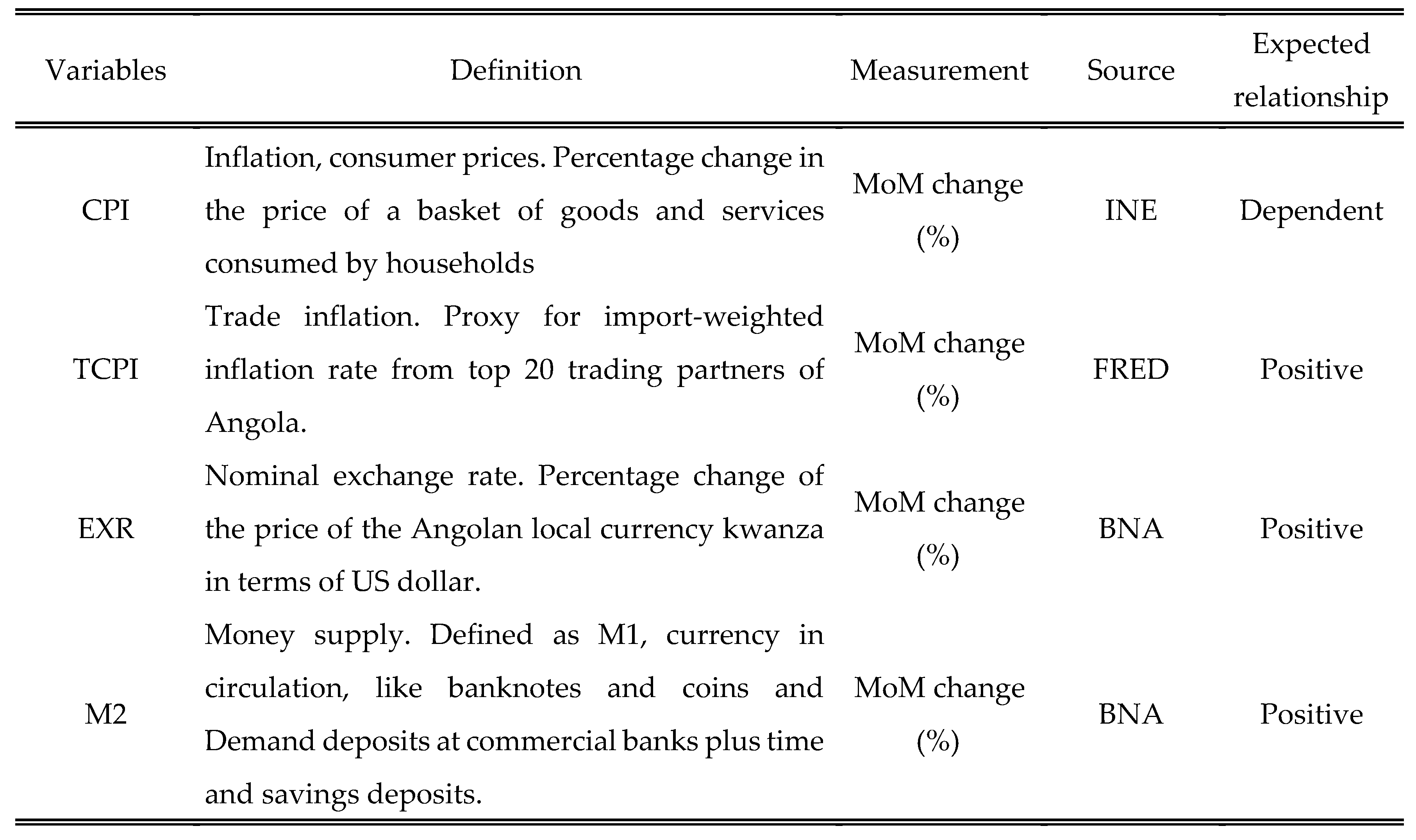

Figure 8 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables involved, each with 120 observations. CPI and TCPI show moderate variability, with TCPI having a higher mean and standard deviation, indicating greater dispersion. EXR exhibits the highest variability, with a wide range (26.67) and significant standard deviation (5.18), suggesting volatile fluctuations. M2 also shows considerable variability but less extreme than EXR. Median values are lower than means for all variables, indicating right-skewed distributions. Overall, EXR appears the most volatile, while CPI is the most stable.

4.1. Optimal Lag Selection

Based on the information criterion results, the AIC was determined to be the most suitable, as it had the lowest value. The findings indicate that the optimal lag selection for each variable in the ARDL model is 1, 4, 2, and 0 for CPI, TCPI, EXR, and M2, respectively.

The equation would take the following shape:

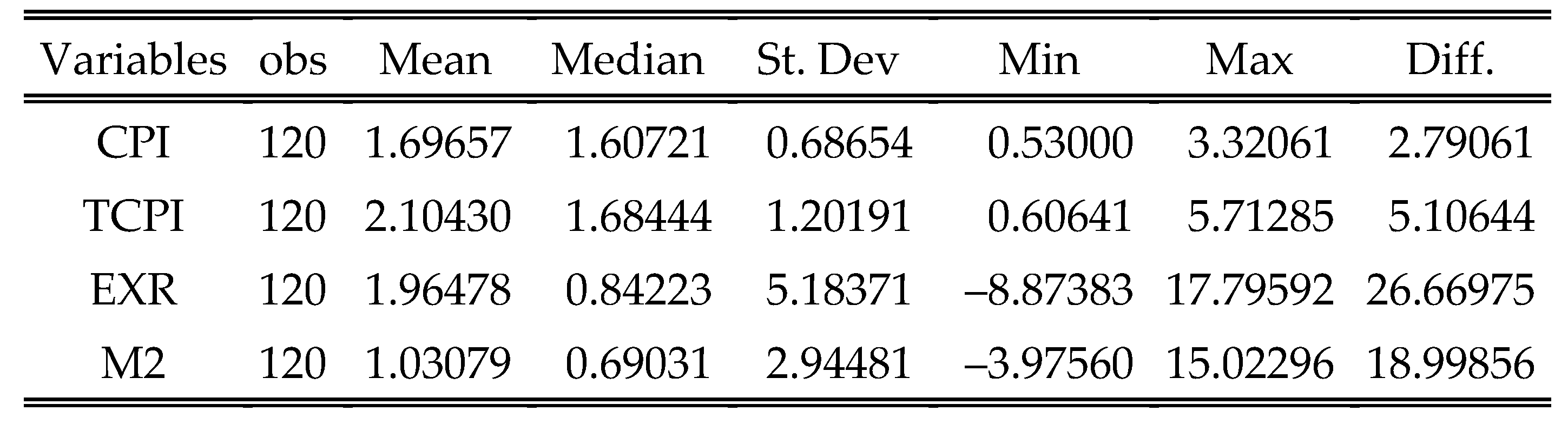

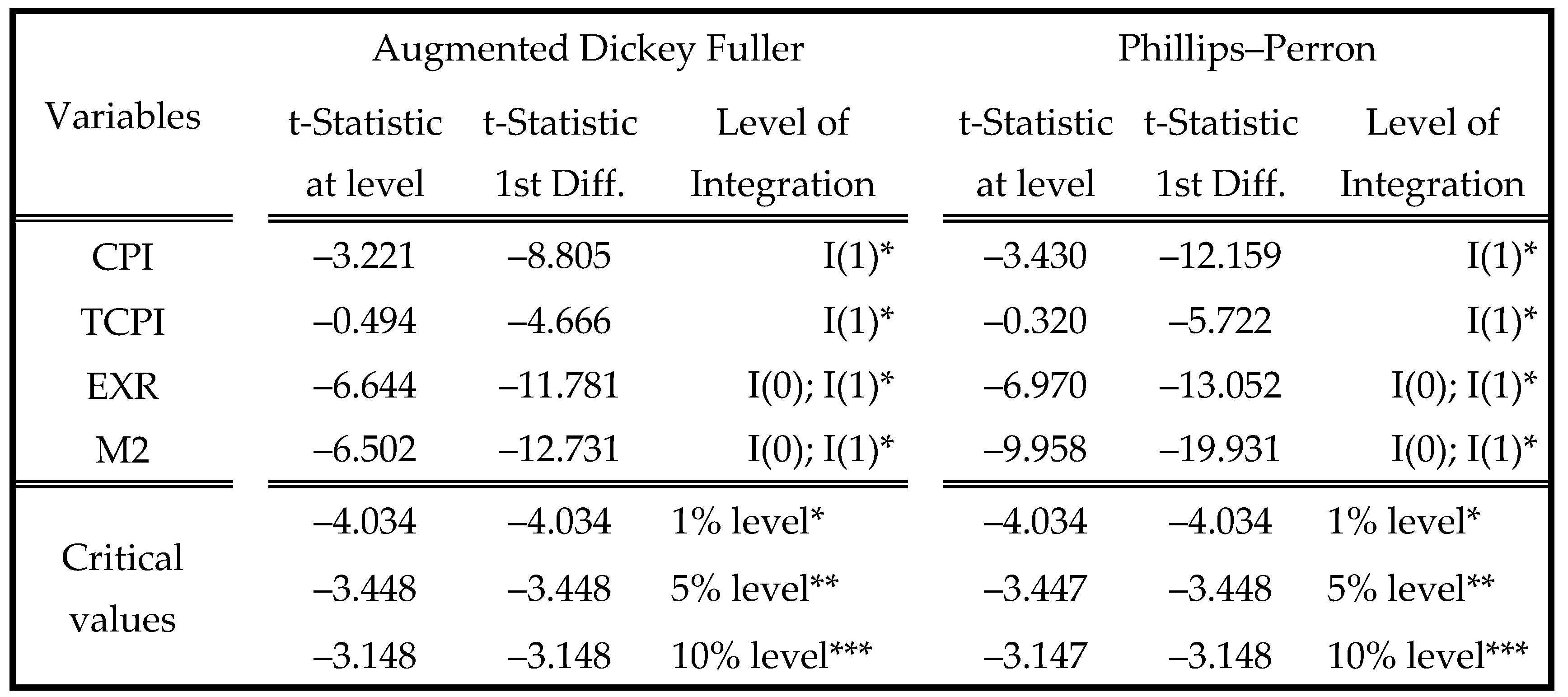

4.2. Unit Root Tests

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 present the ADF and PP unit root tests, assessing stationarity with and without trend. Results indicate mixed integration orders, with CPI, EXR, and M2 exhibiting I(0) and I(1) properties, while TCPI is strictly I(1). These findings justify ARDL modeling, accommodating both I(0) and I(1) variables.

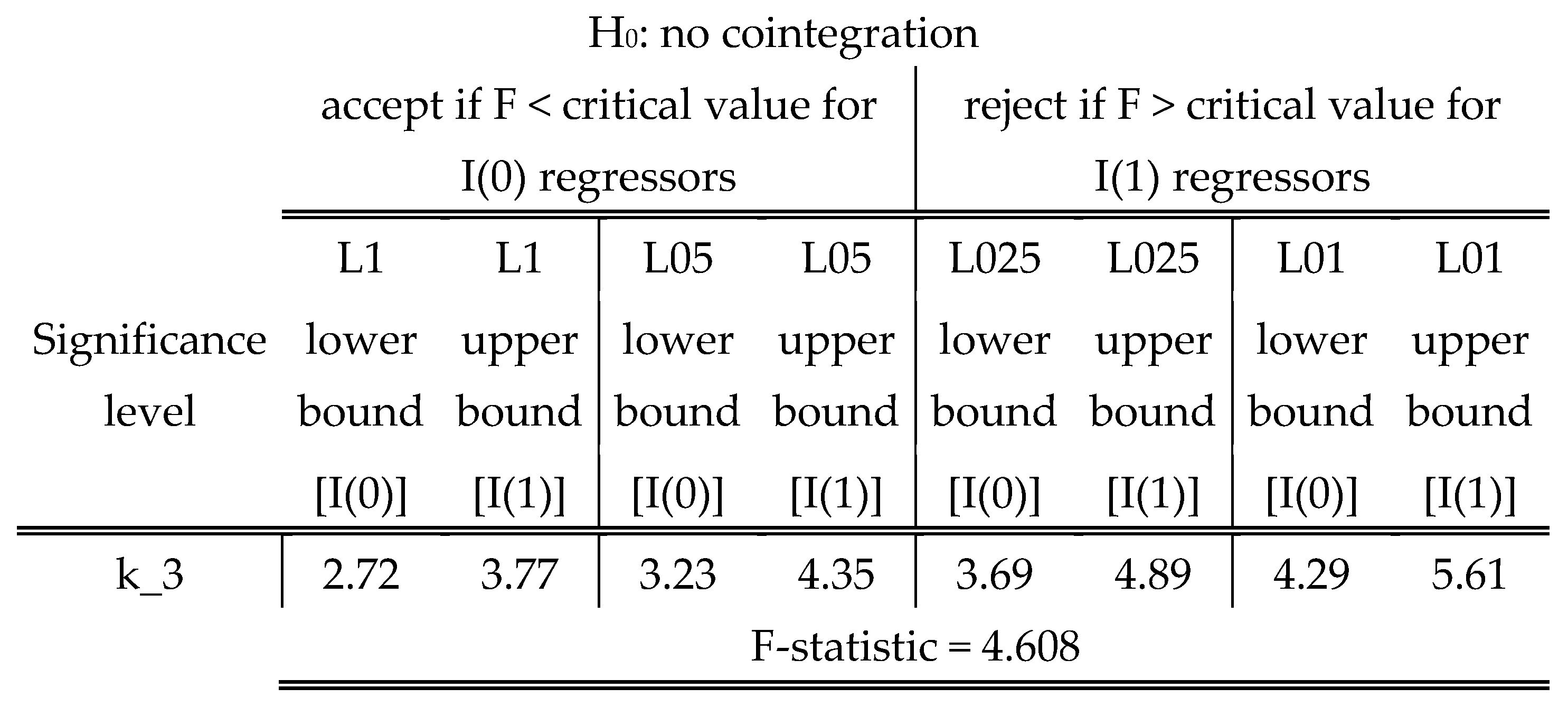

4.3. ARDL Bound Tests Results for Cointegration

As seen above, the series were integrated in different orders, that is, with a combination of I(0) and I(1) series; hence, the ARDL bounds test was applied to the level of the variables to determine whether the variables had a long-term cointegration.

Figure 11 shows the ARDL bounds testing results. With an F-statistic of 4.608, the result exceeds the upper bound at the 5 percent significance level (4.35). This suggests strong evidence of cointegration, implying a long-run relationship among the variables at conventional significance levels, hence the null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected. The ARDL model is retained.

4.4. ARDL Model Estimation Results

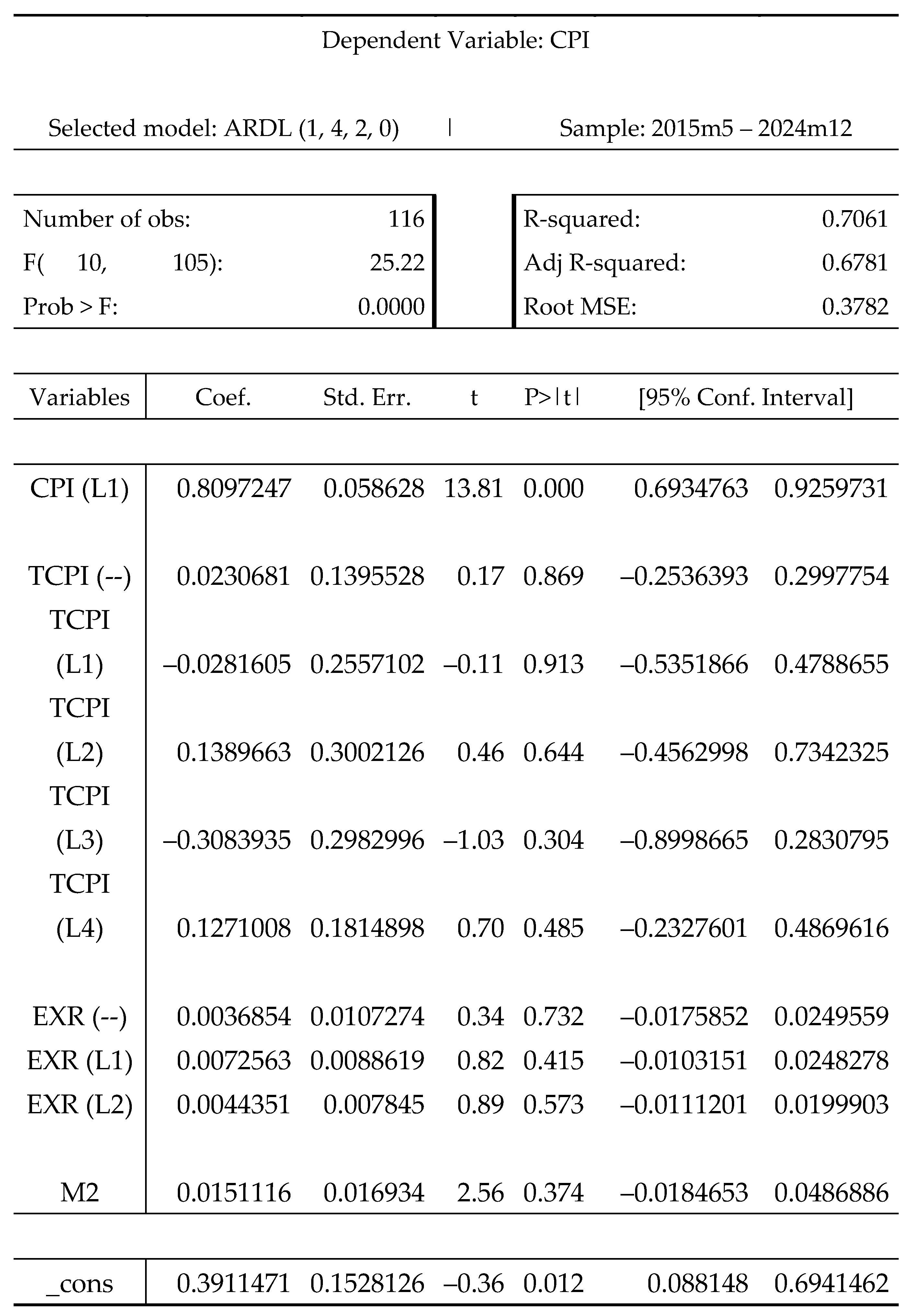

The variables CPI, TCPI, EXR, and M2 exhibit cointegration, indicating the presence of a long-term equilibrium relationship. Consequently, both the long-term and short-term models were estimated to analyze their dynamics.

4.4.1. Long-Term Relationship

With the existence of a long-term relationship between variables, the model could quantify the effect of independent variables on the dependent variables, measuring the effect of the explanatory variables on the explained variable, as shown in

Figure 12 below.

The long-run estimation results indicate that CPI is highly persistent, with its lagged value (CPI L1) significantly influencing current inflation (p < 0.01). On the other hand, TCPI and EXR coefficients, including their lags, are statistically insignificant, suggesting no strong long-run impact on CPI. M2 also lacks statistical significance, implying a weak monetary influence. The model’s R-squared (0.7061) suggests a good fit, but some explanatory variables contribute minimally. The insignificant constant indicates no strong autonomous inflationary pressures independent of included factors.

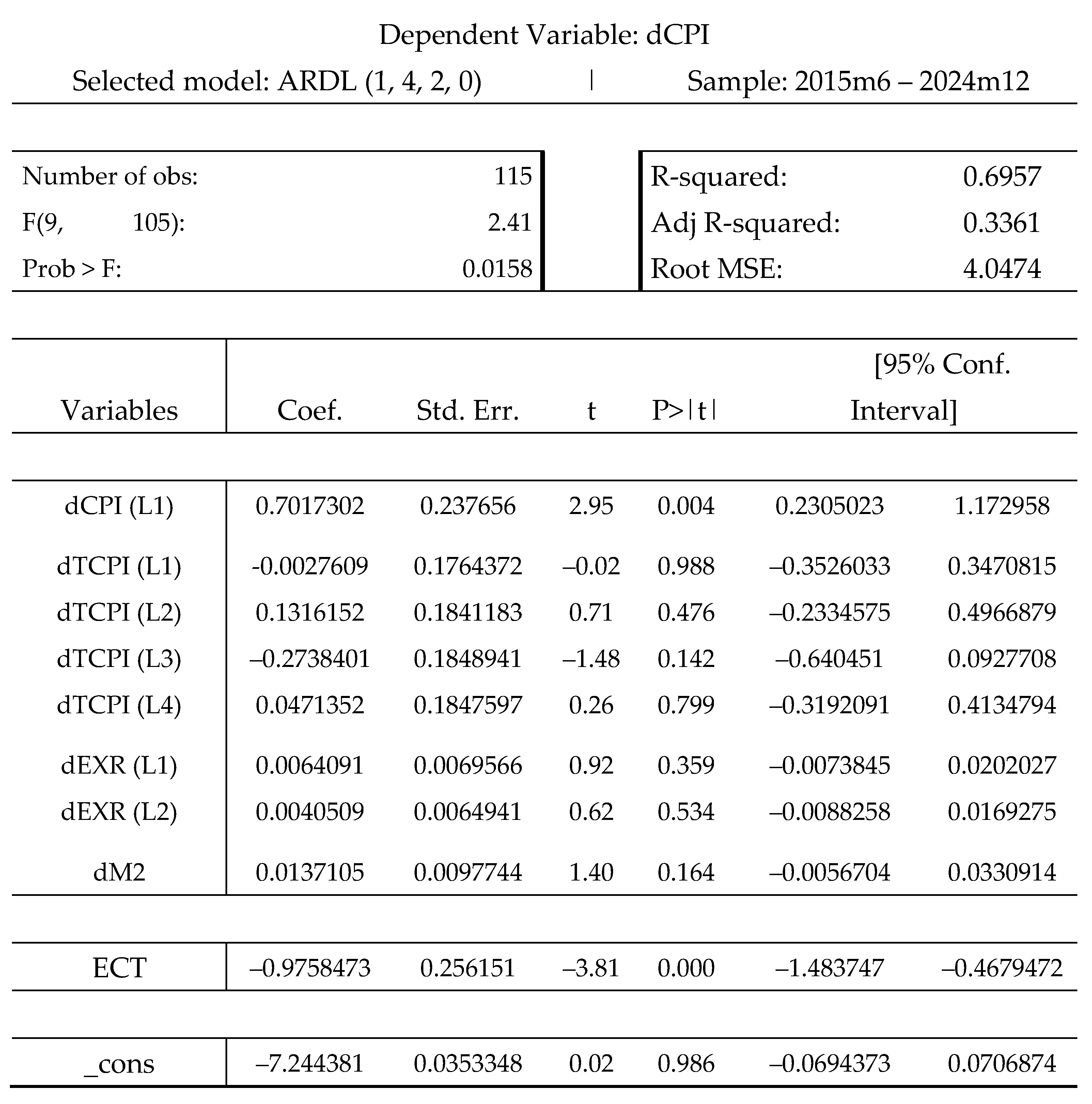

4.4.2. Short-Term Relationship

Despite confirming a long-term relationship, the ARDL model highlights the importance of short-term dynamics for immediate insights, predictive power, policy guidance, model accuracy, and economic theory alignment in econometric and time series analysis.

According to short-run regression results in

Figure 13, the ARDL (1, 4, 2, 0) model indicates that past inflation significantly influences current inflation (lagged CPI coefficient: 0.702, p = 0.004), suggesting strong inflation persistence. This suggests inflation perception may drive inflation, as businesses and consumers adjust prices and wages based on past trends, reinforcing inflationary pressures. The error correction term (ECT) is –0.976 (p = 0.000), implying that deviations from long-run equilibrium adjust rapidly, with approximately 98 percent correction per period. External price movements (dTCPI) and exchange rate changes (dEXR) are statistically insignificant, indicating a minimal short-run impact on domestic inflation. Money supply changes (dM2) also lack immediate effect. The model is statistically significant (p = 0.0158) but explains only 34 percent of inflation variability (Adj. R-squared = 0.3361), suggesting other unaccounted factors influence inflation dynamics.

4.5. Results of the Diagnostic Tests

Using the approach described in chapter 3, diagnostic tests were conducted to assess (i) normality, (ii) autocorrelation, (iii) heteroscedasticity, and (iv) model stability.

4.5.1. Normality Tests

Figure 14 presents the normality test for residuals. The Jarque-Bera statistic (48.038) and the high kurtosis (10.31) indicate significant deviation from normality. The skewness (1.03) suggests asymmetry, with a rightward tilt. The histogram confirms non-normal distribution, implying potential misspecification or the need for transformation in the model.

4.5.2. Multicollinearity Test

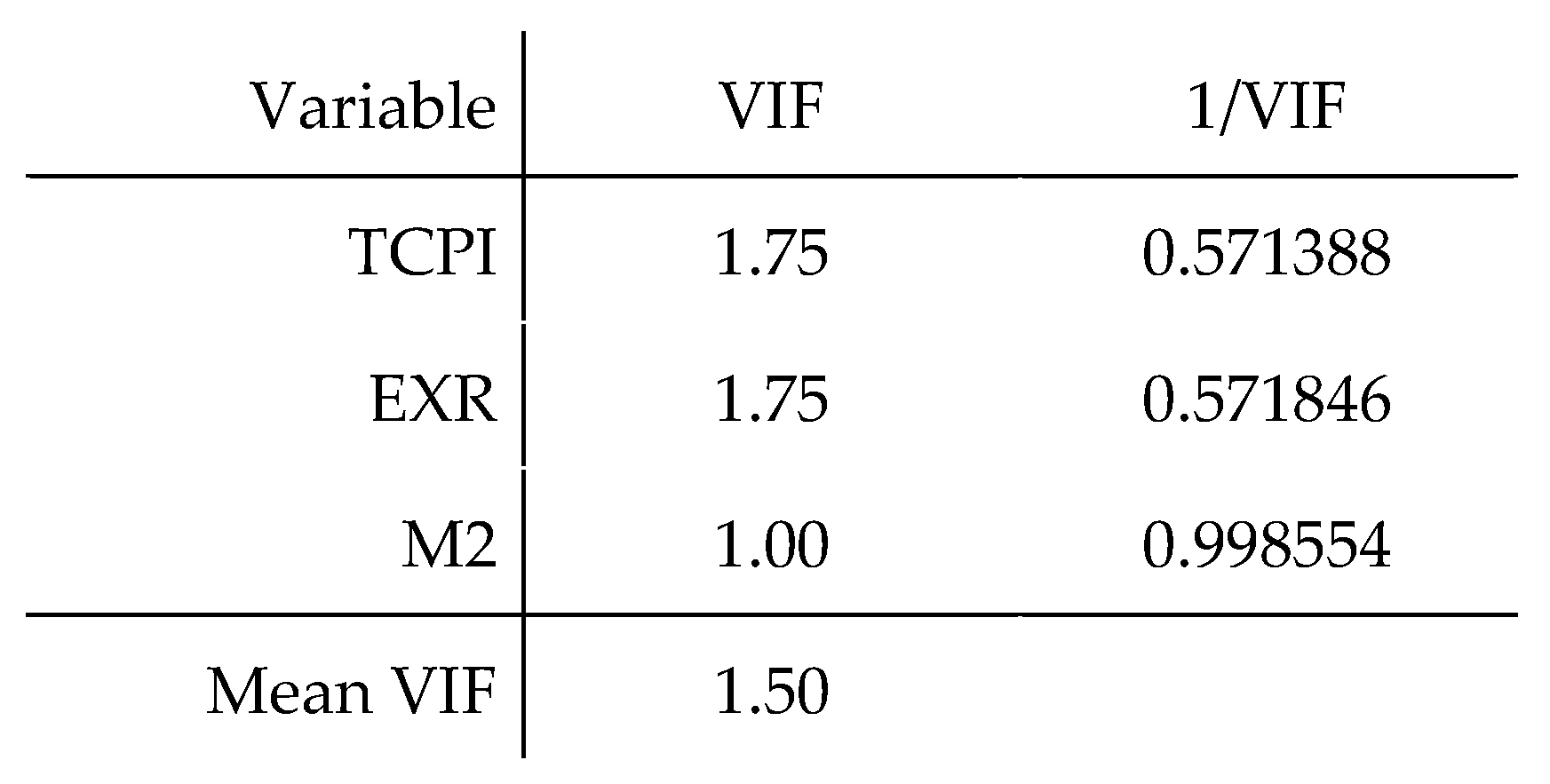

Figure 15 presents the variance inflation factor (VIF) results, assessing multicollinearity among explanatory variables. The VIF values for TCPI (1.75), EXR (1.75), and M2 (1.00) are all below the conventional threshold of 10, indicating no severe multicollinearity. The mean VIF (1.50) further confirms that independent variables are not highly correlated, ensuring reliable coefficient estimates in the ARDL model. No corrective measures, such as variable exclusion or transformation, are required.

4.5.3. Autocorrelation Test

Figure 16 presents the Breusch-Godfrey test for autocorrelation to check for serial correlation in the residuals. The chi-square statistic (0.962) with 1 degree of freedom yields a p-value of 0.3266, which is above the conventional 5 percent significance level. This means that the model does not suffer from autocorrelation issues, which is desirable for ensuring unbiased and efficient estimates.

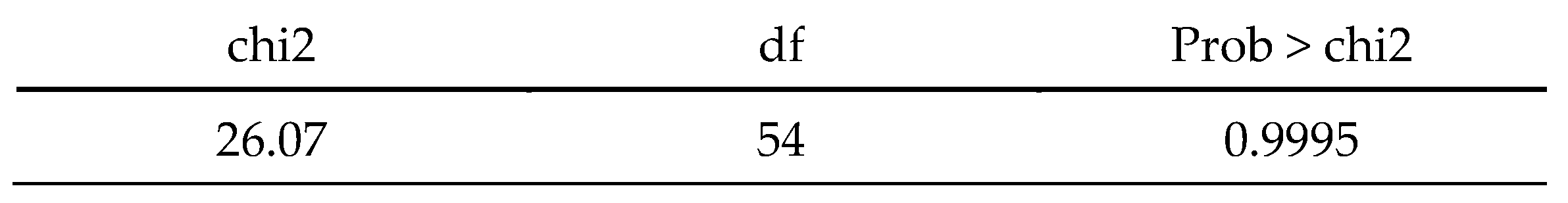

4.5.4. Heteroscedasticity Test

Figure 17 below shows the heteroscedasticity test results. Since the

p-value of 0.9995 is greater than the 0.05 significance level, the null hypothesis was not rejected. Hence, it confirms homoscedasticity.

4.5.5. Stability Tests

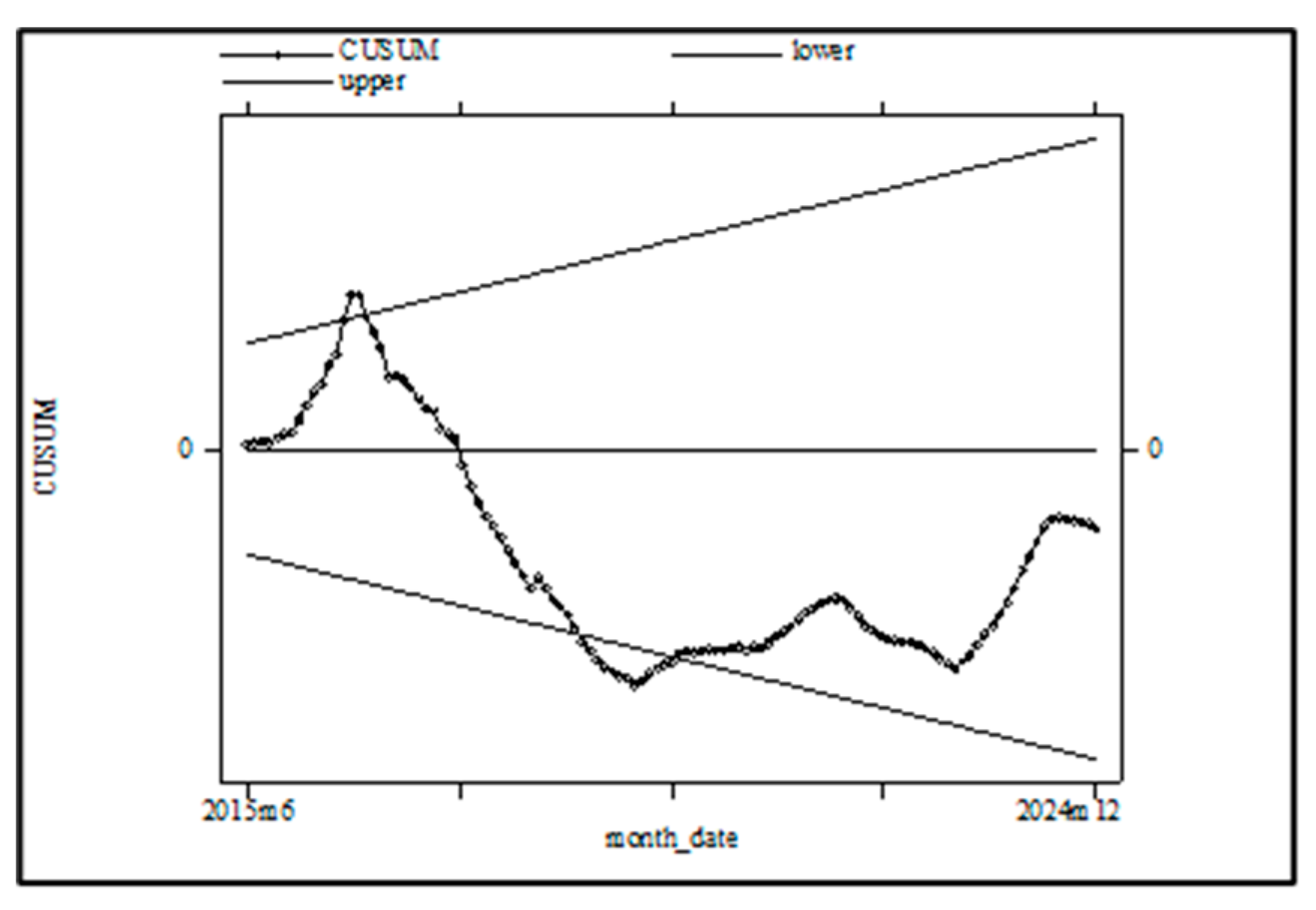

The CUSUM test (

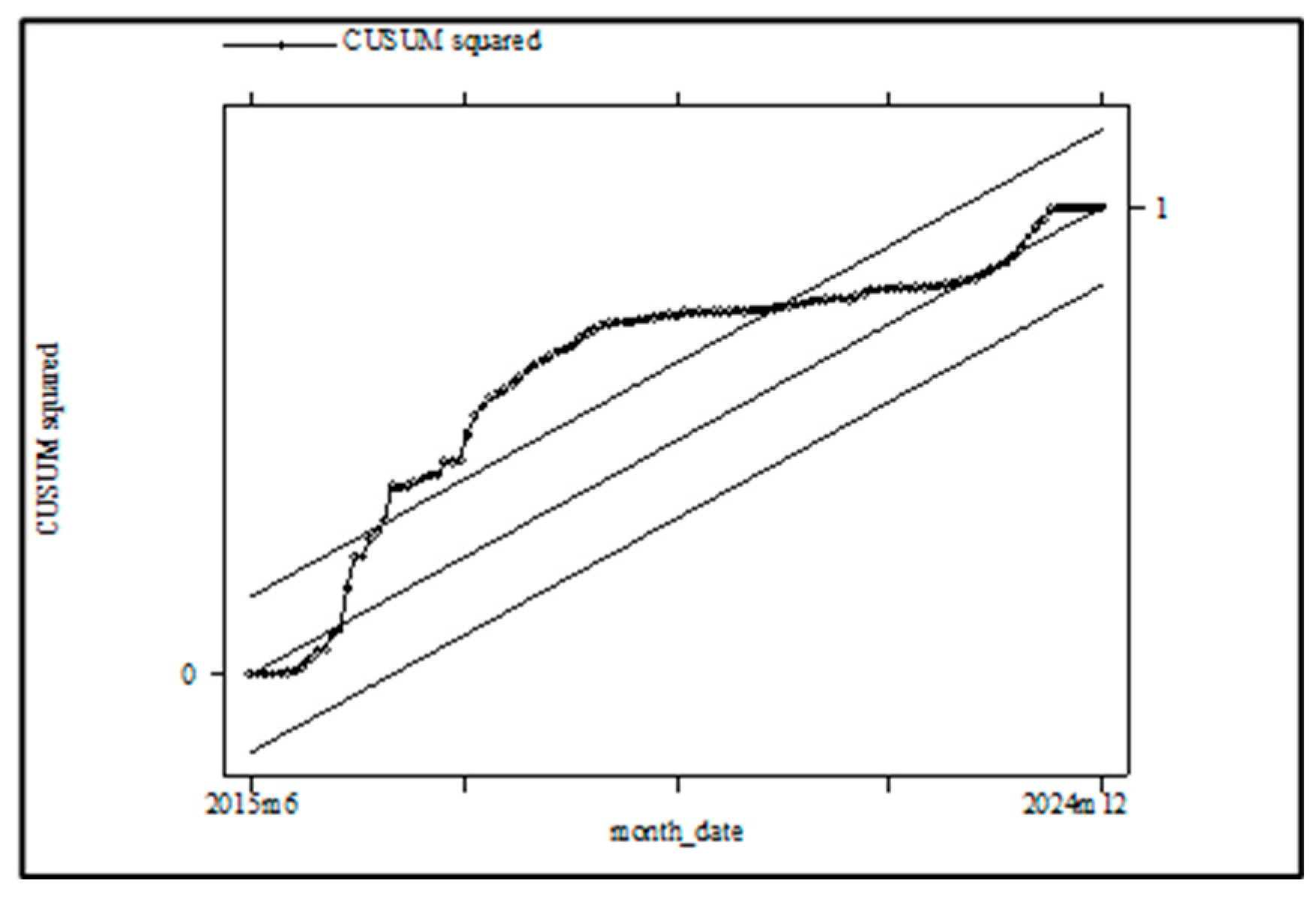

Figure 18) shows that the model’s residuals remain within the upper and lower bounds at a 5 percent significance level, suggesting no structural instability. However, the CUSUMSQ test (

Figure 19) indicates possible instability, as the cumulative sum of squared residuals approaches the boundaries. This suggests potential variance instability in the model over time, warranting further examination. While the model appears largely stable, some variations in the long-run variance may require adjustments or robust checks to ensure reliable inference.

4.6. Causality Analysis Results

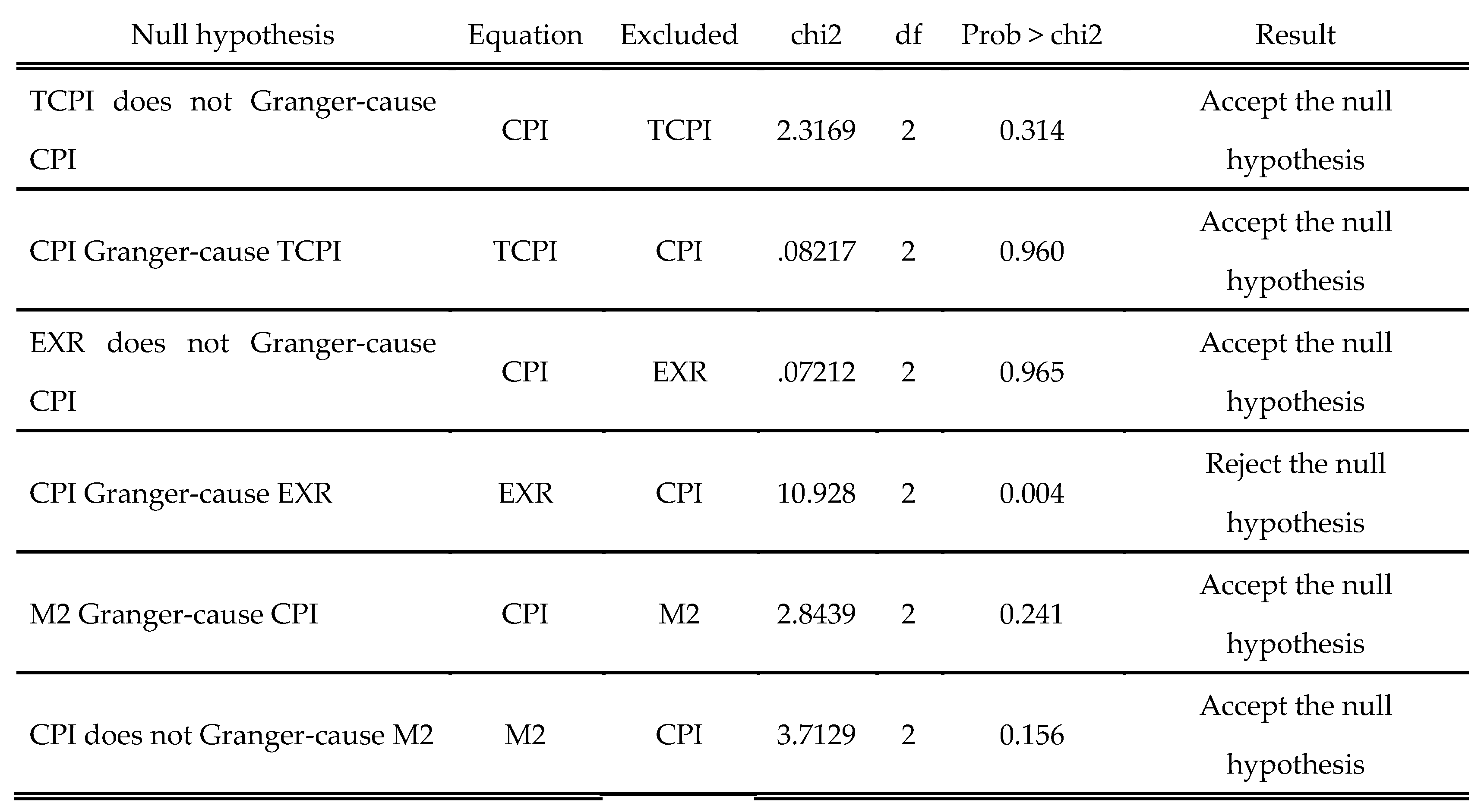

The Granger causality test results in

Figure 20 below indicate that CPI Granger-causes EXR at a 1 percent significance level, while no bidirectional causality exists between CPI, TCPI, EXR, and M2. Other relationships fail to reject the null hypothesis.

4.7. Discussion

The ARDL model offers new insights into Angola’s inflation dynamics, reinforcing and extending prior research. Strong inflation persistence suggests inflation perception may be a key driver, as businesses and consumers adjust prices and wages based on past trends, supporting classical monetarist views. However, unlike traditional theories emphasizing money supply and fiscal deficits, the study findings indicate these factors (M2, TCPI) have limited short-run impact. Instead, exchange rate fluctuations play a crucial role, aligning with Ferreira (2006) and IMF reports, which highlight external shocks and currency depreciation as major determinants of domestic price movements.

Additionally, the weak statistical impact of fiscal measures echoes structuralist perspectives that stress the importance of underlying economic constraints, such as overdependence on oil revenues and insufficient domestic production. The discussion also emphasizes the role of monetary and fiscal policies in stabilizing inflation, suggesting that effective policy coordination is crucial for macroeconomic stability. Structural constraints, including weak domestic production capacity and limited financial inclusion, may exacerbate inflationary pressures. Furthermore, the findings are examined in the context of broader economic challenges, such as exchange rate pass-through effects and external debt sustainability. Thus, in contrast to the demand-pull and cost-push theories from Keynesian literature, the interplay between external variables and structural factors appears to dominate.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary Conclusions

The study on the drivers of inflation in Angola examines key macroeconomic variables influencing price levels. Using econometric techniques, it identifies exchange rate fluctuations, money supply growth, and external shocks as primary drivers of inflation. The findings highlight the significant role of exchange rate pass-through, given Angola’s reliance on imports and oil revenues. The study also reveals that monetary policy alone may be insufficient to control inflation without complementary fiscal measures. Structural weaknesses, such as limited domestic production and financial market inefficiencies, exacerbate inflationary pressures.

An optimal lag was selected, based on the AIC criterion, resulted in lags of 1 for CPI, 4 for TCPI, 2 for EXR, and 0 for M2, establishing the ARDL model structure. The ADF and PP unit root tests indicated mixed orders of integration among the variables, justifying the use of the ARDL methodology. Furthermore, the ARDL bounds test, where the F-statistic exceeds the critical value, confirmed cointegration and a stable long-term relationship. The long-term estimates reveal strong inflation persistence through significant lagged CPI effects, while short-term dynamics indicate that past inflation significantly influences current inflation, with a rapid error correction term adjusting nearly 98 percent of disequilibrium per period.

Subsequently, diagnostic tests affirmed normality, absence of multicollinearity, and no serial correlation, though the CUSUMSQ test hints at potential variance instability. Finally, in the Granger causality test it was revealed that CPI Granger-causes EXR, and the overall discussion in sub-chapter 4.7 emphasizes the need for coordinated policy actions to achieve price stability. Strengthening monetary policy transmission, improving foreign exchange management, and diversifying the economy are essential strategies to mitigate inflation risks. The study suggests enhancing domestic production capacity to reduce import dependency and implementing measures to stabilize the exchange rate. Fiscal discipline and improved public debt management are also critical for long-term stability. Overall, the research contributes to understanding inflation dynamics in resource-dependent economies, offering insights for policymakers.

On the other hand, the prevalence of a large informal economy in Angola (more than 80 percent of the population) could significantly impact the study’s findings. Since many transactions in the informal sector are not captured by official statistics, key variables such as money supply (M2) and the consumer price index (CPI) might be undermeasured. This under-reporting can lead to measurement error, thereby weakening the estimated relationships in the ARDL model. For example, if a substantial portion of economic activity occurs outside formal channels, the official monetary aggregates may not fully reflect the actual liquidity available, potentially biasing the estimated impact of money supply on inflation.

Moreover, the informal sector often operates with different pricing mechanisms and may experience more volatile price adjustments compared to the formal sector. As a result, the official CPI may not capture the full extent of price fluctuations, leading to a divergence between measured inflation and the inflation experienced by the public. This divergence could intensify inflation perception among consumers, which, in turn, may influence wage-setting behavior and demand for policy intervention. In summary, an extensive informal economy can compromise the robustness of the model’s variables and create a gap between official inflation measures and public inflation perceptions, thereby complicating policy design and effectiveness.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

To stabilize prices and support sustainable growth, Angola’s policymakers should strengthen monetary policy transmission to ensure effective interest rate adjustments, improve foreign exchange management to mitigate inflation from exchange rate fluctuations, and promote economic diversification and domestic production to reduce dependence on oil and imports. Furthermore, fiscal discipline should be enhanced through better debt management and deficit reduction, implement targeted interventions to stabilize food prices and support food security, and formalize the informal economy by improving data accuracy, incentivizing formalization, and tailoring policies to its unique dynamics, bridging gaps between official inflation measures and public perceptions for better policymaking.

5.3. Accomplishment of Research Objectives

The study used an ARDL model, diagnostic tests, and causality analysis to assess inflation determinants in Angola, international findings to refine policy recommendations for effective monetary management and long-term price stability.

5.4. Limitations of the Research

Due to limited high-frequency data, the study did not assess the impact of inflation perception, potential GDP, and the informal sector on inflation, which may influence overall price dynamics in Angola.

Figure 1.

GDP performance. Source: Author’s calculations in MS Excel using data series.

Figure 1.

GDP performance. Source: Author’s calculations in MS Excel using data series.

Figure 2.

Monthly inflation (MoM) trajectory in Angola. Source: Author’s calculations in MS Excel using data series.

Figure 2.

Monthly inflation (MoM) trajectory in Angola. Source: Author’s calculations in MS Excel using data series.

Figure 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients. Source: Author’s calculations in MS Excel using data series.

Figure 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients. Source: Author’s calculations in MS Excel using data series.

Figure 4.

Relationship between inflation and M2. Source: Author’s calculations in MS Excel using data series.

Figure 4.

Relationship between inflation and M2. Source: Author’s calculations in MS Excel using data series.

Figure 5.

Relationship between inflation and EXR. Source: Author’s calculations in MS Excel using data series.

Figure 5.

Relationship between inflation and EXR. Source: Author’s calculations in MS Excel using data series.

Figure 6.

Relationship between inflation and TCPI. Source: Author’s calculations in MS Excel using data series.

Figure 6.

Relationship between inflation and TCPI. Source: Author’s calculations in MS Excel using data series.

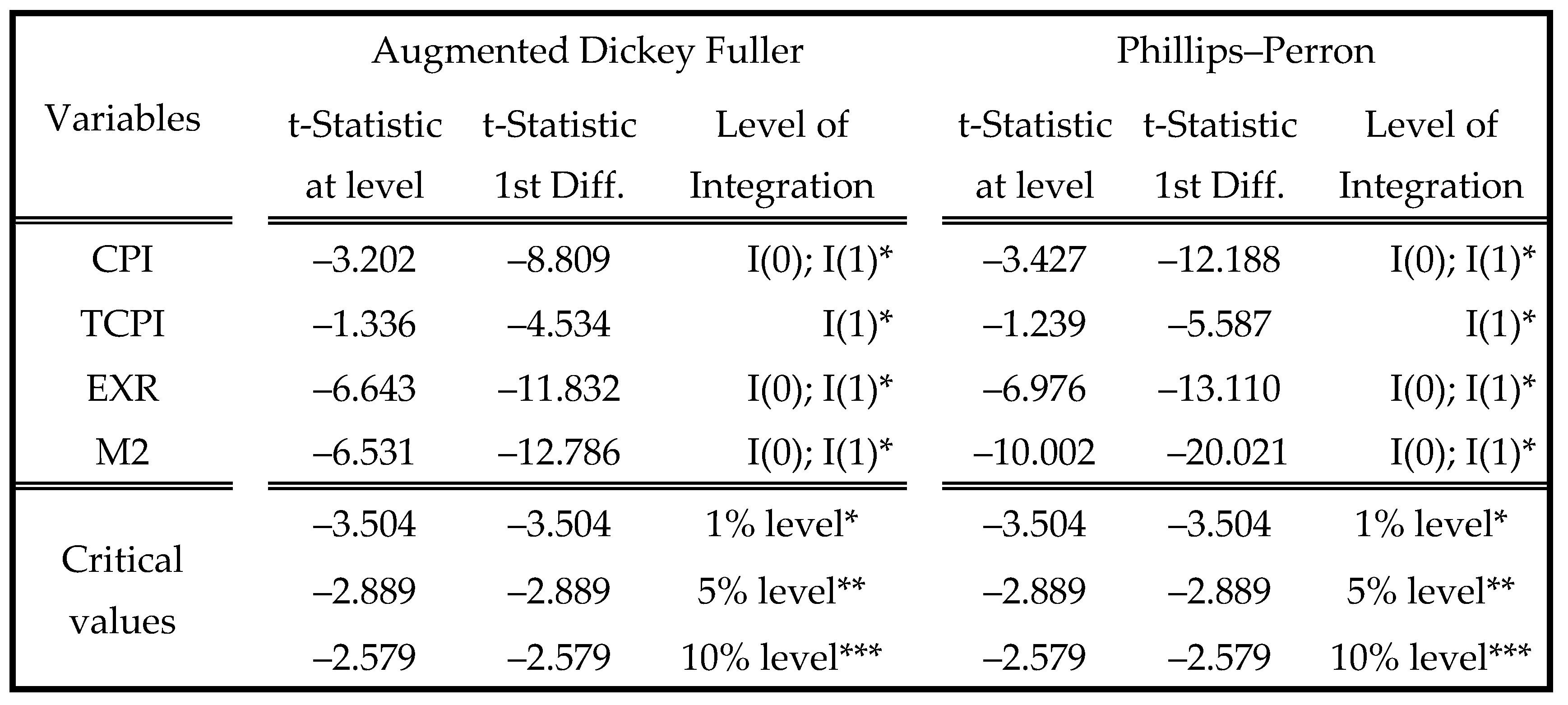

Figure 7.

Summary of dependent and independent variables used in the study.

Figure 7.

Summary of dependent and independent variables used in the study.

Figure 8.

Descriptive statistics results. Source: Authors’ computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 8.

Descriptive statistics results. Source: Authors’ computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 9.

ADF and PP unit root tests with intercept. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 9.

ADF and PP unit root tests with intercept. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 10.

ADF and PP unit root tests with intercept and trend. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 10.

ADF and PP unit root tests with intercept and trend. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 11.

ARDL bounds testing. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 11.

ARDL bounds testing. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 12.

Long run estimation results. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 12.

Long run estimation results. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 13.

Short run dynamics and error correction model results. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 13.

Short run dynamics and error correction model results. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 14.

Normality test. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 14.

Normality test. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 15.

VIF results. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 15.

VIF results. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 16.

Breusch-Godfrey test for autocorrelation. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 16.

Breusch-Godfrey test for autocorrelation. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 17.

White’s test for heteroscedasticity. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 17.

White’s test for heteroscedasticity. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 18.

CUSUM test results.

Figure 18.

CUSUM test results.

Figure 19.

CUSUM of Squares test results. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 19.

CUSUM of Squares test results. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 20.

Granger Causality Test. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.

Figure 20.

Granger Causality Test. Source: Author’s computation using STATA 14.2.