Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

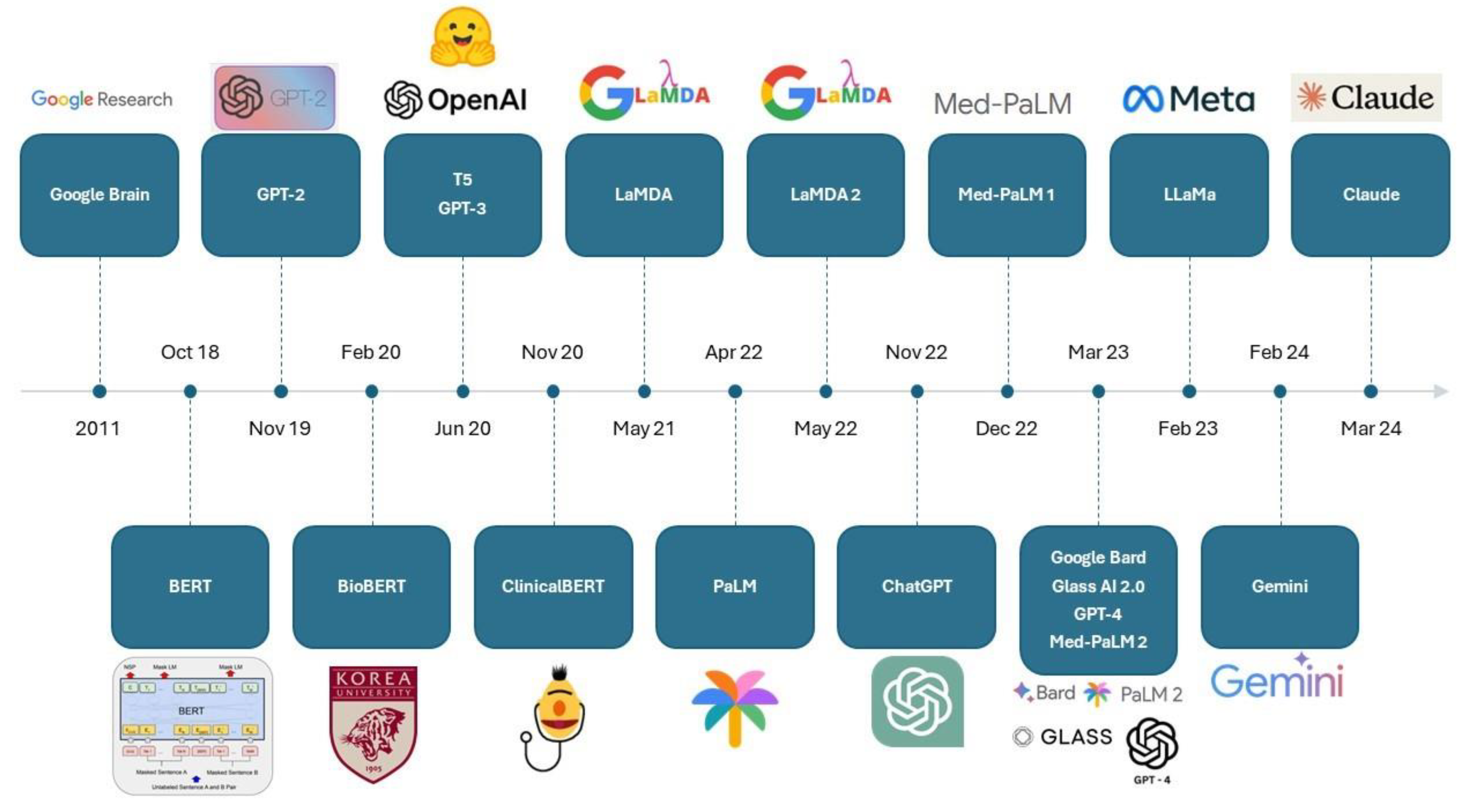

1. Introduction

- To evaluate how studies of LLM applications in ophthalmology were carried out, in terms of following clinical trial protocols followed, prompt techniques employed, benchmarking methods used, and ethical considerations.

- To examine how LLMs fared in key areas of healthcare application, including exam taking and patient education, diagnostic and management capability, and clinical administration.

- To highlight potential issues surrounding the present landscape of LLM applications of ophthalmology, and to discuss directions for future LLM research and development in ophthalmology.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Information Sources

- 1)

- For Ophthalmology: Ophthalmology, Ocular Surgery, Eye Disease, Eye Diseases, Eye Disorders.

- 2)

- For LLMs: Large Language Model, large language models, large language modelling, Chatbot, ChatGPT, GPT, chatbots, google bard, bing chat, BERT, RoBERTa, distilBERT, BART, MARIAN, llama, palm.

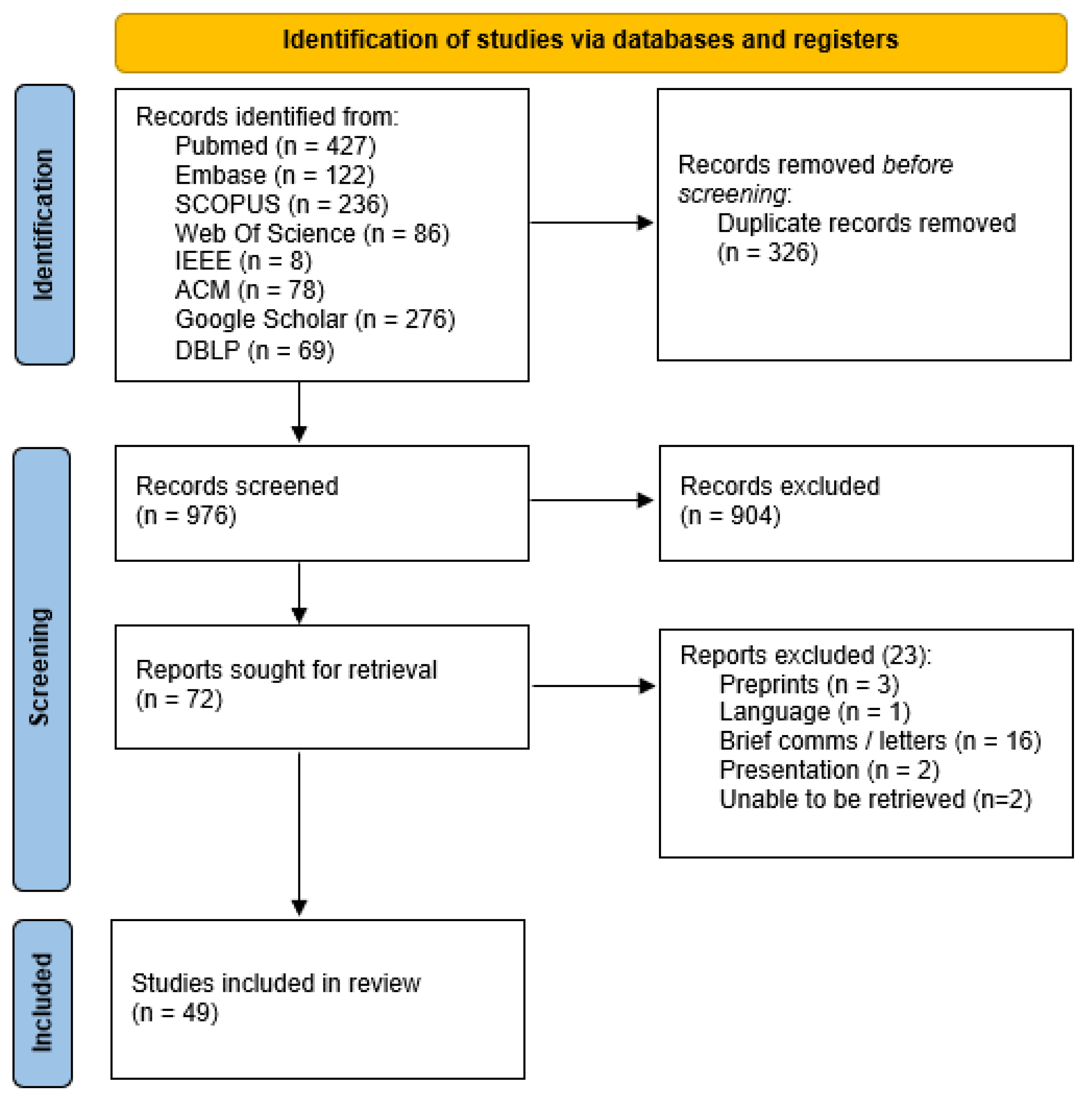

2.2. Selection Process and Eligibility Criteria

- 1)

- Peer reviewed primary research studies utilising LLMs.

- 2)

- Studies involving ophthalmology.

- 3)

- Studies published from January 2019 to March 2024.

- 1)

- Study designs that were reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, case reports, case series, guidelines, letters, correspondences, or protocols.

- 2)

- Studies that were not published in English.

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overall Study Characteristics

3.2. Breakdown of LLM Benchmarks Studied and General Observations

Human vs Artificial Intelligence

3.3. Performance of LLM in Exam-Taking and Patient Education

3.4. Diagnostic and Management Capabilities of LLM

3.5. Clinical Administration Tasks

3.6. LLM Inaccuracies and Harm

4. Discussion

4.1. Evaluation of Past Methodologies

4.1.1. Issues Regarding Standardisation

4.1.2. Harm and Patient Safety

4.1.3. Other Issues Relating to Study Design

4.2. Evaluation of LLM Performance

4.3. Directions for Future Works

4.3.1. Standard Framework for Assessing Accuracy, Validity and Harm

4.3.2. Greater Evaluation and Strategies Towards Ethical Considerations

4.3.3. Techniques for Improving LLM’s Accuracy and Interpretability

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusion

6. Glossary

Author Contributions

Funding

Literature search statement

- 1)

- In ophthalmology included: Ophthalmology, Ocular Surgery, Eye Disease, Eye Diseases, Eye Disorders.

- 2)

- For LLMs: Large Language Model, large language models, large language modelling, Chatbot, ChatGPT, GPT, chatbots, google bard, bing chat, BERT, RoBERTa, distilBERT, BART, MARIAN, llama, palm.

Conflict of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | Search terms used | Results |

| Pubmed | (Ophthalmology[MeSH Terms]) OR (Ocular Surgery) OR (Eye Disease) OR (Eye Diseases) OR (Eye Disorders) AND (Large Language Model) OR (large language models) OR (large language modelling) OR (Chatbot) OR (ChatGPT) OR (GPT) OR (chatbots) OR (google bard) OR (bing chat) OR (BERT) OR (RoBERTa) OR (distilBERT) OR (BART) OR (MARIAN) OR (llama) OR (palm) Limits: 2019 - 2024 |

427 Retrieved 11/02/2024 |

| Embase | ((Ophthalmology) OR (Ocular Surgery) OR (Eye Disease) OR (Eye Diseases) OR (Eye Disorders)).mp. AND (Large Language Model) OR (large language models) OR (large language modelling) OR (Chatbot) OR (ChatGPT) OR (GPT) OR (chatbots) OR (google bard) OR (bing chat) OR (BERT) OR (RoBERTa) OR (distilBERT) OR (BART) OR (MARIAN) OR (llama) OR (palm).mp. Limits: 2019 - 2024 |

122 Retrieved 11/02/2024 |

| SCOPUS | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((ophthalmology) OR (ocular AND surgery) OR (eye AND disease) OR (eye AND diseases) OR (eye AND disorders)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ((large AND language AND model) OR (large AND language AND models) OR (large AND language AND modelling) OR (chatbot) OR (chatgpt) OR (gpt) OR (chatbots) OR (google AND bard) OR (bing AND chat) OR (bert) OR (roberta) OR (distilbert) OR (bart) OR (marian))) Limits: 2019 - 2024 |

236 Retrieved 11/02/2024 |

| Web Of Science | (Ophthalmology) OR (Ocular Surgery) OR (Eye Disease) OR (Eye Diseases) OR (Eye Disorders) (Abstract) AND (Large Language Model) OR (large language models) OR (large language modelling) OR (Chatbot) OR (ChatGPT) OR (GPT) OR (chatbots) OR (google bard) OR (bing chat) OR (BERT) OR (RoBERTa) OR (distilBERT) OR (BART) OR (MARIAN) OR (llama) OR (palm) (Abstract) Limits: 2019 - 2024 |

86 Retrieved 11/02/2024 |

| IEEE | (("All Metadata":Ophthalmology) OR ("All Metadata":”Ocular Surgery”) OR ("All Metadata":”Eye Disease”) OR ("All Metadata":”Eye Diseases”) OR ("All Metadata":”Eye disorders”)) AND (("All Metadata":”Large Language Model”) OR ("All Metadata":large language models) OR ("All Metadata":ChatGPT) OR ("All Metadata":GPT) OR ("All Metadata":chatbots) OR ("All Metadata":Chatbot) OR ("All Metadata":”google bard”) OR ("All Metadata":”bing chat”) OR ("All Metadata":BERT) OR ("All Metadata":RoBERTa) OR ("All Metadata":distilBERT) OR ("All Metadata":BART) OR ("All Metadata":MARIAN) OR ("All Metadata":llama) OR ("All Metadata":palm)) Limits: 2019 – 2024 and journals |

8 Retrieved 11/02/2024 |

| ACM | [[All: ophthalmology] OR [All: "ocular surgery"] OR [All: "eye disease"] OR [All: "eye diseases"] OR [All: "eye disorders"]] AND [[All: "large language model"] OR [All: or] OR [All: "large language models"] OR [All: "chatgpt"] OR [All: "gpt"] OR [All: "chatbots"] OR [All: "chatbot"] OR [All: "google bard"] OR [All: "bing chat"] OR [All: "bert"] OR [All: "roberta"] OR [All: "distilbert"] OR [All: "bart"] OR [All: "marian"] OR [All: "llama"] OR [All: "palm"]] Limits: 2019 – 2024 |

78 Retrieved 11/02/2024 |

| Google Scholar | Ophthalmology "Large Language Model" -preprint Limits: 2019 - 2024 |

276 Retrieved 11/02/2024 |

| DBLP | ophthal* type:Journal_Articles: Limits: 2019 - 2024 |

69 Retrieved 11/02/2024 |

| Total | 1302 |

| Study | Scoring system for responses |

| Biswas 2023 | Likert scale where higher ratings indicated greater quality of information 1: very poor 2: poor 3: acceptable 4: good 5: very good |

| Nikdel 2023 | Acceptable, incomplete or unacceptable |

| Sharif 2024 | comprehensive, correct but inadequate, mixed with correct and incorrect/out-dated data or completely incorrect |

| Maywood 2024 | Correct and comprehensive, correct but inadequate, incorrect |

| Pushpanathan 2023 | Poor. borderline, good |

| Cappellani 2024 | -3: potentially dangerous -2: very poor -1: poor 0: no response 1: good 2: very good 2*: excellent |

| Patil 2024 | Likert scale of 5 from very poor (harmful and incorrect) to excellent (no errors or false claim) |

References

- De Angelis, L.; Baglivo, F.; Arzilli, G.; Privitera, G.P.; Ferragina, P.; Tozzi, A.E.; Rizzo, C. ChatGPT and the rise of large language models: the new AI-driven infodemic threat in public health. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1166120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haupt, C.E.; Marks, M. AI-Generated Medical Advice-GPT and Beyond. Jama 2023, 329, 1349–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, T.H.; Cheatham, M.; Medenilla, A.; Sillos, C.; De Leon, L.; Elepaño, C.; Madriaga, M.; Aggabao, R.; Diaz-Candido, G.; Maningo, J.; et al. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLOS Digit Health 2023, 2, e0000198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; He, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, T.; Zhai, X. Context Matters: A Strategy to Pre-train Language Model for Science Education. In Artificial Intelligence in Education. Posters and Late Breaking Results, Workshops and Tutorials, Industry and Innovation Tracks, Practitioners, Doctoral Consortium and Blue Sky; Springer Nature Switzerland: 2023; pp. 666–674.

- Potapenko, I.; Boberg-Ans, L.C.; Stormly Hansen, M.; Klefter, O.N.; van Dijk, E.H.C.; Subhi, Y. Artificial intelligence-based chatbot patient information on common retinal diseases using ChatGPT. Acta Ophthalmol 2023, 101, 829–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukarasu, A.J.; Hassan, R.; Mahmood, S.; Sanghera, R.; Barzangi, K.; El Mukashfi, M.; Shah, S. Trialling a Large Language Model (ChatGPT) in General Practice With the Applied Knowledge Test: Observational Study Demonstrating Opportunities and Limitations in Primary Care. JMIR Med Educ 2023, 9, e46599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betzler, B.K.; Chen, H.; Cheng, C.Y.; Lee, C.S.; Ning, G.; Song, S.J.; Lee, A.Y.; Kawasaki, R.; van Wijngaarden, P.; Grzybowski, A.; et al. Large language models and their impact in ophthalmology. Lancet Digit Health 2023, 5, e917–e924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.; Marie, A.; Ellershaw, S.; Korot, E.; Keane, P.A. New meaning for NLP: the trials and tribulations of natural language processing with GPT-3 in ophthalmology. Br J Ophthalmol 2022, 106, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, Z.D.; Cheng, C.Y. Application of big data in ophthalmology. Taiwan J Ophthalmol 2023, 13, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.; Lim, Z.W.; Pushpanathan, K.; Cheung, C.Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Chen, D.; Tham, Y.C. Review of emerging trends and projection of future developments in large language models research in ophthalmology. Br J Ophthalmol 2024, 108, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Yuan, L.; Wu, H.; Grzybowski, A.; Ye, J. Exploring large language model for next generation of artificial intelligence in ophthalmology. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1291404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Liu, X.; Rivera, S.C.; Moher, D.; Chan, A.W.; Sydes, M.R.; Calvert, M.J.; Denniston, A.K. Reporting guidelines for clinical trials of artificial intelligence interventions: the SPIRIT-AI and CONSORT-AI guidelines. Trials 2021, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O'Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 2018, 169, 467–473. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.J. ChatGPT and Lacrimal Drainage Disorders: Performance and Scope of Improvement. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2023, 39, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sharif, E.M.; Penteado, R.C.; Dib El Jalbout, N.; Topilow, N.J.; Shoji, M.K.; Kikkawa, D.O.; Liu, C.Y.; Korn, B.S. Evaluating the Accuracy of ChatGPT and Google BARD in Fielding Oculoplastic Patient Queries: A Comparative Study on Artificial versus Human Intelligence. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2024, 40, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antaki, F.; Milad, D.; Chia, M.A.; Giguère, C.; Touma, S.; El-Khoury, J.; Keane, P.A.; Duval, R. Capabilities of GPT-4 in ophthalmology: an analysis of model entropy and progress towards human-level medical question answering. Br J Ophthalmol 2024, 108, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antaki, F.; Touma, S.; Milad, D.; El-Khoury, J.; Duval, R. Evaluating the Performance of ChatGPT in Ophthalmology: An Analysis of Its Successes and Shortcomings. Ophthalmol Sci 2023, 3, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balas, M.; Janic, A.; Daigle, P.; Nijhawan, N.; Hussain, A.; Gill, H.; Lahaie, G.L.; Belliveau, M.J.; Crawford, S.A.; Arjmand, P.; et al. Evaluating ChatGPT on Orbital and Oculofacial Disorders: Accuracy and Readability Insights. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2024, 40, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, K.S.; You, J.Y.; Coleman, M.J.; Mathews, P.M.; Ray, V.L.; Riaz, K.M.; De Rojas, J.O.; Wang, A.S.; Watson, S.H.; Koo, E.H.; et al. Quality and Agreement With Scientific Consensus of ChatGPT Information Regarding Corneal Transplantation and Fuchs Dystrophy. Cornea 2024, 43, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, I.A.; Zhang, Y.V.; Govil, D.; Majid, I.; Chang, R.T.; Sun, Y.; Shue, A.; Chou, J.C.; Schehlein, E.; Christopher, K.L.; et al. Comparison of Ophthalmologist and Large Language Model Chatbot Responses to Online Patient Eye Care Questions. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2330320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Logan, N.S.; Davies, L.N.; Sheppard, A.L.; Wolffsohn, J.S. Assessing the utility of ChatGPT as an artificial intelligence-based large language model for information to answer questions on myopia. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2023, 43, 1562–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.Z.; Shaheen, A.; Jin, A.; Fukui, R.; Yi, J.S.; Yannuzzi, N.; Alabiad, C. Performance of Generative Large Language Models on Ophthalmology Board-Style Questions. Am J Ophthalmol 2023, 254, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellani, F.; Card, K.R.; Shields, C.L.; Pulido, J.S.; Haller, J.A. Reliability and accuracy of artificial intelligence ChatGPT in providing information on ophthalmic diseases and management to patients. Eye (Lond) 2024, 38, 1368–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćirković, A.; Katz, T. Exploring the Potential of ChatGPT-4 in Predicting Refractive Surgery Categorizations: Comparative Study. JMIR Form Res 2023, 7, e51798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delsoz, M.; Raja, H.; Madadi, Y.; Tang, A.A.; Wirostko, B.M.; Kahook, M.Y.; Yousefi, S. The Use of ChatGPT to Assist in Diagnosing Glaucoma Based on Clinical Case Reports. Ophthalmol Ther 2023, 12, 3121–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sensoy, E.; Citirik, M. Assessing the Competence of Artificial Intelligence Programs in Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus and Comparing their Relative Advantages. Rom J Ophthalmol 2023, 67, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, K.; Eid, A.; Wang, D.; Raiker, R.S.; Chen, S.; Nguyen, J. Optimizing Ophthalmology Patient Education via ChatBot-Generated Materials: Readability Analysis of AI-Generated Patient Education Materials and The American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Patient Brochures. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2024, 40, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro Desideri, L.; Roth, J.; Zinkernagel, M.; Anguita, R. Application and accuracy of artificial intelligence-derived large language models in patients with age related macular degeneration. International Journal of Retina and Vitreous 2023, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, T.; Pullen, S.; Birkett, L. Performance of ChatGPT and Bard on the official part 1 FRCOphth practice questions. Br J Ophthalmol 2024, 108, 1379–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, F.; Saade, J.S. Performance of ChatGPT on Ophthalmology-Related Questions Across Various Examination Levels: Observational Study. JMIR Med Educ 2024, 10, e50842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wang, S.Y. Predicting Glaucoma Progression Requiring Surgery Using Clinical Free-Text Notes and Transfer Learning With Transformers. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2022, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, H.U.; Kaakour, A.H.; Rachitskaya, A.; Srivastava, S.; Sharma, S.; Mammo, D.A. Evaluation and Comparison of Ophthalmic Scientific Abstracts and References by Current Artificial Intelligence Chatbots. JAMA Ophthalmol 2023, 141, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, C.; Edupuganti, N.R.; Patel, P.A.; Bui, T.; Sheth, V. Evaluating the Artificial Intelligence Performance Growth in Ophthalmic Knowledge. Cureus 2023, 15, e45700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianian, R.; Sun, D.; Crowell, E.L.; Tsui, E. The Use of Large Language Models to Generate Education Materials about Uveitis. Ophthalmol Retina 2024, 8, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianian, R.; Sun, D.; Giaconi, J. Can ChatGPT Aid Clinicians in Educating Patients on the Surgical Management of Glaucoma? J Glaucoma 2024, 33, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Z.W.; Pushpanathan, K.; Yew, S.M.E.; Lai, Y.; Sun, C.H.; Lam, J.S.H.; Chen, D.Z.; Goh, J.H.L.; Tan, M.C.J.; Sheng, B.; et al. Benchmarking large language models' performances for myopia care: a comparative analysis of ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4.0, and Google Bard. EBioMedicine 2023, 95, 104770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Shao, A.; Shen, W.; Ye, P.; Wang, Y.; Ye, J.; Jin, K.; Yang, J. Uncovering Language Disparity of ChatGPT on Retinal Vascular Disease Classification: Cross-Sectional Study. J Med Internet Res 2024, 26, e51926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, R.J.; Arepalli, S.R.; Fromal, O.; Choi, J.D.; Jain, N. Artificial intelligence chatbot performance in triage of ophthalmic conditions. Can J Ophthalmol 2024, 59, e301–e308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maywood, M.J.; Parikh, R.; Deobhakta, A.; Begaj, T. PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT OF AN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE CHATBOT IN CLINICAL VITREORETINAL SCENARIOS. Retina 2024, 44, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshirfar, M.; Altaf, A.W.; Stoakes, I.M.; Tuttle, J.J.; Hoopes, P.C. Artificial Intelligence in Ophthalmology: A Comparative Analysis of GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and Human Expertise in Answering StatPearls Questions. Cureus 2023, 15, e40822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikdel, M.; Ghadimi, H.; Tavakoli, M.; Suh, D.W. Assessment of the Responses of the Artificial Intelligence-based Chatbot ChatGPT-4 to Frequently Asked Questions About Amblyopia and Childhood Myopia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2024, 61, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.; Kedia, N.; Harihar, S.; Vupparaboina, S.C.; Singh, S.R.; Venkatesh, R.; Vupparaboina, K.; Bollepalli, S.C.; Chhablani, J. Applying large language model artificial intelligence for retina International Classification of Diseases (ICD) coding. Journal of Medical Artificial Intelligence 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthier, C.; Gatinel, D. Success of ChatGPT, an AI language model, in taking the French language version of the European Board of Ophthalmology examination: A novel approach to medical knowledge assessment. J Fr Ophtalmol 2023, 46, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, N.S.; Huang, R.; Mihalache, A.; Kisilevsky, E.; Kwok, J.; Popovic, M.M.; Nassrallah, G.; Chan, C.; Mallipatna, A.; Kertes, P.J.; et al. THE ABILITY OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE CHATBOTS ChatGPT AND GOOGLE BARD TO ACCURATELY CONVEY PREOPERATIVE INFORMATION FOR PATIENTS UNDERGOING OPHTHALMIC SURGERIES. Retina 2024, 44, 950–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapenko, I.; Malmqvist, L.; Subhi, Y.; Hamann, S. Artificial Intelligence-Based ChatGPT Responses for Patient Questions on Optic Disc Drusen. Ophthalmol Ther 2023, 12, 3109–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpanathan, K.; Lim, Z.W.; Er Yew, S.M.; Chen, D.Z.; Hui'En Lin, H.A.; Lin Goh, J.H.; Wong, W.M.; Wang, X.; Jin Tan, M.C.; Chang Koh, V.T.; et al. Popular large language model chatbots' accuracy, comprehensiveness, and self-awareness in answering ocular symptom queries. iScience 2023, 26, 108163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, K.; S, T.; C, S.D.; M, S.; Rajalakshmi, R.; Raman, R. The Utility of ChatGPT in Diabetic Retinopathy Risk Assessment: A Comparative Study with Clinical Diagnosis. Clin Ophthalmol 2023, 17, 4021–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Carabali, W.; Sen, A.; Agarwal, A.; Tan, G.; Cheung, C.Y.; Rousselot, A.; Agrawal, R.; Liu, R.; Cifuentes-González, C.; Elze, T.; et al. Chatbots Vs. Human Experts: Evaluating Diagnostic Performance of Chatbots in Uveitis and the Perspectives on AI Adoption in Ophthalmology. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2024, 32, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Carabali, W.; Cifuentes-González, C.; Wei, X.; Putera, I.; Sen, A.; Thng, Z.X.; Agrawal, R.; Elze, T.; Sobrin, L.; Kempen, J.H.; et al. Evaluating the Diagnostic Accuracy and Management Recommendations of ChatGPT in Uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2024, 32, 1526–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, D.; Maeda, T.; Ozaki, A.; Kanda, G.N.; Kurimoto, Y.; Takahashi, M. Performance of ChatGPT in Board Examinations for Specialists in the Japanese Ophthalmology Society. Cureus 2023, 15, e49903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensoy, E.; Citirik, M. A comparative study on the knowledge levels of artificial intelligence programs in diagnosing ophthalmic pathologies and intraocular tumors evaluated their superiority and potential utility. Int Ophthalmol 2023, 43, 4905–4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemer, A.; Cohen, M.; Altarescu, A.; Atar-Vardi, M.; Hecht, I.; Dubinsky-Pertzov, B.; Shoshany, N.; Zmujack, S.; Or, L.; Einan-Lifshitz, A.; et al. Diagnostic capabilities of ChatGPT in ophthalmology. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2024, 262, 2345–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M.B.; Fu, J.J.; Chow, J.; Teng, C.C. Development and Evaluation of Aeyeconsult: A Novel Ophthalmology Chatbot Leveraging Verified Textbook Knowledge and GPT-4. J Surg Educ 2024, 81, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Djalilian, A.; Ali, M.J. ChatGPT and Ophthalmology: Exploring Its Potential with Discharge Summaries and Operative Notes. Semin Ophthalmol 2023, 38, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tailor, P.D.; Dalvin, L.A.; Chen, J.J.; Iezzi, R.; Olsen, T.W.; Scruggs, B.A.; Barkmeier, A.J.; Bakri, S.J.; Ryan, E.H.; Tang, P.H.; et al. A Comparative Study of Responses to Retina Questions from Either Experts, Expert-Edited Large Language Models, or Expert-Edited Large Language Models Alone. Ophthalmol Sci 2024, 4, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taloni, A.; Borselli, M.; Scarsi, V.; Rossi, C.; Coco, G.; Scorcia, V.; Giannaccare, G. Comparative performance of humans versus GPT-4.0 and GPT-3.5 in the self-assessment program of American Academy of Ophthalmology. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 18562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, B.K.; Handzic, A.; Hua, N.J.; Vosoughi, A.R.; Margolin, E.A.; Micieli, J.A. Utility of ChatGPT for Automated Creation of Patient Education Handouts: An Application in Neuro-Ophthalmology. J Neuroophthalmol 2024, 44, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teebagy, S.; Colwell, L.; Wood, E.; Yaghy, A.; Faustina, M. Improved Performance of ChatGPT-4 on the OKAP Examination: A Comparative Study with ChatGPT-3.5. J Acad Ophthalmol (2017) 2023, 15, e184–e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, T.I.; Roos, J.; Kaczmarczyk, R. Large Language Models for Therapy Recommendations Across 3 Clinical Specialties: Comparative Study. J Med Internet Res 2023, 25, e49324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Lee, D.A.; Zhao, W.; Wong, A.; Sidhu, S. ChatGPT: is it good for our glaucoma patients? Frontiers in Ophthalmology 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, I.B.E.; Doğan, L. Talking technology: exploring chatbots as a tool for cataract patient education. Clin Exp Optom 2025, 108, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandi, R.; Fahey, J.D.; Drakopoulos, M.; Bryan, J.M.; Dong, S.; Bryar, P.J.; Bidwell, A.E.; Bowen, R.C.; Lavine, J.A.; Mirza, R.G. Exploring Diagnostic Precision and Triage Proficiency: A Comparative Study of GPT-4 and Bard in Addressing Common Ophthalmic Complaints. Bioengineering (Basel) 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz Rivera, S.; Liu, X.; Chan, A.-W.; Denniston, A.K.; Calvert, M.J.; Darzi, A.; Holmes, C.; Yau, C.; Moher, D.; Ashrafian, H.; et al. Guidelines for clinical trial protocols for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the SPIRIT-AI extension. Nature Medicine 2020, 26, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karargyris, A.; Umeton, R.; Sheller, M.J.; Aristizabal, A.; George, J.; Wuest, A.; Pati, S.; Kassem, H.; Zenk, M.; Baid, U.; et al. Federated benchmarking of medical artificial intelligence with MedPerf. Nature Machine Intelligence 2023, 5, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Communications Networks, C.; Technology. Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI; Publications Office: 2019.

- Dave, T.; Athaluri, S.A.; Singh, S. ChatGPT in medicine: an overview of its applications, advantages, limitations, future prospects, and ethical considerations. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, S.K.; Hong, C.S.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, C. A Complete Survey on LLM-based AI Chatbots. arXiv [cs.CL] 2024.

- Waisberg, E.; Ong, J.; Masalkhi, M.; Zaman, N.; Sarker, P.; Lee, A.G.; Tavakkoli, A. GPT-4 and medical image analysis: strengths, weaknesses and future directions. Journal of Medical Artificial Intelligence 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, D.M.; Simons, G.F.; Fennig, C.D. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Twenty-eighth edition. 2025.

- Wang, M.Y.; Asanad, S.; Asanad, K.; Karanjia, R.; Sadun, A.A. Value of medical history in ophthalmology: A study of diagnostic accuracy. J Curr Ophthalmol 2018, 30, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S. Evaluating large language models for use in healthcare: A framework for translational value assessment. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2023, 41, 101304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-J.; Pillai, A.; Deng, J.; Guo, E.; Gupta, M.; Paget, M.; Naugler, C. Assessing the research landscape and clinical utility of large language models: a scoping review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2024, 24, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Zhou, H.; Yin, Q.; Yang, J.; Tang, X.; Luo, C.; Zeng, M.; Jiang, H.; Gao, Y.; et al. Large Language Models in the Clinic: A Comprehensive Benchmark. arXiv [cs.CL] 2024.

- Mohammadi, I.; Firouzabadi, S.R.; Kohandel Gargari, O.; Habibi, G. Standardized Assessment Framework for Evaluations of Large Language Models in Medicine (SAFE-LLM). Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuş, Z.; Aydin, M. MedSegBench: A comprehensive benchmark for medical image segmentation in diverse data modalities. Scientific Data 2024, 11, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T.; Kumar, A.; Agarwal, C.; Lakkaraju, H. MedSafetyBench: Evaluating and Improving the Medical Safety of Large Language Models. arXiv [cs.AI] 2024.

- Privacy policy | OpenAI.

- Ong, J.C.L.; Chang, S.Y.; William, W.; Butte, A.J.; Shah, N.H.; Chew, L.S.T.; Liu, N.; Doshi-Velez, F.; Lu, W.; Savulescu, J.; et al. Ethical and regulatory challenges of large language models in medicine. Lancet Digit Health 2024, 6, e428–e432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mugaanyi, J.; Cai, L.; Cheng, S.; Lu, C.; Huang, J. Evaluation of Large Language Model Performance and Reliability for Citations and References in Scholarly Writing: Cross-Disciplinary Study. J Med Internet Res 2024, 26, e52935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, R.; Heston, T.F.; Bhuse, V. Prompt Engineering in Healthcare. Electronics 2024, 13, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillinger, D. Social Determinants, Health Literacy, and Disparities: Intersections and Controversies. Health Lit Res Pract 2021, 5, e234–e243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ghadban, Y.; Lu, H.; Adavi, U.; Sharma, A.; Gara, S.; Das, N.; Kumar, B.; John, R.; Devarsetty, P.; Hirst, J.E. Transforming Healthcare Education: Harnessing Large Language Models for Frontline Health Worker Capacity Building using Retrieval-Augmented Generation. medRxiv, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Colquhoun, H.; Garritty, C.M.; Hempel, S.; Horsley, T.; Langlois, E.V.; Lillie, E.; O’Brien, K.K.; Tunçalp, Ӧ.; et al. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Systematic Reviews 2021, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness, R. In Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews, Eden, J., Levit, L., Berg, A., Morton, S., Eds.; National Academies Press (US).

- Copyright 2011 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.: Washington (DC), 2011.

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O'Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Clinical Application | LLM |

| Singh 2023 [55] | Administrative | GPT 3.5 |

| Barclay 2023 [20] | Clinical Knowledge | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 |

| Rojas-Carabali (1) 2023 [49] | Diagnostic | GPT 3.5, GPT 4.0. Glass 1.0 |

| Ali 2023 [15] | Diagnostic | GPT 3.5 |

| Shemer 2024 [53] | Diagnostic | GPT 3.5 |

| Rojas-Carabali (2) 2023 [50] | Diagnostic | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 |

| Delsoz 2023 [26] | Diagnostic | GPT 3.5 |

| Sensoy 2023 (1) [27] | Exam Taking | GPT 3.5, Bing, Bard |

| Moshirfar 2023 [41] | Exam Taking | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 |

| Sensoy 2023 (2) [52] | Exam Taking | GPT 3.5, Bing, Bard |

| Antaki 2023 (1) [17] | Exam Taking | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 |

| Taloni 2023 [57] | Exam Taking | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 |

| Singer 2023 [54] | Exam Taking | Aeyeconsult, GPT 4 |

| Jiao 2023 [34] | Exam Taking | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 |

| Antaki 2023 (2) [18] | Exam Taking | ChatGPT legacy and ChatGPT Plus |

| Teebagy 2023 [59] | Exam Taking | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 |

| Fowler 2023 [30] | Exam Taking | GPT 4, Bard |

| Sakai 2023 [51] | Exam Taking | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 |

| Haddad 2024 [31] | Exam Taking | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 |

| Cai 2023 [23] | Exam Taking | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Bing Chat |

| Panthier 2023 [44] | Exam Taking | GPT 4 |

| Hua 2023 [33] | Manuscript Writing | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 |

| Tailor 2024 [56] | Patient Education | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Claude 2, Bing, Bard |

| FerroDesideri 2023 [29] | Patient Education | GPT 3.5, Bard, Bing Chat |

| Potapenko 2023 [46] | Patient Education | GPT 4 |

| Biswas 2023 [22] | Patient Education | GPT 3.5 |

| Nikdel 2023 [42] | Patient Education | GPT 4 |

| Lim 2023 [37] | Patient Education | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Bard |

| Kianian 2023 (1) [36] | Patient Education | GPT 3.5 |

| Wu 2023 [61] | Patient Education | GPT 3.5 |

| Bernstein 2023 [21] | Patient Education | GPT 3.5 |

| Balas 2024 [19] | Patient Education | GPT 4 |

| Al-Sharif 2024 [16] | Patient Education | GPT 3.5, Bard |

| Zandi 2024 [63] | Patient Education | GPT 4, Bard |

| Eid 2023 [28] | Patient Education | GPT 4.0, Bard |

| Pushpanathan 2023 [47] | Patient Education | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Bard |

| Cappellani 2024 [24] | Patient Education | GPT 3.5 |

| Yılmaz 2024 [62] | Patient Education | GPT 3.5, Bard, Bing AI, AAO website |

| Patil 2024 [45] | Patient Education | GPT 4, Bard |

| Kianian 2023 (2) [35] | Patient Education | GPT 4, Bard |

| Liu 2024 [38] | Patient Education | GPT 3.5 |

| Tao 2024 [58] | Patient Education | GPT 3.5 |

| Wilhelm 2023 [60] | Patient Management | GPT 3.5 Turbo, Command-xlarge-nightly, Claude, Bloomz |

| Maywood 2024 [40] | Patient Management | GPT 3.5 Turbo |

| Cirkovic 2023 [25] | Prognostication | GPT 4 |

| Hu 2022 [32] | Prognostication | BERT, RoBerta, DistilBert, BioBERT |

| Raghu 2023 [48] | Prognostication | GPT 4 |

| Ong 2023 [43] | Text interpretation | GPT 3.5 |

| Lyons 2023 [39] | Triage | GPT 4, Bing Chat, WebMD |

| Study | Usage of a research protocol for AI | Ethical / Safety Safeguards considered in methodology | Ethics in Discussion | Prompt Techniques Employed | Prompt examples shared | Benchmarks on Correctness | Benchmarks on Harm |

| Tailor 2024 | No | Yes | Yes | zero-shot (no prior context) | Yes | Human | Human |

| Sensoy 2023 (1) | No | No | No | Zero-shot | No | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| FerroDesideri 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Nil |

| Ong 2023 | No | No | Yes | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Lyons 2023 | No | No | Yes | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Nil |

| Moshirfar 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Potapenko 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Nil |

| Sensoy 2023 (2) | No | No | No | Zero-shot | No | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Biswas 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Nil |

| Nikdel 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot, Prompt Chaining | Yes | Human | Nil |

| Lim 2023 | No | No | Yes | Zero-shot, Iterative Prompting | Yes | Human | Nil |

| Kianian 2023 (1) | No | No | No (safety but not ethics) | One-shot, Few-shot | Yes | Automated and Human | Nil |

| Antaki 2023 (1) | No | No | No (safety but not ethics) | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Nil |

| Rojas-Carabali (1) 2023 | No | No | No (safety but not ethics) | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (Exact match) and Human | Nil |

| Ali 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Nil |

| Singh 2023 | No | No | No | Contextual Priming | Yes | Human | Nil |

| Wu 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (Exact match, Readability) | Nil |

| Taloni 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | No | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Bernstein 2023 | No | Yes | Yes | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Human |

| Singer 2023 | No | No | No (safety but not ethics) | Zero-shot | No | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Shemer 2024 | No | Yes | No | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Balas 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | No | Human | Nil |

| Al-Sharif 2024 | No | No | Yes | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Nil |

| Jiao 2023 | No | No | Yes | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Rojas-Carabali (2) 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Antaki 2023 (2) | No | No | No (safety but not ethics) | Zero-shot | No | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Hua 2023 | No | No | Yes | Zero-shot | No | Human | Nil |

| Zandi 2024 | No | Yes | No (safety but not ethics) | Zero-shot | No | Human | Human |

| Cirkovic 2023 | No | No? | No | Zero-shot | No | Statistical Analysis including Cohen κ coefficient, a chi-square test, a confusion matrix, accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and receiver operating characteristic area under the curve | Nil |

| Teebagy 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | No | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Wilhelm 2023 | No | Yes | No (safety but not ethics) | Zero-shot | No | Automated and Human | Automated and Human |

| Eid 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (readability) | Nil |

| Maywood 2024 | No | Yes | No (safety but not ethics) | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Human |

| Fowler 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | No | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Sakai 2023 | No | No | No | Zero shot, Few-shot | Yes | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Haddad 2024 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Cai 2023 | No | No | No (safety but not ethics) | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Pushpanathan 2023 | No | No | No (safety but not ethics) | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Hu 2022 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (Exact match, F1 score) | Nil |

| Barclay 2023 | No | Yes | No (safety but not ethics) | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Human |

| Cappellani 2024 | No | Yes | No (safety but not ethics) | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Human |

| Panthier 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (Exact match) | Nil |

| Yılmaz 2024 | No | No | No (safety but not ethics) | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated | Nil |

| Patil 2024 | No | No | Yes | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Human |

| Delsoz 2023 | No | No | No | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Nil |

| Kianian 2023 (2) | No | No | Yes | Zero-shot | Yes | Automated (readability) | Nil |

| Raghu 2023 | No | No | Yes | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Nil |

| Liu 2024 | No | No | No | Zero-shot, Chain-of-thought (inspired) | Yes | Automated | Nil |

| Tao 2024 | No | Yes | Yes | Zero-shot | Yes | Human | Human |

| (a) | |||||

| Study | Setting | Scoring system | Result | ||

| Barclay 2023 [20] | Clinical Knowledge | 5 Point Scale | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 | ||

| Rojas-Carabali (1) 2023 | Diagnostic | Correct or Incorrect | Experts > GPT 4 = GPT 3.5 > Glass 1.0 | ||

| Rojas-Carabali (2) 2023 | Diagnostic | Correct or Incorrect | Ophthalmologist > AI | ||

| Singer 2023 | Exam Taking | Correct or Incorrect | Aeyeconsult > GPT 4 | ||

| Antaki 2023 (2) | Exam Taking | Correct or Incorrect | Plus > Legacy | ||

| Sensoy 2023 (1) | Exam Taking | Correct or Incorrect | Bard > Bing > GPT 3.5 | ||

| Sensoy 2023 (2) | Exam Taking | Correct, Incorrect or Unable to Answer | Bard > Bing > GPT 3.5 | ||

| Moshirfar 2023 | Exam Taking | Correct or Incorrect | GPT 4 > humans > GPT 3.5 | ||

| Antaki 2023 (1) | Exam Taking | Correct or Incorrect | GPT 4-0.3 > GPT 4-0.7 > GPT 4-1 = GPT 4-0 > GPT 3.5 | ||

| Taloni 2023 | Exam Taking | Correct or Incorrect | GPT 4 > Humans > GPT 3.5 | ||

| Jiao 2023 | Exam Taking | Correct or Incorrect | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 | ||

| Teebagy 2023 | Exam Taking | Correct or Incorrect | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 | ||

| Sakai 2023 | Exam Taking | Correct or Incorrect | Humans > GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 | ||

| Haddad 2024 | Exam Taking | Correct or Incorrect | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 | ||

| Cai 2023 | Exam Taking | Correct or Incorrect | Humans > GPT 4 = Bing > GPT 3.5 | ||

| Fowler 2023 | Exam Taking | Correct or Incorrect | GPT 4 > Bard | ||

| Yılmaz 2024 | Patient Education | SOLO score | ChatGPT > Bard > Bing > AAO | ||

| Pushpanathan 2023 | Patient Education | 5 Point Scale | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 > Bard | ||

| Al-Sharif 2024 | Patient Education | 4 Point Scale | GPT 3.5 > Bard | ||

| FerroDesideri 2023 | Patient Education | 3 Point Scale | GPT 3.5 > Bard = Bing | ||

| Tailor 2024 | Patient Education | 5 Point Scale | Expert + AI > GPT 3.5 > GPT 4> Expert only > Claude > Bard > Bing | ||

| Lim 2023 | Patient Education | 3 Point Scale | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 > Bard | ||

| Zandi 2024 | Patient Education | Correct or Incorrect | GPT 4 > Bard | ||

| Patil 2024 | Patient Education | 5 Point Scale | ChatGPT > Bard | ||

| Wilhelm 2023 | Patient Management | mDISCERN | Claude-instant-v1.0 > GPT 3.5-Turbo > Command-xlarge-nightly > Bloomz | ||

| Hu 2022 | Prognostication | AUROC, F1 | BERT > RoBERTa > DistilBERT > BioBert > Humans | ||

| Lyons 2023 | Triage | 5 Point Scale | Ophthalmologists in training > chatGPT > Bing Chat > WebMD | ||

| (b) | |||||

| Study | LLMs | Setting | Scoring system | Result | |

| Ali 2023 | GPT 3.5 | Diagnostic | 3 Point Scale | 40% correct 35% partially correct 25% outright incorrect |

|

| Shemer 2024 | GPT 3.5 | Diagnostic | Correct or Incorrect | Residents > Attendings > GPT 3.5 | |

| Delsoz 2023 | GPT 3.5 | Diagnostic | Correct or Incorrect | ChatGPT performed similarly to 2 of 3 residents and better than 1 resident | |

| Panthier 2023 | GPT 4 | Exam Taking | Correct or Incorrect | 6188 / 6785 correct | |

| Biswas 2023 | GPT 3.5 | Patient Education | 5 Point Scale | 66 / 275 responses rated as very good 134 / 275 responses rated as good 60 / 275 acceptable 10 / 275 poor 5 / 275 very poor |

|

| Bernstein 2023 | GPT 3.5 | Patient Education | Comparison to humans | GPT 3.5 = Humans | |

| Cappellani 2024 | GPT 3.5 | Patient Education | 5 Point Scale | 93 responses scored >= 1 27 responses scored =< -1 9 responses scored -3 |

|

| Liu 2024 | GPT 3.5 | Patient Education | Correct or Incorrect | Ophthalmology Attendings > Ophthalmology Interns > English Prompt > Chinese Prompting of ChatGPT | |

| Tao 2024 | GPT 3.5 | Patient Education | 4 Point Scale | 2.43 95% CI 1.21, 3.65 | |

| Potapenko 2023 | GPT 4 | Patient Education | Correct or Incorrect | 17 / 100 responses were relevant without inaccuracies 78 / 100 relevant with inaccuracies that were not harmful 5 /100 relevant with inaccuracies potentially harmful |

|

| Nikdel 2023 | GPT 4 | Patient Education | 3 Point Scale | 93 / 110 acceptable | |

| Balas 2024 | GPT 4 | Patient Education | 7 Point Scale | 43 / 100 scored 6 53 / 100 scored 5 3 / 100 scored 4 1 / 100 scored 3 |

|

| Maywood 2024 | GPT 3.5 Turbo | Patient Management | Correct or Incorrect | 33/40 correct 21/40 comprehensive |

|

| Cirkovic 2023 | GPT 4 | Prognostication | Cohens Kappa | 6 categories: k = 0.399 2 categories: k = 0.610 |

|

| Raghu 2023 | GPT 4 | Prognostication | Cohens Kappa | With central subfield thickness: k = 0.263 Without central subfield thickness: k = 0.351 |

|

| Ong 2023 | GPT 3.5 | Text interpretation | Correct: producing at least one correct ICD code Correct only: only the correct ICD code Incorrect: not generating any |

Correct: 137 / 181 Correct only: 106/181 Incorrect: 54/181 |

|

| Study | Setting | Results |

| Rojas-Carabali (1) 2023 | Diagnostic | Humans > GPT 4 > Glass |

| Shemer 2024 | Diagnostic | Humans > GPT 3.5 |

| Rojas-Carabali (2) 2023 | Diagnostic | Humans > GPT -3.5 and 4 (collectively) |

| Delsoz 2023 | Diagnostic | Humans = GPT 3.5 |

| Moshirfar 2023 | Exam Taking | GPT 4 > Humans > GPT 3.5 |

| Antaki 2023 (1) | Exam Taking | GPT 4 > Humans |

| Taloni 2023 | Exam Taking | GPT 4 > Humans > GPT 3.5 |

| Fowler 2023 | Exam Taking | GPT 4 > Humans > Bard |

| Sakai 2023 | Exam Taking | Humans > GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 |

| Haddad 2024 | Exam Taking | Humans > GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 |

| Cai 2023 | Exam Taking | Humans > GPT 4 > Bing > GPT 3.5 |

| Tailor 2024 | Patient Education | Quality: Expert + AI = GPT 3.5 = GPT 4 > Expert > Claude > Bard > Bing Empathy: GPT 3.5 = Expert + AI = GPT 4 > Bard > Claude > Expert > Bing |

| Bernstein 2023 | Patient Education | GPT 3.5 = Humans |

| Liu 2024 | Patient Education | Humans > GPT 3.5 |

| Cirkovic 2023 | Prognostication | Humans = GPT 4 |

| Lyons 2023 | Triage | Human > GPT 4 > Bing > WebMD Symptom Checker |

| Study | Moshirfar 2023 | Taloni 2023 | Singer 2023 | Jiao 2023 | Antaki 2023 (1) | Antaki 2023 (2) | Teebagy 2023 | Sakai 2023 | Haddad 2024 | Cai 2023 | Patil 2024 |

| Clinical application | Exam Taking | Exam Taking | Exam Taking | Exam Taking | Exam Taking | Exam Taking | Exam Taking | Exam Taking | Exam Taking | Exam Taking | Patient Education |

| LLMs | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | Aeyeconsult, GPT 4 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | ChatGPT legacy and ChatGPT Plus | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Bing Chat | GPT 4, Bard |

| Overall | GPT 4 (73%) > Humans (58%) > GPT 3.5 (55%) | GPT 4 (82.4%) > Humans (75.7%) > GPT 3.5 (65.9%) | Aeyeconsult (83.4%) > GPT 4 (69.2%) | GPT 4 (75%) > GPT 3.5 (46%) | GPT 4-0.3 (72.9%) > Humans (68.15%) > GPT 3.5 (54.6%) | Plus (54.3%) > Legacy (49.25%) | GPT 4 (81%) > GPT 3.5 (57%) | Humans (65.7%) > GPT 4 (46.2% with prompt, 45.8% without) > GPT 3.5 (22.4%) | Humans (70 - 75%) > GPT 4 (70%) > GPT 3.5 (55%) | Humans (72.2%) > GPT 4 (71.6%) > Bing (71.2%) > GPT 3.5 (58.8%) | - |

| Cornea | GPT 3.5 = GPT 4 = Human | GPT 4 > Human = GPT 3.5 | Aeyeconsult = GPT 4 | GPT 4 = GPT 3.5 | GPT 4-1 > GPT 4-0.7 = GPT 4-0 > GPT 4-3 > GPT 3.5 | Plus > Legacy | GPT 4 > 3.5 | GPT 4 (few shot) > GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4 = GPT 3.5 | Human > Bing > GPT 4.0 > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4 > Bard |

| Glaucoma | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 = Human | GPT 4 > Human > GPT 3.5 | Aeyeconsult > GPT 4 | GPT 4 = GPT 3.5 | GPT 4-1 > GPT 4-0.7 = GPT 4-0.3 = GPT 4-0 > GPT 3.5 | Plus > Legacy | GPT 4 > 3.5 | GPT 4 > GPT 4 (few shot) > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4 = GPT 3.5 | Human > GPT 4.0 = Bing > GPT 3.5 | - |

| NeuroOphth | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 > Human | GPT 4 = Human > GPT 3.5 | Aeyeconsult > GPT 4 | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4-1 = GPT 4-0.3 = GPT 4-0 > GPT 4-0.7 > GPT 3.5 | Plus > Legacy | GPT 4 > 3.5 | GPT 4 (few shot) > GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4 = GPT 3.5 | Human > Bing > GPT 4.0 > GPT 3.5 | - |

| Uveitis | GPT 4 > Human = GPT 3.5 | GPT 4 > Human = GPT 3.5 | GPT 4 > Aeyeconsult | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4-1 = GPT 4-0.7 = GPT 4-0.3 = GPT 4-0 > GPT 3.5 | Plus > Legacy (BSCS) Legacy > Plus (OphtoQuestions) |

GPT 4 > 3.5 | GPT 4 (few shot) > GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 | - | GPT 4.0 > Human = Bing > GPT 3.5 | - |

| Lens and cataract | GPT 3.5 = GPT 4 = Human | GPT 4 = Human > GPT 3.5 | Aeyeconsult > GPT 4 | - | GPT 4-0.7 = GPT 4-0.3 > GPT 4-1 = GPT 4-0 > GPT 3.5 | Legacy > Plus (BCSC) Plus > Legacy (OphthoQuestions) |

GPT 4 > 3.5 | GPT 4 > GPT 4 (few shot) > GPT 3.5* | GPT 3.5 > GPT 4 | Human = GTP4 > Bing > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4 > Bard |

| Paediatric and strabs | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 = Human | GPT 4 = Human > GPT 3.5 | Aeyeconsult > GPT 4 | GPT 4 = GPT 3.5 | GPT 4-1 = GPT 4-0.7 = GPT 4-0.3 = GPT 4-0 > GPT 3.5 | Legacy > Plus (BCSC) Plus > Legacy (OphthoQuestions) |

GPT 4 > 3.5 | GPT 4 > GPT 4 (few shot) > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4 = GPT 3.5 | GPT 4.0 > Bing > Human > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4 > Bard |

| Retina & Vitreous | GPT 3.5 = GPT 4 = Human | GPT 4 = Human = GPT 3.5 | Aeyeconsult > GPT 4 | GPT 4 = GPT 3.5 | GPT 4-0.7 > GPT 4-0.3 > GPT 4-1 = GPT 4-0 > GPT 3.5 | Plus > Legacy | GPT 4 > 3.5 | GPT 4 = GPT 4 (few shot) > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4 = GPT 3.5- | Bing > GPT 4.0 > Humanss > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4 > Bard |

| Oculoplastics | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 = Human | GPT 4 > Human = GPT 3.5 | Aeyeconsult > GPT 4 | GPT 3.5 > GPT 4 | GPT 4-0.3 = GPT 4-0 > GPT 4-1 = GPT 4-0.7 > GPT 3.5 | Legacy > Plus | GPT 4 > 3.5 | GPT 4 > GPT 4 (few shot) > GPT 3.5+ | GPT 4 = GPT 3.5 | GPT 4.0 > Bing > Human > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4 > Bard |

| Optics | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 = Human | - | Aeyeconsult > GPT 4 | - | GPT 4-0.3 > GPT 4-0.7 > GPT 4-0 > GPT 4-1 > GPT 3.5 | Legacy > Plus (BCSC) Plus > Legacy (OphthoQuestions) |

GPT 4 > 3.5 | - | GPT 4 = GPT 3.5# | Human > GPT 4.5 = Bing > GPT 3.5 | - |

| Refractive Surgery | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 = Human | GPT 4 > Human > GPT 3.5 | Aeyeconsult > GPT 4 | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4-0.7 > GPT 4-1 = GPT 4-0 > GPT 4-0.3 > GPT 3.5 | ChatGPT Plus = ChatGPT Legacy | GPT 4 > 3.5 | GPT 4 > GPT 4 (few shot) > GPT 3.5* | GPT 4 = GPT 3.5# | - | Bard > GPT 4 |

| Pathology | GPT 4 > Human = GPT 3.5 | GPT 4 = Human = GPT 3.5 | Aeyeconsult > GPT 4 | GPT 4 > GPT 3.5 | GPT 4-0.7 = GPT 4-0.3 = GPT 4-0 > GPT 4-1 > GPT 3.5 | Plus > Legacy | GPT 4 > 3.5 | GPT 4 > GPT 4 (few shot) > GPT 3.5+ | GPT 4 = GPT 3.5- | - | - |

| Study | LLMs | Scoring systems | Performance |

| Eid 2023 | GPT 4, Bard | Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease, Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, Gunning Fog Index, Coleman-Liau Index, Simple measure of Gobbledygook, Automated readability Index, Linsear write readability score | FKRE: GPT 4 w/ prompt > Bard w/ prompt > Bard > ASOPRS > GPT 4 GFI: GPT 4 > ASOPRS > Bard > Bard w/ prompt > GPT 4 w/ prompt FKGL: GPT 4 > ASOPRS > Bard > Bard w/ prompt > GPT 4 w/ prompt CLI: GPT 4 > ASOPRS > Bard > Bard w/ prompt > GPT 4 w/ prompt SMOG: GPT 4 > ASOPRS > Bard > Bard w/ prompt > GPT 4 w/ prompt ARI: GPT 4 > ASOPRS > Bard > GPT 4 w/ prompt = Bard w/ prompt LWRS: ASOPRS > GPT 4 > GPT 4 w/ prompt > Bard > Bard w/ prompt |

| Kianian (1) 2023 | GPT 3.5 | Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease, Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, Gunning Fog Index and Simple measure of Gobbledygook | FKRE: GPT > online resources FKGL: GPT < online resources GFI: GPT < online resources SMOG: GPT < online resources |

| Kianian (2) 2023 | GPT 3.5, Bard | Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level | Prompt A: GPT < Bard Prompt B: GPT < Bard |

| Wu | ChatGPT | Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, Gunning Fog Index, SMOG index, Dale-Chall-Score | FKGL: ChatGPT > AAO GFI: ChatGPT > AAO SMOG: ChatGPT > AAO Dale-Chall-Score: ChatGPT > AAO |

| Study | LLMs | Evaluated Data | # of question / cases | Correct diagnosis |

| Raghu 2023 | GPT 4 | Clinical, biochemical and ocular data | 111 | GPT 4 diagnosis consistent with ophthalmologist in 75/111 cases with CST and 70/111 without CST |

| Liu 2024 | GPT 3.5 | FFA reports | 1226 | Ophthalmologists (89.35%) > Ophthalmologist interns (82.69%) > GPT 3.5-english prompts (80.05%) > ChatGPT 3.5-Chinese prompts (70.47%) |

| Lyons 2023 | GPT 4, Bing Chat, WebMD | History only | 44 | Ophthalmologists in training (95%) > GPT 4 (93%) > Bing Chat (77%) > WebMD (33%) |

| Zandi 2024 | GPT 4, Bard | History only | 80 | Correct diagnosis: GPT 4 (53.75%) > Bard (43.75%) Correct diagnosis somewhere in the conversation: GPT 4 (83.75%) > Bard (72.50%) |

| Shemer 2024 | GPT 3.5 | History only | 126 | Residents (75%) > Attendings (71%) > GPT 3.5 (54%) |

| Lim 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Bard | History only | 2 | GPT 4 (100%) = GPT 3.5 (100%) > Bard (50%) |

| Rojas-Carabali (1) 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4.0. Glass 1.0 | History and examination findings | 25 | Completely correct: Uveitis specialist (76% - 92%) > Fellow (76%) > GPT 4 (60%) = GPT 3.5 (60%) Partially correct: Uveitis specialist (4% - 12%) > Fellow (4%) > GPT 4(4%) = GPT 3 (4%) |

| Delsoz 2023 | GPT 3.5 | History and examination findings | 11 | 2 Ophthalmologist in training scored 72.7% 1 Ophthalmologist in training scored 54.5% GPT 3.5 scored 72.7% |

| Rojas-Carabali (2) 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | History, examination findings and Images | 6 | Experts (100%) > GPT 4 (50%) = GPT 3.5 (50%) > Glass 1.0 (33%) |

| Taloni 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | Question banks | 646 | GPT 4 (83.7%) > Humans (75.4% +/- 17.2%) > GPT 3.5 (68.1%) |

| Cai 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Bing Chat | Question banks | 250 | Humans (73.8%) > Bing (60.9%) > GPT 4 (59.4%) > GPT 3.5 (46.4%) |

| Study | LLMs | Management |

| Biswas 2023 | GPT 3.5 | Can myopia be treated? Median 4.0 (Good); IQR 3.0-4.0; Range 3.0-4.0 Who can treat myopia? Median 4.0 (Good); IQR 3.0-4.0; Range 3.0-4.0 Which is the single most successful treatment strategy for myopia? Median 4.0 (Good); IQR 3.0-4.0; Range 1.0-5.0 What happens if myopia is left untreated? 4.0 (Good); IQR 4.0-5.0; Range 3.0-5.0 |

| Lim 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Bard | GPT 3.5: Rating, n (%) Poor 5 (25), Borderline 7 (35), Good 8 (40) GPT 4.0: Rating, n (%) Poor 3 (15), Borderline 3 (15), Good 14 (70) Bard: Rating, n (%) Poor 3 (15), Borderline 8 (40), Good 9 (45) |

| Taloni 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | GPT 4 Medical Treatment 196 (83.4%); Surgery 106 (74.6%) Humans Medical Treatment 181 ±40 (76.9 ±16.9%); Surgery 106 ± 24 (74.7 ±17.2%) GPT 3.5 Medical Treatment 153 (65.1%); Surgery 81 (57.0%) |

| Al-Sharif 2024 | GPT 3.5, Bard | BARD: X^2 [3, N=25] = 28.0851, p<0.05 GPT 3.5: data not found (only in graph form) |

| Rojas-Carabali (2) 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | Complete agreement of management and treatment plans: 91.6% of cases Disagreement in 8.3% (1 case) |

| Cai 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Bing Chat | GPT 3.5: 58.3% GPT 4.0: 77.0% Bing: 75.4% Humans: 76.1% |

| Cappellani 2024 | GPT 3.5 | Overall Median Score for "How is X treated" = 1 (from Likert scale of -3 to 2) General 2; Anterior segment and cornea 2; Glaucoma -1; Neuro-Opth 2; Oncology 1; Paeds 1; Plastics 2; Retina and Uveitis 1 |

| Study | LLMs | Clinical Administration | Performance |

| Singh 2023 | GPT3.5 | Discharge Summary and Operative Notes Writing | (Qualitative) Discharge Summaries: Divided into different categories including patient details, diagnosis, clinical course, dis- charge instructions, and case summary. Noted to have valid but very general texts, that upon further prompting, was able to remove generalised texts and provide responses to a greater specificity and detail Operative Notes: Subdivided into categories including patient details, diagnosis, clinical course, discharge instructions, and case summary. Was noted to have levels of inaccuracies and hallucinations which were quickly corrected upon further prompting |

| Hua 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | Research Manuscript Writing | Mean helpfulness score: GPT4 > GPT3.5 Mean truthfulness score: GPT4 > GPT3.5 Main harmlessness score: GPT4 > GPT3.5 Modified AI-DISCERN score: GPT4 > GPT3.5 Mean hallucination rate: GPT3.5 > GPT4 Mean GPT-2 Output Detector Fake score: GPT3.5 > GPT4 Mean Sapling AI Detector Fake score: GPT3.5 > GPT4 |

| Ong 2023 | GPT 3.5 | Retinal ICD Scoring | Correct: 137/181 (70%) Correct only: 106/181 (59%) Incorrect: 54/181 (30%) |

| Study | LLMs | Evaluation | Results |

| Multiple LLMs | |||

| Tailor 2024 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Claude 2, Bing, Bard | Degree of inaccuracy or correctness with risk of harm | Yes, great significance: Bard > Bing > Claude > GPT 3.5 > Expert + AI > GPT 4 > Expert. No: GPT 4 > Expert > Expert + AI > GPT 3.5 > Claude > Bing > Bard |

| Al-Sharif 2024 | GPT 3.5, Bard | Degree of correctness | Contains both correct and incorrect or outdated: Bard > ChatGPT Contains completely incorrect Bard > ChatGPT |

| FerroDesideri 2023 | GPT 3.5, Bard, Bing Chat | Degree of correctness | Entirely incorrect or contained critical errors: Bard > Bing > GPT 3.5 |

| Yılmaz 2024 | GPT 3.5, Bard, Bing AI, AAO website | Degree of inaccuracy | Inaccuracy: AAO > Bing > Bard > ChatGPT |

| Barclay 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | Degree of inaccuracy | Incorrect facts, little significance: GPT 3.5 > GPT 4 Incorrect facts, great significance: GPT 3.5 > GPT 4 Omission of information, little significance: GPT 3.5 > GPT 4 Omission of information, great significance: GPT 3.5 > GPT 4 |

| Lim 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Bard | Degree of inaccuracy | Possible factual errors but unlikely to lead to harm: Bard > GPT > GPT 3.5 Inaccuracies that could significantly mislead patients or cause harm: GPT 3.5 = Bard > GPT |

| Pushpanathan 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Bard | Degree of inaccuracy | Inaccuracy: Bard > GPT 3.5 > GPT 4 |

| Lyons 2023 | GPT 4, Bing Chat, WebMD | Degree of inaccuracy | Grossly inaccurate statements: WebMD > Bing Chat > ChatGPT |

| Wilhelm 2023 | GPT 3.5 Turbo, Command-xlarge-nightly, Claude, Bloomz | Hallucination frequency | Hallucinations: Claude-instant-v1.0 > Command-xlarge-nightly > Bloomz > GPT 3.5 Turbo |

| Hua 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | Hallucination frequency | Hallucinations: GPT 3.5 > ChatGPT 4 |

| Cai 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Bing Chat | Hallucination frequency | Hallucinations: GPT 3.5 > Bing > GPT 4 |

| One LLM | |||

| Ali 2023 | GPT 3.5 | Degree of correctness | Partially correct: 35% Completely factually incorrect: 25% |

| Cappellani 2024 | GPT 3.5 | Degree of correctness | 27 / 120 graded as =< -1 (incorrect, varying degrees of harm) |

| Nikdel 2023 | GPT 4 | Degree of appropriateness | Inappropriate responses: Amblyopia: 5.6% Childhood myopia: 5.4% |

| Balas 2024 | GPT 4 | Degree of appropriateness | No inappropriate responses |

| Bernstein 2023 | GPT 3.5 | Degree of correctness or inappropriateness | Comparable with human answers (PR 0.92 95% CI [0.77 - 1.10]) |

| Biswas 2023 | GPT 3.5 | Degree of inaccuracy | Inaccurate: 3.6% Flawed: 1.8% |

| Potapenko 2023 | GPT 4 | Degree of inaccuracy | Relevant with inaccuracies: 5 / 100 |

| Liu 2024 | GPT 3.5 | Hallucination frequency | Hallucination: Step-Chinese > Step-English Misinformation: Step-Chinese > Step-English |

| Maywood 2024 | GPT 3.5 Turbo | Hallucination frequency | 12 responses are hallucinations |

| Study | LLMs | Potentially Harmful | Extent of Harm | Likelihood of harm |

| Bernstein 2023 | GPT 3.5 | - | Humans = Chatbots | Humans = Chatbots |

| Cappellani 2024 | GPT 3.5 | 9 / 120 responses graded as potentially dangerous 27 / 120 responses graded as =< -1 (incorrect, varying degrees of harm) |

- | - |

| Maywood 2024 | GPT 3.5 Turbo | 3 cases possible harm, 2 cases definitive harm | - | - |

| Wilhelm 2023 | GPT 3.5 Turbo, Command-xlarge-nightly, Claude, Bloomz | Potentially harmful: Claude-instant v1.0 > Bloomz > Command-xlarge-nightly GPT 3.5-turbo no potentially harmful piece |

- | - |

| Hua 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | Updated versions have higher harmlessness scores | - | - |

| Barclay 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | - | Incorrect facts, little significance: GPT 3.5 > GPT 4 Incorrect facts, great significance: GPT 3.5 > GPT 4 Omission of information, little significance: GPT 3.5 > GPT 4 Omission of information, great significance: GPT 3.5 > GPT 4 |

GPT 3.5 more likely than GPT 4 |

| Lim 2023 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Bard | Inaccuracies that could significantly mislead patients or cause harm: GPT 3.5 = Bard > GPT | - | - |

| Tailor 2024 | GPT 3.5, GPT 4, Claude 2, Bing, Bard | - | High risk harm: Bard > Bing > GPT 3.5 > Claude > GPT 4 > Expert + AI > Expert Low risk harm: Bard > Bing > Claude > Expert + AI > GPT 3.5 > GPT 4 > Expert |

High likelihood: Bard > Bing > Claude > GPT 3.5 > Expert + AI = Expert = GPT 4 Low likelihood: Expert > GPT 4 > Expert + AI > Claude > Bard > Bing |

| Potapenko 2023 | GPT 4 | 5/100 responses potentially harmful | - | - |

| Balas 2024 | GPT 4 | No responses constituting harm | - | - |

| Zandi 2024 | GPT 4, Bard | Bard potentially more harmful than GPT 4 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).