1. Introduction

Quantum field theory forms the theoretical framework of modern physics, with applications ranging from particle physics to condensed matter physics. However, calculations in quantum field theory, especially higher-order calculations in quantum electrodynamics (QED) and quantum chromodynamics (QCD), are known to face mathematical difficulties called ultraviolet divergences. [

1,

2,

3,

4] This divergence problem has traditionally been addressed through techniques such as introducing cutoffs, dimensional regularization, or renormalization theory, but these methods all involve mathematical operations whose physical meaning is not necessarily clear. [

5,

6]

In this research, we propose a new statistical mechanical approach to the divergence problem in quantum field theory. At its core is the possibility that the statistical properties of particles (whether fermionic or bosonic) may change depending on energy scale, and the introduction of a "transition function" to describe this change. Specifically, we hypothesize that at low energy regions, electrons are fermionic and photons are bosonic (consistent with conventional quantum field theory), but at high energy regions, conversely, electrons become bosonic and photons become fermionic, and we mathematically describe this statistical transition.

The most important feature of this approach is that it demonstrates the possibility that ultraviolet divergences, one of the mathematical difficulties in conventional quantum field theory, can be naturally suppressed by statistical transitions. The change in statistical properties in high-energy regions effectively suppresses the contribution of the high-momentum part of the integral, providing a physical mechanism to avoid divergences.

Why would such a statistical transition have physical meaning? From the perspective of statistical mechanics, the collective behavior of particles may be qualitatively different at low and high energies. For example, in condensed matter physics, it is known that in superconducting states, the formation of Cooper pairs causes electrons, which are inherently fermions, to effectively exhibit bosonic behavior. [

7,

8] Also, in finite-temperature field theory, thermal effects are studied to modify the statistical properties of particles. This research extends these analogies to high-energy physics, examining the possibility that at extremely high energy regions approaching the Planck scale, the statistical properties of particles themselves may change.

Specifically, this research will clarify the following points:

Theoretical framework of fermion-boson duality and mathematical formulation of transition functions

Extension of quantum electrodynamics with the introduction of boson-type gamma matrices

Proposal of a natural regularization method using transition functions and its numerical verification

Physical implications of the proposed approach and future prospects

Section 2 details the basic concepts of fermion-boson duality and the introduction of transition functions.

Section 3 outlines the extension of quantum electrodynamics using boson-type gamma matrices.

Section 4 applies the regularization method using transition functions to the specific calculation of electron self-energy and numerically verifies its effectiveness.

Section 5 discusses the physical implications of the proposed theory and future prospects, and presents conclusions.

This research is an attempt at the intersection of quantum field theory and statistical mechanics, aiming to provide a new solution from a statistical mechanical perspective to mathematical difficulties in high-energy physics. In particular, the concept of energy scale-dependent changes in statistical properties may bring new perspectives to understanding phase transition phenomena in complex systems physics.

2. Theoretical Framework of Fermion-Boson Duality

2.1. A New Understanding of Statistics: "Separation" of Spin and Statistics

One of the fundamental principles of quantum mechanics is the spin-statistics theorem, which links a particle’s spin and its statistical nature. According to this theorem, particles with half-integer spin (e.g.,

,

) are fermions, while particles with integer spin (e.g., 0, 1, 2) are bosons[

9]. This relationship has long been accepted as a fundamental framework in particle physics.

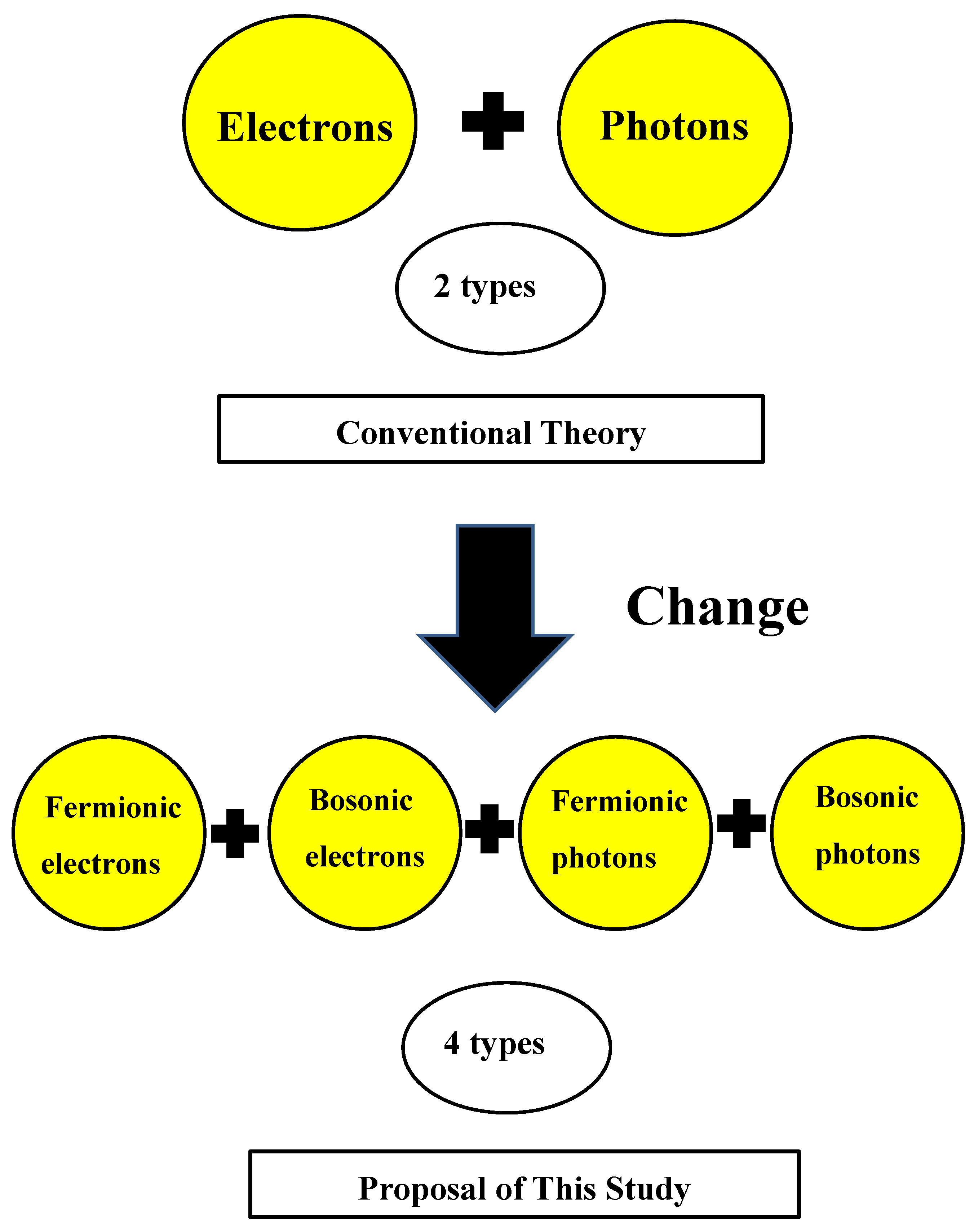

However, the fermion-boson duality theory proposed in this research considers the possibility that under certain conditions, the statistical properties of particles may "separate" from their intrinsic spin. According to this new perspective, particles can be interpreted as having the following four basic states:

Fermionic electron: Has spin and follows fermionic statistics

Fermionic photon: Has spin and follows fermionic statistics

Bosonic photon: Has spin 1 and follows bosonic statistics

Bosonic electron: Has spin 1 and follows bosonic statistics

In this theoretical framework, spin and statistics are treated as independent characteristics that can change depending on energy scale and physical conditions. In the low-energy limit, electrons behave as fermionic electrons and photons as bosonic photons, consistent with conventional quantum field theory. However, in the high-energy limit, electrons may transition to bosonic electrons, and photons to fermionic photons.

To formalize this concept, we introduce four basic state vectors for electrons and photons:

where:

: Fermionic electron state,

: Bosonic electron state,

: Fermionic photon state,

: Bosonic photon state.

This state, visualized, becomes

Figure 1.

Assuming correspondences for the four types of elementary particle states results in

Table 1.

The complete quantum state of each particle is expressed as an energy-dependent linear combination of these basic states:

Here, represents the transition function that determines the weight of each statistical component at a specific energy scale E.

2.2. Introduction and Definition of Transition Functions

Transition functions are the core mathematical tools of fermion-boson duality theory, quantifying how the statistical properties of particles transition with energy changes. From the perspective of statistical mechanics and symmetry, it is appropriate to define them as follows.

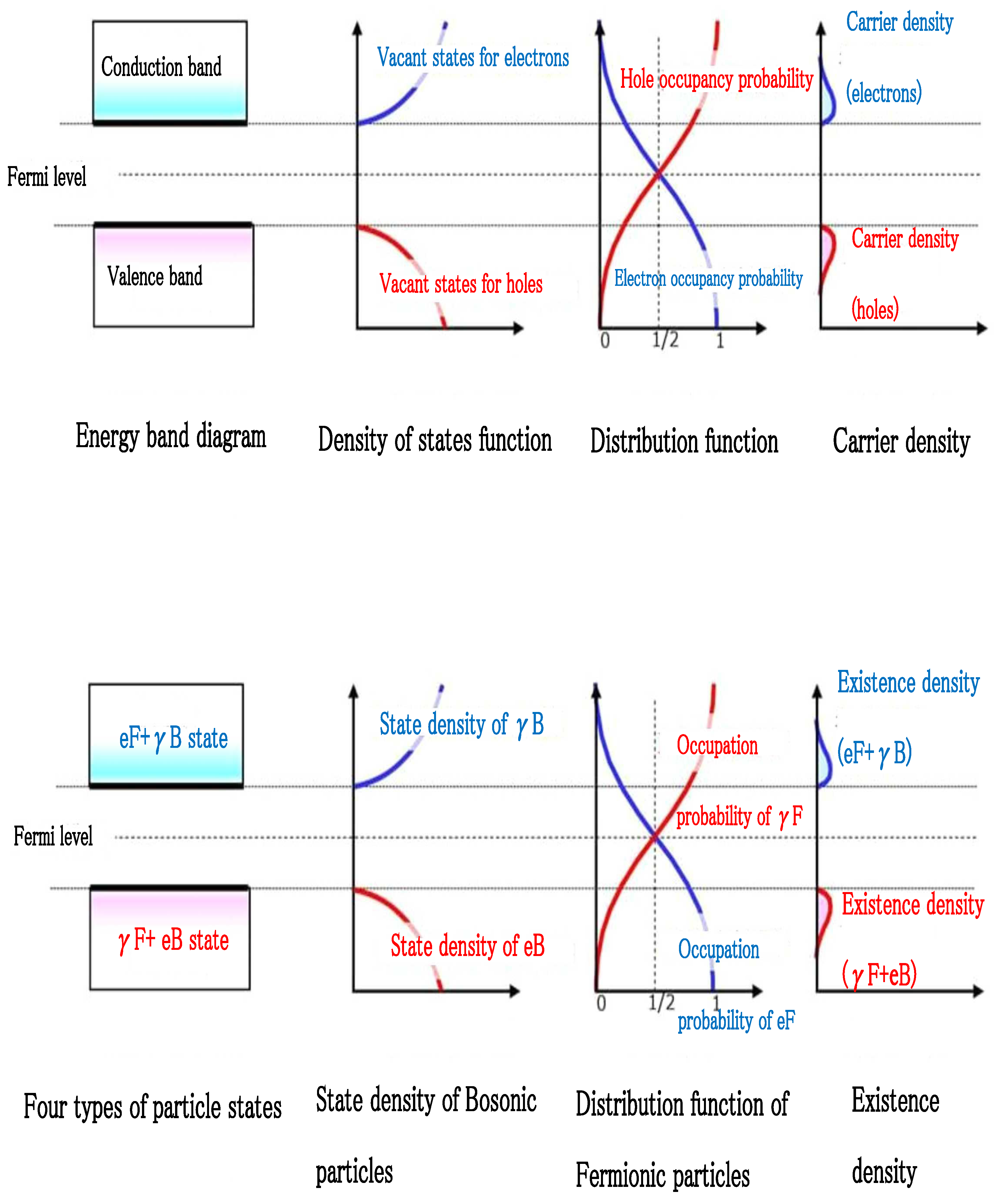

Figure 2.

Quadrant representation of transition functions. The right column shows fermionic components (, ), the left column shows bosonic components (, ). With increasing energy E, statistics invert, transitioning from photon (boson) to fermion, and from electron (fermion) to boson.

Figure 2.

Quadrant representation of transition functions. The right column shows fermionic components (, ), the left column shows bosonic components (, ). With increasing energy E, statistics invert, transitioning from photon (boson) to fermion, and from electron (fermion) to boson.

The parameters used here are as follows:

E: System energy (or a function of momentum).

: Characteristic energy at which statistical transition occurs (corresponding to chemical potential).

: Energy scale characterizing the sharpness of the transition.

Particularly noteworthy is that has a form similar to the Fermi distribution function. In this research, we interpret the transition function as a quantum mechanical extension of the Fermi distribution function in a single-particle system. This suggests a deep connection between statistical properties and thermal statistical mechanics.

The transition functions satisfy the following relations:

These equations ensure that the sum of fermionic and bosonic components always equals 1, describing the transition of statistics with energy change in a consistent manner.

2.2.1. Relationship between Transition Functions and the Hill–Wheeler Equation

The transition function

mentioned above has a sigmoid form similar to the ordinary Fermi–Dirac distribution function, and its equation is also known as the

Hill-Wheeler equation in the context of nuclear fission theory [

10,

11,

12]. Originally, it was a formula for calculating transmission probability when treating nuclear fission barriers with harmonic oscillator approximation [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], but

it can actually be reinterpreted as having a mathematical structure that serves as a “quantum mechanical Fermi distribution” [

20].

Looking at the form of

, for example,

it takes the form of a logistic function,

completely isomorphic to the ordinary Fermi–Dirac distribution .

1

We believe that this equation can be considered a "quantum mechanical extension of the Fermi distribution function"

applicable even to single-particle systems. For details, please refer to reference [

20].

In essence, by treating not merely as a nuclear fission barrier transmission coefficient, but as a "quantum statistical occupation probability" like the Fermi distribution in electrons, we can more naturally explain divergence suppression in nuclear fission and scale changes in statistics (energy scale dependence). In the numerical analysis below, it is suggested that viewing the Hill-Wheeler equation as a "quantum mechanical Fermi distribution" rather than a "barrier transmission rate" is useful.

2.3. Correspondence with Semiconductor Physics

In semiconductor physics, the description of electron states using Fermi-Dirac statistics is well-established, precisely explaining phenomena such as band gaps and carrier transport through statistical mechanics [

21].

In this research, we connect this framework to fermion-boson duality theory, suggesting that semiconductors function as concrete physical systems for this theory. Specifically, we propose the following correspondence between states in n-type and p-type semiconductors and transition functions:

Fermionic electron (): Occupation probability of electrons in n-type semiconductors.

Fermionic photon (): Occupation probability of holes in p-type semiconductors.

Bosonic photon (): Density of states function for electrons.

Bosonic electron (): Density of states function for holes.

As shown in

Figure 3, electrons and holes have a dual relationship with each other and follow Fermi-Dirac statistics, but their density of states functions can be interpreted as reflecting bosonic properties. For example, in regions where electron distribution density is high, the density of states of photons also increases proportionally, making this correspondence physically reasonable.

This figure visualizes the core of the theory, with the following important points:

The density of states of B-type (bosonic) elementary particles (second from bottom) corresponds to electron density distribution; since the density of states of photons is proportional to electron density, we believe there is no contradiction in this description.

The distribution function of F-type (fermionic) elementary particles (third from bottom) is key to preventing infinite divergence in vacuum polarization. As electrons transition from high-energy states to F-type photons, maintaining the balance of distributions, divergence is naturally suppressed.

Using this approach, it may be possible to construct equations that avoid infinity in vacuum polarization, electron self-energy, and vertex corrections without applying artificial regularization.

2.4. Boundary Conditions and Physical Meaning of Transition Functions

Transition functions have clear physical meanings depending on the energy region:

-

Low energy region ():

In this region, electrons behave as fermions and photons as bosons, reproducing the picture of conventional quantum electrodynamics.

-

High energy region ():

Here, statistics are inverted, with electrons showing bosonic properties and photons showing fermionic properties.

Transition region (): In this critical region, fermionic and bosonic components coexist, with the potential for new physical phenomena. Predictions for this region are particularly important for experimental verification of this theory.

Note that at , the bosonic transition functions and have mathematical singularities. However, in actual physical systems, E is rarely exactly equal to , and in numerical calculations, singularities can be avoided through appropriate regularization.

2.5. Examples in Condensed Matter Physics

This theory may seem to contradict the conventional spin-statistics theorem in quantum mechanics, but phenomena in condensed matter physics support its validity.

Superconducting state: Electrons form Cooper pairs and exhibit bosonic behavior. Cooper pairs in triplet states (spin 1) can be interpreted as "bosonic electrons," a concrete example of particles with spin 1 following boson statistics.

Meissner effect: Inside superconductors, photons acquire an effective mass and exhibit properties different from normal bosonic photons. In this theory, these can be interpreted as "fermionic photons."

Similarity to semiconductors: It is established that electrons and holes follow Fermi-Dirac statistics, but under certain conditions (such as in superconducting states), electrons form Cooper pairs and collectively exhibit bosonic behavior. Such energy-dependent changes in statistical properties may suggest a connection to fermion-boson duality theory.

These examples support the concept that energy scale-dependent changes in statistical properties, as proposed in this theory, are applicable not only to high-energy physics but also to condensed matter physics.

3. Boson-Type Gamma Matrices and Extended Quantum Electrodynamics

To incorporate the concept of fermion-boson duality introduced in the previous section into the framework of quantum field theory, an extension of the conventional Dirac equation is necessary. In this section, we introduce boson-type gamma matrices to realize this extension and construct an extended quantum electrodynamics Lagrangian based on them.

3.1. Introduction of Boson-Type Gamma Matrices

In this research, in addition to the conventional Dirac gamma matrices

, we introduce another representation

and define the following two operators:

These operators satisfy the following anti-commutation relations:

Here, represent spinor indices, and is the identity matrix. This algebraic structure gives rise to "half-Hermitian components" and "half-anti-Hermitian components" different from the conventional , yielding operators with different properties in the time and space directions.

The specific matrix representations of the bosonic gamma matrices are given as follows:

This matrix structure enables the description of particles incorporating both bosonic and fermionic properties.

For details of this calculation, please refer to the Mathematica code and calculation results available from the Zenodo repository provided in

Appendix B.

3.2. Extended Quantum Electrodynamics Lagrangian

Let us recall the four basic state vectors for electrons and photons introduced in the previous section:

Developing this state vector framework into quantum field theory, we can construct the following extended Lagrangian in quantum electrodynamics using gamma matrices

and bosonic gamma matrices

.

By introducing the operator that carries bosonic properties in addition to the Dirac operator in conventional QED, we can construct a framework where at low energies we have the usual fermionic electrons and bosonic photons, but at high energies, they transition to bosonic electrons and fermionic photons.

This Lagrangian reduces to normal quantum electrodynamics in the low-energy limit and has the characteristic of realizing statistical inversion inside atoms. Each term in this extended Lagrangian has the following physical meaning:

3.2.1. Fermion Kinetic Term:

Describes the fundamental interaction between fermionic electrons and fermionic photons

In low-density regions, the contribution from this fermionic photon term is small, and interaction with bosonic photons from term (3) is dominant

Written in a form that preserves Lorentz invariance and gauge symmetry

3.2.2. Boson Kinetic Term:

Describes the interaction between bosonic electrons and bosonic photons

Essentially includes a two-component structure

In phase transitions such as BCS-BEC crossover, understood as a change in contribution from term (1)

Manifests inside atoms or in high-pressure regions, providing new physical degrees of freedom

3.2.3. Photon Field Kinetic Term:

Describes the motion of photons in the normal state, representing the properties of transverse two-component bosonic photons

Becomes dominant in the low-energy region, ensuring consistency with classical electromagnetism

Describes the fundamental properties of photons while preserving gauge symmetry

3.2.4. Fermionic Photon Field Kinetic Term:

Inside atoms, the normal photon field kinetic term has duality with the fermionic

This energy-momentum tensor generates the metric tensor

Through this, a local gravitational field naturally arises inside atoms

In the low-energy region (), the transition functions , make the fermion kinetic term dominant, recovering the picture of conventional quantum electrodynamics. On the other hand, in the high-energy region (), , , making the boson kinetic term dominant. This realizes a physical picture where the statistical properties of particles change continuously depending on the energy scale.

A notable point is that this extended Lagrangian is a simple extension of conventional quantum electrodynamics and essentially preserves gauge invariance. That is, under the gauge transformation:

the Lagrangian remains invariant. This shows that the proposed extension satisfies the fundamental requirements of quantum field theory.

This extended theory enables a unified description of quantum electrodynamics and gravity. In particular, inside atoms:

1. Realization of duality between the photon field kinetic terms and

2. Natural emergence of the metric tensor through the energy-momentum tensor

3. Generation of a gravitational field through the curvature of spacetime

This is one of the important consequences of the fermion-boson duality proposed in this research.

4. Possibility of Automatic Avoidance of Ultraviolet Divergence: Natural Regularization Using Transition Functions

4.1. Vacuum Polarization

First, let’s briefly check the approach to vacuum polarization. In quantum electrodynamics (QED), the vacuum polarization correction is expressed as follows:

This integral diverges in the high-energy region. To suppress this, we introduce the transition function

and modify it as follows:

Here, is a function dependent on energy p, representing fermionic contribution at low energies () and bosonic contribution at high energies (), thus suppressing divergence. Based on this concept, we also apply it to electron self-energy and vertex corrections.

4.2. Electron Self-Energy

Electron self-energy represents the correction to the electron propagator. In conventional QED, it is given by:

This integral also diverges in the high-energy region. To suppress this, we apply transition functions to the electron and photon propagators.

(Fermionic at low energies, bosonic at high energies)

- Photon propagator:

Considering that photons, though bosons, may transition to "F-type photons" with fermionic properties in the high-energy region, we assume the following:

- : 1 (bosonic) at low energies, 0 (fermionic) at high energies

- : Provisional mass of F-type photons (could be 0 depending on the situation)

The modified self-energy is as follows:

In the high-energy region (), , , suggesting the possibility of convergence for the integral.

4.3. Vertex Correction

Vertex correction is the correction to the interaction vertex between electrons and photons. In conventional QED, it is expressed as:

This also diverges in the high-energy region. Modified with transition functions, it becomes:

- Electron propagators (two):

The modified vertex correction is:

In the high-energy region, the transition functions may suppress contributions, suggesting the possibility of convergence for the integral.

4.4. Transition Functions

Restating the transition functions and .

- Transition from fermion to boson:

- Transition from boson to fermion:

Here,

is the threshold energy for transition, and

represents the width of the transition. This allows for fermionic (or bosonic) properties at low energies, and the opposite properties at high energies.

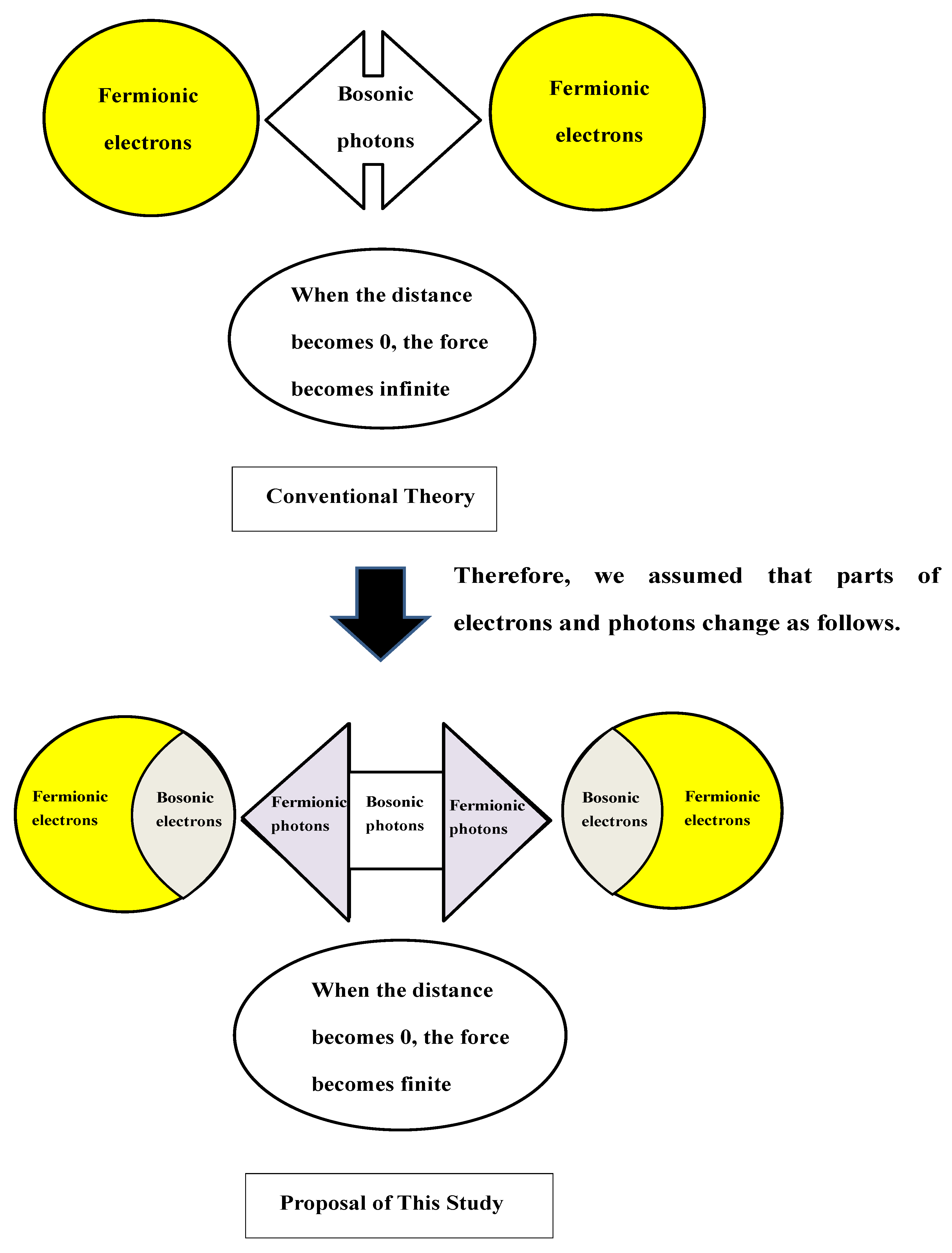

Using transition functions and , it becomes possible to formulate equations that suppress infinities in vacuum polarization, electron self-energy, and vertex corrections.

That is, in conventional theory, forces become infinite at distance 0, but in the proposal of this paper, they are finitely suppressed due to transition. Visualizing this image results in

Figure 4.

This approach utilizes the duality of fermions and bosons to provide a method for naturally resolving divergences without relying on conventional renormalization. Further verification of convergence can be achieved through numerical calculations.

4.5. Numerical Calculation Example of Electron Self-Energy Correction and Natural Regularization Using Transition Functions

For details of this calculation, please refer to the Mathematica code and calculation results available from the Zenodo repository provided in

Appendix B. Below is an overview of the numerical calculation results.

4.5.1. Explanation of MATHEMATICA Calculation Code and Its Numerical Results

Electron self-energy correction is a typical example of one-loop correction in quantum electrodynamics (QED), normally appearing as an integral that diverges in the high-energy region. In this research, we propose a method to naturally suppress this divergence by introducing a transition function based on fermion-boson duality theory.

Here, we consider a simplified four-dimensional Euclidean integral corresponding to electron self-energy. Specifically, for the radial component of momentum

k, we define the following integral:

where

Q is the external momentum scale,

m is the electron mass, and

is the integration upper limit. This equation corresponds to the case without transition functions, and since

m is very small (

), it shows a logarithmic divergence tendency in the high-energy region (

). In the actual numerical calculation, the following result was obtained:

On the other hand, by introducing the transition function

, we suppress contributions from the high-energy region. The integral using the modified integrand is as follows:

where the transition function is given by a logistic function:

is the threshold value for transition, and is a parameter representing the transition width. In this calculation, we adopted and .

With this modification, divergent contributions from the high-momentum (high-energy) region are effectively suppressed, and the integral value converges to a finite and very small value. The result of the numerical calculation is as follows:

Compared to the case without transition functions, the value with transition functions is about 22 orders of magnitude smaller, confirming that transition functions effectively suppress divergence. This result shows that self-energy corrections can be naturally finitized using transition functions without introducing cutoffs or renormalization, supporting the effectiveness of this theory.

4.6. Physical Interpretation of Transition Function Parameters

The parameters and appearing in the transition function are important physical quantities characterizing the scale at which statistical inversion occurs and the sharpness of the transition. Below, we discuss the physical interpretation of each parameter.

Characteristic energy : In the transition function , serves as the "threshold energy at which statistical transition occurs". In low-energy regions (), electrons maintain fermionic properties, and photons maintain bosonic properties, whereas when , electrons begin to transition to bosonic behavior, and photons to fermionic behavior. This can often be understood by analogy with the chemical potential. That is, from the perspective of serving as the boundary at which occupation numbers or energy levels change rapidly in the system, it plays a "-like" role. However, it does not strictly correspond to the chemical potential in thermodynamics, but approximately corresponds in terms of being a "threshold parameter."

Sharpness of transition : The denominator in the above equation is an important parameter that determines how rapidly the transition occurs. Numerically, the larger it is, the more gradual the transition, and the smaller it is, the steeper the transition. This form is similar to in the Fermi distribution function , and the "temperature" in thermodynamics can be considered to correspond to . Whether the occupation numbers (distributions) of electrons and photons in high-energy regions change rapidly or gently depends on this .

From the above interpretation, it is clear that represents the typical scale at which statistics transition, and represents the width (sharpness) of the transition. Therefore, if these two parameters can be determined through experimental or numerical approaches, "at which energy region and with what sharpness the statistics switch" can be quantitatively understood. This is a major feature of this theory and is key to explaining the mechanism of suppressing divergence in high-energy regions in a different way from conventional renormalization methods.

5. Conclusion and Outlook

In this research, from the perspective of fermion-boson duality theory, we introduced transition functions and proposed a new approach to naturally suppress ultraviolet divergences in quantum electrodynamics (QED). Specifically, under the assumption that the statistical properties of electrons (fermions) and photons (bosons) continuously invert with increasing energy scale, we constructed a framework in which "fermionic electrons transition to bosonic electrons at high energies, and bosonic photons transition to fermionic photons at high energies".

Suppression of ultraviolet divergence: By using transition functions, contributions from high-momentum (high-energy) regions are effectively cut off, and we demonstrated through numerical calculations that infinities appearing in conventional QED loop integrals converge to finite values. In the calculation of electron self-energy, we confirmed that while the absence of transition functions yields a very large value (essentially a divergence), their introduction results in a very small finite value.

Physical meaning and parameters: The parameters and in the transition function can be interpreted as parameters defining the "threshold (chemical potential)" and "sharpness of transition" of statistical transition, respectively. By appropriately choosing these values, fermionic electrons and bosonic photons predominate in the low-energy region as usual, while bosonic electrons and fermionic photons manifest in high-energy regions.

Relationships with other fields and future prospects: There is a structural similarity between "fermion-boson transformation" phenomena in condensed matter such as semiconductors and superconductors, and the statistical inversion at high energies suggested by this theory. [

22] This suggests that this approach may extend beyond high-energy physics to a wide range of physical domains. In the future, attempts to fit transition function parameters from early universe conditions or ultra-high-energy cosmic ray data to experimentally estimate the energy scale at which the "spin-statistics" relationship breaks down are also expected.

As described above, this research has presented a way to avoid ultraviolet divergences in quantum field theory through a "statistical mechanical approach." A characteristic feature is that it gives physical (statistical) meaning to what conventional renormalization theory treated as "mathematical operations." In the future, it will be important to increase the application examples of transition functions in other scattering processes and multi-particle interaction systems, and to evaluate the effectiveness and versatility of this theory by examining consistency with experiments and observations. Additionally, further theoretical developments and challenges remain, such as connections to quantum gravity theory and extensions to non-Abelian gauge theories including QCD, and future research developments are greatly anticipated.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

In conducting this research, email discussions with university professors and associate professors specializing in particle physics had a decisive influence on the conception of fermion-boson duality, which forms the core of this paper. I deeply appreciate the many insights gained through profound discussions with both professors regarding the mathematical structure and physical meaning of the theory. I would also like to thank ChatGPT o1, Grok3, and Claude 3.7 Sonnet for their assistance with translation and editing in compiling and presenting the research results.

Appendix A Verification of the Establishment of 2D Lorentz Transformation

The attached MATHEMATICA program (omega_matrix_properties.nb) demonstrates that the 2D Lorentz transformation is established through the properties of the matrices. In this section, we verify that Lorentz invariance is maintained using the definition of the matrices and their anti-commutation relations.

Appendix A.1. Definition of ω Matrices

Using the standard 4×4 gamma matrices

, we define the boson-type gamma matrices

as follows:

Specifically,

and

are represented by the following matrices:

Appendix A.2. Verification of 2D Lorentz Transformation

The 2D Lorentz transformation considers the time direction (

) and one spatial direction (

). In this research, we demonstrate that Lorentz invariance is maintained using the anti-commutation relations of

and

. The anti-commutation relations are calculated as follows:

These relations satisfy the following condition for the Minkowski metric

:

This condition ensures that the form of the Dirac equation is invariant under the 2D Lorentz transformation , (where ).

Appendix A.3. Consistency of the Extended QED Lagrangian

From the above anti-commutation relations, we see that the

matrices behave appropriately under 2D Lorentz transformations. In particular,

,

,

reflect the different statistical properties of the time and space directions while maintaining Lorentz invariance. This confirms that the proposed extended QED Lagrangian:

has physical consistency in 2D spacetime. Additional verifications in the note (e.g., ) also support the same invariance.

Furthermore, defining an invariant

s of the electromagnetic field

using

:

it is invariant under 2D (x-axis, y-axis) Lorentz transformations. This result shows that the third term (bosonic electron) and fourth term (bosonic photon) in equation (

A6) maintain invariance under 2D Lorentz transformations.

Appendix B Attached MATHEMATICA Programs

The Mathematica code and calculation results (PDF files) used in this research are available from the following repository:

Below is a brief explanation of the computational contents of the two MATHEMATICA programs included in the repository.

ElectronSelfEnergy_Regularization.nb

This program implements a toy model that calculates electron self-energy in a simplified 4D Euclidean space. It verifies a method to suppress divergence in the high-energy region using the transition function . Specifically, it performs integration up to for momentum k and obtains the following results:

The introduction of the transition function suppresses contributions from the high-momentum region, demonstrating that finite values can be obtained without renormalization.

omega_matrix_properties.nb

This program defines the standard 4×4 gamma matrices () and verifies their properties. It is used for verifying the 2D Lorentz transformation in the extended QED of this research. Specifically, it explicitly describes and attempts to confirm the anti-commutation relations by calculating products such as . This provides the foundation for supporting the possibility of introducing boson-type gamma matrices .

References

- Peskin, M.E.; Schroeder, D.V. An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory; Addison-Wesley, 1995.

- Weinberg, S. The Quantum Theory of Fields I, II; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura, Y. Relativistic Quantum Mechanics; Shokabo: Tokyo, Japan, 2012; (in Japanese). ISBN 4785325100. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, M. Quantum Field Theory (II); Shokabo: Tokyo, Japan, 2020; (in Japanese). ISBN 4785325127. [Google Scholar]

- ’t Hooft, G.; Veltman, M. Diagrammar. CERN Report No. 73-9, 1973.

- Bogoliubov, N.N.; Shirkov, D.V. Introduction to the Theory of Quantized Fields; Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L.N.; Schrieffer, J.R. Theory of Superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 1957, 108, 1175–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzburg, V.L.; Landau, L.D. On the Theory of Superconductivity. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 1950, 20, 1064–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Pauli, W. The Connection between Spin and Statistics. Phys. Rev. 1940, 58, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.L.; Wheeler, J.A. Nuclear Constitution and the Interpretation of Fission Phenomena. Phys. Rev. 1953, 89, 1102–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Quantum Mechanics: Non-Relativistic Theory; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1977; Volume 3, pp. 213–215. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, R.R.; Nigam, B.P. Nuclear Physics: Theory and Experiment; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1967; pp. 206–208. [Google Scholar]

- Ragnarsson, I.; Nilsson, S.G. Shapes and Shells in Nuclear Structure; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 160–177. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, A.; Ohta, M.; Mizuno, T. Production of Stable Isotopes by Selective Channel Photofission of Pd. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 40, 7031–7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, M.; Matsunaka, M.; Takahashi, A. Analysis of 235U Fission by Selective Channel Scission Model. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 40, 7047–7051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, M.; Takahashi, A. Analysis of Incident Neutron Energy Dependence of Fission Product Yields for 235U by the Selective Channel Scission Model. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 42, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, M.; Nakamura, S. Channel-Dependent Fission Barriers of n+235U Analyzed Using Selective Channel Scission Model. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 45, 6431–6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, M.; Nakamura, S. Simple Estimation of Fission Yields with Selective Channel Scission Model. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2007, 44, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, M. Influence of Deformation on Fission Yield in Selective Channel Scission Model. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2009, 46, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, H. Application of the Hill-Wheeler Formula in Statistical Models of Nuclear Fission: A Statistical-Mechanical Approach Based on Similarities with Semiconductor Physics. Entropy 2025, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sueyasu, T. Introduction to Optical Devices; Corona Publishing Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; pp. 139–142. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Goldenfeld, N. Lectures on Phase Transitions and the Renormalization Group; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

| 1 |

The actual Hill-Wheeler equation is given as , but by rewriting , it can be organized as a logistic function. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).