1. Introduction

Accurately estimating the aboveground biomass (AGB) is still difficult. One can estimate AGB using a destructive method (harvesting) or nondestructive. The destructive approach, which involves felling trees and weighing their components, is an exact way to calculate biomass [

1]. Unfortunately, it is costly, labor-intensive, often unlawful, impractical for large-scale study, and frequently not ecologically friendly. The destructive approach's drawbacks are addressed by a nondestructive method that makes use of tree biophysical parameters, particularly tree height and diameter at breast height (DBH), which are widely employed as inputs for large-scale AGB and carbon stock assessment using allometric models [

2,

3]. Therefore, accurate estimation of AGB necessitates accurate measurement of tree height and diameter, particularly in the case of mature trees [

4]. AGB is calculated by multiplying the projected tree volume by that specific tree species' fundamental wood density parameters [

5]. Unlike the allometric biomass model, which depends solely on a limited number of tree structural factor values, this approach uses an actual biological morphological structure model of a specific tree species to estimate the tree AGB. Because of this, the estimation of AGB has significantly benefited from the recent rapid development of remote sensing technology and applications. A different method for efficiently and precisely estimating the AGB is provided by applying sophisticated technologies in forestry. There are several benefits to using satellite remote sensing technologies for mapping and evaluating large-scale, multitemporal forest biomass and carbon stocks. However, it is not relevant or reliable for evaluating forest AGB at the stand and individual tree levels [

6]. In the past decade, there has been a significant advancement in light detection and ranging (LiDAR) technology, particularly in its application to forest inventory [

7]. Aerial and terrestrial LIDAR has been applied to nondestructively, rapidly, and effectively quantify AGB. The upper canopy is the focus of airborne LIDAR because of its top-down perspective, while ground-based laser scanning faced difficulties in measuring canopy height, as tall trees and densely interlocking crowns hindered the instrument's effectiveness [

8]. On the other hand, terrestrial LIDAR returns usually concentrate on the lower canopy, and evaluating the upper crown structure and tree heights is challenging [

9].

Airborne laser scanning (ALS), terrestrial laser scanning (TLS), and mobile laser scanning (MLS) are the three main types of LiDAR [

8]. Ground-based sensors, particularly TLS, have recently drawn much interest in forest inventories [

10]. This technology can produce accurate and high spatial resolution three-dimensional (3D) point cloud data. As a result, it has been extensively used in forestry surveys to estimate AGB and carbon storage and gather fundamental tree characteristics [

11]. However, automatically generated photogrammetric point clouds obtained from ALS are becoming more popular in forestry due to advances in sensors and image processing techniques [

12]. These include methods for measuring large canopies to estimate forest structure and deep learning algorithms to extract tree crowns and identify tree species [

13]. Mobile laser scanners (MLS) in forest environments face many challenges, the foremost of which is locating the position and movement of the scanner, given poor global navigation satellite system (GNSS) coverage under the canopy. Using simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) techniques is one possible way to address the localization issue in the forest [

14]. Using handheld and TLS data to estimate the total aboveground biomass of individual trees were better results than those obtained using backpack laser scanning data due to its performance limitation in extracting tree point clouds within a certain distance above the ground and the point clouds of backpack laser scanning become sparser, leading to poorer display results and inaccurate display of details [

15]. Nonetheless, TLS encounters several challenges in its operational use; carrying, mounting, and collecting data in the forest takes time and labor; processing the data in the office requires a lot of computation and time; and there are severe issues with non-detection of trees if multiple scans are not carried out and stitched together [

10]. The main objectives of this study include (I) a comparison of the accuracy of a single tree-level conventional field measurement with ALS and orthophoto and (II) a comparison of AGB and carbon stock estimated from remotely sensed data and traditional field-based methods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

The study area was Mae Jang plantation, Lam Pang province, northern Thailand (18.26655 N, 99.75982 E). The long-term averages of temperatures are between 14–36 °C. Elevation within the study area ranges from 300–700 m a.s.l. The area has an annual average precipitation of 1,055 mm, with higher precipitation from May to October [

16]. The plot's topography featured a mix of gentle slopes, with gradients less than 45 degrees (TF plots) and steep slopes exceeding 45 degrees (TS plots). Data was acquired in 17–18-year-old Teak (

Tectona grandis) planted with 4 m × 4 m spacing. The individual tree measurements were completed for 12 plots randomly selected through the study area. Each plot has a square shape of 40 m on each side and covers a total area of 1,600 sq.m. The plot density is lesser than the initial due to natural mortality and wildfire, creating a sunlight penetration. This results in dense shrubs, tall grasses, and bamboo clumps.

2.2. Data Investigation

Two primary methods were employed to estimate aboveground biomass (AGB): (i) field-based observations utilizing allometric equations and (ii) remote sensing techniques, including airborne laser scanning (ALS) with RGB and LiDAR sensors. Following a systematic plot-based approach, tree positions were recorded using a real-time kinematic (RTK) GPS. GPS static measurements were conducted in open areas, typically at the periphery of the study plot, to enhance positional accuracy. Diameter at breast height (DBH) was measured using a diameter tape at a standardized height of 1.3 meters above ground level. Total tree height was recorded using a laser-based hypsometer (Haglöf Vertex 5 Hypsometer). The ALS data were acquired concurrently with field data collection using a DJI Matrice 300 drone equipped with a CHC Alpha Air 10 LiDAR system, an integrated 45 MP orthographic camera, and a global navigation satellite system (GNSS). The LiDAR system operated at a scan rate of 500,000 points per second, achieving an absolute positional accuracy of 2–5 cm in horizontal and vertical dimensions at a flight altitude of 700–1,000 meters and a scan angle of 60° [

17]. The resulting LiDAR point cloud had a density of 5–6 points per square meter. A 1-meter resolution cell size was used to generate the canopy height model (CHM) from the ALS point cloud data and orthophotos.

Digital surface models (DSM) and digital terrain models (DTM) were derived from the first and last LiDAR returns, respectively, using QGIS 3.34 Prizren. The CHM was subsequently generated by subtracting the DTM from the DSM using a raster calculator in ArcGIS. The initial CHM exhibited pits and gaps due to LiDAR beam penetration through branches before registering the first return [

18]. According to [

11], point cloud processing involves filtering, extracting individual trees, and deriving structural parameters from point cloud data. Model reconstruction and algorithmic optimization were performed using the quantitative structure model (QSM) reconstruction method for individual trees. The methodological framework developed in this study provides a robust approach for estimating AGB and carbon sequestration based on ALS-derived point cloud data [

19]. A CHM is a digital representation of tree canopy heights across a landscape, typically generated by subtracting ground elevation from vegetation height data obtained via ALS [

20,

21,

22]. CHM segmentation involves applying computational algorithms to detect and delineate individual trees or clusters. This process identifies CHM peaks corresponding to tree tops, followed by boundary delineation to represent individual tree canopies [

23,

24]. Various segmentation techniques, such as watershed segmentation and region-growing algorithms, were employed to enhance tree identification accuracy [

25]. The segmentation algorithm requires user-defined control parameters to optimize the quality of the segmentation outcome [

26]. For each delineated canopy projection area (CPA), the highest local value within the CHM was identified and recorded as the tree height.

An accuracy assessment was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of ALS-derived LiDAR data in tree detection, following the methodologies outlined by [

8]. The relationship between DBH and tree height served as the basis for calculating individual tree AGB, utilizing a localized allometric equation developed by Na Takuathung et al. (in press) from a dataset of 25 felled sample trees. Carbon content was estimated based on species-specific carbon concentrations for teak (

Tectona grandis), as reported by [

27]: 45.43% for leaves, 46.78% for branches, and 47.20% for stems. Finally, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess statistically significant differences between measurements obtained from remote sensing and traditional field-based methods. The RMSE and Bias were calculated to explain the deviation between these variables' measured and predicted values.

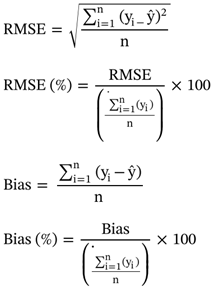

Where RMSE-Root Mean Square Error; yi-Measured value of the dependent variable; ŷ-Predicted value of the dependent variable; n- Number of observations.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Tree Count Extraction from ALS and Field-Based Methods

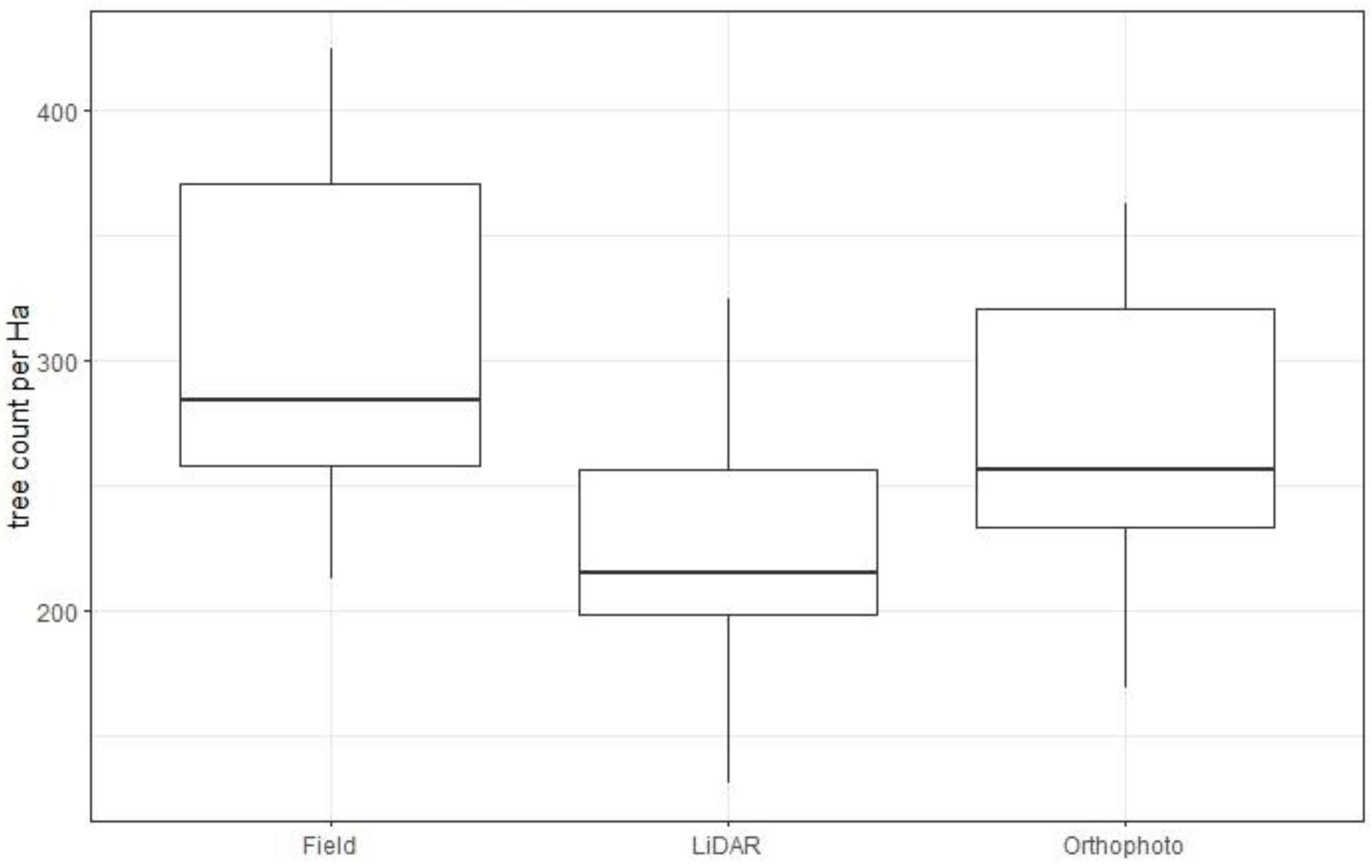

From

Table 1, the individual tree detection rates vary significantly between sample plots, with extraction percentages ranging from 61.76 to 100%. The orthophoto extraction achieved an overall detection rate of 87.16%, while ALS achieved a slightly lower rate of 73.31% (

Figure 1). The RMSE indicates that ALS has a more significant error magnitude (27.73%) than orthophoto (15.27%). The negative BIAS values show that orthophoto and ALS were underestimated compared to the field values, with ALS underestimating more significantly (-26.36%) than orthophoto (-12.48%).

3.2. Total Tree Height Measurement and Accuracy Assessment

Based on data from 25 felled sample trees, tree height extracted from ALS yielded the lowest RMSE, averaging 0.568 m. In comparison, tree heights derived from orthophoto extraction and field measurements showed higher RMSE values of 5.835 m and 1.2184 m, respectively. Linear regression analysis further indicated a high R

2 of 0.88 for ALS data, with the regression line closely aligning with the one-to-one reference line (

Figure 2). Conversely, tree height measurements from orthophoto extraction exhibited the lowest R

2 and the highest RMSE, indicating lower accuracy.

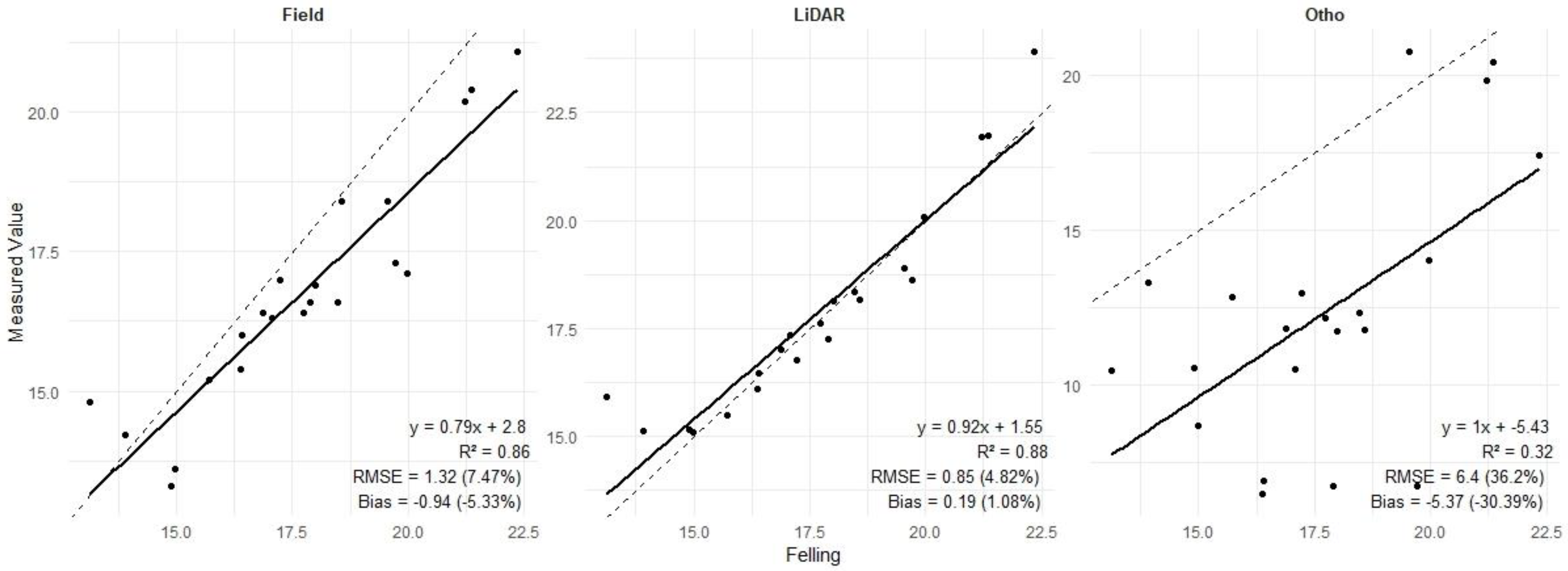

Data from 25 felling trees showed the relationship between height and DBH of felled sample trees (

Figure 3) with a high correlation R

2 of 0.79. The linear regression model showed as follows;

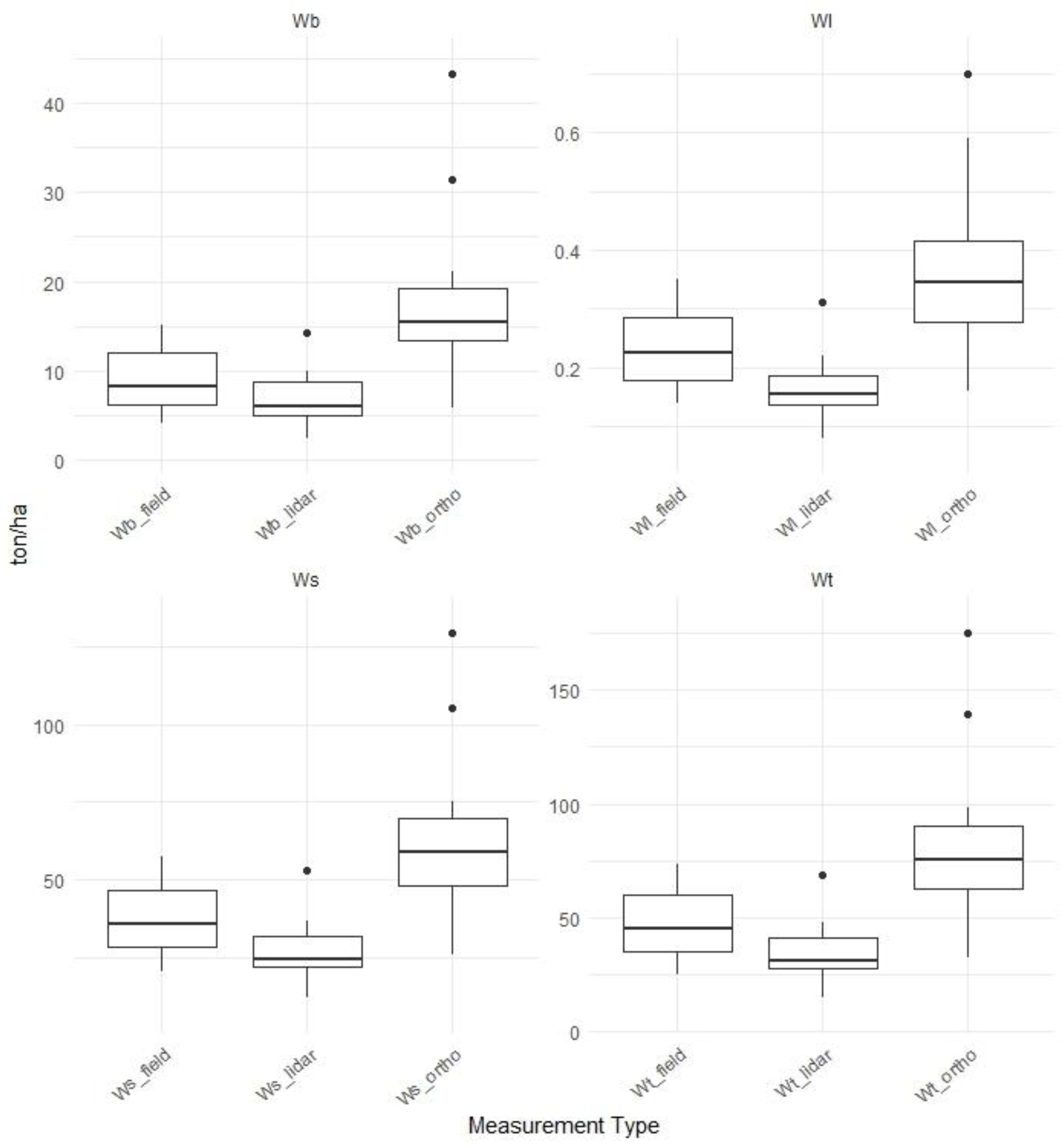

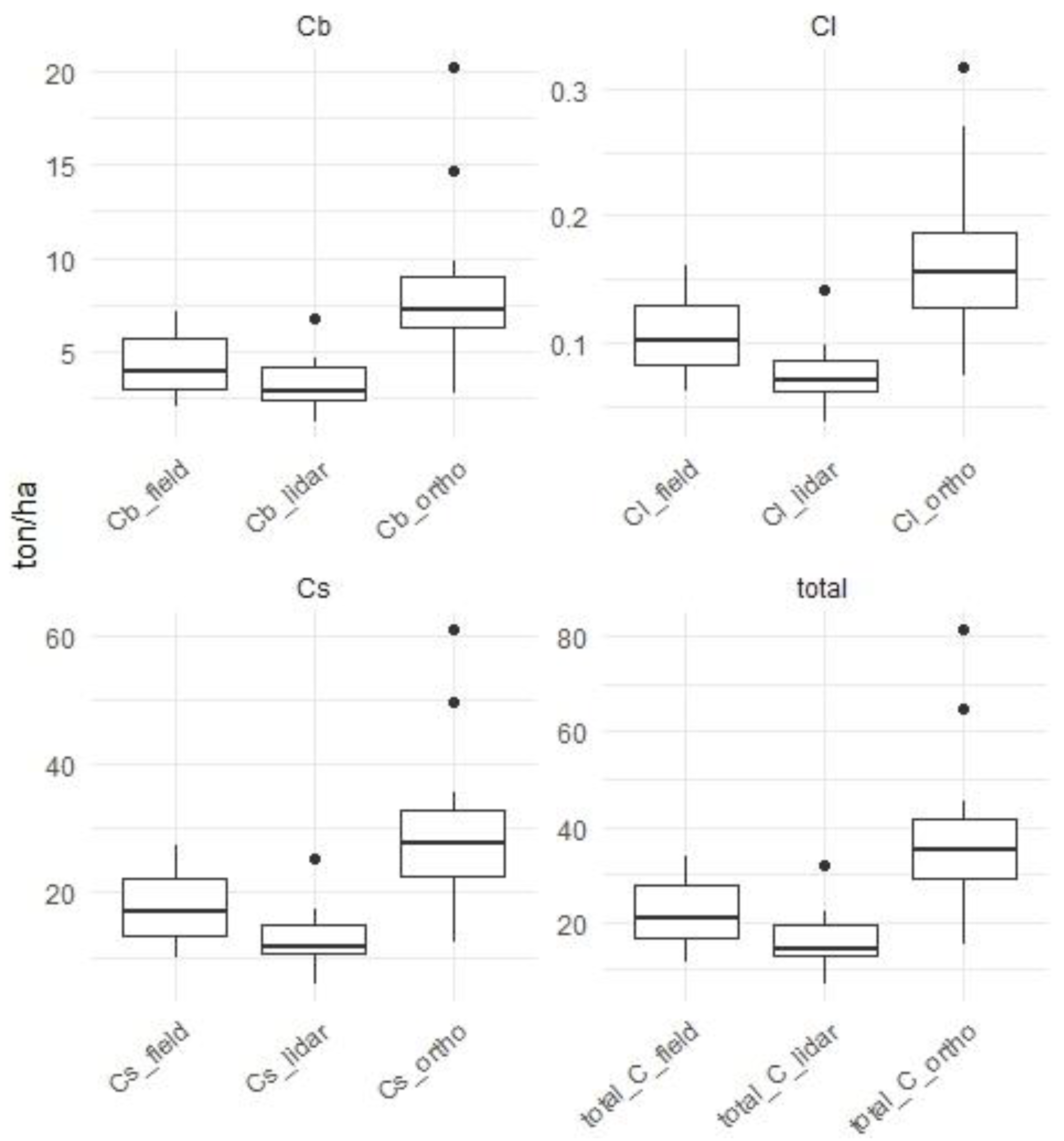

3.3. Plot Level AGB and Carbon Sequestration Extracted from Filed-Based and UAV Data Sources

The number of trees per hectare varies considerably across field-based, ALS, and orthophoto datasets.

Figure 4 shows that field-measured biomass data is the baseline for validating remote sensing methods. Field measurements typically capture the most accurate data due to direct observations, although they are labor-intensive and time-consuming, especially in dense plots. ALS-derived biomass values are generally lower than field measurements in most plots. For example, in plot T1F1, the total biomass estimated by ALS is 67.95 t ha

−1, compared to the field measurement of 72.22 t ha

−1.

Field data provides the most direct measurement of carbon in biomass, giving total carbon values for each component (stem, branches, leaves) with high reliability. For example, plot T1F1 shows a total field carbon of 34.02 t ha

−1, while the corresponding ALS and orthophoto estimates are 32.00 t ha

−1 and 38.45 t ha

−1, respectively. LiDAR data consistently shows slightly lower carbon values than field measurements in most plots. This underestimation by LiDAR could be due to the limitations in detecting underlying trees. Orthophoto estimates vary significantly, sometimes exceeding field measurements, especially for more significant biomass components. For example, plot T2F1 shows a total orthophoto carbon of 64.75 t ha

−1 compared to 26.70 t ha

−1 in field measurements.

Figure 5 shows stem carbon storage (Cs), often trees' most significant carbon pool. ALS and orthophoto estimate higher stem carbon in the flat area than in the slope area due to better soil conditions and water availability, promoting more robust stem growth, which can affect biomass accumulation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of Tree Count Extraction from ALS and Field-Based Methods

From our results, tree detection varies significantly between sample plots. This variability can be attributed to differences in canopy density, tree spacing, and structural characteristics of the forest in each plot. For instance, areas with dense or overlapping canopies may pose challenges for ALS by obscuring individual tree crowns, leading to undercounting. Conversely, open or evenly spaced tree arrangements, often found in managed forests or young plantations, facilitate higher detection rates [

28,

29]. The orthophotos likely benefited from their high spatial resolution and ability to distinguish tree crowns in clear weather conditions [

30]. Orthophotos, being image-based, capture detailed visual information and can often provide more precise representations of canopy structure at finer scales. However, orthophoto limitations arise in complex canopies where 3D depth information is required for accurate delineation, and this is where ALS traditionally excels by offering detailed vertical structure data [

31]. LiDAR's lower overall detection rate may result from difficulty detecting smaller or understory trees and potential algorithm limitations in distinguishing individual crowns in overlapping canopies [

32]. LiDAR data can also be sensitive to the sensor's resolution and scan angle, which may affect tree count accuracy depending on the forest structure and the sensor setup used. ALS appears advantageous for individual tree detection in less complex structures and offers essential height and structural data that can improve biomass and carbon stock estimates, even if individual detection rates are lower [

33,

34]. Improvements could involve combining ALS data with orthophoto imagery and leveraging the high spatial resolution of orthophotos with the vertical structural insights of LiDAR. This fusion approach, increasingly adopted in forestry, allows for more accurate tree counting and height measurements by utilizing complementary data from both sources [

35,

36].

4.2. Total Tree Height Measurement and Accuracy Assessment

ALS has consistently demonstrated high accuracy in estimating tree heights because it can penetrate canopy layers and provide precise 3D structural data [

37]. ALS data shows its robustness in height estimation, especially compared to orthophoto and field measurements. Similar results have been documented in studies where LiDAR outperforms photogrammetric methods, particularly when measuring complex canopy structures and densely forested areas [

32,

38]. This result is comparable to [

39], which revealed that LiDAR-derived tree height values for certain species overestimate the measurements by approximately 0.40 meters (~5% of the average height) compared to field measurements. This discrepancy can be attributed to the complex terrain and the obstruction caused by leaves and foliage at the tree tops. Low bushes were present in the research area and may bear on the acquisition of tree height from the point cloud data of the trees, but [

11] reported that affected DBH. In contrast, orthophoto height extraction highlights its limitations for accurate tree height estimation. Orthophotos are generally less effective for height measurements due to their reliance on 2D imaging, which lacks the depth information that LiDAR provides [

2]. Errors in height estimation from orthophotos are widespread in dense forest settings, where occlusions and shadows can lead to significant inaccuracies [

30]. Traditionally, reliable field height measurements yielded an intermediate error and bias in this analysis. This is consistent with findings that field-based measurements, though accurate, are labor-intensive and can be subject to human error, particularly in large-scale forest assessments [

40]. Field measurements also have limitations in canopy-level assessments compared to LiDAR, which provides comprehensive, non-intrusive measurements across extensive areas. The high R

2 value from the ALS dataset in the regression analysis underscores the strong correlation between ALS-derived heights and actual tree height, demonstrating its suitability for regression-based forest modeling. Studies have shown that ALS-derived tree metrics correlate highly with field measurements, often achieving R

2 values exceeding 0.80, especially in uniform [

33,

34].

The high correlation between DBH and total height in felled sample trees indicates a strong linear relationship. This suggests that tree height can be reliably used as a predictor for DBH in this particular Teak plantation and aligns with forestry research that shows height and DBH are commonly correlated [

41,

42]. This level of correlation is often seen in single-species, even-aged stands where competition, soil quality, and climatic conditions lead to consistent growth patterns across trees [

43]. This high predictive accuracy benefits forest management by enabling efficient and less invasive DBH estimation, especially in large forested areas where direct measurement is challenging [

44]. Studies in forest biometrics have found that height and DBH relationships can vary significantly across species and ecological regions. For instance, in mixed-species forests, DBH may show weaker correlations with height due to species-specific growth patterns [

45]. Therefore, the strong correlation observed here may primarily apply to the specific forest type and species composition studied, highlighting the importance of context-specific models. This model could also facilitate applications in remote sensing when the tree height is obtained from UAV data sources. DBH can be estimated using this model, enhancing biomass and carbon stock estimates without needing ground measurements. Such applications are increasingly valuable in monitoring forest biomass and carbon sequestration efforts [

37,

46].

4.3. Plot Level AGB and Carbon Sequestration Extracted from Filed-Based and UAV Data Sources

The ALS and orthophoto often undercount trees compared to field data, which could result in difficulty detecting small trees or trees in dense clusters [

29] because LiDAR's dependence on laser returns for height data may result in trees being missed if their signals are absorbed or blocked by larger, overstory trees [

35]. Orthophotos frequently show higher tree counts than ALS and are closer to field data in some plots. However, orthophoto data sources may include non-tree elements in densely vegetated plots and artificially inflating tree counts. This can explain the discrepancies in biomass when orthophoto-derived counts are higher but have limited height data. ALS-derived biomass values are generally lower than field measurements in most plots. This underestimation might stem from the limitations of LiDAR in penetrating dense canopy layers or detecting small understory trees, which are often included in field biomass totals [

28,

34]. Meanwhile, orthophoto-derived biomass values are typically higher than field and ALS values. Orthophoto techniques, which rely on high-resolution images, might overestimate biomass due to difficulty differentiating tree height and canopy depth without 3D information [

30]. LiDAR generally provides better height and structural data, making it helpful in estimating biomass when combined with accurate height-to-biomass models [

36]. However, LiDAR's limitations in understory detection lead to potential underestimation of total biomass. Orthophotos, on the other hand, may overestimate biomass by failing to distinguish tree crowns accurately in overlapping canopies. The lack of 3D structural information makes orthophoto-based biomass estimation prone to errors, especially in dense or mixed-forest settings [

33]. [

47] revealed to limitations in orthophoto resolution, which could lead to overestimation of biomass for more giant trees or areas with dense canopy. Orthophoto analysis is also sensitive to light and shadow effects, which can influence the accuracy of carbon estimation.

The observation that slope terrain can lead to lower biomass accumulation and reduced carbon storage in trees is because environmental stressors associated with slopes, such as limited soil depth, water drainage issues, and increased soil erosion, can negatively impact tree growth. These factors collectively restrict root expansion and nutrient availability, leading to slower growth rates and smaller biomass production [

48]. Field-based measurements provide detailed and accurate estimates for each carbon pool, which are essential for understanding the sequestration potential of teak plantations [

49]. However, field measurements are resource-intensive. Remote sensing techniques like

ALS and

orthophotos offer scalable alternatives that can complement field data because they can capture 3D forest structures, allowing for accurate modeling of tree height and biomass distribution [

50].

Orthophotos provide 2D imagery useful for assessing canopy cover and distribution and can serve as a proxy for broad carbon estimates across large plantations. While not as precise as LiDAR for estimating branch and leaf carbon, orthophotos can be calibrated against field data to estimate carbon at a landscape scale, making it feasible for large-scale monitoring [

51].

Teak (

Tectona grandis) plantations are increasingly recognized for their carbon sequestration potential, especially in dense and long-living stems. Teak trees are known for their high wood density, allowing them to store significant carbon over their lifespan [

52]. The carbon stored in the stem is critical for long-term sequestration because it represents a stable carbon pool that, if harvested sustainably, can remain stored in durable wood products for decades. This capacity for long-term carbon sequestration makes teak valuable for climate change mitigation strategies, as it helps offset anthropogenic CO₂ emissions [

53]. Branches, though more minor in biomass, provide additional carbon storage and contribute to the overall structure of the canopy, which influences the forest microclimate and soil carbon dynamics. The carbon in branches becomes particularly relevant when trees are managed with selective pruning, which can enhance or reduce carbon sequestration depending on branch removal [

54]. The

carbon in leaves represents a smaller, more dynamic pool, as leaves have a faster turnover rate than stems and branches. Although leaf carbon does not accumulate significantly over time, it contributes to soil carbon as leaves decompose, enriching the soil and supporting the growth of the next generation of trees [

55]. This short-term carbon cycle within the leaf pool enhances soil health, indirectly benefiting the plantation's long-term sequestration potential. Teak plantations offer ecological and economic benefits as they align with global strategies to mitigate climate change. Their high carbon sequestration capacity and long-term storage in wood products contribute to reducing atmospheric CO₂ levels. Therefore, in Southeast Asia and Africa, teak plantations have been promoted to increase forest cover and provide carbon sinks, supporting national and international carbon reduction goals [

56]. Additionally, as global timber demand grows, teak plantations can provide sustainable timber without depleting natural forests. The harvested timber, if used in long-lasting products, retains stored carbon, thus extending the sequestration benefits beyond the plantation [

57]. Carbon stored in these durable wood products helps offset emissions, an advantage recognized in carbon accounting frameworks for managed forests [

58]. Longer rotation cycles allow trees to reach greater sizes and enhance carbon sequestration in stems and branches. Research suggests extending rotation cycles can significantly increase carbon stocks, though it may delay timber yield [

52]. With growing interest in carbon markets, teak plantations hold the potential for generating carbon credits, providing an economic incentive for landowners to adopt sustainable management practices. Carbon credits can be traded to offset emissions in industries that are difficult to decarbonize, such as aviation and manufacturing [

53]. By participating in carbon markets, teak plantations could generate additional income, supporting local economies while contributing to global climate goals.

5. Conclusions

Accurately estimating AGB remains challenging. While the destructive method of harvesting and weighing tree components provides precise measurements, it is expensive, labor-intensive, often illegal, impractical for large-scale studies, and environmentally unsustainable. Nowadays, advanced technologies in forestry offer efficient and precise methods for estimating AGB. Our studies show that ALS's strength lies in structural assessments rather than detailed biomass composition. Meanwhile, orthophoto analysis sometimes overestimates AGB and total carbon, particularly in dense forests. However, it may still be helpful in contexts where rapid biomass assessments are needed without extensive field surveys. The results could suggest that orthophoto analysis has the potential for AGB and carbon stock estimation when ALS is unavailable, though it would need calibration for specific forest structures to improve accuracy. The findings on tree height measurement accuracy between ALS, orthophoto extraction, and field methods highlight significant differences in precision, which align with research comparing remote sensing technologies in forestry. Combining LiDAR and orthophoto data could improve accuracy using orthophotos for tree crown identification and LiDAR for tree height data. This approach would leverage each technology's strengths, potentially reducing over- and underestimations of AGB. Site-specific calibrations using field data may improve remote sensing accuracy. Our results suggest that ALS is more suitable for large-scale forest biomass assessments due to its ability to capture 3D structural information, which is essential for estimating total biomass. Orthophoto data may be helpful in open or less dense forests, where overlapping crowns and understory are less likely to cause errors. Using ALS with orthophotos may help bridge accuracy gaps, especially in dense canopy forests where ground data collection is challenging. Field calibration is essential to improve overall accuracy, particularly for orthophotos susceptible to environmental factors such as light, shadow, and seasonal foliage variations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M., L.R. and K.S.; methodology, P.M., L.R. and K.S.; software, C.T., J.Y., K.S. and T.C.; validation, J.Y., S.S. and P.S.; formal analysis, K.S.; investigation, J.Y., T.K., N.J., P.S. and N.C.; resources, T.K., S.S., N.J. and N.C.; data curation, C.T., L.R. and N.J.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M. and T.C.; writing—review and editing, C.T., L.R. and T.K.; project administration, L.R., J.Y. and T.K.; funding acquisition, L.R. and T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Thailand Science Research and Innovation and the Kasetsart University Research and Development Institute, KURDI, FF(KU)42.67.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the Chief and all staff of Mae Jang Forest Plantation, Forest Industry Organization (FIO), for their invaluable support during the fieldwork. Their assistance and cooperation greatly contributed to the success of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, S.; Feng, Z.; Chen, P.; Khan, T.U.; Lian, Y. Nondestructive estimation of the aboveground biomass of multiple tree species in boreal forests of China using terrestrial laser scanning. Forests 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.E.; Plourde, L.C.; Martin, M.E.; Braswell, B.H.; Smith, M.L.; Dubayah, R.O.; Blair, J.B. Integrating remote sensing and field data to estimate vegetation carbon pools in a temperate forest. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 100(4), 507–518. [Google Scholar]

- Wassihun, A.N.; Hussin, Y.A.; Van Leeuwen, L.M.; Latif, Z.A. Effect of forest stand density on the estimation of above ground biomass/carbon stock using airborne and terrestrial LIDAR derived tree parameters in tropical rain forest, Malaysia. Environ. Syst. Res. 2019, 8(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repola, J. Biomass equations for Scots pine and Norway spruce in Finland. Silva Fenn. 2009, 43(4), 625–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stéphane, M.T.; Pierre, P.; Bonaventure, S.; Jan, H.; Sébastien, G.; Francois, C.; Narcisse, G.K.; Moses, L.G.M.; Gilles, L.M.; Raphaël, P. Using terrestrial laser scanning data to estimate large tropical trees biomass and calibrate allometric models: A comparison with traditional destructive approach. Methods ecol. evol. 2017, 2017. 9, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.S.; Derek, R.P.; Ronald, J.H.; Craig, A.; Coburn, F.H. Estimating aboveground forest biomass from canopy reflectance model inversion in mountainous terrain. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 2010. 114, 1325–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Y.; Zheng, G.; Du, Z.; Ma, X.; Li, J.; Moskal, L.M. Tree-species classification and individual-tree-biomass model construction based on hyperspectral and LiDAR data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15(5), 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazezew, M.N.; Hussin, Y.A.; Kloosterman, E.H. Integrating airborne LiDAR and terrestrial laser scanner forest parameters for accurate aboveground biomass/carbon estimation in Ayer Hitam tropical forest, Malaysia. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 73, 638–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, M.T.; Hilker, N.C.; Coops, G.; Frazer, M.A.; Wulder, G.J.; Newnham, D. ; Ariu. S.C. Assessment of standing wood and fiber quality using ground and airborne laser scanning: A review. For. Ecol. Manage. 2011. 261, 1467–1478.

- Liang, X.; Kankare, V.; Hyyppä, J.; Wang, Y.; Kukko, A.; Haggrén, H.; Yu, X.; Kaartinen, H.; Jaakkola, A.; Guan, F. Terrestrial laser scanning in forest inventories. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 2016. 115, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, H.; Feng, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, P. Applicability of personal laser scanning in forestry inventory. PLoS ONE. 2019, 14(14), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puliti, S.; Ørka, H.O.; Gobakken, T.; Næsset, E. Inventory of small forest areas using an unmanned aerial system. Rem. Sens. 2015, 7(8), 9632–9654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, P.; Tang, J.; Xie, B.; Peng, C. A review of general methods for quantifying and estimating urban trees and biomass. Forests. 2022, 13(4), 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, B.; Khatib, O. Springer Handbook of Robotics. Springer Science & Business Media. Berlin, Germany. 2008. pp. 871–886.

- Ying, Z.; Siyu, X.; Shengqiu, L.; Xianliang, L.; Qijun, F.; Nina, X. Comparative Study of Single-Wood Biomass Model at Plot Level.pdf. Forests. 2024, 15(5), 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT). Mae Moh weather information. https://watertele.egat.co.th/maemoh/. accessed on. 16 October.

- CHC. 2023. Alpha Air 10 LiDAR system specifications. https://www.chcnav.com/dam/jcr:5fda4873-c00a-4f3a-9b83-2cd7f71598a0/AA10_DS_EN.pdf. accessed on. 16 January.

- Heurich, M.; Persson, A.; Holmgren, J.; Kennel, E. Detecting and measuring individual trees with laser scanning in mixed mountain forest of central Europe using an algorithm developed for Swedish boreal forest conditions. Proceedings of Laser-scanners for forest and landscape assessments, Freiburg, Germany. 03-06 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Weiser, H.; Schäfer, J.; Winiwarter, L.; Krašovec, N.; Fassnacht, F.E.; Höfle, B. Individual tree point clouds and tree measurements from multi-platform laser scanning in German forests. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2022, 2022. 14, 2989–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyyppä, J.; Hyyppä, H.; Leckie, D.; Gougeon, F.; Yu, X.; Maltamo, M. Review of methods of small-footprint airborne laser scanning for extracting forest inventory data in boreal forests. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2008, 29(5), 1339–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Popescu, S.; Nelson, R. LiDAR Remote Sensing of Forest Biomass: A Scale-Invariant Estimation Approach Using Airborne Lasers. RSE. 2009, 113(1), 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravipour, A.; Skidmore, A.K.; Isenburg, M.; Wang, T.; Hussin, Y.A. Generating pit-free canopy height models from airborne LiDAR. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 80(9), 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Guo, Q.; Jakubowski, M.K.; Kelly, M. A New Method for segmenting individual trees from the LiDAR point cloud. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2012, 78(1), 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, A.; Saatchi, S.; Mallet, C.; Jacquemoud, S.; Gonçalves, G.; Silva, C.A.; Soares, P.; Tomé, M.; Pereira, L. Airborne lidar estimation of aboveground forest biomass in the absence of field inventory. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Tao, S. Individual tree crown delineation using localized region growing and boundary refinement. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2015, 12(5), 1077–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Espindola, G.M.; Camara, G.; Reis, I.A.; Bins, L.S.; Monteiro, A.M. Parameter selection for region-growing image segmentation algorithms using spatial auto-correlation. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2006, 27(14), 3035–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunpong, P.; Thaiutsa, B.; Wachrinrat, C.; Kanzaki, M.; Meekaew, K. Carbon pools of indigenous and exotic trees Species in a forest plantation, Prachuap Khiri Khan, Thailand. ANRES. 2010, 44(6), 1026–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, B.; Heyder, U.; Weinacker, H. Detection of individual tree crowns in airborne LiDAR data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2006, 72(4), 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, M.K.; Guo, Q.; Kelly, M. Tradeoffs in LiDAR-based forest parameter estimation using single and multiple returns. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 2013. 130, 144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Dandois, J.P.; Ellis, E.C. Remote sensing of vegetation structure using computer vision. Remote Sens. 2010, 2(4), 1157–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolot, Z.J.; Wynne, R.H. Estimating forest biomass using small footprint LiDAR data: An individual tree-based approach that incorporates training data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2005, 59(6), 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawbaker, T.J.; Radeloff, V.C.; Syphard, A.D.; Zhu, Z.; Stewart, S.I. Detection rates of tree mortality attributed to a new biotic agent, Phytophthora ramorum, using Landsat TM and ETM+ data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113(9), 1896–1906. [Google Scholar]

- Næsset, E. Predicting forest stand characteristics with airborne scanning laser using a practical two-stage procedure and field data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 80(1), 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, S.C.; Wynne, R.H.; Nelson, R.F. Measuring individual tree crown diameter with LiDAR and assessing its influence on estimating forest volume and biomass. CJRS. 2003, 29(5), 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudak, A.T.; Lefsky, M.A.; Cohen, W.B.; Berterretche, M. Integration of LiDAR and Landsat ETM+ data for estimating and mapping forest height. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002. 82(2-3).

- Holmgren, J.; Persson, Å. Identifying species of individual trees using airborne laser scanner. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 90(4), 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolkos, S.G.; Goetz, S.J.; Dubayah, R. A meta-analysis of terrestrial aboveground biomass estimation using LiDAR remote sensing. RSE. 2013, 2013. 128, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankare, V.; Holopainen, M.; Vastaranta, M.; Puttonen, E.; Yu, X.; Hyyppä, J.; Hyyppä, H. Individual tree biomass estimation using terrestrial laser scanning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2013, 2013. 75, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maan, G.S.; Singh, C.K.; Singh, M.K.; Nagarajan, B. Tree species biomass and carbon stock measurement using ground based-LiDAR. Geocarto Int. 2015, 30(3), 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.C. Remote sensing in hydrology. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2010, 29(3), 405–421. [Google Scholar]

- Pretzsch, H. Forest dynamics, growth, and yield. Springer Science & Business Media. Berlin, Germany. 2009; pp. 1–39.

- Burkhart, H.E.; Tomé, M. Modeling forest trees and stands. Springer Science and Business Media. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Bi, H.; Cheng, P.; Davis, C.J. Modeling spatial variation in tree diameter–height relationships. For. Ecol. Manage. 2010, 259(5), 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, P.W. Tree and forest measurement. Springer. Switzerland. 2015. pp. 19–24.

- Gadow, K.V.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, X. Forest biometrics. Springer. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.; Chen, Q.; Wang, G.; Liu, L.; Li, G.; Moran, E. A survey of remote sensing-based aboveground biomass estimation methods in forest ecosystems. Int. J. Digit. Earth. 2016, 9(1), 63–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W. Challenges in high-resolution remote sensing for forest biomass estimation: Impacts of shadow, scale, and resolution. RSE. 2018, 2018. 210, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyono, Y.; Hiratsuka, M.; Ando, T.; Morikawa, Y.; Aiba, S. Stand biomass and soil properties on steep slopes in tropical rain forests. J. For. Res. 18(1), 14–23. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S. ; Shukla. R.; Saket, R.; Verma. D. Enhancing carbon stocks accumulation through forest protection and regeneration: A review. Intl. J. Environ. 2019. 8(1).

- Asner, G.P.; Hughes, R.F.; Varga, T.A.; Knapp, D.E.; Kennedy, T. Environmental and biotic controls over aboveground biomass throughout a tropical rain forest. Ecosyst. 2010, 13(6), 1026–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.L.; Rosenqvist, A.; Mora, B. Current remote sensing approaches to monitoring forest degradation in support of countries REDD+ objectives: A review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10(10), 103002. [Google Scholar]

- Kaul, M.; Mohren, G.M.J.; Dadhwal, V.K. Carbon storage and sequestration potential of selected tree species in India. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2011, 16(4), 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.K.R.; Kumar, B.M.; Nair, V.D. Agroforestry as a strategy for carbon sequestration. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2017, 180(6), 645–656. [Google Scholar]

- González-Benecke, C.A.; Gezan, S.A.; Albaugh, T.J.; Allen, H.L.; Burkhart, H.E.; Fox, T.R.; Rubilar, R.A. Local and general aboveground biomass functions for loblolly pine and slash pine trees. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 262(6), 1337–1347. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Sahariah, B.; Zomer, R. Soil carbon sequestration potential and stability under agroforestry systems. Soil Till Res. 2020, 2020. 198, 104522. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, C.K.; Singh, R.P. Carbon storage in tropical forests. Environ. Sci. Policy. 2014, 2014. 9, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, C.A.; Meason, D.F.; Vasquez, A. Timber plantations for carbon capture and climate change mitigation. Int. J. For. Res. 2018, 9064. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Hayes, D. A large and persistent carbon sink in the world's forests. Science. 2011, 6045), 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).