1. Introduction

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into urban planning represents a profound shift in how cities are designed, governed, and experienced. As urban areas grow in size and complexity, the challenges of managing these dynamic ecosystems demand innovative solutions. AI, with its unparalleled capacity for data analysis, predictive modeling, and automation, offers transformative potential to address these challenges. Yet, its adoption also raises critical questions about the future of democracy, public participation, and the ideological foundations of urban planning. This article delves into the intersection of democratic theory, urban planning ideology, and public participation in the era of AI, exploring how this technology is reshaping established paradigms and what it means for the future of inclusive and equitable cities.

Democracy has long been the cornerstone of participatory governance, relying on the active engagement of citizens to shape their environments through collective decision-making. In urban planning, this principle is embodied in participatory models that seek to amplify diverse voices and ensure that development reflects the needs and aspirations of all community members. However, as cities evolve into increasingly complex systems, traditional democratic practices often struggle to keep pace. The sheer scale of urban challenges—from housing affordability and transportation inefficiencies to climate resilience and social equity—demands new tools and approaches. Enter artificial intelligence, a disruptive force that promises to revolutionize urban planning by providing data-driven insights, enhancing transparency, and enabling more informed decision-making.

Yet, the integration of AI into urban planning is not without its risks. While the technology offers opportunities to broaden citizen engagement and improve governance, it also poses significant threats to democratic values if not implemented thoughtfully. Issues such as algorithmic bias, data privacy, and the digital divide risk exacerbating existing inequalities and marginalizing vulnerable populations. Moreover, the lack of transparency in many AI systems can erode public trust, raising concerns about accountability and fairness in decision-making. These challenges underscore the need for a critical examination of how AI interacts with the principles of democracy and the ideologies that underpin urban planning.

This article situates the discussion within established theoretical frameworks, drawing on the work of thinkers such as John Stuart Mill, whose emphasis on informed consent and individual autonomy highlights the importance of empowering citizens in the face of technological change. It also engages with theories of democratic elitism, pluralistic planning models, and critical perspectives such as James O’Connor’s (1978) critique of capitalist urbanism and Paul Davidoff’s (1965) advocacy planning. These frameworks provide a lens through which to analyze the ethical and ideological implications of AI in urban planning, particularly its impact on public participation and social justice.

The transformative potential of AI is already evident in real-world applications. Cities worldwide are using AI to improve transportation, energy efficiency, and public safety. However, these successes are accompanied by significant challenges, including concerns about the centralization of power, the erosion of privacy, and the potential for AI to reinforce existing power structures. By examining case studies of AI integration in urban planning, this article highlights both the opportunities and risks associated with this technology, illustrating the importance of balancing innovation with ethical considerations.

At its core, this article argues that the integration of AI into urban planning must be guided by a commitment to democratic principles and inclusive practices. This requires not only addressing the technical challenges of AI but also fostering a deeper understanding of its social, political, and ideological implications. By prioritizing transparency, equity, and active participation, urban planners and policymakers can ensure that AI serves as a tool for empowerment rather than exclusion. In doing so, we can create urban environments that are not only smarter and more efficient but also more responsive, resilient, and representative of the diverse communities they serve.

As we stand on the brink of this transformative era, the stakes could not be higher. The decisions we make today about how to integrate AI into urban planning will shape the cities of tomorrow, determining whether they become spaces of inclusion and opportunity or sites of deepening inequality and disenfranchisement. This article seeks to contribute to this critical discourse, offering a comprehensive exploration of the theoretical, ethical, and practical dimensions of AI in urban planning. By engaging with these issues, we can chart a path toward a future where technology enhances, rather than undermines, the democratic ideals of participation, equity, and justice.

Part I. The Classical Approach

2. Democratic Theory, Urban Planning Ideology, and Public Participation: The Classical Approach

This section explores the fundamental relationship between political theory, urban planning ideology, and public participation, arguing that a specific political theory directly influences the urban planning approach adopted and, consequently, the nature and extent of public participation. This classical perspective lays the foundation for understanding how the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) will transform these established frameworks in the subsequent sections.

2.1. Political Theory and Public Participation: A Critical Examination

The significance of public participation in spatial planning is often underestimated, frequently treated as a mere technical add-on rather than an integral component of democratic governance. This oversight reflects a fundamental lack of understanding of the complexities inherent in democratic theory, its practical application, and the crucial issue of representation. As Lalenis (1993) observes, the scope of public participation is frequently undertaken with "considerable ignorance of the political philosophy of democracy" (p. 3). This lack of awareness leads to the simplistic assumption that public participation is merely an additional planning technique, neglecting the deeper complexities of democracy, its theoretical underpinnings, and the challenges of ensuring fair representation and consideration of the public interest.

To properly address the role of public participation, we must examine the diversity of democratic theories and their inherent implications for citizen engagement. A critical analysis necessitates classifying these theories and analyzing their associated attitudes towards participation:

Classical Democracy (Athenian Experiment): Herodotus and Thucydides provide the foundational context for classical democracy, exemplified by the Athenian experience (Ober, 1989). This model emphasizes direct citizen participation in decision-making, although its applicability to large-scale societies is inherently limited.

Participant Political Culture: Classical thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, Rousseau, Madison, Calhoun, Mill, de Tocqueville, among others, contributed to the concept of a "participant political culture," emphasizing the importance of citizen engagement and the role of participation in shaping political systems. This perspective highlights the importance of individual agency and the active role of citizens in democratic governance.

Marxist Analysis of Political Participation: Marx, Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg, and Trotsky provided critical analyses of political participation within a Marxist framework, emphasizing the influence of class struggle and economic power dynamics on political participation. This perspective highlights the inherent inequalities embedded within political systems and the limitations of formal participation mechanisms in addressing systemic power imbalances.

Democratic Elitism: Scholars such as Bachrach (1962), Pareto, Mosca (Zuckerman, 1977), Michels (Breines, 1980), Schumpeter (Swedberg, 2013), C. Wright Mills (1956), Dahl (1966) et al, contributed to the concept of "democratic elitism," arguing that in large-scale societies, power is inevitably concentrated in the hands of a select few, limiting the effectiveness of public participation in shaping political outcomes. This perspective emphasizes the inherent limitations of direct democracy and the need for careful consideration of power dynamics in evaluating the efficacy of public participation mechanisms.

Civic Culture: Almond and Verba's (1963) seminal work on The Civic Culture established a typology of political culture, including the concept of "civic culture" characterized by a mix of participatory and deferential attitudes. This approach highlights the importance of both citizen engagement and respect for institutional authority in fostering stable and effective democratic systems.

Demospeciocracy: Bahm's concept of "demospeciocracy" (Bahm, 1968) adds another dimension, underscoring the need to balance popular sovereignty with considerations for the welfare of the entire community, including future generations. This highlights the inherent tensions between immediate desires and long-term sustainability.

These diverse perspectives highlight the complex and often contradictory nature of democratic theory. The application of these theories to urban planning demonstrates the significant influence of political ideology on planning practices and public participation mechanisms.

2.2. Political Theory and Urban Planning: An Inherent Intertwining

The political nature of urban planning is undeniable, a point underscored by numerous theorists who have analyzed and critiqued its inherent relationship to broader political and social structures. While often presented as a technical process, urban planning is fundamentally shaped by underlying political ideologies, power dynamics, and the distribution of resources. This section delves deeper into this relationship, examining the contributions of theorists such as James O'Connor, Richard Klosterman, and Paul Davidoff.

2.2.1. O'Connor's Critique of Capitalist Urban Planning:

James O'Connor's (1978) analysis of urban planning within capitalist societies provides a critical framework for understanding the political economy of urban development. O'Connor argues that, to a considerable extent, the working-class struggle for improved working conditions and better quality of life has been redirected into concerns related to social issues such as racial and sexual equality, environmental protection, and sustainability. This shift, according to O'Connor, serves the interests of capital by subtly altering the nature of class struggle. Instead of directly challenging the exploitative structures of capitalism, the focus shifts to seemingly less threatening issues.

O'Connor contends that modern spatial and development planning fundamentally aims to improve production and reproduction conditions for capital. This entails reinforcing capital's domination of the labor market, lowering the reproduction costs of labor power, and restructuring the workforce. This process necessitates significant state support, including financial backing and political legitimization. In essence, O'Connor posits that seemingly progressive urban planning initiatives may ultimately serve to reinforce existing capitalist power structures, rather than fundamentally challenging them (O'Connor, 1978).

2.2.2. Klosterman's Deconstruction of Technocratic Planning:

Richard Klosterman's (1979) work directly challenges the notion of urban planning as a purely technocratic endeavor, devoid of political considerations. He argues that planning is inherently political and that attempts to portray it as value-neutral are fundamentally flawed. Klosterman critically examines the "social engineering" model of planning—a model that presumes the separation of "is" and "ought," the possibility of a value-free social science, and a means-ends conception of rationality. He deconstructs this model, demonstrating its inherent limitations and its inability to address the underlying power dynamics and social inequalities that shape urban environments. Klosterman concludes that a value-neutral approach to planning is not merely impractical but fundamentally inappropriate, asserting that the political dimensions of planning must be openly acknowledged and addressed.

2.2.3. Davidoff's Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning:

Paul Davidoff's (1965) influential paper, "Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning," directly addresses the relationship between political theory and urban planning. Davidoff argues that intelligent choices about public policy are best made when diverse political, social, and economic interests are represented in the planning process. He advocates for a pluralistic approach, suggesting that various competing interests should develop their own plans, fostering a dynamic process of political debate and negotiation. Davidoff strongly criticizes a narrow definition of the planner's role, stating that a planner who is only concerned with land use regulation fails to grasp the multifaceted nature of a city. Davidoff asserts that a city encompasses its people, their practices, and their social, cultural, economic, and political institutions. Therefore, a city planner must comprehend and engage with all these factors (Davidoff, 1965, p. 336).

2.2.4. Critical Reflections and Synthesis:

These three perspectives—O'Connor's critical analysis of capitalist urban planning, Klosterman's deconstruction of technocratic planning, and Davidoff's advocacy for a pluralistic approach—collectively highlight the inherent political nature of urban planning. While differing in their specific approaches, they all underscore the need for critical engagement with power dynamics and social inequalities within the planning process. Acknowledging this political dimension is essential for promoting truly equitable and democratic urban development.

2.3. Political / Democratic Theory and Public Participation in Urban Planning: A Tautological Relationship

This section examines the intricate and often tautological relationship between political theory, democratic ideals, and public participation within the context of urban planning. The fundamental assertion is that a particular political theory not only determines the approach to urban planning but also shapes the nature and extent of public participation involved. This relationship can be expressed through three interconnected claims:

Political Theory Determines Participation: A specific political theory fundamentally determines the degree and style of public participation. The underlying political philosophy dictates how much public involvement is deemed necessary or desirable, and the mechanisms used to facilitate that involvement.

Planning Approach Reflects Political Theory: The chosen approach to spatial planning directly reflects the underlying political theory. Whether the approach prioritizes efficiency, consensus-building, or conflict resolution is a direct consequence of the prevailing political ideology.

Participation Signifies Political Theory: The level and nature of public participation in spatial planning serve as a significant indicator of the underlying political theory. The degree of participation, the mechanisms used, and the extent to which diverse perspectives are incorporated all reflect the dominant political ideology.

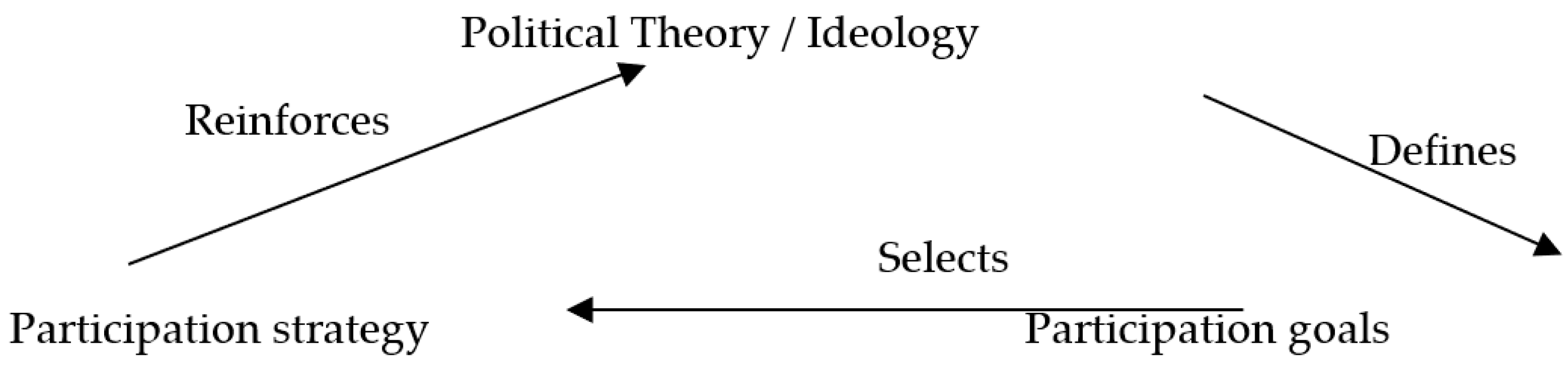

Yukubousky (1979) succinctly summarizes this relationship as a "Participation Tautology" (p. 3). This tautology highlights the reciprocal and reinforcing nature of the relationship between political theory, planning approaches, and public participation. In other words, the political theory shapes the planning process, which in turn shapes the level and style of public participation, which, in turn, reinforces the original political theory. This is a dynamic and iterative process where each element mutually influences the others (

Figure 1).

2.3.1. Thornley's Analysis of Participation Strategies: A Framework Based on Social Order Theories

A. Thornley (1977) offers a particularly insightful analysis of participation strategies, grounding his framework in contrasting theories of social order. Thornley begins by framing the spectrum of social order theories as "polar opposites"—a theory of consensus and stability versus a theory of conflict. He then situates three distinct perspectives on participation within this framework, drawing on the work of Almond and Verba, Dahrendorf, and Marx to illuminate the theoretical underpinnings of each approach (

Figure 2):

Technocratic Planning (Consensus and Stability): This model, aligning with Almond and Verba's (1963) emphasis on consensus and stability in their analysis of civic culture, prioritizes efficient and technically sound planning with minimal conflict and limited public engagement. Participation, if any, serves primarily as a means to gather information or confirm pre-determined decisions. This approach reflects a belief in the inherent stability of social order and the efficacy of top-down decision-making processes.

Pluralistic Planning (Containment and Bargaining): Reflecting Dahrendorf's (1958, 1959) concept of managing conflict through pluralistic structures, this model acknowledges the existence of conflict but seeks to contain and manage it through negotiation and compromise. Participation involves bargaining among various stakeholders to reach a mutually agreeable outcome. The goal is to integrate different interests and achieve a negotiated settlement, thereby maintaining social order without resorting to drastic measures.

Participatory Planning (Conflict and Increased Consciousness): This approach, consistent with Marx's (1848) conflict theory, embraces conflict as an inherent and transformative aspect of social change. Participation is viewed as a mechanism for fostering collective consciousness and empowering the public to play a dominant role in shaping their own environment. The production of a specific plan is less central than the process of empowering the community and enabling the expression of collective agency. This model suggests that social change is driven by conflict, and public participation plays a crucial role in this process.

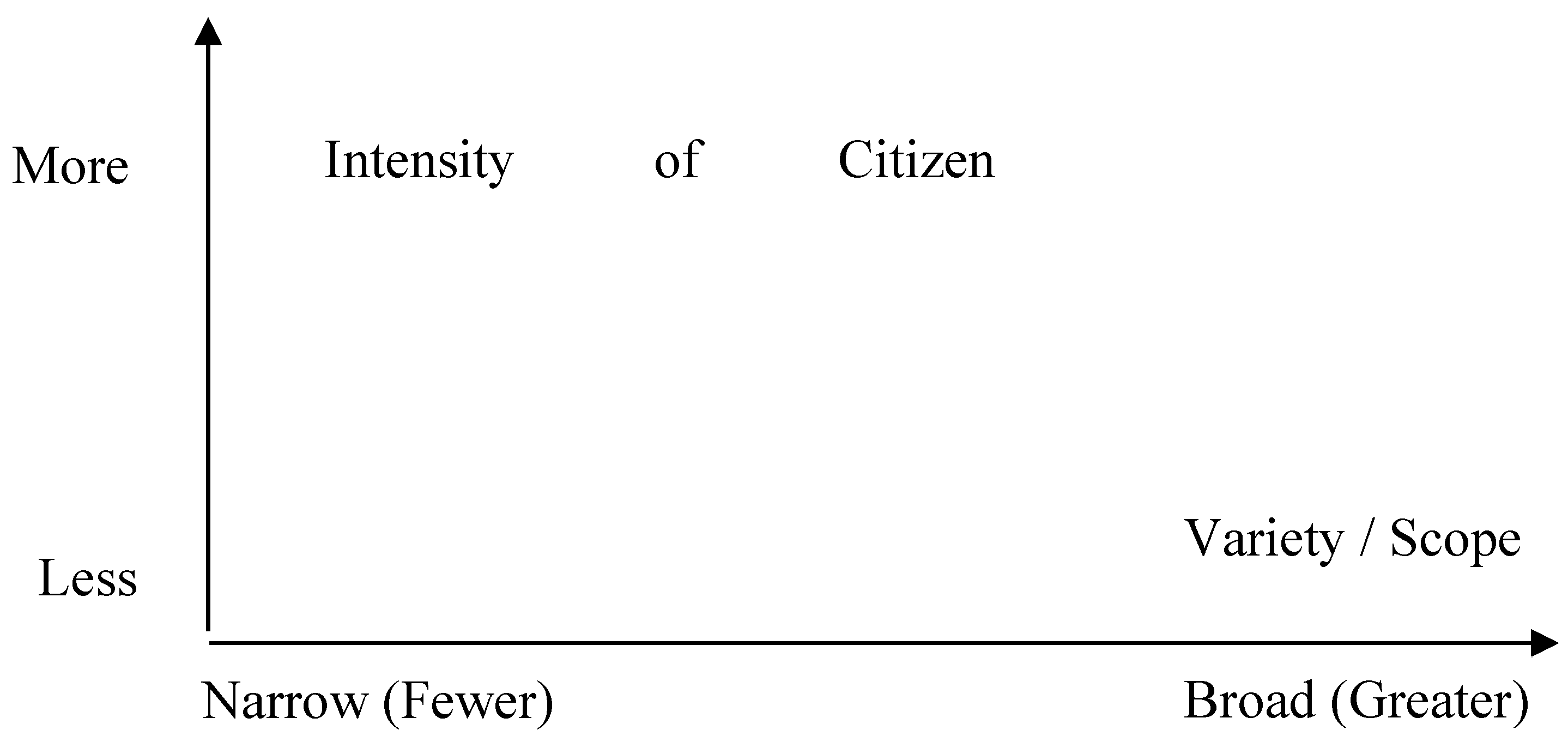

Thornley's framework illustrates how the chosen approach to participation directly reflects the underlying assumptions about the nature of social order. The intensity and scope of participation vary across these perspectives (Cole, 1973:19), ranging from low intensity and limited scope in the technocratic approach to high intensity and broad scope in participatory planning, with pluralistic planning situated in between.

2.3.2. The Interplay of Ideology, Planning, and Participation:

The influence of political ideology on planning and participation is further evident in the interplay between legislation, regulation, and the dominant social paradigms. Legislation and regulations, reflecting prevailing ideologies, play a crucial role in shaping participation processes. The degree of public involvement generally increases as the planning process moves from a technocratic approach emphasizing consensus and stability to a participatory approach emphasizing conflict and increased consciousness, with pluralistic planning occupying an intermediate position. This highlights the critical connection between political theory, planning practices, and the nature of public engagement.

3. Participation Strategies: A Multifaceted Approach

This section delves into the diverse strategies employed to implement public participation in spatial planning. It analyzes the characteristics of these strategies, their underlying assumptions, and their limitations, highlighting the crucial interplay between the "how" and "why" of participation.

3.1. Sources and Typologies of Participation Strategies: From Top-Down to Bottom-Up

The concept of "strategy," in the context of public participation, refers to the specific programs and mechanisms employed to facilitate public involvement in decision-making processes. These strategies are not static; they evolve over time, reflecting changes in political ideologies, societal values, and the resources available to different actors.

Initially, local authorities and planners primarily determined the "rules of the game," dictating the scope and nature of public participation. Central governments also frequently established broader frameworks, specifying general requirements and guidelines, with the degree of specification and intervention varying according to the prevailing political climate.

However, over recent decades, various groups within the public have become increasingly proactive in formulating their own participation strategies. This shift initially manifested as resistance to top-down initiatives but has evolved into sophisticated approaches where diverse groups actively propose alternative plans and advocate for their implementation.

3.1.1. Analyzing Participation Strategies: Beyond the "How" to the "Why"

Early attempts to classify and analyze participation strategies primarily focused on the "how"—the specific methods and techniques employed. These analyses, however, often overlooked the crucial "why"—the objectives of the participants and the broader political context shaping the process. Understanding the motivations behind participation strategies is crucial for assessing their effectiveness and impact.

The objectives of participants range widely, from influencing specific decisions to promoting broader social and political goals. The political climate also plays a significant role, shaping both the willingness of authorities to engage in participatory processes and the resources available to facilitate meaningful public engagement. The interplay between these factors—participants' objectives and the broader political context—is crucial for understanding the effectiveness and impact of participation strategies.

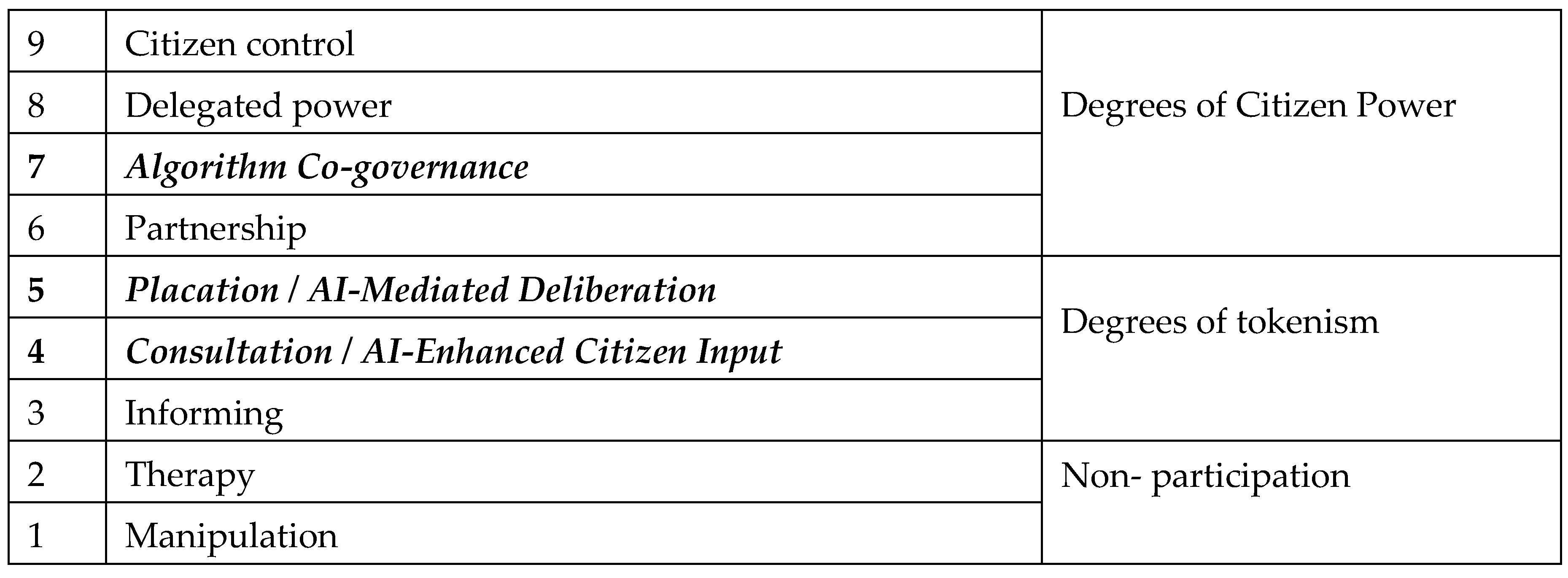

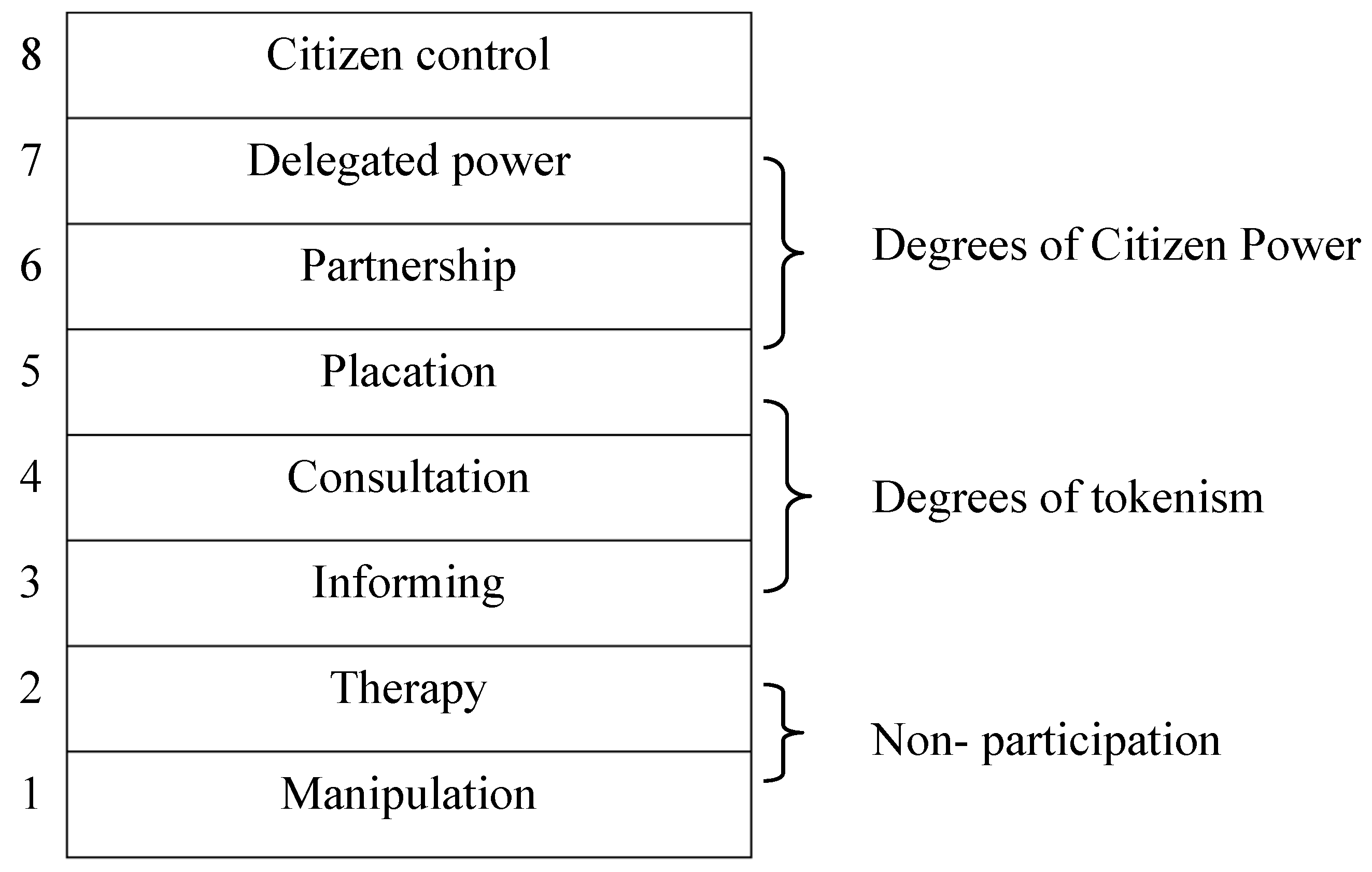

3.1.2. Limitations of Uni-Dimensional Approaches: Beyond Arnstein's Ladder

Theoretical analyses of public participation often rely on uni-dimensional models, positing a linear progression from minimal to maximal public involvement. A prime example is Sherry Arnstein's (1969) "ladder of citizen participation," which presents a hierarchical structure ranging from manipulation to citizen control (

Figure 3).

While Arnstein's ladder provides a useful framework for understanding different levels of public influence, it is limited in its ability to account for the diversity of participation strategies and the complexities of real-world contexts. A uni-dimensional approach fails to adequately capture the following:

Varying intensity of involvement: A single-dimension scale cannot effectively capture the varying intensity of public involvement across different planning projects and issues.

Multiple objectives: Different participation strategies may pursue multiple, sometimes competing, objectives, which a single-dimension scale cannot effectively represent.

Diversity of contexts: The political context, resources available, and the specific issue at stake significantly impact participation strategies, which a uni-dimensional scale may fail to reflect adequately.

Consequently, more sophisticated multi-dimensional models are necessary to fully capture the complexity of public participation strategies in spatial planning.

3.1.3. The Need for Multi-Dimensional Analysis:

The limitations of uni-dimensional models highlight the need for more comprehensive approaches that consider the multiple dimensions of participation. A multi-dimensional approach should consider:

Intensity of public involvement: The degree of influence exerted by participants on the final decision-making process.

Scope of participation: The range of issues and the number of participants engaged in the process.

Diversity of strategies: The variety of mechanisms employed to facilitate public engagement.

Political context: The prevailing political climate and its impact on participation.

Participant objectives: The goals and motivations of different participant groups.

Cole's (1973:18) two-dimensional model, adding scope/variety and intensity to the analysis, represents a step in this direction (

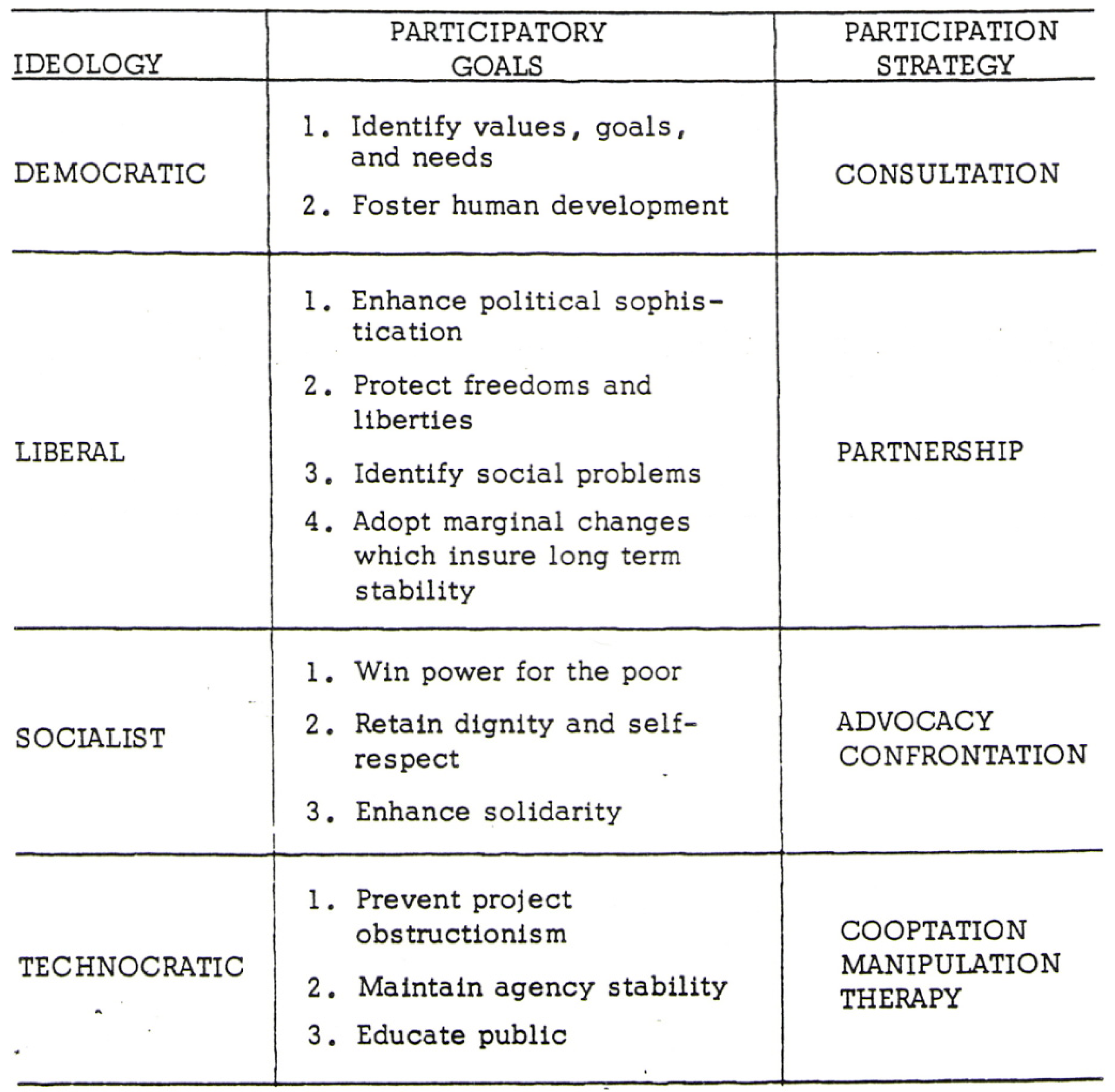

Figure 4). Similarly, Hain (1980) highlights the "Liberal" and "Radical" perspectives on participation, emphasizing the differing goals and approaches to democratic reform. Yukubousky (1979) further complicates this by emphasizing that multiple ideologies often shape participatory goals and strategies, resulting in compromises and complex interactions amongst different actors (

Figure 5).

3.2. Planning Models and Participation Strategies: A Reciprocal Relationship

This section explores the close relationship between planning models and participation strategies, arguing that they are mutually constitutive. The choice of a planning model significantly influences the type and extent of public participation, while, conversely, the desired level of participation can shape the selection of the planning model itself. This reciprocal relationship underscores the inherent interconnectedness between theoretical frameworks, planning methodologies, and the practical implementation of public engagement.

To illustrate the evolution of planning models and their implications for participation, it is worth revisiting the foundations of planning, beginning with the Geddesian model.

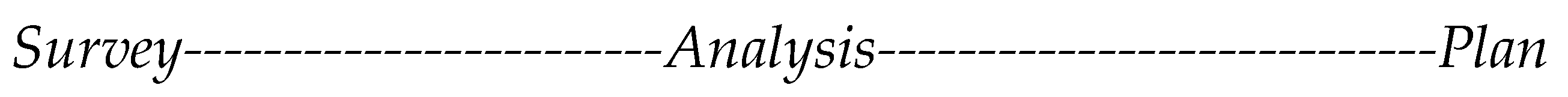

The Geddesian Model: Developed by Patrick Geddes (1915), this model emphasizes a cyclical process: Survey-Analysis-Plan (

Figure 7). While public participation is not explicitly depicted in Geddes’s original framework, it can be inferred from his suggestions regarding involvement through education (e.g., public exhibitions), information gathering (e.g., active participation), and the submission of alternative proposals. However, the Geddesian model lacks a clear mechanism for incorporating public input during the initial stages of goal setting, representing a significant limitation.

Over time, other planning models emerged, integrating public participation in varying scopes, phases, means, and categories of participants. These models also incorporated various techniques, such as AIDA (Attention-Interest-Desire-Action), (Pramita & Manafe, 2022) which allows planners to strategically consider different viewpoints and potential outcomes at the outset of the planning process.

3.2.1. The Interdependence of Planning Models and Participation

The means and strategies used to implement public participation reflect the interdependence between planning models and participation. This relationship is so profound that the type of participation employed can fundamentally shape the planning process itself. Conversely, a pre-selected spatial planning model often predetermines the participation strategies that will be employed. Thus, the choice of a planning model is not merely a technical decision but one with significant implications for public engagement.

The adoption of a specific planning model strongly influences the participation strategy that planning organizers will use. However, the extent to which various participant groups adopt this strategy depends on the degree of alignment between the strategy and the objectives of those groups. This dynamic interaction between pre-defined strategies and the specific goals of different actors is critical to understanding the success or failure of public participation efforts.

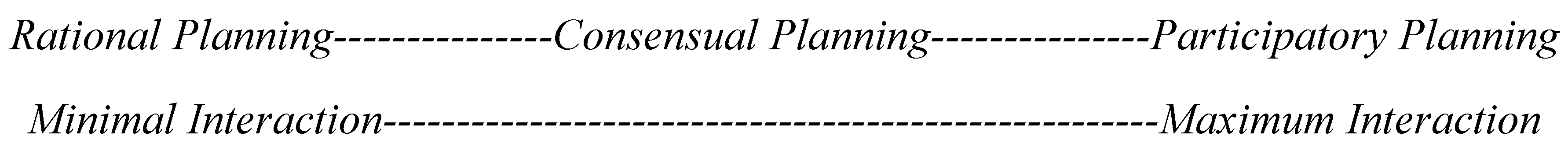

The relationship between types of planning and the degree of public involvement is illustrated in

Figure 6. In it, the categories of Rational Planning, Consensual Planning, and Participatory Planning are associated with increasing levels of public involvement—from minimal or non-existent (in Rational Planning) to the fullest extent (in Participatory Planning).

Figure 6.

Ideal Types of Planning and interaction Involved (R. W. Smith, 1973)..

Figure 6.

Ideal Types of Planning and interaction Involved (R. W. Smith, 1973)..

Figure 7.

The Geddesian Model (Geddes, 1915).

Figure 7.

The Geddesian Model (Geddes, 1915).

It is also important to consider the administrative, policy-making, and political processes underlying land use change. These processes involve a complex web of interactions—communication, negotiation, exchange, cooperation, competition, influence, and control—all of which shape the outcomes of planning efforts. The specific patterns of interaction within a given context are vital for understanding the broader dynamics of urban development. These interactions, shaped by both formal institutions and informal power dynamics, directly impact the effectiveness of participation strategies.

3.3. Structural Characteristics of Participation Strategies: A Multifaceted Analysis

This section analyzes the structural characteristics of participation strategies, moving beyond simple typologies to examine the key elements that shape the effectiveness and impact of public engagement in spatial planning. The analysis considers the focus of participation, its timing and phasing, the range of participants involved, and the methods employed to facilitate interaction.

3.3.1. Key Dimensions of Participation Strategies:

To understand the structural characteristics of participation strategies, four key questions must be addressed:

Focus: What is the primary aim of the participation strategy? What specific aspects of the planning process are targeted for public input?

Timing/Phasing: When does participation occur within the planning process? Is it concentrated at specific stages, or is it integrated throughout the entire process?

Participants: Who is involved in the participation process? Are all stakeholders represented, or are certain groups marginalized?

Methods: How is participation facilitated? What specific techniques and mechanisms are used to gather and integrate public input?

3.3.2. The Three Components of Participation Focus:

A participation program typically involves three key components: information dispersal, information collection, and interaction among participants. Access to information is a critical precondition for meaningful participation. Restricted access undermines the ability of citizens to evaluate proposed plans and make informed decisions. Transparency, in this context, demands that information be comprehensive, unbiased, and accessible to all stakeholders, allowing for open dialogue and the consideration of diverse perspectives. The dispersal and collection of information, however, are insufficient without robust interaction among participants.

Effective interaction requires more than simply disseminating information. It should facilitate:

Further dispersal of information to widen the scope of the debate.

Involvement of a wide spectrum of participants, including experts and advocacy groups, ensuring a diversity of perspectives.

Encouragement of participation from all members of the community, particularly those who might otherwise be marginalized (positive discrimination of "target groups").

The approach to these three components—information, dispersal, collection, and interaction—differs significantly depending on the underlying perspective on social order:

Consensus-based approaches: Emphasize information exchange, with authorities controlling the dissemination and collection of information. Interaction is limited and largely serves to confirm pre-determined decisions.

Bargaining-based approaches: View interaction as central, with information exchange serving as a preliminary step. While authorities may retain some control, all parties have the opportunity to disseminate and collect information. Genuine cooperation is prioritized.

Conflict-based approaches: See conflict as inherent and transformative. Information dissemination is decentralized, with various actors, including advocacy groups, actively sharing information. Interaction is vital, and information collection is less central because participants often possess in-depth knowledge of local issues. The goal is social change, not simply information gathering (Gutch et al., 1979:4).

3.3.3. Timing, Participants, and Methods:

Participation is most likely to occur during policy-related phases: aims definition, consideration of options, selection of alternative strategies, and adoption of a final plan (Benwell, 1980). These stages require value judgments and conscious choices. While focused on these crucial stages, participation should not be limited to them; excluding it from other phases (e.g., generation of alternatives or plan preparation) would be unrealistic, especially in advocacy planning.

"Positive discrimination" is essential for ensuring that all segments of the community, including marginalized groups, have the opportunity to participate. Various methods can be used to ensure inclusivity, such as direct mailings, translations, meetings in multiple languages, dedicated websites, and accessible polling stations. The e-Europe 2005 Action Plan's emphasis on "e-inclusion" highlights the potential of digital technologies to expand participation opportunities to disadvantaged communities, specific citation needed).

A wide array of participation techniques exists, but their effectiveness is frequently limited by factors such as insufficient funding, lack of understanding, and limited time. Gutch et al.'s (1979) research, comparing public preferences for participation techniques to those preferred by local authorities, demonstrates a considerable gap between the two, highlighting the need for a more responsive approach to public engagement. The research also underscores the limitations of using case studies to generalize about preferences, as local contexts significantly impact the choice of techniques (Lalenis, 1993, p. 194).

Part II. The Era of Artificial Intelligence

4. AI and Democratic Theory: Implications for Urban Planning

This section explores how artificial intelligence (AI) intersects with democratic theory, urban planning ideologies, and public participation. It examines the opportunities and challenges AI presents for democratic governance, informed citizenship, and participatory planning.

4.1. Mill’s Vision of Informed Citizenship in the Digital Age

John Stuart Mill’s emphasis on informed and engaged citizens as the cornerstone of democracy remains highly relevant in the era of AI. AI has the potential to enhance Mill’s vision by providing tools for data visualization, policy outcome simulations, and evidence-based public discourse. These tools can empower citizens to make informed decisions and participate more effectively in urban planning processes.

However, the digital divide poses a significant challenge to this ideal. Unequal access to technology and digital literacy risks undermining informed consent and collective decision-making, particularly for marginalized communities. To address this, urban planners must ensure equitable access to AI-enabled tools and prioritize digital inclusion.

A successful example of AI enhancing citizen engagement is Barcelona’s Decidim platform, which increases transparency and resource allocation efficiency. This aligns with Mill’s vision of an informed and engaged citizenry, demonstrating how AI can empower citizens to shape urban policy effectively.

While AI has the potential to enhance informed citizenship, as envisioned by Mill, K. Crawford (2021) warns that the material and labor costs of AI systems—such as the environmental impact of data centers and the exploitation of low-wage workers—must be considered. These factors could exacerbate existing inequalities, particularly for marginalized communities who are already disproportionately affected by the digital divide."

4.2. Democratic Elitism and AI’s Democratizing Potential

Theories of democratic elitism emphasize the role of experts and elites in policymaking. AI could exacerbate this trend by concentrating power in the hands of those who design, control, and interpret AI algorithms. The "black box" nature of many AI systems raises concerns about transparency and accountability, potentially increasing the influence of a technologically savvy elite. S. Zuboff analyzes the concept of surveillance capitalism to highlite how AI systems, controlled by teck giants, could concentrate power and undermine democratic processes. She describes how data is extracted and exploited for profit in a way that undermines democratic values and individual autonomy. C. O'Neil (2016) warns that opaque and unaccountable algorithms—what she calls 'weapons of math destruction'—can reinforce inequality and undermine democracy. In urban planning, the use of such algorithms risks concentrating power in the hands of a technologically savvy elite, exacerbating democratic elitism.

Conversely, AI also has the potential to democratize expertise. AI-enabled tools can make complex urban data and analyses more accessible to the general public, empowering citizens to understand the rationale behind policy decisions and engage in informed debates. This could counteract elitism by making expert knowledge more widely available.

4.3. Pluralistic and Participatory Planning in the AI Era

AI has the potential to transform pluralistic and participatory planning by facilitating online platforms for deliberation and participation. Digital forums, online surveys, and AI-enabled feedback mechanisms can encourage broader engagement than traditional methods, fostering a more inclusive democratic process.

However, the digital realm also presents challenges. Echo chambers and filter bubbles can reinforce existing biases, hindering constructive dialogue and consensus-building. Additionally, concerns about data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the manipulation of online discourse complicate the impact of AI on civic culture. Crawford’s research extensively documents how algorithmic systems reflect and amplify existing societal biases. It highlights the need for rigorous data auditing and diverse datasets in AI training to mitigate bias in urban planning decision-making.

4.4. AI and Democratic Theory: A Deeper Dive

AI directly challenges and reinforces fundamental aspects of democratic theory:

AI could enable a form of direct democracy through online voting platforms and participatory budgeting tools, allowing citizens to directly shape urban policies. However, this assumes equitable access to technology and digital literacy. Alternatively, AI could reinforce representative democracy by delegating complex technical decisions to algorithms, increasing reliance on expert advisors and potentially limiting citizen input.

Marxist critiques focus on class struggle and unequal power distribution. AI-enabled systems could reinforce existing power imbalances if the data used to train algorithms reflects societal inequalities. Algorithmic bias can perpetuate social inequalities. Kate Crawford (2021) argues that AI's material and labor costs disproportionately affect marginalized communities, while Shoshana Zuboff (2019) warns that surveillance capitalism transforms personal data into a tool for behavioral manipulation, further entrenching corporate power and eroding democratic accountability. R. Benjamin (2019) critiques how AI systems, under the guise of neutrality, often perpetuate racial hierarchies and discrimination—what she calls the 'New Jim Code.' And from the same perspective, S. U. Noble (2018) demonstrates how algorithmic bias in search engines and AI systems perpetuates racial and gender stereotypes, reinforcing existing inequalities. This underscores the need for careful scrutiny of the data used to train AI systems in urban planning, particularly to avoid exacerbating social inequities.

Conversely, AI could serve as a tool for social justice by providing data-driven insights into systemic imbalances, informing policies to address them, and empowering underrepresented groups.

4.5. AI’s Impact on Urban Planning Paradigms

AI significantly reshapes urban planning paradigms, including technocratic planning, pluralistic planning and participatory models. AI amplifies the efficiency of technocratic planning by providing tools for sophisticated modeling, prediction, and optimization of urban systems. However, a purely data-driven approach risks sidelining human values and public input. V. Eubanks (2018) critiques how AI and automated decision-making systems often disproportionately harm low-income and marginalized communities. In urban planning, this raises concerns about the use of AI in areas like housing allocation and public services, where biased algorithms could exacerbate social inequalities.

AI can enhance pluralistic planning by facilitating the analysis of diverse inputs, identifying common ground, and developing compromise solutions. Platforms like Consul and Decidim enable large-scale public consultations, aggregating feedback from diverse groups and identifying areas of consensus and conflict. For participatory planning, AI offers tools to empower marginalized communities, such as data collection and analysis, visualization of policy impacts, and improved access to information. However, the risk of reinforcing existing biases is significant.

4.6. AI’s Impact on Urban Spaces and Collective Action

AI’s integration into urban planning could reshape cities and public spaces in profound ways:

AI-enabled planning may prioritize efficiency and consensus, leading to functional but homogeneous cities. The privatization of public spaces through smart infrastructure could reduce accessibility and democratic character.

By prioritizing consensus, AI may suppress dissent and conflict, leading to cities that are less responsive to systemic inequalities. Grassroots movements may be marginalized, reducing the diversity of urban life.

AI could enable new forms of digital activism, such as online petitions and virtual protests. The integration of AI into public spaces could create hybrid environments where physical and digital interactions coexist.

In general, the integration of AI into urban planning presents both opportunities and challenges for democratic theory and public participation. While AI can enhance informed citizenship, democratize expertise, and facilitate pluralistic and participatory planning, it also risks exacerbating inequalities, reinforcing technocratic governance, and undermining trust in decision-making processes.

5. AI and Public Participation Strategies

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into urban planning is rapidly transforming the landscape of public participation, creating both exciting opportunities and significant challenges. While AI offers powerful tools to enhance informed consent and broaden citizen engagement, it also presents significant risks of exacerbating existing inequalities and undermining trust. In this part we will examine an analysis of AI's influence on established participation strategies, a critical assessment of ethical and equity considerations, and an exploration of potential risks to democratic participation.

5.1. Reimagining Citizen Participation: Beyond Arnstein's Ladder

Arnstein's Ladder is traditionally represented as a ladder with eight rungs, progressing from non-participation (manipulation, therapy) to citizen control (delegated power, partnership). AI introduces new dimensions that could be visualized as additional rungs or extensions of existing ones (

Figure 7):

Figure 7.

Nine Modified Rungs on a Ladder of Citizen Participation with AI inclusion (S. R. Arnstein 1969:217 and author’s elaboration).

Figure 7.

Nine Modified Rungs on a Ladder of Citizen Participation with AI inclusion (S. R. Arnstein 1969:217 and author’s elaboration).

Algorithmic Co-governance (New rung): Positioned above "Partnership," representing a new level of collaboration where citizens directly shape urban policies alongside AI systems. It can be perceived as a shared decision-making process between humans and an AI icon.

AI-mediated Deliberation (Modified rung): Integrated this into the "Placation" rung, highlighting AI's role in facilitating structured and informed public discourse. It can be perceived as a network connecting diverse perspectives to a central AI-facilitated platform.

AI-Enhanced Citizen Input (Modified rung): Enhance existing rung ("Consultation") by showing how AI facilitates data collection, analysis and visualization, making public input more effective. This could be depicted by incorporating data visualizations and feedback loops into the visual for these rungs.

In fact, the inclusion of AI in Arnstein’s ladder of participation signifies a diversion from uni-dimensional models towards multi-dimensionality.

5.2. AI's Structural Impact on Public Participation – Multi-Dimensional Participation

AI fundamentally reshapes the structural characteristics of public participation in urban planning:

Focus: From Information Dispersal to Data Co-creation: Traditionally, participation strategies often focused on information dispersal—providing the public with information about planning projects. AI shifts this focus toward data co-creation, where citizens actively contribute data that informs planning decisions. This is a significant paradigm shift, transforming citizens from passive recipients of information to active participants in data generation.

Participants: Expanding Access and Addressing the Digital Divide: AI can broaden the range of participants in urban planning by overcoming geographical barriers and reaching underserved communities. However, the digital divide remains a significant barrier. Unequal access to technology and digital literacy skills could exclude significant portions of the population, undermining the inclusivity of AI-enhanced participation processes. Planners must actively address this issue to ensure equitable access.

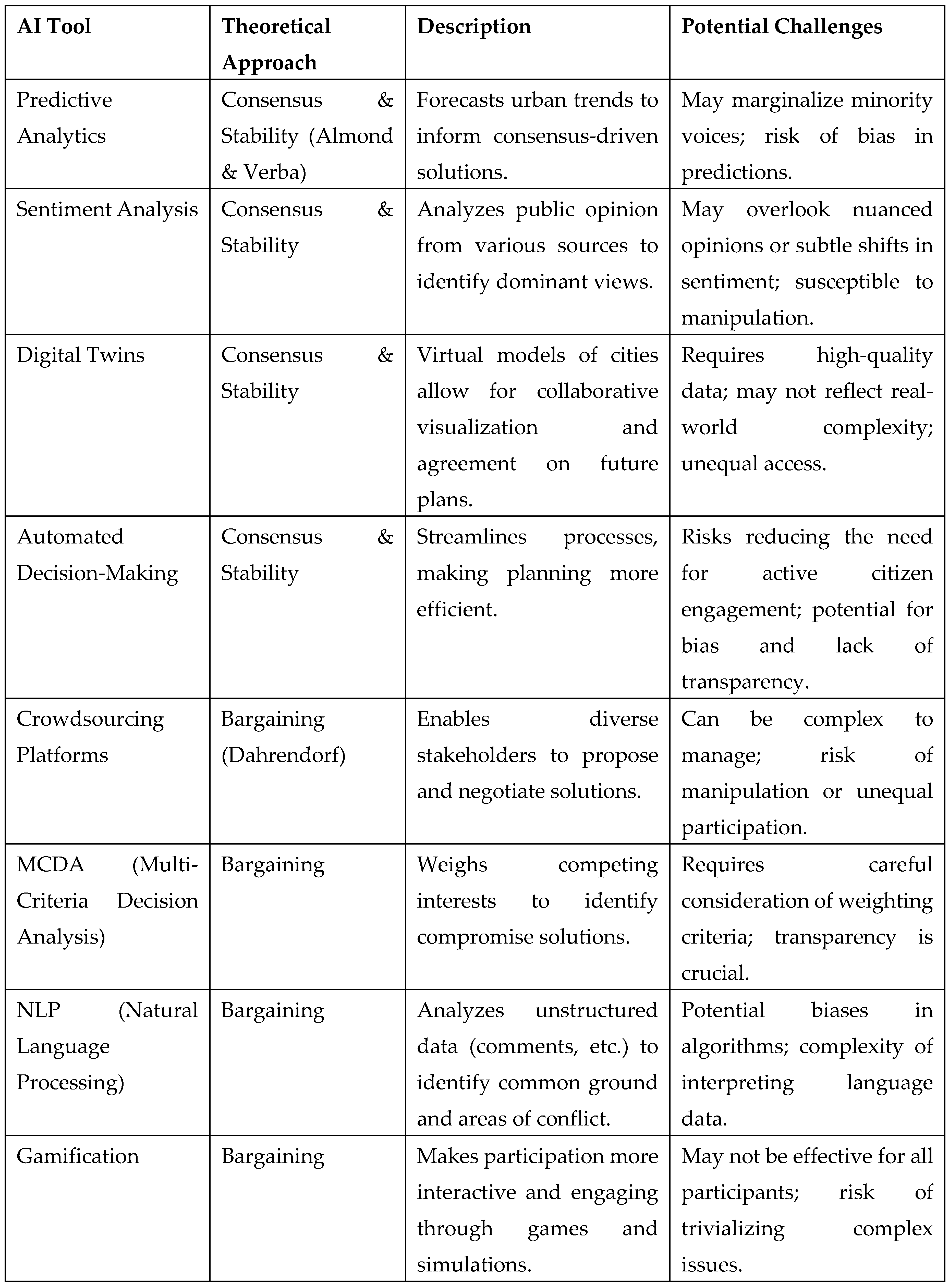

Multi-Dimensional Participation: Methods - Innovative Tools

Artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing public participation in urban planning by introducing innovative tools and methods that enhance the gathering, analysis, and utilization of public input. These tools enable more efficient, inclusive, and dynamic engagement processes, blending online and offline methods while fostering continuous and iterative participation. AI-powered tools such as predictive analytics, crowdsourcing platforms, and virtual reality (VR) (see Fig. ...) are transforming how planners collect and process public input. Predictive analytics allows for data-driven decision-making by forecasting urban trends and citizen needs, while crowdsourcing platforms enable large-scale participation. VR provides immersive experiences for visualizing planning scenarios, making complex proposals more accessible to the public. These tools enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of participatory processes but must be implemented with transparency and accountability to address potential biases and privacy concerns.

AI also facilitates multi-dimensional participation by seamlessly integrating online and offline engagement methods. Tools like sentiment analysis and digital twins allow planners to analyze public sentiment and simulate urban scenarios, creating more inclusive and comprehensive participation processes. Sentiment analysis helps identify community priorities, while digital twins enable stakeholders to explore the impacts of proposed plans in a virtual environment. Despite their potential, these tools must be carefully designed to mitigate risks such as algorithmic bias and ensure accessibility for all populations, bridging the digital divide. By blending online and offline methods, AI ensures that diverse voices are heard, fostering a more equitable and representative planning process.

Moreover, AI enables a shift from stage-limited participation to continuous and iterative engagement throughout the planning process. Real-time feedback loops and adaptive planning tools allow citizens to monitor project progress and provide ongoing input. This creates a dynamic dialogue between planners and the public, ensuring that planning processes remain responsive to evolving community needs and priorities. By fostering a culture of continuous participation, AI helps build trust and collaboration between stakeholders, ultimately leading to more resilient and inclusive urban development. However, challenges such as data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the digital divide must be carefully addressed to ensure that these innovative tools empower rather than exclude. Through thoughtful implementation, AI can serve as a catalyst for more democratic, participatory, and equitable urban planning.

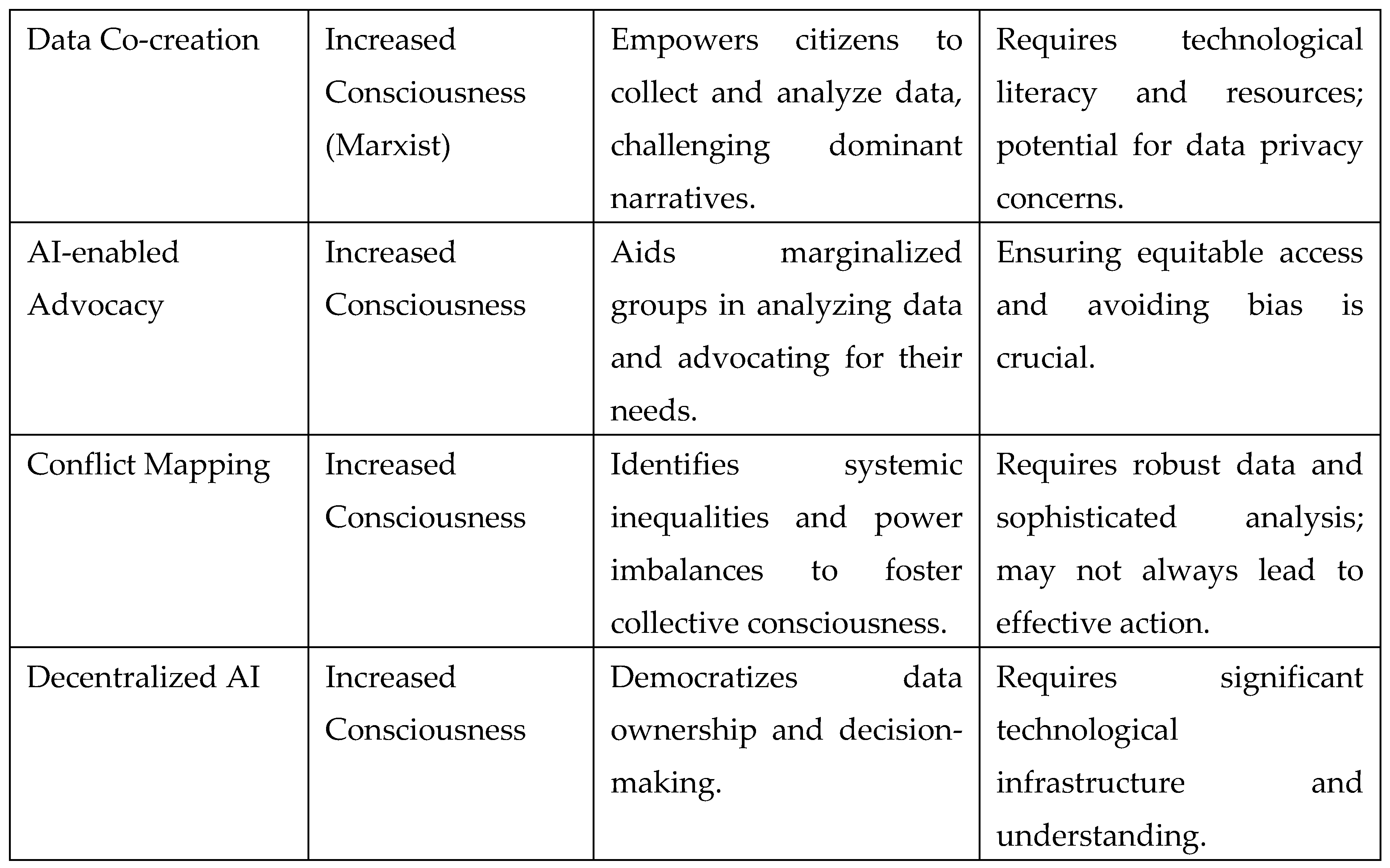

Below, in

Figure 8, we classify these tools based on their relevance to three key theoretical frameworks:

Consensus and Stability (Almond and Verba),

Containment and Bargaining (Dahrendorf), and

Increased Consciousness (Marxist). AI enables more nuanced and multifaceted forms of participation, blending online and offline methods, as shown in the following table:

Figure 8.

A summary of AI tools and theoretical approaches to plannning participation (author’s elaboration).

Figure 8.

A summary of AI tools and theoretical approaches to plannning participation (author’s elaboration).

6. Case Studies and Examples: AI in Participatory Urban Planning

Real-world examples demonstrate how AI is transforming participatory urban planning. These examples illustrate both the potential benefits and the challenges of integrating AI into democratic processes.

6.1. Barcelona's Decidim Platform:

Decidim (2023) is a pioneering digital platform used in Barcelona and other cities to facilitate participatory democracy. It uses AI to analyze citizen proposals, identify patterns, and prioritize initiatives based on their popularity, feasibility, and alignment with broader city goals. This allows for more efficient and effective allocation of resources based on citizen preferences.

Decidim's success exemplifies the potential of AI to enhance pluralistic planning by enabling large-scale public consultations and aggregating feedback from diverse groups. The platform's focus on transparency and accountability in prioritizing initiatives directly addresses concerns raised in Section VII about algorithmic bias and the need for explainable AI systems. However, the platform’s effectiveness hinges on citizen engagement; if participation is limited to certain demographics, it fails to meet the ideals of equitable and inclusive participation, raising ethical concerns about the digital divide and potential for marginalization.

6.2. Singapore's Digital Twin:

Singapore (Singapore Government, 2023) utilizes a sophisticated digital twin—a virtual model of the city—to simulate urban changes and assess their potential impacts before implementation. Planners and citizens can use the digital twin to explore scenarios, test policies, and visualize how proposed changes would affect different parts of the city.

Singapore’s digital twin demonstrates the potential of AI-enabled technocratic planning to enhance efficiency and decision-making in urban planning. The visual and interactive nature of the tool could potentially foster a more informed citizenry, aligning with Mill's vision of evidence-based public discourse. However, reliance on data quality, the potential for algorithmic bias, and unequal access are critical factors that limit its ability to achieve truly inclusive and equitable outcomes.

6.3. Amsterdam's AI-Enabled Citizen Engagement:

Amsterdam (Amsterdam City Council, 20230 employs NLP to analyze large volumes of public feedback from various sources, including online forums, surveys, and social media. This allows planners to understand citizen preferences, identify recurring themes, and respond more effectively to public concerns.

Amsterdam’s approach highlights the use of AI to improve participatory planning by providing more comprehensive insights into public opinion than traditional methods. The use of NLP to analyze unstructured data addresses the need for sophisticated data analysis in the context of participatory urban planning. However, potential biases in NLP models and concerns about data privacy are ethical issues that must be addressed to ensure the legitimacy and fairness of the process.

6.4. Korea’s U-City: Combined Technology and Citizen Interaction Efforts

Korea's U-City project integrates cutting-edge digital technologies and AI systems to create real-time data ecosystems that inform urban management. Citizen engagement is a core component, with platforms established for residents to provide feedback on urban services and express their needs.

Korea's U-City demonstrates a comprehensive effort to integrate AI into various aspects of urban governance. However, this approach may risk reinforcing technocratic planning, particularly if citizen feedback is not effectively integrated into decision-making processes. The ethical concerns surrounding data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the potential for surveillance need to be carefully considered to ensure that the initiative truly serves democratic and equitable goals.

The case studies from Barcelona, Singapore, Amsterdam and Korea demonstrate the transformative potential of AI in participatory urban planning, but they also underscore the ethical and equity challenges that arise. As we transition to the next section, we will delve deeper into these critical perspectives, examining how AI can both reinforce and challenge existing power dynamics, as well as the ethical considerations that must be addressed to ensure that AI serves democratic values. By exploring these issues, we can better understand how to navigate the risks and opportunities of AI in urban planning.

7. Ethical and Equity Considerations:

Integrating AI into participatory urban planning raises critical ethical and equity issues that must be addressed proactively. S. U. Noble (2018) warns that the commercialization of information by tech companies often leads to biased and discriminatory outcomes in AI systems. This raises ethical concerns about the use of AI in urban planning, particularly when public decisions are influenced by algorithms designed for profit rather than public good. C. O'Neil (2016) highlights the dangers of using AI systems without transparency or accountability. In urban planning, this underscores the importance of explainable AI (XAI) and mechanisms for public oversight to ensure that AI-driven decisions are fair and equitable. R. Benjamin (2019) calls for the development of 'abolitionist tools'—technologies designed to dismantle systemic inequalities rather than reinforce them. In urban planning, this means prioritizing AI systems that actively promote social justice and equity, rather than perpetuating existing power structures.

This section examines the influence of AI in three key areas where AI's potential to exacerbate existing inequalities or undermine democratic values is most pronounced: algorithmic bias, transparency and accountability, and the digital divide. We will analyze how these challenges manifest in the context of AI-driven urban planning, and explore potential mitigation strategies to ensure that AI serves democratic goals and promotes equitable outcomes for all citizens.

7.1. Bias in AI Algorithms:

AI systems are trained on data, and if that data reflects existing societal biases, then the AI will likely perpetuate those biases. This can lead to unfair or discriminatory allocation of resources and reinforcement of existing inequalities. To mitigate this:

Careful Data Selection: Planners must ensure that the data used to train AI systems is representative of all demographic groups, including marginalized communities and free from biases.

∙ Algorithmic Auditing: Regular auditing of AI algorithms is necessary to identify and correct any biases, using independent third parties to assess fairness and equity.

Human Oversight: Maintain strong human oversight of AI systems to ensure that they are used ethically and responsibly. Engage marginalized communities in the design and testing of AI tools to ensure their needs and perspectives are incorporated.

7.2. Transparency and Accountability:

The use of AI in urban planning must be transparent and accountable. Citizens must understand how AI is used in decision-making and have mechanisms for challenging AI-enabled decisions. This requires:

∙ Explainable AI (XAI): refers to artificial intelligence systems designed to provide clear and understandable explanations for their decisions and actions. XAI aims to make AI decision-making processes transparent, auditable, and accessible to non-experts.

∙ Public Access to Data: Ensure transparency by providing access to the data and algorithms used, subject to privacy protections.

∙ Mechanisms for Appeal: Establish mechanisms for citizens to appeal AI-enabled decisions they believe to be unfair or biased.

7.3. Digital Divide:

The digital divide affects participation in AI-enabled urban planning processes (e.g., unequal access to technology and digital literacy skills, exclusion of marginalized communities). AI tools should be accessible to all citizens, regardless of their technological capabilities or socioeconomic status. Addressing the digital divide requires:

Digital Literacy Training: Provide digital literacy training to ensure that all citizens can participate effectively in AI-enabled planning processes.

Offline Alternatives: Offer offline alternatives to AI-enabled participation tools to ensure that those without internet access can participate.

Multilingual Support: Provide multilingual support for AI-enabled tools to ensure inclusivity for non-native speakers.

Public Access Points: Establish free public Wi-Fi zones and provide access to computers in community centers, especially in underserved areas.

7.4. Other Considerations:

Beyond algorithmic bias and the digital divide, K. Crawford (2021) highlights the hidden labor behind AI systems, such as low-paid workers who label data or moderate content. This labor exploitation raises ethical concerns about the fairness of AI-driven urban planning. Furthermore, Shoshana Zuboff (2019) calls for robust regulatory frameworks to counter the dominance of surveillance capitalism, ensuring that AI serves democratic values rather than corporate interests. V. Eubanks (2018) warns that AI systems often subject marginalized groups to increased surveillance and control, exacerbating social inequalities. In urban planning, this underscores the need for ethical guidelines to ensure that AI is used to empower, rather than police, vulnerable communities. T. Gebru (2021) highlights the environmental and social costs of large AI models, including their significant carbon footprint and the lack of diversity in AI development teams. These factors must be considered when integrating AI into urban planning, particularly to ensure that the benefits of AI are equitably distributed.

8. Risks and Challenges of AI for Participatory Democracy:

The risks and challenges associated with AI in participatory democracy—ranging from apathy and passive citizenship to the concentration of power and algorithmic bias—underscore the need for a cautious and considered approach to AI integration in urban planning. Meredith Broussard (2018) critiques the over-reliance on AI, warning against 'technochauvinism'—the belief that technology is always the best solution to social problems. In urban planning, this underscores the need for a balanced approach that prioritizes human-centered solutions over purely data-driven ones. He highlights the limitations of AI in understanding complex social and human contexts. In participatory democracy, this raises concerns about the risks of replacing human judgment with flawed algorithms, potentially undermining the democratic process.

Apathy and Passive Citizenship

Heavy Reliance on AI: If citizens perceive AI as infallible, they may disengage from participatory processes, assuming that AI will "solve everything."

Erosion of Democratic Debate: AI-enabled consensus-building may suppress dissent, leading to a homogenization of public opinion and a decline in critical discourse.

Concentration of Power

Monopoly of Knowledge: AI systems are often controlled by governments or corporations, creating a new form of power based on data and algorithms. This could marginalize grassroots movements and undermine democratic accountability.

Technocratic Governance: The rise of AI may reinforce technocratic approaches, where decisions are made by experts and algorithms rather than through democratic deliberation.

Bias and Exclusion

Algorithmic Bias (see section 7.3.1): AI systems may perpetuate existing inequalities by favoring dominant groups or excluding marginalized voices.

Digital Divide (see section 7.3.3): Not all citizens have equal access to AI tools, creating a participation gap between technologically literate and illiterate communities.

9. Conclusion: Navigating the Future of Public Participation in Urban Planning

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into urban planning presents a profound and multifaceted transformation of public participation, impacting established political theories, planning ideologies, and citizen engagement strategies in profound ways. While AI offers unprecedented opportunities to enhance democratic values, empower diverse voices, and foster more inclusive and equitable urban development, it simultaneously introduces significant risks and challenges that necessitate proactive and comprehensive mitigation strategies..

The analysis presented in this document reveals a complex interplay between AI's potential and its limitations. AI's capacity to analyze vast datasets, simulate policy outcomes, and visualize complex information empowers citizens to engage in more informed and evidence-based decision-making. However, this potential is severely constrained by the persistent digital divide, algorithmic bias, and the opacity of many AI systems. These factors exacerbate existing inequalities, undermine informed consent, and concentrate power in the hands of a technologically-savvy elite. While AI tools can potentially democratize expertise, counteracting democratic elitism, the risk of reinforcing existing biases and undermining transparency remains substantial.

The case studies examined illustrate both the potential benefits and significant challenges of AI integration into urban planning. Digital platforms like Decidim showcase the potential of AI to improve transparency and inclusivity, but also highlight the concerns surrounding algorithmic bias and accessibility. Digital twins, though offering powerful visualization tools, are dependent on data quality and digital literacy. Amsterdam's AI-enabled engagement, while effectively synthesizing public feedback, also reveals the difficulty of ensuring accurate reflection of diverse opinions.

Finally, the ethical and equity considerations discussed throughout this document underscore the importance of proactive measures to mitigate the risks of AI in urban planning. Addressing algorithmic bias, ensuring transparency and accountability, and bridging the digital divide are paramount to harnessing AI's potential benefits while mitigating its risks. A cautious and considered approach, prioritizing transparency, accountability, and inclusivity, is essential for ensuring that AI serves democratic values and promotes inclusive and equitable urban development. The future of participatory urban planning requires navigating this complex landscape carefully, ensuring that AI is employed responsibly and ethically to enhance, not undermine, democratic values and promote equitable outcomes for all citizens.

References

- AI for Social Good (2023). AI Tools for Advocacy and Social Justice. Available at: https://ai4socialgood.org/ [Accessed 10 Oct. 2023].

- Almond, G. A. and Verba, S. (1963). The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Amsterdam City Council (2023). AI-enabled Citizen Engagement. Available at: https://www.amsterdam.nl/ [Accessed 10 Oct. 2023].

- Arnstein, S. R. (). ‘A Ladder of Citizen Participation.’ Journal of the American Institute of Planners 1969, 35, pp. 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachrach, P. (1962). ‘Elite Consensus and Democracy’. The Journal of Politics, Vol. 24. No 3, 62. 19 August.

- Bahm, A. J. (1968). Causation. University of New Mexico Press.

- Broussard, M. (2018). Artificial Unintelligence: How computers misunderstand the world. MIT Press.

- Benjamin, R. (2019). Race After Technology: Abolitionist tools for the new Jim Code. Polity.

- Benwell, M. (1980). ‘Public Participation in Planning – A Research Report’. Long Range Planning vol. 13, 80. 19 August.

- Breines, W. Community and organization: the new left and Michels “Iron Law”’. Social Problems 1980, 27, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R. (1973). Citizen Participation in the Urban Policy Process. Richard Cole, Lexington Books, Massachusetts.

- Crawford, K. (2021). The Atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

- Dahl, R.A. (1966). ‘Further reflections on “the elitist theory of democracy”’. American Political Science Review, cambridge.org.

- Dahrendorf, R. (1958). ‘Toward a theory of social conflict’. Journal of Conflict Resolution, journals.sagepub.com.

- Dahrendorf, R. (1959). Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Davidoff, P. Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning. ’ Journal of the American Institute of Planners 1965, 31, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decidim (2023). Decidim: Participatory Democracy Platform. Available at: https://decidim. org/ [Accessed 10 Oct. 2023].

- Eubanks, V. (2018). Automating Inequality: How high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor. St. Martin's Press.

- Gebru, T., Bender, E. M., McMillan-Major, A., & Shmitchell, S. (2021). On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can language models be too big?. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 610–623).

- Geddes, P. (1915). Cities in Evolution. Williams and Norgate, London 1949.

- Gutch, R. , Spires, R., Tayler, M. (1979). ‘Views of Participation’. Planning Studies No 4, Polytechnic of Central London, Planning Unit, London.

- Hain, P. (1980). Neighbourhood Participation. Temple Smith ltd, London.

- Kim, J. , Kim, S. and Lee, H. U-City: The Future of Urban Planning in Korea.’ Journal of Urban Technology 2020, 27, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Klosterman, R.E. (1979). ‘Planning as a Social Engineering’. Economic Context, Emerging Coalitions and Progressive Planning Rules, conference, Cornell University, Dept. of City and Regional Planning, Ithaca, N.Y., 79. 19 April.

- Lalenis, K. (1993). ‘Public Participation Strategies in Urban Planning in Greece after the “Urban Reconstruction Operation (EPA) 82-84”. Comparison of Theory and Practice’. PhD dissertation, University of Westminster, Department of Urban Planning & Development, London, UK.

- Lalenis, K. , Smaniotto Costa, C. , Menezes, M., Ivanova-Radovanova, P., Ruchinskaya, T., Bocci, M. ‘Planning Perspectives and Approaches for Activating Underground Built Heritage’. Going Underground. Making Heritage Sustainable, Special Issue, Sustainability 2021, 13, 10349; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, K. and Engels, F. (1848). The Communist Manifesto, London: Workers Educational Association.

- Mill, J. S. (1861). Considerations on Representative Government, London: Parker, Son, and Bourn.

- Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

- O’Connor, J. (1978). The Democratic Movement in the United States, New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- O'Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of Math Destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. Crown.

- Ober, J. (1989). Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Pramita, K. , Manafe, L. A. (2022). ‘Personal selling implementation and AIDA model; Attention, interest, desire, action’. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Business Development 2022, 5, 487–494. [Google Scholar]

- Singapore Government (2023). Digital Twin Initiative. Available at: https://www.smartnation. gov.sg/ [Accessed 10 Oct. 2023].

- Smith, R. W. A theoretical basis for participatory planning’. Policy Sciences 1973, 4, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedberg, R. (2013). ‘Joseph A. Schumpeter: his life and work’. Books.google.com.

- Thornley, A. (1977). ‘Theoretical Perspectives on Planning and Participation’. Progress in Planning, vol. 7, Part 1.

- Wright Mills, C. (1956). ‘The power elite’. Oxford University Press.

- Yukubousky, R. (1979). ‘Effective Participation: Public Search for “Democratic Efficiency”’. Transportation Research Board, Annual Meeting, Washington DC, 79. 19 January.

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs.

- Zuckerman, A. ‘The Concept “Political Elite”: Lessons from Mosca and Pareto’. The Journal of Politics 1977, 39, 324–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).