1. Introduction

Plant diseases, especially fungal diseases, contribute significantly to plant productivity and yield loss. About 30% of food loss is caused by plant diseases (Ajala et al., 2020), with more than 70% of the loss caused by fungi (Agrios, 2005). Consequently, an increase in the world’s population has led to a surge in the use of chemicals to protect crops and meet the demand for food. Unfortunately, environmental issues limit using chemicals to control plant diseases (Wolf and Verreet, 2008), resulting in employing organic compounds from plants to control plant fungal diseases (Dosumu et al., 2019).

Powdery mildew has historically been an important fungal disease of watermelons globally, including South Africa (Brisbois et al., 2018). During growth and developmental stage of watermelons, powdery mildew is commonly a yield limiting factor (Cui et al., 2021). Powdery mildew infections are not confined to cucurbit species, but have jumped to other crop species like mushmelons, honeydew, pumpkins, squash, and gourds (Roberts and Kucharek, 2005). This disease leads to reduced yield of affected crops by limiting growth of plants and causing early loss of leaves. Thus, crop yield reduction is due to the rate of fungal infection and the spread rate on infected plants (Mossler and Neshelm, 2005). Podosphaera xanthii is the most common and important fungus on watermelon as it spreads faster and is more persistent than other fungi (Jahn et al., 2002). There is also an issue of resistance by pathogens to fungicides. McGrath (2001) showed the resistance of powdery mildew to the commonly used fungicides, benomyl and triadimefon. Moreover, there is much interest in finding alternatives that are environmentally friendly and safe to biodiversity (Chowdhury et al., 2024).

Since it was discovered that some plants produce chemicals or enzymes that can fight diseases (Balouiri et al., 2016), they have become good targets of investigation to control plant infections, including powdery mildew. The antifungal activity of plants reported can be attributed to the presence of secondary metabolites like tannins, phenolics, flavonoids, saponins, alkanoids and terpenoids (Reynolds et al., 1996) and chitinase enzyme (destroys the cell wall of the fungi) (Silva, 2016). Wurns (1999) showed that terpenoids disrupt the membrane of microorganisms, tannins lead to enzyme inhibition, while flavonoids inactivate enzymes and destroy the cell wall.

Campuloclinium macrocephalum, pompom weed, is one of the potential sources of secondary metabolites and useful bioactive compounds (McGaw et al., 2022). Pompom weed was introduced into South Africa during the early 1960s as an ornamental plant and has become a significant weed that threaten the grasslands and wetlands of South Africa (Zachariades et al., 2021). Citrillus lanatus, watermelon, is said to have originated from the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa (Malambane et al., 2023). With time, it became popular in most African countries. Moreover, the cultivation of watermelon spread to other countries like America and Asia (Kousik et al., 2019). The current study was designed to investigate using pom-pom weed extract to control powdery mildew on watermelons. This is done to address food security and sustainability in developing countries, by developing cheaper and more environmentally friendly alternatives to synthetic applications.

2. Materials and Methods

Bitter watermelon (Citrullus lanatus var. citroides) seeds were planted in a glass house. Plastic pots of 25 cm (diameter) were filled with vermiculite and three seeds were planted in each pot. They were arranged in a randomized block design of 1.0 m

× 0.5 m spacing. Fresh Hoagland nutrient solution was prepared weekly and provided to the plants. Three weeks after germination, when the seedlings had developed two leaves each, two plants were removed, and the healthiest ones were retained in each pot. Pom-pom weed shoots with leaves were collected from Tzaneen, Limpopo Province, where they occur alongside the road.

2.1. Buffered Extraction

Fresh leaves and stems of the pom-pom weed were washed with distilled water, then cut into small pieces of about 0.25 cm. The phosphate buffer (pH = 7.0) was prepared for fresh extraction. A ratio of 1 g:10 ml of plant material and phosphate buffer was used for the extraction (Seddon and Schmitt, 1999). A 100 g of pom-pom weed was put into the conical flask with 1000 ml of phosphate buffer being poured into the flask. The mixture was homogenized with a homogenizer until thoroughly done, with the aim of extracting chitinase enzyme. Whatman’s no.1 filter paper was used to filter homogenized mixture into another conical flask. Then, the filtrate was poured into a 1-liter bottle and stored in the refrigerator for future use.

2.2. Dry Extraction

The pompom weed leaves and stems were dried in the laboratory at ambient temperature. When completely dry, the material was ground into a powder. A 20 g dry powder was poured into a 500 ml conical flask. Then, 200 ml of 100% acetone was added into that flask. The flask was shaken on a horizontal shaker at 200 rpm for 2 hours. The mixture was filtered through Whatman’s No. 1 filter paper, the residue was washed three times with 50 ml of acetone. The mixture was transferred into a pre-weighed glass petri dish and dried under a draught of air in the fume chamber overnight. Finally, the extract was dried at 60ºC for 1 hour. Thereafter, the petri dish was weighed to determine the extraction yield.

2.3. Preparation of Homemade Fungicide

The homemade fungicide consisted of mixing 100 ml distilled water, a quarter tablespoon of baking powder, and a drop of liquid soap. To each mixture, 0.01 and 0.02 g of the dry plant extract were added to prepare, respectively 0.1 and 0.2 mg/ml plant extract fungicide.

2.4. Preparation of Commercial Fungicide

Distilled water (100 ml) was mixed with 1 ml of commercial fungicide (lime sulfur) in a 500 ml beaker, according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

2.5. Treatments

Treatment started at the two-leaf stage of development. There were five treatments in triplicate, with 100 ml spraying per week. Fresh fungicide preparations were made every week just before spraying the plants. Plants were sprayed once a week for five weeks, and data were collected after week six.

Treatment A: negative control (no treatment).

Treatment B: positive control (plants were sprayed with a commercial fungicide). Treatment C: plants were sprayed with the buffered enzyme extract.

Treatment D: plants were sprayed with the acetone plant extract (0.1 mg/ml).

Treatment E: plants were sprayed with the acetone plant extract (0.2 mg/ml).

2.6. Evaluation of Efficiency

Percentage coverage of powdery mildew on leaf surfaces was determined using BioLeaf software. A camera with BioLeaf software was used to take pictures of the leaves, and then the total percentage coverage was determined. Only the upper surfaces of the leaves were measured. The efficiency of treatments was statistically analysed using one-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) using SPSS software package (ver. 25).

3. Results and Discussion

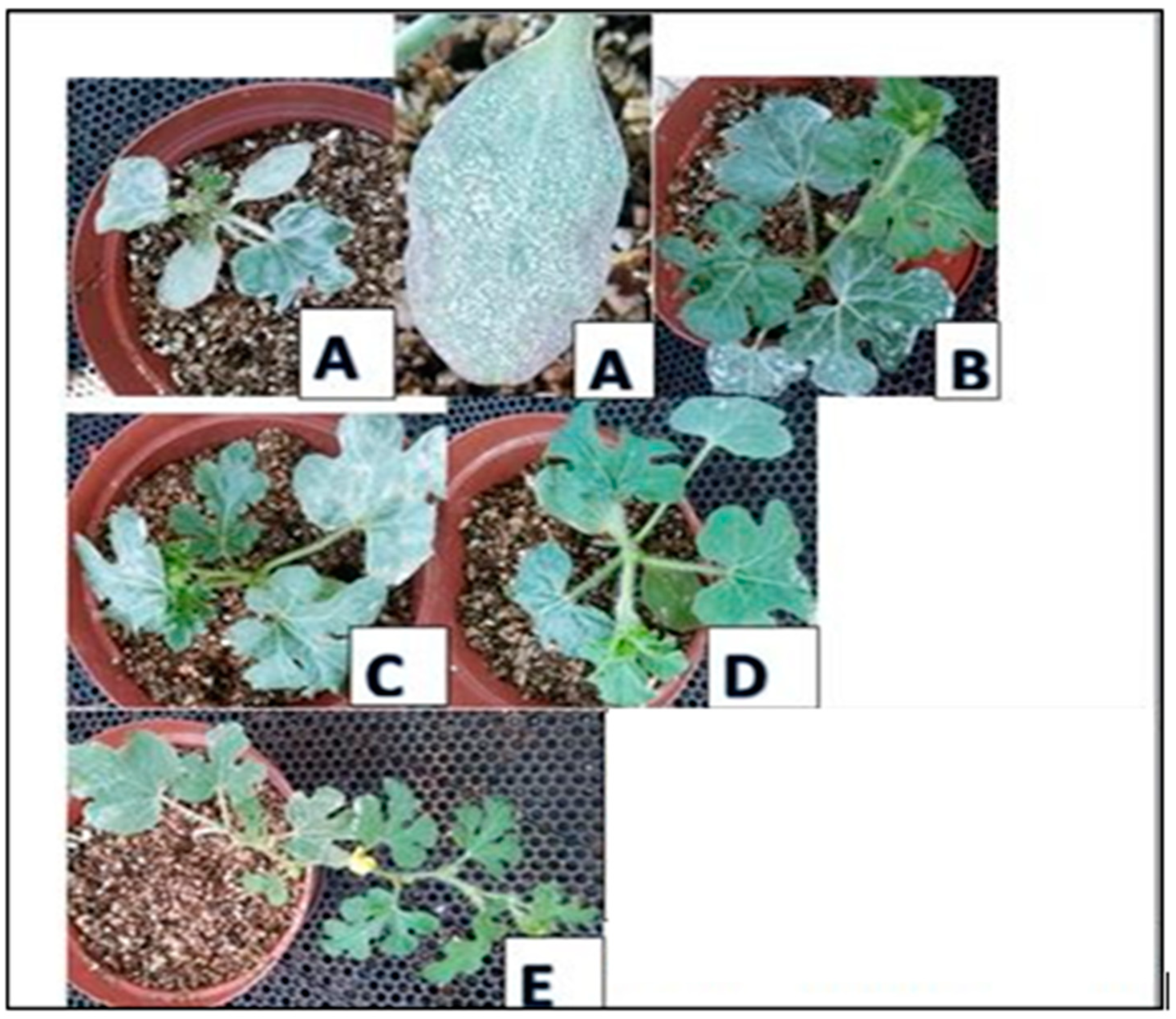

There was no sign of powdery mildew (

Podosphaera xanthii) on plants that were sprayed with the commercial fungicide in Treatment B (0%) (

Table 1). This is supported by Konstantinidou-Doitsinis (1998) who noted that chemical fungicides are effective for controlling powdery mildew. However, the plants contained residues of fungicides that persisted on the leaves (

Figure 1). This, therefore, supports Fernandez-Aparicio et al. (2009) and Ali et al. (2021) who showed that chemical fungicides are now becoming of less interest as they impose residues on plant parts, which can be harmful to humans and animals. In treatment A, the plants were the most affected (77.9%), followed by plants of Treatment C (13.1%), then Treatment E (7.6%). Plants of Treatment D were the least affected (2.1%), second after plants of Treatment B.

Table 1.

Number of leaves and infection percentage.

Table 1.

Number of leaves and infection percentage.

| Treatments |

Number of leaves |

Average no. of

Leaves |

Infection percentage |

Average infection (%) |

Average infection reduction

(%) |

| Treatment A |

2 |

2 |

83.67 |

77,87 |

22,13 |

| 2 |

96.67 |

| 2 |

53.28 |

| Treatment B |

9 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

| 8 |

0 |

| 7 |

0 |

| Treatment C |

6 |

4 |

1.17 |

13,1 |

86.9 |

| 3 |

29.42 |

| 3 |

8.7 |

| Treatment D |

8 |

7 |

2.19 |

2.05 |

97.95 |

| 7 |

3.1 |

| 6 |

0.85 |

| Treatment E |

7 |

6 |

9.43 |

7.56 |

92.44 |

| 6 |

9.34 |

| 5 |

3.92 |

Figure 1.

Plants showing rates of infections with Powdery mildew. A. leaves are already withering due to infestation. B. white spots are fungicide residues, not powdery mildew. C-E. Spread of infestation of powdery mildew.

Figure 1.

Plants showing rates of infections with Powdery mildew. A. leaves are already withering due to infestation. B. white spots are fungicide residues, not powdery mildew. C-E. Spread of infestation of powdery mildew.

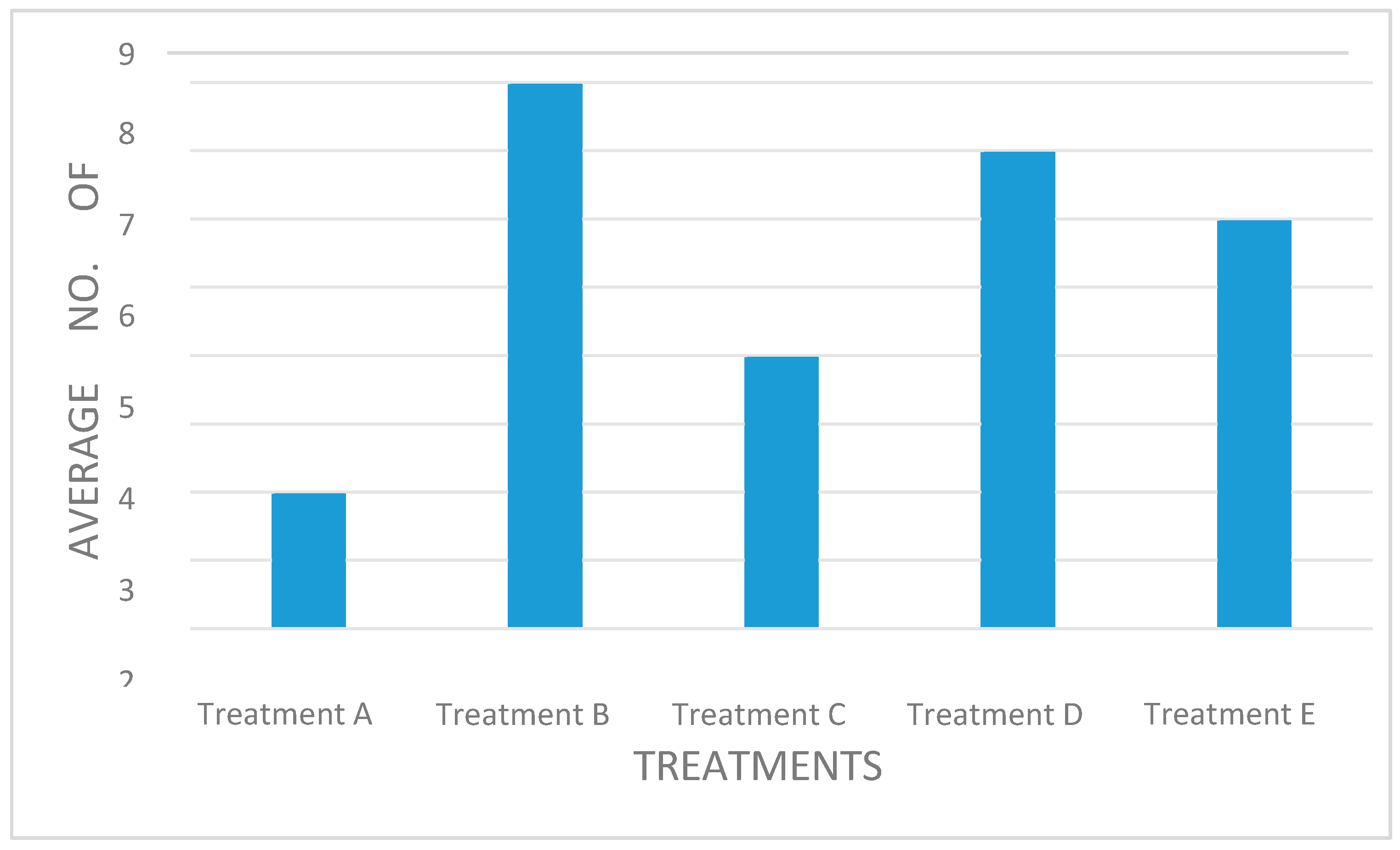

Treatment B (with no sign of powdery mildew) produced the highest average number of leaves (8) and treatment A (with the highest percentage of disease) produced the least number of leaves (2) (

Figure 2). This is indicative that the higher the infection, the less the production of leaves. This might be due to the powdery mildew reducing the overall photosynthesis rate on existing leaves (Tian et al., 2024), thus decreasing the production and development of new leaves.

Figure 2.

Average number of leaves produced per plant treatment.

Figure 2.

Average number of leaves produced per plant treatment.

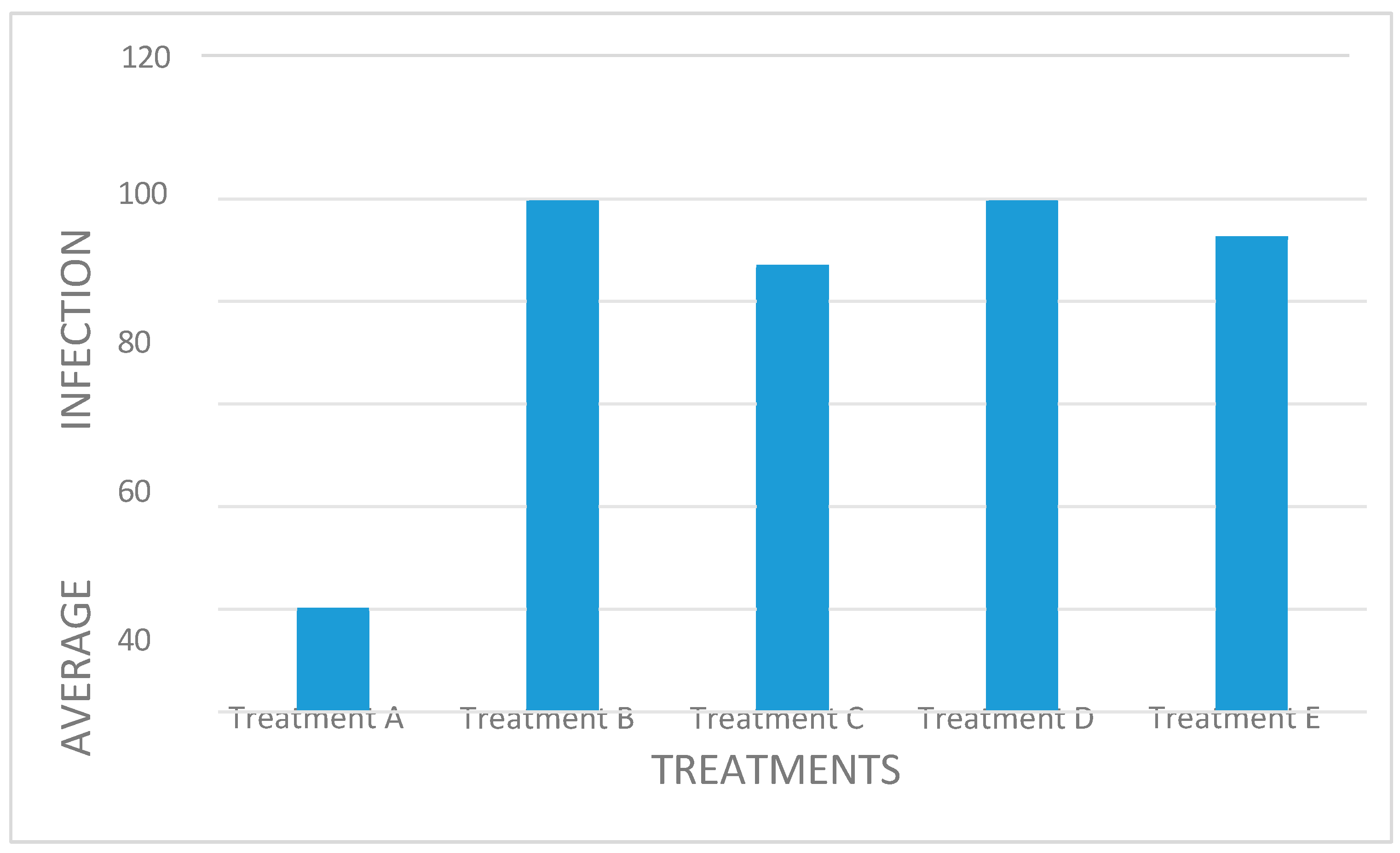

One-way ANOVA showed that the five treatments were significantly different (p = 0.000). Analysis of Variance of multiple comparison showed that treatment A was significantly different to all treatments. The p-value was 0.000 for treatment A compared to the other treatments. There was no statistical difference amongst the other treatments (treatments B, C, D and E).

All treatments had an impact in limiting the growth and spread of powdery mildew (

Figure 3). The dry extract treatments (Treatments B and D) were the most effective fungicide. Treatment C (buffered extract) had a lower effect, which can be attributed to the fact that the plant material was not ground, only cut into smaller pieces. Eloff (1998) showed that there was a higher rate of extraction from particles that were very fine than those acquired after 24h in a shaking machine with only a small amount of fine ground material. Therefore, plant material has to be ground to powder form, whether dry or wet, to increase the surface area to extract antimicrobial compounds and therefore increasing the extraction rate. Therefore, the ability of pom-pom weed extracts to control powdery mildew can be due to the production of one or more of these secondary metabolites (observed from the acetone extract treatments) and the ability to produce chitinase enzyme (observed from the buffered extract treatment).

Figure 3.

Average powdery mildew infection reduction.

Figure 3.

Average powdery mildew infection reduction.

The results obtained for treatment E are in concord with the ones acquired by Seddon and Schmitt (1999) whereby they used medicinal plants to control powdery mildew on squash plants. This is due to the phytochemical properties available in the plant extract (McGaw et al., 2022). However, baking powder alone was considered not effective in controlling powdery mildew and needs to be mixed with neem oil (Otten, 1997). Our study shows that pompom weed extracts are effective in controlling powdery mildew as neem oil was omitted in the homemade fungicide’s ingredients of the study.

Author Contributions

E. Molwantoa carried out laboratory and field work experiments, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MJ Potgieter assisted in the finalisation of the manuscripts. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors received funding from the National Research Foundation.

Data availability statement

The authors verify that the data from which the study’s conclusions are based is available.

Disclaimer

The authors are only responsible for the views and opinions shared and therefore do not reflect any affiliated agency of the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the late Dr P.W. Mokwala who designed the study and assisted with laboratory experiments. Dr B.A. Egan is thanked for the identification and collection of pompom weed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors affirmed that there is no competing interest.

References

- Agrios, G.N. 2005. Plant Pathology. Fifth edition, Academic Press. New York. 633.

- Ajala, T.O. , Olusola, A.J. and Odeku, O.A. Antimicrobial activity of Ficus exasperata (Vahl) leaf extract in clinical isolates and its development into herbal tablet dosage form. Journal of Medicinal Plants for Economic Development 2020, 4, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. , Ullah, M. I., Sajjad, A., Shakeel, Q., Hussain, A. Environmental and health effects of pesticide residues. Sustainable agriculture reviews 48: Pesticide Occurrence, analysis and Remediation 2021, 2, 311–336. [Google Scholar]

- Balouiri, M. , Sadiki, M., Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis 2016, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brisbois, B.W. , Harris, L., Spiegel, J.M. Pesticide exposure in southwestern Ecuador's banana industry Antipode. Political Ecologies of Global Health 2018, 50, 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, S.K. , Banerjee, M., Basnett, D., Mazumdar, T. Natural pesticides for pest control in agricultural crops: An alternative and eco-friendly method. Plant Science Today 2024, 11, 433–450. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H. , Zhu, Z., Ding, Z., Lv, Y., Sun, L., Luan, F., Wang, X. First report of powdery mildew caused by Podosphaera xanthii race 1 on watermelon in China. Journal of Plant Pathology 2021, 103, 1029–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosumu, O.O. , Ajetumobi, O.O., Omole, O.A., Onocha, P.A. Phytochemical composition and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Pergularia daemia. Journal of Medicinal Plants for Economic Development 2019, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Eloff, J.N. A sensitive and quick microplate method to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration of plant extracts for bacteria. Planta Medica 1998, 64, 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Aparicio, M. Parts, E. Emeran, A.A., Rubiales, D. Characterization of resistance mechanisms to powdery mildew (Erysiohe betae) in beet (Beta vulgaris). Phytopathology 2009, 99, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahn, M. , Munger, H.M., McCreight, J.D. 2002. Breeding Cucurbit Crops for Powdery Mildew Resistance. In Bélanger R, WR Bushnell, AJ Dik, TLW Carver, eds. The Powdery Mildews. A Comprehensive Treatise. The American Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, Minnesota, 239-248.

- Konstantinidou-Doltsinis, S. , Schmitt, A. Impact of treatment with plant extracts from Reynoutria sachalinensis (F Schmidt) Nakai on intensity of powdery mildew severity and yield in cucumber under high disease pressure. Crop Protection 1998, 17, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousik, C.S. , Ikerd, J.L., Mandal, M. 2Relative susceptibility of commercial watermelon varieties to powdery mildew. Crop Protection 2019, 125, 104910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malambane, G. , Madumane, K. , Sewelo, L.T., Batlang, U. Drought stress tolerance mechanisms and their potential common indicators to salinity, insights from the wild watermelon (Citrullus lanatus): A review. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 13, 1074395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McGaw, L.J. , Omokhua-Uyi, A.G., Finnie, J.F., Van Staden, J. Invasive alien plants and weeds in South Africa: A review of their applications in traditional medicine and potential pharmaceutical properties. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2022, 283, 114564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, M.T. , Shishkoff, N. Resistance to triadimefon and benomyl: Dynamics and impact on managing cucurbit powdery mildew. Plant Disease 2001, 85, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mossler, M.A. and Nesheim N.O. 2005. Florida Crop/Pest Management Profile: Squash. Electronic Data Information Source of UF/IFAS Extension (EDIS).

- Otten, P. 1997. Can kitchen products control powdery mildew? Northland Berry News. Fall. 20.

- Reynold, J.E. , Martindale, K.B. 1996. The Extra Pharmacopoeia. 31st edition. Published by the Council of Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 885.

- Roberts, P. , Kucharek, T. 2005. Florida Plant Disease Management Guide: Watermelon. Electronic Data Information Source of UF/IFAS Extension, PDMG-V3-55.

- Seddon, B. , Schmitt, A. 1999. Integrated biological control of fungal plant pathogens using natural products. Intercept Limited, 423-428.

- Silva, R.A. , Liberio, S.A., Amaral, F.M., Nascimento, F.R.N., Torres, L.M.B., Neto, V.M. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of Anacardium occidentale L. flowers in comparison to bark and leaves extracts. Journal of Biosciences and Medicine 2016, 4, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, H. , Ghanadian, M., Mostowfizadeh-Ghalamfarsa, R. Spinach flavonoid-rich extract: Unleashing plant defense mechanisms against cucumber powdery mildew. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2024, 41, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M. , Yu, R., Yang, W., Guo, S., Liu, S., Du, H., Liang, J., Zhang, X. Effect of Powdery Mildew on the Photosynthetic Parameters and Leaf Microstructure of Melon. Agriculture 2024, 14, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, P.F. , Verreet, A. Quaternary IPM (integrated pest management) - concept for the control of powdery mildew in sugar beets. Plant Disease 2008, 73, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wurms, K.; Labbe, C.; Benhamou, N. , Belanger, R.R. Effect of Milsana and benzothiazol on the ultrastructure of powdery mildew haustoria on cucumber. Phytopathology 1999, 89, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachariades, C. , Van Der Westhuizen, L., Heystek, F., Dube, N., McConnachie, A.J., Nqayi, S.B., Dlomo, S.I., Mpedi, P., Kistensamy, Y. Biological control of three Eupatorieae weeds in South Africa: 2011–2020. African Entomology 2021, 29, 742–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).