Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

28 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Numbers

2.2. Faecal Viable Numbers

2.3. Genomic DNA Extraction and Quantification

2.4. Genomic Analysis

2.5. Analysis of the Faecal Microbiota by 16S rDNA

2.5.1. Sequencing and Initial Processing

2.5.2. Bacterial Taxonomic Analysis

2.5.3. Differential Abundance

2.5.4. Diversity Measures

2.5.5. Neonatal Community State Type Analysis

2.5.6. Microbial Networks

2.6. Analysis of the Faecal Microbiota by Metagenomics

2.6.1. Sequencing and Initial Processing

2.6.2. Microbial Profiling and Gene Prediction

2.6.3. Antibiotic Resistance Gene, Mobile Genetic Element and Metabolic Pathway Annotation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

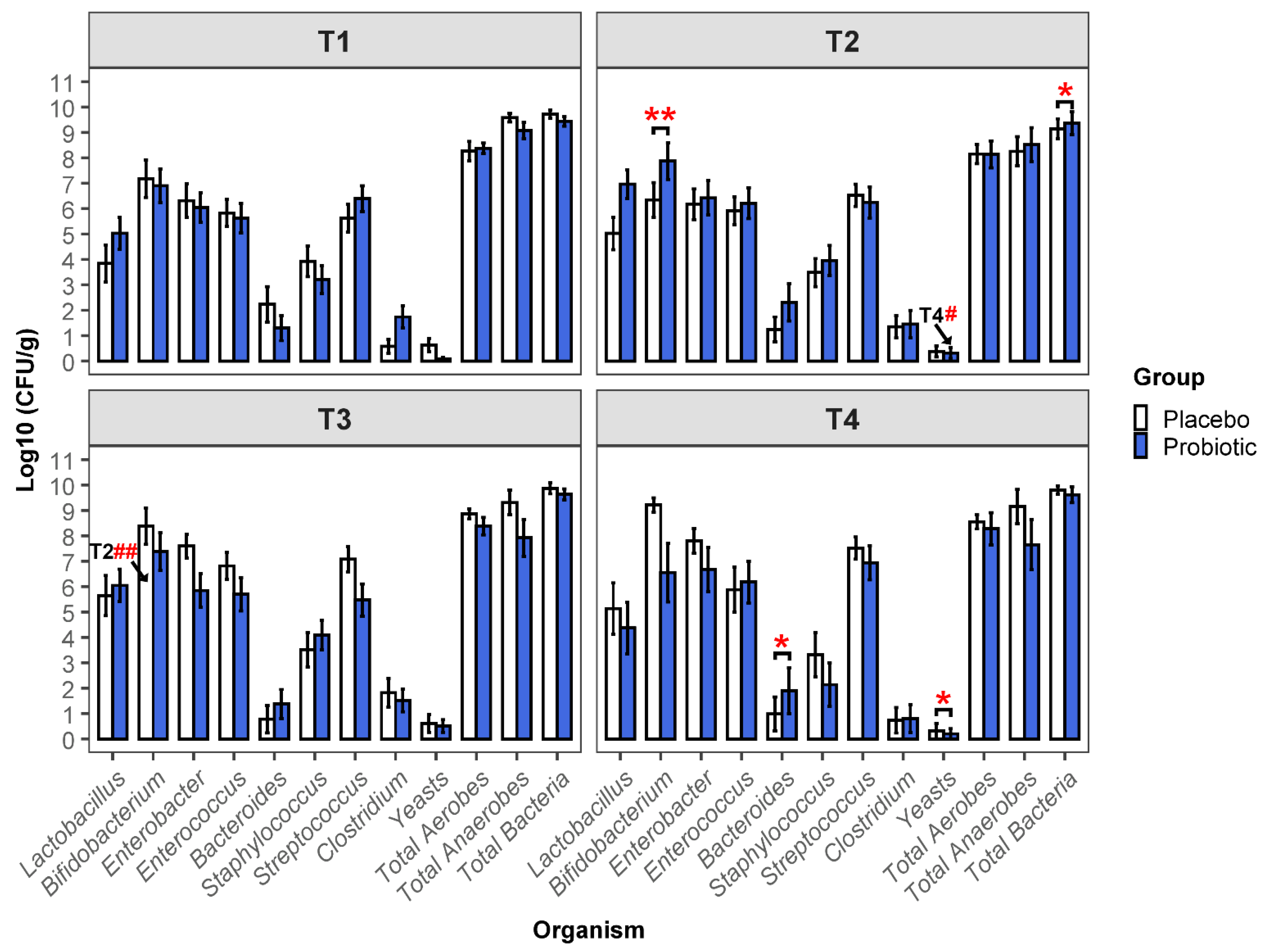

3.2. Viable Microbial Numbers

3.3. 16S Analysis of Faecal Microbiota

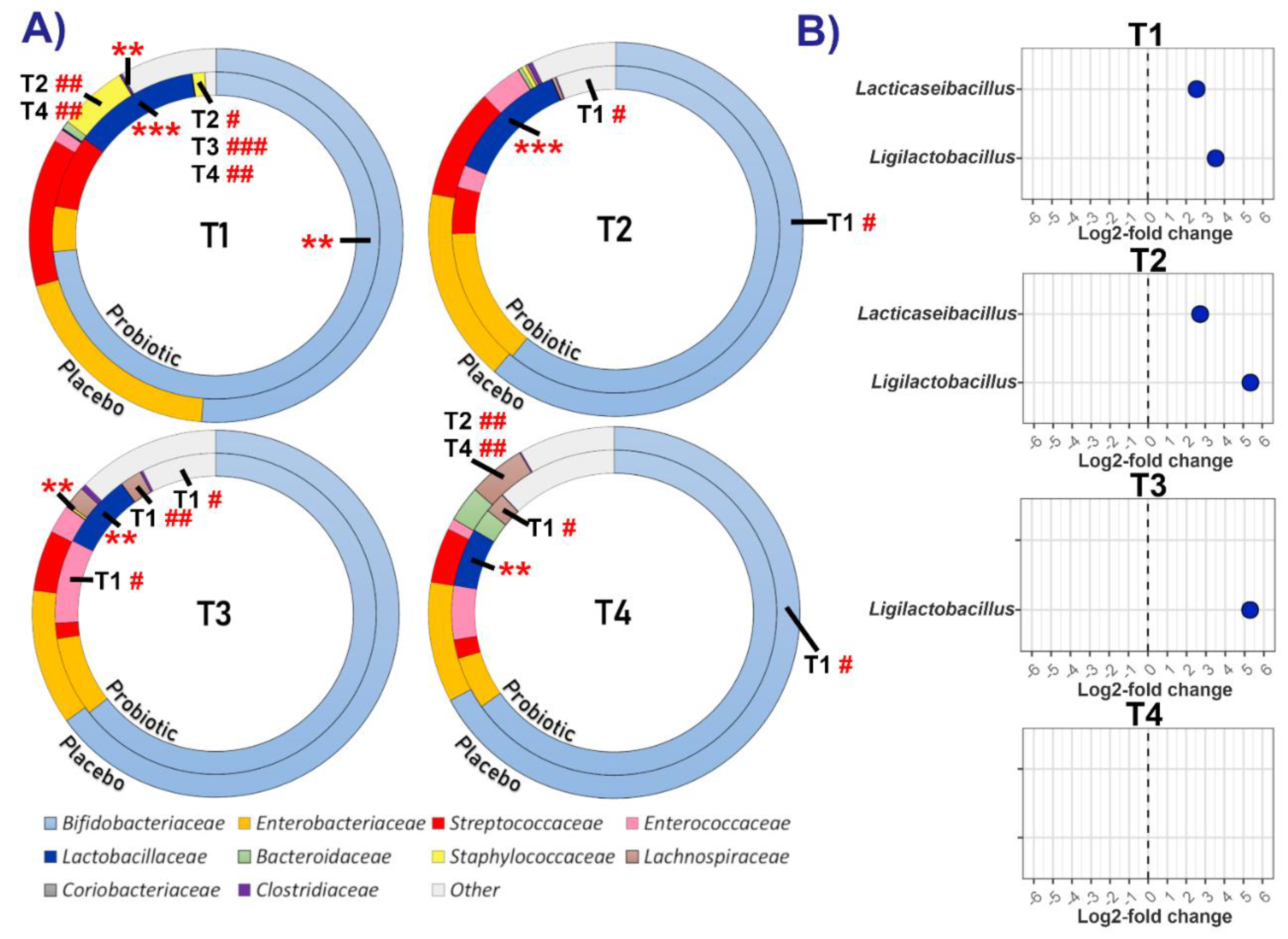

3.3.1. Relative and Differential Abundance of Bacterial Taxa

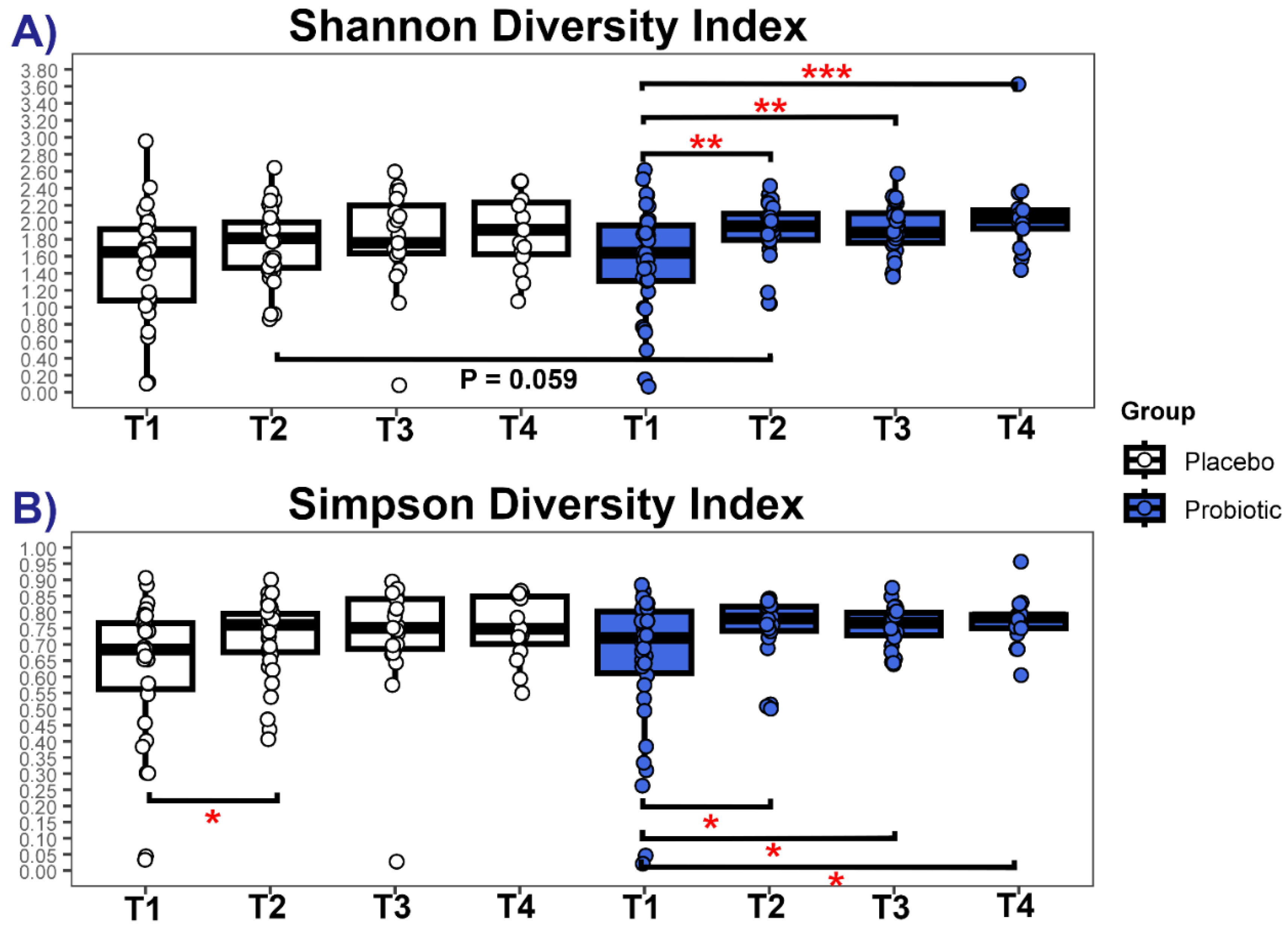

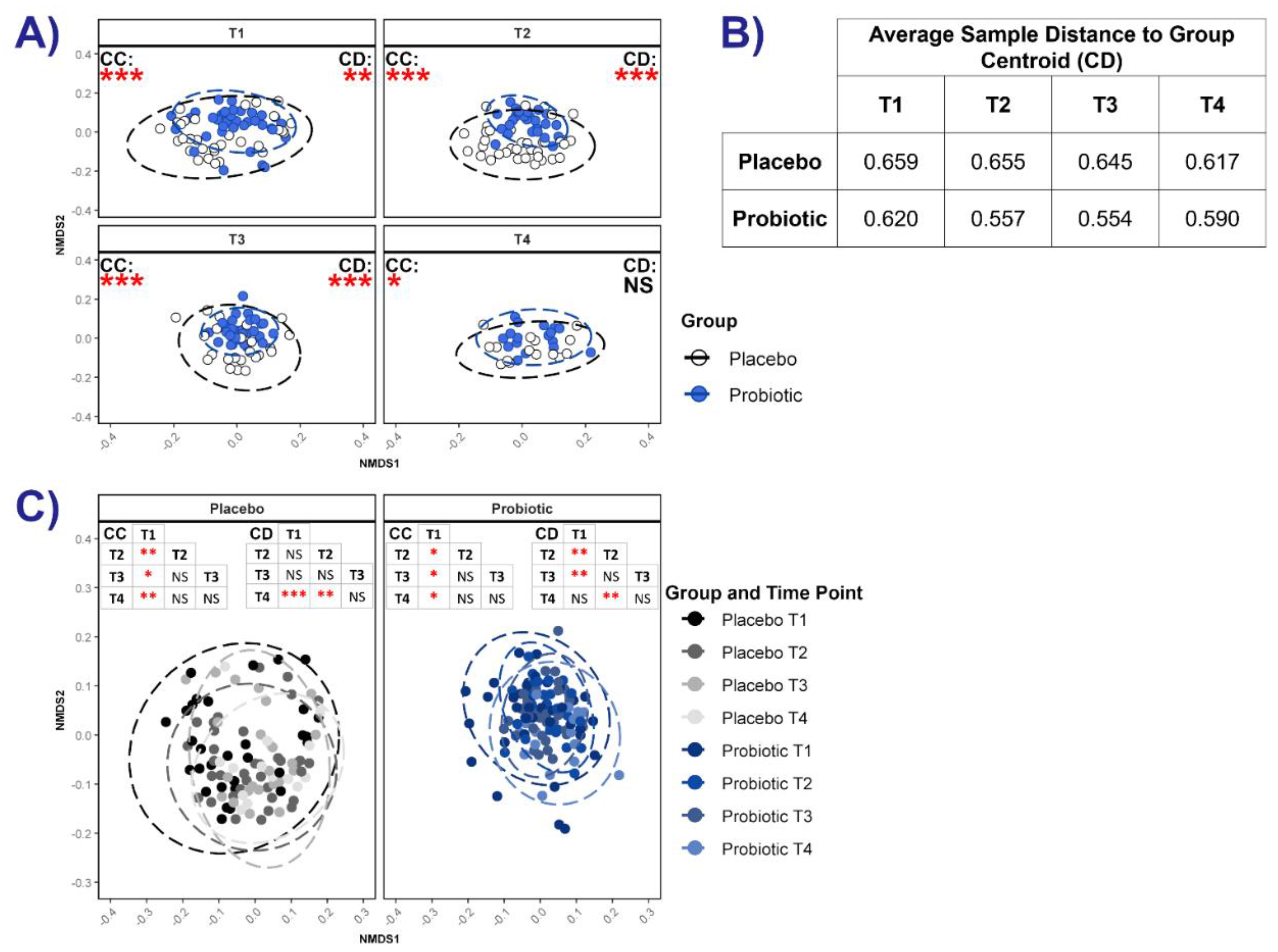

3.3.2. Diversity Measures

3.3.3. Neonatal Community State Type Analysis

3.3.4. Microbial Networks and Keystone Taxa

3.4. Metagenomic Analysis

3.4.1. Antibiotic Resistance Gene (ARG) and Mobile Genetic Element (MGE) Abundance

3.4.2. Differentially Abundant Metabolic Pathways

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Expansion |

| PROBAT | Probiotics in the Prevention of Atopy in Infants and Children |

| SP | Starting Point |

| EP | Ending Point |

| CST | Community State Type |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| AOR | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| CFU | Colony Forming Units |

| gDNA | Genomic DNA |

| ASV | Amplicon Sequence Variant |

| 16S rDNA | 16S Ribosomal DNA |

| CLR | Centre-Log-Ratio |

| ARG | Antibiotic Resistance Gene |

| MGE | Mobile Genetic Element |

| ORF | Open Reading Frame |

| RPKM | Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads |

| PCoA | Principal Coordinates Analysis |

| NMDS | Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling |

| JSD | Jensen-Shannon Divergence |

| GLMM | Generalised Linear Mixed Model |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| DADA2 | Divisive Amplicon Denoising Algorithm 2 |

| NCIMB | National Collection of Industrial, Food and Marine Bacteria |

| CARD | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database |

| RGI | Resistance Gene Identifier |

| DESeq2 | Differential Expression Sequencing version 2 |

| HUMAnN | The HMP Unified Metabolic Analysis Network |

| MetaCyc | Metabolic Pathway Database |

| CHOCOPhlAn | A pan-genome database used with MetaPhlAn |

| NetCoMi | Network Construction and Comparison for Microbiome Data |

References

- Lynch, S.V.; Pedersen, O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durack, J.; Lynch, S.V. The gut microbiome: Relationships with disease and opportunities for therapy. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Zmora, N.; Adolph, T.E.; Elinav, E. The intestinal microbiota fuelling metabolic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gensollen, T.; Iyer, S.S.; Kasper, D.L.; Blumberg, R.S. How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science 2016, 352, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, C.; Duranti, S.; Bottacini, F.; Casey, E.; Turroni, F.; Mahony, J.; Belzer, C.; Delgado Palacio, S.; Arboleya Montes, S.; Mancabelli, L.; et al. The First Microbial Colonizers of the Human Gut: Composition, Activities, and Health Implications of the Infant Gut Microbiota. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2017, 81, e00036-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanidad, K.Z.; Zeng, M.Y. Neonatal gut microbiome and immunity. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2020, 56, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beller, L.; Deboutte, W.; Falony, G.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Tito, R.Y.; Valles-Colomer, M.; Rymenans, L.; Jansen, D.; Van Espen, L.; Papadaki, M.I.; et al. Successional Stages in Infant Gut Microbiota Maturation. mBio 2021, 12, e01857-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, B.; Salonen, A.; Ponsero, A.J.; Jokela, R.; Kolho, K.-L.; De Vos, W.M.; Korpela, K. Gut microbiota wellbeing index predicts overall health in a cohort of 1000 infants. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenhav, L.; Fehr, K.; Reyna, M.E.; Petersen, C.; Dai, D.L.Y.; Dai, R.; Breton, V.; Rossi, L.; Smieja, M.; Simons, E.; et al. Microbial colonization programs are structured by breastfeeding and guide healthy respiratory development. Cell 2024, 187, 5431–5452.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wopereis, H.; Oozeer, R.; Knipping, K.; Belzer, C.; Knol, J. The first thousand days - intestinal microbiology of early life: Establishing a symbiosis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2014, 25, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saturio, S.; Nogacka, A.M.; Alvarado-Jasso, G.M.; Salazar, N.; De Los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; Gueimonde, M.; Arboleya, S. Role of Bifidobacteria on Infant Health. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, E.C.; Monaco, C.L.; Insel, R.; Järvinen, K.M. Gut microbiome in the first 1000 days and risk for childhood food allergy. Ann. Allergy. Asthma. Immunol. 2024, S1081120624001522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Chung, J.; Battaglia, T.; Henderson, N.; Jay, M.; Li, H.; Lieber, A.D.; Wu, F.; Perez-Perez, G.I.; Chen, Y.; et al. Antibiotics, birth mode, and diet shape microbiome maturation during early life. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassour, M.; Vatanen, T.; Siljander, H.; Hämäläinen, A.-M.; Härkönen, T.; Ryhänen, S.J.; Franzosa, E.A.; Vlamakis, H.; Huttenhower, C.; Gevers, D.; et al. Natural history of the infant gut microbiome and impact of antibiotic treatment on bacterial strain diversity and stability. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Garcia-Mauriño, C.; Clare, S.; Dawson, N.J.R.; Mu, A.; Adoum, A.; Harcourt, K.; Liu, J.; Browne, H.P.; Stares, M.D.; et al. Primary succession of Bifidobacteria drives pathogen resistance in neonatal microbiota assembly. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 2570–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J.; Lu, W.; Chen, W. Gut Microbiota, Probiotics, and Their Interactions in Prevention and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis: A Review. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 720393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, H.; Skevaki, C. Early life microbial exposures and allergy risks: Opportunities for prevention. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemoine, A.; Tounian, P.; Adel-Patient, K.; Thomas, M. Pre-, pro-, syn-, and Postbiotics in Infant Formulas: What Are the Immune Benefits for Infants? Nutrients 2023, 15, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Luo, J.; Liu, H.; Xi, Y.; Lin, Q. Can Mixed Strains of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium Reduce Eczema in Infants under Three Years of Age? A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-Q.; Hu, H.-J.; Liu, C.-Y.; Zhang, Q.; Shakya, S.; Li, Z.-Y. Probiotics for Prevention of Atopy and Food Hypersensitivity in Early Childhood: A PRISMA-Compliant Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95, e2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indrio, F.; Gutierrez Castrellon, P.; Vandenplas, Y.; Cagri Dinleyici, E.; Francavilla, R.; Mantovani, M.P.; Grillo, A.; Beghetti, I.; Corvaglia, L.; Aceti, A. Health Effects of Infant Formula Supplemented with Probiotics or Synbiotics in Infants and Toddlers: Systematic Review with Network Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.J.; Jordan, S.; Storey, M.; Thornton, C.A.; Gravenor, M.B.; Garaiova, I.; Plummer, S.F.; Wang, D.; Morgan, G. Probiotics in the prevention of eczema: A randomised controlled trial. Arch. Dis. Child. 2014, 99, 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, S.; Watkins, A.; Storey, M.; Allen, S.J.; Brooks, C.J.; Garaiova, I.; Heaven, M.L.; Jones, R.; Plummer, S.F.; Russell, I.T.; et al. Volunteer Bias in Recruitment, Retention, and Blood Sample Donation in a Randomised Controlled Trial Involving Mothers and Their Children at Six Months and Two Years: A Longitudinal Analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.J.; Jordan, S.; Storey, M.; Thornton, C.A.; Gravenor, M.; Garaiova, I.; Plummer, S.F.; Wang, D.; Morgan, G. Dietary Supplementation with Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria Is Well Tolerated and Not Associated with Adverse Events during Late Pregnancy and Early Infancy. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madden, J.A.J.; Plummer, S.F.; Tang, J.; Garaiova, I.; Plummer, N.T.; Herbison, M.; Hunter, J.O.; Shimada, T.; Cheng, L.; Shirakawa, T. Effect of probiotics on preventing disruption of the intestinal microflora following antibiotic therapy: A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2005, 5, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherta-Murillo, A.; Danckert, N.P.; Valdivia-Garcia, M.; Chambers, E.S.; Roberts, L.; Miguens-Blanco, J.; McDonald, J.A.K.; Marchesi, J.R.; Frost, G.S. Gut microbiota fermentation profiles of pre-digested mycoprotein (Quorn) using faecal batch cultures in vitro : A preliminary study. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 74, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullish, B.H.; Pechlivanis, A.; Barker, G.F.; Thursz, M.R.; Marchesi, J.R.; McDonald, J.A.K. Functional microbiomics: Evaluation of gut microbiota-bile acid metabolism interactions in health and disease. Methods 2018, 149, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahti, L. Microbiome R package. 2019.

- Mallick, H.; Rahnavard, A.; McIver, L.J.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Y.; Nguyen, L.H.; Tickle, T.L.; Weingart, G.; Ren, B.; Schwager, E.H.; et al. Multivariable association discovery in population-scale meta-omics studies. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1009442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maechler, M.; Rousseeuw, P.; Struyf, A.; Hubert, M.; Hornik, K. Cluster: Cluster Analysis Basics and Extensions. 2023.

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D. vegan: Community Ecology Package.

- Ullmann, T.; Peschel, S.; Finger, P.; Müller, C.L.; Boulesteix, A.-L. Over-optimism in unsupervised microbiome analysis: Insights from network learning and clustering. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1010820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peschel, S.; Müller, C.L.; Von Mutius, E.; Boulesteix, A.-L.; Depner, M. NetCoMi: Network construction and comparison for microbiome data in R. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, G.; Gaynanova, I.; Müller, C.L. Microbial Networks in SPRING - Semi-parametric Rank-Based Correlation and Partial Correlation Estimation for Quantitative Microbiome Data. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, M.; Heymman, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. 2009.

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data 2010.

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Míguez, A.; Beghini, F.; Cumbo, F.; McIver, L.J.; Thompson, K.N.; Zolfo, M.; Manghi, P.; Dubois, L.; Huang, K.D.; Thomas, A.M.; et al. Extending and improving metagenomic taxonomic profiling with uncharacterized species using MetaPhlAn 4. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.-M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: An ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, D.; Chen, G.-L.; LoCascio, P.F.; Land, M.L.; Larimer, F.W.; Hauser, L.J. Prodigal: Prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Niu, B.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, S.; Li, W. CD-HIT: Accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 3150–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Huynh, W.; Chalil, R.; Smith, K.W.; Raphenya, A.R.; Wlodarski, M.A.; Edalatmand, A.; Petkau, A.; Syed, S.A.; Tsang, K.K.; et al. CARD 2023: Expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D690–D699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, J.; Gibson, M.K.; Franzosa, E.A.; Segata, N.; Dantas, G.; Huttenhower, C. High-Specificity Targeted Functional Profiling in Microbial Communities with ShortBRED. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, e1004557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pärnänen, K.; Karkman, A.; Hultman, J.; Lyra, C.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Larsson, D.G.J.; Rautava, S.; Isolauri, E.; Salminen, S.; Kumar, H.; et al. Maternal gut and breast milk microbiota affect infant gut antibiotic resistome and mobile genetic elements. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beghini, F.; McIver, L.J.; Blanco-Míguez, A.; Dubois, L.; Asnicar, F.; Maharjan, S.; Mailyan, A.; Manghi, P.; Scholz, M.; Thomas, A.M.; et al. Integrating taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling of diverse microbial communities with bioBakery 3. eLife 2021, 10, e65088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M., E.; Kristensen, K.; Benthem, K., J.; Magnusson, A.; Berg, C., W.; Nielsen, A.; Skaug, H., J.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B., M. glmmTMB Balances Speed and Flexibility Among Packages for Zero-inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Modeling. R J. 2017, 9, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R. emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means 2024.

- Anderson, M.J.; Walsh, D.C.I. PERMANOVA, ANOSIM, and the Mantel test in the face of heterogeneous dispersions: What null hypothesis are you testing? Ecol. Monogr. 2013, 83, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Arbizu, P. pairwiseAdonis: Pairwise multilevel comparison using adonis 2020.

- Bäckhed, F.; Roswall, J.; Peng, Y.; Feng, Q.; Jia, H.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Li, Y.; Xia, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhong, H.; et al. Dynamics and Stabilization of the Human Gut Microbiome during the First Year of Life. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.J.; Lynch, D.B.; Murphy, K.; Ulaszewska, M.; Jeffery, I.B.; O’Shea, C.A.; Watkins, C.; Dempsey, E.; Mattivi, F.; Tuohy, K.; et al. Evolution of gut microbiota composition from birth to 24 weeks in the INFANTMET Cohort. Microbiome 2017, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, M.F.; Andersen, L.B.B.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Mølgaard, C.; Trolle, E.; Bahl, M.I.; Licht, T.R. Infant Gut Microbiota Development Is Driven by Transition to Family Foods Independent of Maternal Obesity. mSphere 2016, 1, e00069-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoskinson, C.; Dai, D.L.Y.; Del Bel, K.L.; Becker, A.B.; Moraes, T.J.; Mandhane, P.J.; Finlay, B.B.; Simons, E.; Kozyrskyj, A.L.; Azad, M.B.; et al. Delayed gut microbiota maturation in the first year of life is a hallmark of pediatric allergic disease. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrick, B.M.; Rodriguez, L.; Lakshmikanth, T.; Pou, C.; Henckel, E.; Arzoomand, A.; Olin, A.; Wang, J.; Mikes, J.; Tan, Z.; et al. Bifidobacteria-mediated immune system imprinting early in life. Cell 2021, 184, 3884–3898.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivière, A.; Selak, M.; Lantin, D.; Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L. Bifidobacteria and Butyrate-Producing Colon Bacteria: Importance and Strategies for Their Stimulation in the Human Gut. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni Canani, R.; Paparo, L.; Nocerino, R.; Di Scala, C.; Della Gatta, G.; Maddalena, Y.; Buono, A.; Bruno, C.; Voto, L.; Ercolini, D. Gut Microbiome as Target for Innovative Strategies Against Food Allergy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Costanzo, M.; De Paulis, N.; Biasucci, G. Butyrate: A Link between Early Life Nutrition and Gut Microbiome in the Development of Food Allergy. Life 2021, 11, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Huang, W.; Yao, Y.-F. The metabolites of lactic acid bacteria: Classification, biosynthesis and modulation of gut microbiota. Microb. Cell 2023, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, L.S.; Doak, D.F. The Keystone-Species Concept in Ecology and Conservation. BioScience 1993, 43, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, S.; Curtis, N.; Zimmermann, P. The neonatal intestinal resistome and factors that influence it—A systematic review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 1539–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokela, R.; Pärnänen, K.M.; Ponsero, A.J.; Lahti, L.; Kolho, K.-L.; De Vos, W.M.; Salonen, A. A cohort study in family triads: Impact of gut microbiota composition and early life exposures on intestinal resistome during the first two years of life. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2383746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patangia, D.V.; Grimaud, G.; Wang, S.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Influence of age, socioeconomic status, and location on the infant gut resistome across populations. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2297837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaburi, G.; Duar, R.M.; Vance, D.P.; Mitchell, R.; Contreras, L.; Frese, S.A.; Smilowitz, J.T.; Underwood, M.A. Early-life gut microbiome modulation reduces the abundance of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauzin, M.; Ouldali, N.; Béchet, S.; Caeymaex, L.; Cohen, R. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations of cephalosporin use in children. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2019, 15, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milani, C.; Lugli, G.A.; Duranti, S.; Turroni, F.; Mancabelli, L.; Ferrario, C.; Mangifesta, M.; Hevia, A.; Viappiani, A.; Scholz, M.; et al. Bifidobacteria exhibit social behavior through carbohydrate resource sharing in the gut. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, M.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, W.; Chen, Y.; Cui, X. Microbiome-metabolomic analyses of the impacts of dietary stachyose on fecal microbiota and metabolites in infants intestinal microbiota-associated mice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 3336–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Bei, J.; Liang, L.; Yu, G.; Li, L.; Li, Q. Stachyose Improves Inflammation through Modulating Gut Microbiota of High-Fat Diet/Streptozotocin-Induced Type 2 Diabetes in Rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1700954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Lu, X.; Yang, X. Stachyose-enriched α-galacto-oligosaccharides regulate gut microbiota and relieve constipation in mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 11825–11831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.J.; Underhill, D.M. Peptidoglycan recognition by the innate immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaslou, Y.; Mahjoubi, E.; Ahmadi, F.; Farokhzad, M.R.; Zahmatkesh, D.; Yazdi, M.H.; Beiranvand, H. Short communication: Performance of Holstein calves fed high-solid milk with or without nucleotide. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 11490–11495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Xie, C.; Liang, X.; Li, Z.; Li, B.; Wu, X.; Yin, Y. Yeast-based nucleotide supplementation in mother sows modifies the intestinal barrier function and immune response of neonatal pigs. Anim. Nutr. Zhongguo Xu Mu Shou Yi Xue Hui 2021, 7, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Tian, P.; Zhao, J.; Wang, G.; Chen, W. Feeding the microbiota–gut–brain axis: Nucleotides and their role in early life. Food Front. 2023, 4, 1164–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, J.P.; Meydani, M.; Barnett, J.B.; Vanegas, S.M.; Barger, K.; Fu, X.; Goldin, B.; Kane, A.; Rasmussen, H.; Vangay, P.; et al. Fecal concentrations of bacterially derived vitamin K forms are associated with gut microbiota composition but not plasma or fecal cytokine concentrations in healthy adults1234. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Russel, J.; Klincke, F.; Nesme, J.; Sørensen, S.J. Insights into the ecology of the infant gut plasmidome. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Placebo N = 46 |

Probiotic N = 54 |

|---|---|---|

| Adherence to intervention in the first 6 weeks (mean ± SD) | 74.3% ± 31.2% | 66.4% ± 32.2% |

| Adherence to intervention over 6 months (mean ± SD) | 71.39% ± 30.7% | 66.25% ± 26.2% |

| Caesarean section | 41.3% | 35.2% |

| Female | 45.7% | 42.6% |

| Median birth weight in kg (IQR) | 3.44 (0.66) | 3.49 (0.77) |

| Sibling in household | 43.5% | 46.3% |

| Some breastfeeding | 82.6% | 77.8% |

| Breastfeeding (median no. weeks in 6 months (IQR)) | 7.5 (23) | 5.5 (23) |

| Townsend score (median (min - max)) | 533 (89 - 1794) | 795 (61 - 1891) |

| Townsend quintile 1 | 21.7% | 18.5% |

| Townsend quintile 2 | 23.9% | 16.7% |

| Townsend quintile 3 | 19.6% | 25.9% |

| Townsend quintile 4 | 13.0% | 24.1% |

| Townsend quintile 5 | 21.7% | 14.8% |

| Number of infants with a first degree relative that has diagnosed atopy | 84.8% | 87.0% |

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bifidobacteria Mean Relative Abundance ± SD (%) |

||||

| Placebo | 23.14 ± 23.90 | 41.46 ± 20.26 | 40.69 ± 22.29 | 46.55 ± 17.85 |

| Probiotic | 36.41 ± 24.34 | 48.99 ± 18.71 | 47.71 ± 13.90 | 47.94 ± 14.32 |

| p-value | 0.008 | 0.074 | 0.269 | 0.636 |

|

B. animalis Mean Relative Abundance ± SD (%) |

||||

| Placebo | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.59 ± 2.00 | 0.42 ± 1.14 | 0.62 ± 2.41 |

| Probiotic | 0.49 ± 1.16 | 0.85 ± 1.31 | 0.50 ± 0.97 | 0.18 ± 0.30 |

| p-value | 0.998 | 0.001 | 0.043 | 0.331 |

|

B. bifidum Mean Relative Abundance ± SD (%) |

||||

| Placebo | 0.09 ± 0.27 | 0.18 ± 0.69 | 0.44 ± 0.91 | 0.19 ± 0.43 |

| Probiotic | 0.57 ± 0.83 | 0.86 ± 0.63 | 0.70 ± 0.44 | 0.70 ± 0.64 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.013 |

|

Lacticaseibacillus Mean Relative Abundance ± SD (%) |

||||

| Placebo | 1.01 ± 3.44 | 0.84 ± 2.61 | 2.71 ± 6.27 | 2.90 ± 6.57 |

| Probiotic | 6.83 ± 11.71 | 6.25 ± 7.66 | 4.02 ± 6.27 | 3.70 ± 7.31 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.031 | 0.206 |

|

Ligilactobacillus Mean Relative Abundance ± SD (%) |

||||

| Placebo | 0.18 ± 0.74 | 0.11 ± 0.66 | 1.36 ± 6.51 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Probiotic | 6.04 ± 14.03 | 3.87 ± 5.72 | 3.36 ± 5.73 | 2.65 ± 3.86 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.000 |

| Number of samples/infants | ||||

| Placebo | 31/25 | 36/32 | 23/22 | 15/13 |

| Probiotic | 38/30 | 26/22 | 32/26 | 17/15 |

| Time Point | Centrality Measure (p-value) | Group (No. samples/ infants) |

Network Size (No. Genera) | Keystones (top 5) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank 1 | Rank 2 | Rank 3 | Rank 4 | Rank 5 | ||||

| T1 | Betweenness (0.044) | Placebo (31/25) | 40 | Faecalibacterium | Bradyrhizobium | Lachnoclostridium | Lactobacillus | Enhydrobacter |

| Probiotic (31/25) | 29 | Halomonas | Bacillus | Bilophila | Finegoldia | [Ruminococcus] gnavus group | ||

| T1 | Closeness (0.002) | Placebo (31/25) | 40 | Lachnoclostridium | Enhydrobacter | Lactobacillus | Faecalibacterium | Veillonella |

| Probiotic (31/25) | 29 | Halomonas | Bacillus | [Ruminococcus] gnavus group | Bilophila | Finegoldia | ||

| T1 | Eigenvector (0.002) | Placebo (31/25) | 40 | Lachnoclostridium | Enhydrobacter | Bacillus | Blautia | Bradyrhizobium |

| Probiotic (31/25) | 29 | Bacillus | Halomonas | [Ruminococcus] gnavus group | Bilophila | Finegoldia | ||

| T2 | Eigenvector (0.026) | Placebo (26/25) | 43 | Flavonifractor | Blautia | Raoultella | Lachnoclostridium | Peptoniphilus |

| Probiotic (26/21) | 45 | [Ruminococcus] gnavus group | [Ruminococcus] torques group | Erysipelatoclostridium | Anaerococcus | Citrobacter | ||

| T3 | Betweenness (0.033) | Placebo (23/22) | 40 | Bacteroides | UBA1819 | Intestinibacter | Parabacteroides | Alistipes |

| Probiotic (23/20) | 39 | [Ruminococcus] torques group | Bacteroides | Senegalimassilia | Staphylococcus | Collinsella | ||

| T4 | Degree (0.004) | Placebo (15/13) | 48 | Fusicatenibacter | Clostridium sensu stricto 1 | Coprobacillus | Lactococcus | Lactobacillus |

| Probiotic (15/13) | 57 | Holdemanella | Agathobacter | Dorea | Odoribacter | Phascolarctobacterium | ||

| T4 | Betweenness (<0.001) | Placebo (15/13) | 48 | Coprobacillus | Gemella | Dorea | Collinsella | Lactococcus |

| Probiotic (15/13) | 57 | Agathobacter | Staphylococcus | Holdemanella | Odoribacter | Collinsella | ||

| T4 | Closeness (0.004) | Placebo (15/13) | 48 | Coprobacillus | Lactobacillus | Lactococcus | Clostridium sensu stricto 1 | Collinsella |

| Probiotic (15/13) | 57 | Agathobacter | Holdemanella | Dorea | Odoribacter | Phascolarctobacterium | ||

| T4 | Eigenvector (<0.001) | Placebo (15/13) | 48 | Lactobacillus | Clostridium sensu stricto 1 | Coprobacillus | Lacticaseibacillus | Eggerthella |

| Probiotic (15/13) | 57 | Dorea | Odoribacter | Phascolarctobacterium | Coprococcus | Holdemanella | ||

| Placebo | Probiotic | Placebo vs Probiotic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time point (no. samples/infants) |

SP (8/8) |

EP (5/5) |

SP vs EP | SP (8/8) |

EP (13/13) |

SP vs EP | SP | EP |

| Antibiotic Class | Median abundance | p-value | Median abundance | p-value | p-value | |||

| Total | 20,801.05 | 14,610.85 | 0.065 | 17,550.55 | 13,291.35 | 0.121 | 0.798 | 0.566 |

| Multidrug | 9312.27 | 5949.31 | 0.222 | 7162.09 | 4964.88 | 0.008 | 0.959 | 0.703 |

| Macrolide | 3285.32 | 1755.77 | 0.065 | 2852.80 | 1655.09 | 0.013 | 0.505 | 1.000 |

| Beta-lactam | 1376.59 | 824.35 | 0.171 | 1022.68 | 460.44 | 0.010 | 0.645 | 0.035 |

| Cephalosporin | 827.68 | 448.33 | 0.524 | 444.36 | 201.70 | 0.121 | 0.083 | 0.007 |

| Disinfecting/antiseptic agents | 618.95 | 87.95 | 0.011 | 678.31 | 134.43 | 0.104 | 0.798 | 0.059 |

| Phosphonic acid | 268.09 | 230.47 | 0.724 | 397.25 | 142.55 | 0.037 | 0.878 | 0.566 |

| Elfamycin | 206.26 | 208.86 | 0.833 | 536.86 | 114.71 | 0.003 | 0.161 | 0.336 |

| Penam | 190.43 | 66.87 | 0.045 | 163.54 | 46.72 | 0.076 | 1.000 | 0.924 |

| Placebo | Probiotic | Placebo vs Probiotic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time point (no. samples/infants) |

SP (8/8) |

EP (5/5) |

SP vs EP | SP (8/8) |

EP (13/13) |

SP vs EP | SP | EP |

| Mobile Genetic Elements | Median abundance | p-value | Median abundance | p-value | p-value | |||

| Total | 5194.99 | 3447.77 | 0.943 | 7888.70 | 3665.54 | 0.456 | 0.645 | 0.849 |

| Integron | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.268 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.287 | - | 0.879 |

| Plasmids | 190.31 | 167.93 | 0.941 | 402.95 | 143.02 | 0.634 | 0.957 | 0.766 |

| Transposase | 2216.19 | 1925.02 | 0.622 | 2882.01 | 2001.04 | 0.972 | 0.721 | 0.633 |

| Transposon | 793.86 | 1354.81 | 0.509 | 2072.63 | 1552.11 | 0.856 | 0.873 | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).