It is reasonable and admirable that based on few evidences, the double helix was proposed in 1953[

1]. At first, it was just an interesting hypothesis [

2,

3]. The potential ability of self-replication of its chemical structure attracted the interest of many scientists. Eventually, most of the properties of this DNA model were proven afterwards. Nowadays, it is believed that under physiological conditions the double stranded DNA is mainly in the B-DNA form which is very much the same as it was proposed in 1953. The Watson-Crick Model keeps as a leading DNA structure model in molecular biology for many years. It seems few people doubting if the double helix model is true or self- evident.

The double helix model holds that under physiological conditions, two antiparallel complementary chains are bonded together by hydrogen bonds between corresponding base pairs and are always completely and tightly wound in a right-handed direction.

Yet, solid evidence has proven that the two complementary strands in the DNA are not always winding in one direction. The finding of zero linking number topoisomer provides a pivotal evidence to refute the classical double helix model.[

4,

5]

. The winding of the two paired DNA strands should be amended from plectonemic to ambidextrous which can answer many questions that the old double helix model could not.

The trouble is that there is no technique or instrument available that can clearly and directly determine the detailed secondary structure of a plasmid or chromosome; even today's most advanced electron microscopes cannot detect its detailed structure without ambiguity!

In general, X-ray crystallography can effectively determine the relative positions of atoms within a molecule and is a reliable method for determining the tertiary structure of a pure sample. Many scientists believe that the X-ray crystallographic evidence of 12bp short DNA undoubtedly proves the validity of the Watson-Crick model.[

6] However, as a microscopic study, this method has its limitations. It can only be applied to short DNA fragments, not to long DNA, such as entire plasmid molecules or chromosomal DNA.

Many people do not realize that it is questionable to extrapolate the conclusions of short fragments to long natural DNA. We know that people can only hold their breath for a few minutes at most. We can build skyscrapers, but the height will not exceed 2 kilometers. Everything has its limits. Even if the truth takes a small step forward, it will become a fallacy.

The discovery of DNA was one of the most interesting stories in the history of scientific expedition. Starting from Miescher’s finding of “nuclein”in 1869, the secret of this biological material has been repeatedly mis- understood or mislead by many great scholars of their times. After many twists, setbacks and several unexpected findings by a lot of scientists, the structure of the double helix was found by Watson and Crick. It was accepted by the science community. However, many successive new findings from various laboratories all over the world indicated that the story of DNA does not stop at 1953.

The unexpected verification of various small circular DNAs and the finding of circular chromosome of

E.coli raised a challenging question on the untangling of the double helix [

7,

8,

9]

. In order to relief the topological trouble, many new DNA models were proposed. [

10,

11,

12]

.

With the help of the magical power of topoisomerase, Crick and others wrote a review and concluded that the double helix structure was generally correct with only one exception, that is, if there was conclusive evidence to prove the existence of non-linked plasmids.[

13,

14]

.

It seems reasonable that the topological problems in DNA replication can be solved by topoisomerase. However, in 1996, Ullsperger and Cozzarelli discovered that the reaction rate of topoisomerase IV, which is responsible for unwinding the chromosomal DNA of Escherichia coli, is very slow, only 6 times per minute.[

15] The DNA replication rate in E. coli is very fast, about 1 kb per second or 3000 rpm per replicator at each replication fork, which is incompatible with the slow reaction rate of topoisomerase IV.

The secrets of DNA lie deep within nature. Unlike dark matter, UFOs, or ghosts, DNA exists objectively. Although DNA cannot think or speak for itself, scientists can still obtain some information through appropriate experiments. Unfortunately, this information is not written in any readable language.

Correctly understand or interpret it is the most difficult task for scientists. The problem is that the information obtained from nature may be interpreted differently or incorrectly, even based on the same phenomenon or facts. Therefore, it is very important to find irrefutable and conclusive evidence.

Plasmids, a special kind of extra-chromosomal DNA, are ideal proxy for the investigation of the structure and function of DNA. Due to its relative small sizes, easy to get enough quantity of pure sample, convenient to be examined by various physical-chemical methods, plasmids become the main subject of many studies. The circular structure of plasmid provides an extraordinary benefit for the survey of its secondary and tertiary structure.

In aqueous solution, the long circular strand of plasmid can pose in myriads ways. Once the hydrogen bonds between the two strands were broken, the situation would be more complicated and makes their behaviors difficult to predict. Fortunately, the two circular strands of a plasmid can quickly respond to the changing conditions and always faithfully follow the law of topology. In a closed circular DNA its linking number (Lk) is always the sum of total twist number (Tw) and writhing number (Wr), i.e., Lk = Tw +Wr.

The topology of covalently closed circular DNA tells us that there is only one special case, namely Lk = 0, in which the two circular strands of this topoisomer can be completely separated. This makes it quite distinct from its entire sister topoisomers and can be detected experimentally.

The finding of zero-linking number topoisomer strongly disproves the idea that the two chains are always coiled plectonemically. As a macroscopic study, this type of topological study can only provide limited information about the entanglement of two circular DNA strands, that is, Tw = 0, while the detailed information of each DNA section in the plasmid remains unknown.

At first, we thought the Watson-Crick Model was absolutely correct and unable to realize that the early evidence from X-ray analyzes of DNA fibers could be interpreted differently. We also fail to realize that scientific knowledge is not only universal and objective, but it can also be provisional, even the theories of Newton or Einstein can be wrong. On the other hand, the secret of DNA has so deeply hidden that its true nature can only be discovered when sufficient solid evidence is available.

After extensive reference reading and deep thinking, we found that a weakness of the B-DNA model is that it claims that the two chains are always entangled plectonemically. During our review of the literature, an electron microscope image showed that when supercoiled PM2 was denatured by formaldehyde, its two circular chains were loosely entangled. The authors of this paper only reported their observations but did not explain why they could be seen. [

16]

It's such a Eureka moment when this unusual phenomenon pops up before our eyes. We feel this is what the covalently closed circular DNA is trying to tell us. It triggered an exciting period of preparation and testing. Our most surprising finding was that in the relaxed plasmid after careful glyoxal denaturation, the two single- stranded circular DNAs of pBR322 DNA were loosely entangled with each other and were clearly visible under electron microscope.

We were too simple and naive at that time, and believed in the idiom "seeing is believing". We proposed our hypothesis: right-handed DNA and left-handed DNA can coexist in the same plasmid, and published the results [

17,

18]. This serendipitous discovery surprised many experts, because the two strands of this plasmid should be tightly entangled with each other and they are inseparable if it is in the B-DNA form.

Although our evidence was rejected by many scientists as an artifact, we still believed that our findings truly reflected the secondary structure of DNA. So we spent many years looking for more evidence to support our hypothesis.

Later, our electron microscopy results were successfully repeated and improved: a) the two circular single- stranded DNAs of purified relaxed topoisomers can be clearly seen, and the L

k of each topoisomer is fixed and can be counted; b) ) The L

k of adjacent topoisomers differ by one; c) a L

k = 0 topoisomer can be clearly located on agarose gels.[

4]

Together with many other independent evidences, it was proven that the two strands of DNA are not always winding plectonemically. As shown before, many experimental evidences to support our hypothesis: [

4,

5]

The annealing product of two single stranded circular DNAs is a relaxed plasmid.

Examined by agarose gel electrophoresis, (AGE) a singly nicked plasmid can be quickly denatured by sodium hydroxide to form two single stranded-circular DNA and two single stranded linear DNA.

The annealing product of two phagemid M13mp9 molecules, each inserted with the complementary 2Kb fragment from λDNA, is a

Figure 8 structure.

After alkaline denaturation, the electro-mobility of relaxed plasmid moves fastest, while the highly supercoiled plasmid moves slowest and moves as that of un-denatured supercoiled plasmid.[

19]

To avoid redundancy, interested readers are referred to the published articles for a more detailed explanation. [

4,

5,

19].

At present, most scientists have not realized that there is anything wrong with the double helix structure. This is probably because the primary structure of DNA has been tested countless times, and the results are always reliable and correct. The dazzling achievements of the Human Genome Project and the successful application of the primary structure of DNA in forensic science, genetic engineering and other fields have left a huge blind spot in the minds of many experts, making them unaware that there is a huge mistake hidden in the structure of double helix.

First impressions are hard to change, especially for adults, just like a person who has been bitten by a snake once will be afraid of ropes for many years. For many scientists, after years of education from textbooks or mentors, as well as brainwashing by the media, the idea of the classic double helix model has been deeply rooted. Most of them will give priority to information that conforms to their established ideas, and any information that does not conform will be automatically filtered or ignored. Perhaps this is a major source of prejudice or stereotypes!

In fact, this is another kind of Dunning-Kruger effect. Some knowledgeable professors or experts in the field are overconfident in their own experience and knowledge. They tend to ignore or dismiss all evidence or phenomena that contradict their established concepts. This Dunning-Kruger effect can occur at any time and in any field. Although scientists are more difficult to fool themselves or others, they are still human and therefore not immune to bias and error.

Contrary to what many people think, scientific knowledge is not fixed or immutable. It must be modified or revised to adapt to new findings. A good scientific theory or hypothesis should be able to reasonably explain all relevant facts and correctly predict things that have not yet happened. Scientific theories or hypotheses arise from reproducible facts or phenomena. When theory conflicts with fact, the only thing we can do is to update the theory. Objective facts or truth are immutable and unaffected by philosophy, religion, emotion and prejudice.

As our previous publications have shown, there are many examples that are not consistent to the double helix model: [

5,

19]

The two strands of λ DNA can be gradually separated by single strand DNA-binding proteins. [

21]

λ DNA can be stretched to twice its normal size. [

22]

The sedimentation coefficient indicates that T7 DNA can be abruptly changed at elevated temperatures. [

23]

Point mutations indicate that PCR reactions can be performed on plasmids. [

24]

The heat resistance of plasmid in hyperthermophilic strains. [

25,

26]

Supercoiled plasmids can transformed into relaxed form rings and some of the rings even carry a 200-300 base single-stranded loop. [

27]

The catabolite gene active protein (CAP) binds to left-handed DNA.[

28]

The slow reaction rate of topoisomerase IV cannot cope with the fast DNA replication of

E.coli DNA. [

15]

The discovery of highly positively supercoiled plasmids raises a challenging question: do they occur as z- DNA or the enantiomers of B-DNA? [

29]

Among all these facts or observed phenomena, the hidden topological problem caused by the plectonemic right- handed double helix is difficult to be noticed. The dogma of the double helix prevents the authors of these papers from thinking deeper and getting to the root of the problem. These indirect evidences provide additional reasons to refute the B-DNA model and support the ambidextrous DNA model. If the DNA duplex is in an ambidextrous DNA model, there won't be any topological problems in these experimental facts.

Scientists often get excited about discovering something new or extraordinary. It would be a pity if they cannot figure out what their discovery actually means. However, once their findings are published, their efforts are recorded and remembered. The deeper meanings hidden in these publications may capture the imagination of people with extraordinary vision and may lead to revolutions in certain fields. A striking example is the leap from Chargaff's rules to understanding the structure of DNA in base pairing. The significance of Mendel's groundbreaking discovery was rediscovered nearly forty years later, indicating that only a sensitive mind can penetrate the surface phenomenon to understand the true meaning.

Limited by personal time, knowledge and ability, it is likely that there are many similar indirect evidences buried in the literature that we have not found. In any case, all experimental results or observed phenomena published by various scientists have established a series of strong evidence, which is enough to wake up most slumbering individuals except those who are unwilling to wake up. Unlike the side-by-side (SBA) model, the ambidextrous double helix model is no longer a fantasy or pure imagination, but a reasonable scientific hypothesis.

Perhaps the finding of zero-linked topoisomer was so outlandish or heretical that no one seemed to care or notice the release of our ambidextrous DNA model. Regardless, it represents a long-standing confirmation bias in the field and urges us to seek more evidence to convince the public and experts that old ideas about DNA secondary structure must be updated.

In addition to previously published evidence refuting the Watson-Crick Model, this article is not intended to replace or substitute previous evidence, but rather to provide supporting evidence that will help readers view the secondary structure of DNA in a different way.

L. Bragg pointed out: "What is important in science is not so much the acquisition of new facts as the acquisition of new ways of thinking".

This article also provides some new ideas for studying the secondary structure of DNA.

2. The Gaussian Distribution of Supercoiled Plasmid

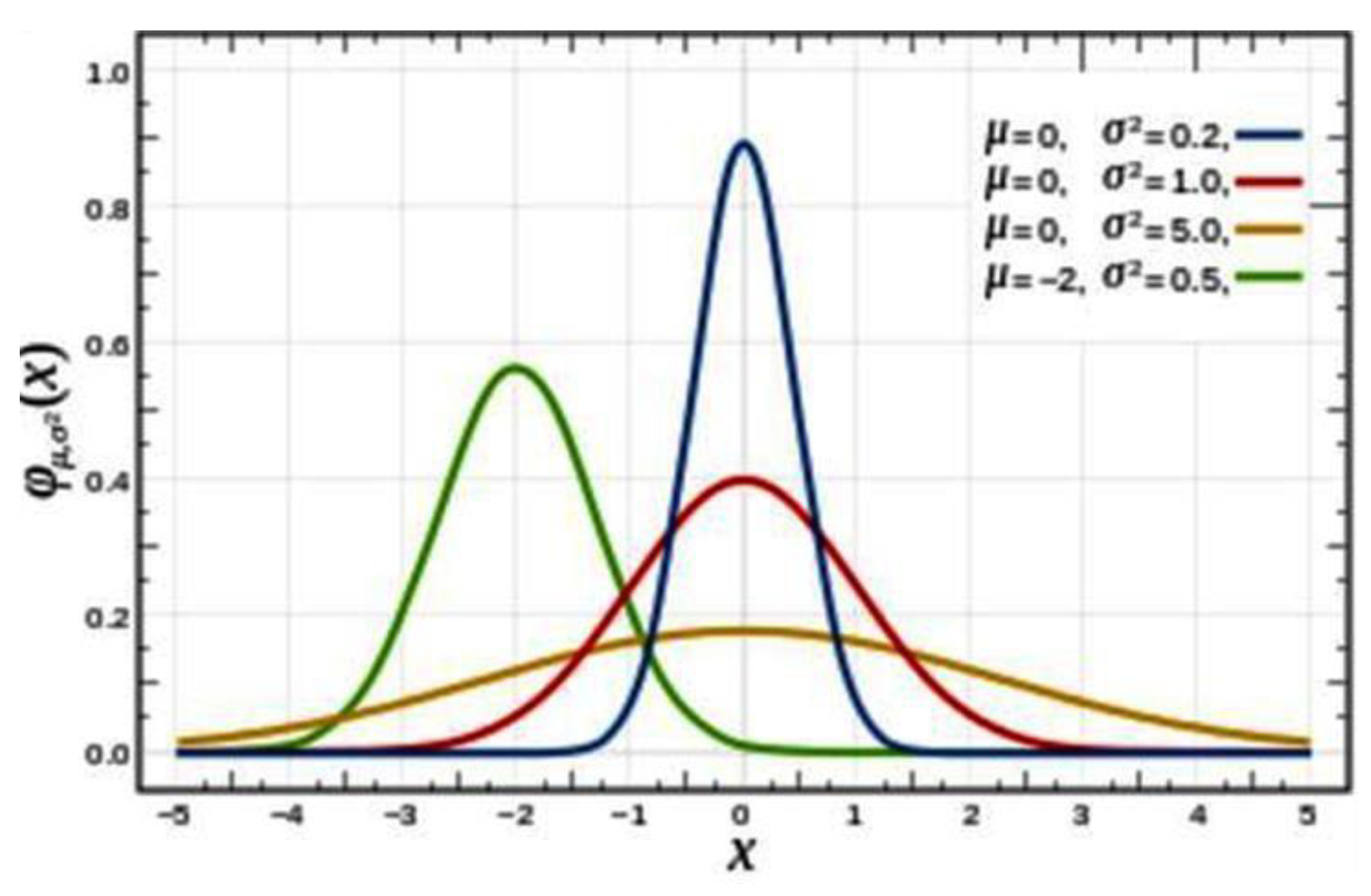

Wikipedia states: “In probability theory, a normal distribution (also known as Gaussian, Gauss, or Laplace– Gauss distribution) is a type of continuous probability distribution for a real-valued random variable.”

The general form of probability density function is

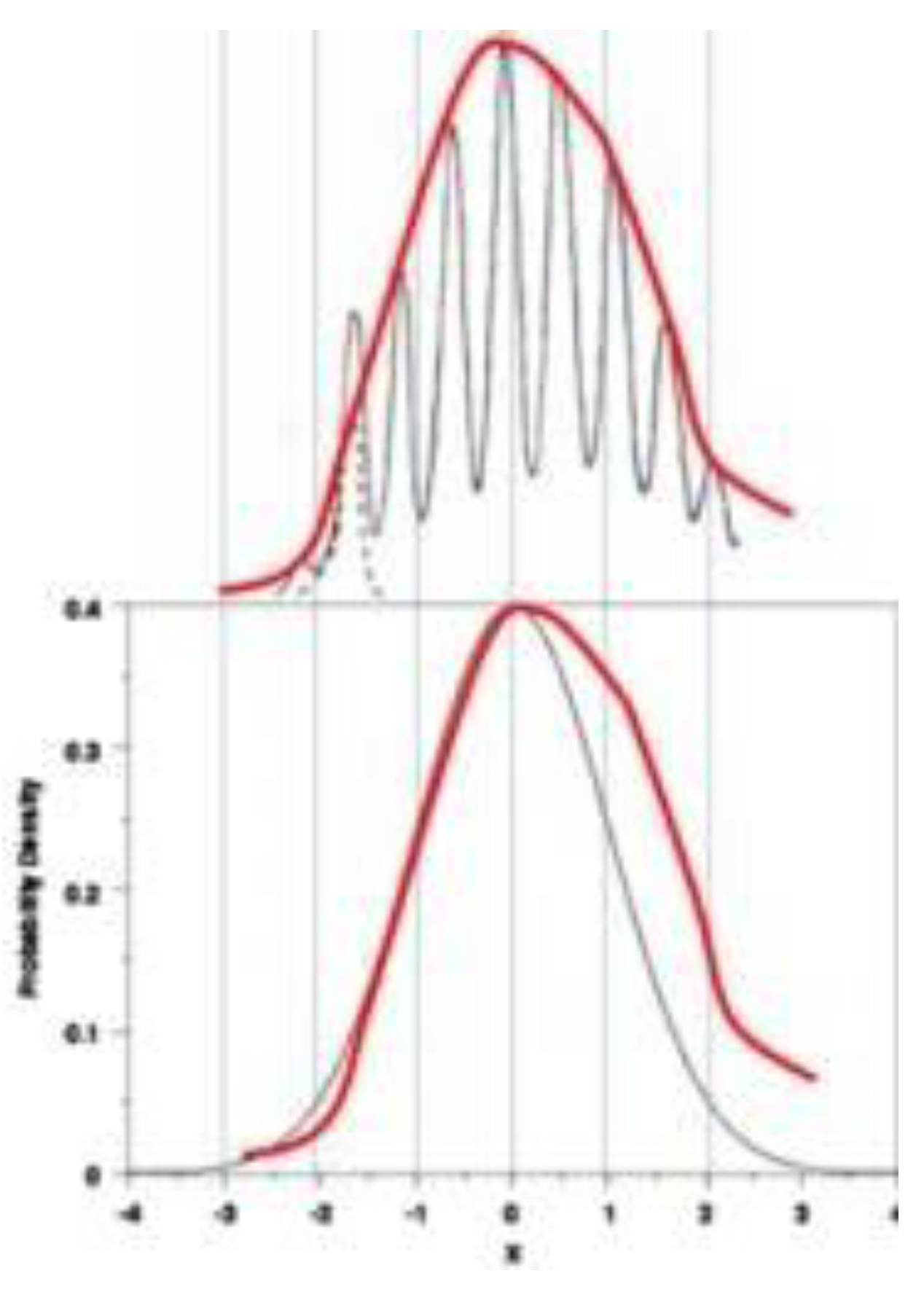

. In this Gaussian function, µ represents the mean (measured) values, and the square root of its variance or standard deviation is σ which determines the magnitude of the distribution. The total probability, or the integral of the Gaussian distribution should be: ∫f(x) = 1. When σ = 1 and x = 1, 2 or 3, the integral of the curve, or the area under the curve, is 68%, 95% and 99.7% of the total probability respectively, as shown in

Figure 1.

The topological laws apply to the study of three basic properties of closed ribbon or circular DNA duplexes, Lk = Tw + Wr. In this equation, Lk is always an integer, and the values of Tw and Wr can be variables of arbitrary data. It is reported that the topoisomer peaks observed in experiments follow a Gaussian distribution. A large number of publications have shown that the number of new relaxed topoisomers generated after a gyrase or ligase catalyzed reaction is always less than 10.[

30,

31,

32,

33]

Using the powerful resolution of AGE, Keller found that it was possible to study the supercoiled plasmid, the separated peaks are distributed following Gaussian distribution.[

30] However, why this phenomenon can be found in various plasmids is still unclear. We are trying to analyze this phenomenon and consider it as an exposure of DNA secondary structure.

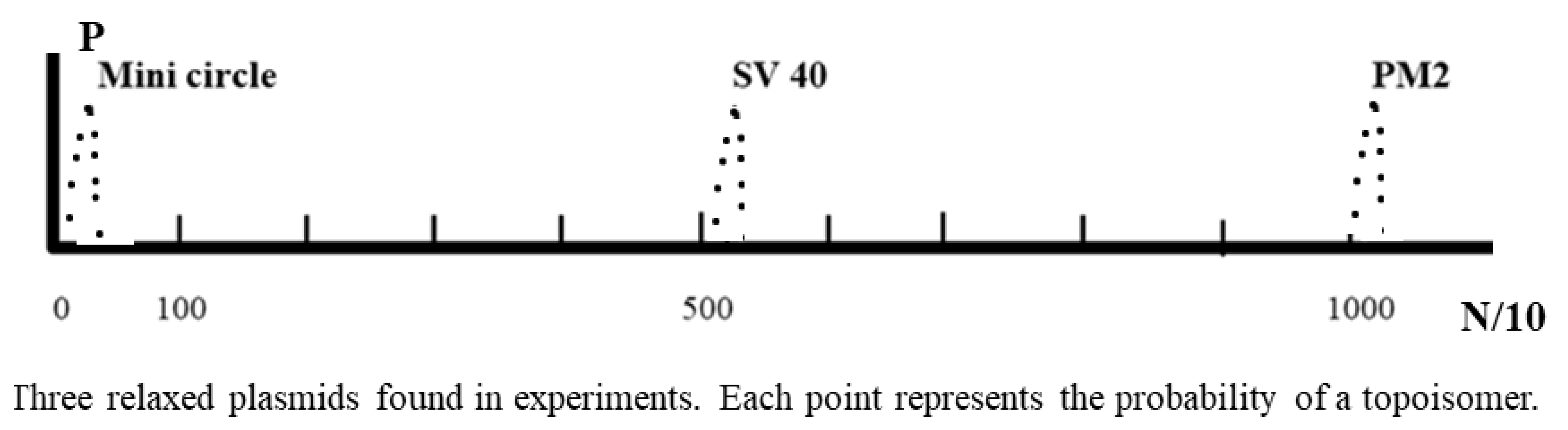

In the B-DNA model, there are 10 bases per turn. If a relaxed plasmid has N base pairs, the two strands in the B-DNA should wind T times, T

w ≈ N/10. For example, a PM2 phagemid has 10079 base pairs. In the relaxed PM2 DNA, W

r ≈ 0 ± 5, and T

w = L

k ¯ Wr = 10079/10 ± 5. ≈ 1008 ± 5. That is, in relaxed PM2, its T

w should be bounded between 1003 and 1013. It is a very narrow distribution for such a big plasmid and its Gaussian distribution should be a very sharp peak. Similar peaks could be found from smaller plasmids from SV40, 5224 bp circular DNA, or a mini circle carrying 336 bp [

34].

As shown in the following schematic drawing of

Figure 2, the three Gaussian distributions of their relaxed DNA are very similar and the integral of each curve should be the same, i.e., ∫(x) =1.

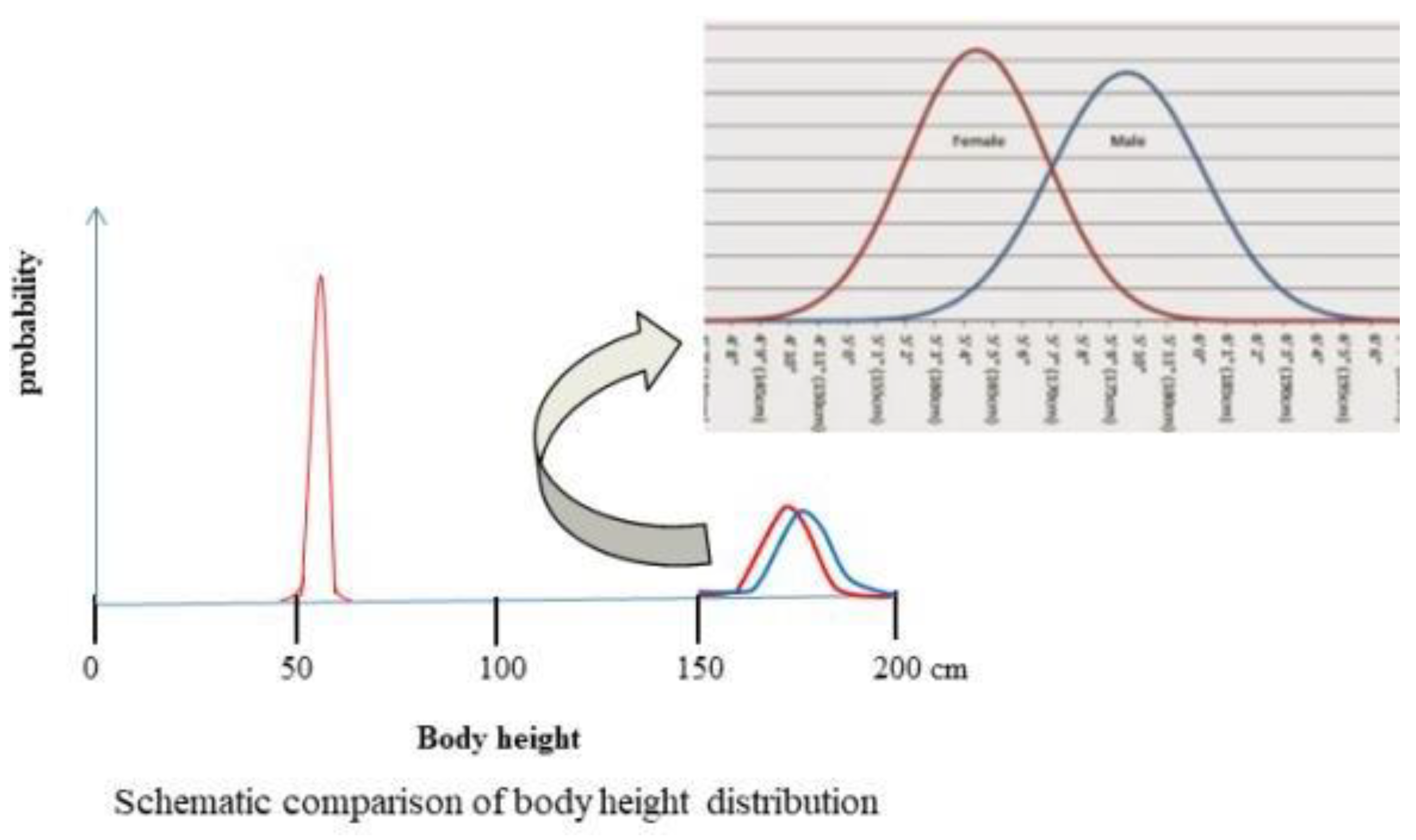

This situation is similar but different from the distribution of the heights of newborn and adult as shown in the schematic diagram of

Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows the body height distributions of man, woman and baby in America. On this figure, the average height is at the center of curve, for male is 176.94 cm and female is 163.32 cm. The distribution curve of new born baby is made based on the reported data that their height is limited in the range of 45.7 to 60cm. In this figure, the same scale is use for 3 distribution curves, the big differences in

σ makes the three curves differ greatly.

The Gaussian distribution is suitable for studying the probability of randomly happened independent incidences with no bias. A simple example is tossing a coin. The probability of a coin landing either heads or tails is supposedly 50/50. However, if the coin is specially made with different materials on each side, the tossing probability would be deviate from 50/50.

2.1. The Experimental Facts Fit to Gaussian Distribution

Interestingly, all kinds of plasmids strangely follow the Gaussian distribution. Often, this phenomenon is not recognized and cannot be explained by common sense. We believe the structure and function of DNA must obey not only the laws of physics and chemistry, but also the laws of mathematics. According to our understanding, this phenomenon reflects the classical B-DNA model violates the fundamental law of probability. However, the ambidextrous model can explain this phenomenon.

Under the ambidextrous double helix DNA model, in a zero-linking number topoisomer, its Tw should be equal to zero. Gaussian-like distributions from various plasmids can be expected if twist Tw is taken as the variable x- axis and the probability of topoisomers as the y-axis. The distribution of topoisomers following the laws of probability is a logical and reasonable solution for paired complementary strands

A typical curve obtained from experiment, as shown in

Figure 4 cited from reference 31, deviates slightly from the standard Gaussian distribution.

There are a few points worth noting:

The observed curve is asymmetric. The center of the observed curve is not always the same as the center of the standard distribution curve.

In a normal distribution, 99.7% of topoisomers should occur in the -3σ to 3σ region, this rule has to be slightly modified to accommodate experimental results.

The linking number Lk should be an integer, and the Lk of adjacent topoisomers differs by one, this ΔLk = 1 should be closely related to the difference in their winding numbers, that is, ΔTw = 1.

At first glance, the red curve looks very similar to the standard distribution with µ = 0 and σ2 = 1. The observed distribution of relaxed topoisomers slightly deviates from the normal distribution, which is not surprising, since each newly formed topoisomer is a pair of long DNA strands carrying hundreds or thousands of base pairs, which is the result of nicks or linear DNA reunions.

Catalytic reactions in aqueous solution are very complex, and their results may be affected by many factors that are not yet fully understood. The heterogeneity of the relaxed topoisomers formed after the reaction is mainly due to the dynamic movement of the double-stranded DNA, the torsional stress of the phosphodiester bonds, Brownian motion, or some other factors such as stacking interactions or hydrophobic interactions between bases. The catalytic enzyme may also affect the uneven distribution of the relaxed topoisomers.

It is likely that, in aqueous solution, in a linear or nicked DNA, its two strands are constantly twisting, moving and oscillating around the mean value µ. There should be no tension or stress on the DNA strand.

As soon as the circular DNA is sealed, a new topoisomer is produced, and its linking number is immediately fixed. At the moment of closure, the new topoisomer should have no tension or stress and its Wr should still be zero.

Then, a magical change happened!

As soon as the new topoisomer is formed, the paired strands will continue to twist keeping themselves in the most favorable position, in effect, returning to their previous position, keeping Tw at the mean µ. According to the Watson-Crick Model, its µ should be around N/10 or more accurately N/10.4, but in the ambidextrous model, this µ should be close to zero.

This topological transformation is perhaps the trickiest part of understanding the performance of circular DNA. As a result of the reaction, only several topoisomers in different superhelical states can be formed. Their properties can be detected experimentally, and their distribution represents their probability after the catalytic reactions.

It should be noted that in the ambidextrous model, the new topoisomers can be divided into three groups: the loosest with Wr = 0; the slightly negative superhelical group with Wr < 0, indicating that there are more right- handed than left-handed; Wr > 0; the slightly positive supercoiled group which means that left-handed DNA has more turns than that of the right-handed DNA. This explanation is very different from the theory written in almost all textbooks that negatively supercoiled plasmids are caused by a smaller linking number than that of their relaxed counterparts.

2.2. Applying Gaussian Distribution to the Study of Secondary Structure of DNA

According to the ambidextrous double helix model, it should be able to find a very special topoisomer hidden in the relaxed topoisomer, whose Wr = 0, Tw = 0, and Lk = 0. In the AGE test, if a relaxed topoisomer is found in agarose gel in its most relaxed state, it should be located similar to that of the nicked DNA, i.e., its Wr = 0. According to the Gaussian distribution, the mean twist value of this topoisomer should be zero, that is, Tw = 0. This speculation provides us with clear information to find a possible zero-linkage number topoisomer: Lk = Tw + Wr = 0.

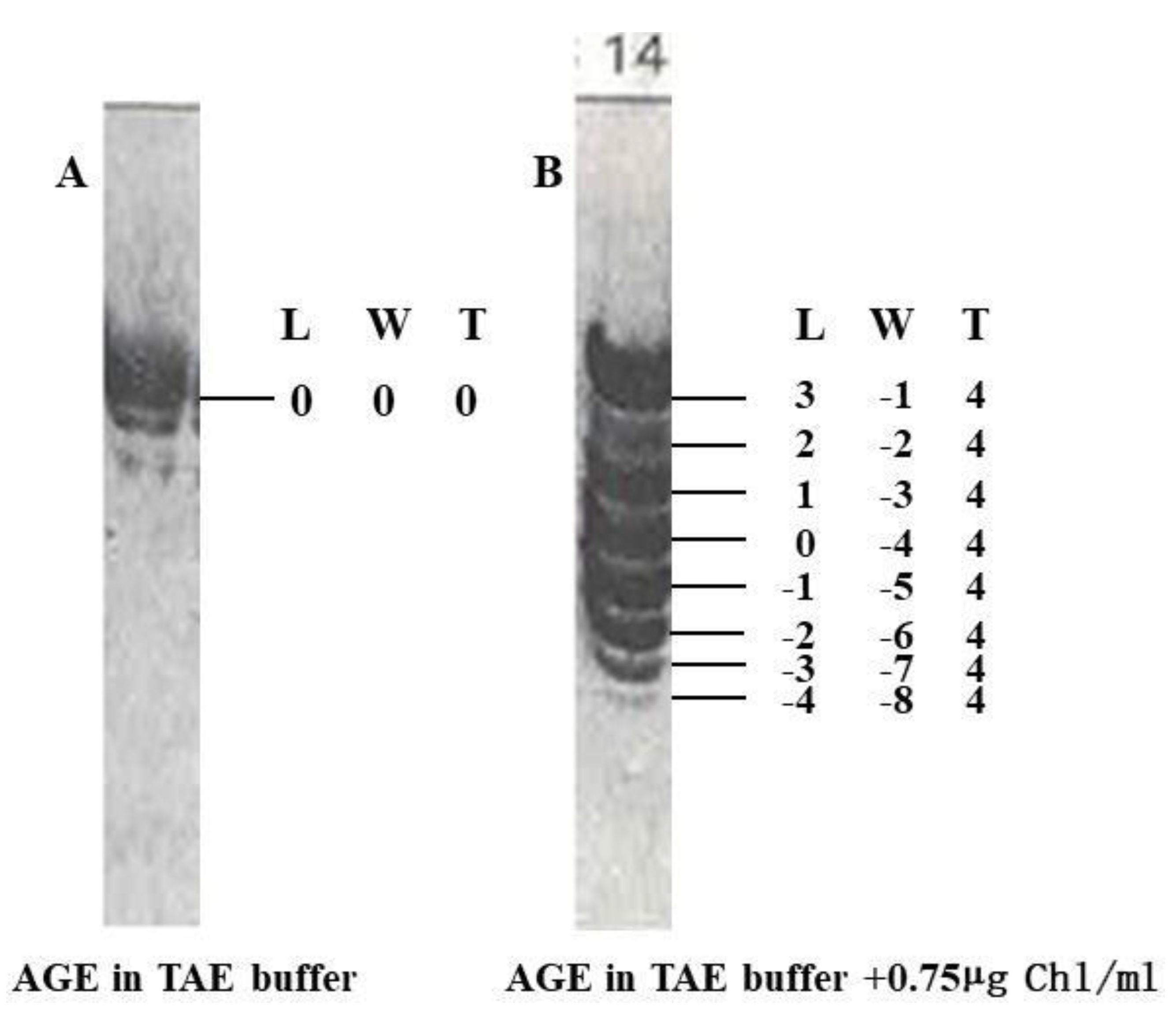

For example, although we do not know where the zero linking number topoisomer can be found in the plasmid of pBR322, but it could be found if appropriate method is available. Based on the pattern of relaxed topoisomers of pBR322 on two different agarose gels after AGE, it can be roughly located where it is, as shown in

Figure 6. [

35] However, based on B-DNA model, the linking number of relaxed pBR322 DNA should be around 436, and the total twist number should be around 436.

It is interesting to point out that the total twist number of all topoisomers in this plasmid keeps unchanged in both AGE tests. The data shown in

Figure 5 is based on ambidextrous DNA model. To make it more distinct, in AGE test A, the total twist of all topoisomers is zero, i.e., T

w = 0; in AGE test B, the total twist number of all topoisomers is 4. The insertion of chloroquine into the double helix turns the two strands unwinding 4 turns.

Figure 5.

Same amount of pBR322 DNA topoisomers relaxed by topoisomerase I at 30 ºC were separated by AGE in the (A) TBE buffer or (B) TBE buffer containing chloroquine 0.75µg /ml. [

35] All data in this figure are numbers based on the estimated plasmid topological properties using the ambidextrous model.

Figure 5.

Same amount of pBR322 DNA topoisomers relaxed by topoisomerase I at 30 ºC were separated by AGE in the (A) TBE buffer or (B) TBE buffer containing chloroquine 0.75µg /ml. [

35] All data in this figure are numbers based on the estimated plasmid topological properties using the ambidextrous model.

As pointed out in

Figure 5 A, the topological properties of each topoisomer has been clearly marked. It is noteworthy that we can get more information from the observed phenomenon published many years ago. If not supported by the law of mathematics, it is impossible to make such an audacious claim.

Surely, at this moment, it is hard to say if this claim or assertion is correct or nonsense. Hopefully the accuracy of this statement can be proven someday by experiment.

According to the classical B-DNA model, the linking number of a relaxed pBR322 should be around 436. It is impossible to seperate the two circular strands.

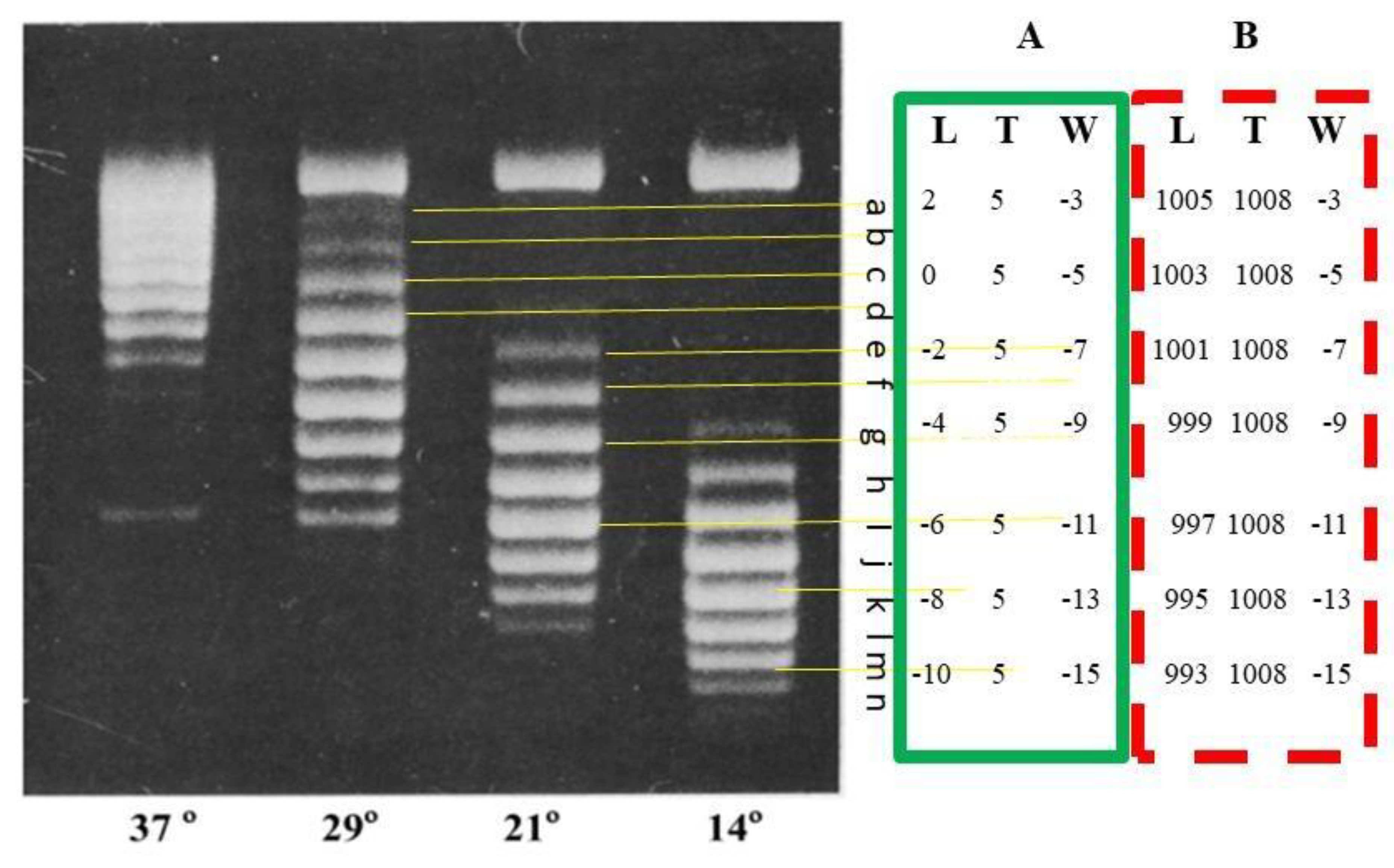

Likewise, we can get new meaning from old experimental observation as shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The topological data of each PM2 topoisomer can be clearly marked. [

31]

.

Figure 6.

The topological data of each PM2 topoisomer can be clearly marked. [

31]

.

If the PM2 topoisomers formed at 37°C were detected by AGE at 37°C, they should appear as a broad band tightly packed together like nicked DNA. However, the AGE in

Figure 6 was performed at room temperature (about 22°C). The authors Depew and Wang showed that a temperature drop of 15ºC could result in five turns of the double helix [

31]. Therefore, the DNA of these topoisomers should rotate 5 x 360° to the right.

We guess that the band c represents the L

k = 0 topoisomer. As shown in

Figure 6, for all topoisomers, their T

w =

2.3. A Reasonable Explanation for this Result Can be Derived from the Ambidextrous DNA Model

Based on the fact that after each step of enzymatic reaction, type-I topoisomerase alter one linkage (ΔL

k = 1) and type-II topoisomerase alter two linkages (Δ L

k = 2) [

36,

37], it is possible to know the exact topological property of each topoisomer.

In order to compare these data obtained from ambidextrous DNA model shown in box A with that from B-DNA, a possible set of data are shown in box B by assuming topoisomer c as the most relaxed band of Lk = 1008. Otherwise, there is no way to know which band Lk =1008 is, and there is no way to know the data of each band.

While Wr of the plasmid is determined by Lk in both DNA models, the exact meaning of Tw is quite different. One might wonder why the total twist remains constant. The answer is that the two circular chains of the plasmid should always keep their preferred structure under the same conditions.

In the ambidextrous DNA model, at 37°C, all relaxed PM2 topoisomers have Tw = 0; at 22°C: the two circular chains must rotate 5x360° to the right, resulting in their Tw = 5. In the B-DNA model, at 37ºC the relaxed PM2 topoisomers maintain Tw = 1008.

At the moment, before confirmation, nobody can be sure if these marked values are rigorous scientific data with certain precision or just our imagination since there is no standard answer can be found from anywhere.

It is worth mentioning that we must be very careful in dealing with the secondary structure of DNA. The classic double helix model should not be used as the exclusive criterion.

Real scientific knowledge comes from reproducible experimental results or signals directly from nature, not from textbooks. As previously predicted, it is always possible to find a zero linking number topoisomer in any kind of plasmid. We believe this double helix conjecture can be experimentally proven [

2,

3,

16]. Using the Gaussian distribution of plasmids, it can greatly help experimentalists to test it, because it is a prerequisite to know where to find zero linkage number.

2.4. The Old Convention Has to be Revised

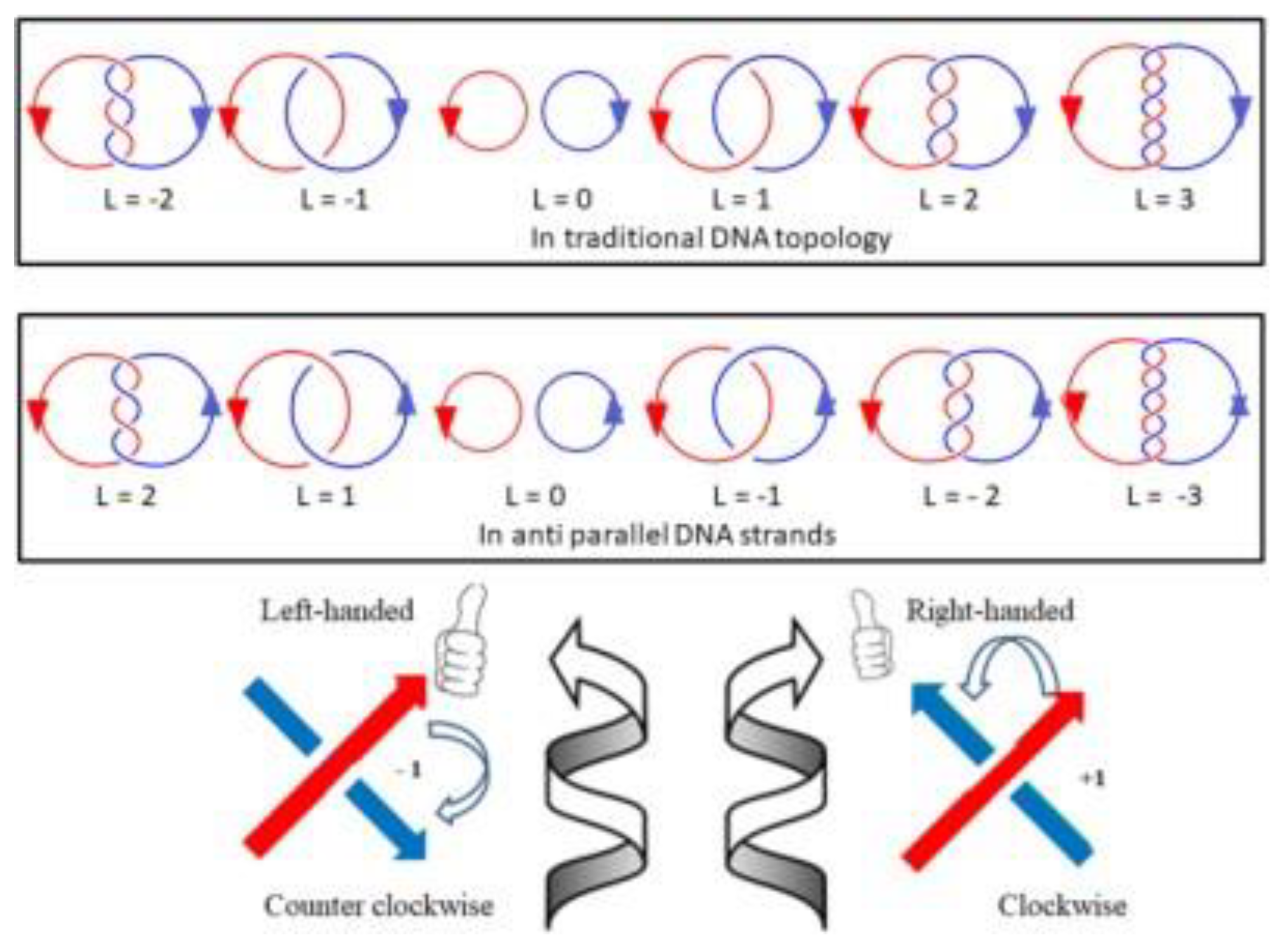

In general, the two strands of DNA are assumed to be winding plectonemically in the right-handed direction, by convention, the right-handed winding is orthodoxly taking as positive, that is, in a plasmid, the linking number is normally assumed as positive or L > 0.

With the exception of extreme thermophiles, all the native plasmids are negatively supercoiled. A simple explanation about the DNA topology can be found in the review of Schvartzman et al.[

32] or other textbooks in molecular biology.[

47]

In topology, the linking number of any closed circular double helix should be the sum of all crossing numbers

(C) divided by 2, i.e., L = Σ(C) / 2, as shown in

Figure 7. Each crossing is either positive (+1) or negative (-1) depending on the two oriented threads in three dimensional space. On the basis of DNA structure, the two complementary strands are anti-parallel and winding in right-handed direction, the sum of crossings of a negatively supercoiled plasmid should be negative, i.e., L = Σ(C) / 2< 0. Therefore, most native plasmids are negatively supercoiled DNA, their linking number should be less than zero, i.e., L < 0, contrary to traditional assumption.

As shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, the topological data of each topoisomer are clearly labeled. Clever readers may notice that the meaning of Lk in the two DNA models is inconsistent. In the ambidextrous DNA model, the Lk of the negative supercoiled plasmid is labeled as a negative number, which is opposite to the Lk of the B-DNA model.

Thus, there is a discrepancy in the meaning of linking number. The differences of two kinds of definition on the linking number can be visualized clearly in

Figure 7.

We are not sure if this disagreement or contradiction has ever been raised or recognized before. The question is: should this old rule, established decades ago and widely accepted by the scientific community, remain unchanged?

For the self-consistency of science, we think it is reasonable to follow the laws of mathematics that is more basic and can never be changed due to any new discoveries.

In fact, the old rules and regulations were proposed when someone thought they were appropriate at the time. When they become inappropriate or outdated, they should be revised. This does not denigrate the glory of science. On the contrary, it is the self-correction of science and a special ability and achievement of science.

2.5. Analysis of a Small Plasmid

As can be seen from the above discussion, different conclusions will be drawn from observing the same phenomenon from different angles. We believe that all information obtained from plasmids is important because it truly reflects the nature of DNA structure.

Applying the laws of probability to DNA topology has provided surprising insights that can explain many experimental results in different ways, including phenomena from small plasmids reported by the laboratory led by Lynn Zechiedrich. [

34]

Here, we would like to analyze their comprehensive experimental report from our perspective and show what information can be obtained from the phenomena they report.

Before proceeding with the detailed analysis, it needs to be clear that the superhelical density σ will be replaced by the superhelical index Si in this paper, as pointed out previously [

38]: In general, the supercoiled density σ, is defined as the difference in the number of linkages between supercoiled DNA (L) and relaxed DNA (L

0) divided by the number of linkages in the relaxed DNA, i.e., σ = (L – L

0)/L

0. However, if the linking number of the relaxed DNA is zero, it is unreasonable to use zero as a denominator for the supercoiled properties of a plasmid. The

supercoiled index Si is proposed as a convenient compromise to indicate the supercoiled properties of circular DNA. Si is only related to two experimentally measurable parameters: the number of twists Wr and the number of base pairs N of the plasmid, i.e. Si = Wr / (N/10.4). Si can be used as an indicator to show and compare the supercoiling of different plasmid molecules in any DNA model. The reported σ value can still be used as Si value.

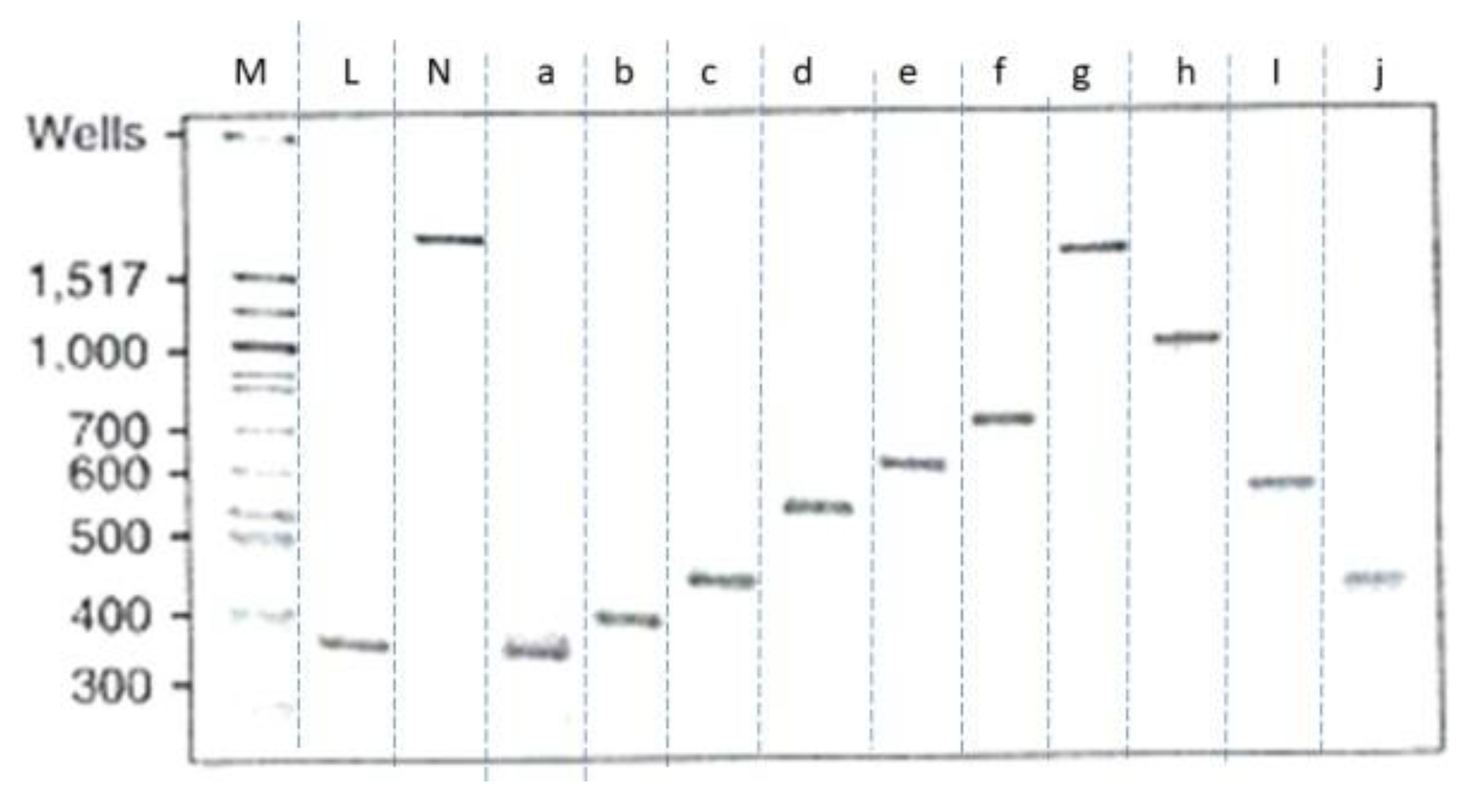

According to their report, each relaxed topoisomer from the 336 bp minicircle could be clearly separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and studied by electron cryo-tomography. [

34]

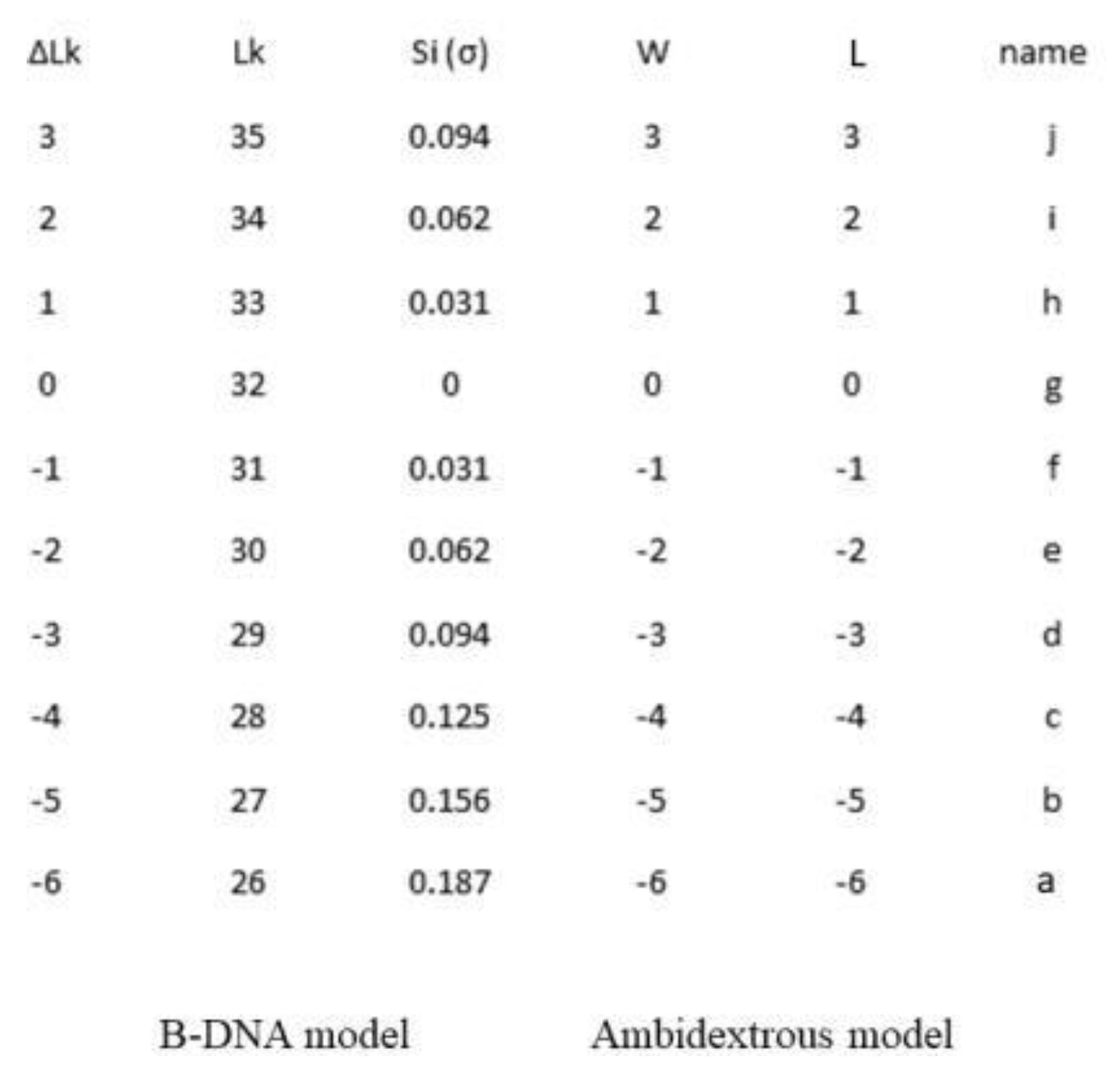

The table below lists the topological data and their different meanings based on the B-DNA model or ambidextrous DNA model.

In this gel, M represents the DNA marker, L as linear DNA; N as nicked DNA; a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, I, j, and k represents different purified topoisomers respectively.

In large plasmids, those with thousands of base pairs or more, left-handed DNA in the positively supercoiled DNA may not usually be detected by conventional AGE. However, they can have a significant impact on small plasmids, such as in this 336 minicircle. As shown in

Figure 8 and

Table 1, the properties of the positively supercoiled topoisomers are significantly different from those of the negatively supercoiled topoisomers.

Table 1.

Comparing two different DNA structure models.

Table 1.

Comparing two different DNA structure models.

Figure 8.

The relaxed 336 minicircle topoisomers appeared on polyacrylamide gel after electrophoresis[

34]

.

Figure 8.

The relaxed 336 minicircle topoisomers appeared on polyacrylamide gel after electrophoresis[

34]

.

The unusual electrophoretic mobility of topoisomers on PAGEs shown in

Figure 8 is very interesting. The law of causality tells us that every change in nature should have some reasons. We believe that the experimental results obtained from this 336 plasmid reveal many secrets of DNA structure that most people may unable to notice. With the help of ambidextrous DNA model, the strange phenomenon in

Figure 8 can be explained reasonably.

For the convenience of further discussion, the electrophoresis mobility of each sample shown in

Figure 8 and

Table 1 would be labeled as

nµx .The head note n indicates the linking number of the DNA; and the foot note x represents the name of that DNA. Since there is no linking number for linearized DNA and nicked DNA, their electrophoresis mobility can simply be marked as

µ L and

µN .

Evidently, in

Figure 8, all negatively supercoiled plasmids are line up according to their superhelicity:

Likewise, all positively supercoiled plasmids are line up in the order of their superhelicity.

The unusual electrophoretic mobility of the topoisomers on PAGEs shown in

Figure 8 is very interesting. With the help of ambidextrous DNA model, the strange phenomenon observed in

Figure 8 can be reasonably explained.

All these plasmids are appeared reasonable because, during the PAGE, their electrophoresis mobility is closely related to their resistance that is determined by their superhelicity. Only the zero linking number topoisomer is free of superhelicity and there is no tension in this kind of plasmid, hence during the PAGE, it appeared similar to nicked plasmid, i.e., µ N = 0µ g.

However, a strange phenomenon seen in

Figure 8 is that the electrophoresis mobility of all pairs of plasmids with the same absolute supercoiled index is different:

Left-handed Z-DNA is significantly different from right-handed B-DNA. There is evidence indicating that the structure of left-handed DNA in plasmids is also different from that of right-handed DNA, with a helical repeat of 12. [

26]

This may help us understand why 336 minicircle topoisomers with the same absolute supercoil index behave so differently on PAGE. Obviously, the structure of the left-hand plasmid is not the enantiomer of the corresponding right-hand plasmid with the same absolute value of W.

Clever readers may have noticed the main point in this section is that the abnormality of this phenomenon contradicts two closely related concepts in DNA topology, i.e., the two strands of DNA are always winding plectonemically in right-handed direction in that of B-DNA and the negatively supercoiling is caused due to the linking number less than that of the relaxed plasmid.

Just as the authors of the paper found large differences in the response of Bal 32 cleavage to positively or negatively supercoiled topoisomers, it reflects that the tertiary structure of positively supercoiled plasmids is quite different from that of negatively supercoiled plasmids. This phenomenon requires more detailed and careful investigation. Attributing this to the Pauling structure or P-DNA is questionable.[

39]

It is generally assumed the negatively supercoiled plasmid is caused by its linking number less than that of its relaxed counterparts, or simplified as under winding, and the linking number of positively supercoiled plasmids is more than that of relaxed counterparts, or simplified as over winding.

This kind of conception is hard to change for most experts in this field. However, the finding of highly positively supercoiled pBR322 in

E.coli raised a challenging problem. It is hard to know how the over winding structure in that kind of plasmid is. [

29]

Based on the discovery of zero-linking number topoisomer, it is clear that left-handed DNA predominates over right-handed DNA in positively supercoiled plasmids. For most experts, this concept is difficult to accept. They cannot imagine the left-handed DNA can be found in normal DNA.

Interestingly, most people thought that Z-DNA was correct because it had been proven by X-ray crystallography. However, many biologists still doubted whether this left-handed DNA existed in nature. It took Professor Rich and his team a lot of time and effort to prove that it does exist in living cells. In any case, Z- DNA with alternative purine and pyrimidine sequences occurs relatively rarely.. [

40,

41]

According to the canonical double helix model, the linking number of sample h and f should be 32 + 1 and 32 - 1, there is only one linkage differences relative to the most relaxed topoisomer. It is difficult to explain why the electrophoretic mobility of such a pair of topoisomers with the same absolute superhelical index appeared so differently. It is plausible that the topological tension just turning them in opposite directions and forming a pair of enantiomers, causing them to have the same 33µh = 31µ . Similarly, 34µi = 30µ and 35µ = 29µ , but that is not what the experiment had revealed.

The detailed mechanism of electrophoresis mobility of circular DNA has not been well studied, it is difficult to answer why the linear DNA of this 336 mini circle moves fastest in this PAGE, similar to the sample with Si = 0.187, that is much higher than the value normally found in native plasmids (Si = 0.05-0.07).[

42] Whereas, many agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE) tests on plasmid indicted the linearized plasmid DNA moves slower than their native supercoiled counterparts. Even the hyper-supercoiled plasmids are moving similarly on the agarose gel after electrophoresis.[

43] Perhaps the path of linear DNA during PAGE is a straight trajectory, like that of a flying arrow with least resistance, rather than the path during AGE, which follows the twisted track of a moving worm.

The huge morphological differences among the various topoisomers reported in the paper only tell us that 336 small circles of DNA strands can move freely in solution, and the snapshots of many topoisomers only show that their shapes may be different under normal conditions. However, we believe that each topoisomer with the same number of linkages should have a similar shape, accept the same resistance and migrate at the same rate during electrophoresis. Since electrophoretic mobility is closely related to the topology of the plasmid, slight modifications in the molecular structure even the insertion of a single base pair, can affect the electrophoretic mobility of the topoisomer. [

44]

2.6. How to Solve the Debate?

The debate on DNA secondary structure is long-standing. The parallel DNA model (SBS) was proposed in the late 1970s to prevent topological problems caused by rapid replication of Escherichia coli chromosomal DNA. However, the SBS model of a 5 bp right turn followed by a 5 bp left turn is purely a theoretical design; it does not have any experimental support. Based on experimental results, our ambidextrous DNA model is slightly different from the SBS model because its two chains can be flexibly wound together in both directions.

In the Watson-Crick Model, the twist number (T) of two circular strands in a supercoiled or relaxed plasmid is Tsupercoiled = L - W = N/10.4 - 0.05xN/10.4 = 0.95N/10.4 or Trelaxed = L ≈ N/10.4. Usually a plasmid consists hundreds or thousands of base pairs, after the denaturation the two strands are still tightly tangled with each other. Whereas, estimated from ambidextrous model, their total twist number of supercoiled or relaxed plasmid should be much smaller than 0.95 N/10.4. The two single stranded strands are loosely tangled. Hence, we predict:

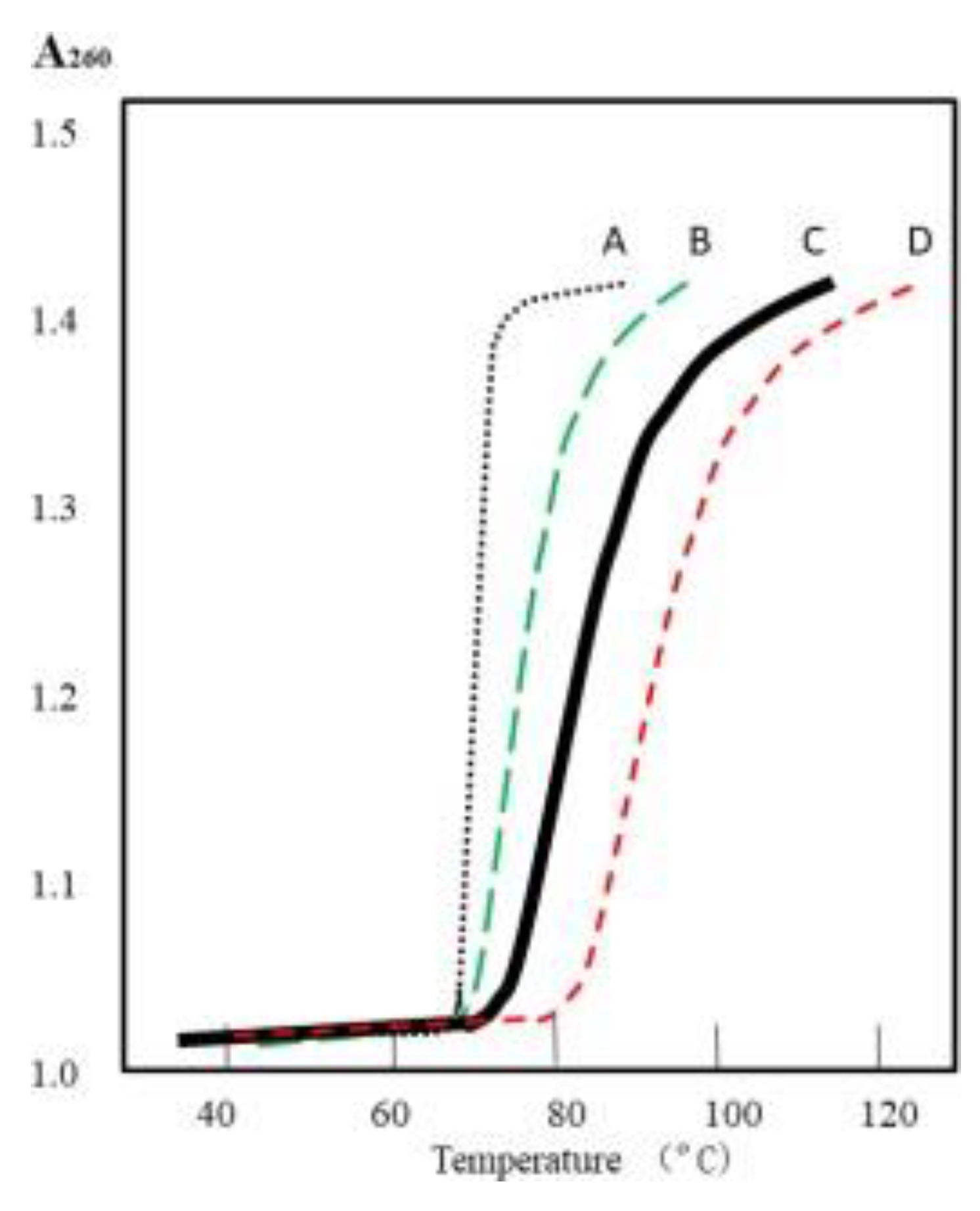

2.7. The Melting Curve of Plasmid Varies with Its Superhelicity.

It is well documented that the melting point of linear DNA duplexes in solution is related to GC content percentage, solvent, salt, and pressure. It is also worth noting that supercoiled plasmids do not melt readily at temperatures above the Tm of their linear counterparts. [

45,

46,

47]

In the light of the Watson-Crick Model, the melting curve of supercoiled plasmid should not be affected by its superhelicity, since their two circular strands are always tightly tangled with each other. However, judging by the ambidextrous DNA model, the melting curve of the relaxed plasmid should be different from that of the native supercoiled plasmid, as shown in

Figure 10 curve B.

Depending on the supercoiled index (Si) or supercoiled density (σ), the position of curve B can vary between A and C. The melting curve of zero linkage topoisomers may be similar or identical to that of their single nicked or linear counterparts, as shown in

Figure 9, curve A.

Additionally, the two tangled single strands of highly supercoiled plasmid (Si >> -0.05) should be more difficult to be separated when temperature is raised. It has been proven by alkaline denature test with agarose gel electrophoresis[

19], the melting curve of highly supercoiled plasmid should be move to higher temperatures, as expected of the curve D.

So far, no one knows what the melting curve of a relaxed plasmid looks like. Anyone interested in answering this argument can check it easily and quickly in most biochemical laboratories.

Figure 9.

Schematic melting curves of plasmid. A) linear or singly nicked plasmid; B) relaxed plasmid;. C) supercoiled plasmid; D) highly supercoiled plasmid.

Figure 9.

Schematic melting curves of plasmid. A) linear or singly nicked plasmid; B) relaxed plasmid;. C) supercoiled plasmid; D) highly supercoiled plasmid.

Our second prediction is:

To our surprise, most DNA studies are performed using the sodium salt of DNA. We found that no one had studied the acidic form of naked DNA. This sparked our imagination to wonder what would happen if the plasmid in DNA-H was in pure water or a solvent that did not contain any metal ions.

Based on a rare observation that supercoiled plasmid, pPGM 1, under the EM, most of the molecules can be seen in relaxed from, some of them even carry a 200-300 bp single stranded loop.[

27] Further investigation confirms their finding and lead us to realize the idea that in the DNA, there are two kinds of antagonistic forces, namely, the binding force of hydrogen bonds and the repelling force of negatively charged phosphate atoms. Normally, the repelling force is almost invisible when DNA is in its salt form. Our test indicates that the two strands of supercoiled pBluscript can be denatured at temperature much lower than the Tm of their linear counterparts. [

35]

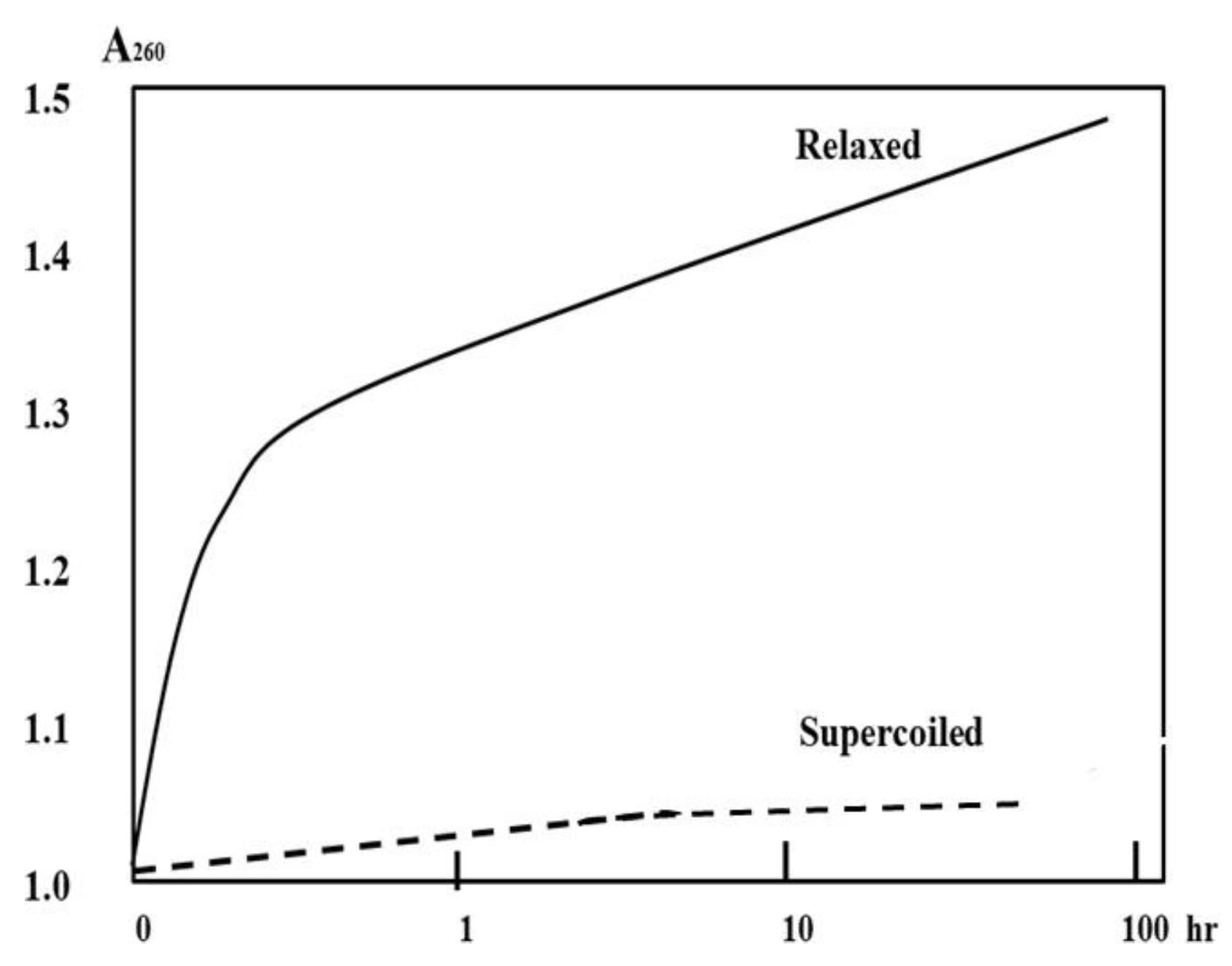

In the light of B-DNA, it is impossible to let the two tightly coiled circular DNA separated. However, we believe that the relaxed plasmid in its acid form could be completely denatured in pure water or a suitable solvent free of metal ions at room temperature. Depending on the hyperchromicity of DNA duplex, this dissociation can be tested by OD260.

Dissociation of DNA-H is likely to be a slow process at room temperature; we predict that the kinetics of relaxed plasmid dissociation can be obtained, as shown in

Figure 10. Additionally, the two strand of a supercoiled plasmid may be partially dissociated.

Figure 10.

Schematic dissociation kinetics of DNA-H of plasmid in different superhelicity.

Figure 10.

Schematic dissociation kinetics of DNA-H of plasmid in different superhelicity.

Once some kind of relaxed plasmid in the DNA-H form is obtained, this test can be performed easily in the hands of any experienced scientist. The results of this test may tell us which DNA model is closer to the truth.

Based on the Watson-Crick Model, the two complementary strands of a relaxed or supercoiled plasmid in acid form are always tightly tangled with each other and they are inseparable. Whereas, according to the ambidextrous DNA model, this prediction should be correct and can be proven by this simple test.

3. Discussion

All predictions or statements in this review are subject to verification to prove or refute the hypotheses about DNA secondary structure. Once the ambidextrous DNA model is confirmed, it will become a treasure in the repository of science and open a new chapter in the history of DNA discovery.

Knowledge is power. It helps us fight against ignorance, superstition and prejudice. Just because the sun rises in the east doesn't mean we are the center of the world. The heliocentric theory was announced to the public in 1543, but has been questioned and debated for many years. When Foucault's pendulum provided simple direct evidence of the Earth's rotation in 1851, Copernicus' theory was finally accepted. What we can learn from this history is that to convince experts or the public on some argument, a conclusive, repeatable test result must be obtained.

More than five centuries later, the Pope, who represented the Church's strongest opposition to heliocentrism, acknowledged the crimes of his predecessors against Bruno, Galileo and many others. It clearly tells us that old ideas or dogmas in people's minds are difficult to change, and we cannot expect that the ambidextrous double helix model will be easily accepted.

Scientific knowledge is non-competitive and non-exclusive, whereas different claims or hypotheses may be competitive and exclusive. During the debate, our statements were direct and pointed. Perhaps there are words that might hurt our opponent's feelings. In the interest of truth, we never say anything that is not supported by evidence, and we are willing to share our hard-won knowledge of DNA topology with the public.

However, real knowledge is hard to come by. A clear vision is needed first to identify the problem. Gathering clues or evidence to find the real reason no one knows is not an easy job. In the process of investigation, sometimes unexpected and lucky opportunities may arise, but this only makes sense to a prepared mind. For anyone exploring uncharted territory, just like the work of a criminal detective, he/she must first collect all clues, whether meaningful or meaningless, and eliminate wrong clues to ultimately hunt down the criminal suspect.

In fact, not every new idea or concept is a good one. Most of them are not good, even bad or completely wrong. How to distinguish which one is worth pursuing and which one should be abandoned is a very real problem for all organizations or individuals.

Presently, the ambidextrous double helix model is closer to the truth and can explain almost all the phenomena found by different scientists. Limited by experience, knowledge and perspective, such explanation may still be incorrect. Nobody can always make correct judgement about the observed phenomena. Scientific progress requires the cooperation of many of the best minds.

As Lao Tzu’s pointed: “To know that you do not know is the best. To think you know when you do not is a disease. Recognizing this disease as a disease is to be free of it.”

History repeatedly taught us old knowledge or traditional practices are not always correct. Facing the unknown field, our knowledge or recognition is very limited. Unfortunately, most people believe that knowledge of DNA structure is already fully understood and there is nothing new to discover.

Today, no one can cope with the numerous publications or master the different methods associated with DNA research. Since the discovery of the double helix, countless scientists have joined the research, each of them an expert in his/her field, but he/she may be a layman in all other subjects. Therefore, it is very important to carefully collect all information to determine and judge what DNA actually is.

Maybe someone will ask AI to help us to explore the secondary or tertiary structure of DNA, because no one can compete with AI in terms of memory, speed, accuracy and resilience. However, AI also has its limitations, and it always requires humans to input the correct data and formulate rules. If presented with logically incompatible dilemmas or contradictory information, it will become confused and helpless. For example, it cannot determine whether light actually a particle or a wave is. In the final analysis, no matter how powerful artificial intelligence is, it cannot completely replace human creativity!

Relying on all the available experimental findings, experience, intuition, imagination, independent deep thinking is crucial to dealing with the complex secondary structure of DNA.

We feel that the most important thing in DNA secondary structure research is not the huge financial and human investment like the Human Genome Project, the Manhattan Project, etc., but the smart people who dare to find new ways to explore DNA secondary structure, and those visionaries who can find or identify valuable new methods. In any case, in this kind of research, evidence, wisdom and courage are more important than dogma.

It is hoped that with a small investment, the outcome of this investigation may bring significant progress in the better understanding of the structure and function of this important molecule in biology.

The future is unpredictable. We don't know whether the brainpower, time, and money invested in studying the secondary or tertiary structure of DNA will yield some return or profit in the near future. This situation is similar to the DNA research in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. At that time, no one knew that the study of the primary structure of DNA could create so many new careers, lay the foundation for many multi-billion dollar companies, and have such a huge impact on modern society.

In recent years, the study of extrachromosomal circular DNA (eccDNA) in eukaryotic cell nuclei has become a new hot spot in cancer research. As a circular double-stranded DNA, eccDNA has the same topological properties as plasmids. New knowledge of DNA secondary structure and properties discovered from plasmids may provide some assistance in better understanding the various functions of eccDNA. [

48]

Now, it is time to combine the facts and evidence accumulated over the years and find reasonable reasons to correctly understand the characteristics of DNA secondary structure.

As people's understanding of DNA continues to improve, the unlimited potential of DNA secondary structure research may encourage and inspire some scientists or organizations to join this research. If this article can bring some new discoveries, it will surely be of great benefit to the progress of science.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to all scholars, family members and friends who helped, supported and encouraged him to do this independent investigation. Special thanks to professors H. Bremer, L. Terada and J. C. Wang for their professional suggestions and help.

References

- Watson, J.D.; Crick, F.H.C. Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid. Nature 1953, 171, 737. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, V. (2018) The debate over DNA replication before the Meselson-Stahl experiment (1953-1957). Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN: 1940-5030.

- Scher, S. Was Watson and Crick’s model truly self-evident? Nature 2004, 427, 584.

- Xu, Y. C. Finding of a zero linking number topoisomer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 2009, 1790, 126–133. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. C. (2019) Evidence falsifying the double helix model. Symmetry, 11,1445. (December 30, 2020 Reprinted in eBook 《Prime Archives in Symmetry》.

- E Dickerson, R.; Drew, H.R. Kinematic model for B-DNA.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1981, 78, 7318–7322. [CrossRef]

- Cairns. The bacteria chromosome and its manner of replication as seen by autoradiography. J. Mol. Biol. 1963, 208-213.

- Weil, J. H. and Vinograd, J. The cyclic Helix and Cyclic Coil Forms of Polyoma Viral DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1963, 50, 730–738.

- Dulbecco, R.; Vogt, M. EVIDENCE FOR A RING STRUCTURE OF POLYOMA VIRUS DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1963, 50, 236–243. [CrossRef]

- Cyriax, B. and Gath, R. The Conformation of Double-Stranded DNA. Naturwissenschaften 1978, 65, 106108.

- Rodley, G.A.; Scobie, R.S.; Bates, R.H.; Lewitt, R.M. A possible conformation for double-stranded polynucleotides.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1976, 73, 2959–2963. [CrossRef]

- Sasisekharan, V. Pattabiraman, N. and Goutam, G. Some implications of an alternative structure for DNA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 4092–4096.

- Crick, F.; Wang, J.C.; Bauer, W.R. Is DNA really a double helix?. J. Mol. Biol. 1979, 129, 449–461. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. C. Interaction between DNA and an Escherichia coli protein ω. J. Mol. Biol. 1971, 55, 523–526. [CrossRef]

- Ullsperger, C.; Cozzarelli, N.R. Contrasting Enzymatic Activities of Topoisomerase IV and DNA Gyrase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 31549–31555. [CrossRef]

- Brack, C.; Bickle, T.A.; Yuan, R. The relation of single-stranded regions in bacteriophage PM2 supercoiled DNA to the early melting sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 1975, 96, 693–702. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y.C. Qian, L. and Tao, Z. J.(1982) A hypothesis of DNA structure. Scientia Sinaca, 25B, 827— 836.

- Xu Y. C. and Qian, L.(1983) Determination of the linking number of pBR322 DNA. Scientia Sinica, 26B, 602—613.

- Xu, Y. C. (2011). Replication demands an amendment of the double helix. . In book: (Seligmann, H., Ed., DNA Replication-Current Advances, InTech, Rijeka, 29-56.

- Čavojová, V.; Šrol, J.; Jurkovič, M. Why should we try to think like scientists? Scientific reasoning and susceptibility to epistemically suspect beliefs and cognitive biases. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2019, 34, 85–95. [CrossRef]

- Delius, H.; Mantell, N.J.; Alberts, B. Characterization by electron microscopy of the complex formed between T4 bacteriophage gene 32-protein and DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1972, 67, 341–350. [CrossRef]

- Bensimon, D. et al. (1995). Stretching DNA with a receiding meniscus: Experiments and results. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4754-4757.

- Freifelder, D. & Davidson, P.F. (1963). Physicochemical studies on the reaction between formaldehyde and DNA. Biophysical J. 3, 49-63.

- Ochman, H.; Gerber, A.S.; Hartl, D.L. Genetic applications of an inverse polymerase chain reaction.. Genetics 1988, 120, 621–623. [CrossRef]

- Kashefi, K.; Lovley, D.R. Extending the Upper Temperature Limit for Life. Science 2003, 301, 934–934. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. C. (2014) Helical repeats of left-handed DNA. Open Journal of molecular and integrative physiology, 4, 20-26.

- I Cherny, D.; Jovin, T.M. Electron and scanning force microscopy studies of alterations in supercoiled DNA tertiary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 313, 295–307. [CrossRef]

- McKay, D.B.; Steitz, T.A. Structure of catabolite gene activator protein at 2.9 Å resolution suggests binding to left-handed B-DNA. Nature 1981, 290, 744–749. [CrossRef]

- D. Lockshon, D.R. Morris, (1983). Positively supercoiled plasmid DNA is produced by treatment of Escherichia coli with DNA gyrase inhibitors, Nucleic acids Res. 11, 2999–3017.

- Keller, W. Determination of the number of superhelical turns in simian virus 40 DNA by gel electrophoresis.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1975, 72, 4876–4880. [CrossRef]

- E Depew, D.; Wang, J.C. Conformational fluctuations of DNA helix.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1975, 72, 4275–4279. [CrossRef]

- Schvartzman, J.B.; Hernández, P.; Krimer, D.B.; Dorier, J.; Stasiak, A. Closing the DNA replication cycle: from simple circular molecules to supercoiled and knotted DNA catenanes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 7182–7198. [CrossRef]

- E Pulleyblank, D.; Shure, M.; Tang, D.; Vinograd, J.; Vosberg, H.P. Action of nicking-closing enzyme on supercoiled and nonsupercoiled closed circular DNA: formation of a Boltzmann distribution of topological isomers.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1975, 72, 4280–4284. [CrossRef]

- Irobalieva, et al. (2015). Structural diversity of supercoiled DNA. Nature communication, volume 6, Article number: 8440. DOI: 10.103.

- Xu, Y. C. and Bremer, H. (1997). Winding of the DNA helix by divalent metal ions. Nucleic Acids Research, 25, 4067-4071.

- Brown, P.O.; Cozzarelli, N.R. A Sign Inversion Mechanism for Enzymatic Supercoiling of DNA. Science 1979, 206, 1081–1083. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. C. (2009) Untangling the double helix. Cold spring harbor laboratory Press.

- Xu, Y. C. and Liu, X. Y. (2018). Recent progress s in double helix conjecture. Int. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 7: 85–100. (The original manuscript with no misprinting can be found from the attachment of eBook《Prime Archives in Symmetry》at: https://videleaf.com/evidence-falsifying-the-double-helix-model/).

- Allemand, J.F.; Bensimon, D.; Lavery, R.; Croquette, V. Stretched and overwound DNA forms a Pauling-like structure with exposed bases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998, 95, 14152–14157. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.H.-J.; Quigley, G.J.; Kolpak, F.J.; Crawford, J.L.; van Boom, J.H.; van der Marel, G.; Rich, A. Molecular structure of a left-handed double helical DNA fragment at atomic resolution. Nature 1979, 282, 680–686. [CrossRef]

- Rich, (2004) The excitement of discovery. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 73, 1-37. 2004.

- Higgins, N.P.; Vologodskii, A.V. Topological Behavior of Plasmid DNA. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3. [CrossRef]

- Pruss, G.J.; Drlica, K. Topoisomerase I mutants: the gene on pBR322 that encodes resistance to tetracycline affects plasmid DNA supercoiling.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1986, 83, 8952–8956. [CrossRef]

- Vetcher, A.A.; McEwen, A.E.; Abujarour, R.; Hanke, A.; Levene, S.D. Gel mobilities of linking-number topoisomers and their dependence on DNA helical repeat and elasticity. Biophys. Chem. 2010, 148, 104–111. [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Lahiri, A. Effect of supercoiling on the melting characteristics of heteropolynucleotides. Biophys. Chem. 1991, 40, 33–41. [CrossRef]

- V. Gagua, B. N. Belintsev and Y. L. Lyuchenko( 1981)Effect of base-pair stability on the melting of superhelical DNA. Nature, 294, 662-663.

- D. Freifelder, 1982, Physical biochemistry, W/ H Freeman & Co.

- Yang L. et al., (2022) Extrachromosomal circular DNA: biogenesis, structure, function and diseases. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 7, 342.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).