1. Introduction

Elephants (Elephas maximus indicus) have been an integral part of Thai culture, history, and national identity for centuries, serving as a revered symbol of the nation (Han, 2020). In Thailand, elephants are classified into two distinct populations: captive elephants, which have worked alongside humans for centuries and are now primarily used in the tourism industry (Bansiddhi et al., 2020), and wild elephants, which are classified as an endangered species (IUCN, 2021). The latter population is involved in human-elephant conflict (HEC), leading to significant collateral damage, including human and elephant fatalities, injuries, and property destruction (Withanage et al., 2023).

HEC has been a persistent issue in regions where human activities overlap with elephant habitats. This conflict has been reported in 31 countries, with the majority of reports originating from Asia (Saha and Soren, 2024). Thailand is among the leading countries affected by HEC, which has significant impacts on conservation efforts, society, and the national economy (Wettasin et al., 2023; Jarungrattanapong and Olewiler, 2024; Saha and Soren, 2024). HEC is suspected to be driven by agricultural expansion and infrastructure development encroaching upon the natural habitats of wild elephants, largely due to increasing human populations (Graham et al., 2009; Kumari et al., 2024).

Although elephant is considered the national symbol of the country, the study of HEC in Thailand is still limited. One national report showed 107 occurrences of HEC across Thailand during between 2012 and 2018, resulting in 75 human deaths or injuries and 32 elephants were killed or injured, and the trend of injuries for both humans and elephants tend to continuously increase in Thailand (Noonto et al., 2018).

HEC is considered to be a multifactorial issue, influenced by environmental, elephant-related, and human-related factors. Environmental factors associated with HEC include habitat loss, the replacement of natural vegetation with economic crops, and climate or seasonal changes. The conversion of forests into agricultural lands and infrastructure development has significantly reduced elephant habitats, forcing elephants to encroach on human-dominated areas (Sukumar, 2006; Köpke et al., 2024; Perera, 2009). Certain economic crops, such as durian, cassava, and sugarcane, are particularly attractive to elephants, drawing them into agricultural areas (Wettasin et al., 2023). Additionally, climate change affects water availability and food sources, exacerbating the conflict by altering elephant migration patterns and increasing their reliance on agricultural areas (Guarnieri et al., 2024; Ounlert and Sdoodee, 2015; Jarungrattanapong and Olewiler, 2024).

Elephant associated factors may include population growth, foraging behavior, adaptation and learning ability. A high number of wild elephants can lead to human-elephant conflict (HEC) when elephants and humans compete for food, water, and land. The growth of elephant populations is also affected by many demographic factors, such as births, deaths, immigration, and emigration. These are affected by environmental factors like the quality of the habitat and the amount of water available, as well as human disturbances like poaching and land conversion (Nampindo and Randhir, 2024). Elephants might change their foraging behavior seasonally to meet their nutritional needs. During wet seasons, they prefer grasses, which are more abundant and nutritious, while in dry seasons, they shift to browsing woody plants due to the scarcity of grasses (du Plessis et al., 2021). Moreover, elephants exhibit advanced cognitive abilities, including memory and social learning (Nampindo and Randhir, 2024), they learn to navigate human-dominated landscapes, adapt their behavior to access crops or avoid barriers like fences (Huang et al., 2024).

Human associated factors include human population growth, economic status, and societal attitudes. Increasing human populations intensify competition for space and resources, leading to habitat encroachment and fragmentation, which exacerbate conflicts (Shaffer et al., 2019). Lower-income individuals often exhibit lower tolerance toward elephants due to the substantial economic losses associated with crop damage and property destruction (Van de Water and Matteson, 2018). Notably, past experiences with crop damage or safety threats influence community attitudes, often reducing tolerance toward elephants (Kitratporn and Takeuchi, 2020; Gunawansa et al., 2023). In contrast, communities that benefit financially from elephants, such as those engaged in ecotourism, are more likely to support conservation efforts and coexistence (Van de Water and Matteson, 2018).

Although many strategies have been used to resolve HEC (Sukmasuang et al., 2024), the occurrence of HEC is still generally increasing, this could reflect the fact that the underlying of this problem may not be found or the resolution is not entirely corrected, since the research of HEC in Thailand is still limited (Sukmasuang et al., 2024). Therefore, the importance of this research lies in its potential to deepen our understanding of the factors driving national HEC and to inform the development of sustainable management practices. The objective of this study was to investigate the dynamic occurrences and identify the contributing factors of HEC in Thailand based on a decade of data (2014-2023). Ultimately, addressing HEC is essential not only for the protection of elephants but also for promoting sustainable coexistence between human populations and wild elephants in Thailand.

2. Materials and Methods

Ethics

This study did not require ethical approval for human or animal research, as all information was obtained from publicly available online sources provided by private and government agencies.

Data collection

HEC occurrences were collected from online news reported from January 2014 to December 2023. Data collection was conducted using google search engine in Thai languages with keywords such as “human, death, injury, elephant, and/or conflict” focusing on incidents that occurred between January 2014 to December 2023”.

HEC raw data was recorded in Microsoft® Excel® 2016 MSO (Version 2501, Build 16.0.18429.20132, 64-bit). The dataset included details such as date, duration, season, location, news reference, number of people involved, number of wild elephants involved, and contributing causes and factors. All data were thoroughly reviewed to eliminate duplication.

Data visualization

The occurrences of HEC were categorized into 6 regions, eastern, northern, northeastern, southern, central and western. The national map of HEC occurrence was created using ArcGIS Pro (ESRI, Redlands, California, USA). The occurrences were also categorized into three periods throughout the year: March to June (considered the summer season in Thailand), July to October (the rainy season), and November to February (the winter season). The occurrences were presented as raw number of HEC and mean ± standard error mean (SEM) for each area or season. For collateral damage of HEC, it was defined into 3 groups: elephant casualty (injury and death), human casualty, and property damage (agricultural area, vehicles, and buildings). Forest area data was presented in terms of Rai and the percentage of forest area relative to the total land area.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using R program (version 3.4.0) (R: The R Project for Statistical Computing, 2023). Geographic and seasonal effects on HEC were analyzed using generalized estimating equations (GEE), while multiple comparisons among areas and seasons were conducted using Tukey’s post-hoc tests. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Occurrences of HEC

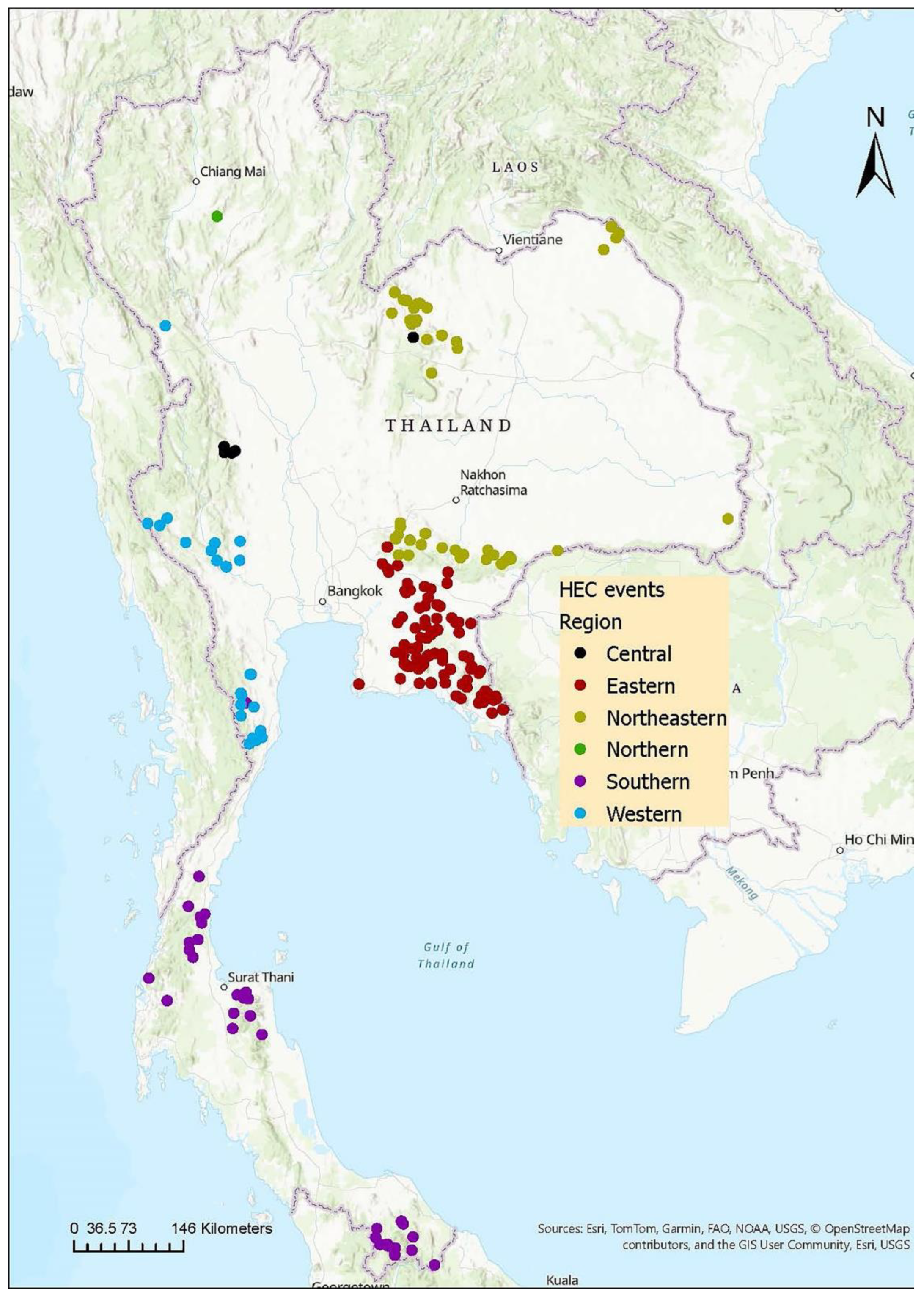

HEC was reported by 30 news agencies, documenting 341 occurrences of human-wild elephant conflicts across 34 out of 77 provinces in Thailand (44.15% of the country). Each occurrence is detailed in

Figure 1.

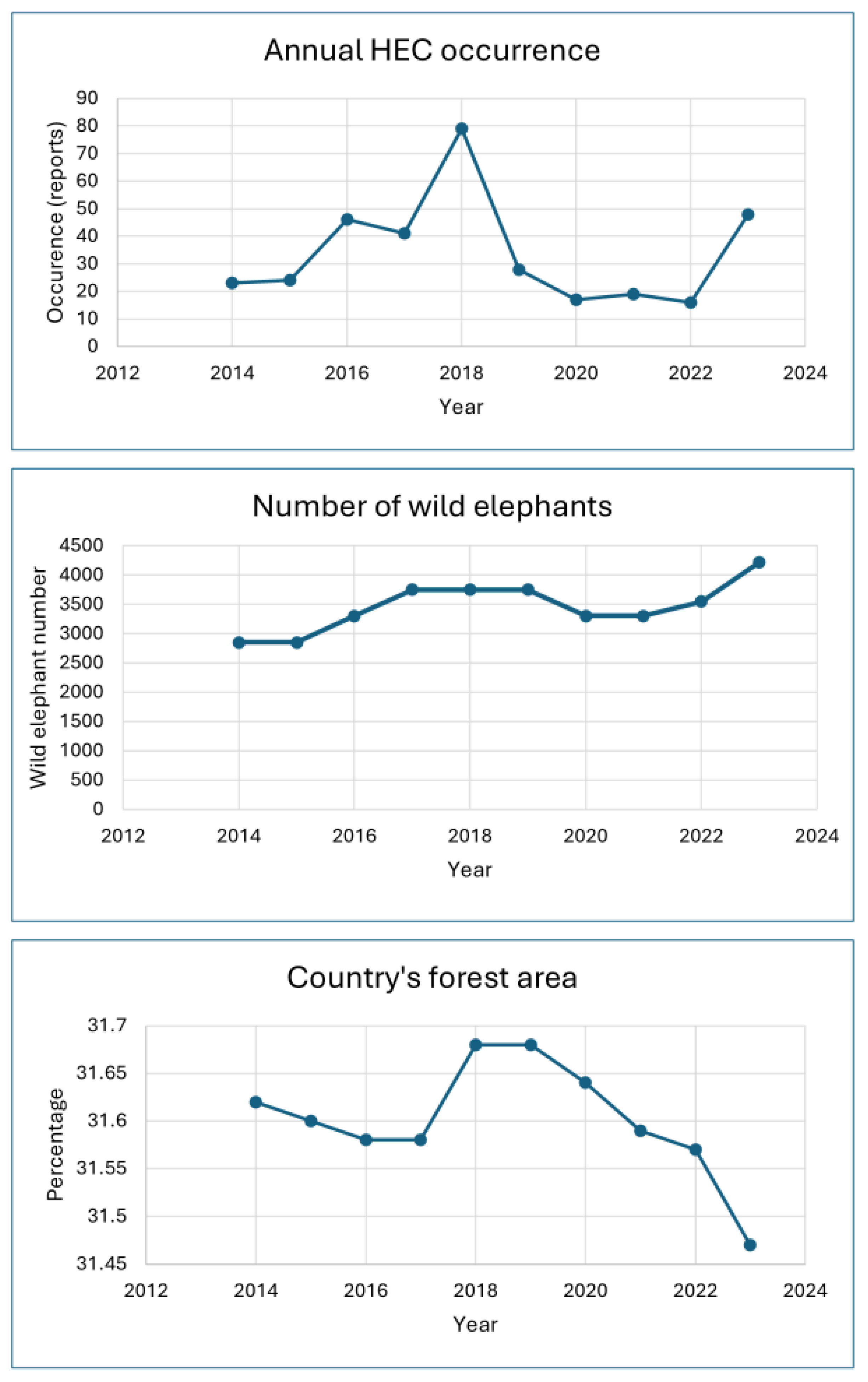

The occurrence of HEC in Thailand exhibited a fluctuating trend over the past decade, as shown in

Figure 2 and

Table 1. The number of reports increased from 2014 (n = 23) to a peak in 2018 (n = 79), followed by a sharp decline in 2020 (n = 17). The occurrence remained relatively stable until 2022 before rising dramatically in 2023 (n = 48), particularly in the northeastern region. HEC occurrences were reported in all regions of Thailand (

Figure 1 and

Table 1). The highest number of occurrences was recorded in the eastern region (n = 147), while the northern region had the lowest number of incidents (n = 1).

HEC was also found in all periods of the year as shown in

Table 2. The highest number of occurrences were recorded between July to October (n = 162), while the period of March to June had the lowest number of incidents (n = 47).

3.2. Collateral Damage of HEC

Over the past decade, HEC incidents involved 9,812 wild elephants and 360 humans. These conflicts have resulted in various forms of damage, including human casualties, elephant casualties, and property damage. The details of collateral damage of HEC regarding to casualty are shown in

Table 3.

A total of 234 elephant casualties were recorded, comprising 166 deaths and 68 injuries (

Table 3). Elephant casualties increased continuously from 2014 (n = 3) to the highest occurrence in 2022 (n = 51). Most elephant casualties resulted from electrocution (42.31%, n = 99/234), followed by road accidents (29.91%; n = 70), gunshots (23.50%; n = 55), and poisoning (4.27%; n = 10). Notably, incidents of electrocution, gunshots, and poisoning of elephants have all occurred on agricultural land.

Human casualties involved 360 individuals, comprising 189 deaths and 171 injuries. Human casualties slightly increased from 23 cases in 2014 to 51 cases in 2023 (

Table 3). Humans were most frequently attacked on agricultural farms (55.56%; n = 200/360), followed by incidents occurring in forests (27.78%; n = 100), villages (11.11%; n = 40), and roads (5.56%; n = 20).

Property damage, including broken cars and motorcycles resulting from road accidents, was reported in 4.10% of all HEC occurrences (n = 14/341). Severe agricultural damage was reported in 72 instances (20.11%), despite elephants entering the agricultural farm on 253 occasions (74.19%). Wild elephants intruded into agricultural farms in search of water and food, causing substantial damage to various crops, including rice, unmilled rice, bananas, cassava, palm, durian, coconut, jackfruit, mango, rambutan, longkong, sugarcane, date palm, cashew nuts, corn, longan, pineapple, rubber trees, watermelon, cucumbers, and yardlong beans. Moreover, some wild elephants (31%, n = 106/341) destroyed buildings to find food; they targeted food sources such as areca nuts, turmeric, and mangosteen, as well as non-plant-based items like fermented fish, shrimp paste, and fish sauce.

In 2023, the occurrence of HEC in the eastern and northeastern regions increased again (

Table 1). The majority of occurrences were associated with elephants entering agricultural land in the northeastern region (27.08%, n = 13), compared to the eastern region (8.33%, n = 4).

3.3. Effect of Geography and Periods on HEC

There were significant geographical effects on national HEC occurrences in Thailand from 2014 to 2023 (P < 0.05). The eastern region had the highest annual average occurrence of HEC (14.22 ± 1.96 per year, P < 0.05), whereas the northern part had the lowest average occurrence (0.10 ± 0.10 per year) (

Table 1).

National HEC occurrences were also statistically associated with periodical variations. On average, the highest number of HEC occurrences appeared between July and October (rainy season) (16.20 ± 2.25 per year, P < 0.05), while the lowest occurrences were reported between March and June (summer) (4.70 ± 1.53 per year, P < 0.05) (

Table 3).

When considering only the eastern region, the highest total and average occurrences of HEC were observed from November to February. HEC occurrences during this period were significantly higher than those from March to June (P < 0.05) but not compared to July to October (P > 0.05). The HEC occurrences for each period in the eastern region are presented in

Table 4.

3.4. Comparing the Pattern of Forest Area, Number of Wild Elephants, and HEC

Over the past decade, Thailand’s forest areas exhibited fluctuations, increasing from 2017 to 2018, stabilizing for one year, and continuously decreasing till 2023. (

Figure 2). The pattern of the forest area did not match the trend of national HEC, since the forest area was continuously declining, the same as the HEC occurrence. However, the pattern of national HEC corresponded with the estimated wild elephant population. When national HEC peaked in 2018, the wild elephant population also reached its highest level in the previous four years (2014–2018) (

Figure 2). The population then declined around 2020 before increasing again in subsequent years.

Regarding the eastern area, where the highest total HEC occurrence was reported, this region has the lowest forest area (around 4.71 million Rai) compared to other regions, with the proportion of forest per total area being approximately 21% (Supplementary data,

Table S1). In contrast, the northern region has the highest forest area (38.43 million Rai), with 64% of the total area covered by forests (

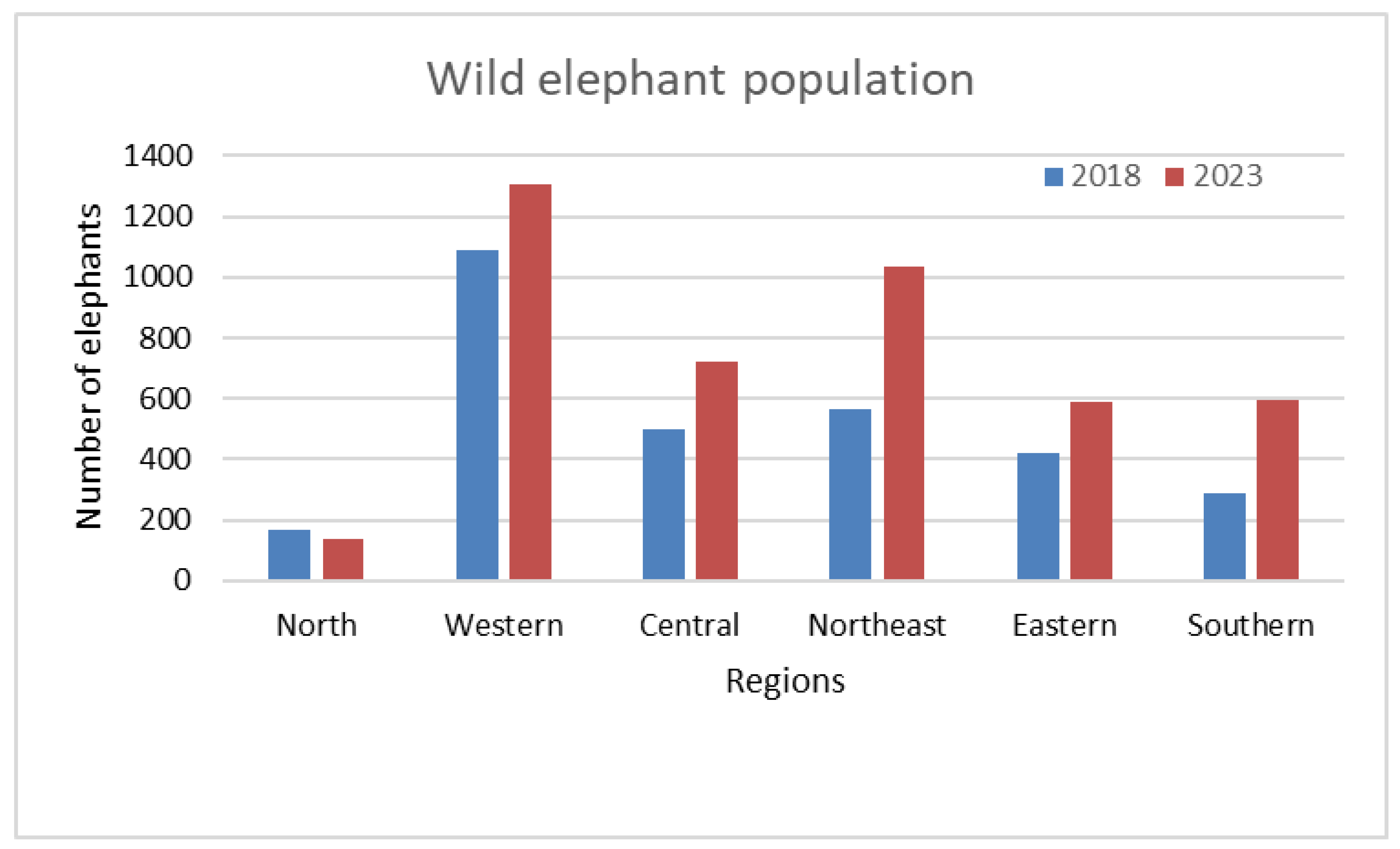

Table S1). The highest forest area in the northern region appears to coincide with the lowest total occurrence of HEC in that area. Additionally, the wild elephant population in the eastern region was found to be lower than that in the western, central, and northeastern regions (

Figure 3).

Over the past decade, the wild elephant population has shown an increasing trend (

Figure 3), particularly in the northeastern and southern regions, where the population nearly doubled between 2018 and 2023 (

Figure 3). The highest wild elephant population was observed in the western region, while the lowest was recorded in the northern region. Additionally, the substantial rise in the wild elephant population in the northeastern region in 2023 corresponded with the highest occurrence of HEC in the same area and year (

Table 1).

4. Discussion

This study described HEC in Thailand for a decade (between 2014 to 2023). The occurrences were found in 45% of all provinces in Thailand. HEC resulted in several collateral damages, including human and elephant casualties, as well as property destruction. Notably, national HEC was found to be significantly associated with specific areas and periods. The pattern of national HEC also appeared to be related to the wild elephant population but not to forest area. However, when focusing on the regional HEC pattern, it was found to be complex, influenced by factors such as period, crop production, forest area, and the number of wild elephants.

The occurrence of HEC was statistically associated with regions, and the highest occurrence reported in the eastern region. As most HEC incidents occurred on agricultural farms, leading to crop damage, it indicates that elephants primarily entered human settlements in search of food. This theory is supported by findings from another study, which identified 29 types of crops consumed by elephants (Wettasin et al., 2023). The present study suggested that the high occurrence of HEC in the eastern area might be strongly associated with its status as a major crop-producing area, including provinces such as Rayong, Chonburi, Chachoengsao, and Chanthaburi. These provinces are key producers of many crops including rice, casava, para rubber, sugarcane, corn, pineapples, longans durian, mangosteens, rambutans, mangoes and longkong, with peak production occurring from May to February, potentially attracting elephants in search of food (Ounlert and Sdoodee, 2015; Thongkaew et al., 2021). A similar pattern is also observed in Cambodia, where the highest HEC incidents occur during the crop growing season, when elephants are drawn to agricultural areas in search of food (Webber et al., 2011).

Conversely, the northern region had the lowest HEC occurrence, possibly due to its lower wild elephant population and a smaller quantity of fruit production compared to the eastern region. Additionally, the types of crops cultivated in northern Thailand may be less attractive to elephants than those grown in the east, reducing the likelihood of crop-raiding incidents (DOA Thailand, 2015). A similar seasonal effect has been observed in Cambodia, where HEC follows a trend comparable to that in Thailand. This period coincides with crop growth and ripening, making agricultural fields particularly attractive to elephants (Webber et al., 2011). Notably, the rainy season may increase water availability, drawing elephants toward areas near human settlements where water sources are located (Matsuura et al., 2024; Tiller et al., 2021).

Generally, July to October is recognized as the rainy season in Thailand, during which improved plant growth is expected to provide elephants with more natural forage in the forest. Therefore, HEC occurrences would not be expected to be higher during the rainy season compared to the summer, when food availability in the forest is at its lowest, unless elephants prefer human food over natural forage. This incident was similar in the HEC in India where most wild elephants came to human property for seeking a food during rainy season (Osborn, 2003; Dissanayake and Jayasundara, 2024).

The occurrence of HEC in Thailand significantly decreased between 2019 and 2022. This decline may be attributed to the implementation of several mitigation strategies by the government, NGOs, and local communities aimed at promoting coexistence between humans and wild elephants. These strategies include crop protection methods that involve securing crops from wild elephants (firecrackers, guns to scare elephants) (Sukmasuang et al., 2024), single-strand fencing, beehive fencing (Van de Water and Matteson, 2018), the creation of barrier vegetation, the establishment of buffer zones, and the cultivation of certain plant species as vegetative barriers, such as bamboo groves (DNP, 2023). Additionally, artificial intelligence (AI), referred to as the True Smart Early Warning System (TSEWS), incorporates AI software, an internet network, and security cameras, and has been integrated into systems designed to detect and notify authorities of wild elephant movements in Thailand (True, 2024). Additionally, drone has been developed and used to manage HEC in Thailand by tracking elephant movements, and managing them back to forest (Yindee et al.,2024; Thai PBS, 2024; Vasquez, 2023).

Moreover, the decline in HEC occurrences in this study may also be associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, as strict lockdowns and travel restrictions were implemented, which initially reduced human activity in forest areas, roads, and workplaces (Cukor et al., 2021). This hypothesis is supported by studies in North America (Schrimpf et al., 2021) and Sri Lanka studies, (Graham, 2020) where reduced human activity during COVID-19 lockdowns benefitted wildlife by decreasing disturbances. In Sri Lanka, for instance, the occurrence of HEC also decreased during this period (Graham, 2020). However, after the end of the COVID-19 lockdown in 2023, the national occurrence of HEC rose again, with the northeastern area experiencing the highest number of incidents. This increase is likely due to several factors, including a rise in the wild elephant population and possibly an increase in the production of crops such as rice, maize, tapioca, sugarcane, and natural rubber (PRD Thailand, 2023).

5. Conclusion

The present study suggests that HEC in Thailand is a multifactorial issue. The occurrences are strongly associated with specific areas and periods, with the eastern region and the period between July and October exhibiting the highest incidence. Additionally, factors such as crop production, forest area, and the number of wild elephants may influence HEC. Specifically, the eastern region, which has a high wild elephant population, abundant crops that attract elephants, and low forest area, faces a higher risk of HEC. In contrast, the northern region, with fewer elephants, larger forest areas, and lower crop production, is at a lower risk of HEC.

Supplemenatry Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author contributions

CRediT: Jarawee Supanta: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing; Chaithep Poolkhet: Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing; Marnoch Yindee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Resources, Writing – review and editing; Wallaya Manatchaiworakul: Resource, Supervisor, Validation, Writing – review and editing; Tuempong Wongtawan: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the research work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all private news agencies and governmental agencies for providing public data (Thailand Royal Forest Department and Wildlife Conservation Office) to use in this research.

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used QuillBot and ChatGPT in order to proofread the English grammar. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Funding sources

This work was supported by Walailak University under the New Researcher Development scheme (Contract Number WU67269).

References

- Bansiddhi, P., Brown, J.L., Thitaram, C., 2020. Welfare assessment and activities of captive elephants in Thailand. Animals 10, 919. [CrossRef]

- Cukor, J., Linda, R., Mahlerová, K., Vacek, Z., Faltusová, M., Marada, P., Havránek, F., Hart, V., 2021. Different patterns of human activities in nature during Covid-19 pandemic and African swine fever outbreak confirm direct impact on wildlife disruption. Sci. Rep. 11, 20791. [CrossRef]

- Department of Wildlife National Parks and Plant Conservation [DNP]. 2023. Current wild elephant situation in Thailand. Wildlife conservation office, Bangkok. Thailand.

- DOA Thailand. Potential native plant species in the upper Northern. 2015. https://www.doa.go.th/share/showthread.php?tid=2535&pid=2555#pid2555 (accessed March 10, 2025).

- Dissanayake, K.P., Jayasundara, J.A.S.B., 2024.

- Human-elephant conflict: Trauma surgical, critical care, and health economic concerns. Indian J. Surg. 86, 847–848. [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, K., Ganswindt, S.B., Bertschinger, H., Crossey, B., Henley, M.D., Ramahlo, M., Ganswindt, A., 2021.

- Social and seasonal factors contribute to shifts in male African elephant (Loxodonta africana) Foraging and activity patterns in Kruger national park, South Africa. Anim. 11, 3070. [CrossRef]

- Graham, C., 2020. Our wild world in the time of COVID - Global March for Elephants and Rhinos (GMFER) https://gmfer.org/blog/our-wild-world-in-the-time-of-covid/ (accessed March 7, 2025).

- Graham, M., Douglas-Hamilton, I., Adams, W., Lee, P., 2009. The movement of African elephants in a human-dominated land-use mosaic. Anim. Conserv. 12, 445–455. [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, M., Kumaishi, G., Brock, C., Chatterjee, M., Fabiano, E., Katrak-Adefowora, R., Larsen, A., Lockmann, T.M., Roehrdanz, P.R., 2024.

- Effects of climate, land use, and human population change on human-elephant conflict risk in Africa and Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 121, e2312569121. [CrossRef]

- Gunawansa, T.D., Perera, K., Apan, A., Hettiarachchi, N.K., 2023.

- The human-elephant conflict in Sri Lanka: history and present status. Biodivers. Conserv. 32, 3025–3052. [CrossRef]

- Han, J., 2020. The study of Thai elephant culture based on the “Elephant Metaphors” in Thai Idioms. Comp. Lit. East West 3, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.M., Maré, C., Guldemond, R.A.R., Pimm, S.L., van Aarde, R.J., 2024.

- Protecting and connecting landscapes stabilizes populations of the Endangered savannah elephant. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk2896. [CrossRef]

- IUCN Asian Elephant Specialist Group (AsESG), UPSC. BYJUS. 2021. Available online at: https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/asesg-asian-elephant-specialist-group-iucn/ (accessed January 13, 2025).

- Jarungrattanapong, R., Olewiler, N., 2024. Ecosystem management to reduce human–elephant conflict in Thailand. Environ. Dev. Sustain. [CrossRef]

- Kitratporn, N., Takeuchi, W., 2020. Spatiotemporal distribution of human–elephant conflict in Eastern Thailand: A model-based assessment using news reports and remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. 12, 90. [CrossRef]

- Köpke, S., Withanachchi, S.S., Chinthaka Perera, E.N., Withanachchi, C.R., Gamage, D.U., Nissanka, T.S., Warapitiya, C.C., Nissanka, B.M., Ranasinghe, N.N., Senarathna, C.D., Dissanayake, H.R., Pathiranage, R., Schleyer, C., Thiel, A., 2024.

- Factors driving human–elephant conflict: statistical assessment of vulnerability and implications for wildlife conflict management in Sri Lanka. Biodivers. Conserv. 33, 3075–3101. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, I., Pradhan, L., Chatterjee, S., 2024. Challenges and strategies in elephant conservation: A comprehensive review of land use impact and management approaches in Dalma wildlife sanctuary, India. J. Landsc. Ecol. 17, 80–96. [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, N., Nomoto, M., Terada, S., Yobo, C.M., Memiaghe, H.R., Moussavou, G.-M., 2024. Human-elephant conflict in the African rainforest landscape: crop-raiding situations and damage mitigation strategies in rural Gabon. Front. Conserv. Sci. 5. [CrossRef]

- Nampindo, S., Randhir, T.O., 2024. Dynamic modeling of African elephant populations under changing climate and habitat loss across the Greater Virunga landscape. PLos Sustain. Transform. 3, e0000094. [CrossRef]

- Noonto, B., Savini, C., Srikrachang, M. and Maneesrikum, C. 2018.

- Human and elephant voices: Communities responses toward human-elephant conflict management strategies in Thailand. Thailand Research Fund (TRF): Community-based research division (CBR), Bangkok.

- Osborn, F., 2003. Seasonal influence of rainfall and crops on home range expansion by bull elephants. Pachyderm 35, 53–59. [CrossRef]

- Ounlert, P., Sdoodee, S., 2015. The effects of climatic variability on mangosteen flowering date in Southern and Eastern of Thailand. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 11, 617–622. [CrossRef]

- Perera, B., 2009. The human-elephant conflict: A review of current status and mitigation methods. Gajah 30, 41–52.

- PRD Thailand. Moving Northeastern economic corridor toward becoming BCG industry of ASEAN, 2023 https://thailand.prd.go.th/en/content/category/detail/id/48/iid/190814 (accessed March 12, 2025).

- R: The R project for statistical computing, 2023. https:// www.r-project.org (accessed March 6, 2023).

- Saha, S., and Soren, R. (2024). Human-elephant conflict: Understanding multidimensional perspectives through a systematic review. Journal for Nature Conservation, 79, 126586. [CrossRef]

- Schrimpf, M.B., Des Brisay, P.G., Johnston, A., Smith, A.C., Sánchez-Jasso, J., Robinson, B.G., Warrington, M.H., Mahony, N.A., Horn, A.G., Strimas-Mackey, M., Fahrig, L., Koper, N., 2021. Reduced human activity during COVID-19 alters avian land use across North America. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf5073. [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, L.J., Khadka, K.K., Van Den Hoek, J., Naithani, K.J., 2019. Human-elephant conflict: A review of current management strategies and future directions. Front. Ecol. Evol. 6. [CrossRef]

- Sukumar, R., 2006. A brief review of the status, distribution and biology of wild Asian elephants Elephas maximus. Int. Zoo Yearb. 40, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Sukmasuang, R., Phumpakphan, N., Deungkae, P., Chaiyarat, R., Pla-Ard, M., Khiowsree, N., Charaspet, K., Paansri, P., Noowong, J., 2024. Review: Status of wild elephant, conflict and conservation actions in Thailand. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 25. [CrossRef]

- Thai PBS, A must have item “Thermal drone”, fangs and claws to track. Elephant pushing unit. Thai PBS News, 2024 https://www.thaipbs.or.th/news/content/338335 (accessed March 7, 2025).

- Thongkaew, S., Jatuporn, C., Sukprasert, P., Rueangrit, P., Tongchure, S., 2021. Factors affecting the durian production of farmers in the eastern region of Thailand. Int. J. Agric. Ext. 9, 285–293. [CrossRef]

- Tiller, L., Humle, T., Amin, R., Deere, N., Lago, B., Leader-Williams, N., Sinoni, F., Sitati, N., Walpole, M., Smith, R., 2021. Changing seasonal, temporal and spatial crop-raiding trends over 15 years in a human-elephant conflict hotspot. Biol. Conserv. 254, 108941. [CrossRef]

- True Corporation promotes. Tech for good, using the power of technology to improve the quality of life, fostering cooperation with Kui Buri National Park to solve the global problem of human-elephant conflict - True Blog, 2024. https://www.true.th/blog/tech-for-good/ (accessed February 8, 2025).

- Van de Water, A., Matteson, K., 2018. Human-elephant conflict in western Thailand: Socio-economic drivers and potential mitigation strategies. PLos One 13, e0194736. [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, D., 2023. New Paths to Human-elephant coexistence. Wildl. Conserv. Netw. URL https://wildnet.org/new-paths-to-human-elephant-coexistence/ (accessed February 28, 2025).

- Webber, C.E., Sereivathana, T., Maltby, M.P., Lee, P.C., 2011. Elephant crop-raiding and human–elephant conflict in Cambodia: crop selection and seasonal timings of raids. Oryx 45, 243–251. [CrossRef]

- Wettasin, M., Chaiyarat, R., Youngpoy, N., Jieychien, N., Sukmasuang, R., Tanhan, P., 2023. Environmental factors induced crop raiding by wild Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) in the Eastern economic corridor, Thailand. Sci. Rep. 13, 13388. [CrossRef]

- Withanage, W.K.N.C., Gunathilaka, M.D.K.L., Mishra, P.K., Wijesinghe, W.M.D.C., Tripathi, S., 2023. Indexing habitat suitability and human-elephant conflicts using GIS-MCDA in a human-dominated landscape. Geogr. Sustain. 4, 343–355. [CrossRef]

- Yindee, M., Khumngoen, P., Manatchaiworakul, W., and Wongtawan, T. 2024. Modifying a mini drone for remote drug delivery for wildlife medicine. Drone Systems and Applications, 12(1), 1–6. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).