1. Introduction

Heavy metal contamination is a growing environmental and public health concern due to its adverse effects on human health. Among toxic metals, Chromium (Cr), Copper (Cu), Nickel (Ni), Lead (Pb), Aluminum (Al), and Cadmium (Cd) are particularly significant due to their widespread industrial use and persistence in the environment. Chronic exposure to these metals has been associated with various health issues, including neurotoxicity, carcinogenesis, oxidative stress, and immune system dysfunction [

1]. Recent studies have highlighted the role of microRNAs (miRNAs) in mediating cellular responses to heavy metal toxicity, particularly in regulating gene expression related to inflammation, apoptosis, and oxidative stress [

2]

Aluminum (Al), the third most common element in the Earth’s crust, makes up over 8% of the planet’s surface yet it is not necessary for human health and has long been regarded as a safe and non-toxic metal. Researchers are growing increasingly concerned about aluminum’s harmful effects on the human body due to its increasing use and the toxicity mechanisms of aluminum remain incompletely understood. Al is the most common metal in daily life and is widely used in drinking water treatment systems, food additives, antacids, cosmetics, dairy products, and other daily uses. Vaccines also incorporate it as an adjuvant in microscale amounts. Al is neurotoxic and can cause significant cognitive impairment. Its main neurotoxic mechanism is to cause synaptic plasticity reduction and neuronal apoptosis [

3].

miRNAs are a type of regulatory RNAs made up of 19–22 nucleotides. They control gene expression by matching bases with complementary sequences in target messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules. This stops translation of target mRNAs or causes them to be broken down. Evidence from a large body of research suggests that miRNAs may play a role in controlling crucial biological events such as cell proliferation, differentiation, development, and cell death [

4]. Environmental variables, such as pharmaceuticals, hazardous metals, and organic contaminants may influence miRNA function in humans. The toxicant to which the cells are exposed determines the changes in miRNA expression levels. [

5]. Widely used in industrial applications, water treatment, food additives, and medicines, aluminum is the most prevalent metal in the biosphere and the third most abundant element overall [

6].

Welding is a rapidly expanding sector because it is a very effective method of joining metal parts. The health risks associated with welding fumes are faced daily by thousands of welders. Lead, aluminum, titanium, iron, zinc, and cadmium are some of the other probable elements included in the welding electrode. It is also conceivable for the electrode to have 19% chromium, 12% nickel, 3% molybdenum, about 0.8% silicon, and 0.8% manganese [

7]. Multiple studies found robust correlations between ambient metal concentrations and exposure indicators, such as blood and urine metal concentrations. Asthma, bronchitis, pneumoconiosis, lung cancer, neurological diseases, and decreased kidney and reproductive system function are among many possible health problems caused by welding fumes, which are irritating and harmful. Metal particle mechanisms of action on miRNA expression might be better understood with larger-scale research [

8].

During the course of welding the stainless steel, fumes that include nickel (Ni), manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), and chromium (Cr(III)) and chromium (Cr(VI)) compounds that dissolve in different amounts are released. In particular, the respiratory system and neurological system are vulnerable to the potentially harmful consequences of differentiated exposure. Some evidence suggests that soluble intermediate metals cause the molecular mechanism of the effects of welding fumes after inflammation through oxidative stress. Inhaling metal ion combinations with a high reduction potential trigger an oxidative stress reaction in the respiratory system [

9].

miR-19a-3p and miR-19b-3p belong to the miR-17-92 cluster and are known to regulate crucial cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. Studies have shown that exposure to hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] results in the downregulation of miR-19a-3p and miR-19b-3p in human blood samples, suggesting a potential role in chromium-induced carcinogenesis [

10]. Additionally, research has indicated that miR-19a-3p regulates PTEN, a key tumor suppressor gene involved in the AKT signaling pathway, which is often disrupted upon heavy metal exposure [

11].

miR-24-3p is a microRNA that plays a significant role in regulating DNA repair and cellular stress responses. Research has demonstrated that miR-24-3p modulates the cellular response to DNA damage by targeting key proteins involved in apoptosis and DNA repair mechanisms. For instance, miR-24-3p suppresses apoptosis by targeting the pro-apoptotic protein BIM and inhibits homology-directed DNA repair by downregulating BRCA1 expression [

12]. Regarding the p53 signaling pathway, miR-24 has been shown to directly target p53, leading to enhanced cell death under oxidative stress conditions. This interaction suggests that miR-24 can modulate p53 activity, thereby influencing cellular responses to stress and maintaining genomic stability [

13]. While specific studies on the impact of Cr exposure on miR-24-3p expression are limited, it is well-established that exposure to Cr(VI) induces oxidative stress and DNA damage.

Soil, plants, and animals can contain nickel (Ni), a metallic element. Exposure routes, concentration, chemical species, and physical form all have a role in the hazardous effects of nickel and nickel compounds on living beings. Workers in the Ni industries, whether they are manufacturing or utilizing the metal, are more likely to inhale Ni-contaminated air at work than the general population [

14]. Studies have shown that being exposed to harmful metals like lead (Pb) changes the way genes are expressed by affecting epigenetic status. This may then change the harmful effects of Pb. It is interesting to note that more and more research is being done to find out how Pb-related disorders change epigenetic status, mainly by looking at DNA methylation and the expression of non-coding RNAs (nc-RNAs), especially miRNAs. Some inorganic and organic toxicants may cause changes in miRNA expression profiles. This can be a sensitive sign of both short-term and long-term exposure. Chronic lead poisoning is a complicated illness because it takes a long time for the harmful effects of the metal to start affecting people’s health. Genetic and environmental factors that interact with each other make the illness even more complicated. It might be helpful to keep an eye on changes in miRNA expression to guess how cells and the body will react to Pb-induced toxicity [

15].

Cadmium (Cd) has long been known to have detrimental effects on human health [

16]. Lung and kidney damage is the most common adverse effect of Cd exposure [

17]. The molecular mechanism of Cd toxicity has only recently revealed Cd’s involvement in producing epigenetic changes [

16]. In various metal sectors, hexavalent chromium (Cr (VI)) is used. This includes the leather industry, chromium manufacture, electroplating, welding technology, and others [

18]. Cd exposure has been shown to downregulate miR-25-3p expression, leading to the upregulation of its target genes, including AMPK, ULK1, and PTEN. This modulation suggests that miR-25-3p plays a role in Cd-induced autophagy. Additionally, Cd exposure activates heat shock proteins, specifically Hsp70 and Hsp90, which are involved in the oxidative stress response and further mediate autophagy in Cd-treated hepatopancreatic cells [

19].

Copper (Cu) is an element that naturally occurs in living things and has several biological uses, such as promoting healthy development and growth of bones, connective tissues, and organs. In addition to its role in wound healing and injury prevention, it also stimulates the immune system. It is an important part of many enzymes, like cytochrome oxidase and superoxide dismutase, and helps cells communicate and divide [

20]. The link between Cu anomalies and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common form of dementia in the elderly with a complex etiology, is being increasingly studied. There is evidence of a direct link between COMMD1, which controls the Cu pathway and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) HIF-1a in ischemia damage. However, there is not a lot of information available about how Cu is involved in hypoxia in AD right now [

21].

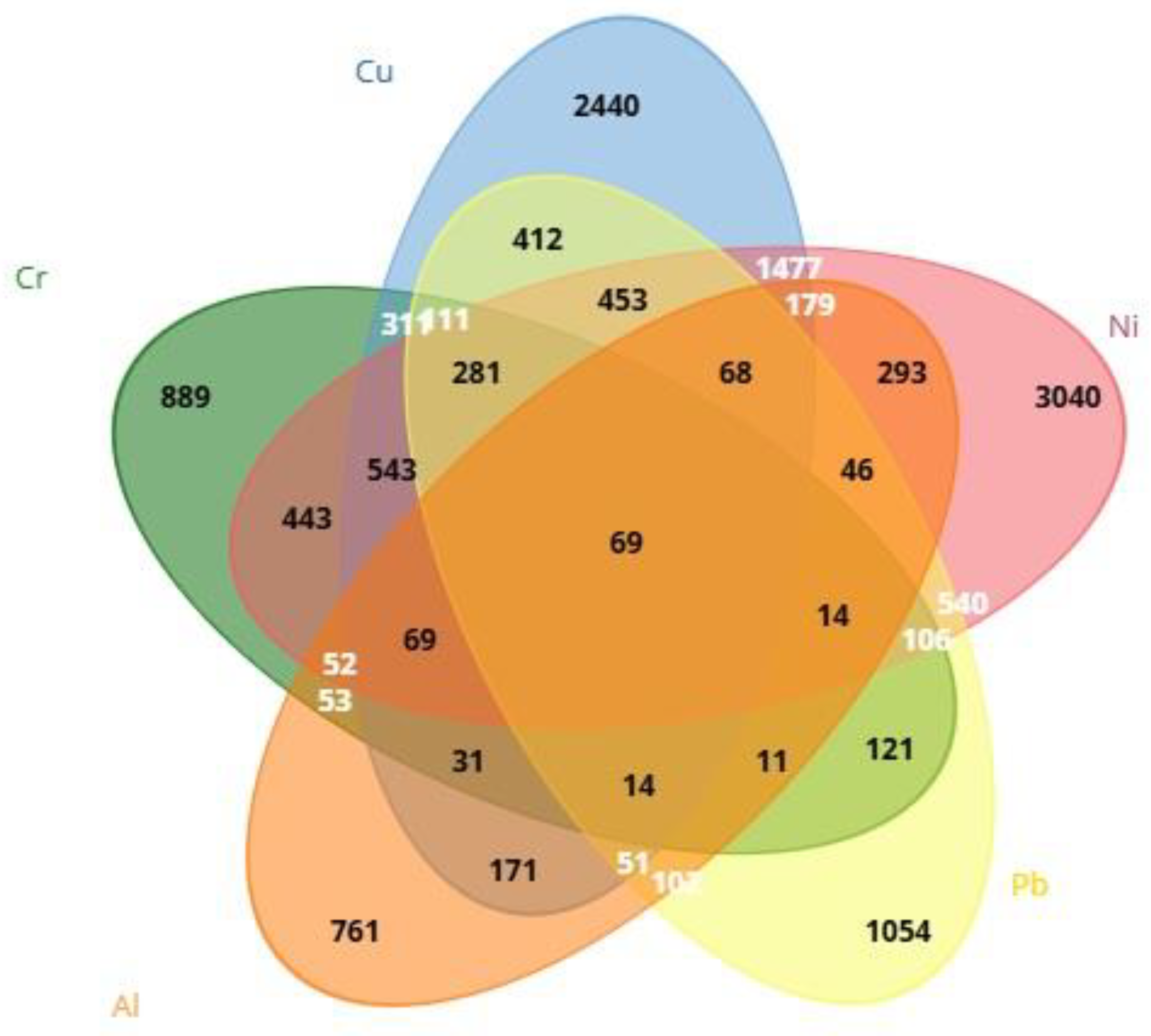

First, the study used web-based bioinformatic tools to perform miRNA selection. We identified genes related to chromium (Cr), nickel (Ni), copper (Cu), lead (Pb), and aluminum (Al) using the comparative toxicogenomics database (CTD) (

https://ctdbase.org/). The Biotools (

https://www.biotools.fr/) website’s Venn Diagrams were used to find genes that are common among heavy metals like Chromium (Cr), Copper (Cu), Nickel (Ni), Lead (Pb), and Aluminum (Al). Then, we used MIENTURNET’s network analysis to assess the connections between target genes and miRNAs.

The aim of the study was to determine whether the expression levels of hsa-miR-19a-3p, hsa-miR-19b-3p, hsa-miR-130b-3p, hsa-miR-25-3p, hsa-miR-363-3p, hsa-miR-92a-3p, and hsa-miR-24-3p genes, which were identified in genes associated with aluminum and welding fume exposure show toxic effects at the genome level in cells. We used the candidate reference gene, hsa-miR-16-5p, as an internal control.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of Cr, Ni, Cu, Pb, and Al-Related Genes Through a Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD)

The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) (

https://ctdbase.org/) was used to find genes linked to Cr, Ni, Cu, Pb, and Al. The CTD is a public database that aims to advance understanding of how environmental exposures affect human health. Chemical gene/protein interactions provide manually curated information on chemical-disease and gene-disease associations.These data are integrated with functional and pathway data to help develop hypotheses about the mechanisms underlying environmentally influenced diseases.

After CTD screening, it was found that 761 genes were linked to Al, 889 genes were linked to Cr, 2440 genes were linked to Cu, 3040 genes were linked to Ni, and 1054 genes were linked to Pb. Using Venn diagrams via the Biotools (

https://www.biotools.fr/) web portal, 69 (ALB, BAX, C3, CASP3, CASP9, CAT, CXCL8, CYP7A1, FOS, GPX1, GSR, HAVCR1, HMOX1, IGF1, IGF2, IL1B, IL4, IL6, JUN, MAPK3, MAPT, MMP2, NFE2L2, PIK3R1, RELA, SLC2A1, SOD1, SOD2, TF, TGFB1, TNF, ACHE, ACSL4, ADH1B, ATF2, BCL2, BCL2L1, CASP12, COL1A1, CRP, CYCS, ELN, ESR1, FDFT1, FDPS, G6PD, GCHFR, IL2, KRT5, LRIG3, LYZ, MAP1LC3B, MCM8, MYC, NAA15, NOS2, PADI2, PINK1, PRKN, PTGS2, PTK2, RPL37, RRM2, SQSTM1, STAT1, TFRC, VEGFA, VIM, XDH69) common genes were detected from heavy metals: Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Al (

Figure 1).

2.2. MIENTURNET (MicroRNA ENrichment TURned NETwork) Analysis

In the present study, MIENTURNET’s network analysis was used to evaluate the relationships between target genes and miRNAs. The MIENTURNET online tool was used to determine which miRNAs were induced by Cr, Ni, Cu, Pb, and Al based on genes associated with heavy metal exposure. We determined the biological significance of these miRNAs by constructing a miRNA target interaction network and performing functional enrichment analysis. miRNAs thought to play a role in Cr, Ni, Cu, Pb, and Al toxicity responses associated with 69 genes were investigated as a result of miRTarBase and TargetScan miRNA-target enrichment analyses.

The threshold value for the minimum number of miRNA-target interactions was taken as 1 and the threshold value for adjusted p value (FDR) was taken as 1. From the analysis results obtained, hsa-miR-19a-3p, hsa-miR-130b-3p, hsa-miR-25-3p, hsa-miR-363-3p, hsa-miR-92a-3p, hsa-miR-24-3p, and hsa-miR-19b-3p miRNAs associated with Cr, Ni, Cu, Pb, and Al toxicity were included in the study. hsa-miR-16-5p was selected as the reference miRNA.

The false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated using the nominal P value obtained from the hypergeometric test.We determined fold enrichment by dividing the genes in a pathway in the list by the background percentage.FDRs tend to be smaller for larger pathways due to increased statistical power. We use this measure to show how strongly a pathway overrepresents certain genes.Using the MIENTURNET miRNA-target enrichment analysis, the best pathways based on FDR were chosen from 69 genes linked to the toxicity of five heavy metals that were part of the study. The pathways were then ranked by fold enrichment, and the best miRNAs were found using miRTarBase (

Table 1) and TargetScan (

Table 2).

Accordingly, hsa-miR-19a-3p was found to have high interactions with ESR1 (Estrogen Receptor 1), TNF (tumor necrosis factor), TF (Transferrin), MYC (MYC Proto-Oncogene, BHLH Transcription Factor), ACSL4 (Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 4), PRKN (Parkin RBR E3 Ubiquitin Protein Ligase) genes, hsa-miR-130b-3p with ESR1, ACSL4, MMP2 (Matrix Metallopeptidase 2), IGF1 (Insulin Like Growth Factor 1) genes, hsa-miR-25-3p with MYC gene, hsa-miR-363-3p with CASP3 (Caspase 3) gene, hsa-miR-92a-3p with CYP7A1 (Cytochrome P450 Family 7 Subfamily A Member 1), GCHFR (GTP Cyclohydrolase I Feedback Regulator), MYC genes, hsa-miR-24-3p with MYC, TGFB1 (Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1), RRM2 (Ribonucleotide Reductase Regulatory Subunit M2), HMOX1 (heme oxygenase 1 gene), IGF1, IL4 (Interleukin-4), IL1B (Interleukin 1 Beta), TNF genes, hsa-miR-19b-3p with ESR1, LRIG3 (Leucine Rich Repeats And Immunoglobulin Like Domains 3), ATF2 (Activating Transcription Factor 2), TGFB1, ACSL4, PRKN genes via miRTarBase database (

Table 1).

In the TargetScan database, it was determined that hsa-miR-19a-3p/hsa-miR-19b-3p had high interaction with ESR1, LRIG3, ATF2, IGF1, ACSL4, HAVCR1 (Hepatitis A Virus Cellular Receptor 1), and SLC2A1 (solute carrier family 2 member 1) genes; hsa-miR-130a-3p with IGF1, ESR1, ACSL4, SLC2A1, and TNF genes; hsa-miR-25-3p/hsa-miR-363-3p/hsa-miR-92a-3p with NAA15 (N-Alpha-Acetyltransferase 15, NatA Auxiliary Subunit) gene; and hsa-miR-24-3p with G6PD (Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase) gene (

Table 2).

2.3. Sample Size

In the study, sample size calculation was done using the ANOVA method, and it was calculated using an open access website as software (

https://homepage.univie.ac.at/robin.ristl/samplesize.phptest=anova).In the calculation method (in miRNA values measured according to the reference miRNA value, in any group with an estimated standard deviation of 0.5 units, a 1-unit difference (Type I error 0.05, Type II error 0.20, power 0.80), the minimum sample size for each group is 16 people. Blood samples were analyzed by taking them from a company that has an occupational physician and regularly follows occupational safety measures and that performs aluminum casting and welding operations. Office workers without any diagnosed diseases and without exposure to aluminum and welding fumes made up the control group.

The Public Health Department of the X Faculty of Medicine evaluated workers who applied to the Occupational Diseases Polyclinic for diagnostic accuracy, took their consent forms and blood samples, and began the study. The study included 16 workers between the ages of 20-55 who were exposed to aluminum and had no disease, 16 workers who were exposed to welding fumes and had no disease, and 16 healthy controls who were known not to have been exposed to aluminum or welding fumes. Istanbul University, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology University Trace Element Analysis Laboratory tested serum samples taken from workers and healthy controls for aluminum and welding fume exposure. The inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) method was used to find out how much of the heavy metals Al, Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, and Pb were in serum samples. The methodological study aims to identify miRNAs potentially associated with heavy metal exposure.

The age range of workers exposed to aluminum is 20-55. The age range of workers exposed to welding fumes is 20-54. The age range of healthy control groups is 32-55. All volunteers participating in the study are male. The X Clinical Research Ethic Committee approved our research on January 8, 2025, with the following number and date: E-29624016-050.99-3104384. Each individual gave their express consent before taking part.

2.4. Serum Preparation

10 ml of venous blood was placed in vacuum-dry blood collection tubes and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. Then, it was first centrifuged at 4ºC at 1900 x g for 10 minutes, and then the upper serum phase was transferred to a new tube and then centrifuged again at 4ºC at 3000 x g for 15 minutes. The completed serum was separated into eppendorf tubes and frozen at -80°C for later use.

2.5. Microwave Acid Extraction

In order to use ICP-OES (Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectrometer) to measure heavy metal levels, serum samples must first be broken down and turned into a solution. First, we used 1 ml of serum samples. The serum sample was put in Teflon containers of a Berghoff wet separation device (Italy) along with 1.9 ml of nitric acid, 2 ml of hydrogen peroxide, and 3 ml of ultrapure water. The samples were heated in a microwave to 130°C for 8 minutes, then 155°C for 5 minutes with 5°C increases, 185°C for 12 minutes with 5°C increases, 100°C for 5 minutes with 5°C increases, and finally 50°C for 5 minutes with a sudden drop in pressure. Acid extraction was then done on the samples.

2.6. ICP-OES Parameters

Quantitative analyses of heavy metals for serum samples were performed using a Perkin Elmer brand Optima 7000DV model ICP-OES device with a concentric nebulizer, standard-section cyclonic spray chamber, alumina injector, and quartz torch. We accepted the relative standard deviation as 10% and carried out nine replicate analyses. We tested the device’s sensitivity and accuracy with heavy metal mixtures of 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, and 5.0 μg/L and an internal standard of 1.0 μg/L manganese. Before analyzing real samples, we performed calibration and determined stability. It was set so that the RF power was 1.3 kW, the nebulizer gas flow rate was 0.6 (L.min-1), the auxiliary gas flow rate was 0.2 (L.min-1), the plasma gas flow rate was 16.0 (L.min-1), the sample aspiration rate was 1.0 (mL.min-1), the platinum element detection wavelengths were 265.945 and 214.423 nm, the argon flow rate was 8 bar, and the nitrogen flow rate was 5 bar.

2.7. RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

miRNAs were isolated from patients’ serum samples and control serum samples using the miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (catalog no. 217204; Qiagen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In order to determine the amount and quality of RNA, the NanoDrop 2000c (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used (A260/A280: 1.8-2.0). cDNA synthesis from samples was performed using miRCURY LNA RT Kit (catalog no. 339340; Qiagen, USA) and Applied Biosystems 2720 Thermal Cycler (California, USA). The expression levels of miRNAs were determined using the miRCURY LNA SYBR Green PCR Kit (catalog no. 339346; Qiagen, USA) and the QIAGEN Rotor-Gene Q. miRNA assay information used for miRCURY LNA miRNA PCR analysis is given in

Table 3.

2.8. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

The Rotor-Gene Q RT-PCR device (Qiagen, USA) received a total reaction volume of 10 μl from the Qiagen RT2 SYBR Green qPCR mastermix kit, which included 5 μl of 2x miRCURY SYBR green master mix, 1 μl of ddH2O, 1 μl of resuspended PCR primer mix, and 3 μl of cDNA template (diluted 1:30) (

Table 4). hsa-miR 16-5p was selected as the reference gene. The PCR process was performed once.

2.9. Data Analysis and Statistics

The variables obtained from the study at the proportional measurement level are presented as mean, median, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum, and variables at the classificatory measurement level are presented as number and percentage. The distribution of age, working years, and smoking among the three groups, heavy metal analysis results were performed with One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Multiple comparisons after analysis were made with the TUKEY test.

Using Ct data obtained from RT-PCR experiments, fold changes were calculated for each miRNA relative to each reference miRNA in the examined condition by the Livak (2-ΔΔCt) method. Statistical evaluation: ΔCt data were calculated according to hsa-miR-16-5p, which was taken as the reference miRNA in the aluminum, source, and control groups..

hsa-miR-16-5p is frequently utilized as a reference gene in metal exposure studies due to its stable expression across various conditions, including different metal exposures. This stability makes it a reliable normalization control in quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and other gene expression analyses, ensuring accurate comparisons of target miRNA expression levels [33,34].

A comparison of different miRNA values was performed using the Mann Whitney U test according to the study year group and smoking group. Two-way analysis of variance was used to compare the interaction of each miRNA difference value with the smoking year group and study year group.

In terms of occupational health and safety, it is very important to know how accurately individuals exposed to heavy metals can be distinguished from healthy individuals. In the decision-making process, ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) analysis was used to assess the discriminatory power of the test. We conducted the ROC analysis using the licensed software IBM SPSS 30 for Windows, provided by Istanbul University (

https://bilgiislem.istanbul.edu.tr/tr/yalis/Veri%20Analizi/). Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed test, with p < 0.05 considered significant.

4. Discussion

The identification of specific miRNAs, including hsa-miR-19a-3p, hsa-miR-130b-3p, hsa-miR-25-3p, hsa-miR-363-3p, hsa-miR-92a-3p, hsa-miR-24-3p, and hsa-miR-19b-3p, is crucial for understanding the molecular responses to heavy metal exposure. These miRNAs play significant roles in regulating oxidative stress, apoptosis, inflammation, and DNA damage repair, which are key mechanisms of metal-induced toxicity [

1].

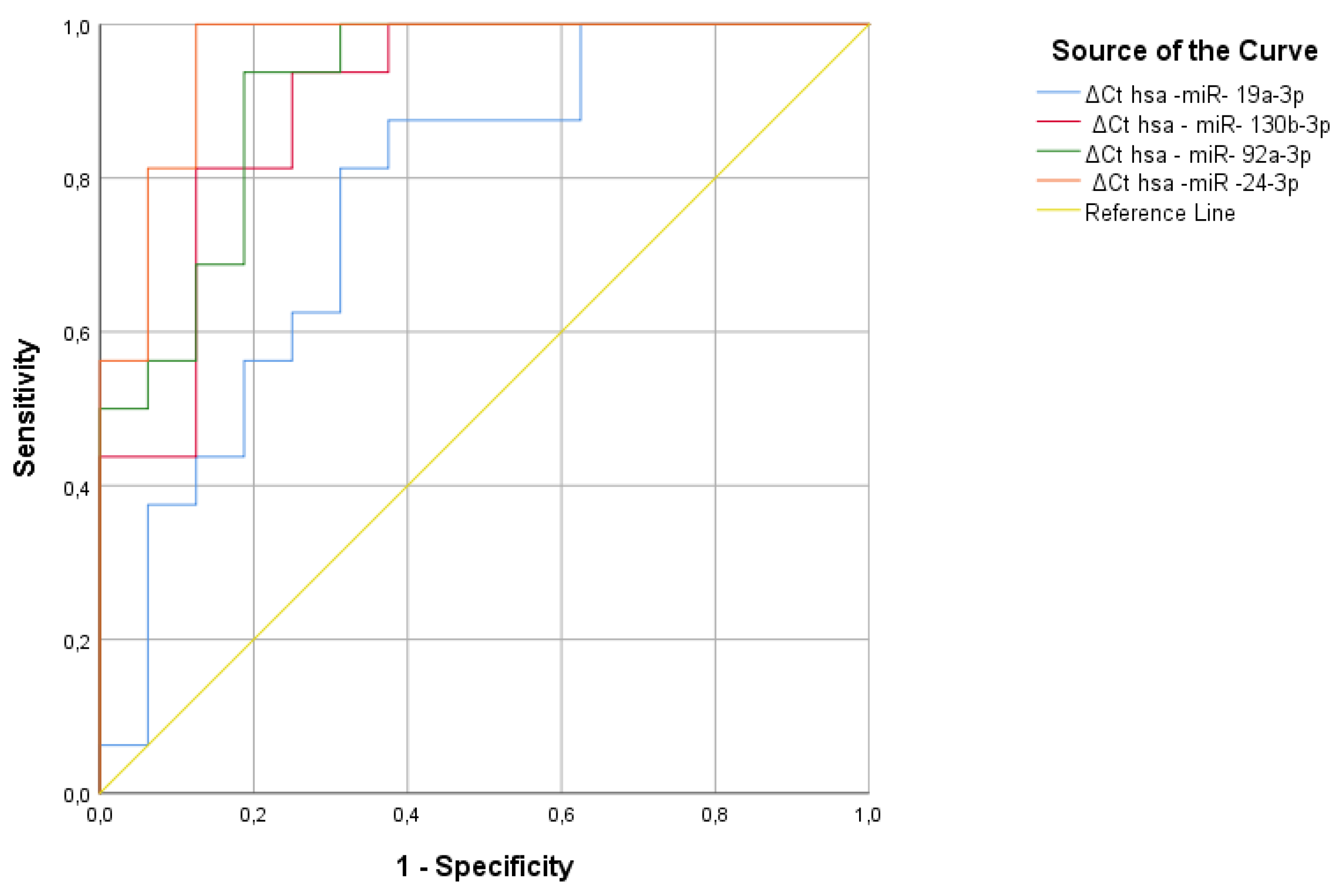

In our study, the qRT-PCR method was used to analyze two serum miRNAs—hsa-miR-19a-3p and hsa-miR-19b-3p—that showed greater significance in aluminum-exposed individuals compared to the reference miRNA, hsa-miR-16-5p. ROC analysis revealed that hsa-miR-19a-3p and hsa-miR-19b-3p were significantly associated with aluminum exposure, as indicated by the area under the curve. Additionally, we identified four serum miRNAs—hsa-miR-19a-3p, hsa-miR-130b-3p, hsa-miR-92a-3p, and hsa-miR-24-3p—as significant in individuals exposed to welding fumes, compared to the reference miRNA, hsa-miR-16-5p. According to ROC analysis, hsa-miR-19a-3p, hsa-miR-130b-3p, hsa-miR-92a-3p, and hsa-miR-24-3p were significantly identified in individuals exposed to welding fumes, while the remaining miRNAs fell under the curve.

We observed that the expression levels of seven miRNAs obtained from serum were decreased (down-regulated) in both aluminum-exposed and welding fume-exposed workers. Our study suggests that hsa-miR-19a-3p may be an important biomarker for both aluminum exposure (p = 0.009) and welding fume exposure (p = 0.010).

MiRNA-target enrichment analysis of hsa-miR-19a-3p, hsa-miR-19b-3p, and hsa-miR-363-3p, which were found to be significant in aluminum-exposed workers, revealed strong interactions of hsa-miR-19a-3p and hsa-miR-363-3p with the ESR1, TNF, TF, MYC, ACSL4, PRKN, and CASP3 genes. Additionally, hsa-miR-19b-3p, which was identified as significant in workers exposed to both aluminum and welding fumes, exhibited high interaction with the ESR1, LRIG3, ATF2, TGFB1, ACSL4, and PRKN genes. Furthermore, hsa-miR-130b-3p, hsa-miR-25-3p, hsa-miR-92a-3p, and hsa-miR-24-3p, which were found to be significant in workers exposed to welding fumes, showed strong interactions with multiple genes, including ESR1, ACSL4, MMP2, IGF1, MYC, CYP7A1, GCHFR, TGFB1, RRM2, HMOX1, IGF1, IL4, IL1B, and TNF.

In our study, hsa-miR-19a-3p and hsa-miR-19b-3p were found to be decreased in workers exposed to aluminum (p < 0.05). Our study observed weak positive correlations between aluminum exposure and hsa-miR-19a-3p, hsa-miR-19b-3p, hsa-miR-130b-3p, hsa-miR-25-3p, hsa-miR-92a-3p, hsa-miR-24-3p (p < 0.05). Research indicates that exposure to aluminum, particularly in the form of aluminum-maltolate, leads to the downregulation of both miR-19a and miR-19b in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. This downregulation is associated with increased neural cell apoptosis. The mechanism involves the modulation of apoptotic-related proteins, including PTEN, p-AKT, and p53. Inhibition of miR-19a or miR-19b alone has been shown to decrease cell viability and activate caspase 9 and caspase 3, further promoting apoptosis. These findings suggest that maintaining the expression levels of miR-19a and miR-19b is crucial for neuronal cell survival under aluminum exposure [

6]. Due to the downregulation of miR-19a-3p and miR-19b-3p, aluminum exposure is associated with an increase in neural cell apoptosis.

Research indicates that oxidative stress can lead to the downregulation of miR-92a-3p. In the study by Li et al., it was found that, in endothelial cells, exosomes stimulated by oxidative stress decreased miR-92a-3p levels and promoted angiogenesis through the modulation of proteins such as PTEN, p-AKT, and p53 [

22]. Altered miR-92a-3p levels have been observed in neurodegenerative diseases. Studies have reported downregulation of miR-92a-3p in plasma samples from patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting its potential role in synaptic function deficits associated with these conditions [

23]. These findings suggest that miR-92a-3p plays a role in cellular stress responses and neurological processes, which could be relevant to understanding its potential involvement in aluminum-induced toxicity.

In our study, hsa-miR-19a-3p, hsa-miR-130b-3p, hsa-miR-92a-3p, and hsa-miR-24-3p were found to be decreased in workers exposed to welding fumes (p < 0.05). We observed weak positive correlations between chromium exposure and hsa-miR-363-3p and hsa-miR-92a-3p (r = 0.383 and 0.363, respectively; p < 0.05). For instance, hsa-miR-19a-3p and hsa-miR-19b-3p, both members of the miR-17-92 cluster, are known to regulate PTEN, a key tumor suppressor gene involved in the AKT pathway. Exposure to hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] has been shown to downregulate these miRNAs, leading to enhanced carcinogenic potential due to increased AKT activation and reduced apoptosis [

24].

Recent studies have identified a connection between chromium exposure and the downregulation of miR-19a-3p. Specifically, research involving workers exposed to Cr (VI) revealed a significant reduction in miR-19a-3p expression levels. This downregulation was accompanied by decreased levels of miR-19b-3p and miR-142-3p, while miR-590-3p and miR-941 were upregulated in the exposed group. These findings suggest that miR-19a-3p, along with other microRNAs, may serve as potential biomarkers for chromium exposure and its associated health effects [

25]. Observed changes in miRNA expression, including downregulation of miR-19a-3p, may lead to various health problems. miR-19a-3p has been shown to play a role in endothelial function, and its overexpression protects against atherosclerosis-associated endothelial dysfunction.Therefore, its downregulation in response to chromium exposure could potentially exacerbate vascular health problems [

26]. So, we can say that chromium exposure is linked to miR-19a-3p downregulation, which could affect the health of blood vessels and be used as a biomarker to measure exposure.

Hsa-miR-24-3p plays a significant role in regulating cellular stress responses, including DNA damage repair and apoptosis. Studies have shown that decreased miR-24-3p expression correlates with increased susceptibility to apoptosis and emphysema, particularly in the context of cigarette smoke exposure [

12]. Given that Cr(VI) is a known human carcinogen associated with lung cancer and can induce oxidative stress and DNA damage [

27], it’s plausible that chromium exposure might influence miR-24-3p expression. Despite the significant role miR-24-3p plays in cellular stress responses, more research is required to understand how it reacts to chromium exposure.

We found negative, weak correlations between copper values and hsa-miR-363-3p (r=0.295; p=0.042). miR-363-3p is a microRNA involved in regulating various cellular processes, including inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. Studies have demonstrated that miR-363-3p can reduce endothelial cell inflammatory responses by targeting NADPH oxidase 4 and inhibiting the p38 MAPK signaling pathway, thereby decreasing oxidative stress and cell apoptosis [

28]. Regarding copper exposure, there is no literature information linking it to miR-363-3p expression, and it is known that copper can cause oxidative stress and inflammation.

Our study observed positive weak correlations between lead exposure and hsa-miR-130b-3p, hsa-miR-92a-3p, and hsa-miR-24-3p (p < 0.05). Lead exposure is known to induce epigenetic modifications, including alterations in miRNA expression, which can contribute to neurotoxicity and immune dysfunction [

29]. Studies have shown that miR-19a-3p and miR-19b-3p are upregulated after spinal cord injury, leading to increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines and decreased expression of nuclear receptors Nurr1 and Nur77 in microglia. This suggests that miR-19a-3p and miR-19b-3p contribute to neuroinflammation and neuropathic pain by modulating microglial activation [

30]. It has been shown that miR-130b-3p may control fibroblast activities by focusing on the 3’-UTR of IGF-1 mRNA. This can change the way epithelial and mesenchymal cells talk to each other in lung fibrosis [

31]. Given the roles of miR-19a-3p and miR-19b-3p miRNAs in regulating inflammatory responses and oxidative stress in relation to lead exposure, it is possible that changes in their expression may affect cellular responses to lead-induced neurotoxicity.

“We found no statistically significant correlation (p > 0.05) between the Ct values of the seven miRNAs we investigated and serum nickel levels. hsa-miR-24-3p plays a role in regulating dendritic cell (DC) activation. miR-24-3p has been shown to be upregulated in DCs when exposed to contact allergens and plays a role in immune activation [

32]. Nickel is a known contact allergen that can trigger immune responses. Therefore, it is likely that Ni exposure upregulates hsa-miR-24-3p in DCs, leading to increased immune activation and potentially contributing to allergic reactions. In contrast, in our study, since serum samples were used, hsa-miR-24-3p was downregulated. This discrepancy may be due to differences in exposure levels and biological matrices.

Nickel exposure is known to cause oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis. However, there are limited studies in the literature on nickel exposure. The known functions of miR-19a-3p and miR-130b-3p suggest that their downregulation may exacerbate the adverse effects associated with nickel exposure, such as increased inflammation, fibrosis, and cellular senescence.

Combining tests that assess occupational exposure with those that detect miRNA biomarkers can help determine the role of genetics in occupational diseases. This study underscores the importance of utilizing miRNAs as biomarkers and incorporating them into routine genetic testing programs in workplaces. Although implementing such programs may be costly, they offer significant benefits in preventing occupational diseases. By focusing on seven specific miRNAs, this research aims to identify new biomarkers, enabling the early detection of diseases caused by heavy metal exposure. Furthermore, the findings will provide valuable insights for establishing necessary workplace safety measures to protect employees.

However, this study has certain limitations. First, the participants were currently employed and had not been diagnosed with any occupational diseases. They belonged to a workforce with established occupational safety measures and were continuously monitored by an occupational physician. Second, the heavy metal analyses in this study were based on a single blood measurement, conducted using ICP-OES, one of the most reliable methods available. Due to financial constraints, we were unable to validate the results using an alternative measurement technique. Additionally, the analyzed heavy metals have relatively short half-lives in the human body. While blood lead levels in welding workers were higher than those in the control and aluminum-exposed groups, they were not elevated enough to diagnose an occupational disease.

Another limitation was the small sample size. Future studies should include larger cohorts and more comprehensive data collection to enhance the reliability of these findings. Validation in an independent, large-scale cohort is essential to assess the potential of these miRNAs as biomarkers for heavy metal toxicity. Cross-validation with larger datasets will further confirm the consistency and specificity of the observed dysregulation patterns in occupationally exposed workers. Integrating these miRNAs into occupational health surveillance programs could improve the early detection of heavy metal-induced health risks, facilitating timely interventions.

In conclusion, miR-19a-3p, miR-130b-3p, miR-25-3p, miR-363-3p, miR-92a-3p, miR-24-3p, and miR-19b-3p play critical roles in cellular responses to heavy metal exposure. These miRNAs regulate key pathways involved in oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, and DNA damage repair. The dysregulation of these miRNAs upon exposure to toxic metals such as Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, Al, and Cd underscores their potential as biomarkers for metal-induced toxicity and disease progression. Further research is necessary to elucidate their precise mechanisms and therapeutic applications in mitigating heavy metal-induced health risks.

Figure 1.

Evaluation of genes associated with Cr, Ni, Cu, Pb, and Al using a Venn diagram.

Figure 1.

Evaluation of genes associated with Cr, Ni, Cu, Pb, and Al using a Venn diagram.

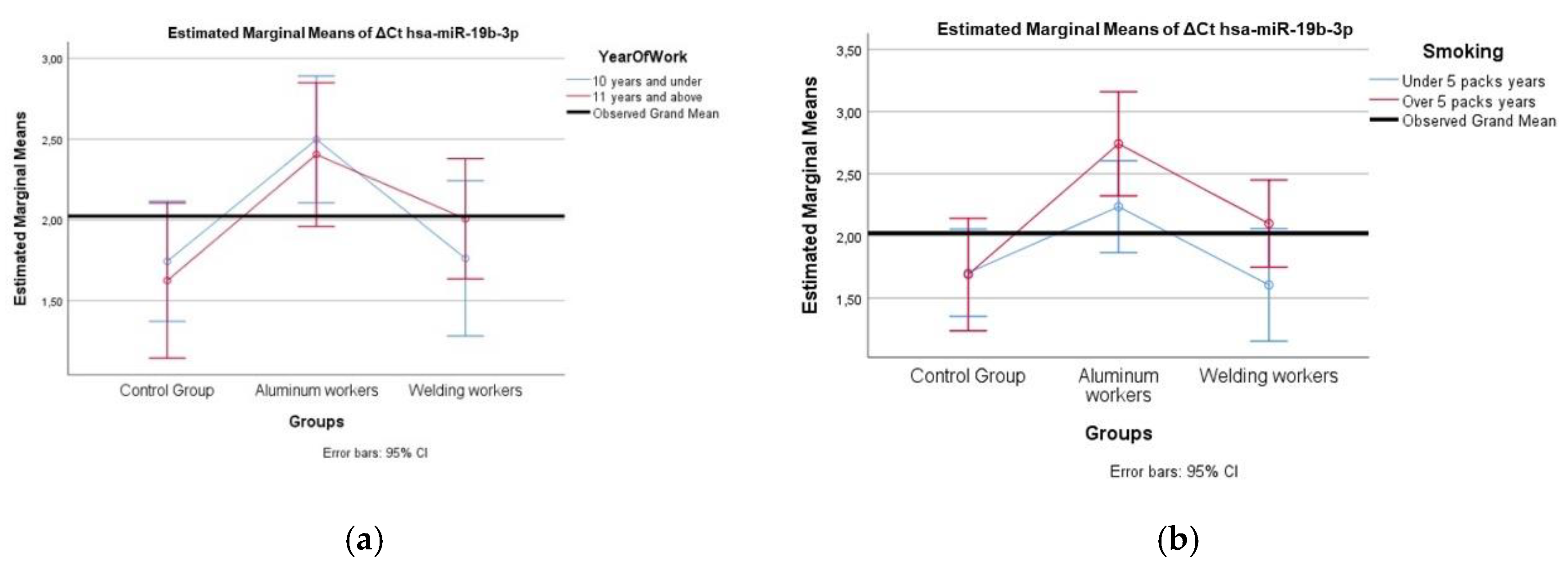

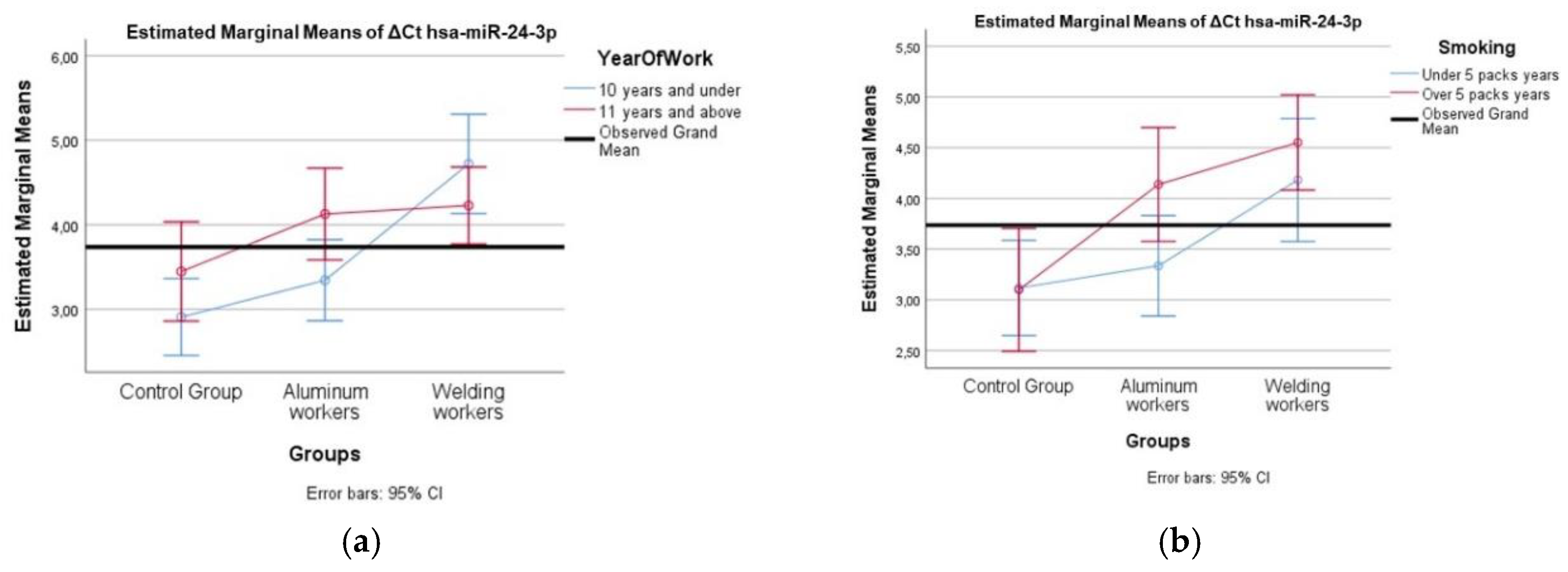

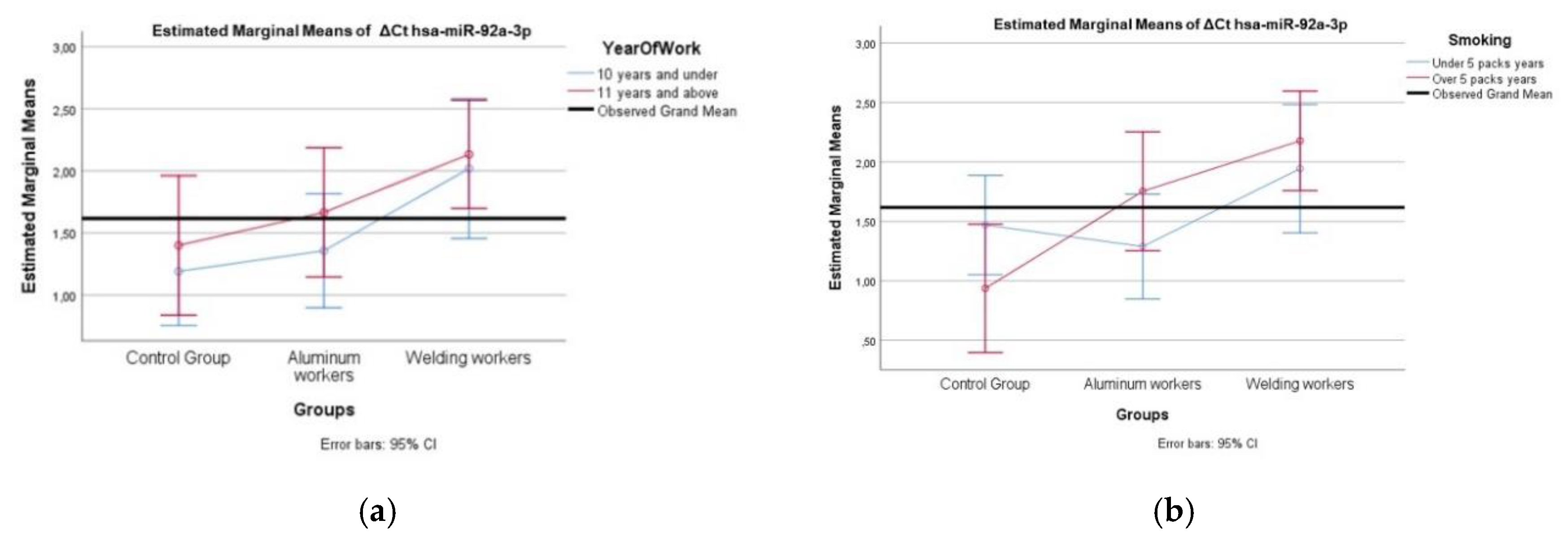

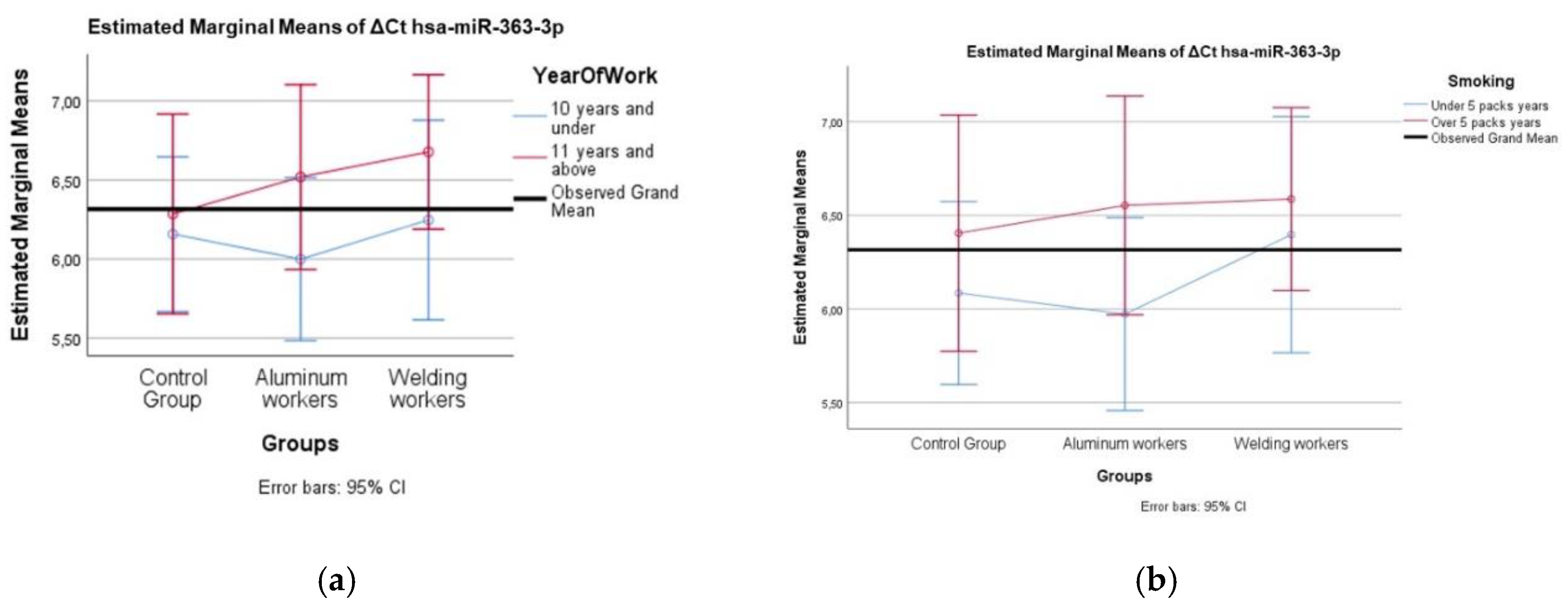

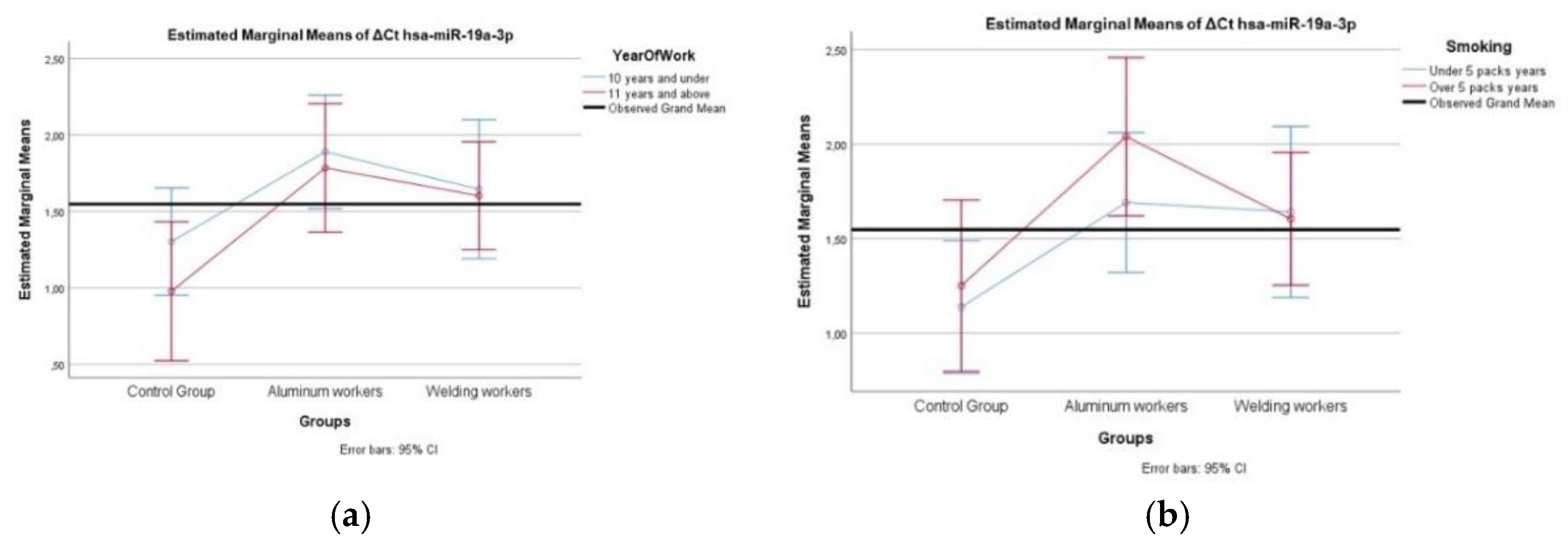

Figure 2.

(a) Two-way interaction in hsa-miR-19a-3p by group and study year (F=0.27; p=0.76) ; (b) Two-way interaction in hsa-miR-19a-3p by group and smoking year (F=0.48; p=0.82).

Figure 2.

(a) Two-way interaction in hsa-miR-19a-3p by group and study year (F=0.27; p=0.76) ; (b) Two-way interaction in hsa-miR-19a-3p by group and smoking year (F=0.48; p=0.82).

Figure 7.

Significant miRNA values in aluminum workers compared to the control group.

Figure 7.

Significant miRNA values in aluminum workers compared to the control group.

Figure 8.

Significant miRNA values in welding workers compared to the control group.

Figure 8.

Significant miRNA values in welding workers compared to the control group.

Figure 9.

Displaying the distribution of values for selected samples as a boxplot.

Figure 9.

Displaying the distribution of values for selected samples as a boxplot.

Table 1.

MIENTURNET enrichment results in Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Al (via miRTarBase).

Table 1.

MIENTURNET enrichment results in Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Al (via miRTarBase).

| microRNA |

p-value |

FDR |

Odd ratio |

Number of interactions |

Target Genes |

| hsa-miR-19a-3p |

0,0437 |

0,33 |

0,43 |

6 |

ESR1, TNF, TF, MYC, ACSL4, PRKN |

| hsa-miR-130b-3p |

0,257 |

0,523 |

0,644 |

4 |

ESR1, ACSL4, MMP2, IGF1 |

| hsa-miR-25-3p |

0,908 |

0,91 |

2,34 |

1 |

MYC |

| hsa-miR-363-3p |

0,791 |

0,8 |

1,54 |

1 |

CASP3 |

| hsa-miR-92a-3p |

0,959 |

0,959 |

2,12 |

3 |

CYP7A1, GCHFR, MYC |

| hsa-miR-24-3p |

0,038 |

0,33 |

0,482 |

8 |

MYC, TGFB1, RRM2, HMOX1, IGF1, IL4, IL1B, TNF |

| hsa-miR-19b-3p |

0,103 |

0,418 |

0,537 |

6 |

ESR1, LRIG3, ATF2, TGFB1, ACSL4, PRKN |

Table 2.

MIENTURNET enrichment results in Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Al (via TargetScan).

Table 2.

MIENTURNET enrichment results in Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Al (via TargetScan).

| microRNA |

p-value |

FDR |

Odd ratio |

Number of interactions |

Target Genes |

| hsa-miR-19a-3p/hsa-miR-19b-3p |

0,3 |

0,954 |

0,778 |

7 |

ESR1, LRIG3, ATF2, IGF1, ACSL4, HAVCR1, SLC2A1 |

| hsa-miR-130a-3p |

0,408 |

0,954 |

0,837 |

5 |

IGF1, ESR1, ACSL4, SLC2A1, TNF |

| hsa-miR-25-3p/hsa-miR-363-3p/ hsa-miR-92a-3p |

0,988 |

0,988 |

4,23 |

1 |

NAA15 |

| hsa-miR-24-3p |

0,959 |

0,982 |

3,09 |

1 |

G6PD |

Table 3.

miRNA assay list.

Table 3.

miRNA assay list.

| miRNA Symbol |

Assay Catolog |

Lot Number |

| hsa-miR-19a-3p |

YP00205862 |

201803080052-4 |

| hsa-miR-19b-3p |

YP00204450 |

31201015-3 |

| hsa-miR-130b-3p |

YP00204317 |

41000618-1 |

| hsa-miR-25-3p |

YP00204361 |

40301621-2 |

| hsa-miR-363-3p |

YP00204726 |

201803060217-1 |

| hsa-miR-92a-3p |

YP00204258 |

40805431-3 |

| hsa-miR-24-3p |

YP00204260 |

31200624-2 |

| hsa-miR-16-5p |

YP00205702 |

40501706-1 |

Table 4.

PCR cycling conditions.

Table 4.

PCR cycling conditions.

| Cycles |

Duration |

Temperature |

Program name |

| 1 |

2 min. |

950C |

PCR initial heat activation |

| 45 |

15 sec. |

950C |

Denaturation |

| 60 sec. |

560C |

Combined annealing/extension |

| 1 |

|

600C

950C |

Melting curve analysis |

Table 5.

Age, working years and smoking distribution of the people included in the study.

Table 5.

Age, working years and smoking distribution of the people included in the study.

| Descriptives |

|

n |

Mean |

Std.

Deviation |

95% CI |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Significance |

| |

|

|

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

|

|

F |

p |

| Age(Year) |

Control Group |

16 |

39,69 |

6,39 |

36,29 |

43,09 |

32 |

55 |

1,079 |

0,348 |

| |

Aluminum workers |

16 |

38,69 |

10,35 |

33,17 |

44,20 |

20 |

55 |

|

|

| |

Welding workers |

16 |

35,06 |

10,75 |

29,34 |

40,79 |

20 |

54 |

|

|

| Year of work |

Control Group |

16 |

10,88 |

2,68 |

9,45 |

12,30 |

7 |

16 |

0,241 |

0,787 |

| |

Aluminum workers |

16 |

10,50 |

3,25 |

8,77 |

12,23 |

2 |

15 |

|

|

| |

Welding workers |

16 |

11,50 |

5,75 |

8,44 |

14,56 |

1 |

18 |

|

|

| smoking /pack/year |

Control Group |

16 |

4,81 |

1,76 |

3,87 |

5,75 |

2 |

8 |

2,227 |

0,12 |

| |

Aluminum workers |

16 |

5,38 |

2,03 |

4,29 |

6,46 |

2 |

10 |

|

|

| |

Welding workers |

16 |

6,31 |

2,27 |

5,10 |

7,52 |

2 |

10 |

|

|

Table 6.

Metal Concentration (mg/L) in Controls, Aluminum workers, Welding workers.

Table 6.

Metal Concentration (mg/L) in Controls, Aluminum workers, Welding workers.

| |

|

Control |

|

|

|

Aliminum workers |

|

|

Welding workers |

|

| Descriptive |

Al |

Cr |

Cu |

Ni |

Pb |

Al*

|

Cr |

Cu |

Ni |

Pb¶

|

Al*

|

Cr |

Cu |

Ni |

Pb¶

|

| Mean |

4,932 |

nd |

3,001 |

2,976 |

0,667 |

7,320 |

0,237 |

3,099 |

3,347 |

0,804 |

6,904 |

0,316 |

3,134 |

3,196 |

0,903 |

| Std. Deviation |

0,566 |

nd |

0,165 |

0,342 |

0,068 |

1,630 |

0,191 |

0,334 |

1,264 |

0,104 |

1,998 |

0,145 |

0,168 |

1,500 |

0,084 |

| Median |

4,881 |

nd |

3,025 |

2,900 |

0,653 |

6,980 |

0,172 |

3,183 |

2,896 |

0,824 |

6,489 |

0,298 |

3,130 |

2,632 |

0,890 |

| Minimum |

4,240 |

nd |

2,722 |

2,479 |

0,580 |

5,620 |

0,046 |

2,456 |

2,279 |

0,574 |

4,357 |

0,075 |

2,903 |

2,332 |

0,719 |

| Maximum |

5,810 |

nd |

3,307 |

3,553 |

0,821 |

12,429 |

0,654 |

3,610 |

7,567 |

0,930 |

12,952 |

0,554 |

3,442 |

8,343 |

1,053 |

Table 7.

Correlation coefficients for miRNAs analyzed in relation to heavy metal results.

Table 7.

Correlation coefficients for miRNAs analyzed in relation to heavy metal results.

| . |

Heavy metals |

hsa-miR-19a-3p |

hsa-miR-19b-3p |

hsa-miR-130b-3p |

hsa-miR-25-3p |

hsa-miR-363-3p |

hsa-miR-92a-3p |

hsa-miR-24-3p |

| Al |

Pearson Correlation |

0,319* |

0,413** |

0,356* |

0,304* |

0,183 |

0,354* |

0,411** |

| |

p |

0,027 |

0,003 |

0,013 |

0,036 |

0,214 |

0,014 |

0,004 |

| |

n |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

| Cr |

Pearson Correlation |

-0,225 |

-0,156 |

0,255 |

-0,126 |

0,383* |

0,363* |

0,245 |

| |

p |

0,216 |

0,393 |

0,16 |

0,49 |

0,03 |

0,041 |

0,177 |

| |

n |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

| Cu |

Pearson Correlation |

0,075 |

0,093 |

-0,046 |

0,195 |

-0,295* |

-0,089 |

-0,057 |

| |

p |

0,611 |

0,531 |

0,756 |

0,185 |

0,042 |

0,549 |

0,701 |

| |

n |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

| Ni |

Pearson Correlation |

-0,018 |

0,091 |

0,074 |

-0,006 |

0,047 |

0,032 |

0,014 |

| |

p |

0,902 |

0,537 |

0,616 |

0,967 |

0,753 |

0,829 |

0,923 |

| |

n |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

| Pb |

Pearson Correlation |

0,175 |

0,112 |

0,399** |

0,006 |

0,209 |

0,370** |

0,478** |

| |

p |

0,233 |

0,447 |

0,005 |

0,965 |

0,154 |

0,01 |

0,001 |

| |

n |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

Table 8.

Comparison of mean ΔCt and fold change values between the heavy metal-exposed group and the group without heavy metal exposure (p<0.05).

Table 8.

Comparison of mean ΔCt and fold change values between the heavy metal-exposed group and the group without heavy metal exposure (p<0.05).

| miRNA. |

ΔCt |

ΔΔCt |

2-ΔΔCt

|

Fold Change |

Fold up-or down- regulation |

p value |

p value |

| AE |

WFE |

Non-E |

AE |

WFE |

Non-E |

AE |

WFE |

Non-E |

AE/

Non-E |

WFE/

Non-E |

AE/

Non-E |

WFE/

Non-E |

AE/

Non-E |

WFE/

Non-E |

| hsa-miR-19a-3p |

20,51 |

18,34 |

21,02 |

1,84375 |

1,61875 |

1,18125 |

0,278597 |

0,325617 |

0,440969 |

0,6318 |

0,7384 |

-1,5828 |

-1,3543 |

0,009145 |

0,01051 |

| hsa-miR-19b-3p |

21,12 |

18,64 |

21,72 |

2,456875 |

1,915 |

1,699375 |

0,182141 |

0,265172 |

0,307919 |

0,5915 |

0,8612 |

-1,6906 |

-1,1612 |

0,010407 |

0,243103 |

| hsa-miR-130b-3p |

26,09 |

24,77 |

26,83 |

7,42625 |

8,043125 |

6,80375 |

0,005814 |

0,003791 |

0,008951 |

0,6495 |

0,4236 |

-1,5395 |

-2,361 |

0,572081 |

0,000041 |

| hsa-miR-25-3p |

22,46 |

20,2 |

23,4 |

3,79375 |

3,47375 |

3,376875 |

0,072105 |

0,090011 |

0,096263 |

0,749 |

0,9351 |

-1,335 |

-1,0695 |

0,283009 |

0,547976 |

| hsa-miR-363-3p |

24,89 |

23,24 |

26,23 |

6,22625 |

6,515625 |

6,205 |

0,013357 |

0,01093 |

0,013555 |

0,9854 |

0,8063 |

-1,0148 |

-1,2402 |

0,636084 |

0,08771 |

| hsa-miR-92a-3p |

20,16 |

18,81 |

21,29 |

1,491875 |

2,09 |

1,269375 |

0,35555 |

0,234881 |

0,414839 |

0,8571 |

0,5662 |

-1,1668 |

-1,7662 |

0,849347 |

0,000375 |

| hsa-miR-24-3p |

22,35 |

21,13 |

23,13 |

3,68625 |

4,4125 |

3,11 |

0,077683 |

0,046958 |

0,115824 |

0,6707 |

0,4054 |

-1,491 |

-2,4666 |

0,098174 |

0 |

Table 9.

ΔCt values in the control group according to working years.

Table 9.

ΔCt values in the control group according to working years.

| Groups |

MiRNA |

Years of working |

n |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Z |

Sig. |

| Control Group |

ΔCt hsa-miR-19a-3p |

10 years and under |

10 |

1,30 |

0,36 |

0,90 |

1,94 |

-0,651 |

0,515 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

6 |

0,98 |

0,70 |

0,12 |

1,71 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-19b-3p |

10 years and under |

10 |

1,74 |

0,54 |

0,60 |

2,38 |

-0,434 |

0,664 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

6 |

1,63 |

0,45 |

1,03 |

2,01 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-130b-3p |

10 years and under |

10 |

6,62 |

0,78 |

5,85 |

8,12 |

-1,41 |

0,159 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

6 |

7,11 |

0,76 |

6,09 |

8,17 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-25-3p |

10 years and under |

10 |

3,42 |

0,45 |

2,69 |

4,36 |

-0,76 |

0,447 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

6 |

3,31 |

0,24 |

3,06 |

3,68 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-363-3p |

10 years and under |

10 |

6,16 |

0,97 |

4,53 |

8,28 |

-0,651 |

0,515 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

6 |

6,29 |

0,24 |

6,04 |

6,67 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-92a-3p |

10 years and under |

10 |

1,19 |

0,58 |

-0,10 |

2,12 |

-0,651 |

0,515 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

6 |

1,40 |

0,62 |

0,60 |

2,17 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-24-3p |

10 years and under |

10 |

2,91 |

0,34 |

2,49 |

3,44 |

-2,118 |

0,034 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

6 |

3,45 |

0,49 |

2,87 |

4,24 |

|

|

Table 10.

ΔCt values in the aluminum group according to the working years.

Table 10.

ΔCt values in the aluminum group according to the working years.

| Groups. |

MiRNA |

Years of working |

n |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Z |

Sig. |

| Aluminum workers |

ΔCt hsa-miR-19a-3p |

10 years and under |

9 |

1,89 |

0,92 |

0,96 |

3,58 |

0 |

1 |

| |

|

11years and above |

7 |

1,78 |

0,45 |

1,05 |

2,57 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-19b-3p |

10 years and under |

9 |

2,50 |

0,93 |

0,71 |

3,97 |

-0,159 |

0,874 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

7 |

2,40 |

0,43 |

2,04 |

3,18 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-130b-3p |

10 years and under |

9 |

7,34 |

1,50 |

5,62 |

9,94 |

-0,318 |

0,751 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

7 |

7,53 |

1,66 |

5,25 |

10,07 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-25-3p |

10 years and under |

9 |

3,94 |

1,43 |

2,35 |

6,49 |

-0,742 |

0,458 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

7 |

3,61 |

0,26 |

3,33 |

4,05 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-363-3p |

10 years and under |

9 |

6,00 |

1,12 |

3,36 |

7,41 |

-0,212 |

0,832 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

7 |

6,52 |

0,86 |

5,67 |

7,90 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-92a-3p |

10 years and under |

9 |

1,36 |

0,88 |

-0,30 |

2,91 |

-0,371 |

0,711 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

7 |

1,67 |

1,11 |

0,12 |

3,59 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-24-3p |

10 years and under |

9 |

3,34 |

0,73 |

2,24 |

4,10 |

-1,115 |

0,265 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

7 |

4,13 |

1,28 |

2,77 |

6,80 |

|

|

Table 11.

ΔCt values according to working years in the welding workers group.

Table 11.

ΔCt values according to working years in the welding workers group.

| Groups. |

MiRNA |

Years of working |

n |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Z |

Sig. |

| Welding workers |

ΔCt hsa-miR-19a-3p |

10 years and under |

6 |

1,65 |

0,38 |

1,10 |

2,15 |

-0,435 |

0,664 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

10 |

1,60 |

0,23 |

1,10 |

1,83 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-19b-3p |

10 years and under |

6 |

1,76 |

0,60 |

0,72 |

2,29 |

-0,542 |

0,588 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

10 |

2,01 |

0,30 |

1,52 |

2,44 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-130b-3p |

10 years and under |

6 |

8,20 |

0,87 |

6,91 |

8,96 |

-0,759 |

0,448 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

10 |

7,95 |

0,33 |

7,53 |

8,53 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-25-3p |

10 years and under |

6 |

3,29 |

0,50 |

2,39 |

3,70 |

-1,303 |

0,193 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

10 |

3,58 |

0,24 |

3,12 |

3,87 |

|

|

| |

ΔCthsa-miR-363-3p

|

10 years and under |

6 |

6,25 |

0,30 |

5,76 |

6,66 |

-2,386 |

0,017 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

10 |

6,68 |

0,33 |

5,88 |

7,04 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-92a-3p |

10 years and under |

6 |

2,02 |

0,35 |

1,34 |

2,26 |

-0,326 |

0,745 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

10 |

2,13 |

0,18 |

1,88 |

2,51 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-24-3p |

10 years and under |

6 |

4,72 |

0,84 |

3,53 |

5,77 |

-1,193 |

0,233 |

| |

|

11 years and above |

10 |

4,23 |

0,42 |

3,65 |

4,84 |

|

|

Table 12.

ΔCt values in the aluminum workers group based on smoking years.

Table 12.

ΔCt values in the aluminum workers group based on smoking years.

| Groups |

MiRNA |

Years of Smoking |

n |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Z |

Sig. |

| Control Group |

ΔCt hsa-miR-19a-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

10 |

1,14 |

0,60 |

0,12 |

1,94 |

0 |

1 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

6 |

1,25 |

0,39 |

0,90 |

1,74 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-19b-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

10 |

1,71 |

0,43 |

1,03 |

2,38 |

-0,217 |

0,828 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

6 |

1,69 |

0,64 |

0,60 |

2,37 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-130b-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

10 |

6,79 |

0,81 |

5,85 |

8,12 |

-0,325 |

0,745 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

6 |

6,83 |

0,80 |

5,98 |

8,17 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-25-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

10 |

3,41 |

0,40 |

2,97 |

4,36 |

-0,163 |

0,871 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

6 |

3,33 |

0,38 |

2,69 |

3,70 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-363-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

10 |

6,09 |

0,61 |

4,53 |

6,67 |

-0,054 |

0,957 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

6 |

6,41 |

1,00 |

5,52 |

8,28 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-92a-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

10 |

1,47 |

0,52 |

0,85 |

2,17 |

-1,193 |

0,233 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

6 |

0,94 |

0,58 |

-0,10 |

1,36 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-24-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

10 |

3,12 |

0,58 |

2,49 |

4,24 |

-0,217 |

0,828 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

6 |

3,10 |

0,25 |

2,60 |

3,24 |

|

|

Table 13.

ΔCt values in the aluminum workers group according to smoking years.

Table 13.

ΔCt values in the aluminum workers group according to smoking years.

| Groups. |

MiRNA |

Years of Smoking |

n |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Z |

Sig. |

| Aluminum workers |

ΔCt hsa-miR-19a-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

9 |

1,69 |

0,80 |

0,96 |

3,58 |

-1,218 |

0,223 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

7 |

2,04 |

0,64 |

1,05 |

3,02 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-19b-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

9 |

2,24 |

0,72 |

0,71 |

3,28 |

-1,166 |

0,244 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

7 |

2,74 |

0,68 |

2,04 |

3,97 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-130b-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

9 |

6,98 |

1,18 |

5,62 |

9,29 |

-1,218 |

0,223 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

7 |

8,00 |

1,80 |

5,25 |

10,07 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-25-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

9 |

3,59 |

1,06 |

2,35 |

6,24 |

-1,536 |

0,125 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

7 |

4,06 |

1,10 |

3,33 |

6,49 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-363-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

9 |

5,97 |

1,05 |

3,36 |

6,85 |

-0,053 |

0,958 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

7 |

6,55 |

0,95 |

5,67 |

7,90 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-92a-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

9 |

1,29 |

0,75 |

-0,30 |

2,20 |

-0,371 |

0,711 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

7 |

1,75 |

1,20 |

0,12 |

3,59 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-24-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

9 |

3,34 |

0,73 |

2,24 |

4,10 |

-1,327 |

0,184 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

7 |

4,14 |

1,27 |

2,77 |

6,80 |

|

|

Table 14.

ΔCt values in the welding workers group according to smoking years.

Table 14.

ΔCt values in the welding workers group according to smoking years.

| Groups |

MiRNA |

Years of Smoking |

n |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Z |

Sig. |

| Welding workers |

ΔCt hsa-miR-19a-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

6 |

1,64 |

0,34 |

1,10 |

2,15 |

-0,054 |

0,957 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

10 |

1,61 |

0,26 |

1,10 |

1,88 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-19b-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

6 |

1,61 |

0,49 |

0,72 |

2,11 |

-2,278 |

0,023 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

10 |

2,10 |

0,29 |

1,49 |

2,44 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-130b-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

6 |

7,73 |

0,44 |

6,91 |

8,25 |

-1,41 |

0,159 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

10 |

8,23 |

0,58 |

7,39 |

8,96 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-25-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

6 |

3,20 |

0,47 |

2,39 |

3,72 |

-2,171 |

0,03 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

10 |

3,64 |

0,17 |

3,42 |

3,87 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-363-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

6 |

6,40 |

0,50 |

5,76 |

7,04 |

-0,651 |

0,515 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

10 |

6,59 |

0,28 |

6,12 |

6,98 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-92a-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

6 |

1,94 |

0,34 |

1,34 |

2,30 |

-1,194 |

0,232 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

10 |

2,18 |

0,15 |

1,91 |

2,51 |

|

|

| |

ΔCt hsa-miR-24-3p |

Under 5 packs years |

6 |

4,18 |

0,21 |

3,88 |

4,50 |

-1,085 |

0,278 |

| |

|

Over 5 packs years |

10 |

4,55 |

0,76 |

3,53 |

5,77 |

|

|

Table 15.

Group and study year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-19a-3p.

Table 15.

Group and study year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-19a-3p.

| Tests of Between-Subjects Effects |

|

|

|

|

| Dependent Variable: ΔCt hsa-miR-19a-3p |

|

|

|

| Source |

Type III Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Corrected Model |

4,078a |

5 |

0,816 |

2,684 |

0,034 |

| Intercept |

107,591 |

1 |

107,591 |

354,084 |

p<0,001 |

| Groups |

3,888 |

2 |

1,944 |

6,398 |

0,004 |

| YearOfWork |

0,283 |

1 |

0,283 |

0,933 |

0,34 |

| Groups * YearOfWork |

0,165 |

2 |

0,083 |

0,272 |

0,763 |

| Error |

12,762 |

42 |

0,304 |

|

|

| Total |

131,85 |

48 |

|

|

|

| Corrected Total |

16,84 |

47 |

|

|

|

| a R Squared = 0,242 (Adjusted R Squared = 0,152) |

|

|

|

Table 16.

Group and smoking year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-19a-3p.

Table 16.

Group and smoking year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-19a-3p.

| Dependent Variable: ΔCt hsa-miR-19a-3p |

|

|

|

| Source |

Type III Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Corrected Model |

4,164a |

5 |

0,833 |

2,759 |

0,03 |

| Intercept |

111,479 |

1 |

111,479 |

369,37 |

p<0,001 |

| Groups |

3,524 |

2 |

1,762 |

5,837 |

0,006 |

| Smoking |

0,229 |

1 |

0,229 |

0,76 |

0,388 |

| Groups * Smoking |

0,291 |

2 |

0,146 |

0,483 |

0,62 |

| Error |

12,676 |

42 |

0,302 |

|

|

| Total |

131,85 |

48 |

|

|

|

| Corrected Total |

16,84 |

47 |

|

|

|

| a R Squared = 0,247 (Adjusted R Squared = 0,158) |

|

|

|

Table 17.

Group and study year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-19b-3p.

Table 17.

Group and study year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-19b-3p.

| Tests of Between-Subjects Effects |

|

|

|

| Dependent Variable: ΔCt hsa-miR-19b-3p |

|

|

|

| Source |

Type III Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Corrected Model |

5,188a |

5 |

1,038 |

3,056 |

0,019 |

| Intercept |

184,116 |

1 |

184,116 |

542,354 |

p<0,001 |

| Groups |

4,889 |

2 |

2,444 |

7,201 |

0,002 |

| YearOfWork |

0,001 |

1 |

0,001 |

0,004 |

0,95 |

| Groups * YearOfWork |

0,312 |

2 |

0,156 |

0,46 |

0,634 |

| Error |

14,258 |

42 |

0,339 |

|

|

| Total |

216,033 |

48 |

|

|

|

| Corrected Total |

19,446 |

47 |

|

|

|

| a R Squared = 0,267 (Adjusted R Squared = 0,179) |

|

|

Table 18.

Group and smoking year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-19b-3p.

Table 18.

Group and smoking year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-19b-3p.

| Dependent Variable: ΔCt hsa-miR-19b-3p |

|

|

|

| Source |

Type III Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Corrected Model |

6,795a |

5 |

1,359 |

4,512 |

0,002 |

| Intercept |

185,309 |

1 |

185,309 |

615,25 |

p<0,001 |

| Groups |

5,434 |

2 |

2,717 |

9,02 |

0,001 |

| Smoking |

1,23 |

1 |

1,23 |

4,085 |

0,05 |

| Groups * Smoking |

0,668 |

2 |

0,334 |

1,109 |

0,339 |

| Error |

12,65 |

42 |

0,301 |

|

|

| Total |

216,033 |

48 |

|

|

|

| Corrected Total |

19,446 |

47 |

|

|

|

| a R Squared = 0,349 (Adjusted R Squared = 0,272) |

|

|

Table 19.

Group and study year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-24-3p.

Table 19.

Group and study year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-24-3p.

| Dependent Variable: ΔCt hsa-miR-24-3p |

|

|

|

| Source |

Type III Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Corrected Model |

18,047a |

5 |

3,609 |

7,102 |

p<0,001 |

| Intercept |

658,726 |

1 |

658,726 |

1296,073 |

p<0,001 |

| Groups |

12,695 |

2 |

6,347 |

12,489 |

p<0,001 |

| YearOfWork |

0,876 |

1 |

0,876 |

1,724 |

0,196 |

| Groups * YearOfWork |

3,485 |

2 |

1,742 |

3,428 |

0,042 |

| Error |

21,346 |

42 |

0,508 |

|

|

| Total |

709,452 |

48 |

|

|

|

| Corrected Total |

39,393 |

47 |

|

|

|

| a R Squared = 0,458 (Adjusted R Squared = 0,394) |

|

|

|

Table 20.

Group and smoking year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-24-3p.

Table 20.

Group and smoking year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-24-3p.

| Dependent Variable: ΔCt hsa-miR-24-3p |

|

|

|

| Source |

Type III Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Corrected Model |

16,675a |

5 |

3,335 |

6,165 |

p<0,001 |

| Intercept |

638,494 |

1 |

638,494 |

1180,397 |

p<0,001 |

| Groups |

11,882 |

2 |

5,941 |

10,983 |

p<0,001 |

| Smoking |

1,686 |

1 |

1,686 |

3,118 |

0,085 |

| Groups * Smoking |

1,295 |

2 |

0,647 |

1,197 |

0,312 |

| Error |

22,718 |

42 |

0,541 |

|

|

| Total |

709,452 |

48 |

|

|

|

| Corrected Total |

39,393 |

47 |

|

|

|

| a R Squared = 0,423 (Adjusted R Squared = 0,355) |

|

|

|

Table 21.

Group and study year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-92a-3p.

Table 21.

Group and study year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-92a-3p.

| Dependent Variable: hsa-miR-92a-3p |

|

|

|

| Source |

Type III Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Corrected Model |

6,353a |

5 |

1,271 |

2,728 |

0,032 |

| Intercept |

121,109 |

1 |

121,109 |

260,073 |

p<0,001 |

| Groups |

4,879 |

2 |

2,44 |

5,239 |

0,009 |

| YearOfWork |

0,508 |

1 |

0,508 |

1,092 |

0,302 |

| Groups * YearOfWork |

0,073 |

2 |

0,036 |

0,078 |

0,925 |

| Error |

19,558 |

42 |

0,466 |

|

|

| Total |

151,429 |

48 |

|

|

|

| Corrected Total |

25,911 |

47 |

|

|

|

| a R Squared = 0,245 (Adjusted R Squared = 0,155) |

|

|

Table 22.

Group and smoking year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-92a-3p.

Table 22.

Group and smoking year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-92a-3p.

| Dependent Variable: ΔCt hsa-miR-92a-3p |

|

|

|

| Source |

Type III Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Corrected Model |

7,880a |

5 |

1,576 |

3,671 |

0,008 |

| Intercept |

116,297 |

1 |

116,297 |

270,897 |

p<0,001 |

| Groups |

5,646 |

2 |

2,823 |

6,576 |

0,003 |

| Smoking |

0,035 |

1 |

0,035 |

0,082 |

0,776 |

| Groups * Smoking |

2,073 |

2 |

1,036 |

2,414 |

0,102 |

| Error |

18,031 |

42 |

0,429 |

|

|

| Total |

151,429 |

48 |

|

|

|

| Corrected Total |

25,911 |

47 |

|

|

|

| a R Squared = 0,304 (Adjusted R Squared = 0,221) |

|

|

Table 23.

Group and study year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-363-3p.

Table 23.

Group and study year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-363-3p.

| Dependent Variable: ΔCt hsa-miR-363-3p |

|

|

|

| Source |

Type III Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Corrected Model |

2,783a |

5 |

0,557 |

0,948 |

0,461 |

| Intercept |

1822,848 |

1 |

1822,848 |

3103,541 |

p<0,001 |

| Groups |

0,506 |

2 |

0,253 |

0,43 |

0,653 |

| YearOfWork |

1,476 |

1 |

1,476 |

2,513 |

0,12 |

| Groups * YearOfWork |

0,321 |

2 |

0,16 |

0,273 |

0,762 |

| Error |

24,668 |

42 |

0,587 |

|

|

| Total |

1942,033 |

48 |

|

|

|

| Corrected Total |

27,451 |

47 |

|

|

|

| a R Squared = 0,101 (Adjusted R Squared = -0,006) |

|

|

|

Table 24.

Group and smoking year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-363-3p.

Table 24.

Group and smoking year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-363-3p.

| Dependent Variable: ΔCt hsa-miR-363-3p |

|

|

|

| Source |

Type III Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Corrected Model |

2,811a |

5 |

0,562 |

0,958 |

0,454 |

| Intercept |

1833,992 |

1 |

1833,992 |

3126,066 |

p<0,001 |

| Groups |

0,573 |

2 |

0,286 |

0,488 |

0,617 |

| Smoking |

1,512 |

1 |

1,512 |

2,577 |

0,116 |

| Groups * Smoking |

0,305 |

2 |

0,153 |

0,26 |

0,772 |

| Error |

24,64 |

42 |

0,587 |

|

|

| Total |

1942,033 |

48 |

|

|

|

| Corrected Total |

27,451 |

47 |

|

|

|

| a R Squared = 0,102 (Adjusted R Squared = -0,004) |

|

|

|

Table 25.

Group and study year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-130b-3p.

Table 25.

Group and study year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-130b-3p.

| Dependent Variable: ΔCt hsa-miR-130b-3p. |

|

|

| Source |

Type III Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Corrected Model |

13,546a |

5 |

2,709 |

2,386 |

0,054 |

| Intercept |

2544,052 |

1 |

2544,052 |

2240,406 |

p<0,001 |

| Groups |

11,006 |

2 |

5,503 |

4,846 |

0,013 |

| YearOfWork |

0,224 |

1 |

0,224 |

0,198 |

0,659 |

| Groups * YearOfWork |

1,03 |

2 |

0,515 |

0,454 |

0,638 |

| Error |

47,692 |

42 |

1,136 |

|

|

| Total |

2707,063 |

48 |

|

|

|

| Corrected Total |

61,239 |

47 |

|

|

|

| a R Squared = 0,221 (Adjusted R Squared = 0,128) |

|

|

Table 26.

Group and smoking year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-130b-3p.

Table 26.

Group and smoking year interaction in ΔCt hsa-miR-130b-3p.

| Dependent Variable: ΔCt hsa-miR-130b-3p |

|

|

| Source |

Type III Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

| Corrected Model |

17,363a |

5 |

3,473 |

3,324 |

0,013 |

| Intercept |

2521,983 |

1 |

2521,983 |

2414,175 |

p<0,001 |

| Groups |

10,399 |

2 |

5,2 |

4,977 |

0,011 |

| Smoking |

3,102 |

1 |

3,102 |

2,969 |

0,092 |

| Groups * Smoking |

1,872 |

2 |

0,936 |

0,896 |

0,416 |

| Error |

43,876 |

42 |

1,045 |

|

|

| Total |

2707,063 |

48 |

|

|

|

| Corrected Total |

61,239 |

47 |

|

|

|

| a R Squared = 0,284 (Adjusted R Squared = 0,198) |

|

|

Table 27.

Area under the curve values and their significance for aluminum.

Table 27.

Area under the curve values and their significance for aluminum.

| MiRNAs |

AUC |

Std. Error |

Significance |

95%CI |

| |

|

|

|

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

| hsa-miR-19a-3p |

0.764 |

0.084 |

0.011 |

0.599 |

0.929 |

| hsa-miR-19b-3p |

0.852 |

0.072 |

0.001 |

0.710 |

0.993 |

Table 28.

Sensitivity and specificity values of aluminum workers compared to the control group.

Table 28.

Sensitivity and specificity values of aluminum workers compared to the control group.

| MiRNAs |

Positive if Greater Than or Equal To |

Sensitivity |

1 - Specificity |

Specificity |

Sensitivity + Specificity |

| hsa-miR-19a-3p |

1,47 |

0,69 |

0,31 |

0,69 |

1,38 |

| |

1,59 |

0,69 |

0,25 |

0,75 |

1,44 |

| hsa-miR-19b-3p |

2,03 |

0,88 |

0,19 |

0,81 |

1,69 |

| |

2,08 |

0,75 |

0,19 |

0,81 |

1,56 |

Table 29.

Area under the curve values and their significance.

Table 29.

Area under the curve values and their significance.

| MiRNAs |

Area AUC |

Std. Error |

Significance |

95%CI |

| |

|

|

|

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

| hsa-miR-19a-3p |

0.773 |

0.084 |

0.008 |

0.608 |

0.939 |

| hsa miR-130b-3p |

0.898 |

0.055 |

p<0.001 |

0.790 |

1.000 |

| hsa miR-92a-3p |

0.914 |

0.049 |

p<0.001 |

0.817 |

1.000 |

| hsa miR-24-3p |

0.961 |

0.032 |

p<0.001 |

0.898 |

1.000 |

Table 30.

Sensitivity and specificity values of welding workers compared to the control group.

Table 30.

Sensitivity and specificity values of welding workers compared to the control group.

| MiRNA |

Positive if Greater Than or Equal To |

Sensitivity |

1 - Specificity |

Specificity |

Sensitivity + Specificity |

| hsa miR- 19a-3p |

1.39 |

0.81 |

0.31 |

0.69 |

1.50 |

| |

1,44 |

0,75 |

0,31 |

0,69 |

1,44 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| hsa-miR-130b-3p |

7.61 |

0.81 |

0.19 |

0.81 |

1.63 |

| |

7.67 |

0.81 |

0.13 |

0.88 |

1.69 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| hsa-miR-92a-3p |

1.57 |

0.94 |

0.25 |

0.75 |

1.69 |

| |

1.83 |

0.94 |

0.19 |

0.81 |

1.75 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| hsa-miR-24-3p |

6.39 |

0.69 |

0.25 |

0.75 |

1.44 |

| |

6.46 |

0.63 |

0.25 |

0.75 |

1.38 |