Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Reagents

2.2. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

2.3. Western Blot

3. Results

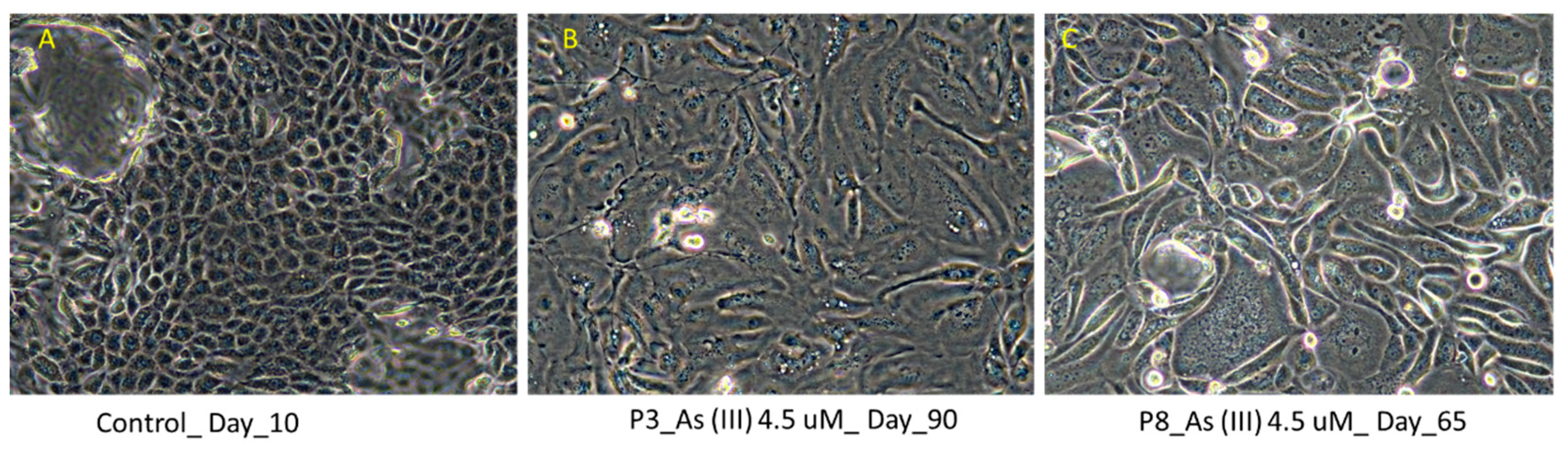

3.1. Light Microscopic Evidence Shows Fibroblast Like Growth in Human Renal Progenitor Cells at P3 and P8

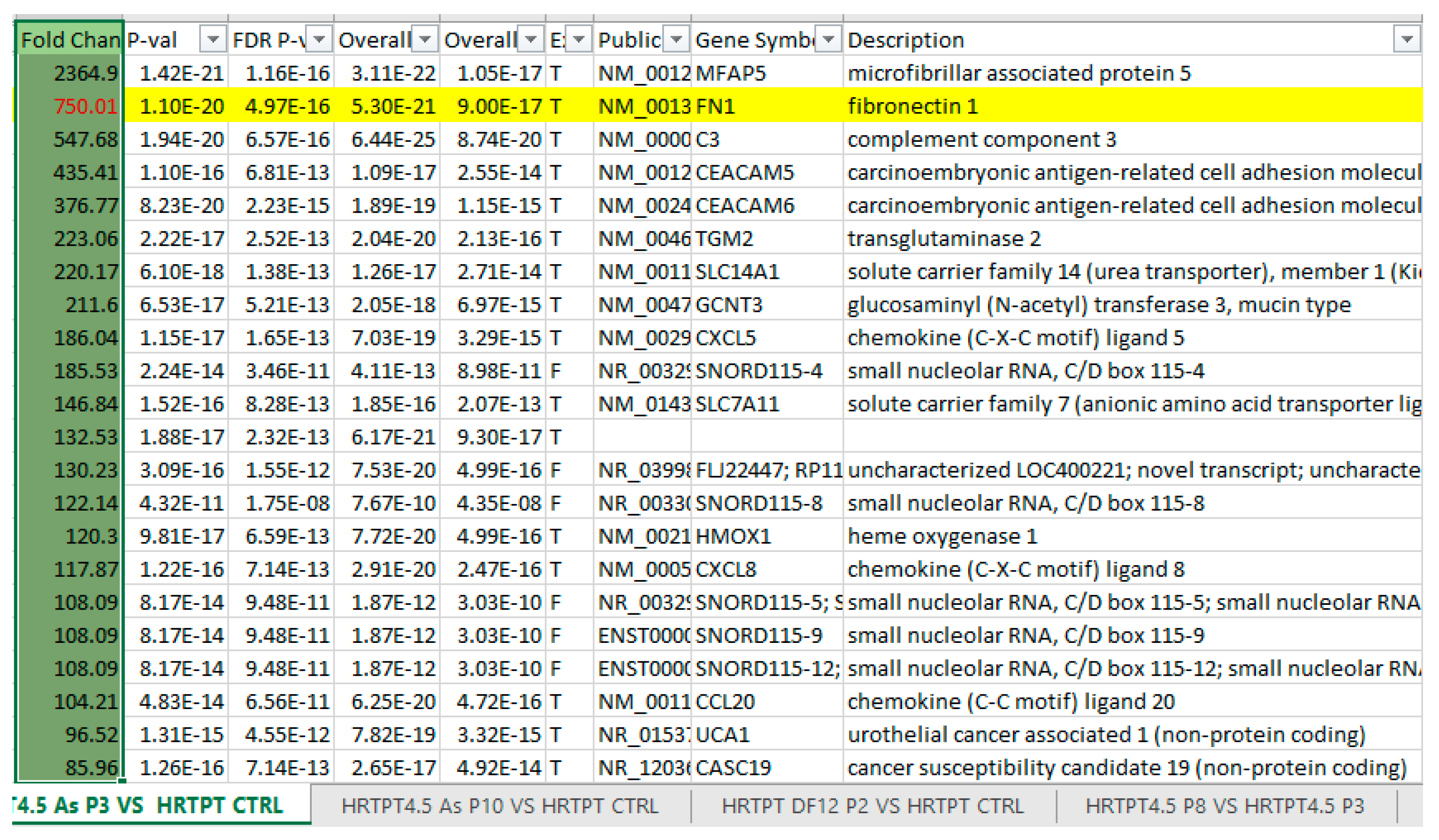

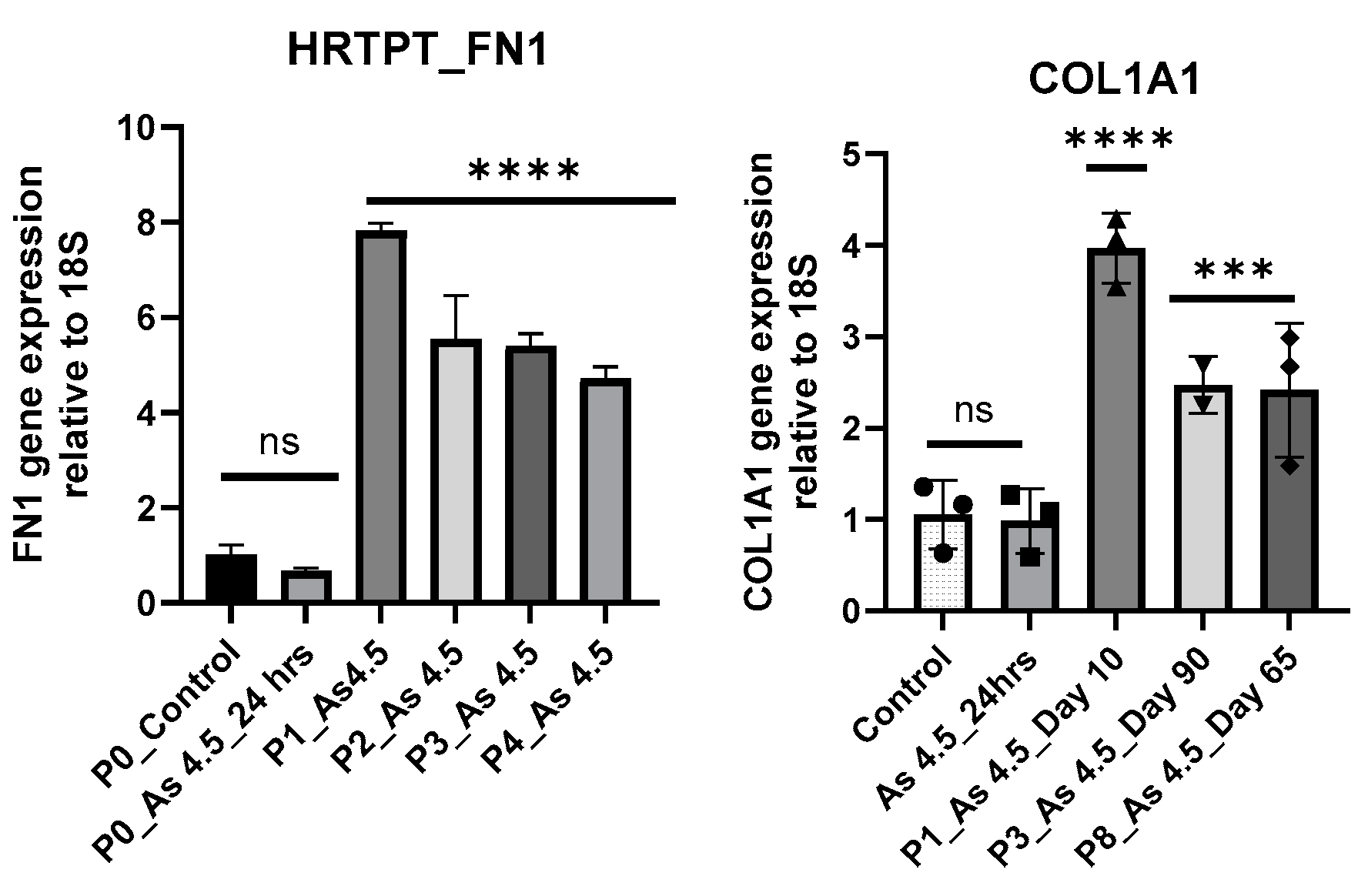

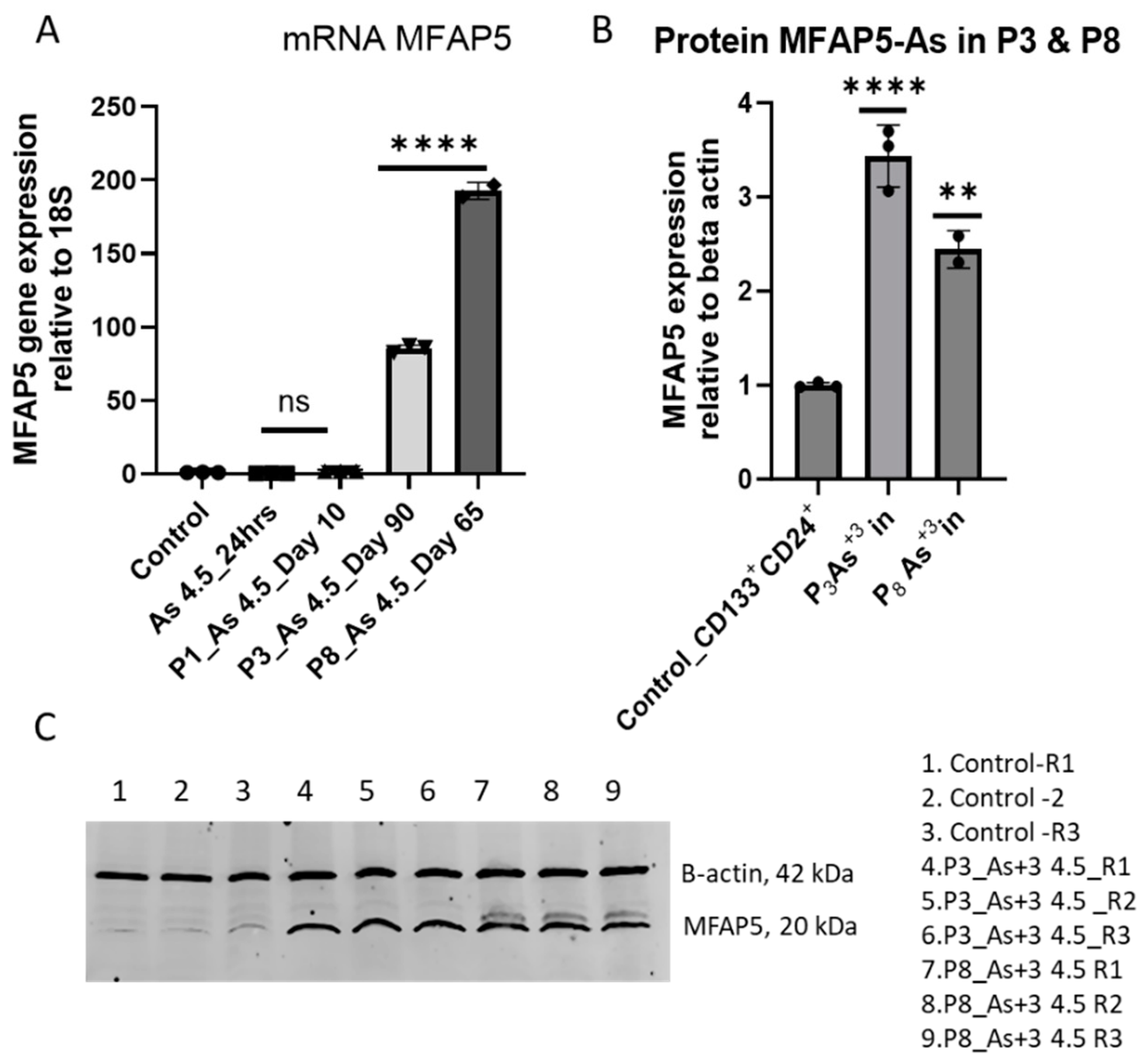

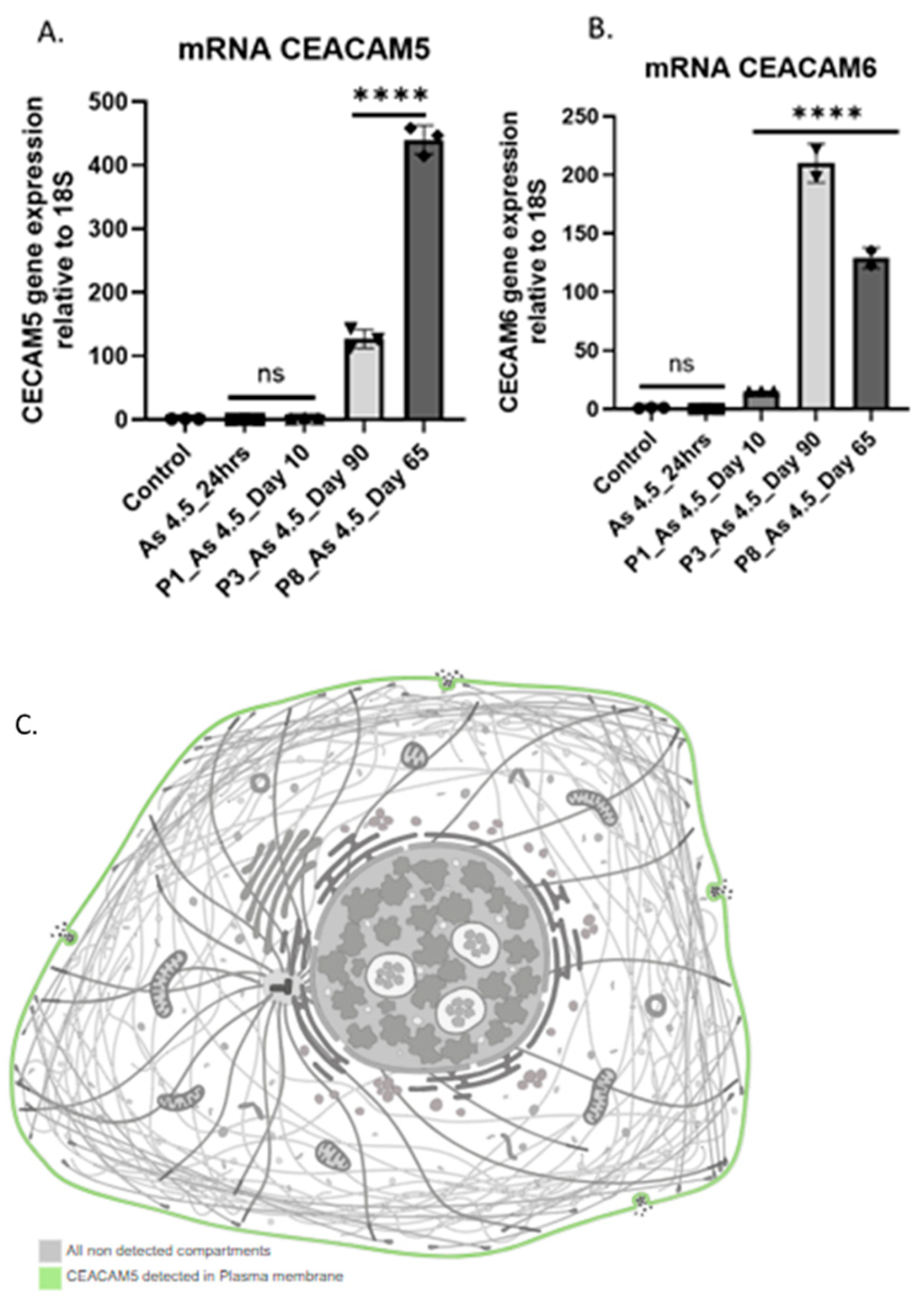

3.2. Arsenite Exposure Increased the Expression of MFAP5, CEACAM 5, and CEACAM 6.

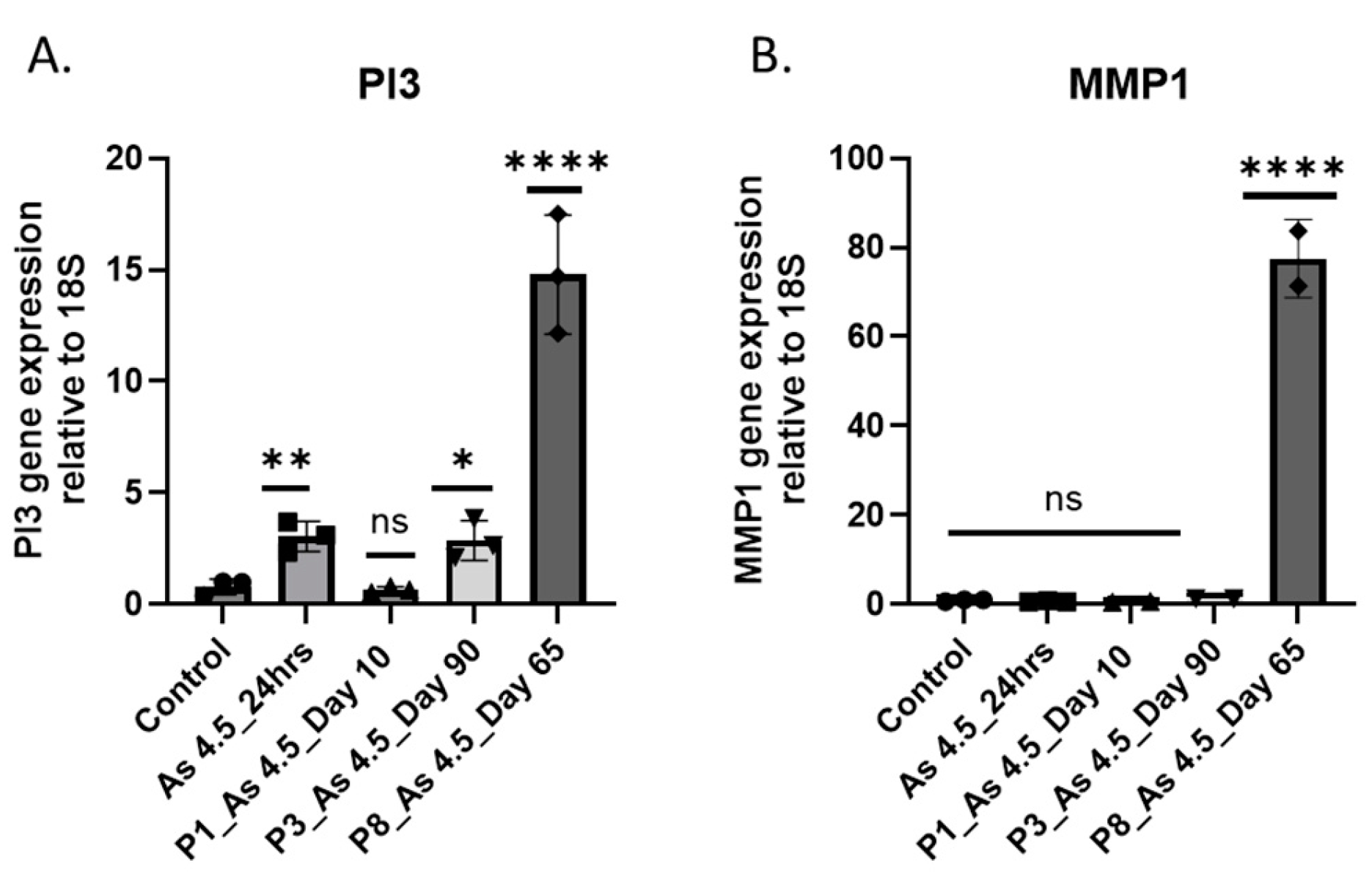

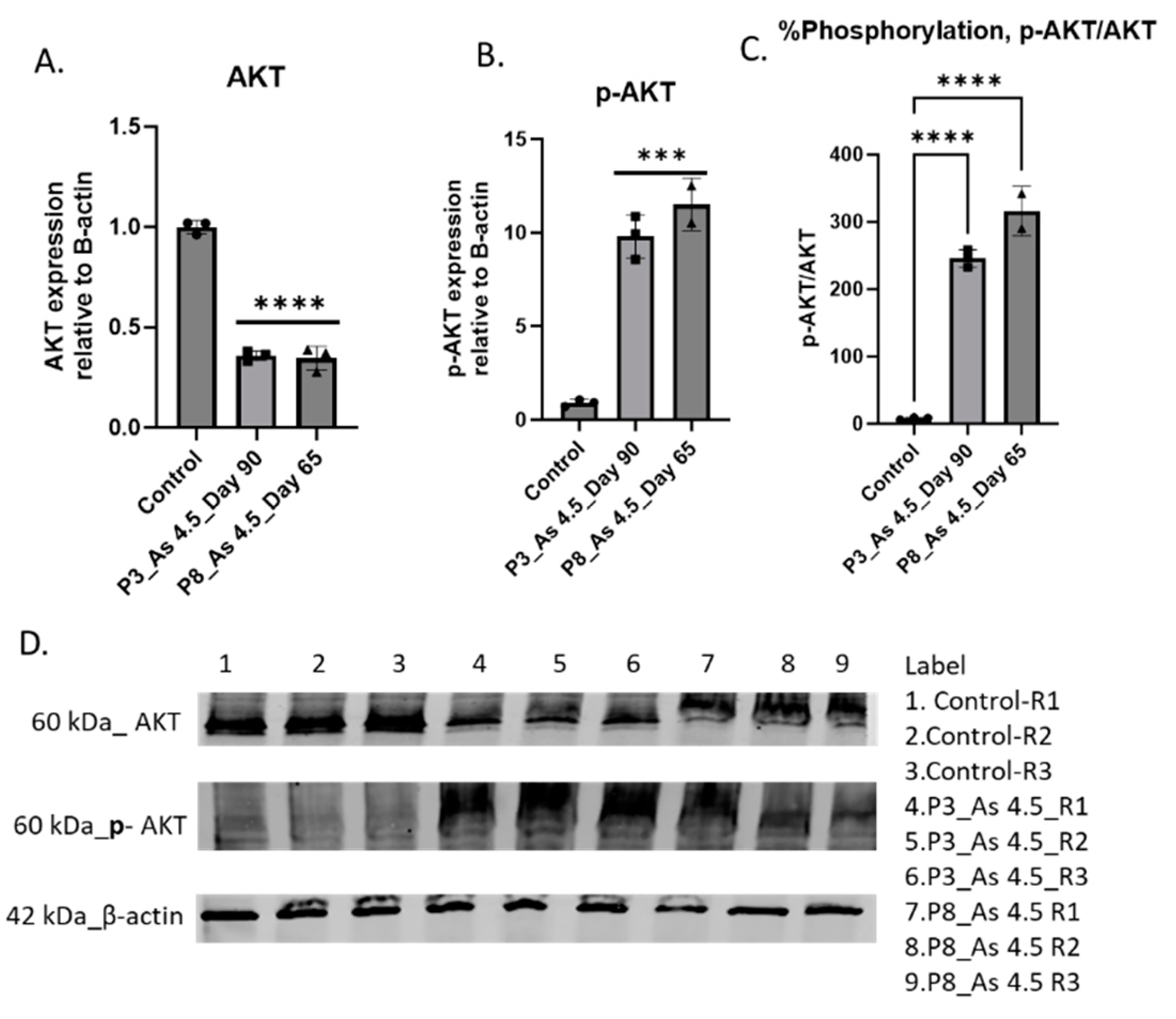

3.3. As (III) Exposure Increased the Expression of PI3K and MMP1

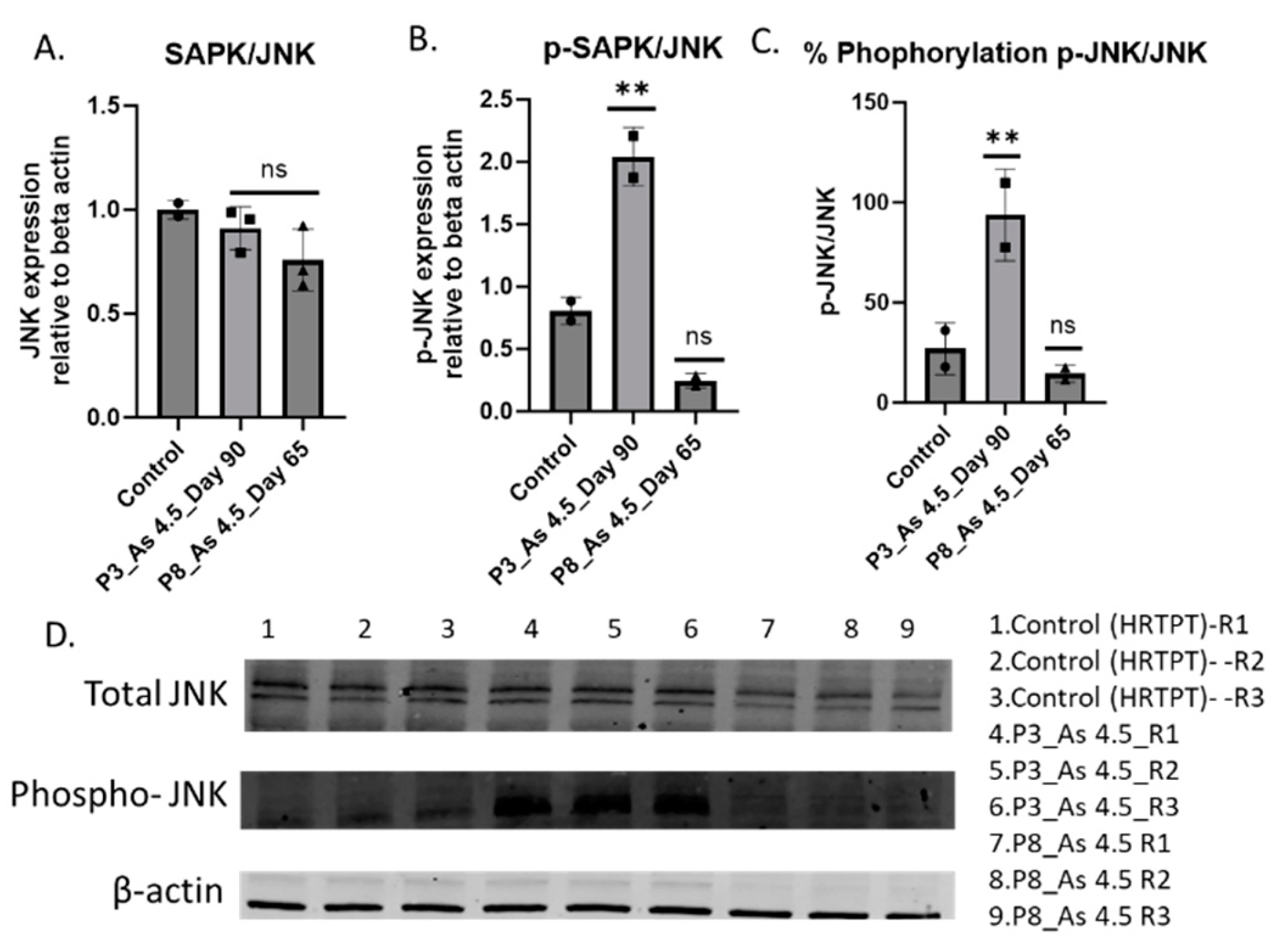

3.4. Determine How i-As (III) Increased the Expression of p-SAPK/JNK

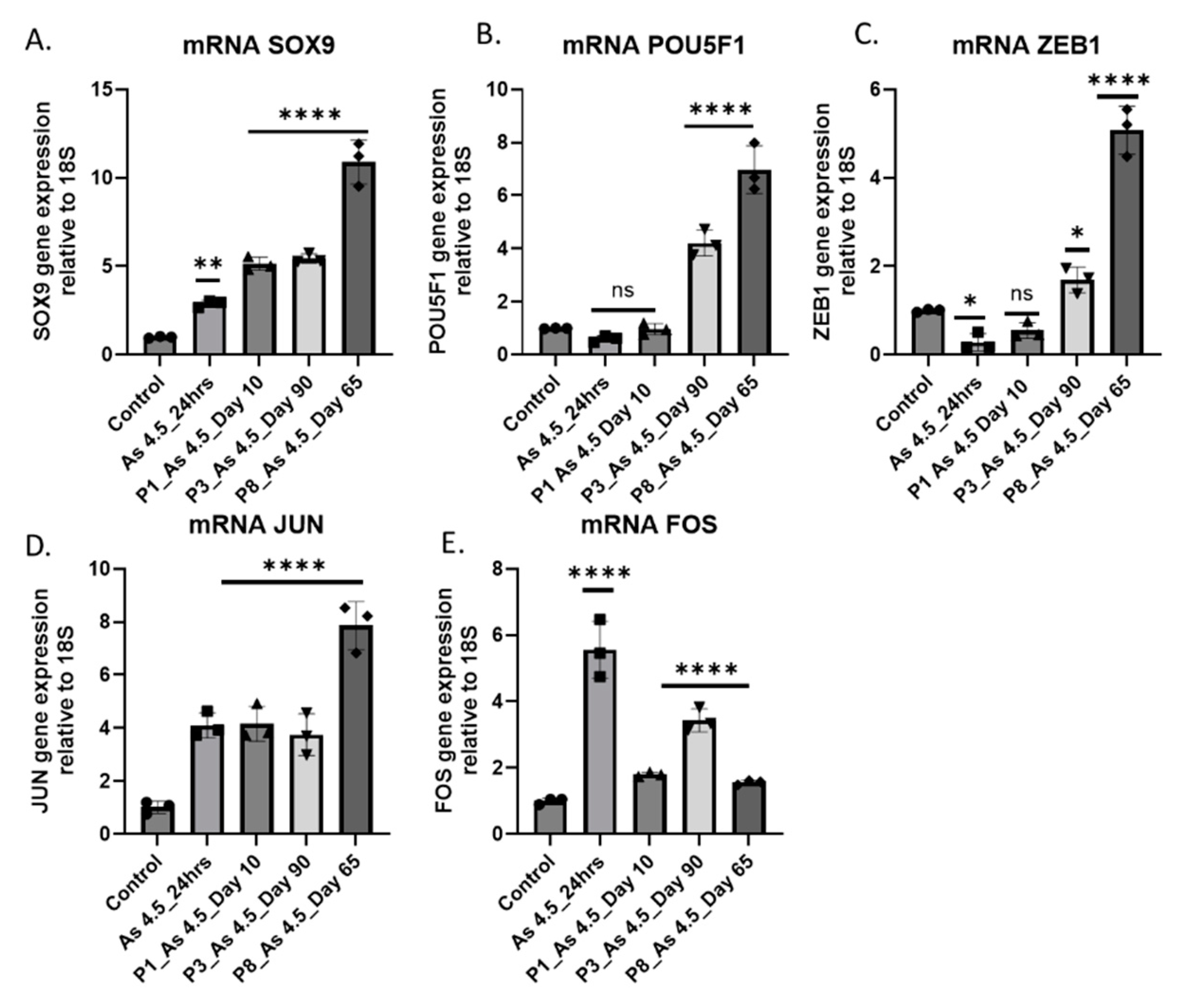

3.5. Expression of Transcription Factors (TFs) in Cancer Associated Fibroblast Activation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J. Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. Exp Suppl 2012, 101, 133-164. [CrossRef]

- Briffa, J.; Sinagra, E.; Blundell, R. Heavy metal pollution in the environment and their toxicological effects on humans. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04691. [CrossRef]

- Khairul, I.; Wang, Q.Q.; Jiang, Y.H.; Wang, C.; Naranmandura, H. Metabolism, toxicity and anticancer activities of arsenic compounds. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 23905-23926. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-Y.; Huang, N.-C.; Chang, Y.-T.; Sung, J.-M.; Shen, K.-H.; Tsai, C.-C.; Guo, H.-R. Associations between arsenic in drinking water and the progression of chronic kidney disease: A nationwide study in Taiwan. Journal of hazardous materials 2017, 321, 432-439. [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, D.K. An overview of arsenic mass-poisoning in Bangladesh and West Bengal, India. Availabe online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/70198882 (accessed on.

- Cohen, S.M.; Arnold, L.L.; Eldan, M.; Lewis, A.S.; Beck, B.D. Methylated arsenicals: the implications of metabolism and carcinogenicity studies in rodents to human risk assessment. Crit Rev Toxicol 2006, 36, 99-133. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.T.; Han, D.; Xu, X.; Sansom, G.; Roh, T. Relationship between low-level arsenic exposure in drinking water and kidney cancer risk in Texas. Environmental pollution (1987) 2024, 363, 125097. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.-S.; Song, K.-H.; Chung, J.-Y. Health effects of chronic arsenic exposure. Journal of preventive medicine and public health 2014, 47, 245-252. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.F.; Beck, B.D.; Chen, Y.; Lewis, A.S.; Thomas, D.J. Arsenic exposure and toxicology: a historical perspective. Toxicol Sci 2011, 123, 305-332. [CrossRef]

- Ayotte, J.D.; Medalie, L.; Qi, S.L.; Backer, L.C.; Nolan, B.T. Estimating the High-Arsenic Domestic-Well Population in the Conterminous United States. Environ Sci Technol 2017, 51, 12443-12454. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Availabe online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/arsenic (accessed on 2/12/2025).

- Arsenic in Drinking Water. Availabe online: https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/environment/water/docs/contaminants/arsenicfactsht.pdf (accessed on 2/12/2025).

- Farkhondeh, T.; Naseri, K.; Esform, A.; Aramjoo, H.; Naghizadeh, A. Drinking water heavy metal toxicity and chronic kidney diseases: a systematic review. Rev Environ Health 2021, 36, 359-366. [CrossRef]

- LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2012; NBK547852.

- Thakkar, S.; Chen, M.; Fang, H.; Liu, Z.; Roberts, R.; Tong, W. The Liver Toxicity Knowledge Base (LKTB) and drug-induced liver injury (DILI) classification for assessment of human liver injury. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 12, 31-38. [CrossRef]

- Vahter, M.; Concha, G. Role of metabolism in arsenic toxicity. Pharmacol Toxicol 2001, 89, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Curthoys, N.P.; Moe, O.W. Proximal tubule function and response to acidosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014, 9, 1627-1638. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.Y.; Huang, N.C.; Chang, Y.T.; Sung, J.M.; Shen, K.H.; Tsai, C.C.; Guo, H.R. Associations between arsenic in drinking water and the progression of chronic kidney disease: A nationwide study in Taiwan. J Hazard Mater 2017, 321, 432-439. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-Y.; Chang, Y.-T.; Cheng, H.-L.; Shen, K.-H.; Sung, J.-M.; Guo, H.-R. Associations between arsenic in drinking water and occurrence of end-stage renal disease with modifications by comorbidities: A nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. The Science of the total environment 2018, 626, 581-591. [CrossRef]

- Bongiovanni, G.A.; Pérez, R.D.; Mardirosian, M.; Pérez, C.A.; Marguí, E.; Queralt, I. Comprehensive analysis of renal arsenic accumulation using images based on X-ray fluorescence at the tissue, cellular, and subcellular levels. Applied radiation and isotopes 2019, 150, 95-102. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Hsueh, Y.M.; Lai, M.S.; Shyu, M.P.; Chen, S.Y.; Wu, M.M.; Kuo, T.L.; Tai, T.Y. Increased prevalence of hypertension and long-term arsenic exposure. Hypertension 1995, 25, 53-60.

- Saint-Jacques, N.; Parker, L.; Brown, P.; Dummer, T.J. Arsenic in drinking water and urinary tract cancers: a systematic review of 30 years of epidemiological evidence. Environmental health 2014, 13, 44-44. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.H.; Hopenhayn-Rich, C.; Bates, M.N.; Goeden, H.M.; Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Duggan, H.M.; Wood, R.; Kosnett, M.J.; Smith, M.T. Cancer risks from arsenic in drinking water. Environmental health perspectives 1992, 97, 259-267. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.G.; Cherry, N. Arsenic in drinking water and renal cancers in rural Bangladesh. Occupational and environmental medicine (London, England) 2013, 70, 768-773. [CrossRef]

- Pershagen, G. The carcinogenicity of arsenic [Pesticides, drinking water]. Environmental health perspectives 1981, 40, 93-100. [CrossRef]

- S, H.; Y, C.; H, G. Arsenic Exposure in Drinking Water and Occurrence of Chronic Kidney Disease: The Association and Effect Modifications by Comorbidities. Environmental epidemiology 2019, 3, 167. [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2024. American Cancer Society, 2024. Availabe online: (accessed on 16th Aug 2024).

- Andrianova, N.V.; Buyan, M.I.; Zorova, L.D.; Pevzner, I.B.; Popkov, V.A.; Babenko, V.A.; Silachev, D.N.; Plotnikov, E.Y.; Zorov, D.B. Kidney Cells Regeneration: Dedifferentiation of Tubular Epithelium, Resident Stem Cells and Possible Niches for Renal Progenitors. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20, 6326. [CrossRef]

- Metsuyanim, S.; Harari-Steinberg, O.; Buzhor, E.; Omer, D.; Pode-Shakked, N.; Ben-Hur, H.; Halperin, R.; Schneider, D.; Dekel, B. Expression of stem cell markers in the human fetal kidney. PLoS One 2009, 4, e6709. [CrossRef]

- Smeets, B.; Boor, P.; Dijkman, H.; Sharma, S.V.; Jirak, P.; Mooren, F.; Berger, K.; Bornemann, J.; Gelman, I.H.; Floege, J.; et al. Proximal tubular cells contain a phenotypically distinct, scattered cell population involved in tubular regeneration. J Pathol 2013, 229, 645-659. [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, M.; Darabi, S.; Roozbahany, N.A.; Abbaszadeh, H.A.; Moghadasali, R. Great potential of renal progenitor cells in kidney: From the development to clinic. Exp Cell Res 2024, 434, 113875. [CrossRef]

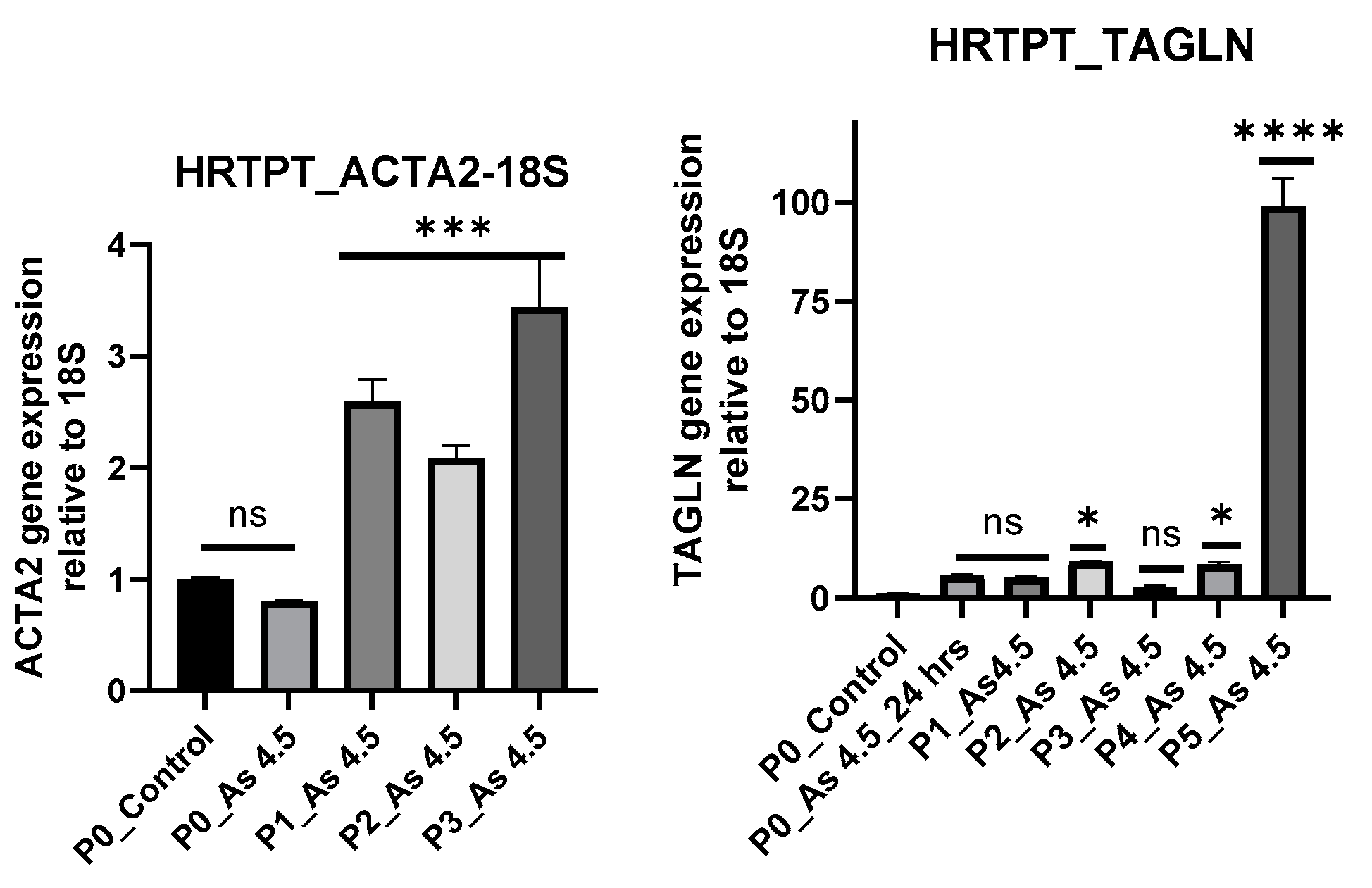

- Singhal, S.; Garrett, S.H.; Somji, S.; Schaefer, K.; Bansal, B.; Gill, J.S.; Singhal, S.K.; Sens, D.A. Arsenite Exposure to Human RPCs (HRTPT) Produces a Reversible Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (EMT): In-Vitro and In-Silico Study. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 5092. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Singhal, S.; Kalonick, M.; Guyer, R.; Volkert, A.; Somji, S.; Garrett, S.H.; Sens, D.A.; Singhal, S.K. Role of HRTPT in kidney proximal epithelial cell regeneration: Integrative differential expression and pathway analyses using microarray and scRNA-seq. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2021, 25, 10466-10479. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Somji, S.; Sens, D.A.; Slusser-Nore, A.; Patel, D.H.; Savage, E.; Garrett, S.H. Human renal tubular cells contain CD24/CD133 progenitor cell populations: Implications for tubular regeneration after toxicant induced damage using cadmium as a model. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2017, 331, 116-129. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Garrett, S.H.; Sens, D.A.; Zhou, X.D.; Guyer, R.; Somji, S. Characterization and determination of cadmium resistance of CD133+/CD24+ and CD133−/CD24+ cells isolated from the immortalized human proximal tubule cell line, RPTEC/TERT1. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2019, 375, 5-16. [CrossRef]

- Mehus, A.A.; Jones, M.; Trahan, M.; Kinnunen, K.; Berwald, K.; Lindner, B.; Al-Marsoummi, S.; Zhou, X.D.; Garrett, S.H.; Sens, D.A.; et al. Pevonedistat Inhibits SOX2 Expression and Sphere Formation but Also Drives the Induction of Terminal Differentiation Markers and Apoptosis within Arsenite-Transformed Urothelial Cells. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 9149. [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Zhou, X.D.; Sens, M.A.; Garrett, S.H.; Zheng, Y.; Dunlevy, J.R.; Sens, D.A.; Somji, S. Keratin 6 expression correlates to areas of squamous differentiation in multiple independent isolates of As+3-induced bladder cancer. Journal of applied toxicology 2010, 30, 416-430. [CrossRef]

- Papanastasiou, A.D.; Peroukidis, S.; Sirinian, C.; Arkoumani, E.; Chaniotis, D.; Zizi-Sermpetzoglou, A. CD44 Expression in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (ccRCC) Correlates with Tumor Grade and Patient Survival and Is Affected by Gene Methylation. Genes 2024, 15, 537. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, D.J.; Simon, M.C. Genetic and metabolic hallmarks of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2018, 1870, 23-31. [CrossRef]

- Sene, A.P.; Hunt, L.; McMahon, R.F.; Carroll, R.N. Renal carcinoma in patients undergoing nephrectomy: analysis of survival and prognostic factors. Br J Urol 1992, 70, 125-134. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Xu, W.H.; Ren, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.K.; Cao, D.L.; Shi, G.H.; Qu, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.L.; Ye, D.W. Prognostic value of epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 866-883. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ying, H.; Xu, J.; Yang, H.; Sun, K.; He, L.; Li, M.; Ji, Y.; Liang, T.; et al. Targeting MFAP5 in cancer-associated fibroblasts sensitizes pancreatic cancer to PD-L1-based immunochemotherapy via remodeling the matrix. Oncogene 2023, 42, 2061-2073. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Ge, J.; Ma, J.; Zheng, J. Carcinoembryonic antigen related cell adhesion molecule 6 promotes the proliferation and migration of renal cancer cells through the ERK/AKT signaling pathway. Transl Androl Urol 2019, 8, 457-466. [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wang, D.; Xiong, F.; Wang, Q.; Liu, W.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y. The emerging roles of CEACAM6 in human cancer (Review). Int J Oncol 2024, 64. [CrossRef]

- Zang, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Su, L.; Zhu, Z.; Gu, Q.; Liu, B.; Yan, M. CEACAM6 promotes gastric cancer invasion and metastasis by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. PLoS One 2014, 9, e112908. [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Wang, J.; Lei, Y.; Cong, C.; Tan, D.; Zhou, X. Research progress on the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in gynecological cancer (Review). Molecular medicine reports 2019, 19, 4529-4535. [CrossRef]

- Manning, B.D.; Cantley, L.C. AKT/PKB Signaling: Navigating Downstream. Cell 2007, 129, 1261-1274. [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.-Y.; Smit, D.J.; Jücker, M. The Role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metabolism. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 2652. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Bai, X.; Feng, X.; Ni, J.; Beretov, J.; Graham, P.; Li, Y. Inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway alleviates ovarian cancer chemoresistance through reversing epithelial-mesenchymal transition and decreasing cancer stem cell marker expression. BMC cancer 2019, 19, 618-618. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.L.; Cantley, L.C. PI3K pathway alterations in cancer: variations on a theme. Oncogene 2008, 27, 5497-5510. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.-H.; Liu, L.-Z. PI3K/PTEN signaling in tumorigenesis and angiogenesis. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Proteins and proteomics 2008, 1784, 150-158. [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Lu, Y.; Yao, Z.; Wang, P.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Q.; Sang, X.; Wang, K.; Cao, G. The role of JNK signaling pathway in organ fibrosis. Journal of advanced research 2024, 10.1016/j.jare.2024.09.029. [CrossRef]

- López-Camarillo, C.; Ramos-Payán, R.; Romero-Quintana, J.G.; Bermúdez, M.; Lizárraga-Verdugo, E.; Avendaño-Félix, M.; Aguilar-Medina, M.; Ruiz-Garcia, E.; Vergara, D. SOX9 Stem-Cell Factor: Clinical and Functional Relevance in Cancer. Journal of oncology 2019, 2019, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, M.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Hu, D.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; et al. SOX on tumors, a comfort or a constraint? Cell death discovery 2024, 10, 67-67. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).