Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

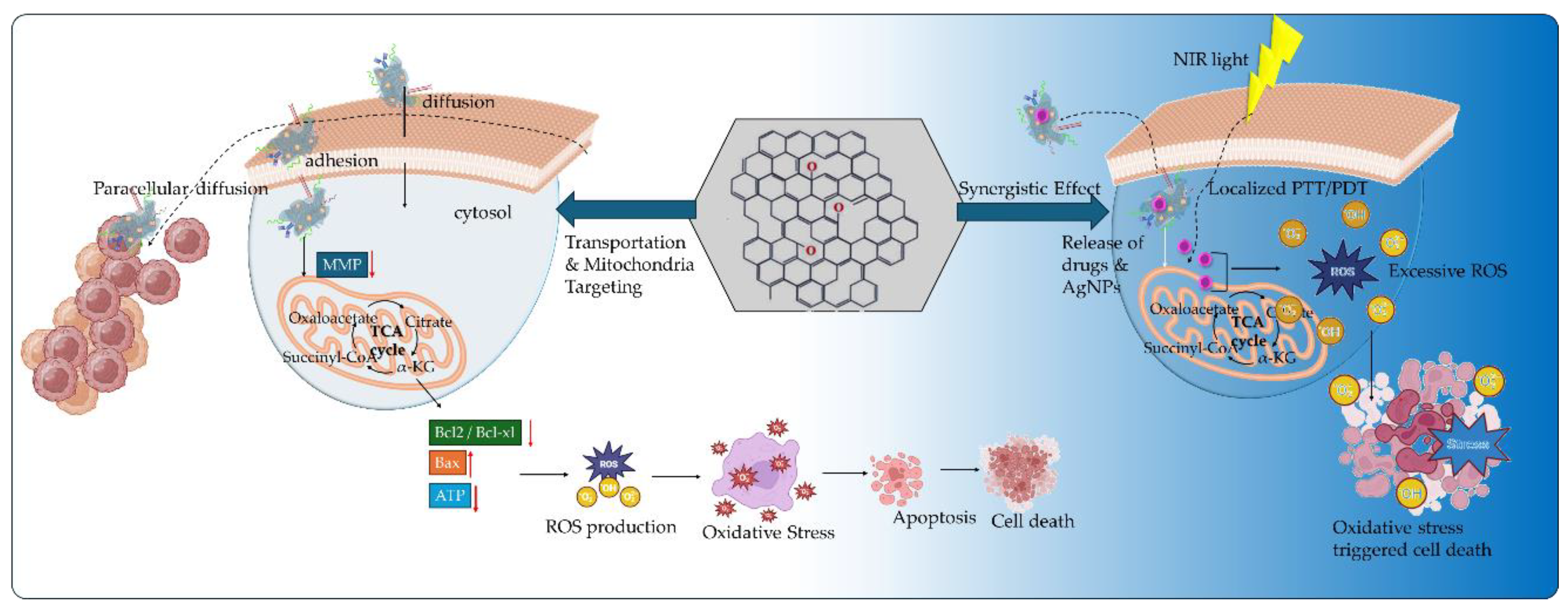

2. Graphene-Based Nanocomposites in Reprogramming of TME

2.1. Graphene and Graphene Quantum Dots

| Carrier Type | Agent | Characteristics | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| GQDs Carboxylated-GQDs |

- | increased membrane fluidity reduced formation of neurospheres in U87MG glioblastoma cancer cells and glioblastoma neurospheres |

[55] |

| Carboxylated-GQDs | DOX, TMZ | synergistic PTT on 3D spheroid model of glioblastoma, elevated intracellular ROS production, increased membrane permeability, elevated presence of tumor-associated antigens | [57] |

| nitrogen-doped GQD with HA and Fc | HA, Fc | CD44 cancer cell receptor targeting in HeLa cells, Fc facilitated a redox-based toxicity by the redox cycle of iron, oxidative stress targeting | [59] |

| nitrogen-doped GQD | TPP, ruthenium nitrosyl | mitochondria targeting, PTT, regulation of oxygen consumption and ATP synthesis, an inhibitory effect in the ETC, inhibited the in vivo tumor growth | [64] |

| GQDs | TPP | in vitro mitochondria monitoring | [68] |

| Hybrid GQDs - UCNP | TRITC | promoted increased in situ cytotoxic ROS formation, mitochondria dysfunction, decrease in mitochondria membrane potential, activation of caspase 3 apoptotic pathway | [69] |

| Graphene | GA | promoted the depletion of MMP, decreased the intracellular level of lipid droplets, induced DNA fragmentation | [72] |

| Pristine graphene | - | promote apoptotic mitochondria pathway signaling in murine RAW 264.7 macrophages, triggered increased ROS levels, activated Bcl-2 family pro-apoptotic proteins, activated MAPK and TGF-β signaling, activated caspace-3 related apoptotic pathway | [76] |

2.2. Graphene Oxide

| Carrier Type | Agent | Characteristics | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO-PEG | HY, DOΧ | Combined PDT and anticancer therapy, internalization via endocytosis, glutathione-triggered HY release, pH-triggered DOX release, HY-triggered generation of singlet oxygen in mitochondria, cytochrome c release into the cytosol, caspases activation | [77] |

| GO- DSPE-PEG2000 | TPP+, IR820 NIR Photosensitizer, CpG ODN |

combined PDT/PTT and immunostimulatory anticancer effect, mitochondrial targeting, increased ROS production, mitochondrial induced cell death, upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, INF-γ) | [83] |

| GO-ICG | TPPB | increased mitochondrial accumulation, synergistic PDT/PTT, elevated ROS (1O2, O2–) production, GO hyperthermia effect, inhibition of ATP synthesis | [86] |

| GO-PEG | integrin αvβ3 mAb, PPa | on/off phototoxicity switches, FRET mechanism, mitochondria accumulation, localized ROS formation, promoting cell apoptosis | [88] |

| GO-MitP | MTX | Increased mitochondria localization, promoting mitochondria dysfunction upon AFM, decrease in MMP, downregulation in ATP expression levels, cytochrome c release, activation of caspase 3 apoptotic pathway | [89] |

| GO- β-CD/Plys/PEG/MitP | TPM-Azo, TF | Increased mitochondria accumulation, stimulating mitochondrial aggregation, reducing ATP levels, disruption of cancer cells cycle, arrest at the G2 phase, decreased cell viability, increased cytochrome c expression into the cytosol | [92] |

| GO-GA | DOX | mitochondria targeting, selective pH-dependent DOX release, decreased the MMP, opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pores, increase in the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 proteins, activation of caspase-mediated apoptotic pathway | [94] |

| GO-GE11 | Ori | promoted mitochondrial dysfunction, decreased the MMP, induced cell cycle arrest increasing the G2/M phase, downregulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathways | [99] |

2.3. Reduced Graphene Oxide

| Carrier Type | Agent | Characteristics | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| rGO | - | stimulated autophagy and cell cycle arrest in cancer cells, promoted apoptosis signaling pathway, decreased the MMP, activated caspase-9 and caspase-3 cytosolic expression | [103] |

| rGO | Gamma irradiation | oxidative stress damage, elevated levels of ROS expression, damage of myocardial tissue, reduced expression levels of enzymes | [104] |

| rGO-MNPs | Coum, CMP | Combined chemophotodynamic effect, elevated ROS production, regulation of apoptotic cell death, cell shrinkage and nuclear fragmentation, increased expression of p53 and Bax proteins | [105] |

| rGO | MG-132 | increased apoptosis and necrosis of breast cancer cells, increasing ROS formation, caspase-8 and caspase-9 apoptotic pathways activation, reduced enzymatic antioxidants activity (SOD, GPx) | [106] |

| rGO-AgNPs | - | Decreased viability and cell growth, leakage of intracellular LDH, damage of cellular membrane integrity, ROS generation, increased MDA pro-oxidant levels, decreased antioxidant GSH production, activation of caspase-3 apoptotic death | [111] |

| rGO-AgNPs | Cis | Inhibition of viability and proliferation, increased Cis-induced ROS expression levels, increased oxidative stress, elevated MDA expression levels, loss of MMP, upregulation of apoptotic genes, downregulation of anti-apoptotic genes | [112] |

| rGO-Arg/Pro | - | increased cellular membranes adhesion, reduced cell proliferation, downregulation of VEGF expression, caspsase-3 activation, inhibition of FGF2, regulation of apoptosis | [115] |

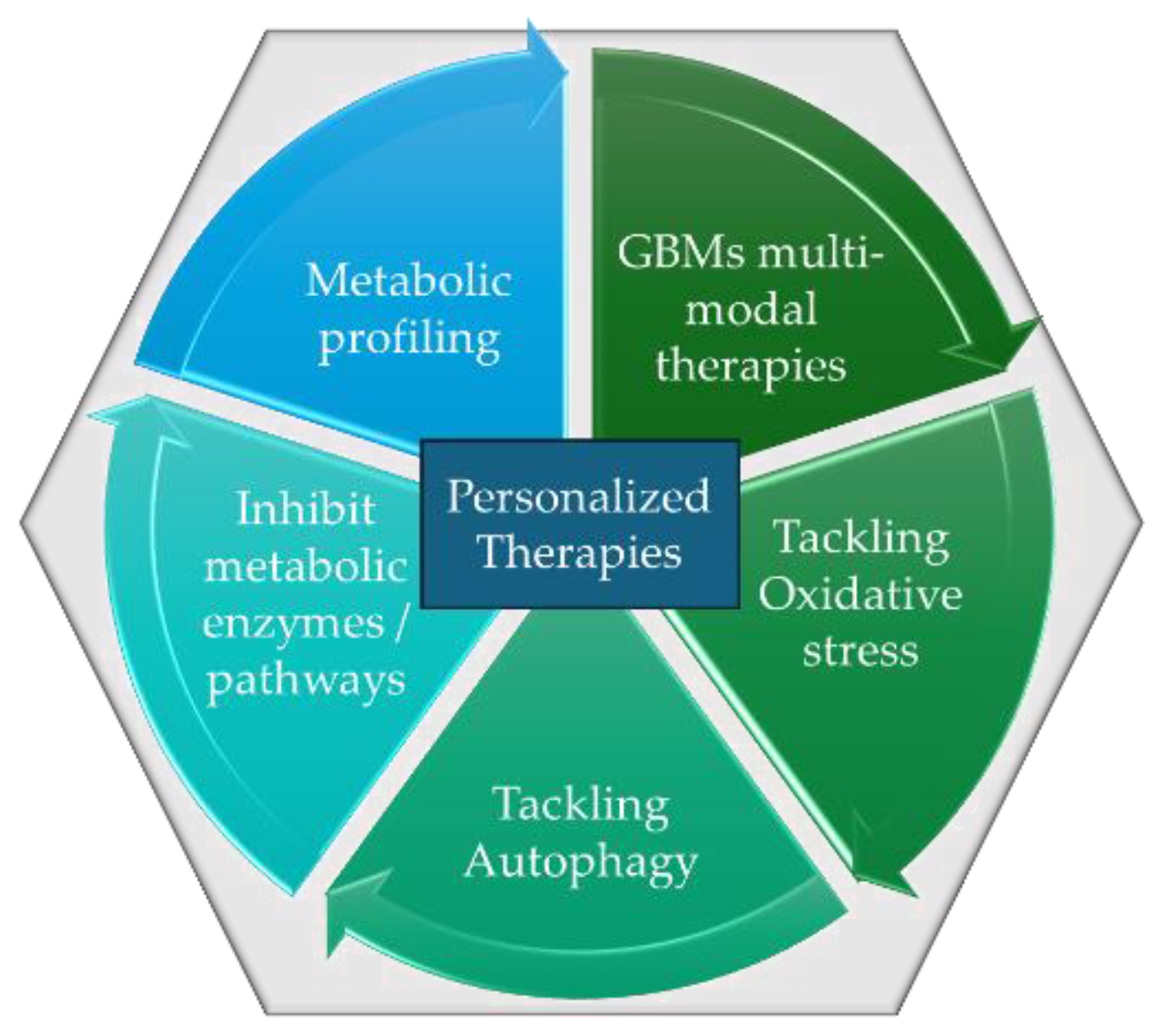

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Future Directions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alhazmi, H.A.; Ahsan, W.; Mangla, B.; Javed, S.; Hassan, M.Z.; et al. Graphene-based biosensors for disease theranostics: Development, applications, and recent advancements. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2022, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jampilek, J.; Kralova, K. Advances in Drug Delivery Nanosystems Using Graphene-Based Materials and Carbon Nanotubes. Materials 2021, 14, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, A.; Iravani, S.; Varma, R.S. Graphene and graphene oxide with anticancer applications: Challenges and future perspectives. Med. Comm. 2022, 3, e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoo, A.M.; Vemula, S.L.; Gupta, M.T.; Giram, M.V.; Kumar, S.A.; et al. Multifunctional graphene oxide nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer. J. Contr. Rel. 2022, 350, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Mohammadnejad, J.; Najafi-Taher, R.; Zadeh, Z.B.; Tanhaei, M.; et al. Multifunctional Carbon-Based Nanoparticles: Theranostic Applications in Cancer Therapy and Diagnosis. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 6, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Chakraborty, S.; Monikh, F.A.; Varsou, D.D.; Chetwynd, A.J.; et al. Functionalization of Graphene-Based Materials: Biological Behavior, Toxicology, and Safe-By-Design Aspects. Adv Biol (Weinh). 2021, 5, e2100637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadeel, B.; Busy, C.; Merino, S.; Vazquez, E.; Flahaut, E.; et al. Safety Assessment of Graphene-Based Materials: Focus on Human Health and the Environment. ACS Nano. 2018, 12, 10582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, A.; Papachristodoulou, M.; Voulgari, E.; Mouikis, A.; Zygouri, P.; et al. Paclitaxel-Loaded, Pegylated Carboxylic Graphene Oxide with High Colloidal Stability, Sustained, pH-Responsive Release and Strong Anticancer Effects on Lung Cancer A549 Cell Line. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattari, S.; Adeli, M.; Beyranvand, S.; Nemati, M. Functionalized Graphene Platforms for Anticancer Drug Delivery. I.J.Naanomed. 2021, 16, 5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, A.; Voulgari, E.; Diamanti, E.K.; Gournis, D.; Avgoustakis, K. Graphene oxide stabilized by PLA–PEG copolymers for the controlled delivery of paclitaxel. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 93, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, S.; Chen, Y.; Zareian, M.; Pandit, S.; Mijakovic, I. Cellular and subcellular interactions of graphene-based materials with cancerous and non-cancerous cells. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 189, 114467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, K.; Li, J. Application of graphene oxide in tumor targeting and tumor therapy. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2023, 34, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yue, H. Two-dimensional nanomaterials induced nano-bio interfacial effects and biomedical applications in cancer treatment. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, R.; Tang, Y.Q.; Miao, H. Metabolism in tumor microenvironment: Implications for cancer immunotherapy. MedComm 2020, 1, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avgoustakis, K.; Angelopoulou, A. Biomaterial-Based Responsive Nanomedicines for Targeting Solid Tumor Microenvironments. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmelman, A.C.; Sherman, M.H. The Role of stroma in Cancer Metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2024, 14, a041540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schworer, S.; Vardhana, S.A.; Thompson, C.B. Cancer metabolism drives a stromal regenerative response. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Escalona, R.; Leung, D.; Chan, E.; Kannourakis, G. Tumour microenvironment and metabolic plasticity in cancer and cancer stem cells: Perspectives on metabolic and immune regulatory signatures in chemoresistant ovarian cancer stem cells. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 53, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, E.N.; Rathmell, J.C. Metabolic Programming and Immune Suppression in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2023, 41, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ye, X.; Xiong, Z.; Ihsan, A.; Ares, I.; et al. Cancer Metabolism: The Role of ROS in DNA Damage and Induction of Apoptosis in Cancer Cells. Metabolites 2023, 13, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiliro, C.; Firestein, B.L. Mechanisms of Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer Cells Supporting Enhanced Growth and Proliferation. Cells 2021, 10, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Alesi, G.N.; Kang, S. Glutaminolysis as a target for cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2016, 35, 3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Zou, T.; Shen, X.; Nelson, P.J.; Li, J.; et al. Lipid metabolism in cancer progression and therapeutic strategies. MedComm, 2020, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, N.; Lupien, L.; Kuemmerle, N.B.; Kinlaw, W.B.; Swinnen, J.V.; et al. Lipogenesis and lipolysis: the pathways exploited by the cancer cells to acquire fatty acids. Prog Lipid Res. 2013, 52, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffuid, K.; Cao, Y. Decoding the Complexity of Immune–Cancer Cell Interactions: Empowering the Future of Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; DeBerardinis, R.J. Mechanisms and Implications of Metabolic Heterogeneity in Cancer. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Hua, G.; Hu, X. Lipid metabolism associated crosstalk: the bidirectional interaction between cancer cells and immune/stromal cells within the tumor microenvironment for prognostic insight. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Qiu, J.; O'Sullivan, D.; Buck, M.D.; Noguchi, T.; et al. Metabolic Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Is a Driver of Cancer Progression. Cell. 2015, 162, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Koh, J.; Song, S.G.; Yim, J.; Kim, M.; et al. High tumor hexokinase-2 expression promotes a pro-tumorigenic immune microenvironment by modulating CD8+/regulatory T-cell infiltration. BMC Cancer. 2022, 22, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Yin, Y.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X. Metabolic regulation of tumor-associated macrophage heterogeneity: insights into the tumor microenvironment and immunotherapeutic opportunities. Biomark Res, 2024, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Zheng, X.; Gao, H.; Jiang, A.; Yao, Y.; et al. Nanomedicines Targeting Metabolism in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 943906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Pombo, I.; Raposo, L.; Pedrosa, P.; Fernandes, A.R.; et al. Nanotheranostics Targeting the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol 2019, 7, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, M. Developing targeted therapies for neuroblastoma by dissecting the effects of metabolic reprogramming on tumor microenvironments and progression. Theranostics. 2024, 14, 3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Y; et al. Advances in targeting tumor microenvironment for immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1472772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.A.; Nisar, S.; Singh, M.; Ashraf, B.; Masoodi. Et al. Cytokine- and chemokine-induced inflammatory colorectal tumor microenvironment: Emerging avenue for targeted therapy. Cancer Commun. 2022, 42, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Guo, S.; Deng, J.; Shen, J.; Du, F.; et al. VEGF/VEGFR-Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: Targeting the Tumor Microenvironment. Int J Biol Sci. 2022, 18, 3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, R.; Perkins, G. Challenges in targeting cancer metabolism for cancer therapy. EMBO Rep. 2012, 13, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, B.A.; Marston Linehan, W.; Helman, L.J. Targeting Cancer Metabolism. Clin Cancer Res., 2012, 18, 5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadh, M.J.; Mustafa, M.A.; Qassem, L.Y.; Ghadir, G.K.; Alaraj, M.; et al. Targeting hypoxic and acidic tumor microenvironment by nanoparticles: A review. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol., 2024, 96, 105660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yuan, J.; Xu, K.; Li, S.; Liu, Y. Nanotechnology Reprogramming Metabolism for Enhanced Tumor Immunotherapy. ACS Nano. 2024, 18, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; An, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y. Nano-medicine therapy reprogramming metabolic network of tumour microenvironment: new opportunity for cancer therapies. J. Drug Target 2024, 32, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannazzo, D.; Espro, C.; Celesti, C.; Ferlazzo, A.; Neri, G. Smart Biosensors for Cancer Diagnosis Based on Graphene Quantum Dots. Cancers 2021, 13, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourmadadi, M.; Soleimani Dinani, H.; Saeidi Tabar, F.; Khassi, K.; Janfaza, S.; Tasnim, N.; Hoorfar, M. Properties and Applications of Graphene and Its Derivatives in Biosensors for Cancer Detection: A Comprehensive Review. Biosensors 2022, 12, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzdrowska, K.; Knap, N.; Gulczynski, J.; Kuban-Jankowska, A.; Struck-Lewicka, W.; et al. Chasing Graphene-Based Anticancer Drugs: Where are We Now on the Biomedical Graphene Roadmap? Int J Nanomedicine. 2024, 19, 3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabish, T.A.; Zhang, S.; Winyard, P.G. Developing the next generation of graphene-based platforms for cancer therapeutics: The potential role of reactive oxygen species. Redox Biology, 2018, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.; Mehnert, J.M.; Chan, C.S. Autophagy, Metabolism, and Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poillet-Perez, L.; White, E. Role of tumor and host autophagy in cancer metabolism. Genes Dev. 2019, 33, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shao, S.; Song, N.; Yang, B.; Liu, F.; et al. Integrated omics characterization reveals reduced cancer indicators and elevated inflammatory factors after thermal ablation in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Respir Res 2024, 25, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, R.D.; Powell, J.D. Metabolism of immune cells in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2020, 20, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, L.E.; Carnero, A. NAD+ metabolism, stemness, the immune response, and cancer. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Byun, J.-K.; Choi, Y.-K.; Park, K.-G. Targeting glutamine metabolism as a therapeutic strategy for cancer. Exp Mol Med 2023, 55, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z. Current knowledge and potential intervention of hexosamine biosynthesis pathway in lung cancer. World J Surg Onc 2023, 21, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Yu, W.; Liu, J.; Tang, D.; Yang, L.; et al. Oxidative cell death in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arfin, S.; Jha, N.K.; Jha, S.K.; Kesari, K.K.; Ruokolainen, J.; et al. Oxidative Stress in Cancer Cell Metabolism. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perini, G.; Palmieri, V.; Ciasca, G.; Primiano, A.; Gervasoni, J.; et al. Functionalized Graphene Quantum Dots Modulate Malignancy of Glioblastoma Multiforme by Downregulating Neurospheres Formation. C — J. Carbon Research 2021, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlasa, W.; Zendran, I.; Zalesinska, A.; Tarek, M.; Kulbacka, J. Lipid composition of the cancer cell membrane. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2020, 52, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perini, G.; Palmieri, V.; Friggeri, G.; et al. Carboxylated graphene quantum dots-mediated photothermal therapy enhances drug-membrane permeability, ROS production, and the immune system recruitment on 3D glioblastoma models. Cancer Nano 2023, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Sandoval, J.A.; Gomez-Garcia, M.C.; de los Santos-Jimenez, J.; Mates, J.M.; Alonso, F.J.; et al. Antioxidant responses related to temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma. Neurocchem. Intern. 2021, 149, 105136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.; Hasan, M.T.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, R.; Truly, T.; Lee, B.H.; et al. Graphene quantum dot formulation for cancer imaging and redox-based drug delivery. Nanomed.: Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2021, 37, 102408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.; Hasan, M.T.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, R.; Akkaraju, G.; Naumov, A.V. Doped Graphene Quantum Dots for Intracellular Multicolor Imaging and Cancer Detection. ACS Biomater. Sci. Engineer. 2019, 5, 4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, V.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, D.; Joshi, R.K.; Nemiwal, M. Anticancer potential of ferrocene-containing derivatives: Current and future prospective. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1319, 139589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Fan, X.; Xu, X.; et al. How does ferrocene correlate with ferroptosis? Multiple approaches to explore ferrocene-appended GPX4 inhibitors as anticancer agents. Chem Sci. 2024, 15, 10477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaron, C.; Gabano, E.; Zanellato, I.; Gaiaschi, L.; Casali, C.; et al. Effects of Ferrocene and Ferrocenium on MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells and Interconnection with Regulated Cell Death Pathways. Molecules 2023, 28, 6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Xiang, H.-J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.-L.; An, L.; et al. Ruthenium nitrosyl functionalized graphene quantum dots as an efficient nanoplatform for NIR-light-controlled and mitochondria-targeted delivery of nitric oxide combined with photothermal therapy. Chem. Commun., 2017, 53, 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poderoso, J.J.; Helfenberger, K.; Poderoso, C. The effect of nitric oxide on mitochondrial respiration. Nitric Oxide. 2019, 88, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tengan, C.H.; Moraes, C.T. NO control of mitochondrial function in normal and transformed cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2018, 1858, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Myers, C.R.; Wang, Y.; You, M. Mitochondria as a Novel Target for Cancer Chemoprevention: Emergence of Mitochondrial-targeting Agents. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2021, 14, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Nie, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liao, X.; et al. Facile and large-scale synthesis of graphene quantum dots for selective targeting and imaging of cell nucleus and mitochondria. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2019, 103, 109824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wen, L.; Huang, R.; Wang, H.; Hu, X.; et al. Mitochondrial specific photodynamic therapy by rare-earth nanoparticles mediated near-infrared graphene quantum dots. Biomater. 2018, 153, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Yu, X.; Lu, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, L.; et al. Quantitative chemical proteomics reveals that phenethyl isothiocyanate covalently targets BID to promote apoptosis. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zhang, Y. Mitochondria are the primary target in isothiocyanate-induced apoptosis in human bladder cancer cells Mol. Cancer Ther 2005, 4, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, L.M.; Mahmood, M.; Pyrek, S.J.; Fahmi, T.; Yang, X.; et al. Single-walled carbon nanotube and graphene nanodelivery of gambogic acid increases its cytotoxicity in breast and pancreatic cancer cells. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2014, 34, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Sun, Q.; Chen, S.; Ma, D.; Qi, Y.; et al. pH-responsive hydrogel with gambogic acid and calcium nanowires for promoting mitochondrial apoptosis in osteosarcoma. J. Control. Real. 2025, 377, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.J.; Lee, D.M.; Kim, I.Y.; Lee, D.; Choi, M.-K.; et al. Gambogic acid triggers vacuolization-associated cell death in cancer cells via disruption of thiol proteostasis. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, E.; Jaggi, M.; Chauhan, S.C.; Yallapu, M.M. Gambogic acid: A shining natural compound to nanomedicine for cancer therapeutics. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020, 1874, 188381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Wei, T.; Le Guyader, L.; et al. The triggering of apoptosis in macrophages by pristine graphene through the MAPK and TGF-beta signaling pathways. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.; Zhang, C.; Ma, T.; Zhang, C.; Luo, J.; et al. Hypericin-functionalized graphene oxide for enhanced mitochondria-targeting and synergistic anticancer effect. Acta Biomater. 2018, 77, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, N.; Collignon, T.E.; Tewari, D.; Bishayee, A. Hypericin and its anticancer effects: From mechanism of action to potential therapeutic application. Phytomed. 2022, 105, 154356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenkavska, L.; Blascakova, L.; Jurasekova, Z.; Macajova, M.; Bolcik, B.; et al. Benefits of hypericin transport and delivery by low- and high-density lipoproteins to cancer cells: From in vitro to ex ovo. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2019, 25, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkova, V.; Vargova, J.; Babincak, M.; Jendzelovsky, R.; Zdrahal, Z.; et al. New findings on the action of hypericin in hypoxic cancer cells with a focus on the modulation of side population cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miccoli, L.; Beurdeley-Thomas, A.; De Pinieux, G.; Sureau, S.; Oudard, S.; et al. Light-induced Photoactivation of Hypericin Affects the Energy Metabolism of Human Glioma Cells by Inhibiting Hexokinase Bound to Mitochondria. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 5777. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Theodossiou, T.A.; Hothersall, J.S.; De Witte, P.A.; Pantos, A.; Agostinis, P. The Multifaceted Photocytotoxic Profile of Hypericin. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2009, 6, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, L.; Tian, Y.; Guan, X.; Liu, Q.; et al. “Triple-Punch” Anticancer Strategy Mediated by Near-Infrared Photosensitizer/CpG Oligonucleotides Dual-Dressed and Mitochondria-Targeted Nanographene. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielonka, J.; Joseph, J.; Sikora, A.; Hardy, M.; Ouari, O.; et al. Mitochondria-Targeted Triphenylphosphonium-Based Compounds: Syntheses, Mechanisms of Action, and Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications. Chem Rev. 2017, 117, 10043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanagata, N. Structure-dependent immunostimulatory effect of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides and their delivery system. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012, 7, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.-N.; Yu, Q.-P.; Wang, D.; Liu, J.-L.; Yang, Q.-J.; et al. Mitochondria-targeting graphene oxide nanocomposites for fluorescence imaging-guided synergistic phototherapy of drug-resistant osteosarcoma. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, X.; Tse, B.W.-C.; Yang, H.; Thorling, C.A.; et al. Indocyanine green-incorporating nanoparticles for cancer theranostics. Theranostics. 2018, 8, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Q.; Xing, D. A graphene oxide based smart drug delivery system for tumor mitochondria-targeting photodynamic therapy. Nanoscale, 2016, 8, 3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, N.; Li, M.; Yu, Q. Mitochondrion targeting peptide-modified magnetic graphene oxide delivering mitoxantrone for impairment of tumor mitochondrial functions. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evison, B.J.; Sleebs, B.E.; Watson, K.G.; Phillips, D.R.; Cutts, S.M. Mitoxantrone, More than Just Another Topoisomerase II Poison. Med. Res. Rev. 2015, 36, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-W.; Choi, K.-C. Effects of anticancer drugs on the cardiac mitochondrial toxicity and their underlying mechanisms for novel cardiac protective strategies. Life Sci. 2021, 277, 119607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Liu, Y. Two-dimensional supramolecular assemblies based on β-cyclodextrin-grafted graphene oxide for mitochondrial dysfunction and photothermal therapy. Chem. Commun., 2019, 55, 12200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verwilst, P.; Han, J.; Lee, J.; Mun, S.; Kang, H.-G.; et al. Reconsidering azobenzene as a component of small-molecule hypoxia-mediated cancer drugs: A theranostic case study. Biomater. 2017, 115, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Geng, Y.; Han, C.; et al. Glycyrrhetinic Acid Functionalized Graphene Oxide for Mitochondria Targeting and Cancer Treatment In Vivo. Small. 2017, 14, 1703306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Li, L.; Peng, Q.; Gan, C.; Gao, L.; et al. Glycyrrhetinic acid restricts mitochondrial energy metabolism by targeting SHMT2. iScience 2022, 25, 104349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Ko, H.-S.; Sohn, E.J.; Kim, B.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Inhibition of protein kinase C α/βII and activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase mediate glycyrrhetinic acid induced apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer NCI-H460 cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 4, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Q.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; et al. Glycyrrhetinic acid inhibits non-small cell lung cancer via promotion of Prdx6- and caspase-3-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 173, 116304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, C.; Salvi, M.; Palermo, M.; Sinigaglia, G.; Armanini, D.; et al. On the mechanism of mitochondrial permeability transition induction by glycyrrhetinic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta – Bioenerg. 2004, 1658, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.-H.; Pi, J.; Jin, H.; Cai, J.-Y. Functional graphene oxide as cancer-targeted drug delivery system toselectively induce oesophageal cancer cell apoptosis. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Joshi, H.; Kandari, D.; Aggarwal, D.; Chauhan, R.; et al. Oridonin: A natural terpenoid having the potential to modulate apoptosis and survival signaling in cancer. Phytomed. Plus. 2025, 5, 100721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.; Tripathy, S.; Patra, C.R. (2022). Graphene Based Nanomaterials for ROS-Mediated Cancer Therapeutics. In: Chakraborti, S. (eds) Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Therapeutic Aspects. Springer, Singapore. pp 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Dash, B.S.; Jose, G.; Lu, Y.-J.; Chen, J.-P. Functionalized Reduced Graphene Oxide as a Versatile Tool for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kretowski, R.; Cechowska-Pasko, M. The Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) Induces Apoptosis, Autophagy and Cell Cycle Arrest in Breast Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, H.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Wu, G.-D.; Wang, L. Graphene Oxide and Reduced Graphene Oxide Exhibit Cardiotoxicity Through the Regulation of Lipid Peroxidation, Oxidative Stress, and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 616888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinothini, K.; Rajendran, N.K.; Rajan, M.; Ramu, A.; Marraiki, N.; et al. A magnetic nanoparticle functionalized reduced graphene oxide-based drug carrier system for a chemo-photodynamic cancer therapy. New J. Chem., 2020, 44, 5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretowski, R.; Szynaka, B.; Jablonska-Trypuc, A.; Kiełtyka-Dadasiewicz, A.; Cechowska-Pasko, M. The Synergistic Effect of Reduced Graphene Oxide and Proteasome Inhibitor in the Induction of Apoptosis through Oxidative Stress in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarjanyi, O.; Haerer, J.; Vecsernyes, M.; Berta, G.; Stayer-Harci, A. et a. Prolonged treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 induces apoptosis in PC12 rat pheochromocytoma cells. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanotto-Filho, A.; Braganhol, E.; Battastini, A.M.O. Moreire, J.C.F. Proteasome inhibitor MG132 induces selective apoptosis in glioblastoma cells through inhibition of PI3K/Akt and NFkappaB pathways, mitochondrial dysfunction, and activation of p38-JNK1/2 signaling. Invest New Drugs 2012, 30, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavinkumar, T.; Varunkumar, K.; Ravikumar, V.; Manivannan, S. Anticancer activity of graphene oxide-reduced graphene oxide-silver nanoparticle composites. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 505, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.; Zhang, J.; Gu, Z.; Chen, Y. Nanocatalysts-augmented Fenton chemical reaction for nanocatalytic tumor therapy. Biomaterials. 2019, 211, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, S.; Han, J.W.; Park, J.H.; Kim, E.; Choi, Y.; et al. Reduced graphene oxide–silver nanoparticle nanocomposite: a potential anticancer nanotherapy. I.J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.-G.; Gurunathan, S. Combination of graphene oxide–silver nanoparticle nanocomposites and cisplatin enhances apoptosis and autophagy in human cervical cancer cells. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017, 12, 6537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Tian, Y.; Gu, M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Autophagy-driven regulation of cisplatin response in human cancers: Exploring molecular and cell death dynamics. Cancer Let. 2024, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coreas, R.; Castillo, C.; Li, Z.; Yan, D.; Gao, Z.; et al. Biological impacts of reduced graphene oxide affected by protein corona formation. Chem Res Toxicol. 2022, 35, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawosz, E.; Jaworski, S.; Kutwin, M.; Vadalasetty, K.P.; Grodzik, M.; Wierzbicki, M.; Kurantowicz, N.; Strojny, B.; Hotowy, A.; Lipińska, L.; et al. Graphene Functionalized with Arginine Decreases the Development of Glioblastoma Multiforme Tumor in a Gene-Dependent Manner. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 25214–25233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Borchert, G.L.; Donald, S.; Diwan, B.; Anver, M.; et al. Proline oxidase functions as a mitochondrial tumor suppressor in human cancers. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshet, R.; Erez, A. Arginine and the metabolic regulation of nitric oxide synthesis in cancer. Dis. Model Mech. 2018, 11, dmm033332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajipour Keyvani, A.; Mohammadnejad, P.; Pazoki-Toroudi, H.; Perez Gilabert, I.; Chu, T.; et al. Advancements in Cancer Treatment: Harnessing the Synergistic Potential of Graphene-Based Nanomaterials in Combination Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 2, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasool, M.; Malik, A.; Waquar, S.; Arooj, M.; Zahid, S.; et al. New challenges in the use of nanomedicine in cancer therapy. Bioengineered. 2022, 13, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.; Ghorbani, S.H.; Mahdavian, L.; Aghamohammadi, M. Graphene-based hybrid composites for cancer diagnostic and therapy. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddu, A.; Obireddy, S.R.; Zhang, D.; Krishna Rao, K.S.V.; Lai, W.-F. ROS-generating, pH-responsive and highly tunable reduced graphene oxide-embedded microbeads showing intrinsic anticancer properties and multi-drug co-delivery capacity for combination cancer therapy. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakpour, E.; Salehi, S.; Naghib, S.M.; Ghorbanzadeh, S.; Zhang, W. Graphene-based nanomaterials for stimuli-sensitive controlled delivery of therapeutic molecules. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1129768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, K.N.; Shemchuk, O.S.; Ageev, S.V.; Andoskin, P.A.; Iurev, G.O.; et al. Development of Graphene-Based Materials with the Targeted Action for Cancer Theranostics. Biochemistry Moscow. 2024, 89, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Bytesnikova, Z.; Ashrafi, A.M.; Richtera, L.; et al. 2D graphene-based advanced nanoarchitectonics for electrochemical biosensors: Applications in cancer biomarker detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 250, 116050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannazzo, D.; Espro, C.; Celesti, C.; Ferlazzo, A.; Neri, G. Smart Biosensors for Cancer Diagnosis Based on Graphene Quantum Dots. Cancers 2021, 13, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, M.S.; Sangrizeh, F.H.; Jahani, N.; Abedin, M.S.; Chaleshgari, S.; et al. Graphene oxide nanoarchitectures in cancer therapy: Drug and gene delivery, phototherapy, immunotherapy, and vaccine development. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 117027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fucikova, J.; Keep, O.; Kasikova, L.; Petroni, G.; Yamazaki, T.; et al. Detection of immunogenic cell death and its relevance for cancer therapy. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.A; Ramli, M.M; Osman, N.H.; Mohamed, R. Stimulation of Innate and Adaptive Immune Cells with Graphene Oxide and Reduced Graphene Oxide Affect Cancer Progression. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2021, 69, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Hong, H.; Lee, Y.; Park, K.S.; Sun, M.; et al. Efficient Lymph Node-Targeted Delivery of Personalized Cancer Vaccines with Reactive Oxygen Species-Inducing Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanosheets. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 10–13268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Wei, W.; Gu, Z.; Ni, D.; Luo, N.; et al. Exploration of graphene oxide as an intelligent platform for cancer vaccines. Nanoscale, 2015, 7, 19949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; et al. Several lines of antioxidant defense against oxidative stress: antioxidant enzymes, nanomaterials with multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, and low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Arch Toxicol 2024, 98, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristic, B.; Harhaji-Trajkovic, L.; Bosnjak, M.; Dakic, I.; Mijatovic, S.; et al. Modulation of Cancer Cell Autophagic Responses by Graphene-Based Nanomaterials: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Cancers 2021, 13, 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandbhor, P.; Palkar, P.; Bhat, S.; John, G.; Goda, J.S. Nanomedicine as a multimodal therapeutic paradigm against cancer: on the way forward in advancing precision therapy. Nanoscale, 2024, 16, 6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabish, T.A.; Narayan, R.J. Mitochondria-targeted graphene for advanced cancer therapeutics. Acta Biomaterial 2021, 129, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).