Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Theoretical Background

1.1. Mechanical Properties of Masonry Structures

1.2. Quality Control

| fbk | fa | fgk | fpk/fbk | fpk*/fbk | fpk | fpk* |

| (MPa) | (MPa) | |||||

| 10,0 | 8,0 | 20,0 | 0,60 | 1,60 | 6,0 | 9,6 |

| 14,0 | 12,0 | 25,0 | 0,60 | 1,60 | 8,4 | 13,4 |

| 18,0 | 15,0 | 30, | 0,60 | 1,60 | 10,8 | 17,3 |

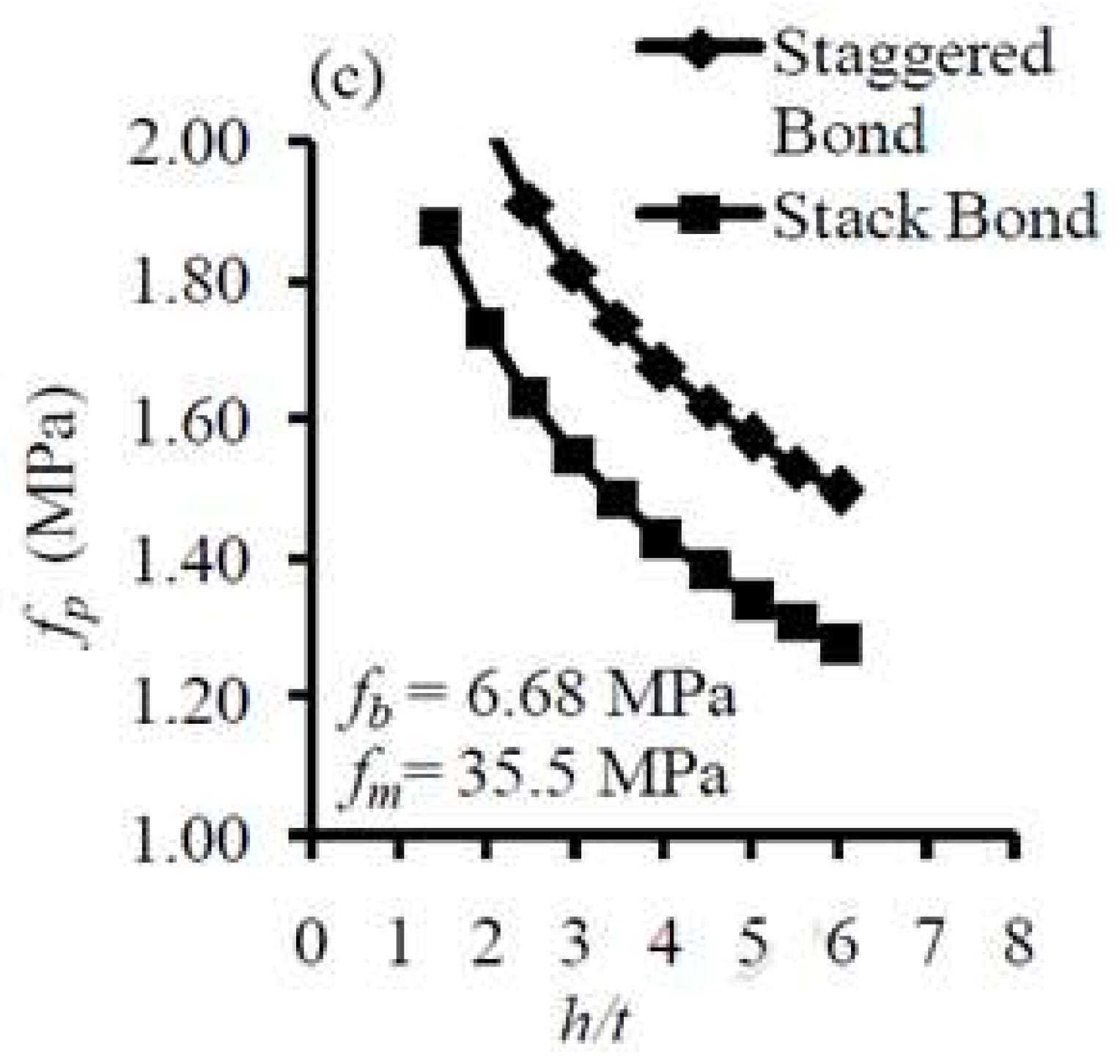

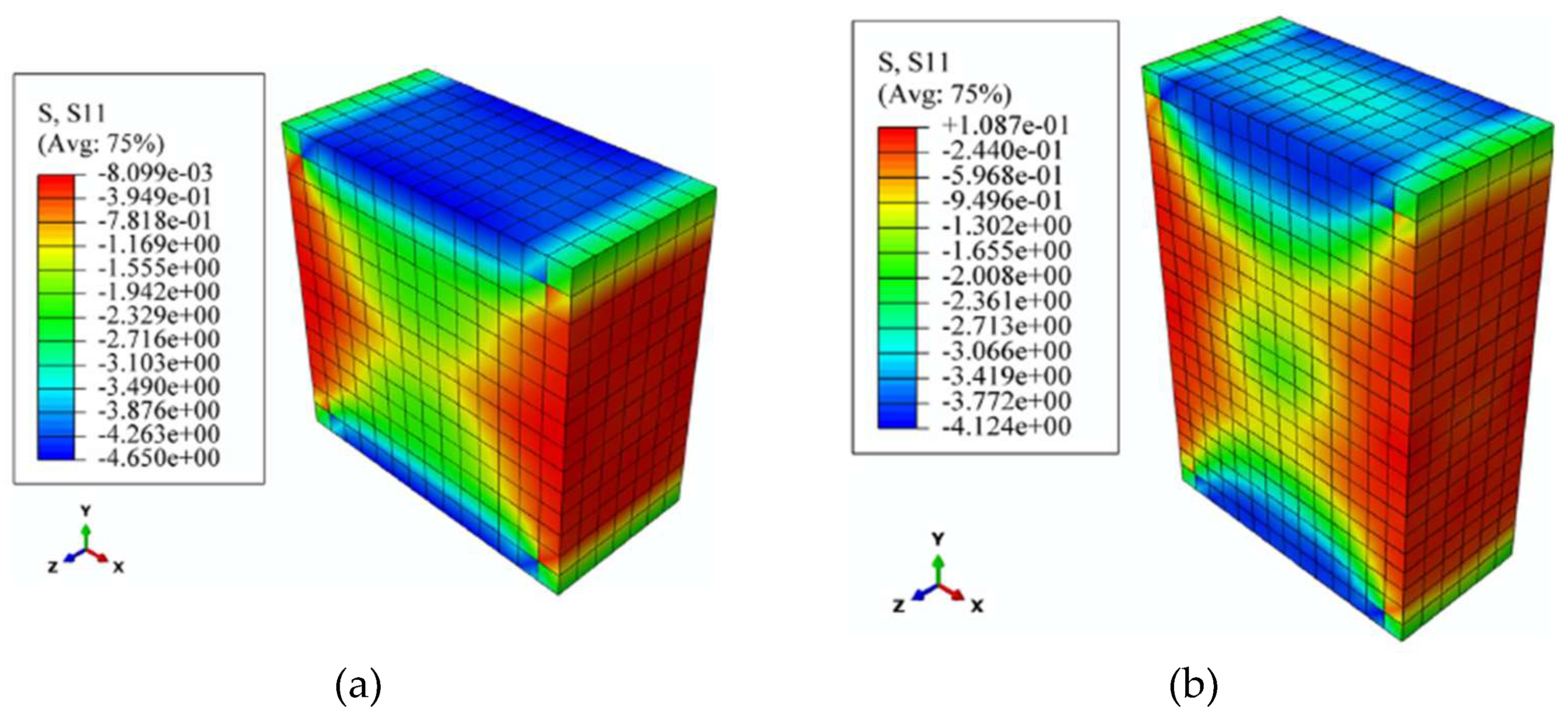

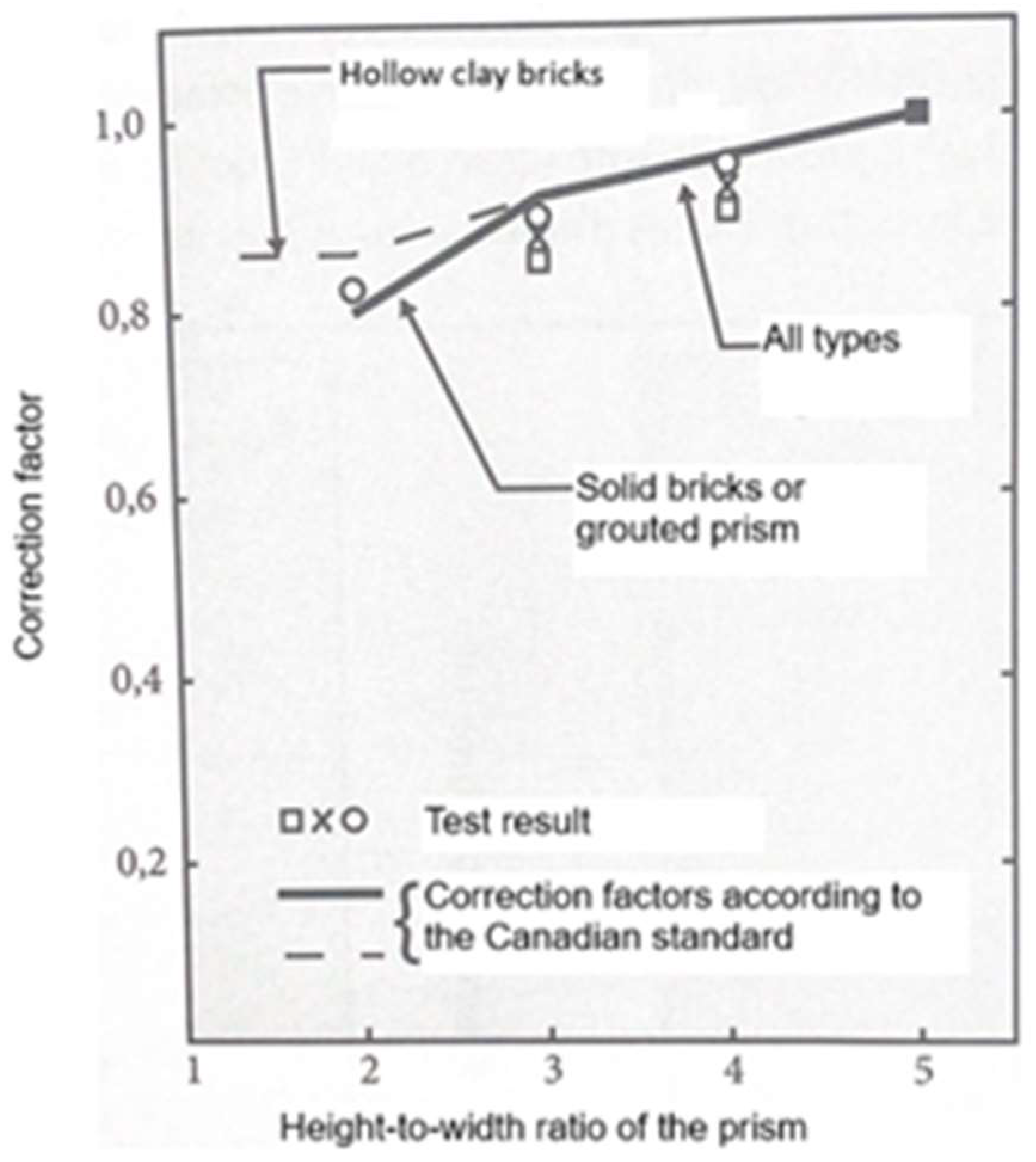

1.3. Variables That Influence the Compressive Strength of Masonry Elements

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

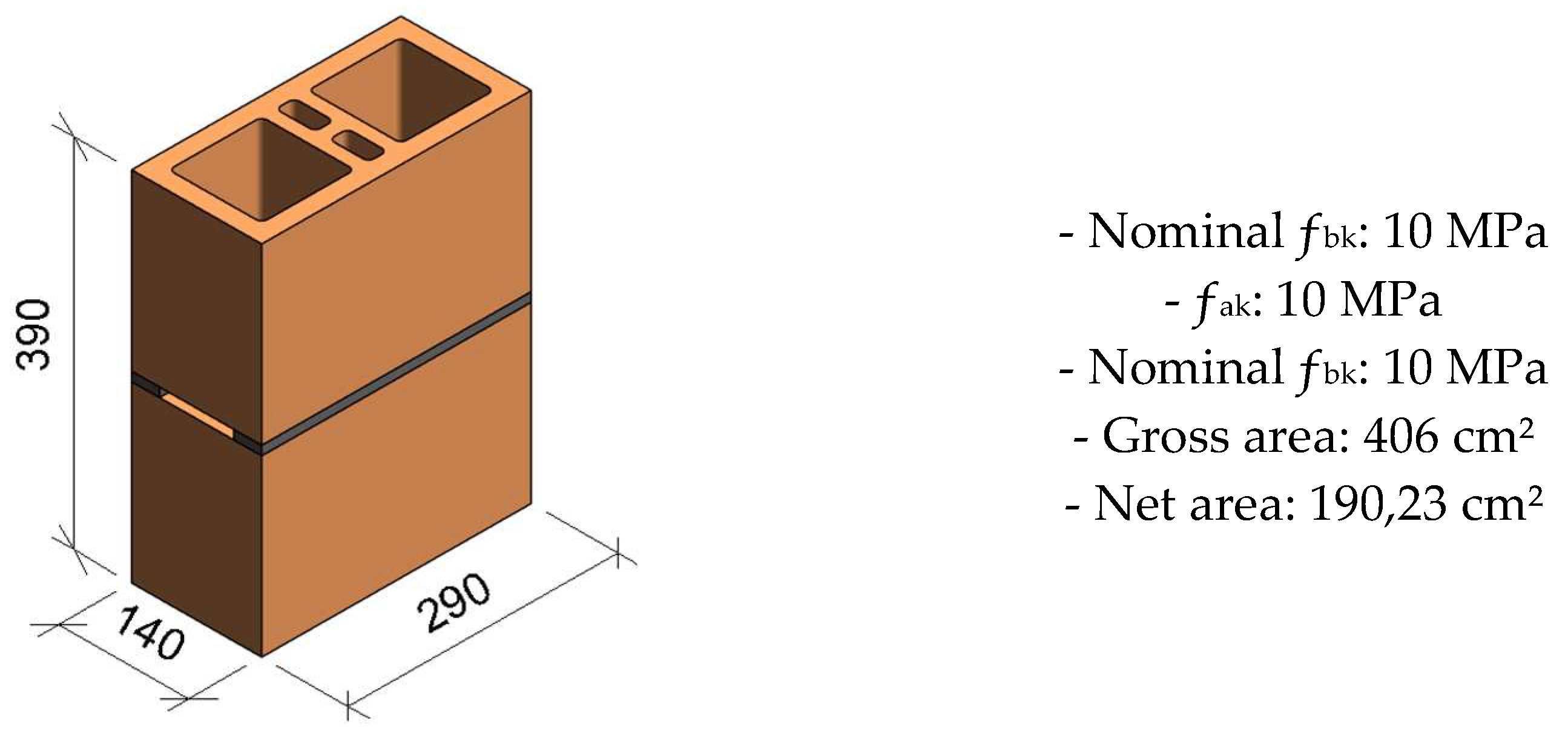

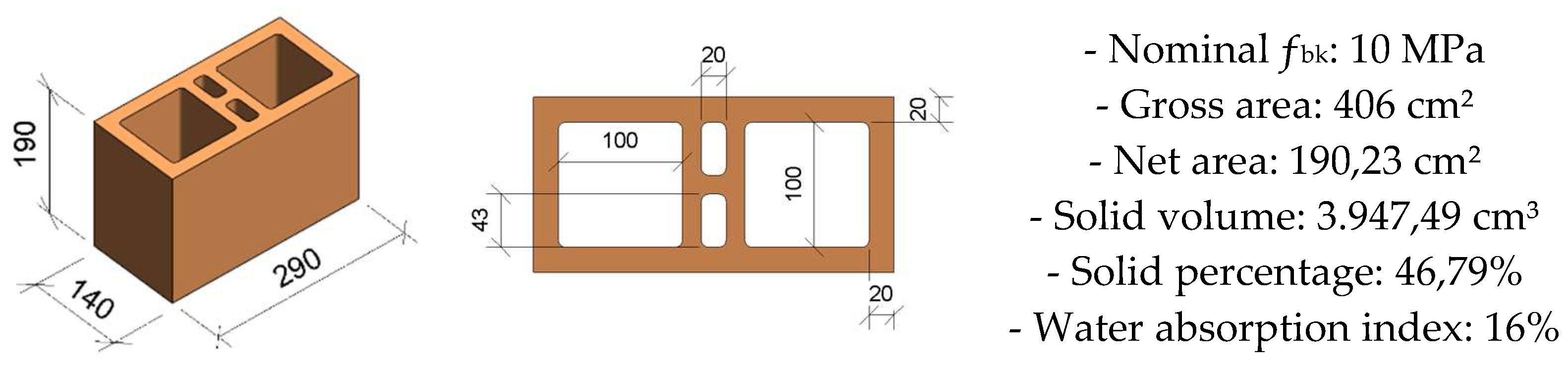

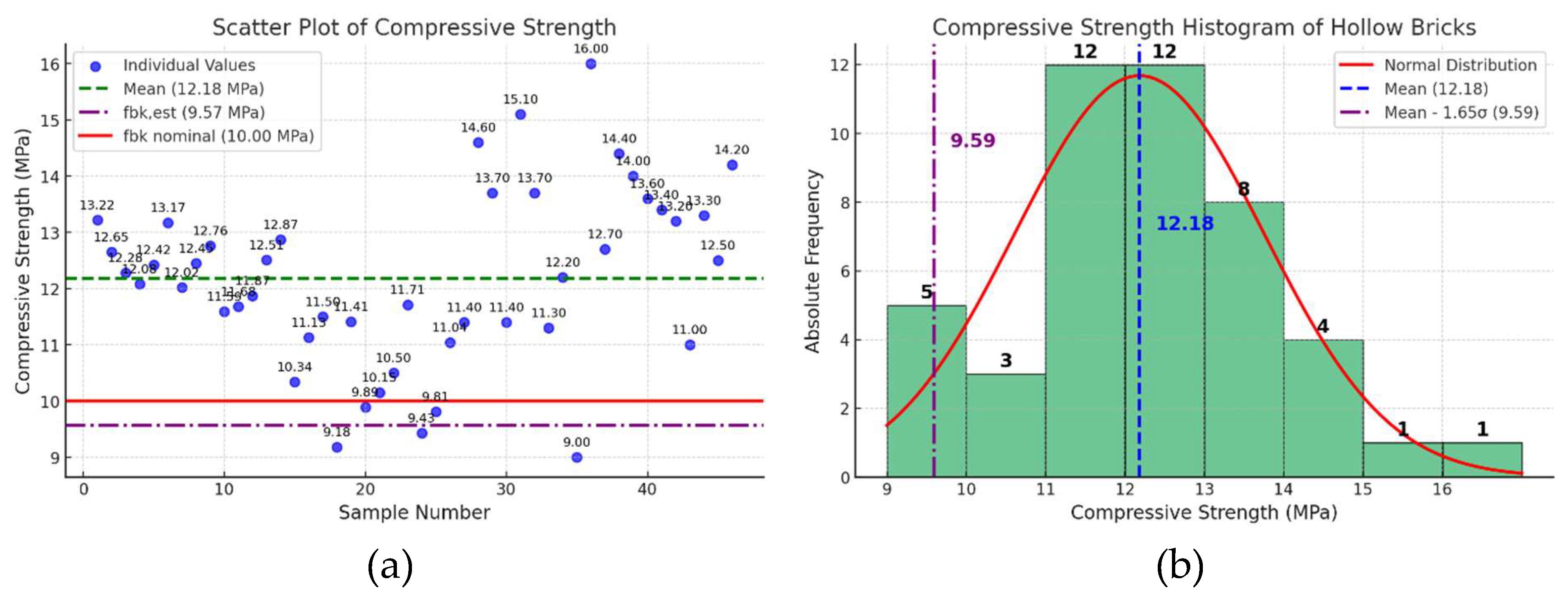

3.1. Clay Units

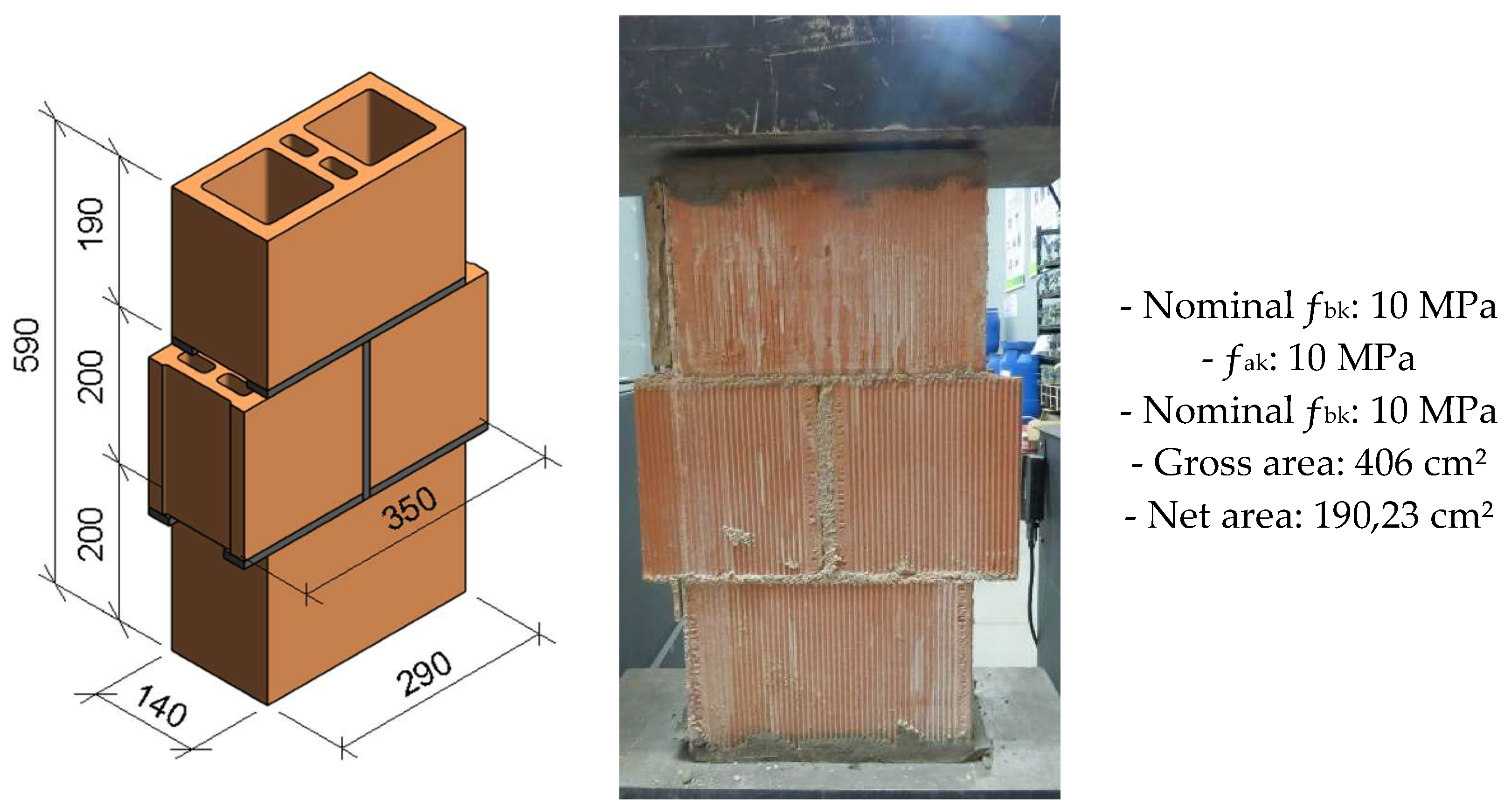

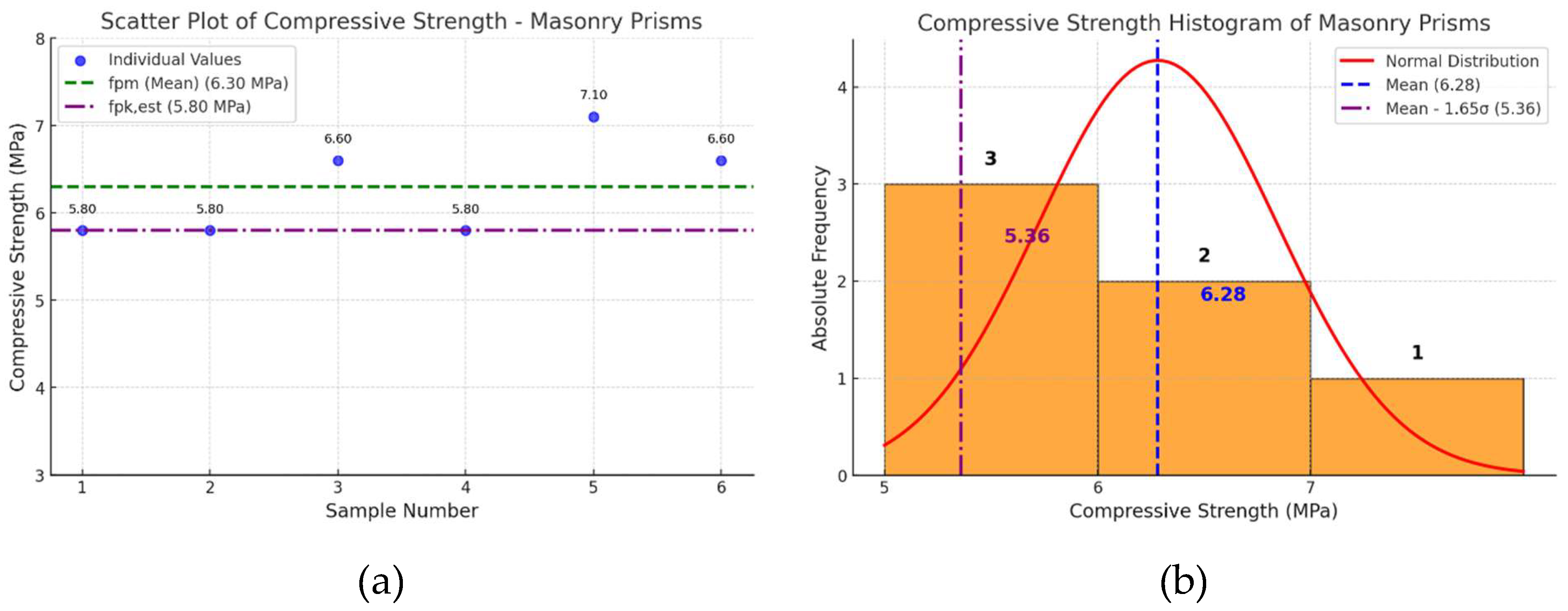

3.2. Two-Course Masonry Specimen

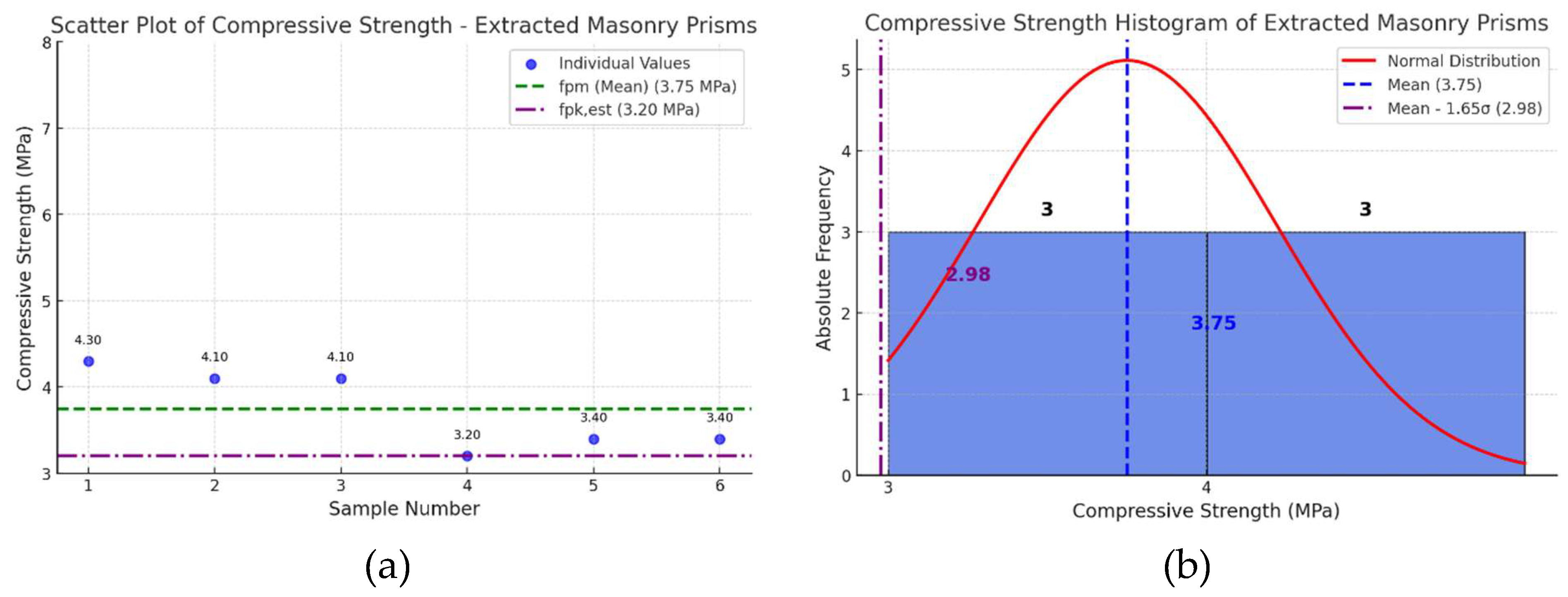

3.3. Two-Course Masonry Specimen, Extracted from Real-Scale Masonry Wall

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- a)

- The analysis of the experimental results confirms that the compressive strength of structural masonry is significantly influenced by the height of the masonry specimen, with more slender specimens exhibiting lower strength due to increased susceptibility to lateral cracking. These findings align with previous studies [25,39] and suggest that normative adjustment coefficients may be useful when interpreting test results from specimens with geometries different from the standard two-unit specimen, such as those extracted from completed masonry structures.

- b)

- The greater variability and dispersion of results for the extracted masonry specimens can be attributed to the influence of in-situ construction factors, such as heterogeneity in unit placement, variations in mortar joint thickness, and other material and execution-related variables that are not present in laboratory-molded specimens, such as the juxtaposition between courses. Additionally, the extraction and transportation process may also contribute to the increased dispersion of results.

- c)

- In the normative context, NBR 16868 [5] establishes relationships between the compressive strength of units, masonry specimens, and walls, with specimens serving as an intermediate element for predicting the in-field strength of masonry. Considering the results of this study, the exclusive use of characteristic strength values to compare molded and extracted specimens can be questioned, as the observed dispersion of results suggests that adopting average values may provide a more realistic representation of the structural behavior of masonry.

- d)

- The substantial difference between the average and characteristic strength values of the extracted specimens suggests that the variation coefficients adopted in normative standards should account for these aspects, considering the greater dispersion of results obtained in situ. This adjustment could enable more realistic predictions of the final compressive strength of structural masonry in the field, reducing error margins.

References

- ABASI, A. et al. Influence of prism geometry on the compressive strength of concrete masonry. Construction and Building Materials, 2020, v. 264, p. 1-17. [CrossRef]

- ÁLVAREZ-PÉREZ, J. et al. Multifactorial behavior of the elastic modulus and compressive strength in masonry prisms of hollow concrete blocks. Construction and Building Materials, v. 241, p. 1–18, 2020. [CrossRef]

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS (ABNT). NBR 15270-1:2023. Componentes cerâmicos — Blocos cerâmicos para alvenaria estrutural e de vedação — Parte 1: Requisitos. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2023.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS (ABNT). NBR 15270-2:2023. Componentes cerâmicos — Blocos cerâmicos para al-venaria estrutural e de vedação — Parte 2: Métodos de ensaio. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2023.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS (ABNT). NBR 16868-1:2020. Alvenaria estrutural — Parte 1: Projeto. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS (ABNT). NBR 16868-3:2020. Alvenaria estrutural — Parte 3: Métodos de ensaio. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020.

- ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE NORMAS TÉCNICAS (ABNT) NBR 13281-1:2023. Argamassas inorgânicas — Requisitos e métodos de ensaios — Parte 1: Argamassas para revestimento de paredes e tetos. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2023.

- ASTM. E447-97: Test methods for compressive strength of laboratory constructed masonry prisms. Pennsylvania: American Society for Testing and Materials, 1997.

- AUSTRALIAN STANDARD. AS 3700: masonry structures. Sydney, 2011.

- BUREAU OF INDIAN STANDARDS. IS: 1905 - Indian standard code of practice for structural use of unreinforced masonry. New Delhi: BIS, 1987.

- CANADIAN STANDARDS ASSOCIATION. CSA S304: Design of Masonry Structures. Mississauga, ON, Canada, Canadian Standards Association, 2014.

- CHAHINE, G. N. Behaviour characteristics of face shell mortared block masonry under axial compression. Master of Engineering Degree. McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada, 1989. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11375/7219.

- COLVILLE, J.; MILTENBERGER, M. A.; WOLDE-TINSAE, A. M. Hollow concrete masonry modulus of elasticity. In: The sixth North American Masonry Conference. Philadelphia, PA: Pennsylvania, 1993. p. 1195-1208.

- DHANASEKAR, M. et al. On the in-plane shear response of the high bond strength concrete masonry walls. Materials and Structures, 2017, v. 50. [CrossRef]

- DRYSDALE, R. G.; HAMID, A. A. Behavior of concrete block masonry under axial compression. ACI Journal Proceedings, 1979, v. 76, n. 6, p. 707–722.

- DROUGKAS, A. et al. The confinement of mortar in masonry under compression: experimental data and micro-mechanical analysis. International Journal of Solids and Structures, 2019, v. 162, p. 105–120. [CrossRef]

- EUROPEAN COMMITTEE FOR STANDARDIZATION (EN). EN 1996-1-1:2022. Eurocode 6: Design of masonry structures – Part 1-1: General rules for reinforced and unreinforced masonry structures. Brussels, 2022.

- EUROPEAN COMMITTEE FOR STANDARDIZATION (EN). Masonry - Structural design of reinforced and unreinforced masonry structures. EN 1052, 2007. Brussels: CEN, 2007.

- FORTES, E. S. et al. Compressive strength of masonry constructed with high strength concrete blocks. Revista IBRACON de Estruturas e Materiais, 2017, v. 10, n. 6, p. 1273–1319. [CrossRef]

- FORTES, E. S.; MOLITERNO, G. F.; SILVA, F. S. Relationship between the compressive strength of concrete masonry and the compressive strength of concrete masonry units. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 2014, v. 27, p. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- FRANCIS, A. J.; HORMAN, C. B.; JERREMS, L. E. The effect of joint thickness and other factors on compressive strength of brickwork. In: Proceedings of 2nd International Brick Masonry Conference, Stoke-on-Trent, 1971, p. 31–37.

- GANESAN, T. P.; RAMAMURTHY, K. Behavior of concrete hollow-block masonry prisms under axial compression. Journal of Structural Engineering, 1992, v. 118, n. 7, p. 1751–1769. [CrossRef]

- GARZÓN-ROCA, J. et al. Compressive strength of masonry made of clay bricks and cement mortar: estimation based on neural networks and fuzzy logic. Engineering Structures, 2013, v. 48, p. 21–27. [CrossRef]

- HAMID, A. A.; ABBOUD, B. E.; HARRIS, H. G. Direct Modeling of Concrete Block Masonry Under Axial Compression. In: Masonry: Research, Application, and Problems. ASTM STP 871, J. C. Grogan e J. T. Conway, Eds., American Society for Testing and Materials, Philadelphia, 1985, p. 151-166.

- HASSANLI, Reza; ELGAWADY, Mohamed A.; MILLS, Julie E. Effect of dimensions on the compressive strength of concrete masonry prisms. Advances in Civil Engineering Materials, 2015, v. 4, n. 1, p. 1–27. [CrossRef]

- HENDRY, A. W. Structural Brickwork. London: The Macmillan Press, 1981.

- LEITE, Maria de Lourdes Pereira; LIBERATI, Elyson Andrew Pozo; PARSEKIAN, Guilherme Aris. Estimate models of compression strength of prisms from structural masonry components. Revista IBRACON de Estruturas e Materiais, 2024, v. 17, n. 6, e17601. [CrossRef]

- LLORENS, J. et al. Experimental study on the vertical interface of thin-tile masonry. Construction and Building Materials, 2020, v. 261, p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- MOHAMAD, G. et al. Strength, behavior, and failure mode of hollow concrete masonry constructed with mortars of different strengths. Construction and Building Materials, v. 134, 2017, v. 134, p. 489–496. [CrossRef]

- MOHAMAD, G. et al. Stiffness plasticity degradation of masonry mortar under compression: preliminar results. Revista IBRACON de Estruturas e Materiais, 2018, v. 11, p. 279–295. [CrossRef]

- NALON, G. H. et al. Review of recent progress on the compressive behavior of masonry prisms. Construction and Building Materials, 2022, v. 320, 2021. [CrossRef]

- PAGE, A.; BROOKS, D. Load bearing masonry–A review. Proc. of the 7th IBMC, 1985.

- PARSEKIAN, G. A.; SOARES, S. M. Alvenaria estrutural: produção e projeto. São Paulo, Brazil. Ed. Blucher, 2012.

- PAULINO, R. S., TORALLES, B. M. 202.). Influence of the relationships between compressive strengths of mixed and industrialized mortars and concrete blocks on the behavior of masonry prisms. Revista IBRACON De Estruturas E Materiais, , 2024, 17(5), e17503. [CrossRef]

- PRUDÊNCIO JUNIOR, L. R. et al. Análise do comportamento mecânico de prismas de alvenaria estrutural de blocos de concreto. Revista IBRACON de Estruturas e Materiais, 2003, v. 4, p. 65–84.

- RAMALHO, M. A.; CORRÊA, M. R. S. Resistência e deformabilidade da alvenaria estrutural de blocos de concreto. Revista IBRACON de Estruturas e Materiais, 2003, v. 6, p. 97–122.

- RAVULA, S.; SUBRAMANIAM, K. V. Influence of masonry unit properties on compressive strength of masonry walls. Construction and Building Materials, 2017, v. 157, p. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- STEIL, J. F.; PRUDÊNCIO, L. R. Avaliação experimental do comportamento de alvenaria estrutural de blocos de concreto com diferentes tipos de argamassas. Revista Engenharia Civil, 2002, v. 37, p. 25–38.

- THAICKAVIL, Nassif Nazeer; THOMAS, Job. Behaviour and strength assessment of masonry prisms. Case Studies in Construction Materials, 2018, v. 8. [CrossRef]

- THE MASONRY SOCIETY. TMS 402/602: Building Code Requirements for Masonry Structures. Longmont, CO, U.S., The Masonry Society, 2021.

- THOMAS, J.; ANSAR, E. M. Parametric study of the strength of brickwork prisms. In: Proceedings of the First CUSAT National Conference on Recent Advances in Civil Engineering, Kochi, Índia, março de 2004, p. 431-437.

| Specimen | Compressive strength (MPa) |

| 1 | 13,22 |

| 2 | 12,65 |

| 3 | 12,28 |

| 4 | 12,08 |

| 5 | 12,42 |

| 6 | 13,17 |

| 7 | 12,02 |

| 8 | 12,45 |

| 9 | 12,76 |

| 10 | 11,59 |

| 11 | 11,68 |

| 12 | 11,87 |

| 13 | 12,51 |

| 14 | 12,87 |

| 15 | 10,34 |

| 16 | 11,13 |

| 17 | 11,50 |

| 18 | 9,18 |

| 19 | 11,41 |

| 20 | 9,89 |

| 21 | 10,15 |

| 22 | 10,50 |

| 23 | 11,71 |

| 24 | 9,43 |

| 25 | 9,81 |

| 26 | 11,04 |

| 27 | 11,40 |

| 28 | 14,60 |

| 29 | 13,70 |

| 30 | 11,40 |

| 31 | 15,10 |

| 32 | 13,70 |

| 33 | 11,30 |

| 34 | 12,20 |

| 35 | 9,0 |

| 36 | 16,0 |

| 37 | 12,70 |

| 38 | 14,40 |

| 39 | 14,0 |

| 40 | 13,60 |

| 41 | 13,40 |

| 42 | 13,20 |

| 43 | 11,0 |

| 44 | 13,30 |

| 45 | 12,50 |

| 46 | 14,20 |

| Specimen | Compressive strength (MPa) |

| 1 | 5,80 |

| 2 | 5,80 |

| 3 | 5,80 |

| 4 | 6,60 |

| 5 | 7,10 |

| 6 | 6,60 |

| Specimen | Compressive Strength (MPa) |

| 1 | 4,30 |

| 2 | 4,10 |

| 3 | 4,10 |

| 4 | 3,20 |

| 5 | 3,40 |

| 6 | 3,40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).