1. Introduction

Carbon dioxide is an important electrophilic C

1 resource widely used in organic syntheses. However, it is produced as inevitable wastes during the combustion of fossil fuels and respiration of living organisms, and is thus believed to significantly contribute to the global warming. Therefore, intensive research is currently devoted to carbon dioxide capture and utilization (CCU) in order to protect the earth’s environment. [

1,

2] While capture or storage of carbon dioxide has been attempted using various metal organic frameworks [

3,

4,

5] and amine functionalized organic polymers, [

6,

7,

8] the low capacity and poor stability of captured carbon dioxide have often caused problems because carbon dioxide is released, even at a slightly elevated temperature. Thus, the complete and irreversible covalent bond formation between carbon dioxide and anionic carbon was directed as an alternative strategy of CCU, using organometallic reagents (PhMgBr, PhLi). Despite the rapid capture of carbon dioxide, these organometallic reagents are too sensitive to survive in environmental moisture. To overcome their vulnerability, soft organic metal-based reagents have been developed in conjunction with acetylide substrates. [

9,

10] However, these reagents still require a high temperature to make a covalent bond with CO

2, thus hampering their practical application.

As a current alternative in the research of CCU, metal-salen complex-based Lewis acid catalysts are emerging. [

11] Although the metal-salen complexes show high efficiency in CCU, [

12,

13,

14] most of them suffer severe limitation due to the competitive coordination or hydrolysis by the environmental moisture, and their catalytic activities are eventually lost. Therefore, the use of chemically stable and moisture-insensitive organocatalysts is attracting increasing interest as a sustainable method for CCU.

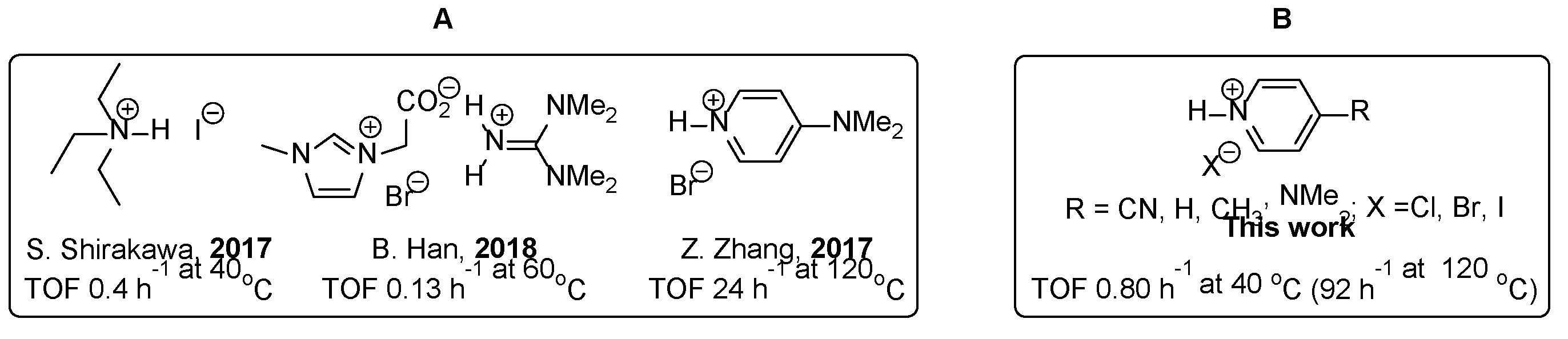

Numerous amine-based organic catalysts have recently been developed for the production of carbonates from epoxides and carbon dioxide (

Scheme 1). Among them, the most effective catalysts working under mild conditions are derived from triethylammonium iodide and imidazolium bromide. Shirakawa’s group utilized simple triethylamine hydroiodide as a bifunctional catalyst for cyclic carbonate formation. [

15] Triethylammonium hydrogen activates an epoxide group via H-bonding and produces a cyclic carbonate at mild temperature (40

oC) with turnover frequency (TOF) = 0.4 h

-1. More recently, Han’s group constructed a novel organocatalyst based on ionic liquids, by combining methylimidazolium carboxylic acid with guanidine. [

16] While the organic catalyst showed better efficiency with alkyl epoxides, its reaction was somewhat slower with aryl epoxide (TOF 0.13 h

-1), thus requiring a high reaction temperature (60

oC) as well as a significant amount of catalyst loading (25 mol %). Interestingly, Zhang’s group introduced dimethylaminopyridine hydrobromide (DMAP·HBr) as a sustainable catalyst for cyclic carbonate formation and achieved an efficient catalytic transformation of styrene oxide into cyclic carbonate at high temperature (120

oC) with TOF = 24 h

-1. [

17] The authors proposed an elegant reaction mechanism from the delocalized resonance structure of DMAP, they did not perform further experiments such as a counteranion effect or an electronic effect for the given pyridine derivatives. In addition, the reaction was performed at 120

oC, significantly greater than ambient conditions. Inspired by the well-known property of pyridine as a nucleophilic catalyst to carbonyl groups [

18] and the recent work by Zhang’s group, we started our research on carbon dioxide utilization using a series of pyridinium hydrohalides and found that dimethylaminopyridinium hydroiodide (DMAP·HI) is a superior catalyst for the formation of cyclic carbonates.

Scheme 1.

Organic catalysts for cyclic carbonate synthesis. (A) Previously reported organic catalysts and their reaction efficiencies of styrene oxide with 1 atm CO2, where TOF stands for turnover frequency. (B) p-Substituted pyridine·HX derivatives investigated in this work.

Scheme 1.

Organic catalysts for cyclic carbonate synthesis. (A) Previously reported organic catalysts and their reaction efficiencies of styrene oxide with 1 atm CO2, where TOF stands for turnover frequency. (B) p-Substituted pyridine·HX derivatives investigated in this work.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Model Reaction

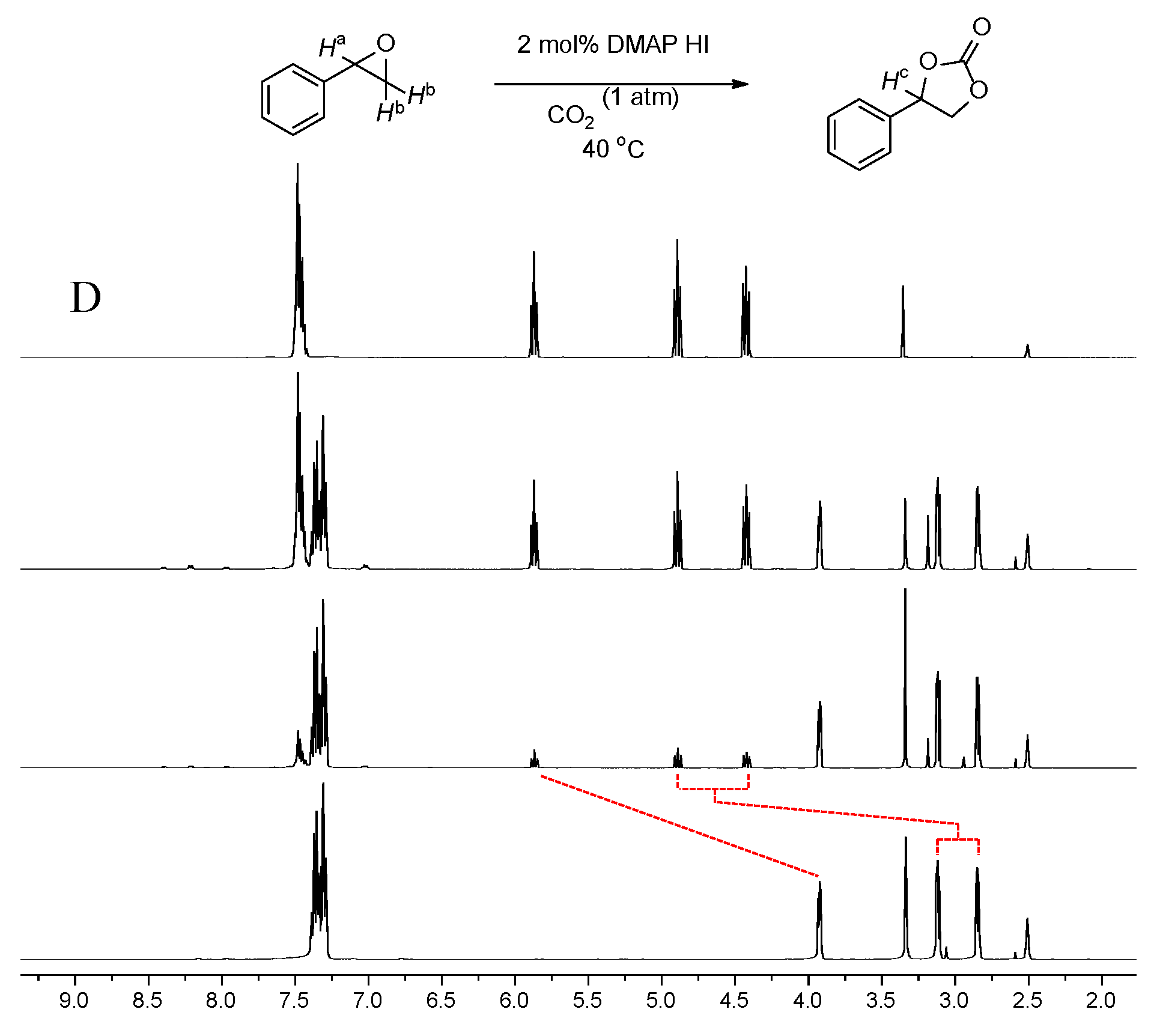

A preliminary and model experiment was carried out for cyclic carbonate synthesis by employing styrene oxide as a model compound under a CO

2 balloon of. The resulting cyclic carbonate formation was monitored using

1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy in the presence of DMAP⸱HI salt. Styrene oxide was slowly transformed into cyclic carbonate in the presence of 2 mol % of DMAP⸱HI. The methine proton of styrene oxide (

Ha) at 3.90 ppm clearly shifted into a downfield region to afford a proton peak (

Hc) at 5.88 ppm. In addition, the methylene protons (

Hb) as well as the aromatic peaks of the initial epoxide also shifted downfield into a set of peaks of cyclic carbonate, indicating that an electron-withdrawing functional group was introduced to afford a cyclic carbonate from the epoxide. The product was purified by column chromatography and identified as a cyclic carbonate (

Figure 1). This experiment demonstrates that styrene oxide underwent a clean reaction to cyclic carbonate with a catalytic amount of DMAP⸱HI under 1 atm CO

2.

2.2. Counterion Effect

Encouraged by the model reaction, the counterion effect of the pyridinium salts was investigated by adding an equimolar ratio of strong acid (HCl, HBr, or HI) to DMAP. The resulting catalysts (10 mol% each), DMAP·HCl, DMAP·HBr, and DMAP⸱HI, were incubated with styrene oxide (5.0 mmol) and the amounts of cyclic carbonate relative to styrene oxide were measured 12 h after incubation at 40

oC under 1 atm CO

2. Catalyst DMAP⸱HI provided a cyclic carbonate with excellent yield (96%) compared to two the other congeners: DMAP·HCl (20%) and DMAP·HBr (37%). This result indicates that the most efficient reaction was achieved by the iodide counterion, owing to its plausible dual activity as a nucleophile and a leaving group, as observed in previous studies. [

19,

20] It is also noticeable that DMAP·HBr, the Zhang’s catalyst, had a lower TOF value at a mild reaction temperature (0.30 h

-1 at 40

oC).

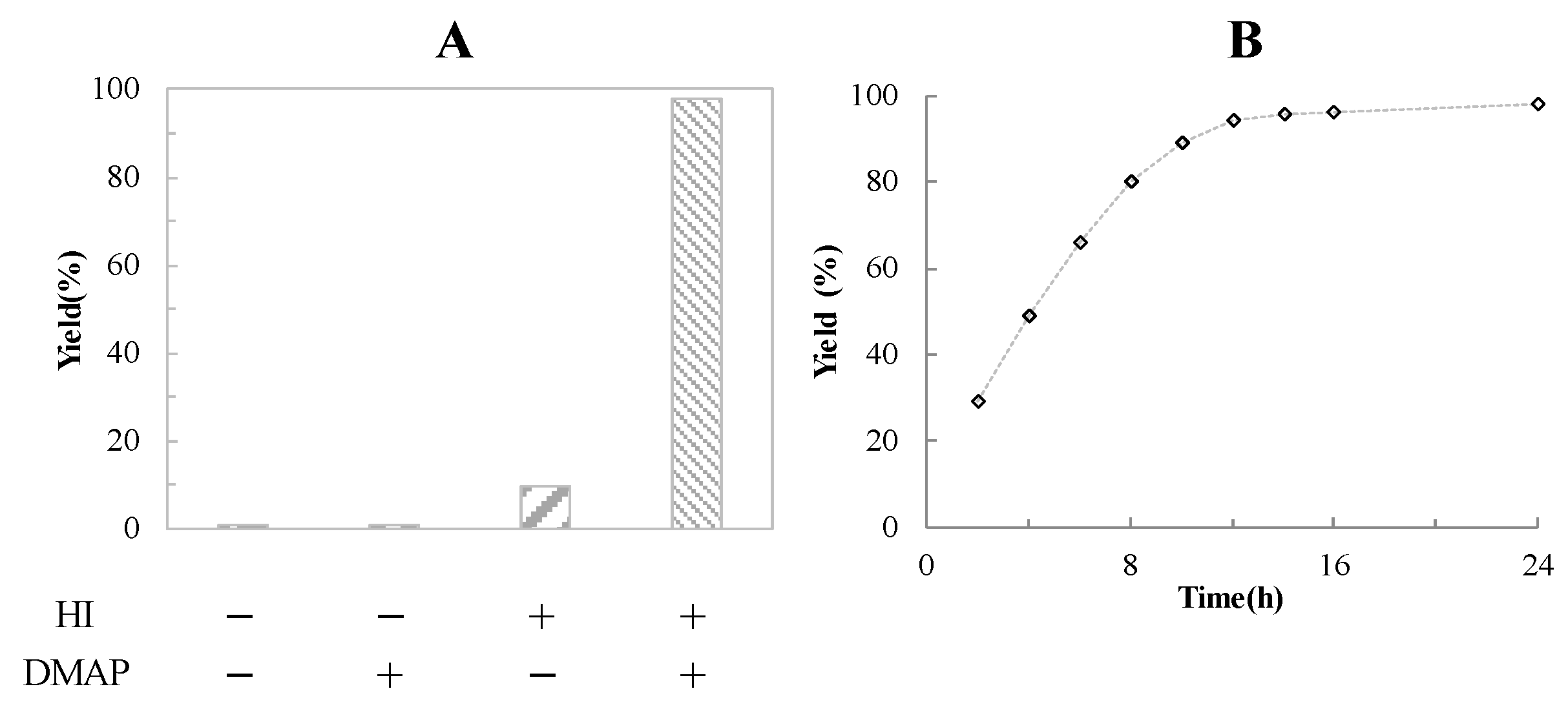

2.3. Analysis of the Catalyst System (DMAP-HI)

As a control experiment, we monitored the cyclic carbonate formation reaction of styrene oxide (5.0 mmol) without any pyridinium salts and found that no products were formed (< 1%) at 40

oC under 1 atm CO

2 (

Table 1, entry 1). Moreover, the reaction of styrene oxide in the presence of DMAP (10 mol%) and absence of HI did not proceed, indicating that DMAP alone cannot open a neutral epoxide (

Table 1, entry 2). Interestingly, the reaction proceeded to the cyclic carbonate in the sole presence of HI, allowing a small amount of carbonate (9.9%) together with 8.3% of 2-iodo-2-phenylethan-1-ol (

Int), a typical epoxide opening product under an acidic condition (

Table 1, entry 3). This abnormal phenomenon can be explained as follows: Carbonate formation will stop with the formation of intermediate

Int, since HI is irreversibly consumed as a reagent of the epoxide ring opening reaction. In the presence of DMAP⸱HI, the cyclic carbonate formation continued until completion (

Table 1, entry 7). These experiments indicated that both HI and DMAP are essential components for the success of the catalyst in cyclic carbonate formation from epoxide as represented in

Figure 2A. The optimal reaction time was also determined from a time-dependent reaction profile of the cyclic carbonate formation, and it was found that the reaction was complete within 12 h (

Figure 2B).

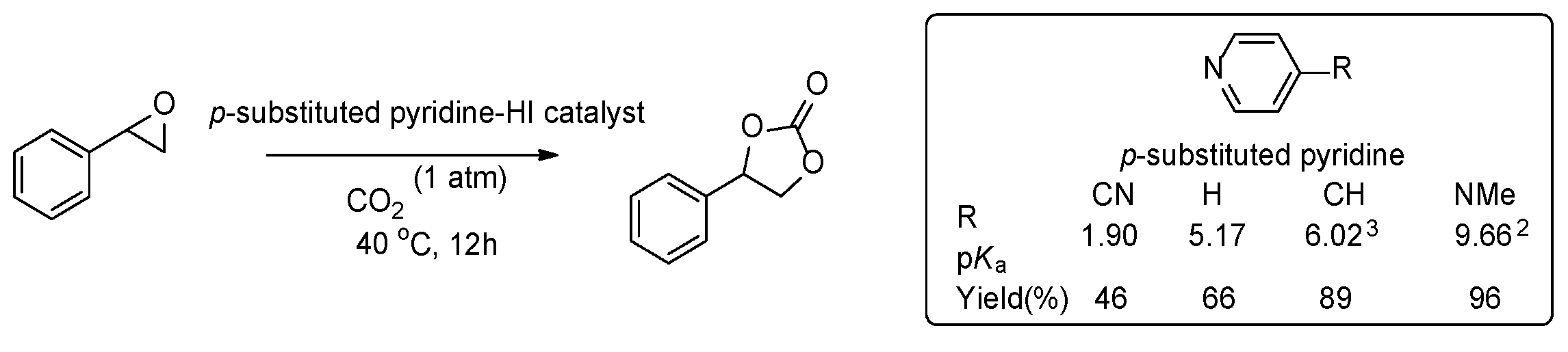

2.4. Structure and Activity Relationship of Catalyst: Electronic Effect

Organic catalysts of the epoxide-to-carbonate transformation usually consist of three components: H-bond donor, halide, and base. H-bond donors are commonly regarded as crucial activators of epoxide, while halides are considered to play a dual role not only as a nucleophile for the activated epoxide but also as a leaving group. However, the role of bases is not well understood and sometimes neglected with organic catalysts for cyclic carbonate. If the electrophilic activation of epoxide via H-bonding and the subsequent nucleophilic attack of halide were critical rate-determining steps during the cyclic carbonate formation, we could expect significant rate acceleration with acidic pyridinium iodide derivatives. Thus, we attempted to assess the acidity effect of pyridinium iodide salts by modulating the electronic property of

p-substituted pyridines (

Scheme 2). A parallel reaction of styrene oxide (5.0 mmol) was investigated at 40

oC under 1 atm CO

2 using a series of

p-substituted pyridinium iodide salts (0.50 mmol) from the electron-withdrawing cyano group to the electron-donating dimethylamino group with a broad range of p

Ka’s in water (1.90 ~ 9.66). [

21] Unexpectedly, the reaction of the most acidic

p-cyanopyridinium iodide (

p-CNPy⸱HI) was far slower than that of the other congeners. While catalyst

p-CNPy⸱HI (p

Ka 1.9) gave a 46% yield, the more basic pyridine derivatives exhibited higher yields for cyclic carbonates: Py⸱HI (p

Ka 5.2) in 66%,

p-CH

3Py⸱HI (p

Ka 6.0) in 89%, and DMAP⸱HI (p

Ka 9.7) in 96% yields (

Table 1, entries 4–7). This unusual result suggests that the epoxide activation via H-bonding is not an exclusive factor for determining the overall reaction rates, and other factors will be involved in the epoxide–to–cyclic carbonate transformation reaction.

Scheme 2.

Reaction of styrene oxide (5 mmol) with 1 atm CO2 in the presence of various p-substitured pyridinium iodide derivatives.

Scheme 2.

Reaction of styrene oxide (5 mmol) with 1 atm CO2 in the presence of various p-substitured pyridinium iodide derivatives.

We determined the optimal amounts of catalysts. When reducing the amount of catalyst loading from 10 mol% to 1 mol%, the chemical yields dramatically decreased from 96% to 17%, although the catalyst efficiency (TOF) increased by 1.8 times (

Table 1, entries 7-10). We chose 10 mol % catalyst DMAP⸱HI as a practical condition for the carbonate formation. In addition, we investigated the effect of temperature on the yields by varying the reaction temperature from 40

oC to 25

oC and found the reaction occurred in a high yield at 40

oC (

Table 1, entries 7 and 11-12). For comparison with Zhang’s catalyst (DMAP⸱HBr, TOF 24 h

-1), we heated the reaction mixture upto 120

oC and found that catalyst DMAP⸱HI was sustainable at the high temperature and the TOF value was as high as 92 h

-1. This experiment demonstrated that DMAP⸱HI is 3.8 times more efficient than DMAP⸱HBr.

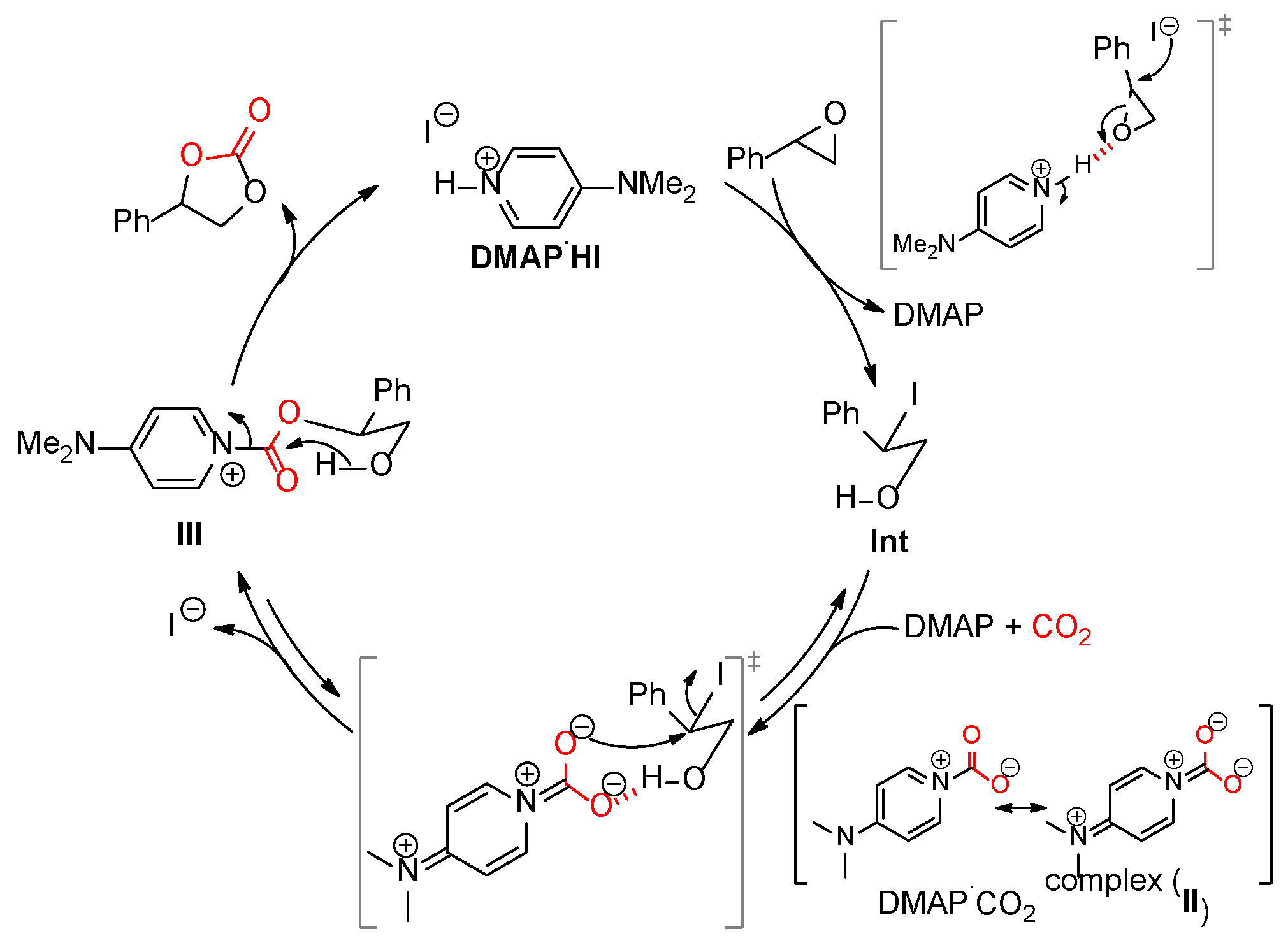

2.5. Proposed Mechanism

The experimental evidence above indicated that an intermediate (

Int) formed rapidly and irreversibly (

Scheme 3). Further transformation into the cyclic carbonate took place readily. However, we observed that the overall reaction was very slow and took 12 h to completion. These results imply that DMAP⸱CO

2 complex formation is a critical step in the epoxide-to-carbonate transformation reaction. First, the cyclic carbonate formation reaction of styrene oxide is believed to proceed via an intermediate

Int and to releases free DMAP. The resulting DMAP can attack CO

2 as an active nucleophile to form a short-lived pyridinium carboxylate (DMAP⸱CO

2,

II). [

23] This dianionic carboxylate is assumed to be highly basic and nucleophilic, and can thus be readily accessed by the alcohol group of

Int via H-bonding. The H-bond system is supposed to undergo a substitution reaction and to form an activated ester (

III), which finally delivers a tetrahedral intermediate by intramolecular nucleophilic acyl attack from the neighboring alcohol group and the subsequent collapse of tetrahedral oxyanion intermediate leads to cyclic carbonate, regenerating the catalyst.

Scheme 3.

A proposed catalytic mechanism of DMAP⸱HI through the nucleophilic CO2 activation of DMAP.

Scheme 3.

A proposed catalytic mechanism of DMAP⸱HI through the nucleophilic CO2 activation of DMAP.

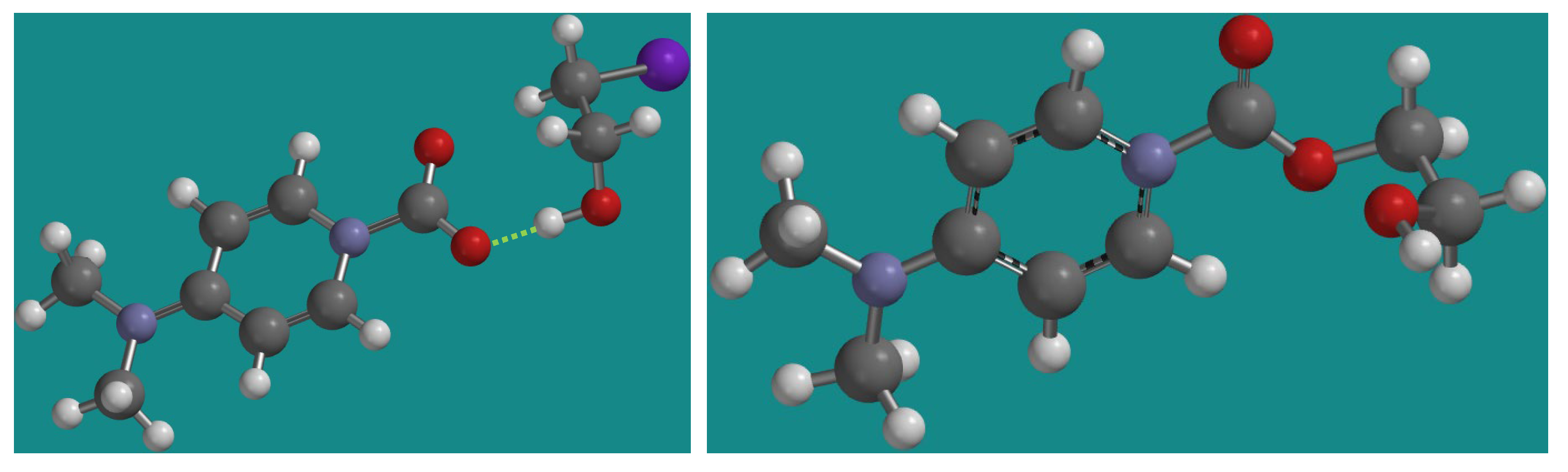

DFT calculation of the intermediates was carried out using the B3LYP, 6-31G* basis set (

Figure 4). An interesting hydrogen bond between

II and

Int was clearly observed, where the oxyanion of

II possibly can reinforce the hydrogen bonding interaction with alcohol (1.545 Å of H-bond distance and 171° of O

…H-O bond angle). The resulting H-bond caused a proximal distance between the carboxylate anion and the iodoalkyl group (2.998 Å of O

…CHI distance) to favor an S

N2 reaction. Finally, the ester intermediate

III disposed of an alcohol group within a reaction sphere with the activated carbonyl groups and immediately underwent the cyclic carbonate formation reaction via a favorable 5-exo-trig approach according to the Baldwin rule. [

24]

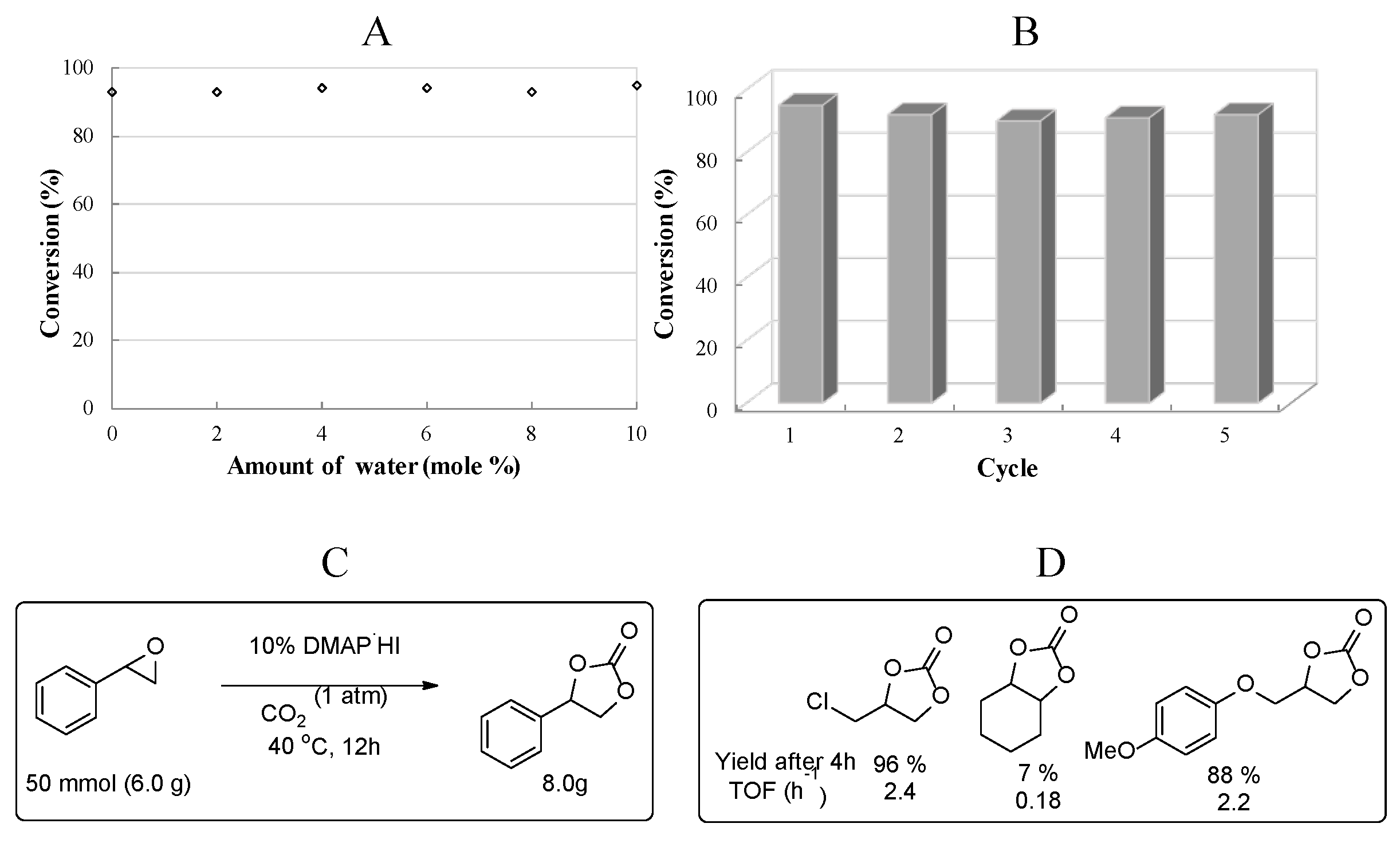

2.6. Practical Applicability

Interestingly, the catalytic efficiency of DMAP·HI was hardly affected by the environmental moisture and it was still active with 10 mol % water addition and did not show any significant loss of the catalytic activity (

Figure 5A). Therefore, the organic catalyst system is promising for practical application even in the presence of ambient moisture existing as a common pollutant in waste CO

2. We also tested the reusability of the organic catalyst, since DMAP·HI is a very stable chemical species. After the first cycle, the ionic catalyst was extracted from the reaction mixture by adding water and dried over by evaporation of the aqueous layer. The resulting solid was reused directly for the next run. The catalytic activity of DMAP·HI did not change notably and gave a yield of more than 90% even after recycling five times, showing the robust stability of the DMAP·HI system (

Figure 5B).

Moreover, the catalyst was applied in a scale-up reaction. A multigram scale of neat styrene oxide (5.7 mL, 6.0 g) was incubated in the presence of 10 mol% DMAP·HI at 40

oC under 1 atm CO

2 to afford 8.0 g of the cyclic carbonate (98% yield) by selective removal of DMAP·HI through extraction. Further column chromatographic purification yielded 7.7g (94%) of cyclic carbonate in an analytically pure form (

Figure 5C).

For the substrate scope, several alkyl substituted epoxides were investigated for the carbonate formation reaction under the similar conditions (

Figure 5D). In general, the terminal alkyl epoxides underwent faster reactions with better efficiency than styrene oxide, probably due to the anchimeric effect of neighboring heteroatoms. Cyclic carbonates from epichorohydrin and aryloxyproylene oxide efficiently formed in 96% and 88% yields, respectively. However, as an internal epoxide, cyclohexane oxide did not proceed effectively due to the steric and 1,3-diaxial repulsion. [

25]

3. Materials and Methods

Typical reaction condition of epoxide with CO2: DMAP (0.061 g, 0.50 mmol), and HI (0.112 g, 57%, 0.50 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL vial to afford DMAP⸱HI as an ionic liquid catalyst. After epoxide (5.0 mmol) was added, the reaction mixture was stirred under 1 atm CO2 pressurized reactor for accurate and closed reaction. After 12 h at 40 oC, the sample was analyzed by 1H NMR spectroscopy to determine the yield.

4. Conclusions

A series of pyridinium iodide-based catalysts were investigated as green and sustainable organic catalysts for carbon dioxide utilization under ambient conditions. DMAP⸱HI was found to be a superior catalyst for cyclic carbonate formation, with an excellent yield and high efficiency (96%, TOF 0.80 h-1) at a mild temperature without any solvents or additives. Elaborative mechanistic studies indicated that DMAP played a pivotal role as a nucleophile toward carbon dioxide during the cyclic carbonate formation. The organic catalyst could be recycled five times without any significant loss of catalytic activity, and was successfully applied for the multi-gram scale of cyclic carbonate synthesis under ambient conditions even in the presence of moisture.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization and methodology, H.-J.K.; formal analysis and investigation, J.-H.D. and W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-H.D. and W.L.; writing—review and editing, H.-J.K.; funding acquisition, H.-J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

“This research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea, grant number 2017R1A2B4006706”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCU |

Carbon dioxide capture and utilization |

| DMAP |

Dimethylaminopyridine |

| NMR |

Nuclear magnetic resonance |

References

- IPCC Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2007, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007.

- Karl, T. R.; Trenberth, K. E. Modern Global Change. Science, 2003, 302, 1719–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, A. H.; Dai, S. (Eds.), Porous Materials for Carbon Dioxide Capture, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2014.

- Sumida, K.; Rogow, D. L.; Mason, J. A.; McDonald, T. M.; Bloch, E. D.; Herm, Z. R.; Bae, T.-H.; Long, J. R. Carbon dioxide capture in metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Rev., 2012, 112, 724–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, K. S.; Millward, A. R.; Dubbeldam, D.; Frost, H.; Low, J. J.; Yaghi, O. M.; Snurr, R. Q. Understanding inflections and steps in carbon dioxide adsorption isotherms in metal-organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2008, 130, 406–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.; Min, K.; Kim, C.; Ko, Y. S.; Jeon, J. W.; Seo, H.; Park, Y.-K.; Choi, M. Epoxide-functionalization of polyethyleneimine for synthesis of stable carbon dioxide adsorbent in temperature swing adsorption. Nat. Commun., 2016, 7, 12640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, T. M.; Long, J. R.; et al. Cooperative insertion of CO2 in diamine-appended metal-organic frameworks. Nature, 2015, 519, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goeppert, A.; Czaun, M.; May, R. B.; Prakash, G. K. S.; Olah, G. A.; Narayanan, S. R. Carbon dioxide capture from the air using a polyamine based regenerable solid adsorbent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 20164–20167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S. H.; Kim, K. H.; Hong, S. H. arbon Dioxide Capture and Use: Organic Synthesis Using Carbon Dioxide from Exhaust Gas. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2014, 53, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruneau, C.; Dixneuf, P. H. Catalytic incorporation of CO2 into organic substrates: Synthesis of unsaturated carbamates, carbonates and ureas. J. Mol. Catal., 1992, 74, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wa, L.; Jackstell, R.; Beller, M. Using carbon dioxide as a building block in organic synthesis. Nat. Commun., 2015, 6, 5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sujith, S.; Min, J. K.; Seong, J. E.; Na, S. J.; Lee, B. Y. A highly active and recyclable catalytic system for CO2/propylene oxide copolymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2008, 47, 7306–7309. [Google Scholar]

- North, M.; Pasquale, R. Mechanism of cyclic carbonate synthesis from epoxides and CO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2946–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decortes, A.; Kleij, A. W. Ambient Fixation of Carbon Dioxide using a Zn(II)-salphen Catalyst. ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 831–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumatabara, Y.; Okada, M.; Shirakawa, S. Triethylamine Hydroiodide as a Simple Yet Effective Bifunctional Catalyst for CO2 Fixation Reactions with Epoxides under Mild Conditions. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng., 2017, 5, 7295–7301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, H.; Qian, Q.; Xie, C.; Han, B. Dual-ionic liquid system: an efficient catalyst for chemical fixation of CO2 to cyclic carbonates under mild conditions. Green Chem., 2018, 20, 2990–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fan, F.; Xing, H.; Yang, Q.; Bao, Z.; Ren, Q. Efficient Synthesis of Cyclic Carbonates from Atmospheric CO2 Using a Positive Charge Delocalized Ionic Liquid Catalyst. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng., 2017, 5, 2841–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayden, J.; Greeves, N.; Warren, S. Organic Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Oxford: New York, USA, 2012; pp. 198–200. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, W.; Su, Q.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Ng, F.T.T. Ionic Liquids: The Synergistic Catalytic Effect in the Synthesis of Cyclic Carbonates. Catalysts 2013, 3, 878–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Song, J. L.; Liu, H. Z.; Liu, J. L.; Zhang, Z. F.; Jiang, T.; Fan, H. L.; Han, B. X. One-pot conversion of CO2 and glycerol to value-added products using propylene oxide as the coupling agent. Green Chem., 2012, 14, 1743–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jencks W. P.; Regenstein, J. Handbook of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 4th Ed. 2010.

- Bordwell, F. G. Equilibrium acidities in dimethyl sulfoxide solution. Acc. Chem. Res., 1988, 21, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The role of pyridine as a base was excluded because we observed the reaction rate of 2,5-dimethylpyridien (lutidine, pKa 6.77) was much slower than those of 2-methyl (2-picoline, pKa 5.97) or 4-methylpyrdine (4-picoline, pKa 6.02). Lutidine (3.5%), 2-picoline (35%), and 4-picoline (89%).

- Clayden, J.; Greeves, N.; Warren, S. Organic Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Oxford: New York, USA, 2012; pp. 810–814. [Google Scholar]

- Clayden, J.; Greeves, N.; Warren, S. Organic Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Oxford: New York, USA, 2012; pp. 869–870. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).