Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

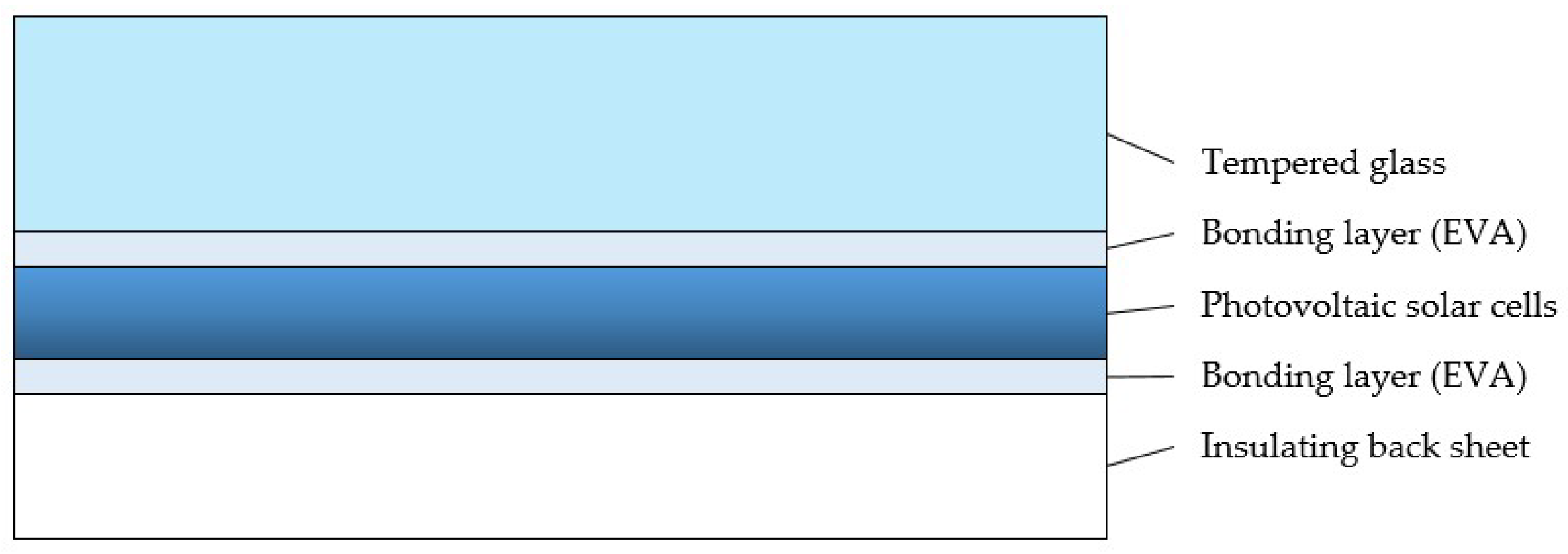

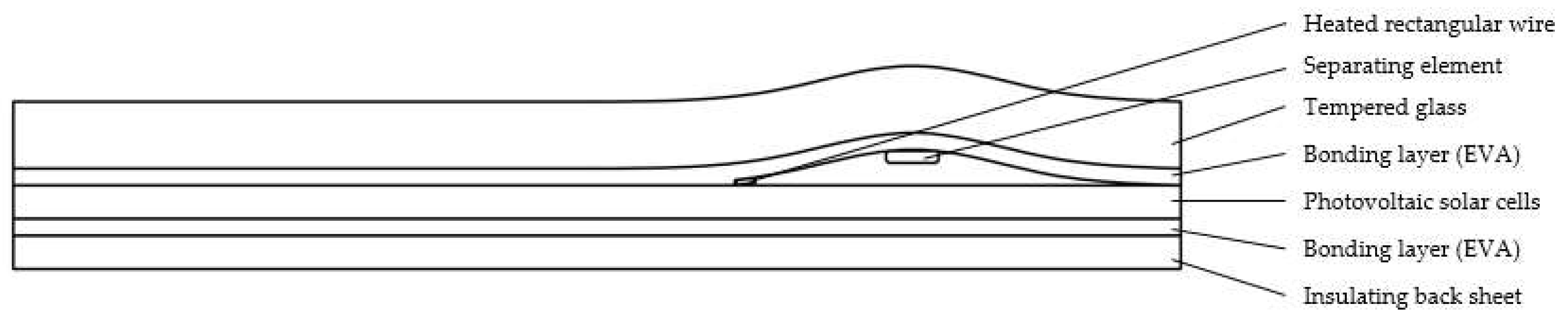

2.1. Test Samples

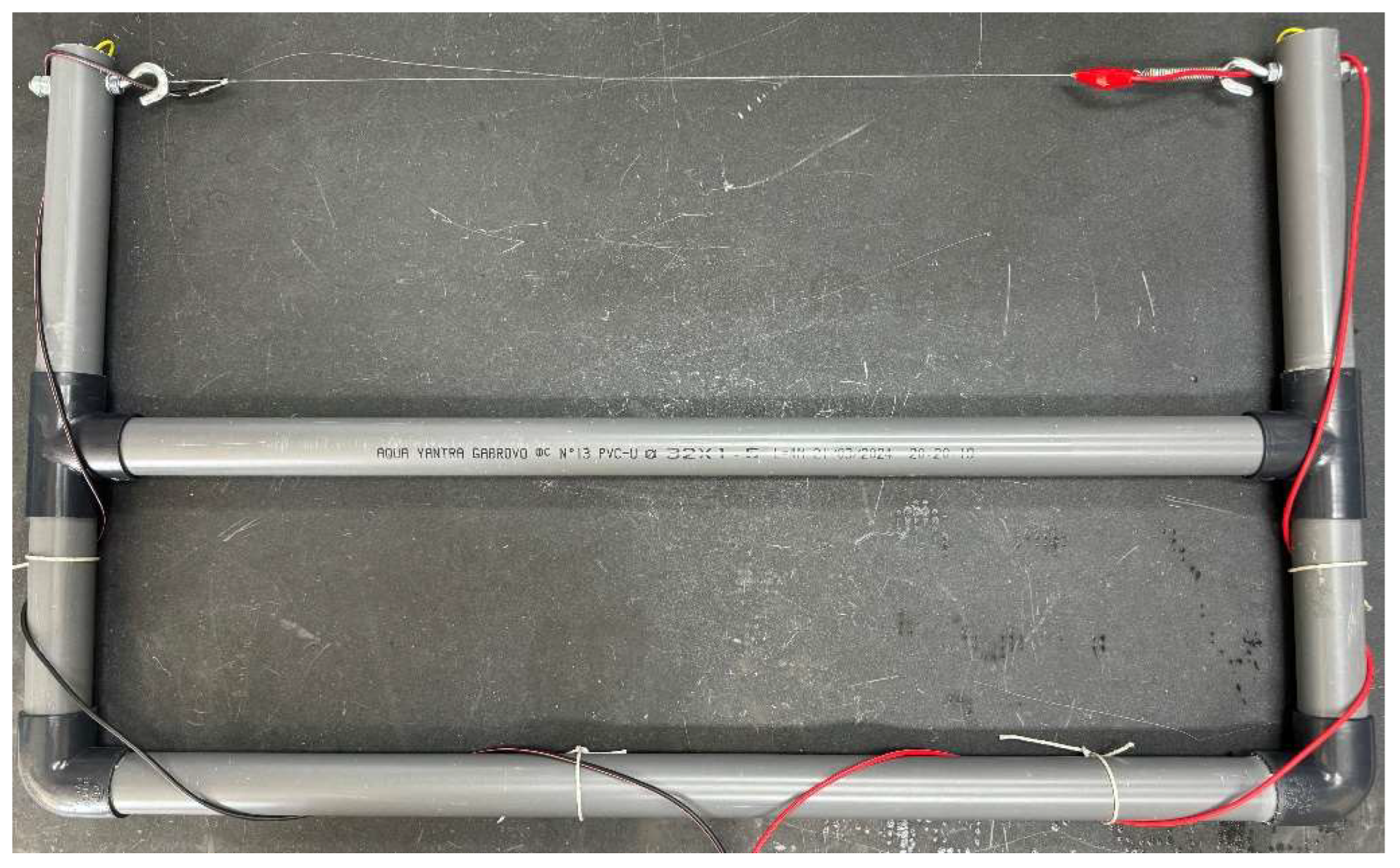

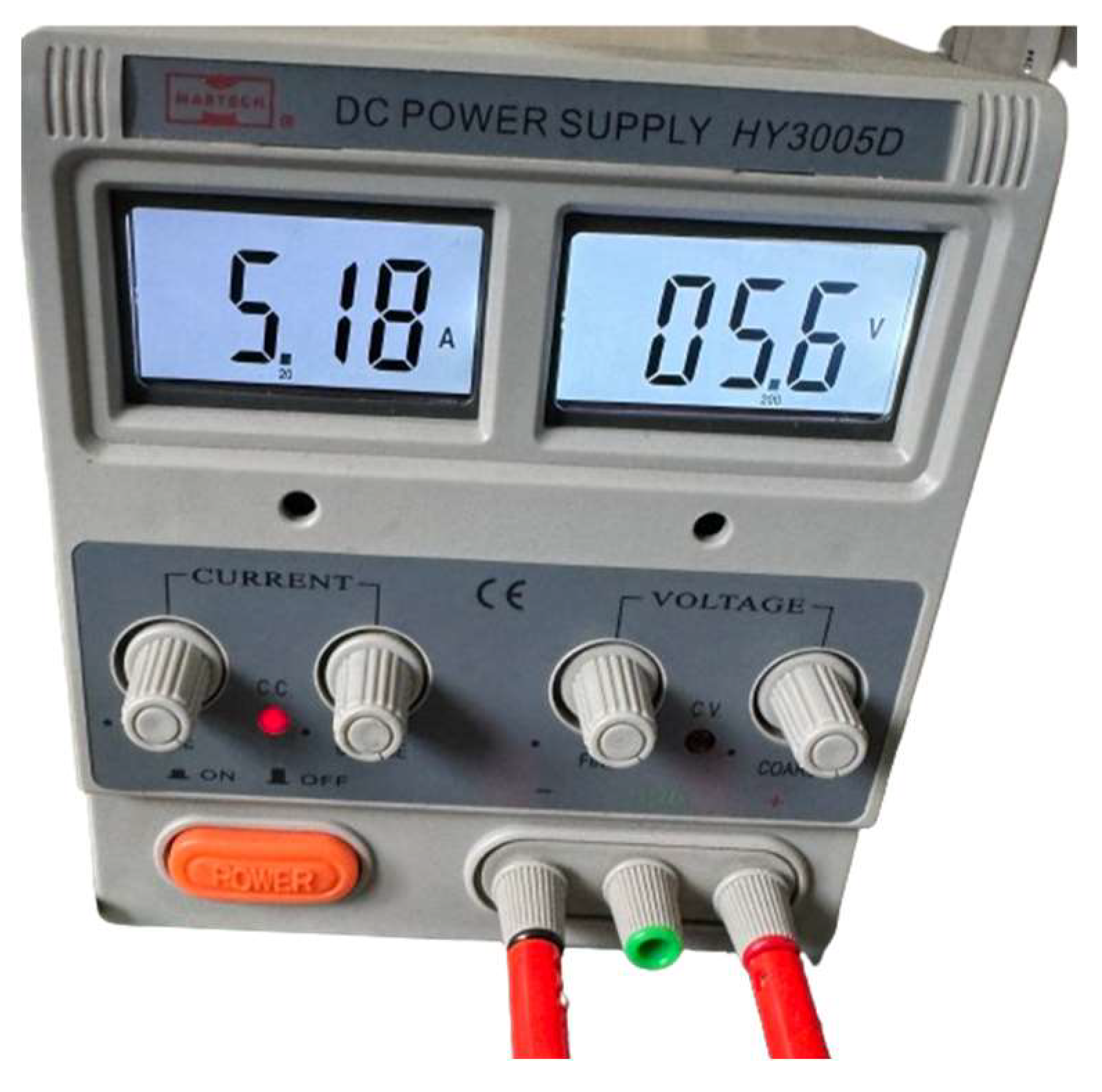

2.2. Proof-of-Concept Test Device and Other Tools

2.3. Experimental Setup

3. Results

3.1. Test Results with Kanthal Round Wire

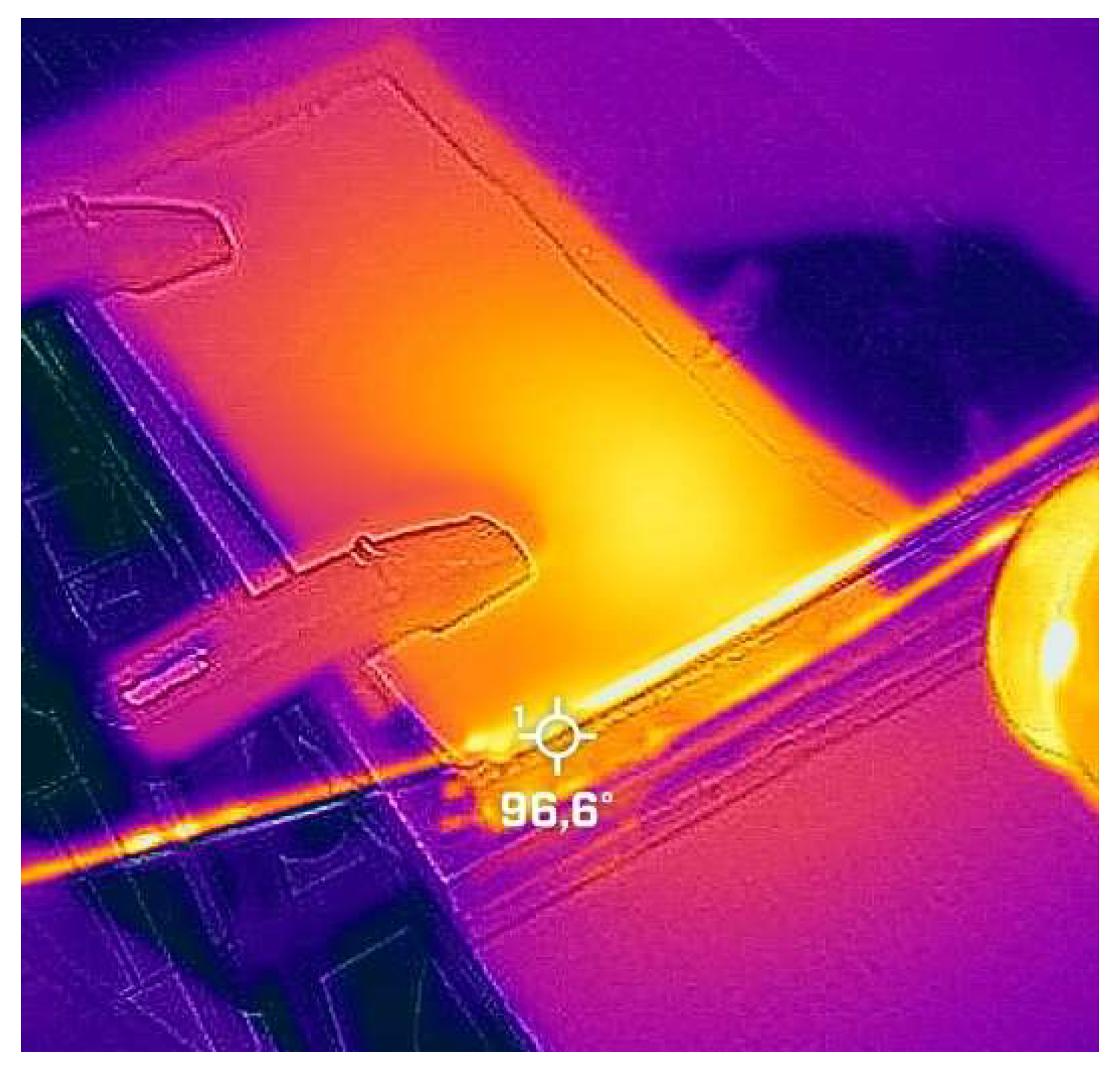

3.2. Test Results with Kanthal Wire with a Rectangular Cross-Section

4. Discussion

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EVA | Ethylene-vinyl acetate |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| GW | Gigawatts |

References

- Islam, I.; Jadin, M.S.; Al Mansur, A.; Kamari, N.A.M.; Jamal, T.; Lipu, M.S.H.; Azlan, M.N.M.; Sarker, M.R.; Shihavuddin, A.S.M. Techno-Economic and Carbon Emission Assessment of a Large-Scale Floating Solar PV System for Sustainable Energy Generation in Support of Malaysia’s Renewable Energy Roadmap. Energies 2023, 16, 4034. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-H.; Shin, W.J.; Wang, L.; Sun, W.-C.; Tao, M. Strategy and technology to recycle wafer-silicon solar modules. Sol. Energy 2017, 144, 22–31. [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.A.; Groesser, S.N. A Systematic Literature Review of the Solar Photovoltaic Value Chain for a Circular Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9615. [CrossRef]

- Sah, D.; Chitra; Lodhi, K.; Kant, C.; Srivastava, S.K.; Kumar, S. Extraction and Analysis of Recovered Silver and Silicon from Laboratory Grade Waste Solar Cells. Silicon 2022, 14, 9635–9642. [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Renewables 2022: Analysis and Forecast to 2027; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2023.

- Heath, G.A.; Silverman, T.J.; Kempe, M.; Deceglie, M.; Ravikumar, D.; Remo, T.; Cui, H.; Sinha, P.; Libby, C.; Shaw, S. Research and development priorities for silicon photovoltaic module recycling to support a circular economy. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 502–510. [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Renewable Energy Statistics; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2023.

- Ghosh, M.K.; Mansur, A.; Rifat, A.I.; Mollik, A.A.; Ghosh, A.K.; Soheb, M.; Islam, I.; Haq, M.A.U. The Prospect of Waste Management System for Solar Power Plants in Bangladesh: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th International Conference on Sustainable Technologies for Industry 5.0 (STI), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 9–10 December 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.; Park, J.; Seo, D.; Park, N. Sustainable System for Raw-Metal Recovery from Crystalline Silicon Solar Panels: From Noble-Metal Extraction to Lead Removal. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 4079–4083. [CrossRef]

- Akhter, M.; Al Mansur, A.; Islam, M.I.; Lipu, M.S.H.; Karim, T.F.; Abdolrasol, M.G.M.; Alghamdi, T.A.H. Sustainable Strategies for Crystalline Solar Cell Recycling: A Review on Recycling Techniques, Companies, and Environmental Impact Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5785. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Iyer-Raniga, U.; Trewick, S. Recycling Perspectives of Circular Business Models: A Review. Recycling 2022, 7, 79. [CrossRef]

- Spooren, J.; Binnemans, K.; Björkmalm, J.; Breemersch, K.; Dams, Y.; Folens, K.; González-Moya, M.; Horckmans, L.; Komnitsas, K.; Kurylak, W. Near-zero-waste processing of low-grade, complex primary ores and secondary raw materials in Europe: Technology development trends. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 160, 104919. [CrossRef]

- Gerold, E.; Antrekowitsch, H. Advancements and Challenges in Photovoltaic Cell Recycling: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2542. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-Y.; Hsiao, J.-C.; Du, C.-H. Recycling of materials from silicon base solar cell module. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 38th Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), Austin, TX, USA, 3–8 June 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 2355–2358. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-H.; Tao, M. A simple green process to recycle Si from crystalline-Si solar cells. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 42nd Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), New Orleans, LA, USA, 14–19 June 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Todorov, G.; Vasilev, H.; Kamberov, K.; Ivanov, Ts.; Sofronov, Y.; Concept and Virtual Prototyping of Cooling Module for Photovoltaic System. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Symposium on Environment-Friendly Energies and Applications (EFEA), Sofia, Bulgaria, 2021; pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-H.; Chen, W.-S.; Lee, C.-H.; Wu, J.-Y. Comprehensive Review of Crystalline Silicon Solar Panel Recycling: From Historical Context to Advanced Techniques. Sustainability 2024, 16, 60. [CrossRef]

- Savvilotidou, V.; Antoniou, A.; Gidarakos, E. Toxicity assessment and feasible recycling process for amorphous silicon and CIS waste photovoltaic panels. Waste Manag. 2017, 59, 394–402. [CrossRef]

- Dias, P.; Javimczik, S.; Benevit, M.; Veit, H.; Bernardes, A.M. Recycling WEEE: Extraction and concentration of silver from waste crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules. Waste Manag. 2016, 57, 220–225. [CrossRef]

- Latunussa, C.E.L.; Ardente, F.; Blengini, G.A.; Mancini, L. Life Cycle Assessment of an innovative recycling process for crystalline silicon photovoltaic panels. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 156, 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Pagnanelli, F.; Moscardini, E.; Granata, G.; Atia, T.A.; Altimari, P.; Havlik, T.; Toro, L. Physical and chemical treatment of end of life panels: An integrated automatic approach viable for different photovoltaic technologies. Waste Manag. 2017, 59, 422–431. [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Park, J.; Park, N. A method to recycle silicon wafer from end-of-life photovoltaic module and solar panels by using recycled silicon wafers. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 162, 38. [CrossRef]

- Granata, G.; Pagnanelli, F.; Moscardini, E.; Havlik, T.; Toro, L. Recycling of photovoltaic panels by physical operations. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2014, 123, 239–248. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-Y.; Hsiao, J.-C.; Du, C.-H. Recycling of materials from silicon base solar cell module. In Proceedings of the 2012 38th IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 3–8 June 2012. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, J. Dissolution of ethylene vinyl acetate in crystalline silicon PV modules using ultrasonic irradiation and organic solvent. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2012, 98, 317–322. [CrossRef]

- Tammaro, M.; Rimauro, J.; Fiandra, V.; Salluzzo, A. Thermal treatment of waste photovoltaic module for recovery and recycling: Experimental assessment of the presence of metals in the gas emissions and in the ashes. Renew. Energy 2015, 81, 103–112. [CrossRef]

- Chitra; Sah, D.; Lodhi, K.; Kant, C.; Saini, P.; Kumar, S. Structural composition and thermal stability of extracted EVA from silicon solar modules waste. Sol. Energy 2020, 211, 74–81. [CrossRef]

- Dias, P.; Schmidt, L.; Gomes, L.B.; Bettanin, A.; Veit, H.; Bernardes, A.M. Recycling waste crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules by electrostatic separation. J. Sustain. Metall. 2018, 4, 176–186. [CrossRef]

- Mulazzani, A.; Eleftheriadis, P.; Leva, S. Recycling c-Si PV Modules: A Review, a Proposed Energy Model and a Manufacturing Comparison. Energies 2022, 15, 8419. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.-w.; Born, M.; Wambach, K. Pyrolysis of EVA and its application in recycling of photovoltaic modules. J. Environ. Sci. 2004, 16, 889–893.

- Bombach, E.; Röver, I.; Müller, A.; Schlenker, S.; Wambach, K.; Kopecek, R.; Wefringhaus, E. Technical experience during thermal and chemical recycling of a 23 year old PV generator formerly installed on Pellworm island. In Proceedings of the 21st European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference, Dresden, Germany, 4–8 September 2006.

- Mapari, R.; Narkhede, S.; Navale, A.; Babrah, J. Automatic waste segregator and monitoring system. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Res. 2020, 10, 171. [CrossRef]

- Sangho, Ch.; Hyonsoo, K.; Youngkook, K. Solar panel recycling apparatus and method. Patent WO2020197231A1, filed 24 March 2020, and issued 1 October 2020.

- Young Kook, K. Apparatus for recycling solar cell module, Patent KR102154030B1, filed 16 April 2019, and issued 9 September 2020.

- Motoo, T.; Junichi, S.; Keiichiro, U. Solar battery module recycling method, Patent JP2015110201A, filed 6 December 2013, and issued 18 June 2015.

- Dunxin, L.; Yijun, L.; Yisheng, L.; Defeng, L.; Lu, L.; Ying, W. Method and device for disassembling and recycling TPT back plate, EVA (ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer)/battery piece and glass, Patent CN109530394B, filed 19 November 2018, and issued 8 October 2021.

- Tsushima, T; Ogasawara, Sh.; Kurihara, K.; Ibarada, N.; Nobuyuki, Ts. Solar battery module recycling method and solar battery module recycling device, Patent JP2018086651A, filed 7 December 2017, and issued 7 June 2018.

- Xinjuan, L; Guoyi, D.; Weidong, L.; Cuigu, W.; Zhijun, Ch.; Chao, M.; Beihai, Y.; Ying, L.; Mengmeng, W.; Yingye, L. Photovoltaic module recycling method and system, Patent CN110571306A, filed 12 September 2019, and issued 13 December 2019.

- Lu, Zh.; Han, L.; Yunfeng, M.; Chongzhen, M.; Ziqi, Y.; Shengguang, Zh.; Yinfeng, H.; Jianwen, Zh.; Mingyu, L.; Qian, L.; Zhansheng, Zh.; Jindou, H. Recovery method and device of complete glass photovoltaic module, Patent CN111790723A, filed 24 June 2024, and issued 20 October 2020.

- Jingyang, L.; Qiao, Q.; Yuwen, G.; Li, D. EVA heat treatment method of waste crystalline silicon solar cell module, Patent CN103978010A, filed 8 May 2014, and issued 13 August 2014.

- Kushiya, K. Recycling method of solar cell module, Patent JP5574750B2, filed 25 February 2010, and issued 20 August 2014.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).