Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

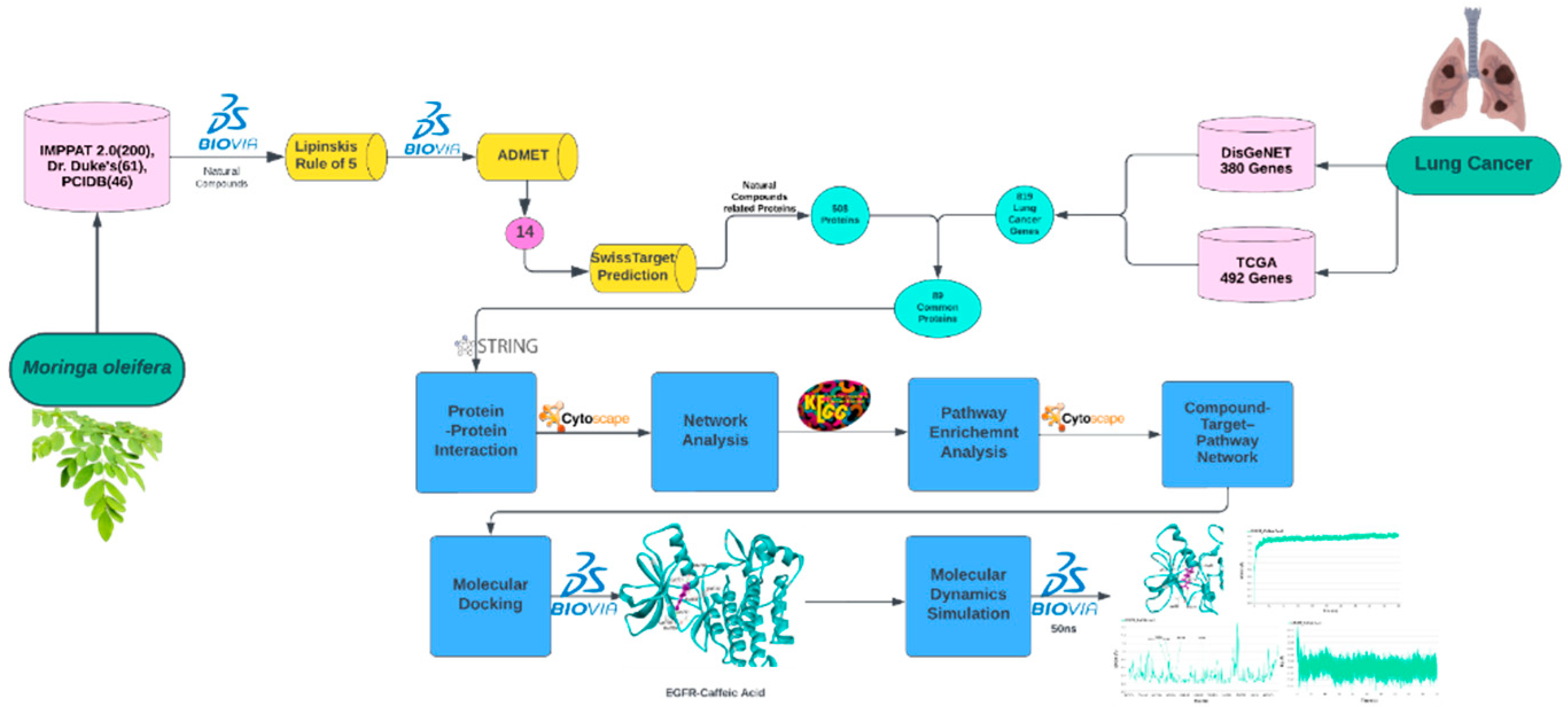

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Data Mining of M. oleifera Natural Constituents

2.3. Retrieval of Targets Related to Phytochemicals and Lung Cancer

2.4. Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network and Core Targets Identification

2.5. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

2.6. Compound-Targets–Pathways Network Construction

2.7. Molecular Docking

2.8. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3. Results and Discussion

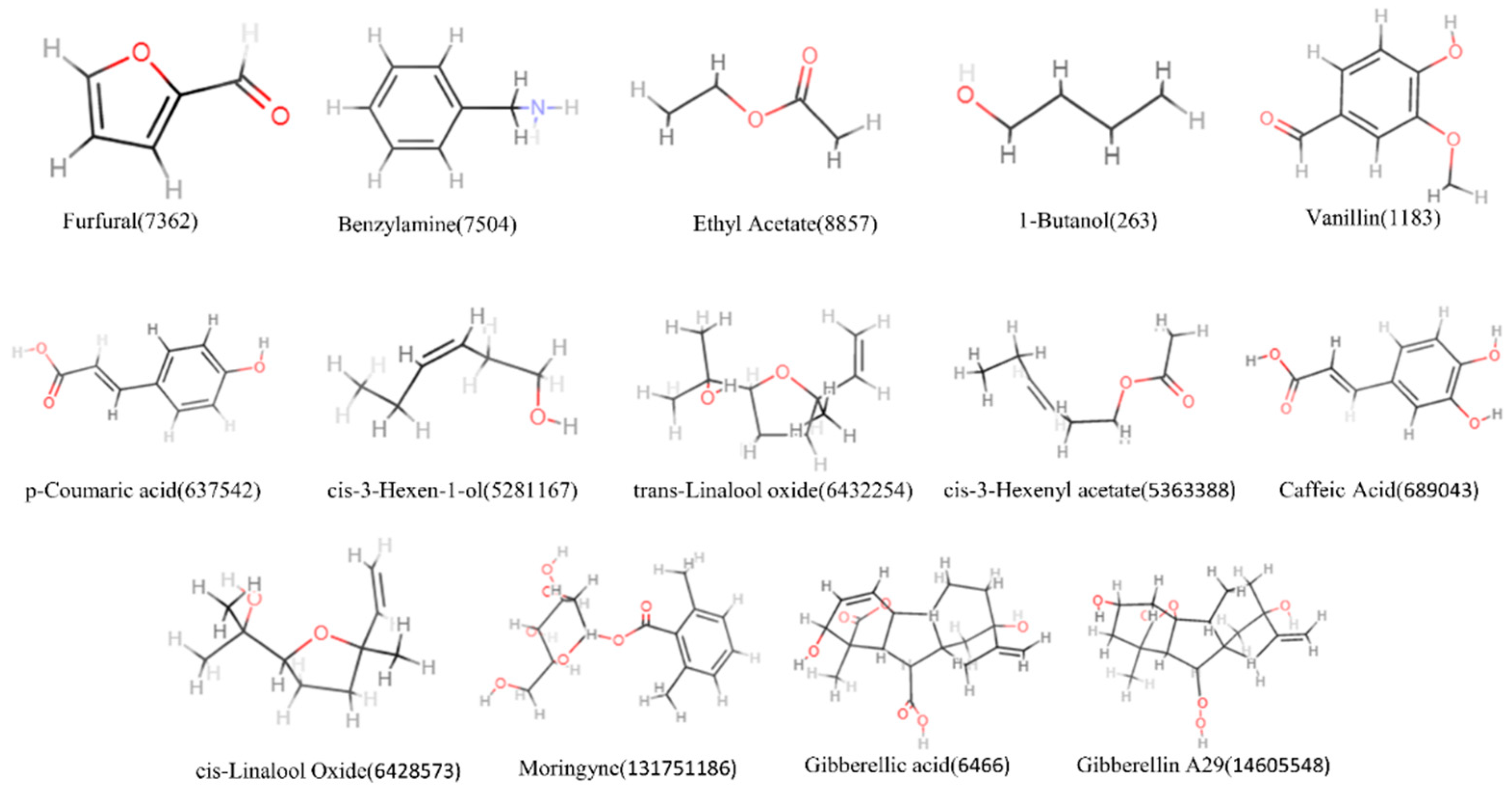

3.1. Screening of Active Components of M. oleifera

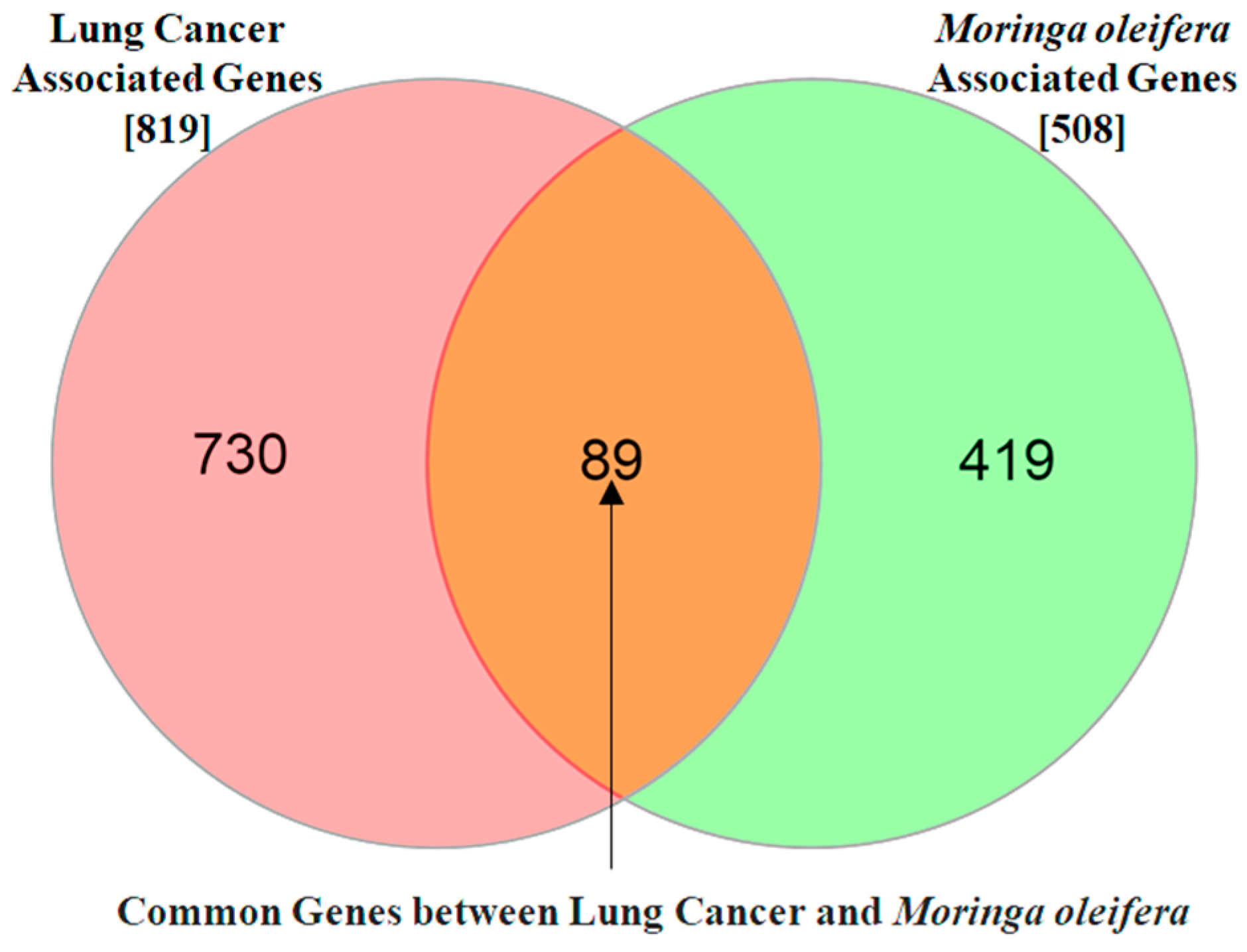

3.2. The Potential Targets for Natural Compounds of M. oleifera and Lung Cancer

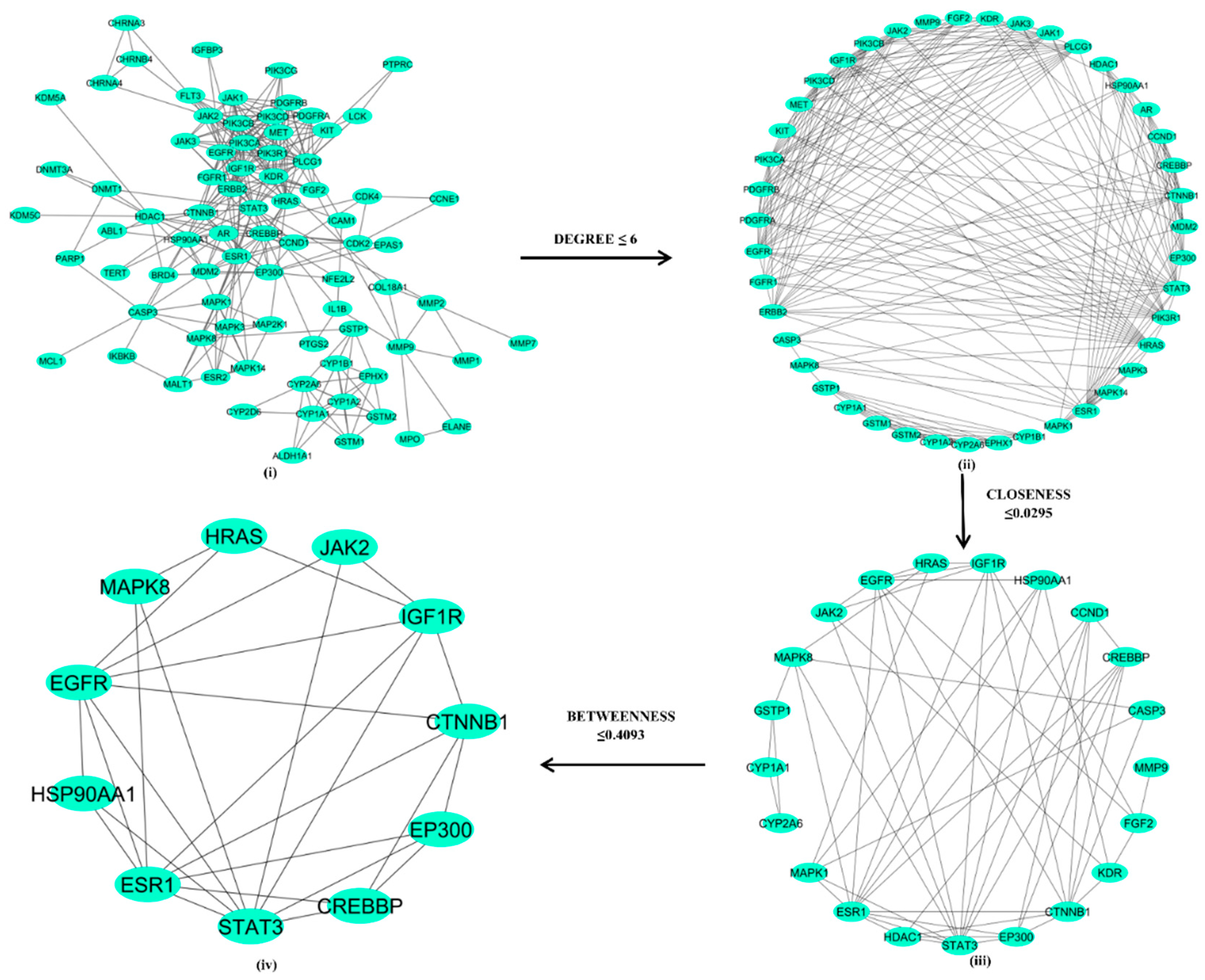

3.3. Protein-Protein Interaction and Network Analysis

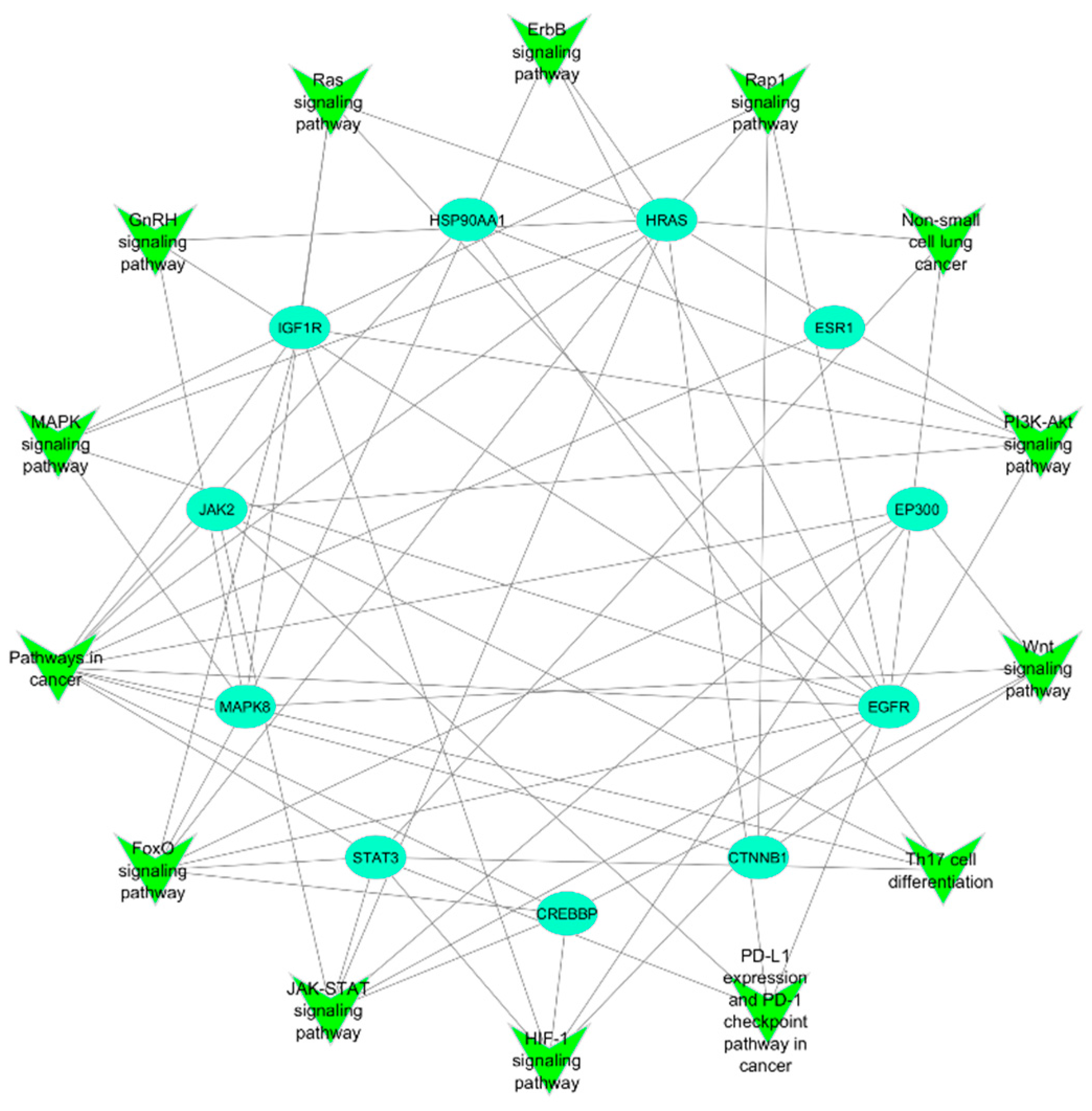

3.4. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis

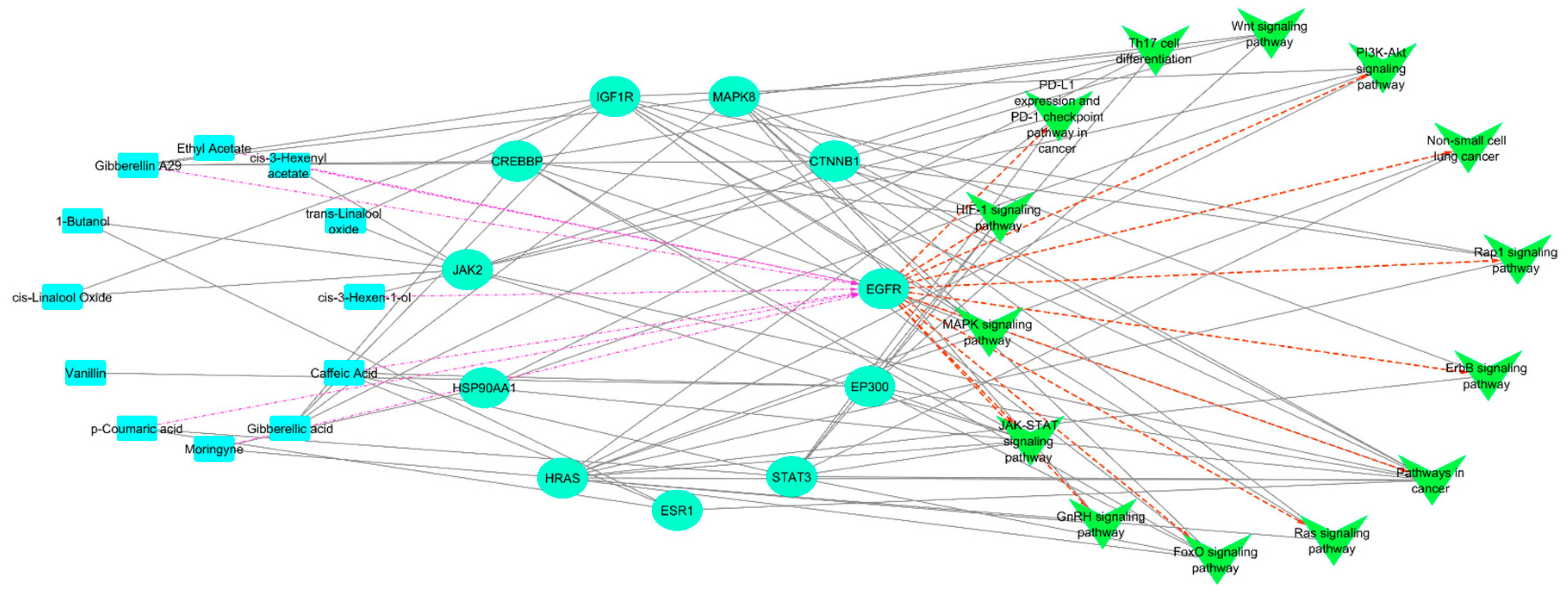

3.5. Compounds-Targets–Pathways Network Construction

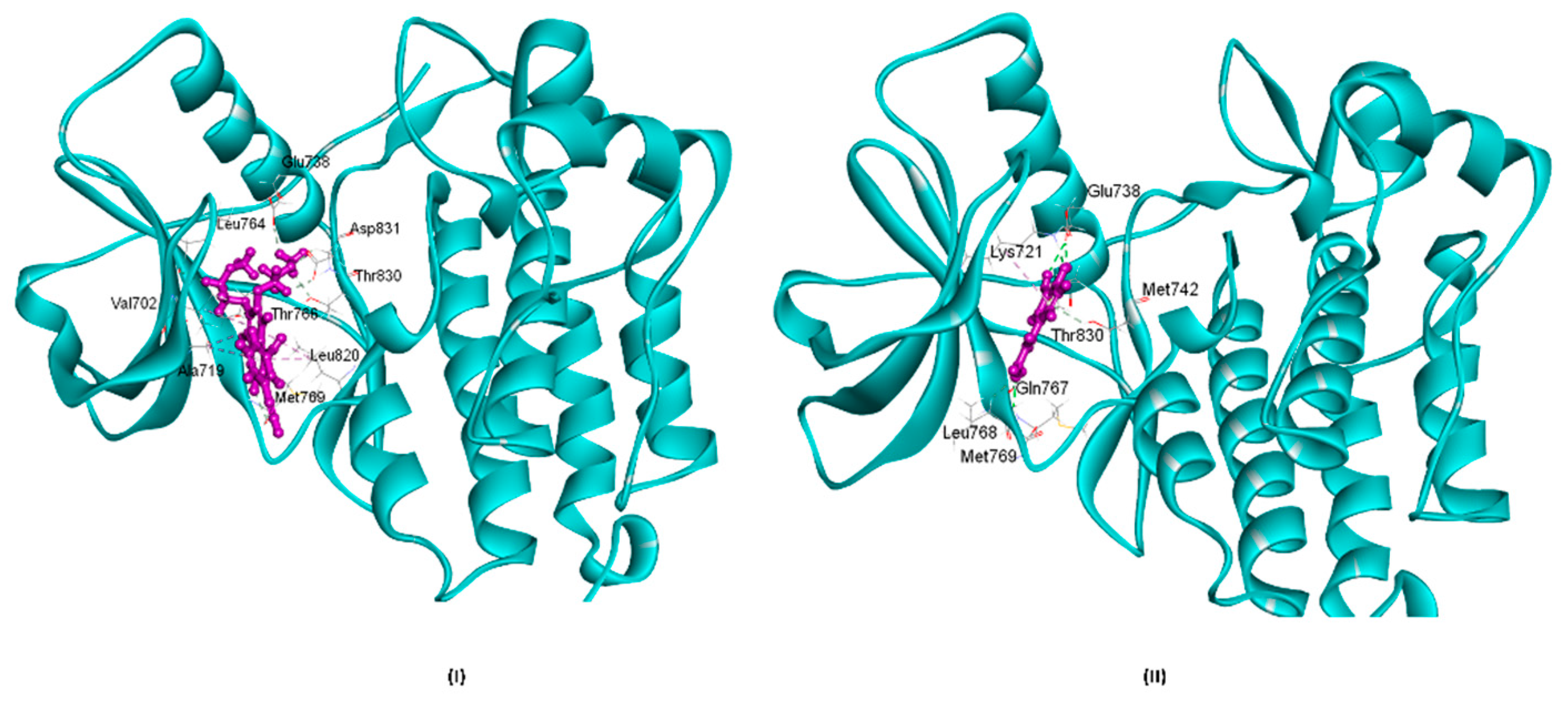

3.6. Molecular Docking

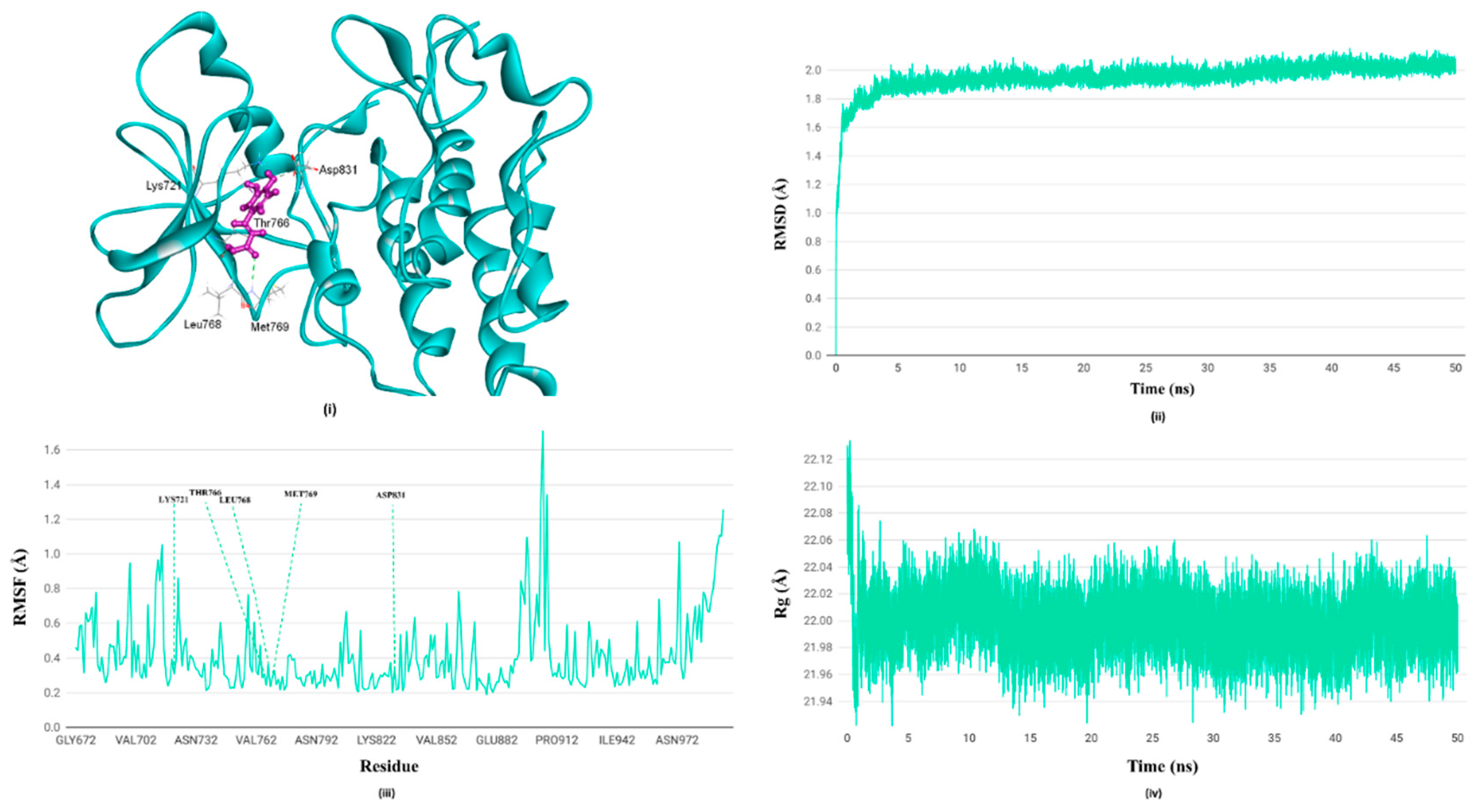

3.7. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

4. Discussion:

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Competing Interests

References

- Thandra, K.C.; Barsouk, A.; Saginala, K.; Aluru, J.S.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Contemp. Oncol. (Poznan, Poland) 2021, 25, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bade, B.C.; Dela Cruz, C.S. Lung Cancer 2020: Epidemiology, Etiology, and Prevention. Clin. Chest Med. 2020, 41, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirker, R. Conquering lung cancer: current status and prospects for the future. Pulmonology 2020, 26, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, K.; Hulbert, A.; Pasquinelli, M.; Feldman, L.E. Impact of CT screening in lung cancer: Scientific evidence and literature review. Semin. Oncol. 2022, 49, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.; Li, Y.; Xiong, L.; Wang, W.; Wu, M.; Yuan, T.; Yang, W.; Tian, C.; Miao, Z.; Wang, T.; et al. Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooti, W.; Servatyari, K.; Behzadifar, M.; Asadi-Samani, M.; Sadeghi, F.; Nouri, B.; Zare Marzouni, H. Effective Medicinal Plant in Cancer Treatment, Part 2: Review Study. J. Evid. Based. Complementary Altern. Med. 2017, 22, 982–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehelean, C.A.; Marcovici, I.; Soica, C.; Mioc, M.; Coricovac, D.; Iurciuc, S.; Cretu, O.M.; Pinzaru, I. Plant-Derived Anticancer Compounds as New Perspectives in Drug Discovery and Alternative Therapy. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.J.; Jahan, S.; Singh, R.; Saxena, J.; Ashraf, S.A.; Khan, A.; Choudhary, R.K.; Balakrishnan, S.; Badraoui, R.; Bardakci, F.; et al. Plants in Anticancer Drug Discovery: From Molecular Mechanism to Chemoprevention. Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Orhan, I.E.; Banach, M.; Rollinger, J.M.; Barreca, D.; Weckwerth, W.; Bauer, R.; Bayer, E.A.; et al. Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, F.; Deniz, S.; Sevim, D.; Chaachouay, N.; Zidane, L. Plant-Derived Natural Products: A Source for Drug Discovery and Development. Drugs Drug Candidates 2024, Vol. 3, Pages 184-207 2024, 3, 184–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzvetkov, N.T.; Kirilov, K.; Matin, M.; Atanasov, A.G. Natural product drug discovery and drug design: two approaches shaping new pharmaceutical development. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2024, 39, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, F.; Latif, S.; Ashraf, M.; Gilani, A.H. Moringa oleifera: A food plant with multiple medicinal uses. Phyther. Res. 2007, 21, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Pradheep, K.; Gupta, R.; Nayar, E.R.; Bhandari, D.C. “Drumstick tree” (Moringa oleifera Lam.): A multipurpose potential species in India. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2011, 58, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Z.; Islam, S.M.R.; Hossen, F.; Mahtab-Ul-Islam, K.; Hasan, M.R.; Karim, R. Moringa oleifera is a Prominent Source of Nutrients with Potential Health Benefits. Int. J. Food Sci. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhakmani, F.; Kumar, S.; Khan, S.A. Estimation of total phenolic content, in–vitro antioxidant and anti–inflammatory activity of flowers of Moringa oleifera. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkukwana, T.T.; Muchenje, V.; Pieterse, E.; Masika, P.J.; Mabusela, T.P.; Hoffman, L.C.; Dzama, K. Effect of Moringa oleifera leaf meal on growth performance, apparent digestibility, digestive organ size and carcass yield in broiler chickens. Livest. Sci. 2014, 161, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, P.; Kumar, S.; Riar, C.S.; Jindal, N.; Baniwal, P.; Guiné, R.P.F.; Correia, P.M.R.; Mehra, R.; Kumar, H. Recent Advances in Drumstick (Moringa oleifera) Leaves Bioactive Compounds: Composition, Health Benefits, Bioaccessibility, and Dietary Applications. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiloke, C.; Anand, K.; Gengan, R.M.; Chuturgoon, A.A. Moringa oleifera and their phytonanoparticles: Potential antiproliferative agents against cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 108, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, M.Z.; Kausar, F.; Hassan, M.; Javaid, S.; Malik, A. Anticancer activities of phenolic compounds from Moringa oleifera leaves: in vitro and in silico mechanistic study. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2021, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-Y.; Xu, Y.-M.; Y Lau, A.T.; Ferreira de Oliveira, P.; Ribeiro, D.; Ascenso, A.; Santos, C. Anti-Cancer and Medicinal Potentials of Moringa Isothiocyanate. Mol. 2021, Vol. 26, Page 7512 2021, 26, 7512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthy, S.; Varghese, S.; Sudarsan, S.; Muruganandhan, J.; Mushtaq, S. Moringa oleifera: Antioxidant, Anticancer, Anti-inflammatory, and Related Properties of Extracts in Cell Lines: A Review of Medicinal Effects, Phytochemistry, and Applications. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Gautam, D.N.S.; Sourav, S.; Sharma, R. Role of Moringa oleifera Lam. in cancer: Phytochemistry and pharmacological insights. Food Front. 2023, 4, 164–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Rabou, A.A.; Abdalla, A.M.; Ali, N.A.; Zoheir, K.M.A. Moringa oleifera Root Induces Cancer Apoptosis more Effectively than Leave Nanocomposites and Its Free Counterpart. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadresha, K.; Thakore, V.; Brahmbhatt, J.; Upadhyay, V.; Jain, N.; Rawal, R. Anticancer effect of Moringa oleifera leaves extract against lung cancer cell line via induction of apoptosis. Adv. Cancer Biol. - Metastasis 2022, 6, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Peng, L.J.; Yang, M.R.; Jiang, W.W.; Mao, J.Y.; Shi, C.Y.; Tian, Y.; Sheng, J. Alkaloid Extract of Moringa oleifera Lam. Exerts Antitumor Activity in Human Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer via Modulation of the JAK2/STAT3 Signaling Pathway. Evidence-based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Li, K.; Xu, W.; Li, R.; Xie, S.; Zhu, X. Prediction of the Mechanisms by Which Quercetin Enhances Cisplatin Action in Cervical Cancer: A Network Pharmacology Study and Experimental Validation. Front. Oncol. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lem, F.F.; Jiunn, D.; Lee, H.; Chee, F.T.; Chin, S.N.; Lin, K.M.; Yew, C.W. Network pharmacology approach to reveals therapeutic mech-anism of traditional plants formulation used by Malaysia in-digenous ethnics in coronaviruses infection. ChemRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, L.; Yang, L.; He, C.; He, Y.; Chen, L.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Li, P. Network pharmacology: a bright guiding light on the way to explore the personalized precise medication of traditional Chinese medicine. Chin. Med. 2023, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogoi, B.; Saikia, S.P. Virtual Screening and Network Pharmacology-Based Study to Explore the Pharmacological Mechanism of Clerodendrum Species for Anticancer Treatment. Evidence-based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: The rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Yang, H.; Cai, Y.; Sun, L.; Di, P.; Li, W.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y. ADMET-score – a comprehensive scoring function for evaluation of chemical drug-likeness. Medchemcomm 2019, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gfeller, D.; Grosdidier, A.; Wirth, M.; Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: a web server for target prediction of bioactive small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piñero, J.; Ramírez-Anguita, J.M.; Saüch-Pitarch, J.; Ronzano, F.; Centeno, E.; Sanz, F.; Furlong, L.I. The DisGeNET knowledge platform for disease genomics: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D845–D855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Bork, P.; et al. STRING v11: protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lu, P.; Zhao, F.; Sun, X.; Ma, W.; Tang, J.; Zhang, C.; Ji, H.; Wang, X. Uncovering the molecular mechanisms of Curcumae Rhizoma against myocardial fibrosis using network pharmacology and experimental validation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D353–D361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Meng, J.; Li, R.; Jiang, H.; Fu, L.; Xu, T.; Zhu, G.Y.; Zhang, W.; Gao, J.; Jiang, Z.H.; et al. Integrated network pharmacology analysis, molecular docking, LC-MS analysis and bioassays revealed the potential active ingredients and underlying mechanism of Scutellariae radix for COVID-19. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasab, R.R.; Mansourian, M.; Hassanzadeh, F.; Shahlaei, M. Exploring the interaction between epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase and some of the synthesized inhibitors using combination of in-silico and in-vitro cytotoxicity methods. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 13, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koska, J.; Spassov, V.Z.; Maynard, A.J.; Yan, L.; Austin, N.; Flook, P.K.; Venkatachalam, C.M. Fully automated molecular mechanics based induced fit protein - Ligand docking method. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2008, 48, 1965–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yang, Z.; Tong, K.; Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Yu, R.; Jiang, F.; Ji, Y. Homology modeling and molecular docking simulation of martentoxin as a specific inhibitor of the BK channel. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 71–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanraj, K.; Karthikeyan, B.S.; Vivek-Ananth, R.P.; Chand, R.P.B.; Aparna, S.R.; Mangalapandi, P.; Samal, A. IMPPAT: A curated database of Indian Medicinal Plants, Phytochemistry And Therapeutics. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lans, C.; van Asseldonk, T. Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, a Cornerstone in the Validation of Ethnoveterinary Medicinal Plants, as Demonstrated by Data on Pets in British Columbia. 2020, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali M 2019 PCIDB - PhytoChemical Interactions DataBase presentation by: DR. MOHAMMED ALI ABD EL-HAMMED ABD ALLAH Contact information Phone: Research gatea. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Mo, C.; Shi, W.; Meng, L.; Ai, J. Network Pharmacology Combined with Bioinformatics to Investigate the Mechanisms and Molecular Targets of Astragalus Radix-Panax notoginseng Herb Pair on Treating Diabetic Nephropathy. Evid. Based. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, W.; He, Y.; Zhong, H.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Y.; Cai, X.J.; Liu, L. qin Mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of Qingfeiyin in treating acute lung injury based on GEO datasets, network pharmacology and molecular docking. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rah, B.; Rather, R.A.; Bhat, G.R.; Baba, A.B.; Mushtaq, I.; Farooq, M.; Yousuf, T.; Dar, S.B.; Parveen, S.; Hassan, R.; et al. JAK/STAT Signaling: Molecular Targets, Therapeutic Opportunities, and Limitations of Targeted Inhibitions in Solid Malignancies. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimnezhad, M.; Natami, M.; Bakhtiari, G.H.; Tabnak, P.; Ebrahimnezhad, N.; Yousefi, B.; Majidinia, M. FOXO1, a tiny protein with intricate interactions: Promising therapeutic candidate in lung cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 169, 115900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.; Singhvi, G.; Dubey, S.K.; Gupta, G.; Dua, K. MAPK Pathway: a Potential Target for the Treatment of Non-small-cell Lung Carcinoma. Future Med. Chem. 2019, 11, 793–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, M.E.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.R. Targeting the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway for cancer therapy: from mechanism to clinical studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023 81 2023, 8, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tang, D.; Liu, H.; Luo, S.; Stinchcombe, T.E.; Glass, C.; Su, L.; Lin, L.; Christiani, D.C.; et al. Potentially functional variants of HBEGF and ITPR3 in GnRH signaling pathway genes predict survival of non-small cell lung cancer patients. Transl. Res. 2021, 233, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaei, M.J.; Razi, S.; Pourbagheri-Sigaroodi, A.; Bashash, D. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in lung cancer; oncogenic alterations, therapeutic opportunities, challenges, and a glance at the application of nanoparticles. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 18, 101364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Re, M.; Cucchiara, F.; Petrini, I.; Fogli, S.; Passaro, A.; Crucitta, S.; Attili, I.; De Marinis, F.; Chella, A.; Danesi, R. erbB in NSCLC as a molecular target: current evidences and future directions. ESMO Open 2020, 5, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Xing, C.; Deng, Y.; Ye, C.; Peng, H. HIF-1α signaling: Essential roles in tumorigenesis and implications in targeted therapies. Genes Dis. 2023, 11, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Wang, R.C.; Cheng, K.; Ring, B.Z.; Su, L. Roles of Rap1 signaling in tumor cell migration and invasion. Cancer Biol. Med. 2017, 14, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.W.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H.K.; Dong, J.M.; Xiao, Z.H.; He, X.; Guo, J.H.; Wang, R.Q.; Dai, B.; et al. Tumor immunotherapy resistance: Revealing the mechanism of PD-1 / PD-L1-mediated tumor immune escape. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 171, 116203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anvar, M.T.; Rashidan, K.; Arsam, N.; Rasouli-Saravani, A.; Yadegari, H.; Ahmadi, A.; Asgari, Z.; Vanan, A.G.; Ghorbaninezhad, F.; Tahmasebi, S. Th17 cell function in cancers: immunosuppressive agents or anti-tumor allies? Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, H.; Zhu, D. Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in lung cancer. Med. Drug Discov. 2022, 13, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, C.H.; Mengwasser, K.E.; Toms, A.V.; Woo, M.S.; Greulich, H.; Wong, K.K.; Meyerson, M.; Eck, M.J. The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2070–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanivel, S.; Yli-Harja, O.; Kandhavelu, M. Molecular interaction study of novel indoline derivatives with EGFR-kinase domain using multiple computational analysis. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 7545–7554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jura, N.; Endres, N.F.; Engel, K.; Deindl, S.; Das, R.; Lamers, M.H.; Wemmer, D.E.; Zhang, X.; Kuriyan, J. Mechanism for activation of the EGF receptor catalytic domain by the juxtamembrane segment. Cell 2009, 137, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fernandez, M.L.; Clarke, D.T.; Roberts, S.K.; Zanetti-Domingues, L.C.; Gervasio, F.L. Structure and Dynamics of the EGF Receptor as Revealed by Experiments and Simulations and Its Relevance to Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cells 2019, 8, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicidomini, G. Current Challenges and Future Advances in Lung Cancer: Genetics, Instrumental Diagnosis and Treatment. Cancers 2023, 15, 3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyewusi, H.A.; Wu, Y.S.; Safi, S.Z.; Wahab, R.A.; Hatta, M.H.M.; Batumalaie, K. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal the inhibitory mechanism of Withanolide A against α-glucosidase and α-amylase. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 6203–6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.P.; Singh, A.; Wolkenhauer, O.; Gupta, S.K. Regulatory Role of IL6 in Immune-Related Adverse Events during Checkpoint Inhibitor Treatment in Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasim, N.; Sandeep, I.S.; Mohanty, S. Plant-derived natural products for drug discovery: current approaches and prospects. Nucl. 2022, 65, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoker, D.G.; Reber, K.R.; Waltzman, L.S.; Ernst, C.; Hamilton, D.; Gawarecki, D.; Mermelstein, F.; McNicol, E.; Wright, C.; Carr, D.B. Analgesic efficacy and safety of morphine-chitosan nasal solution in patients with moderate to severe pain following orthopedic surgery. Pain Med. 2008, 9, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, D.M.Y.; Miller, K.; Neilan, B. Development of Taxol and Other Endophyte Produced Anti-Cancer Agents. Recent Pat. Anticancer. Drug Discov. 2008, 3, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, V.; Tandon, P.K.; Khatoon, S. Effect of Chromium on Antioxidant Potential of Catharanthus roseus Varieties and Production of Their Anticancer Alkaloids: Vincristine and Vinblastine. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 934182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wang, P.; Yang, C.; Huang, F.; Wu, H.; Shi, H.; Wu, X. Galangin Inhibits Gastric Cancer Growth Through Enhancing STAT3 Mediated ROS Production. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 646628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Dai, S.; Wang, C.; Fu, K.; Wu, R.; Zhao, X.; Yao, Y.; Li, Y. Luteolin as a potential hepatoprotective drug: Molecular mechanisms and treatment strategies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 167, 115464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yuan, G.; Pan, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, H. Network Pharmacology Studies on the Bioactive Compounds and Action Mechanisms of Natural Products for the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ya’u Ibrahim, Z.; Uzairu, A.; Shallangwa, G.; Abechi, S. Molecular docking studies, drug-likeness and in-silico ADMET prediction of some novel β-Amino alcohol grafted 1,4,5-trisubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles derivatives as elevators of p53 protein levels. Sci. African 2020, 10, e00570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L.; Chen, R.F.; Chen, J.Y.F.; Chu, Y.C.; Wang, H.M.; Chou, H.L.; Chang, W.C.; Fong, Y.; Chang, W.T.; Wu, C.Y.; et al. Protective Effect of Caffeic Acid on Paclitaxel Induced Anti-Proliferation and Apoptosis of Lung Cancer Cells Involves NF-κB Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cal, M.; Szakonyi, Z.; Pavlíková, N. Caffeic Acid and Diseases—Mechanisms of Action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.; Costa, M.; Ferreira, M.; Gameiro, P.; Fernandes, S.; Catarino, C.; Santos-Silva, A.; Paiva-Martins, F. Caffeic acid phenolipids in the protection of cell membranes from oxidative injuries. Interaction with the membrane phospholipid bilayer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 2021, 1863, 183727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.X.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.L.; Li, L.Z.; Xu, W.M.; Li, T. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester attenuates pro-inflammatory and fibrogenic phenotypes of LPS-stimulated hepatic stellate cells through the inhibition of NF-κB signaling. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 33, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudgal, J.; Basu Mallik, S.; Nampoothiri, M.; Kinra, M.; Hall, S.; Grant, G.D.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S.; Davey, A.K.; Rao, C.M.; Arora, D. Effect of coffee constituents, caffeine and caffeic acid on anxiety and lipopolysaccharide-induced sickness behavior in mice. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 64, 103638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Gholami, M.H.; Zabolian, A.; Saleki, H.; Farahani, M.V.; Hamzehlou, S.; Far, F.B.; Sharifzadeh, S.O.; Samarghandian, S.; Khan, H.; et al. Caffeic acid and its derivatives as potential modulators of oncogenic molecular pathways: New hope in the fight against cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 171, 105759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Ahmed, S.; Elasbali, A.M.; Adnan, M.; Alam, S.; Hassan, M.I.; Pasupuleti, V.R. Therapeutic Implications of Caffeic Acid in Cancer and Neurological Diseases. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 860508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secme, M.; Mutlu, D.; Elmas, L.; Arslan, S. Assessing effects of caffeic acid on cytotoxicity, apoptosis, invasion, GST enzyme activity, oxidant, antioxidant status and micro-RNA expressions in HCT116 colorectal cancer cells. South African J. Bot. 2023, 157, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, M.L.; Marrocco, I.; Yarden, Y. EGFR in Cancer: Signaling Mechanisms, Drugs, and Acquired Resistance. Cancers 2021, 13, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, P.T.; Vyse, S.; Huang, P.H. Rare epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 61, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, S.A.; Yu, H.; Choi, Y. La; Park, S.; Sun, J.M.; Lee, S.H.; Ahn, J.S.; Ahn, M.J.; Choi, D.H.; Kim, K.; et al. Trends in Survival Rates of Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer With Use of Molecular Testing and Targeted Therapy in Korea, 2010-2020. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e232002–e232002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Hasan, G.M.; Eldin, S.M.; Adnan, M.; Riyaz, M.B.; Islam, A.; Khan, I.; Hassan, M.I. Investigating regulated signaling pathways in therapeutic targeting of non-small cell lung carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingsworth, S.A.; Dror, R.O. Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron 2018, 99, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pathways in cancer | FoxO signaling pathway | JAK-STAT signaling pathway | HIF-1 signaling pathway | PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer | Th17 cell differentiation | Wnt signaling pathway | PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | Non-small cell lung cancer | Rap1 signaling pathway | ErbB signaling pathway | Ras signaling pathway | GnRH signaling pathway | MAPK signaling pathway | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| STAT3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| ESR1 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| MAPK8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| IGF1R | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| CTNNB1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| CREBBP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| HSP90AA1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| HRAS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| JAK2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| EP300 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).