Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

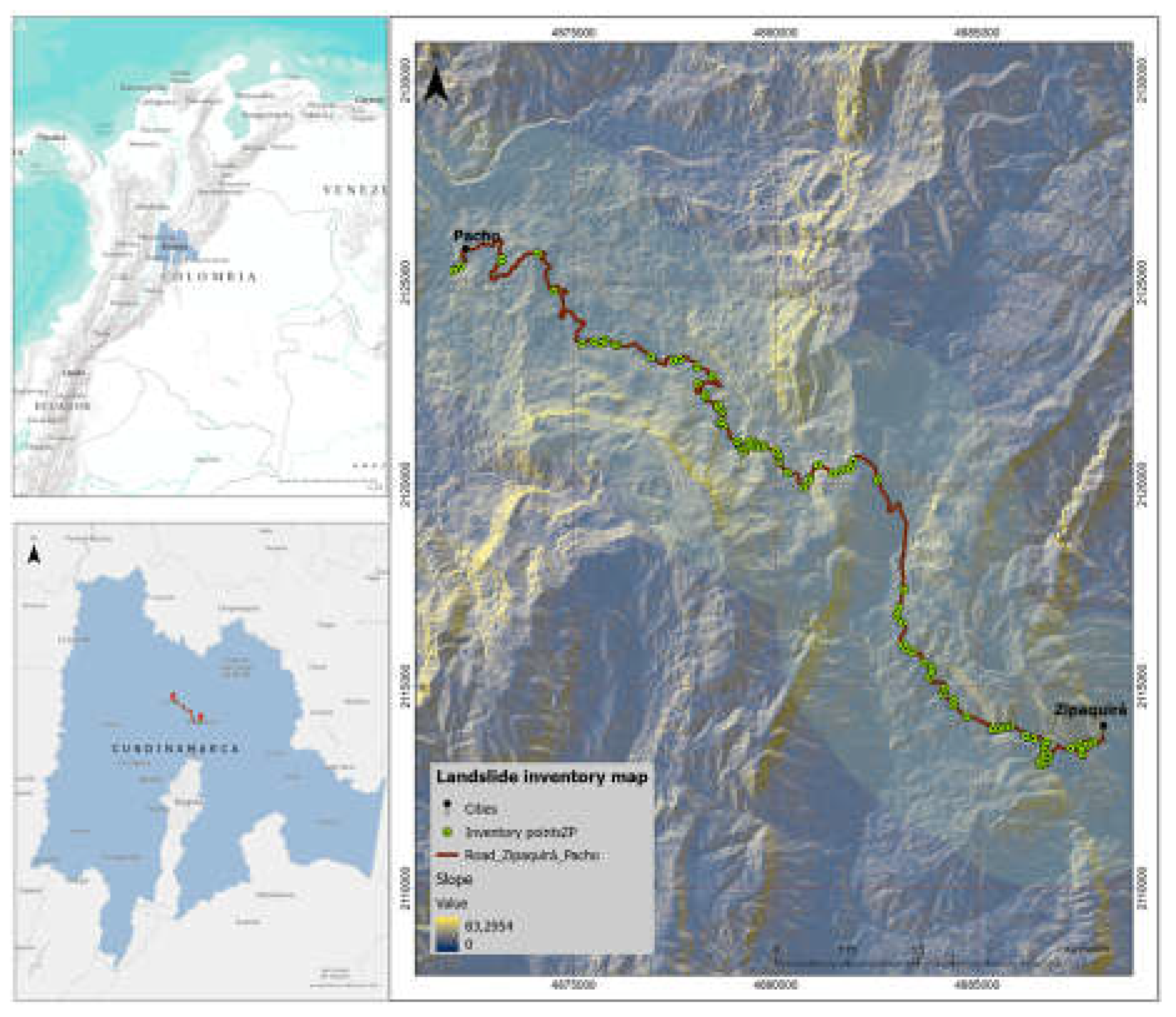

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Input Data

2.3. Landslide Inventory

2.4. Landslide inventory Mapping

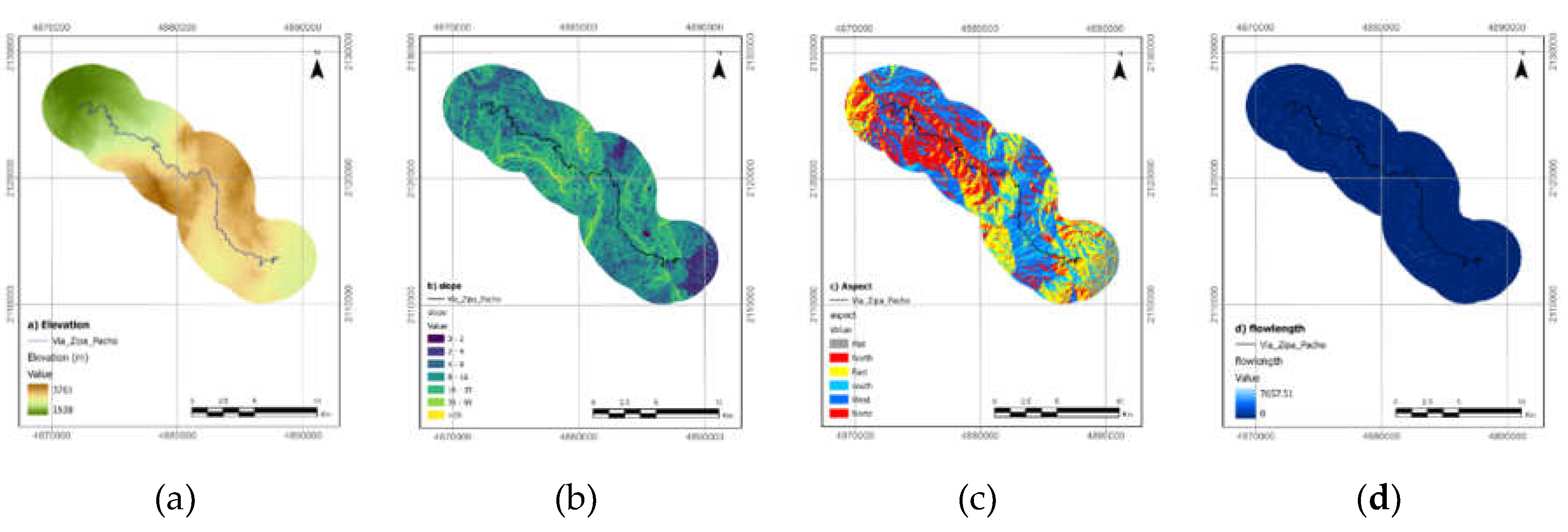

2.5. Causal Factors of Landslides

2.6. Raster Geodatabase

3. Results

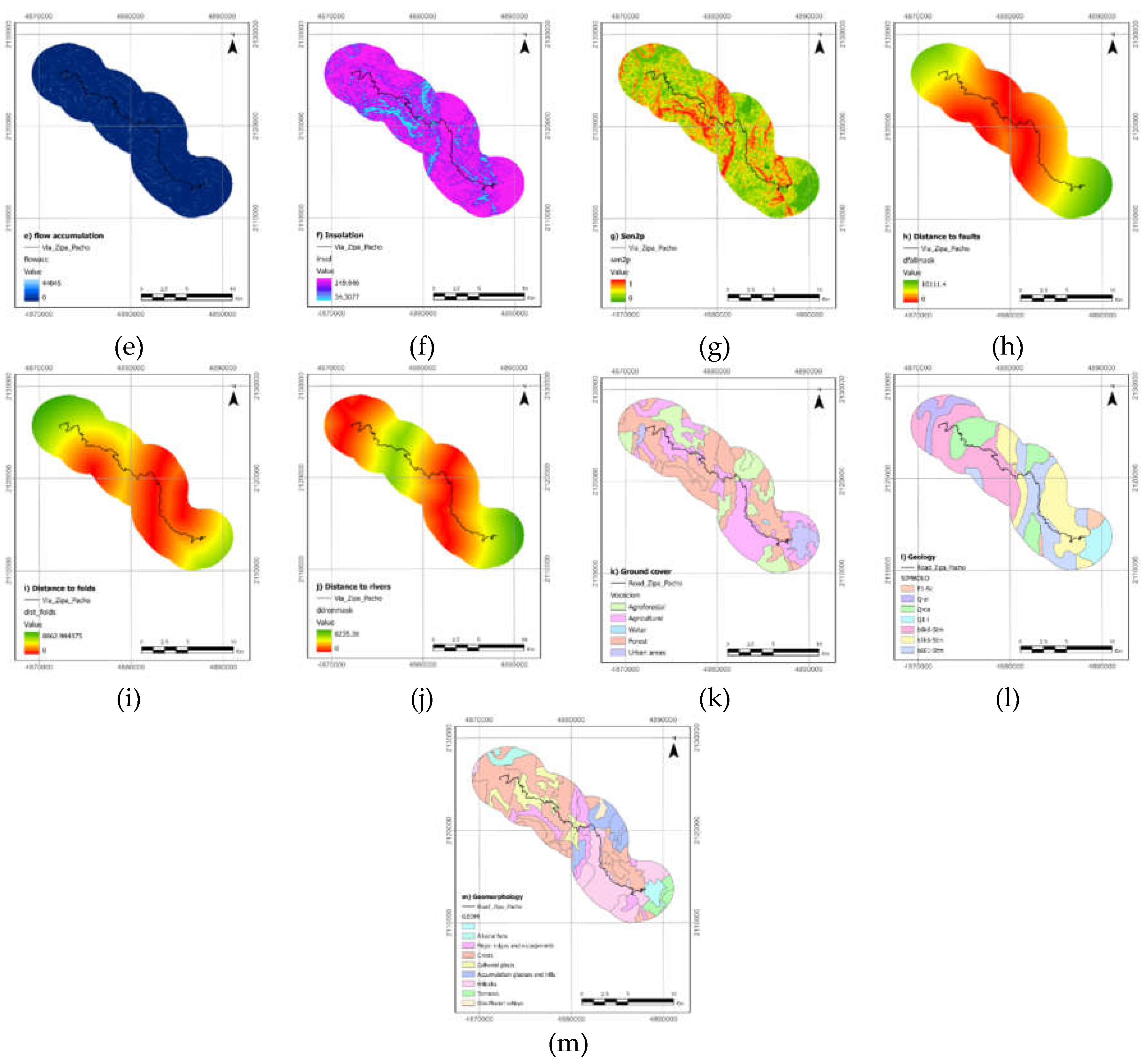

3.1. Landslide Suceptibility Zoning Map

3.2. Mitigation and Risk Management Strategies in Landslide Suceptibility Zones

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- F. C. Dai, C. F. Lee, and Y. Y. Ngai, ‘Landslide risk assessment and management: an overview’, Eng Geol, vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 65–87, Apr. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Hungr, R. Fell, R. Couture, and E. Erik, Landslide Risk Management. CRC Press, 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. Corominas et al., ‘Recommendations for the quantitative analysis of landslide risk’, Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Roccati, G. Paliaga, F. Luino, F. Faccini, and L. Turconi, ‘GIS-Based Landslide Susceptibility Mapping for Land Use Planning and Risk Assessment’, Land (Basel), vol. 10, no. 2, p. 162, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Rossi, F. Guzzetti, P. Reichenbach, A. C. Mondini, and S. Peruccacci, ‘Optimal landslide susceptibility zonation based on multiple forecasts’, Geomorphology, vol. 114, no. 3, pp. 129–142, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- F. Guzzetti, P. F. Guzzetti, P. Reichenbach, F. Ardizzone, M. Cardinali, and M. Galli, ‘Estimating the quality of landslide susceptibility models’, Geomorphology, vol. 81, no. 1–2, pp. 166–184, Nov. 2006. [CrossRef]

- IRPI – Istituto Di Ricerca per La Protezione Idrogeologica, "Landslide susceptibility models and maps," Available online: https://www.irpi.cnr.it/en/focus/landslide-susceptibility/, accessed May 23, 2024.

- P. Reichenbach, M. Rossi, B. D. Malamud, M. Mihir, and F. Guzzetti, ‘A review of statistically-based landslide susceptibility models’, Earth Sci Rev, vol. 180, pp. 60–91, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- A Brenning, “Spatial prediction models for landslide hazards: review, comparison and evaluation”, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., vol. 5, núm. 6, pp. 853–862, 2005.

- P. Reichenbach, M. Rossi, B. D. Malamud, M. Mihir, and F. Guzzetti, ‘A review of statistically-based landslide susceptibility models’, Earth Sci Rev, vol. 180, no. 2, pp. 60–91, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- USGS,– United States Geological Survey, "Landslide Hazards Program. What are landslides & how can they affect me?" Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/programs/landslide-hazards/what-a-landslide, accessed June 2, 2024.

- IDIGER – District Institute for Risk Management and Climate Change, "General Characterization of the Risk Scenario for Mass Movements in Bogotá," Available online: https://www.idiger.gov.co/rmovmasa, accessed April 2, 2024.

- NSTS, ‘Generalities about landslides. National Geological Service of El Salvador, Government of El Salvador.’ [Online]. Available: https://www.snet.gob.sv/Geologia/Deslizamientos/Info-basica/3-generalidades.htm#:~:text=Es la deformación que sufre,y la aparición de grietas.

- C. F. Barella, F. G. Sobreira, and J. L. Zêzere, ‘A comparative analysis of statistical landslide susceptibility mapping in the southeast region of Minas Gerais state, Brazil’, Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, vol. 78, no. 5, pp. 3205–3221, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Gaidzik and M. T. Ramírez-Herrera, ‘The importance of input data on landslide susceptibility mapping’, Sci Rep, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 19334, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Kanwal, S. Atif, and M. Shafiq, ‘GIS based landslide susceptibility mapping of northern areas of Pakistan, a case study of Shigar and Shyok Basins’, Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 348–366, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Cascini, ‘Applicability of landslide susceptibility and hazard zoning at different scales’, Eng Geol, vol. 102(3–4), 2008. [CrossRef]

- L. Ayalew and H. Yamagishi, ‘The application of GIS-based logistic regression for landslide susceptibility mapping in the Kakuda-Yahiko Mountains, Central Japan’, Geomorphology, vol. 65, no. 1–2, pp. 15–31, Feb. 2005. [CrossRef]

- L. Highland and P. Bobrowsky, ‘The landslide handbook – A guide to understanding landslides’, Reston, vol. Virginia, 2014. https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1325/pdf/C1325_508.pdf.

- J. Dou et al., ‘Optimization of Causative Factors for Landslide Susceptibility Evaluation Using Remote Sensing and GIS Data in Parts of Niigata, Japan’, PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 7, p. e0133262, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Costanzo, E. Rotigliano, C. Irigaray, J. D. Jiménez-Perálvarez, and J. Chacón, ‘Factors selection in landslide susceptibility modelling on large scale following the gis matrix method: application to the river Beiro basin (Spain)’, Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 327–340, Feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Dou, T. Oguchi, Y. S. Hayakawa, S. Uchiyama, H. Saito, and U. Paudel, ‘GIS-Based Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using a Certainty Factor Model and Its Validation in the Chuetsu Area, Central Japan’, in Landslide Science for a Safer Geoenvironment, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2014, pp. 419–424. [CrossRef]

- Addis, ‘GIS-Based Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Frequency Ratio and Shannon Entropy Models in Dejen District, Northwestern Ethiopia’, Journal of Engineering, vol. 2023, pp. 1–14, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Getachew and M. Meten, ‘Weights of evidence modeling for landslide susceptibility mapping of Kabi-Gebro locality, Gundomeskel area, Central Ethiopia’, Geoenvironmental Disasters, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 6, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Khan, M. Shafique, M. A. Khan, M. A. Bacha, S. U. Shah, and C. Calligaris, ‘Landslide susceptibility assessment using Frequency Ratio, a case study of northern Pakistan’, The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 11–24, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Neuhäuser and B. Terhorst, ‘Landslide susceptibility assessment using “weights-of-evidence” applied to a study area at the Jurassic escarpment (SW-Germany)’, Geomorphology, vol. 86, no. 1–2, pp. 12–24, Apr. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Londoño-Linares, Modelización de problemas ambientales en entornos urbanos: deslizamientos de tierra en ciudades andinas, Ph.D. dissertation, UPC, Institut Universitari de Recerca en Ciència i Tecnologies de la Sostenibilitat, 2016. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/2117/98123.

- F. Mengistu, K. V. Suryabhagavan, T. K. Raghuvanshi, and E. Lewi, ‘Landslide Hazard Zonation and Slope Instability Assessment using Optical and InSAR Data: A Case Study from Gidole Town and its Surrounding Areas, Southern Ethiopia’, Remote Sensing of Land, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–14, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Omar, B. K. Huat, Z. M. Yusoff, M. Safaei, and V. Ghiasi, "Deterministic rainfall-induced landslide approaches, advantages and limitations," Electronic Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, vol. 16, no. U, pp. 1619–1650, 2011. ISSN: 1089-3032.

- L. Shano, T. K. Raghuvanshi, and M. Meten, ‘Landslide susceptibility evaluation and hazard zonation techniques – a review’, Geoenvironmental Disasters, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 18, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Dahal, S. Hasegawa, A. Nonomura, M. Yamanaka, T. Masuda, and K. Nishino, ‘GIS-based weights-of-evidence modelling of rainfall-induced landslides in small catchments for landslide susceptibility mapping’, Environmental Geology, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 311–324, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- P. Goyes-Peñafiel and A. Hernandez-Rojas, ‘Landslide susceptibility index based on the integration of logistic regression and weights of evidence: A case study in Popayan, Colombia’, Eng Geol, vol. 280, p. 105958, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cao, X. Wei, W. Fan, Y. Nan, W. Xiong, and S. Zhang, ‘Landslide susceptibility assessment using the Weight of Evidence method: A case study in Xunyang area, China’, PLoS One, vol. 16, no. 1, p. e0245668, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Rahman, A. U. Rahman, A. S. Bacha, S. Mahmood, M. F. U. Moazzam, and B. G. Lee, ‘Assessment of Landslide Susceptibility using Weight of Evidence and Frequency Ratio Model in Shahpur Valley, Eastern Hindu Kush’, Jul. 08, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, ‘GIS-based landslide susceptibility mapping using analytical hierarchy process and bivariate statistics in Ardesen (Turkey): Comparisons of results and confirmations’, Catena (Amst), vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- M.-L. Lin and C.-C. Tung, ‘A GIS-based potential analysis of the landslides induced by the Chi-Chi earthquake’, Eng Geol, vol. 71, no. 1–2, pp. 63–77, Jan. 2004. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Zêzere et al., ‘Integration of spatial and temporal data for the definition of different landslide hazard scenarios in the area north of Lisbon (Portugal)’, Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 133–146, Mar. 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. Jade and S. Sarkar, ‘Statistical models for slope instability classification’, Eng Geol, vol. 36, no. 1–2, pp. 91–98, Nov. 1993. [CrossRef]

- L. Yu, Y. Wang, and B. Pradhan, ‘Enhancing landslide susceptibility mapping incorporating landslide typology via stacking ensemble machine learning in Three Gorges Reservoir, China’, Geoscience Frontiers, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 101802, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Hou, G. Wu, and S. Zhang, "Assessment of landslide susceptibility in the Jinsha River gorge section based on the information method," Sichuan Arch., vol. 39, pp. 147–150, 2019.

- J. Zhang, J. Qian, Y. Lu, X. Li, and Z. Song, ‘Study on Landslide Susceptibility Based on Multi-Model Coupling: A Case Study of Sichuan Province, China’, Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 16, p. 6803, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Laltanpuia, ‘Printed in India Bivariate statistical models for Landslide susceptibility mapping at local scale in the Aizawl municipal area, Mizoram, India.’, 2024.

- P. N. Flentje, A. Miner, G. Whitt, and R. Fell, "Guidelines for landslide susceptibility," Hazard and Risk Zoning for Land Use Planning, vol. 42, no. 1, 2007.

- P. K. Rai, K. C. Mohan, and V. K. Kumra, ‘Landslide hazard and its mapping using remte sensing and GIS’, 2014. [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:28488330.

- Wubalem, ‘Landslide susceptibility mapping using statistical methods in Uatzau catchment area, northwestern Ethiopia’, Geoenvironmental Disasters, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 1, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Castro-Venegas, E. Jaque, J. Quezada, J. L. Palma, and A. Fernández, ‘Multi-source landslide inventories for susceptibility assessment: a case study in the Concepción Metropolitan Area, Chile’, Front Earth Sci (Lausanne), vol. 13, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wubalem and M. Meten, ‘Landslide susceptibility mapping using information value and logistic regression models in Goncha Siso Eneses area, northwestern Ethiopia’, SN Appl Sci, vol. 2, no. 5, p. 807, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Shahabi and M. Hashim, ‘Landslide susceptibility mapping using GIS-based statistical models and Remote sensing data in tropical environment’, Sci Rep, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 9899, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Shahabi, S. Khezri, B. Bin Ahmad, and M. Hashim, ‘RETRACTED: Landslide susceptibility mapping at central Zab basin, Iran: A comparison between analytical hierarchy process, frequency ratio and logistic regression models’, Catena (Amst), vol. 115, pp. 55–70, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. Yesilnacar and T. Topal, ‘Landslide susceptibility mapping: A comparison of logistic regression and neural networks methods in a medium scale study, Hendek region (Turkey)’, Eng Geol, vol. 79, no. 3–4, pp. 251–266, Jul. 2005. [CrossRef]

| Descriptors | Frequency | Description |

| Very low | Rare | The event is conceivable, but only under exceptional circumstances. |

| Low | Unlikely | The event might occur under very adverse circumstances. |

| Moderate | Possible | The event could occur under adverse conditions. |

| High | Likely | The event will probably occur under adverse conditions. |

| Very high | Almost certain | The event is expected to occur. |

| Causal factors | Sub-clases |

| Elevation (m) | 1538 – 1854; 1855 – 2172; 2173 – 2490; 2491 – 2807; 2808 – 3125; 3126 – 3443; 3444 - 3761 |

| Slope (degree) | 0 – 2; 2 – 4; 4 – 8; 8 – 16, 16 – 35; 35 – 55; 55 – 90 |

| Aspect (degree) | -1 – 0; 1 – 45; 45 – 135; 135 – 225; 225 – 315; 315 - 360 |

| Flow length | 0 – 694; 694 – 1090; 1090 – 1459; 1459 – 1884; 1884 – 2365; 2365 – 3084; 3084 – 7657 |

| Flow accumalate | 0 – 1009; 1009 – 2030; 2030 – 3135; 3135 – 4587; 4587 – 6638; 6638 – 10389; 10389 - 44045 |

| Insolation | 34.30 - 59.61; 59.62 - 75.53; 75.54 - 90.61; 90.62 - 105.53; 105.54 - 120.38; 120.39 - 135.15; 135.16 - 149.84 |

| Sen2P(slope) | 0 - 0.14; 0.15 - 0.28; 0.29 - 0.42; 0.43 - 0.57; 0.58 - 0.71; 0.72 - 0.85; 0.86 - 1 |

| Distance to faults | 0 – 1580; 1581 – 3005; 3006 – 4428, 4429 – 5850; 5851 – 7270; 7271 – 8689; 8690 - 10111 |

| Distance to rivers | 0 – 1308; 1309 – 2466; 2467 – 3623; 3624 – 4778; 4779 – 5932; 5933 – 7084; 7085 - 8235 |

| Distance to folds | 0 – 1399; 1400 – 2646; 2647 – 3892; 3893 – 5136; 5137 – 6379; 6380 – 7621; 7622 - 8862 |

| Ground cover | Agricultural; Agroforestry; Water body; Forest; Urban areas |

| Geology | b6k6-Stm; E1-Sc; k1k6-Stm; k6E1-Stm; Q-al; Q-ca; Q1-l |

| Geomorphology | Alluvial fans; Major ridges and scarps; Crestones, Colluvial glacis; Accumulation glacis and hills; Hills; Terraces; Glacifluvial valleys |

| Type of causal factor | Sub-classes | Number of pixels of each sub-class | Number pixels of landslides within sub-cl | Wc | IV |

| Elevation (m) | 1538 - 1854 | 75882 | 3 | -0.873 | -0.832 |

| 1855 - 2172 | 140394 | 4 | -1,254 | -1,160 | |

| 2173 - 2490 | 99974 | 8 | -0.139 | -0.127 | |

| 2491 - 2807 | 209604 | 19 | -0.003 | -0.002 | |

| 2808 - 3125 | 274427 | 61 | 1,538 | 0.895 | |

| 3126 - 3443 | 265962 | 6 | -1,605 | -1,393 | |

| 3444 - 3761 | 45498 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Slope (degree) | 0 - 2 | 31924 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 - 4 | 67998 | 4 | -0.462 | -0.439 | |

| 4 - 8 | 209916 | 5 | -1,502 | -1,343 | |

| 8 - 16 | 407336 | 28 | -0.417 | -0.283 | |

| 16 - 35 | 341817 | 59 | 1,146 | 0.638 | |

| 35 - 55 | 44575 | 5 | 0.216 | 0.207 | |

| 55 - 90 | 3676 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Aspect (degree) | -1 - 0 | 24789 | 1 | -0.829 | -0.816 |

| 1 - 45 | 140054 | 19 | 0.47 | 0.397 | |

| 45 - 135 | 269212 | 24 | -0.03 | -0.023 | |

| 135 - 225 | 199220 | 16 | -0.153 | -0.127 | |

| 225 - 315 | 327296 | 26 | -0.191 | -0.138 | |

| 315 - 360 | 146671 | 15 | 0.133 | 0.114 | |

| Flow length | 0 - 694 | 1088549 | 99 | 0.053 | 0.001 |

| 694 - 1090 | 11726 | 2 | 0.639 | 0.63 | |

| 1090 - 1459 | 4575 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1459 - 1884 | 2720 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1884 - 2365 | 1647 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2365 - 3084 | 1312 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3084 - 7657 | 1212 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Flow accumalate | 0 - 1009 | 1097929 | 100 | 0.23 | 0.003 |

| 1009 - 2030 | 5601 | 1 | 0.681 | 0.676 | |

| 2030 - 3135 | 2875 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3135 - 4587 | 1752 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4587 - 6638 | 1364 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6638 - 10389 | 1165 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10389 - 44045 | 1055 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Insolation | 34.30 - 59.61 | 149 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 59.62 - 75.53 | 412 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 75.54 - 90.61 | 966 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 90.62 - 105.53 | 2340 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 105.54 - 120.38 | 9946 | 4 | 1,513 | 1,482 | |

| 120.39 - 135.15 | 52247 | 6 | 0.241 | 0.228 | |

| 135.16 - 149.84 | 1039101 | 91 | -0.547 | -0.043 | |

| Sen2P(slope) | 0 - 0.14 | 123382 | 4 | -1,112 | -1,034 |

| 0.15 - 0.28 | 214813 | 6 | -1,338 | -1,184 | |

| 0.29 - 0.42 | 224851 | 13 | -0.545 | -0.456 | |

| 0.43 - 0.57 | 212737 | 21 | 0.099 | 0.079 | |

| 0.58 - 0.71 | 141337 | 28 | 0.964 | 0.776 | |

| 0.72 - 0.85 | 100446 | 21 | 0.968 | 0.829 | |

| 0.86 - 1 | 89676 | 8 | -0.024 | -0.022 | |

| Distance to faults | 0 - 1580 | 340004 | 43 | 0.52 | 0.331 |

| 1581 - 3005 | 223550 | 20 | -0.019 | -0.015 | |

| 3006 - 4428 | 180219 | 4 | -1,546 | -1,409 | |

| 4429 - 5850 | 129473 | 21 | 0.689 | 0.58 | |

| 5851 - 7270 | 120866 | 13 | 0.192 | 0.169 | |

| 7271 - 8689 | 81404 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8690 - 10111 | 36225 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Distance to rivers | 0 - 1308 | 325679 | 17 | -0.717 | -0.554 |

| 1309 - 2466 | 220204 | 17 | -0.199 | -0.163 | |

| 2467 - 3623 | 179049 | 26 | 0.591 | 0.469 | |

| 3624 - 4778 | 159248 | 33 | 1,066 | 0.825 | |

| 4779 - 5932 | 150536 | 8 | -0.599 | -0.536 | |

| 5933 - 7084 | 49427 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7085 - 8235 | 27598 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Distance to folds | 0 - 1399 | 305264 | 14 | -0.855 | -0.684 |

| 1400 - 2646 | 237674 | 40 | 0.88 | 0.617 | |

| 2647 - 3892 | 203342 | 41 | 1,116 | 0.797 | |

| 3893 - 5136 | 149910 | 1 | -2,746 | -2,611 | |

| 5137 - 6379 | 114503 | 5 | -0.791 | -0.733 | |

| 6380 - 7621 | 62747 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7622 - 8862 | 38301 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ground cover | Agricultural | 348496 | 50 | 0.764 | 0.457 |

| Agroforestry | 214415 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Water body | 1856 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Forest | 485805 | 48 | 0.155 | 0.084 | |

| Urban areas | 61272 | 3 | -0.645 | -0.618 | |

| Geology | b6k6-Stm | 326957 | 37 | 0.328 | 0.22 |

| E1-Sc | 25779 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| k1k6-Stm | 265802 | 31 | 0.343 | 0.25 | |

| k6E1-Stm | 205836 | 22 | 0.204 | 0.163 | |

| Q-al | 62265 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Q-ca | 160865 | 11 | -0.325 | -0.284 | |

| Q1-l | 64340 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Geomorphology | Alluvial fans | 30327 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Major ridges and scarps | 114231 | 12 | 0.163 | 0 | |

| Crestones | 455026 | 39 | -0.097 | 0.145 | |

| Colluvial glacis | 110723 | 17 | 0.604 | -0.058 | |

| Accumulation glacis and hills | 94088 | 0 | 0 | 0.525 | |

| Hilllocks | 233719 | 33 | 0.601 | 0 | |

| Terraces | 35336 | 0 | 0 | 0.441 | |

| Glacifluvial valleys | 10994 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 27400 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Susceptibility classes | Descriptor | IV | WOE | Description | ||||

| # of pixels in each class | % area coverage | # of events in each category | # of pixels in each class | % area coverage | # of events in each category | |||

| Very low | Rare | 116.902 | 10,58 | 1 | 222.183 | 20,11 | 1 | Areas of alluvial fans and guadua formations that generally have slopes of less than 4°, as well as areas of limestone and chert with low slopes. The urban areas located in the flat part of the sector |

| Low | Unlikely | 220.464 | 19,95 | 0 | 225.503 | 20,41 | 4 | Areas of alluvial fans and Guaduas formation that generally have slopes of less than 8°, as well as areas of limestone and chert with low slopes. The urban areas are located in the flat part of the sector. |

| Moderate | Possible | 280.165 | 25,36 | 10 | 222.652 | 20,15 | 8 | Areas of alluvial fans and Guaduas formation that generally have slopes ranging from 8° to 16°. |

| High | Likely | 293.311 | 26,55 | 25 | 217.828 | 19,71 | 22 | Alluvial fans and colluvial deposits with slopes oriented to the north, covered by agriculture, claystones, shales, and limestones from the Guaduas formation. The slopes range from 16° to 55°. |

| Very hihg | Almost certain | 194.099 | 17,57 | 65 | 216.775 | 19,62 | 66 | Claystones, shales, and limestones from the Guaduas formation, with slopes between 8° and 35° and north-facing slopes. |

| Total pixel | 1.104.941 | 100 | 101 | 1.104.941 | 100 | 101 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).