1. Introduction

As the influence of Artificial Intelligence (AI) expands exponentially, so does the necessity for systems to be transparent, understandable, and above all, explainable [

1]. This is further motivated by the untrustworthiness at the premises of Large Language Models (LLMs), which were not originally intended to provide reasoning mechanisms: as a result, when the system is asked about concepts upon which it was not originally trained, it tends to invent misleading information [

2]. This is inherently due to the probabilistic reasoning embedded within the model [

3] not accounting for inherent semantic contradiction implicitly derivable from the data through explicit rule-based approaches [

4,

5]. They do not consider reasoning by contradiction probabilistically with facts given as a conjunction of elements leads to iner unlikely facts [

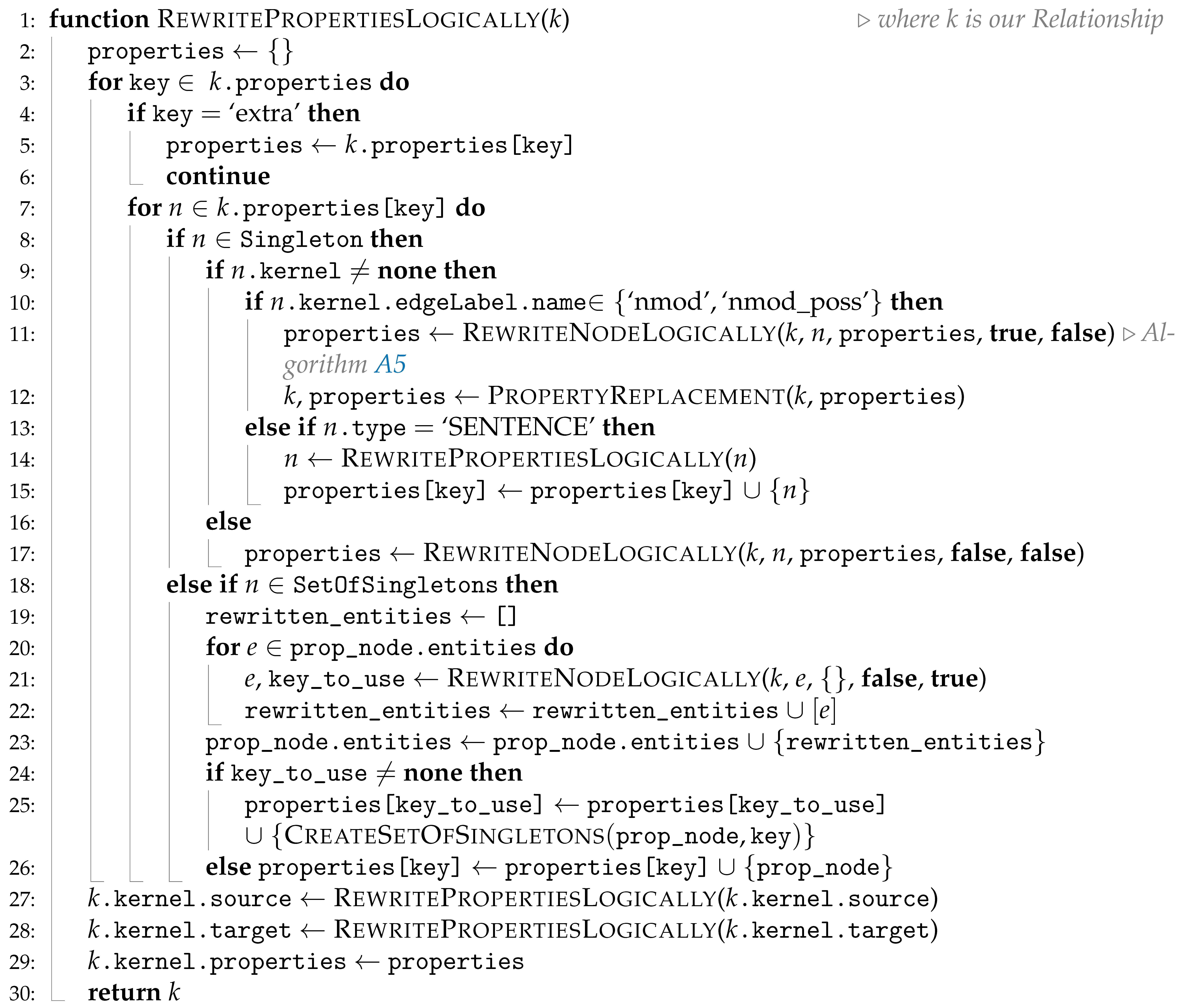

6,

7]. All these consequences are self-evident in current state-of-the-art reasoning mechanisms and are currently referred to as

hallucinations, which cannot be trusted to ensure verifiability of the inference outcome [

8].

This paper walks on current literature evidence, showing that the best way to clear and detect inconsistencies within the data is to provide a rule-based approach to guarantee the effectiveness of the reasoning outcome [

9,

10] as well as by using logic-based systems [

5,

11]. Given the dualism between query and question answering [

5], and given that query answering can be answered through structural similarity [

12], we want first to address the research question of how to properly capture full-text sentence similarity containing potentially conflicting and contradictory data. Then, we assess the ability of current state-of-the-art learning-based approaches to do so, rather than solving the question problem directly, to solidify our findings. While doing so, we also address the question of whether such systems can capture logical-sentence meaning as well as retain spatiotemporal subtleties.

Vector embeddings, widely incorporated in these systems, lead to structural deficiencies in understanding given full-texts and ultimately destroy any possibility of properly explaining language. Neither vectors nor graphs independently can represent semantics and structure, as vectors lose structural information through averaging [

13], while graph representations of sentences cannot usually convey similar structure for semantically similar sentences. Furthermore, they cannot faithfully express logical connectives: for the latter, none of the current graph-based representations uses nested nodes to represent a group of entities under a specific logical connector [

14,

15]. Metrics conceived for determining similarity are typically symmetric and, therefore, do not convey asymmetric notions of entailment, enhanced by this lack of logical connectives: e.g., if there is traffic in the city, then there is traffic also in the city centre, while the latter implication is in doubt. Vector-based systems use cosine similarity, which is trivially symmetric due to the use of the dot product. Graph-based similarity metrics are also symmetric, as the structural similarity is derived in terms of structural alignments across nodes and edges of interest [

12]. Given the above, we cannot use structure or semantics alone to capture the full understanding of a given full-text; our code bridges the gap between them so it becomes possible.

Our previous work [

16] has started to approach this problem, removing the black box and tunnelling in from a graph and logic point-of-view, which this paper continues to investigate. Explainability is vital in ensuring users’ trust in sentence similarity. The Logical, Structural and Semantic text Interpretation (LaSSI) (

https://github.com/LogDS/LaSSI/releases/tag/v2.1, Accessed on 28 March 2025) pipeline takes a given full-text and transforms it into First-Order Logic (FOL), where we are returned with a representation that is both human and machine-readable, providing a way for similarity to be determined from full-text, as well as a way for individuals to reverse-engineer how this similarity was calculated. Similarity is then derived by reconciling such formulæ into minimal propositions, which similarity is then addressed to derive the overall sentence similarity. By providing a tabular representation of both sentences, we can derive the confidence associated with the two original sentences, naturally leading to a non-symmetric similarity metric considering the possible worlds where sentences are valid.

While transformers can learn some semantical patterns occurring within full-text, they struggle with complex logic and nuances in natural language and do not fully grasp the semantic equivalence of active and passive sentences or perform multi-step spatiotemporal reasoning requiring common-sense knowledge. This is identified through clustering algorithms, highlighting how our proposed and transformer approaches differ in correctly clustering groups of full-text. Similarly, graph-based solutions, while effective in representing structure and relationships, face challenges in graph construction and handling the ambiguity of natural language. Both approaches have limitations in capturing the logical implications in spatiotemporal contexts.

Our pipeline aims to leverage these limitations: this is achieved through key pre-processing steps that acknowledge structure properly, by contextualising semantics to rewrite a given graph and generate a formula. Consequently, given sentences with equivalent meaning that produce structural disparate graphs, we get equal formulæ . An intermediate graph representation is constructed before this formula creation, where we execute a topological sort on our initial graph, so that we encompass recursive sentence structure possibly contained within full-texts, perform Multi-Word Entity Unit (MEU) recognition where we identify context behind entities within sentences, and incorporate these within properly defined properties of a sentence kernel. Our experiments show that these conditions cannot be captured with semantics alone.

This paper addresses the following research questions through both theoretical and experiment-driven results:

- RQ №1

Can transformers and graph-based solutions correctly capture the notion of sentence entailment? Theoretical results (

Section 4.1) remark that similarity metrics mainly considering symmetric properties of the data are unsuitable for capturing the notion of logical entailment, for which we at least need quasi-metric spaces or divergence measures. This paper offers the well-known metric of confidence [

17] for this purpose and contextualises it within logical-based semantics for full-text.

- RQ №2

-

Can transformers and graph-based solutions correctly capture the notion of sentence similarity? The previous result should implicitly derive the impossibility of deriving the notion of equivalence as entailment implies equivalence through if-and-only-if but not vice versa, we aim at deriving similar results through empirical experiments substantiating the claims in specific contexts. We then design datasets addressing the following questions:

- (a)

Can transformers and graph-based solutions capture logical connectives? Current experiments (

Section 4.2.1) show that vector embeddings generated by transformers cannot adequately capture the information contained in logical connectives, which can only be considered after elevating such connectives as first-class citizens (Simple Graphs vs. Logical Graphs). Furthermore, given the experiments’ outcome, vector embedding likely favours entities’ position in the text and discards logical connectives occurring within the text as stop words.

- (b)

Can transformers and graph-based solutions distinguish between active and passive sentences? Preliminary experiments (

Section 4.2.2) show that structure alone is insufficient to implicitly derive semantic information, which requires extra disambiguation processing to derive the correct representation desiderata (Simple and Logical graphs vs. Logical). Furthermore, these experiments reaffirm the considerations on the positionality and the stop word from the previous research question, as vector embeddings cannot clearly distinguish between active and passive sentences (Logical vs. Transformer-based approaches).

- (c)

Can transformers and graph-based solution correctly capture the notion of logical implication (e.g.) in spatiotemporal reasoning? Spatiotemporal reasoning requires specific part-of and is-a reasoning that is, to the best of our knowledge and at the time of the writing, unprecedented in current literature on logical-based interpretation of the text. Consequently, we argue that these notions cannot be captured by embeddings alone and by graph-based representations using merely structural information, as this requires categorising the logical function of each entity occurring within the text as well as correctly addressing the interpretation of the logical connectives occurring (

Section 4.2.3).

- RQ №3

Is our proposed technique scalable? Benchmarks over a set of 200 sentences retrieved from sentences occurring within ConceptNet [

18] (

Section 4.3) remark that our pipeline works in at most linear time over the number of the sentences, thus remarking the optimality of the envisioned approach.

- RQ №4

Can a single rewriting grammar and algorithm capture most factoid sentences? Our discussion (

Section 5) remarks that this preliminary work improves over the sentence representation from our previous solution, but there are still ways to improve the current pipeline. We also argue the following: given that training-based systems are also based on annotated data to correctly identify patterns and return correct results (

Section 2.2), the output provided by training-based algorithms can be only as correct as the ability of the human to consider all the possible cases for validation. Thus, rather than postulating the need for training-based approaches in the hope the algorithm will be able to generalise over unseen patterns within the data, we speculate the inverse approach should be investigated. This is because the only possible way to achieve an accurate semantic representation of the text is through accurate linguistic reconstruction using derivational-based and pattern-matching approaches (

Section 2.3).

The paper is then structured as follows: after contextualising our attempt of introducing for the first time verified AI within the context of Natural Language Processing (NLP) through explainability (

Section 2.1), we mainly address current NLP concepts for conciseness purposes (

Section 2.2). Then, we motivate that our pipeline achieves hybrid explainability by showing its ability to provide

a priori explanations (

Section 3.2), from which the text is enriched with contextual and semantic information,

ad hoc explanations (

Section 3.3), through which the sentence is now represented in a verifiable representation (be that a vector, a graph, or a logical formula), and a final human-understandable

ex post explanation (

Section 3.4), through which we boil down the desired textual representation generated by the forthcoming phase into a similarity matrix. This helps to better appreciate how the machine can interpret the similarity of the text. After providing an in-depth discussion on the improvements over our previous work (

Section 5), we draw our conclusions

4. Results

The result section is structured as follows: after showing the impossibility of deriving the notion of logical entailment via any symmetric similarity function (

Section 4.1), we provide empirical benchmarks showing the impossibility of achieving this through classical transformer-based approaches (

Section 4.2). We base our argument on the following observation: given that current symmetric metrics are better suited to capture sentence similarity through clustering due to their predisposition of representing equivalence rather than entailment, we show that assuming symmetrical metrics also leads to incorrect clustering outcomes, out of which dissimilar or non-equivalent sentences are grouped. Experiments further motivate the inability of such transformer-based approaches to adequately distinguish the role of the same entities occurring within the sentence when different sentence forms and negations are given (

Section 4.2.2), the inability to capture the nuances offered by logical connectives (possibly due to the interpretation of these as stop words to be removed,

Section 4.2.1), and the impossibility of performing spatiotemporal reasoning due to the inability of conveying reasoning mechanisms by force of just semantic similarity (

Section 4.2.3). Last, we address the scalability of our proposed approach by considering a sub-sent of full-text sentences appearing as nodes for the ConceptNet common-sense knowledge graph (

Section 4.3). Last, the discussion Section (

Section 5) provides some reflection on our work and how this improved over our previous version of the LaSSI pipeline.

The experiments were run on a Linux Desktop machine with the following specifications:

CPU: 12th Gen Intel i9-12900 (24) @ 5GHz,

Memory: 32GB DDR5. The raw data for the results, including confusion matrices and generated final logical representations, can be found on OSF.io (

https://osf.io/g5k9q/, Accessed 28 March 2025).

4.1. Theoretical Results

As the notion of verified AI incentivises inheriting logical-driven notions for ensuring the correctness of the algorithms [

19], we then leverage the logical notion of

soundness [

60] to map the common-sense interpretation of a full-text into a machine-readable representation (let that be a logical rule or a vector embedding); a rewriting process is sound if the rewritten representation logically follows from the original sentence, which then follows the notion of correctness. For the sake of the current paper, we limit our interest to capturing logical entailment as generally intended from two sentences. Hence, we are interested in the following definition of soundness:

Definition 11.

Weak Soundness, in the context of sentence rewriting, refers to the preservation of the original semantic meaning of the logical implication of two sentences α and β. Formally:

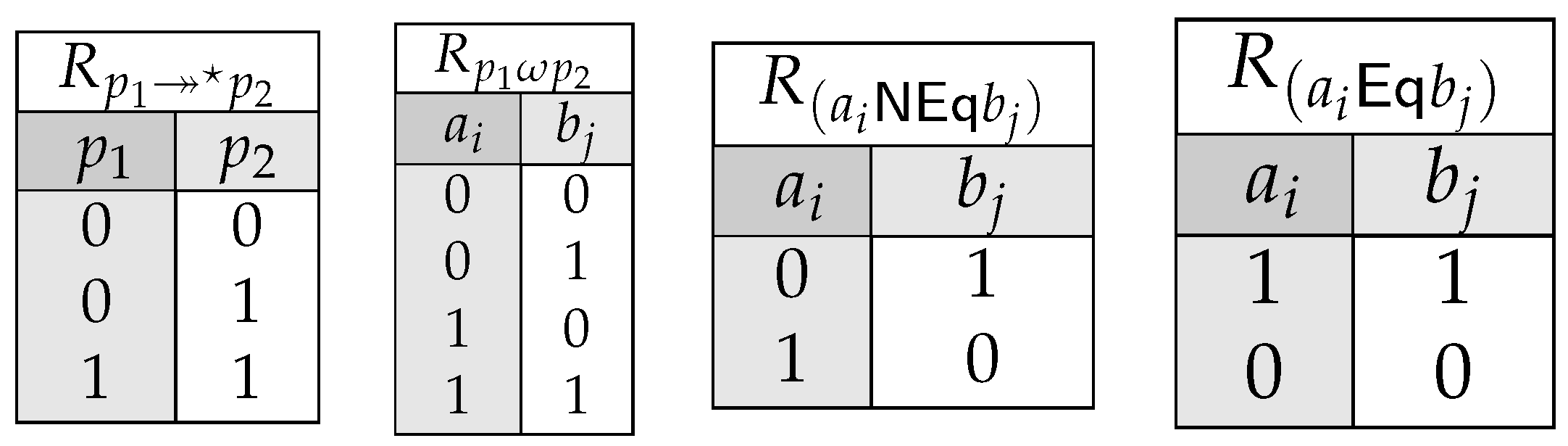

where S is the common-sense interpretation of the sentence, ⊑ is the notion of logical entailment between textual concepts, and is a predicate deriving the notion of entailment from the τ transformation of a sentence via the choice of a preferred similarity metric .

In the context of the paper, we are then interested in capturing sentence dissimilarities in a non-symmetrical way, thus capturing the notion of logical entailment:

The following results remark that any symmetric similarity metrics (thus including the cosine similarity and the edge-based graph alignment) cannot be used to express logical entailment (

Section 4.1.1), while the notion of confidence adequately captures the notion of logical implication by design (

Section 4.1.2). All the proofs for the forthcoming lemmas are moved to

Appendix D.

4.1.1. Cosine Similarity

This entails that we can always derive a threshold value above which we can deem as one sentence implying the other, thus enabling the following definition:

Definition 12.

Given α and β are full-text and τ is the vector embedding of the full-text, we derive entailment from any similarity metric as follows:

where θ is a constant threshold. This definition allows us to express implications as exceeding a similarity threshold.

As cosine similarity captures the notion of similarity, and henceforth an approximation of a notion of equivalence, we can clearly see that such metric is symmetric.

Lemma 13. Cosine similarity is symmetric

Symmetry breaks the capturing of directionality for logical implication. Symmetric similarity metrics can lead to situations where soundness is violated. For instance, if holds based on a symmetric metric, then would also hold, even if it’s not logically valid. We derive implication from similarity when the similarity metric for is different to , given that , and this shows that one thing might imply the other but not vice versa. To enable the identification of implication across different similarity functions, we entail the notion of implication via the similarity value as follows:

Lemma 14.

All symmetric metrics trivialise logical implication:

Since symmetric metrics like cosine similarity cannot capture the directionality of implication, they cannot fully represent logical entailment. This limitation highlights the need for alternative approaches to model implication accurately, thus violating our intended notion of correctness.

4.1.2. Confidence Metrics

Differently from the former, we show that the confidence metric presented on

Section 3.4 produce a value that aims to express logical entailment under the assumption that the

transformation from full-text to logical representation is correct.

Lemma 15.

When two sentences are equivalent, then they always have the same confidence.

As a corollary of the former, this shows that our confidence metric is non-symmetric.

Corollary 16.

Confidence provides an adequate characterisation of logical implication.

This observation leads to the definition of the following notion of given the processing pipeline:

Definition 17.

Given α and β are full-text and τ is the logical representation of the full-text as derived from the ad hoc phase (Section 3.3), we derive entailment from any similarity metric as follows:

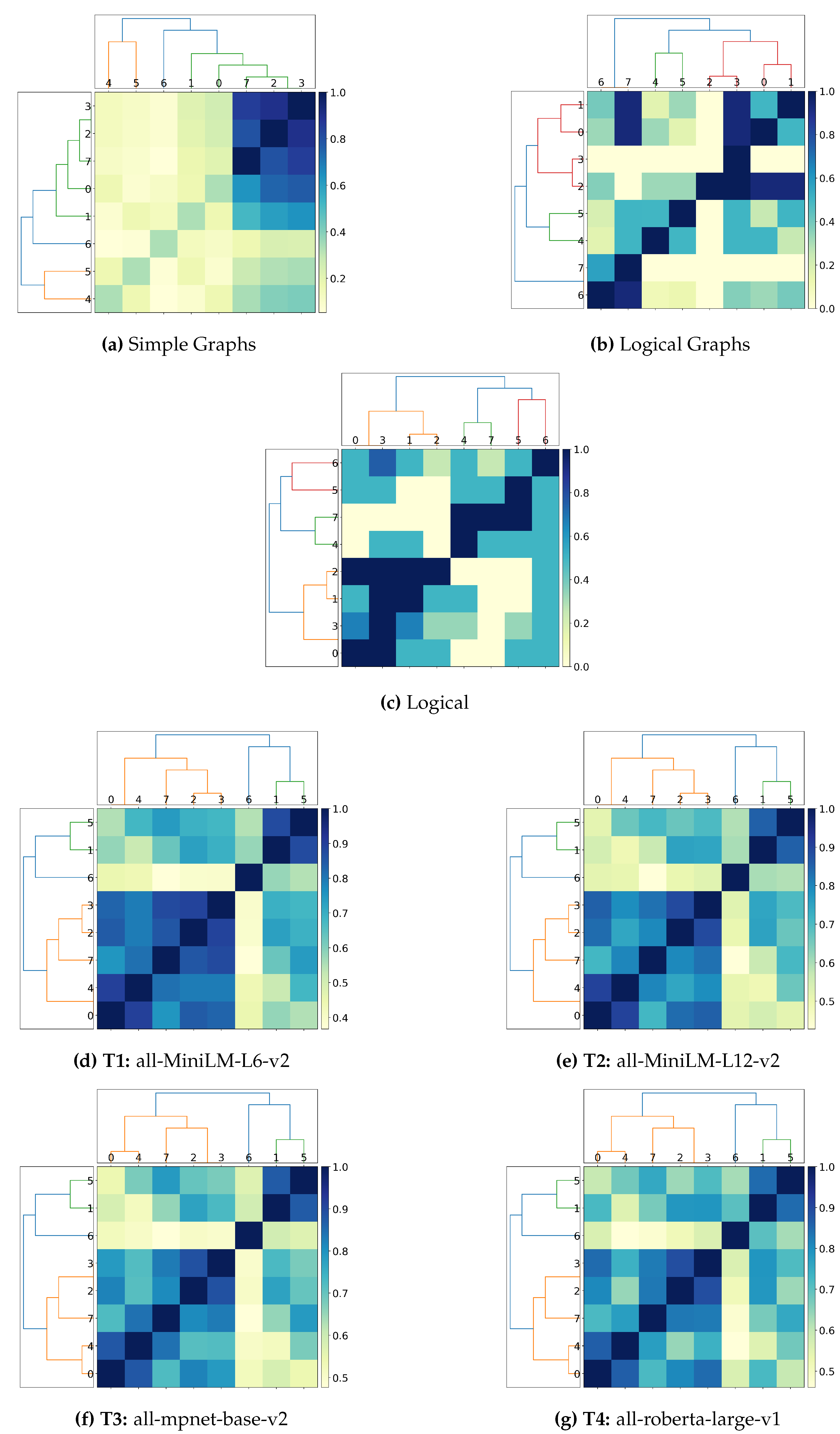

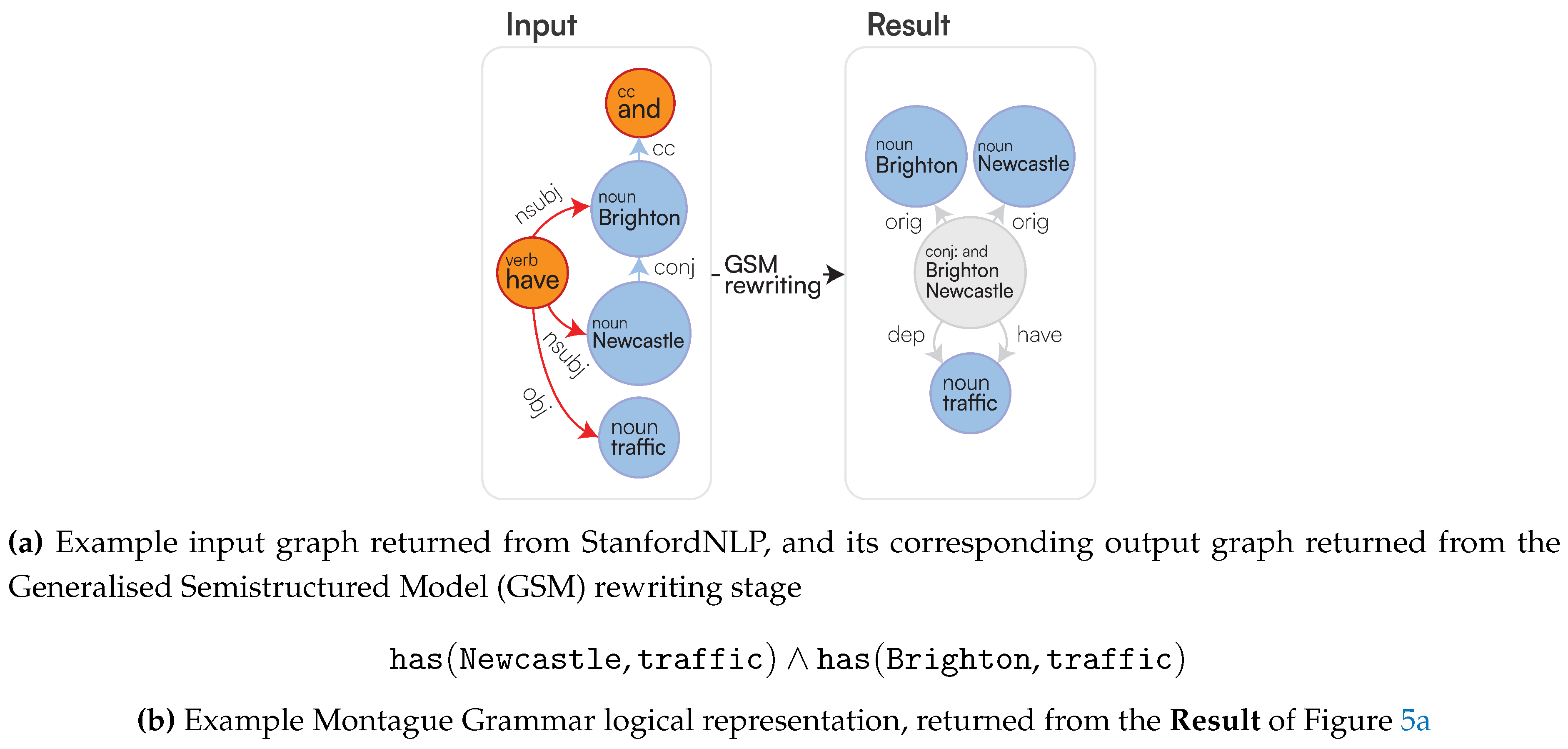

4.2. Clustering

While the previous section provided the basis for demonstrating the theoretical impossibility of achieving a perfect notion of implication, the following experiments are aimed at testing this argument from a different perspective: we want to test which of these metrics is well-suited for expressing the notion of logical equivalence as per original design. Given that the training-based approach cannot ensure a perfect notion of equivalence returning a perfect 1 score for extremely similar sentences, we can relax the argument by requiring that there exists any suitable clustering algorithm allowing to group some sentences of choice by distance values providing the closest match to the group of expected equivalent sentences of choice. Then, the correctness of the returned clustering match is computed using a well-defined set-based alignment metric from [

53] being a refinement of Eq.

2 using

, where

is the indicator function returning 1 if and only if (iff). the condition

P holds and 0 otherwise [

61]. To remove any semantic ambiguity derivable from analysing complex sentences with multiple entities, we consider smaller ones so to have controlled experiments under different scenarios: distinguishing between active and passive sentences (

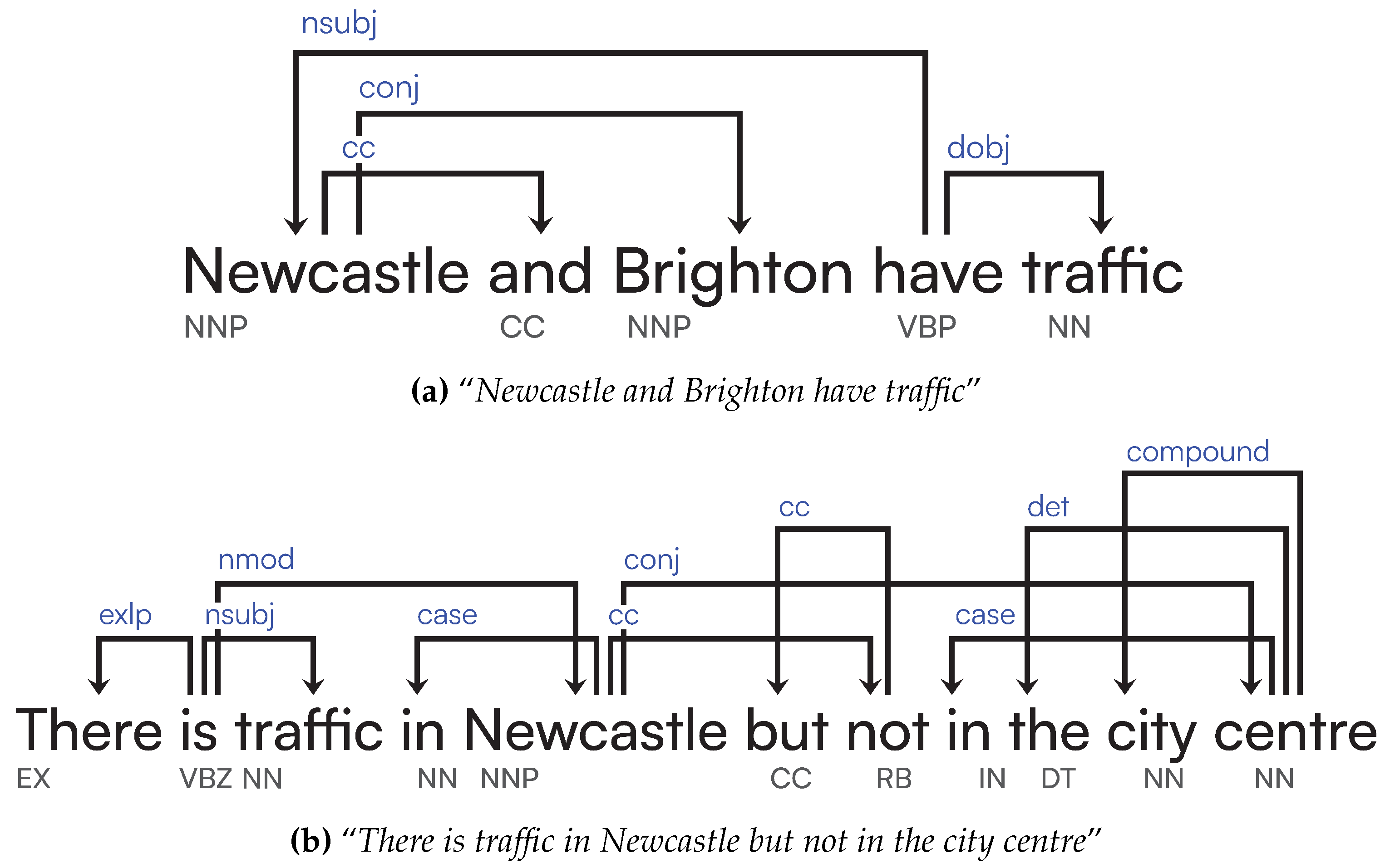

Figure 12a), considering logical connectives within sentences (

Figure 10a), and expressing simple spatiotemporal reasoning (

Figure 13a). If, under these considerations, the current state-of-the-art textual embeddings cannot capture the notion of sentence similarity by always returning clusters not adequately matching the expected ones (

Figure 12b,

Figure 10b and

Figure 13b), we then could then conclude that these representations are not well-suited to capture reasoning-driven processes, thus corroborating the observations from preliminary theoretical results [

62].

Deriving Distance Matrices from our Similarity Metrics and Sentences

We use transformers

as made available via HuggingFace [

63] coming from the current state-of-the-art research papers:

all-roberta-large-v1 [

66]

For all the approaches, we consider all similarity metrics

already being normalised between 0 and 1 as discussed in

Section 3.4. We can derive a distance function from this by subtracting such value by one, hence

. As not all of these approaches lead to symmetric distance functions and given that the clustering algorithms work under symmetric distance functions, we obtain a symmetric definition by averaging the distance values as follows:

Clustering Algorithms of Choice

We test our hypothesis over two clustering algorithms supporting distance metrics as an input rather than a collection of points in the d-dimensional Euclidean space, Hierarchical Agglomerative Clustering (HAC) and k-Medoids.

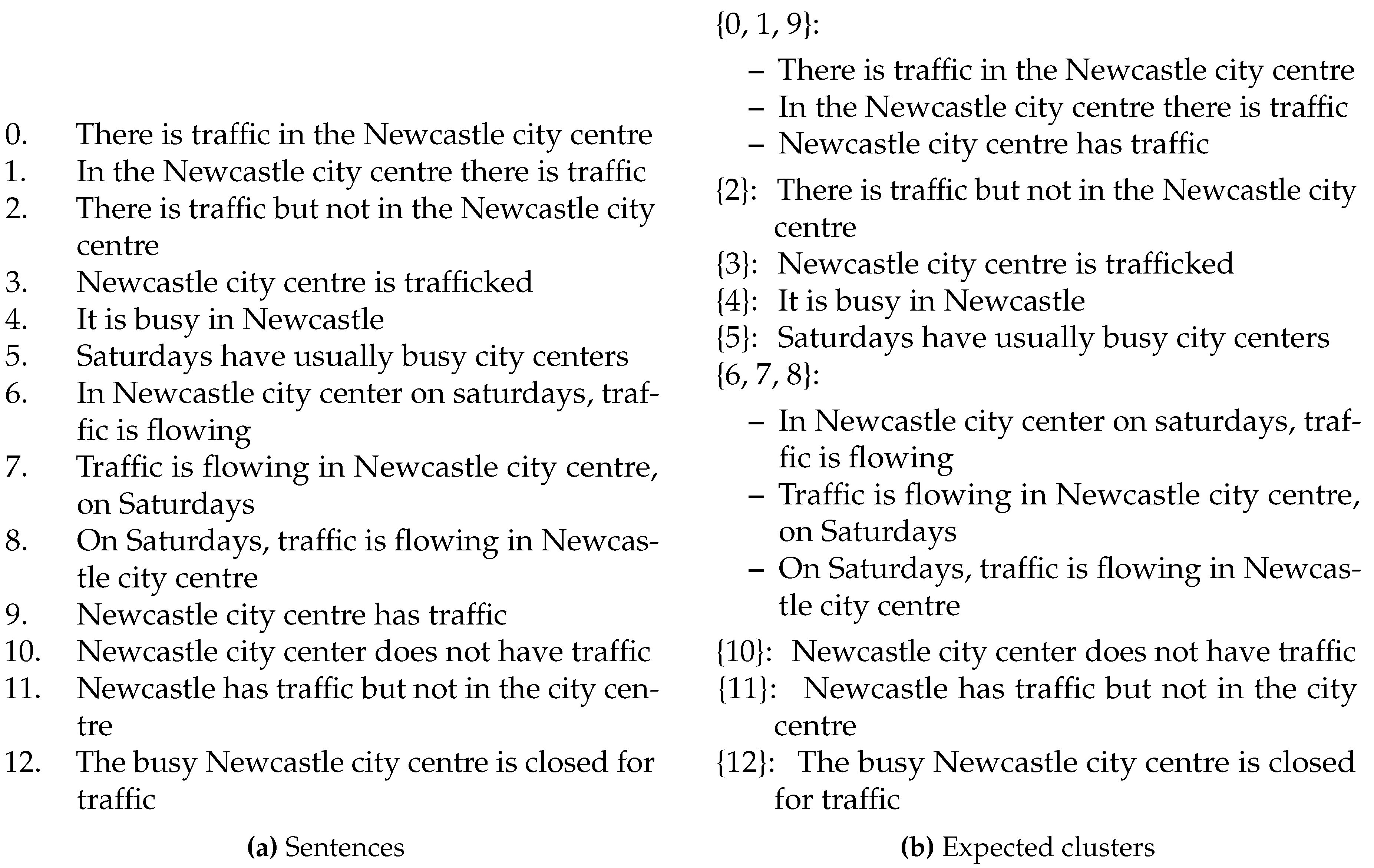

HAC [

67] is a hierarchical clustering method that uses a `bottom-up’ approach, starting with creating the clusters from the data points having the least distance. By considering each data point as a separate cluster, these are iteratively merging the least distance pair of clusters according to a given linkage criterion until we reach the number of the desired clusters, by which point the clustering algorithm will stop [

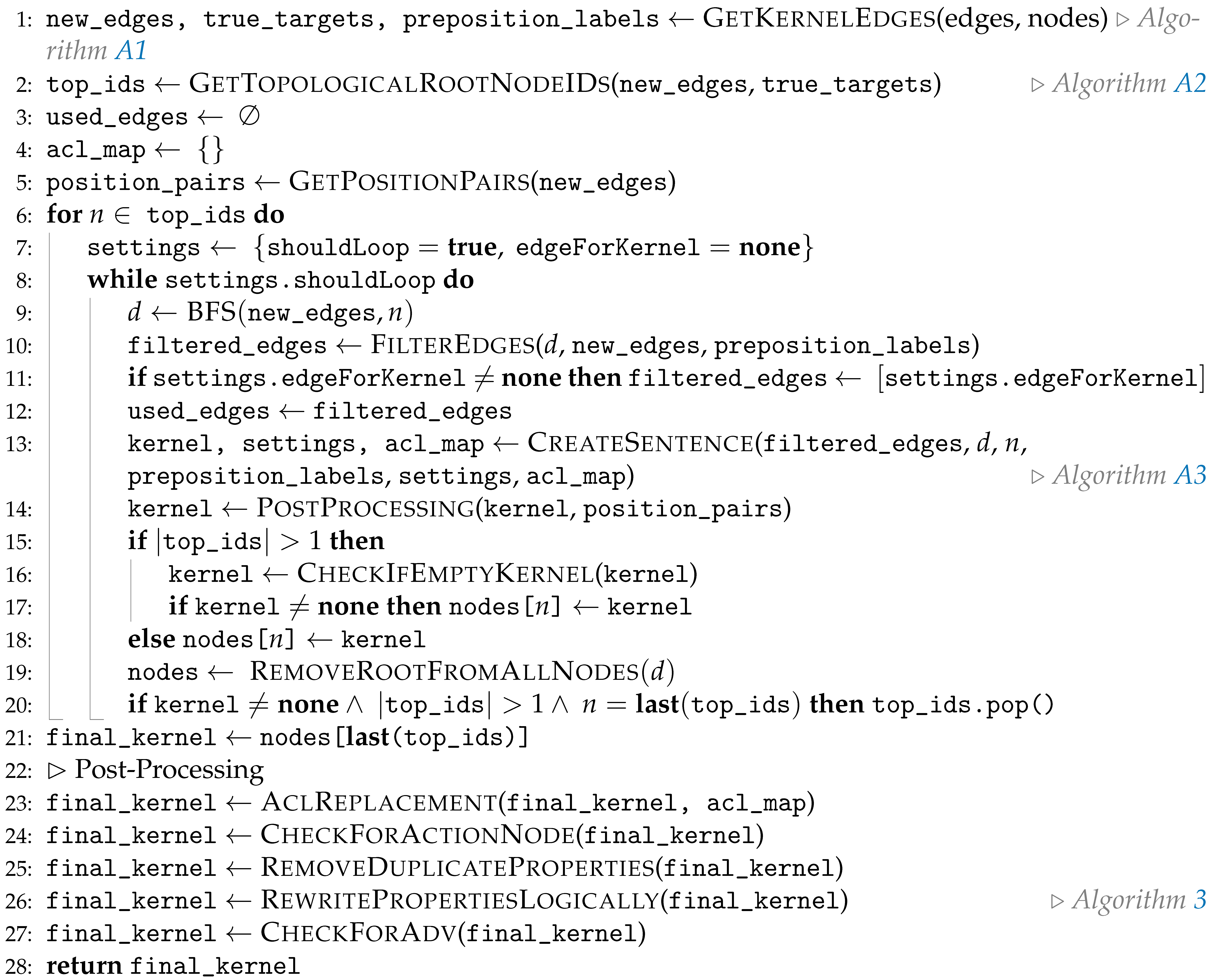

68]. The graphs visualised in

Figure 9,

Figure 11, and

Figure 14 are

dendograms, which allow for exploring relationships between clusters at different levels of granularity. In our experiments, we consider the complete link criterion for which the distance between two clusters is defined as the distance between two points, each for one single cluster, maximising the overall distance [

69].

k-Medoids [

70] is a variation of the

k-Means Clustering where, as a first step, the algorithm will start by picking actual data points as centres of the cluster while being suited to support distance metrics by design. Assuming these initial medoids as centres of their clusters, each point is assigned to the cluster identified by the nearest medoid. At each step, we might consider swapping a medoid with another node if this minimises the clustering assignment costs. The iteration converges after a maximum number of steps or when we reach stability, i.e., no further clusters are updated. As this approach also minimises a sum of pairwise dissimilarities rather of a sum of squared Euclidean distances as

k-Means,

k-Medoids is more robust to noise and outliers than

k-Means.

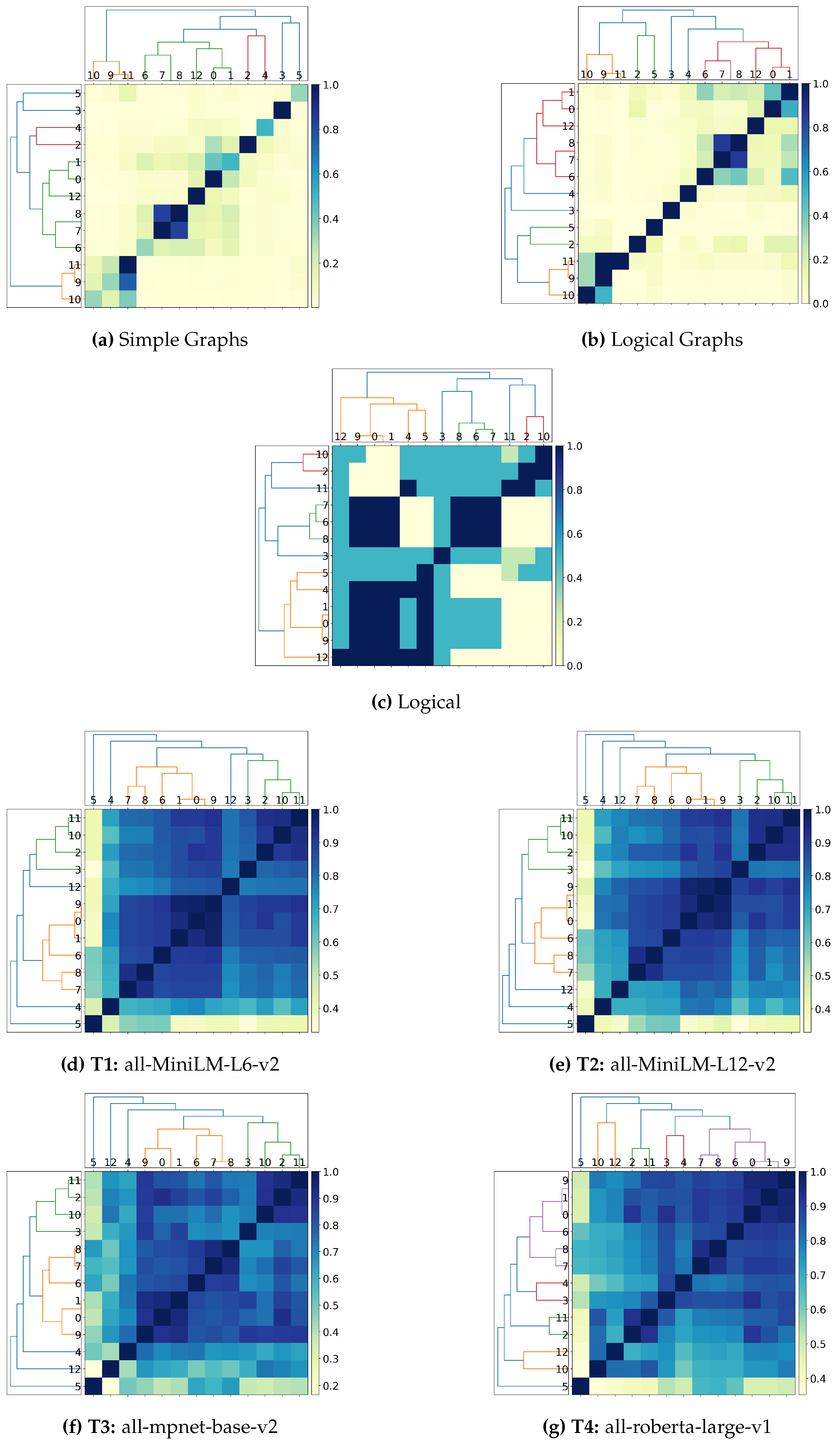

Figure 9.

Dendogram clustering for ’Alice and Bob’ sentences.

Figure 9.

Dendogram clustering for ’Alice and Bob’ sentences.

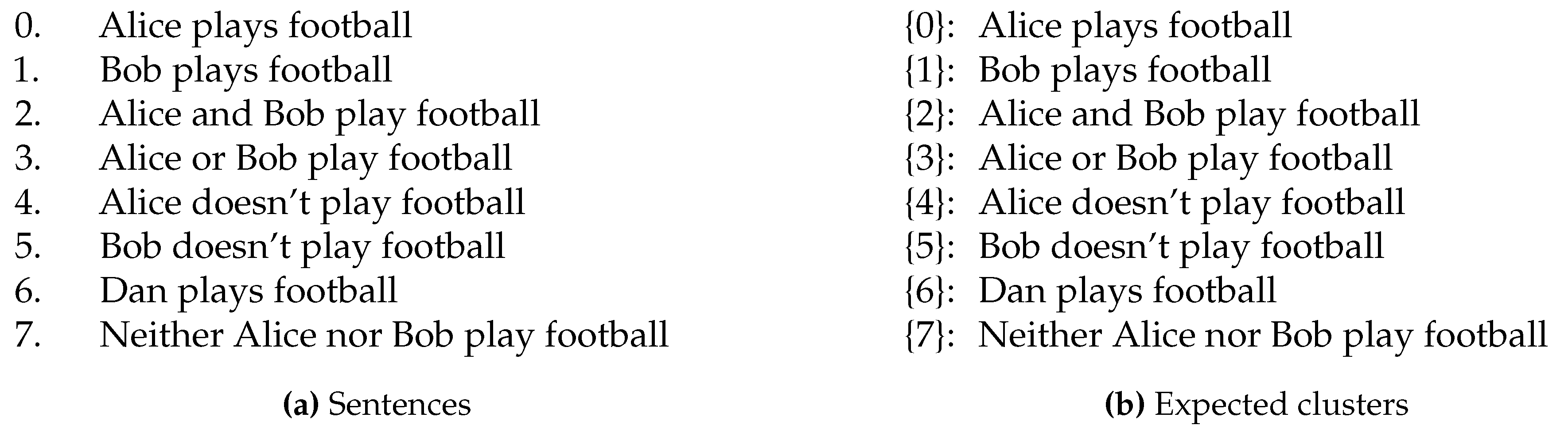

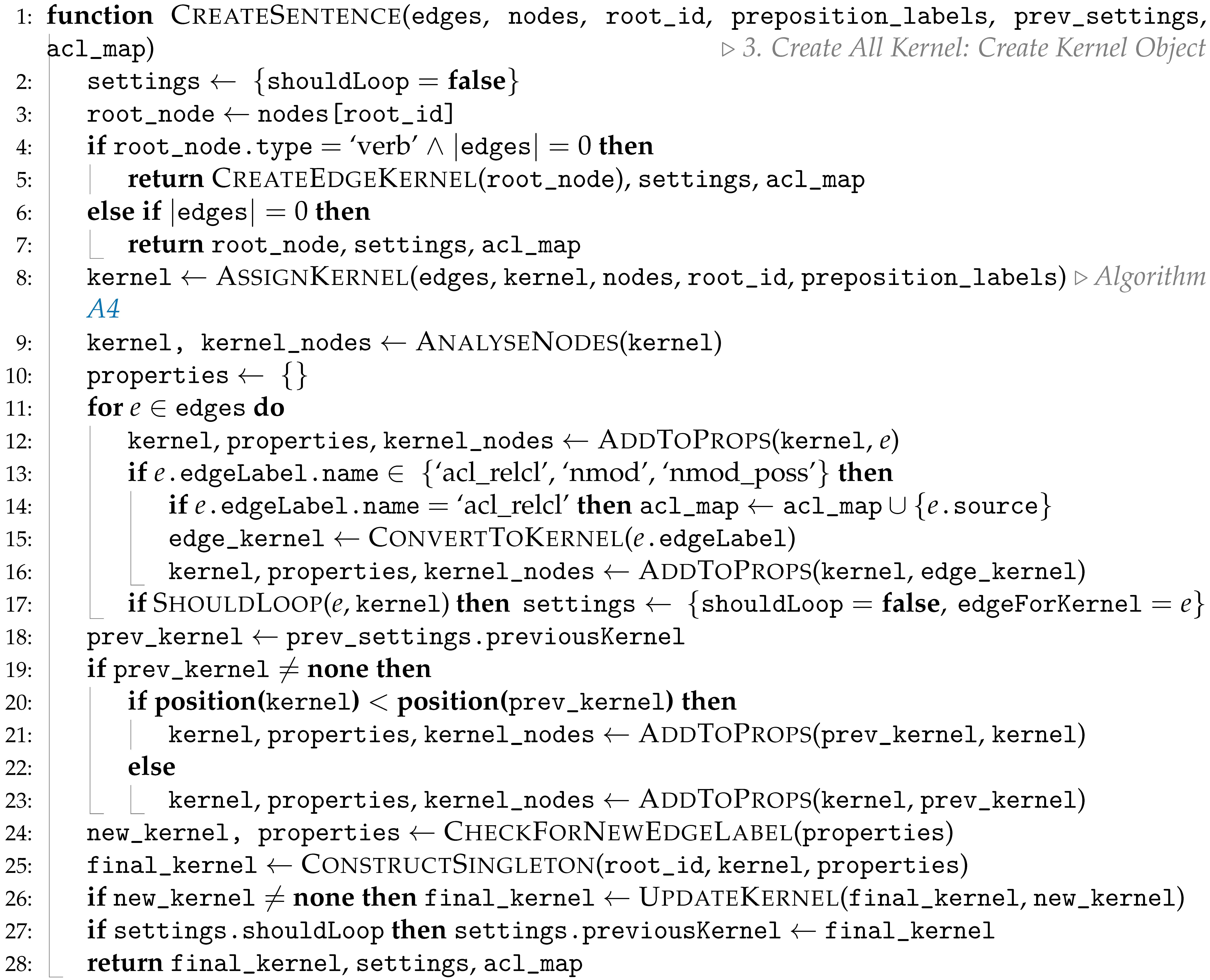

4.2.1. Capturing Logical Connectives and Reasoning

We want to prove that state-of-the-art vector-based semantics from the sentence transformers cannot represent logical connectives appearing in sentences, thus postulating the need for explicit graph operators to recognise the logical structure of sentences. We are also checking if the logical connectives are also treated as stop words by transformers, thus being ignored. This is demonstrated through sentences in

Figure 10a, whereby one sentence might imply another, but not vice versa. However, with our clustering approaches, we only want to cluster sentences that are similar in

both directions, therefore our clusters remain as only having one element, as shown in

Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Sentences and expected clusters for `Alice and Bob’.

Figure 10.

Sentences and expected clusters for `Alice and Bob’.

Analysing

Table 3, all approaches perfectly align with the expected clusters. However, this is determined by the nature of HAC, since the algorithm starts with this exact configuration where each element it its own cluster, it inherently matches the ground truth from the beginning; therefore, before any merging even occurs, the algorithm has already achieved perfect alignment.

Instead, investigating the graphs in

Figure 9, we can see that for our Simple Graphs in

Figure 9a, this approach fails to recognise directionality and does not produce appropriate clusters, even failing to recognise similarity a sentence has with itself. Logical Graphs shown in

Figure 9b improve, recognising similarity for 2 ⇒ 0 for example, however, producing a similarity of 0 for 0 ⇒ 2. Finally, our Logical representation in

Figure 9c successfully identifies directionality and appropriately groups sentences together. For example, 2 ⇒ 0 is entirely similar, however, 0 ⇒ 2 is only slightly similar, which entails as “

Alice and Bob play football” implies that “

Alice plays football”, but it does not necessarily hold that

both Alice and Bob play football if we only know that Alice plays football.

The sentence transformer approaches displayed in

Figure 9d–g all produce similar clustering, with high similarities between sentences in the dataset that are incorrect; for example clustering Alice

does and

does not play football are closely related according to the transformers, as aforementioned, this is most likely due to the transformers use of edit-distance, therefore not capturing a proper understanding of the sentences, whereas our approach does, by showing they are dissimilar.

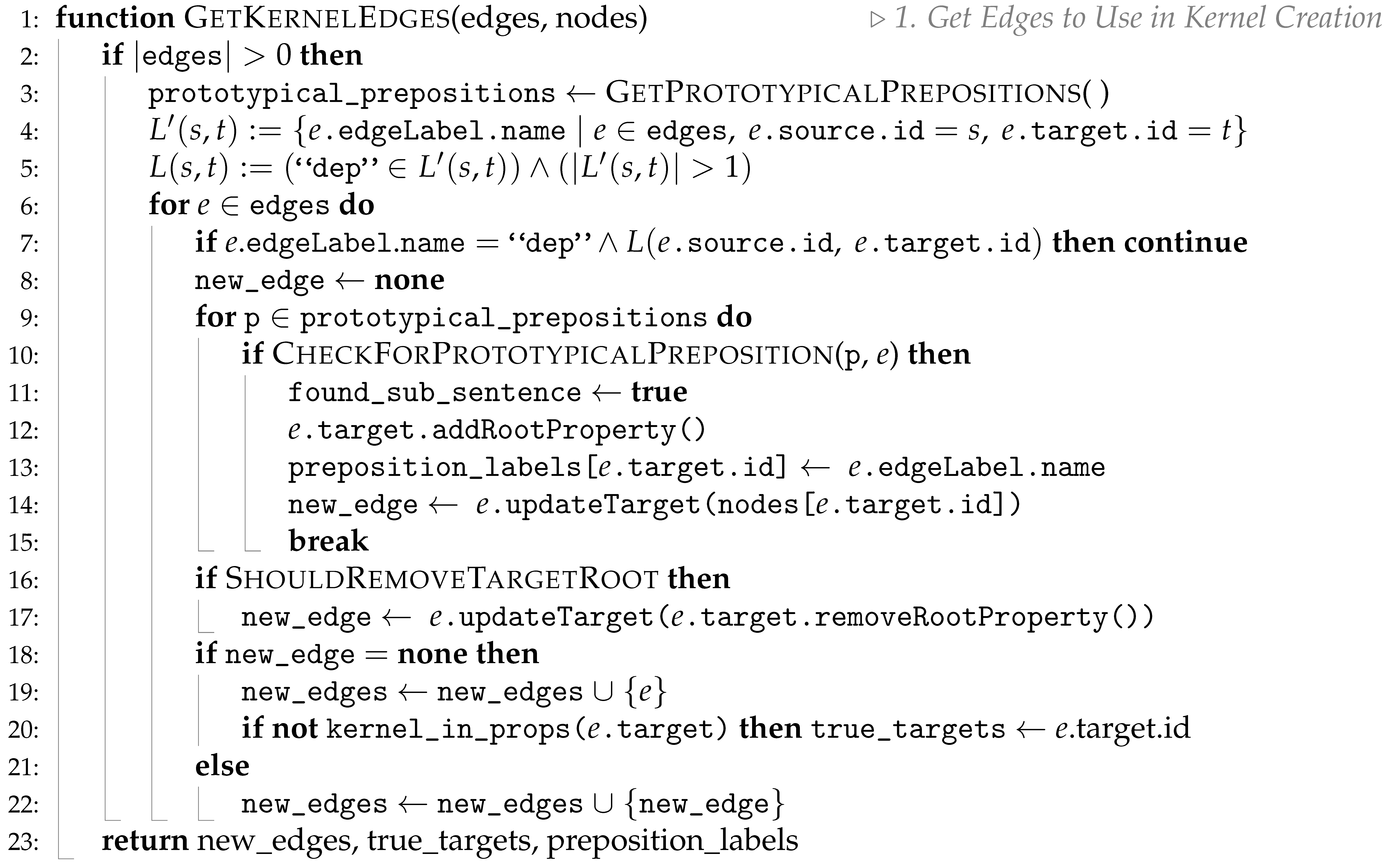

Figure 11.

Dendogram clustering for ’Cat and Mouse’ sentences.

Figure 11.

Dendogram clustering for ’Cat and Mouse’ sentences.

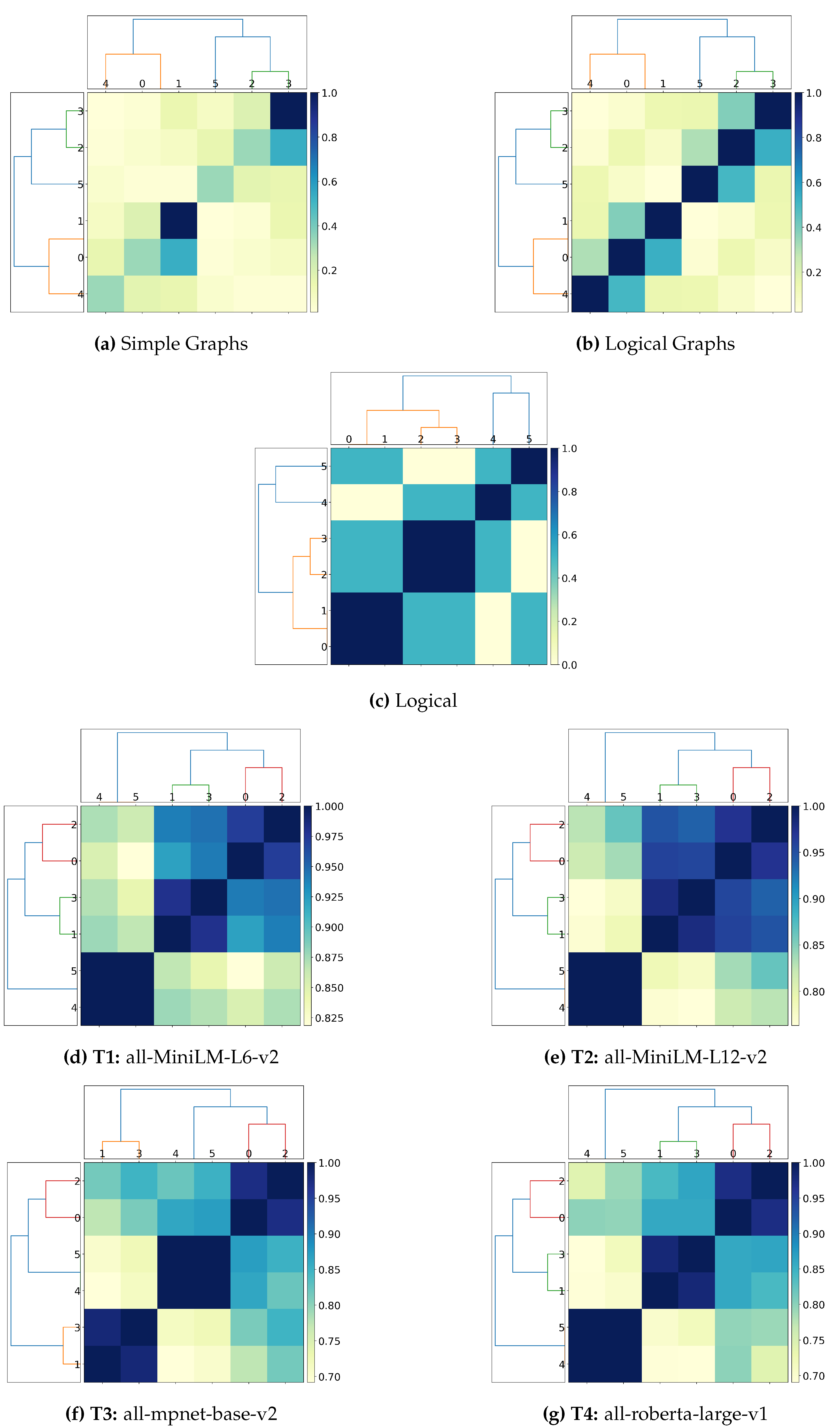

4.2.2. Capturing Simple Semantics and Sentence Structure

The sentences in

Figure 12a are all variations of the same subjects (a cat and mouse), with different actions and active/passive relationships. The dataset is set up this way to produce sentences with similar words but in a different order to tackle whether sentence embedding understands context from structure rather than edit distance.

Figure 12b shows the expected clusters for the `Cat and Mouse’ dataset. 0 and 1 are clustered together because the action from the subject on the direct object is the same in both: `the cat eats the mouse’ is equivalent to `the mouse being eaten by the cat’. Similarly, sentences 2 and 3 are the same, but with the action reversed, the mouse eats the cat in both.

Figure 12.

Sentences and expected clusters for `Cat and Mouse’.

Figure 12.

Sentences and expected clusters for `Cat and Mouse’.

Analysing

Table 4, we can see that all stages of the LaSSI pipeline achieve perfect alignment with HAC and

k-Medoids, effectively capturing the logical equivalence between sentences 0 and 1, and 2 and 3. We can see a gradual increase in the matched clusters in

Figure 11a,

Figure 11b, and

Figure 11b, as the contextual information within the final representation increases with each different sentence representation. Each representation shows a further refinement within the pipeline. The clustering shows values are near to each other, thanks to structural semantics, but does not determine that they are the same. The first two approaches (Simple and Logical Graphs) roughly capture the expected clusters we are looking for but does not encapsulate the entire picture from the similarity of the sentences in the whole dataset, our final logical representation produces the expected perfect matches with {0, 1}, and {2, 3}. This suggests LaSSI can identify the same relationship between the “

cat” and “

mouse”, despite different syntactic structures via active and passive voice.

All the transformer models show lower alignment with HAC and

k-Medoids, 0.3750, implying that while they capture some semantic similarity, they struggle to fully grasp the logical equivalence between the sentences in the same way LaSSI does, and even with some simplistic rewriting from our pipeline, we outperform these state-of-the-art transformers.

Figure 11d–g all show much larger clusters from the ones we would expect, grouping together sentences incorrectly. None of these transformers produces zones with 0 similarity, as they determine all the sentences are related to each other, misinterpreting that “

The cat eats the mouse” and “

The mouse eats the cat” are similar.

The pipeline for these given transformers will ignore stop words which may also impact its resulting scores; we also recognise that the similarity is heavily dominated by the entities occurring, while the sentence structure is almost not reflected: transformers are only considering one sentence as a collection of entities without taking the structure of the sentence into account, whereby changing the order will yield similar results and therefore cannot derive sentence structure. By interpreting similarity with compatibility, graph-based measures exclude entirely the possibility of this happening, while logic-based approaches are agnostic.

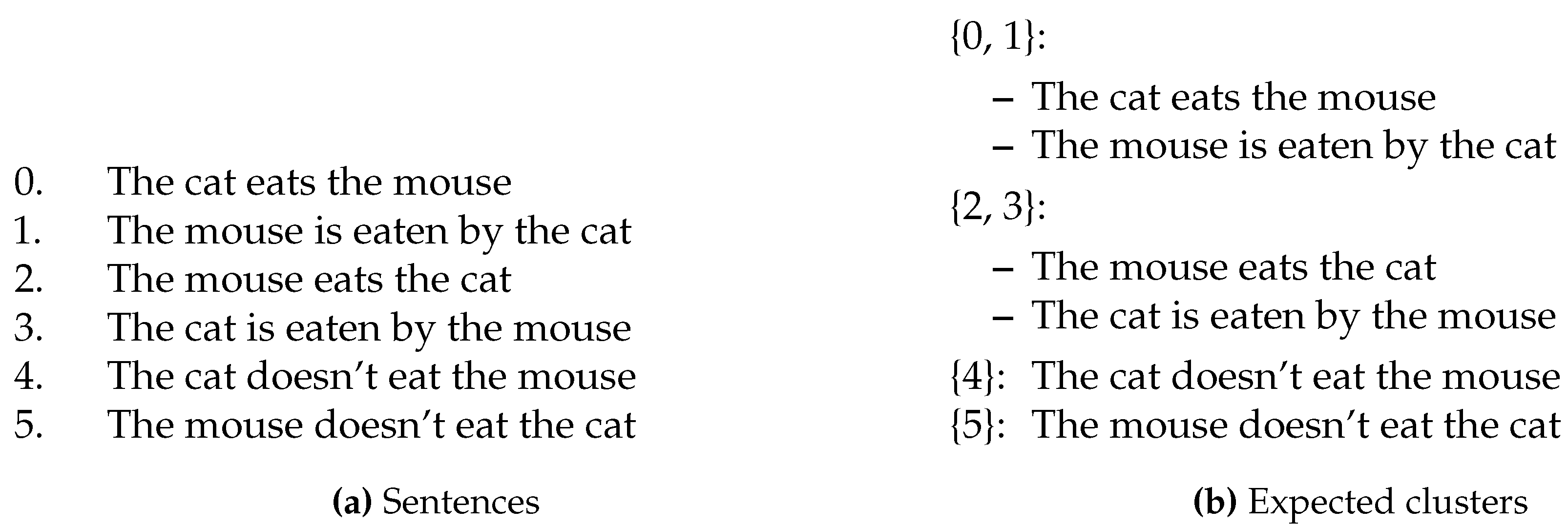

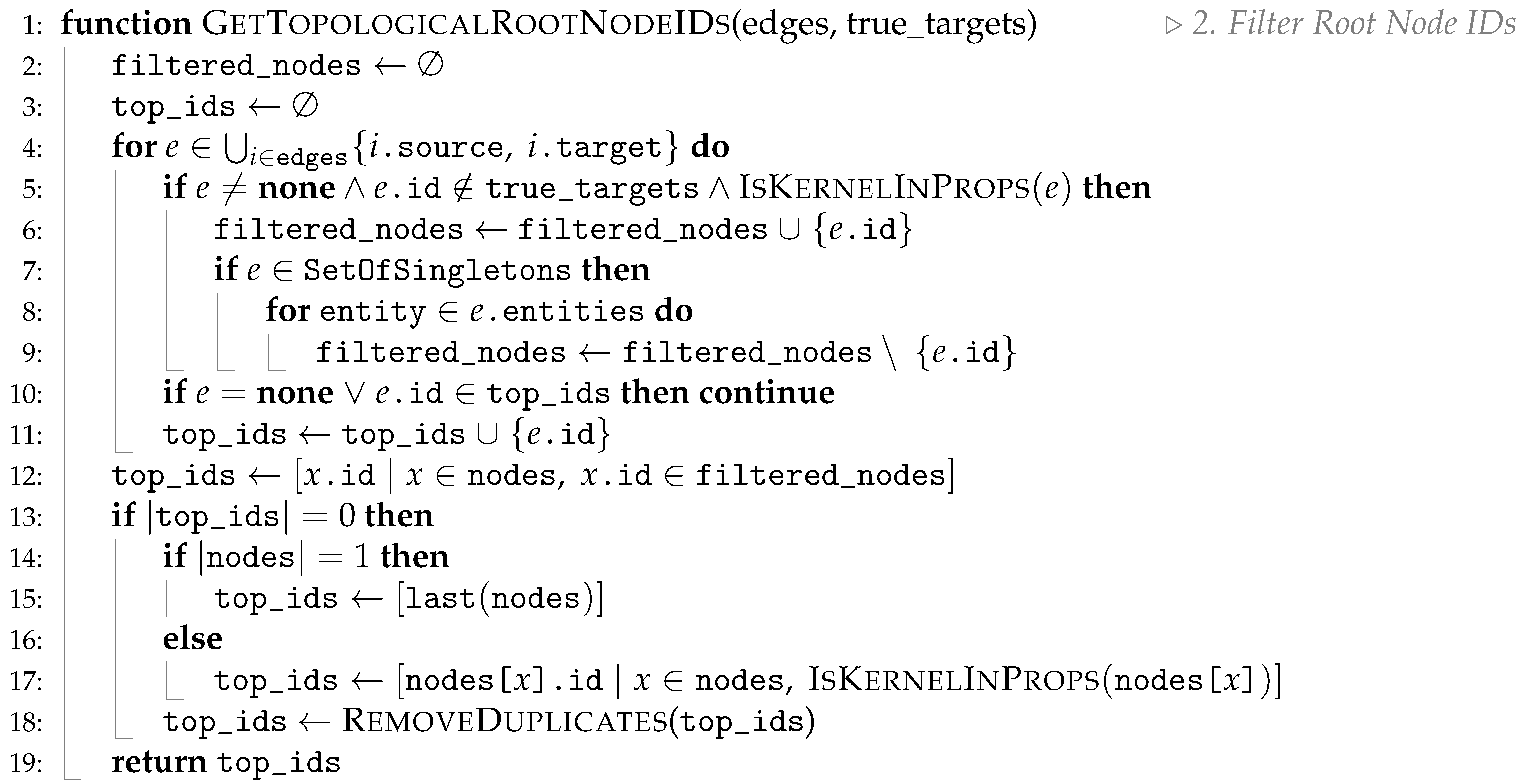

4.2.3. Capturing Simple Spatiotemporal Reasoning

We have multiple scenarios involving traffic in Newcastle, presented in

Figure 13a, which has been extended from our previous paper to include more permutations of the sentences. This was done so that we have multiple versions of the same sentence that should be treated equally by ensuring the rewriting of each permutation is the same, therefore resulting in 100% similarities.

Figure 13.

Sentences and expected clusters for `Newcastle’.

Figure 13.

Sentences and expected clusters for `Newcastle’.

Analysing the results in

Table 5, we can see that our Logical Graphs and Logical approaches outperform the transformers, with our final logical approach achieving 100% alignment against the expected clusters. Our initial approaches fail to fully capture proper spatiotemporal reasoning of the sentences, essentially only capturing the similarity of sentences with themselves. For Simple Graphs in

Figure 14a, we can see some similarity detected between sentences 7 (“

Traffic is flowing in Newcastle city centre, on Saturdays”) and 8 (“

On Saturdays, traffic is flowing in Newcastle city centre”), which is correct, however it should be treated as having 100% similarity, which it does not here. Furthermore, the majority of the dendrogram shows little similarity across the dataset. We see an increase in overall clustering similarity for both HAC and

k-Medoids in the Logical Graphs approach, shown in

Figure 14b, now also capturing similarity between a few more sentences, but overall still not performing as expected. Finally, our Logical approach presents an ideal result, with 100% clustering alignment and a dendrogram that presents clusters that fix our expected outcome. {0,1,9} and {6,7,8} are clustered together, as we would expect, and we also see some further implications being presented. Sentences 0, 1, and 9 (All state: there is traffic in the Newcastle city centre) are clustered towards sentence 4 (“

It is busy in Newcastle”), presenting that if there is traffic in Newcastle city centre, then Newcastle is busy, however this similarity is only 50% in the other direction, as if it is busy in Newcastle, we cannot know for certain that this is caused by traffic. We also correctly see negation being acknowledged, with sentences 0 (“

There is traffic in the Newcastle city centre” and 10 (“

Newcastle city center does not have traffic”) for example being treated as having 0% similarity. Furthermore, a complex implication is captured between 2 and 11. Sentence 2 states that “

There is traffic but not in the Newcastle city centre”, meaning there is traffic

somewhere, but just specifying that it isn’t in Newcastle city centre, while sentence 11 states: “

Newcastle has traffic but not in the city centre”, a subtle difference not captured by any other approach presented. Our Logical approach shows complete similarity for 2 ⇒ 11, but a 50% for 11 ⇒ 2, as there being traffic but not in the Newcastle city centre, implies that there is not traffic in the Newcastle city centre, but if we only know there is not traffic in the city centre, then we cannot know there is traffic everywhere else.

Figure 14.

Dendogram clustering graphs for ’Newcastle’ sentences.

Figure 14.

Dendogram clustering graphs for ’Newcastle’ sentences.

The sentence transformer approaches produce a very high similarity for nearly all sentences in the dataset. There are discrepancies in the returned clusters from what we would expect for several reasons. The word embeddings might be capturing different semantic relationships. For example, “busy” in sentence 4 (“It is busy in Newcastle”) might be considered similar to the “busy city centers” in sentence 5 (“Saturdays have usually busy city centers”), leading to their clustering, even though the context of Newcastle being busy is more general than the usual Saturday busyness. We can see that sentences related to Saturdays (5, 6, 7, 8) form a relatively cohesive cluster in the dendrogram, which aligns with the desired grouping for 6, 7, and 8. However, sentence 5’s early inclusion with the general “busy” statement (4) deviates from the intended separation. Furthermore, the embeddings might be heavily influenced by specific keywords, the presence of “Newcastle city centre” in multiple sentences might lead to their clustering, even if the context around traffic flow or presence is different. As discussed previously, these transformers cannot differentiate between the presence and absence of traffic as intended in the desired clusters. For example, sentence 10 (“Newcastle city center does not have traffic”), is clustered with sentence 2 (“There is traffic but not in the Newcastle city centre”), which is incorrect.

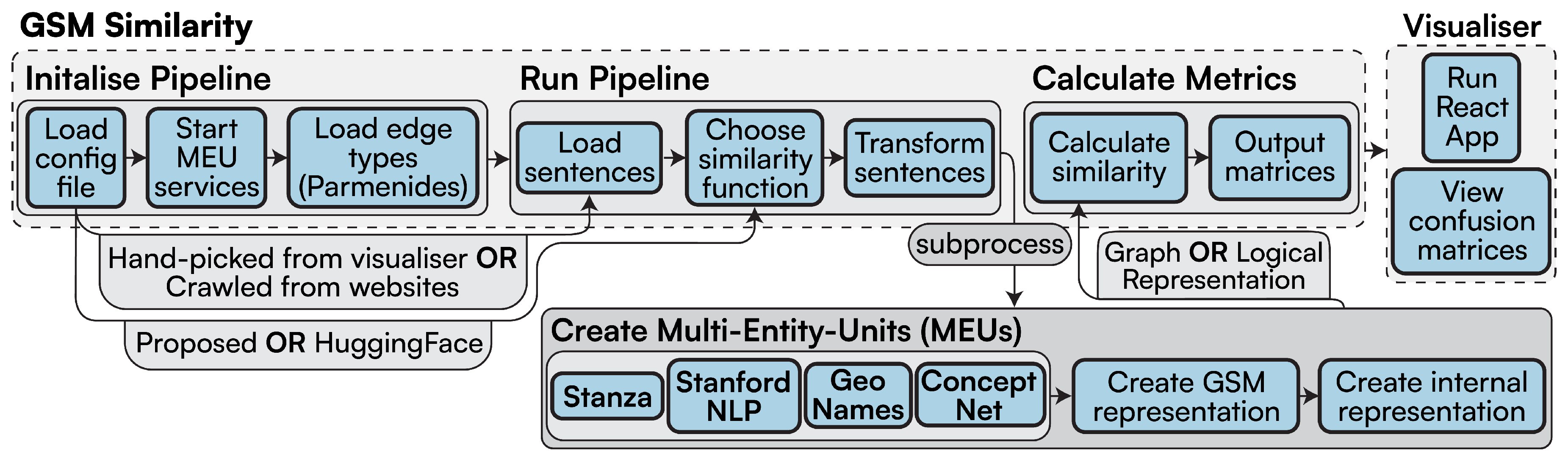

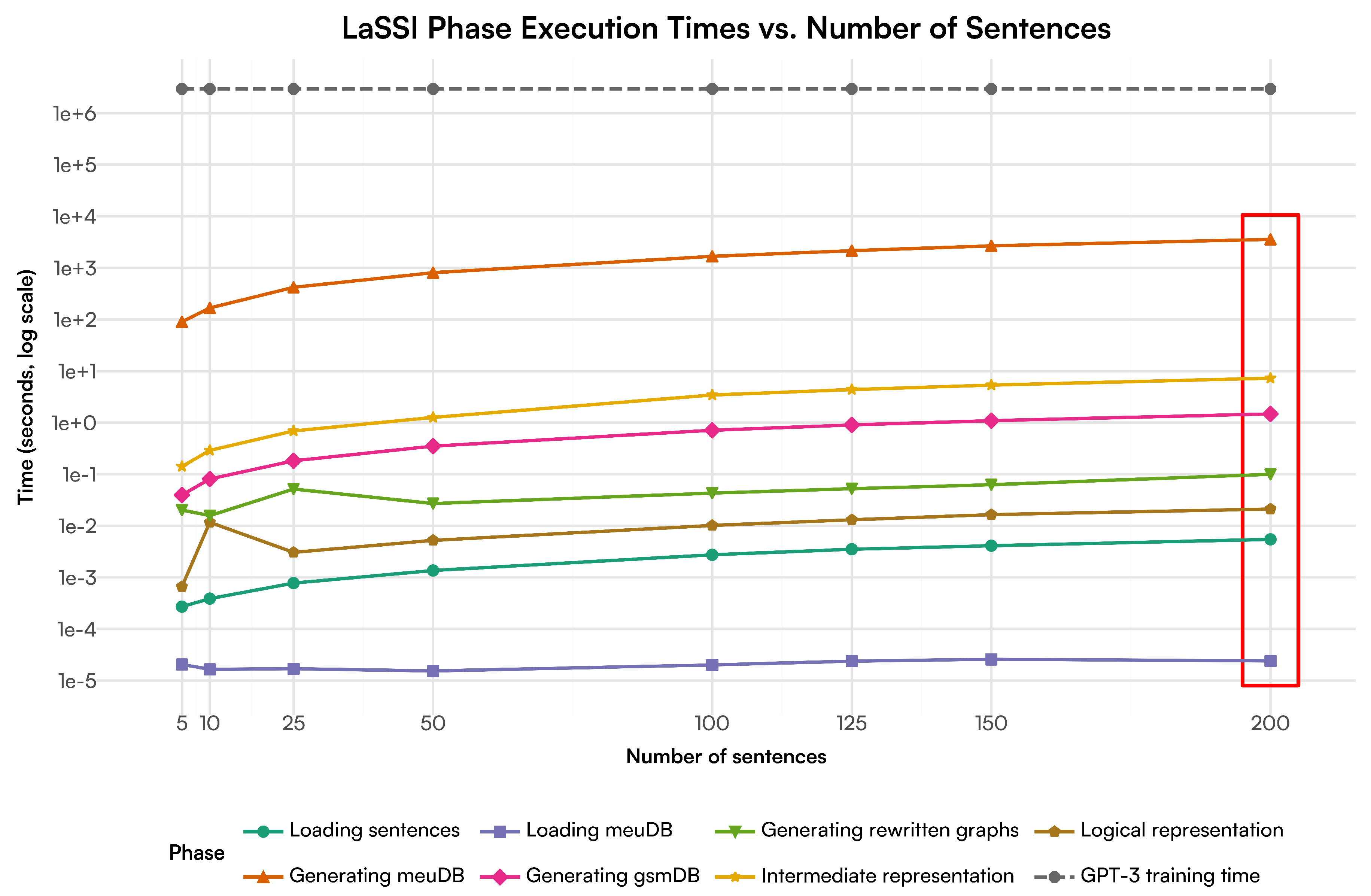

4.3. Sentence Scalability Rewriting

We have broken down the different phases of our LaSSI pipeline and performed scalability experiments with 200 sentences gathered from nodes from ConceptNet [

18].

Loading sentences refers to injecting a .yaml file containing all sentences to be transformed into Python strings.

Generating meuDB (

Section 3.2.1) takes the longest time to run, as it relies on Stanza to gather POS tagging information for every word in the full text. We also perform fuzzy string matching on the words to get every possible multi-word interpretation of each entity, which increases dramatically as the amount of sentences increases. However, once it has been generated, it is saved to a JSON file, which is then loaded into memory for subsequent executions, represented by the

loading meuDB phase.

Generating the gsmDB (

Section 3.3.2) uses the learning-based pipeline from StanfordNLP, however still achieves a speedy execution time, with generating our rewritten graphs performs even better, as this is not dependent on any learning-based pipeline.

Generating the

intermediate representation (

Section 3.3 except from

Section 3.3.5) ends up being slower than generating the GSM graphs, which is most likely because the pipeline is being throttled when lemmatising verbs at multiple stages in the pipeline. This is because the pipeline is attempting to lemmatise each single word alone occurring within the text, while the GSM generation via StanfordNLP considers the entire sentences as a whole. We boosted this by using LRU caching mechanism [

72,

73] from

functools, so words that have already been lemmatised can be reused from memory. However, as the number of sentences increase, so does the number of new words. As the other rewriting steps are streamlined through efficient algorithms providing efficient implementations for rule matching and rewriting mechanisms, future works will address better strategies for enhancing the current rewriting step.

Given the plots, all processing steps discussed have a linear time complexity modulo time fluctuations: as all the algorithms used in this paper mainly entail the rewriting of original sentences by reading them from the beginning to the end independently from their representation, the least cost we can pay is comparable to a linear scan of the data representation for each sentence. This then remarks that further improvements over the provided algorithms can be only achieved through decreasing additive and multiplicative constant factors.

At the top end of our tests (highlighted in the red bounding box in

Figure 15), it took on average 59.40 minutes for 200 sentences on a single-threaded machine, and once the meuDB was generated it took 8.84 seconds. In comparison, the time taken to train OpenAI’s GPT-3 model took ≈34 days on 1024 GPUs [

74]. If this were executed on a single-threaded machine like ours, it would take ≈355 years, proving how advantageous our pipeline is. Therefore, our pipeline is correct and more efficient at deriving expected sentence similarity results.

5. Discussion

We now provide some preliminary results that we carried out by analysing the real-world 200 sentences benchmarked in the last experiment (

Section 4.3), while sentences explicitly mentioning Newcastle and traffic scenarios are derived from our Spatiotemporal reasoning dataset (

Figure 13a). For the former dataset, we were able to accurately describe in logical format about 80% of the sentences, while still improving over our previous implementation, the differences with which are narrated below.

5.1. Improving Multi-Word Entity Recognition with Specifications

Our previous solution [

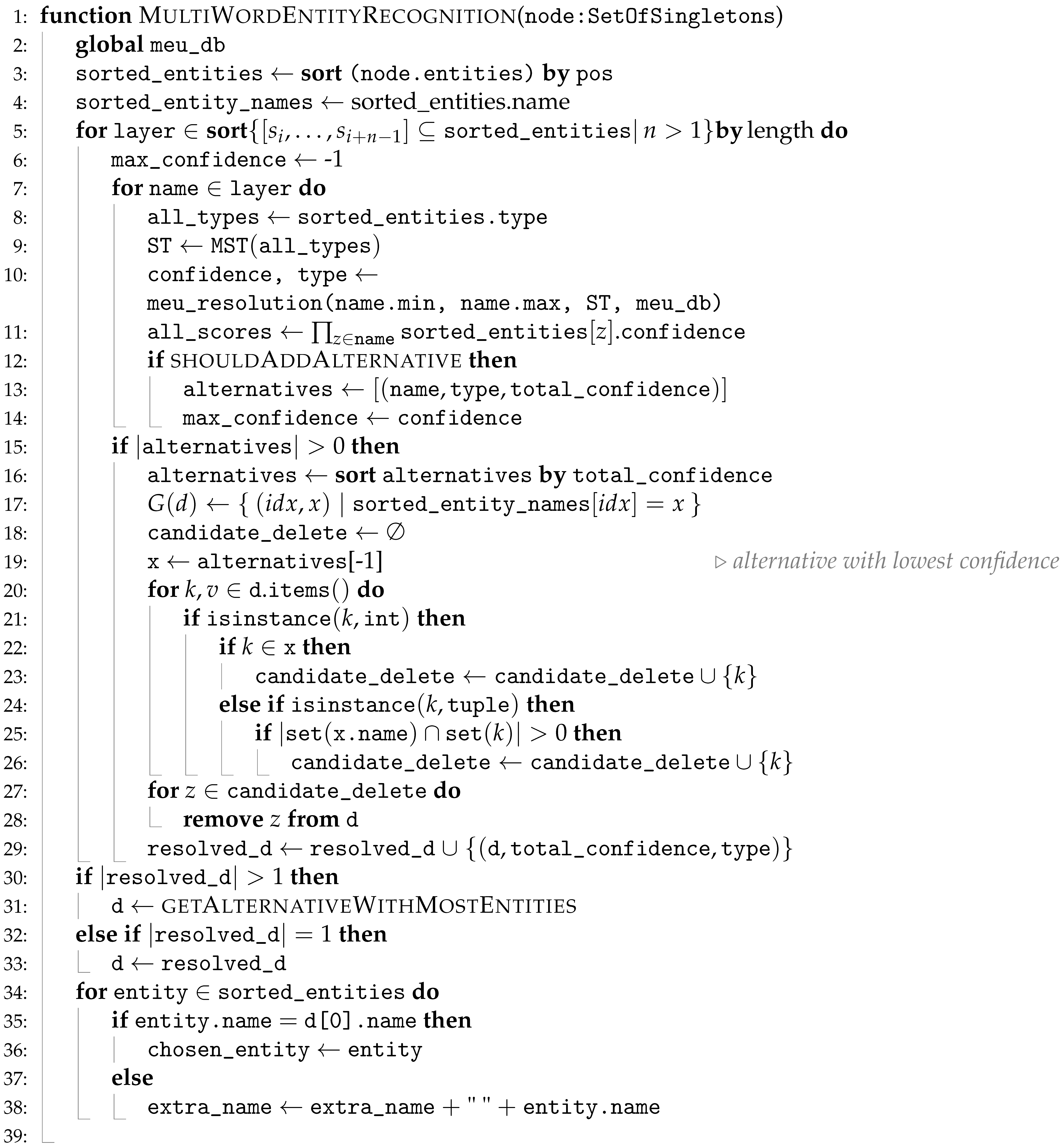

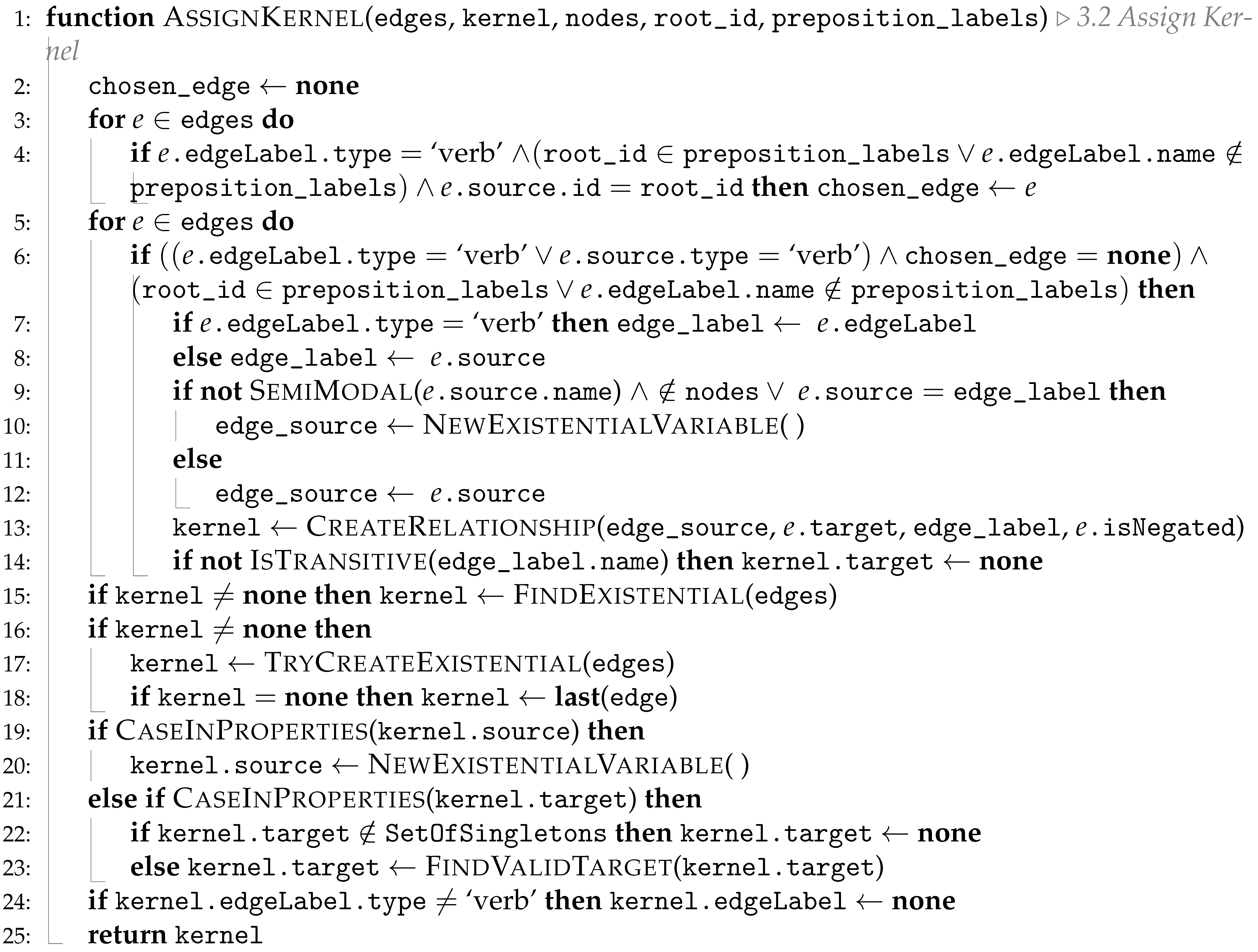

16] chose the most recently resolved entity and did not account for scenarios where multiple resolutions with equal confidence occur. Algorithm 1 rectifies this: on each possible powerset of the

SetOfSingletons entities (Line 5), we check if the current item score is greater than anything previously addressed (Line 12) and, if so, we use this resolution in place of the former. Furthermore, if we have multiple resolutions with the same score, we choose the one with the greatest number of entities (Line 31). For example, the sentence “

you are visiting Griffith Park Observatory” contains a

SetOfSingletons, with entities:

Griffith,

Park, and

Observatory. Two resolutions with equal confidence scores are resolved, the first being

Observatory with an

extra:

Griffith Park, and the second:

Griffith Park Observatory, so based on Line 31, we use the latter as our resolved entity. This is a preliminary measure and could change in future with further testing, but current experiments prove this to be a valid solution.

5.2. Using Short Sentences

We have restricted our current analysis to full-text with no given structure, as in ConceptNet [

18], instead of being parsed as semantic graphs. These can be represented in

propositional logic, in which no universal quantifiers are given, only existential. If we cannot capture propositional logic from these full-texts, then we cannot carry out FOL as the latter is a more expressive logical fragment of the former. In propositional logic, the truth value of a complex sentence depends on the truth values of its simpler components (i.e. propositions) and the connectives that join them. Therefore, using short sentences in logical rewriting is essential because their validity directly influences the validity of larger, more complex sentences constructed from them. If the short sentences are logically sound, the resulting rewritten sentences will also be logically sound and we can ensure that each component of the rewritten sentence is a well formed formula, thereby maintaining logical consistency throughout the process. For example, consider the sentence “

It is busy in Newcastle city centre because there is traffic” This sentence can be broken down into two short sentences: “

It is busy in Newcastle city centre” and “

There is traffic”. These short sentences can be represented as propositions, such as

P and

Q. The original sentence can then be expressed as

. By using short sentences, we ensure that the overall sentence adheres to the rules of propositional logic [

75].

5.3. Handling Incorrect Verbs

We cannot rely on StanfordNLP’s dependency parsing, as it can fail to distinguish the proper interpretation of a sentence [

76], severely impacting our representation when verbs are incorrectly identified.

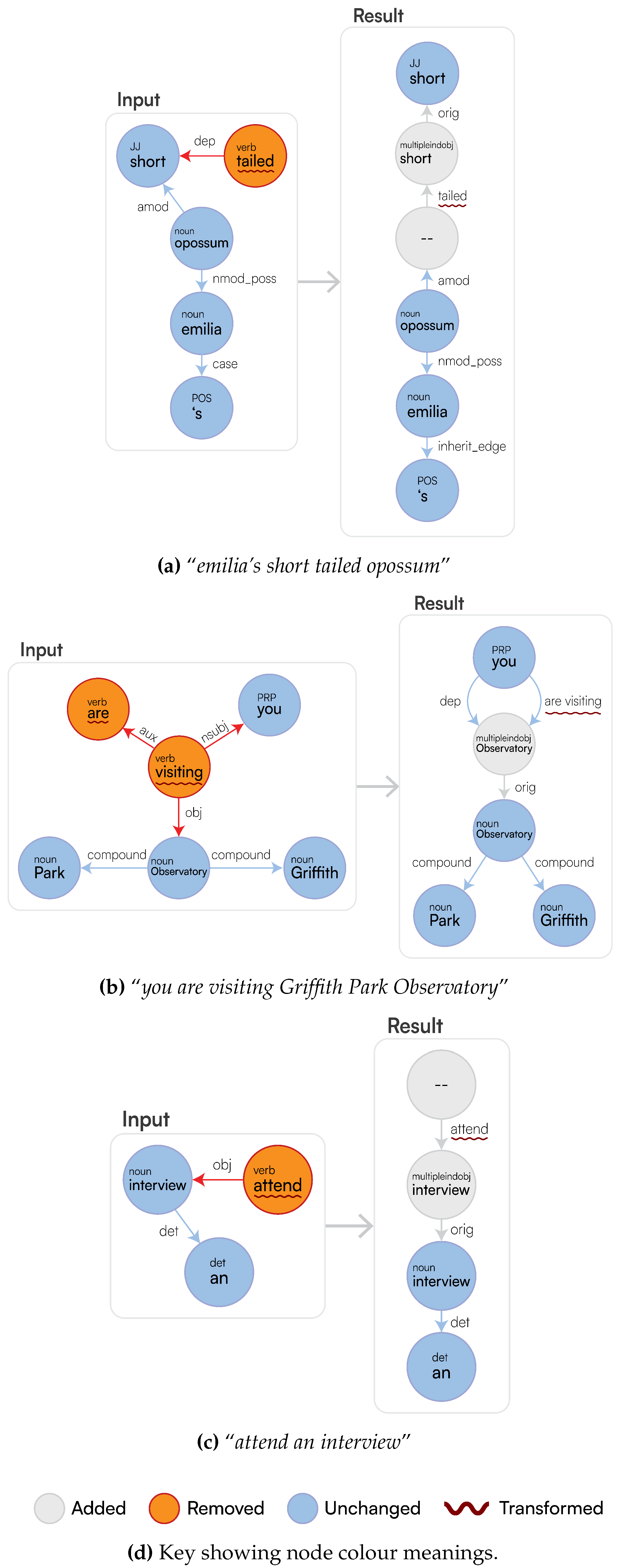

In

Figure 16a, “

short” and “

tailed” should both be identified as

amod’s of

opossum, however we instead get “

tailed” as a verb, rewritten as an edge towards the adjective short. Therefore, given this interpretation, LaSSI rewrites the sentence to:

be(, ?)[SENTENCE:tail(, None)]. We can see that because of “

tailed” being identified as a verb, a kernel is created which is incorrect. However, given the interpretation from the parser, this is the best rewriting we can produce, because we currently do not have a way to differentiate whether “

tailed” should be a verb or not. This analysis can be carried out thanks to our explainability part, we are able to backtrack through the stages of the pipeline to identify that the dependency parsing phase is causing this problem. Given this, we return this partially correct representation of the sentence in logical form:

There are also occasions where our meuDB might produce incorrect identifications of verbs, in

Figure 16b, we can see “

Park” is

correctly identified as a noun from StanfordNLP, however in our Parmenides ontology, it is labelled as a VERB, with the highest confidence of

1.0, and due to our type hierarchy (see

Section 3.2.3), this is chosen as being the correct type. Therefore, we have derived rules from a syntactic point-of-view, to ensure that when a verb type is selected from the meuDB, it is certainly a verb. These are as follows:

So, for the stated example in

Figure 16b, “

Park” cannot be a verb because the parent does

not have a root property attached to it. In another case,

Figure 16c shows the correct identification of “

interview”, but again the meuDB identified it as a verb, however as the node has a

det property attached to it, this means we ignore the resolution and keep it as a noun.

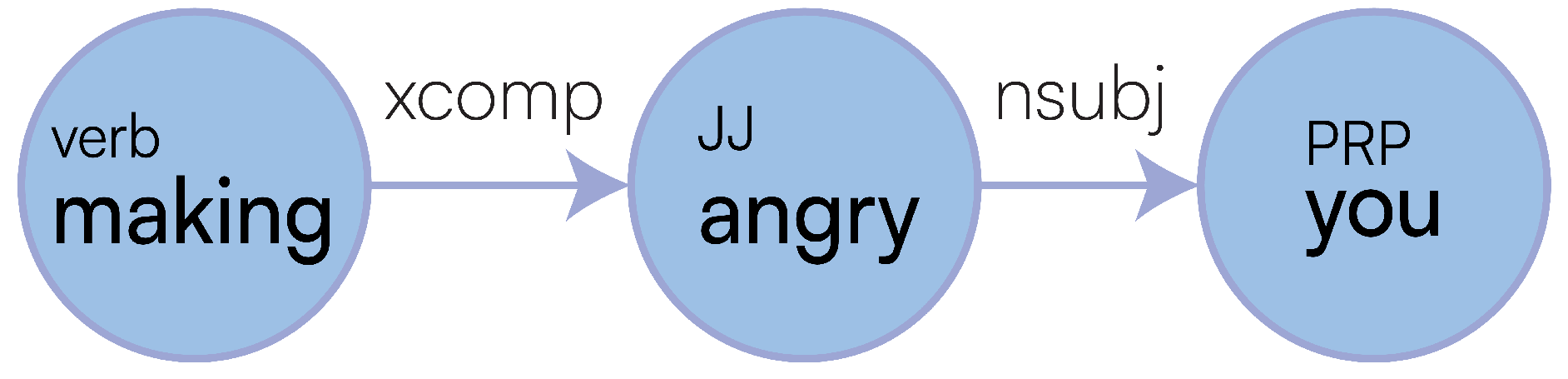

5.4. Handling Incorrect Subject-Verb Relationships

While creating our kernel (detailed in Algorithm A3), we apply post processing on Line 15. Here we check if the created kernel’s target is an adjective, and whether a pronoun or entity is contained within the properties, if so, swap these nodes round so that the representation better reflects the sentence. This happens because the mined ud might wrongly refer a subject to an adjective rather than to the main sentence verb as expected.

For example, the text: “making you angry” is initially rewritten as: make(?, angry)

[PRONOUN: you] at this stage. In

Figure 17 we can see that the verb “

making” is referring to “

angry”, and “

angry” has an

nsubj relation to “

you”, which is incorrect, therefore our post processing fixes this so that “

angry” and “

you” are swapped to become:

make(?, you)[JJ: angry]. This is then represented in logical form as follows:

5.5. Handling Incorrect Spelling (Typos)

Some of the words within the ConceptNet dataset are spelt incorrectly, for example: “be on the interne”. We can assume that the last word in this sentence should be “internet”, and this is found within the meuDB for this sentence. However, it has a matching confidence value with other suggestions for a replacement of this word. In another example: “a capatin”, we could assume that this should be corrected to “captain”, but this is not found in the meuDB, and without further information, we could not be sure if any of the other matches are correct to replace within the sentence. We currently do not have a method to try and identify replacing the words with a possible match, but we do plan to do so by demultiplexing each sentence representation for any ambiguous interpretation of the text. Future works will also attempt to reason probabilistically for determining the most suitable interpretation given the context of the sentence.

5.6. Other Improvements from Previous Pipeline

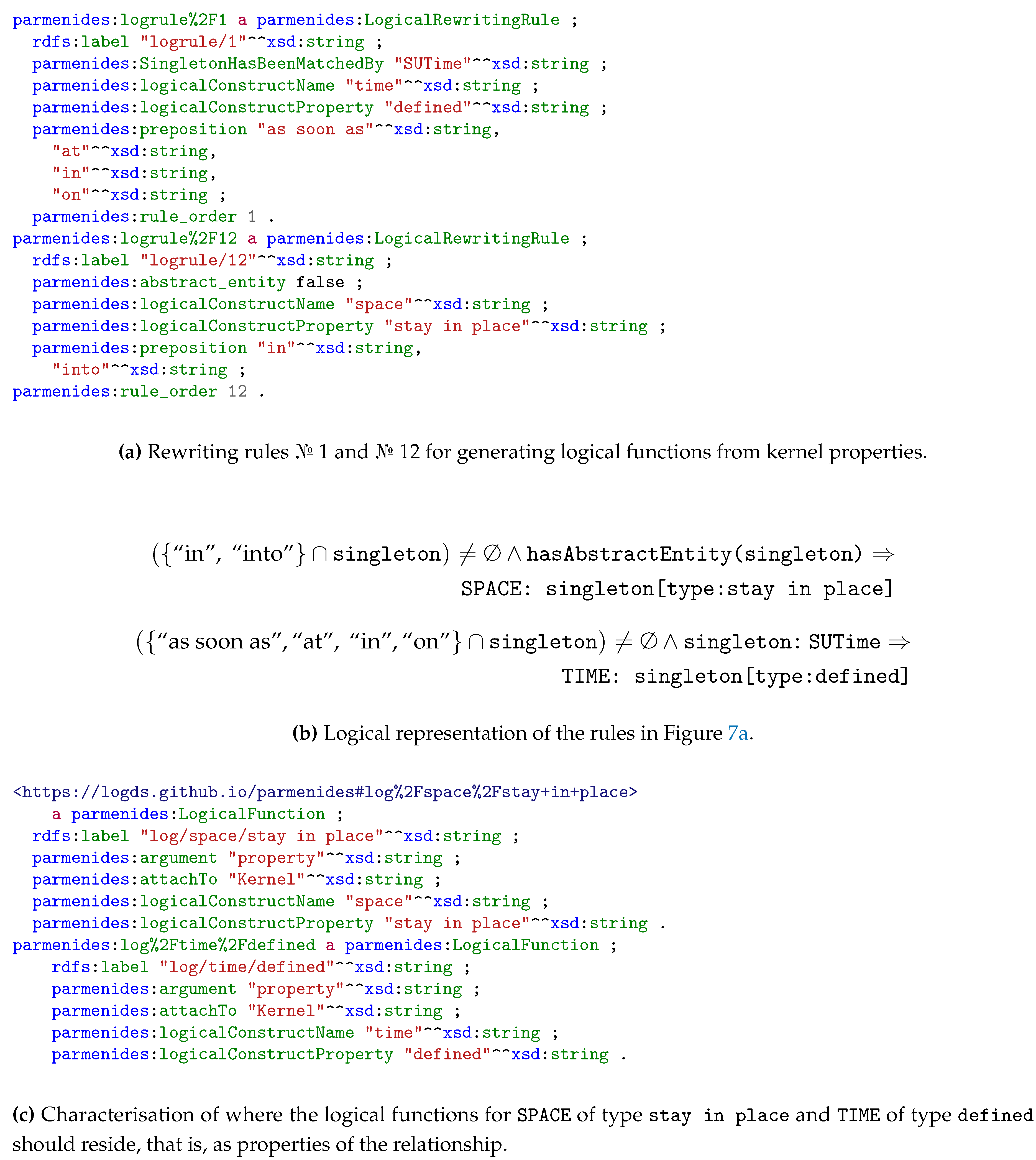

5.6.1. Characterising Entities by Their Logical Function

We also did not categorise entities by their logical function but only by their type. This can be seen in the sentence above, with “

Saturdays” being defined as a

DATE, rather than

TIME in our new pipeline. However, not only do we have improvements to rewriting concerning spatiotemporal information, we are now also handling specifications like causation and aims (to mention a few). For example, the sentence: “

The Newcastle city centre is closed for traffic”, was previously rewritten to:

close(traffic[(case:for)], Newcastle city centre[(amod:busy), (det:The)]), now we have further specification, implementing

AIM_OBJECTIVE to demonstrate specifically

what is closing the Newcastle city centre:

This also relates to a better recognition of whether entities occurring within relationships’ properties actually had to be considered the subject or direct object of a sentence. For the sentence, “

you are visiting Griffith Park Observatory”, this would have been:

visit(you, None) [(GPE:Observatory[(extra:Griffith Park)])], but has been improved to become:

visit(you, Griffith Park Observatory), which is then rendered in logical form as follows:

As a side note, the correct identification of multi-word entities with their specification counterpart (

Griffith Park Observatory rather than

Observatory with

Griffith Park as an extra) was the direct consequence of the discussion in

Section 5.1.

This enhances the contextual information of the sentence, thanks to Algorithm 3.

5.6.2. Dealing with Multiple Distinct Logical Functions

To fully capture the semantic and structural information from the sentences, our pipeline needed to be extended to include rules for scenarios that did not arise in the first investigation. In

Section 3.2.2, we discussed the implementation of

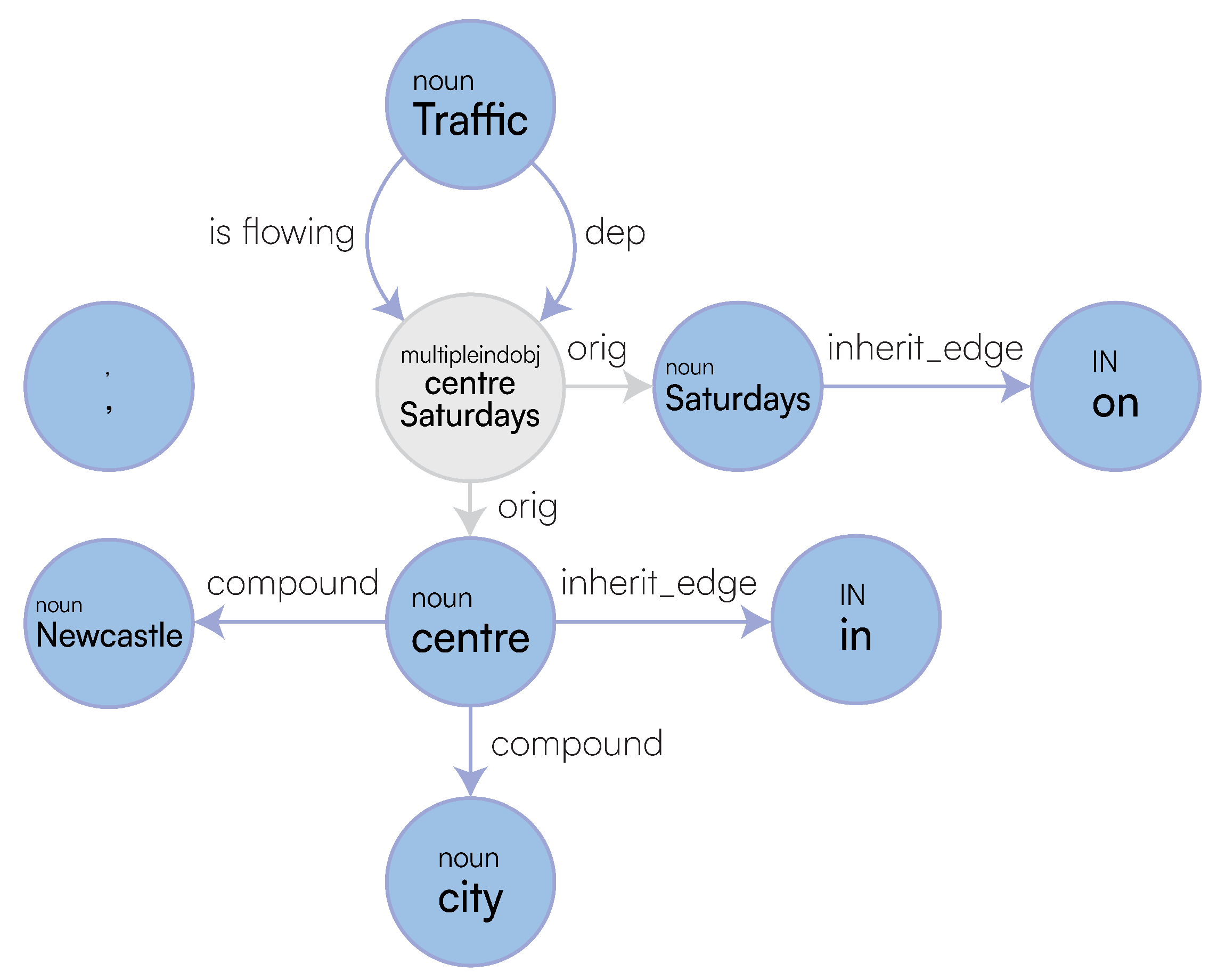

multipleindobj, which was not present beforehand.

Examining

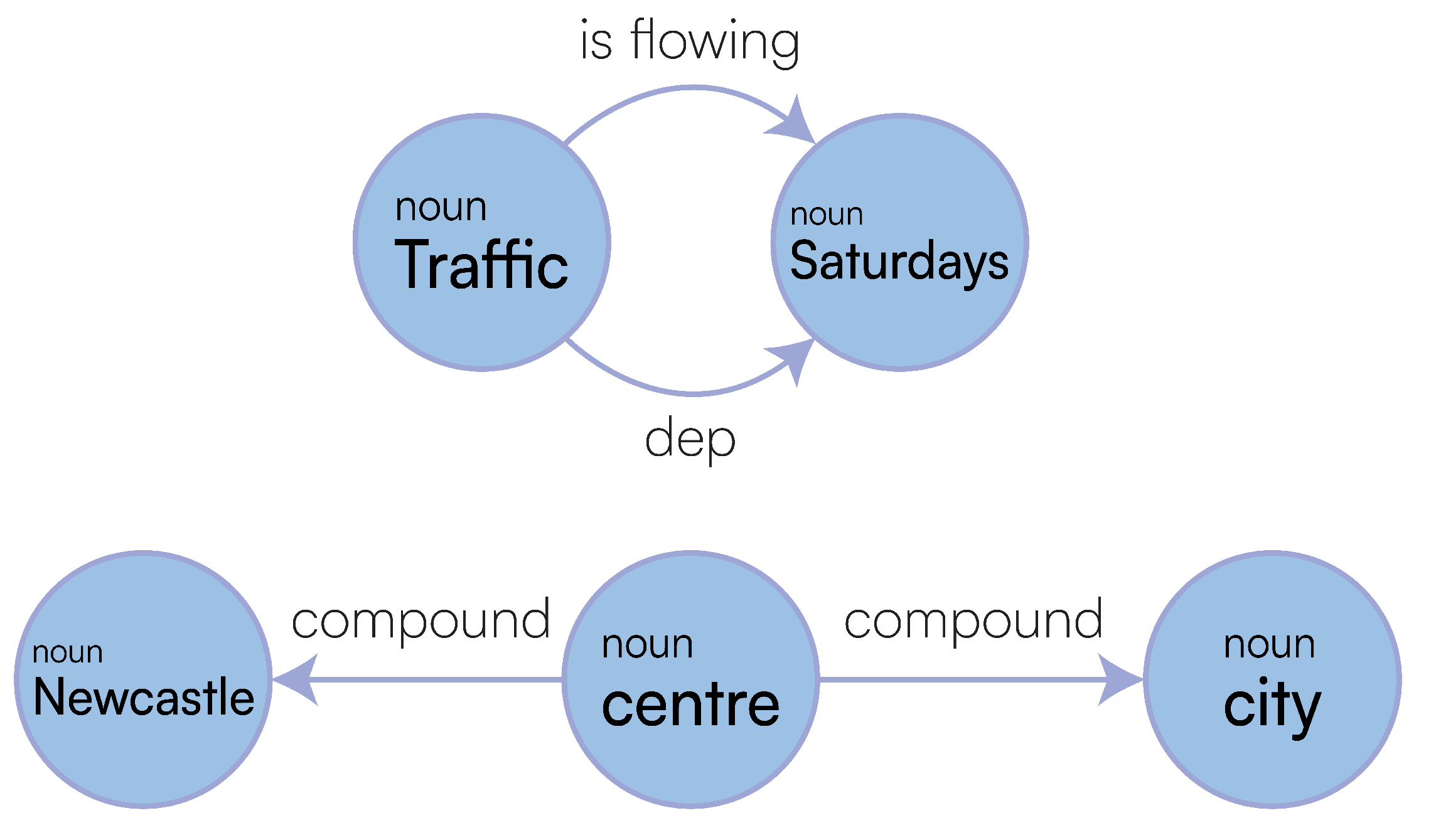

Figure 18, we see no

multipleindobj type present in the graph, and the structure is fundamentally flawed compared to our amended output in

Figure 4, as it is not capturing the n-ary relationships that we need for rewriting. Therefore regardless of the rewriting we do in the LaSSI pipeline, it could never be completely accurate as the initial rewriting was incorrect. Our old pipeline rewrote this to:

flow in(Traffic, None)[DATE:Saturdays], where we can see that “Newcastle city centre” is missing, due to the missing relationships in the graph; compared to what we have now:

flow(Traffic, None)[(TIME:Saturdays[(type:defined)]), (SPACE:Newcastle[(type:stay in place), (extra:city centre)])], which is a sufficiently more accurate representation of the given full-text. This is represented in logical form as follows:

5.6.3. Pronoun Resolution

Pronouns were also not handled; sentences were not properly resolved and would result in an output that was not representative of the original full-text, for example: “

Music that is not classical”, would result in:

nsubj(classical, that)[(GPE:Music)], both not interpreting the pronoun

and mis-categorising “

Music” as a

GPE. This is ameliorated in the new pipeline, discussed in the post-processing in Algorithm 2, to be represented as such:

be(, ?)[(SENTENCE:be(, NOT()))]. For the sentence, “

Music that is not classical”, the relationship passed into Line 29 is:

be(, ?)[(SENTENCE:be(, NOT()8)), (acl_relcl(, be(, NOT()8)))]. To identify whether a replacement should be made, we access the

acl_map using our kernel’s source and target IDs as keys, and if the ID is not present in the map we return the given node. Our map contains one entry: {

5: }. Here, we do not match a value in the source or target of the kernel, however we then loop through the properties, which contains a

SENTENCE, with a source of ID: 5. Thus, we replace the source with the maps’ value of

, and remove the

acl_relcl property, resulting in the new kernel:

be(, ?)[(SENTENCE:be(, NOT()8))].

Music is repeated, however we pertain the ID of the nodes within this final representation, so we can identify that both inclusions of

Music are in fact the same entity. Then, this is rewritten in logical form as follows:

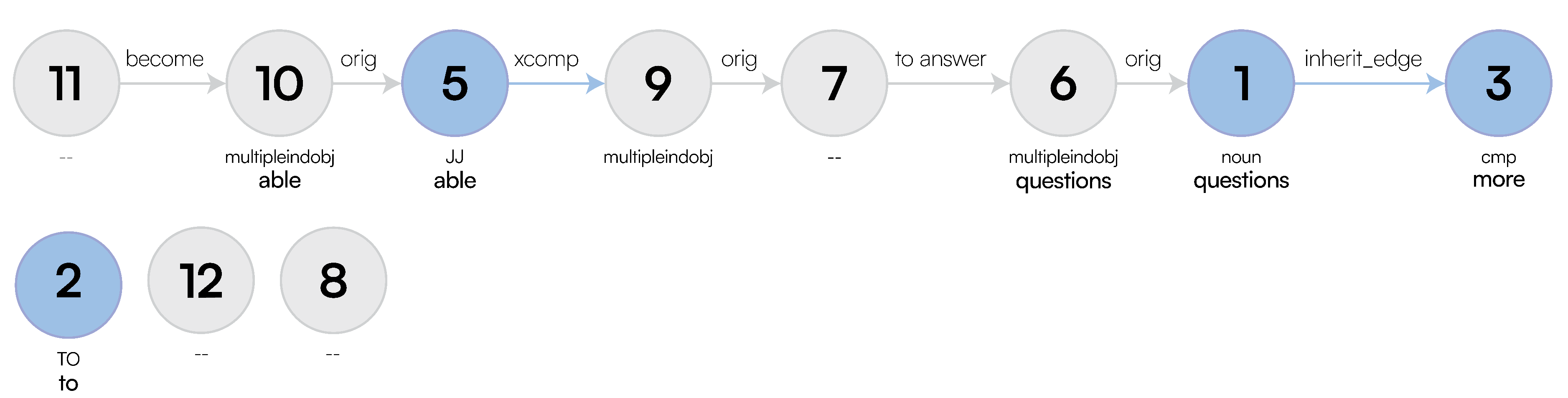

5.6.4. Dealing with Subordinate Clauses

If a given full-text contained one or more dependent sentences, i.e. where two verbs are present, the pipeline would have failed to recognise this, and could only return at most one sentence. This was not a pitfall of the graph structure from GSM, but a needed improvement to the LaSSI pipeline by considering the recursive nature of language as discussed in Algorithm 2. We can show this through two examples, first being, “

attempt to steal someone’s husband”, this was rewritten to:

steal(attempt, None)[(ENTITY:someone), (GPE:husband)], where “

attempt” should be recognised as a verb, and again another misclassification of “

husband” as a

GPE. Our new pipeline recognises the presence of two verbs, and dependency between the two, and correctly rewrites in its intermediate form as:

attempt(?2, None)[(SENTENCE:to steal(?1, husband[(extra:someone[(5:’s)])]))], which is then represented in FOL as:

Second, the full-text, “

become able to answer more questions” contains another

two verbs, however the old pipeline again did not account for this and thus rewrote to:

become(?, None), subsequently it is now represented in its intermediate representation as:

become(?14[(cop:able)], None)[(SENTENCE:to answer(?12, questions[(amod:more)]))], which then becomes the following in logical form:

6. Conclusions and Future Works

This paper offers LaSSI, a hybridly explainable NLP pipeline generating a logical representation for simple and factoid sentences as the one retrievable from common sense and knowledge-based networks. Preliminary results suggest the practicality of MG rewritings by combining dependency parsing, graph rewriting, MEU recognition, as well as semantic post-processing operations. We show that, by exploiting a curated KB having both common-sense knowledge (ABox) and rewriting rules (TBox), we can easily capture the essence of similar sentences while remarking on the limitations of the current state-of-the-art approaches in doing so. Preliminary experiments suggest the inability of transformers to solve problems as closed boolean expressions expressed in natural language and to reason paraconsistently when using cosine similarity metrics [

62].

Currently, out of all the sentences in our dataset, the entities only have at most one preposition contained within the properties, in future datasets we might have more than one. As we have kept the case properties stored in a key-value pair where the key is the float position within the wider sentence, we could eventually determine “complex prepositions”, prepositions formed by combining two or more simple prepositions, within a given sentence. As our intention is to test this pipeline largely on real-world crawled data, future works will further improve the current results of the pipeline by first analysing the remaining sentences from ConceptNet, for then attempting at analysing other more realistic scenarios.

As highlighted in the experiments, the meuDB generation was detrimental to the running time of our pipeline, once it is generated our running times significantly decrease. Therefore, further investigations will be performed into trying to reduce this through a better algorithm so we can ensure the LaSSI pipeline is as efficient as possible in the future.

Multidimensional scaling is the known methodology for representing distances between pairs of objects into points in the Cartesian space [

77,

78], so to derive object embeddings given their pairwise distances. Despite the existance of non-metric solutions [

79,

80], none of these approaches consider arbitrary divergence functions supporting neither the triangular inequality nor the symmetry requirement as the confidence metric used in this paper. The possibility in finding such a technique will streamline the retrieval of similar constituents within the expansion phase by exploiting kNN queries [

81] that can be further streamlined by using vector databases and vector-driven indexing techniques [

82].

Finally, we can clearly see that deep semantic rewriting cannot be encompassed by the latest GQL standards [

43] nor generalised graphs [

35], as both are context-free languages [

83] that cannot take into account contextual information that can be only derivable through semantic information. As these rewriting phases are not driven by FOL inferences, all the inference boils downs to querying a KB to disambiguate the sentence context and semantics, and most human languages are context-sensitive; this postulates that further automating and streamlining the rewriting steps in

Section 3.3.3,

Section 3.3.4, and

Section 3.3.5 shall require the definition a context-sentitive query language, which is currently missing from current database literature. All the remaining rewriting steps were encoded through context-free languages. Future works shall investigate on the appropriateness of this language and whether this can be characterised through a straightforward algorithmic extension of GGG.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B.; methodology, O.R.F. and G.B.; software, O.R.F. and G.B; validation, O.R.F.; formal analysis, O.R.F.; investigation, O.R.F. and G.B.; resources, G.B.; data curation, O.R.F.; writing—original draft preparation, O.R.F.; writing—review and editing, O.R.F., G.B.; visualization, O.R.F.; supervision, G.B., G.M.; project administration, G.B.; funding acquisition, G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.