Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

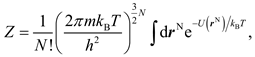

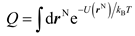

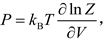

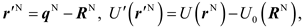

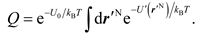

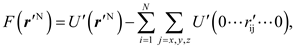

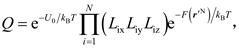

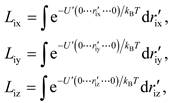

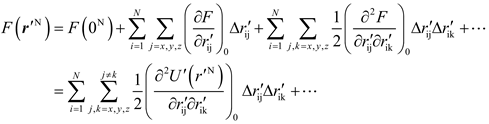

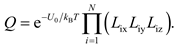

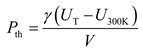

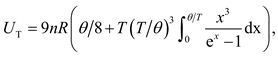

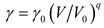

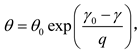

2. Calculation Method

3. Results and Discussion

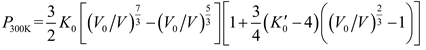

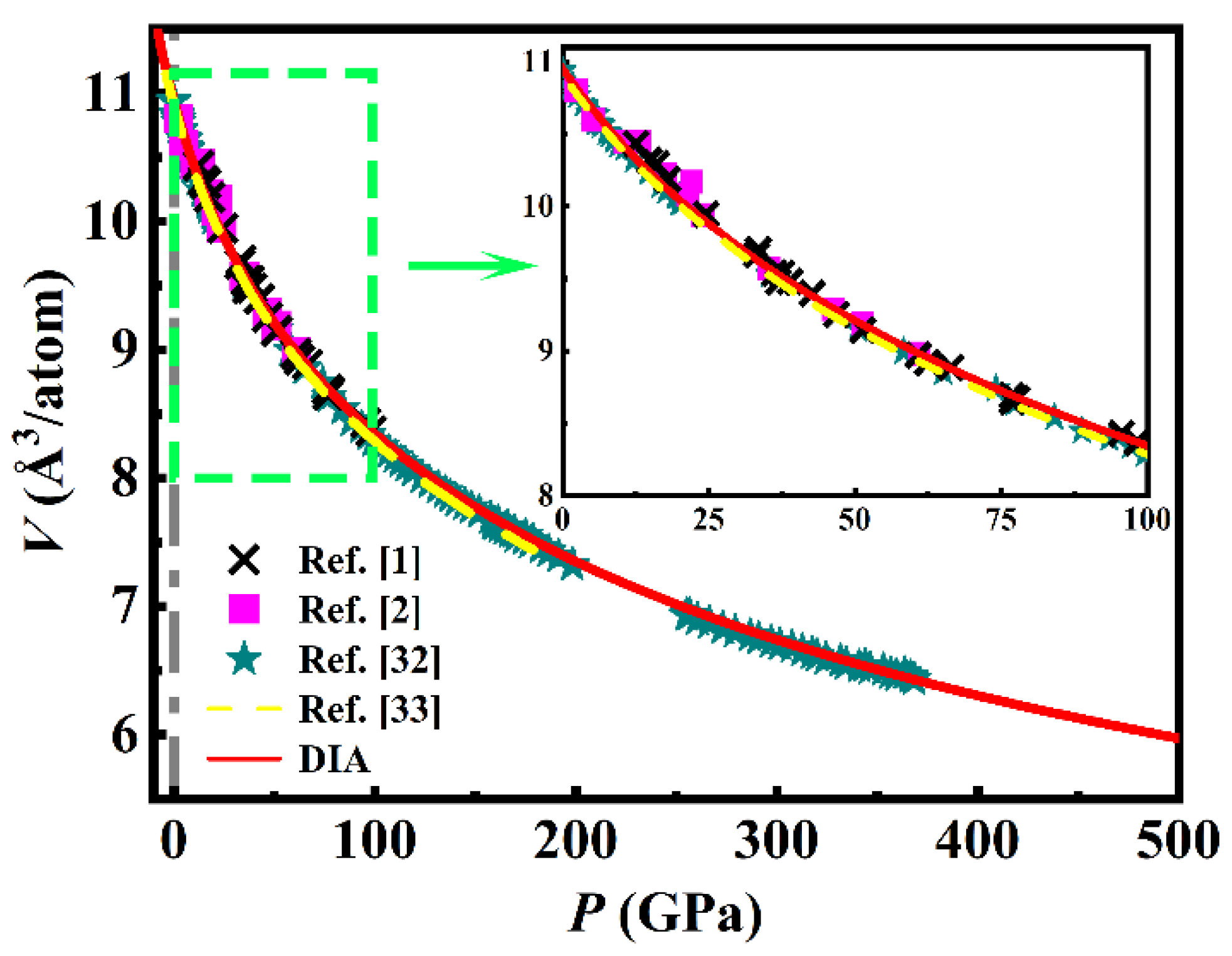

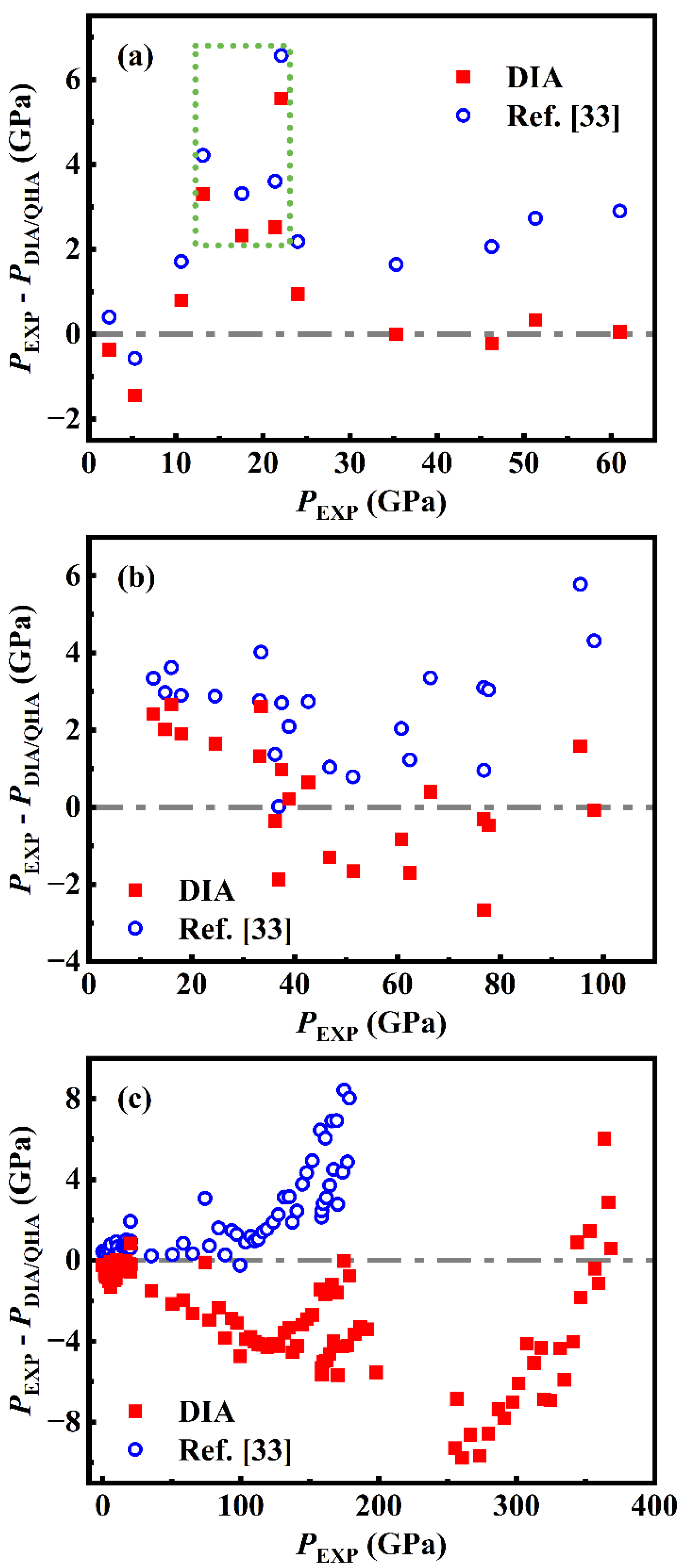

3.1. The Room-Temperature Isotherm

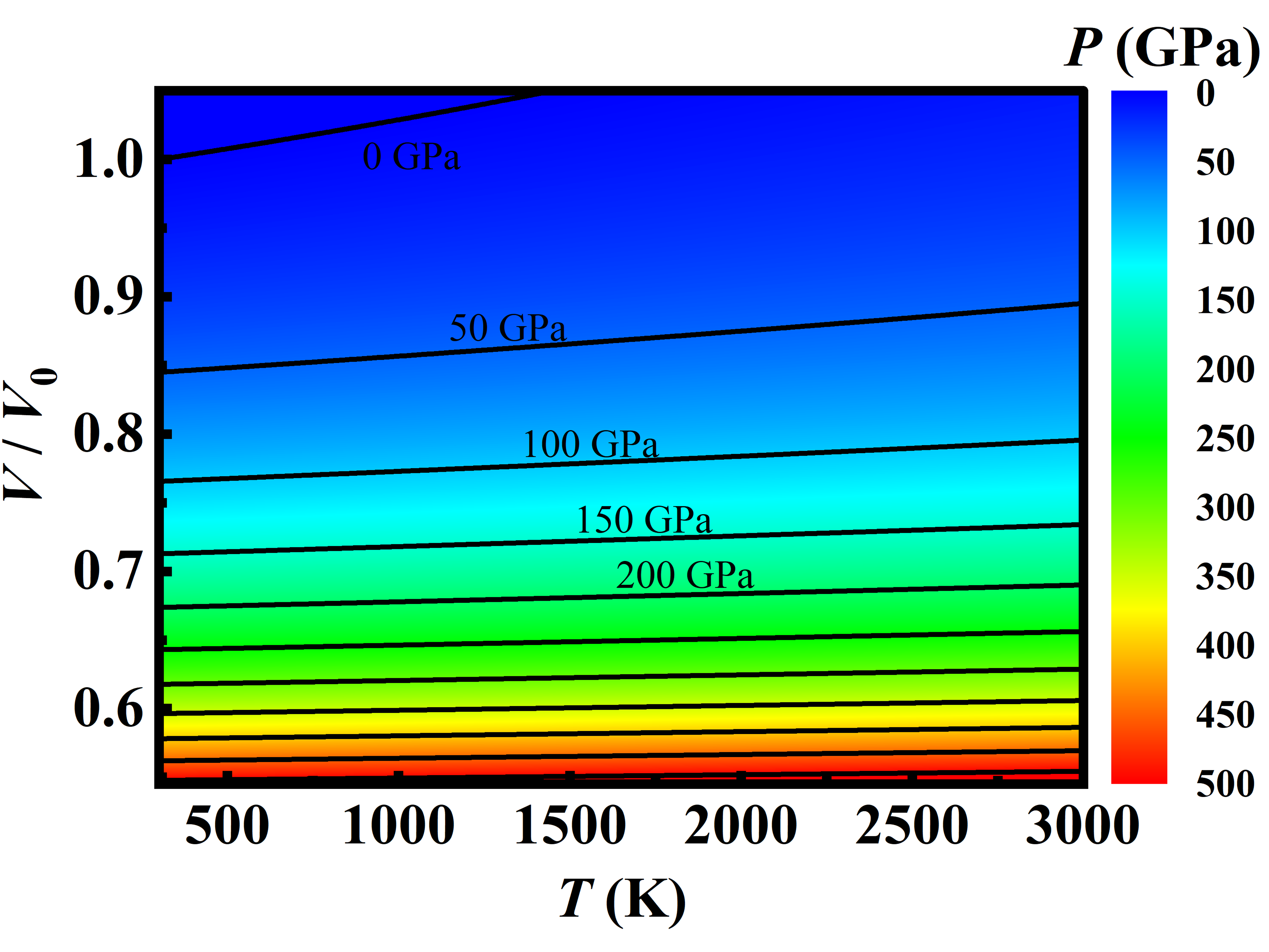

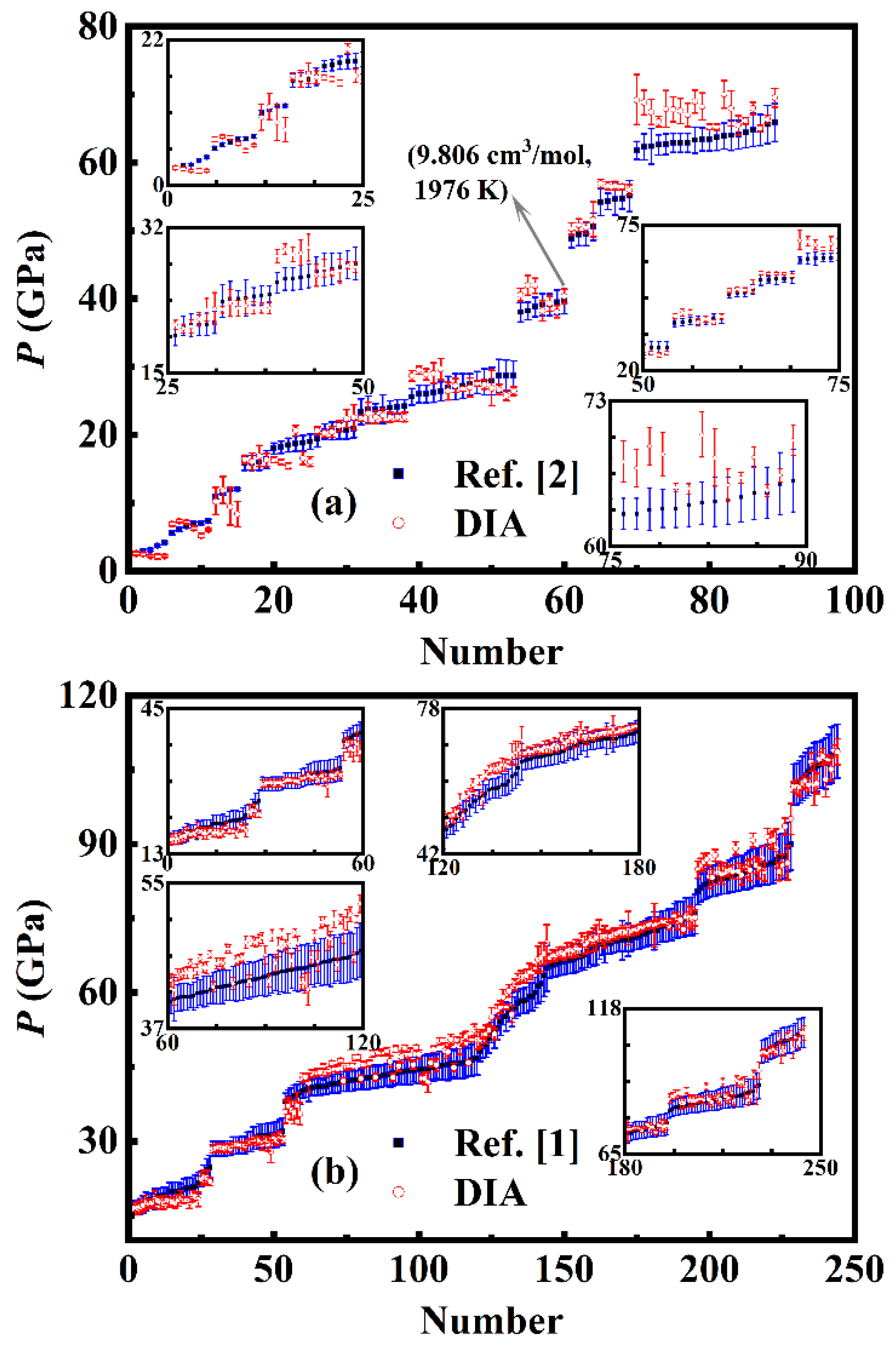

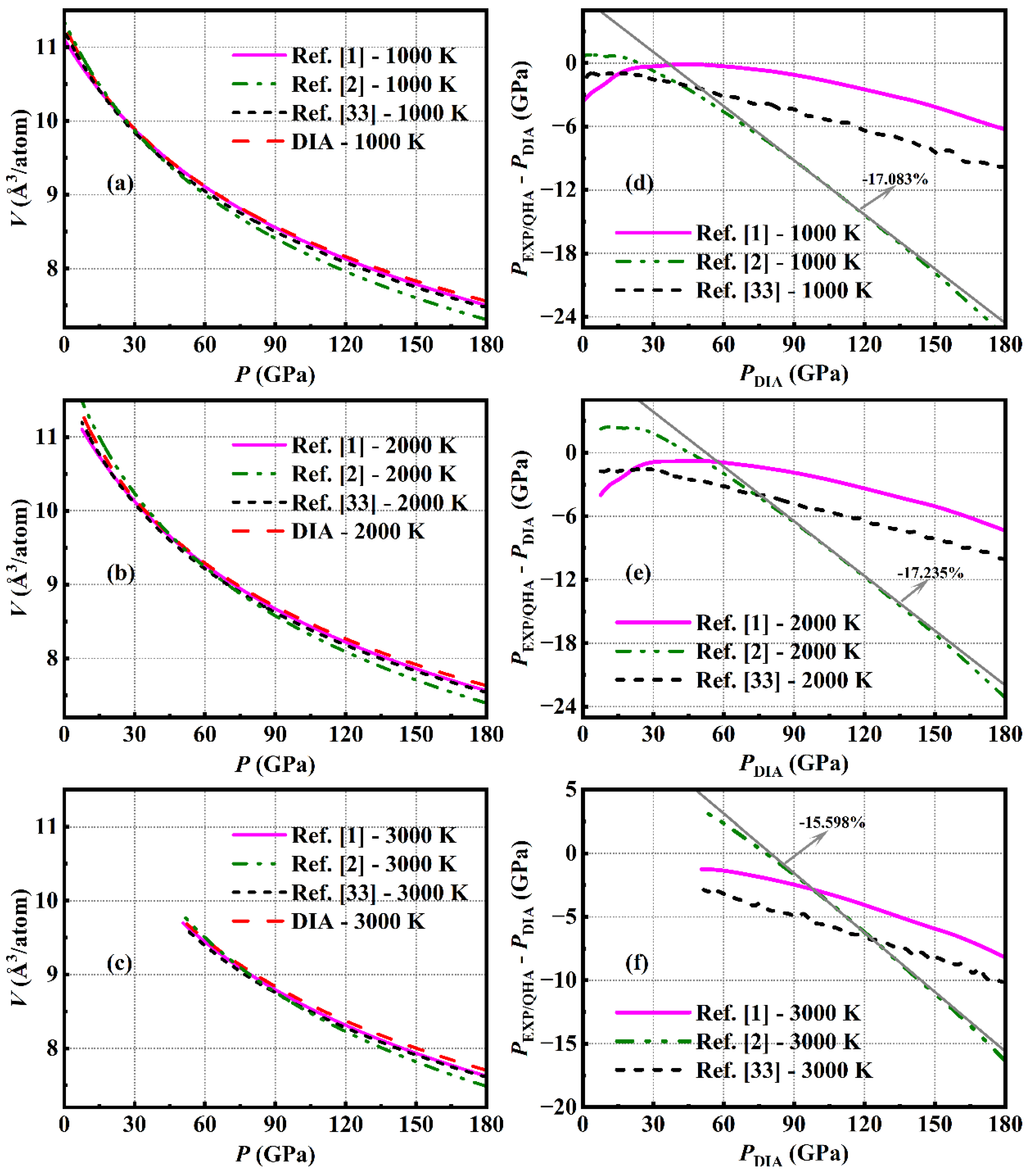

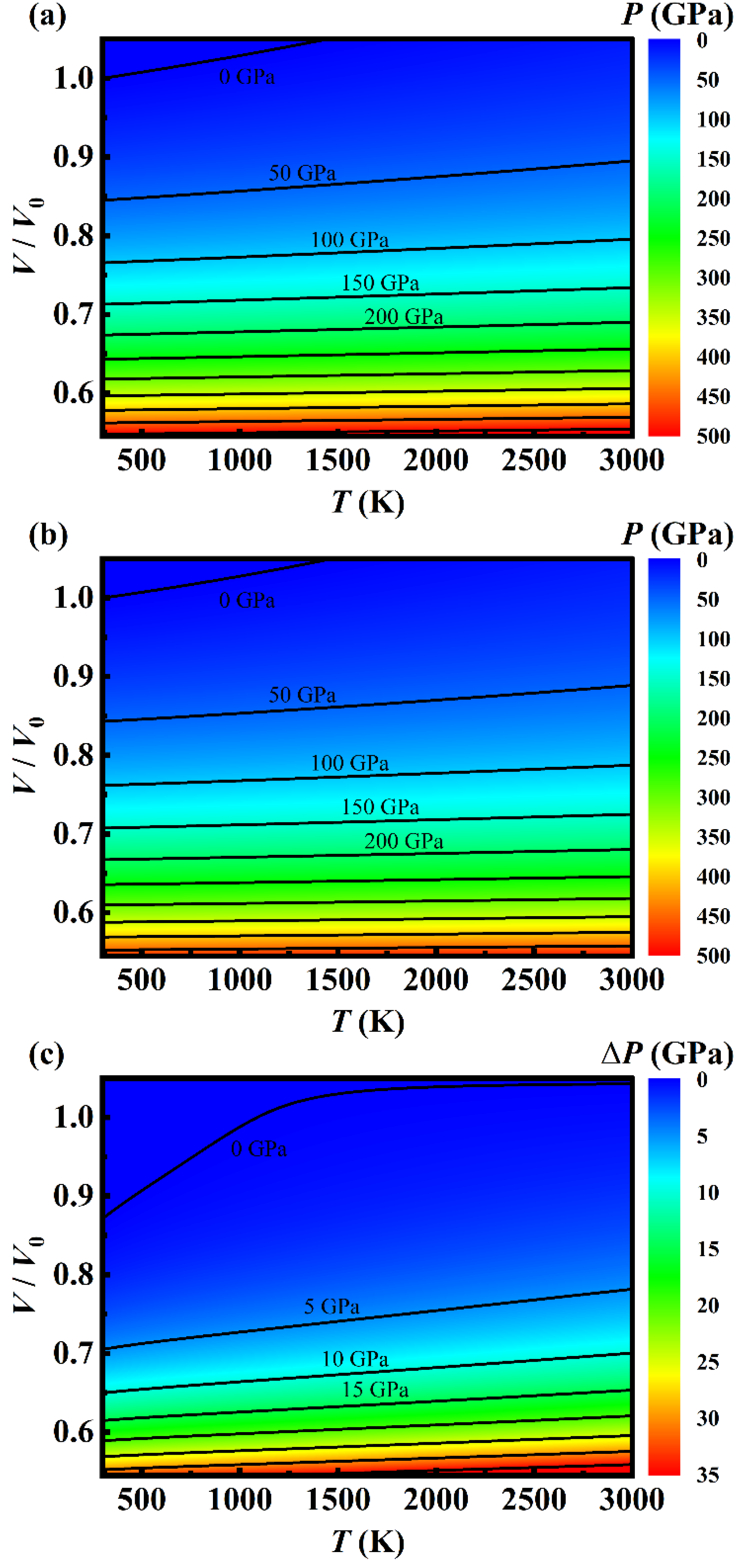

3.2. The High-Temperature Isotherms

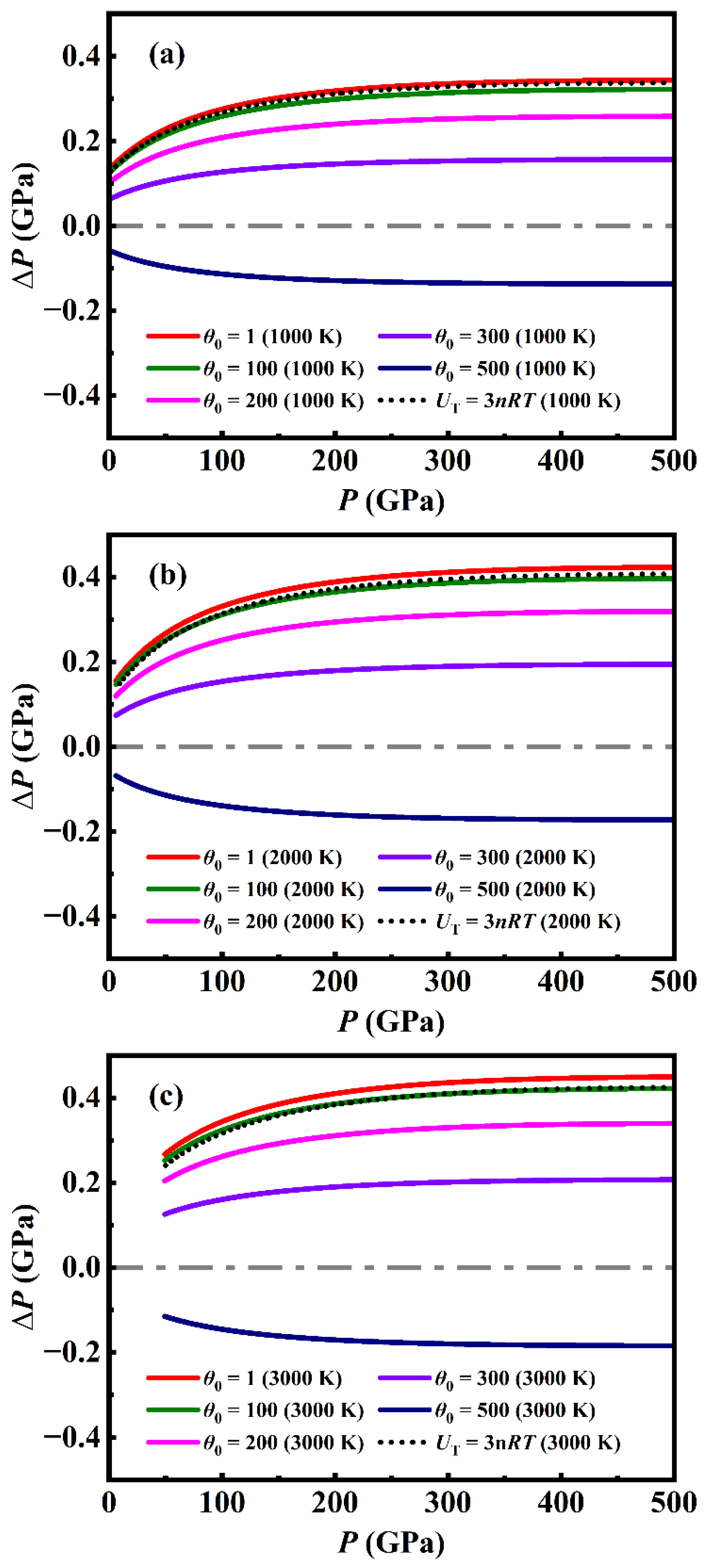

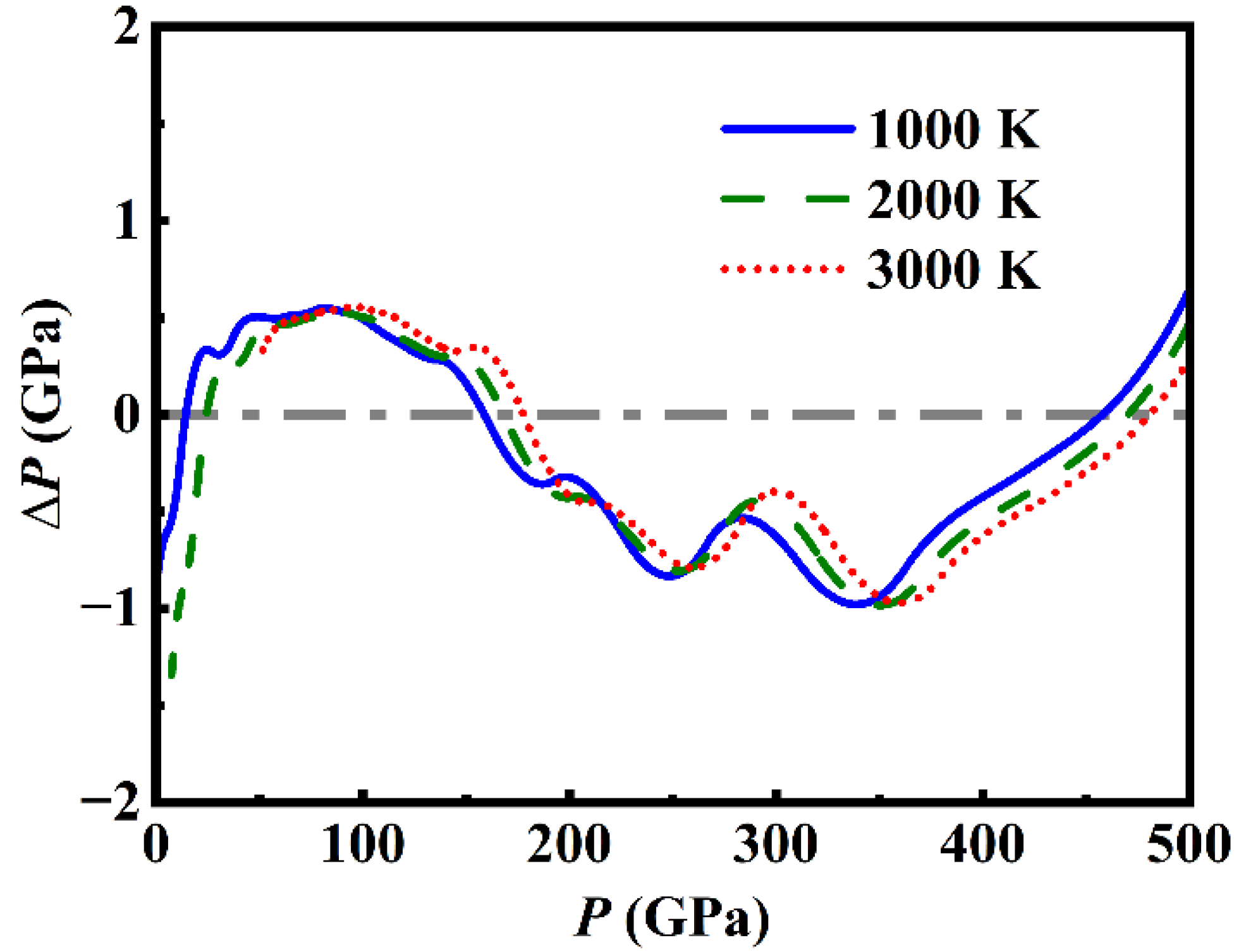

3.3. The Analytical EOS

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pigott, J.S.; Ditmer, D.A.; Fischer, R.A.; Reaman, D.M.; Hrubiak, R.; et al. High-pressure, high-temperature equations of state using nanofabricated controlled-geometry Ni/SiO2/Ni double hot-plate samples. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.J.; Danielson, L.; Righter, K.; Seagle, C.T.; Wang, Y.; et al. High pressure effects on the iron–iron oxide and nickel–nickel oxide oxygen fugacity buffers. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009, 286, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, B.; Wentzcovitch, R.M.; De Gironcoli, S.; Baroni, S. High-pressure lattice dynamics and thermoelasticity of MgO. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 8793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togo, A.; Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 2015, 108, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoja, J.; Reilly, A.M.; Tkatchenko, A. First-principles modeling of molecular crystals: structures and stabilities, temperature and pressure. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2017, 7, e1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.-C.; Ning, B.-Y.; Ming, C.; Weng, T.-C.; Ning, X.-J. How accurate for phonon models to predict the thermodynamics properties of crystals. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2020, 33, 085901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, E.; Stixrude, L.; Cohen, R.E. Thermal properties of iron at high pressures and temperatures. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 53, 8296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.E.; Gülseren, O. Thermal equation of state of tantalum. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 63, 224101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannarelli, C.; Alfe, D.; Gillan, M. The particle-in-cell model for ab initio thermodynamics: implications for the elastic anisotropy of the Earth’s inner core. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2003, 139, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Xi, F.; Bi, Y.; Xu, J.A.; Geng, H.; et al. Ab initio thermodynamics beyond the quasiharmonic approximation: W as a prototype. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 014301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Classical mean-field approach for thermodynamics: Ab initio thermophysical properties of cerium. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, R11863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhang, X. Calculated equation of state of Al, Cu, Ta, Mo, and W to 1000 GPa. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ahuja, R.; Johansson, B. Reduction of shock-wave data with mean-field potential approach. J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 92, 6616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, Y.W.Z.-K.L.L.-Q.C.L.B.D.; et al. Mean-field potential calculations of shock-compressed porous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 054110. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, B.-Y.; Gong, L.-C.; Weng, T.-C.; Ning, X.-J. Efficient approaches to solutions of partition function for condensed matters. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2020, 33, 115901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Shi, L.-Q.; Wang, N.; Zhang, H.-F.; Peng, S.-M. Equation of state of Iridium: from insight of ensemble theory. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2022, 34, 465702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.-Y.; Ning, B.-Y.; Zhang, H.-F.; Ning, X.-J. Equation of state for tungsten obtained by direct solving the partition function. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.-Y.; Ning, B.-Y.; Zhang, H.-F.; Ning, X.-J. Hydrostatic Equation of State of bcc Bi by Directly Solving the Partition Function. Metals 2024, 14, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-P.; Ning, B.-Y.; Gong, L.-C.; Weng, T.-C.; Ning, X.-J. A New model to predict optimum conditions for growth of 2D materials on a substrate. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.-Y.; Ning, X.-J. Pressure-induced structural phase transition of vanadium: A revisit from the perspective of ensemble theory. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2022, 34, 425404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.-Y. Pressure-induced structural phase transitions of zirconium: an ab initio study based on statistical ensemble theory. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2022, 34, 505402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, B.-Y.; Zhang, L.-Y. An ab initio study of structural phase transitions of crystalline aluminium under ultrahigh pressures based on ensemble theory. Comput. Mater. Sci 2023, 218, 111960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Mao, H.-K.; Shu, J.; Hu, J. P-V-T equation of state of magnesiowüstite (Mg0.6Fe0.4)O. Phys. Chem. Miner. 1992, 18, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, I.; Rigden, S.M. Analysis of P-V-T data:constraints on the thermoelastic properties of high-pressure minerals. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 1996, 96, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, A.; Loubeyre, P.; Occelli, F.; Mezouar, M.; Dorogokupets, P.I.; et al. Quasihydrostatic equation of state of iron above 2 Mbar. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 215504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci 1996, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöchl, P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkhorst, H.J.; Pack, J.D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirao, N.; Akahama, Y.; Ohishi, Y. Equations of state of iron and nickel to the pressure at the center of the Earth. Matter Radiat. Extremes 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.-Y.; Hu, C.-E.; Cai, L.-C.; Jing, F.-Q. Ab initio study of lattice dynamics and thermal equation of state of Ni. Physica B 2012, 407, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccato, S.; Torchio, R.; Kantor, I.; Morard, G.; Anzellini, S.; et al. The Melting Curve of Nickel Up to 100 GPa Explored by XAS. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 2017, 122, 9921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, F. Elasticity and constitution of the Earth's interior. J. Geophys. Res. 1952, 57, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knacke, O.; Kubaschewski, O.; Hesselmann, K. , Thermochemical Properties of Inorganic Substances, 2nd ed. ed. (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1991).

| P (GPa) | 300 K | 500 K | 1000 K | 1500 K | 2000 K | 2500 K | 3000 K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0001 | 10.9524 | 11.046 | 11.3055 | 11.6181 | - | - | - |

| 10 | 10.4413 | 10.5118 | 10.7087 | 10.9196 | 11.1518 | - | - |

| 20 | 10.0454 | 10.1001 | 10.2462 | 10.4083 | 10.5905 | - | - |

| 30 | 9.7252 | 9.7727 | 9.8944 | 10.022 | 10.1592 | 10.3093 | - |

| 40 | 9.4478 | 9.4888 | 9.5948 | 9.7067 | 9.8236 | 9.9458 | - |

| 50 | 9.2108 | 9.2467 | 9.3388 | 9.4348 | 9.5355 | 9.6418 | - |

| 60 | 9.0012 | 9.0332 | 9.1153 | 9.2004 | 9.2888 | 9.3809 | 9.4773 |

| 70 | 8.8128 | 8.8418 | 8.9158 | 8.9923 | 9.0716 | 9.1539 | 9.2391 |

| 80 | 8.6424 | 8.6687 | 8.736 | 8.8057 | 8.8775 | 8.9516 | 9.0282 |

| 90 | 8.4875 | 8.5117 | 8.5735 | 8.6369 | 8.7023 | 8.7698 | 8.8395 |

| 100 | 8.3459 | 8.3682 | 8.425 | 8.4834 | 8.5435 | 8.6053 | 8.6688 |

| 110 | 8.2153 | 8.236 | 8.2887 | 8.3428 | 8.3981 | 8.455 | 8.5135 |

| 120 | 8.0941 | 8.1133 | 8.1623 | 8.2127 | 8.2643 | 8.3171 | 8.3712 |

| 130 | 7.9808 | 7.9987 | 8.0445 | 8.0917 | 8.14 | 8.1894 | 8.24 |

| 140 | 7.8748 | 7.8914 | 7.9341 | 7.9783 | 8.0238 | 8.0702 | 8.1177 |

| 150 | 7.7756 | 7.7913 | 7.8313 | 7.8725 | 7.9148 | 7.9583 | 8.0031 |

| 160 | 7.6821 | 7.6973 | 7.7353 | 7.7741 | 7.8137 | 7.8542 | 7.8957 |

| 170 | 7.5932 | 7.608 | 7.6446 | 7.6816 | 7.7191 | 7.7573 | 7.7962 |

| 180 | 7.5083 | 7.5226 | 7.5581 | 7.5937 | 7.6297 | 7.6662 | 7.7032 |

| 190 | 7.427 | 7.4407 | 7.4752 | 7.5096 | 7.5443 | 7.5794 | 7.615 |

| 200 | 7.3501 | 7.3632 | 7.3959 | 7.429 | 7.4625 | 7.4964 | 7.5306 |

| 210 | 7.2779 | 7.2901 | 7.3212 | 7.3526 | 7.3844 | 7.4167 | 7.4496 |

| 220 | 7.2092 | 7.2208 | 7.2502 | 7.2801 | 7.31 | 7.3412 | 7.3724 |

| 230 | 7.1434 | 7.1545 | 7.1826 | 7.211 | 7.24 | 7.2693 | 7.2991 |

| 240 | 7.0798 | 7.0905 | 7.1174 | 7.1448 | 7.1726 | 7.2007 | 7.2293 |

| 250 | 7.0181 | 7.0284 | 7.0543 | 7.0808 | 7.1076 | 7.1348 | 7.1624 |

| 260 | 6.9582 | 6.9681 | 6.9932 | 7.0188 | 7.0448 | 7.0711 | 7.0978 |

| 270 | 6.9005 | 6.9099 | 6.9339 | 6.9587 | 6.9839 | 7.0095 | 7.0353 |

| 280 | 6.8454 | 6.8543 | 6.8773 | 6.9009 | 6.925 | 6.9497 | 6.9748 |

| 290 | 6.7924 | 6.8011 | 6.8232 | 6.8458 | 6.8689 | 6.8924 | 6.9164 |

| 300 | 6.7415 | 6.7499 | 6.7713 | 6.7931 | 6.8152 | 6.8378 | 6.8607 |

| 310 | 6.6923 | 6.7005 | 6.7213 | 6.7424 | 6.7638 | 6.7855 | 6.8076 |

| 320 | 6.6445 | 6.6527 | 6.6731 | 6.6936 | 6.7143 | 6.7353 | 6.7566 |

| 330 | 6.5981 | 6.6061 | 6.6261 | 6.6462 | 6.6664 | 6.6869 | 6.7075 |

| 340 | 6.5528 | 6.5607 | 6.5803 | 6.6 | 6.6198 | 6.6398 | 6.6599 |

| 350 | 6.5087 | 6.5164 | 6.5357 | 6.555 | 6.5744 | 6.5939 | 6.6135 |

| 360 | 6.4657 | 6.4732 | 6.4921 | 6.511 | 6.53 | 6.5491 | 6.5684 |

| 370 | 6.424 | 6.4313 | 6.4496 | 6.468 | 6.4866 | 6.5054 | 6.5242 |

| 380 | 6.3836 | 6.3907 | 6.4085 | 6.4264 | 6.4445 | 6.4627 | 6.4811 |

| 390 | 6.3444 | 6.3513 | 6.3686 | 6.386 | 6.4036 | 6.4213 | 6.4392 |

| 400 | 6.3063 | 6.313 | 6.3299 | 6.3469 | 6.364 | 6.3812 | 6.3986 |

| 410 | 6.2693 | 6.2758 | 6.2922 | 6.3088 | 6.3255 | 6.3423 | 6.3592 |

| 420 | 6.2331 | 6.2395 | 6.2555 | 6.2717 | 6.288 | 6.3044 | 6.3209 |

| 430 | 6.1979 | 6.2041 | 6.2198 | 6.2355 | 6.2514 | 6.2674 | 6.2836 |

| 440 | 6.1635 | 6.1696 | 6.1849 | 6.2003 | 6.2158 | 6.2314 | 6.2472 |

| 450 | 6.1299 | 6.1359 | 6.1508 | 6.1659 | 6.181 | 6.1963 | 6.2117 |

| 460 | 6.0971 | 6.103 | 6.1176 | 6.1323 | 6.1471 | 6.1621 | 6.1771 |

| 470 | 6.065 | 6.0707 | 6.085 | 6.0994 | 6.1139 | 6.1286 | 6.1433 |

| 480 | 6.0336 | 6.0391 | 6.0531 | 6.0672 | 6.0815 | 6.0958 | 6.1103 |

| 490 | 6.0027 | 6.0082 | 6.0219 | 6.0357 | 6.0496 | 6.0637 | 6.0779 |

| 500 | 5.9725 | 5.9778 | 5.9912 | 6.0048 | 6.0185 | 6.0323 | 6.0462 |

| DIA | Campbell et al. [2] | Pigott et al. [1] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| V0 (Å3/atom) | 10.909 | 10.939 | 10.926 |

| K0 (GPa) | 200.402 | 179(3) | 201(6) |

| K0´ | 4.637 | 4.3(0.2) | 4.4(0.3) |

| θ0 (K) | / | 415 | 415 |

| γ0 | 2.025 | 2.50(0.06) | 1.98(0.08) |

| q | 0.772 | 1 | 1.3(0.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).