1. Introduction

The study of the gut microbiome has shown a significant impact on the development, progression, and control of blood pressure, the gut synthesis of short chain fatty acids (SCFA) seems to be crucial for the activation of a variety of kidney receptors that can regulate blood pressure in different directions. Several studies have confirmed the link between the gut microbiome and cardiovascular diseases, with some studies establishing causative relationships [

1,

2]. In a cohort study, Sun et., al established a connection between the gut microbiome and hypertension observing a decreased diversity and specific microorganisms associated with high blood pressure with signs of a compromised gut barrier, gut dysbiosis and inflammation [

3].

Although genetics, the environment, diet and the gut microbiome are crucial to hypertension’s development, the impact of age remains as the main risk factor for its development with up-to 65% of older adults being hypertensive in many regions of the world, hence the relationship between the gut microbiome and hypertension increases as we age. The gut microbiome’s diversity and richness declines after 60 years of age [

4], but the definitive characteristics of the gut microbiome in older adults have only been studied for certain populations [

5], but it requires to be more comprehensively depicted to understand the influence of the environment, diet, host genetics, and hypertension [

6,

7].

More recently, the scientific community has uncovered that gut bacteria can affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antihypertensive medications through metabolic enzymes that can reduce drug bioavailability prior to drug absorption [

8]. But also, antihypertensive drugs can alter the gut microbiome’s composition, Yang T et. al. observed an enrichment of the

Coprococcus genus in patients with a poor response to ACE inhibitors that differed in geographical ancestry [

9]. Similarly, the reduction of systolic blood pressure after captopril and losartan administration reduces gut dysbiosis in hypertensive rats [

10], while diuretics combined with beta blockers and ACE-inhibitors have been associated with the enrichment of

Roseburia [

11].

Hypertension control is key to decrease cardiovascular mortality as the leading cause of death worldwide, but the complexity of diagnosing and managing hypertension contributes to its high prevalence despite the existence of over 65 different antihypertensive drugs. Most of the current investigations have defined the role of the gut microbiome in hypertension by comparing patients with normotensive individuals, and little is known of the impact of hypertension control on the potential benefits for the gut microbiome. Moreover, the identification of microbes influencing blood pressure has accumulated information for certain populations, but the high variability and the apparent influence of the environment and genetics of the trait highlights the importance of validating these associations in larger study groups from different geographic ancestries. Here, we describe the diversity and abundance of the gut microbiome in admixed older adults focusing on hypertension control. Our results are one of the first to describe the gut microbiome of elderly hypertensive according to their control on blood pressure.

2. Results

We investigated the gut microbiome in 240 patients, 113 males and 127 females between 60 and 95 years all under antihypertensive treatment for at least 4 years. Other prescribed drugs included lipid lowering medication (36%), proton pump inhibitors (21%), antidiabetics (metformin or sulfonylureas, 50%), and sporadic NSAIDs (43%). Blood lipid levels showed significant differences between males and females as reported elsewhere (

Table 1). Individuals were classified by age group in 60 – 70y (69%), 71 – 80y (30%), and >80y (8.3%), and according to systolic and diastolic blood pressure control, in controlled <140/90 mmHg and uncontrolled ≥140/90 mmHg (

Table 1), differences between the sexes and hypertension control were significant.

2.1. Gut Microbiota Composition in Hypertensive Older Adults

First, we investigated the relative abundance of bacteria phylum and genera, observing that

Bacteroidetes showed the highest abundance (49%) followed by

Firmicutes (42%),

Proteobacteria (7%), and

Verrucomicrobia (1.0%). At the genus level

Bacteroides (27%),

Prevotella 9 (14%),

Faecalibacterium (5.4%),

Lachnospiraceae,

Escherichia-Shigella (4.7%),

Allistipes (4.2%),

Ruminococcaceae UCG-002 (3.7%), and

Parabacteroides (2.9%),

Eubacterium coprostanoligenes (2.5%)

Roseburia (1.8%) and

Christensenellaceae R-7 (1.1 %) were the most abundant (

Figure 1). Microbiota composition was also evaluated according to hypertension control for systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP), and no significant differences were observed (Supplemental

Figure S1).

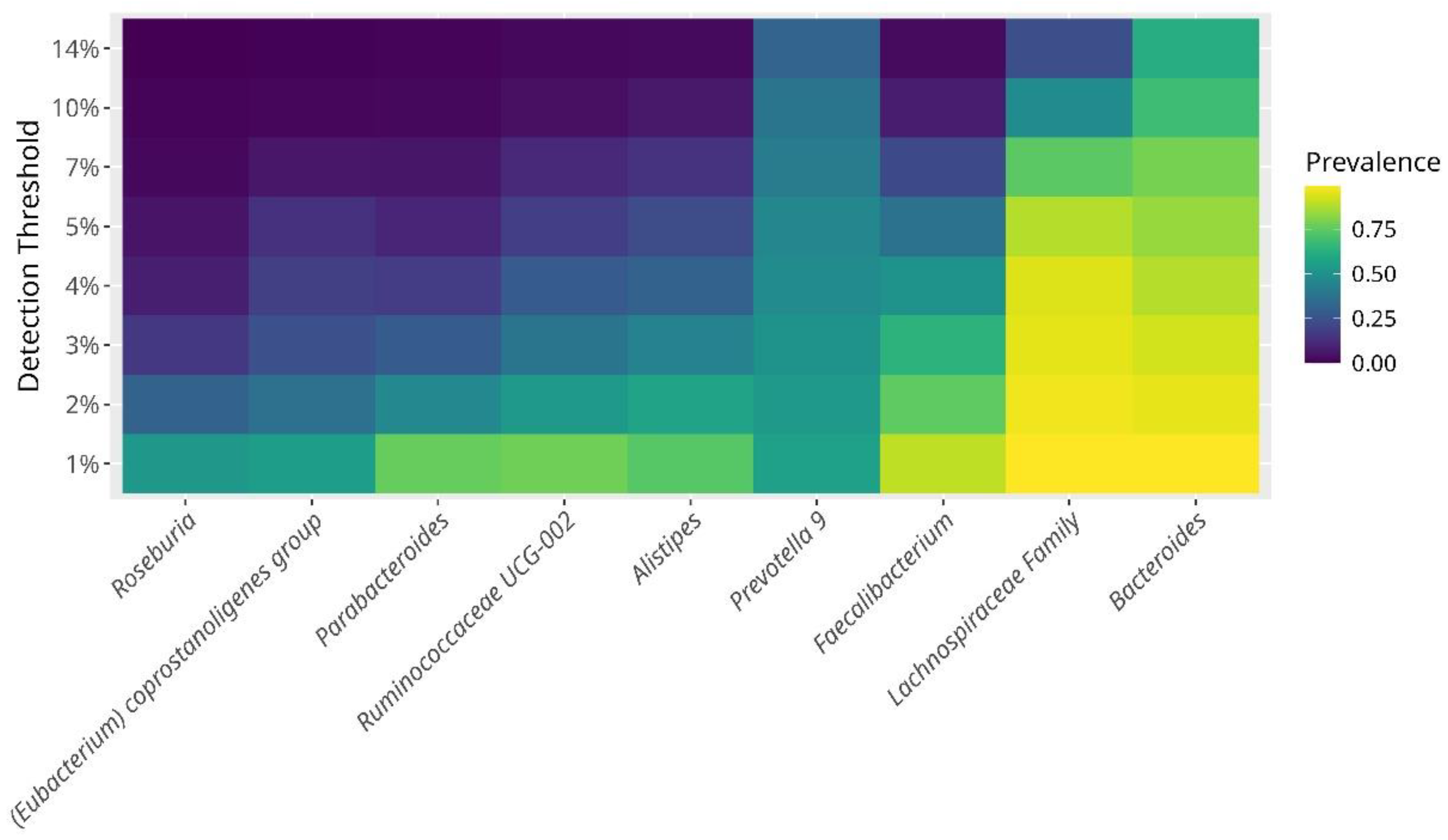

2.2. The Core Microbiome in Hypertensive Older Adults

One of the aims of the study was to depict the core bacterial composition of the gut microbiome characterizing hypertensive older adults. We identified that prevailing bacteria were, in order of prevalence and abundance were,

Bacteroides, Prevotella 9, Faecalibacterium, Alistipes, Ruminococcaceae UCG-002, Parabacteroides, Eubacterium coprostanoligenes,and

Roseburia showing a prevalence of up-to 40% (

Figure 2). In addition, with a lower, but consistent abundance we found,

Escherichia-Shigella, Paraprevotella, Phascolarctobacterium, Ruminoccocus 2, Subdoligranulum, Dialister, Ruminococcaceae UCG-014 &

UCG-005, Ruminococcus 1, Christensenellaceae R-7, Barnesiella, and

Blautia with an abundance around 20%.

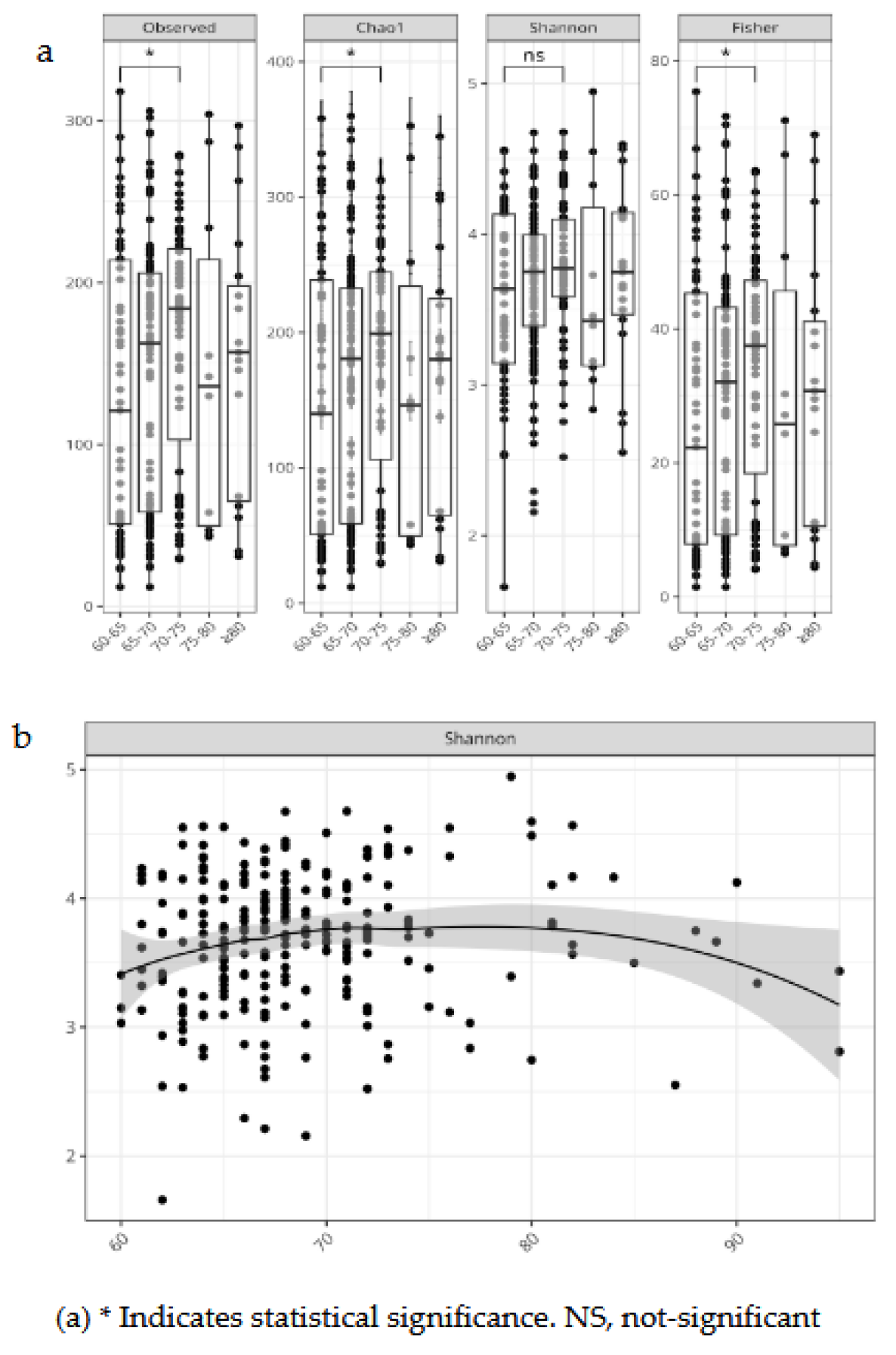

2.3. Alpha Diversity Indexes in Hypertnesive Patients

We evaluated bacterial richness and diversity using several metrics, considering age as a continuous variable and stratified by age groups. Alpha diversity indexes were compared between controlled vs. uncontrolled patients.

For age group 60-75y, the indexes, Chao 1, Fisher, and Observed OTUs, showed a higher richness, and singletons or rare bacteria than >75-year-olds. Considering age as a continuous variable we observed an increase in bacterial richness in 70-year-olds, and a decrease after 80 years (

Figure 3). Alpha diversity indexes comparing controlled and uncontrolled SBP and DBP did not show significant differences, these groups seemed similar in terms of abundance or richness for SBP control, but there was a lower number of ASV in uncontrolled DBP patients as shown by a lower Chao1 index (Supplemental

Figure S2).

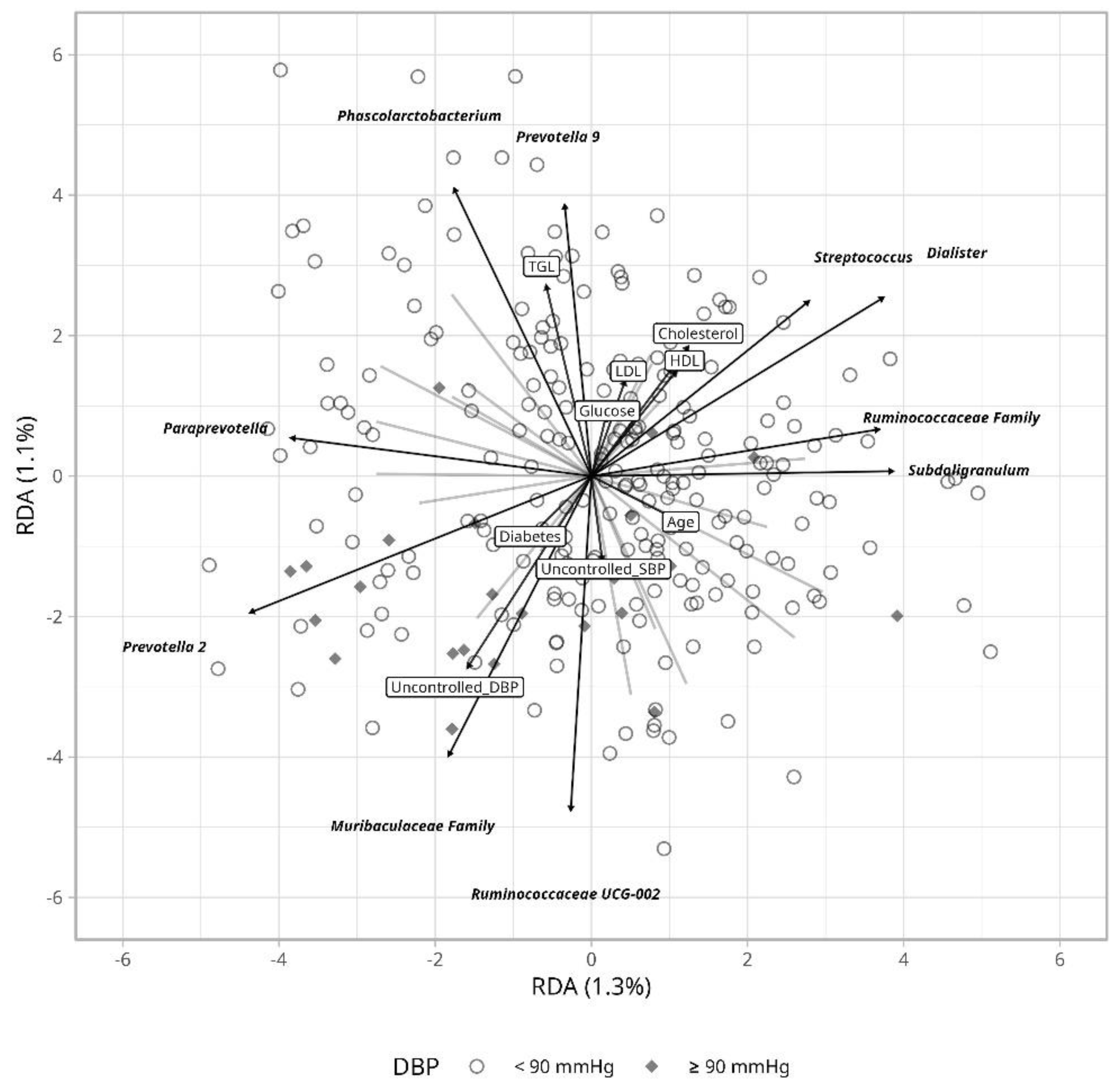

2.4. Beta Diversity

To assess differences in bacterial composition between controlled and uncontrolled hypertension, we estimated a Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index but found no clustering differences when comparing blood pressure levels ≥140/90 mmHg vs <140/90 mmHg (Supplemental

Figure S3). Hence, we evaluated the impact of clinical variables using Redundancy Analysis (RDA) that may explain variation in hypertension control.

Ruminococcaceae and

Muribaculaceae seem to partly accompany uncontrolled hypertension more apparently for diastolic than for systolic blood pressure (

Figure 4). Age seems to be in part influenced by

Escherichia-Shigella, while blood glucose and lipids levels variation were accompanied by changes in

Prevotella 9 and

Phascolarctobacterium abundance.

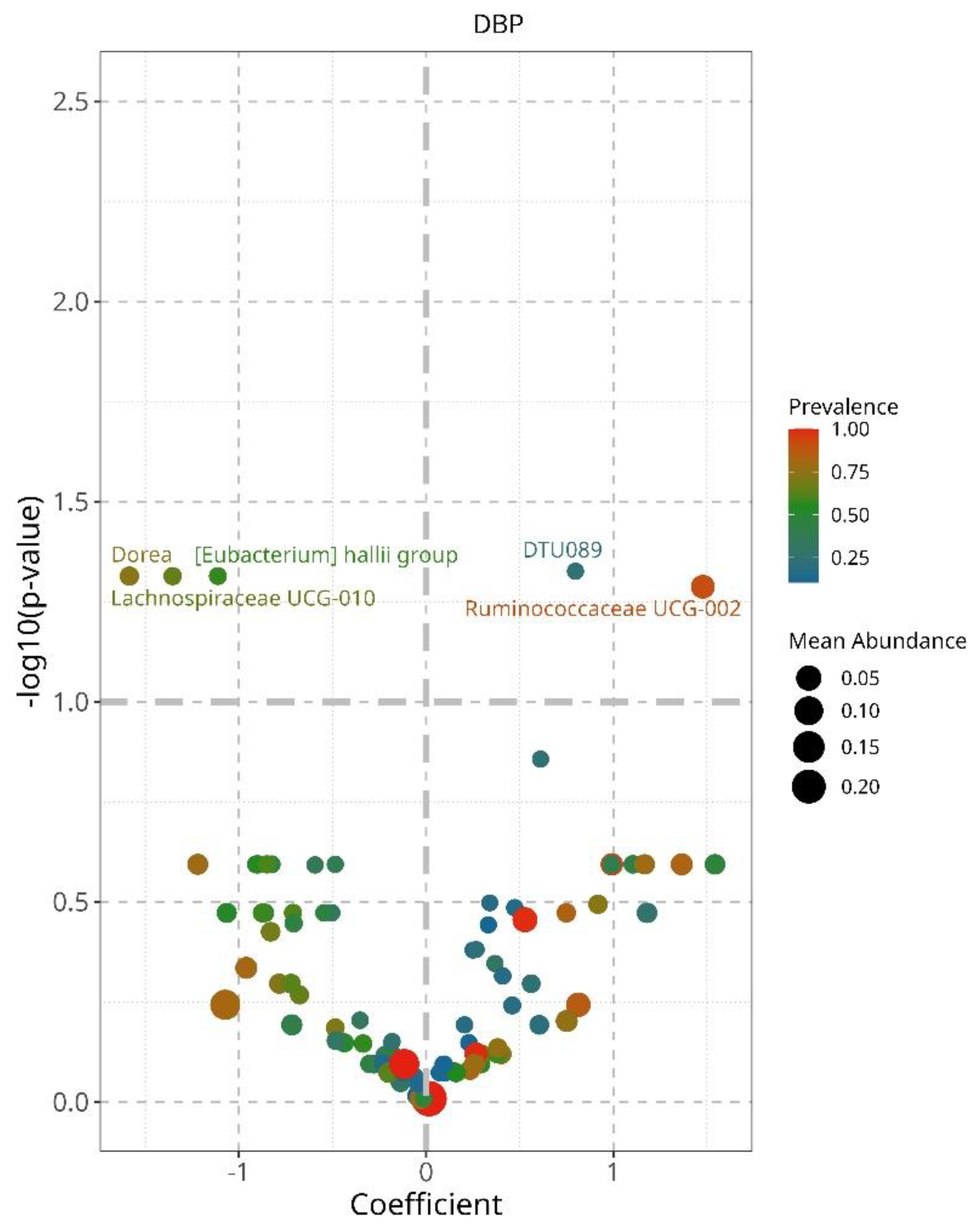

2.5. Bacterial Differential Abundance According to Hypertension Control

To continue the quest to identify bacteria that could explain differences in controlled and uncontrolled hypertensive patients, we performed a linear decomposition analysis (LinDA) and characterized associations between the gut microbiome and hypertension control for SBP and DBP separately [

12]. We found that when DBP is controlled there is an increased abundance of

Ruminococcaceae UCG002, and

DTU 089, and a decrease of

Dorea, Lachnospiraceae UCG-010, and

Eubacterium hailli group (

Figure 5). Controlled SBP was accompanied by an increase of

DTU089 and

several Ruminococcus genre similar to that observed for DBP, but these did not reach statistical significance (Supplemental

Figure S4).

3. Discussion

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide with hypertension and its complications accounting for over 50% of these deaths, according to the World Health Organization. Research in the field has become multidisciplinary to better tackle the diversity of metabolic paths involved in hypertension and to improve treatment strategies. Consequently, research focused on the gut microbiome has shown some revealing differences in the gut bacteria of hypertensive compared to normotensive individuals, providing hypotheses that support the role of bacteria as probiotics or enhancers of drug efficacy [

13,

14]. Here, we depict the core gut microbiome of 240 urban hypertensive older adults and investigated if hypertension control could be explained in part by microbial abundance differences; below we discuss our findings on the scope of current knowledge.

3.1. The Core Microbiome in Hypertnsive Older Adults

The composition of the gut microbiome in older adults is highly variable, yet certain patterns have been consistently reported. For instance, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes dominate 80% of the gut microbiome, with an increase of

Proteobacteria, and

Escherichia-Shigella with age [

15,

16]. Our findings align with these observations as we observed

Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes composing up-to-91% of the gut microbiota, with

Bacteroidetes being more prevalent (49%) than

Firmicutes (41%), as previously reported [

17]. The core bacteria belonged to the Bacteroidetes phylum,

Bacteroides, Parabacteroides Prevotella 9, Alistipes; and

Faecalibacterium, Ruminococcaceae UCG-002, Eubacterium coprostanoligenes, and

Roseburia from the

Firmicutes phylum, composing up-to 40% of the gut microbiome (

Figure 2). This is consistent with previous reports on the gut microbiome of older adults [

18].

E. coprostanoligenes has been consistently detected in older adults, its abundance increases with age and has been observed in the transition from adulthood to older adults [

19,

20,

21]. Hence, the presence of

E. coprostanoligenes was not surprising, and could be related to the age of this population.

Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, Alistipes, and

Prevotella 9 also characterizing the gut microbiome of the older adults here, further confirms their role as major components of the gut microbiome in other studies [

18,

22]. Potential roles for each genus have been discussed before. For example,

Prevotella 9 has been associated with accelerated aging and proinflammatory effects, contributing to the inflammaging phenotype [

23].

Parabacteroides in the elderly is inconclusive, some research found it more abundant in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and others associated it with positive outcomes in mental health and diet, its abundance seems to accompany that of several strains of

Ruminococcaceae, which was also observed here [

24,

25]

. Alistipes another age dependent bacterium, has been associated with anti-inflammatory properties, SCFA production, and beneficial gut health. Nevertheless, its overabundance has been observed in inflammatory bowel disease, depression, and hypertension highlighting the fact that its roles are not fully clear and cannot be interpreted in isolation [

26].

Also, characterizing the microbiome of hypertensive older adults, we observed bacteria with an average abundance of 20% including members of the family,

Ruminococcaceae, and the genus

Phascolarctobacterium Subdoligranulum, Dialister, Blautia, Barnesiella,

Paraprevotella, Christensenellaceae R-7, and

Escherichia-Shigella. Many of these have been reported to increase with age [

27,

28]. The abundance of

Escherichia-Shigella was apparent and higher than that reported in young, middle-aged adults, or healthy populations [

17,

29]. Its presence has been confirmed in several aging studies and can explain the “inflammaging” phenotype of older adults. The biochemical consequences of the presence of

Escherichia-Shigella in these patients remains to be investigated, but it confirms part of the known gut microbiome of older adults.

3.2. Alpha Diversity

Variation of gut microbial diversity with age and hypertension control were analyzed using several metrics. Consistent with current research, we observed a decline in gut bacterial diversity with age [

30], this trend was observed when considering age as a continuous variable in individuals older than 75 y (

Figure 3). Interestingly, the age group 65-70y display an increased diversity which persisted right before 75y. This increase was statistically significant for all alpha diversity indices (

Figure 3) suggesting that the transition between 65y to 70y could represent a window of enhancing microbial diversity prior to its decrease shown by most individuals afterwards. There were no differences in alpha diversity for SBP control, but uncontrolled DBP showed a lower diversity compared to controlled DBP (p<0.05) for the Chao 1 index supporting the notion that healthier phenotypes show a richer gut microbiota [

31]. These observations are in part consistent with the literature suggesting a lower alpha diversity in diminished health conditions [

29,

32].

3.3. Beta Diversity and Hypertension Control

Several metrics were assessed to investigate gut microbial differences according to hypertension control, average bacterial composition was no different between controlled and uncontrolled patients, but some bacteria were able to explain variation in uncontrolled hypertension when considering clinical parameters including

Ruminococaceae UCG-002 and the

Muribaculaceae family (

Figure 4).

Ruminococaceae UCG-002 has been negatively associated with heart disease [

33] and metabolic syndrome [

34]. It is possible that the beneficial effects of several members of the

Ruminococaceae family are diminished in these patients since they are producers of SCFA which can modulate blood pressure through its interaction with the kidney receptors, GPR41, GPR43, and GPR109A [

35,

36].

Ruminocococcus can also improve linoleic acid and glucose absorption, insulin sensitivity, and intestinal integrity in mice which together may support cardiovascular health [

37]. We also observed that

Muribaculaceae family explained uncontrolled SBP and DBP, this family has been suggested as a “next generation probiotic” since they can produce SCFA, regulate the intestinal barrier function, and immune response. These bacteria are oxalate consumers so, it is possible that they may influence blood pressure through maintaining gut and kidney health [

38,

39]. Finally, in

Figure 4 we observed that the abundance in

Escherichia-Shigella was related to increasing age. An increased abundance of Escherichia-Shigella has been repeatedly associated with age and hypertension possibly mediated by

Escherichia-Shigella glycerophospholipid metabolism which activate toll-like receptors, increasing inflammation and endothelial dysfunction [

40]. The presence of

Escherichia-Shigella in an aging hypertensive population confirms an inflammatory phenotype of the host and its relation with hypertension [

43] confirming in part the phenotype of our study population.

3.4. Differential Abundance of the Lachnospiraceae Family, Bacteria Characterizing Uncontrolled Hypertension

We found succinct but interesting differences in bacteria for controlled diastolic blood pressure. On the one hand, there was an increase in

Ruminococcaceae UCG002, and

DTU 089, an increased abundance of

DTU 089 has not been previously acknowledged, this is a member of the

Lachnospiraceae family and has been associated with skeletal metabolism and low protein intake in older adults [

43,

44]. Our results validate the presence of

DTU 089 in older adults and its influence on health could be related to diet.

Ruminococcaceae UCG002 has been reported as negatively influencing cardiovascular health [

45], including hypertension [

44] these are fermenting microbes, producers of SCFA which can interact with kidney receptors, also influencing gut integrity, immunity and cholesterol transport [

47,

48]. On the other hand, controlled DBP, showed a significant decrease in

Dorea, Lachnospiracee UCG010, and Eubacterium hailli group (

Figure 5). These belong to the phylum

Firmicutes and the

Lachnospiraceae family, but members of this family can show contrasting functions in health and disease [

49].

Dorea has been associated with hypertension and its complications [

42], and

Lachnospiraceeae UCG10 to venous thromboembolism as a causal link [

50].

Eubacterium hallii also known as

Anaerobutyricum hallii is consistently reported as a beneficial bacterium, it can produce isobutyric acid from glucose, reuterin an antimicrobial compound, and vitamin B12 from glycerol [

51]. It has also been suggested as a probiotic for cancer prevention since it can conjugate and clear carcinogenic pyrimidine derivates from cooked meat [

51]. The beneficial properties of these members of the

Lachnospiraceae family seem to agree with its decrease in a hypertensive population. Investigations should decipher metabolic pathways differences within family members so that specific

Lachnospiraceae genus can be pinpointed as more sensitive or beneficial for blood pressure control. Of special interest could be

Enterobacter hailli group whose abundance has been associated with age [

19], hypertension [

13], inflammation, and insulin sensitivity [

52]. Its decrease in hypertensive older adults may reflect a direct depletion of its beneficial activity possibly through the decrease of butyrate production.

Here, we confirmed the association of the

Lachnospiraceae family with hypertension control. Noteworthy, the increase of

Lachnospiraceae DTU089 and Ruminococcus UCG-002, and the decrease of several members of the

Lachnospiraceae family i.e.,

Dorea, Eubacterium hallii, and

Lachnospiraceae UCG-010 in controlled hypertension suggests that different members of this family may distinctively contribute to the regulation of diastolic blood pressure. These microorganisms could be influencing blood pressure through fiber fermentation and SCFA production and its interaction with kidney receptors, also through renin and lipopolysaccharides release, [

13,

53] and generating metabolites such as dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine which favor increased angiotensin II and vasoconstriction [

42,

54]. This study encompassed only hypertensive older adults and did not include a normotensive group consequently, changes in bacterial abundance may be part of a more complex interplay and the directionality of changes in bacterial abundance may not fully align with previous studies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population

Participants (N=240) were invited to donate a sample between 2017 and 2022 at the Hospital, Centro Medico Nacional Siglo XXI (CMN-IMSS), all were older adults >60 years, and signed an informed consent, the protocol was approved by the Committees of Research Ethics approval numbers R2018-785-004 and CEI2017/04 & 23/2016/I. This research followed current bioethical and safety regulations including the principles of the declaration of Helsinki. Fecal samples were collected from patients who were carefully instructed and provided with an in-house collection kit, samples were added RNA-latr (Thermo-Scientific) and stored at -70ºC until DNA extraction

4.2. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA V3/V4 Sequencing

DNA was isolated from 200 mg of feces using the DNA QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and stored at −20 °C. The hypervariable region V3-V4 was amplified using the 16S V3 (341F) forward and V4 (805R) reverse primers and adapters from Illumina following the manufacturer’s 16S metagenomic sequencing library protocol. PCR reactions were 30 µL in volume using 4 μL of DNA (50 ng/µL), 0.25 µL of each PCR primer (10 pM), and 15 µL of 2X Platinum™ SuperFi™ PCR Master Mix (Invitrogen, USA). Amplification followed 25 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min, fragments were cleaned with Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter Genomics, Brea, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Indexes and adaptors were ligated by PCR with 5 μL of Ilumina Nextera XT Index Primer 1 (N7XX), 5 μL of Nextera XT Index Primer 2 (S5XX), 25 μL of 2X Platinum™ SuperFi™ PCR Master Mix (Invitrogen, USA) in a thermocycler for 95 °C for 3 min, and 6 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. These 16S rRNA V3-V4 libraries were purified with Agencourt AMPure XP beads. Library quality control was verified by microcapillary electrophoresis in a TapeStation 4200 (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA), libraries were normalized and pooled to 10.2 nM, denatured and diluted to a final concentration of 10 pM including 20% of PhiX. Libraries were sequenced using a 2x250bp cartridge/MiSeq Reagent Kit V3 in a MiSeq (Illumina).

4.3. Bioinformatic Analyses

Paired-end FASTQ files were evaluated for quality controls using QIIME2 v2024.5, followed by denoising with the plugin, Divisive Amplicon Denoising Algorithm 2 (DADA2), resultant Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) were used to obtain the taxonomy table using naive-bayes pre-trained classifier for the V3-V4 hypervariable region of 16SrRNA gene, based on the ribosomal database SILVA_138, QIIME2 artifacts were imported using R library qiime2R to Phyloseq [

55]. Statistical analyses were conducted in R version 4.0.4 [

56]

To assess batch effects and batch correction, we used principal coordinate analysis (PCA) on adjusted and unadjusted rarefied relative abundance with centered log-ratio normalization using MicroViz R library. Group comparisons were stratified by age and hypertension control <140/90 mmHg versus uncontrolled ≥ 140/90 mmHg SBP/DBP levels. Rarefaction was set to the minimum sampling depth across samples in this case 26500 sequences per sample. The core microbiome was assessed based on a sample prevalence of > 50% at a relative abundance frequency of > 1% at the genus level. Several alpha diversity indexes were assessed including, Observed Species, Shannon Index, Chao Index, Simpson dissimilarity, and Fisher index. Significant differences in alpha diversity across groups were calculated using Kruskal Wallis and Wilcoxon tests. PCA and Redundancy Analysis (RDA) were conducted using centered log-ratio normalized counts at the genus level using MicroViz R library. The RDA included clinical variables: age, uncontrolled systolic or diastolic blood pressure, cholesterol, HDLC, LDLC, glucose, and triglycerides. Beta diversity was calculated using Bray Curtis dissimilarity distances. Also, a Permutational Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) was conducted with 999 permutations, to test the association between the composition of the microbiota and clinical variables, SBP, DBP, age and sex. Differential abundance analyses at the genus level were performed using the linear regression framework for differential abundance analysis (LinDA) fitting a linear model for abundance data and correcting for compositional effects and biases, p-values were adjusted using false discovery rate (FDR) correction, with a significance threshold of p-value≤ 0.01.

5. Conclusions

We described the core microbiome of hypertensive older adults and validated the relationship between the gut microbiome and hypertension control in urban dwellers. Confirming on the one hand, the relationship between age and Escherichia-Shigella and on the other, the potential role of Dorea, Ruminococcaceaae UCG-010 and several members of the Lachnospiraceae family in hypertension control. Our observations expand the growing evidence on the microbiome and its influence in aging and hypertension.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Relative abundance of the gut microbiota according to hypertension control; Figure S2: Alpha diversity according to hypertension control; Figure S3: Beta diversity according to hypertension control (Bray-Curtis and PERMANOVA analysis); Figure S4: A. Differential abundance for diastolic blood pressure. B. Differential abundance for diastolic blood pressure before FDR correction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.G-C., S.S-G., B.P-G., P.G-dT; Methodology, F.P-V.; V.G-C., M.R-D., and TT.; Formal analysis: F.P-V, S.F, V.G-C; Resources, S.S-G., P.G-dT J.D.M-E. V.G-C, B.P-G; M.R-D.; Data curation, F.P-V., B.P-G., J.D.M-E., TT.; Writing: V.G-C, F.P-V; Review and editing, B.P-G., S.F., M.R-D., A.G. All authors have revised and agreed to the last version of the study.

Funding

This work was partly supported by INMEGEN. Tomas Texis was supported by the Posgrado of Ciencias Bioquímicas at UNAM.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Committees of Research Ethics at CMN-SXXI (IMSS) R2018-785-004, and at INMEGEN, CEI2017/04 and 23/2016/I in Mexico City. This research followed the principles of the declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Participants (N=240) were invited to donate a sample between 2017 and 2022 at Centro Medico Nacional Siglo XXI (CMN-IMSS), all were older adults >60 years, and signed a written informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Arianna Galicia, Adrian Cruz, and Cinthia Cruz during the management of clinical samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest, nor financial interests related to this work.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SBP |

Systolic blood pressure |

| DBP |

Diastolic blood pressure |

| SCFA |

Short chain fatty acids |

| ACE |

Angiotensin converting enzyme |

References

- J.Y. Dong, I.M.Y. Szeto, K. Makinen, Q. Gao, J. Wang, L.Q. Qin, Y. Zhao, Effect of probiotic fermented milk on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials, Br. J. Nutr. 110 (2013) 1188–1194. [CrossRef]

- T. Yang, M.M. Santisteban, V. Rodriguez, E. Li, N. Ahmari, J.M. Carvajal, M. Zadeh, M. Gong, Y. Qi, J. Zubcevic, B. Sahay, C.J. Pepine, M.K. Raizada, M. Mohamadzadeh, Gut dysbiosis is linked to hypertension, Hypertens. (Dallas, Tex. 1979). 65 (2015) 1331–1340. [CrossRef]

- S. Sun, A. Lulla, M. Sioda, K. Winglee, M.C. Wu, D.R. Jacobs, J.M. Shikany, D.M. Lloyd-Jones, L.J. Launer, A.A. Fodor, K.A. Meyer, Gut microbiota composition and blood pressure: The CARDIA study, Hypertension. 73 (2019) 998–1006. [CrossRef]

- J.P. Haran, B.A. McCormick, Aging, Frailty, and the Microbiome: How Dysbiosis Influences Human Aging and Disease, Gastroenterology. 160 (2021) 507. [CrossRef]

- H.J. Zapata, V.J. Quagliarello, The microbiota and microbiome in aging: Potential implications in health and age-related diseases, J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 63 (2015) 776–781. [CrossRef]

- S. Al Khodor, B. Reichert, I.F. Shatat, The Microbiome and Blood Pressure: Can Microbes Regulate Our Blood Pressure?, Front. Pediatr. 5 (2017) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Althani, H.E. Marei, W.S. Hamdi, G.K. Nasrallah, M.E. El Zowalaty, S. Al Khodor, M. Al-Asmakh, H. Abdel-Aziz, C. Cenciarelli, Human Microbiome and its Association With Health and Diseases, J. Cell. Physiol. 231 (2016) 1688–1694. [CrossRef]

- M. Zimmermann, M. Zimmermann-Kogadeeva, R. Wegmann, A.L. Goodman, Mapping human microbiome drug metabolism by gut bacteria and their genes, Nature. 570 (2019) 462–467. [CrossRef]

- T. Yang, X. Mei, E. Tackie-Yarboi, M.T. Akere, J. Kyoung, B. Mell, J.Y. Yeo, X. Cheng, J. Zubcevic, E.M. Richards, C.J. Pepine, M.K. Raizada, I.T. Schiefer, B. Joe, Identification of a Gut Commensal That Compromises the Blood Pressure-Lowering Effect of Ester Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors, Hypertens. (Dallas, Tex. 1979). 79 (2022) 1591–1601. [CrossRef]

- I. Robles-Vera, M. Toral, N. de la Visitación, M. Sánchez, M. Gómez-Guzmán, R. Muñoz, F. Algieri, T. Vezza, R. Jiménez, J. Gálvez, M. Romero, J.M. Redondo, J. Duarte, Changes to the gut microbiota induced by losartan contributes to its antihypertensive effects, Br. J. Pharmacol. 177 (2020) 2006. [CrossRef]

- S.K. Forslund, R. Chakaroun, M. Zimmermann-Kogadeeva, Combinatorial, additive and dose-dependent drug-microbiome associations, Nature. 600 (2021) 500–505. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhou, K. He, J. Chen, X. Zhang, LinDA: linear models for differential abundance analysis of microbiome compositional data, Genome Biol. 2022 231. 23 (2022) 1–23. [CrossRef]

- B.J.H. Verhaar, D. Collard, A. Prodan, J.H.M. Levels, A.H. Zwinderman, F. Backhed, L. Vogt, M.J.L. Peters, M. Muller, M. Nieuwdorp, B.J.H. Van Den Born, Associations between gut microbiota, faecal short-chain fatty acids, and blood pressure across ethnic groups: the HELIUS study, Eur. Heart J. 41 (2020) 4259–4267. [CrossRef]

- E. Dinakis, M. Nakai, P. Gill, R. Ribeiro, S. Yiallourou, Y. Sata, J. Muir, M. Carrington, G.A. Head, D.M. Kaye, F.Z. Marques, Association between the Gut Microbiome and Their Metabolites with Human Blood Pressure Variability, Hypertension. 79 (2022) 1690–1701. [CrossRef]

- M.G. Novelle, B. Naranjo-Martínez, J.L. López-Cánovas, A. Díaz-Ruiz, Fecal microbiota transplantation, a tool to transfer healthy longevity, Ageing Res. Rev. 103 (2025). [CrossRef]

- N. Salazar, L. Valdés-Varela, S. González, M. Gueimonde, C.G. de los Reyes-Gavilán, Nutrition and the gut microbiome in the elderly, Gut Microbes. 8 (2017) 82–97. [CrossRef]

- E. Bradley, J. Haran, The human gut microbiome and aging, Gut Microbes. 16 (2024). [CrossRef]

- P.W. O’Toole, M.J. Claesson, Gut microbiota: Changes throughout the lifespan from infancy to elderly, Int. Dairy J. 20 (2010) 281–291. [CrossRef]

- E. Biagi, L. Nylund, M. Candela, R. Ostan, L. Bucci, E. Pini, J. Nikkïla, D. Monti, R. Satokari, C. Franceschi, P. Brigidi, W. de Vos, Through Ageing, and Beyond: Gut Microbiota and Inflammatory Status in Seniors and Centenarians, PLoS One. 5 (2010) e10667. [CrossRef]

- Z.Y. Wei, J.H. Rao, M.T. Tang, G.A. Zhao, Q.C. Li, L.M. Wu, S.Q. Liu, B.H. Li, B.Q. Xiao, X.Y. Liu, J.H. Chen, Characterization of Changes and Driver Microbes in Gut Microbiota During Healthy Aging Using A Captive Monkey Model, Genomics. Proteomics Bioinformatics. 20 (2021) 350. [CrossRef]

- E. Sepp, I. Smidt, T. Rööp, J. Štšepetova, S. Kõljalg, M. Mikelsaar, I. Soidla, M. Ainsaar, H. Kolk, M. Vallas, M. Jaagura, R. Mändar, Comparative Analysis of Gut Microbiota in Centenarians and Young People: Impact of Eating Habits and Childhood Living Environment, Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12 (2022) 851404. [CrossRef]

- E. Biagi, M. Candela, S. Fairweather-Tait, C. Franceschi, P. Brigidi, Aging of the human metaorganism: the microbial counterpart, Age (Dordr). 34 (2012) 247–267. [CrossRef]

- S. Singh, L.B. Giron, M.W. Shaikh, S. Shankaran, P.A. Engen, Z.R. Bogin, S.A. Bambi, A.R. Goldman, J.L.L.C. et. al., Distinct intestinal microbial signatures linked to accelerated systemic and intestinal biological aging, Microbiome 2024 121. 12 (2024) 1–23. [CrossRef]

- C.A. Olson, H.E. Vuong, J.M. Yano, Q.Y. Liang, D.J. Nusbaum, E.Y. Hsiao, The Gut Microbiota Mediates the Anti-Seizure Effects of the Ketogenic Diet, Cell. 173 (2018) 1728-1741.e13. [CrossRef]

- N. Molinero, A. Antón-Fernández, F. Hernández, J. Ávila, B. Bartolomé, M.V. Moreno-Arribas, Gut Microbiota, an Additional Hallmark of Human Aging and Neurodegeneration, Neuroscience. 518 (2023) 141–161. [CrossRef]

- J. Tokarek, E. Budny, M. Saar, J. Kućmierz, E. Młynarska, J. Rysz, B. Franczyk, Does the Composition of Gut Microbiota Affect Hypertension? Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Increasing Blood Pressure, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (2023). [CrossRef]

- M. Victoria, V.D.B. Elena, G.G.N. Amparo, J.R.A. María, G.V. Adriana, A.C. Irene, Y.M.M. Alejandra, B.B. Janeth, A.O.G. María, Gut microbiota alterations in critically ill older patients: a multicenter study, BMC Geriatr. 22 (2022) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- S. Farsijani, J.A. Cauley, P.M. Cawthon, L. Langsetmo, E.S. Orwoll, D.M. Kado, D.P. Kiel, A.B. Newman, Associations Between Walking Speed and Gut Microbiome Composition in Older Men From the MrOS Study, J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 79 (2024). [CrossRef]

- T. Odamaki, K. Kato, H. Sugahara, N. Hashikura, S. Takahashi, J.Z. Xiao, F. Abe, R. Osawa, Age-related changes in gut microbiota composition from newborn to centenarian: A cross-sectional study, BMC Microbiol. 16 (2016) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- A. Renson, K.M. Harris, J.B. Dowd, L. Gaydosh, M.B. McQueen, K.S. Krauter, M. Shannahan, A.E. Aiello, Early Signs of Gut Microbiome Aging: Biomarkers of Inflammation, Metabolism, and Macromolecular Damage in Young Adulthood, J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75 (2020) 1258–1266. [CrossRef]

- P. Louca, A. Nogal, P.M. Wells, F. Asnicar, J. Wolf, C.J. Steves, T.D. Spector, N. Segata, S.E. Berry, A.M. Valdes, C. Menni, Gut microbiome diversity and composition is associated with hypertension in women, J. Hypertens. 39 (2021) 1810–1816. [CrossRef]

- M. Choroszy, K. Litwinowicz, R. Bednarz, T. Roleder, A. Lerman, T. Toya, K. Kamiński, E. Sawicka-Śmiarowska, M. Niemira, B. Sobieszczańska, Human Gut Microbiota in Coronary Artery Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis †, Metabolites. 12 (2022). [CrossRef]

- T. Li, Q. Sun, L. Feng, D. Yan, B. Wang, M. Li, X. Xiong, D. Ma, Y. Gao, Uncovering the characteristics of the gut microbiota in patients with acute ischemic stroke and phlegm-heat syndrome, PLoS One. 17 (2022). [CrossRef]

- M. Wutthi-in, S. Cheevadhanarak, S. Yasom, S. Kerdphoo, P. Thiennimitr, A. Phrommintikul, N. Chattipakorn, W. Kittichotirat, S. Chattipakorn, Gut Microbiota Profiles of Treated Metabolic Syndrome Patients and their Relationship with Metabolic Health, Sci. Rep. 10 (2020) 10085. [CrossRef]

- C. Tilves, H.C. Yeh, N. Maruthur, S.P. Juraschek, E. Miller, K. White, L.J. Appel, N.T. Mueller, Increases in Circulating and Fecal Butyrate are Associated With Reduced Blood Pressure and Hypertension: Results From the SPIRIT Trial, J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11 (2022). [CrossRef]

- B. Gao, A. Jose, N. Alonzo-Palma, T. Malik, D. Shankaranarayanan, R. Regunathan-Shenk, D.S. Raj, Butyrate producing microbiota are reduced in chronic kidney diseases, Sci. Reports 2021 111. 11 (2021) 1–11. [CrossRef]

- J. Xie, L. Li, T. Dai, X. Qi, Y. Wang, T. Zheng, X. Gao, Y. Zhang, Y. Ai, L. Ma, S. Chang, F. Luo, Y. Tian, J. Sheng, Short-Chain Fatty Acids Produced by Ruminococcaceae Mediate α-Linolenic Acid Promote Intestinal Stem Cells Proliferation, Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 66 (2022) 2100408. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, J.B. Sun, S. Xie, Y. Zhou, T. Wang, Z.Y. Liu, C.S. Li, L. Gao, T.J. Pan, Increased abundance of bacteria of the family Muribaculaceae achieved by fecal microbiome transplantation correlates with the inhibition of kidney calcium oxalate stone deposition in experimental rats, Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13 (2023) 1145196. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, B. Chen, X. Zhang, M.T. Akbar, T. Wu, Y. Zhang, L. Zhi, Q. Shen, Exploration of the Muribaculaceae Family in the Gut Microbiota: Diversity, Metabolism, and Function, Nutr. 2024, Vol. 16, Page 2660. 16 (2024) 2660. [CrossRef]

- J. meng Wang, M. xiao Yang, Q. feng Wu, J. Chen, S. fang Deng, L. Chen, D. neng Wei, F. rong Liang, Improvement of intestinal flora: accompany with the antihypertensive effect of electroacupuncture on stage 1 hypertension, Chinese Med. (United Kingdom). 16 (2021) 1–11. [CrossRef]

- J. Guo, P. Jia, Z. Gu, W. Tang, A. Wang, Y. Sun, Z. Li, Altered gut microbiota and metabolite profiles provide clues in understanding resistant hypertension, J. Hypertens. 42 (2024) 1212–1225. [CrossRef]

- C. Miao, X. Xu, S. Huang, L. Kong, Z. He, Y. Wang, K. Chen, L. Xiao, The Causality between Gut Microbiota and Hypertension and Hypertension-related Complications: A Bidirectional Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Analysis, Hell. J. Cardiol. (2024). [CrossRef]

- P.C. Okoro, E.S. Orwoll, C. Huttenhower, X. Morgan, T.M. Kuntz, L.J. McIver, A.B. Dufour, M.L. Bouxsein, L. Langsetmo, S. Farsijani, D.M. Kado, R. Pacifici, S. Sahni, D.P. Kiel, A two-cohort study on the association between the gut microbiota and bone density, microarchitecture, and strength, Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14 (2023). [CrossRef]

- S. Farsijani, J.A. Cauley, S.D. Peddada, L. Langsetmo, J.M. Shikany, E.S. Orwoll, K.E. Ensrud, P.M. Cawthon, A.B. Newman, Relation Between Dietary Protein Intake and Gut Microbiome Composition in Community-Dwelling Older Men: Findings from the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS), J. Nutr. 152 (2022) 2877. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen, Z.Y. Wang, D. Li, B. Zhu, Y. Xia, G. Wang, L. Ai, C. Zhang, C. Wang, The gut microbiota as a target to improve health conditions in a confined environment, Front. Microbiol. 13 (2022) 1067756. [CrossRef]

- Y. Qin, J. Zhao, Y. Wang, M. Bai, S. Sun, Specific Alterations of Gut Microbiota in Chinese Patients with Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Kidney Blood Press. Res. 47 (2022) 433–447. [CrossRef]

- M.E. Sanders, D.J. Merenstein, G. Reid, G.R. Gibson, R.A. Rastall, Probiotics and prebiotics in intestinal health and disease: from biology to the clinic, Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16 (2019) 605–616. [CrossRef]

- D. Vojinovic, D. Radjabzadeh, A. Kurilshikov, N. Amin, C. Wijmenga, L. Franke, M.A. Ikram, A.G. Uitterlinden, A. Zhernakova, J. Fu, R. Kraaij, C.M. van Duijn, Relationship between gut microbiota and circulating metabolites in population-based cohorts, Nat. Commun. 2019 101. 10 (2019) 1–7. [CrossRef]

- M. Vacca, G. Celano, F.M. Calabrese, P. Portincasa, M. Gobbetti, M. De Angelis, The Controversial Role of Human Gut Lachnospiraceae, Microorganisms. 8 (2020) 573. [CrossRef]

- P. Huang, Y. Xiao, Y. He, The causal relationships between gut microbiota and venous thromboembolism: a Mendelian randomization study, Hereditas. 162 (2025). [CrossRef]

- C. Engels, H.J. Ruscheweyh, N. Beerenwinkel, C. Lacroix, C. Schwab, The common gut microbe Eubacterium hallii also contributes to intestinal propionate formation, Front. Microbiol. 7 (2016) 184615. [CrossRef]

- S. Udayappan, L. Manneras-Holm, A. Chaplin-Scott, C. Belzer, H. Herrema, G.M. Dallinga-Thie, S.H. Duncan, E.S.G. Stroes, A.K. Groen, H.J. Flint, F. Backhed, W.M. De Vos, M. Nieuwdorp, Oral treatment with Eubacterium hallii improves insulin sensitivity in db/db mice, Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2016 21. 2 (2016) 1–10. [CrossRef]

- D. Yan, Y. Sun, X. Zhou, W. Si, J. Liu, M. Li, M. Wu, Regulatory effect of gut microbes on blood pressure, Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 5 (2022) 513–531. [CrossRef]

- C. Xu, F.Z. Marques, How Dietary Fibre, Acting via the Gut Microbiome, Lowers Blood Pressure, Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 24 (2022) 509–521. [CrossRef]

- M. Hall, R.G. Beiko, 16S rRNA Gene Analysis with QIIME2, in: Methods Mol. Biol., 2018: pp. 113–129. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team, R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Found. Stat. Comput. Vienna Austria. 0 (2015) {ISBN} 3-900051-07-0.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).