1. Introduction

Ensuring the sustainability of winemaking process is a continuous challenge to which new answers are daily emerging. One of the biggest by-product in enology industry, is grape pomace. Grape crops produce each year 63 million tons worldwide, and 75% of these crops are dedicated to wine production (García Lomillo et al., 2017). Approximately 20% of the grapes weight constitute the main winemaking by-product, the grape pomace (Antonić et al., 2020). Only in Spain, 5 million tonnes of fresh grapes were produced in 2023, being the third largest wine producing country in the world (OIV).

Grape pomaces have traditionally been re-used as low value-added products, such as animal feed, compost or bioenergy (Kokkinomagoulos et al., 2020). In recent years, plenty of studies have been conducted looking for using this by-product as a new fining agent (Bindon et al., 2012; Guerrero et al., 2013¸ Jiménez-Martínez et al., 2019; Osete-Alcaraz et al., 2024), and hence for turning it into a valuable product again, that can be reused in the same industry. Furthermore, the interest in developing effective fining agents of vegetal origin has also increased, to replace the traditional fining agents, such as casein, gelatin, albumin or isinglass, which have an allergenic potential and are not suitable for a vegan diet.

Wine fining consists in adding a substance or a mixture to stabilize or modify the organoleptic characteristics of the wine, but it could also be used to enhance the safety of wine without modifying its color and flavour. In terms of possible wine contaminants, some may be produced during the winemaking process and others could be carried over from the vineyard itself. In this study, we wanted to focus our attention in three types of contaminants of different origins and chemical nature: pesticides, ochratoxin A (OTA) and histamine.

The presence of pesticides in wines has been detected and reported in many countries of the mediterranean area (Cabras et al., 2001; Fontana et al., 2011; Humbert et al., 2013; Herrero-Hernández et al., 2013). Fungicides are generally the most used pesticides, due the common presence of moulds such as Botrytis cinerea (gray mold), Uncinula necator (powdery mildew), and Plasmopara viticola (downy mildew) in the vineyard, being the main infections that affect the grapes (Hocking et al., 2007). The effect of pesticides in human health is difficult to determinate because it depends on several factors, and humans are exposed to them through various routes, like residues in food and drinking water (Kim et al., 2017), but, because many of these pesticides have the potential to bioaccumulate (Zhou et al., 2024), the continue exposure to pesticides has been related to multiples illness and disorders (Tudi et al., 2022). To this day, maximum pesticide limits have not been stablished for wine, these limits are only set for grapes in European Union (European Commission, 2005).

Ochratoxin A is a mycotoxin whose presence in wine is linked to fungal contamination of the grapes, mainly by Aspergillus and Penicillium (Jiang et al., 2015). OTA was classified as a potential human carcinogen (group 2B) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), with nephrotoxic, hepatotoxic, teratogenic, and carcinogenic effects (Cubaiu et al., 2012; Freire et al., 2020), and it has been correlated with tumours in the human urinary tract (Pfohl-Leszkowicz et al., 2007; Tao et al., 2018; Stoev, 2022). To this day, OTA has been detected in wheat, corn, cocoa, nuts or malt, and therefore has also been found in final products such as beer, wine, chocolate or bread (Kawashima et al., 2007; Riba et al., 2008; Freire et al., 2020). However, the processing techniques may vary the amount of OTA in the final product and in the case of wine it has been proven that long macerations increase OTA´s final concentration in this product (Grazioli et al., 2006). Due to health-related concerns, the maximum tolerable level in wines was fixed by European Commission (by regulation 1881/2006) at 2 µg/L.

The main biogenic amines found in wine are histamine, tyramine, putrescine, cadaverine and phenylethylamine (López et al., 2012) and their main origin have been related to wine malolactic fermentation and wine storage (Kosmerl et al., 2013; Greifová et al., 2017). Even though low levels of this amines are normal in the organism, an excessive intake of them could lead to health problems such as itching, headache, hypertension and tachycardia (Ladero et al., 2010). Histamine is the BA found in higher concentrations in wine. In the last decade, histamine intolerance has gained recognition, with most patients manifesting gastroinstestinal problems, abdominal distention and pain, followed by dizziness, headaches and palpitations (Comas-Basté et al., 2020). However, it is important to note that high histamine concentrations will not only affect sensitive populations, but all consumers. Some European countries have already established maximum limits of histamine in wine: 2 mg/L in Germany, 5 mg/L in Finland, 10 mg/L in Australia and Switzerland, 8 mg/L in France, 3.5 mg/L in Netherlands and 5-6 mg/L in Belgium (Lehtonen, 1996; Smit et al., 2008).

Till this day, most fining studies made with grape pomace fibres have been conducted using small volumes of wine, in static conditions and moreover using long contact times. With the intention of moving closer to a winery approach and to accelerate the fining process, in this study, we have carried out a continuous-flow experience using an experimental column through which we continuously passed wine spiked with OTA, histamine and various selected pesticides. Fibres from three different grape varieties were tested as fining agents, and the results were compared with a commercial plant fibre.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Fining Trial

The fining experience was conducted using the four plant fibres, at 2 g/L, the highest concentration allowed by OIV (OIV-OENO 684A-2022): two white grape pomaces of different varieties (WGP1 and WGP2), a red grape pomace (RGP) and a commercial fibre of unknown origin (CoF) (Flowpure, Laffort, 33072, Bordeaux Cedex, France), although previous studies have shown that this last fibre presents a different polysaccharide composition compared to those from grape (Osete-Alcaraz et al., 2024). WGP1 and WGP2 were both provided by AGROVIN S.A. (Alcazar de San Juan, Ciudad Real, Spain), and RGP was obtained purifying a pomace supplied by Explotaciones Hermanos Delgado SL (Socuellamos, Ciudad Real, Spain) with a hydroalcoholic solution (70%) for 48 h on a shaker at 250 rpm. Afterwards, they were dried at room temperature and crushed in an electric grinder with blades. All the plant fibres were passed through a 50 μm aperture sieve.

A young

Monastrell wine provided by Bodegas Salzillo (Jumilla, Spain), with a pH of 3.92, alcohol content of 13.5% and a total acidity of 4.5 mg/L, was spiked with OTA (4 µg/L), histamine (10 mg/L), and 7 pesticides, 6 fungicides and one insecticide (

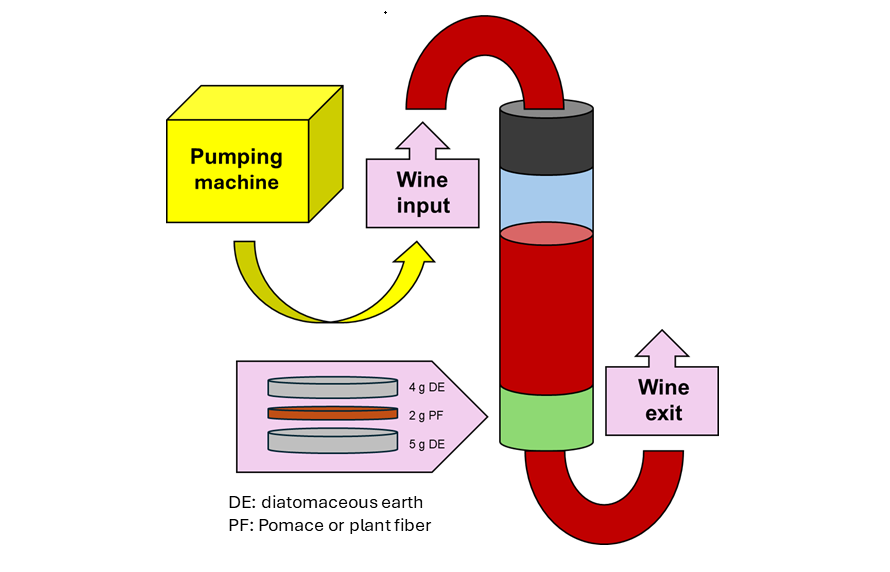

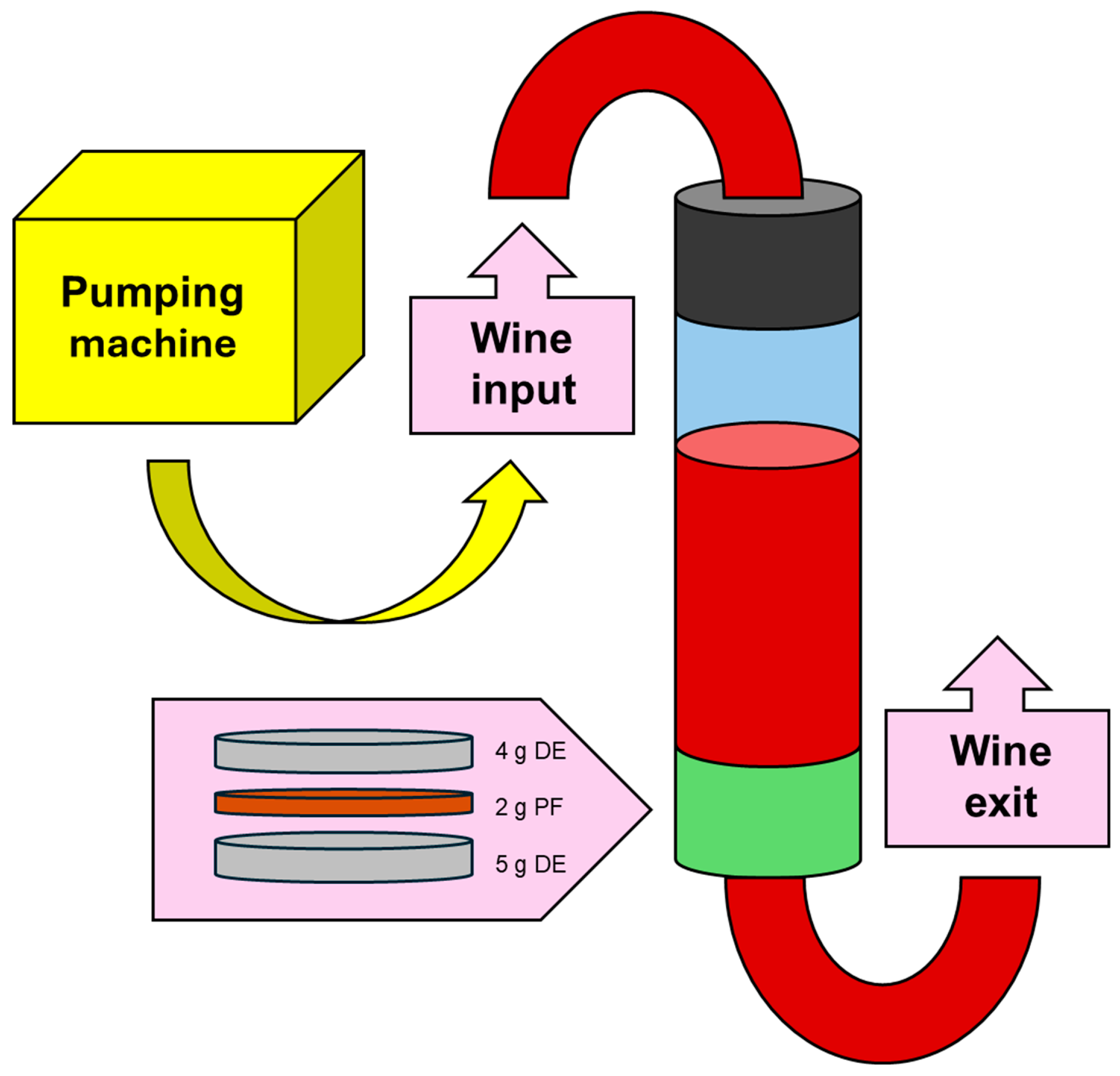

Table 1). The wine was passed through a filter in a column composed of diatomaceous earth (Radifil RP, AGROVIN S.A, Alcazar de San Juan, Ciudad Real, Spain) (9 grams) and the tested fibre (

Figure 1). The wine was pushed through the column by a pump machine, at a flow rate of 25 mL/min. For each treatment, one litre was used, and four fractions of 250 mL were collected during the filtration process (F1, 2, 3 and 4). After the fining treatment, the wine was filtered (0.45 µm nylon) before analyses.

2.2. Chromatic Parameter and Phenolic Compound Determination

Total anthocyanins (TA) and Polymeric Anthocyanins (PA) were determined following the methodology described by Ho et al. (2001). Total Tannins were measured by the precipitation method with methylcellulose (TT) (Smith, 2005) and Color Intensity (CI) was obtained by summing the absorbances at 620 nm, 520 nm, and 420 nm (Glories, 1984).

2.3. OTA Determination

To detect Ochratoxin-A the Biosystems Ochratoxin-A/Competitive ELISA KIT (ref: 14108) was employed. This kit allows to quantitatively detect OTA through an enzyme-linked competitive immunoassay, comparing the absorbance at 450 nm of the samples with a calibration curve done using the standards included in the kit. The calibration range was from 0 to 1 µg/L, so a dilution 1:4 was needed.

2.4. Histamine Determination

The determination and quantification of histamine was determined through a enzyme-linked competitive immunoassay using LDN HistaSure ELISA Fast Track (ref: FC E-3600). This kit allows to detect and quantify histamine concentration using their standards to stablish a calibration curve. Samples were measured at 450 nm. The calibration range was from 2.5 to 250 mg/L.

2.5. Pesticide Determination

The pesticides were analysed following QuEChERS protocol (Oliva et al., 2018) on a TQ QUANTIS® liquid-mass HPLC (LC-MS).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The data was statistically processed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a LSD (least significant difference) test (P < 0.05) in STATGRAPHICS Centurion XVI.3 (Statpoint Technologies, INC., The Plains, VA, USA) software.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. OTA Reduction

The results obtained by the ELISA analysis showed that all the fibres were capable of significantly reducing OTA content in the wine, by at least 50% (

Table 2). The commercial fibre (CoF) exhibited the greatest ability of reducing OTA, around 90%, while the pomace fibres showed a more limited ability, between 50-66%. RGP was proven to be statistically more effective reducing OTA than WGP1 and WGP2. These results contrast with those obtained in a previous experiment (Gómez-Plaza et al., 2024), in which, while CoF showed a similar performance reducing OTA, WGP1 (called SBF in that work) had a lower capacity of reducing this compound in red wine, by 30%. It is important to note that this experiment was carried out under different circumstances, that is, static conditions for 48 hours. Therefore, it seems that by using pomace fibres in a continuous filtration system, we can not only shorten the fining time but also achieve a greater reduction of OTA. These results are also comparable to the results published by Jiménez-Martínez et al. (2018), that reported an OTA reduction of 54-57% using fibres from grape origin. Nevertheless, in this work higher concentrations of fibres were used (13 mg/mL), under static conditions, and contact time lasted 21 days.

Multiple studies have been conducted using most common fining agents, such as gelatin, egg albumin, isinglass or bentonite (Fernandes et al., 2007; Anli et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2017; Jiménez-Martínez et al., 2018), and most of them reported lower levels of OTA reduction (10-34%) than these reported in this study and, moreover, with a high impact in the wine chromatic characteristics.

These results indicate that grape pomace fibres are an interesting OTA removal agent, capable of eliminating high quantities of OTA in wines, possibly due to their complex polysaccharide composition that provides numerous binding sites, allowing both hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions with OTA, that is a compound negatively charged at wine pH (3.2-3.6).

3.2. Histamine Reduction

The histamine reduction achieved by all the tested fibres was notorious. The one that achieved the greatest reduction was WGP2, with a 27% reduction, although its effect was not significantly different to that of CoF and WGP1, which led to a 20% and 16% of histamine reduction, respectively. RGP was the least effective reducing histamine, just a 12%, although this reduction was still statistically different with respect to control wine. In the previously conducted static test (Gómez-Plaza et al., 2024), WGP1 achieved a higher histamine reduction, 36%, whereas CoF led to a reduction of 12% of histamine content. In comparison, under the conditions used in this study, no significant differences of their reduction capacity were observed. Analysing the histamine reduction in F1,2,3 and 4, all fibres did not behave in the same way. The reduction achieved by WGP1 and RGP was constant from F1 to F4, while WGP2 and CoF were much more effective reducing histamine in F1 (the first 250 mL of wine recovered after passing through the column), than the rest of the fractions. WGP2 reduced its effectiveness in F2, F3, and F4, but the histamine reduction level of these fraction was still between 21% and 27%, while CoF exhibit in F3 and F4 similar histamine levels to control, indicating a quick saturation of this fibre.

We could only find another study where fibres derived from grape pomace were used to reduce histamine in red wine (Jimenez-Martinez et al., 2018), and they reported histamine reduction levels of 10%, even when they used higher concentrations of fibre and during longer contact time. Histamine is positively charged at wine pH, which could allow its binding with different fining agents by ionic exchange or by hydrogen bonding type interactions (Amghouz et al., 2014).

Table 3.

Fining effect of using different plant fibres in a continuous filtration system on histamine (mg/L) in a red wine. Abbreviations: WGP1, white grape pomace fibre 1; WGP2, white grape pomace fibre 2; RGP, red grape pomace fibre; CoF, commercial fibre.

Table 3.

Fining effect of using different plant fibres in a continuous filtration system on histamine (mg/L) in a red wine. Abbreviations: WGP1, white grape pomace fibre 1; WGP2, white grape pomace fibre 2; RGP, red grape pomace fibre; CoF, commercial fibre.

| |

Histamine (mg/L) |

| Control |

15.0±1.2c |

| WGP1F1 |

13.1±0.9 |

| WGP1F2 |

12.3±1.1 |

| WGP1F3 |

12.4±0.1 |

| WGP1F4 |

12.7±2.0 |

| Mean value |

12.6±1.0ab |

| RGPF1 |

14.2±0.4 |

| RGPF2 |

12.8±2.1 |

| RGPF3 |

11.5±2.4 |

| RGPF4 |

14.2±0.4 |

| Mean value |

13.2±1.3b |

| CoFF1 |

9.0±0.7 |

| CoFF2 |

11.0±0.6 |

| CoFF3 |

14.3±1.9 |

| CoFF4 |

13.7±1.4 |

| Mean value |

12.0±1.1ab |

| WGP2F1 |

9.4±1.1 |

| WGP2F2 |

11.7±0.7 |

| WGP2F3 |

11.0±1.0 |

| WGP2F4 |

11.9±0.3 |

| Mean value |

11.0±0.8a |

3.3. Pesticide Reduction

The pesticide reduction capacity of each fibre was measured using QuEChERS-LC-TSQ. The pesticides used in this study were six fungicides (iprovalicarb, fenhexamide, boscalid, tetraconazole, mepanipyrim and metrafenone) and one insecticide (imidacloprid).

In general, the statistical analysis showed that for fenhexamide, imidacloprid and iprovalicarb, all fibres produced a similar reduction in their content in wine, and they were less absorbed in the fibres than boscalid, mepanipyrim, metrafenone and tetraconazole (

Table 4). For these latter pesticides, WGP1 and CoF showed a similar behaviour in their retention capacity, being these two fibres more effective than RGP and WGP2.

In the case of fenhexamide, and for WGP1 and CoF, a larger reduction of this fungicide was found in F1, over 60% for CoF and over 70% for WGP1, while for RGP and WGP2 the reduction was around 25% in the same fraction. This effect is no longer observed in the following fractions for WGP1 and CoF, where the reduction percentages dropped considerably. This is the reason no statistically significant differences were observed in the overall effect of all fibres for this fungicide. For iprovalicarb, a similar result was observed, although with a lower reduction capacity for all fibres, with CoF and WGP1 presenting a retention of 30% of this pesticide in F1, while for WGP2 and RGP this decrease is way lower and with high variability. Imidacloprid behaviour is slightly different, CoF exhibited an interesting ability to reduce this insecticide, around 55% in F1, while WGP2 and WGP1 reduced it around 25-30%, also in F1. These fibres did not exhibit the same behaviour in the remaining fractions, showing lower retention values of this pesticides with the passage of more wine volume through the filter.

For mepanipyrim and tetraconazole, all the grape pomace fibres exhibited a similar behaviour, with a progressive decrease in the capacity of pesticide reduction as the millilitres of wine passing through the column increased, although for CoF, this decrease only was seen in the last wine fraction. WGP2 and RGP reduced its content 50% and 40% in F1, respectively, whereas WGP1 lowered the levels of both pesticides by 90% in the first fraction, resulting in a higher overall adsorption capacity of WGP1 for these two pesticides than WGP2 and RGP.

For boscalid, its retention in F1 ranged between 26% to 83%, showing a similar retention pattern compared to the previous pesticides, although with a more important decrease in the reduction percentage for all fibres as the volume of wine passing through the column increased. The behaviour of CoF was slightly different, its retention capacity only started to decrease at F4. This indicates that this fibre has a higher saturation threshold. For metrafenone, all fibres showed the same adsorption capacity during all the process, being WGP1 the most effective in its retention, achieving a decrease of 94%.

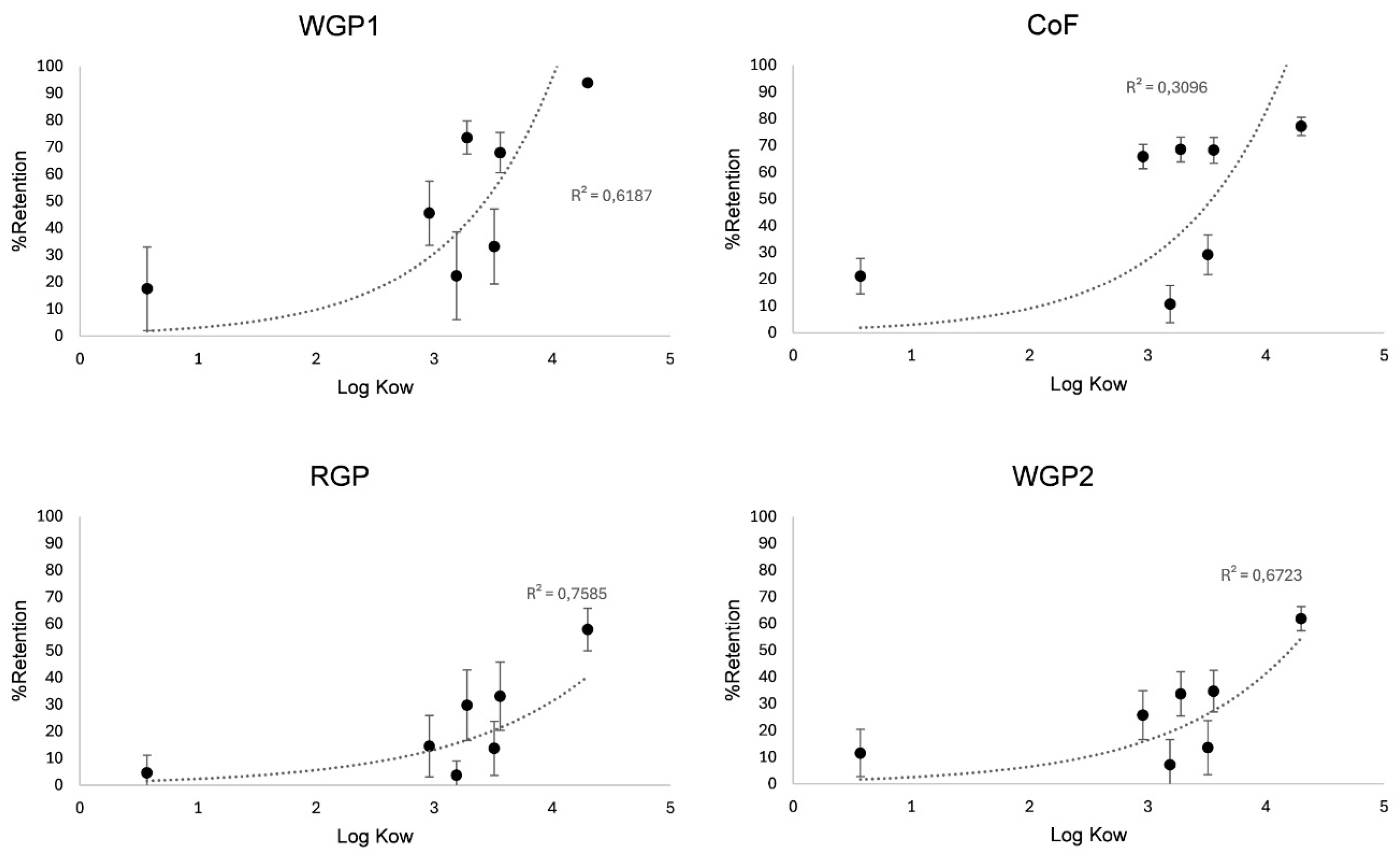

To better understand the reasons behind the differences in pesticide adsorption, it is crucial to examine the n-octanol/water partition coefficient (log Kow), the soil adsorption coefficient (Koc), and the water solubility of the pesticides involved (

Table 1). The removal of pesticides is strongly influenced by log Kow, which is closely linked to Koc, as can be appreciated in

Figure 2. Higher log Kow indicates a greater apolarity, meaning a stronger tendency to bind to solid substances and a lower solubility in water (Doulia et al., 2017). Boscalid, fenhexamide, iprovalicarb, mepanipyrim and tetraconazole exhibit moderate log Kow values (ranging from 3 to 3.5), while imidacloprid has a very low log Kow (<1) and metrafenone a high log Kow (>3.5). It is important to note that even though iprovalicarb has a moderate log Kow (3.19) its Koc is low in comparison with the rest of pesticide with a similar Log Kow (106), being even lower than imidacloprid Koc (225). With this understanding, we can explain why iprovalicarb and imidacloprid were the two pesticides less adsorbed by the fibres although WGP1 and CoF showed a certain capacity to retain them, especially during the first 250 mL of wine passing through the column (F1), so they can be considered an useful tool to reduce these pesticides. For boscalid, mepanipyrim, tetraconazole and metrafenone the reduction capacity seemed to be strongly correlated to their Log Kow, which explains why metrafenone was the one who showed the greatest affinity for all fibres.

In a previous work already mentioned above (Gómez-Plaza et al., 2024), WGP1 and CoF already proved their efficacy in removing these pesticides under static conditions, although we have observed some differences. WGP1 improved its performance working under continuous conditions as those used in this trial, increasing the ability to reduce tetraconazole (from 42% to 68%), mepanipyrim (from 50% to 74%) and metrafenone (from 57% to 94%) while its ability of reducing fenhexamide, imidacloprid and boscalid remained very similar. Only for iprovalicarb did its performance decreased (from 42% to 22%). This could be due to this pesticide needing more contact time to bind to the fibres. As regard CoF, it was observed that its performance only improved for mepanipyrim (from 56% to 68%) and metrafenone (from 69% to 77%), while for the rest of the pesticides its effectivity in reducing their concentration in wines remained similar, except for iprovalicarb (from 38% to 10%) and fenhexamide (from 43% to 29%), where it decreased.

CoF was used in Austrian red wines as a fining agent in a previous work (Philipp et al., 2021), working in static conditions and with a contact time of 18 h and a doses of 2 g/L. In this study, CoF did not significantly reduced mepanipyrim and fenhexamide, while in our study we found a reduction of 69% and 29%, respectively. Also, they reported a 50% boscalid reduction capacity, while we obtained in our study reduction levels of 66%.

3.4. Effect in the Chromatic Parameters and Phenolic Compounds of Wine

Although sometimes one of the objectives of fining may be to the reduction of wine tannins, mainly because a large concentration of these compounds is related to a high wine astringency and bitterness, most of the times, one of the main concerns during the fining step in red winemaking is to achieve an effective wine fining without modifying its chromatic parameters to a considerable extent. To check the effect of this fining system in wine color we measured Total Polyphenol Index (TP), Colour Index (CI), Total Anthocyanins (TA), Polymeric Anthocyanins (PA) and Total Tannins (TT).

The results showed that CoF and WGP1 were the only treatments that significantly reduced CI (

Table 5). As we can see in the data of F1,2,3 and 4, the F1 is always the most affected in terms of color losses and this is especially noticeable for CoF, with an CI reduction of 13%. However, F2, F3 and F4 did not produce changes in values of this parameter with respect to the control. The values of TA and PA exhibit a similar pattern as CI, the main decrease is also observed in F1 while the other fraction values were similar to the control. Once again, CoF exhibited the highest reduction of these parameters, reducing their content in a 16% in F1. Overall, the affinity of the grape pomace fibres for anthocyanins, and therefore its effect on color reduction, appears to be weak, while in the case of CoF, it seems that the fibre quickly saturates as the wine flows through it. In other studies where grape pomace fibres were used (Guerrero et al., 2013; Jimenez-Martinez et al., 2019), a bigger impact in the chromatic characteristics were observed, of around 10-12% of reduction of TA, probably due to the use of a higher fibre dose (5 and 6 mg/mL).

Tannins are important wine compounds and usually they are the compounds effected the most during the fining process with grape pomace fibres. This can be either favourable or detriment to wine quality. For example, with an excess of tannins, the use of fibres could be a tool to reduce the astringent of these compounds.

All the tested fibres reduced the total tannin content, within a range between 22% to 26%, being again CoF the one with higher impact in their concentration. The reduction of tannins was maintained with small variations in the four fractions, indicating that the fibres did not saturate as quickly, as for anthocyanins. Only when CoF was used, a decrease in its adsorption capacity between F1 and F2,3 and 4 was observed, although the reduction of tannins in F1 was of 36%. All these results match with what was observed in the TP levels, where the greatest reduction occurs in CoF, being this fibre the one that affects the most the chromatic parameters of the wine.

The ability of WGP1 and CoF of interacting and binding the phenolic compounds of red wine was also tested previously (Osete-Alcaraz et al., 2024) in static conditions for 48h, at the same concentration. Under these circumstances, the reduction of tannins was very similar for CoF and slightly lower for WGP1, while both fibres had more impact in the anthocyanin content and consequently in colour. So, it seems that lower contact time doesn´t affect that much the binding of tannins while could prevent anthocyanin binding and their consequent loss. Padayachee et al., (2012) proposed that anthocyanins react and bind with cell walls in two steps, initially via ionic and hydrophobic interactions, in a step that apparently is quick, followed by an apparent slowed step consisting of further anthocyanin pile-up in the attached layer. This could explain why the reduction of anthocyanins was lower in this study than in those with longer contact time.

Jimenez-Martinez et al. (2019) reported similar reduction of tannin through methylcellulose precipitation using Monastrell grape pomace fibre, of 21%, using a 6 mg/mL concentration during 5 days of contact.

Most studies with grape pomace fibres done before this used whether longer contact time, higher fibre concentrations, or both, and in those conditions, the reduction of tannins achieved was either similar o lower, and with a higher impact in wine chromatic characteristics. These results indicate that the continuous filtration system could be the most suitable system to use these fibres with the aim of reducing tannins, as it would allow to reduce the used dose (and in this way match the dose approved by the OIV), and the contact time.

It is also remarkable that all used grape fibres reduced tannins in a similar way, which contrasts with previously reported results (Guerrero et al., 2013; Jimenez-Martinez et al., 2019), where tannin reduction was more influenced by the grape variety used to obtain the fibre.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we aimed for the first time to investigate and better understand the potential using grape pomace fibres, working in a continuous system, as a fining agent to reduce wine contaminants, such, as pesticides, OTA and histamine, while also taking into consideration the impact they had on wine chromatic parameters and phenolic compounds. Out of all the tested fibres, CoF followed by RGP, were the most successful reducing OTA, while CoF, WGP1 and WGP2, especially the latter, reduced the highest concentration of histamine in these working conditions. WGP1 and CoF demonstrated a remarkable ability of reducing most of the used pesticides. Both of these fibres were already tested in static conditions, and overall, in this study they proved to be equally or more effective in lowering contaminant levels, with a similar reduction of tannin, although CoF had a higher impact in wine color than WGP1. Probably, the reason the continuous system has been, overall, more effective than the static conditions, is that the wine is pushed through the full amount of fibre present in the filter, whereas in static, once the fibre precipitates, the interactions with the different wine components become very limited. This shows that grape pomace-derived fibres, may be a good alternative to be used as fining agent without producing important changes in the quality of red wine, which can be applied not only in static, but also in continuous filtration systems, closer to those used in the wine industry, allowing to reduce the fining time from days to hours, although further studies must be conducted to test the effect of these fibres using a larger industrial-scale filtration system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G.P., A.B.B.O., L.O.A.; Data curation, L.O.A; Formal analysis, L.O.A; Investigation, L.O.A, E.G.P, A.B.B.O, J.O.O, M.A.C; Methodology, L.O.A, E.G.P, A.B.B.O, J.O.O, M.A.C.; Resources, E.G.P, A.B.B.O, and R.J.F; Software, ; Supervision, E.G.P., A.B.B.O; Writing—Original draft, L.O.A; Writing—Review and editing, E.G.P and A.B.B.O; Funding acquisition, R.J.F., E.G.P and A.B.B.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was made possible by financial assistance of Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and FEDER Una manera de hacer Europa, Project PID2021-123115OB-C21. Ms. Lucía Osete-Alcaraz acknowledges the finantial suport of Fundación Séneca (Murcia) and AGROVIN S.A. for her fellowship.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. All the fibers used are experimental products and Ricardo Jurado, from Agrovin SA, only provided economical support due to its interest in the work. Agrovin has no actual financial interest or benefits related to this study.

References

- Amghouz, Z., Ancín-Azpilicueta, C., Burusco, K. K., García, J. R., Khainakov, S. A., Luquin, A., Nieto, R., & Garrido, J. J. (2014). Biogenic amines in wine: individual and competitive adsorption on a modified zirconium phosphate. Microporous and mesoporous materials, 197, 130-139.

- Anli, R. E., Vural, N., & Bayram, M. (2011). Removal of ochratoxin A (OTA) from naturally contaminated wines during the vinification process. Journal of the Institute of Brewing, 117(3), 456-461.

- Antonić, B., Jančíková, S., Dordević, D., & Tremlová, B. (2020). Grape pomace valorization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Foods, 9(11), 1627.

- Bindon, K. A., Bacic, A., & Kennedy, J. A. (2012). Tissue-specific and developmental modifications of grape cell walls influence the adsorption of proanthocyanidins. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 60(36), 9249-9260.

- Cabras, P., & Conte, E. (2001). Pesticide residues in grapes and wine in Italy. Food Additives & Contaminants, 18(10), 880-885.

- Comas-Basté, O., Sánchez-Pérez, S., Veciana-Nogués, M. T., Latorre-Moratalla, M., & Vidal-Carou, M. D. C. (2020). Histamine intolerance: The current state of the art. Biomolecules, 10(8), 1181.

- Cubaiu, L., Abbas, H., Dobson, A. D., Budroni, M., & Migheli, Q. (2012). A Saccharomyces cerevisiae wine strain inhibits growth and decreases ochratoxin A biosynthesis by Aspergillus carbonarius and Aspergillus ochraceus. Toxins, 4(12), 1468-1481.

- Doulia, D. S., Anagnos, E. K., Liapis, K. S., & Klimentzos, D. A. (2017). Effect of clarification process on the removal of pesticide residues in white wine. Food Control, 72, 134-144.

- Fernandes, A., Ratola, N., Cerdeira, A., Alves, A., & Venâncio, A. (2007). Changes in ochratoxin A concentration during winemaking. OENO One, 58(1), 92-96.

- Fontana, A. R., Rodríguez, I., Ramil, M., Altamirano, J. C., & Cela, R. (2011). Solid-phase extraction followed by liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry for the selective determination of fungicides in wine samples. Journal of Chromatography A, 1218(16), 2165-2175.

- Freire, L., Braga, P. A., Furtado, M. M., Delafiori, J., Dias-Audibert, F. L., Pereira, G. E., Reyes, F. G., Catharino, R. R., & Sant’Ana, A. S. (2020). From grape to wine: Fate of ochratoxin A during red, rose, and white winemaking process and the presence of ochratoxin derivatives in the final products. Food Control, 113, 107167.

- García-Lomillo, J., & González-SanJosé, M. L. (2017). Applications of wine pomace in the food industry: Approaches and functions. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 16(1), 3-22.

- Glories, Y. (1984). La couleur des vins rouges. lre partie: Les ´equilibres des anthocyanes et des tanins. OENO One, 18(3), 195–217.

- Gómez-Plaza, E., Osete-Alcaraz, L., Pérez-Méndoza, A.L., Cámara-Botía, M. A., Jurado-Fuentes, R., & Bautista-Ortín, A.B. (2024). Wine phenolic content influences the effectivity of plant fibers for reducing undesirable compounds in wine [poster]. In Vino Analytica Scientia (IVAS), Davis, California, USA. https://ivas2024.wixsite.com/ivas2024.

- Grazioli, B., Galli, R., Fumi, M. D., & Silva, A. (2006). Influence of winemaking on ochratoxin A content in red wines. In Mycotoxins and phycotoxins (pp. 271-277). Wageningen Academic.

- Greifová, G., Májeková, H., Greif, G., Body, P., Greifová, M., & Dubničková, M. (2017). Analysis of antimicrobial and immunomodulatory substances produced by heterofermentative Lactobacillus reuteri. Folia Microbiologica, 62, 515-524.

- Guerrero, R. F., Smith, P., & Bindon, K. A. (2013). Application of insoluble fibers in the fining of wine phenolics. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 61(18), 4424-4432.

- Guo, Y. Y., Yang, Y. P., Peng, Q., & Han, Y. (2015). Biogenic amines in wine: A review. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 50(7), 1523-1532.

- Herrero-Hernández, E., Andrades, M. S., Álvarez-Martín, A., Pose-Juan, E., Rodríguez-Cruz, M. S., & Sánchez-Martín, M. J. (2013). Occurrence of pesticides and some of their degradation products in waters in a Spanish wine region. Journal of Hydrology, 486, 234-245.

- Ho, P., Silva, M. D. C. M., & Hogg, T. A. (2001). Changes in colour and phenolic composition during the early stages of maturation of port in wood, stainless steel and glass. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 81(13), 1269–1280.

- Hocking, A. D., Su-lin, L. L., Kazi, B. A., Emmett, R. W., & Scott, E. S. (2007). Fungi and mycotoxins in vineyards and grape products. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 119(1-2), 84-88.

- Humbert, F., & Bonneff, É. (2013). La peste soit les pesticides. Que Choisir: Paris, France, 46-50.

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine. (2023). State of the World Vine and Wine Sector in 2023. https://www.oiv.int/OIV_STATE_OF_THE_WORLD_VINE_AND_WINE_SECTOR_IN_2023.

- Jiang, C., Shi, J., Chen, X., & Liu, Y. (2015). Effect of sulfur dioxide and ethanol concentration on fungal profile and ochratoxin a production by Aspergillus carbonarius during wine making. Food Control, 47, 656-663.

- Jiménez-Martínez, M. D., Gil-Muñoz, R., Gómez-Plaza, E., & Bautista-Ortín, A. B. (2018). Performance of purified grape pomace as a fining agent to reduce the levels of some contaminants from wine. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A, 35(6), 1061-1070.

- Jiménez-Martínez, M. D., Bautista-Ortín, A. B., Gil-Muñoz, R., & Gómez-Plaza, E. (2019). Fining with purified grape pomace. Effect of dose, contact time and varietal origin on the final wine phenolic composition. Food Chemistry, 271, 570-576.

- Kawashima, L. M., Vieira, A. P., & Soares, L. M. V. (2007). Fumonisin B1 and ochratoxin A in beers made in Brazil. Food Science and Technology, 27, 317-323.

- Kim, K. H., Kabir, E., & Jahan, S. A. (2017). Exposure to pesticides and the associated human health effects. Science of the Total Environment, 575, 525-535.

- Kokkinomagoulos, E., & Kandylis, P. (2020). Sustainable exploitation of by-products of vitivinicultural origin in winemaking. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute Proceedings, 67(1), 5.

- Košmerl, T., Šućur, S., & Prosen, H. (2013). Biogenic amines in red wine: The impact of technological processing of grape and wine. Acta Agriculturae Slovenica, 101(2), 249-261.

- Ladero, V., Calles-Enríquez, M., Fernández, M., & A. Alvarez, M. (2010). Toxicological effects of dietary biogenic amines. Current Nutrition & Food Science, 6(2), 145-156.

- Lehtonen, P. (1996). Determination of amines and amino acids in wine—a review. OENO One, 47(2), 127-133.

- López, R., Tenorio, C., Gutiérrez, A. R., Garde-Cerdán, T., Garijo, P., González-Arenzana, L., López-Alfaro, I., & Santamaría, P. (2012). Elaboration of Tempranillo wines at two different pHs. Influence on biogenic amine contents. Food Control, 25(2), 583-590.

- Oliva, J., Martínez, G., Cermeño, S., Motas, M., Barba, A., & Cámara, M. A. (2018). Influence of matrix on the bioavailability of nine fungicides in wine grape and red wine. European Food Research and Technology, 244, 1083-1090.

- Osete-Alcaraz, L., Gómez-Plaza, E., Jørgensen, B., Oliva, J., Cámara, M. A., Jurado, R., & Bautista-Ortín, A. B. (2024). The composition and structure of plant fibers affect their fining performance in wines. Food Chemistry, 460, 140657.

- Padayachee, A., Netzel, G., Netzel, M., Day, L., Zabaras, D., Mikkelsen, D., & Gidley, M. J. (2012). Binding of polyphenols to plant cell wall analogues–Part 1: Anthocyanins. Food Chemistry, 134(1), 155-161.

- Pfohl-Leszkowicz, A., & Manderville, R. A. (2007). Ochratoxin A: An overview on toxicity and carcinogenicity in animals and humans. Molecular nutrition & food research, 51(1), 61-99.

- Philipp, C., Eder, P., Hartmann, M., Patzl-Fischerleitner, E., & Eder, R. (2021). Plant fibers in comparison with other fining agents for the reduction of pesticide residues and the effect on the volatile profile of Austrian white and red wines. Applied Sciences, 11(12), 5365.

- Riba, A., Mokrane, S., Mathieu, F., Lebrihi, A., & Sabaou, N. (2008). Mycoflora and ochratoxin A producing strains of Aspergillus in Algerian wheat. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 122(1-2), 85-92.

- Smit, A. Y., Du Toit, W. J., & Du Toit, M. (2008). Biogenic amines in wine: Understanding the headache. South African Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 29(2), 109-127.

- Smith, P. A. (2005). Precipitation of tannin with methyl cellulose allows tannin quantification in grape and wine samples. Technical Review AWRI, 158, 3–7.

- Stoev, S. D. (2022). New evidences about the carcinogenic effects of ochratoxin A and possible prevention by target feed additives. Toxins, 14(6), 380.

- Sun, X., Niu, Y., Ma, T., Xu, P., Huang, W., & Zhan, J. (2017). Determination, content analysis and removal efficiency of fining agents on ochratoxin A in Chinese wines. Food Control, 73, 382-392.

- Tao, Y., Xie, S., Xu, F., Liu, A., Wang, Y., Chen, D., Pan, Y., Huang, L., Peng, D., Wang, X., & Yuan, Z. (2018). Ochratoxin A: Toxicity, oxidative stress and metabolism. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 112, 320-331.

- Tudi, M., Li, H., Li, H., Wang, L., Lyu, J., Yang, L., Tong, S., Yu, Q. J., Ruan, H. D., Atabila, A., Phung, D. T., Sadler, R., & Connell, D. (2022). Exposure routes and health risks associated with pesticide application. Toxics, 10(6), 335.

- Zhou, W., Li, M., & Achal, V. (2024). A comprehensive review on environmental and human health impacts of chemical pesticide usage. Emerging Contaminants, 100410.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the system used to perform fining in continuous conditions. Wine enters in a column impulse by a pumping machine. The column has two valves, one at the entry and one at the exit. Before the exit valve, a filter with plant fibres is set up, consisting of three layers: a base layer of 5 grams of diatomaceous earth, 2 grams of the fibre and 4 grams of diatomaceous earth on top. Abbreviations: DE, diatomaceous earth; PF, plant fibres.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the system used to perform fining in continuous conditions. Wine enters in a column impulse by a pumping machine. The column has two valves, one at the entry and one at the exit. Before the exit valve, a filter with plant fibres is set up, consisting of three layers: a base layer of 5 grams of diatomaceous earth, 2 grams of the fibre and 4 grams of diatomaceous earth on top. Abbreviations: DE, diatomaceous earth; PF, plant fibres.

Figure 2.

Effect of log Kow on pesticide removal during the fining of a red wine through a continuous filtration system using different plant fibres. Abbreviations: WGP1, white grape pomace fibre 1; WGP2, white grape pomace fibre 2; RGP, red grape pomace fibre; CoF, commercial fibre.

Figure 2.

Effect of log Kow on pesticide removal during the fining of a red wine through a continuous filtration system using different plant fibres. Abbreviations: WGP1, white grape pomace fibre 1; WGP2, white grape pomace fibre 2; RGP, red grape pomace fibre; CoF, commercial fibre.

Table 1.

Concentrations used of each pesticide, their chemical groups, water solubility, Log Kow (pesticide hydrophobicity) and Koc (soil adsorption coefficient).

Table 1.

Concentrations used of each pesticide, their chemical groups, water solubility, Log Kow (pesticide hydrophobicity) and Koc (soil adsorption coefficient).

| Pesticide |

Chemical group |

Type |

Solubility (mg/L) |

Log Kow |

Koc |

Concentration (mg/Kg) |

| Imidacloprid |

Neonicotinoid |

Insecticide |

610 |

0.57 |

225 |

0.7 |

| Iprovalicarb |

Valinamidecarbamate |

Fungicide |

17.8 |

3.19 |

106 |

2.0 |

| Fenhexamide |

Anilide fungicide |

Fungicide |

20 |

3.51 |

446-1226 |

5.0 |

| Boscalid |

Pyridinecarboxamide |

Fungicide |

4.6 |

2.96 |

507-1110 |

5.0 |

| Tetraconazole |

Triazole |

Fungicide |

156 |

3.56 |

531-1922 |

0.5 |

| Mepanipyrim |

Aminopyrimidines |

Fungicide |

3.1 |

3.28 |

875 |

2.0 |

| Metrafenone |

Benzophenone |

Fungicide |

0.49 |

4.30 |

7061 |

5.0 |

Table 2.

Fining effect of using different plant fibres in a continuous filtration system on OTA (µg/L) in a red wine. Abbreviations: WGP1, white grape pomace fibre 1; WGP2, white grape pomace fibre 2; RGP, red grape pomace fibre; CoF, commercial fibre.

Table 2.

Fining effect of using different plant fibres in a continuous filtration system on OTA (µg/L) in a red wine. Abbreviations: WGP1, white grape pomace fibre 1; WGP2, white grape pomace fibre 2; RGP, red grape pomace fibre; CoF, commercial fibre.

| |

OTA (µg/L) |

| Control |

3.8±0.1d |

| WGP1F1 |

0.0±0.0 |

| WGP1F2 |

1.9±0.0 |

| WGP1F3 |

2.7±0.3 |

| WGP1F4 |

2.3±0.3 |

| Mean value |

1.7±0.2c |

| RGPF1 |

0.9±0.3 |

| RGPF2 |

1.0±0.2 |

| RGPF3 |

1.5±0.2 |

| RGPF4 |

1.8±0.1 |

| Mean value |

1.3±0.2b |

| CoFF1 |

0.0±0.0 |

| CoFF2 |

0.0±0.0 |

| CoFF3 |

0.6±0.0 |

| CoFF4 |

1.0±0.1 |

| Mean value |

0.4±0.0a |

| WGP2F1 |

1.5±0.1 |

| WGP2F2 |

2.0±0.1 |

| WGP2F3 |

2.0±0.1 |

| WGP2F4 |

2.0±0.1 |

| Mean value |

1.9±0.1c |

Table 4.

Fining effect of using different plant fibres in a continuous filtration system on pesticides (represented in percentage retention) in a red wine. Abbreviations: WGP1, white grape pomace fibre 1; WGP2, white grape pomace fibre 2; RGP, red grape pomace fibre; CoF, commercial fibre.

Table 4.

Fining effect of using different plant fibres in a continuous filtration system on pesticides (represented in percentage retention) in a red wine. Abbreviations: WGP1, white grape pomace fibre 1; WGP2, white grape pomace fibre 2; RGP, red grape pomace fibre; CoF, commercial fibre.

| %Retention |

Boscalid |

Fenhexamide |

Imidacloprid |

Iprovalicarb |

Mepanipyrim |

Metrafenone |

Tetraconazole |

| WGP1F1 |

83.0±3.9 |

73.7±4.3 |

29.1±13.1 |

36.2±13.3 |

91.4±1.7 |

95.9±0.7 |

90.7±1.7 |

| WGP1F2 |

38.5±5.7 |

13.2±12.5 |

4.3±6.1 |

7.4±10.5 |

82.4±2.3 |

94.4±0.7 |

78.1±2.7 |

| WGP1F3 |

28.8±17.3 |

18.7±12.5 |

15.1±16.7 |

18.4±19.5 |

66.4±6.9 |

93.6±1.3 |

56.3±9.6 |

| WGP1F4 |

31.9±20.6 |

27.3±20.2 |

21.5±26.2 |

27.1±21.8 |

54.0±13.6 |

91.6±2.6 |

46.9±15.8 |

| Mean value |

45.5±11.9bc |

33.2±13.9ª |

17.5±15.5ª |

22.3±16.3ª |

73.6±6.1b |

93.9±1.3c |

68.0±7.4b |

| RGPF1 |

26.5±3.7 |

25.6±3.4 |

2.0±2.9 |

1.6±2.2 |

38.2±5.7 |

65.0±2.9 |

43.3±4.7 |

| RGPF2 |

19.0±24.1 |

13.9±19.6 |

10.1±14.3 |

8.6±12.2 |

35.4±20.1 |

54.8±13.8 |

39.9±18.7 |

| RGPF3 |

3.7±5.2 |

5.3±3.1 |

0.0±0.0 |

0.0±0.0 |

29.1±2.6 |

56.2±2.1 |

31.1±3.6 |

| RGPF4 |

9.1±12.8 |

10.0±14.2 |

6.4±9.0 |

4.8±6.8 |

16.9±23.8 |

55.7±12.8 |

18.2±23.7 |

| Mean value |

14.5±11.4ª |

13.7±10.1ª |

4.6±6.5ª |

3.7±5.3ª |

29.8±13.2ª |

57.9±7.9ª |

33.1±12.7ª |

| CoFF1 |

76.1±5.0 |

60.8±5.1 |

56.2±7.3 |

31.4±11.7 |

76.7±3.6 |

82.5±2.7 |

78.3±3.5 |

| CoFF2 |

70.6±0.1 |

36.7±4.9 |

18.6±5.0 |

1.5±2.2 |

72.7±2.0 |

80.0±2.2 |

73.7±1.8 |

| CoFF3 |

70.3±8.4 |

19.2±19.7 |

9.9±14.0 |

9.8±13.9 |

71.5±7.7 |

79.9±4.9 |

71.2±7.7 |

| CoFF4 |

46.4±4.8 |

0.0±0.0 |

0.0±0.0 |

0.0±0.0 |

53.2±5.2 |

66.3±3.9 |

49.8±6.1 |

| Mean value |

65.9±4.6c |

29.2±7.4ª |

21.2±6.6ª |

10.7±6.9ª |

68.5±4.6b |

77.2±3.4b |

68.3±4.8b |

| WGP2F1 |

40.9±4.0 |

27.6±9.0 |

25.1±5.5. |

7.9±8.3 |

44.2±4.8 |

66.3±2.6 |

48.1±4.2 |

| WGP2F2 |

29.7±19.3 |

14.1±19.9 |

13.3±18.8 |

12.9±18.3 |

39.8±16.4 |

62.1±9.0 |

40.8±16.2 |

| WGP2F3 |

18.6±5.2 |

6.3±2.6 |

3.5±5.0 |

3.3±4.6 |

28.3±4.3 |

60.9±3.1 |

28.4±4.1 |

| WGP2F4 |

13.8±8.2 |

6.4±9.0 |

4.3±6.1 |

4.6±6.5 |

22.8±7.7 |

58.2±3.5 |

21.5±6.7 |

| Mean value |

25.7±9.2ab |

13.6±10.2ª |

11.6±8.9ª |

7.2±9.4ª |

33.8±8.3ª |

61.9±4.5ª |

34.7±7.8ª |

Table 5.

Fining effect of using different plant fibres in a continuous filtration system on the chromatic parameters and phenolic compounds of a red wine. Abbreviations: WGP1, white grape pomace fibre 1; WGP2, white grape pomace fibre 2; RGP, red grape pomace fibre; CoF, commercial fibre; CI, Color Index; TP, Total Polyphenols; TA, Total Anthocyanins; PA, Polymeric Anthocyanins; TT, Total Tannins.

Table 5.

Fining effect of using different plant fibres in a continuous filtration system on the chromatic parameters and phenolic compounds of a red wine. Abbreviations: WGP1, white grape pomace fibre 1; WGP2, white grape pomace fibre 2; RGP, red grape pomace fibre; CoF, commercial fibre; CI, Color Index; TP, Total Polyphenols; TA, Total Anthocyanins; PA, Polymeric Anthocyanins; TT, Total Tannins.

| |

CI |

TP |

TA (mg/L) |

PA (mg/L) |

TT (mg/L) |

| Control |

12.3±0.1cd |

85.7±0.1d |

220.3±3.1c |

35.8±0.2c |

2359.6±14.2c |

| WGP1F1 |

11.7±0.0 |

80.8±0.4 |

207.0±5.7 |

34.0±0.2 |

1829.5±5.2 |

| WGP1F2 |

12.3±0.1 |

85.3±0.6 |

217.5±0.7 |

35.3±0.5 |

1789.3±4.8 |

| WGP1F3 |

12.3±0.0 |

84.4±0.3 |

213.5±7.8 |

35.5±0.4 |

1873.4±3.4 |

| WGP1F4 |

12.3±0.1 |

84.1±0.1 |

221.5±2.1 |

35.5±0.4 |

1767.7±36.9 |

| Mean value |

12.1±0.0b |

83.6±0.4b |

214.9±4.1b |

35.1±0.4b |

1815±12.6b |

| RGPF1 |

11.7±0.0 |

80.3±0.7 |

201.0±1.4 |

33.9±0.7 |

1744.8±33.8 |

| RGPF2 |

12.3±0.1 |

83.8±1.0 |

220.0±0.0 |

35.2±0.5 |

1803.3±10.0 |

| RGPF3 |

12.4±0.1 |

86.0±1.6 |

218.0±2.8 |

35.6±0.5 |

1893.5±17.2 |

| RGPF4 |

12.4±0.1 |

85.5±0.3 |

217.0±1.4 |

35.7±0.4 |

1960.4±99.4 |

| Mean value |

12.2±0.1bc |

84.2±0.9b |

214.0±1.4b |

35.1±0.5b |

1850.5±40.1b |

| CoFF1 |

10.7±0.1 |

76.3±0.6 |

185.0±2.8 |

30.1±0.3 |

1520.7±101.7 |

| CoFF2 |

12.3±0.1 |

84.2±0.5 |

210.0±2.8 |

35.3±0.1 |

1848.7±27.7 |

| CoFF3 |

12.6±0.1 |

84.8±0.4 |

217.5±2.1 |

36.3±0.5 |

1790.3±51.0 |

| CoFF4 |

12.6±0.0 |

86.1±0.5 |

216.5±4.9 |

36.5±0.6 |

1851.3±10.0 |

| Mean value |

12.0±0.1a |

82.8±0.5a |

207.3±3.2a |

34.5±0.4a |

1752.7±47.6a |

| WGP2F1 |

11.7±0.0 |

80.7±0.8 |

201.0±4.2 |

33.0±0.2 |

1914.3±46.7 |

| WGP2F2 |

12.5±0.1 |

85.2±1.3 |

214.5±4.9 |

35.9±0.3 |

1857.1±17.5 |

| WGP2F3 |

12.6±0.0 |

86.4±0.1 |

211.5±4.9 |

35.9±0.0 |

1810.9±54.4 |

| WGP2F4 |

12.7±0.1 |

86.5±1.3 |

221.0±2.8 |

36.0±0.0 |

1802.1±9.2 |

| Mean value |

12.4±0.0d |

84.7±0.9c |

212.0±4.2b |

35.2±0.1b |

1846.1±32.0b |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).