Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis of Tunnel Face Support Pressure

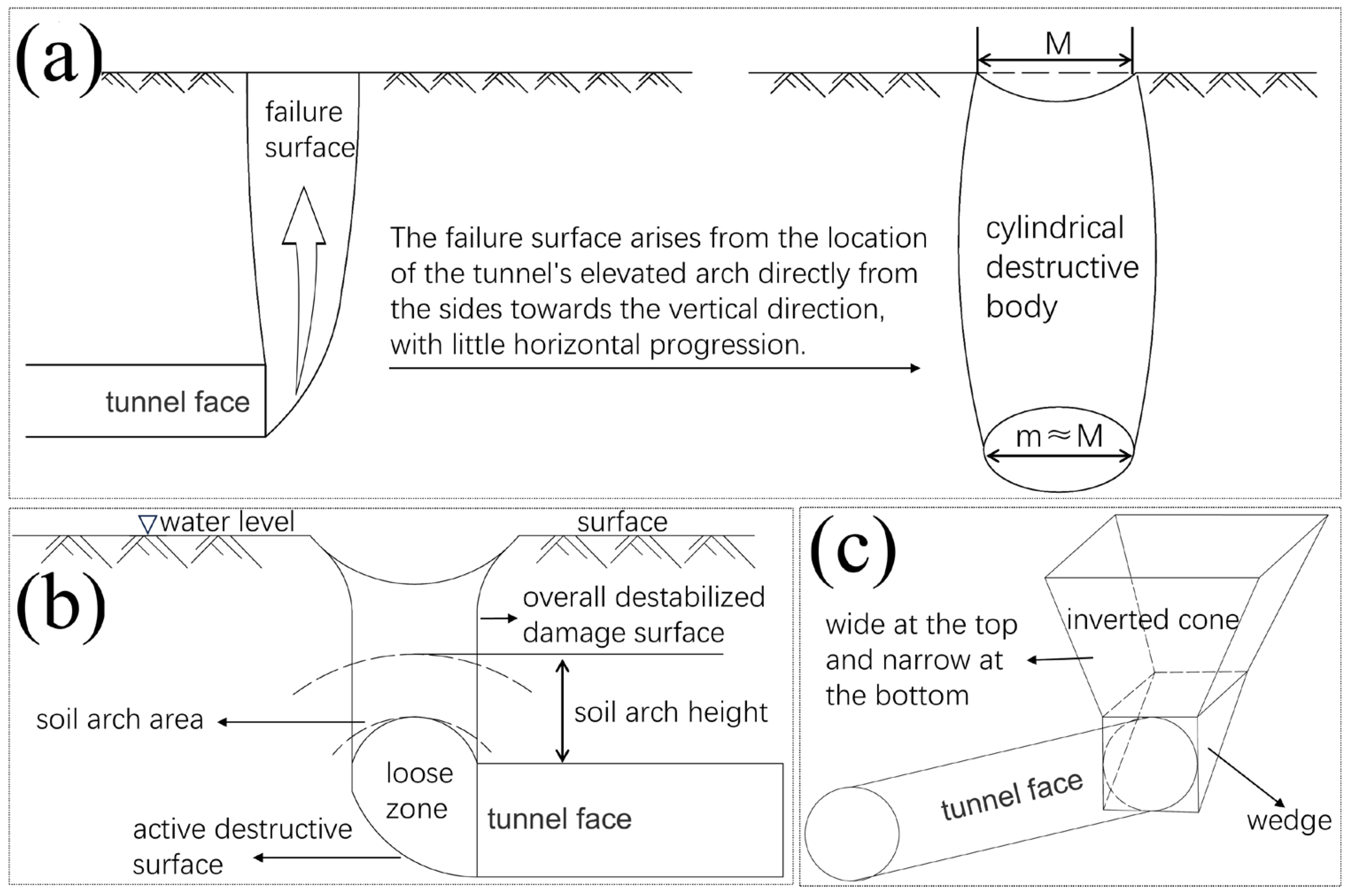

2.1. Mechanism of Support Pressure on the Tunnel Face of the Pipe-Jacking

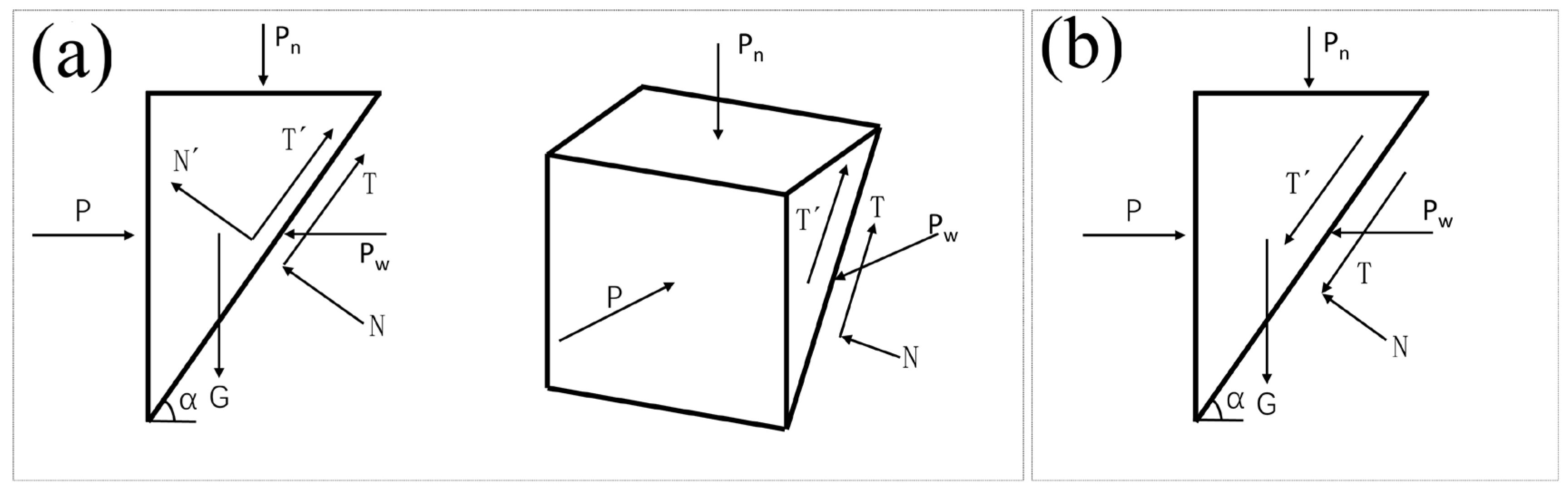

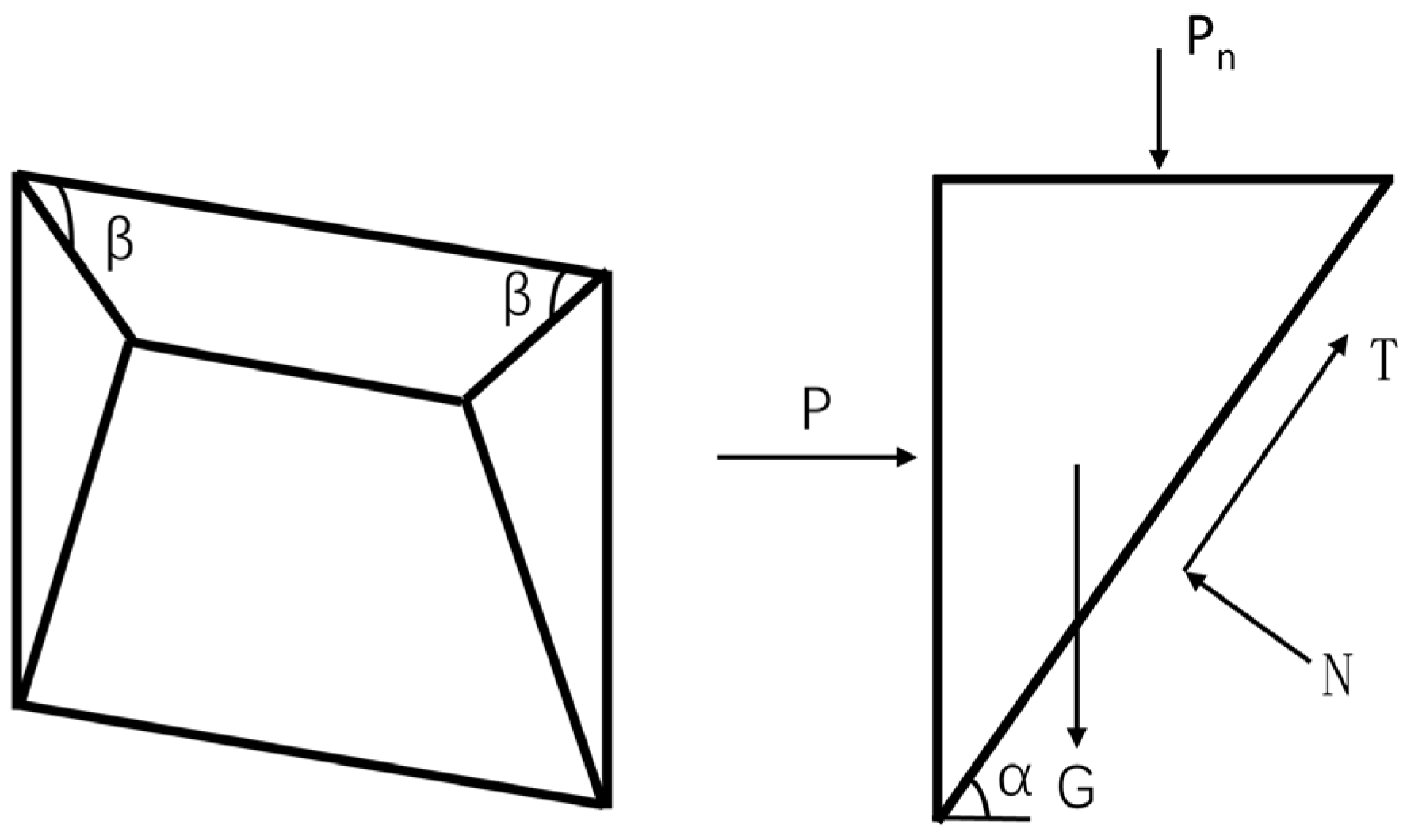

2.2. Theoretical Calculation Principle of Tunnel Face Support Pressure

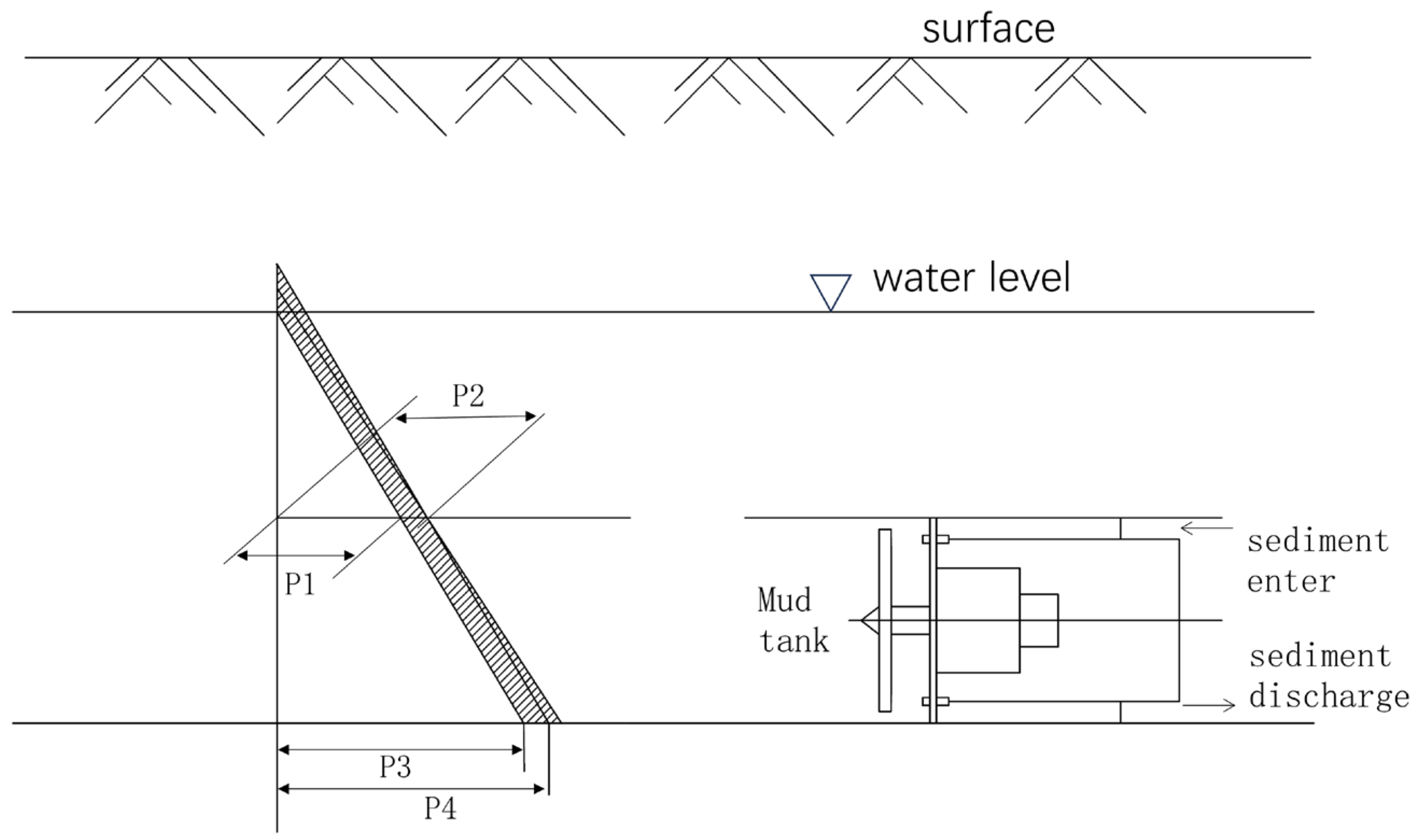

2.3. Calculation and Analysis of the Optimal Value of Support Pressure

3. Numerical Simulation and Analysis of Support Pressure on Tunnel Face

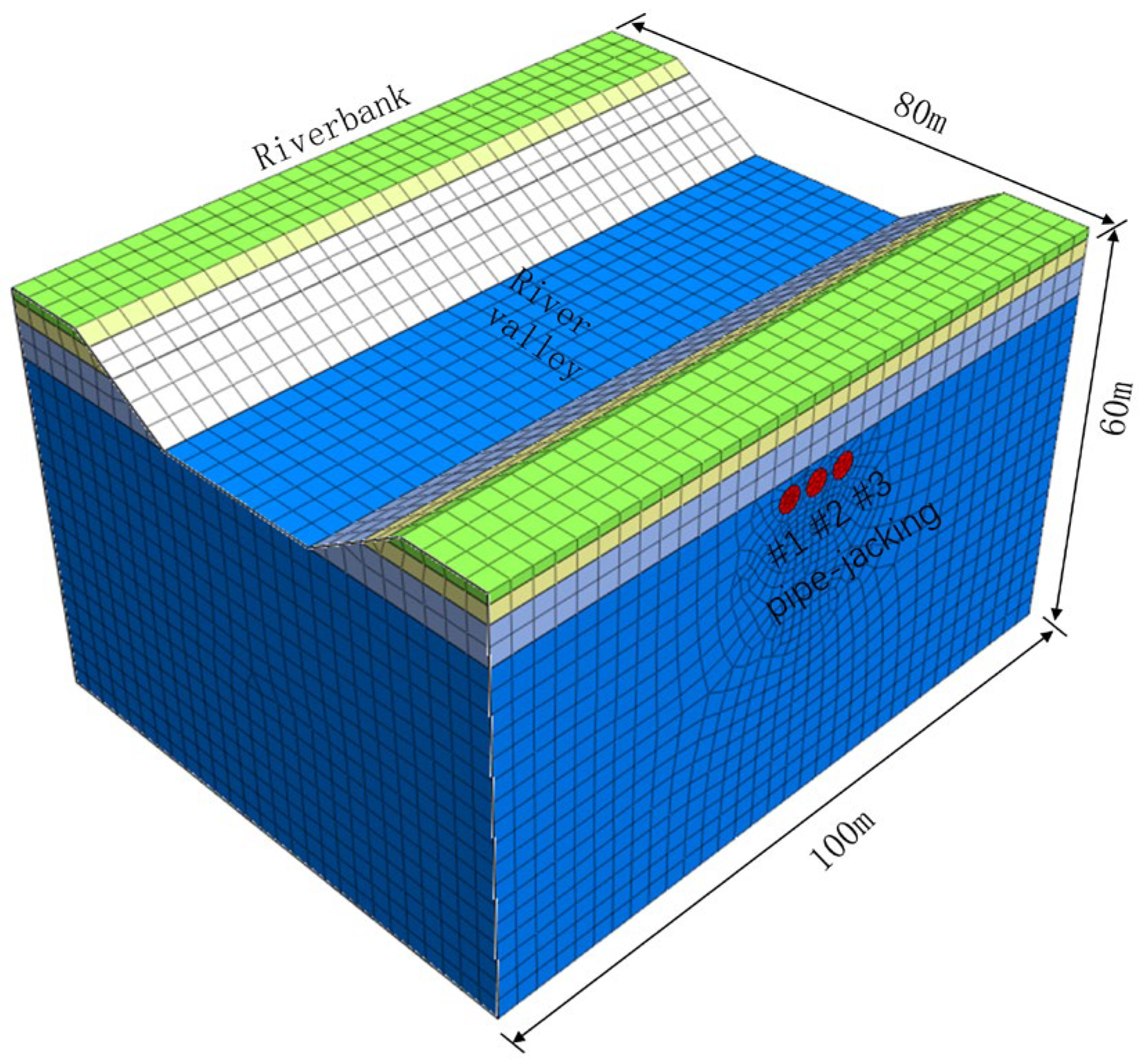

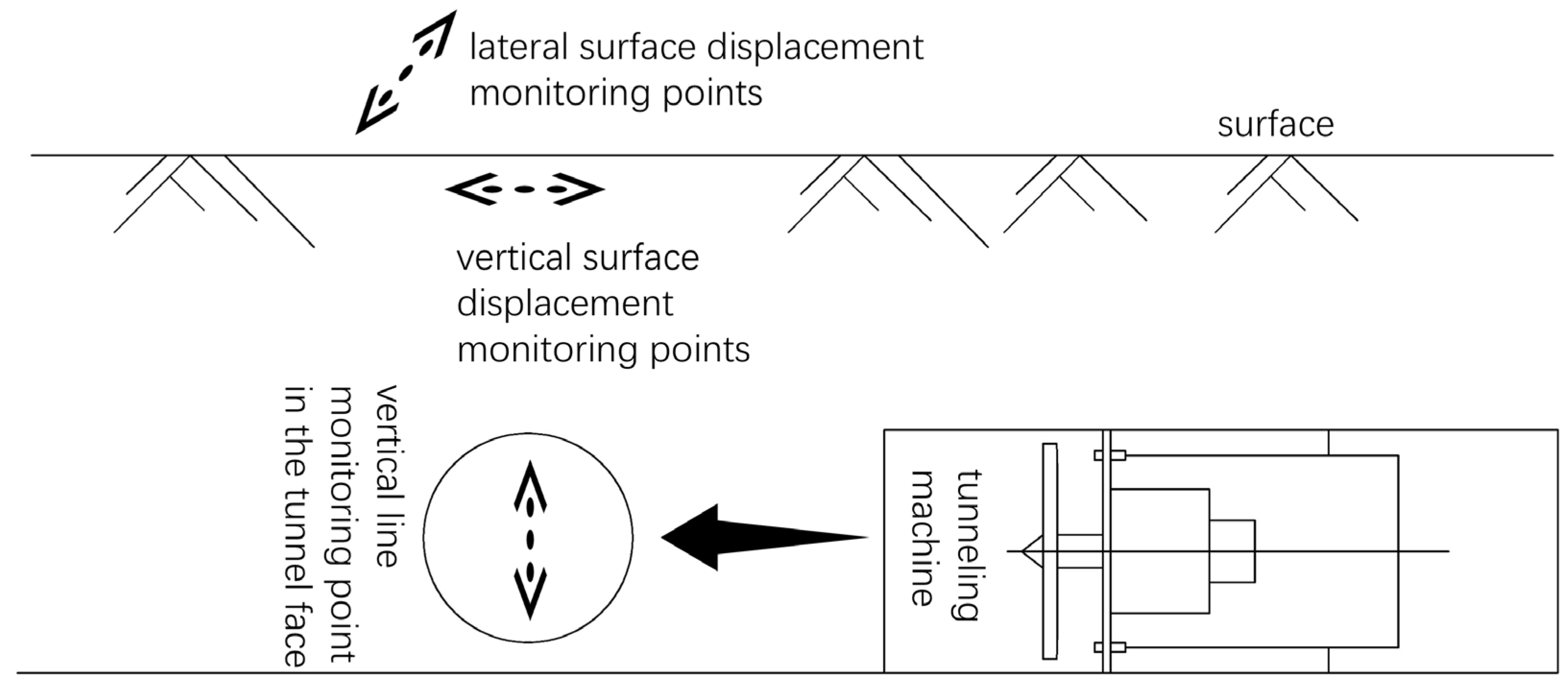

3.1. Simulation Model and Basic Assumptions

3.2. Simulation Conditions and Implementation Steps

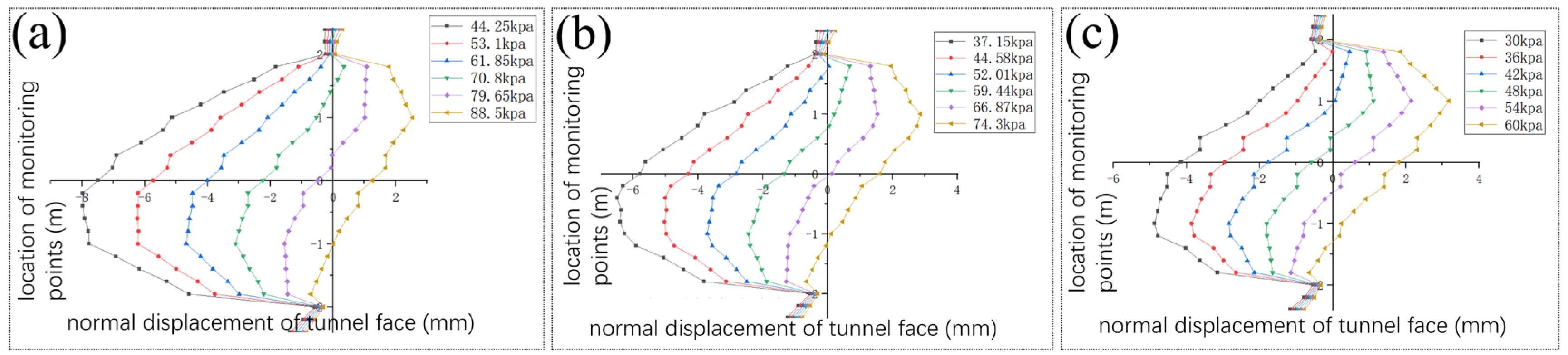

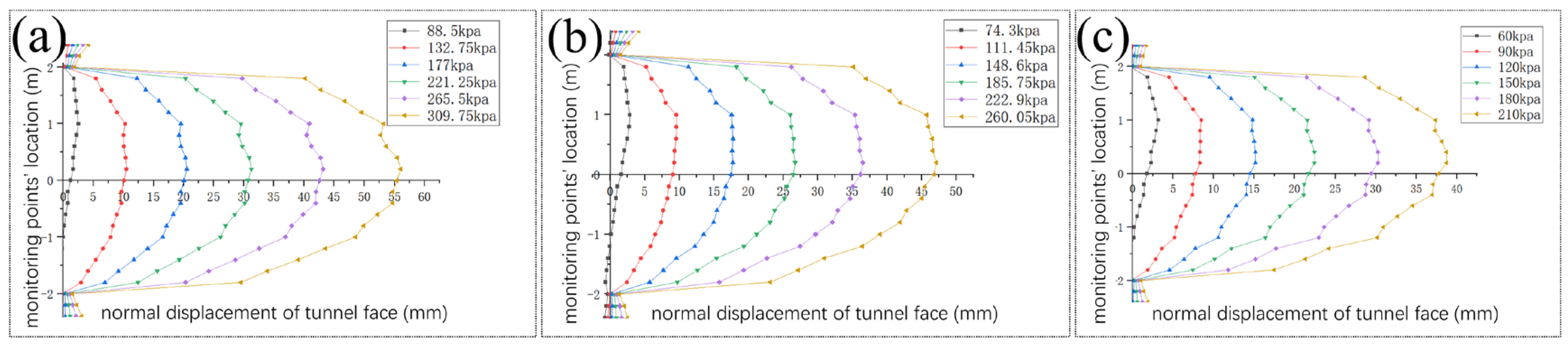

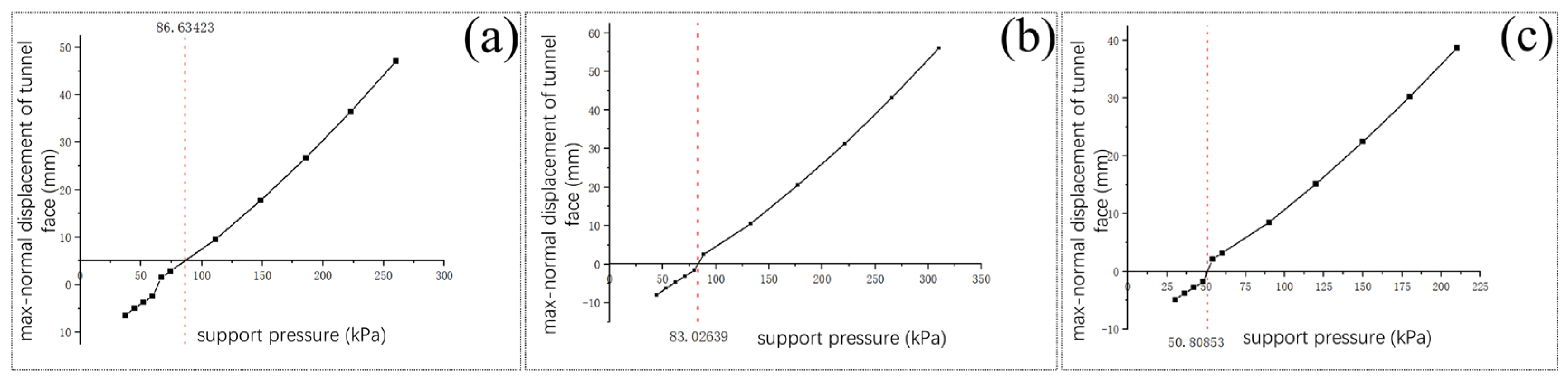

3.3. Analysis of Calculation Results

4. Engineering Case Study

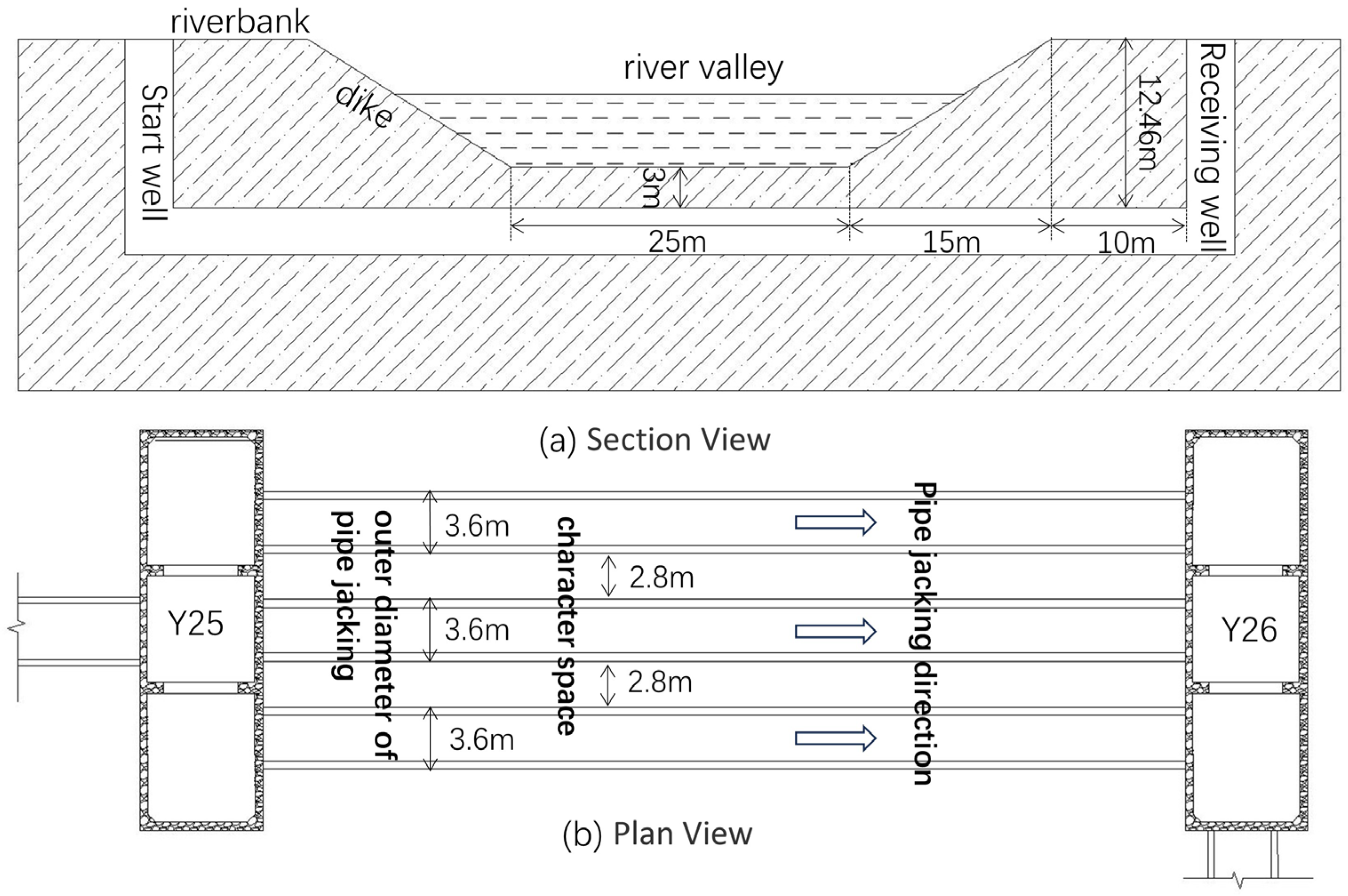

4.1. Engineering Background

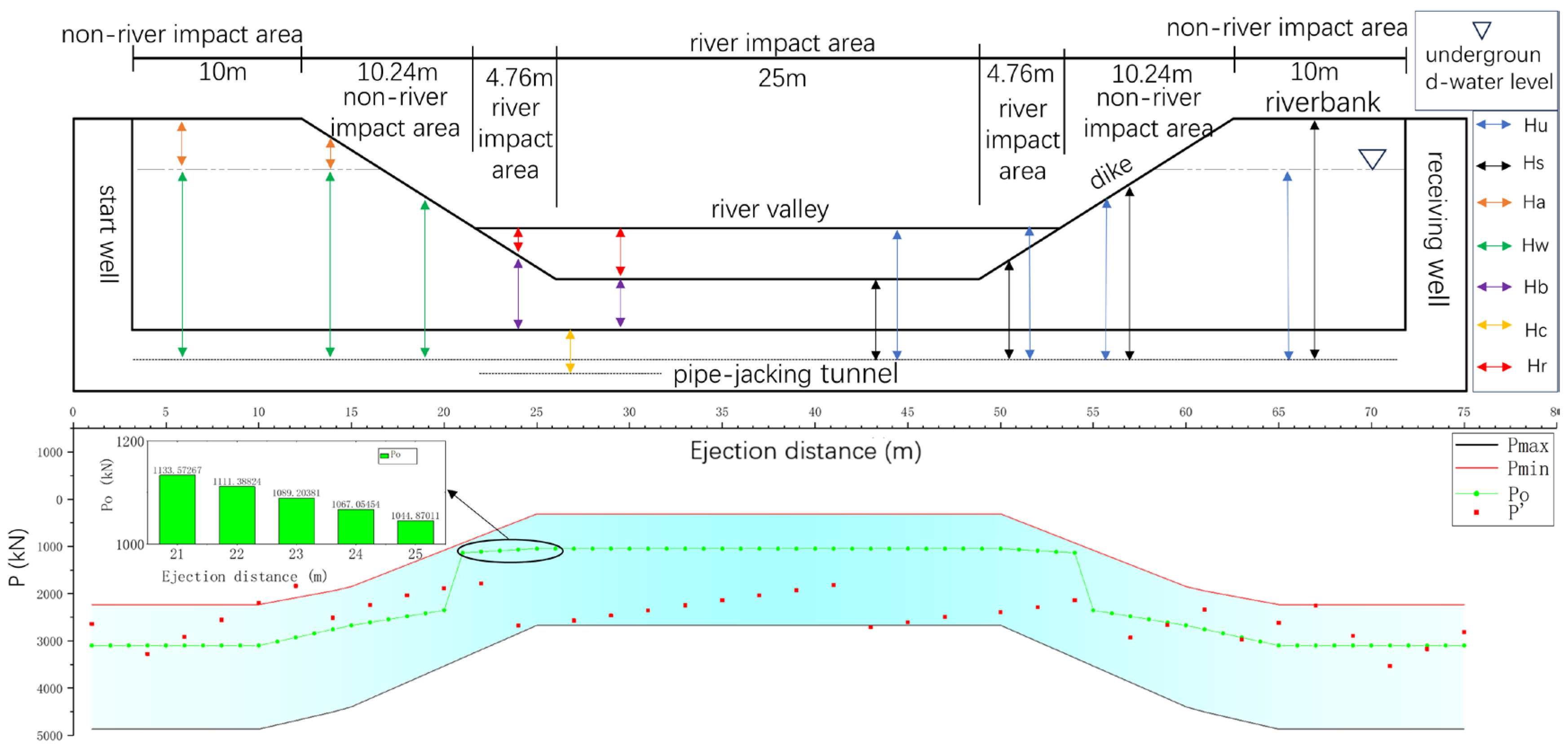

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Engineering Effect and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, P.; Liu, X.; Deng, Z.; Liang, N.; Du, L.; Du, H.; Huang, Y.; Deng, L.; Yang, G. , Study on the pipe friction resistance in long-distance rock pipe jacking engineering. Underground Space 2023, 9, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiung, B.-C. B.; Yang, K.-H.; Aila, W.; Ge, L. , Evaluation of the wall deflections of a deep excavation in Central Jakarta using three-dimensional modeling. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 2018, 72, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, D.; Kalos, A.; Kavvadas, M. , 3D Numerical Investigation of Face Stability in Tunnels With Unsupported Face. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering 2022, 40(1), 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Ni, P.; Barla, M. , Analysis of jacking forces during pipe jacking in granular materials using particle methods. Underground Space 2019, 4(4), 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Yin, X.; Tang, L.; Chen, Y. , Centrifugal model tests on face failure of earth pressure balance shield induced by steady state seepage in saturated sandy silt ground. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 2018, 81, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Jia, P.; Zhao, W.; Zheng, Q.; Du, X.; Tang, X. , Longitudinal mechanical force mechanism and structural design of steel tube slab structures. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 2023, 132, 104883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.-p.; Li, J.; Kong, L.-g.; Tang, L.-j. , Experimental study on face instability of shield tunnel in sand. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 2013, 33, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengt B., Broms; Bennermark, H. , Stability of Clay at Vertical Openings. Journal of the Soil Mechanics and Foundations Division 1967, 96(1), 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, R. B.; Hendron, A. J.; Mohraz, B. Deep excavations and tunneling in soft ground. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering. Mexico City:state of the art report, 1969, 225-290. https://trid.trb.org/view/125926.

- Davis, E. H.; Gunn, M. J.; Mair, R. J.; Seneviratine, H. N. The stability of shallow tunnels and underground openings in cohesive material. 1980, 30 (4), 397-416. [CrossRef]

- Leca, E.; Dormieux, L. , Upper and lower bound solutions for the face stability of shallow circular tunnels in frictional material. 1990, 40 (4), 581-606. [CrossRef]

- Soubra, A. H. In Kinematical approach to the face stability analysis of shallow circular tunnels, 2000. https://hal.science/hal-01008370v1.

- Li, P.; Wang, F.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z. , Face stability analysis of a shallow tunnel in the saturated and multilayered soils in short-term condition. Computers and Geotechnics 2019, 107, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tao, L.; Zhao, X.; Kong, H.; Guo, F.; Bian, J. , An analytical model for face stability of shield tunnel in dry cohesionless soils with different buried depth. Computers and Geotechnics 2022, 142, 104565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Tong, J.; Liu, D. , A limit equilibrium model for the reinforced face stability analysis of a shallow tunnel in cohesive-frictional soils. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 2020, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, L. J. T.; International, T., INSTABILITY AT THE FACE: ITS REPERCUSSIONS FOR TUNNELLING TECHNOLOGY. 1989, 21. http://worldcat.org/issn/0041414X.

- Mollon, G.; Dias, D.; Soubra, A.-H. , Rotational failure mechanisms for the face stability analysis of tunnels driven by a pressurized shield. International Journal for Numerical and Analytical Methods in Geomechanics 2011, 35(12), 1363–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senent, S.; Mollon, G.; Jimenez, R. , Tunnel face stability in heavily fractured rock masses that follow the Hoek–Brown failure criterion. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences 2013, 60, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.; Soubra, A.-H.; Mollon, G.; Raphael, W.; Dias, D.; Reda, A. , Three-dimensional face stability analysis of pressurized tunnels driven in a multilayered purely frictional medium. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 2015, 49, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Han, K.; Zhang, D. , Face stability analysis of shallow circular tunnels in cohesive–frictional soils. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 2015, 50, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-h.; Zou, J.-f.; Chen, J.-q. , Shallow tunnel face stability considering pore water pressure in non-homogeneous and anisotropic soils. Computers and Geotechnics 2019, 116, 103205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Chen, G.; Qian, Z. , Tunnel face stability in cohesion-frictional soils considering the soil arching effect by improved failure models. Computers and Geotechnics 2019, 106, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancsecz, S.; Steiner, W. , Face support for a large Mix-Shield in heterogeneous ground conditions. In Conference Proceeding of Institute of Mining and Metallurgy and British Tunneling Society, Springer US: Lodon, 1994; pp 531-550. [CrossRef]

- Horn, N. Horizontal earth pressure on the vertical surfaces of the tunnel tubes. National Conference of the Hungarian Civil Engineering Industry, Budapest; 1961, November. 7–16. (In German). [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. P.; Tang, L. J.; Yin, X. S.; Chen, Y. M.; Bian, X. C. , An improved 3D wedge-prism model for the face stability analysis of the shield tunnel in cohesionless soils. Acta Geotechnica 2015, 10(5), 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazzellis, P.; Anagnostou, G. , Analysis Method and Design Charts for Bolt Reinforcement of the Tunnel Face in Purely Cohesive Soils. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering 2017, 143(9), 04017046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tan, J.; Shi, J.; Huang, X.; Chen, W. , A Method for calculating jacking force of parallel pipes considering Soil Arching Effect and Pipe-Slurry-Soil Interaction. Computers and Geotechnics 2024, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, K. M.; Finno, R. J.; Rossow, E. C., Analysis of Effects of Deep Braced Excavations on Adjacent Buried Utilities. 2003. https://trid.trb.org/view/696546.

- Lee, K. M.; Rowe, R. K. , Finite element modelling of the three-dimensional ground deformations due to tunnelling in soft cohesive soils: Part I — Method of analysis. Computers and Geotechnics 1990, 10(2), 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, G.; Watson, J. O.; Swoboda, G. , Three-dimensional analysis of tunnels using infinite boundary elements. Computers and Geotechnics 1987, 3(1), 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, A. , Experimental investigation of the face stability of shallow tunnels in sand. Acta Geotechnica 2010, 5(1), 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair R J, T. R. N. In Bored tunnelling in the urban environment, Fourteenth International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Rotterdam, Rotterdam, 1997. http://publications.eng.cam.ac.uk/330565.

- Liu Quan-wei, Y. Z.-n. , Model test research on excavation face stability of slurry balanced shield in permeable sand layers. Chinese Rock and Soil Mechanics 2014, 35(8), 2255–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baosheng, C. R. Q. L. T. L. Z. , Study of Limit Supporting Force of Excavtion Face’s Passive Failure of Shield Tunnels in Sand Strata. Chinese Journal of Rock Mechanics and Engineering 2013, 32, 2877–2882. [Google Scholar]

- Wei Gang, H. F. , Calculation of Minimal Support Pressure Acting on Shield Faceduring Pipe Jacking in Sand Soil. Chinese Journal of Underground Space and Engineering 2007, 3(5), 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziguang, Z.; Ruijin, M.; Jiesheng, Z.; Xuefeng, W.; Mengqing, Z.; Han, J. , Study on the Division of the Affected Zone under Construction Unloading and Its Construction Sequence of the Multiline Parallel River-Crossing Pipe Jacking. Advances in Civil Engineering 2023, 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material type | Elastic Modulus E/(MPa) |

Poisson’s ratio |

Volumetric weight γ/(kN/m3) |

Thickness /(m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reinforced concrete | 28000 | 0.2 | 23 | 0.3 |

| Digging machine housings | 206000 | 0.3 | 78.5 | 0.06 |

| Parameter type | Elastic Modulus E/(MPa) |

Poisson’s ratio |

Cohesive force c/(kPa) |

Angle of internal friction φ/(°) |

Volumetric weight γ/(kN/m3) |

Thickness /(m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filling soil | 8.0 | 0.27 | 10 | 10.0 | 18.00 | 0.5~1.5 |

| Silty chalky clay | 3.2 | 0.27 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 17.52 | 1.2~2.7 |

| Clay | 12.0 | 0.25 | 70 | 16.9 | 19.22 | 5.9~7.5 |

| Silty clay | 11.3 | 0.25 | 40 | 15.5 | 19.22 | 4.8~6.0 |

| Strongly weathered mudstone | 25.0 | 0.35 | 90 | 30 | 22.00 | 1.7~2.6 |

| Case | Ⅰ | Ⅱ | Ⅲ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness of overburden (m) | 3.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| Theoretical value of support pressure (kPa) | 88.5 | 74.3 | 60.0 |

| Support ratio λ | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.5 | |

| Support pressure/kPa | 44.25 | 53.10 | 61.85 | 70.80 | 79.65 | 88.50 | 132.75 | 177.00 | 221.25 | 265.50 | 309.75 | |

| 37.15 | 44.58 | 52.01 | 59.44 | 66.87 | 74.30 | 111.45 | 148.6 | 185.75 | 222.9 | 260.05 | ||

| 30 | 36 | 42 | 48 | 54 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 | 180 | 210 | ||

| Jacking distances(m) | upper limit value Pmax(kN) | lower limit value Pmin(kN) | optimal value Po(kN) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-10 | 4868.249 | 2230.598 | 3098.977 |

| 11 | 4777.464 | 2158.328 | 3012.564 |

| 12 | 4686.679 | 2086.059 | 2926.288 |

| 13 | 4596.038 | 2013.904 | 2839.876 |

| 14 | 4505.253 | 1941.634 | 2753.463 |

| 15 | 4394.509 | 1849.406 | 2672.566 |

| 16 | 4222.220 | 1695.603 | 2608.338 |

| 17 | 4049.658 | 1541.555 | 2544.110 |

| 18 | 3877.368 | 1387.752 | 2479.984 |

| 19 | 3704.806 | 1233.705 | 2415.755 |

| 20 | 3532.243 | 1079.658 | 2351.527 |

| 21 | 3359.954 | 925.855 | 1133.573 |

| 22 | 3187.391 | 771.807 | 1111.388 |

| 23 | 3014.829 | 617.760 | 1089.204 |

| 24 | 2842.540 | 463.957 | 1067.055 |

| 25-50 | 2669.977 | 309.910 | 1044.870 |

| Jacking distances(m) | measured value P’(kN) | Jacking distances(m) | measured value P’(kN) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2639 | 41 | 1926 |

| 4 | 3278 | 43 | 1819 |

| 6 | 2917 | 45 | 2712 |

| 8 | 2556 | 47 | 2605 |

| 10 | 2195 | 49 | 2498 |

| 12 | 1834 | 51 | 2391 |

| 14 | 2509 | 53 | 2284 |

| 16 | 2242 | 55 | 2137 |

| 18 | 2036 | 57 | 2930 |

| 20 | 1889 | 59 | 2264 |

| 22 | 1782 | 61 | 2338 |

| 24 | 2675 | 63 | 2977 |

| 26 | 2568 | 65 | 2616 |

| 28 | 2461 | 67 | 2255 |

| 30 | 2354 | 69 | 2894 |

| 32 | 2247 | 71 | 3533 |

| 35 | 2140 | 73 | 3172 |

| 38 | 2033 | 75 | 2811 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).