1. Introduction

Depending on the field concerned (pedology, engineering, mining), there are several definitions of laterites. For engineers, they are materials with a porous structure often consisting of nodules with a scoriaceous appearance, of different hardness and thickness, while chemists consider them as Fe

2O

3(FeO)-Al

2O

3-SiO

2-H

2O matrices based on kaolinites in which a high proportion of Al

3+ is replaced by Fe

2+ or Fe

3+ [

1,

2]. [

3] proposed a definition based on field observations; they latter describe lateritic soils as strongly weathered tropical or subtropical residual soils, well graded and generally covered with sesquioxide-rich concretions. Cameroon has been experiencing a situation of urban crisis for many years, marked by strong demographic growth, which creates a high demand for housing and infrastructure [

4]. Lack of decent housing is felt everywhere you are in the country. Urban planning experts had estimated this need at around one million housing units in 2010, in 2023 it is estimated at more than five million and will continue growing year after year according to the projections drawn up by the Central Bureau of Censuses and Population Studies (BUCREP) within the framework of the third general population and housing census. However, whether it is the construction projects of 10,000 housing units in the cities of Douala and Yaoundé, 100 housing units in the regional capitals or in all housing in Cameroon and even in Africa, the same observation is a fact: the vast majority of the materials building are imported. However, the exploitation of mineral resources and the development of local techniques will not only reduce these imports but also facilitate access to decent housing.

Geopolymerization technology has received considerable attention over the past few decades. It involves the chemical reaction between alumino-silicate material and an activator solution at ambient or slightly elevated temperature. Products obtained by geopolymerization are able to harden within a reasonable time [

5]. However, the brick stabilized by a hydraulic binder, in this case ordinary portland cement (OPC), remains the most widely used in Cameroon for the construction of modern buildings, despite the fact that the manufacture of OPC releases an important quantity of CO

2 which has an environmental impact since it contributes to global warming [

6,

7,

8] into the atmosphere. Indeed, the production of one tonne of OPC generates about 0.55 tonnes of CO

2 of chemical origin and 0.39 tonnes of fuel [

9,

10] during calcination. Moreover the transport of the material and other processes involved, make the manufacture of portland cement very energy-consumming [

11]. On the other hand, the plastic material is integrated today among the essential elements for human and his environment. Its multiplicity of uses makes it a tool whose very diversified properties have to be studied. Its shaping facility, resistance to shocks, temperature variations, humidity…etc makes it useful in many fields such as packaging, building, road, automotive, electricity…etc. However around 600,000 tons of plastic waste were identified in 2018 in Cameroon, according to the Cameroonian Ministry of Environment and Nature Protection; Worse still, according to the report of [

12], the production of plastic packaging should reach 318 million tonnes in the world by 2050, and if nothing is done there would be more plastic than fish in the oceans. Hence this work aims to propose a solution both with regard to the recycling of plastic waste in the PET category, as well as the stabilization of lateritic materials by geopolymerization using phosphoric acid as activator to produce CEBs, the concentration of 10M is retained based on previous work [

13].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling, Preparation of Materials and Characterization

Soil horizon is the basic sampling unit. In pedology as in geotechnics, one of the major problems lies in the representativity of the samples. The precautions to be paid when collecting samples in the field depend on the analysis considered [

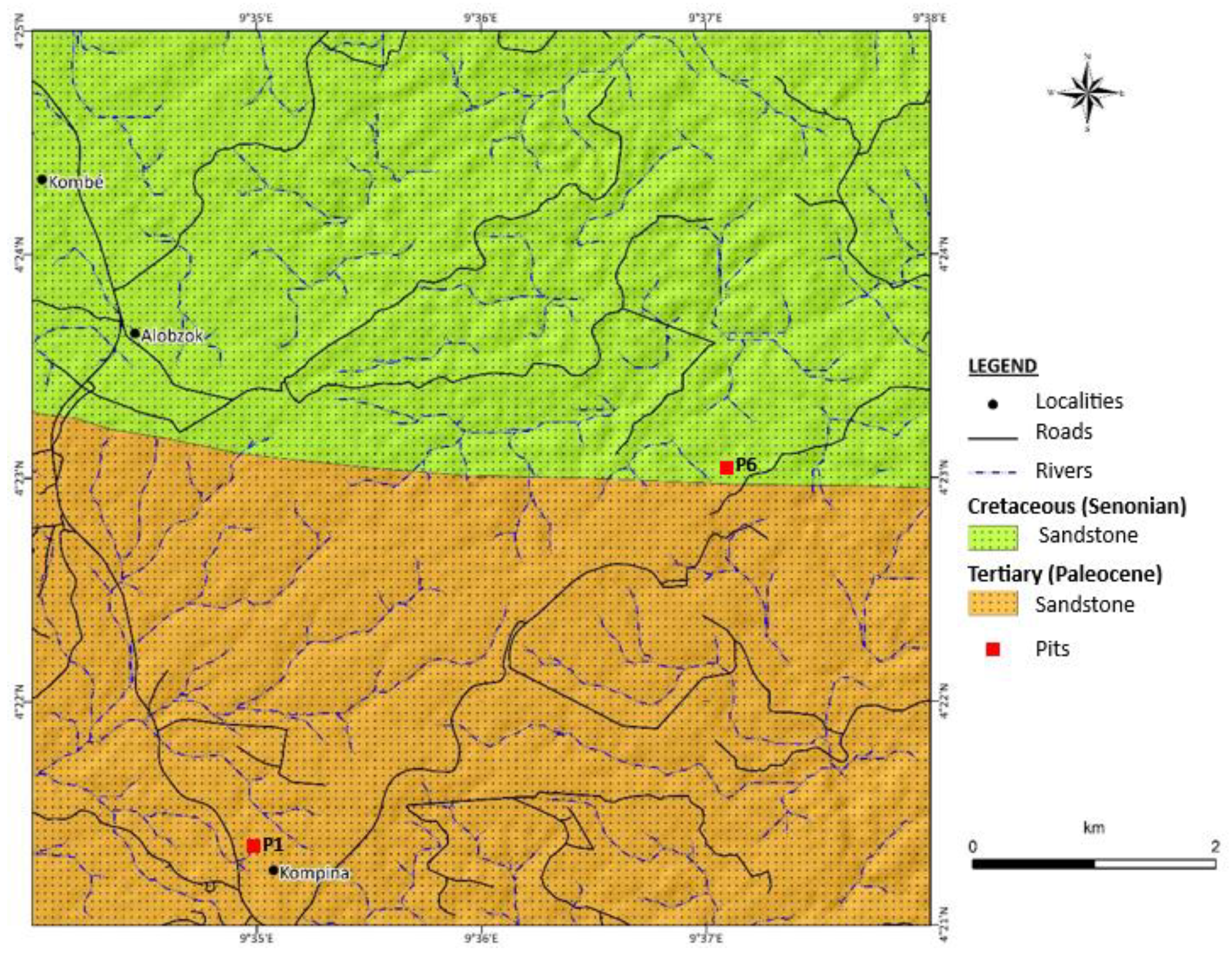

14]. The lateritic material (LAT) was collected in a study area of the locality of Kompina (Littoral-Cameroon) and its surroundings, between the parallels 4°21′ to 4°25′ North and the meridians 09°34′ to 09°38′ East (

Figure 1). This study will focus on two (02) lateritic soil samples, taken from the B horizon of two different pits and source rocks of different ages, namely LAT1 taken from sandstone of the Bongue series from the tertiary – Pleocene and LAT6 taken from a Cretaceous-Senonian sandstone [

15]. These samples of raw materials were identified by geotechnical tests in the regional delegation of littoral of the national laboratory for civil engineering of Cameroon (LABOGENIE) (

Table 1). The cleaned and crushed PET bottles were collected from the company “Namé recycling” based in Douala and the powder used in this work was obtained by an artisanal micronization process (

Figure 2), which consists of melting the bottles of PET, to grind and sieve.

The mineralogical composition of raw materials and different formulas was determined with a Picker powder X-ray diffractometer with a graphite crystal, equiped with an automated sample changer, using CuKα radiation with a scan speed of 3-65° 2θ angles at 2°/min. The patterns are recorded on magnetic tape as a series of 3100 consecutive data points where each data point is the integrated intensity over a 0.02° 2θ interval.

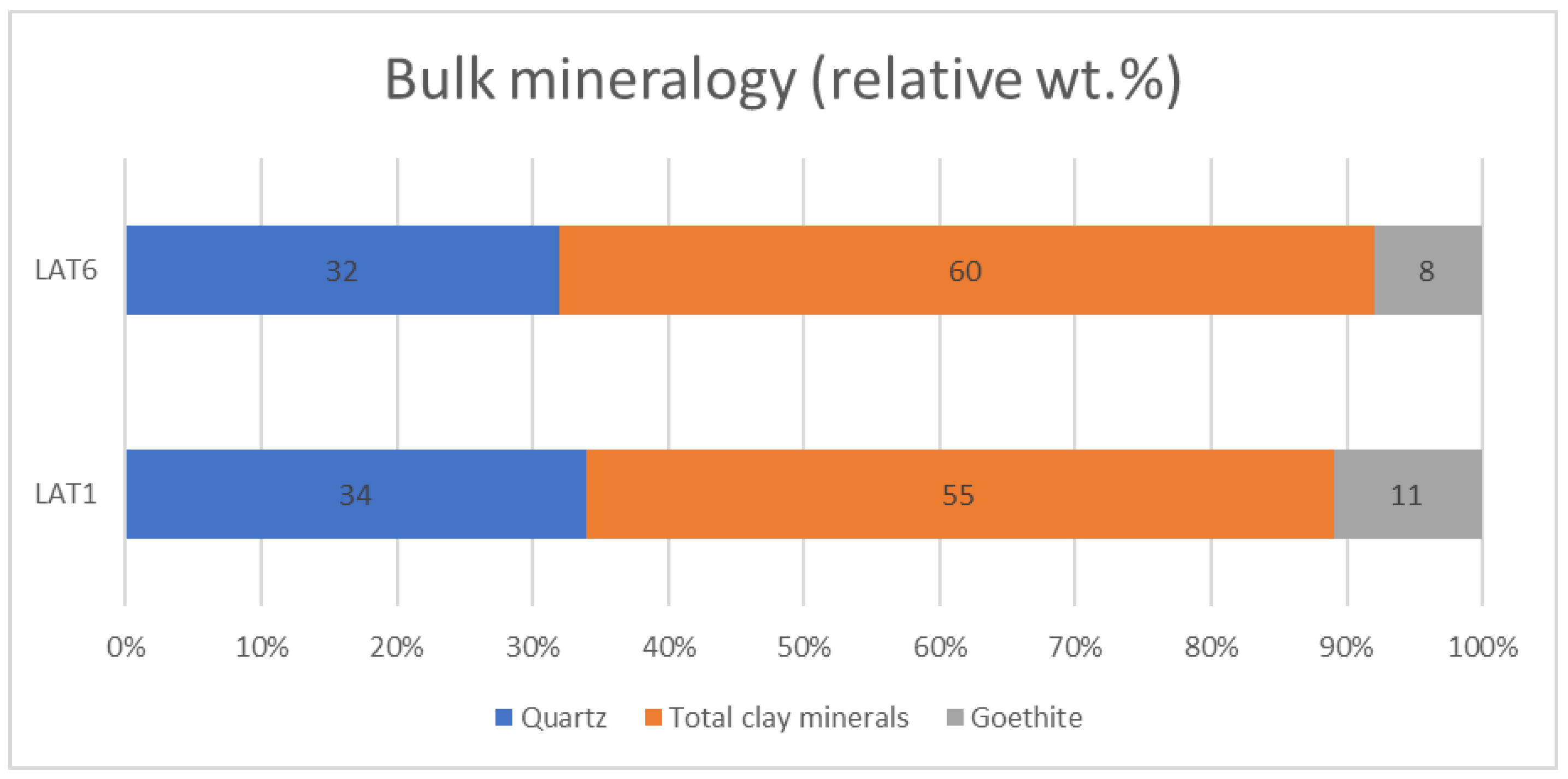

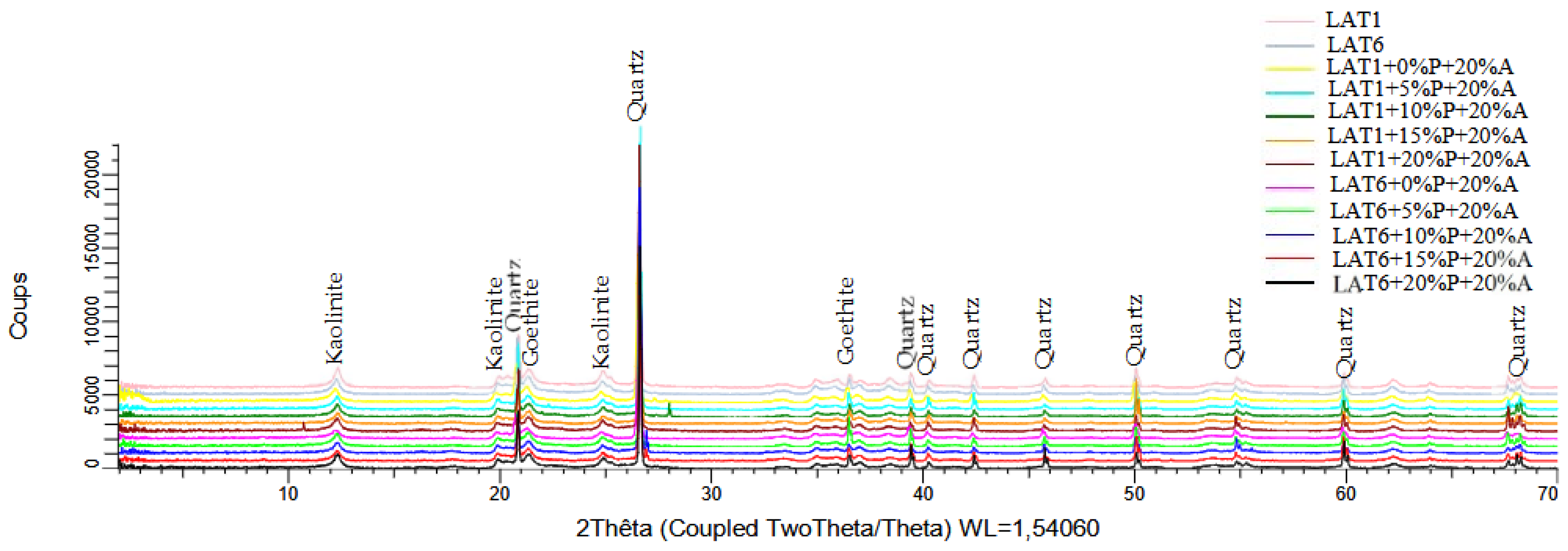

Figure 3 presents the mineralogical composition and proportion of raw materials.

Lateritic soil (after drying in an oven at 105°C for 24 hours) and the PET powder were sieved respectively using 5 mm and 315 μm sieves. For the geopolymerization process, H

3PO

4 at 10M was used [

4].

2.2. Stabilization of Lateritic Materials Associated with PET Powder

The bricks were obtained by geopolymerization of the mixture of a lateritic material (LAT) and polyethylene terephthalate powder (P) associated with a solution of phosphoric acid (A). The phosphoric acid/laterite (A/LAT) mass ratio used in this work is 0.2. And for this ratio (A/LAT), correspond the following PET powder/phosphoric acid (P/A) mass ratios: 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1. In order to obtain a consistency allowing optimal compaction of bricks and close to the consistency of the optimum proctor of the raw materials studied, a quantity of water is added according to the dosage of the A+P+LAT mixture. The phosphoric acid-based geopolymer is composed of amorphous matrix and crystalline compounds. The amorphous substances are composed of Si–O–P, Al–O–P [

16], –Si–O–Si–O–, Si–O–Al–O–P [

17], Si–O–P–O–Al [

18], and other structural units. The proportions of the mixtures are presented in

Table 2.

Formulation of bricks consists of four (04) steps (

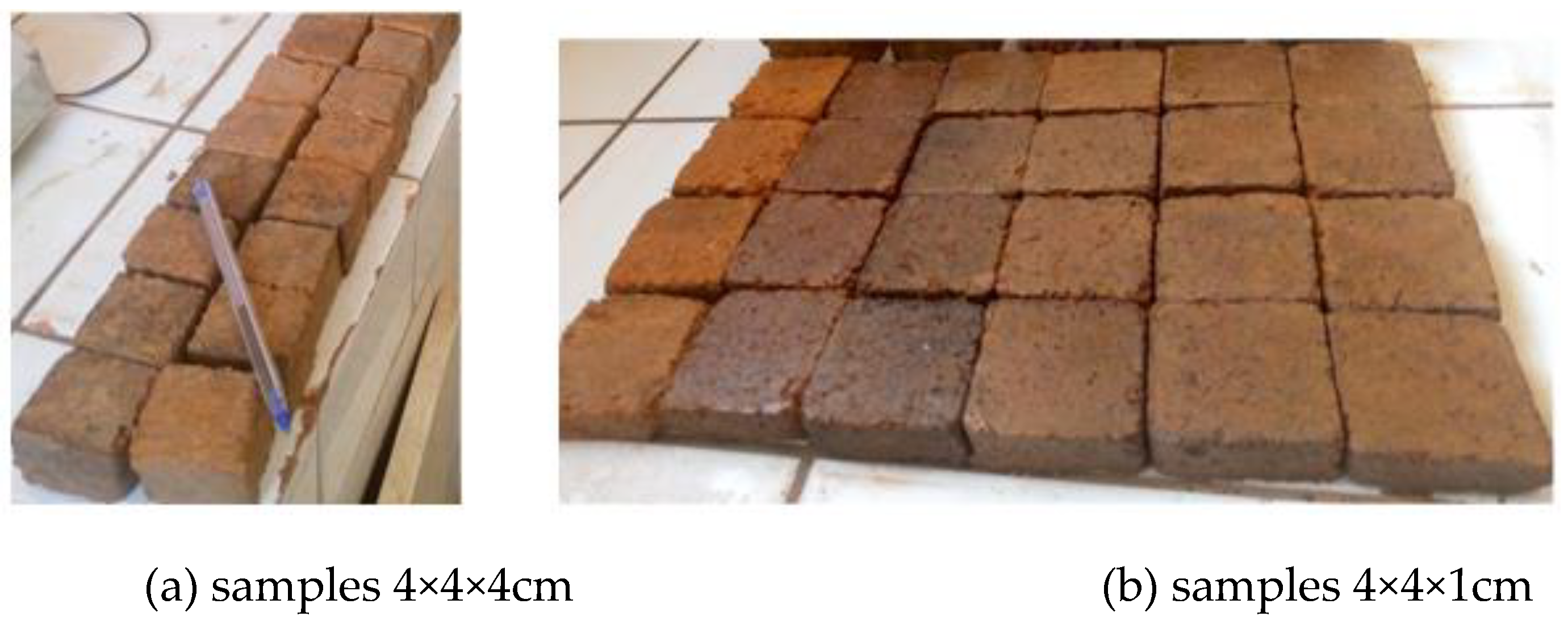

Figure 4) namely: 1- Manual mixing of laterite and PET powder; 2- Adding phosphoric acid to the mixture, manual mixing for about 5 minutes; 3- Adding a certain amount of water, manual mixing for about 5 minutes; 4- Static compaction in a cubic mold (4 × 4 × 4 cm

3) for physico-mechanical tests, and prismatic mold (4 × 4 × 1 cm

3) for thermal tests, at a pressure of 8 MPa on a LABOTEST France brand hydraulic press with a capacity of 60 KN. After demoulding, the bricks are kept at room temperature (25° C) in a polyane film for 7 days. After these first 7 days of cure, the samples are then placed in the open air and still at 25°C in the laboratory.

2.3. Characterization of the CEBs

The physico-mechanical and thermal analyzes carried out are those on the bricks of 7 and 28 days of age. Compressive strength was performed on both dry and wet CEBs. The physical properties, namely the bulk density and the water absorption, were determined on bricks of dimensions 4×4 × 4 cm

3. Wet strength was determined on samples immerged in water at 25 ± 3°C for 24h. Concerning water absorption, the samples after being dried at room temperature, and after stabilization of their dry weight, were immersed in water at a temperature of 25 ± 3 ° C for 24h. After removing the samples from the water, they are wiped with a clean cloth and subsequently weighed, their wet mass is compared to their dry mass to determine the amount of water absorbed according to [

19]. The bulk density of the bricks was determined by the graduated cylinder method according to [

20], which consisted in weighing the paraffined samples then immersed in a cylinder containing an initial volume of water, after immersion of the sample, the final water volume is reported and bulk density is determined by the ratio of the mass of the paraffin-free sample to the volume of water displaced. As far as the thermal characteristics are concerned, based on [

21]. They are determined by the hot plane method, which consists of placing a heat source in the form of a thin heating mat, between two (02) samples of the same composition. The evolution of the temperature in the center of the plane is measured using a thermocouple. Thermal conductivity λ (W.m

-1.K

-1) and thermal effusivity E (J.K

-1.m

-2.s

-1/2) are the thermal properties tested in this constant pressure study, of 4×4×1cm

3 specimens. A HUATO S220-T8 Thermal Properties Analyzer was used to establish these parameters. Once the HUATO S220-T8 is on, the hot surface is correctly inserted between two test specimens of the same composition and the assembly is stabilized using a stabilization device. After 180 seconds, the results are displayed automaticaly on the screen. The test device is illustrated in

Figure 5.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Characterization of Materials

The 2 samples of lateritic raw materials taken from the locality of Kompina and surroundings were the subject of characterization by geotechnical tests, the results were recorded in

Table 1. It emerges from these results that the 2 samples are class A2 according to the GTR classification and they were both gravelly-silty laterite.

3.2. Physical Properties of CEBs

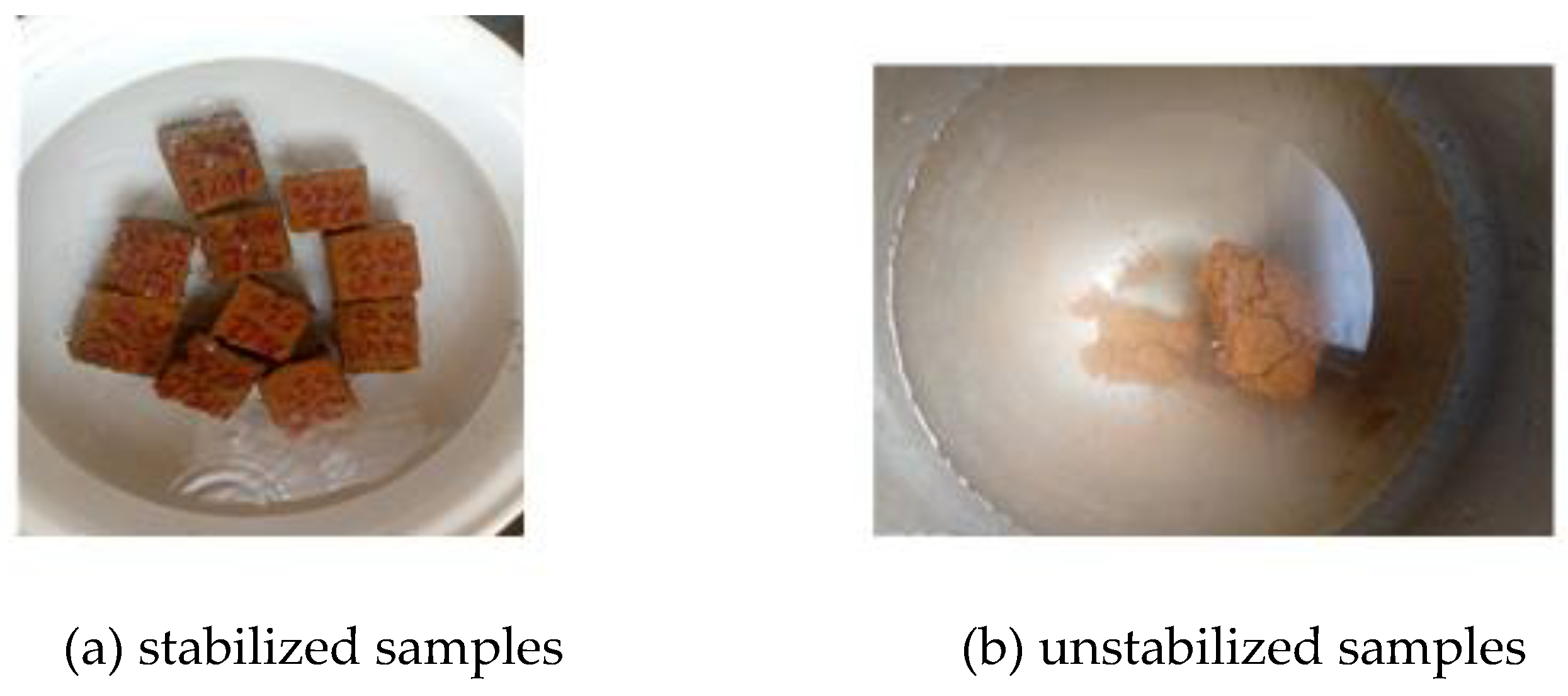

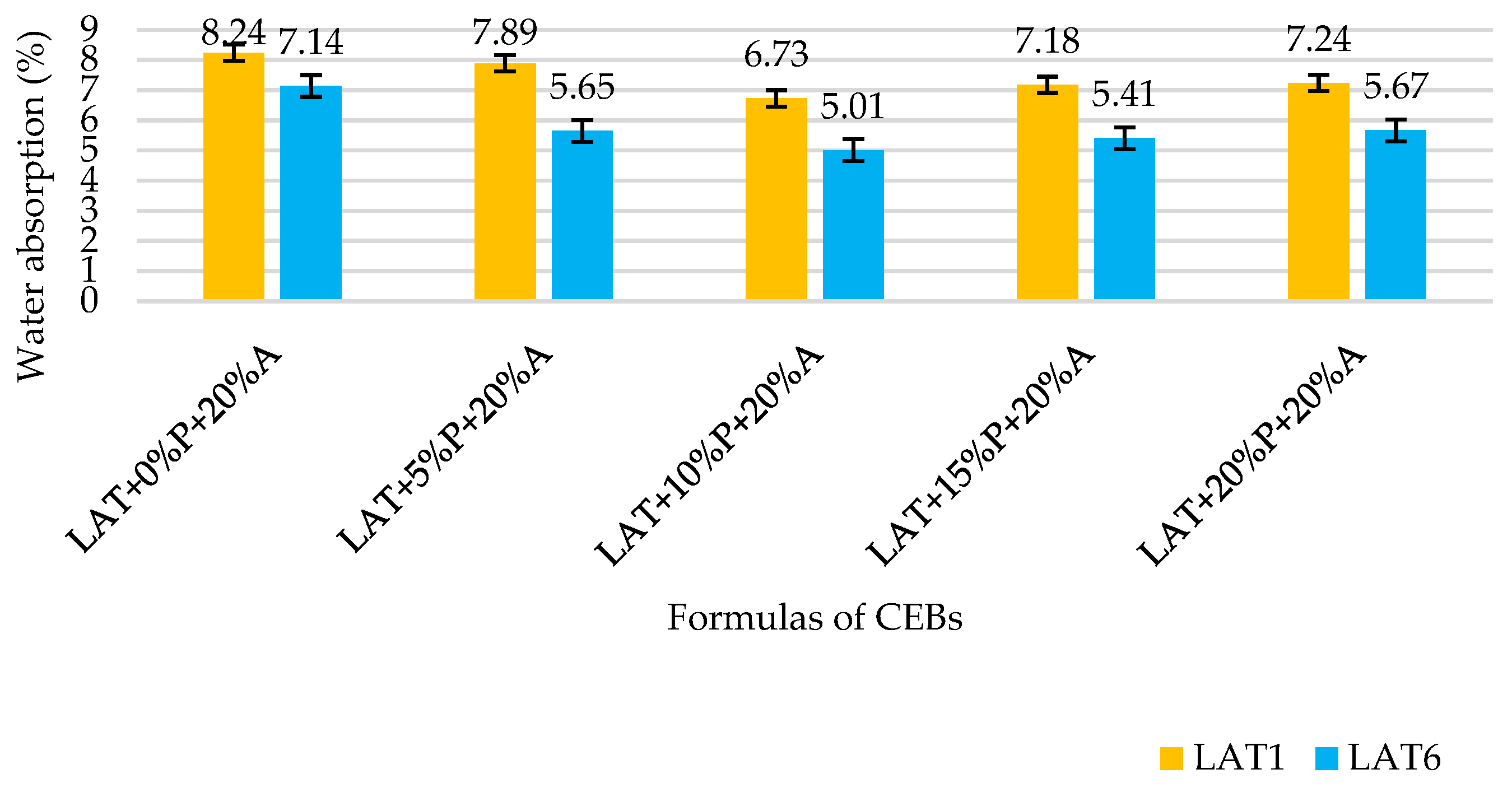

Figure 6 presentes the samples used to determine Bulk density, water absorption, compressive strength (a), and thermal conductivity and effusivity (b). The water absorption at 25°C (

Figure 7) of stabilized (

Figure 7a) and unstabilized (

Figure 7b) CEBs has been carried out. It emerges that, water absorption varies from 5.01% to 7.14% respectively for the formulas LAT+10%P+20%A and LAT+0%P+20%A (LAT6) and between 6.73% and 8.24% for LAT+10%P+20%A and LAT+0%P+20%A (LAT1) respectively (

Figure 8). After 24h in water, the unstabilized samples are completely dislocated. For stabilized samples, regardless of the source of raw material (LAT1 or LAT6), CEBs are very sensitive to the amount of PET powder in the mix.

The rate of water absorption therefore thus decreases with the incorporation of the PET powder for the same quantity of activating solution, with the lowest value at 10% of PET. These values provide enough information on the ability of PET powder to waterproof stabilized CEBs. The presence of fine particles of this powder, associated with the action of the H

3PO

4 solution, significantly reduces the pores in the geopolymer matrix. These values of the absorption rate of laterite CEBs associated with the PET powder, and stabilized with the H

3PO

4 solution do not exceed 14%, and therefore meet the requirements of the standards for construction materials [

22].

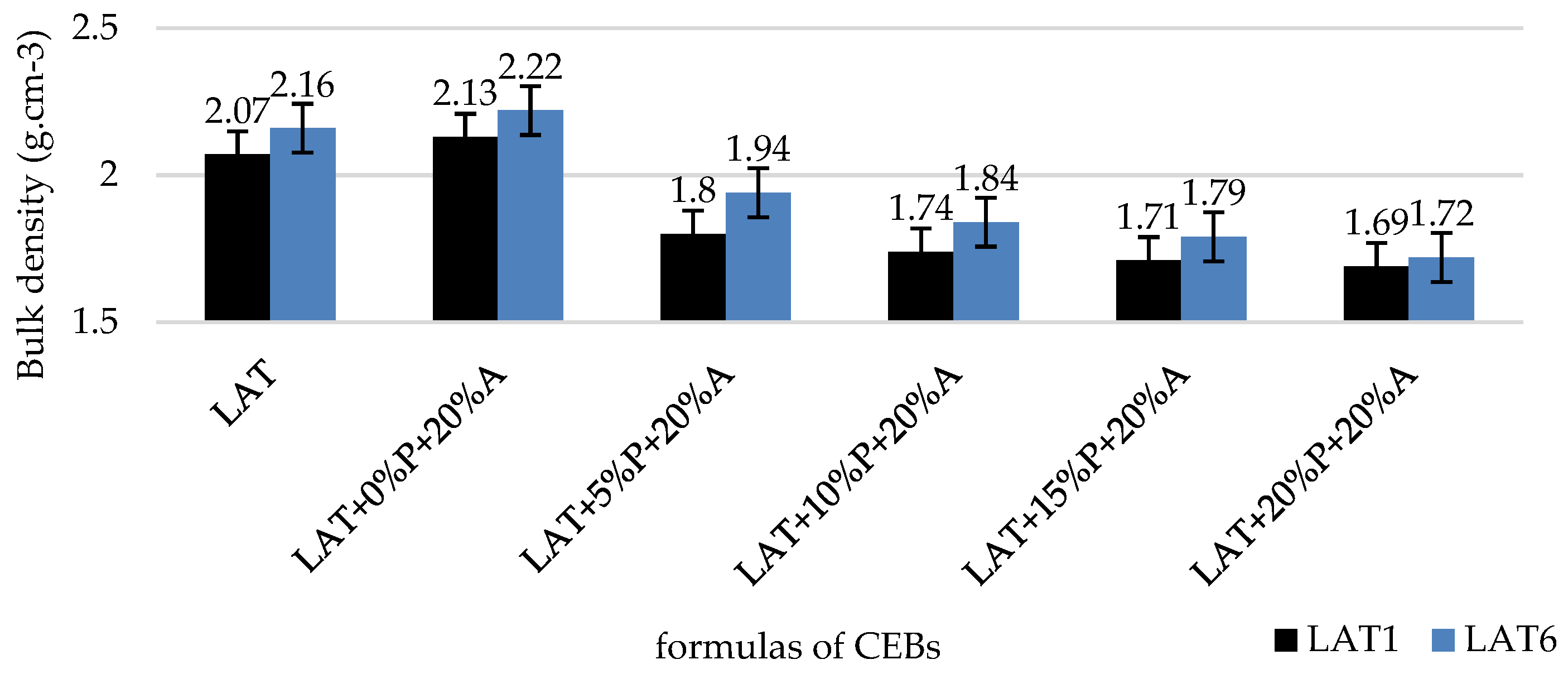

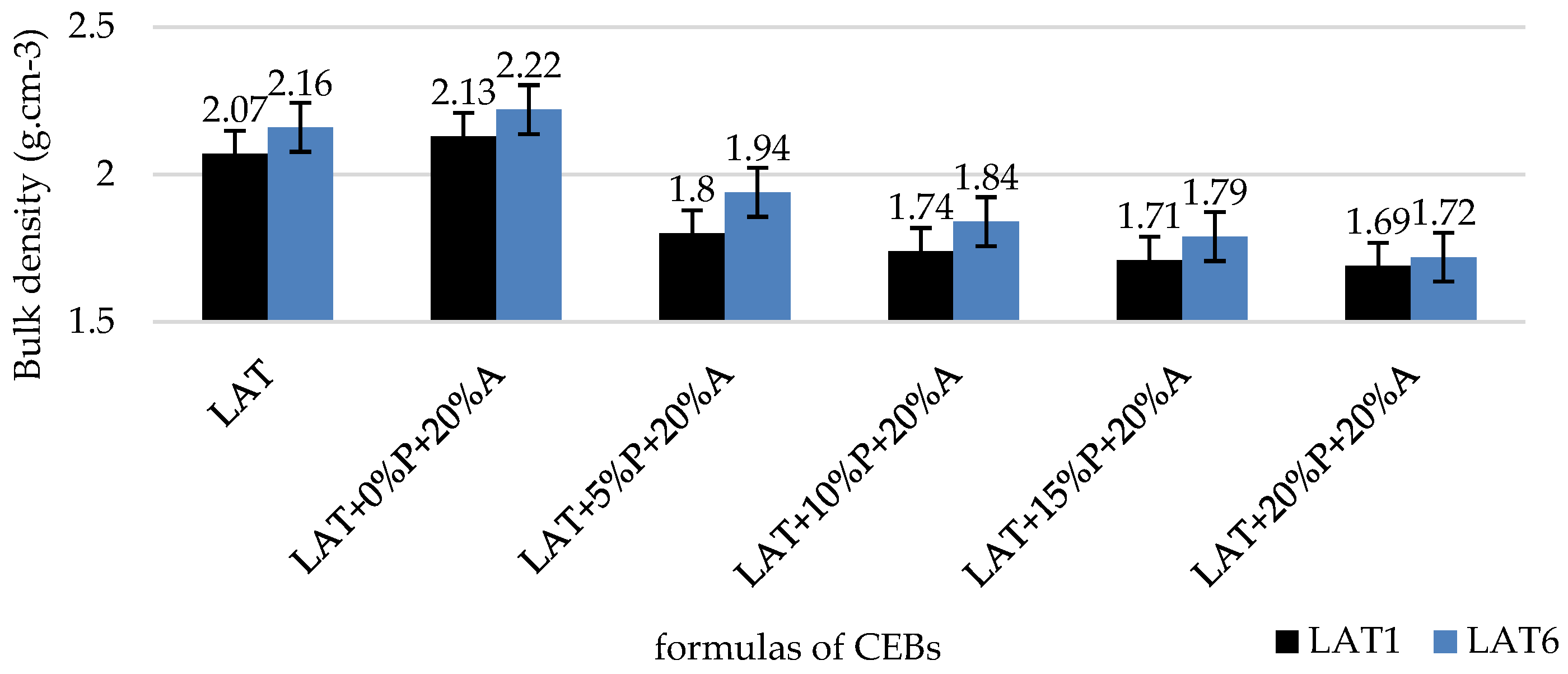

Bulk density values of CEBs stabilized at room temperature (25°C) are shown in

Figure 9. These values vary from 1.69 g.cm

-3 (LAT+20%P+20%A) to 2.13 g.cm

-3 (LAT+0%P+20%A) for LAT1 and from 1.72 g.cm

-3 (LAT +20%P+20%A) at 2.22 g.cm

-3 (LAT+0%P+20%A) for LAT6. The general observation which is made is that, the bulk density increases with the addition of the activating solution, on the other hand it decreases with the increase in PET powder in the mixture; this is due to the fact that the phosphoric acid by its active principle, will decrease the space between the grains, however the PET powder with a lower density than that of the lateritic material decreases the density of the mixture.

3.3. Wet and Dry Compressive Strengths

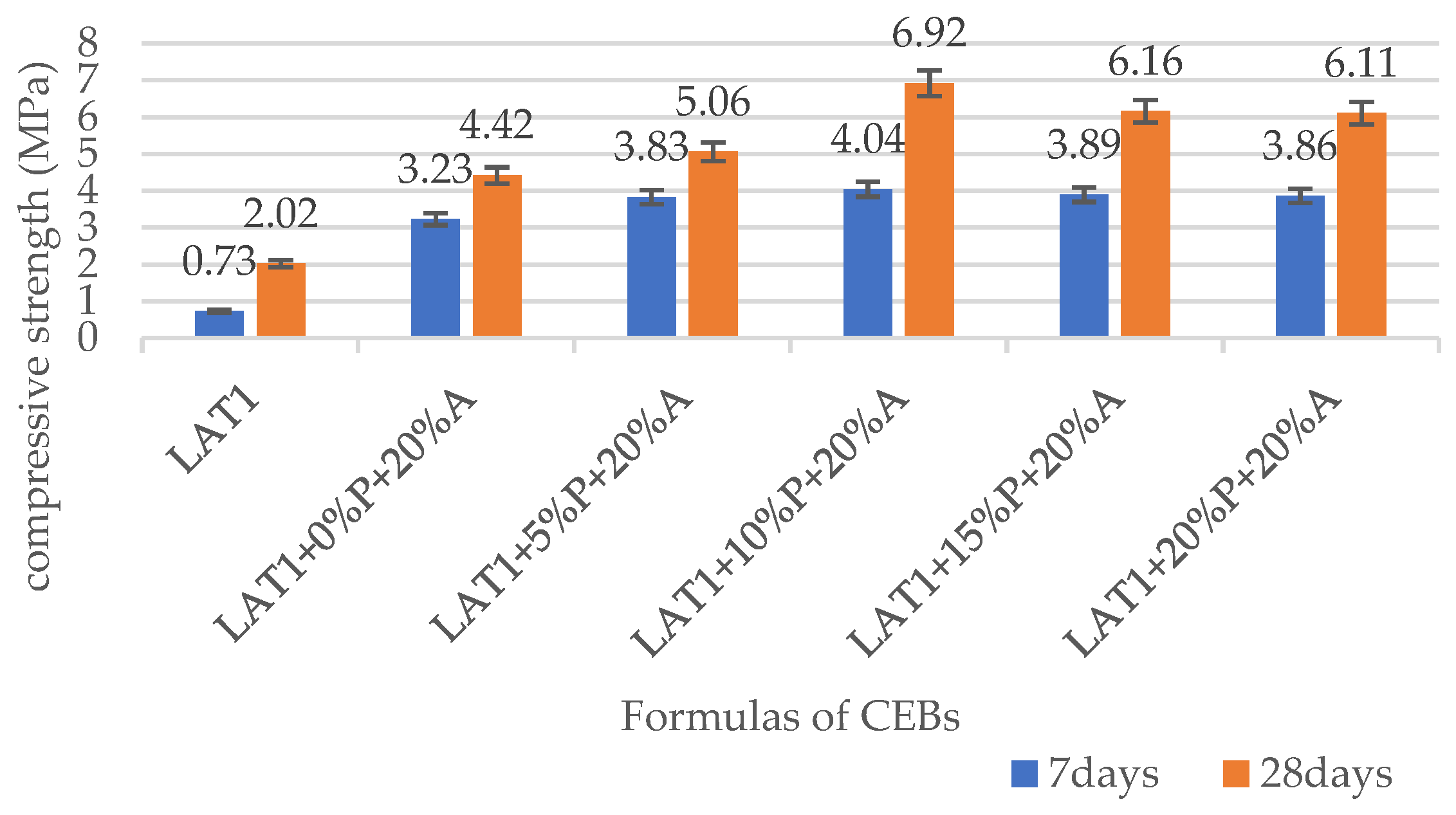

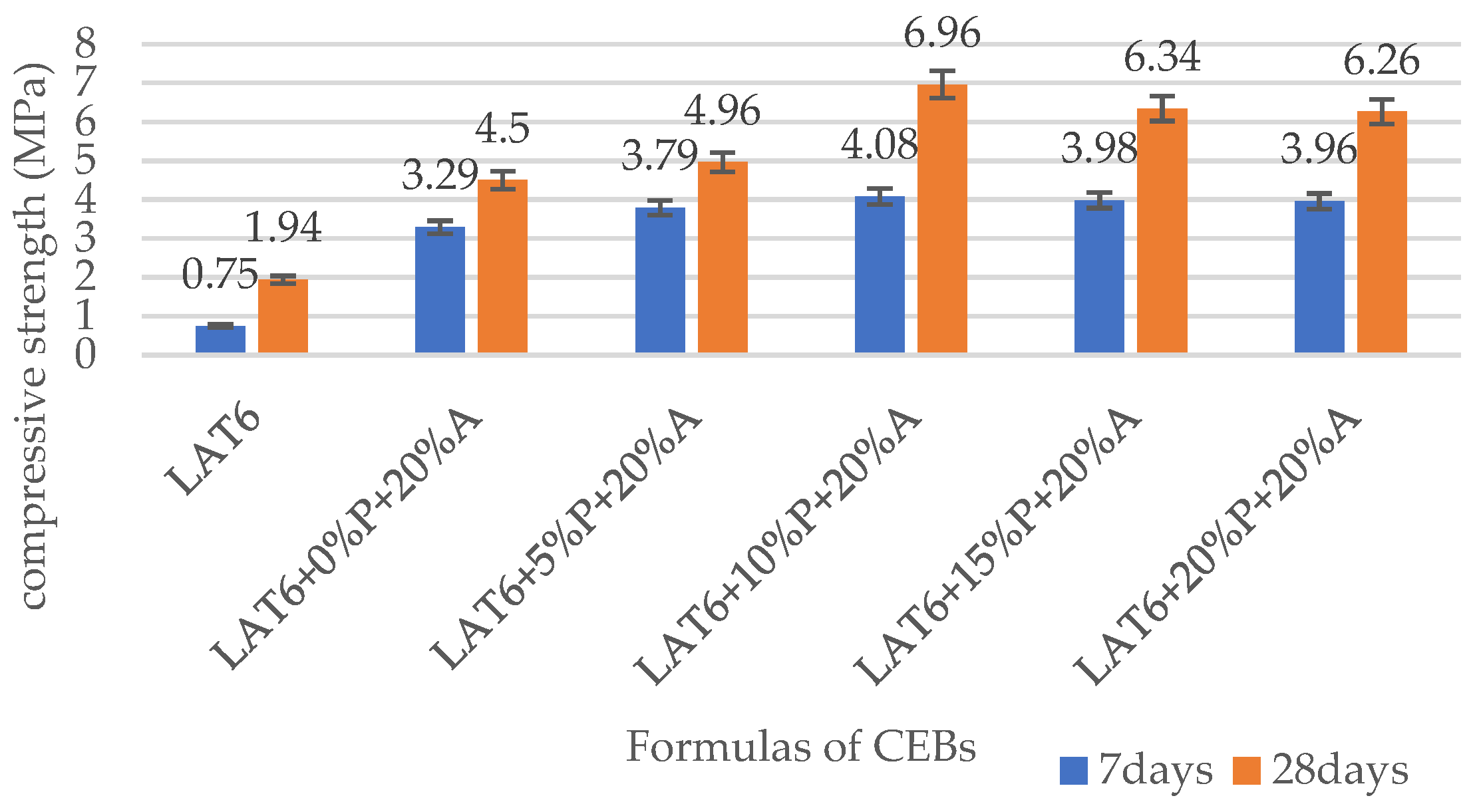

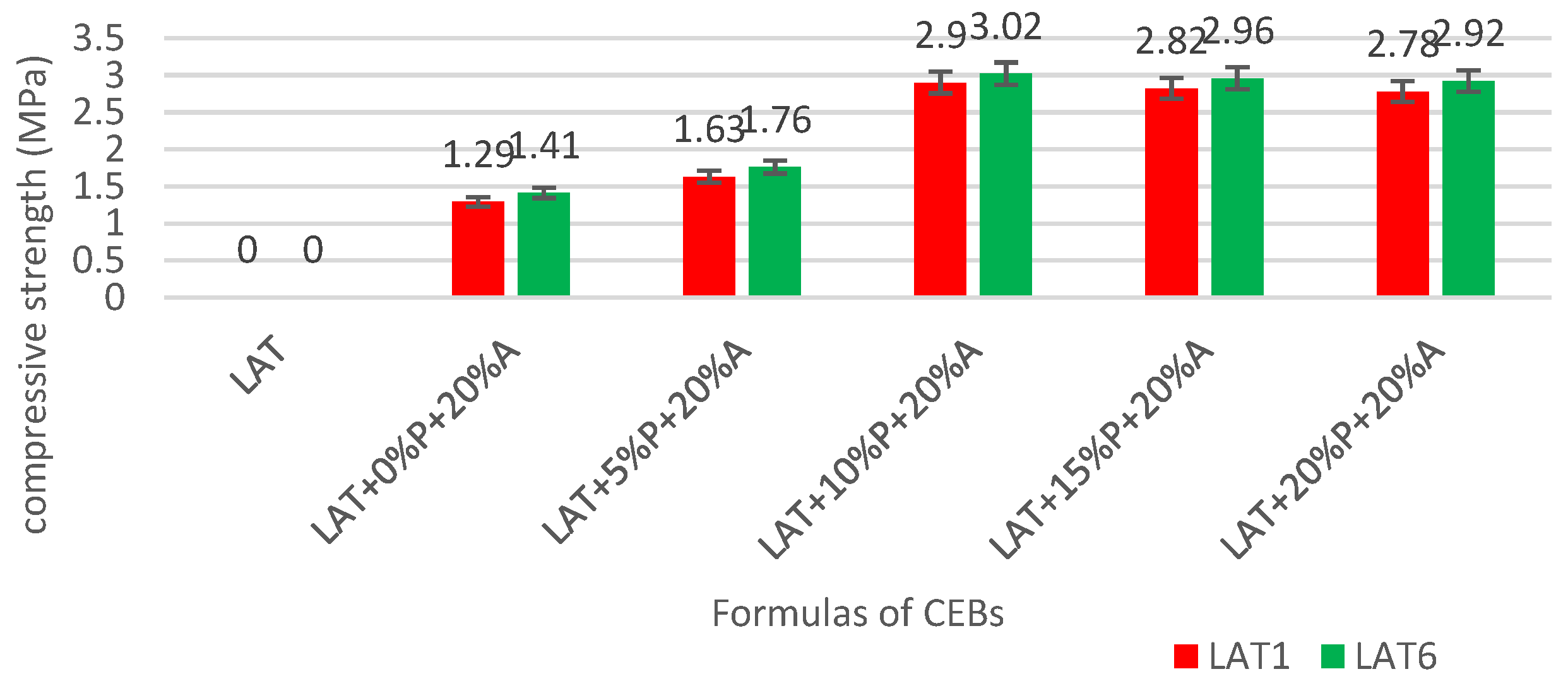

Figure 10 a and b show the dry compressive strengths (CS) of raw and stabilized CEB samples of LAT1 and LAT6 respectively at room temperature 25°C. It appears that the compressive strength increases with the addition of the activating solution; at 28 days age CS varies from 2.02 and 1.94 MPa for the raw materials CEBs of formula LAT1 and LAT6 respectively, to 4.42 and 4.5 MPa for the CEBs LAT1+0%P+20%A and LAT6+0%P+20%A respectively. More interestingly, it increases with the addition of PET powder, 4.42 MPa and 4.5 MPa for CEBs LAT1+0%P+20%A and LAT6+ 0%P+20%A to 6.92 and 6.96 MPa for CEBs LAT1+10%P+20%A and LAT6+10%P+20%A respectively, and decreases beyond 10% of powder. Indeed, these CS values of stabilized CEBs are influenced by the strong cohesion generated by the activating solution in the lateritic material as well as the waterproofing of the mixture generated by the presence of fine PET particles. This cohesion thus makes it possible to obtain very compact bricks with interesting mechanical properties. The CS values of the stabilized CEBs without PET powder (4.42 MPa and 4.5 MPa for CEBs LAT1+0%P+20%A and LAT6+0%P+20%A) make it possible to understand that the lateritic material stabilizes in an acidic environment. This phenomenon that is also observed in the work of [

23,

24,

25], and is due to the formation of Poly(phospho-ferro-siloxo) networks resulting from the reaction between phosphoric acid, amorphous phases of aluminosilicates and iron oxides.

The wet CS (

Figure 11) of 28 days CEBs evolves in a concordant manner with that of dry CS. It increases with the increase in the content of phosphoric acid and of the PET powder up to LAT+10%P+20%A formula, and decreases beyond 10% of PET. However, different formulations of wet samples show a drop in strength of approximately 54.7% and 52.1% compared to the dry strength respectively for LAT 1 and LAT 6. This drop in strength was also observed by [

26,

27] who studied the effect of water on the physico-mechanical characteristics of phosphate geopolymer materials. In these works, of which geopolymerization precursors were meta-kaolin and calcined laterite, the maximum value of the drop in strength in wet conditions was 60% compared to the dry strength for all the samples.

From the results obtained in this work, it appears that the CEBs made from the LAT+10%P+20%A formula have the best results in water absorption and compressive strength. Indeed, these results show that the addition of PET powder up to 10% in a LAT+20%A mixture, in a phosphated acid medium considerably reduces the voids in the stabilized material, which is materialized by a decrease in water absorption. And this new organization in the internal structure of the material has as corollary, the increase in the compressive strength. As asserted by [

28], the evolution of the compressive strength essentially depends on the improvement of the geopolymer network.

3.4. Microstructural Properties

Figure 12 presentes the x-ray powder diffraction patterns collected for geopolymers materials associated with PET powder and synthesized in acidic medium, and for raw materials. The patterns of stabilized materials show the presence of the previously identified crystallized minerals of lateritic soil [

13]; no newly formed crystalline phases has been detected in the different formulas, only goethite (Fe[O(OH)]), quartz (SiO

2) and kaolinite (Al

2Si

2O

5(OH)

4). Hence, the binder is of amorphous character that is typical of geopolymers [

29].

3.5. Thermal Propperties

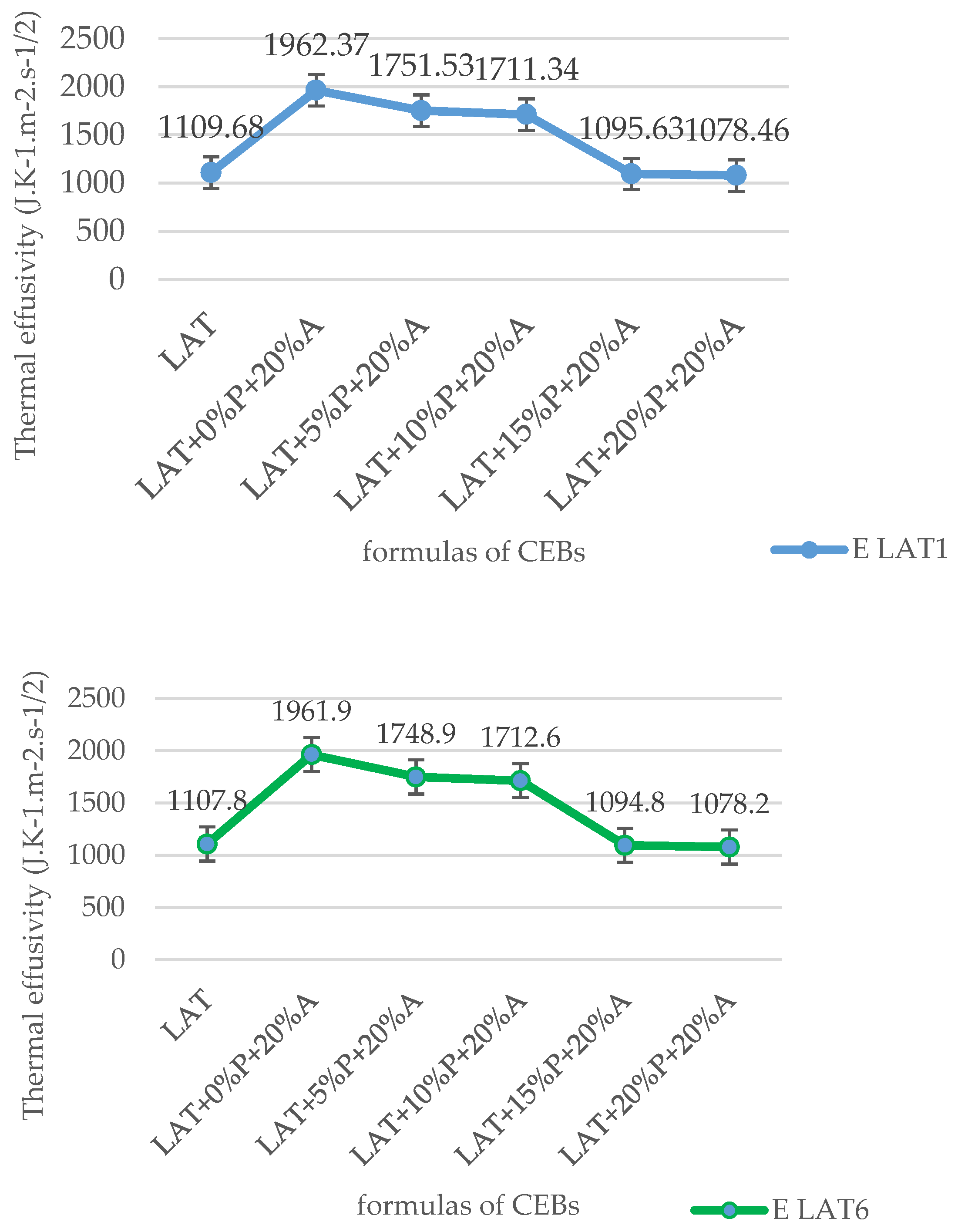

From the above and for the 2 laterite raw materials tested, it emerges that the CEBs obtained by combining LAT+20%A present good results in compression and water absorption. It was therefore a matter of using this formula to verify the impact of the addition of 0-20% of PET powder on the thermal properties of the CEBs.

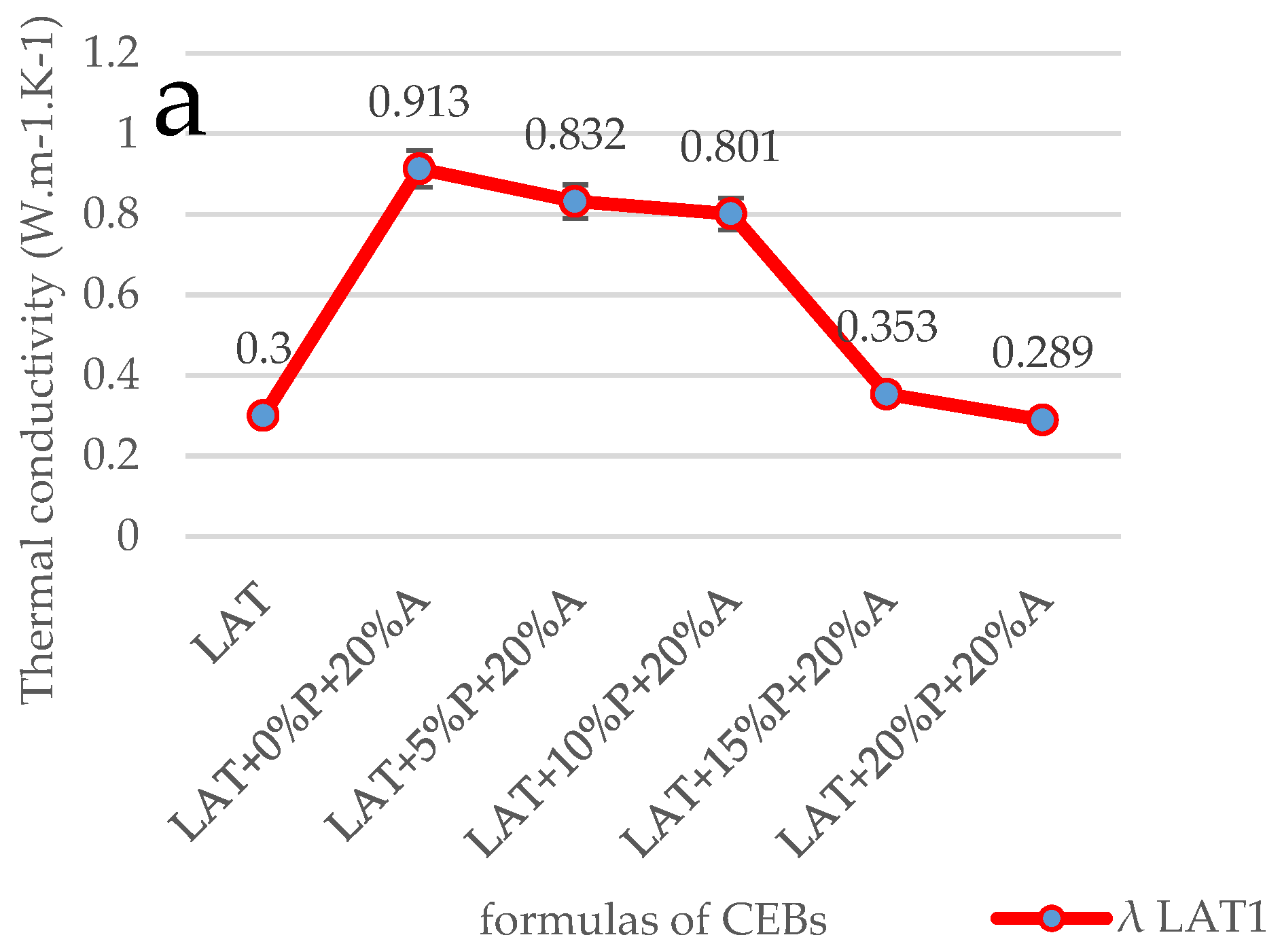

Figure 13a,b and

Figure 14a,b are the graphic representations of the thermal characteristics (conductivity and effusivity) of the different formulas (LAT, LAT+0%P+20%A, LAT+5%P+20%A, LAT+10%P+ 20%A, LAT+15%P+20%A and LAT+20%P+20%A) on LAT1 and LAT6. These results show that the highest thermal conductivity values are given by the formula LAT+0%P+20%A, 0.913 W.m

-1.K

-1 and 0.911 W.m

-1.K

-1 respectively for LAT1 and LAT6 while the lowest are observed in LAT+20%P+20%A, with 0.289 W.m

-1.K

-1 both for LAT1 and LAT6; also for thermal effusivity values, the highest are those of LAT+0%P+20%A, 1962.37 J.K

-1.m

-2.s

-1/2 and 1961.9 J.K

-1.m

-2.s

-1/2 respectively for LAT1 and LAT6 and the lowest belong to LAT+20%P+20%A, with 1078.46 J.K

-1.m

-2.s

-1/2 and 1078.2 J.K

-1.m

-2.s

-1/2 respectively to LAT1 and LAT6. It appears that, the thermal conductivity and effusivity increase with the introduction of phosphoric acid, from 0.289 W.m

-1.K

-1 to 0.913 W.m

-1.K

-1 and 0.911 W.m

-1.K

-1 and from 1106.68 J.K

-1.m

-2.s

-1/2 and 1107.8 J.K

-1.m

-2.s

-1/2 to 1962.37 J.K

-1.m

-2.s

-1/2 and 1961.9 J.K

-1.m

-2.s

-1/2 from the formula LAT to LAT+0%P+20%A respectively for LAT1 et LAT6. But conversely, these thermal characteristics dicrease with the increasing PET powder from 0.913 W.m

-1.K

-1 to 0.289 W.m

-1.K

-1 and from 0.911 W.m

-1.K

-1 to 0.289 W.m

-1.K

-1, from 1962.37 J.K

-1.m

-2.s

-1/2 to 1078.46 J.K

-1.m

-2.s

-1/2 and from 1961.9 J.K

-1.m

-2.s

-1/2 to 1078.2 J.K

-1.m

-2.s

-1/2 from the formula LAT+0%P+20%A to LAT+20%P+20%A respectively for LAT1 and LAT6. In fact, the heat transfer takes place mainly at the contact points between the grains forming the material, the introduction of the PET powder increases the distance between the grains, hence reduces the thermal parameters. These results are consistent with the work of [

30], who found that the thermal conductivity of bricks made from compressed lateritic clay stabilized with coconut fibers decreases with increasing fiber content, but also with the work of [

31], who found that thermal conductivity decreases with increasing content and length of hibiscus cannabinus fibers. Also, the effect of the addition of plastic fibres, straw or polystyrene fabric in the mud brick stabilised with cement, basaltic pumice or gypsum on the thermal properties and the indoor air temperature of a small house was investigated by [

32]. Results showed that the fibres reinforced mud brick house is 56.3% cooler than the concrete brick house in summer. This reduction in thermal parameters is very interesting, because it will allow a reduction in energy consumption by air conditioning in homes built in CEBs based on these formulas. In addition to reducing the thermal parameters of the CEBs, the thermal conductivity values obtained with the introduction of PET powder are lower than those obtained on concrete tile and cement mortar, which are approximately 1.5 W.m

-1.K

-1 [

33,

34,

35].

4. Conclusions

The main objective of this work was to stabilize the lateritic material associated with the powder of PET bottles, in the form of geopolymerized compressed earth blocks (CEBs) using a phosphoric acid solution concentrated at 10M. From the physico-mechanical and thermal characteristics of raw and stabilized materials studied, it appears that the mechanical characteristics increase with the increase of PET powder at a constant phosphoric acid dosage up to the formula LAT+10%P+20%A and decrease beyond 10% of powder, while the thermal characteristics are decreasing. The mineralogical composition remain the same from laterite raw materials to stabilized materials. Moreover, this study made it possible to identify the LAT+10%P+20%A formula as the one presenting the best combined physico-mechanical and thermal characteristics. The following observations were made on CEBs with the formula LAT+%P+20%A:

The water absorption of CEBs dosed with 20% of phosphoric acid is between: 6.73% (LAT+10%P+ 20%A) – 8.24% (LAT+0%P+20%A) for LAT1 and 5.01% (LAT+10%P+20%A) – 7.14% (LAT+0%P+20%A) for LAT6;

The Bulk density of CEBs dosed with 20% phosphoric acid is between: 2.13 g.cm-3 (LAT+0%P+20%A) and 1.69 g.cm-3 (LAT+20%P+20%A) for LAT1 and between 2.22 g.cm-3 (LAT+0%P+ 20%A) and 1.72 g.cm-3 (LAT+20%P+20%A) for LAT6;

The dry compressive strength of 28 days CEBs is between: 4.42 MPa (LAT+0%P+20%A) and 6.92 MPa (LAT+10%P+20%A) for LAT1 and between 4.5 MPa (LAT+0%P+ 20%A) and 6.96 MPa (LAT+10%P+20%A) for LAT6;

The thermal conductivity and effusivity are respectively between: 0.913 W.m-1.K-1, 1962.37 J.K-1.m-2.s-1/2 (LAT+0%P+20%A) and 0.289 W.m-1.K-1, 1078.46 J.K-1.m-2.s-1/2 (LAT+20%P+20%A) for LAT1 and between 0.911 W.m-1.K-1, 1961.9 J.K-1.m-2.s-1/2 (LAT+0%P+20%A) and 0.289 W.m-1.K-1, 1078.2 J.K-1.m-2.s-1/2 for LAT6;

In addition, with this LAT+10%P+20%A formula, for a lateritic CEB of 1 kilogram, up to 3 PET bottles of 1.5l are recycled, thus contributing to the protection of our environment.

These results demonstrate that the lateritic material associated with the PET powder, and stabilized using a solution of phosphoric acid, can be used for making quality compressed earth blocks (CEBs). The CEBs of the LAT+10%P+20%A formula present the optimal combined characteristics of this study, however in order to determine the optimal percentage of PET powder to introduce, intermediate percentages between 5 and 10% will have to be tested in future studies. Also, percentages beyond 20% of phosphoric acid could be tried in further works. In addition, the values of compressive strength, thermal conductivity and effusivity, and water absorption present the CEBs with the formula LAT+10%P+20%A suitable for use in construction in humid environments, however studies on their durability are necessary before approving their use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Marcel Bertrand Hagbe Ntod, Michel Bertrand Mbog and Dieudonné Bitom; Data curation, Marcel Bertrand Hagbe Ntod, Michel Bertrand Mbog, Lionelle Bitom-Mamdem and Rolande Aurelie Tchouateu Kamwa; Formal analysis, Marcel Bertrand Hagbe Ntod, Elie Constantin Bayiga and Rolande Aurelie Tchouateu Kamwa; Funding acquisition, Marcel Bertrand Hagbe Ntod, Michel Bertrand Mbog and Dieudonné Bitom; Investigation, Marcel Bertrand Hagbe Ntod, Lionelle Bitom-Mamdem and Emmanuel Wantou Ngueko; Methodology, Marcel Bertrand Hagbe Ntod, Michel Bertrand Mbog, Lionelle Bitom-Mamdem, Rolande Aurelie Tchouateu Kamwa and Dieudonné Bitom; Project administration, Marcel Bertrand Hagbe Ntod, Michel Bertrand Mbog, Lionelle Bitom-Mamdem and Rolande Aurelie Tchouateu Kamwa; Resources, Marcel Bertrand Hagbe Ntod, Gilbert François NgonNgon, Dieudonné Bitom and Jacques Etame; Software, Marcel Bertrand Hagbe Ntod, Michel Bertrand Mbog, Lionelle Bitom-Mamdem and Elie Constantin Bayiga; Supervision, Michel Bertrand Mbog, Gilbert François NgonNgon, Dieudonné Bitom and Jacques Etame; Validation, Marcel Bertrand Hagbe Ntod, Michel Bertrand Mbog, Lionelle Bitom-Mamdem and Dieudonné Bitom; Visualization, Marcel Bertrand Hagbe Ntod, Michel Bertrand Mbog, Gilbert François NgonNgon and Jacques Etame; Writing—original draft, Marcel Bertrand Hagbe Ntod, Michel Bertrand Mbog, Lionelle Bitom-Mamdem, Elie Constantin Bayiga and Rolande Aurelie Tchouateu Kamwa; Writing—review & editing, Marcel Bertrand Hagbe Ntod, Michel Bertrand Mbog and Lionelle Bitom-Mamdem.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Laboratory for Civil Engineering of Cameroon (LABOGENIE) for extending all the facilities to carry out this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Obonyo, E.A.; Kamseu, E.; Lemougna, P.N.; Tchamba, A.B.; Melo, U.F.M.; Leonelli, C. A Sustainable Approach for the Geopolymerization of Natural Iron-Rich Aluminosilicate Materials. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2014, 6, 5535–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaze, R.C.; Beleuk à Moungam, L.M.; Djouka, M.L.F.; Nana, A.; Kamseu, E.; Chinje, U.F.M.; Leonelli, C. The Corrosion of Kaolinite by Iron Minerals and the Effects on Geopolymerization. Applied Clay Science 2017, 138, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyelami, C.A.; Van Rooy, J.L. A Review of the Use of Lateritic Soils in the Construction/Development of Sustainable Housing in Africa: A Geological Perspective. Journal of African Earth Sciences 2016, 75(1475). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djobo, J.N.Y. Synthesis Factors, Characteristics and Durability of Volcanic Ash-Based GeopolymèreCement. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Sciences, University of Yaoundé I, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchakouté, K.H.; Rüscher, C.H.; Kamseu, E.; Fernanda, A.; Leonelli, C. Influence of the molar concentration of phosphoric acid solution on the properties of métakaolin phosphate based geopolymer cements. Applied Clay Science 2017, (147), 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovits, J. Geopolymer Chemistry & Applications; Geopolymer Institute: Saint-Quentin, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, S.K.; Maitra, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Kumar, S. Microstructural and morphological evolution of fly ash based geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 111, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tome, S.; Etoh, M.A.; Etame, J.; Kumar, S. Improved reactivity of volcanic ash using municipal solid incinerator fly ash for alkali-activated cement synthesis. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2020, 11, 3035–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Castro-Gomes, J.; Jalali, S. Alkali-activated binders: A review Part 1. Historical background, terminology, reaction mechanisms and hydration products. Construction and Building Materials 2008a, (22), 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Castro-Gomes, J.; Jalali, S. Alkali-activated binders: A review. Part 2. About materials and binders manufacture. Construction and Building Materials 2008b, (22), 1315–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sore, S.O.; Messan, A.; Prud’homme, E.; Escadeillas, G.; Tsobnang, F. Stabilization of Compressed Earth Blocks (CEBs) by Geopolymer Binder Based on Local Materials from Burkina Faso. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 165, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondation Ellen Mac Arthur. The new plastics economy, rethinking the future of plastics. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aurelie, R.K.T.; Tome, S.; Chongouang, J.; Eguekeng, I.; Spieß, A.; Fetzer, M.N.A.; Elie, K.; Janiak, C.; Etoh, M. Stabilization of compressed earth blocks (CEB) by pozzolana based phosphate geopolymer binder: Physico-mechanical and microstructural investigations. Clean. Mater. 2022, 4, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboza, A. Relevant textural indicators for the infiltration of treated water in onsite sanitation, Ecole Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées de Paris. 2011; 44p. [Google Scholar]

- Mbesse, C.O. The Paleocene-Eocene boundary in the Douala basin: Biostratigraphy and attempt to reconstruct paleoenvironments. Doctoral Thesis, University of Liège, 2013; p. 221. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Kong, X. Properties and reaction mechanism of phosphoric acid activated metakaolin geopolymer at varied curing temperatures. Cement Concr. Res. 2021, 144, 106425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xia, C.; Hong, X.; Wang, C. Effect of SiO2/Al2O3 molar ratio on microstructure and properties of phosphoric acid-based metakaolin geopolymerss. DEStech Transactions on Materials Science and Engineering 2016.

- Zhang, B.; Guo, H.; Deng, L.; Fan, W.; Yu, T.; Wang, Q. Undehydrated kaolinite as materials for the preparation of geopolymer through phosphoric acid-activation. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 199, 105887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM. C642. Standard test method for density, absorption, and voids in hardened concrete. ASTM Int. 2013, 3. [Google Scholar]

-

NF EN ISO 17892-2; Geotechnical investigation and testing—Laboratory testing of soil—Part 2: Determination of bulk density. 2014.

-

ASTM D5470; Standard test method for thermal transmission properties of thermally conductive electrical insulation materials. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Pancharathi, R.K.; Sangoju, B.; Chaudhary, S. Advances in Sustainable Construction Materials. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; et al. Preparation and characterization of geopolymers based on a phosphoric-acid-activated electrolytic manganese dioxide residue. J. Clean. Prod. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noël, J.; Djobo, Y.; Stephan, D.; Elimbi, A. Setting and hardening behavior of volcanic ash phosphate cement. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, A.S.; Jeong, S.Y. Chemically Bonded Phosphate Ceramics: I, A Dissolution Model of Formation. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2003, 86(11), 1839–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewa, C.N.; Tchakouté, H.K.; Fotio, D.; Claus, H.; Kamseu, E.; Leonelli, C. Water resistance and thermal behaviour of metakaolin-phosphate-based geopolymer cements. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 2018, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, A.; Tatiane, M.; Noël, J.; Djobo, Y.; Tome, S.; Cyriaque, R.; Giogetti, J.; Deutou, N. Lateritic soil based - compressed earth bricks stabilized with phosphate binder. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djobo, J.N.Y.; Tchadjié, L.N.; Tchakoute, H.K.; Kenne, B.B.D.; Elimbi, A.; Njopwouo, D. Synthesis of geopolymer composites from a mixture of volcanic scoria and metakaolin. Integr. Med. Res. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, M.L.; Romagnoli, M.; Pollastri, S.; Gualtieri, A.F. Inorganic polymers from laterite using activation with phosphoric acid and alkaline sodium silicate solution: Mechanical and microstructural properties. Cement and Concrete Research 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedari, J.; Watsanasathaporn, P.; Hirunlabh, J. Development of fibre-based soilcement block with low thermal conductivity. Cem Concr Compos 2005, 27(1), 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millogo, Y.; Morel, J.-C.; Aubert, J.E.; Ghavami, K. Experimental analysis of pressed adobe blocks reinforced with Hibiscus cannabinus fibers. Constr Build Mater 2014, 52, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binici, H.; Aksogan, O.; Bodur, M.N.; Akc, E.; Kapur, S. Thermal isolation and mechanical properties of fibre reinforced mud bricks as wall materials. Construction and Building Materials 2007, 21, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, F.; Serres, L.; Miriel, J.; Bart, M. Study of thermal behaviour of clay wall facing south. Building and Environment 2006, 41, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meukam, P.; Jannot, Y.; Noumowe, A.; Kofane, T.C. Thermophysical characteristics of economical building materials. Construction and Building Materials 2004, 18, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, H.M.; Sharples, S. Developing sustainable residential buildings in Saudi Arabia: A case study. Applied Energy 2011, 88, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).