Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Samples

2.3. Equine Colostrum-Derived MSCs Isolation and Culture

2.4. Characterization of Colostrum-Derived MSCs

2.4.1. Population Doubling Time (PDT) Analysis

2.4.2. CFU (Colony-Forming Unit) Assay

2.4.3. Adhesion and Migration Assays

2.4.4. Multi-Lineage In Vitro Differentiation

2.4.5. Molecular Characterization

2.4.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

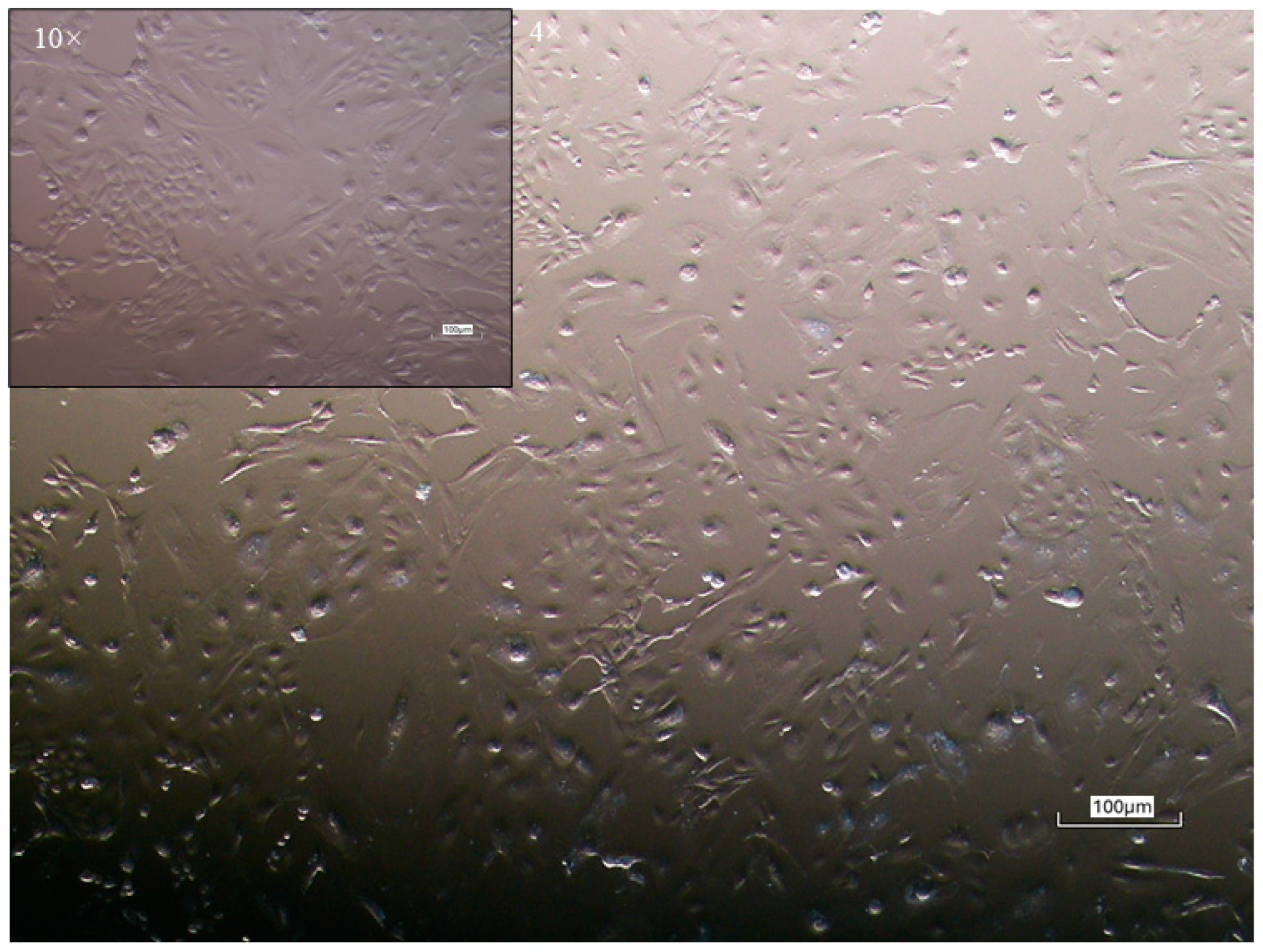

3.1. Isolation and Morphological Characterization of Equine Colostrum-Derived Cell

3.2. Characterization of Colostrum-Derived MSCs

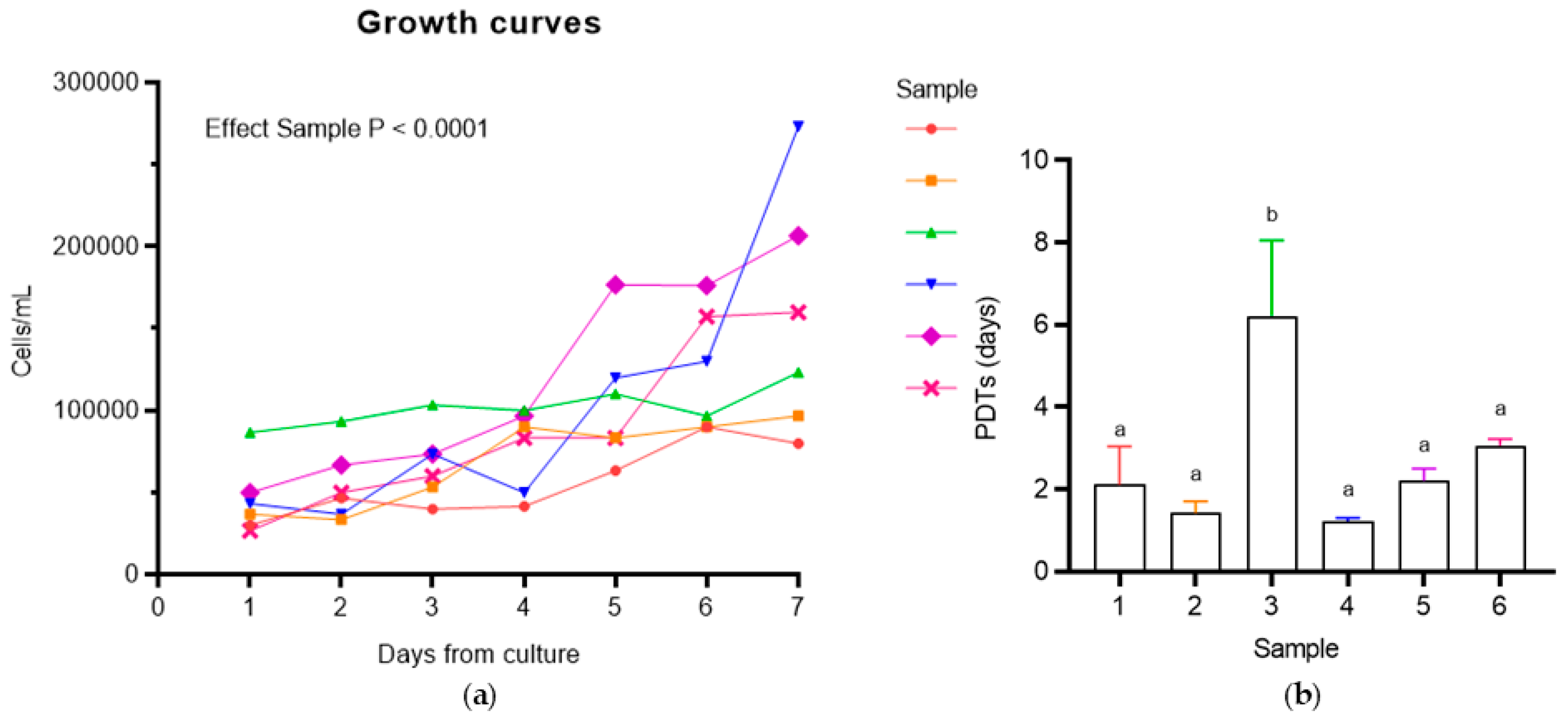

3.4.1. Population Doubling Time (PDT) Analysis

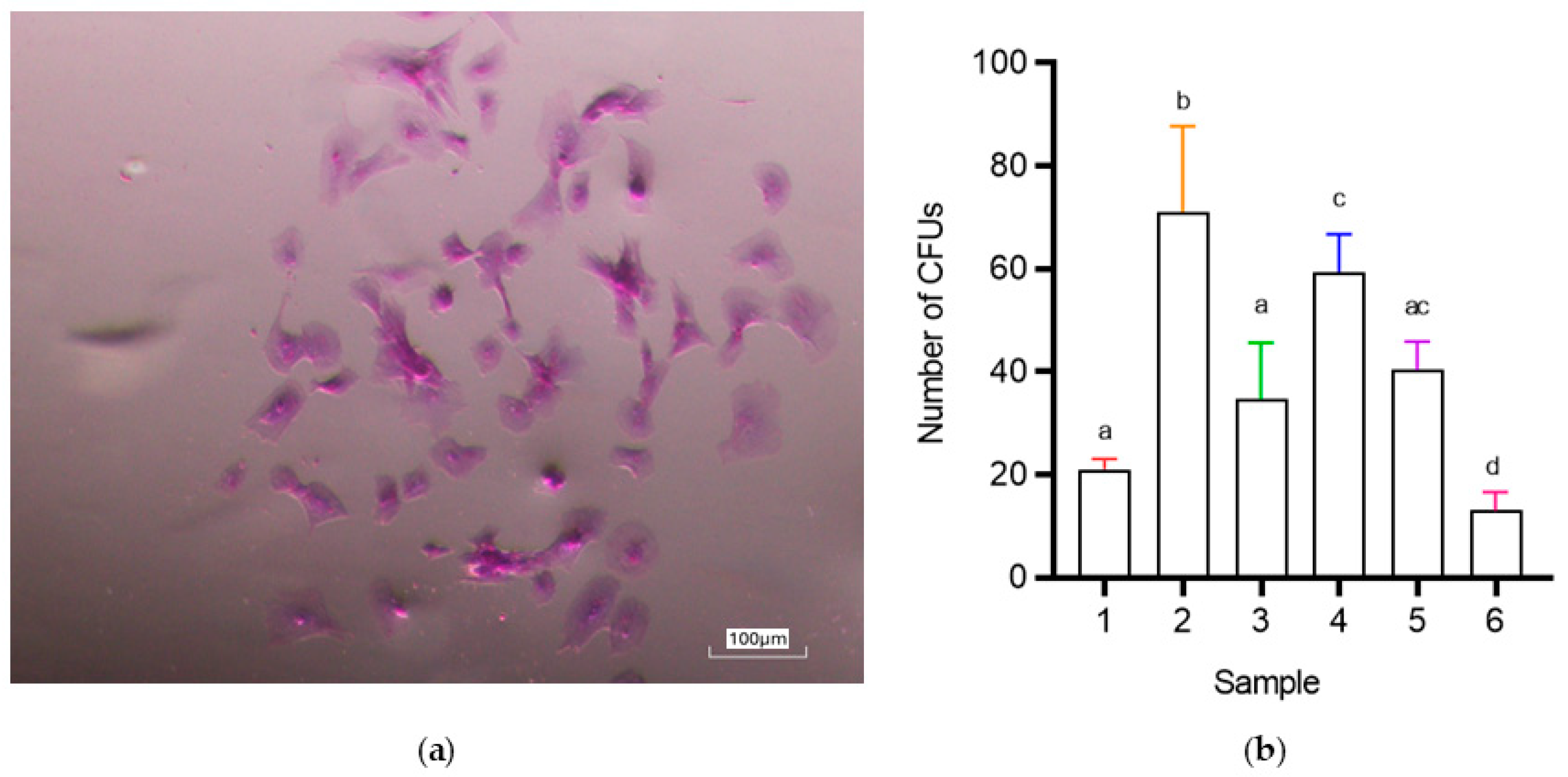

3.4.2. CFU (Colony-Forming Unit) Assay

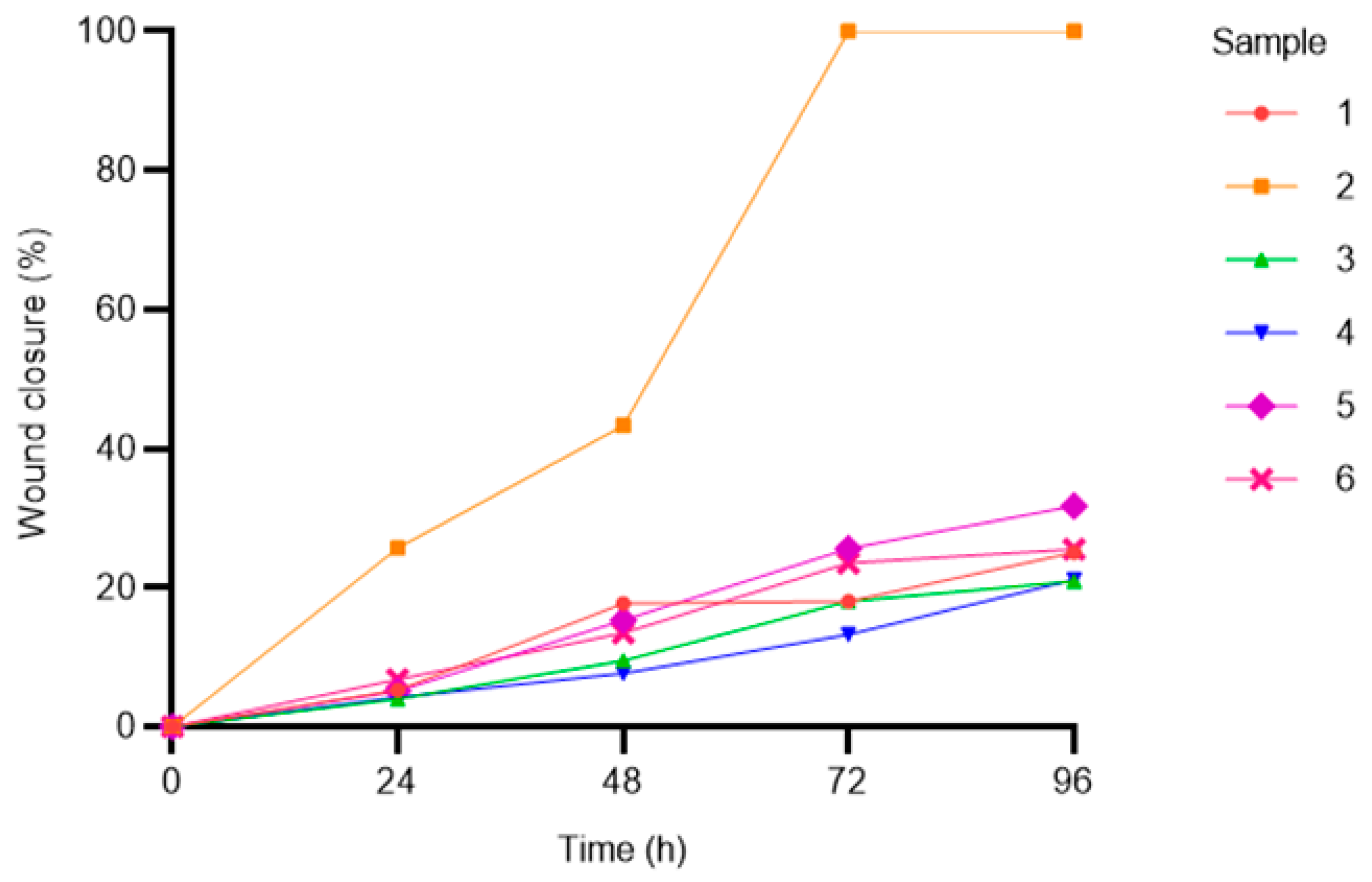

3.4.3. Adhesion and Migration Assays

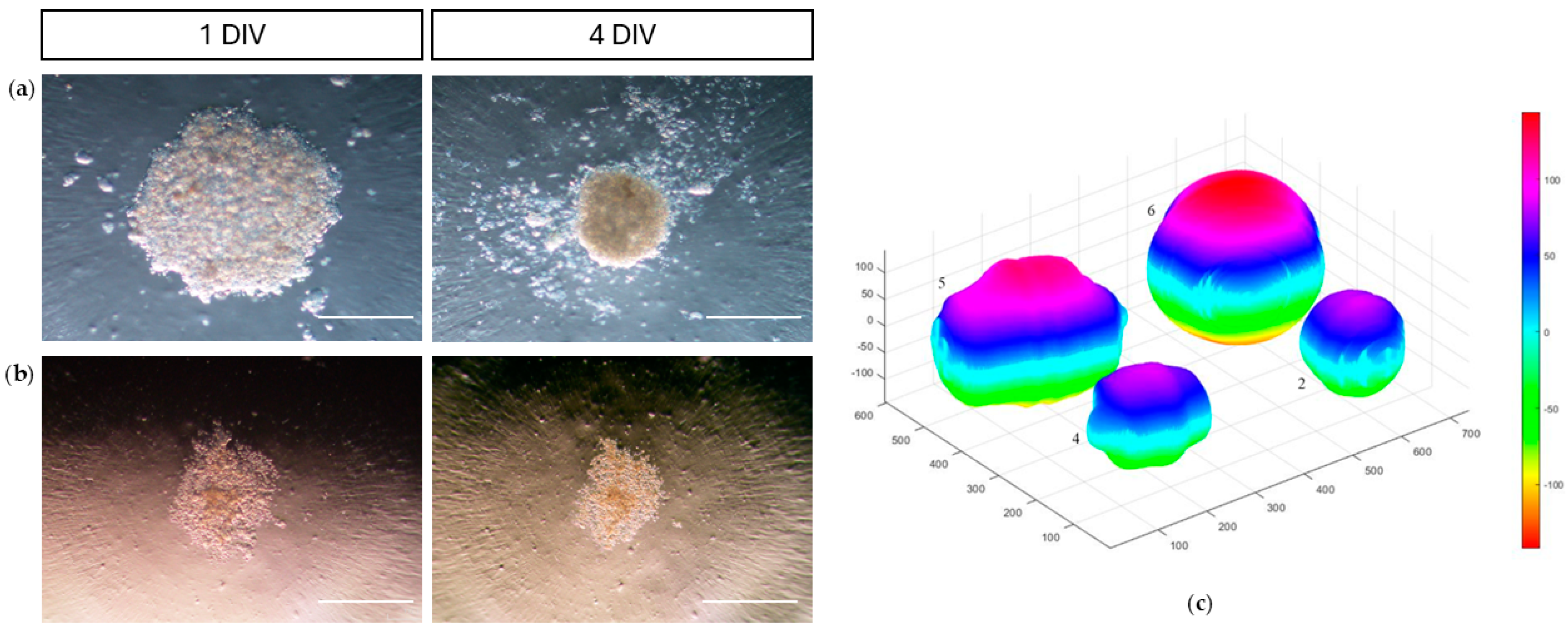

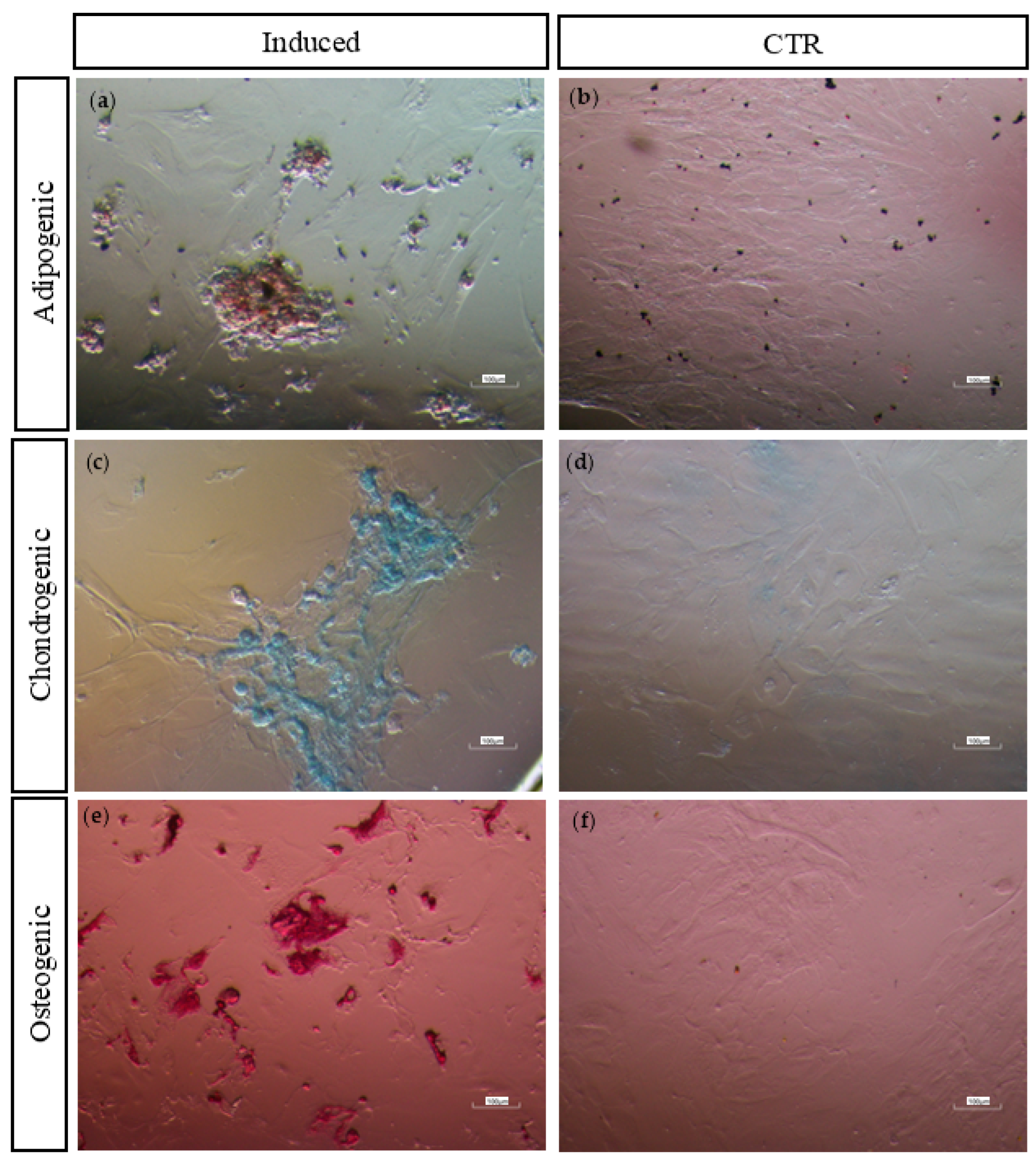

3.4.4. Multi-Lineage In Vitro Differentiation

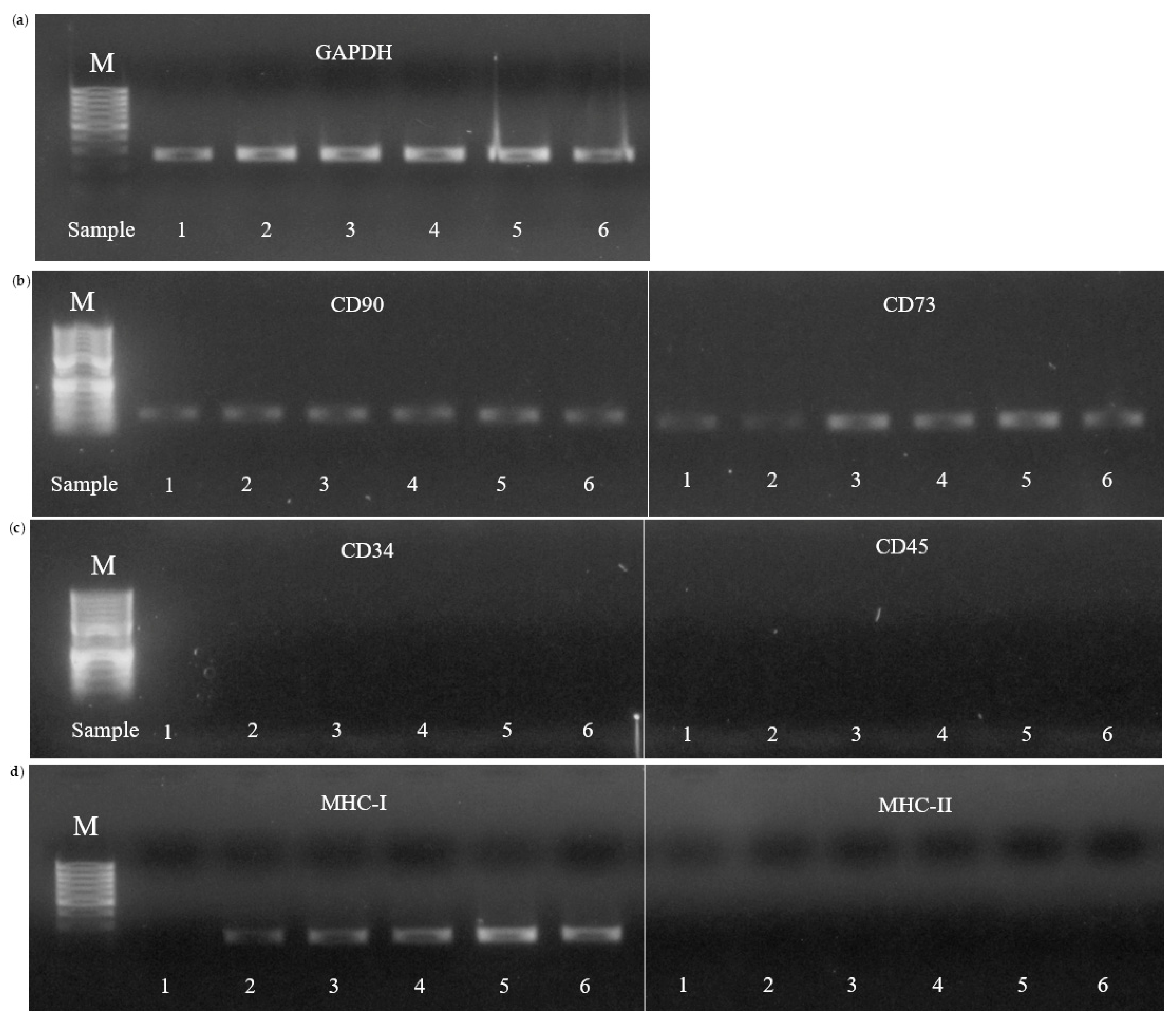

3.4.5. Molecular Characterization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCue, P.M. Colostrum Banking. Equine Reproductive Procedures 2014, 299–301. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, T.C.; de Sobral, G.G.; de França Queiroz, A.E.S.; Chinelate, G.C.B.; Porto, T.S.; Oliveira, J.T.C.; Carneiro, G.F. Characterization of Lyophilized Equine Colostrum. J Equine Vet Sci 2024, 132, 104975. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, G.A.; Goodman, L.B.; Wimer, C.; Freer, H.; Babasyan, S.; Wagner, B. Maternal T-Lymphocytes in Equine Colostrum Express a Primarily Inflammatory Phenotype. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2014, 161, 141–150. [CrossRef]

- Dukes, H.H.; Reece, W.O. Fisiologia Dos Animais Domésticos; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, 2019;

- Pichiri, G.; Lanzano, D.; Piras, M.; Dessì, A.; Reali, A.; Puddu, M.; Noto, A.; Fanos, V.; Coni, C.; Faa, G.; et al. Human Breast Milk Stem Cells: A New Challenge for Perinatologists. JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC AND NEONATAL INDIVIDUALIZED MEDICINE 2016, 5, e050120-1. [CrossRef]

- Indumathi, S.; Dhanasekaran, M.; Rajkumar, J.S.; Sudarsanam, D. Exploring the Stem Cell and Non-Stem Cell Constituents of Human Breast Milk. Cytotechnology 2013, 65, 385–393. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Chong, Y.S.; Choolani, M.A.; Cregan, M.D.; Chan, J.K.Y. Unravelling the Mystery of Stem/Progenitor Cells in Human Breast Milk. PLoS One 2010, 5, e14421. [CrossRef]

- Visvader, J.E. Keeping Abreast of the Mammary Epithelial Hierarchy and Breast Tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 2009, 23, 2563–2577. [CrossRef]

- Visvader, J.E.; Lindeman, G.J. Mammary Stem Cells and Mammopoiesis. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 9798–9801. [CrossRef]

- Patki, S.; Kadam, S.; Chandra, V.; Bhonde, R. Human Breast Milk Is a Rich Source of Multipotent Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Hum Cell 2010, 23, 35–40. [CrossRef]

- Lochter, A. Plasticity of Mammary Epithelia during Normal Development and Neoplastic Progression. 2011, 76, 997–1008. [CrossRef]

- Hassiotou, F.; Geddes, D.T.; Hartmann, P.E. Cells in Human Milk: State of the Science. Journal of Human Lactation 2013, 29, 171–182. [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, I.; Kaingade, P.; Bhonde, R. Breast Milk-Derived Mesenchymal Stem-Like Cells: History and Mystery. Stem cell and Non-stem Cell Components of Breast Milk 2023, 45–53. [CrossRef]

- Cregan, M.D.; Fan, Y.; Appelbee, A.; Brown, M.L.; Klopcic, B.; Koppen, J.; Mitoulas, L.R.; Piper, K.M.E.; Choolani, M.A.; Chong, Y.S.; et al. Identification of Nestin-Positive Putative Mammary Stem Cells in Human Breastmilk. Cell Tissue Res 2007, 329, 129–136. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Zeps, N.; Rigby, P.; Hartmann, P. Reactive Oxygen Species Initiate Luminal but Not Basal Cell Death in Cultured Human Mammary Alveolar Structures: A Potential Regulator of Involution. Cell Death & Disease 2011 2:8 2011, 2, e189–e189. [CrossRef]

- Hassiotou, F.; Beltran, A.; Chetwynd, E.; Stuebe, A.M.; Twigger, A.J.; Metzger, P.; Trengove, N.; Lai, C.L.; Filgueira, L.; Blancafort, P.; et al. Breastmilk Is a Novel Source of Stem Cells with Multilineage Differentiation Potential. Stem Cells 2012, 30, 2164–2174. [CrossRef]

- Twigger, A.J.; Hepworth, A.R.; Tat Lai, C.; Chetwynd, E.; Stuebe, A.M.; Blancafort, P.; Hartmann, P.E.; Geddes, D.T.; Kakulas, F. Gene Expression in Breastmilk Cells Is Associated with Maternal and Infant Characteristics. Scientific Reports 2015 5:1 2015, 5, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Talaei-Khozani, T.; Sani, M.; Owrangi, B. Differentiation of Human Breast-Milk Stem Cells to Neural Stem Cells and Neurons. Neurol Res Int 2014, 2014, 807896. [CrossRef]

- Abd Allah, S.H.; Shalaby, S.M.; El-Shal, A.S.; El Nabtety, S.M.; Khamis, T.; Abd El Rhman, S.A.; Ghareb, M.A.; Kelani, H.M. Breast Milk MSCs: An Explanation of Tissue Growth and Maturation of Offspring. IUBMB Life 2016, 68, 935–942. [CrossRef]

- Briere, C.E.; McGrath, J.M.; Jensen, T.; Matson, A.; Finck, C. Breast Milk Stem Cells. Advances in Neonatal Care 2016, 16, 410–419. [CrossRef]

- Hassiotou, F.; Hartmann, P.E. At the Dawn of a New Discovery: The Potential of Breast Milk Stem Cells. Advances in Nutrition 2014, 5, 770–778. [CrossRef]

- Kaingade, P.; Somasundaram, I.; Sharma, A.; Patel, D.; Marappagounder, D. Cellular Components, Including Stem-Like Cells, of Preterm Mother’s Mature Milk as Compared with Those in Her Colostrum: A Pilot Study. https://home.liebertpub.com/bfm 2017, 12, 446–449. [CrossRef]

- Kaingade, P.M.; Somasundaram, I.; Nikam, A.B.; Sarang, S.A.; Patel, J.S. Assessment of Growth Factors Secreted by Human Breastmilk Mesenchymal Stem Cells. https://home.liebertpub.com/bfm 2016, 11, 26–31. [CrossRef]

- Sam Vijay Kumar, J.; Rajkumar, H.; Nagasamy, S.; Ghose, S.; Subramanian, B.; Adithan, C. Human Colostrum Is a Rich Source of Cells with Stem Cell-Like Properties. SBV Journal of Basic, Clinical and Applied Health Science 2017, 1, 26–31. [CrossRef]

- Sani, M.; Hosseini, S.M.; Salmannejad, M.; Aleahmad, F.; Ebrahimi, S.; Jahanshahi, S.; Talaei-Khozani, T. Origins of the Breast Milk-Derived Cells; an Endeavor to Find the Cell Sources. Cell Biol Int 2015, 39, 611–618. [CrossRef]

- Witkowska-Zimny, M.; Kaminska-El-Hassan, E. Cells of Human Breast Milk. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2017, 22, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Hassiotou, F.; Heath, B.; Ocal, O.; Filgueira, L.; Geddes, D.; Hartmann, P.; Wilkie, T. Breastmilk Stem Cell Transfer from Mother to Neonatal Organs (216.4). The FASEB Journal 2014, 28, 216.4. [CrossRef]

- Aydın, M.Ş.; Yiğit, E.N.; Vatandaşlar, E.; Erdoğan, E.; Öztürk, G. Transfer and Integration of Breast Milk Stem Cells to the Brain of Suckling Pups. Scientific Reports 2018 8:1 2018, 8, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Barinaga, M. Cells Exchanged during Pregnancy Live On. Science (1979) 2002, 296, 2169–2172. [CrossRef]

- Hanson, L.Å.; Silfverdal, S.A.; Strömbäck, L.; Erling, V.; Zaman, S.; Olcén, P.; Telemo, E. The Immunological Role of Breast Feeding. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2001, 12 Suppl 14, 15–19. [CrossRef]

- Hamosh, M. Bioactive Factors in Human Milk. Pediatr Clin North Am 2001, 48, 69–86. [CrossRef]

- Ranera, B.; Lyahyai, J.; Romero, A.; Vázquez, F.J.; Remacha, A.R.; Bernal, M.L.; Zaragoza, P.; Rodellar, C.; Martín-Burriel, I. Immunophenotype and Gene Expression Profiles of Cell Surface Markers of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Equine Bone Marrow and Adipose Tissue. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2011, 144, 147–154. [CrossRef]

- Alipour, F.; Parham, A.; Mehrjerdi, H.K.; Dehghani, H. Equine Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Phenotype and Growth Characteristics, Gene Expression Profile and Differentiation Potentials. Cell Journal (Yakhteh) 2015, 16, 456. [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, P.; Balasubramanian, S.; Majumdar, A. Sen; Ta, M. Isolation, Characterization, and Gene Expression Analysis of Wharton’s Jelly-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells under Xeno-Free Culture Conditions. Stem Cells Cloning 2011, 4, 39–50. [CrossRef]

- In ’t Anker, P.S.; Scherjon, S.A.; Kleijburg-van der Keur, C.; de Groot-Swings, G.M.J.S.; Claas, F.H.J.; Fibbe, W.E.; Kanhai, H.H.H. Isolation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells of Fetal or Maternal Origin from Human Placenta. Stem Cells 2004, 22, 1338–1345. [CrossRef]

- Mihu, C.M.; Rus Ciucă, D.; Soritău, O.; Suşman, S.; Mihu, D. Isolation and Characterization of Mesenchymal Stem Cells from the Amniotic Membrane. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2009, 50, 73–77.

- In ’t Anker, P.S.; Scherjon, S.A.; Kleijburg-van der Keur, C.; Noort, W.A.; Claas, F.H.J.; Willemze, R.; Fibbe, W.E.; Kanhai, H.H.H. Amniotic Fluid as a Novel Source of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Therapeutic Transplantation. Blood 2003, 102, 1548–1549. [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, E.M.; Le Blanc, K.; Dominici, M.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.C.; Deans, R.J.; Krause, D.S.; Keating, A. Clarification of the Nomenclature for MSC: The International Society for Cellular Therapy Position Statement. Cytotherapy 2005, 7, 393–395. [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, K.; Davies, L.C. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and the Innate Immune Response. Immunol Lett 2015, 168, 140–146. [CrossRef]

- Caplan, A.I. MSCs: The Sentinel and Safe-Guards of Injury. J Cell Physiol 2016, 231, 1413–1416. [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, M.E.; Fibbe, W.E. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: Sensors and Switchers of Inflammation. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13, 392–402. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.R.; Teixeira, G.Q.; Santos, S.G.; Barbosa, M.A.; Almeida-Porada, G.; Gonçalves, R.M. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Secretome: Influencing Therapeutic Potential by Cellular Pre-Conditioning. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 425936. [CrossRef]

- Serra, M.; Cunha, B.; Peixoto, C.; Gomes-Alves, P.; Alves, P.M. Advancing Manufacture of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Therapies: Technological Challenges in Cell Bioprocessing and Characterization. Curr Opin Chem Eng 2018, 22, 226–235. [CrossRef]

- Sutton, M.T.; Fletcher, D.; Ghosh, S.K.; Weinberg, A.; Van Heeckeren, R.; Kaur, S.; Sadeghi, Z.; Hijaz, A.; Reese, J.; Lazarus, H.M.; et al. Antimicrobial Properties of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Therapeutic Potential for Cystic Fibrosis Infection, and Treatment. Stem Cells Int 2016, 2016, 5303048. [CrossRef]

- Vizoso, F.J.; Eiro, N.; Cid, S.; Schneider, J.; Perez-Fernandez, R. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome: Toward Cell-Free Therapeutic Strategies in Regenerative Medicine. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, Vol. 18, Page 1852 2017, 18, 1852. [CrossRef]

- Coni, P.; Piras, M.; Piludu, M.; Lachowicz, J.I.; Matteddu, A.; Coni, S.; Reali, A.; Fanos, V.; Jaremko, M.; Faa, G.; et al. Exploring Cell Surface Markers and Cell-Cell Interactions of Human Breast Milk Stem Cells. J Public Health Res 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, N.; Shabani, R.; Ebrahimi, M.; Baghestani, A.; Dehdashtian, E.; Vahabzadeh, G.; Soleimani, M.; Moradi, F.; Katebi, M. Comparative Phenotypic Characterization of Human Colostrum and Breast Milk-Derived Stem Cells. Hum Cell 2020, 33, 308–317. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, S.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Y. Characterization of Stem Cells and Immune Cells in Preterm and Term Mother’s Milk. Journal of Human Lactation 2019, 35, 528–534. [CrossRef]

- Vijay Tukaram Mali, S.M.P. Cytology of the Human Milk in the First Post Partum Week - A Clinical Perspective. J Cytol Histol 2014, s4. [CrossRef]

- Sani, M.; Hosseini, S.M.; Salmannejad, M.; Aleahmad, F.; Ebrahimi, S.; Jahanshahi, S.; Talaei-Khozani, T. Origins of the Breast Milk-Derived Cells; an Endeavor to Find the Cell Sources. Cell Biol Int 2015, 39, 611–618. [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, K. V.; Mezheritskii, S.A.; Stepanenko, N.P.; Gostyukhina, A.A.; Zhukova, O.B.; Kondrat’eva, E.I.; Stepanov, I.A.; Dzyuman, A.N.; Nikolaevskaya, E.E.; Vorob’ev, V.A.; et al. Immunological and Phenotypic Characterization of Cell Constituents of Breast Milk. Cell and Tissue Biology 2016 10:5 2016, 10, 410–415. [CrossRef]

- Twigger, A.J.; Engelbrecht, L.K.; Bach, K.; Schultz-Pernice, I.; Pensa, S.; Stenning, J.; Petricca, S.; Scheel, C.H.; Khaled, W.T. Transcriptional Changes in the Mammary Gland during Lactation Revealed by Single Cell Sequencing of Cells from Human Milk. Nat Commun 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Zeps, N.; Cregan, M.; Hartmann, P.; Martin, T. 14-3-3σ (Sigma) Regulates Proliferation and Differentiation of Multipotent P63-Positive Cells Isolated from Human Breastmilk. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 278–284. [CrossRef]

- Nageeb, M.M.; Saadawy, S.F.; Attia, S.H. Breast Milk Mesenchymal Stem Cells Abate Cisplatin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Adult Male Albino Rats via Modulating the AMPK Pathway. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Pisano, C.; Galley, J.; Elbahrawy, M.; Wang, Y.; Farrell, A.; Brigstock, D.; Besner, G.E. Human Breast Milk-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in the Protection Against Experimental Necrotizing Enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg 2020, 55, 54–58. [CrossRef]

- Borhani-Haghighi, M.; Navid, S.; Mohamadi, Y. The Therapeutic Potential of Conditioned Medium from Human Breast Milk Stem Cells in Treating Spinal Cord Injury. Asian Spine J 2020, 14. [CrossRef]

- Khamis, T.; Abdelalim, A.F.; Abdallah, S.H.; Saeed, A.A.; Edress, N.M.; Arisha, A.H. Breast Milk MSCs Transplantation Attenuates Male Diabetic Infertility Via Immunomodulatory Mechanism in Rats. Adv Anim Vet Sci 2019, 7, 145–153. [CrossRef]

- Khamis, T.; Abdelalim, A.F.; Saeed, A.A.; Edress, N.M.; Nafea, A.; Ebian, H.F.; Algendy, R.; Hendawy, D.M.; Arisha, A.H.; Abdallah, S.H. Breast Milk MSCs Upregulated β-Cells PDX1, Ngn3, and PCNA Expression via Remodeling ER Stress /Inflammatory /Apoptotic Signaling Pathways in Type 1 Diabetic Rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2021, 905. [CrossRef]

- Khamis, T.; Abdelalim, A.F.; Abdallah, S.H.; Saeed, A.A.; Edress, N.M.; Arisha, A.H. Early Intervention with Breast Milk Mesenchymal Stem Cells Attenuates the Development of Diabetic-Induced Testicular Dysfunction via Hypothalamic Kisspeptin/Kiss1r-GnRH/GnIH System in Male Rats. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2020, 1866. [CrossRef]

- Pipino, C.; Mandatori, D.; Buccella, F.; Lanuti, P.; Preziuso, A.; Castellani, F.; Grotta, L.; Di Tomo, P.; Marchetti, S.; Di Pietro, N.; et al. Identification and Characterization of a Stem Cell-Like Population in Bovine Milk: A Potential New Source for Regenerative Medicine in Veterinary. https://home.liebertpub.com/scd 2018, 27, 1587–1597. [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Curtis, L.A.; Dorobantu, L.S.; Sauvageau, D.; Elliott, J.A.W. Cryopreservation of Swine Colostrum-Derived Cells. Cryobiology 2020, 97, 168–178. [CrossRef]

- Danev, N.; Harman, R.M.; Oliveira, L.; Huntimer, L.; Van de Walle, G.R. Bovine Milk-Derived Cells Express Transcriptome Markers of Pluripotency and Secrete Bioactive Factors with Regenerative and Antimicrobial Activity. Scientific Reports 2023 13:1 2023, 13, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Spaas, J.H.; Chiers, K.; Bussche, L.; Burvenich, C.; Van De Walle, G.R. Stem/Progenitor Cells in Non-Lactating Versus Lactating Equine Mammary Gland. https://home.liebertpub.com/scd 2012, 21, 3055–3067. [CrossRef]

- Bussche, L.; Rauner, G.; Antonyak, M.; Syracuse, B.; McDowell, M.; Brown, A.M.C.; Cerione, R.A.; Van De Walle, G.R. Microvesicle-Mediated Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Promotes Interspecies Mammary Stem/Progenitor Cell Growth. J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 24390–24405. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.L.; Kanke, M.; Rauner, G.; Bakhle, K.M.; Sethupathy, P.; Van de Walle, G.R. Comparative Analysis of MicroRNAs That Stratify in Vitro Mammary Stem and Progenitor Activity Reveals Functionality of Human MiR-92b-3p. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2022, 27, 253–269. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, A.P.; Harman, R.M.; Weiss, J.R.; Van de Walle, G. Establishment and Characterization of Equine Mammary Organoids Using a Method Translatable to Other Non-Traditional Model Species. Development 2022, 149. [CrossRef]

- Harman, R.M.; Das, S.P.; Kanke, M.; Sethupathy, P.; Van de Walle, G.R. MiRNA-214-3p Stimulates Carcinogen-Induced Mammary Epithelial Cell Apoptosis in Mammary Cancer-Resistant Species. Commun Biol 2023, 6. [CrossRef]

- Cash, R.S.G. Colostral Quality Determined by Refractometry. Equine Vet Educ 1999, 11, 36–38. [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, H.B.; Canisso, I.F. Colostrum Conductivity, PH and Brix Index as Predictors of Passive Immunity Transfer in Foals. Equine Vet J 2024. [CrossRef]

- Widjaja, S.L.; Salimo, H.; Yulianto, I.; Soetrisno Proteomic Analysis of Hypoxia and Non-Hypoxia Secretome Mesenchymal Stem-like Cells from Human Breastmilk. Saudi J Biol Sci 2021, 28, 4399–4407. [CrossRef]

- Merlo, B.; Pirondi, S.; Iacono, E.; Rossi, B.; Ricci, F.; Mari, G. Viability, in Vitro Differentiation and Molecular Characterization of Equine Adipose Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Cryopreserved in Serum and Serum-Free Medium. Cryoletters 2016, 37, 243–252.

- Bezerra, A.F.; Alves, J.P.M.; Fernandes, C.C.L.; Cavalcanti, C.M.; Silva, M.R.L.; Conde, A.J.H.; Tetaping, G.M.; Ferreira, A.C.A.; Melo, L.M.; Rodrigues, A.P.R.; et al. Dyslipidemia Induced by Lipid Diet in Late Gestation Donor Impact on Growth Kinetics and in Vitro Potential Differentiation of Umbilical Cord Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Goats. Vet Res Commun 2022, 46, 1259–1270. [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, C.; Duchi, S.; Bevilacqua, A.; Lucarelli, E.; Piccinini, F. Long Term Morphological Characterization of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells 3D Spheroids Built with a Rapid Method Based on Entry-Level Equipment. Cytotechnology 2016, 68, 2479–2490. [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.C.; Park, A.Y.; Guan, J.L. In Vitro Scratch Assay: A Convenient and Inexpensive Method for Analysis of Cell Migration in Vitro. Nature Protocols 2007 2:2 2007, 2, 329–333. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, B.; Merlo, B.; Colleoni, S.; Iacono, E.; Tazzari, P.L.; Ricci, F.; Lazzari, G.; Galli, C. Isolation and in Vitro Characterization of Bovine Amniotic Fluid Derived Stem Cells at Different Trimesters of Pregnancy. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2014, 10, 712–724. [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, H.; Hyakusoku, H. Mesengenic Potential and Future Clinical Perspective of Human Processed Lipoaspirate Cells. Journal of Nippon Medical School 2003, 70, 300–306. [CrossRef]

- Heyman, E.; Meeremans, M.; Devriendt, B.; Olenic, M.; Chiers, K.; De Schauwer, C. Validation of a Color Deconvolution Method to Quantify MSC Tri-Lineage Differentiation across Species. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 987045. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, N.; Gulati, B.R.; Kumar, R.; Gera, S.; Kumar, P.; Somasundaram, R.K.; Kumar, S. Immunophenotypic Characterization and Tenogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Isolated from Equine Umbilical Cord Blood. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 2014, 50, 538–548. [CrossRef]

- Corradetti, B.; Lange-Consiglio, A.; Barucca, M.; Cremonesi, F.; Bizzaro, D. Size-Sieved Subpopulations of Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Intervascular and Perivascular Equine Umbilical Cord Matrix. Cell Prolif 2011, 44, 330–342. [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, J.A.; Demers, S.P.; Suzuki, J.; Laflamme, S.; Vincent, P.; Laverty, S.; Smith, L.C. Trophoblast Stem Cell Marker Gene Expression in Inner Cell Mass-Derived Cells from Parthenogenetic Equine Embryos. Reproduction 2011, 141, 321–332. [CrossRef]

- Spaas, J.H.; Schauwer, C. De; Cornillie, P.; Meyer, E.; Soom, A. Van; Van de Walle, G.R. Culture and Characterisation of Equine Peripheral Blood Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Vet J 2013, 195, 107–113. [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Liu, G.; Halim, A.; Ju, Y.; Luo, Q.; Song, G. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Migration and Tissue Repair. Cells 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Merlo, B.; Teti, G.; Lanci, A.; Burk, J.; Mazzotti, E.; Falconi, M.; Iacono, E. Comparison between Adult and Foetal Adnexa Derived Equine Post-Natal Mesenchymal Stem Cells. BMC Vet Res 2019, 15. [CrossRef]

- Iacono, E.; Pascucci, L.; Rossi, B.; Bazzucchi, C.; Lanci, A.; Ceccoli, M.; Merlo, B. Ultrastructural Characteristics and Immune Profile of Equine MSCs from Fetal Adnexa. Reproduction 2017, 154, 509–519. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Raval, A.; Rana, P.; Mahto, S.K. Regenerative Potential of Human Breast Milk: A Natural Reservoir of Nutrients, Bioactive Components and Stem Cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2023, 19, 1307–1327. [CrossRef]

- Ranera, B.; Ordovás, L.; Lyahyai, J.; Bernal, M.L.; Fernandes, F.; Remacha, A.R.; Romero, A.; Vázquez, F.J.; Osta, R.; Cons, C.; et al. Comparative Study of Equine Bone Marrow and Adipose Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Equine Vet J 2012, 44, 33–42. [CrossRef]

- Iacono, E.; Brunori, L.; Pirrone, A.; Pagliaro, P.P.; Ricci, F.; Tazzari, P.L.; Merlo, B. Isolation, Characterization and Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Amniotic Fluid, Umbilical Cord Blood and Wharton’s Jelly in the Horse. Reproduction 2012, 143, 455–468. [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Zhang, N.; Marsano, A.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G.; Zhang, Y.; Lopez, M.J. In Vitro Mesenchymal Trilineage Differentiation and Extracellular Matrix Production by Adipose and Bone Marrow Derived Adult Equine Multipotent Stromal Cells on a Collagen Scaffold. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2013, 9, 858–872. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.; Viswanathan, P.; Chandanala, S.; Prasanna, S.J.; Seetharam, R.N. Expansion and Characterization of Bone Marrow Derived Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Serum-Free Conditions. Scientific Reports 2021 11:1 2021, 11, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Mehrian, M.; Lambrechts, T.; Marechal, M.; Luyten, F.P.; Papantoniou, I.; Geris, L. Predicting in Vitro Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Expansion Based on Individual Donor Characteristics Using Machine Learning. Cytotherapy 2020, 22, 82–90. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.Y.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, R.E.; Kil, T.Y.; Kim, M.K. Evaluation of Stability and Safety of Equine Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Amniotic Fluid for Clinical Application. Front Vet Sci 2024, 11, 1330009. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, C.; Leicht, U.; Rothe, C.; Drosse, I.; Luibl, V.; Röcken, M.; Schieker, M. Effects of Different Media on Proliferation and Differentiation Capacity of Canine, Equine and Porcine Adipose Derived Stem Cells. Res Vet Sci 2012, 93, 457–462. [CrossRef]

- Lange-Consiglio, A.; Corradetti, B.; Meucci, A.; Perego, R.; Bizzaro, D.; Cremonesi, F. Characteristics of Equine Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Amnion and Bone Marrow: In Vitro Proliferative and Multilineage Potential Assessment. Equine Vet J 2013, 45, 737–744. [CrossRef]

- Hillmann, A.; Ahrberg, A.B.; Brehm, W.; Heller, S.; Josten, C.; Paebst, F.; Burk, J. Comparative Characterization of Human and Equine Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Basis for Translational Studies in the Equine Model. Cell Transplant 2016, 25, 109–124. [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, I.; Kaingade, P.; Bhonde, R. Applications of Breast Milk-Derived Cell Components: Present and Future Perspectives. Stem cell and Non-stem Cell Components of Breast Milk 2023, 71–77. [CrossRef]

- Kamm, J.L.; Parlane, N.A.; Riley, C.B.; Gee, E.K.; Dittmer, K.E.; McIlwraith, C.W. Blood Type and Breed-Associated Differences in Cell Marker Expression on Equine Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Including Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II Antigen Expression. PLoS One 2019, 14. [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, L. V.; Pezzanite, L.M.; Antczak, D.F.; Felippe, M.J.B.; Fortier, L.A. Equine Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Are Heterogeneous in MHC Class II Expression and Capable of Inciting an Immune Response in Vitro. Stem Cell Res Ther 2014, 5. [CrossRef]

- Joel, M.D.M.; Yuan, J.; Wang, J.; Yan, Y.; Qian, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Mao, F. MSC: Immunoregulatory Effects, Roles on Neutrophils and Evolving Clinical Potentials. Am J Transl Res 2019, 11, 3890.

| Adipogenic | Chondrogenic | Osteogenic |

| DMEM | DMEM | DMEM |

| 10% FBS | 1% FBS | 10% FBS |

| 1 µM DXM 2 (removed after 6 days) |

0.1 µM DXM 2 | 0.1 µM DXM 2 |

| 0.5 mM IBMX 1 (removed after 3 days) |

50 nM AA2P 4 | 50 µM AA2P 4 |

| 10 µg/mL insulin | 6.25 µg/mL insulin | 10 mM BGP 5 |

| 0.1 mM indomethacin | 10 ng/mL hTGF-β1 3 |

| Primers | References | Sequences (5’ →3’) | bp |

| MSC marker | |||

| CD90 | [78] | F: TGCGAACTCCGCCTCTCT R: GCTTATGCCCTCGCACTTG |

93 |

| CD73 | [78] | F: GGGATTGTTGGATACACTTCAAAAG R: GCTGCAACGCAGTGATTTCA |

90 |

| Hematopoietic markers | |||

| CD34 | [78] | F: CACTAAACCCTCTACATCATTTTCTCCTA R: GGCAGATACCTTGAGTCAATTTCA |

101 |

| CD45 | [78] | F: TGATTCCCAGAAATGACCATGTA R: ACATTTTGGGCTTGTCCTGTAAC |

101 |

| MHC markers | |||

| MHC-I | [79] | F: GGAGAGGAGCAGAGATACA R: CTGTCACTGTTTGCAGTCT |

218 |

| MHC-II | [79] | F: TCTACACCTGCCAAGTG R: CCACCATGCCCTTTCTG |

178 |

| Housekeeping | |||

| GAPDH | [80] | F: GTCCATGCCATCACTGCCAC R: CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTG |

262 |

| Sample | Volume (mL) | Brix Index (%) |

Cell Yeld (×10³ cells/mL) |

Days to Confluence |

Mean PDTs (days) |

Number of CFU |

| 1 | 25 | 25 | 260 | 10 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 21 ± 2 |

| 2 | 23 | 29.5 | 30 | 10 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 71 ± 16.7 |

| 3 | 17 | 27 | 300 | 11 | 6.2 ± 1.8 | 34.7 ± 11 |

| 4 | 20 | 26 | 500 | 8 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 59.3 ± 7.4 |

| 5 | 21 | 35 | 480 | 11 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 40.3 ± 5.5 |

| 6 | 11 | 28 | 400 | 11 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 13 ± 3.6 |

| Mean | 19.5 | 28.4 | 328.3 | 10.2 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 39.9 ± 7.7 |

| Sample | MSC marker |

Hematopoietic markers |

MHC markers | |||

| CD 90 | CD73 | CD34 | CD 45 | MHC-I | MHC-II | |

| 1 | + | + | - | - | . | - |

| 2 | + | + | - | - | +/– | - |

| 3 | + | + | - | - | +/– | - |

| 4 | + | + | - | - | +/– | - |

| 5 | + | + | - | - | +/– | - |

| 6 | + | + | - | - | +/– | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).