1. Introduction

Land-use changes driven by urbanization have severely impacted natural ecosystems, mainly by reducing habitat quality and connectivity [

1]. Urban areas experience rapid biodiversity decline due to land cover change, infrastructure expansion, and industrial activity, which diminish ecosystem services [

2]. Consequently, there is an urgent need to analyze habitat quality quantitatively and establish sustainable management strategies [

3].

The Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs (InVEST) model has emerged as a valuable tool for assessing ecosystem services. Specifically, the Habitat Quality module within InVEST enables the spatial quantification of ecosystem health based on land use, threat factors, and sensitivity indices [

4]. This approach allows the identification of conservation priorities by analyzing the impact of threats such as habitat fragmentation, pollution, and human activities [

5].

Biotope maps are increasingly used as foundational data for assessing habitat distribution and ecological functions. These maps visually classify habitat suitability and ecological value in spatial formats and are widely applied in urban planning and ecological restoration [

6]. Recent studies have integrated biotope map data with the InVEST model to assess habitat quality comprehensively [

7].

Hong et al. [

8] applied InVEST and biotope data to Jeju Island to analyze habitat quality changes from 1989 to 2019, highlighting the influence of urban development and identifying priority areas for protection. Similarly, Wang et al. [

1] examined urban areas in China and emphasized the importance of preserving peri-urban green spaces. These studies provide a scientific foundation for land use planning and policymaking to enhance ecosystem services [

9].

Recent advances include integrating Bayesian networks with InVEST to refine threat interactions and using high-resolution spatial data and remote sensing technologies for highly accurate habitat assessments [

5,

10].

In this study, we aimed to quantitatively assess the habitat quality of Gochang-gun using a biotope map integrated with the InVEST model. This study focused on areas with high land-use intensity to evaluate the model’s applicability and explore the biotope map’s utility. Moreover, the spatial analysis of threat factors enables the identification of vulnerable areas and supports the formulation of policy responses.

This approach moves beyond ecological status assessments by offering quantitative data that are applicable to urban planning, environmental impact assessments, and the implementation of nature-based solutions. Our findings provide a scientific basis for enhancing the resilience of urban ecosystems and conserving biodiversity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

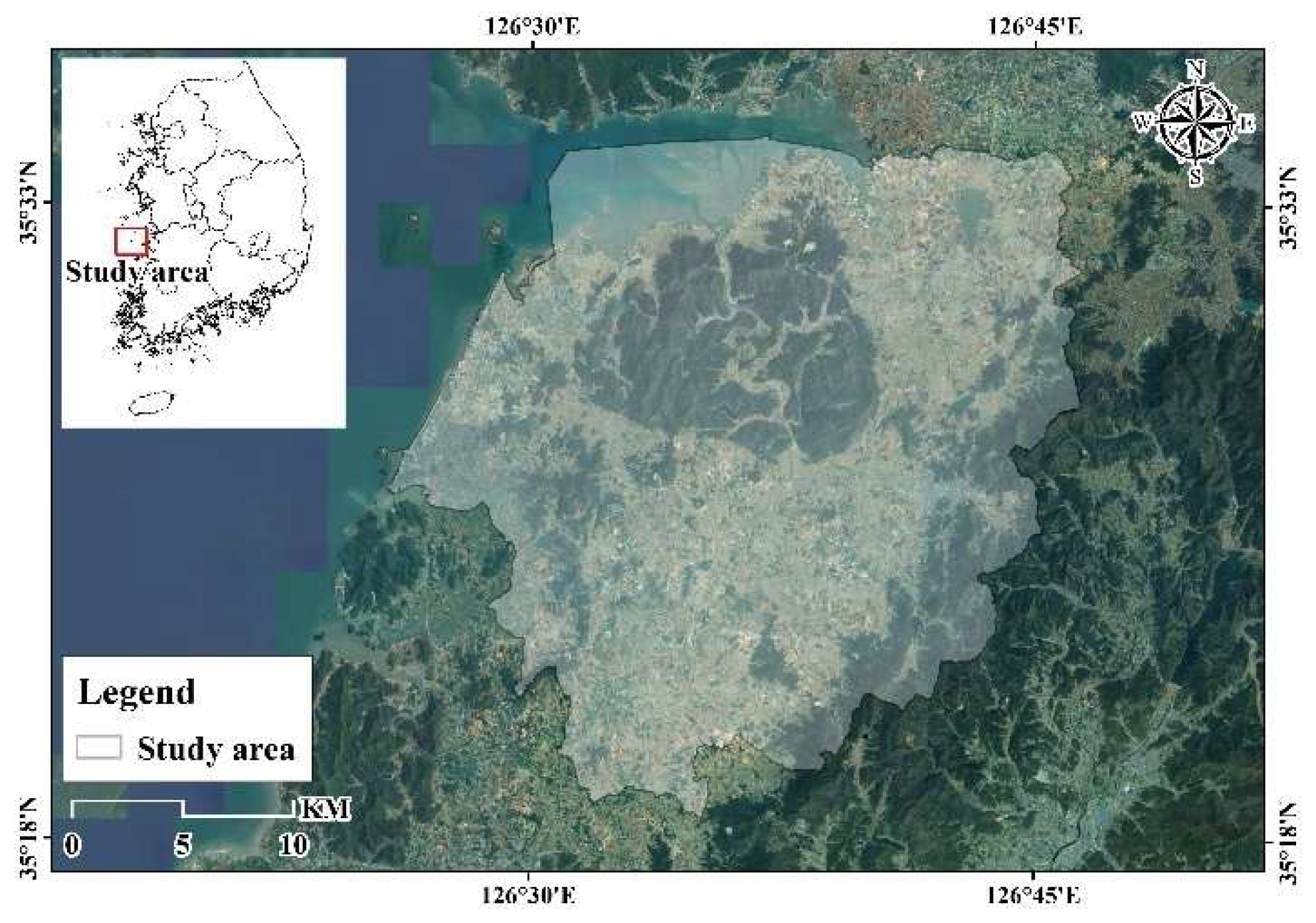

The geographic location of the study area is shown in

Figure 1. Gochang-gun is in the southwestern part of Jeollabuk-do, South Korea, bordered by inland areas to the southeast and the West Sea coast to the northwest. The region is predominantly hilly with narrow alluvial plains, and Seonunsan Provincial Park, a designated protected area, is situated in the northern part. Gochang-gun spans between 126° 26′ and 126° 46′ E and between 35° 17′ and 35° 34′ N, covering approximately 31 km east to west and 31.5 km north to south [

11]. The 10-year average annual temperature is 13.4 °C(–18–37.7 °C). The average annual precipitation over the same period was 1,238.5 mm (966.3–1,671.7 mm) [

12].

Five areas within Gochang-gun have been designated as protected: the Ungok Wetland, West Coast Tidal Flats, Dolmen Heritage Site, Seonunsan Provincial Park, and Dongnim Reservoir Wildlife Protection Area [

11]. The Ungok Wetland is a mountainous terrain-type wetland characterized by 12 vegetation types across 88 classified units. It includes diverse wetland forms such as alluvial wetlands and spring-fed systems. Seonunsan Provincial Park is home to several natural monuments, including the Camellia Forest (Natural Monument No. 184), Jangsasong Pine Tree (No. 354), and Climbing Fig Tree (No. 368) [

11].

Furthermore, the entire administrative area of Gochang-gun has been designated as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. To support the conservation of local ecosytems and promote their sustainable use, the region is systematically managed through a zonation scheme comprising core, buffer, and transition zones.

2.2. Study Method

This study employed the habitat quality module of the InVEST model to quantitatively evaluate the habitat conditions in Gochang-gun.

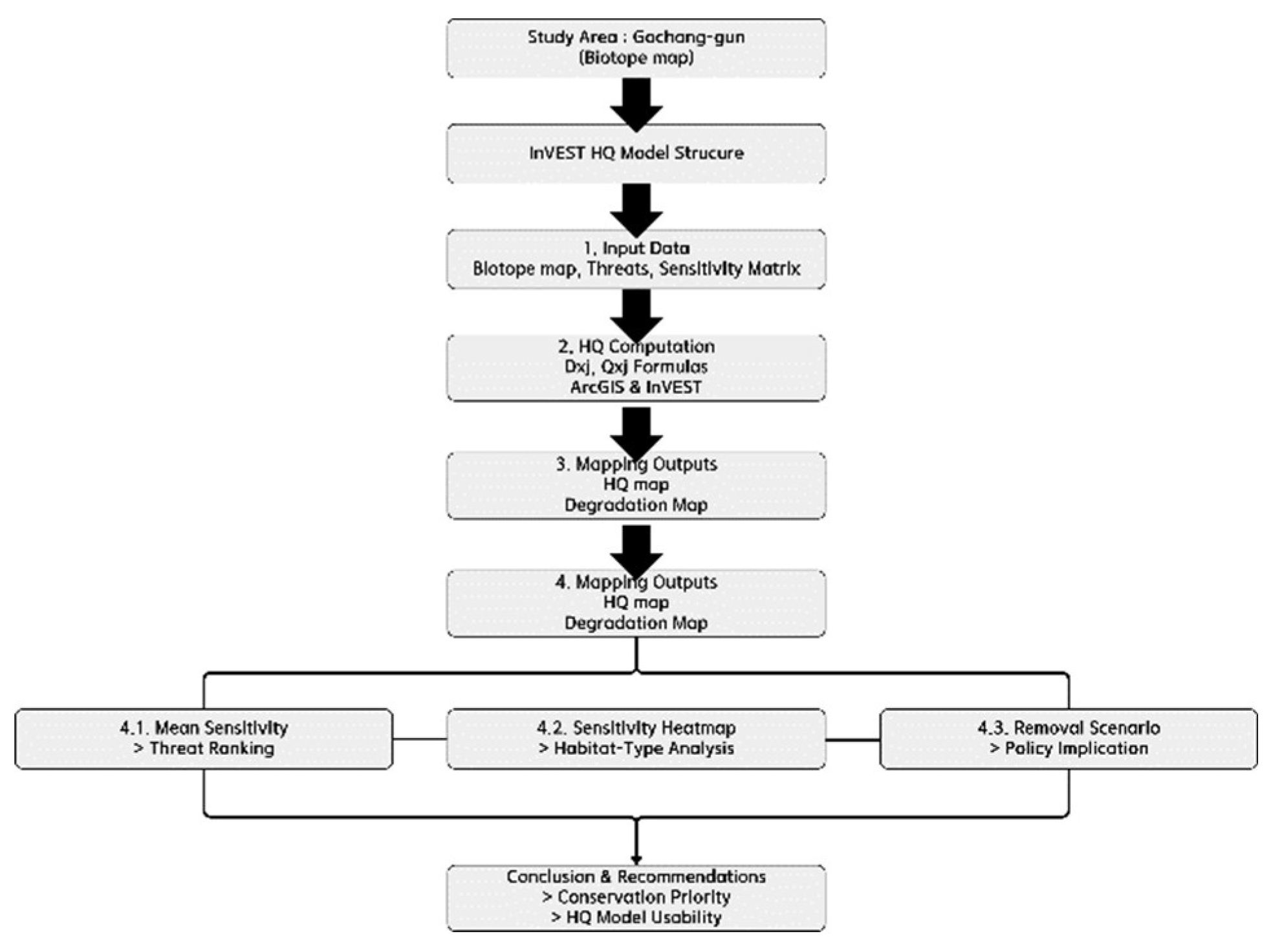

Figure 2 illustrates the overall research workflow and methodology.

2.2.1. Biotope Map

Biotope maps developed under the Natural Environment Conservation Act (Act No. 2024-251, 2024.12.05) have been mandatory for local governments at the city level and above since 2018. It incorporates ecological and environmental characteristics and serves as foundational data for environmentally sustainable urban planning [

13,

14].

Originating in Germany in the 1970s, biotope mapping was designed to support the conservation of natural and semi-natural ecosystems, particularly in rural areas [

15,

16]. Biotope maps include information on land characteristics (land cover and use), ecological features (green cover, disturbance levels, and soil traits), and biological attributes (urban forests and species composition), offering comprehensive data on both the biotic and abiotic components of the environment [

16].

2.2.2. InVEST Model

The InVEST model developed by Sharma et al. [

17] was designed to assess ecosystem services and quantify the effects of human activities on habitats [

18]. The key inputs include land-use/land-cover (LULC) data, threat factors, weights, maximum influence distances, and habitat sensitivity matrixes [

19]. In this study, the LULC input was replaced with a biotope map.

The model calculates habitat degradation (D

xj) and quality (Q

xj) at the pixel level, which is useful for prioritizing conservation and identifying biodiversity hotspots [

20].

Key model equations define degradation (Dxj) and habitat quality (Qxj) using inputs such as the threat factor weights (Wi), raster values (Rix), biotope accessibility (βj), sensitivity (Sji), distance decay functions, and a habitat presence indicator (Hj).

The habitat quality formula defines Qxj as the habitat quality at location x, where Hj is a binary indicator denoting whether the biotope type is considered a habitat (1) or not (0), and k is a scaling constant (default value: 0.5).

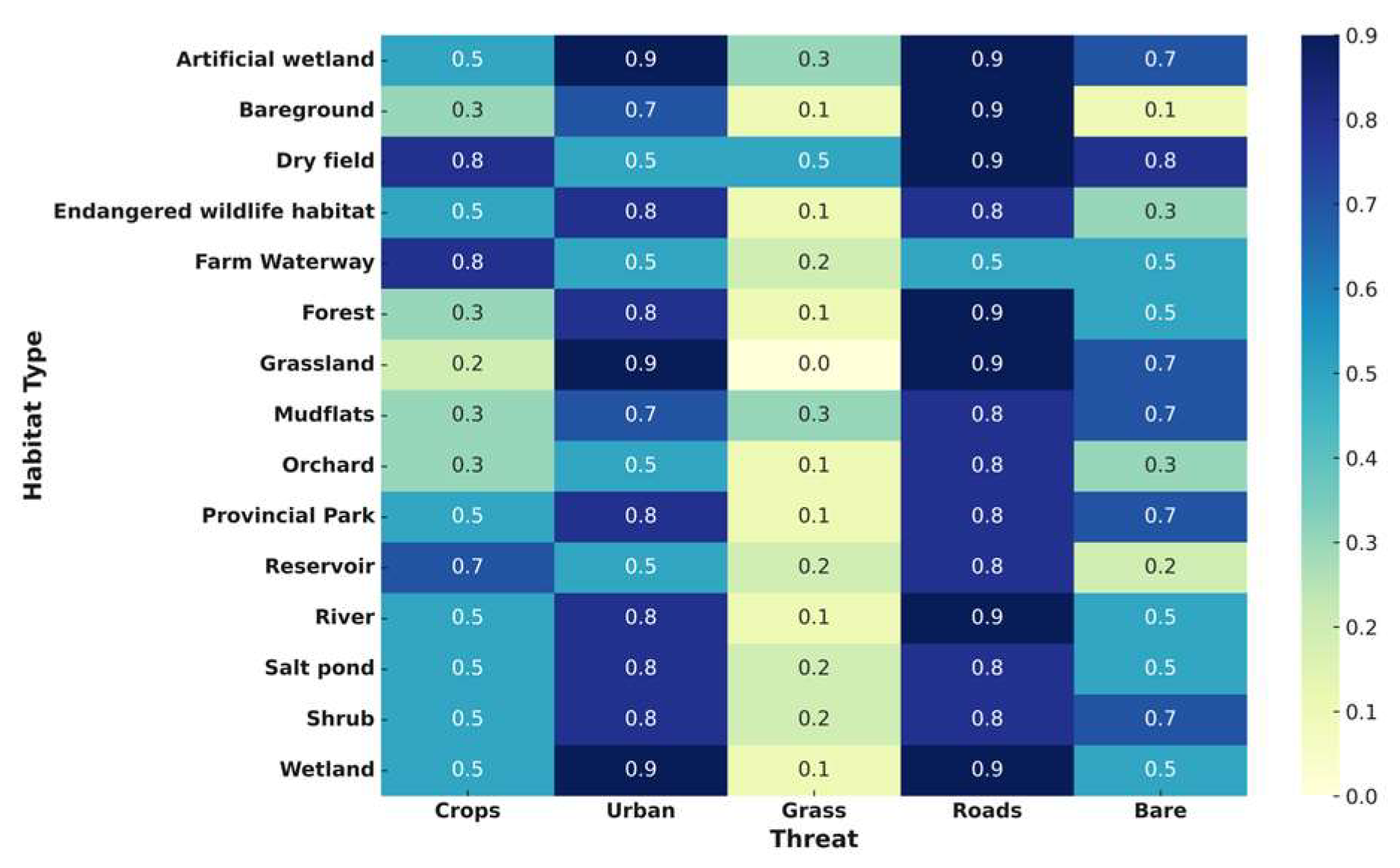

The sensitivity values assigned to each habitat type for the specific threat factors and the attributes of the threat factors used in the model are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively.

2.2.3. Assessment of Threat Sensitivity and Model Input Validation

We conducted three supplementary analyses to enhance the policy relevance of the habitat quality model.

Average sensitivity across threat factors was estimated to identify the most influential factors in habitat degradation.

A heatmap visualizing sensitivity by habitat type was developed to detect spatial vulnerabilities.

Scenario-based threat-removal simulations were used to compare habitat quality changes and derive conservation priorities.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Analysis of Habitat Quality and Threat Levels

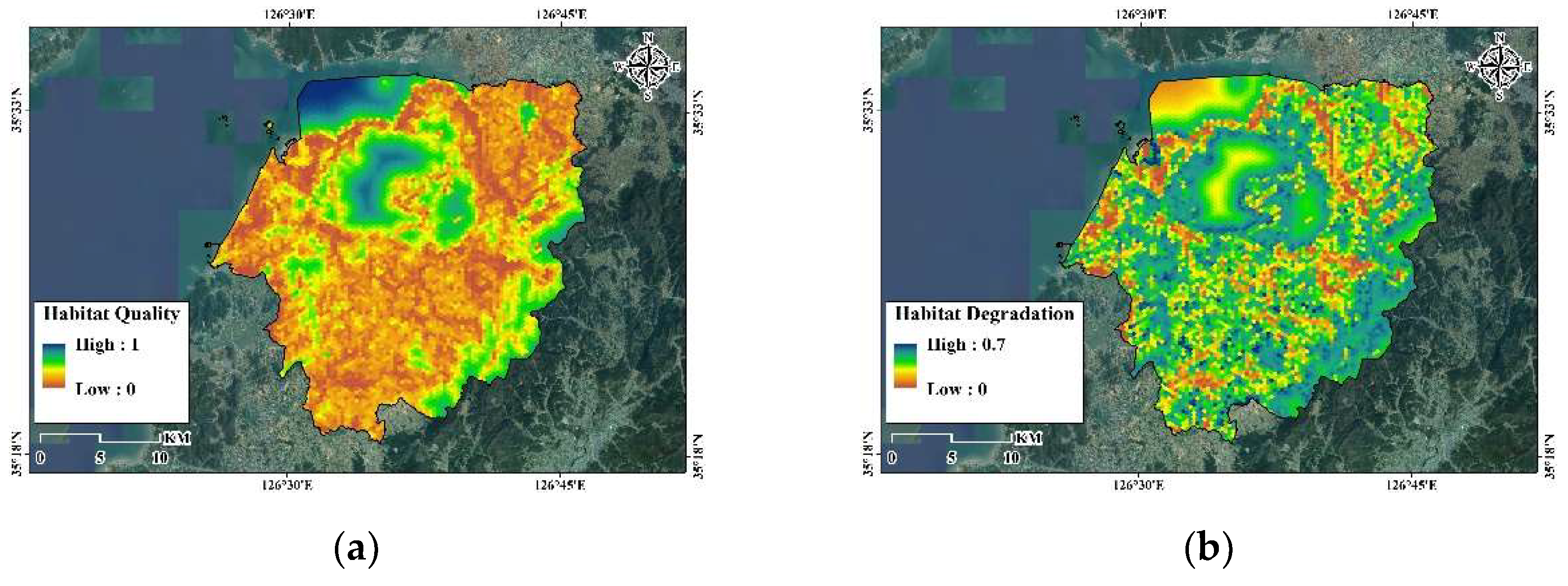

The spatial distribution of habitat quality across Gochang-gun is shown in

Figure 3a. Areas such as the Gochang-Buan tidal flat, Dongnim Reservoir, and Seonunsan Provincial Park had high habitat quality scores (> 0.8). In contrast, the habitat quality of agricultural land and urban areas near Gochang-eup was low, often scoring< 0.2.

The threat level distribution shown in

Figure 3b indicates relatively high values (> 0.6) in areas characterized by roads and agricultural zones. These locations were identified as the major contributors to habitat degradation in this region.

3.2. Quantitative Analysis

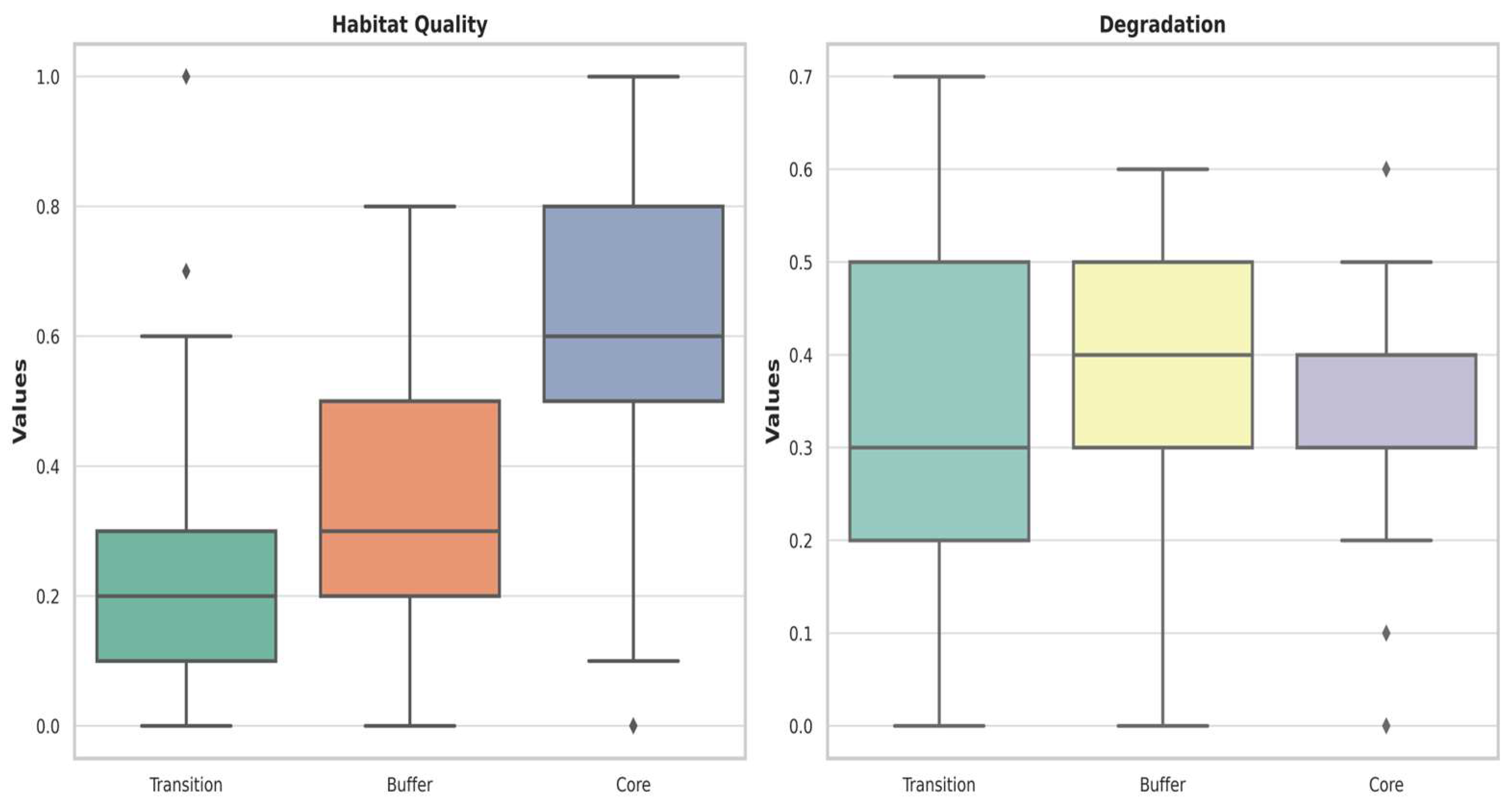

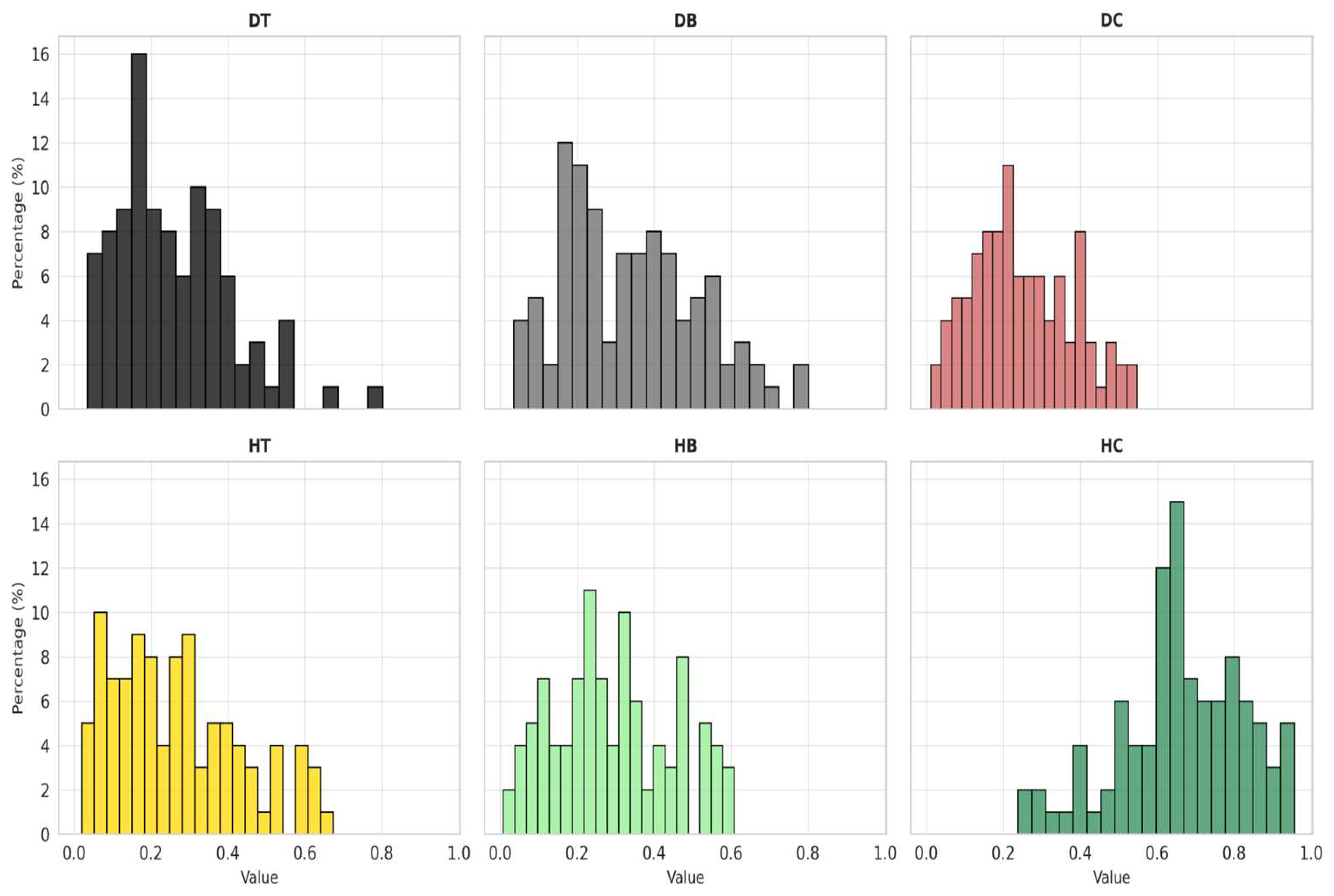

The statistical outcomes of habitat quality and threat levels were visualized. The Gochang Biosphere Reserve was categorized into core, buffer, and transitional zones.

Habitat quality was highest in the core zone and relatively lower in the transitional zone. In particular, the median habitat quality in the core zone exceeded 0.6, indicating a better conservation status than in the other zones (

Figure 4).

Histogram analysis revealed that most habitat quality values ranged from 0.2 to 0.4. A multimodal pattern was observed in the habitat quality transition zone, where low-quality habitats tended to be concentrated (

Figure 5).

These findings suggest that habitat conditions vary markedly with land-use type and highlight the need to establish tailored conservation strategies for each land-use category.

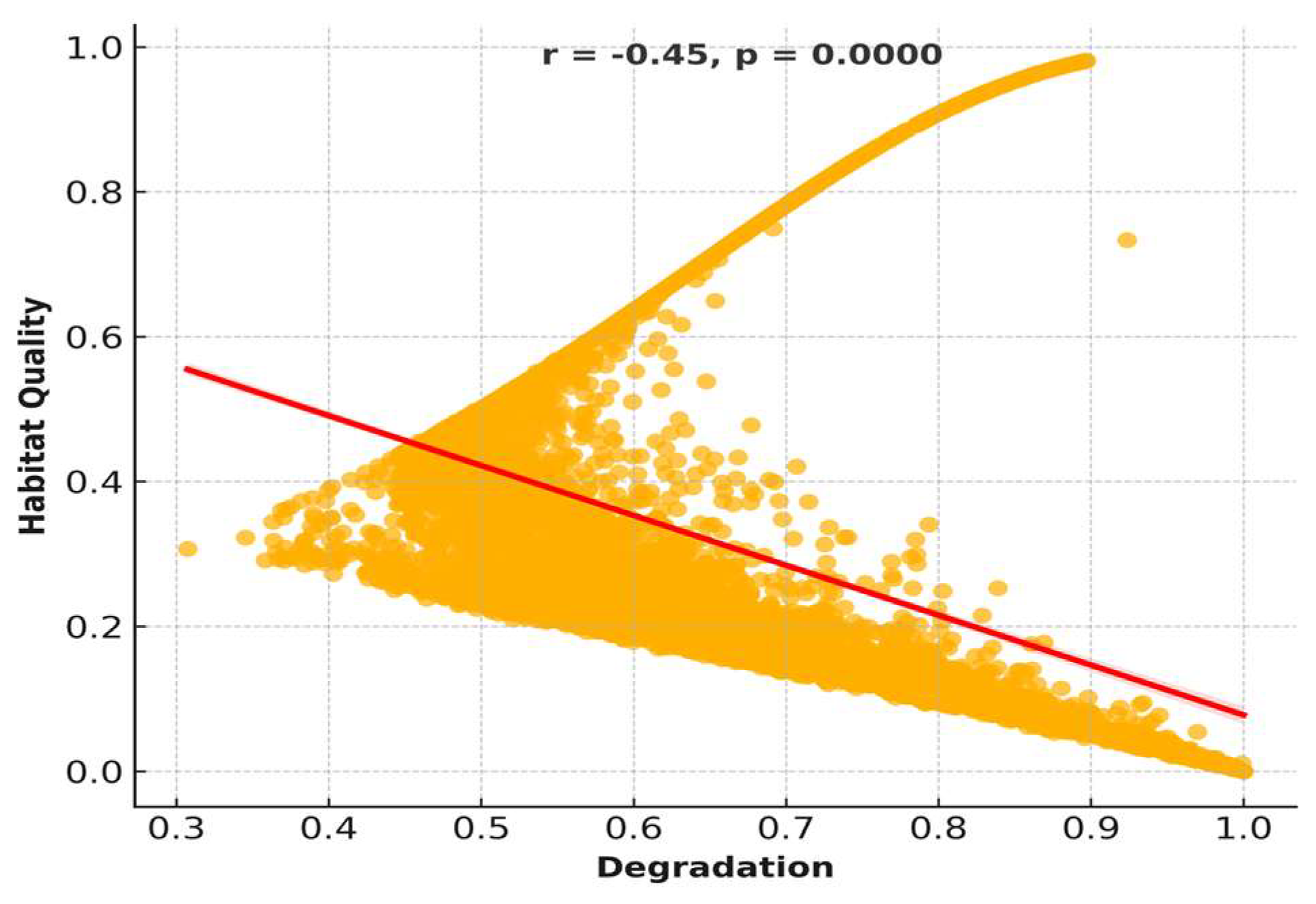

3.3. Correlation Analysis Between Habitat Quality and Degradation

Correlation analysis examined the relationship between habitat quality and degradation (

Figure 6). Linear regression revealed an R² value of 0.2025, with a slope of 0.6887, indicating a statistically significant negative relationship. This suggests that increasing threat levels will lead to a notable decline in habitat quality. In particular, areas with low habitat quality experienced sharp increases in degradation, emphasizing the need for prioritized management in high-risk areas.

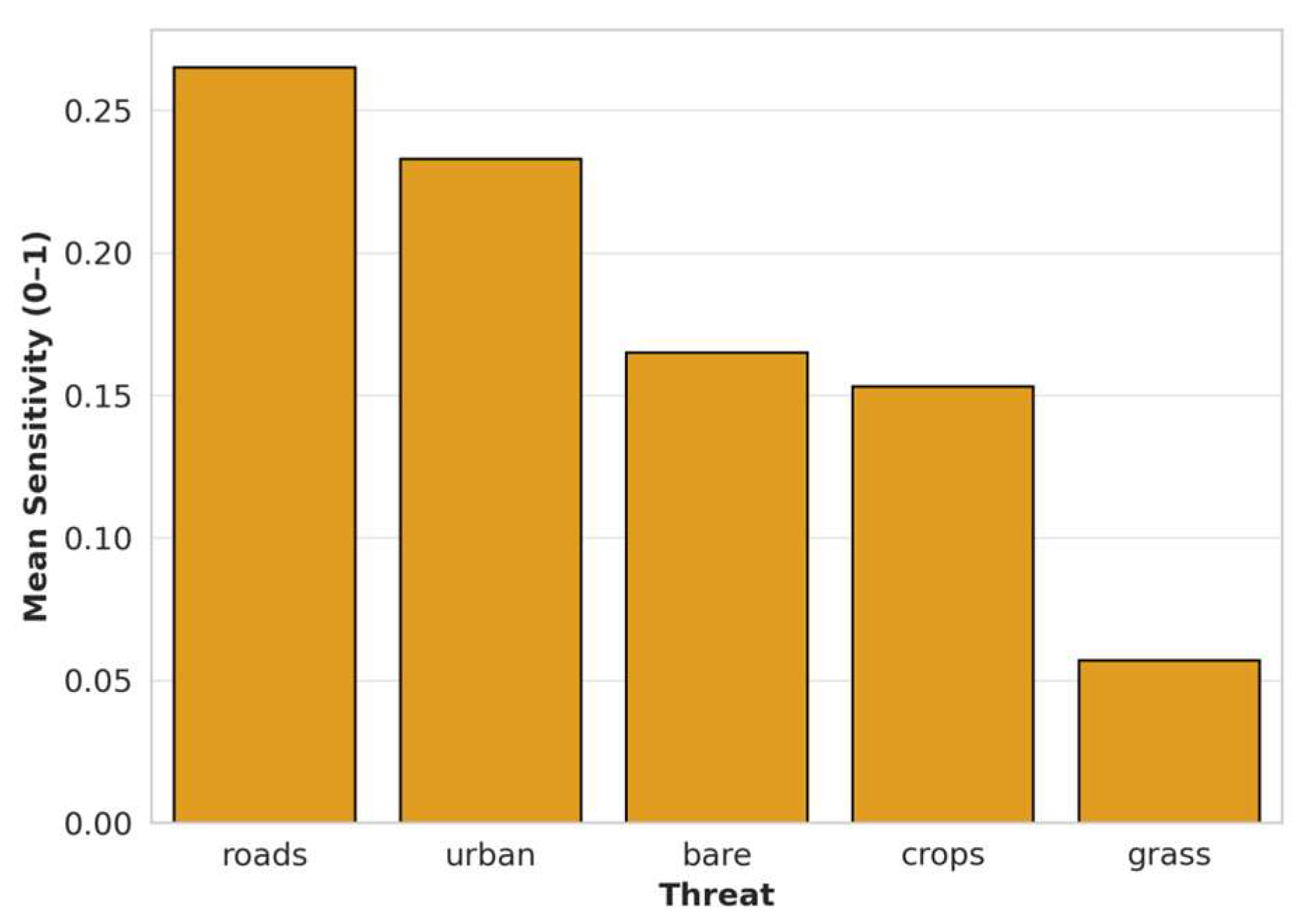

3.4. Diagnosis of Threat Factors for Habitat Protection

We conducted a detailed analysis of threat sensitivities and validated the model inputs with a view to establishing effective conservation strategies. The average sensitivity of each habitat type to individual threats is shown in

Figure 7.

The analysis revealed that, overall, habitats were most sensitive to urban areas and roads, indicating their widespread and severe impacts on various habitat types. Conversely, average sensitivity to grasslands was the lowest (approximately 0.06), suggesting minimal influence.

The matrix of habitat-type sensitivity to threat factors is shown in

Figure 8, where the degree of sensitivity is expressed on a scale from 0 to 1. Higher values indicate greater vulnerability. Most habitat types showed consistently high sensitivity to urban and road-related threats, highlighting the impact of urbanization and infrastructure expansion on ecological degradation.

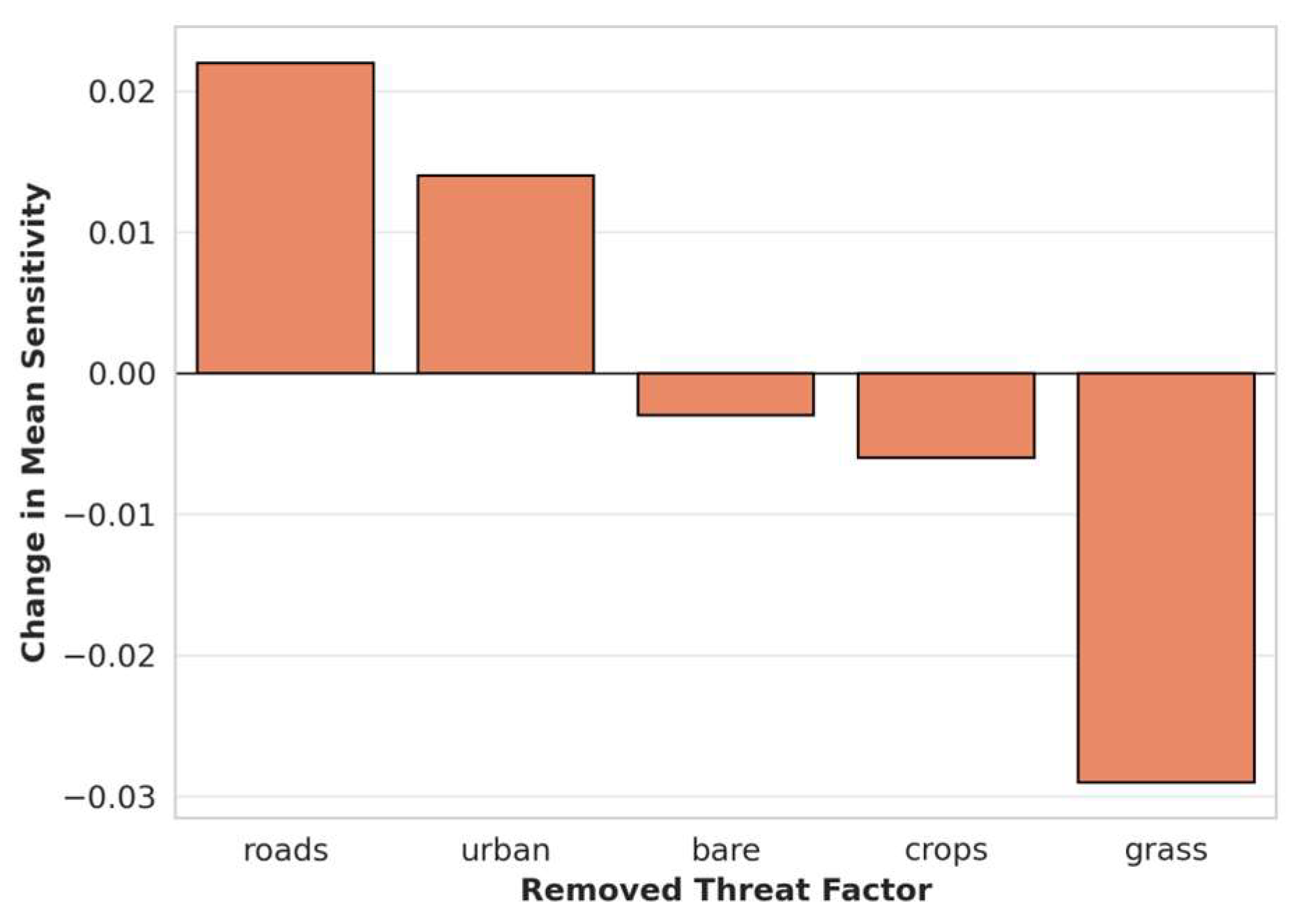

Finally, the impact of removing individual threats on overall sensitivity is shown in Figure 9. The removal of roads resulted in the most significant reduction in sensitivity, followed by the removal of urban areas. These findings suggest that these two factors are the most detrimental and should be prioritized in habitat management strategies. Interestingly, grassland removal slightly increased the sensitivity of some habitat types, indicating positive ecological interactions.

4. Discussion

This study quantitatively assessed the habitat quality in Gochang-gun using a biotope map and the InVEST model while also analyzing the spatial influence of threat factors. These findings provide a scientific foundation for developing ecosystem conservation strategies at a regional level.

First, the spatial analysis revealed that the northern and forested central areas of Gochang-gun demonstrated relatively high habitat quality, whereas the coastal and agricultural zones exhibited lower values. This indicates that institutional protection measures, such as provincial parks and biosphere reserve designations, are effective in maintaining ecological integrity and habitat value. Conversely, areas with intensive land use show clear signs of habitat degradation [

10].

Second, roads and urban areas were identified as the most influential threat factors affecting habitat quality. Scenario-based threat removal analyses confirmed that eliminating these factors resulted in the greatest reduction in overall sensitivity. Most habitat types also exhibited high levels of vulnerability to these two threats. This finding supports the assertion that urbanization and infrastructure expansion are major pressures on local biodiversity [

4,

21].

Third, habitat-specific variations in quality and sensitivity require different conservation strategies. For example, in core zones with high habitat quality, the focus should be on preserving the current conditions, whereas habitat quality transition zones, characterized by low quality and high sensitivity, require active restoration and management. Tailoring strategies based on zone characteristics can enhance resource allocation efficiency [

22].

Fourth, discrepancies were noted between the assigned threat weights in the InVEST model and actual sensitivity outputs. This highlights the need to reevaluate the ecological validity of model inputs, especially sensitivity matrixes and spatial datasets. Improved accuracy and field-based validation are essential to increase the model’s reliability [

16,

20].

5. Conclusions

This study provides a spatially grounded evaluation of habitat quality in Gochang-gun by combining biotope map data with the InVEST Habitat Quality model. The analysis identified clear spatial disparities, with protected forested regions maintaining high ecological integrity, while urbanized and agricultural zones exhibited notable habitat degradation. Roads and urban land use were found to be the most impactful threats, with their removal significantly improving habitat conditions. These insights underscore the need for threat-specific management strategies and highlight the value of using biotope maps in ecological modeling and spatial planning. Considering that the entire administrative area of Gochang-gun is designated as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, conservation strategies must align with the core, buffer, and transition zone framework. Particularly, transition areas with lower habitat quality require active restoration and nature-based solutions. Overall, this study demonstrates the utility of integrative modeling approaches for ecosystem assessment and offers a practical foundation for enhancing biodiversity conservation at the regional scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D. U.K.; methodology, D. U.K.; software, D. U.K.; validation, D. U.K.; formal analysis, D. U.K.; investigation, D. U.K.; data curation, D. U.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D. U.K.; writing—review and editing, D. U.K. and H. Y. Y.; visualization, H. Y. Y.; supervision, D. U.K.; project administration, D. U.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Data is contained within the article.

Abbreviations

| DT |

Degradation transition zone |

| DB |

Degradation buffer zone |

| DC |

Degradation core zone |

| HT |

Habitat quality transition zone |

| HB |

Habitat quality buffer zone |

| HC |

Habitat quality core zone |

| InVEST |

Integrated valuation of ecosystem services and tradeoffs |

| LULC |

Land use/land cover |

References

- Wang, H.; Tang, L.; Qiu, Q.; Chen, H. Sustainability. In Book Title. A; Author 2, B. Title of the chapter, 2020._Assessing the impacts of urban expansion on habitat quality by combining land use_, landscape, Vol., *!!! REPLACE !!!*, 12, *!!! REPLACE !!!*, 4346Author, 1, Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- You, G.; Chen, T.; Shen, P.; Hu, Y. Designing an Ecological Network in Yichang Central City in China Based on Habitat Quality Assessment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xu, E.; Dong, N.; Tian, G.; Kim, G.; Song, P.; Ge, S.; Liu, S. Driving Mechanism of Habitat Quality at Different Grid-Scales in a Metropolitan City. Forests 2022, 13, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Fang, C.; Liu, H. A comparative analysis of urban habitat quality changes using the InVEST model: The case of Tokyo and Seoul. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1164. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Lu, X.; Xie, Z.; Ma, J.; Zang, J. Study on the Spatiotemporal Evolution of Habitat Quality in Highly Urbanized Areas Based on Bayesian Networks: A Case Study from Shenzhen, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Kim, G. Biotope Map Creation Method and Utilization Plan for Eco-Friendly Urban Development. Land 2024, 13, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Park, C. A study on the effectiveness of nature-based solutions through the biotope area factor. J Environ Impact Assess Koreasci 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H.J.; Kim, C.K.; Lee, H.W.; Lee, W.K. Conservation, Restoration, and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity Based on Habitat Quality Monitoring: A Case Study on Jeju Island, South Korea (1989–2019). Land 2021, 10, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Hu, Y. Spatiotemporal variation and driving factors analysis of habitat quality: A Case study in Harbin, China. Land 2024, 13, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinsch, M.; Groß, J.; Burkhard, B. The influence of model choice and input data on pollinator habitat suitability in the Hannover region. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0305731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.U.; Kim, J.C.; You, C.H.; Oh, W. Occurrences status of biota in Gochang-gun, South Korea. GEODATA 2024, 6, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Ecology. Establishment of Gochang-gun biotope map, 2022. Available online: https://ecolibrary.me.go.kr/nie/#/search/detail/5880399 (accessed on 21 Oct 2023).

- Il, L.K. Lee Sung Joo, Tuvshinjargal Namuun, Lee Eun Sun, Lee Gwan Gyu, Jeon Seong Woo 2020. Study on Heat Vulnerability Assessment Using Biotope Map(A Case Study of Suwon, Korea). Journal of Climate Change Research, 11, 6–1, 629–641.

- Ministry of the Environment. Guidelines for the Development of Biotope Map, 2021.

- Sukopp, H.; Weiler, S. Biotope mapping and nature conservation strategies in urban areas of the Federal Republic of Germany. Landsc Urban Plan 1988, 15, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- María, A.; Sukopp, H.; Weiler, S. Urban forestry & urban greening 2024._Biotope mapping and land use planning: Revisiting the German model in global urban contexts, 83, 127034. 83.

- Sharma, R.; Kushwaha, S.P.S.; Kumar, A. Environmental monitoring and assessment 2018._Assessment of habitat quality and fragmentation using InVEST model for Kanha Tiger Reserve, India, 190, 1–13.

- Mukhopadhyay, A.; Hati, J.P.; Acharyya, R.; Pal, I.; Tuladhar, N.; Habel, M. Global trends in using the InVEST model suite and related research: A systematic review. Ecohydrol Hydrobiol, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veisi Nabikandi, B.; Rastkhadiv, A.; Feizizadeh, B.; Gharibi, S.; Gomes, E. A scenario-based framework for evaluating the effectiveness of nature-based solutions in enhancing habitat quality. GeoJournal 2025, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi Saedi, Z.; Veisi Nabikandi, M.; Mohammadi, A. VEST. Environmental monitoring and assessment. In 2025, 197, 214. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Park, J. Ecological indicators 2024._Integrating biotope maps and ecosystem service models for urban ecological planning in South Korea, 157, 110296.

- Kim, Y.; Kim, H. 2024._A study on the application of urban biotope maps to support local biodiversity strategies in Korea. Journal of Ecology and Environment_, 48, 8. 48.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area, Gochang-gun, in South Korea.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area, Gochang-gun, in South Korea.

Figure 2.

Workflow for habitat quality assessment and extended analysis using the InVEST model.

Figure 2.

Workflow for habitat quality assessment and extended analysis using the InVEST model.

Figure 3.

Spatial patterns of habitat quality and degradation in Gochang-gun. (a) High habitat quality values are concentrated in forested and protected areas. (b) Degradation levels are elevated near roads and agricultural zones.

Figure 3.

Spatial patterns of habitat quality and degradation in Gochang-gun. (a) High habitat quality values are concentrated in forested and protected areas. (b) Degradation levels are elevated near roads and agricultural zones.

Figure 4.

Boxplots of variable distributions in habitat quality and degradation within the core, buffer, and transitional zones of the Gochang Biosphere Reserve.

Figure 4.

Boxplots of variable distributions in habitat quality and degradation within the core, buffer, and transitional zones of the Gochang Biosphere Reserve.

Figure 5.

Frequency distribution of habitat degradation and quality values within the core, buffer, and transitional zones of the Gochang Biosphere Reserve. DT, DB, and DC, degradation transition buffer and core zones, respectively; HT, HB, and HC, habitat quality transition, buffer, and core zones, respectively.

Figure 5.

Frequency distribution of habitat degradation and quality values within the core, buffer, and transitional zones of the Gochang Biosphere Reserve. DT, DB, and DC, degradation transition buffer and core zones, respectively; HT, HB, and HC, habitat quality transition, buffer, and core zones, respectively.

Figure 6.

Correlation between habitat quality and habitat degradation.

Figure 6.

Correlation between habitat quality and habitat degradation.

Figure 7.

The average sensitivity of various habitat types to threat factors.

Figure 7.

The average sensitivity of various habitat types to threat factors.

Figure 8.

Matrix of habitat type sensitivity to individual threat factors.

Figure 8.

Matrix of habitat type sensitivity to individual threat factors.

Figure 9.

Change in the average sensitivity value of various habitat types in response to threat factor removal.

Figure 9.

Change in the average sensitivity value of various habitat types in response to threat factor removal.

Table 1.

Assigned sensitivity values of each habitat type to individual threat factors.

Table 1.

Assigned sensitivity values of each habitat type to individual threat factors.

| Name |

Crops |

Urban |

Grass |

Roads |

Bare |

| Artificial wetland |

0.5 |

0.9 |

0.3 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

| Bare ground |

0.3 |

0.7 |

0.1 |

0.9 |

0.1 |

| Dry field |

0.8 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

| Endangered wildlife habitat |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

0.3 |

| Farm waterway |

0.8 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

| Forest |

0.3 |

0.8 |

0.1 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

| Grassland |

0.2 |

0.9 |

0.0 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

| Mudflats |

0.3 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

| Orchard |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

0.3 |

| Provincial Park |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

| Reservoir |

0.7 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.8 |

0.2 |

| River |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0.1 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

| Salt pond |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0.2 |

0.8 |

0.5 |

| Shrub |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0.2 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

| Wetland |

0.5 |

0.9 |

0.1 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

Table 2.

Attributes of input threat factors applied in the InVEST habitat quality model.

Table 2.

Attributes of input threat factors applied in the InVEST habitat quality model.

| THREAT |

WEIGHT |

MAX_DIST (m) |

DECAY |

| Crops |

0.7 |

8 |

linear |

| Urban |

1.0 |

10 |

exponential |

| Grass |

0.5 |

6 |

linear |

| Roads |

1.0 |

3 |

exponential |

| Bare |

1.0 |

5 |

exponential |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).