Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Respondents

3.2. Dietary Assessment

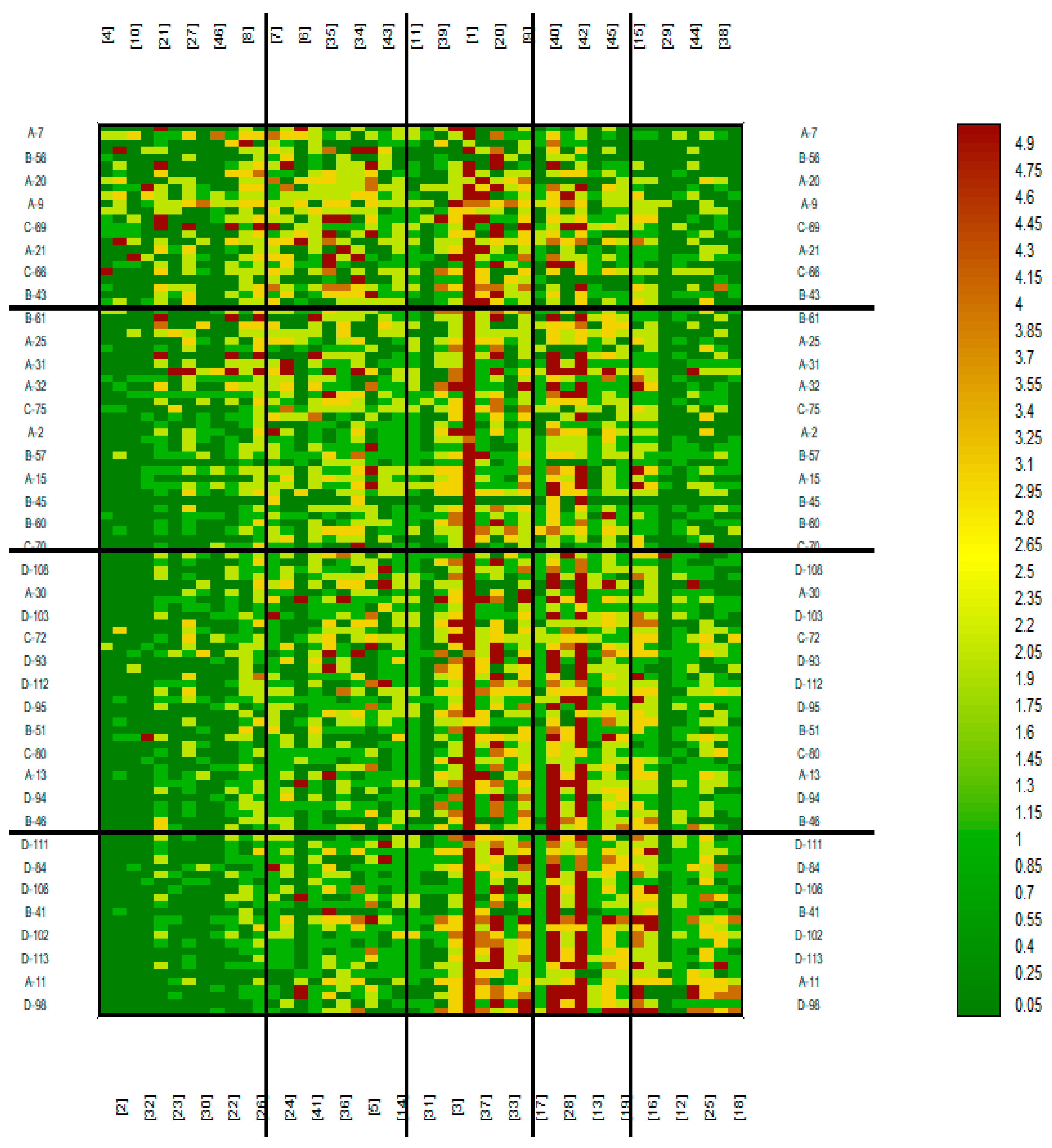

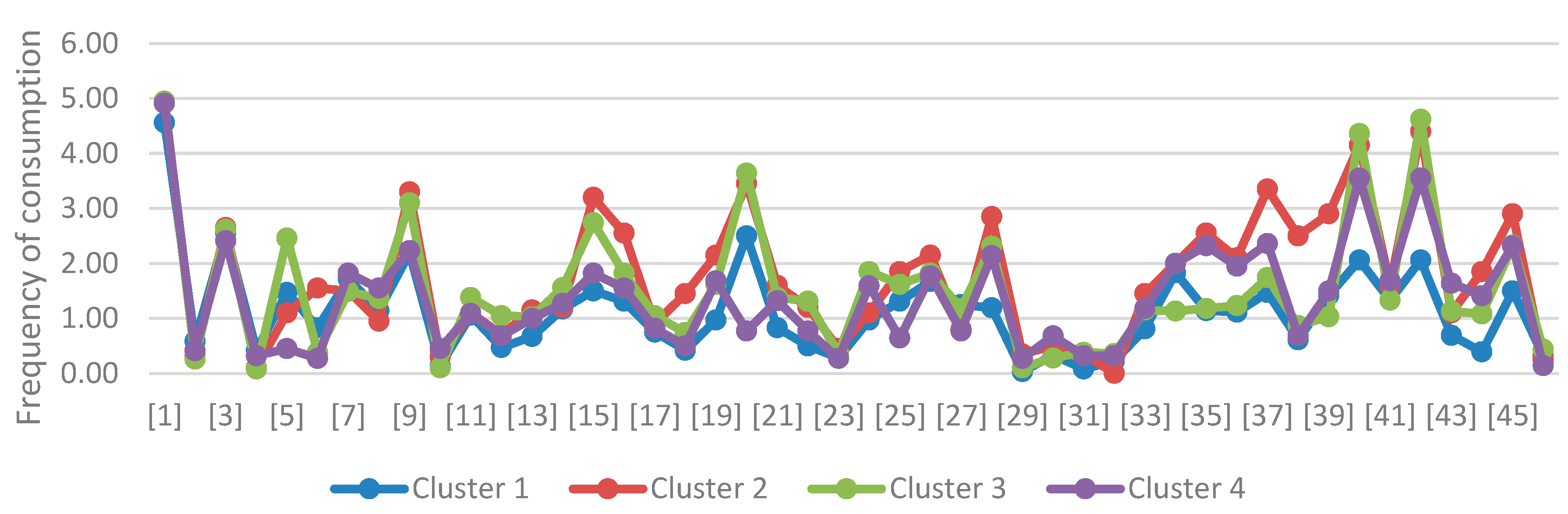

- The first one are those who consumed products from the first four groups relatively frequently and products from group 5 rarely.

- The second one were those who consumed products from group 1 less frequently, still ate products from groups 2, 3 and 4, but still rarely ate products from group 5.

- The third one are those who rarely consumed products from groups 1 and 2, but frequently consumed products from groups 3 and 4, and relatively more often ate products from group 5.

- The fourth one are those who rarely ate products from groups 1 and 2 (especially rarely from group 1), often ate products from groups 3 and 4, and most often of all the clusters ate products from group 5.

- -

- less frequent use of mustard, ketchup, ready-made sauces, seasoning mixes, stock cubes, bread crumbs;

- -

- less frequent consumption of meat, ready-made cold cuts, offal products, cold foods and fish.

3.3. Laboratory Tests

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jonsson, I.M.; Moller, G.L.; Paerregaard, A. Gluten free- diet is for some a neccessity, for others lifestyle. Ugeskr Laeger. 2017, 179, V09160636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rymarczyk, B.; Glück, J.; Rogala, B. Częstość występowania celiakii u chorych z niecharakterystycznymi objawami sugerującymi nadwrażliwość pokarmową. Alerg Astma Immun. 2019, 24, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabó, I.R.; et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012, 54, 136–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.C.; Ciacci, C. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines on celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017, 51, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Jarr, K,; Layton, C.; et al. Therapeutic Implications of Diet in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Related Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 890. [CrossRef]

- Nestle, F.O.; Kaplan, D.H.; Barker, J. Psoriasis . N Engl J Med. 2009, 361, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ständer, S. Atopic Dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 1136–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuberbier, T.; Latiff, A.H.A.; Abuzakouk, M.; et al. The international EAACI/GA²LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2022, 77, 734–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konińska, G.; Marczewska, A.; Sobak-Huzior, P.; Źródlak M. Celiakia i dieta bezglutenowa. Praktyczny poradnik. Efekt s.j.: Warszawa, Poland, 2017, ISBN: 978-83-931335-5-0.

- Majsiak, E.; Choina, M,; Cukrowska, B.; et al. The impact of symptoms on quality of life before and after diagnosis of celiac disease: the results from a Polish population survey and comparison with the results from the United Kingdom. BMC Gastroenerol. 2021, 21, 99.

- Cukrowska, B.; Majsiak, E. Zróżnicowany obraz kliniczny celiakii u dzieci jako przyczyna trudności diagnostycznych. Alergia. 2018, 3, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo, M.; Ferro, A.; Brascugli, I.; et al. Extra-Intestinal Manifestations of Celiac Disease: What Should We Know in 2022? J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jericho, H.; Sansotta, N.; Guandalini, S. Extraintestinal manifestations of celiac disease: effectiveness of the gluten-free diet. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutrition. 2017, 65, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bierła, J.B.; Trojanowska, I.; Konopka, E.; et al. Diagnostyka celiakii i badania przesiewowe w grupach ryzyka. Diagn Lab. 2016, 52, 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan, S.J.; Ahmad, Q.M.; Sultan, S.T. Antigliadin antibodies in psoriasis. Australas J Dermatol. 2010, 51, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, F.; Alizadeh, S.; Amiri, A.; et al. Psoriasis and coeliac disease: is there any relationship? Acta Derm Venereol. 2010, 90, 295–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungprasert, P.; Wijarnpreecha, K.; Kittanamongkolchai, W. Psoriasis and Risk of Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Indian J Dermatol. 2017, 62, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, P.; Mathur, M. ; Association between psoriasis and celiac disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020, 82, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, L.; de Seta, L.; D'Adamo, G.; et al. Atopy and coeliac disease:bias or true relation? Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990, 79, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivert, L.U.; Wahlgren, C.F.; Lindelöf, B.; et al. Association between atopic dermatitis and autoimmune diseases: a population-based case–control study. Br J Dermatol. 2021, 185, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppi, S.; Jokelainen, J.; Timonen, M.; et al. Atopic Dermatitis Is Associated with Dermatitis Herpetiformis and Celiac Disease in Children. J Invest Dermatol. 2021, 141, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varjonena, E,; Vainio, E.; Kalimo, K. Antigliadin IgE – indicator of wheat allergy in atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2008, 55, 386–391.

- Čelakovskáa, J.; Ettlerováb, K.; Ettlera, K.; et al. The Effect of Wheat Allergy on the Course of Atopic Eczema in Patients over 14 Years of Age. Acta Medica. 2011, 54, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Lindelof, B.; Rashtak, S.; et al. Does urticaria risk increase in patients with celiac disease? A large population-based cohort study. Eur J Dermatol. 2013, 23, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confino-Cohen, R.; Chodick, G.; Shalev, V.; et al. Chronic urticaria and autoimmunity: Associations found in a large population study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012, 129, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingomataj, E.C.; Gjata, E.; Bekiri, A.; et al. Gliadin allergy manifested with chronic urticaria, headache and amonorrhea. BMJ Case Rep. 2011, 5, bcr1020114907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, M.; Candelli, M.; Cremonini, F.; et al. Idiopathic chronic urticaria and celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2005, 50, 1702–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, L.; Danesh, M.J.; Lee, K.M.; et al. Dietary Behaviors in Psoriasis: Patient-Reported Outcomes from a U. S. National Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017, 7, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati, A.; Afifi, L.; Danesh, M.J.; et al. Dietary modifications in atopic dermatitis: patient-reported outcomes. JDermatol Treat. 2017, 28, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, I,; Schäfer, C.; Kleine-Tebbe, J.; et al. Non-celiac gluten/wheat sensitivity (NCGS)—a currently undefined disorder without validated diagnostic criteria and of unknown prevalence. Allergo J Int. 2018, 27, 147–151. [CrossRef]

- Catassi, C.; Alaedini, A.; Bojarski, C.; et al. The Overlapping Area of Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS) and Wheat-Sensitive Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): An Update. Nutrients. 2017, 9, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.; Muir, J.G.; Gibson, P.R. Controversies and Recent Developments of the Low-FODMAP Diet. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2017, 13, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, A.R.; Siegel, M,; Bagel, J.; et al. Dietary Recommendations for Adults With Psoriasis or Psoriatic Arthritis From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: A Systematic Review. JAMA dermatol. 2018, 154, 934–950. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidbury, R.; Tom, W.L.; Bergman, J.N.; et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014, 71, 1218–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.; Robins, G.G.; Burley, V.J.; Howdle, P.D. ; Evidence of high sugar intake, and low fibre and mineral intake, in the gluten-free diet. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010, 32, 573–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Diagnosis | |||||||

| Control | AD | Psoriasis | Urticaria | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Famale | 25 | 71,43% | 18 | 69,23% | 20 | 57,14% | 18 | 85,71% |

| Male | 10 | 28,57% | 8 | 30,77% | 15 | 42,86% | 3 | 14,29% |

| chi^2 correlation test | Chi^=5,16, df=3, p=0,1605 | |||||||

| Age | Diagnosis | |||||||

| Control | AD | Psoriasis | Urticaria | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| <18 | 1 | 2,86% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 8,57% | 0 | 0% |

| 18-30 | 6 | 17,14% | 11 | 42,31% | 7 | 20% | 3 | 14,29% |

| 31-40 | 6 | 17,14% | 6 | 23,08% | 11 | 31,43% | 8 | 38,1% |

| 41-50 | 13 | 37,14% | 3 | 11,54% | 2 | 5,71% | 6 | 28,57% |

| >50 | 9 | 25,71% | 6 | 23,08% | 12 | 34,29% | 4 | 19,05% |

| Fisher's exact test | p=0,1199 | |||||||

| Do you suffer from digestive complaints? | Diagnosis | ||||||||

| Control | AD | Psoriasis | Urticaria | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| No | 35 | 100% | 12 | 46,15% | 23 | 65,71% | 18 | 85,71% | |

| Yes | 0 | 0% | 14 | 53,85% | 12 | 34,29% | 3 | 14,29% | |

| chi^2 correlation test | Chi^=2625, df=3, p<0,0001 | ||||||||

| Food Product | Diagnosis | Arithmetic Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Lower Quartile | Upper Quartile |

Kruskal-Wallis Test |

Homogenous Groups | POST-HOC (Dunn Bonferroni) | |||

| Control | AD | Psoriasis | Urticaria | |||||||||||

| Bread with gluten | Control | 4,9 | 5,0 | 0,4 | 3,0 | 5,0 | 5,0 | 5,0 |

H=2,6320 p=0,4519 |

a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 4,8 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 5,0 | 5,0 | a | 1 | 0,9327 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 4,7 | 5,0 | 0,8 | 2,0 | 5,0 | 5,0 | 5,0 | a | 1 | 0,9327 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 5,0 | 5,0 | 0,2 | 4,0 | 5,0 | 5,0 | 5,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Bread without gluten | Control | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,2 | 0,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | H=15,2366 p=0,0016 |

a | 0,9183 | 0,0007 | 0,3383 | |

| AD | 0,2 | 0,0 | 0,5 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | ab | 0,9183 | 0,1943 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,8 | 0,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | b | 0,0007 | 0,1943 | 0,9008 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,5 | 0,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | ab | 0,3383 | 1 | 0,9008 | |||

| Flour with gluten | Control | 2,5 | 3,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 2,0 | 3,0 | H=2,2119 p=0,5296 |

a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 2,4 | 2,0 | 1,4 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 3,8 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 2,5 | 2,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 2,0 | 3,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 2,9 | 3,0 | 1,3 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 2,0 | 4,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Flour without gluten | Control | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | H=15,0883 p=0,0017 |

a | 0,6175 | 0,5118 | 0,0006 | |

| AD | 0,2 | 0,0 | 0,5 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | ab | 0,6175 | 1 | 0,1608 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,2 | 0,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | ab | 0,5118 | 1 | 0,1002 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,7 | 0,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | b | 0,0006 | 0,1608 | 0,1002 | |||

| Flakes with gluten | Control | 1,9 | 2,0 | 1,4 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 3,0 | H=9,7805 p=0,0205 |

b | 0,0336 | 0,2832 | 1 | |

| AD | 1,0 | 0,0 | 1,5 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 1,8 | a | 0,0336 | 1 | 0,1711 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,4 | 1,0 | 1,8 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,5 | ab | 0,2832 | 1 | 0,8849 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,8 | 2,0 | 1,5 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | ab | 1 | 0,1711 | 0,8849 | |||

| Flakes without gluten | Control | 0,8 | 0,0 | 1,8 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | H=3,1238 p=0,3729 |

a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 0,3 | 0,0 | 0,7 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 1 | 0,8968 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,9 | 0,0 | 1,5 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 0,8968 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,6 | 0,0 | 0,8 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Groats with gluten | Control | 1,4 | 1,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 1,0 | H=6,1787 p=0,1032 |

a | 1 | 0,195 | 0,2318 | |

| AD | 1,5 | 1,0 | 0,8 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,7 | 2,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,195 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 2,0 | 1,0 | 1,2 | 1,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 3,0 | a | 0,2318 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Groats without gluten | Control | 0,9 | 1,0 | 0,8 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | H=5,4126 p=0,144 |

a | 0,5708 | 0,1917 | 0,7769 | |

| AD | 1,3 | 1,0 | 0,8 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,5708 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,5 | 2,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,1917 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,3 | 1,0 | 0,7 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,7769 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Pasta with gluten | Control | 3,4 | 3,0 | 1,2 | 1,0 | 5,0 | 3,0 | 4,0 | H=21,3519 p=0,0001 |

b | 0,0001 | 0,0072 | 0,3421 | |

| AD | 2,0 | 2,0 | 0,8 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 2,0 | 2,8 | a | 0,0001 | 0,9383 | 0,2146 | |||

| Psoriasis | 2,5 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 1,0 | 5,0 | 2,0 | 3,0 4,0 |

a | 0,0072 | 0,9383 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 2,8 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 1,0 | 5,0 | 2,0 | ab | 0,3421 | 0,2146 | 1 | ||||

| Pasta without gluten | Control | 0,1 | 0,0 | 0,2 | 0,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | H=3,6768 p=0,2985 |

a | 0,6989 | 1 | 0,6777 | |

| AD | 0,3 | 0,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 0,6989 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,1 | 0,0 | 0,4 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,5 | 0,0 | 1,3 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 0,6777 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Dumplings (Pierogi) | Control | 1,3 | 1,0 | 0,7 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | H=4,2366 p=0,237 |

a | 0,7257 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 1,0 | 1,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 1,0 | a | 0,7257 | 1 | 0,3367 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,1 | 1,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 1,5 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,3 | 1,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 0,3367 | 1 | |||

| Dumplings (Pyzy) | Control | 1,2 | 1,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | H=28,3973 p<0,0001 |

b | 0,0177 | <0,0001 | 0,1206 | |

| AD | 0,7 | 1,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | a | 0,0177 | 0,3325 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,3 | 0,0 | 0,5 | 0,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | a | <0,0001 | 0,3325 | 0,1427 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,8 | 1,0 | 0,7 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | ab | 0,1206 | 1 | 0,1427 | |||

| Dumplings (Kopytka) | Control | 1,2 | 1,0 | 0,5 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | H=20,6354 p=0,0001 |

b | 0,6409 | 0,0001 | 1 | |

| AD | 1,0 | 1,0 | 0,7 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,3 | 1,0 | ab | 0,6409 | 0,0813 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,5 | 1,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | a | 0,0001 | 0,0813 | 0,0278 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,0 | 1,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 1,0 | b | 1 | 1 | 0,0278 | |||

| Pancakes | Control | 1,3 | 1,0 | 0,7 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | H=1,9833 p=0,5759 |

a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 1,2 | 1,0 | 0,7 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,4 | 1,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,3 | 1,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Confectionery | Control | 3,0 | 3,0 | 1,1 | 1,0 | 5,0 | 2,0 | 4,0 | H=14,5824 p=0,0022 |

b | 0,0092 | 0,0134 | 0,0333 | |

| AD | 1,8 | 2,0 | 1,3 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 3,0 | a | 0,0092 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 2,0 | 2,0 | 1,3 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 3,0 | a | 0,0134 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 2,0 | 1,0 | 1,5 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 3,0 | a | 0,0333 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Cakes |

Control | 2,3 | 2,0 | 1,3 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 2,0 | 2,5 | H=11,17 p=0,0108 |

b | 0,0262 | 0,0533 | 0,1048 | |

| AD | 1,4 | 1,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,0262 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,5 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | ab | 0,0533 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,6 | 1,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | ab | 0,1048 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Pizza | Control | 1,0 | 1,0 | 0,2 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 1,0 | H=4,8097 p=0,1863 |

a | 0,1733 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 0,7 | 1,0 | 0,5 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | a | 0,1733 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,9 | 1,0 | 0,8 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,9 | 1,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 1,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Hamburger buns/hotdogs/sausage rolls | Control | 1,1 | 1,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 0,5 | 1,0 | H=10,5797 p=0,0142 |

b | 0,8958 | 0,0076 | 0,4619 | |

| AD | 0,7 | 1,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | ab | 0,8958 | 0,7516 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,4 | 0,0 | 0,7 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | a | 0,0076 | 0,7516 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,6 | 1,0 | 0,7 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | ab | 0,4619 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Food Product | Diagnosis | Arithmetic Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Lower Quartile | Upper Quartile |

Kruskal-Wallis Test |

Homogenous Groups | POST-HOC (Dunn Bonferroni) | |||

| Control | AD | Psoriasis | Urticaria | |||||||||||

| Milk | Control | 3,6 | 4,0 | 1,3 | 1,0 | 5,0 | 3,0 | 5,0 | H=12,7773 p=0,0051 |

b | 0,107 | 0,0032 | 0,7123 | |

| AD | 2,4 | 2,0 | 2,2 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 5,0 | ab | 0,107 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 2,1 | 2,0 | 1,6 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,5 | 3,0 | a | 0,0032 | 1 | 0,8996 | |||

| Urticaria | 2,8 | 4,0 | 1,8 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 4,0 | ab | 0,7123 | 1 | 0,8996 | |||

| Kefir (kind of buttermilk) |

Control | 1,0 | 1,0 | 0,9 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | H=3,2058 p=0,361 |

a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 1,0 | 0,0 | 1,3 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 0,5065 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,5 | 1,0 | 1,5 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 0,5065 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,4 | 1,0 | 1,5 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 1,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Buttermilk |

Control | 1,0 | 1,0 | 0,8 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | H=1,8665 p=0,6006 |

a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 1,0 | 0,0 | 1,5 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 1,8 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,9 | 1,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 1,5 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,9 | 1,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Flavoured kefir | Control | 0,3 | 0,0 | 0,5 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 0,5 | H=0,2531 p=0,9686 |

a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 0,4 | 0,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,3 | 0,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,3 | 0,0 | 0,8 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yoghurt | Control | 1,3 | 1,0 | 0,9 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | H=0,8434 p=0,8391 |

a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 1,5 | 1,5 | 1,3 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,5 | 1,0 | 1,5 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,2 | 1,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Flavoured yoghurt | Control | 2,0 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 1,0 | 3,0 | H=17,8345 p=0,0005 |

b | 0,0003 | 0,0197 | 0,1875 | |

| AD | 0,8 | 0,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | a | 0,0003 | 1 | 0,7444 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,2 | 1,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,0197 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,4 | 2,0 | 1,4 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | ab | 0,1875 | 0,7444 | 1 | |||

| Cottage cheese (twaróg) | Control | 1,5 | 1,0 | 0,7 | 1,0 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | H=15,9367 p=0,0012 |

a | 1 | 0,2151 | 0,0011 | |

| AD | 1,6 | 2,0 | 1,6 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 0,9932 | 0,0147 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,9 | 2,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,5 | 3,0 | ab | 0,2151 | 0,9932 | 0,3289 | |||

| Urticaria | 2,5 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 2,0 | 3,0 | b | 0,0011 | 0,0147 | 0,3289 | |||

| Cottage cheese (twarożki) | Control | 0,4 | 0,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | H=18,4001 p=0,0004 |

a | 0,3163 | 0,0041 | 0,0008 | |

| AD | 1,0 | 1,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | ab | 0,3163 | 1 | 0,3564 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,3 | 2,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | b | 0,0041 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,7 | 2,0 | 1,4 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 3,0 | b | 0,0008 | 0,3564 | 1 | |||

| Yellow cheese | Control | 2,3 | 2,0 | 1,3 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 2,0 | 3,0 | H=7,0665 p=0,0698 |

a | 1 | 1 | 0,055 | |

| AD | 2,2 | 2,0 | 1,8 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,3 | 3,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 0,3477 | |||

| Psoriasis | 2,1 | 2,0 | 1,5 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 3,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 0,3057 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,3 | 1,0 | 1,4 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,055 | 0,3477 | 0,3057 | |||

| Cheese-based products | Control | 0,1 | 0,0 | 0,2 | 0,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | H=2,4358 p=0,487 |

a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 0,3 | 0,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,2 | 0,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,2 | 0,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Processed cheese | Control | 0,1 | 0,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | H=15,2738 p=0,0016 |

a | 0,0217 | 0,0023 | 1 | |

| AD | 0,5 | 0,0 | 0,7 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | b | 0,0217 | 1 | 0,8422 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,7 | 0,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | b | 0,0023 | 1 | 0,3376 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,2 | 0,0 | 0,4 | 0,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | ab | 1 | 0,8422 | 0,3376 | |||

| Milk products containing cereals | Control | 0,3 | 0,0 | 0,5 | 0,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | H=4,0427 p=0,2569 |

a | 0,2827 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 0,1 | 0,0 | 0,3 | 0,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 0,2827 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,3 | 0,0 | 0,7 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,3 | 0,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Food Product | Diagnosis | Arithmetic Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Lower Quartile | Upper Quartile |

Kruskal-Wallis Test |

Homogenous Groups | POST-HOC (Dunn Bonferroni) | |||

| Control | AD | Psoriasis | Urticaria | |||||||||||

| Meat | Control | 4,7 | 5,0 | 0,6 | 3,0 | 5,0 | 5,0 | 5,0 |

H=46,9575 p<0,0001 |

b | 0,0006 | <0,0001 | <0,0001 | |

| AD | 3,3 | 3,0 | 1,3 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 3,0 | 5,0 | a | 0,0006 | 1 | 0,0903 | |||

| Psoriasis | 3,0 | 3,0 | 1,5 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 2,0 | 4,0 | a | <0,0001 | 1 | 0,4892 | |||

| Urticaria | 2,3 | 2,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 2,0 | 3,0 | a | <0,0001 | 0,0903 | 0,4892 | |||

| Fish | Control | 1,2 | 1,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 1,5 | H=3,7966 p=0,2843 |

a | 0,8226 | 0,4334 | 1 | |

| AD | 1,6 | 1,5 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,8226 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,6 | 2,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,4334 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,4 | 2,0 | 0,7 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Ready-made sliced meats | Control | 4,7 | 5,0 | 0,6 | 3,0 | 5,0 | 5,0 | 5,0 | H=29,4656 p<0,0001 |

b | 0,0723 | <0,0001 | <0,0001 | |

| AD | 3,7 | 4,5 | 1,5 | 1,0 | 5,0 | 3,0 | 5,0 | ab | 0,0723 | 0,6319 | 0,1652 | |||

| Psoriasis | 3,0 | 3,0 | 1,8 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 2,0 | 5,0 | a | <0,0001 | 0,6319 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 2,7 | 3,0 | 1,6 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 2,0 | 3,0 | a | <0,0001 | 0,1652 | 1 | |||

| Offal products | Control | 1,2 | 1,0 | 1,6 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | H=0,7377 p=0,8643 |

a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 1,1 | 1,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 1,8 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,1 | 1,0 | 0,9 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,0 | 1,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Delicatessen products | Control | 1,5 | 1,0 | 1,3 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 1,0 | H=10,0727 p=0,0180 |

a | 0,0517 | 0,1937 | 0,0558 | |

| AD | 0,9 | 1,0 | 1,4 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | a | 0,0517 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,9 | 1,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,1937 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,7 | 0,0 | 0,8 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | a | 0,0558 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Coating with gluten flour | Control | 2,7 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 1,0 | 5,0 | 2,0 | 3,0 | H=16,3096 p=0,0010 |

b | 0,4763 | 0,0027 | 0,0059 | |

| AD | 2,3 | 2,0 | 1,6 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,3 | 3,0 | ab | 0,4763 | 0,8247 | 0,7261 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,8 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,0027 | 0,8247 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,7 | 2,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,0059 | 0,7261 | 1 | |||

| Coating with gluten-free flour | Control | 0,3 | 0,0 | 0,5 | 0,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | H=3,3199 p=0,3449 |

a | 1,3873 | 0,9049 | 0,3594 | |

| AD | 0,2 | 0,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 1,3873 | 0,5519 | 1,5624 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,3 | 0,0 | 0,6 | 0,0 | 2,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | a | 0,9049 | 0,5519 | 1,1431 | |||

| Urticaria | 0,6 | 0,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | a | 0,3594 | 1,5624 | 1,1431 | |||

| Food Product | Diagnosis | Arithmetic Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Lower Quartile | Upper Quartile |

Kruskal-Wallis Test |

Homogenous Groups | POST-HOC (Dunn Bonferroni) | |||

| Control | AD | Psoriasis | Urticaria | |||||||||||

| Mixtures of spices | Control | 1,2 | 1,0 | 1,3 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 |

H=4,9147 p=0,1782 |

a | 1 | 1 | 0,1924 | |

| AD | 1,8 | 1,5 | 1,8 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 3,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,6 | 1,0 | 1,6 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 3,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 2,1 | 2,0 | 1,6 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 3,0 | a | 0,1924 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Mustard |

Control | 1,4 | 1,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | H=3,163 p=0,3672 |

a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 1,3 | 1,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 0,9357 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,7 | 2,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 0,9357 | 0,8353 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,4 | 1,0 | 1,3 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 1 | 0,8353 | |||

| Ketchup | Control | 2,2 | 2,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 3,0 | H=3,2578 p=0,3536 |

a | 1 | 1 | 0,9957 | |

| AD | 1,8 | 2,0 | 1,4 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 2,8 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 2,3 | 2,0 | 1,7 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 3,5 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,7 | 2,0 | 1,3 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,9957 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Ready-made sauces | Control | 1,4 | 1,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | H=6,9643 p=0,073 |

a | 0,1292 | 0,1735 | 0,7776 | |

| AD | 0,8 | 0,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 0,1292 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Psoriasis | 0,8 | 1,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 3,0 | 0,0 | 1,5 | a | 0,1735 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 1,0 | 1,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 0,0 | 1,0 | a | 0,7776 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Broth cubes | Control | 1,5 | 1,0 | 1,5 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | H=7,0401 p=0,0706 |

a | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AD | 1,1 | 1,0 | 1,2 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 0,0 | 2,0 | a | 1 | 0,1375 | 0,1751 | |||

| Psoriasis | 1,7 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 0,0 | 4,0 | 1,0 | 2,5 | a | 1 | 0,1375 | 1 | |||

| Urticaria | 2,0 | 2,0 | 1,5 | 0,0 | 5,0 | 1,0 | 3,0 | a | 1 | 0,1751 | 1 | |||

| Food products | Study groups |

| 1 - Bread with gluten 2 - Bread without gluten 3 - Flour with gluten 4 - Flour without gluten 5 - Flakes with gluten 6 - Flakes without gluten 7 - Groats with gluten 8 - Groats without gluten 9 - Pasta with gluten 10 - Pasta without gluten 11 - Dumplings 12 - Dumplings 13 - Dumplings 14 - Pancakes 15 - Confectionery 16 - Cakes 17 - Pizza 18 - Hamburger buns/hotdogs/sausage rolls 19 - Breadcrumbs 20 - Milk 21 - Kefir (kind of buttermilk) 22 - Buttermilk 23 - Flavoured kefir 24 - Yoghurt 25 - Flavoured yoghurt 26 - Cottage cheese 27 - Cottage cheese 28 - Yellow cheese 29 - Cheese-based products 30 - Processed cheese 31 - Milk products containing cereals 32 - Cereal coffee 33 - Beer 34 - Ready-made condiments 35 - Mixtures of spices 36 - Mustard 37 - Ketchup 38 - Ready-made sauces 39 - Broth cubes 40 - Meat 41 - Fish 42 - Ready-made sliced meats 43 - Offal products 44 - Cold foods (Delicatessen products) 45 - Coating with gluten flour 46 - Coating with gluten-free flour |

A - Psoriasis B - AD C - Urticaria D - Control |

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Clusters 5 |

| 4 - Flour without gluten 2 - Bread without gluten 10 - Pasta without gluten 32 - Cereal coffee 21 - Kefir (kind of buttermilk) 23 - Flavoured kefir 30 - Processed cheese 27 - Cottage cheese (twarożki) 22 - Buttermilk 46 - Coating with gluten-free flour 26 - Cottage cheese (twarogi) 8 - Groats without gluten |

7 - Groats with gluten 24 - Yoghurt 6 - Flakes without gluten 41 - Fish 34 - Ready-made condiments 35 - Mixtures of spices 36 - Mustard 5 - Flakes with gluten 43 - Offal products 14 - Pancakes |

11 – Dumplings (pierogi) 31 - Milk products containing cereals 39 - Broth cubes 3 - Flour with gluten 1 - Bread with gluten 37 - Ketchup 20 – Milk 33 - Beer 9 - Pasta with gluten |

17 - Pizza 40 - Meat 28 - Yellow cheese 42 - Ready-made sliced meats 13 – Dumplings (kopytka) 45 - Coating with gluten flour 19 -Breadcrumbs |

15 - Confectionery 16 - Cakes 29 - Cheese-based products 12 - Dumplings (pyzy) 44 - Cold foods (Delicatessen products) 25 - Flavoured yoghurt 38 - Ready-made sauces 18 - Hamburger buns/hotdogs/sausage rolls |

| Diagnosis | GRAD clustering | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Size | A - Psoriasis | 13 | 15 | 5 | 2 |

| B - AD | 4 | 9 | 10 | 3 | |

| C - Urticaria | 7 | 8 | 6 | 0 | |

| D - Control | 0 | 0 | 16 | 19 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| verse % | A - Psoriasis | 37,14% | 42,86% | 14,29% | 5,71% |

| B - AD | 15,38% | 34,62% | 38,46% | 11,54% | |

| C - Urticaria | 33,33% | 38,1% | 28,57% | 0% | |

| D - Control | 0% | 0% | 45,71% | 54,29% | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| column % | A - Psoriasis | 54,17% | 46,88% | 13,51% | 8,33% |

| B - AD | 16,67% | 28,13% | 27,03% | 12,5% | |

| C - Urticaria | 29,17% | 25% | 16,22% | 0% | |

| D - Control | 0% | 0% | 43,24% | 79,17% | |

| Produkt | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | ANOVA (p) | ||||

| X | sd | x | sd | X | sd | x | sd | ||

| [1] | 4,56 | 1,13 | 4,95 | 0,22 | 4,95 | 0,22 | 4,91 | 0,43 | 0,0499 |

| [2] | 0,58 | 1,18 | 0,30 | 1,13 | 0,26 | 0,55 | 0,41 | 0,80 | 0,4683 |

| [3] | 2,56 | 1,50 | 2,65 | 0,81 | 2,62 | 1,23 | 2,41 | 1,05 | 0,9157 |

| [4] | 0,42 | 0,69 | 0,10 | 0,31 | 0,08 | 0,35 | 0,32 | 1,13 | 0,1161 |

| [5] | 1,47 | 1,48 | 1,10 | 1,33 | 2,46 | 1,67 | 0,45 | 0,91 | <0,0001 |

| [6] | 0,83 | 1,21 | 1,55 | 2,19 | 0,38 | 0,99 | 0,27 | 0,63 | 0,0044 |

| [7] | 1,72 | 1,19 | 1,50 | 1,36 | 1,49 | 1,00 | 1,82 | 0,73 | 0,5996 |

| [8] | 1,14 | 1,02 | 0,95 | 0,89 | 1,36 | 0,81 | 1,55 | 1,01 | 0,1545 |

| [9] | 2,19 | 0,98 | 3,30 | 0,98 | 3,10 | 1,27 | 2,23 | 0,81 | 0,0001 |

| [10] | 0,14 | 0,54 | 0,30 | 0,66 | 0,10 | 0,31 | 0,45 | 1,18 | 0,2079 |

| [11] | 1,06 | 0,58 | 1,10 | 0,64 | 1,38 | 0,59 | 1,09 | 0,61 | 0,0806 |

| [12] | 0,47 | 0,56 | 0,70 | 0,66 | 1,05 | 0,69 | 0,68 | 0,65 | 0,0018 |

| [13] | 0,67 | 0,59 | 1,15 | 0,59 | 1,03 | 0,71 | 1,00 | 0,62 | 0,0245 |

| [14] | 1,17 | 0,61 | 1,20 | 0,70 | 1,56 | 0,68 | 1,27 | 0,63 | 0,0466 |

| [15] | 1,50 | 1,11 | 3,20 | 1,28 | 2,74 | 1,33 | 1,82 | 1,10 | <0,0001 |

| [16] | 1,31 | 0,86 | 2,55 | 1,54 | 1,82 | 0,94 | 1,55 | 1,14 | 0,0008 |

| [17] | 0,75 | 0,65 | 0,90 | 0,64 | 1,05 | 0,39 | 0,82 | 0,73 | 0,1627 |

| [18] | 0,42 | 0,50 | 1,45 | 1,43 | 0,74 | 0,68 | 0,50 | 0,67 | 0,0001 |

| [19] | 0,97 | 0,70 | 2,15 | 1,09 | 1,62 | 0,85 | 1,68 | 0,84 | <0,0001 |

| [20] | 2,50 | 1,63 | 3,45 | 1,67 | 3,64 | 1,37 | 0,77 | 1,11 | <0,0001 |

| [21] | 0,83 | 1,06 | 1,60 | 1,67 | 1,38 | 1,21 | 1,32 | 1,32 | 0,1262 |

| [22] | 0,50 | 0,77 | 1,20 | 1,54 | 1,31 | 1,20 | 0,77 | 0,97 | 0,012 |

| [23] | 0,28 | 0,70 | 0,45 | 0,69 | 0,36 | 0,90 | 0,27 | 0,70 | 0,8446 |

| [24] | 0,97 | 1,13 | 1,10 | 1,12 | 1,85 | 1,20 | 1,59 | 1,33 | 0,01 |

| [25] | 1,31 | 1,35 | 1,85 | 1,27 | 1,62 | 1,11 | 0,64 | 0,85 | 0,0047 |

| [26] | 1,67 | 1,17 | 2,15 | 1,27 | 1,82 | 1,12 | 1,77 | 1,15 | 0,524 |

| [27] | 1,25 | 1,16 | 0,80 | 1,01 | 1,18 | 1,37 | 0,77 | 0,92 | 0,3071 |

| [28] | 1,19 | 1,06 | 2,85 | 1,69 | 2,31 | 1,34 | 2,14 | 1,70 | 0,0002 |

| [29] | 0,03 | 0,17 | 0,35 | 0,81 | 0,10 | 0,38 | 0,27 | 1,08 | 0,213 |

| [30] | 0,33 | 0,48 | 0,50 | 0,95 | 0,28 | 0,76 | 0,68 | 0,89 | 0,203 |

| [31] | 0,08 | 0,28 | 0,35 | 0,59 | 0,38 | 0,67 | 0,32 | 0,57 | 0,0921 |

| [32] | 0,22 | 0,48 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,36 | 1,14 | 0,32 | 0,78 | NA |

| [33] | 0,81 | 0,98 | 1,45 | 1,10 | 1,15 | 0,87 | 1,18 | 1,18 | 0,1318 |

| [34] | 1,83 | 1,32 | 2,00 | 1,41 | 1,13 | 1,26 | 2,00 | 1,38 | 0,0259 |

| [35] | 1,14 | 1,27 | 2,55 | 1,57 | 1,18 | 1,35 | 2,32 | 1,81 | 0,0003 |

| [36] | 1,11 | 1,06 | 2,10 | 1,45 | 1,23 | 0,78 | 1,95 | 1,09 | 0,0009 |

| [37] | 1,47 | 1,44 | 3,35 | 1,14 | 1,74 | 1,07 | 2,36 | 1,33 | <0,0001 |

| [38] | 0,61 | 0,87 | 2,50 | 1,19 | 0,87 | 0,86 | 0,68 | 0,78 | <0,0001 |

| [39] | 1,42 | 1,11 | 2,90 | 1,21 | 1,03 | 1,11 | 1,50 | 1,34 | <0,0001 |

| [40] | 2,06 | 1,17 | 4,15 | 1,14 | 4,36 | 0,99 | 3,55 | 1,10 | <0,0001 |

| [41] | 1,33 | 0,99 | 1,60 | 1,31 | 1,33 | 0,70 | 1,68 | 0,65 | 0,3695 |

| [42] | 2,06 | 1,60 | 4,40 | 0,88 | 4,62 | 0,78 | 3,55 | 1,22 | <0,0001 |

| [43] | 0,69 | 0,89 | 1,10 | 0,64 | 1,13 | 1,51 | 1,64 | 1,09 | 0,028 |

| [44] | 0,39 | 0,73 | 1,85 | 1,63 | 1,08 | 0,81 | 1,41 | 1,22 | <0,0001 |

| [45] | 1,50 | 1,25 | 2,90 | 1,17 | 2,33 | 1,08 | 2,32 | 0,95 | 0,0001 |

| [46] | 0,31 | 0,79 | 0,25 | 0,44 | 0,44 | 0,79 | 0,14 | 0,47 | 0,4182 |

| Diagnosis | GRAD clustering | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Size | A - Psoriasis | 15 | 6 | 6 | 8 |

| B - AD | 8 | 2 | 6 | 10 | |

| C - Urticaria | 13 | 2 | 4 | 2 | |

| D - Control | 0 | 10 | 23 | 2 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| verse % | A - Psoriasis | 42,86% | 17,14% | 17,14% | 22,86% |

| B - AD | 30,77% | 7,69% | 23,08% | 38,46% | |

| C - Urticaria | 61,9% | 9,52% | 19,05% | 9,52% | |

| D - Control | 0% | 28,57% | 65,71% | 5,71% | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| column % | A - Psoriasis | 41,67% | 30% | 15,38% | 36,36% |

| B - AD | 22,22% | 10% | 15,38% | 45,45% | |

| C - Urticaria | 36,11% | 10% | 10,26% | 9,09% | |

| D - Control | 0% | 50% | 58,97% | 9,09% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).