1. Introduction

The global shift toward renewable energy resources has accelerated due to the challenges posed by global warming, the depletion of fossil fuels, and the increasing demand for sustainable energy solutions. Renewable generators such as PhotoVoltaic (PV) systems, thermoelectric generators, and wind turbines offer promising alternatives to conventional energy sources. However, the inherent variability of these systems, driven by fluctuating environmental factors, presents significant challenges in achieving efficient energy utilisation. One effective way to address these challenges is through Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) techniques, which aim to maximise energy extraction under varying operating conditions.

Among the most widely used MPPT methods are the Perturb and Observe (P&O) and Incremental Conductance (INC) techniques [

1]. These methods are valued for their simplicity and ease of implementation, but they suffer from critical drawbacks. Specifically, P&O methods introduce steady-state oscillations around the maximum power point (MPP) and struggle to adapt to rapid environmental changes. Moreover, although these methods incorporate feedback mechanisms, they are not classified as model-based controllers from a control theory perspective. Consequently, their effectiveness diminishes in complex and dynamic operating scenarios where more robust and adaptive solutions are required [

2].

Several advanced MPPT techniques have been proposed to enhance the efficiency and response time of PV systems. One such approach is the use of Fuzzy Logic Control (FLC) and Model Predictive Control (MPC), as analysed in [

3]. While FLC demonstrates superior adaptability to dynamic irradiance changes, achieving an average MPPT efficiency of 98.298%, it still relies on heuristic rule-based decision-making, which can be challenging to tune optimally for varying operating conditions. Additionally, FLC methods often exhibit steady-state oscillations around the MPP due to their lack of a precise convergence criterion. On the other hand, MPC provides predictive capabilities but requires a high computational burden, leading to slower response times compared to FLC. Moreover, MPC depends on accurate system modelling, making it less robust against parameter uncertainties.

Artificial intelligence-based MPPT methods proposed in [

4] offer predictive capabilities by forecasting irradiance variations and estimating the MPP voltage through a feedforward neural network. While this approach demonstrates superior tracking performance across different weather conditions, its reliance on historical irradiance data makes it susceptible to prediction errors in rapidly fluctuating environments. Furthermore, neural network-based MPPT methods often require extensive training datasets and computationally intensive real-time implementation, limiting their feasibility in embedded system applications.

Metaheuristic optimization algorithms, such as the improved Hunter–Prey Optimisation (IHPO) technique proposed in [

5], have also been explored for MPPT applications. These algorithms aim to overcome local optima challenges in multi-peaked power-voltage characteristics under shading conditions. While IHPO achieves high efficiency (98.75%) and global tracking capabilities, it requires iterative searches, leading to longer convergence times compared to direct model-based approaches. Additionally, its dependence on population-based optimisation can introduce transient tracking delays and increased computational overhead, making it less suitable for real-time MPPT applications in rapidly changing environments.

Model-based controllers offer a promising alternative for MPPT by leveraging a mathematical representation of the system to improve accuracy and adaptability [

6]. Linear Proportional-Integral (PI) controllers, for example, have been extensively used for voltage or current control in renewable energy systems [

7]. Their simplicity and cost-effectiveness make them a popular choice. However, PI controllers are often inadequate for wide operational ranges as they exhibit slow transient responses and sensitivity to environmental disturbances. To overcome these limitations, advanced control methods have been introduced.

Fuzzy logic controllers have shown potential in handling system uncertainties and nonlinearities, particularly in renewable energy applications [

8]. Despite their advantages, these controllers increase computational complexity and implementation costs. Similarly, hybrid systems incorporating machine learning techniques [

9] enhance the adaptability of MPPT controllers but require extensive training data and computational resources, making them less practical for real-time applications. Sliding mode controllers [

10], known for their robustness against parameter variations and external disturbances, offer another advanced solution, yet they are hindered by chattering effects that can compromise system reliability [

11]. From the perspective of the Maximum Power Transfer (MPT) theorem in electric circuit analysis, MPPT can be conceptualised as an Input Impedance Control (I

2C) problem. According to the MPT theorem, maximum power transfer occurs when the equivalent input impedance of the load matches the internal impedance of the source. This insight provides the foundation for a novel I

2C-based approach to MPPT, which shifts the focus from conventional voltage or current control strategies to impedance matching. By aligning the converter’s input impedance with the source’s internal impedance, the I

2C approach ensures enhanced performance in energy extraction.

In this design framework, the definition of input impedance introduces significant challenges. The input current, a state variable in the system, appears in the denominator of the impedance equation, and the system is inherently nonlinear as a result. Furthermore, model parameters such as internal resistance and open-circuit voltage are highly dependent on the operating point, particularly in PV generators. These dependencies result in parameter uncertainties that must be addressed to ensure reliable operation.

To address the challenges posed by the inherent nonlinearity of the system, this paper first introduces an innovative method to linearise the system and model it as a first-order transfer function, referred to as the I2C model. While this linearised model is effective under certain conditions, its validity diminishes over a wide range of operating changes and in the presence of significant model uncertainties. To overcome these limitations, an adaptive Lyapunov-based nonlinear controller is proposed. This controller is designed to estimate and compensate for parameter uncertainties, ensuring robustness and superior performance across a wide range of operating conditions. By leveraging the Lyapunov stability theory, the adaptive controller offers a fast dynamic response, enhanced stability, and resilience to environmental variations, making it a promising solution for addressing the complexities of nonlinear renewable energy systems.

In summary, this paper presents a groundbreaking MPPT approach, termed the Input Impedance Control (I2C) strategy. By introducing a paradigm shift from traditional voltage or current control methods to impedance matching, the proposed I2C method directly addresses the limitations of existing techniques. A detailed comparison of the developed controllers demonstrates the significant advantages of the adaptive nonlinear controller in terms of robustness, dynamic response, and performance under varying conditions. Comprehensive MATLAB simulations further validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach, showcasing its ability to enhance the efficiency and stability of renewable energy systems. This contribution not only advances the state of the art in MPPT but also establishes a novel framework for sustainable energy optimisation.

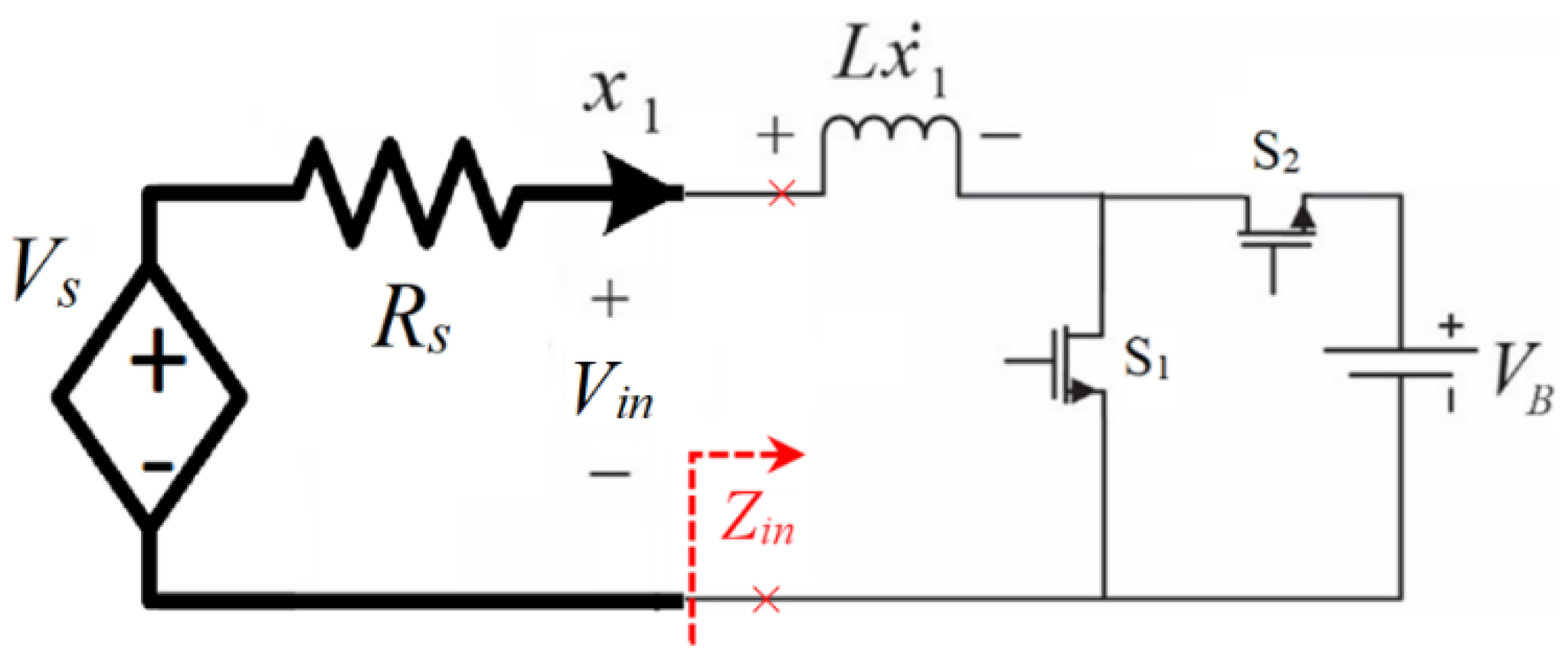

3. System Modelling and I2C-MPPT Design

In this section, the system modelling and I2C-MPPT closed-loop controller design for renewable generators is presented. Considering the proposed approach, the equivalent input impedance of the converter is controlled to match the equivalent internal impedance of the renewable generator. Consequently, the renewable generator can be represented using the Thevenin equivalent circuit, consisting of a voltage source in series with a resistor. Notably, their values depend on the operating point and characteristics of the renewable generator. For example, in thermoelectric generators and piezoelectric generators, the open-circuit voltage and internal resistance remain approximately constant across a wide range of operation. However, for PV generators, these values are highly dependent on the operating point. At a specific operating point, the PV generator can still be modelled using the same approach. From a controller design perspective, the values of open-circuit voltage and internal resistance are uncertain. Hence, modelling the input voltage source as a Thevenin circuit is an acceptable assumption if the model parameters are treated as uncertain values.

3.1. System Modelling

The system model assumes that the converter operates at a sufficiently high switching frequency to ensure Continuous Conduction Mode (CCM). Notably, Discontinuous Conduction Mode (DCM), the input current ripple becomes significant, causing the operating point of the renewable generator to fluctuate widely around the MPP during steady-state operation. This fluctuation adversely affects system performance. Consequently, CCM operation is preferred for MPPT applications. Considering the switching states of the converter in CCM:

- (1)

Switching State 1 (S1: ON, S2: OFF):

In this state, the load (battery) is disconnected from the input source. Assuming the inductor current as the state variable and ideal switch operation (short circuit when ON and open circuit when OFF), the time derivative of the state variable can be expressed as:

- (2)

Switching State 2 (S1: OFF, S2: ON):

In this state, the energy stored in the inductor during the previous mode is transferred to the load battery. The time derivative of the state variable in this mode is given by:

By combining these two equations and applying an averaged state-space model, the system dynamics can be expressed as:

where

represents the duty cycle. This modelling approach provides a foundation for analysing and designing the control systems.

3.2. Model Linearisation and PI Control

From the perspective of controller design, the input variable is defined as

, and the output is defined as

. Consequently, the system transfer function is expressed as

. Considering the system nonlinearity and to analyse it in small signal terms, small perturbations around the steady-state values are introduced:

where

,

, and

are steady-state values and

,

, and

are small-signal variables.

Substituting (10) and (11) into the original state-space equation in (9):

Separating the DC and ac terms in (11), and assuming

, as the time derivative of DC component is zero:

Hence, the first term of the transfer function,

can be expressed in Laplace domain as:

Replacing (10), (12), and (16) into

:

The equation (19) can be written as:

Assuming

, the DC and ac components can be separated in (21) as follows:

Using (25), the second term of the transfer function,

,can be written as:

The system transfer function can be determined using (18) and (26) as follows:

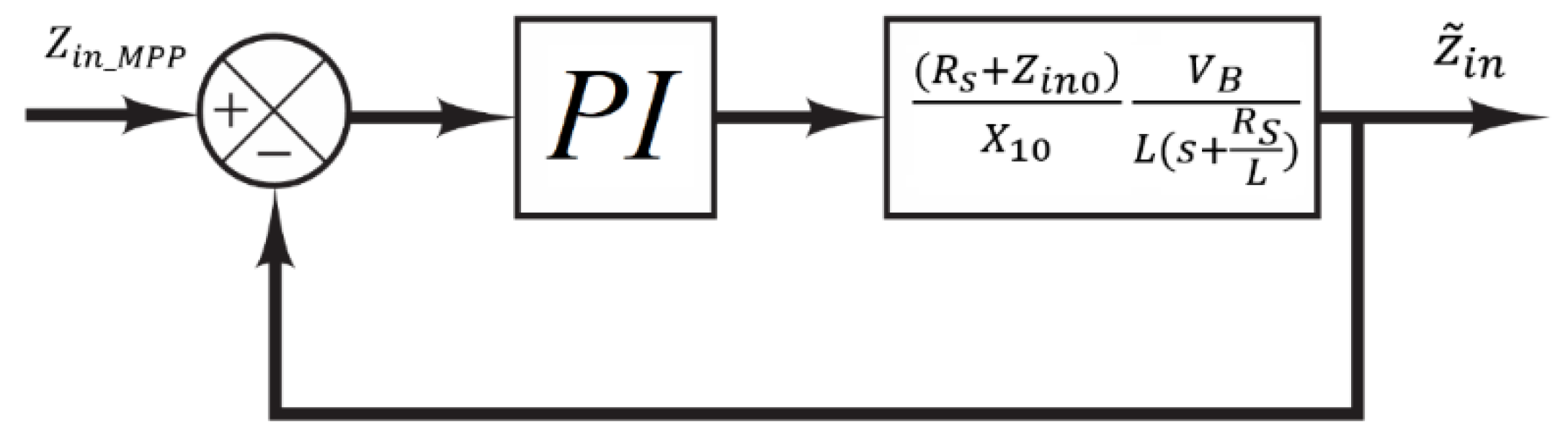

Based on (27), it is shown that the I

2C-MPPT system can be approximated using a first order transfer function. The closed-loop block diagram of linear PI controller used to implement the I2C-MPPT system is illustrated in

Figure 5.

3.3. Lyapunov Based Adaptive Nonlinear I2C-MPPT Design

Considering the equation used for modeling the input impedance,

, the I

2C-MPPT system exhibits nonlinear behavior. As a result, the linear controller depicted in

Figure 5 is unable to guarantee the stability and robustness of the closed-loop system under significant variations in

,

, and

. To address this limitation, this paper proposes a novel adaptive nonlinear controller. In the proposed design, all system parameters are treated as uncertain, and adaptive rules are derived based on the Lyapunov stability criteria to estimate and compensate for the variations in these uncertain parameters effectively.

To design the adaptive nonlinear controller, the error is defined as:

where

is the reference value of input impedance. So, the error dynamic can be extracted:

Assuming

as a control input and substituting (9) into (27):

Due to the uncertainty of model parameters in (30), the dynamic of error can be rewritten as follows:

where the state variable is mapped using

. Also, the model's uncertain parameters are introduced based on the following equations:

Assuming

,

, and

as estimations of the uncertain parameters, time-derivative of error in (30) can be rewritten as:

To develop the adaptive nonlinear controller, the Lyapunov function,

, the I

2C-MPPT system is introduced below where

and

is called parameter estimation weight (for

=1,2, and 3).

Time derivative of the Lyapunov function is:

Assuming

,

, and

:

Substituting

from (34) into (37):

Assuming:

and:

the time-derivate of the Lyapunov function in (38) will reduce to

which is a semi-definite negative function if

Hence, those assumptions in (39)-(42) result in the asymptotic stability of the closed-loop system.

The nonlinear

control law can be formulated based on (39):

Furthermore, the

estimation rules for uncertain parameters in (31)-(33) can be extracted using (40)-(42):

Figure 1.

Equivalent input impedance (Zin) of the converter.

Figure 1.

Equivalent input impedance (Zin) of the converter.

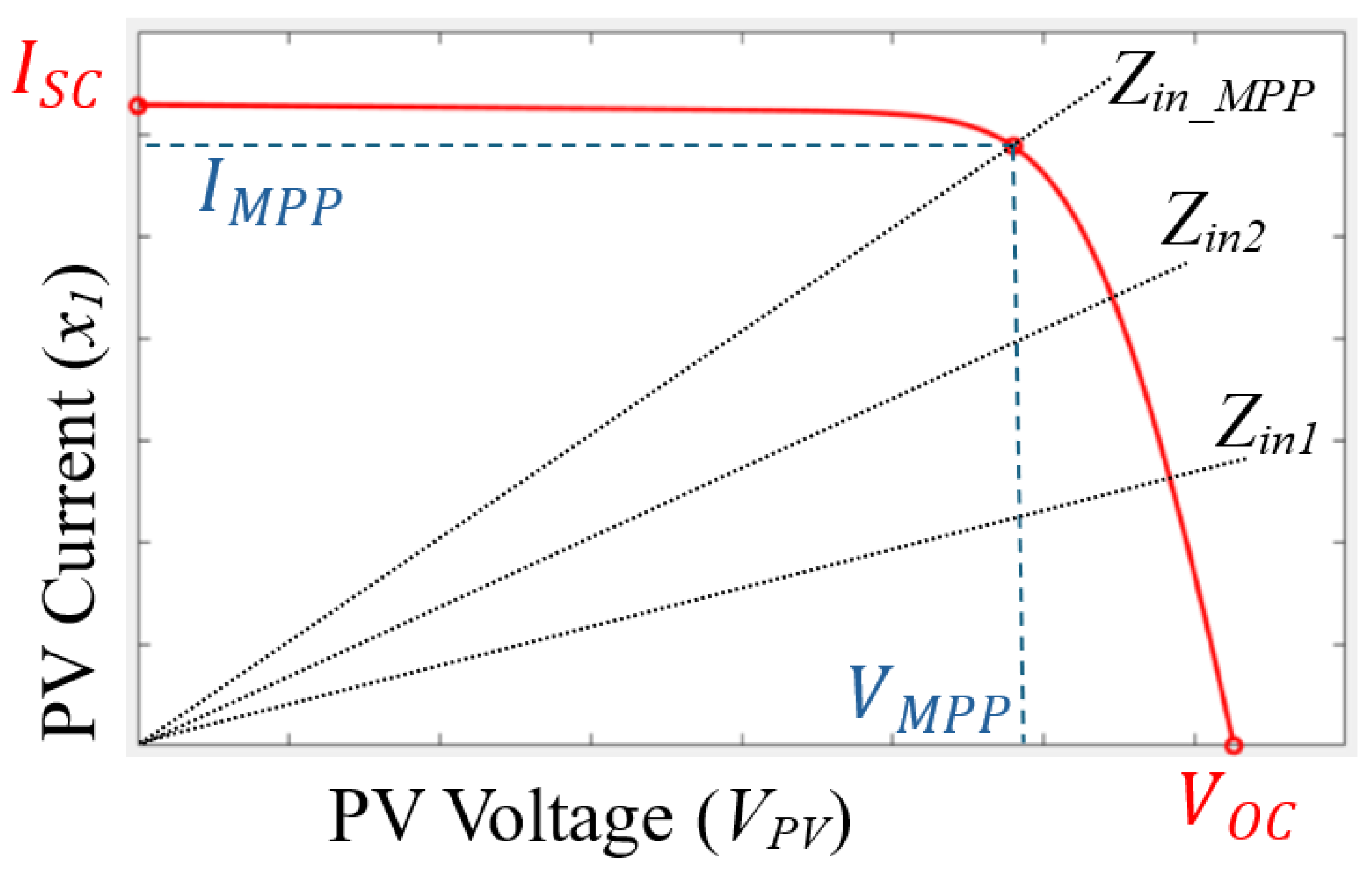

Figure 2.

I-V profile a typical PV generator and corresponding load lines. In the proposed I2C approach, adjusting the converter duty cycle alters the load line and equivalent input impedance (Zin), enabling MPPT of the generator.

Figure 2.

I-V profile a typical PV generator and corresponding load lines. In the proposed I2C approach, adjusting the converter duty cycle alters the load line and equivalent input impedance (Zin), enabling MPPT of the generator.

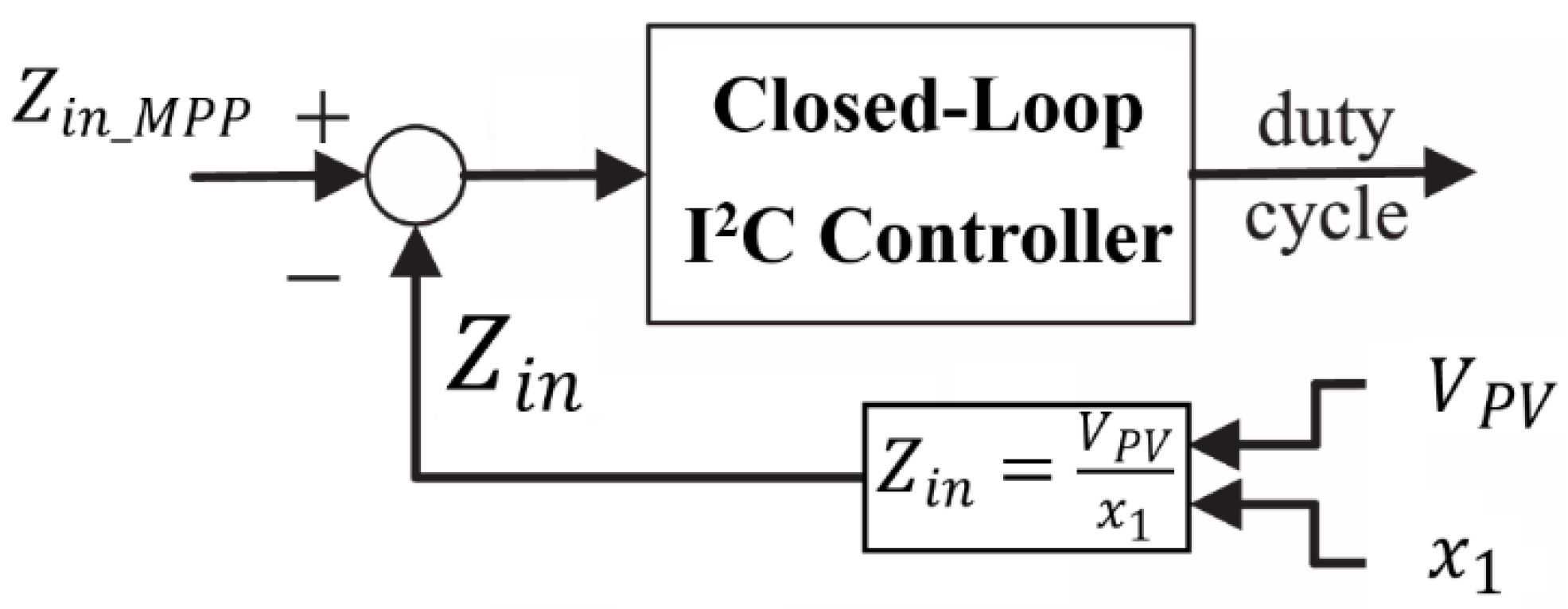

Figure 3.

Structure of the proposed I2C controller.

Figure 3.

Structure of the proposed I2C controller.

Figure 4.

Thevenin equivalent circuit representation of the input voltage source, with model parameters considered as uncertain.

Figure 4.

Thevenin equivalent circuit representation of the input voltage source, with model parameters considered as uncertain.

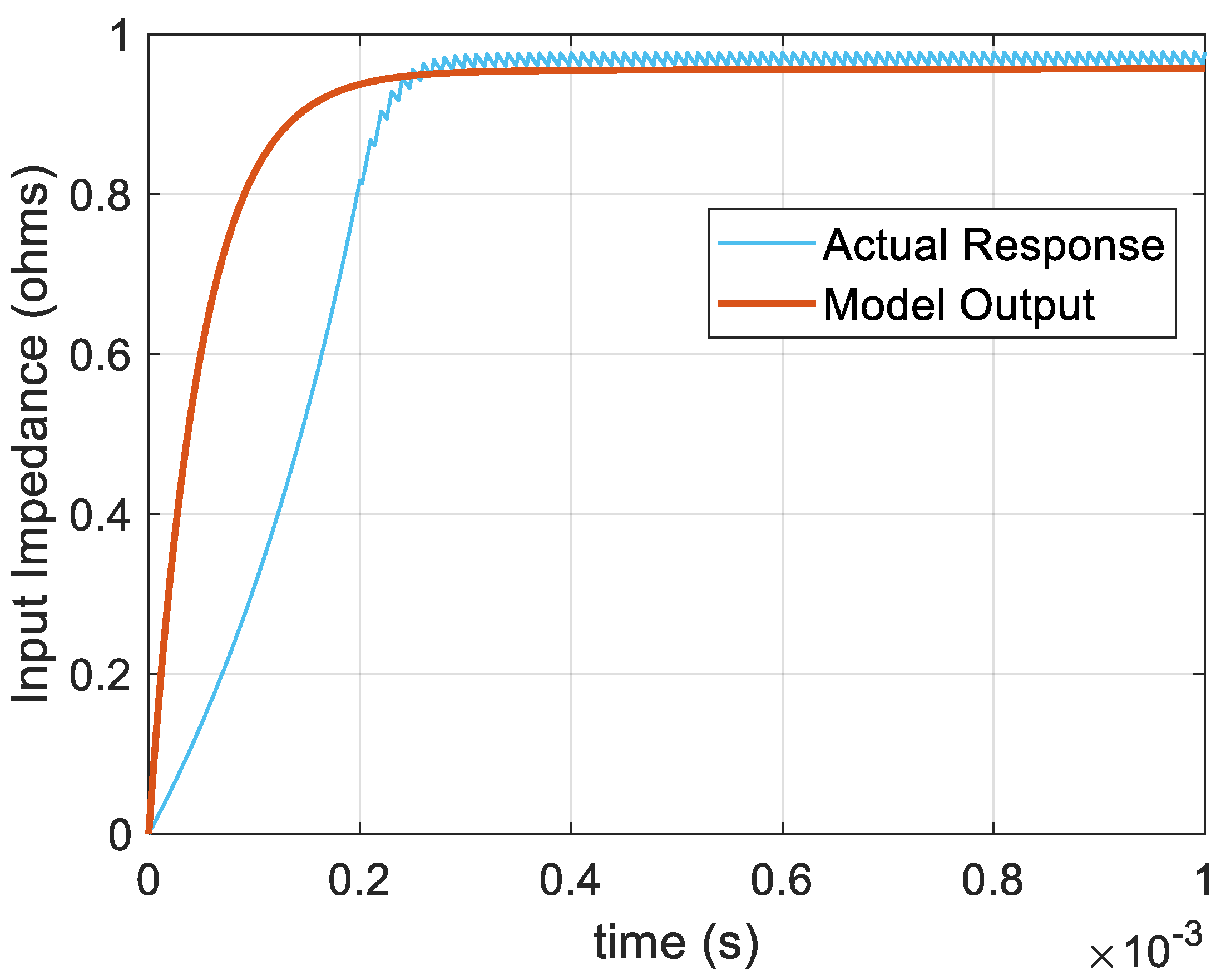

Figure 6.

Comparison of the output of the linearised model, based on the system's transfer function in

Figure 5, with the actual response from the Simulink simulation. The results demonstrate the accuracy of the developed linear model for I

2C-MPPT.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the output of the linearised model, based on the system's transfer function in

Figure 5, with the actual response from the Simulink simulation. The results demonstrate the accuracy of the developed linear model for I

2C-MPPT.

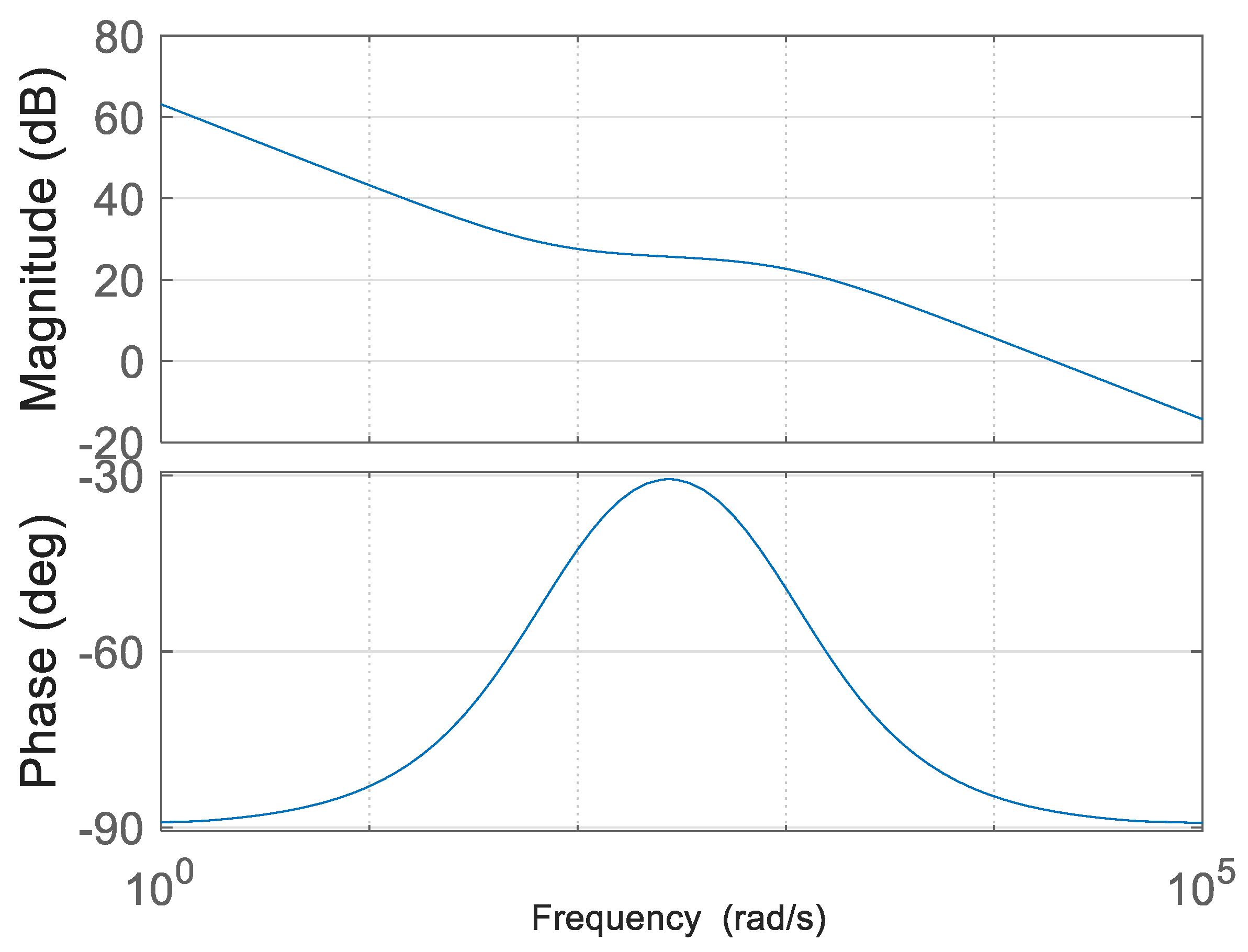

Figure 7.

Bode plot of the linearised I

2C-MPPT system, derived from the block diagram shown in

Figure 5, illustrating the phase margin and stability of the system.

Figure 7.

Bode plot of the linearised I

2C-MPPT system, derived from the block diagram shown in

Figure 5, illustrating the phase margin and stability of the system.

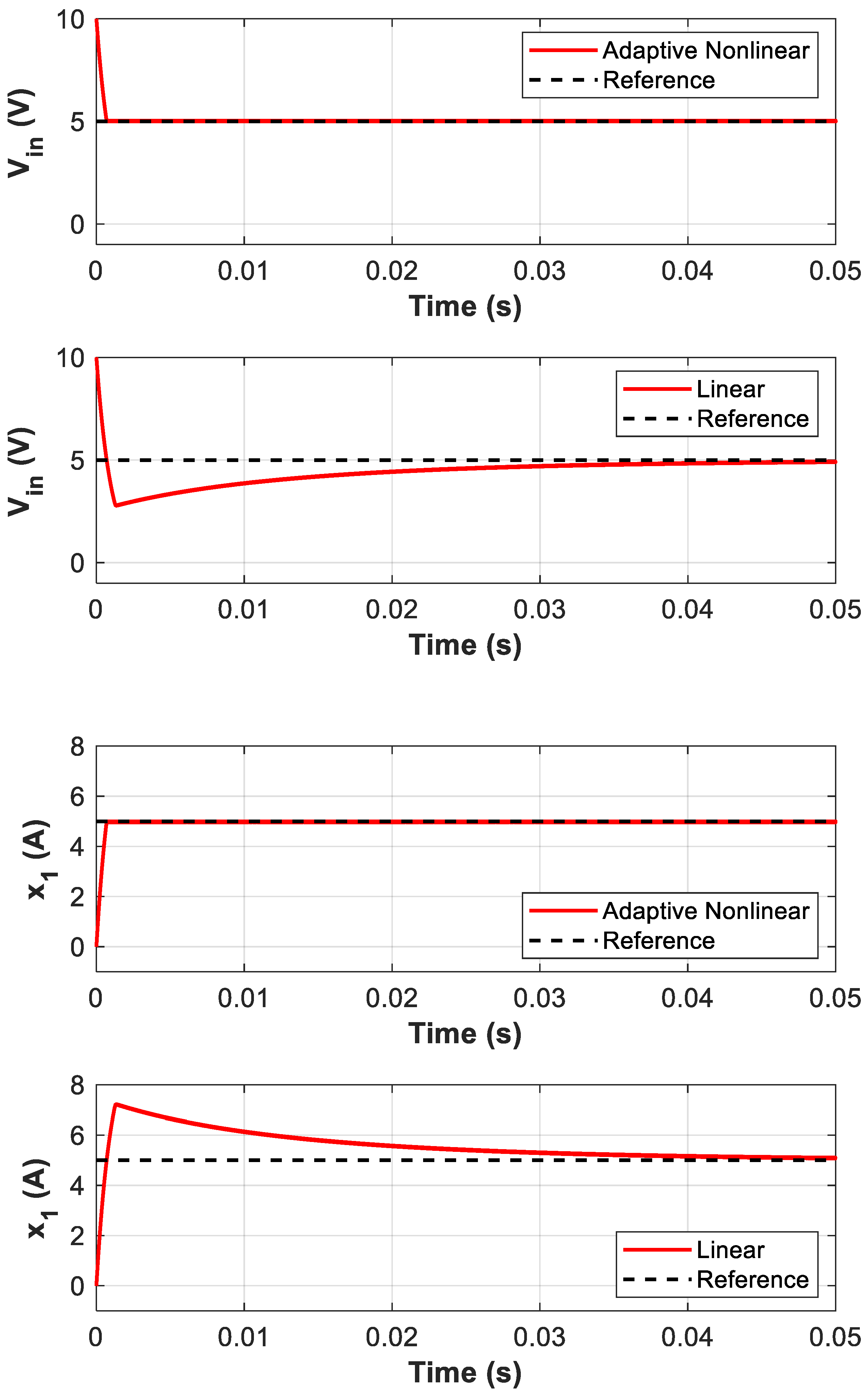

Figure 8.

Comparison of the converter input voltage (Vin) and current (x1) to their reference values for the proposed adaptive nonlinear controller and the linear controller during converter start-up. Both controllers achieve steady-state operation at the MPP, but the adaptive nonlinear controller exhibits a significantly faster transient response, demonstrating superior dynamic performance.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the converter input voltage (Vin) and current (x1) to their reference values for the proposed adaptive nonlinear controller and the linear controller during converter start-up. Both controllers achieve steady-state operation at the MPP, but the adaptive nonlinear controller exhibits a significantly faster transient response, demonstrating superior dynamic performance.

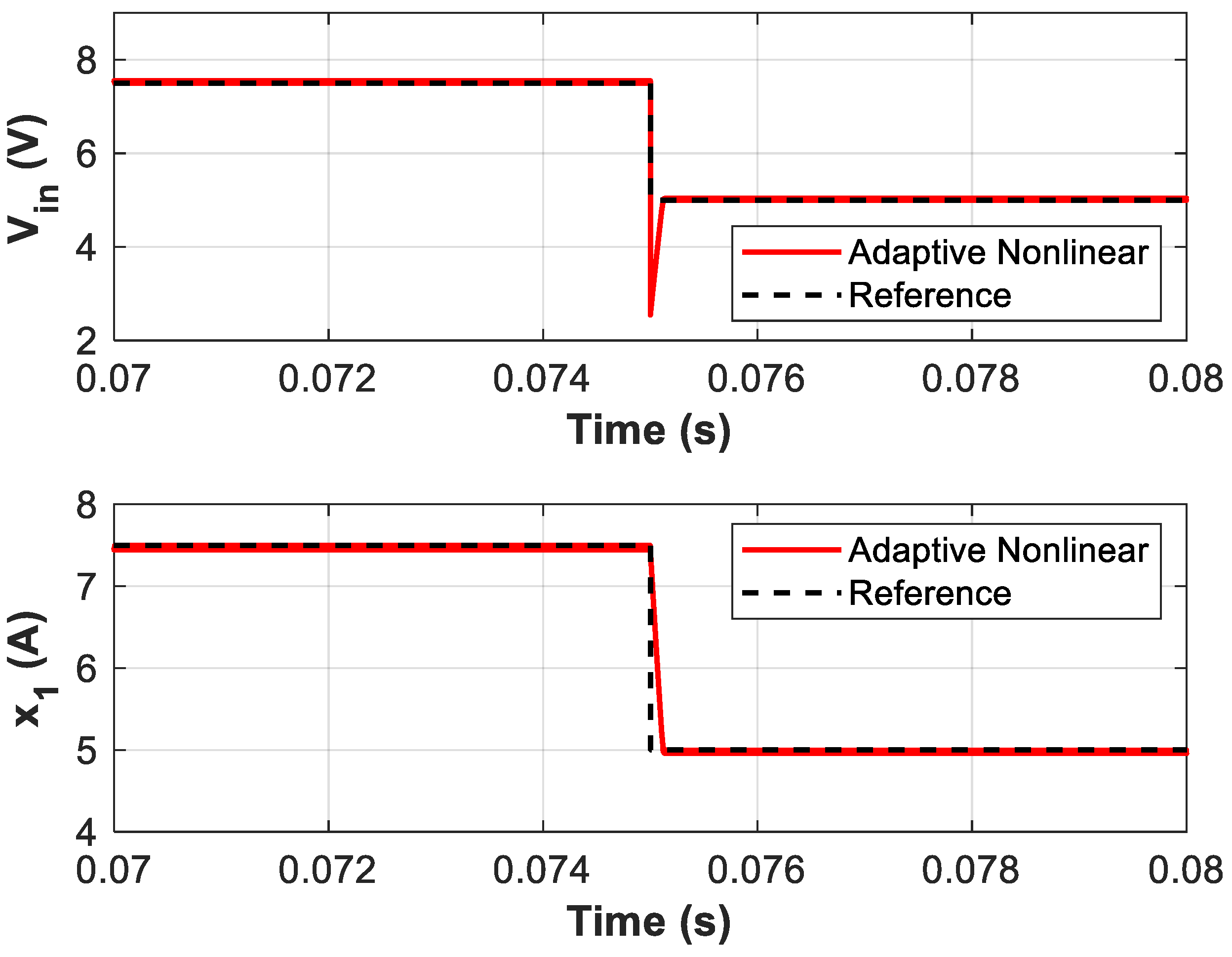

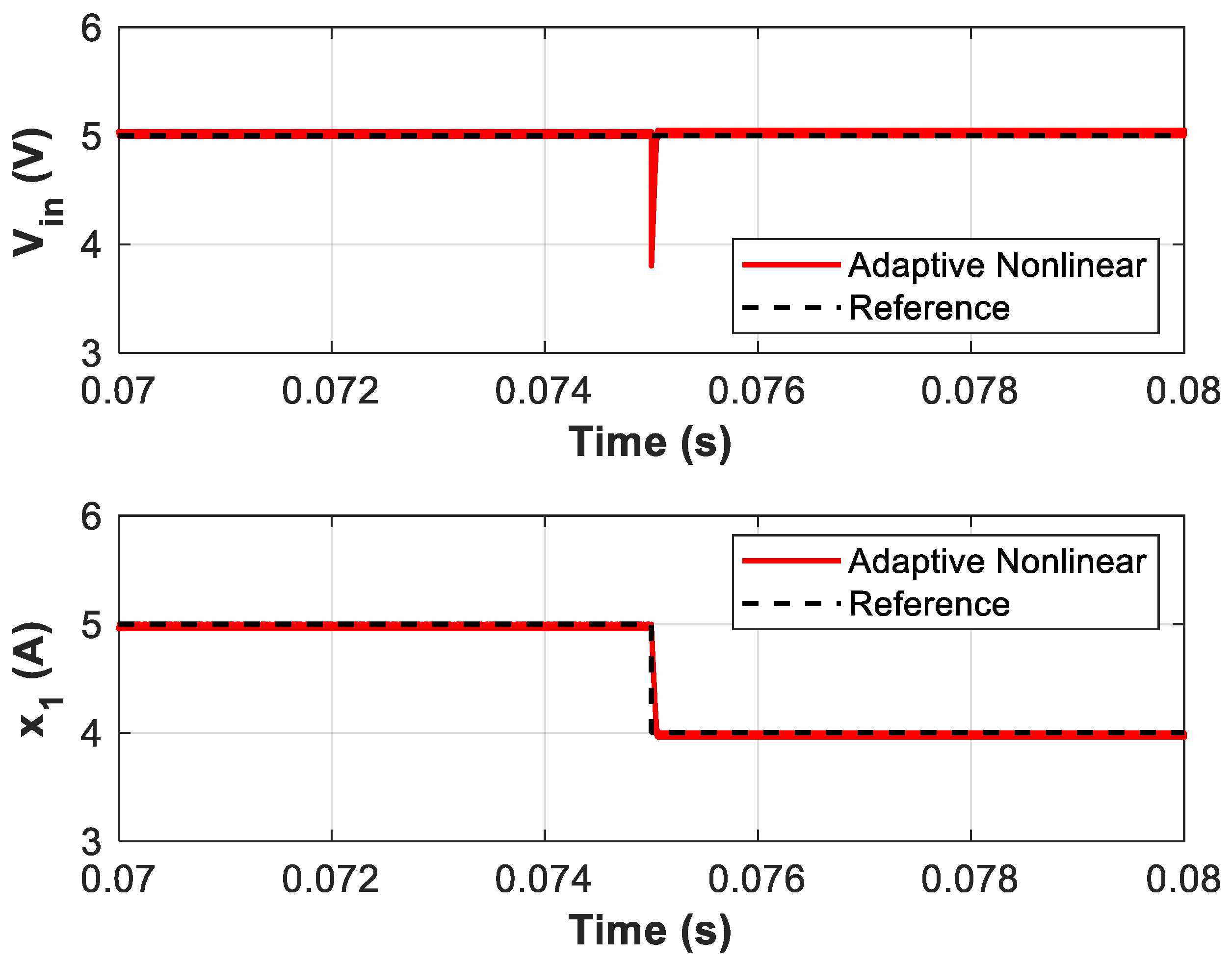

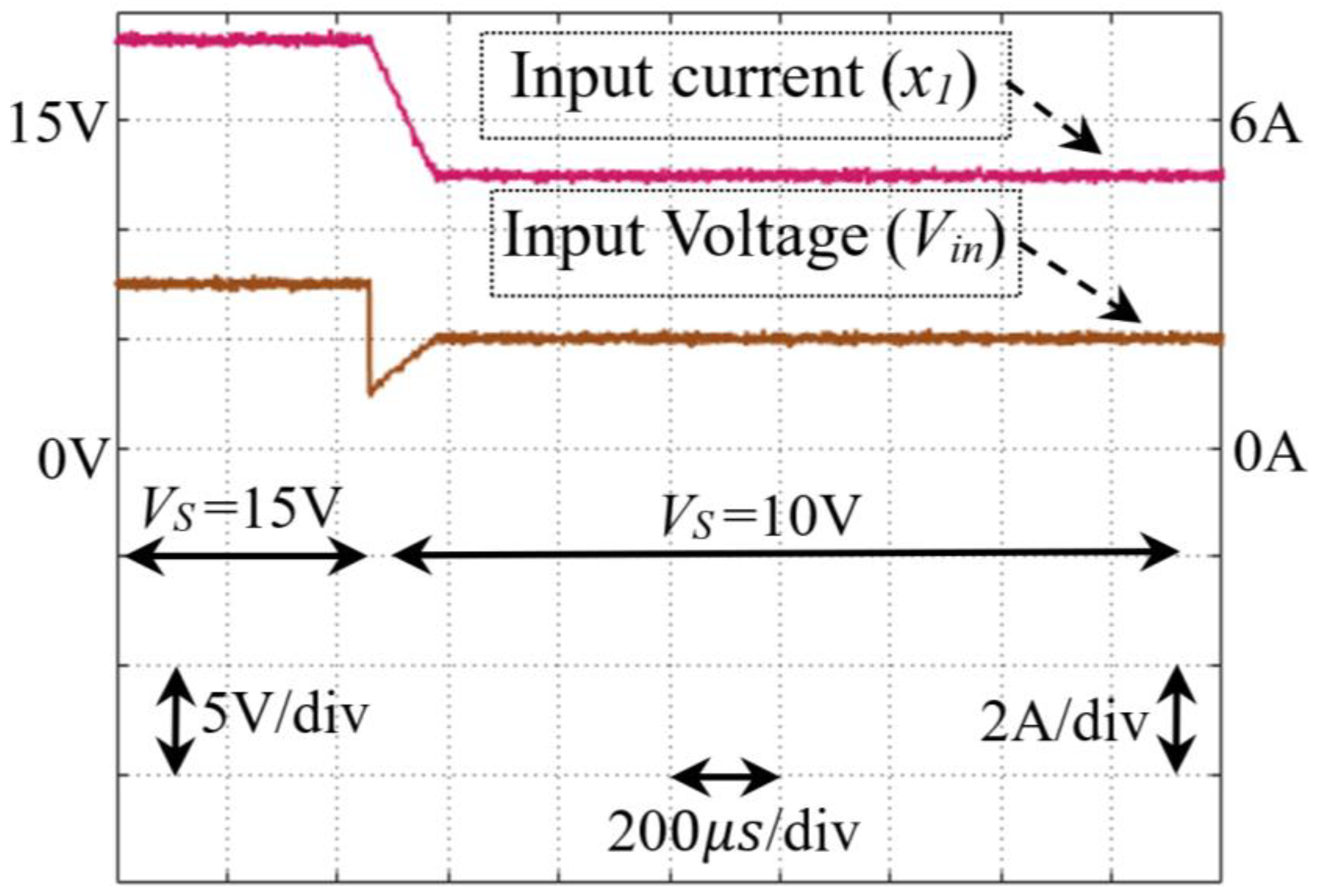

Figure 9.

Response of the adaptive nonlinear controller to a step change in the open-circuit voltage (VS) from 15V to 10V at t = 0.075s. The controller successfully adjusts the input voltage (Vin) and input current (x1) to their new reference values, maintaining stable operation and MPPT.

Figure 9.

Response of the adaptive nonlinear controller to a step change in the open-circuit voltage (VS) from 15V to 10V at t = 0.075s. The controller successfully adjusts the input voltage (Vin) and input current (x1) to their new reference values, maintaining stable operation and MPPT.

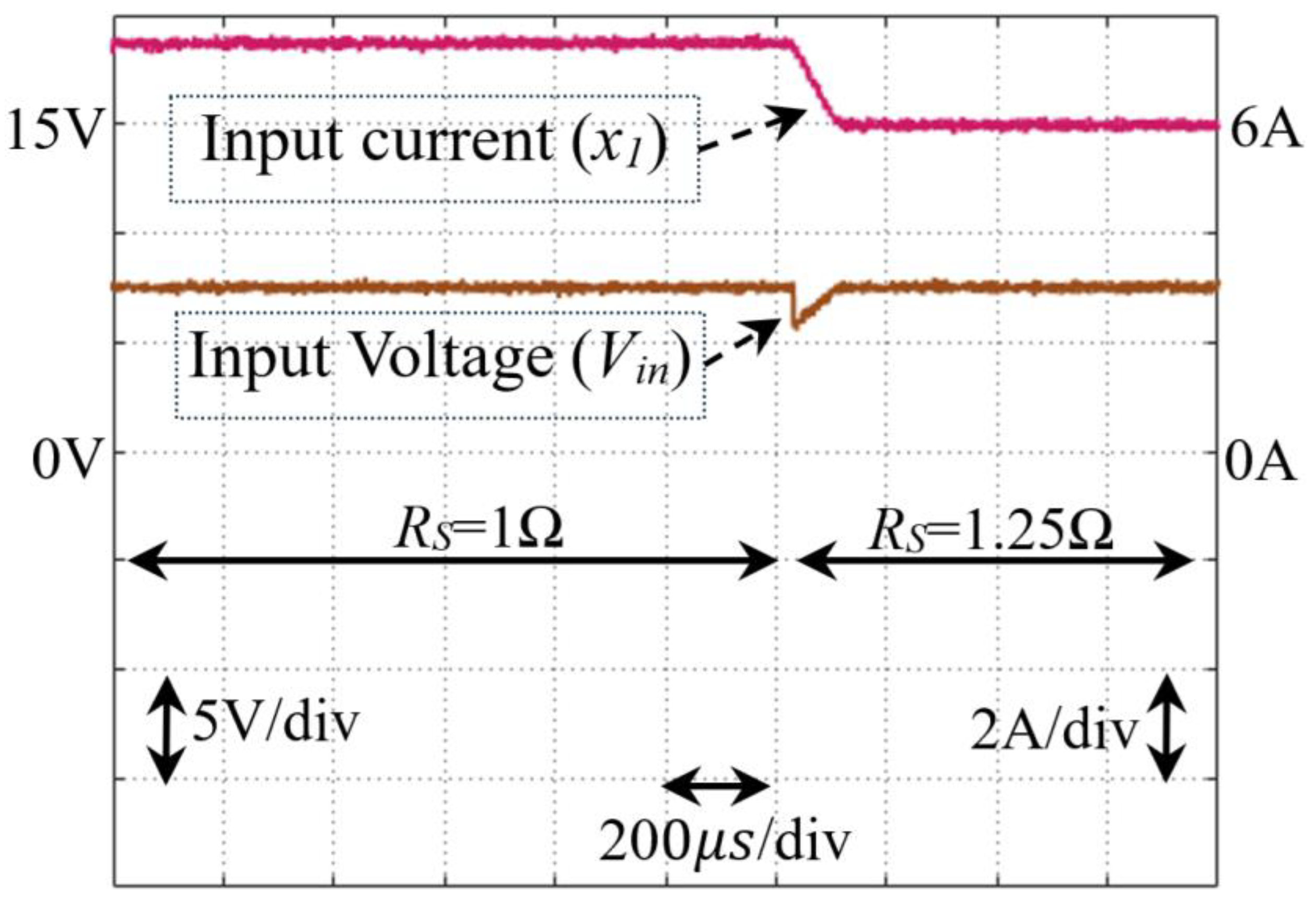

Figure 10.

Response of the adaptive backstepping controller to a step change in the internal resistance (RS) from 1Ω to 1.25Ω at t = 0.075s. The controller effectively tracks the new reference values of the input voltage (Vin) and current (x1), maintaining stable and robust system operation.

Figure 10.

Response of the adaptive backstepping controller to a step change in the internal resistance (RS) from 1Ω to 1.25Ω at t = 0.075s. The controller effectively tracks the new reference values of the input voltage (Vin) and current (x1), maintaining stable and robust system operation.

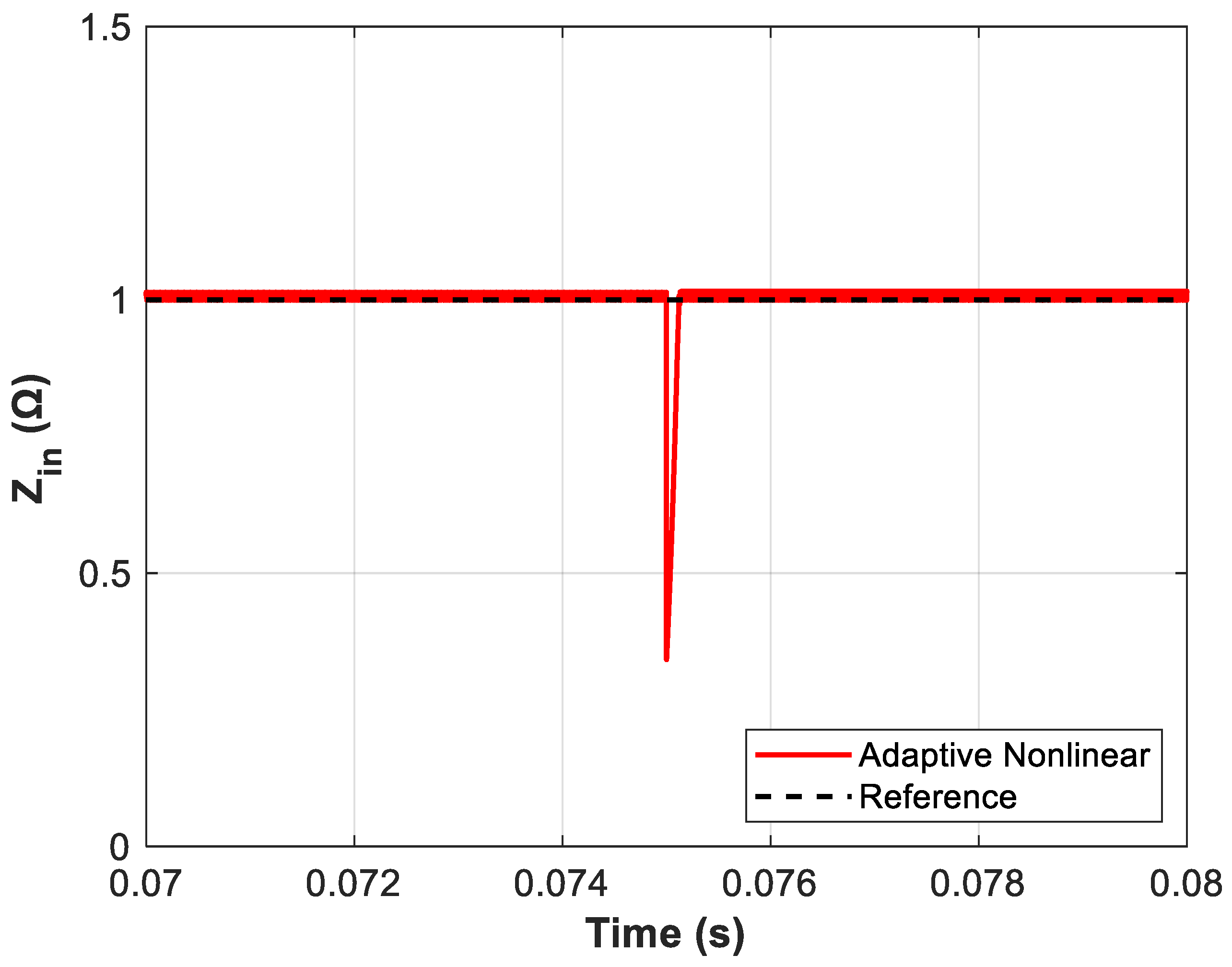

Figure 11.

Variation of the equivalent input impedance (Zin) to step changes in open-circuit voltage (VS) from 15V to 10V. The adaptive nonlinear controller effectively tracks the reference impedance (Zin_ref = Zin-MPP = RS = 1Ω), ensuring stable and optimal operation at MPP.

Figure 11.

Variation of the equivalent input impedance (Zin) to step changes in open-circuit voltage (VS) from 15V to 10V. The adaptive nonlinear controller effectively tracks the reference impedance (Zin_ref = Zin-MPP = RS = 1Ω), ensuring stable and optimal operation at MPP.

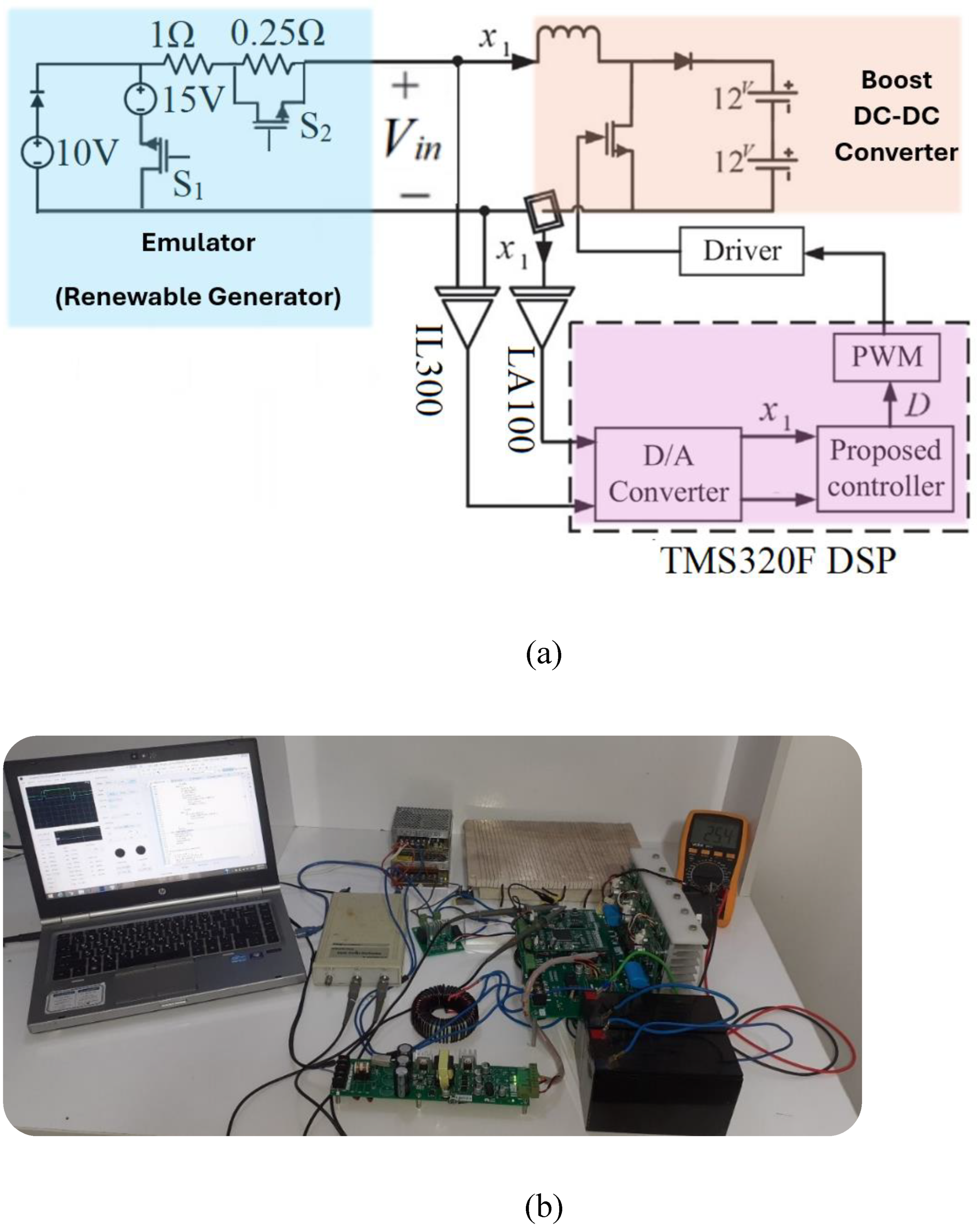

Figure 12.

Schematic of the experimental setup, including the emulator, power circuit, sensor connections, and controller implementation (a), and Experimental test rig illustrating the practical implementation of the proposed I²C-MPPT approach (b).

Figure 12.

Schematic of the experimental setup, including the emulator, power circuit, sensor connections, and controller implementation (a), and Experimental test rig illustrating the practical implementation of the proposed I²C-MPPT approach (b).

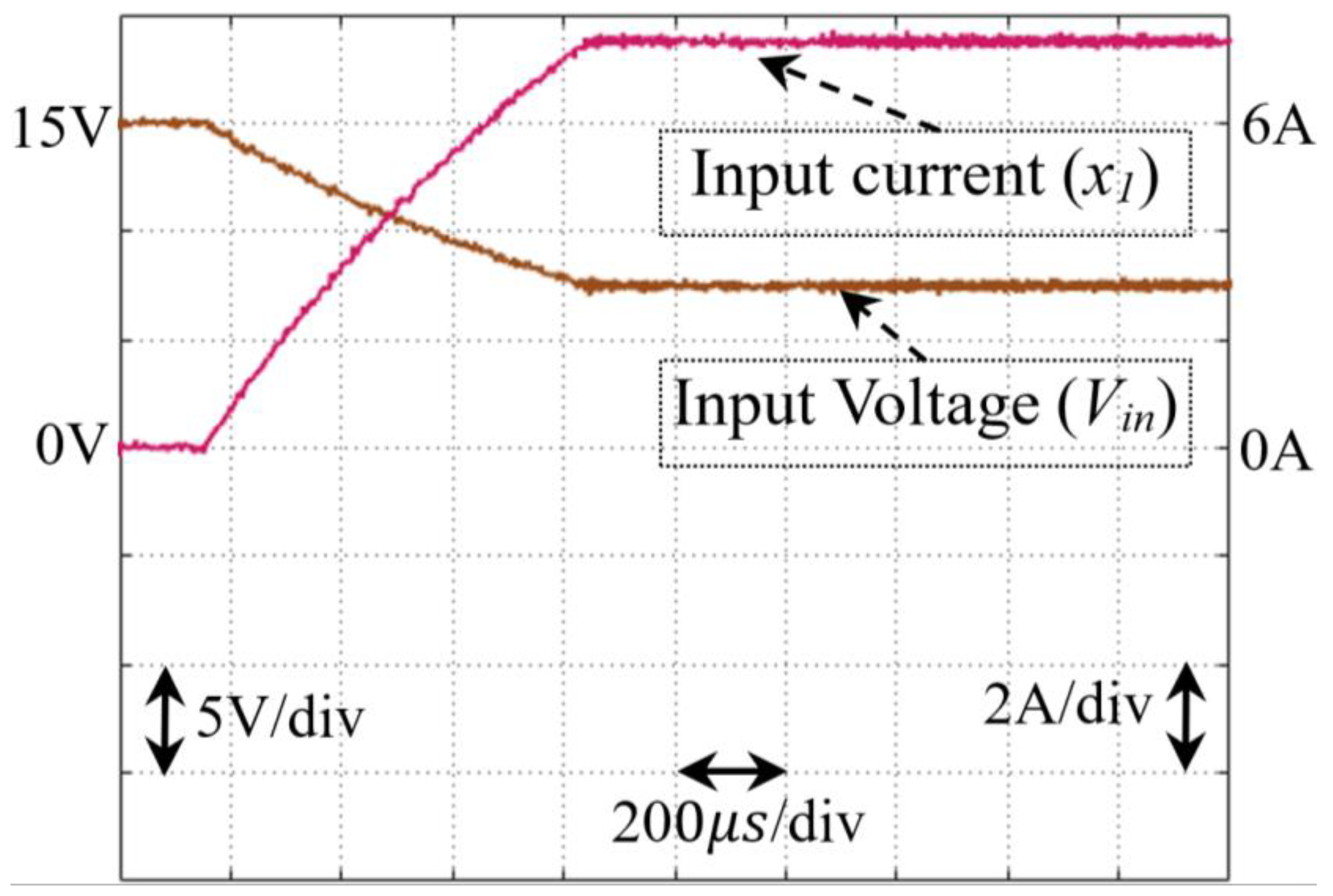

Figure 13.

Practical response of the converter during startup, demonstrating the controller's ability to achieve MPP operation by stabilising the input voltage at half of the open-circuit voltage.

Figure 13.

Practical response of the converter during startup, demonstrating the controller's ability to achieve MPP operation by stabilising the input voltage at half of the open-circuit voltage.

Figure 14.

Dynamic response of the proposed controller to a step change in open-circuit voltage (VS), confirming its ability to maintain MPPT under varying source conditions.

Figure 14.

Dynamic response of the proposed controller to a step change in open-circuit voltage (VS), confirming its ability to maintain MPPT under varying source conditions.

Figure 15.

System response to a step change in internal resistance (RS), illustrating the controller's capability to adapt and sustain MPP operation despite resistance variations.

Figure 15.

System response to a step change in internal resistance (RS), illustrating the controller's capability to adapt and sustain MPP operation despite resistance variations.

Table 1.

Nominal parameter values of the simulated system and experimental setup.

Table 1.

Nominal parameter values of the simulated system and experimental setup.

| Parameter |

Symbol |

Value |

| Open-Circuit Voltage |

VS |

10V |

| Internal Resistance |

RS |

1Ω |

| Load Voltage |

VB |

24V |

| Converter Inductance |

L |

1mH |

| Switching Frequency |

fS |

100kHz |