1. Introduction

Integrated sensing and communications (ISACs) are positioned to emerge as a critical component of next-generation multifunctional networks, offering robust support for a diverse array of emerging use cases and applications [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. By facilitating high-precision sensing capabilities and seamless communication across multiple domains, ISAC provides the foundational framework for driving innovations in intelligent communication networks, smart cities, autonomous systems, industrial automation, and a wide range of technological ecosystems [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Moreover, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) further augments their capabilities, offering a promising approach to addressing complex challenges within ecological and environmental ecosystems while expanding their applicability across multiple domains [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. This includes data-driven decision-making, predictive analytics, and the Internet of Things (IoT) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. By enabling real-time monitoring and data acquisition, these integrated technologies facilitate the extraction of actionable insights, thereby optimizing decision-making capability [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Furthermore, the emerging transition to goal-oriented and semantic communication paradigms is poised to play a pivotal role in the evolution of 6G networks and beyond [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. By jointly leveraging the contextual significance of data and its relevance to specific communication tasks, this approach enables the selective transmission of only pertinent information. This targeted communication strategy is particularly beneficial for machine-oriented systems, as it optimizes data exchange to support precise learning and decision-making objectives, thereby enhancing efficiency and reducing unnecessary data transition [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

Building upon the aforementioned advancements, the evolution of the Hydra Radio Access Network (H-RAN) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] envisions a comprehensive platform that seamlessly integrates diverse networks and technologies into a cohesive architecture. This includes communication and sensor networks, AI-driven systems, edge computing (EC), the Internet of Things (IoT), distributed ledgers, automated driving, smart cities, and vehicle-to-everything, to name a few [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. By fostering interoperability and cohesive operations, H-RAN aims to address the multifaceted requirements of emerging technologies, thereby creating an environment where diverse services can function concurrently [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. This innovative architecture enhances the interoperability of various technologies but also facilitates semantic-level communication [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Such integration is crucial for meeting contemporary urban environments’ dynamic demands while supporting a wide range of applications across multiple domains [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

This study elucidates the versatility of the H-RAN platform in accommodating a diverse range of contemporary applications and services via a unified infrastructure. Notably, H-RAN components facilitate real-time data acquisition on parking availability and calculate optimal routes between users and specified parking locations. Moreover, semantic communication is employed to prioritize the dissemination of contextually pertinent information, thereby minimizing redundancy and enhancing the relevance of the transmitted data. The simulation outcomes demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed system compared to state-of-the-art solutions across various scenarios, highlighting its potential to pioneer innovative applications in intelligent parking systems. Furthermore, the findings underscore the advanced capabilities of H-RAN-based semantic communication, which augments data processing and transmission by extracting and conveying only the most pertinent info necessary for a given task. This work contributes several novelties that enhance the system’s overall performance while maintaining cost-effectiveness as follows:

We introduce a multifunctional network architecture grounded in the Hydra Radio Access Network (H-RAN), designed to serve as a comprehensive platform for the integration of diverse applications and services. Within a broad spectrum of potential use cases, this study focuses on the development of an intelligent parking system as a representative application. The proposed system leverages data aggregated from Sensor Radio Units (SRUs) to facilitate the identification of optimal parking spaces and the computation of efficient routing paths. This is achieved by incorporating a range of dynamic and stochastic variables, such as real-time parking availability, proximity to parking locations, levels of traffic congestion, and temporal constraints. By emphasizing the critical role of infrastructure and data-sharing mechanisms, this research underscores the capacity of H-RAN to improve service efficiency while simultaneously reducing operational expenditures significantly.

We propose the incorporation of semantic communication into the image transmission process to enhance communication efficiency by optimizing data transmission through pixel-based classification.

We propose a hierarchical distribution of computational tasks across three tiers: Edge Computing (EC), Fog Computing (FC), and Cloud Computing (CC). Furthermore, this methodology effectively mitigates bottlenecks commonly encountered in centralized data processing frameworks.

We propose the utilization of an SMTL-based deep reinforcement learning (DRL) agent to optimize decision-making processes, including the identification of suitable parking slots and the determination of the most efficient routes. This adaptive mechanism allows the agent to progressively enhance its decision-making performance over time.

2. Literature Review

This section delves into recent advances in the field and provides a detailed assessment of the progress achieved, the limitations encountered, and the challenges addressed by existing approaches. Furthermore, we demonstrate how the proposed H-RAN surpasses current solutions by delivering superior performance and overcoming literature challenges. The discussion concludes with an evaluation of the characteristics of the H-RAN network, supported by an extensive review of the literature and validated by simulations.

However, recent advances in parking systems and occupancy detection technologies can generally be classified into four primary methodologies: vision-based approaches [

24,

25,

26,

27], moving sensor systems [

28,

29,

30], wireless sensor network (WSN) technologies [

31,

32,

33], and artificial intelligence and IoT-based solutions [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

To illustrate, vision-based solutions have garnered increasing attention for parking occupancy detection, driven by recent advances in computer vision. Unlike wireless sensor networks, where each sensor typically monitors a single parking space, or moving sensors, which rely on a single unit per sensor, camera sensors can cover multiple parking spaces simultaneously, thereby reducing the cost per space [

25,

26,

27]. In recent years, researchers have explored the application of deep learning models to enhance parking occupancy detection using vision-based systems. For instance, Nurullayev et al. Proposed a dilated convolutional neural network (CNN) designed for more robust parking occupancy detection [

27].

The use of moving sensors to detect parking occupancy belongs to the second category of technological approaches [

28,

29,

30]. This method leverages sensors embedded in mobile applications or probed into vehicles to monitor the availability of urban parking spaces. It involves collecting critical street parking information, determining parking availability, and examining more detailed aspects such as the frequency and impact of false parking detections. Although recent research highlights the significant potential of crowd-sensing for parking occupancy detection, its application remains limited to specific scenarios. To illustrate, crowd-sensing can be cost-intensive, as it requires the widespread deployment of sensors on numerous probe vehicles to collect adequate parking data. Additionally, this technique is less effective in large parking lots or rural areas where moving sensors are sparse [

29]. In addition to crowd-sensing methodologies, recent research has explored the application of single-moving sensors, such as drones, for parking occupancy detection. Drones are distinguished by their operational flexibility and expansive viewing range, making them a promising and cost-effective alternative to traditional crowd-sensing methods [

29,

30]. However, this approach is not without limitations, which may impede its effectiveness and practical implementation. Key issues include restricted battery life, safety concerns, susceptibility to adverse weather conditions, and variability in lighting environments.

Next, Wireless Sensor Network (WSN) [

31,

32,

33] solutions employ individual sensor nodes to monitor each parking space, necessitating multiple nodes to oversee numerous spots. However, the use of basic algorithms in these systems can result in elevated false detection rates under specific conditions. Despite these limitations, WSNs exhibit a high degree of robustness against individual sensor failures, owing to the redundancy inherent in the deployment of multiple sensor nodes. Nevertheless, this robustness introduces significant cost and scalability challenges, particularly for in-ground sensors such as loops [

31,

32]. Nevertheless, this robustness introduces significant cost and scalability challenges, particularly for in-ground sensors such as loops [

31]. Finally, several advanced technologies, including cloud computing, fog computing, edge computing, IoT devices, and surveillance systems, have recently been explored within the context of smart parking systems [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Each of these technologies offers unique advantages while simultaneously introducing limitations. For instance, cloud computing relies on remote servers hosted online for data storage, management, and processing. While it provides substantial computational power and scalability, it can introduce latency in real-time applications due to the necessity of transmitting data to centralized servers for processing. For instance, Piccialli et al. [

34] introduced a deep learning-based approach to predicting parking lot occupancy, aiming to optimize traffic flow and reduce the time spent searching for parking during peak periods. Similarly, Ghulam et al. [

35] proposed a cloud-based parking system that integrates IoT devices, sensors, a cloud server, and client software to streamline parking space allocation. The study in [

36] investigated the use of edge computing (EC) for parking system surveillance tasks, particularly focusing on detecting parking occupancy through real-time video feeds. Additionally, the researchers in [

37] developed a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL)-based framework for IoT-enabled parking systems, incorporating smart cameras, fog computing (FC), and cloud computing (CC). In this framework, DRL algorithms deployed at fog nodes classify vehicles and allocate available parking spaces. Furthermore, the authors in [

39] proposed an intelligent parking system utilizing an IoT framework that collects real-time data, processes it through the CC, and recommends suitable nearby parking spaces for vehicles. In conclusion, traditional parking systems operate as standalone infrastructures that necessitate dedicated hardware platforms, leading to significant costs associated with system deployment, management, and maintenance. Furthermore, these systems rely on centralized data processing architectures, making them susceptible to inefficiencies such as errors, delays in handling large data volumes, and increased system overhead. While deploying a single network for a specific task may simplify initial implementation, it introduces considerable challenges, including limited flexibility, performance bottlenecks, management complexities, and restricted interoperability. To address these limitations, this study proposes an innovative vision-based parking system utilizing the Hydra Radio Access Network (H-RAN) as a practical application. By leveraging the distinctive capabilities of H-RAN, the proposed approach enhances system performance across multiple key dimensions, including information accuracy, intelligence, decision-making efficiency, reliability, operational effectiveness, and overall cost efficiency.

3. System Model

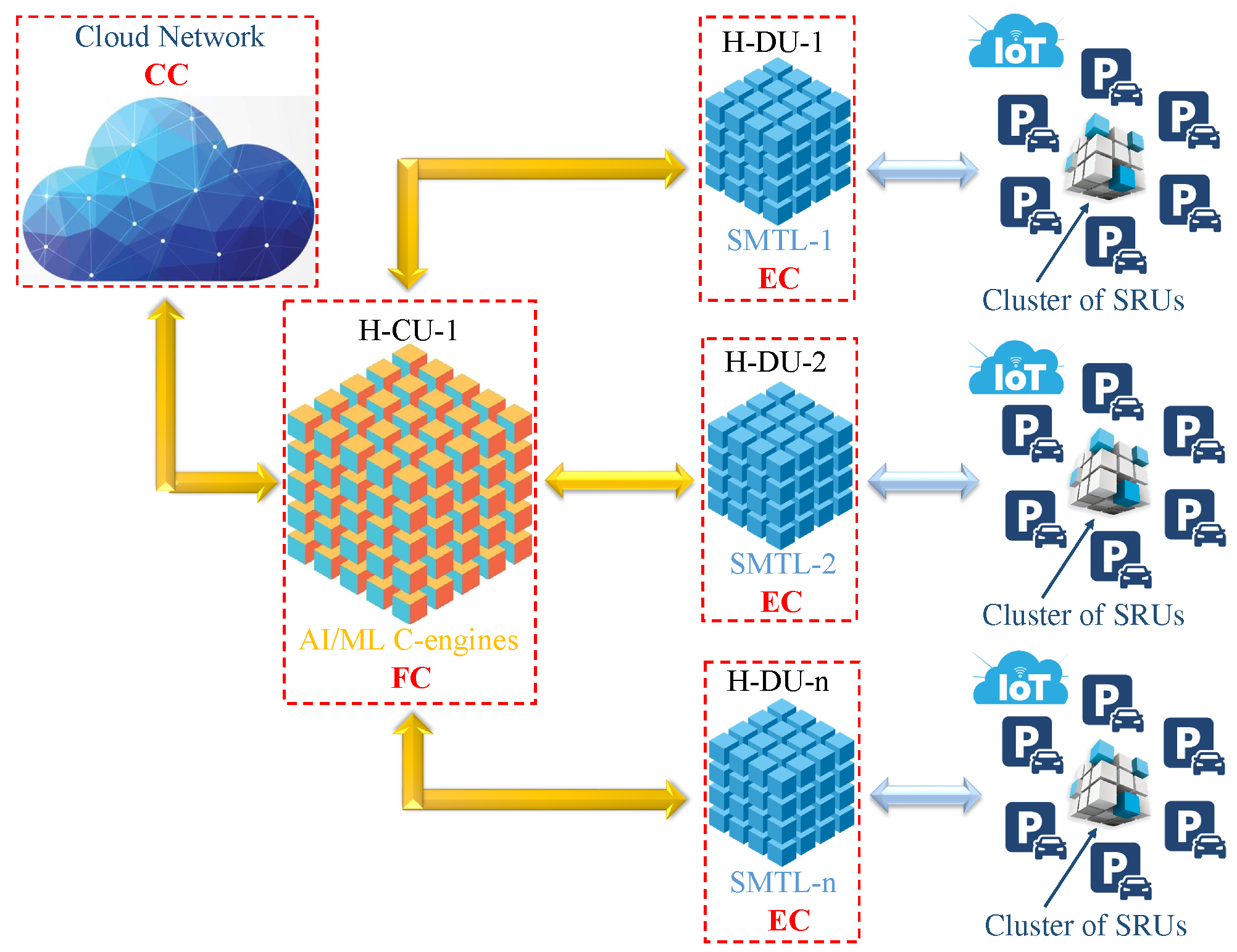

3.1. Overview

The H-RAN network is conceptually designed to emulate the human body’s structural and functional attributes. Within this framework, the sensors integrated into the network are analogous to human sensory organs, while the AI/ML component functions as its cognitive counterpart, mirroring the human brain’s decision-making capabilities. This design ensures that the network can efficiently interpret and react to external stimuli, akin to how a human would respond in similar circumstances. In the H-RAN framework, the dense deployment of sensor and radio units (SRUs) is essential to ensure sufficient coverage and meet the escalating demands of connected devices and applications. In this setting, SRUs monitor parking space availability and deliver real-time traffic information [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. In addition, the study employs multi-sparse input and multi-task learning (SMTL), which is particularly conducive to addressing diverse and complex problem domains, as it enables the simultaneous execution of multiple tasks with varying objectives [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Moreover, the study proposes a multi-faceted cooperation architecture, which facilitates the precise collection of parking spot information through centralized control of Hydra distributed units (H-DUs). By aggregating and analyzing observations from multiple SRUs, the H-RAN network generates an increasingly accurate and comprehensive representation [

1,

2,

3]. These SRUs interface with H-RAN components, which include:

Hydra Distributed Units (H-DUs): A primary component for edge computing (EC), enabling localized data processing and reducing latency.

Hydra Central Units (H-CUs): Responsible for fog computing (FC), facilitating intermediate data processing and coordination between edge and cloud layers.

Hydra RAN Intelligent Controllers (H-RICs): Oversee and manage cloud computing (CC), providing centralized control, advanced analytics, and large-scale data storage.

3.2. Multi-Sparse Input and Multi-Task Learning (SMTL)

As depicted in

Figure 1, the H-RAN architecture incorporates an EC-based SMTL model within the H-DU. Unlike conventional supervised learning approaches, the SMTL model maps multi-input sample spaces to multiple output spaces, enabling concurrent execution of diverse EC tasks. This functionality is particularly advantageous in dynamic environments, where the SMTL model excels at capturing and mapping intricate relationships from heterogeneous input spaces to task-specific outputs [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

3.3. Semantic Communications

Given that H-RAN networks are engineered to cope with substantial data flows generated by dense deployments of SRUs and IoT, to name a few. However, this surge in data can lead to considerable communication overhead, potentially hindering network efficiency. To address this challenge, semantic communication, as well as edge computing, are integrated in order to reduce communication overhead and associated expenditures. To illustrate, semantic communication systems categorize image pixels into regions of interest and non-interest [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. This differentiation enables the system to prioritize essential parts of an image for transmission, while less relevant areas can be transmitted with lower granularity or omitted entirely [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Moreover, reinforcement learning (RL) is integrated into this framework to enhance communication effectiveness by leveraging the semantic significance of the transmitted data. Let’s assume

X refers to the raw input data to be transmitted (e.g., sensor readings, images) and

Y is task-relevant information derived from

X using AI/ML-D models.

T represents the task the receiver aims to execute. The objective is to minimize the transmission of

X while providing assurance that

Y includes all the task-relevant information required by the task

where

is an AI/ML-driven function that extracts the context-relevant semantic information

Y from the raw data

X, conditioned on the task

T. In RL, rewards can be modeled as follows

where

and

balance the trade-off between task accuracy and transmission expense. The RL agent learns to incrementally adjust the encoding and transmission parameters in response to environmental feedback to maximize

over time.

4. Proposed Tasks

This section examines the rationale for employing the SMTL model within the parking system. To this end, deep neural networks (DNNs) are utilized to model intricate nonlinear relationships between inputs and outputs. Furthermore, we propose a two-step system designed to select parking lots and determine optimal routes according to SRU data. We developed two binary classification-based ML models demonstrating the efficacy of support vector machines (SVMs) in classifying parking slots and road routes [

16,

17]. Binary classification models assign instances to one of two distinct classes. In this case, the first model classifies parking slots as either "unoccupied" or "occupied," while the second model categorizes road routes into "congested" or "uncongested." This dual approach is beneficial for applications where clear demarcation between classes is essential for decision-making.

4.1. SMTL’s Input

In the proposed model, let

X be the input feature vector for the DNN, which includes parking slot information (e.g., parking slot availability) and road information (e.g., traffic conditions on roads leading to parking lots, distance to the parking lot, estimated time to reach the parking lot based on traffic, distance to each parking slot from the current location). Thus, the input feature vector can be represented as

, where

represents the

feature (e.g., distance to a parking slot, congestion level on the road). Each hidden layer receives the output from the previous layer, transforming it through weighted sums and activation functions. This process is repeated for all hidden layers until reaching the output layer. The DNN consists of multiple neuron layers, with each layer

l comprising several neurons. In each layer, the number of neurons can be denoted as

, where

l represents the layer index. For each neuron in the hidden layer and the output layer, the output is a weighted sum of the inputs passed through an activation function. As a result, the first hidden layer output can be expressed as follows

where

is the weight matrix for the first hidden layer,

indicates the bias vector for the first hidden layer,

represents the weighted sum of the inputs,

is the activation output (e.g., ReLU, Sigmoid) of the first hidden layer, and

refers to the activation function. The output layer represents the classification decision regarding parking slot selection. Suppose there are

m parking slots. The DNN output is a softmax layer with

m outputs representing the probability of selecting each parking slot

where

and

are the weights and biases for the output layer.

is the SoftMax output, where each element represents the probability of selecting a specific parking slot.

4.2. Feature Extraction

In the image data

, let’s assume the input image from the camera is represented as a 3D tensor of pixel values

, where

H is the height,

W is the width, and

C is the number of channels (e.g., RGB channels). For image data, the DNN typically starts with convolutional layers to extract spatial features:

where

represents the feature map of

convolutional layer,

denotes the convolutional kernel for layer

l,

signifies the convolutional bias for layer

l,

indicates the convolution function, and

is the activation function (e.g., ReLU). After convolution, a pooling layer is used to reduce spatial dimensions while retaining significant features

where

is the output of the mmm-th fully connected layer.

flatten represents the flattened output from the previous layer.

and

are the weight matrix and bias for the

fully connected layer, and

is the activation function, typically ReLU. The output layer represents a fully connected layer that produces the feature vector to be fed into the DRL model

where Fe is the feature vector representing the extracted information.

and

are the output layer weights and biases, respectively. In this approach, a deep neural network (YOLO) [

42,

43,

44]is used to extract features from the input image

I. These features form the feature map

, where

are reduced spatial dimensions and

D is the depth of the feature map

4.3. Bounding Box Prediction

In a detection head, a direct bounding box regression of YOLO [

42,

43,

44]is used to predict bounding boxes

for each parking slot in the image. The bounding box for the

parking slot is parameterized by its center coordinates

and its width

and height

.

The DNN outputs a set of

N such as bounding boxes for detected parking slots

These bounding boxes localize the regions of interest (RoIs) in the image that correspond to individual parking slots. We used ROI pooling to convert each bounding box into a fixed-size feature map for further processing

where

is the pooled feature map for the

parking slot, extracted from the full feature map

F.

4.4. Classifying Each Parking Slot as Occupied or Unoccupied

Once the parking slots are detected and localized, the next step is to classify each parking slot as either occupied or unoccupied using DNN-based feature vector extraction. For each detected parking slot

i, the DNN extracts a feature vector

from the corresponding region in the feature map ROIs [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]

This feature vector represents the key features of the parking slot

i, which will be used for classification. The extracted feature vector

is passed through a fully connected layer to produce a logit

for each parking slot, where the two values in

represent the logit for "occupied" (class 1) and "unoccupied" (class 0).

where

is the weight matrix, and

is the bias term.

The logits

are passed through a softmax function to produce a probability distribution over the two classes (occupied/unoccupied):

where:

In the classification decision, the predicted class for each parking slot is selected via identification of the class with the maximum probability

This yields a binary classification for each parking slot, where if the parking slot is occupied and if it is unoccupied.

4.5. Identifying the Most Efficient Route

Let

represent a set of features for each road segment. These features could include traffic density, average vehicle speed, road conditions, weather conditions, and time of day. Let’s assume

is the label, where

indicates the route is congested and

indicates the route is uncongested. A binary classification model from SVM [

40,

41] is used to predict congestion probability for each segment of a route:

where

f is a non-linear function parameterized by learned model parameters

() The classification decision for a given road segment is made based on a threshold

[

52].

Once the road segments are classified as "congested" or "uncongested", the shortest path Dijkstra’s algorithm [

45] is applied to identify the optimal route between the source and destination. A graph

, where

V refers to the list of intersections or waypoints, and

E is the set of road segments. Each edge

between vertices

i and

j is associated with a weight

, representing travel time or distance. The weight

can be dynamically adjusted based on congestion classification

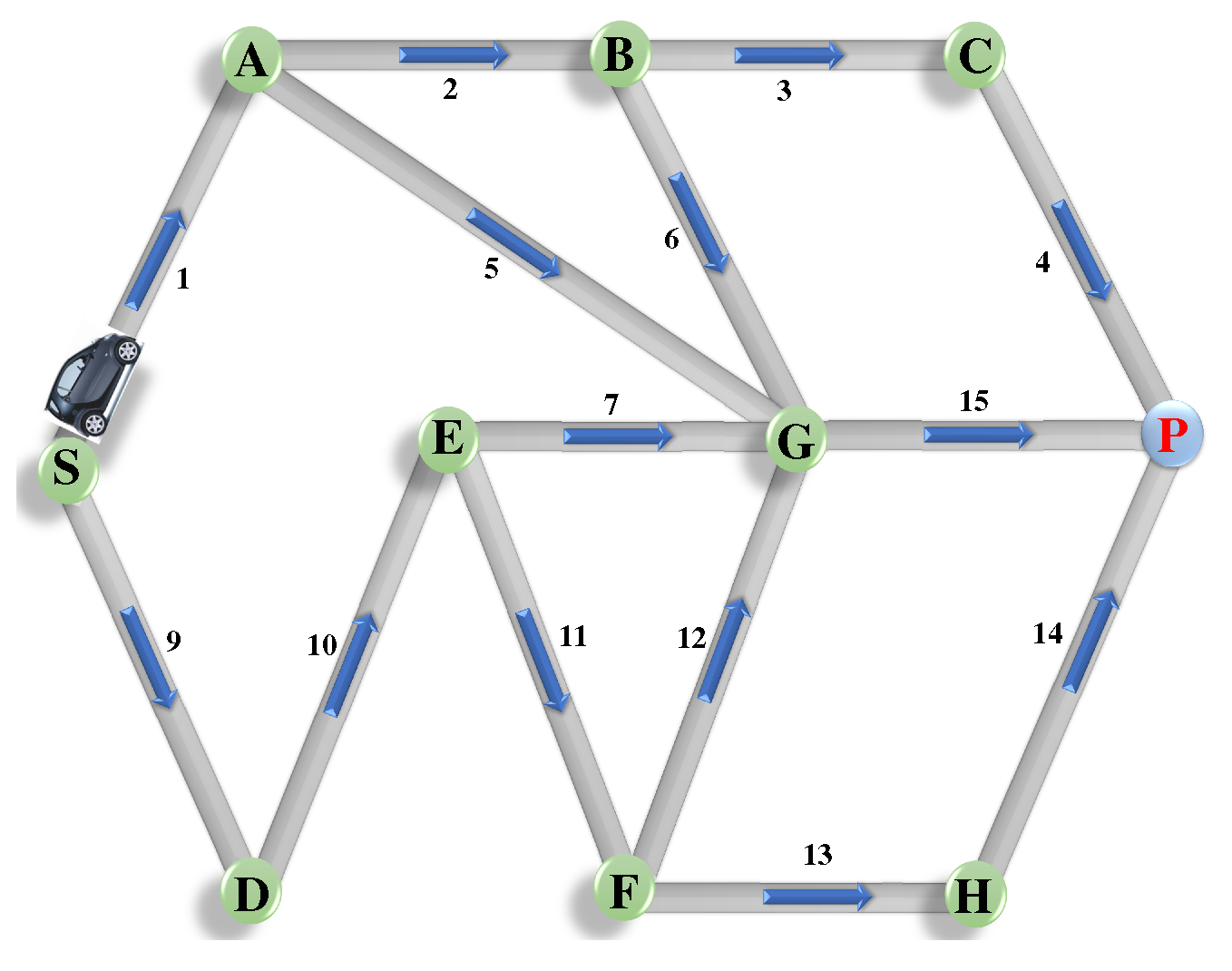

As illustrated in

Figure 3, by applying Dijkstra’s algorithm [

45], the system computes the shortest route

between the source

s and destination

d by minimizing the total weight

Here, the sum is taken over all edges on route R, and the route with the minimum total travel time is selected.

Figure 2.

Identify the optimal route between the source and destination.

Figure 2.

Identify the optimal route between the source and destination.

5. Semantic Representation

After classifying each parking slot, the system constructs a semantic representation [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] based on the classification results. This representation is a compressed binary vector that summarizes the parking slot statuses in the image [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. According to semantic representation, let

N be the total number of parking slots detected. The semantic vector

is constructed as

where

if the

parking slot is classified as "unoccupied" and

if the

parking slot is classified as "occupied." For instance, for an image with

parking slots, if the first and third slots are occupied, and the second and fourth are unoccupied, the semantic vector

S would be:

This compressed binary vector contains essential information about the parking lot, which can be used for real-time decision-making [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. .

5.1. Joint Source-Channel Coding (JSCC)

The deepJSCC [

23,

24] involves using a DNN to encode images into channel inputs directly, optimizing the encoding and decoding process for end-to-end performance in the presence of channel noise. Given an input image

, where

H,

W, and

C represent the height, width, and number of color channels (e.g., RGB channels) respectively, the encoder network

transforms

into a latent representation

, which is designed to be robust to noise and smaller in dimension than

.

where

d is the latent space dimension, and

represents the encoder’s learnable parameters.

The received signal

is then decoded by the decoder network

to reconstruct the image, yielding

, where

are the decoder’s learnable parameters [

22,

23,

24].

The model parameters

and

are optimized to minimize the loss

, ensuring that the encoding-decoding process over noisy channels preserves image quality:

This end-to-end learning approach combines compression and error resilience in a single process, making it robust to channel conditions without separate source and channel coding blocks [

21,

22,

23,

24].

5.2. Channel Model

The transmitted signal

goes through a noisy communication channel, where the received signal

Y is the sum of the transmitted signal

and additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) channel [

24,

46]

The JSCC decoder maps the received noisy signal

back to an estimate of the original source

. The decoding process can be described as:

where

is the decoder function, which can also be represented by a neural network in modern implementations. To train a JSCC system, the loss function measures the difference between the original source

X and the reconstructed source

. For example, in the source of paring slot images, we used the mean squared error (MSE) [

23,

24]

where the expectation is over the distribution of the source data and the noise introduced by the channel.

5.3. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Task

Once the feature vector Fe is extracted by the DNN, it serves as input to the Task-based DRL model [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]

where the DNN outputs Q-learning in policy gradient methods, depending on the Task-based DRL approach. Let’s assume the state

at time step

t encompasses all relevant information about the environment, which may include

a vector indicating the availability of parking slots (binary values, where 1 indicates available and 0 indicates occupied).

a vector representing the distance from the current location to each parking slot.

vector representing the estimated travel times to each parking slot, considering traffic conditions. Thus, the state can be described as

The action

represents the decision to select a particular parking slot at time step

t. If there are

n parking slots, then:

The reward function

is designed to encourage the selection of the most suitable parking slot according to various factors [

47,

48,

49]. For example, a positive reward

is given for selecting an available parking slot that minimizes travel time. A negative reward

is given for selecting an occupied slot or one with a long travel time. Reward functions can be formulated as follows

where

is the indicator function.

5.4. Deep Q-Learning

In Q-Learning, the DNN approximates the Q-value function

, where

represents the neural network weights. The Q-value function estimates the expected cumulative reward for taking action

a in state

s and following the optimal policy thereafter [

48,

49,

50,

51] The Q-value update rule in DRL is given as

where

is the immediate reward,

is the discount factor, and

is the target Q-value, with

being the weights of a target network. The loss function to train is typically represented as [

50,

51,

52]

5.5. Policy Gradient Methods

The policy

is directly parameterized by the model, which outputs a probability distribution over actions given a state [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. The proposed policy gradient methods aim to maximize the expected cumulative reward, which can be represented as

The gradient of this objective concerning policy parameters

is:

where

is the action-value function under the policy

. During training, the parameters

are updated using gradient descent methods to maximize the expected reward for the policy gradient [

49,

50,

51].

5.6. Sequential Decision-Making

At each time step

t, the DNN takes the observed state

as input and outputs action probabilities in the policy gradient. The DRL agent then selects an action

(i.e., chooses a parking slot) based on the output, observes the resulting state

and rewards

, and updates the DNN parameters to improve future decision-making [

48,

49,

50,

51]. Let’s assume the state input

, for DNN output policy

at the action

for the reward which can be written as

This combined approach enables the parking slot selection system to make informed and adaptive decisions based on the evolving environment, optimizing for factors like availability, traffic conditions, and distance.

5.7. Loss Function

During the training of the DNN, a loss function

is defined, evaluating the discrepancy between the predicted output and the accurate labels (e.g., the actual selected parking slots). Cross-entropy loss is widely used in classification tasks

where

denotes the true label (1 indicates the correct parking slot, 0 for others), and

is the predicted probability for the

parking slot. We propose a network architecture that solves the selection of parking spaces as separate problems or tasks. As shown in

Figure 4, we designed two separate branches of neurons at the output layer, each with a different task to be implemented: parking space selection and route selection. The two branches of neurons,

and

, indicate the probability of each parking space and route being the best parking space and route candidates for a given position and actual traffic conditions. The network aims to provide appropriate parking spaces to be sensed, with the user choosing a parking space of their choice. Synthetically, we combine the probabilities of parking space and route to construct probabilities of all possible parking spaces and routes. Accordingly, the outer product determines whether each parking space and route is the best option.

Considering that the outer product of two vectors and produces a matrix of size , the result of the outer product is flattened to produce a vector of size entries. Considering that the output layer has neurons, represents the number of trainable weights in the output layer.

As the outer product of two vectors and is a matrix of size , we flatten the result of the outer product to obtain a vector with entries. According to (18), there is no trainable parameter in the construction of probabilities of beam pairs. As the output layer has NAP+NUT neurons, the number of trainable weights at the output layer is (nh+1)(NAP+NUT). In practical scenarios where the training dataset is limited, the multi-task structured network can be trained better than the single task structured one, as the former has far fewer trainable parameters. In the Appendix, we discuss the relationship between the training of the multi-task network with outer-product and that of classical multi-task classifiers.

6. Materials and Methods

6.1. Performance Evaluation

Since the objective of this study is to evaluate the performance of a multifunctional H-RAN-based network to implement an intelligent parking system using the H-RAN architecture in conjunction with DeepJSCC enabled by semantic communications, two simulation scenarios were conducted to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. In the first simulation, the system’s performance was evaluated based on its accuracy in detecting available parking spaces and determining the optimal route to the destination. In the second simulation, the focus was on assessing the efficiency of the system’s communication, with particular emphasis on the impact of semantic communication techniques on the overall functionality and effectiveness of the proposed approach.

6.2. Datasets Collection and Implementation

In this study, the DRL framework was trained and validated using the CNRPark-EXT parking slot dataset [

51,

52,

53]. This dataset was captured using smart cameras equipped with ARM Cortex-A7 CPUs, 1GB DDR2 RAM, and 32GB microSD cards for storage, operating in video modes of 1080p30, 720p60, and VGA90. The camera module offers a

horizontal and

vertical field of view at a resolution of 2592 × 1944 pixels. The dataset includes 150,000 labeled images of occupied and vacant parking spaces, collected from 164 parking spots on the National Research Council (CNR) campus in Pisa. Data acquisition involved nine smart cameras positioned at different angles over various days, encompassing diverse weather and lighting conditions to ensure comprehensive coverage. Challenging scenarios such as occlusions and shadows were also incorporated to increase occupancy detection complexity. To enhance detection accuracy, the dataset underwent meticulous manual annotation, with parking spaces segmented and labeled. As illustrated in

Figure 2, Regions of Interest (ROIs) are identified using object detection models, specifically YOLOv5 [

42], allowing the system to focus data transmission on relevant areas. The semantic communication model assigns importance metrics to data segments, prioritizing unoccupied parking spaces while omitting details about occupied ones, as illustrated in

Figure 2. A trained object detection and classification model further processes semantically prioritized data, focusing on critical features such as unoccupied parking spaces while disregarding non-essential background information. To minimize latency and optimize bandwidth usage, real-time image processing is performed locally at the edge, specifically within the H-DU. This approach enables data prioritization and semantic communication to be applied locally before transmitting refined information to the central server.

Figure 3.

Simulation Results

Figure 3.

Simulation Results

Figure 4.

Simulation Results

Figure 4.

Simulation Results

6.3. First Simulation Settings

This section outlines the simulations conducted to assess the proposed model’s performance through various simulation methodologies. These include OpenAI [

54], TensorFlow [

55], PyTorch [

56], Python [

57], simulation of urban mobility (SUMO) [

58], and Adam optimizer [

59]. The approach establishes a comprehensive framework for simulating a smart parking scenario that employs DRL and DNNs, with a specific focus on optimizing efficiency and mitigating congestion. The first simulation scenario is designed to develop a smart parking system capable of managing parking slot availability. This framework computes driving times and identifies the optimal route from a driver’s current location to a designated parking area, thereby avoiding congested routes. OpenAI Gym is utilized to create a custom environment that simulates the parking scenario through the definition of state and action spaces. The state space encompasses variables such as the current vehicle location (represented by x and y coordinates), the availability of parking slots (occupied vs. unoccupied), estimated driving times to each accessible parking slot, the distance to the nearest parking area, and the congestion levels on various routes, depicted as congestion indexes. The action space allows the system to navigate in specific directions and select parking positions. In training the model, we employed the collected DNN and DRL models, updating weights based on the loss computed from Q-values. The simulation integrates critical factors such as parking slot availability and driving time. The environment is updated in real-time to reflect parking slot status whenever vehicles park or vacate, ensuring accurate availability data. To estimate driving times for each available slot, the system utilizes heuristic distance calculations, including Euclidean distance and pathfinding algorithms such as Dijkstra’s algorithm [

45] to efficiently navigate around congested areas. Moreover, real-time updates to the congestion avoidance model incorporate congestion scores within the state representation. A reward function is designed to incentivize actions that lead to shorter driving times, successful parking in free slots, and avoidance of congested routes. The real-time feedback feature is implemented through a user-friendly interface based on Python and Flask [

57], effectively visualizing current parking slot availability, estimated driving times, congestion levels, and recommended routes. The model’s efficacy is tested and assessed using multiple performance metrics, including route estimation, classification accuracy, and parking slot selection. An iterative improvement process is initiated to refine both the model and the environment based on collected feedback and performance outcomes.

6.4. First Simulation Steps

This section delineates the employment of DNNs for parking space classification, the SUMO for traffic simulation, and DRL for parking and route optimization. Initially, we combine DNN-based parking space classification with a DRL agent, which is responsible for optimizing both parking allocation and route selection. In this integrated framework, the DNN model first analyzes images of parking lots to classify available parking spaces. Subsequently, the DRL agent utilizes traffic data generated from SUMO to identify the optimal parking spot and determine the most efficient route to reach it, utilizing Dijkstra’s algorithm. Using a dataset of preprocessed parking lot images, the DNN model is trained using supervised learning techniques that minimize cross-entropy loss for binary classification, assisted by the Adam optimizer. To assess traffic flow within the system, we leverage SUMO, an open-source simulation tool specifically designed for modeling vehicular environments and traffic dynamics. SUMO enables the simulation of traffic behavior in urban settings, thus assisting in identifying the most efficient routes to various parking locations. Python 3.10 is used for system integration and scripting, facilitating interaction between the DNN and DRL models and the SUMO traffic simulation. TensorFlow serves as the primary framework for constructing and training the DNN model to classify parking spaces as "occupied" or "unoccupied". As an alternative, the PyTorch library is also employed to harness GPU capabilities for deep learning tasks. Furthermore, OpenAI Gym is utilized for defining custom environments and for integration with SUMO, enabling the simulation of diverse traffic scenarios and parking space allocations. Within this context, the DRL setup defines state, actions, and rewards. The state encapsulates current traffic conditions, the user’s location, and the status of parking slots (occupied or unoccupied). Actions involve assigning a vehicle to a designated parking slot and selecting the most efficient route from the user’s present location to the parking area. The reward function is formulated based on the optimality of the chosen parking slot and route, taking into account critical factors such as proximity to the destination and prevailing traffic congestion levels. . We used Deep Q-Network (DQN) to train the agent for parking allocation and route optimization.

where

is the action-value function,

r is the reward,

is the discount factor, and

is the optimal future action. The DRL agent learns the optimal policy by interacting with the simulated environment. The agent explores different actions (choosing different parking slots and routes) and receives feedback (reward) based on its efficiency.

6.5. Experimental Semantic Communications Setup

The dataset utilized for this study is the CNRPark-EXT parking slot dataset, partitioned into training, validation, and test sets in a 70%, 15%, and 15% ratio, respectively. Model training is implemented with the PyTorch library and optimized using the Adam optimizer, configured with a learning rate of 0.0001, = 0.9, and = 0.999. The model employs a batch size of 32 and early stopping, with a patience of 25 epochs, and a maximum training limit of 1000 epochs. To enhance robustness against channel noise, we apply Turbo error correction to compressed images, simulating transmission over noisy channels with both AWGN and fading channel conditions across a range of SNR levels. For DeepJSCC, a convolutional neural network (CNN)-based encoder-decoder model is implemented. The encoder compresses and adds error resilience by encoding images into compact latent representations, while the decoder reconstructs images from these representations, effectively handling channel noise. During simulation, each test set image is encoded, transmitted over a noisy channel, and reconstructed at the receiver side using DeepJSCC. Images from the CNRPark-EXT dataset are randomly selected, resized to 64x64 pixels for reduced model complexity, and normalized to align with model input requirements. The input comprises a three-channel image of 64x64 pixels. Initial feature extraction is performed by a two-dimensional convolutional layer (Conv2D) with 16 filters, (2,2) kernels, and a stride of 1. This is followed by two concatenated Conv2D layers with 16 filters, (2,2) kernels, and a stride of 2, which compress the 16-channel feature representation. The output of the semantic system consists of 16-channel features, each with dimensions of 23x23 pixels. To reconstruct the image, the (16 × 23 × 23)-sized feature map is decompressed using two concatenated transpose convolutional layers (TranConv2D) with 16 filters, (3,3) kernels, and a stride of 2. Finally, TranConv2D restores the 64x64 pixel image in three channels, utilizing 3 filters with 2x2 kernels and a stride of 1.

6.6. Results of Analysis

In the simulation, the proposed model compares against the Morphological image processing [

57], IIoT Three-Tier [

36], and LDPC for channel coding [

60].

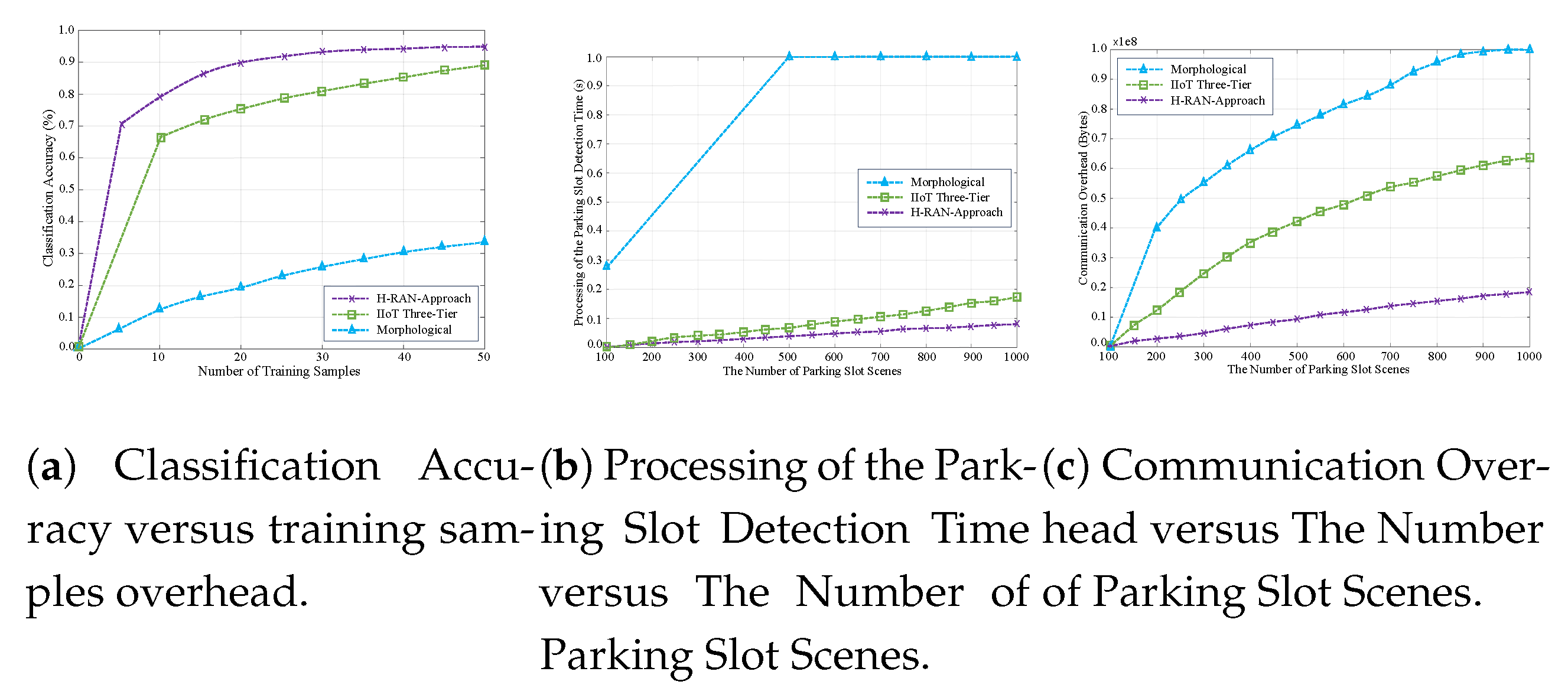

Figure 4(a) illustrates the simulation outcomes of the proposed system, showcasing its robust performance in identifying parking slots with an accuracy of approximately 95%. This high degree of precision is primarily attributed to the incorporation of semantic communications within DNN. By focusing on the transmission of semantically meaningful information specifically tailored to parking slot identification, the system significantly reduces errors and enhances overall accuracy. In comparison, the Morphological approach achieves a maximum accuracy of 40%, while the Three-Tier approach demonstrates a relatively improved performance with an accuracy of 88%. The superior efficacy of the proposed system can be largely ascribed to the use of semantic encoding, which prioritizes the transmission of critical features.

Figure 4(b) provides a comparative analysis of processing times for parking slot image classification, contrasting the proposed scheme with existing methodologies. The proposed model demonstrates superior performance by effectively mitigating noise interference and adapting to variations in signal quality, achieving a latency of approximately 0.1 seconds for seamless image data transmission. This represents a significant improvement over conventional methods, which are more susceptible to processing delays. Furthermore, the proposed model enhances image transmission efficiency by concurrently addressing source and channel coding, thereby eliminating the sequential encoding and decoding processes typically associated with traditional DNN frameworks. This integrated approach not only simplifies data processing but also reduces computational overhead.

Figure 4(c) delineates the factors influencing variations in communication overhead across different methodologies, underscoring the efficacy of the proposed scheme, which maintains an overhead of less than 20%. The findings reveal that the proposed approach enhances data transmission efficiency by prioritizing information’s semantic relevance over its literal representation. This semantic-centric strategy eliminates non-essential data, thereby curtailing the volume of information transmitted over the network, a key factor contributing to excessive overhead. Consequently, the proposed scheme optimizes bandwidth and computational resources, making it a more sustainable solution for long-term deployment in urban environments. In contrast, traditional methods exhibit considerably higher overhead, with the Three-Tier approach reaching 53% and the Morphological approach surpassing 90

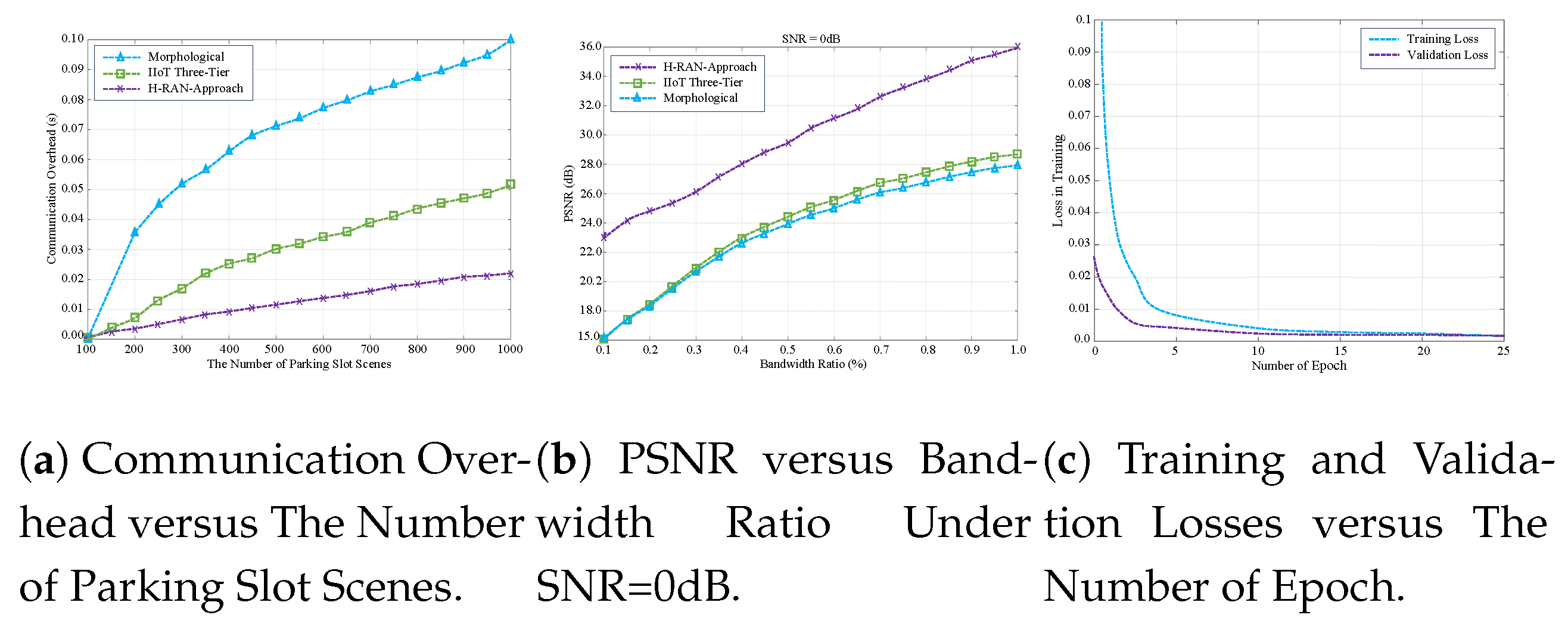

Figure 5(a) provides a comparative analysis of processing times across various methodologies, highlighting the superior efficiency of the proposed approach. Notably, the proposed scheme achieves a reduction in communication overhead exceeding 75% during parking slot image processing. This significant improvement improves the system’s capacity to identify and communicate available parking slots in real-time with increased operational efficiency. By effectively eliminating non-essential data, the proposed approach minimizes the volume of information requiring processing and transmission.

Figure 5(b) depicts the simulation results of the proposed system model, showcasing the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) measurements for different channel bandwidth distributions over additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) channels at a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 0 dB. PSNR is a well-established metric for evaluating the quality of reconstructed images compared to their original versions, particularly in contexts involving image compression and transmission over noisy communication channels. Higher PSNR values signify superior image fidelity and reconstruction accuracy, which are essential for reliable system performance. The analysis of the bandwidth ratio demonstrates that the proposed model efficiently utilizes available bandwidth, leading to reduced processing times and minimized communication overhead critical factors for real-time functionality in smart parking systems. The observed enhancements in processing efficiency, relative to conventional methods, are attributed to the integration of source-channel coding, adaptive transmission techniques, and a focus on semantically relevant information. These design features collectively improve PSNR performance while substantially reducing communication overhead, thereby addressing contemporary intelligent parking systems’ rigorous requirements.

Figure 5(c) illustrates the simulated training and testing loss levels of the proposed model, examining their relationship with overall performance and their variation across epochs. The simulation results reveal a consistent reduction in both training and testing loss as the number of epochs increases, indicating that the model effectively learns and adapts to the underlying data patterns over time. This trend emphasizes the significance of monitoring loss metrics throughout the training process, as a declining loss typically reflects improved model accuracy and enhanced generalization capabilities. Furthermore, the narrow gap between training and testing loss suggests that the model generalizes correctly to unseen data while mitigating the risk of overfitting to the training dataset. This consistency underscores the robustness of the training process and its capacity to converge toward an optimal solution.

7. Conclusions

The rapid evolution of emerging technologies has highlighted the limitations of traditional network architectures, which are typically designed for specific applications or services. These conventional systems are not only costly but also insufficient for meeting modern applications’ dynamic and diverse requirements. As technological advancements accelerate, network infrastructure demands continue to grow, necessitating the development of multifunctional, scalable, and cost-efficient solutions. To address the increasing need for high-performance wireless services, dense heterogeneous and cooperative networks have become integral to telecom evolution. In response to these challenges, the H-RAN architecture has emerged as a centralized platform designed to integrate diverse networks and technologies into a unified framework. This architecture promotes extensive collaboration across multiple domains, enabling seamless interoperability and enhanced network performance. However, the exponential growth in data generation, driven largely by the proliferation of SRUs and IoT devices, poses significant challenges related to communication overhead. These challenges include increased latency, excessive bandwidth consumption, and inefficient data transmission. As a result, there is a pressing need for innovative technologies capable of addressing these issues. Integration of SRUs with SMTL cooperation represents a comprehensive and integrative approach aimed at improving network responsiveness. This collaborative framework leverages complementary technologies to optimize performance, particularly in decision-making processes within parking systems, while simultaneously mitigating communication overhead. Furthermore, by distributing data collection, processing, and decision-making tasks across edge, fog, and cloud layers, the H-RAN-based parking system alleviates the computational burden on individual network nodes. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed approach achieves high accuracy within a reduced timeframe while reducing communication overhead by more than 50% compared to conventional methods. This improvement not only yields significant cost savings but also enhances overall network performance, underscoring the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed solution in modern urban environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Rafid.I Abd, KWANG SOOM KIN and Daniel J. Findley.; methodology, Rafid.I Abd, and KWANG SOOM KIN; software, Rafid.I Abd, KWANG SOOM KIN and Daniel J. Findley.; validation, Rafid.I Abd, KWANG SOOM KIN.; formal analysis, Rafid.I Abd, KWANG SOOM KIN, and Daniel J. Findley.; Investigation, Rafid.I Abd, and Daniel J. Findley.; resources, Rafid.I Abd, and KWANG SOOM KIN.; data curation, Rafid.I Abd, KWANG SOOM KIN and Daniel J. Findley.; writing—original draft preparation, Rafid.I Abd, KWANG SOOM KIN and Daniel J. Findley.; writing—review and editing, Rafid.I Abd, KWANG SOOM KIN, and Daniel J. Findley.; Visualization, KWANG SOOM KIN.; Supervision, KWANG SOOM KIN.; Project administration, KWANG SOOM KIN.; Funding Acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00397216, Development of the Upper-mid Band Extreme Massive MIMO (E-MIMO), 30%, IITP-2025-RS-2024-00428780, 6G·Cloud Research and Education Open Hub, 20%) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2022-NR070834, Augmented Cognition Meta-Communications Research Center, 50%).

Acknowledgments

This study employed the following methodologies and tools:

1- Dataset and Training Framework:

The Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) framework was trained and validated using the CNRPark-EXT parking slot dataset [51,52,53].

2- Object Detection:

YOLOv5 [42] was implemented for the identification of Regions of Interest (ROIs) within the dataset.

3- Simulation Framework:

The proposed model's performance was evaluated through comprehensive simulations utilizing:

OpenAI [54] for reinforcement learning environments

TensorFlow [55] and PyTorch [56] for deep learning implementations

Python [57] as the primary programming language

Simulation of Urban Mobility (SUMO) [58] for traffic modeling

Adam optimizer [59] for neural network optimization

4- User Interface:

A web-based interface was developed using Python with Flask [57] to provide accessible interaction with the system.

Note: During manuscript preparation, AI-assisted tools (including ChatGPT, DeepSeek, and Wordtune) were utilized exclusively for grammatical verification and readability improvement. All conceptual content and technical implementations remain the original work of the authors.

References

- Rafid I. Abd, Daniel J. Findley, and Kwang Soon Kim, "Hydra-RAN Perceptual Networks Architecture: Dual-Functional Communications and Sensing Networks for 6G and Beyond," IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 30507–30526, Dec. 2023.

- Rafid I. Abd, Daniel J. Findley, and Kwang Soon Kim, "Hydra Radio Access Network (H-RAN): Multi-Functional Communications and Sensing Networks, Initial Access Implementation, Task-1 Approach," IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 76532 - 76554, May 2024.

- Rafid I. Abd, Daniel J. Findley, and Kwang Soon Kim, "Hydra Radio Access Network (H-RAN): Multi-Functional Communications and Sensing Networks, Initial Access Implementation, Task-2 Approach," IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 13606 - 13627, Jan. 2025.

- Rafid I. Abd, and Kwang Soon Kim, "Hydra Radio Access Network (H-RAN): Multi-Functional Communications and Sensing Networks, Adaptive Power Control, and Interference Coordination,” in Proc. IEEE 15th International Conference, Conf. Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC). Jan. 2025, pp. 11-14.

- Rafid I. Abd, and Kwang Soon Kim, "Hydra Radio Access Network (H-RAN): Multi-Functional Communications and Sensing Networks, Collaboration-Based SRU Switching,” in Proc. IEEE 15th International Conference, Conf. Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC). Jan. 2025, pp. 11-14.

- Rafid I. Abd, and Kwang Soon Kim, "Hydra Radio Access Network (H-RAN): Accurate Estimation of Reflection Configurations (RCs) for Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces (RIS),” in Proc. IEEE 15th International Conference, Conf. Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC). Jan. 2025, pp. 11-14.

- Rafid I. Abd, and Kwang Soon Kim, "Hydra-RAN: Multi-Functional Communications and Sensing Networks for Collaborative-Based User Status,” in Proc. IEEE 14th International Conference, Conf. Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC). Jan. 2025, pp. 11-14.

- Rafid I. Abd, and Kwang Soon Kim, "Hydra Radio Access Network (H-RAN): Adaptive Environment-Aware Power Codebook,” in Proc. IEEE 15th International Conference, Conf. Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC). Jan. 2025, pp. 11-14.

- Rafid, and Kwang Soon Kim, " Hydra Radio Access Network (H-RAN): Adaptive Environment-Aware Power Codebook,” in Proc. 2024 Korea Communications Society Fall Academic Conference. [Online]. Available: https:// https://www.dbpia.co.kr/pdf/pdfAiChatView.do?nodeId=NODE12034699.

- Rafid I. Abd, and Kwang Soon Kim, "Continuous Steering Backups of NLoS-Assisted mm Wave Networks to Avoid Blocking,” in Proc. IEEE 14th International Conference, Conf. Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC). Oct. 2023, pp. 11-13.

- Rafid I. Abd, and Kwang Soon Kim, " Protocol Solutions for IEEE 802.11bd by Enhancing IEEE 802.11ad to Address Common. Technical Challenges Associated With mmWave-Based V2X", IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp.100646 - 100664, Sept. 2022.

- .. K. Gunasekaran, V. Vinoth Kumar, A. C. Kaladevi, T. R. Mahesh, C. Rohith Bhat, and Krishnamoorthy Venkatesan, "Smart Decision-Making and Communication Strategy in Industrial Internet of Things", IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 28222 - 28235, Mar. 2023.

- A. Hakiri, A. Gokhale, S.Ben Yahia, and N. Melloul, "A comprehensive survey on digital twin for future networks and emerging Internet of Things industry,” Computer Networks, vol. 244, May 2024, 110350.

- J.Wu, C. Wu a, Y. Lin, T. Yoshinaga, L. Zhong, X. Chen, and Y. Ji, “Semantic segmentation-based semantic communication system for image transmission,” Digital Commun. Networks, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 519-527, Jun. 2024.

- H. Yoo, L. Dai, S. Kim, and Chan-Byoung Chae, "On the Role of ViT and CNN in Semantic Communications: Analysis and Prototype Validation," IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 2169-3536, July. 2023.

- S. Tang, Q. Yang, L. Fan, X. Lei, A. Nallanathan, and George K. Karagiannidis, "Contrastive Learning-Based Semantic Communications", IEEE Transactions on Communications, vol. 72, no. 10, pp. 6328 - 6343, May 2024.

- J. Xu, T. Tung, B. Ai, W. Chen, Y. Sun, and D.Gündüz, "Deep Joint Source-Channel Coding for Semantic Communications", IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 61, no. 11, pp. 42 - 48, Nov. 2023.

- J. Park, Y. Oh, S. Kim, and Y.Jeon, "Joint Source-Channel Coding for Channel-Adaptive Digital Semantic Communications", IEEE Transactions on Cognitive Communications and Networking, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 75 - 89, July 2024.

- H. Zhou, Y. Deng, X, Liu, N, Pappas; Arumugam Nallanathan, "Goal-Oriented Semantic Communications for 6G Networks", IEEE Inter. of Things Magazine, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 104 - 110, Sep. 2024.

- D. Gund ¨ uz, Z. Qin, I. E. Aguerri, H. S. Dhillon, Z. Yang, A. Yener, ¨K. K. Wong, and C.-B. Chae, “Beyond transmitting bits: Context, semantics, and task-oriented communications,” IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun., vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 5–41, Nov. 2022.

- H. Yuan, W. Xu, Y. Wang, and X. Wang, “Channel adaptive dl based joint source-channel coding without a prior knowledge,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.15183, 2023.

- T. Tung, D. B. Kurka, M. Jankowski, and D. Gündüz, “DeepJSCC-Q: Constellation constrained deep joint source-channel coding,” IEEE J. Sel. Areas Inf. Theory, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 720–731, Dec. 2022.

- H. Wu, Y. Shao; C. Bian, K. Mikolajczyk, and D. Gündüz, “Deep Joint Source-Channel Coding for Adaptive Image Transmission Over MIMO Channels,” IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, vol. 23, no. 10, pp. 15002 - 15017, Oct. 2024.

- Mathias Gabriel Diaz Ogás , Ramon Fabregat, and Silvana Aciar,"Survey of Smart Parking Systems", Journals Applied Sciences Vo. 10, no. 11, May 2020. 10.3390/app10113872.

- F. Al-Turjman and A. Malekloo, “Smart parking in IoT-enabled cities: Asurvey,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 49, Aug. 2019, Art. no. 101608.

- R. M. Nieto, Á. García-Martín, A. G. Hauptmann, and J. M. Martínez, “Automatic vacant parking places management system using multicam era vehicle detection,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 1069–1080, Mar. 2019.

- S. Nurullayev and S.-W. Lee, “Generalized parking occupancy analysis based on dilated convolutional neural network,” Sensors, vol. 19, no. 2, p. 277, 2019.

- F. Bock, S. Di Martino, and A. Origlia, “Smart parking: Using a crowd of taxis to sense on-street parking space availability,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 496–508, Feb. 2020.

- C.-F. Peng, J.-W. Hsieh, S.-W. Leu, and C.-H. Chuang, “Drone-based vacant parking space detection,” in Proc. 32nd Int. Conf. Adv. Inf. Netw. Appl. Workshops (WAINA), May 2018, pp. 618–622.

- S. Sarkar, M. W. Totaro, and K. Elgazzar, “Intelligent drone-based surveillance: Application to parking lot monitoring and detection,” Proc. SPIE, vol. 11021, May 2019, Art. no. 1102104.

- T. Lin, H. Rivano, and F. Le Mouël, “A survey of smart parking solutions,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 3229–3253, Dec. 2017.

- Y. Jeon, H.-I. Ju, and S. Yoon, “Design of an LPWAN communication module based on the secure element for smart parking application,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Consum. Electron. (ICCE), Jan. 2018, pp. 1–2.

- L. Lou, J. Zhang, Y. Xiong, and Y. Jin, “An improved roadside parking space occupancy detection method based on magnetic sensors and wireless signal strength,” Sensors, vol. 19, no. 10, p. 2348, 2019.

- Piccialli, F., Giampaolo, F., Prezioso, E., Crisci, D., Cuomo, S.: Predictive analytics for smart parking: a deep learning approach in forecasting of iot data. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. TOIT 21(3), 1–21 (2021).

- G. Ali,T. Ali, M Irfan, U Draz, M. Sohail, A. Glowacz, M. Sulowicz, R. Mielnik ,Z. Bin Faheem and C. Martis, "IoT Based Smart Parking System Using Deep Long Short Memory Network",MDPI, vol. 9, no. 10, Oct. 2020.

- R. Ke, Y. Zhuang, Z. Pu, Y. Wang, "A Smart, Efficient, and Reliable Parking Surveillance System with Edge Artificial Intelligence on IoT Devices", IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 22, no. 8, pp. 890-901, Aug. 2021.

- K. Sattar Awaisi, A. Abbas, H. Ali Khattak, A. Ahmad, M. Ali, and A. Khalid “Deep reinforcement learning approach towards a smart parking architecture,” Cluster Computing., vol. 29, pp. 255–266, May 2022.

- Thanki, R.M., Kothari, A.M., “Morphological image processing. In: Digital Image Processing using SCILAB,”, pp. 99–113. Springer 2019.

- A. Aditya, S. Anwarul, R.Tanwar, S. Krishna Vamsi Koneru“ An IoT assisted Intelligent Parking System (IPS) for Smart Cities,” Procedia Computer Science., vol. 218, 2023, Pages 1045-1054.

- X. Huang, L. Shi, and J. A. K. Suykens, “Solution path for pin-SVM classifiers with positive and negative values,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., vol. 28, no. 7, pp. 1584–1593, Jul. 2017.

- H. Wang and Y. Shao, “Fast truncated Huber loss SVM for large scale classification,” Knowl.-Based. Syst. vol. 26, pp. 1–17, Jan. 2023.

- J. Hou, B. You, J. Xu, T. Wang, and M. Cao, “Surface defect detection of preform based on improved YOLOv5,” Appl. Sci., vol. 13, no. 13, p. 7860, Jul. 2023.

- Y. Shen, F. Zhang, Di Liu, W. Pu b, and Q. Zhang “Manhattan-distance IOU loss for fast and accurate bounding box regression and object detection,” Neurocomputing, vol. 500, pp. 99-114, Aug. 2022.

- J. Xing, Y. Liu, and G.-Z. Zhang, “Improved YOLOV5-based UAV pavement crack detection,” IEEE Sensors J., vol. 23, no. 14, pp. 15901–15909, Jul. 2023.

- M. Noto and H. Sato, A method for the shortest path search by extended Dijkstra algorithm, in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Syst., Man Cybern., Nashville, TN, USA, Oct. 2000, pp. 23162320. [CrossRef]

- W. Shakir, A. Mahdi, H. Hamdan, J. Charafeddine, H. Satai, and R. Akrache, “Novel Approximate Distribution of the Generalized Turbulence Channels for MIMO FSO Communications,” IEEE Photonics Journal, vol. 16, no. 4, ASN. 7302715, June 2024.

- Y. Song, J. Ou, W. Pedrycz, X. Wang, and L. Xing, "Robust earth observation satellite scheduling with uncertainty of cloud coverage", IEEE Trans. on Syst., Man, and Cyb. Syst., vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 2576 - 2589, Jan. 2024.

- H. Sun, J. Wang, D. Yong, M. Qin, and N.Zhang, "Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Computation Offloading for Mobile Edge Computing in 6G", IEEE Trans. on on Cons. Electr., vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 2576 - 2589, August 2024.

- Q. Luo, T. H. Luan, W. Shi, and P. Fan, “Deep reinforcement learning based computation offloading and trajectory planning for multi-UAV cooperative target search,” IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun., vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 504–520, Feb. 2023.

- N. Zhao, Z. Ye, Y. Pei, Y.-C. Liang, and D. Niyato, “Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for task offloading in UAV-assisted mobile edge computing,” IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun., vol. 21, no. 9, pp. 6949–6960, Sep. 2022.

- J. Chen et al., “Deep reinforcement learning based resource allocation in multi-UAV-aided MEC networks,” IEEE Trans. Commun., vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 296–309, Jan. 2023.

- . H. Wang a, H. Zhang a, and W. Li b, "Sparse and robust support vector machine with capped squared loss for large-scale pattern classification", ScienceDireet, Vo. 153, Sep. 2024, 110544.

- Amato, G., Carrara, F., Falchi, F., Gennaro, C., Meghini, C., and Vairo, C., "Deep learning for decentralized parking lot occupancy detection”, Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 72, pp. 327-334, Apr. 2017. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- G. Brockman et al., “OpenAI gym,” 2016, arXiv:1606.01540. [Online]. Available: [1606.01540] OpenAI Gym (arxiv.org).

- M. Abadi et al., “Tensorflow: Large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous distributed systems,” in Proc. Conf. Operating Syst. Des. Implementation, 2016, pp. 265–283.

- A.Paszkeetal., “Automatic differentiation in PyTorch,” in Proc. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. Workshop Autodiff Submission, Oct. 2017.

- The Matplotlib development team. Matplotlib: Visualization with Python. Accessed November 24, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://://matplotlib.org/.

- X.Ma,X.Hu, T.Weber, andD. Schramm, “Evaluationof accuracy of trafficflowgeneration in sumo,”AppliedSciences, vol. 11, no. 6, p.2584, 2021.

- D. P. Kingma and J. Ba, “Adam: A Method for Stochastic Op timization,” arXiv:1412.6980 [cs], Jan. 2017. arXiv: 1412.6980.

- T. Richardson and S. Kudekar, “Design of low-density parity-check codes for 5G new radio,” IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 28–34, 2018.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).