Submitted:

04 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

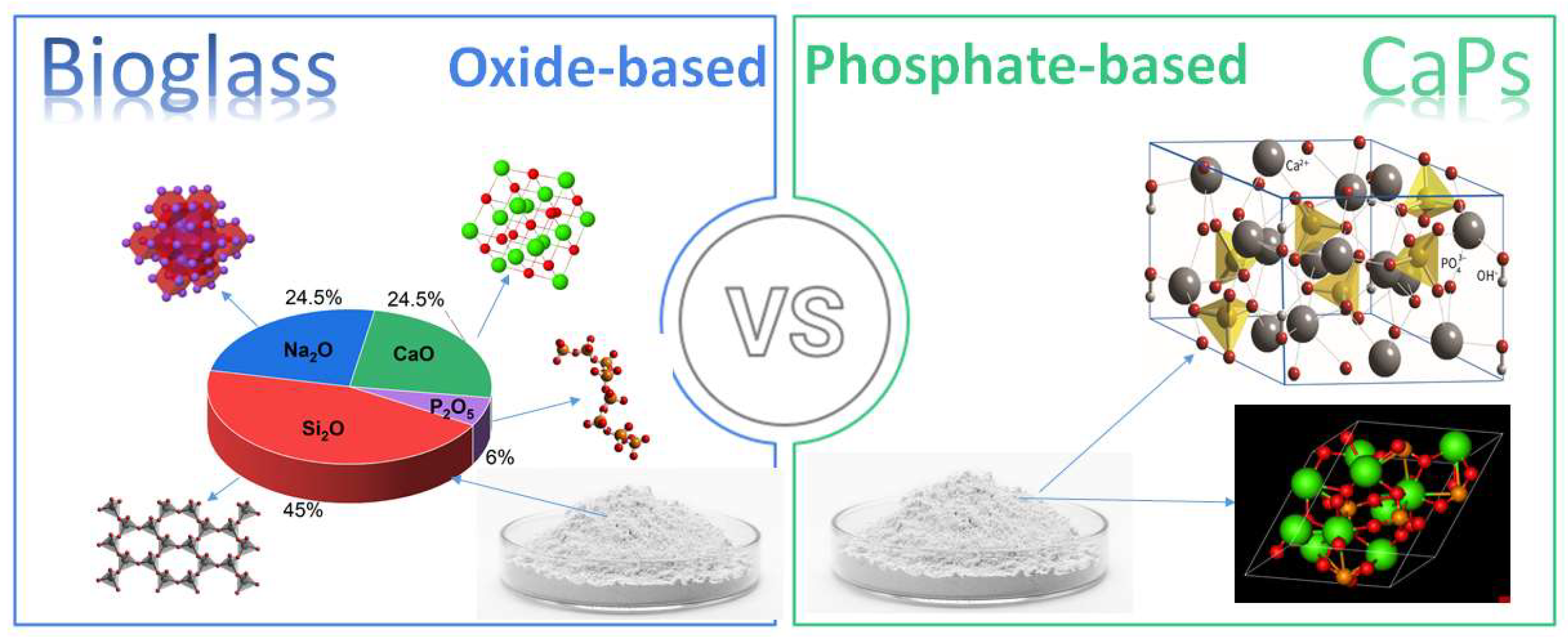

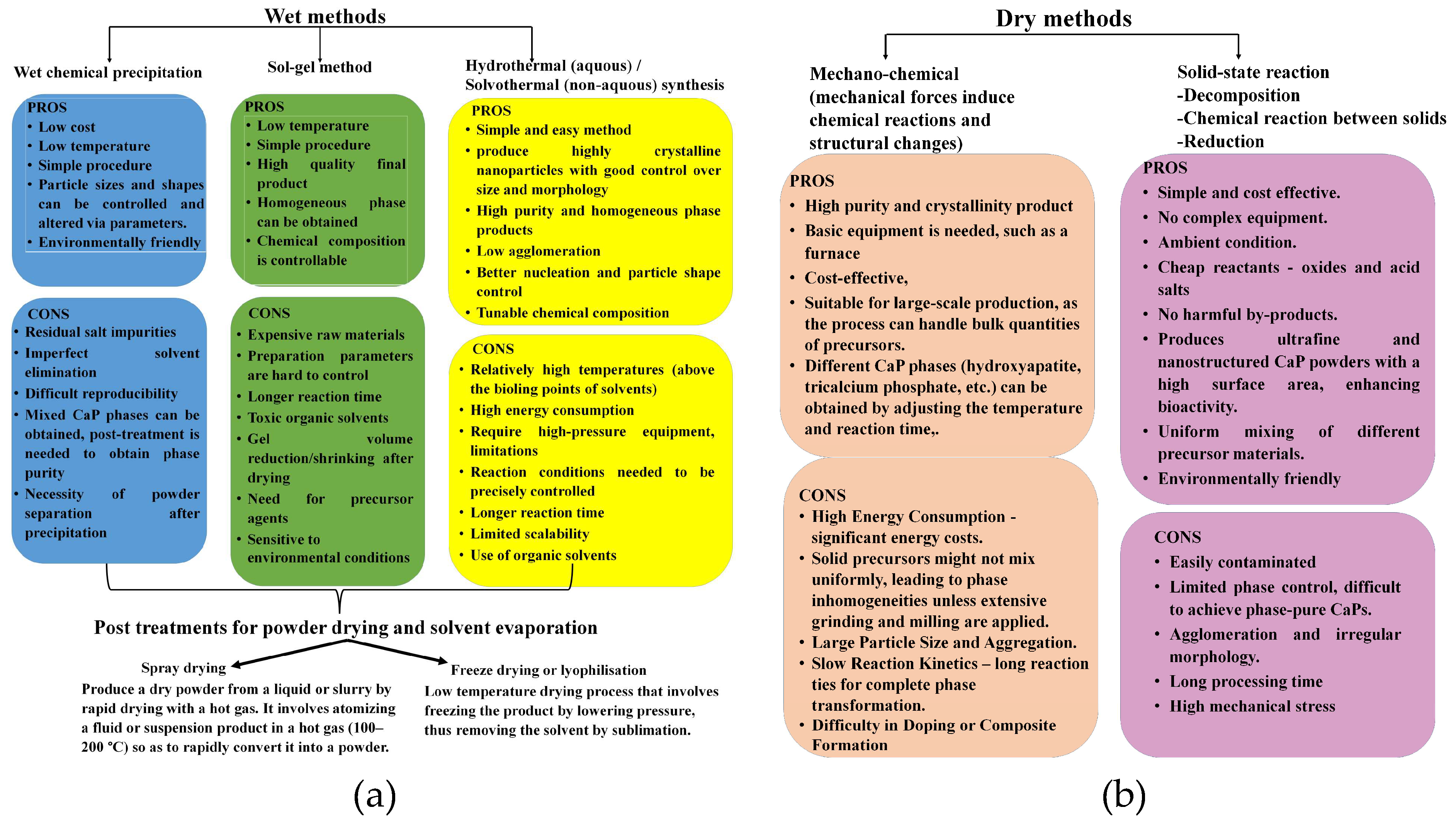

2. Calcium Phosphate-Based Bioactive Ceramics

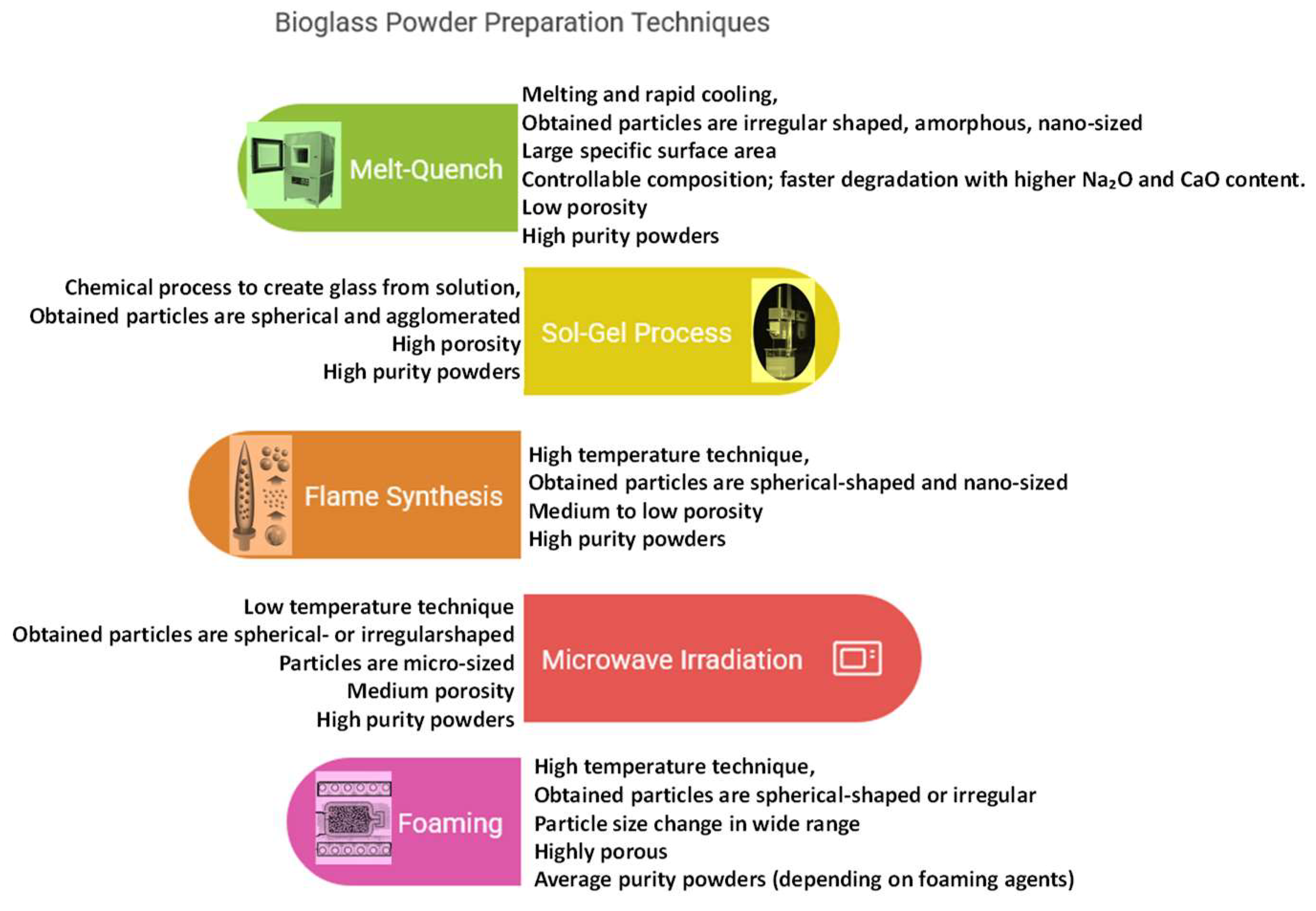

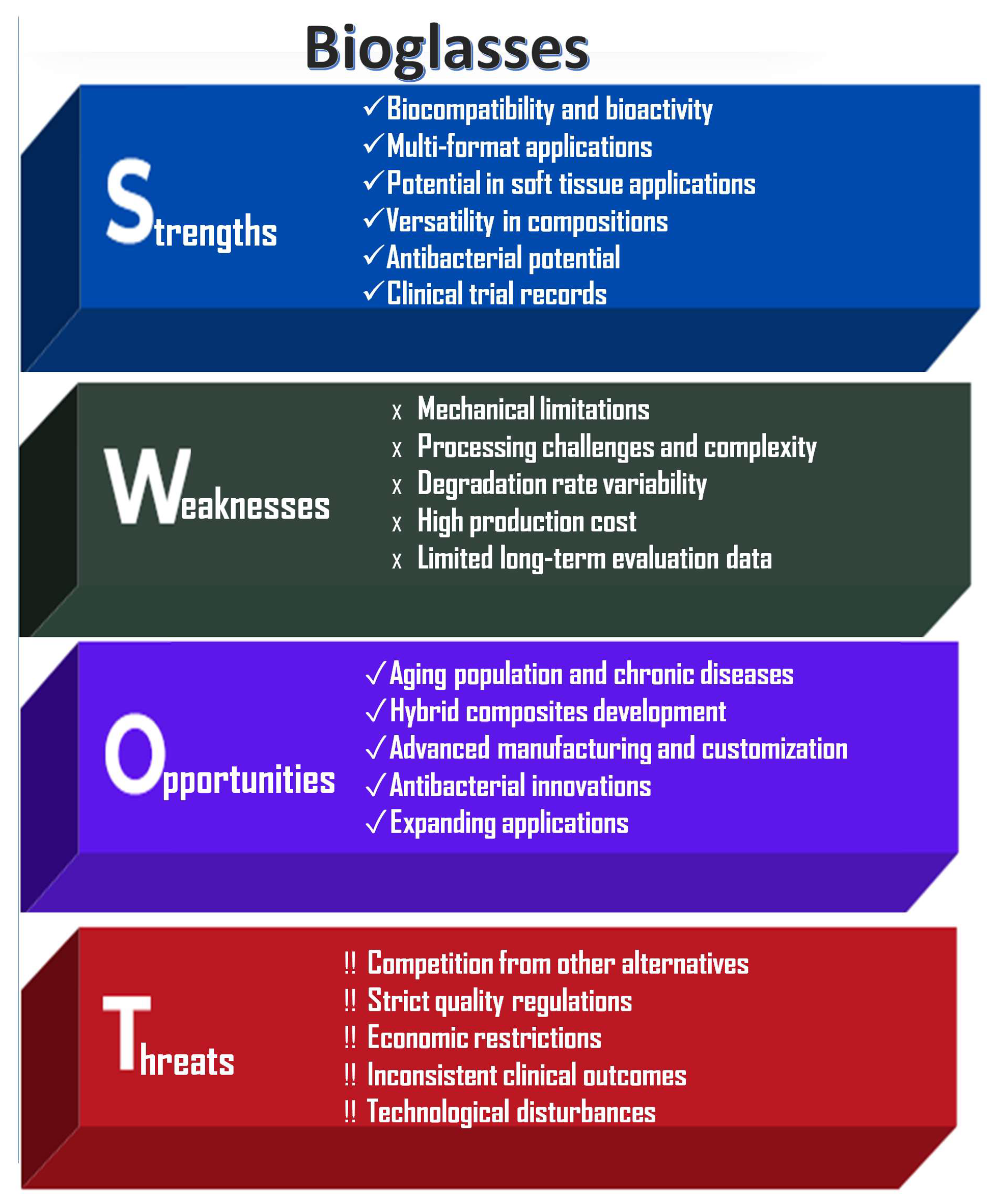

3. Bioglasses

4. Applications of Bioactive Ceramics

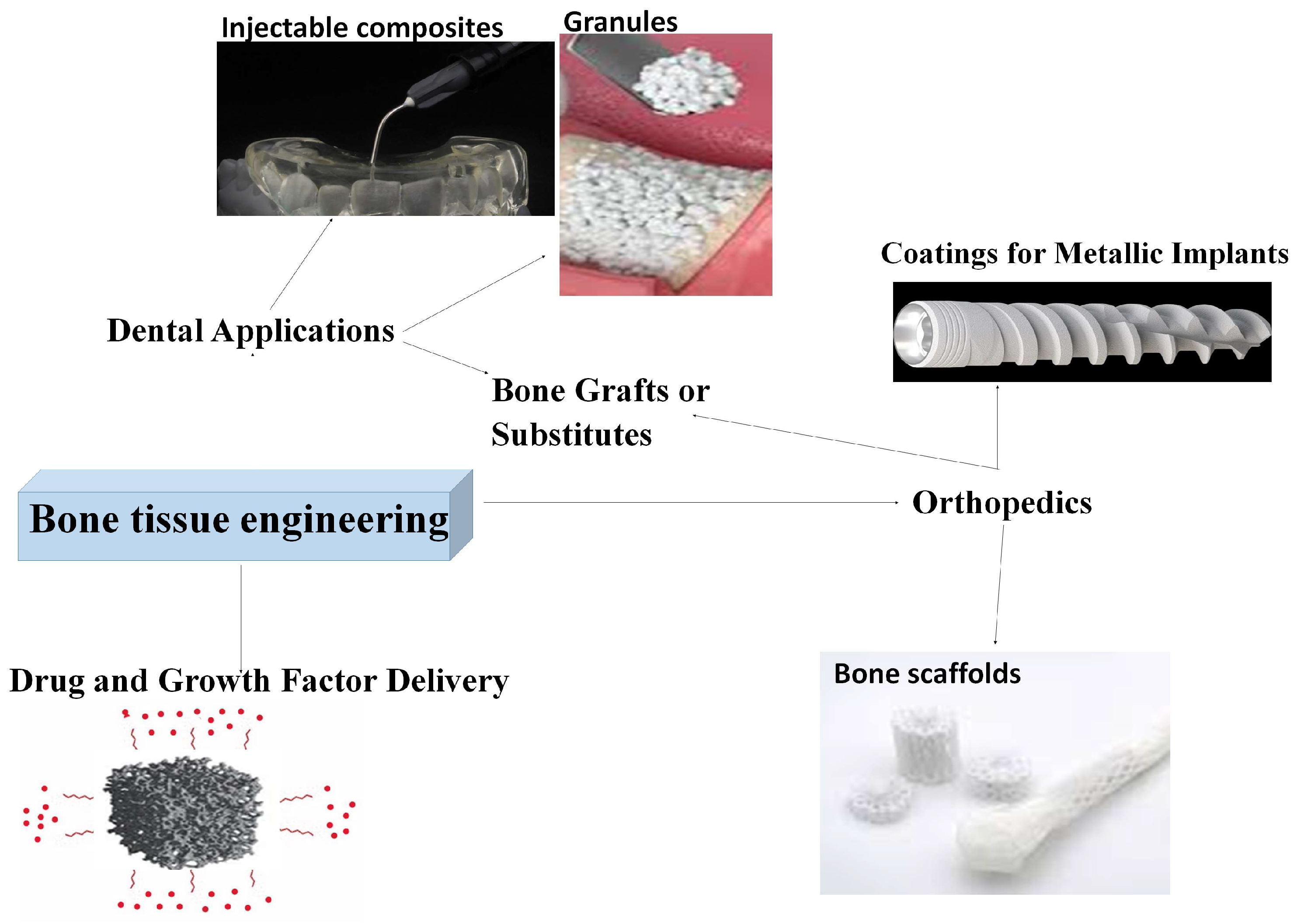

4.1. Bioglasses and Calcium Phosphates in Bone Tissue Engineering (BTE)

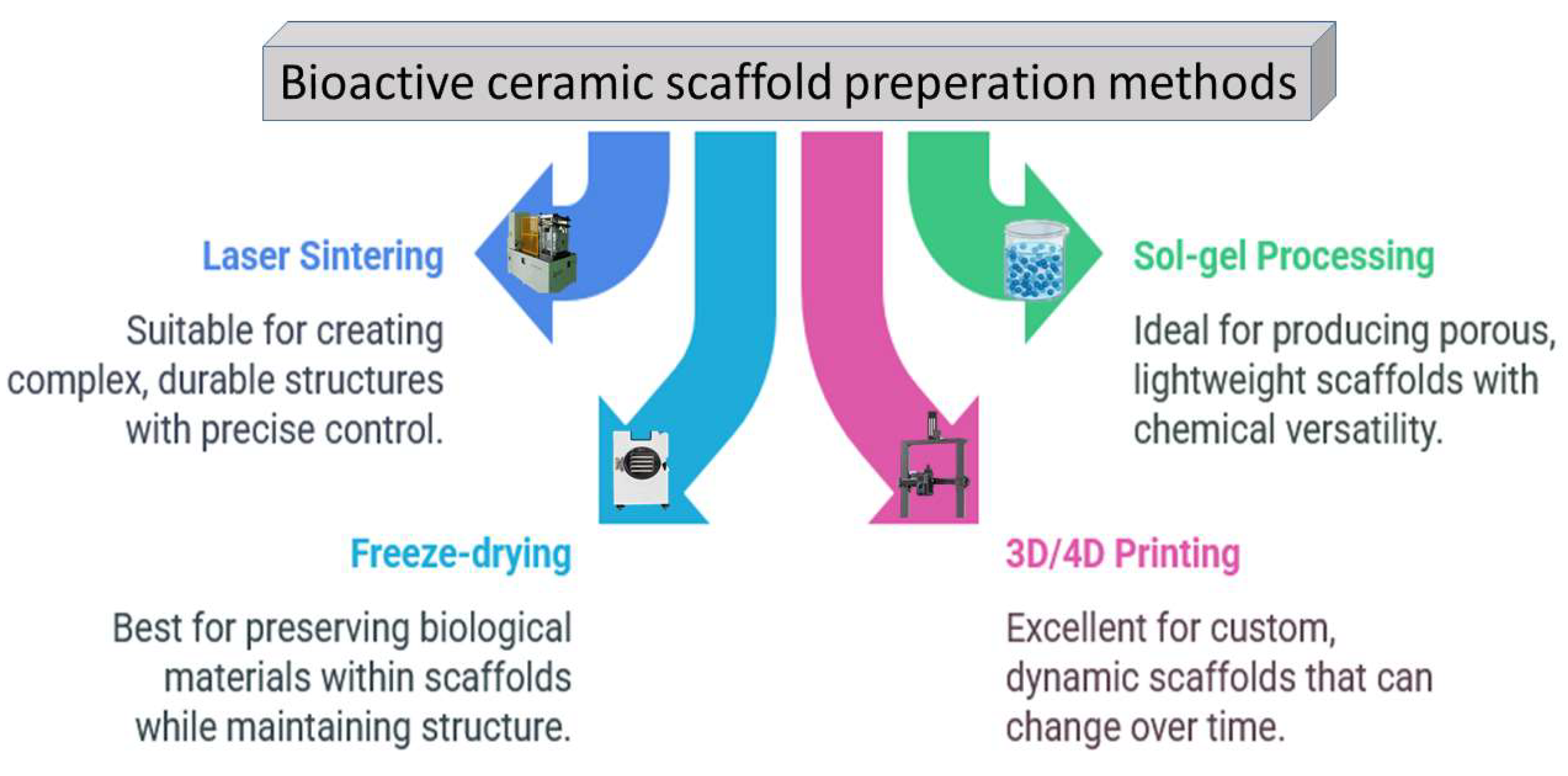

4.1.1. Scaffold Materials and Bone Substitutes

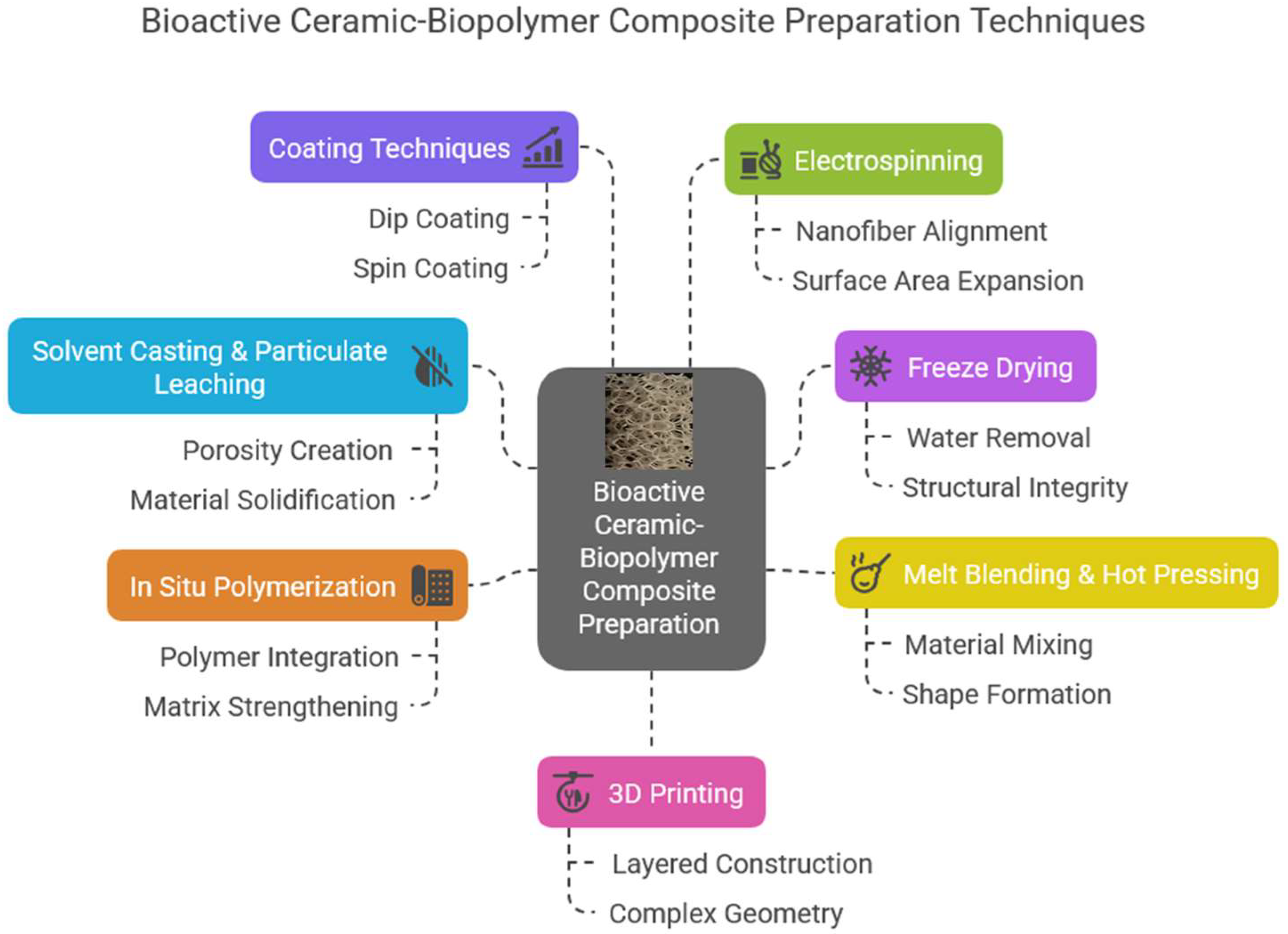

4.1.2. Bioactive Ceramic-Polymer Composites

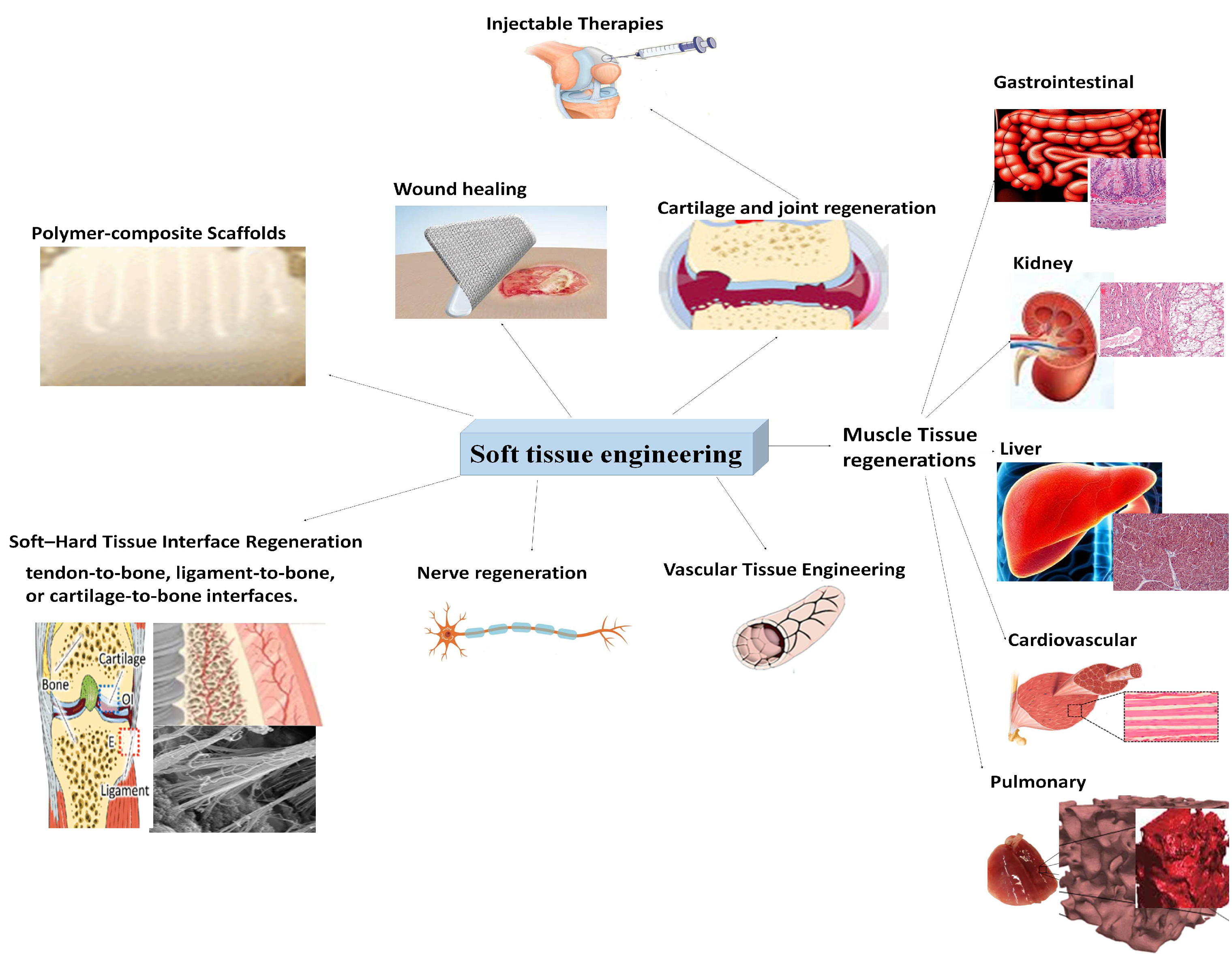

4.2. Bioglasses and Calcium Phosphate Derivatives in Soft Tissue Engineering (STE)

4.3. Bioglasses and Calcium Phosphate Derivatives as Drug Delivery Matrices

4.4. Coatings on Metallic Implants to Improve Osseointegration

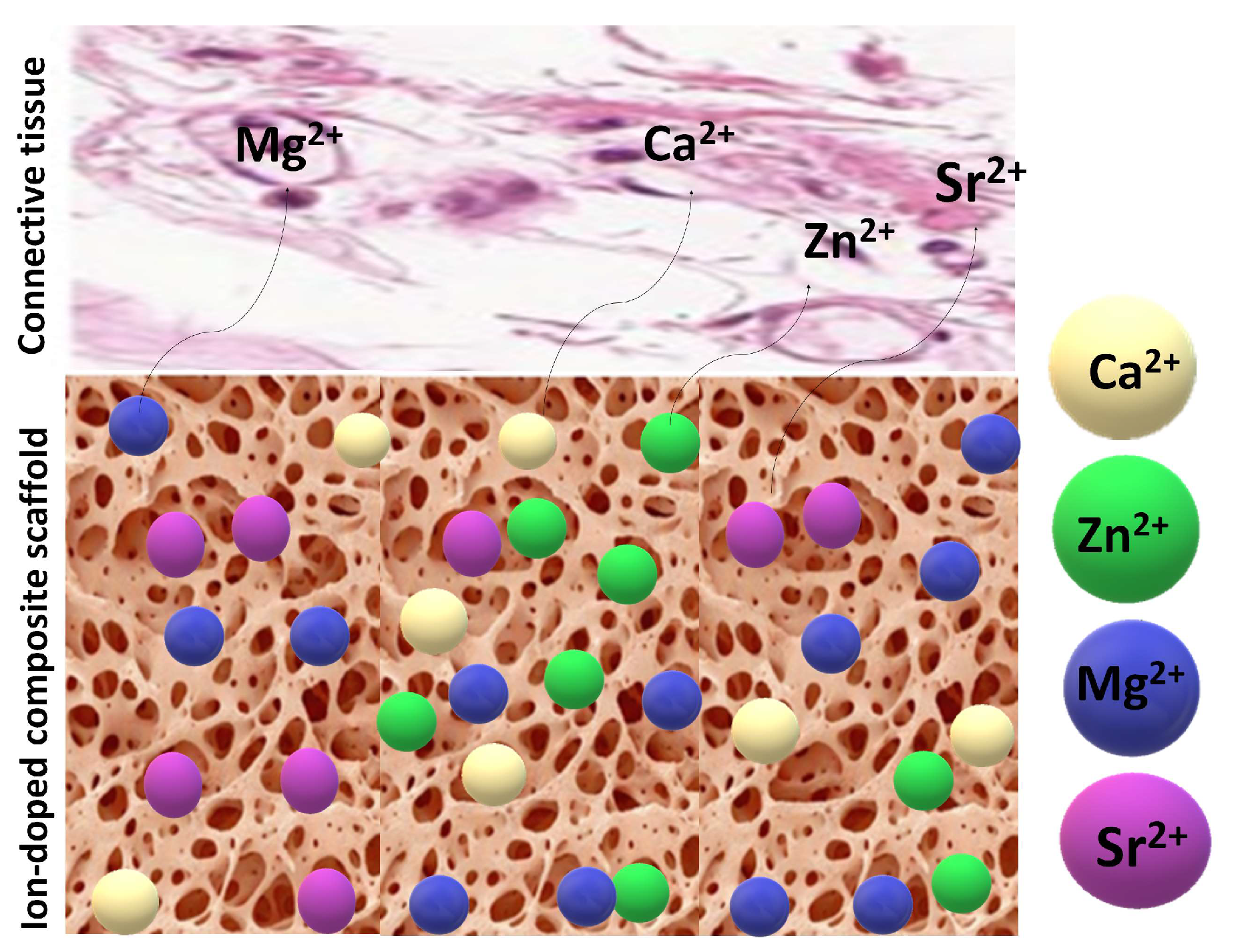

4.5. Effect of Bioactive Element Doping of Bioglasses and CaP Derivatives

| Ions | Osteoblast Activity | Osteoclast Activity | Energy Metabolism |

| Sr²⁺ |

|

|

|

| Mg²⁺ |

|

|

|

| Zn²⁺ |

|

|

|

| Si⁴⁺ |

|

|

|

| Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ |

|

|

|

| Co²⁺ |

|

|

|

| Cu²⁺ |

|

|

|

| Ag |

|

|

|

| 1.The Wnt/β-catenin pathway comprises a family of proteins that play critical roles in embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis. 2.OPG: Osteoprotegerin. 3.MAPK: Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases. 4.CaSR: Calcium-Sensing Receptor. 5Runx2: a gene that plays a cell proliferation regulatory role in cell cycle entry and exit in osteoblasts, as well as endothelial cells. 6RANKL: (Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Ligand) an apoptosis regulator gene, a binding partner of osteoprotegerin (OPG), a ligand for the receptor RANK and controls cell proliferation. 7.ATP: Adenosine triphosphate. 8. TGF-β: Transforming growth factor beta, a cytokine, which regulates cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, 9.BMP: Bone morphogenic protein. 10.VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor is a potent angiogenic factor. It is a signalling protein that promotes the growth of new blood vessels. | |||

5. Biodegradability and Clinical Evaluations of the Different Bioactive Ceramics and Bioglasses as Well as Their Composites

6. Challenges

- Mechanical, chemical, and biological variability in final products, influenced by bioceramic type, biopolymer matrices, and preparation methods.

- Precise control over scaffold vascularization, degradation rates, and manufacturing standardization.

- Reproducibility in bioceramic distribution within polymer matrices.

7. Future Perspectives

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernandes, H.R.; Gaddam, A.; Rebelo, A.; Brazete, D.; Stan, G.E.; Ferreira, J.M.F. Bioactive Glasses and Glass-Ceramics for Healthcare Applications in Bone Regeneration and Tissue Engineering. Materials 2018, 11, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baino, F.; Novajra, G.; Vitale-Brovarone, C. Bioceramics and Scaffolds: A Winning Combination for Tissue Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2015, 3, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedir, T.; Altan, E.; Aranci-Ciftci, K.; Gunduz, O. Bioceramics. In Biomaterials and Tissue Engineering. Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine; Gunduz, O., Egles, C., Pérez, R.A., Ficai, D., Ustundag, C.B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2023; Volume 74, pp. 175–203. [Google Scholar]

- Raucci, M.G.; Giugliano, D.; Ambrosio, L. Fundamental Properties of Bioceramics and Biocomposites. In Handbook of Bioceramics and Biocomposites; Antoniac, I., Ed.; Springer: Cham, 2015; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Coughlan, A.; Laffir, F.R.; Pradhan, D.; Mellott, N.P. ; Wren AW, Investigating the mechanical durability of bioactive glasses as a function of structure solubility incubation time, J. Non-Cryst. Sol. 2013, 380, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baino, F.; Fiume, E. Elastic Mechanical Properties of 45S5-Based Bioactive Glass–Ceramic Scaffolds. Materials 2019, 12, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Hernandez, D.G.; Genetos, D.C.; Working, D.M.; Murphy, K.C.; Leach, J.K. Ceramic Identity Contributes to Mechanical Properties and Osteoblast Behavior on Macroporous Composite Scaffolds. J. Funct. Biomater. 2012, 3, 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Souza, M.T.; Li, W.; Schubert, D.W.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Roether, J.A. Bioactive Glass-Biopolymer Composites. In Handbook of Bioceramics and Biocomposites; Springer: Cham, 2025; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Niemelä, T.; Kellomäki, M. 11 - Bioactive glass and biodegradable polymer composites. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Biomaterials, Bioactive Glasses; Heimo, O.Y., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing, 2011; pp. 2274–245. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni, E.; Iaquinta, M.R.; Lanzillotti, C.; Mazziotta, C.; Maritati, M.; Montesi, M.; Sprio, S.; Tampieri, A.; Tognon, M.; Martini, F. Bioactive Materials for Soft Tissue Repair. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 9613787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, T.; Mesgar, A.S.; Mohammadi, Z. Bioactive Glasses: A Promising Therapeutic Ion Release Strategy for Enhancing Wound Healing. ACS Biomat. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 5399–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ege, D.; Zheng, K.; Boccaccini, A.R. Borate Bioactive Glasses (BBG): Bone Regeneration, Wound Healing Applications, and Future Directions. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, A.; Montazerian, M.; Mauro, J.C. Modern definition of bioactive glasses and glass-ceramics. J Non-Cryst. Sol. 2023, 608, 122228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos, D. ; Vallet-Regí,, M. Bioceramics for drug delivery Acta Materialia 2013, 61, 890. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.-L.; Fang, W.; Huang, B.-R.; Wang, Y.-H.; Dong, G.-C.; Lee, T.-M. Bioactive Glass as a Nanoporous Drug Delivery System for Teicoplanin. Appl Sci 2020, 10, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, A.; Indurkar, A.; Locs, J.; Haugen, H.J.; Loca, D. Calcium Phosphates: A Key to Next-Generation In Vitro Bone Modeling. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024 13, e2401307. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.G.; Briglia, M.; Zammuto, V.; Morganti, D.; Faggio, C.; Impellitteri, F.; Multisanti, C.R.; Graziano, A.C.E. Innovation in Osteogenesis Activation: Role of Marine-Derived Materials in Bone Regeneration. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klenke, F.M.; Siebenrock, K.A. Osteology in Orthopedics – Bone Repair, Bone Grafts, and Bone Graft Substitutes. In Encyclopedia of Bone Biology; Mone, Z., Ed.; Academic Press, 2014; pp. 778–792. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre, N.; Simões, G.; Martinho Lopes, A.; Guerra Guimarães, T.; Lopes, B.; Sousa, P.; et al. Biomechanical Basis of Bone Fracture and Fracture Osteosynthesis in Small Animals. Biomechanical Insights into Osteoporosis; IntechOpen, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasheva, F.; Adilova, L.; Dyussenbinov, A.; Yernaimanova, B.; Abilev, M.; Akilbekova, D. Optimizing scaffold pore size for tissue engineering: insights across various tissue types. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2024, 12, 1444986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furko, M.; Horváth, Z.E.; Mihály, J.; Balázsi, K.; Balázsi, C. Comparison of the Morphological and Structural Characteristic of Bioresorbable and Biocompatible Hydroxyapatite-Loaded Biopolymer Composites. Nanomaterials. 2021, 11, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheima, A.M.; Abdul-Rasool, A.A.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Zaidan, H.K.; Athair, D.M.; Mohammed, S.H.; Ehsan kianfar, E. Nano bioceramics: Properties, applications, hydroxyapatite, nanohydroxyapatite and drug delivery. CSCEE 2024, 10, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, M.; He, J. A review of biomimetic scaffolds for bone regeneration: Toward a cell-free strategy. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2020, 15, e10206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, H.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, Y. Calcium Phosphate-Based Nanomaterials: Preparation, Multifunction, and Application for Bone Tissue Engineering. Molecules 2023, 5, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, S.; Birgani, Z.T.; Habibovic, P. ; Biomaterial-induced pathway modulation for bone regeneration. Biomaterials 2022, 283, 121431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandayil, J.T.; Boetti, N.G.; Janner, D. Advancements in Biomedical Applications of Calcium Phosphate Glass and Glass-Based Devices—A Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawsar, M.D.; Hossain, M.d.S.; Alam, M.d.K.; Bahadur, N.M.; Shaikh, M.d.A.A.; Ahmed, S. Synthesis of pure and doped nano-calcium phosphates using different conventional methods for biomedical applications: a review. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 3376–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Seles, M.A.; Rajan Mariappan, R. Role of bioglass derivatives in tissue regeneration and repair: A review. RAMS 2023, 62, 20220318. [Google Scholar]

- Vizureanu, P.; Baltatu, M.; Sandu, A.; Achitei, D.; Negris, D.D.B.; Perju, M. New Trends in Bioactive Glasses for Bone Tissue: A Review. In book: Current Concepts in Dental Implantology - From Science to Clinical Research, 2021, Corpus ID: 244581791.

- Rahaman, M.N.; Day, D.E.; Bal, B.S.; Fu, Q.; Jung, S.B.; Bonewald, L.F.; Tomsia, A.P. Bioactive glass in tissue engineering. Acta Biomater 2011, 7, 2355–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawar, V.; Shinde, V. Bioglass and hybrid bioactive material: A review on the fabrication, therapeutic potential and applications in wound healing. Hybrid Advances 2024, 6, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, M.; Maximov, O.-C.; Craciun, L.; Ficai, D.; Ficai, A.; Andronescu, E. Bioactive Glass—An Extensive Study of the Preparation and Coating Methods. Coatings 2021, 11, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavinho, S.R.; Pádua, A.S.; Holz, L.I.V.; Sá-Nogueira, I.; Silva, J.C.; Borges, J.P.; Valente, M.A.; Graça, M.P.F. Bioactive Glasses Containing Strontium or Magnesium Ions to Enhance the Biological Response in Bone Regeneration. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.H.; Bui, T.H.; Guseva, E.V.; Ta, A.T.; Nguyen, A.T.; Hoang, T.T.H.; Bui, X.V. Characterization of Bioactive Glass Synthesized by Sol-Gel Process in Hot Water. Crystals 2020, 10, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Arfa, B.A.E.; Pullar, R.C. A Comparison of Bioactive Glass Scaffolds Fabricated by Robocasting from Powders Made by Sol–Gel and Melt-Quenching Methods. Processes 2020, 8, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulyaganov, D.U.; Fiume, E.; Akbarov, A.; Ziyadullaeva, N.; Murtazaev, S.; Rahdar, A.; Massera, J.; Verné, E.; Baino, F. In Vivo Evaluation of 3D-Printed Silica-Based Bioactive Glass Scaffolds for Bone Regeneration. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermani, F.; Sadidi, H.; Ahmadabadi, A.; Hoseini, S.J.; Tavousi, S.H.; Rezapanah, A.; Nazarnezhad, S.; Hosseini, S.A.; Mollazadeh, S.; Kargozar, S. Modified Sol–Gel Synthesis of Mesoporous Borate Bioactive Glasses for Potential Use in Wound Healing. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negut, I.; Ristoscu, C. Bioactive Glasses for Soft and Hard Tissue Healing Applications—A Short Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinar-Díaz, J.; Arjuna, A.; Abrehart, N.; McLellan, A.; Harris, R.; Islam, M.T.; Alzaidi, A.; Bradley, C.R.; Gidman, C.; Prior, M.J.W.; et al. Development of Resorbable Phosphate-Based Glass Microspheres as MRI Contrast Media Agents. Molecules 2024, 29, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan Babu, M.; Syam Prasad, P.; Hima Bindu, S.; Prasad, A.; Venkateswara Rao, P.; Putenpurayil Govindan, N.; Veeraiah, N.; Özcan, M. Investigations on Physico-Mechanical and Spectral Studies of Zn2+ Doped P2O5-Based Bioglass System. J. Compos. Sci. 2020, 4, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, A.K.; Anthraper, M.S.J.; Hwang, N.S.; Rangasamy, J. Osteogenesis and angiogenesis promoting bioactive ceramics. Mat. Sci. Eng. R. 2024, 159, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Brauer, D.S.; Wilson, R.M.; Law, R.V.; Hill, R.G.; Karpukhina, N. Sodium Is Not Essential for High Bioactivity of Glasses. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 2017, 8, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango-Ospina, M.; Boccaccini, A.R. Chapter 4 - Bioactive glasses and ceramics for tissue engineering. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Biomaterials, issue Engineering Using Ceramics and Polymers (Third Edition); Boccaccini, A.R., Ma, P.X., Liverani, L., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing, 2022; pp. 111–178. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska, K.J.; Czechowska, J.P.; Yousef, E.S.; Zima, A. Novel phosphate bioglasses and bioglass-ceramics for bone regeneration. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 2024–45976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, K.E.; Hill, R.G.; Pembroke Brown, C.J.J.T.; Hatton, P.V. Influence of Sodium Oxide Content on Bioactive Glass Composite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2000, 10, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimonov, M.; Safronova, T.; Shatalova, T.; Filippov, Y.; Tikhomirova, I.; Sergeev, N. Composite Ceramics in the Na2O–CaO–SiO2–P2O5 System Obtained from Pastes including Hydroxyapatite and an Aqueous Solution of Sodium Silicate. Ceramics 2022, 5, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimonov, M.R.; Safronova, T.V. Materials in the Na2O–CaO–SiO2–P2O5 System for Medical Applications. Materials 2023, 16, 5981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.-Z.; Zhang, M.; Tang, H.-Y.; Qin, L.; Cheng, C.-K. P2O5 enhances the bioactivity of lithium silicate glass ceramics via promoting phase transformation and forming Li3PO4. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 13308–13317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, R.L.; Zanotto, E.D. The influence of phosphorus precursors on the synthesis and bioactivity of SiO2-CaO-P2O5 sol-gel glasses and glass-ceramics. J Mater Sci: Mater Med 2012, 24, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, E.A.; Mirsky, N.A.; Silva, B.L.G.; Shinde, A.R.; Arakelians, A.R.L.; Nayak, V.V.; Marcantonio, R.A.C.; Gupta, N.; Witek, L.; Coelho, P.G. Functional Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Regeneration: A Comprehensive Review of Materials, Methods, and Future Directions. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drevet, R.; Fauré,, J. ; Benhayoune, H. Calcium Phosphates and Bioactive Glasses for Bone Implant Applications. Coatings 2023, 13, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulyaganov, D.U.; Agathopoulos, S.; Dimitriadis, K.; Fernandes, H.R.; Gabrieli, R.; Baino, F. The Story, Properties and Applications of Bioactive Glass “1d”: From Concept to Early Clinical Trials. Inorganics 2024, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodoso-Torrecilla, I.; van den Beucken, J.J.J.P.; Jansen, J.A. Calcium phosphate cements: Optimization toward biodegradability. Acta Biomaterialia 2021, 119, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tong, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sui, R.; Yang, K.; Witte, F.; Yang, S. Porous metal materials for applications in orthopedic field: A review on mechanisms in bone healing. J. Orthop. Translat. 2024, 49, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suamte, L.; Tirkey, A.; Barman, J.; Babu, P.J. Various manufacturing methods and ideal properties of scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Smart Materials in Manufacturing, 2023, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfenov, V.A.; Mironov, V.A.; Koudan, E.V.; et al. Fabrication of calcium phosphate 3D scaffolds for bone repair using magnetic levitational assembly. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Young, D.; Kim, S.; Nishimoto, S.K.; Yang, Y. Novel template-casting technique for fabricating β-tricalcium phosphate scaffolds with high interconnectivity and mechanical strength and in vitro cell responses. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2010, 92A, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanzana, E.S.; Navarro, M.; Ginebra, M.-P.; Planell, J.A.; Ojeda, A.C.; Montecinos, H.A. Role of porosity and pore architecture in the in vivo bone regeneration capacity of biodegradable glass scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2014, 102, 1767–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velayudhan, S.; Ramesh, P.; Sunny, M.C.; Varma, H.K. Extrusion of hydroxyapatite to clinically significant shapes. Mater. Lett. 2000, 46, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgiou, V.; Kaplan, D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials 2025, 26, 5474–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Lu, T.; He, F.; Ye, J. Preparation and properties of porous calcium phosphate ceramic microspheres modified with magnesium phosphate surface coating for bone defect repair. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 7514–7527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoushtari, M.S.; Hoey, D.; Biak, D.R.A.; et al. Sol–gel-templated bioactive glass scaffold: a review. Res. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 40, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.S.L.; Black, J.R.; Franks, G.V.; Heath, D.E. Hierarchically porous 3D-printed ceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomater. Adv. 2025, 169, 214149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzavandi, Z.; Poursamar, S.A.; Amiri, F.; et al. 3D printed polycaprolactone/gelatin/ordered mesoporous calcium magnesium silicate nanocomposite scaffold for bone tissue regeneration. J. Mater. Sci: Mater. Med. 2024, 35, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, K.; Kovářík, T.; Křenek, T.; Docheva, D.; Stich, T.; Pola, J. Recent advances and future perspectives of sol–gel derived porous bioactive glasses: a review. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 33782–33835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xynos, I.D.; Hukkanen, M.V.; Batten, J.J.; Buttery, L.D.; Hench, L.L.; Polak, J.M. Bioglass 45S5® stimulates osteoblast turnover and enhances bone formation in vitro: Implications and applications for bone tissue engineering. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000, 67, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, J.; Vadgma, P.; Sampath Kumar, T.; Ramakrishna, S. Biocomposite nanofibres and osteoblasts for bone tissue engineering. Nanotechnology 2007, 18, 055101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, V.; Lakshmi, T. Bioglass: A novel biocompatible innovation. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2013, 4, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Okaily, M.S.; Mostafa, A.A.; Dulnik, J.; Denis, P.; Sajkiewicz, P.; Mahmoud, A.A.; Dawood, R.; Maged, A. Nanofibrous Polycaprolactone Membrane with Bioactive Glass and Atorvastatin for Wound Healing: Preparation and Characterization. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidian, H.; Chowdhury, S.D. Advancements and Applications of Injectable Hydrogel Composites in Biomedical Research and Therapy. Gels 2023, 9, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, N.; Gupta, P.; Arora, L.; Pal, D.; Singh, Y. Dexamethasone-Loaded, Injectable Pullulan-Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogels for Bone Tissue Regeneration in Chronic Inflammatory Conditions. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 130, 112463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mîrț, A.-L.; Ficai, D.; Oprea, O.-C.; Vasilievici, G.; Ficai, A. Current and Future Perspectives of Bioactive Glasses as Injectable Material. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, M.E.V.; Medeiros, R.P.; Shearer, A.; Fook, M.V.L.; Montazerian, M.; Mauro, J.C. Gelatin and Bioactive Glass Composites for Tissue Engineering: A Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-H.; Chen, I.-C.; Su, C.-Y.; Tsai, H.-H.; Young, T.-H.; Fang, H.-W. Development of Injectable Calcium Sulfate and Self-Setting Calcium Phosphate Composite Bone Graft Materials for Minimally Invasive Surgery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Ratnayake, J.; Cathro, P.; Gould, M.; Ali, A. Investigation of a Novel Injectable Chitosan Oligosaccharide—Bovine Hydroxyapatite Hybrid Dental Biocomposite for the Purposes of Conservative Pulp Therapy. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P.; Simão, A.F.; Graça, M.F.P.; Mariz, M.J.; Correia, I.J.; Ferreira, P. Dextran-Based Injectable Hydrogel Composites for Bone Regeneration. Polymers 2023, 15, 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, J.; Tong, W.; Hu, S.; Chen, Y.F.; Deng, S.; Yao, H.; Li, J.; Lee, C.W.; Chan, H.F. Injectable bioactive glass/sodium alginate hydrogel with immunomodulatory and angiogenic properties for enhanced tendon healing. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2022, 8, e10345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, A.T.; Abdallah, Y.K. Biomimetic Approach for Enhanced Mechanical Properties and Stability of Self-Mineralized Calcium Phosphate Dibasic–Sodium Alginate–Gelatine Hydrogel as Bone Replacement and Structural Building Material. Processes 2024, 12, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-Y.; Huang, S.-W.; Kao, I.-F.; Yen, S.-K. The Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan/Calcium Phosphate Composite Microspheres for Biomedical Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciołek, L.; Zaczyńska, E.; Krok-Borkowicz, M.; Biernat, M.; Pamuła, E. Chitosan and Sodium Hyaluronate Hydrogels Supplemented with Bioglass for Bone Tissue Engineering. Gels 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Thormann, U.; Kramer, I.; Sommer, U.; Budak, M.; Schumacher, M.; Bernhardt, A.; Lode, A.; Kern, C.; Rohnke, M.; et al. Mesoporous Bioactive Glass-Incorporated Injectable Strontium-Containing Calcium Phosphate Cement Enhanced Osteoconductivity in a Critical-Sized Metaphyseal Defect in Osteoporotic Rats. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, Q.; Tan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wan, Y.; Li, J. Multi-Crosslinked Strong and Elastic Bioglass/Chitosan-Cysteine Hydrogels with Controlled Quercetin Delivery for Bone Tissue Engineering. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohrabi, M.; Eftekhari Yekta, B.; Rezaie, H.; Naimi-Jamal, M.R.; Kumar, A.; Cochis, A.; Miola, M.; Rimondini, L. Enhancing Mechanical Properties and Biological Performances of Injectable Bioactive Glass by Gelatin and Chitosan for Bone Small Defect Repair. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergi, R.; Bellucci, D.; Salvatori, R.; Cannillo, V. Chitosan-Based Bioactive Glass Gauze: Microstructural Properties, In Vitro Bioactivity, and Biological Tests. Materials 2020, 13, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachet, A.; Bełżek, A.; Furtak, D.; Geworgjan, Z.; Tulej, D.; Kulczycka, K.; Karpiński, R.; Maciejewski, M.; Baj, J. Application of 3D Printing in Bone Grafts. Cells. 2023, 12, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwajler, B.; Witek-Krowiak, A. Three-Dimensional Printing of Multifunctional Composites: Fabrication, Applications, and Biodegradability Assessment. Materials 2023, 16, 7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.C.; Nayak, V.V.; Coelho, P.G.; Witek, L. Integrative Modeling and Experimental Insights into 3D and 4D Printing Technologies. Polymers 2024, 16, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danoux, C.B.; Barbieri, D.; Yuan, H.; de Bruijn, J.D.; van Blitterswijk, C.A.; Habibovic, P. In vitro and in vivo bioactivity assessment of a polylactic acid/hydroxyapatite composite for bone regeneration. Biomatter, 2014, 4, e27664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, S.; Vigneshwaran, M.; Qi, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Fu, G.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. Effect of Different Contents of 63s Bioglass on the Performance of Bioglass-PCL Composite Bone Scaffolds. Inventions 2023, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajzer, I.; Kurowska, A.; Frankova, J.; Sklenářová, R.; Nikodem, A.; Dziadek, M.; Jabłoński, A.; Janusz, J.; Szczygieł, P.; Ziąbka, M. 3D-Printed Polycaprolactone Implants Modified with Bioglass and Zn-Doped Bioglass. Materials 2023, 16, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, J.B.; Trombetta, R.P.; Hoffman, M.D.; Inzana, J.; Awad, H.; Benoit, D.S.W. Three dimensional printed calcium phosphate and poly(caprolactone) composites with improved mechanical properties and preserved microstructure. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2018, 106, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajiali, F.; Tajbakhsh, S.; Shojaei, A. Fabrication and Properties of Polycaprolactone Composites Containing Calcium Phosphate-Based Ceramics and Bioactive Glasses in Bone Tissue Engineering: A Review. Polymer Reviews 2017, 58, 164–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganbaatar, S.E.; Kim, H.-K.; Kang, N.-U.; Kim, E.C.; U, H.J.; Cho, Y.-S.; Park, H.-H. Calcium Phosphate (CaP) Composite Nanostructures on Polycaprolactone (PCL): Synergistic Effects on Antibacterial Activity and Osteoblast Behavior. Polymers 2025, 17, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, C.; Tulliani, J.-M.; Tadier, S.; Meille, S.; Chevalier, J.; Palmero, P. Novel calcium phosphate/PCL graded samples: Design and development in view of biomedical applications. Mat. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 97, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ródenas-Rochina, J.; Ribelles, J.L.; Lebourg, M. Comparative study of PCL-HAp and PCL-bioglass composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2013, 24, 1293–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshazly, N.; Nasr, F.E.; Hamdy, A.; Saied, S.; Elshazly, M. Advances in clinical applications of bioceramics in the new regenerative medicine era. World J Clin Cases 2024, 12, 1863–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amora, U.; Gloria, A.; Ambrosio, L. 10 - Composite materials for ligaments and tendons replacement. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Biomaterials, Biomedical Composites (Second Edition); Luigi, A., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing, 2017; pp. 215–235. ISBN 9780081007525. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Chen, L.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Jin, L.; Zhou, S.; Gao, L.; Li, R.; Li, Q.; Wang, H.; et al. Biomimetic Scaffolds for Tendon Tissue Regeneration. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Zhang, T.; Ju, W.; Chen, X.; Heng, B.C.; Shen, W.; Yin, Z. Biomimetic strategies for tendon/ligament-to-bone interface regeneration. Bioact Mater. 2021, 6, 2491–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Gupra, S.; Krishnamurthy, S. Multifarious applications of bioactive glasses in soft tissue engineering. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 8111–8147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, G.D.; de Sousa, V.R.; de Sousa, B.V.; de Araújo Neves, G.; de Lima Santana, L.N.; Menezes, R.R. Ceramic Nanofiber Materials for Wound Healing and Bone Regeneration: A Brief Review. Materials 2022, 15, 3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asefnejad, A.; Shadman-Manesh, V. Exploring the Impact of Ceramic Reinforcements on the Mechanical Properties of Wound Dressings and their Influence on Wound Healing and Drug Release. Scientific Hypotheses 2024, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naymi, H.A.S.; Al-Musawi, M.H.; Mirhaj, M.; Valizadeh, H.; Momeni, A.; Pajooh, A.M.D.; Shahriari-Khalaji, M.; Sharifianjazi, F.; Tavamaishvili, K.; Kazemi, N.; Salehi, S.; Arefpour, A.; Tavakoli, M. Exploring nanobioceramics in wound healing as effective and economical alternatives. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, G.K.; Martinez-Rodriguez, S.; Md Fadilah, N.I.; Looi Qi Hao, D.; Markey, G.; Shukla, P.; Fauzi, M.B.; Panetsos, F. Progress in Wound-Healing Products Based on Natural Compounds, Stem Cells, and MicroRNA-Based Biopolymers in the European, USA, and Asian Markets: Opportunities, Barriers, and Regulatory Issues. Polymers 2024, 16, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosvi, S.R.; Day, R.M. Bioactive glass modulation of intestinal epithelial cell restitution. Acta Biomaterialia 2009, 5, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Xue, T.; Chen, B.; Zhou, X.; Ji, Y.; Gao, Z.; Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Shen, Y.; Sun, H.; Gu, X.; Dai, B. Advances in biomaterial-based tissue engineering for peripheral nerve injury repair. Bioactive Mater. 2025, 46, 150–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornasari, B.E.; Carta, G.; Gambarotta, G.; Raimondo, S. Natural-Based Biomaterials for Peripheral Nerve Injury Repair. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020, 16, 554257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Tang, S.; Wang, J.; Lv, S.; Zheng, K.; Xu, Y.; Li, K. Bioactive Glasses: Advancing Skin Tissue Repair through Multifunctional Mechanisms and Innovations. Biomater Res. 2025, 29, 0134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmero, P. 15 - Ceramic–polymer nanocomposites for bone-tissue regeneration. In Nanocomposites for Musculoskeletal Tissue Regeneration; Liu, H., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing, 2016; pp. 331–367. [Google Scholar]

- Eliaz, N.; Metoki, N. Calcium phosphate bioceramics: a review of their history, structure, properties, coating technologies and biomedical applications. Materials 2017, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tang, M. Bioceramic materials with ion-mediated multifunctionality for wound healing. Smart Medicine 2022, 1, e20220032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xue, J.; Ma, B.; Wu, J.; Chang, J.; Gelinsky, M.; Wu, C. Black Bioceramics: Combining Regeneration with Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2005140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova, E.; Tikhomirova, V.; Akhmetova, A.; Ilina, I.; Kalinina, N.; Taliansky, M.; Kost, O. Calcium Phosphate Nanoparticles as Carriers of Low and High Molecular Weight Compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanael, A.J.; Oh, T.H. Encapsulation of Calcium Phosphates on Electrospun Nanofibers for Tissue Engineering Applications. Crystals 2021, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimov, A.D.; Ivanova, A.A.; Zyuzin, M.V.; Timin, A.S. Porous Inorganic Carriers Based on Silica, Calcium Carbonate and Calcium Phosphate for Controlled/Modulated Drug Delivery: Fresh Outlook and Future Perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, Y.-C.; Tseng, Y.-C.; Mozumdar, S.; Huang, L. Biodegradable calcium phosphate nanoparticle with lipid coating for systemic siRNA delivery. J. Control. Release 2010, 142, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levingstone, T.J.; Herbaj, S.; Dunne, N.J. Calcium Phosphate Nanoparticles for Therapeutic Applications in Bone Regeneration. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iafisco, M.; Palazzo, B.; Marchetti, M.; Margiotta, N.; Ostuni, R.; Natile, G.; Morpurgo, M.; Gandin, V.; Marzano, C.; Roveri, N. Smart delivery of antitumoral platinum complexes from biomimetic hydroxyapatite nanocrystals. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 8385–8392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, T.; Okazaki, M.; Inoue, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kusunose, T.; Toyonaga, T.; Hamada, Y.; Takahashi, J. Hydroxyapatite particles as a controlled release carrier of protein. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 3807–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uskoković, V.; Batarni, S.S.; Schweicher, J.; King, A.; Desai, T.A. Effect of calcium phosphate particle shape and size on their antibacterial and osteogenic activity in the delivery of antibiotics in vitro. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 2422–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundrapandian, C.; Datta, S.; Kundu, B.; Basu, D.; Sa, B. Porous bioactive glass scaffolds for local drug delivery in osteomyelitis: development and in vitro characterization. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2010, 11, 1675–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Hong, S.; Jiang, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, X.; He, X.; Liu, J.; Lin, K.; Mao, L. Engineering mesoporous bioactive glasses for emerging stimuli-responsive drug delivery and theranostic applications. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 34, 436–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallet-Regí, M.; Colilla, M.; Izquierdo-Barba, I.; Vitale-Brovarone, C.; Fiorilli, S. Achievements in Mesoporous Bioactive Glasses for Biomedical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Zheng, K.; Boccaccini, A.R. Multi-Functional Silica-Based Mesoporous Materials for Simultaneous Delivery of Biologically Active Ions and Therapeutic Biomolecules. Acta Biomater. 2021, 129, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, E.; Bigham, A.; Yousefiasl, S.; Trovato, M.; Ghomi, M.; Esmaeili, Y.; Samadi, P.; Zarrabi, A.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Sharifi, S.; et al. Mesoporous Bioactive Glasses in Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy: Stimuli-Responsive, Toxicity, Immunogenicity, and Clinical Translation. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2102678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Luo, J.; Deng, Y.; Li, Z.; Wei, J. Alginate-modified mesoporous bioactive glass and its drug delivery, bioactivity, and osteogenic properties. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 994925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-L.; Fang, W.; Huang, B.-R.; Wang, Y.-H.; Dong, G.-C.; Lee, T.-M. Bioactive Glass as a Nanoporous Drug Delivery System for Teicoplanin. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, R.; Tsiridis, E.; Giannoudis, P.V. Current concepts of molecular aspects of bone healing. Injury 2005, 36, 1392–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wang, Q.; Wu, T.; Pan, H. Understanding adsorption-desorption dynamics of BMP-2 on hydroxyapatite (001) surface. Biophys. J. 2007, 93, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, A.; Gao, Y.; Suryaji, P.; Tian, Y.; Lin, X.; Dang, K.; Jiang, S.; Li, Y.; Miao, Z.; Qian, A. Non-Viral Delivery System and Targeted Bone Disease Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matic, T.; Daou, F.; Cochis, A.; Barac, N.; Ugrinovic, V.; Rimondini, L.; Veljovic, D. Multifunctional Sr,Mg-Doped Mesoporous Bioactive Glass Nanoparticles for Simultaneous Bone Regeneration and Drug Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Rodriguez, P.; Sánchez, M.; Landin, M. Drug-Loaded Biomimetic Ceramics for Tissue Engineering. Pharmaceutics. 2018, 10, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Majumdar, S.; Krishnamurthy, S. Bioactive glass: A multifunctional delivery system. J. Control. Release 2021, 335, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangri, S.; Hasan, N.; Kaur, J.; Mohammad, F.; Maan, S.; Kesharwani, P.; Ahmad, F.J. Drug loaded bioglass nanoparticles and their coating for efficient tissue and bone regeneration. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2023, 616, 122469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miola, M.; Vitale-Brovarone, C.; Mattu, C.; Verné, E. Antibiotic loading on bioactive glasses and glass-ceramics: An approach to surface modification. J. Biomater. Appl. 2012, 28, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatti, E.; Miola, M.; Verné, E. Tailoring of bioactive glass and glass-ceramics properties for in vitro and in vivo response optimization: a review. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 4546–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auniq, R.B.Z.; Hirun, N.; Boonyang, U. Three-Dimensionally Ordered Macroporous-Mesoporous Bioactive Glass Ceramics for Drug Delivery Capacity and Evaluation of Drug Release. In Advanced Ceramic Materials; Mhadhbi, M., Ed.; IntechOpen, 2021; p. 95290. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, W.; Zhu, M.; Wu, C.; Zhu, Y. Bioceramic-based scaffolds with antibacterial function for bone tissue engineering: A review. Bioact Mater. 2022, 18, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergi, R.; Bellucci, D.; Cannillo, V. A Comprehensive Review of Bioactive Glass Coatings: State of the Art, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Coatings 2020, 10, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.N.; Su, Y.; Lu, X.; Kuo, P.H.; Du, J.; Zhu, D. Bioactive glass coatings on metallic implants for biomedical applications. Bioact Mater. 2019, 4, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, A.; Bellucci, D.; Cannillo, V.; Cattini, A. Bioactive glass coatings: A review. Surf. Eng. 2011, 27, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drevet, R.; Fauré, J.; Benhayoune, H. Electrophoretic Deposition of Bioactive Glass Coatings for Bone Implant Applications: A Review. Coatings 2024, 14, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsen, J.A.; Proost, J.; Schrooten, J.; Timmermans, G.; Brauns, E.; Vanderstraeten, J. Glasses and bioglasses: Synthesis and coatings. J. Eur. Cer. Soc. 1997, 17, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Nezami, M.; Abbasi Khazaei, B. Applying 58S Bioglass Coating on Titanium Substrate: Effect of Multiscale Roughness on Bioactivity, Corrosion Resistance and Coating Adhesion. J Bio Tribo Corros 2024, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanca, C.; Milazzo, A.; Campora, S.; Capuana, E.; Pavia, F.C.; Patella, B.; Lopresti, F.; Brucato, V.; La Carrubba, V.; Inguanta, R. Galvanic Deposition of Calcium Phosphate/Bioglass Composite Coating on AISI 316L. Coatings 2023, 13, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjam, P.; Luckabauer, M.; de Vries, E.G.; Rangel, V.R.; Hekman, E.E.G.; Verkerke, G.J.; Rouwkema, J. Bioactive calcium phosphate coatings applied to flexible poly(carbonate urethane) foils. Surf. Coat. Techn. 2023, 470, 129838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozelskaya, A.; Dubinenko, G.; Vorobyev, A.; Fedotkin, A.; Korotchenko, N.; Gigilev, A.; Shesterikov, E.; Zhukov, Y.; Tverdokhlebov, S. Porous CaP Coatings Formed by Combination of Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation and RF-Magnetron Sputtering. Coatings 2020, 10, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duta, L.; Oktar, F.N. Synthetic and Biological-Derived Hydroxyapatite Implant Coatings. Coatings 2024, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Su, Y.; Qin, Y.-X. Calcium phosphate coatings enhance biocompatibility and degradation resistance of magnesium alloy: Correlating in vitro and in vivo studies. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drevet, R.; Fauré, J.; Benhayoune, H. Bioactive Calcium Phosphate Coatings for Bone Implant Applications: A Review. Coatings 2023, 13, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosca, M.; Streza, A.; Antoniac, I.V.; Vadalà, G.; Rau, J.V. Ion-Doped Calcium Phosphate-Based Coatings with Antibacterial Properties. J. Funct Biomater. 2023, 14, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, V.N.; Kharovskaya, M.I.; Lazoryak, B.I.; Solovieva, A.O.; Fadeeva, I.V.; Amirov, A.A.; Koliushenkov, M.A.; Orudzhev, F.F.; Baryshnikova, O.V.; Yankova, V.G.; et al. Strontium and Copper Co-Doped Multifunctional Calcium Phosphates: Biomimetic and Antibacterial Materials for Bone Implants. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furko, M.; Horváth, Z.E.; Tolnai, I.; Balázsi, K.; Balázsi, C. Investigation of Calcium Phosphate-Based Biopolymer Composite Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubiak-Mihkelsoo, Z.; Kostrzębska, A.; Błaszczyszyn, A.; Pitułaj, A.; Dominiak, M.; Gedrange, T.; Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Matys, J.; Hadzik, J. Ionic Doping of Hydroxyapatite for Bone Regeneration: Advances in Structure and Properties over Two Decades—A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Dali, S.S.; Wong, S.K.; Chin, K.-Y.; Ahmad, F. The Osteogenic Properties of Calcium Phosphate Cement Doped with Synthetic Materials: A Structured Narrative Review of Preclinical Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niziołek, K.; Słota, D.; Ronowska, A.; Sobczak-Kupiec, A. Calcium Phosphate Biomaterials Modified with Mg2+ or Mn2+ Ions: Structural, Chemical, and Biological Characterization. Ceram. Int. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Peng, Q. Metal Ion-Doped Hydroxyapatite-Based Materials for Bone Defect Restoration. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furko, M.; Horváth, Z.E.; Czömpöly, O.; Balázsi, K.; Balázsi, C. Biominerals Added Bioresorbable Calcium Phosphate Loaded Biopolymer Composites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostka, K.; Hosseini, S.; Epple, M. In-Vitro Cell Response to Strontium/Magnesium-Doped Calcium Phosphate Nanoparticles. Micro 2023, 3, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves Côrtes, J.; Dornelas, J.; Duarte, F.; Messora, M.R.; Mourão, C.F.; Alves, G. The Effects of the Addition of Strontium on the Biological Response to Calcium Phosphate Biomaterials: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skallevold, H.E.; Rokaya, D.; Khurshid, Z.; Zafar, M.S. Bioactive Glass Applications in Dentistry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacan, I.; Moldovan, M.; Sarosi, C.; Cuc, S.; Pastrav, M.; Petean, I.; Ene, R. Mechanical Properties and Liquid Absorption of Calcium Phosphate Composite Cements. Materials 2023, 16, 5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalewicz, K.; Vorndran, E.; Feichtner, F.; Waselau, A.-C.; Brueckner, M.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A. In-Vivo Degradation Behavior and Osseointegration of 3D Powder-Printed Calcium Magnesium Phosphate Cement Scaffolds. Materials 2021, 14, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, Z.; Abdallah, M.-N.; Hanafi, A.A.; Misbahuddin, S.; Rashid, H.; Glogauer, M. Mechanisms of in Vivo Degradation and Resorption of Calcium Phosphate Based Biomaterials. Materials 2015, 8, 7913–7925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyyra, I.; Leino, K.; Hukka, T.; Hannula, M.; Kellomäki, M.; Massera, J. Impact of Glass Composition on Hydrolytic Degradation of Polylactide/Bioactive Glass Composites. Materials 2021, 14, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backes, E.H.; Pires, L.d.N.; Costa, L.C.; Passador, F.R.; Pessan, L.A. Analysis of the Degradation During Melt Processing of PLA/Biosilicate® Composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2019, 3, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewald, A.; Fuchs, A.; Boegelein, L.; Grunz, J.-P.; Kneist, K.; Gbureck, U.; Hoelscher-Doht, S. Degradation and Bone-Contact Biocompatibility of Two Drillable Magnesium Phosphate Bone Cements in an In Vivo Rabbit Bone Defect Model. Materials 2023, 16, 4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Yin, J.; Gao, X. Additive Manufacturing of Bioactive Glass and Its Polymer Composites as Bone Tissue Engineering Scaffolds: A Review. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, A.; Bellucci, D.; Cannillo, V. An Enhanced Bioactive Glass Composition with Improved Thermal Stability and Sinterability. Materials 2024, 17, 6175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Lin, J. Effect of pH on the In Vitro Degradation of Borosilicate Bioactive Glass and Its Modulation by Direct Current Electric Field. Materials 2022, 15, 7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, A.; Oudadesse, H.; el Feki, H.; Cheikhrouhou-Koubaa, W.; Chatzistavrou, X.; V Rau, J.; Heinämäki, J.; Antoniac, I.; Ashammakhi, N.; Derbel, N. High Boron Content Enhances Bioactive Glass Biodegradation. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhy, B.; Priyadarshini, P.; Sen, A.K. Effect of surface energy and roughness on cell adhesion and growth - facile surface modification for enhanced cell culture. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 15467–15476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Xie, W.; Yu, L.; Camacho, L.C.; Nie, C.; Zhang, M.; Haag, R.; Wei, Q. Surface Roughness Gradients Reveal Topography-Specific Mechanosensitive Responses in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Nano Micro Small 2020, 16, 1905422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Wang, Z.; Gu, L.; Ma, Z.; Zheng, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y. Unraveling the relationship between the structural features and solubility properties in Sr-containing bioactive glasses. Ceram. Inter. Part A 2024, 50, 4245–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilocca, A. Structural models of bioactive glasses from molecular dynamics simulations. Proc. R. Soc. A 2009, 465, 1003–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolan, K.C.R.; Huang, Y.W.; Semon, J.A.; Leu, M.C. 3D-printed Biomimetic Bioactive Glass Scaffolds for Bone Regeneration in Rat Calvarial Defects. Int J Bioprint. 2020, 6, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Galusková, D.; Kaňková, H.; Švančárková, A.; Galusek, D. Early-Stage Dissolution Kinetics of Silicate-Based Bioactive Glass under Dynamic Conditions: Critical Evaluation. Materials 2021, 14, 3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, A.; Wang, D.; Huang, W.; Fu, Q.; Rahaman, M.N.; Day, D.E. In Vitro Bioactive Characteristics of Borate-Based Glasses with Controllable Degradation Behavior. J Am Cer Soc 2007, 90, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, J.K.; Ainsworth, R.I.; Di Tommaso, D.; de Leeuw, N.H. Nanoscale chains control the solubility of phosphate glasses for biomedical applications. J Phys Chem B. 2013, 117, 10652–10657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Descamps, M.; Dejou, J.; Hardouin, P.; Lemaitre, J.; Proust, J.-P. The biodegradation mechanism of calcium phosphate biomaterials in bone. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2002, 63, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.L.; Valério, P.; Goes, A.M.; de Fátima Leite, M.; Domingues, R.Z. Influence of morphology on in vitro compatibility of bioactive glasses. J. Non.Cryst. Solids 2006, 352, 3508–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pace, R.; Molinari, S.; Mazzoni, E.; Perale, G. Bone Regeneration: A Review of Current Treatment Strategies. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Fernández, I.; Haugen, H.J.; Nogueira, L.P.; López-Álvarez, M.; González, P.; López-Peña, M.; González-Cantalapiedra, A.; Muñoz-Guzón, F. Enhanced Bone Healing in Critical-Sized Rabbit Femoral Defects: Impact of Helical and Alternate Scaffold Architectures. Polymers 2024, 16, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochu, B.M.; Sturm, S.R.; Kawase De Queiroz Goncalves, J.A.; Mirsky, N.A.; Sandino, A.I.; Panthaki, K.Z.; Panthaki, K.Z.; Nayak, V.V.; Daunert, S.; Witek, L.; et al. Advances in Bioceramics for Bone Regeneration: A Narrative Review. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, K.E.; de Andrade ESilva, F.B.; Leonhardt, M.C.; de Carvalho, V.C.; de Oliveira, P.R.D.; Lima, A.L.L.M.; Roberto Dos Reis, P.; Silva, J.D.S. Bioactive glass S53P4 to fill-up large cavitary bone defect after acute and chronic osteomyelitis treated with antibiotic-loaded cement beads: A prospective case series with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Injury. 2021, 52 Suppl 3, S23–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrill, E.; Pennington, Z.; Lankipalle, N.; Ehresman, J.; Valencia, C.; Schilling, A.; Feghali, J.; Perdomo-Pantoja, A.; Theodore, N.; Sciubba, D.M.; et al. The Effect of Bioactive Glasses on Spinal Fusion: A Cross-Disciplinary Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Preclinical and Clinical Data. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 78, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vugt, T.A.G.; Heidotting, J.; Arts, J.J.; Ploegmakers, J.J.W.; Jutte, P.C.; Geurts, J.A.P. Mid-term clinical results of chronic cavitary long bone osteomyelitis treatment using S53P4 bioactive glass: a multi-center study. J Bone Jt Infect. 2021, 2021 6, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malat, T.A.; Glombitza, M.; Dahmen, J.; Hax, P.-M.; Steinhausen, E. The Use of Bioactive Glass S53P4 as Bone Graft Substitute in the Treatment of Chronic Osteomyelitis and Infected Non-Unions—A Retrospective Study of 50 Patients. Z. Orthop. Unf. 2018, 156, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, J.C.C.; Oliveira, L.; Vaz, M.F.; Costa-de-Oliveira, S. Biodegradable Bone Implants as a New Hope to Reduce Device-Associated Infections-A Systematic Review. Bioengineering (Basel). 2022, 9, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindfors, N.C.; Hyvönen, P.; Nyyssönen, M.; Kirjavainen, M.; Kankare, J.; Gullichsen, E.; Salo, J. Bioactive glass S53P4 as bone graft substitute in treatment of osteomyelitis. Bone. 2010, 47, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gestel, N.A.; Geurts, J.; Hulsen, D.J.; van Rietbergen, B.; Hofmann, S.; Arts, J. Clinical Applications of S53P4 Bioactive Glass in Bone Healing and Osteomyelitic Treatment: A Literature Review. Biomed Res Int. 2015, 2015, 684826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scribante, A.; Vallittu, P.K.; Özcan, M.; Lassila, L.V.J.; Gandini, P.; Sfondrini, M.F. Travel beyond Clinical Uses of Fiber Reinforced Composites (FRCs) in Dentistry: A Review of Past Employments, Present Applications, and Future Perspectives. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1498901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Seles, M.A.; Rajan, M. Role of bioglass derivatives in tissue regeneration and repair: A review. Rev. Adv. Mater, Sci. 2023, 62, 20220318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Hamdi, M.; Basirun, W.J. Bioglass® 45S5-based composites for bone tissue engineering and functional applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2017, 105, 3197–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, D.M.B.; Rosso, M.P.O.; Buchaim, D.V.; Zangrando, M.S.R.; Buchaim, R.L. Update on the use of 45S5 bioactive glass in the treatment of bone defects in regenerative medicine. World J Orthop. 2024, 15, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, D.; Anesi, A.; Salvatori, R.; Chiarini, L.; Cannillo, V. A comparative in vivo evaluation of bioactive glasses and bioactive glass-based composites for bone tissue repair. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 79, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crovace, M.C.; Souza, M.T.; Chinaglia, C.R.; Peitl, O.; Zanotto, E.D. Biosilicate® — A multipurpose, highly bioactive glass-ceramic. In vitro, in vivo and clinical trials. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2016, 432, Part. [Google Scholar]

- Fakher, S.; Westenberg, D. Properties and antibacterial effectiveness of metal-ion doped borate-based bioactive glasses. Future Microbiology 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madival, H.; Rajiv, A.; Muniraju, C.; Reddy, M.S. Advancements in Bioactive Glasses: A Comparison of Silicate, Borate, and Phosphate Network Based Materials. Biomedical Materials & Devices 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannio, M.; Bellucci, D.; Roether, J.A.; Boccaccini, D.N.; Cannillo, V. Bioactive Glass Applications: A Literature Review of Human Clinical Trials. Materials (Basel) 2021, 14, 5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannillo, V.; Salvatori, R.; Bergamini, S.; Bellucci, D.; Bertoldi, C. Bioactive Glasses in Periodontal Regeneration: Existing Strategies and Future Prospects—A Literature Review. Materials 2022, 15, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.W. Periodontal Therapy Using Bioactive Glasses: A Review. Prosthesis 2022, 4, 648–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Orgill, D.P.; Galiano, R.D.; Glat, P.M.; DiDomenico, L.A.; Carter, M.J.; Zelen, C.M. A multi-centre, single-blinded randomised controlled clinical trial evaluating the effect of resorbable glass fibre matrix in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2022, 9, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, S.; Detsch, R.; Uhl, F.; Deisinger, U.; Ziegler, G. How Degradation of Calcium Phosphate Bone Substitute Materials is influenced by Phase Composition and Porosity. Adv. Eng. Mat. 2011, 13, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishchenko, O.; Yanovska, A.; Kosinov, O.; Maksymov, D.; Moskalenko, R.; Ramanavicius, A.; Pogorielov, M. Synthetic Calcium–Phosphate Materials for Bone Grafting. Polymers 2023, 15, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibiński, S.; Czechowska, J.P.; Guzik, M.; Vivcharenko, V.; Przekora, A.; Szymczak, P.; Zima, A. Scaffolds based on β tricalcium phosphate and polyhydroxyalkanoates as biodegradable and bioactive bone substitutes with enhanced physicochemical properties. Sustain. Mater. Techn. 2023, 38, e00722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.S.F.; Negut, I.; Bita, B. The Use of Calcium Phosphate Bioceramics for the Treatment of Osteomyelitis. Ceramics 2024, 7, 1779–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Shiwaku, Y.; Hamai, R.; Tsuchiya, K.; Sasaki, K.; Suzuki, O. Macrophage Polarization Related to Crystal Phases of Calcium Phosphate Biomaterials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, M.; Mavropoulos, E.; Sader, M.S.; Costa, A.; Lopez, E.; Fontes, G.N.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Romasco, T.; Di Pietro, N.; Piattelli, A.; et al. Effects of Physically Adsorbed and Chemically Immobilized RGD on Cell Adhesion to a Hydroxyapatite Surface. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, P.; Kampleitner, C.; De Lima, J.; Brennan, M.Á.; Lodoso-Torrecilla, I.; Sadowska, J.M.; Blanchard, F.; Canal, C.; Ginebra, M.-P.; Hoffmann, O.; Layrolle, P. Phase composition of calcium phosphate materials affects bone formation by modulating osteoclastogenesis. Acta Biomater. 2024, 176, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shu, T.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Li, A.; Pei, D. The Osteoinductivity of Calcium Phosphate-Based Biomaterials: A Tight Interaction With Bone Healing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 911180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Ling, J.; Gao, Y.; Xiao, Y. Effects of varied ionic calcium and phosphate on the proliferation, osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of human periodontal ligament cells in vitro. J Periodont Res 2012, 47, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varanasi, V.G.; Owyoung, J.B.; Saiz, E.; Marshall, S.J.; Marshall, G.W.; Loomer, P.M. The ionic products of bioactive glass particle dissolution enhance periodontal ligament fibroblast osteocalcin expression and enhance early mineralized tissue development. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011, 98, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ftiti, S.; Cifuentes, S.C.; Guidara, A.; Rams, J.; Tounsi, H.; Fernández-Blázquez, J.P. The Structural, Thermal and Morphological Characterization of Polylactic Acid/Β-Tricalcium Phosphate (PLA/Β-TCP) Composites upon Immersion in SBF: A Comprehensive Analysis. Polymers (Basel). 2024, 16, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Yagi, R.; Waki, T.; Wada, T.; Ohkubo, C.; Hayakawa, T. Study of Apatite Deposition in a Simulated Body Fluid Immersion Experiment. J. Oral Tissue Eng. 2016, 14, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimian-Hosseinabadi, M.; Etemadifar, M.; Ashrafizadeh, F. Effects of Nano-biphasic Calcium Phosphate Composite on Bioactivity and Osteoblast Cell Behavior in Tissue Engineering Applications. J. Med. Signals Sens. 2016, 6, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, P.P.; Kretlow, J.D.; Young, S.; Jansen, J.A.; Kasper, F.K.; Mikos, A.G. Evaluation of bone regeneration using the rat critical size calvarial defect. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 1918–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, S.K.; Li, L.; Qin, L.; Wang, X.L.; Lai, Y.X. Bone defect animal models for testing efficacy of bone substitute biomaterials. J. Orthop. Translat. 2015, 2015 3, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Shang, Z.; Zhao, B.; Jiao, M.; Liu, W.; Cheng, M.; Zhai, B.; Guo, Y.; Liu, B.; Shi, X.; Ma, B. Biodegradable metals for bone defect repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on animal studies. Bioactive Mater. 2021, 6, 4027–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 220. Kubasiewicz-Ross, P.; Hadzik, J.; Seeliger, J.; Kozak, K.; Jurczyszyn, K.; Gerber, H.; Dominiak, M.; Kunert-Keil, C. New nano-hydroxyapatite in bone defect regeneration: A histological study in rats. Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger 2017, 213, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, H.; Sase, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Takasuna, H. Histological assessment of porous custom-made hydroxyapatite implants 6 months and 2.5 years after cranioplasty. 19-Jan-2017;8:8.

- Wang, W.; Yeung, K.W.K. Bone grafts and biomaterials substitutes for bone defect repair: A review. Bioact Mater. 2017, 2, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Wang, M.M.; Witek, L.; Tovar, N.; Cronstein, B.N.; Torroni, A.; Flores, R.L.; Coelho, P.G. Transforming the Degradation Rate of β-tricalcium Phosphate Bone Replacement Using 3-Dimensional Printing. Ann Plast Surg. 2021, 87, e153–e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin Liu, P.D.; Deng-xing Lun, M.S.C. Current Application of β-tricalcium Phosphate Composites in Orthopaedics, Orthopaedic Surgery 4 139-144.

- Tanaka, H.; Komaki, M. Chazono, S. Kitasato. Marumo, Basic research and clinical application of beta-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP). Morphologie 2017, 101, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, D.C.; Mingrone, L.E.; Sá, M.J.C. Evaluation of Osseointegration and Bone Healing Using Pure-Phase β - TCP Ceramic Implant in Bone Critical Defects. A Systematic Review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 859920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, F.A.; Jolic, M.; Micheletti, C.; Omar, O.; Norlindh, B.; Emanuelsson, L.; Engqvist, H.; Engstrand, T.; Palmquist, A.; Thomsen, P. Bone without borders – Monetite-based calcium phosphate guides bone formation beyond the skeletal envelope. Bioactive Materials 2023, 19, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Voto, A.; Fortino, L.; Guida, R.; Laudisio, C.; Cillo, M.; D’Ursi, A.M. Bone Defect Treatment in Regenerative Medicine: Exploring Natural and Synthetic Bone Substitutes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, U.; Gbureck, S.B.; Bhaduri, P.; Sikder, M. An important calcium phosphate compound–Its synthesis, properties and applications in orthopedics. Acta Biomaterialia 2021, 127, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, S.-W.; Paik, J.-W.; Lee, D.-N.; Seo, Y.-W.; Park, J.-Y.; Kim, S.; Choi, S.-H. Comparative Analysis of Bone Regeneration According to Particle Type and Barrier Membrane for Octacalcium Phosphate Grafted into Rabbit Calvarial Defects. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S.G. Advancements in alveolar bone grafting and ridge preservation: a narrative review on materials, techniques, and clinical outcomes. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 46, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphel, J.; Holodniy, M.; Goodman, S.B.; Heilshorn, S.C. Multifunctional coatings to simultaneously promote osseointegration and prevent infection of orthopaedic implants. Biomaterials 2016, 84, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasser, R.A.; AlSubaie, A.; AlShehri, F. Effectiveness of beta-tricalcium phosphate in comparison with other materials in treating periodontal infra-bony defects around natural teeth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2021, 21, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, L.; Alifarag, A.M.; Tovar, N.; Lopez, C.D.; Cronstein, B.N.; Rodriguez, E.D.; Coelho, P.G. Repair of Critical-Sized Long Bone Defects Using Dipyridamole-Augmented 3D-Printed Bioactive Ceramic Scaffolds. J. Orthopeadic Res. 2019, 37, 2499–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishack, S.; Mediero, A.; Wilder, T.; Ricci, J.L.; Cronstein, B.N. Bone regeneration in critical bone defects using three-dimensionally printed β-tricalcium phosphate/hydroxyapatite scaffolds is enhanced by coating scaffolds with either dipyridamole or BMP-2. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2017, 105, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Strontium Functionalized in Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering: A Prominent Role in Osteoimmunomodulation. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 928799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, X.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, J. Advanced applications of strontium-containing biomaterials in bone tissue engineering. Mater. Today Bio. 2023, 20, 100636. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, J.; Gholipourmalekabadi, M.; Cao, Y.; Lin, K.; Zhuang, Y.; Yuan, C. From hard tissues to beyond: Progress and challenges of strontium-containing biomaterials in regenerative medicine applications. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 49, 85–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, H.; Zhang, J.; Sun, T.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z. Recent Advance of Strontium Functionalized in Biomaterials for Bone Regeneration. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://www.porexsurgical.

- Available online: https://novabone.

- Available online: https://www.bonalive.

- Available online: https://www.stryker.com/hk/en/interventional-spine/products/cortoss-bone-augmentation-material.

- Available online: https://www.novetech-surgery.

- Available online: https://www.biospace.

- Available online: https://regenity.

- Available online: https://skulleimplants.

- Available online: https://www.bioventussurgical.

- Available online: https://www.gsk.

- Available online: https://avalonmed.

- Available online: https://theraglass.co.

- Rizwan, M.; Hamdi, M.; Basirun, W.J. Bioglass® 45S5-based composites for bone tissue engineering and functional applications. J Biomed Mater Res A 2017, 105, 3197–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baino, F.; Hamzehlou, S.; Kargozar, S. Bioactive Glasses: Where Are We and Where Are We Going? J. Funct. Biomater. 2018, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.novetech-surgery.

- Available online: https://www.zimmerbiomet.

- Available online: https://www.jnjmedtech.

- Available online: https://www.bioceramed.

- Available online: https://www.hoyatechnosurgical.co.

- Available online: https://pro-healthint.

- Available online: https://www.teknimed.

- Available online: https://www.curasan.

- Available online: https://bonegraft.com.

- Available online: https://biomatlante.

- Yousefi, A.-M. A review of calcium phosphate cements and acrylic bone cements as injectable materials for bone repair and implant fixation. J. Appl. Biomater. Func. Mater. 2019, 17, 2280800019872594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettich, G.; Schierjott, R.A.; Epple, M.; Gbureck, U.; Heinemann, S.; Mozaffari-Jovein, H.; Grupp, T.M. Calcium Phosphate Bone Graft Substitutes with High Mechanical Load Capacity and High Degree of Interconnecting Porosity. Materials 2019, 12, 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Reis, M.; Figueiredo, L.; Pimenta, A.; Santos, L.F.; Branco, A.C.; Alves de Matos, A.P.; Salema-Oom, M.; Almeida, A.; Pereira, M.F.C.; Colaço, R.; Serro, A.P. Improvement of a commercial calcium phosphate bone cement by means of drug delivery and increased injectability. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 33361–33372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, A.; Engblom, M.; Karlström, O.; Lindén, M.; Hupa, L. Impact of Fluid Flow Rate on the Dissolution Behavior of Bioactive Glass S53P4. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2023, 607, 122219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskher, H.; Sharifianjazi, F.; Tavamaishvili, K.; Irandoost, M.; Nejadkoorki, D.; Makvandi, P. Limitations, Challenges and Prospective Solutions for Bioactive Glasses-Based Nanocomposites for Dental Applications: A Critical Review. J. Dent. 2024, 150, 105331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Impregnation | Loading drugs into pre-formed CaP scaffolds by soaking them in a drug-containing solution. |

| Co-precipitation | Simultaneous precipitation of CaP and the drug from a solution, leading to homogeneous distribution of the drug within the matrix. |

| Encapsulation | Enclosing drugs within CaP microspheres or nanoparticles providing controlled release profiles. |

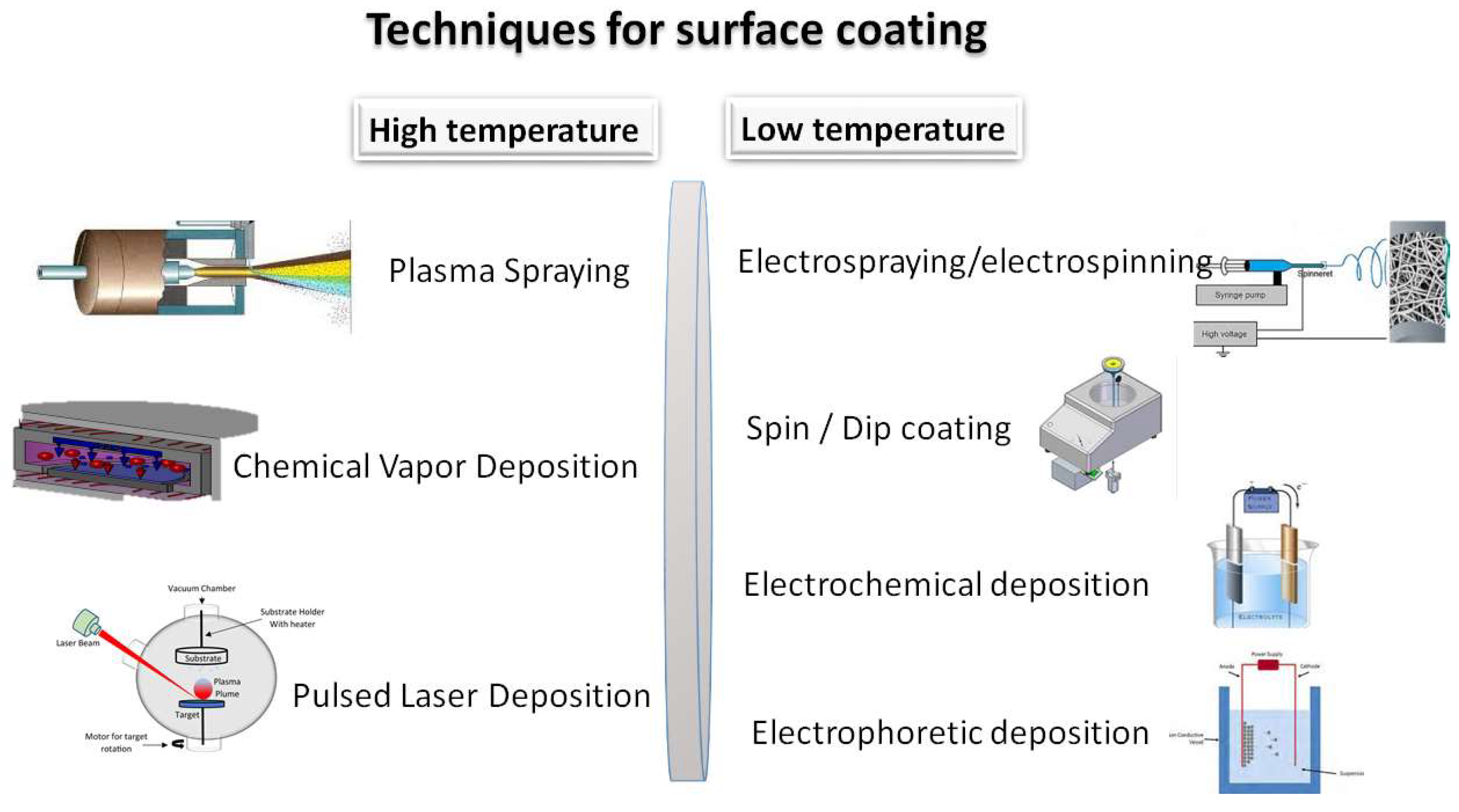

| Technique | Coating Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Plasma Spray | Homogeneous and dense layer; fast deposition rate; coating thickness and deposition parameters are easy to control; good coating adherence to substrate; improved corrosion and wear resistance. But: expensive equipment; high temperature; crack development; complex-shaped substrates are difficult to coat. |

| Chemical Vapor Deposition | |

| Pulsed Laser Deposition | |

| Electrospraying/electrospinning | Nanofibrous; porous structure; high specific surface area; mimics ECM. But: poor adhesion; limited thickness; poor mechanical properties. |

| Spin / Dip coating | Smooth, thin film, good adhesion, moderate mechanical properties. But: low porosity; limited thickness |

| Electrochemical deposition | Compact, crystalline coating, good adherence, tailored thickness, scalable coats on complex shapes But: requires conductive substrate; limited polymer use; poor porosity and mechanical properties. |

| Electrophoretic deposition | Uniform and dense coating, good adhesion, moderate porosity, and scalable coats on complex shapes. But: cracking risk; requires stable suspension; poor mechanical properties. |

| Element | Effect |

|---|---|

|

Influence both osteoblast (bone-forming cells) and osteoclast (bone-resorbing cells) activity. |

| Repair bone defects and promote osseointegration | |

| Mimic calcium ion (Ca²⁺) and modulate key signaling pathways involved in bone formation and resorption. | |

| Enhanced bone formation due to osteoblast stimulation. | |

| Reduced bone resorption by inhibiting osteoclastogenesis. | |

| Improved bone mineral density (BMD) and fracture healing. | |

| Favorable effects on metabolic energy balance, supporting bone tissue homeostasis. | |

|

Enhance immunomodulation, angiogenesis, and vascularized osteogenesis in bone defect areas. |

| Promote osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. | |

| Facilitate osteoblast adhesion and matrix mineralization. | |

| Accelerate HAp nucleation kinetics | |

| Regulates calcium homeostasis, essential for hydroxyapatite formation. | |

| Inhibits osteoclast activity | |

| Essential cofactor for ATP production, supporting osteoblast energy demands | |

|

Enhance bone metabolism, cell proliferation, and tissue regeneration. |

| Significant role in bone tissue's normal development and maintaining homeostasis. | |

| Enhance ossification in stem cells. | |

| Promote osteogenesis and mineralization and confer antibacterial properties. | |

| Key transcription factor in osteoblast differentiation. | |

| Increasing osteogenic gene expression. | |

| Inhibits osteoclast differentiation | |

| Boosts protein synthesis. | |

|

Facilitate human cell adhesion and differentiation. |

| Induce angiogenesis, collagen type I, and osteocalcin expression. | |

| Enhance bone matrix quality | |

| Promote osteoblast differentiation | |

| Support hydroxyapatite crystallization and mineralization. | |

| Improve mitochondrial respiration in osteoblasts | |

| Enhance nutrient transport via silicon-mediated ion exchange | |

|

Essential for collagen cross-linking, aiding in bone matrix stability |

| Promote vascularization in bone healing. | |

| Affecting osteoblast proliferation. | |

| Excess iron ions can increase oxidative stress, inducing osteoclastogenesis. | |

|

Promote angiogenesis. |

| Improve vascularization in bone grafts. | |

| Stimulate osteogenic differentiation. | |

| Excess Co can cause oxidative stress, leading to cytotoxicity at high concentrations | |

|

Stimulate angiogenesis |

| Increase collagen synthesis and cross-linking, improving bone matrix | |

| crucial for bone stability. | |

| Excess Cu can generate reducing oxidative stress (ROS), potentially leading to cytotoxic effects. | |

| Slight antibacterial effect | |

|

Exhibit antimicrobial properties, preventing infection in bone implants. |

| Stimulates osteoblast proliferation at low concentrations. | |

| Inhibit osteoclast differentiation, balancing bone resorption. | |

| Disrupt bacterial metabolism without significantly affecting osteoblasts at low doses | |

| Alter mitochondrial function, potentially inducing apoptosis at high concentrations. |

| Brand name | Description | Application | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medpor®-Plus™ | Standard MEDPOR (biocompatible porous polyethylene particles) combined with bioactive glass (Bioglass®) mixture. | Orbital implants |

[240] |

| NovaBone® Perioglass |

100% synthetic and resorbable calcium phosphosilicate dental putty. | Dentistry, Orthopedics |

[241] |

| Smart Healing™ | S53P4 bioactive glass. Used for filling defects and replacing damaged bone tissue. | Orthopedics, Bone filler Spine surgeries |

[242] |

| Cortoss® | Injectable, bioactive composite material that mimics the mechanical properties of human cortical bone. | Orthopedics Osteoporosis |

[243] |

| Glassbone™ | Bioactive glass 45S5 ceramic composite used in regenerative medicine as a synthetic bioactive bone substitute. | Orthopedics Bone filler |

[244] |

| StronBone™ | Strontium containing bioactive ceramics or biomimetic fibrous polymer scaffolds. | Orthopedics Bone Graft Bone substitute, Craniomaxillofacial |

[245] |

| OssiMend® | Osteoconductive, bioactive bone graft matrix. Components: 50% carbonate apatite anorganic bone mineral, 30% 45S5 Bioactive Glass and 20% Type I Collagen | Orthopedics Spine surgery |

[246] |

| GlaceTM | Fiber-glass material that used in post-traumatic surgery and for surgical bone reconstructions of the cranial and maxilofacial regions, including the orbital floor. | Orthopedics Spine surgery, Orbital implants |

[247] |

| Signafuse® | A composite of biphasic minerals and bioglass. Composition: bioglass and a biphasic mineral (60% hydroxyapatite, 40% β-tricalcium phosphate). |

Orthopedics, Spine surgery, Cervical fusion, Lumbar fusion, Bone grafts |

[248] |

| NovaMin® | The original Bioglass® 45S5 | Orthopedics, Bone filler Bone graft |

[249] |

| RediHeal™ RediHeal Ointment RediHeal Dental |

Borate-based bioglass with unique trace elements. As an ointment, it treats topical soft tissue damage, minor abrasions, skin irritations, skin ulceration, burns, and scratches in humans and animals. |

Veterinary Wound healing, ointment |

[250] |

| OsteoGlass® | It has been designed with nano- and mesopores to promote osteoblast attachment and to allow blood vessels to grow through the scaffold and gradually degrade over the same timeframe as the new bone is formed. | Orthopedic Dental Skin treatment Wound healing |

[251] |

| Brand Name | Description | Application | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eurobone® 2 | Synthetic bone substitute, paste granules with a composition of 75% HA / 25% β-TCP | Orthopedic (Non-load-bearing applications) |

[254] |

| Neobone® | Synthetic bone substitute, putty, is an injectable synthetic bone substitute used to fill defects without mechanical strength. | Orthopedics, Dentistry, Bone grafts Bone substitutes |

|

| Ostibone® | |||

| NANOGEL® | Synthetic bone substitute. Absorbable bone void filler that provides support for bone ingrowth. Hydroxyapatite particles between 100 nm to 200 nm. | Orthopedic, Dental | |

| SKUHEAL™ SM-C | Biomimetic mineralized collagen synthetic bone graft material: It contains type I collagen and nano-hydroxyapatite. |

Orthopedics Skull surgery Maxillofacial surgery |

|

| HydroSet XT | Injectable, self-setting bone substitute composed of tetra-calcium phosphate that is formulated to convert to hydroxyapatite, the principal mineral component of bone. | Orthopedics Bone filler |

[243] |

| DirectInject | The first and only on-demand, self-setting HAp cement. It is used to repair neurosurgical burr holes, contiguous craniotomy cuts and cranial defects. | Orthopedics neurosurgery Bone filler |

|

| Vitoss® | Beta-tricalcium phosphate and bioactive glass. Available in many forms such as moldable packs, malleable strips, and morsels. | Orthopedic Bone graft |

|

| Osteoset® | Resorbable CaP ceramic that consists of synthetic calcium sulfate beads for bone grafting, calcium sulfate | Bone graft | |

| Calcigen® | Synthetic calcium sulfate particles for bone grafting, calcium sulfate | Bone Void Filler () | [255] |

| ProOsteon® | Porous hydroxyapatite particles that are osteoconductive and have a structure and chemistry similar to human bone | Orthopedics Bone grafts |

|

| BonePlast® | Medical bone void fillers. Calcium sulfate powder, resorbable, extrudable, and moldable bone void fillers |

Bone graft Bone filler |

|

| Norian ®SRS, Norian ®CRS | An injectable, moldable, and biocompatible bone void filler. It contains calcium phosphate powder and sodium phosphate. | [256] | |

| ChronOSTM Inject | Synthetic calcium phosphate bone substitute, injectable, osteoconductive, and resorbable. Irregular bone defects can be completely filled. It consists of a brushite matrix and tricalcium phosphate granules | ||

| Neocement® | Calcium phosphate cement is intended for filling of bone defects of the skeletal system | Orthopedics Traumatology |

[257] |

| Biopex®-R | Calcium phosphate cement which consists of powder and liquid components. | bone tissue replacement. | [258] |

| Apaceram | Synthetic hydroxyapatite that has macro pores and micro pores. Macro pores are effective for new bone formation, while micro pores provide interconnectivity of the pores. | ||

| Superpore | It has a unique “triple pore structure”. Contains APACERAM Type-AX to absorbable tricalcium phosphate ceramics. |

||

| JectOS® TCH TCP Dental HP |

Partially biodegradable cement with a composition of 45% TCP and 55% DCPD. Used to fill cancellous bone defects. | [259] | |

| CERAFORM® | Biocompatible synthetic biphasic ceramic made of hydroxyapatite and beta tricalcium phosphate. | [260] | |

| Cerasorb® | Resorbable, pure-phase β-tricalcium phosphate with an interconnecting, open multi-porosity. | Implantology Sinus floor elevation General grafting |

[261] |

| Bonetree® | Octacalcium phosphate (OCP)-based synthetic bone substitute material | Ortopedics Dentistry Bone graft |

[262] |

| MBCP® | Bioactive mixture of highly crystalline HAp and β-TCP (Tri Calcium Phosphate)- | Ortopedics Dentistry Bone graft |

[263] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).