1. Introduction

Subtle variations in the global carbon cycle can lead to significant fluctuations in atmospheric CO

2 concentrations, thereby influencing the stability of the global climate [

1,

2,

3,

4]. To mitigate the greenhouse effect and combat global warming, it is essential to develop a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms that govern the global carbon cycle, including its sources, sinks, and their spatio-temporal distributions [

5,

6]. Previous research has extensively focused on terrestrial carbon sinks, particularly in relation to forest carbon sequestration and agricultural soil erosion sinks [

7,

8,

9]. However, even after accounting for net forest carbon sequestration within terrestrial carbon sink systems, the global carbon cycle remains unbalanced, highlighting the well-documented phenomenon known as the "carbon sink missing" [

1,

2,

10]. Recently, carbonate weathering has emerged as a crucial component of the global carbon sink system, significantly influencing the regulation of global climate change [

4,

5,

11,

12]. Through biogeochemical processes such as the global water cycle and aquatic photosynthesis, the dissolution of carbonate rocks contributes to carbon sequestration over both short and long time scales, potentially addressing the gaps in the global carbon sink framework [

11,

12]. During the weathering-induced dissolution process, carbonate rocks absorb atmospheric CO2. Compared to other minerals, carbonate minerals exhibit a higher susceptibility to dissolution, thereby providing substantial carbon sequestration capacity [

5,

8,

11,

12,

13]. As carbonate weathering serves as a vital pathway for reducing atmospheric CO

2 and maintaining equilibrium between carbon sources and sinks, understanding its processes is critical for research on global climate change and achieving carbon neutrality goals.

Extensive research has been conducted on carbonate weathering, leading to significant advancements in understanding weathering rates, soil formation, and mineralization dynamics [

12,

14,

15,

16]. Traditional studies have relied on weathered soil profiles to elucidate elemental migration patterns during the weathering process [

12,

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, the intense weathering of carbonate rocks often makes it challenging to preserve the incipient weathering layer within soil profiles, thereby hindering researchers' ability to grasp the incipient weathering process and impeding a comprehensive understanding of carbonate weathering mechanisms [

11,

12,

17,

18]. We propose the hypothesis that, in addition to soil profiles, surface/spheroidal weathered carbonate rocks that have been directly affected by surface weathering can also serve as valuable records of weathering processes, particularly incipient weathering. The mineralogical and geochemical characteristics of surface-weathered carbonate rocks may undergo changes during incipient weathering, thus documenting fluid sources and environmental alterations throughout those processes. With advancements in in-situ analytical techniques, we are now able to investigate the detailed mineralogy, geochemistry, and isotopic geochemistry of surface-weathered carbonate rocks, from core to rim, to elucidate the processes and mechanisms involved in carbonate incipient weathering.

Consequently, this study collected lenticular, surface-weathered carbonate rocks from the Datangpo region in Zhaiying Town, Songtao County, Guizhou Province, China. Comprehensive investigations were conducted into the mineralogy, geochemistry, and isotopic geochemistry to explore the processes associated with carbonate incipient weathering.

2. Geological Setting

The study area is located in the Datangpo region of Songtao County, Guizhou Province, China. Geologically, it lies at the intersection of the southeastern margin of the Yangtze Block, within the Nanhua Basin, and the Jiangnan Orogenic Belt (

Figure 1a &

Figure 1b).

This extensional basin was formed as a consequence of the global breakup of the Rodinia supercontinent [

19,

20,

21]. The basin contains a series of carbonate rocks, including rhodochrosite and dolomite [

20]. The stratigraphic sequence in the study area is part of the Nanhua System (

Figure 1b), which includes the following formations, listed from oldest to youngest: Liangjiehe Formation, Tiesiaoao Formation, Datangpo Formation, and Nantuo Formation [

19]. An angular unconformity is observed between the Liangjiehe Formation of the Nanhua System and the underlying Banxi Group of the Qingbaikou System [

22]. The Nantuo Formation of the Nanhua System is in para-unconformity contact with the Doushantuo Formation [

23]. The low-temperature sedimentary sequence of the Nanhua System records two glacial events. The mixed rocks and sandstones of the Liangjiehe and Tiesiaoao Formations are indicative of the Sturtian glaciation (~720-663 Ma), which is characterized by poor roundness [

22]. In contrast, the glaciomarine mixed rocks, siltstones, and sandstones of the Nantuo Formation document the Marinoan glaciation (~654-635 Ma), with thicknesses ranging from 60 to 200 meters [

20,

21]. The Datangpo Formation, consisting of interglacial sediments deposited between the Sturtian and Marinoan glaciations, spans approximately 10 million years (~663-654 Ma) and is conformably in contact with both the underlying Tiesiaoao Formation and the overlying Nantuo Formation, exhibiting a thickness that varies between 30 and 700 meters [

20,

21].

3. Material and Method

The samples used in this study were primarily obtained from the Liangjiehe and Datangpo Formations (

Figure 1). These samples include unaltered dolomite and surface-weathered dolomite from the Liangjiehe Formation, as well as carbonaceous mudstones from the Datangpo Formation (

Figure 1 &

Figure 2).

Within the sandstone of the Liangjiehe Formation, a lenticular dolomite measuring approximately 126 cm in length and 32 cm in width was identified (

Figure 1f). Its surface displays a reddish-brown weathering crust with a laminated texture (

Figure 2a &

Figure 2b). Upon striking the weathered surface with a hammer, the interior reveals a bluish-gray coloration, and the rock effervesces upon contact with hydrochloric acid, indicating the presence of carbonate minerals.

The Chemical Index of Alteration (CIA) is commonly used as a weathering index; however, due to the high calcium content in carbonate rocks and the low aluminum and potassium contents, this study does not employ the CIA to differentiate between various stages of weathering. Based on visual characteristics, degree of rock fragmentation, changes in mineral composition, alterations, and physical-mechanical properties, two distinct stages of incipient weathering were observed in the dolomite samples (

Figure 2a &

Figure 3b).

Stage I is characterized by brownish-yellow dolomite with a loose texture and occasional fractures. In contrast, Stage II is represented by reddish-brown dolomite, which exhibits a slightly looser texture, systematically arranged fractures, and sporadic quartz grains dispersed throughout the matrix.

3.1. Petrographic Observation

After samples collection, the surface-weathered carbonate rocks were sectioned longitudinally from the exterior to the interior to reflect the varying stages of incipient weathering. Those sections were prepared using the Struers Labotom-15 cutting machine, selecting appropriate cross for sectioning. These were then flattened and polished with the Struers Tegramin polisher. Crystal Bond was applied to adhere the polished setions to glass slides, followed by cutting 200 μm sub-sections with the Struers Accutom-50 and final polishing to a thickness of approximately 40-60 μm.

After preparation, these sections were photographed using a stereo microscope (Leica EZ4W) to identify incipient weathering stages for further analysis. Polarizing microscopy (Zeiss Scope.A1) was employed to observe and document the characteristics and positions of different incipient weathering stages at these sections.

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

To elucidate mineral phase variations across different incipient weathering stages, SEM-EDS analysis was performed. SEM experiments were conducted at the Guangdong Marine Resources and Coastal Engineering Laboratory, where gold-sputtered samples were mounted on conductive tape and placed in the evacuated chamber of a VEGA3 TESCAN field-emission SEM. Images were captured in backscatter mode at 20 kV and 1 nA, with a scan speed of approximately 90 s per image. EDS spectra, acquired for approximately 20 s each, aided in mineral identification.

3.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Mineral Identification

XRD of whole-rock powder samples determined mineral content changes at different weathering stages. For whole-rock XRD, about 50mg of powder is drilled with a dental drill. The powder is ground to below 200 mesh with an agate mortar, placed on a slide, flattened, and then tested by XRD. The whole-rock XRD is performed on a PANalytical X'Pert Pro MDP with a Cu target, at 60 kV, 55 mA, covering 6- 50° (2θ), with a step size of 0.02°/s. XRD data is collected via X'pert Data Collector and analyzed using HighScore Plus for mineral phase identification.

Micro-XRD analysis was conducted to identify mineral phase changes associated with varying incipient weathering stages. Rocks containing Original、Stage I and Stage II were selected and sliced to a thickness about 100 mm. The rock slices were attached to glass fiber tubes. The rotation range of the platform was adjusted. Under the lens, the dolomite matrix at different weathering stages was located in situ for XRD diffraction experiments.The D/MAX RAPID II XRD instrument, equipped with a Mo radiation, operated at 50 kV and 30 mA, scanning diffraction angles from 2° to 44° at a step size of 0.02°/s. Diffraction patterns were converted to angle-intensity series using 2DP software, and mineral identification was performed with the

PDXL software provided by Rigaku Corporation [

24,

25].

3.4. Trace and REEs Analysis

To elucidate the migration of elements during weathering processes, this study employed LA-ICP-MS to quantify the elemental contents. Given that carbonate rocks primarily consist of Ca(Mg)CO

3, the major elements of focus were Ca and Mg. Additionally, considering the established correlation between carbonate rocks and manganese deposits in the Datangpo area, where carbonate lens occurrences are often accompanied by manganese ore layers [

20,

21], the study also investigated the contents of Mn and Fe. To track the changes in redox conditions and REEs content during the weathering process, the contents of Ni, Co, and REEs were also tested.

In-situ LA-ICP-MS analysis was performed. Samples were analyzed using the GeoLas Pro 193-nm ArF excimer laser ablation system coupled with an Agilent 7900 ICP-MS. Helium was used as the carrier gas, with a spot size of 32 μm, energy density of 5 J/cm², and repetition rate of 5 Hz. NIST610 and NIST612 served as external standards for trace element calibration every ten points, and data were processed using Iolite software.

3.5. Carbon and Oxygen Isotope Analysis

To facilitate a more comprehensive comparison and analysis of carbon and oxygen isotope, this study additionally collected unaltered dolomite in the study strata and carbonaceous mudstones from the Datangpo Formation strata for carbon and oxygen isotope testing. The unaltered dolomite were collected to serve as a reference for primary mineral and geochemistry characters. The carbonaceous mudstones were sampled to investigate potential links between weathering and manganese mineralization (

Figure 1d &

Figure 2g &

Figure 3a).

Each samples, approximately 200 μg , were drilled in situ using a dental drill, powders were loaded into glass tubes, evacuated with high-purity helium, and reacted with 100% pure phosphoric acid for 24 hours to convert it to CO2 [

26,

27,

28,

29]. The GasBench II system was used to introduce the gas into a Thermo Scientific 253 Plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer for analysis. Calibration was performed using the international standard NBS-18 (δ¹³C = -5.014‰, δ¹⁸O = -23.2‰), and results were reported in δ units (‰) relative to the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (V-PDB) standard.

3.6. Calculate method

Migration coefficient

To represent elemental accumulation and depletion, migration coefficient were calculated by using the formula :

RE = (X - Y) / Y (1)

where X represents the average elemental content in the current stage, and Y represents the average elemental content in pristine dolomite. Given the heterogeneity of carbonates and potential measurement errors associated with instrumentation, elements with an absolute RE value greater than 0.5 were defined as significantly depleted/enriched.

Cerium (Ce) anomaly

The Ce anomaly, a commonly used indicator in REEs studies, serves to distinguish redox environments [

30,

31,

32]. In this research, the Ce anomaly is calculated using the formula:

Ce/Ce* = 2CeN/(LaN + PrN) (2)

where N represents normalization values based on the Post-Archean Australian Shale (PAAS) [

33].

4. Result

4.1. SEM and Microscope

Under SEM, pristine dolomite exhibits a denser texture with a dolomite matrix and occasional quartz grains (

Figure 4a). When examined under optical microscope, pristine dolomite appears bluish-gray, with a fine-grained and compact microcrystalline dolomite matrix, intercalated with occasional quartz grains (

Figure 4d).

SEM exhibits that dolomite in Stage I has a relatively loose matrix composed of a mixture of dolomite and weathering residue, with occasional fractures filled with calcite (

Figure 4b). Microscopically, dolomite in Stage I is predominantly yellowish-brown, with a matrix comprising creamy fine-grained dolomite and yellowish-brown fine-grained weathering residues (

Figure 4e). Occasional fractures are filled with creamy calcite, displaying yellowish-brown hues.

SEM analysis of dolomite in Stage II indicates an even looser matrix, dominated by weathering residues with lesser dolomite and more frequent quartz grains (

Figure 4c). Fractures are wider and primarily filled with weathering residues. Under microscope, dolomite in Stage II appears yellowish-brown to reddish-brown, with quartz grains more prevalent, a yellowish-brown weathering residues matrix, and occasional creamy dolomite remnants (

Figure 4f). Fractures are predominantly filled with pale yellow material.

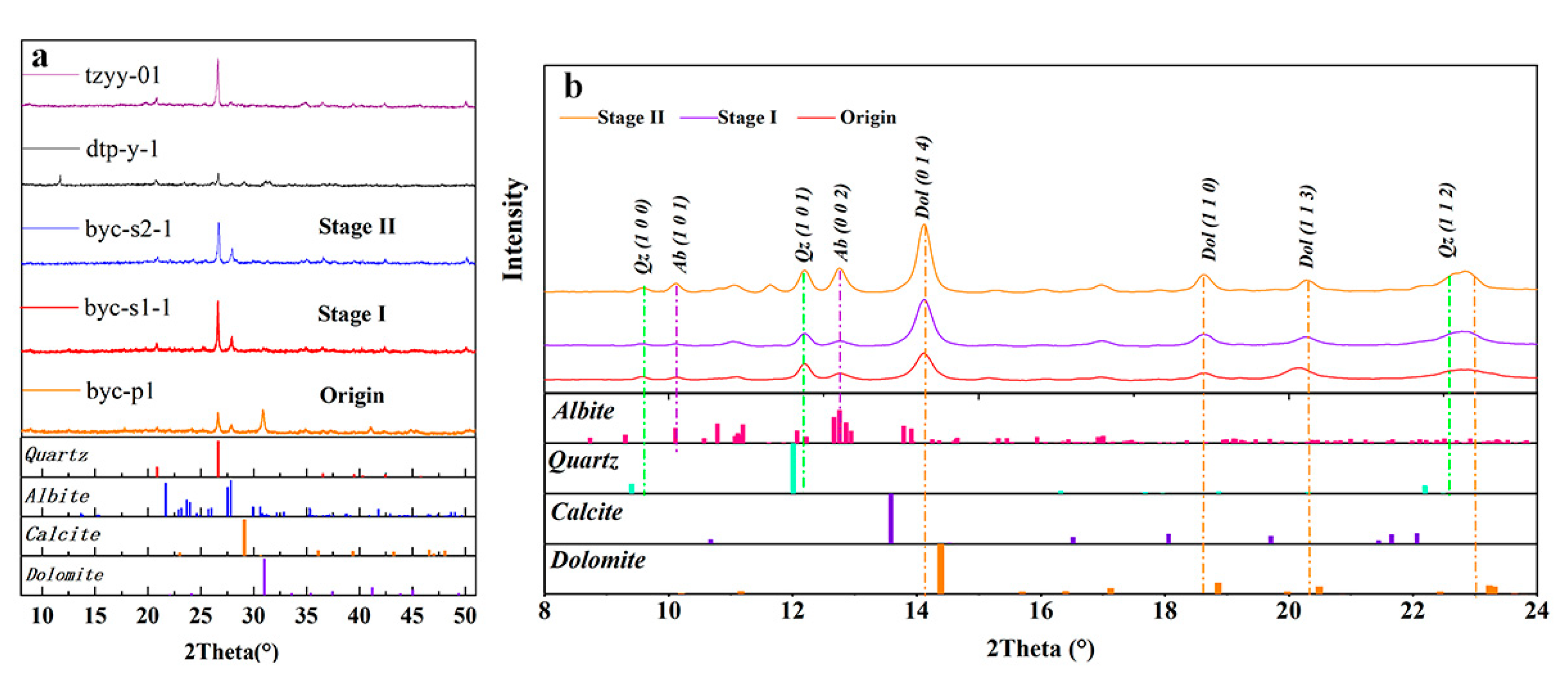

4.2. XRD Pattern

By comparing the XRD data with standard mineral cards(PDF-2024), three minerals were identified: dolomite, quartz, and feldspar. The prominent peaks of dolomite (1 1 ), (1 1 3), and (1 1 0) were all detected in the XRD spectra, along with the strong quartz peaks (1 0 1), (1 0 0), and (1 1 2). The intense peak of feldspar (0 0 2) was also present, confirming the presence of dolomite, quartz, and feldspar as the dominant minerals in the rock. Notably, the quartz peak intensities follow the trend Origin < Stage I < Stage II (

Figure 5), consistent with SEM and microscopic observations, indicating an increase in quartz content from pristine dolomite to Stage II. As the degree of weathering intensifies increase, the content and peak intensities of feldspar increase.

In-situ XRD identified that the peak position of dolomite (1 1 ) at different weathering stages didn't change significantly, which indicates that the dolomite matrix's mineral phase remained stable, with only dissolution occurring.

4.3. LA-ICP-MS Data

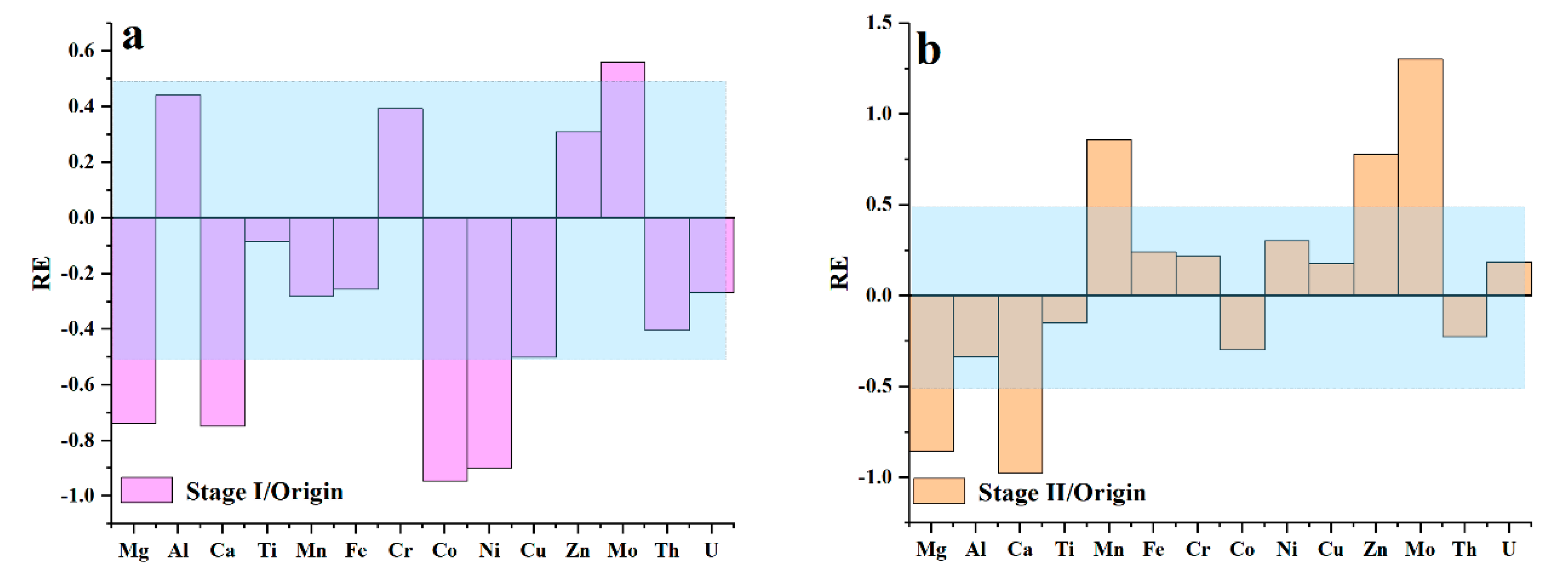

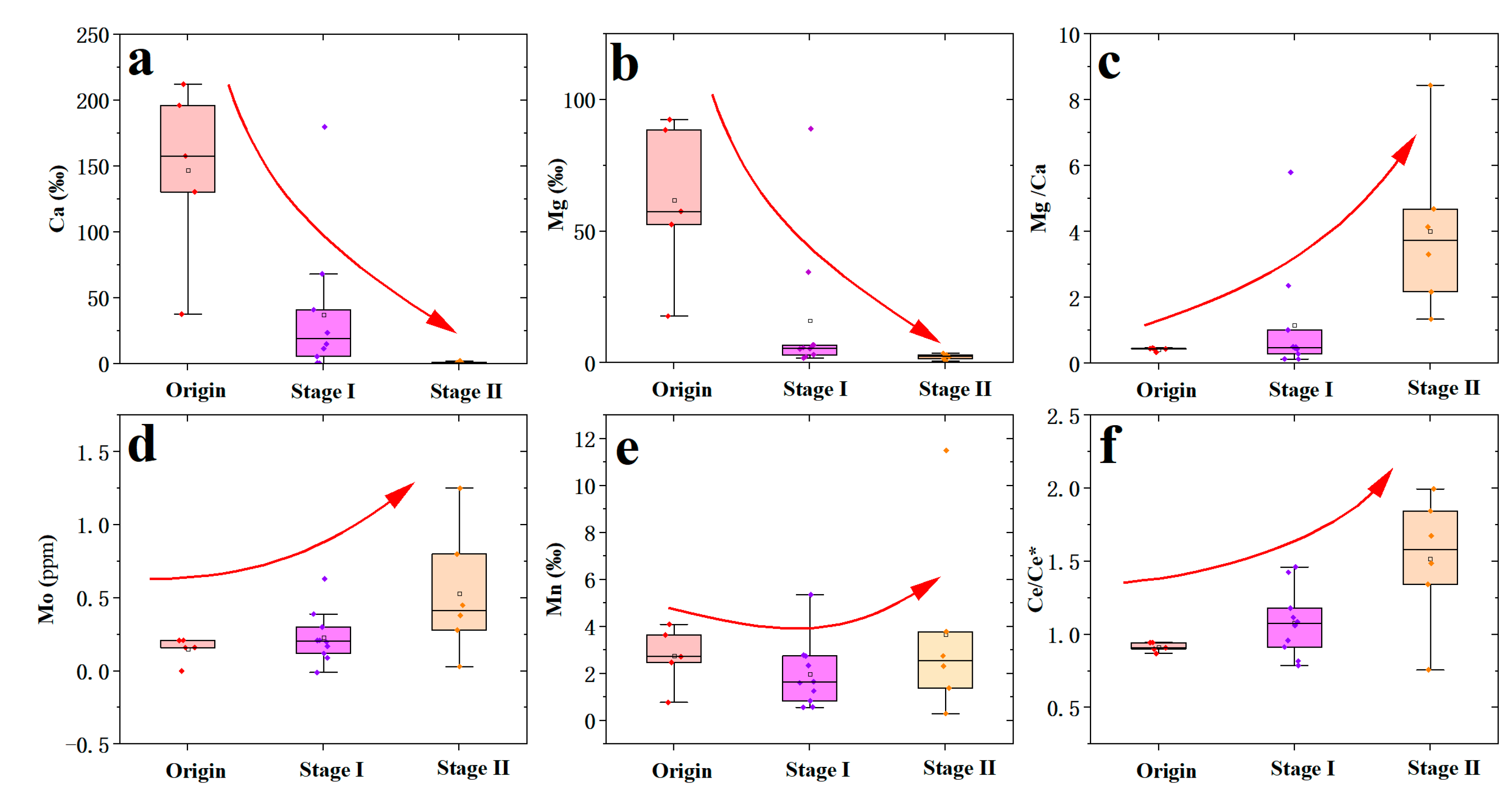

In Stage I, notable depletion was observed for Mg, Ca, Co, and Ni, while significant enrichment was evident for Mo (

Figure 6a &

Figure 7).

In Stage II, notable enrichment was observed for Mn, Mo, and Zn, while significant depletion was evident for Mg and Ca (

Figure 6b &

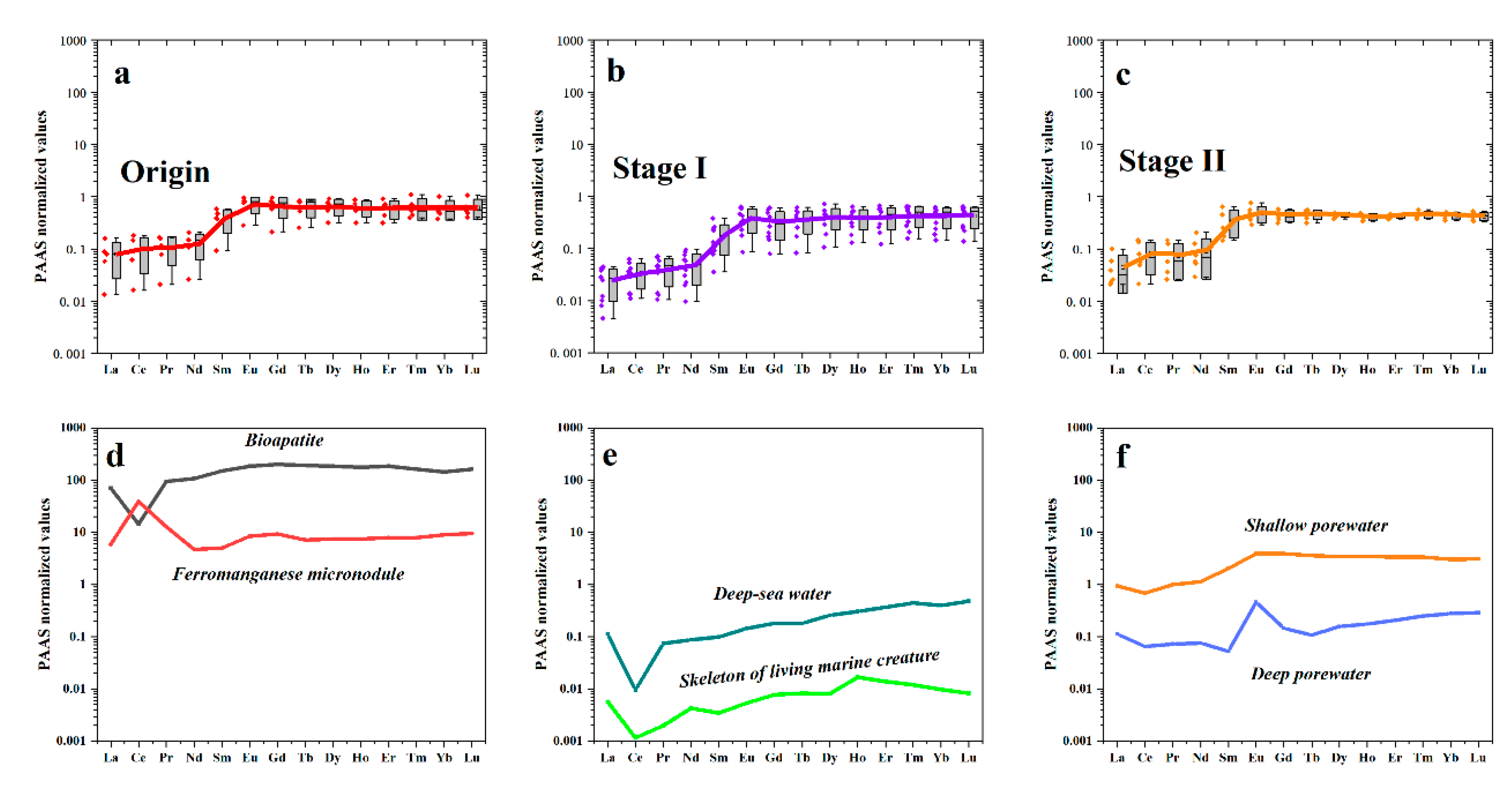

Figure 7). The REEs patterns in Origin, Stage I, and Stage II exhibit similar trends (

Figure 8), with the ratio of light REEs (LREEs) vs. heavy REEs (HREE) varying minimally (Origin =3.74 ppm, Stage I = 2.86 ppm, Stage II = 3.21 ppm) (

Table 1).

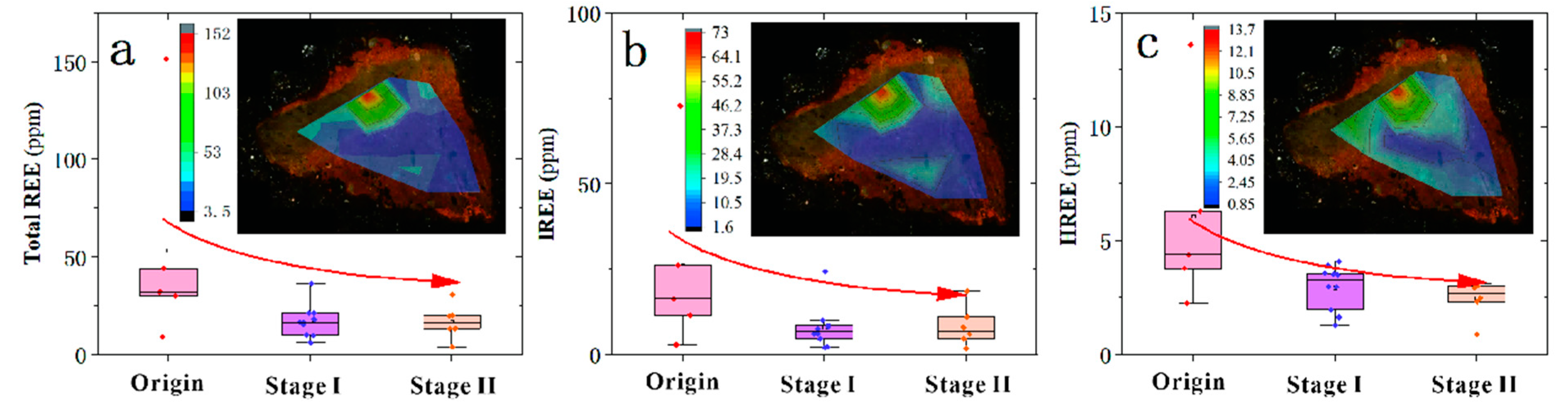

This indicates that significant fractionation of REEs did not occur during the weathering process. The total REEs content exhibits a trend of initial decrease followed by an increase, as evident from the REEs distribution map (

Figure 9).

Specifically, higher REEs concentrations are observed in the pristine dolomite, which decrease in Stage I, and then slightly increase again in Stage II (

Table 2). The overall Ce anomaly ranges from 0.76 to 1.99. Notably, a significant increase in the Ce/Ce* ratio is observed from Orgin to Stage II (

Figure 7f).

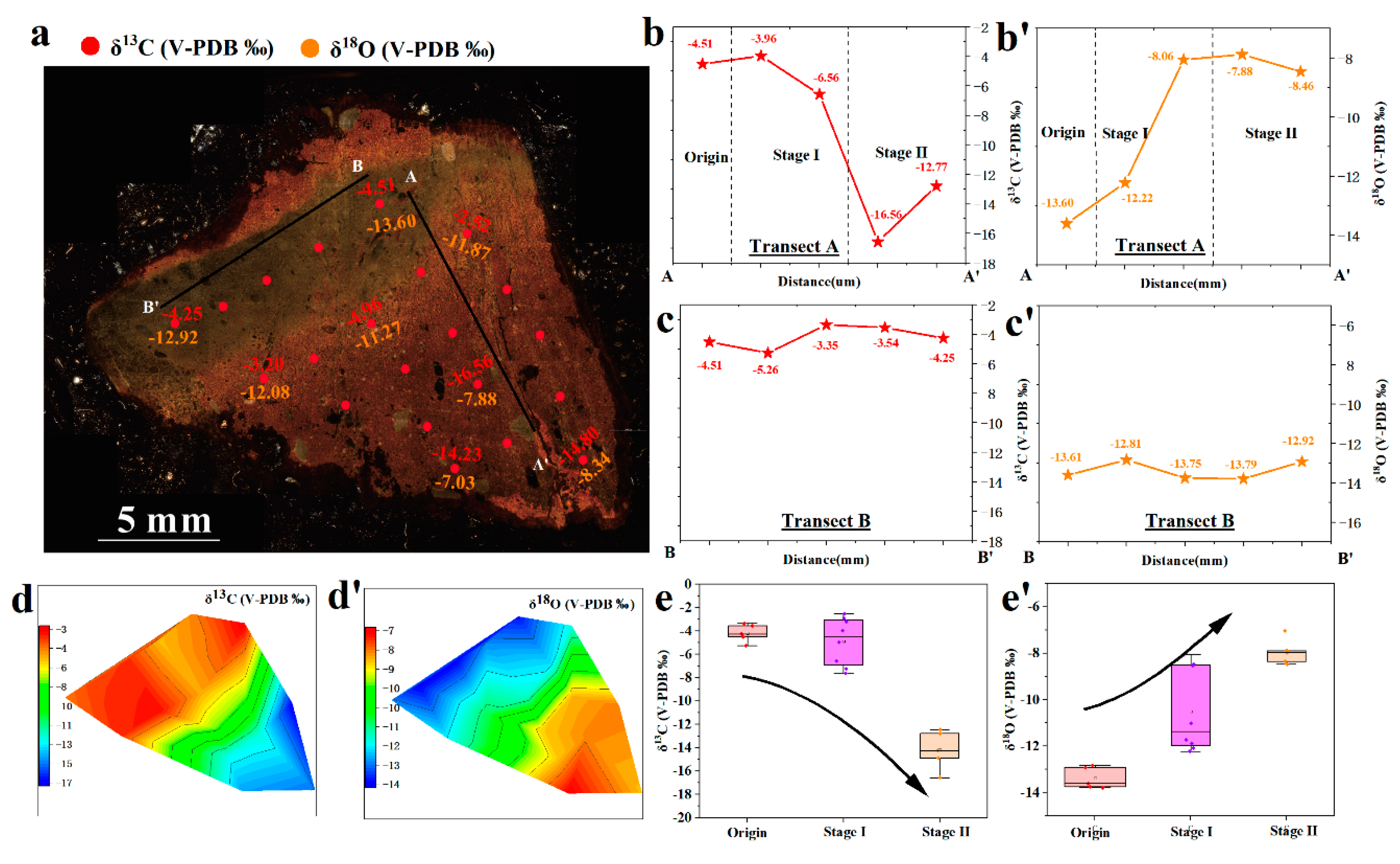

4.4. Carbon and Oxygen Isotopes

The δ

13C values of the pristine dolomite ranged from -6.07 to -2.76‰, with an average of -3.99 ‰, while the δ

18O values ranged from -14.73 to -12.40‰, averaging -13.32‰. For the carbonaceous mudstones, the δ

13C values ranged from -9.65 to -7.99‰, averaging -8.55‰, and the δ

18O values ranged from -13.63 to -10.35‰, averaging -11.68 ‰ (

Table 3).

The surface-weathered carbonates were categorized into three zones: Origin, Stage I, and Stage II. Origin zone exhibited δ

13C values ranging from -5.26 to -3.35‰, averaging -4.18‰, and δ

18O values ranging from -13.79 to -12.83‰, averaging -13.38 ‰, consistent with the isotopic signatures of the pristine dolomite. Stage I showed δ

13C values ranging from -7.61 to -2.52‰, averaging -4.87‰, and δ

18O values ranging from -12.22 to -8.06‰, averaging -10.49‰. Stage II displayed δ

13C values ranging from -16.56 to -12.43‰, averaging -14.17 ‰, and δ

18O values ranging from -8.46 to -7.03‰, averaging -7.93 ‰ (

Figure 10).

5. Discussion

During the weathering of carbonates, a dissolution reaction of carbonates occurs, with the reaction equation as follows:

CaCO3(s)+CO2(g)+H2O(l)⇌Ca2+(aq)+2HCO3−(aq) (3)

This is a reversible reaction process. Under laboratory conditions, the reverse reaction easily occurs, releasing CO

2 again. However, in natural conditions, the addition of exogenic waters such as atmospheric precipitation and surface runoff dilutes HCO

3- and Ca

2+, preventing the reaction from reaching equilibrium [

34]. During the weathering process, CO

2 is converted into the form of HCO

3-, which is transported to the ocean, rivers, aquatic plants, and caves where it is sequestered, with only a small portion being re-released [

9,

35]. Carbonate weathering contributes approximately 0.5–0.9 Pg C yr

−1 to the global carbon cycle, which is about 0.45–0.82 times that of forest ecosystem carbon sinks [

36,

37]. Therefore, carbonate weathering is considered an important missing carbon source. There have been many studies on the weathering mechanisms of carbonate, but the main research subjects currently used are carbonate weathering soil profiles, which do not well characterize the detailed processes of carbonate incipient weathering [

11,

16,

17,

18]. This study takes the surface-weathered carbonate as the research object and explores in detail the transformation of mineral phases, migration of elements, and isotopic changes during the incipient weathering process of carbonates.

5.1. Minerals Phase Transformation

During the weathering of carbonate rocks, carbonate minerals such as calcite and dolomite undergo dissolution, releasing calcium ions. These ions can react with CO

2 in water to form bicarbonates, which may subsequently re-precipitate to form new calcium carbonate or other minerals [

9,

35]. Concurrently, the weathering process leads to the dissolution of soluble minerals, resulting in the formation of secondary minerals such as gypsum and clay minerals, thereby altering the mineral composition of the rock [

36,

37]. Furthermore, weathering induces changes in the rock's structure, affecting its physical properties, including porosity and permeability.

In this study, we investigated surface-weathered carbonate rocks using SEM and microscopy observations. The results revealed that the dolomite matrix becomes increasingly porous and friable with heightened weathering intensity. Enhanced fracturing of the rock was observed, with fractures filled by calcite veins and weathering residues. These microstructural alterations indicate the partial dissolution of carbonate minerals during incipient weathering, leaving behind weathering residues that compromise the structural integrity of dolomite. Elemental analysis demonstrated a significant depletion of Ca and Mg (greater than 70%) in both Stage I and Stage II weathering phases compared to pristine dolomite, providing evidence of extensive dolomite dissolution during the initial weathering processes. XRD analysis of bulk powdered samples revealed a marked increase in the relative abundance of detrital minerals (quartz and feldspars), coinciding with the near-complete disappearance of dolomite diffraction peaks in the weathered stages. This mineralogical evidence confirms a dissolution-dominated weathering process with the accumulation of residues. In-situ XRD analysis of residual dolomite grains within the matrix showed preserved dolomite crystallinity without any species transformation, demonstrating that incipient weathering occurs primarily through dissolution rather than mineralogical alteration.

Regarding the pedogenic hypotheses of carbonate-derived terra rossa formation, two prevailing genetic models have been proposed [

34]: (1) the residual accumulation model, which involves the accumulation of insoluble components resulting from carbonate dissolution, and (2) the fluid-mediated metasomatic neoformation model. Our data, which indicate more than 80% depletion of Ca and Mg coupled with the complete dissolution of dolomite in bulk XRD patterns (while maintaining the original rock volume through increased porosity), support the residual accumulation hypothesis. The preservation of the rock framework, along with enhanced secondary porosity, suggests that the formation of terra rossa predominantly results from in-situ accumulation of insoluble residues rather than metasomatic replacement processes.

5.2. Mobility of Elements

The elemental migration patterns observed across the stages of carbonate incipient weathering in this study can be summarized as follows: In Stage I, there was a substantial depletion of Ca and Mg exceeding 70%, accompanied by a significant reduction in Co and Ni, alongside a decrease in total REEs content and an enhanced Ce anomaly. Transitioning to Stage II, Ca and Mg continued to exhibit marked depletion; however, Co and Ni concentrations did not show statistically significant reductions compared to pristine dolomite. This stage was characterized by a pronounced enrichment of Mn, Zn, and Mo, as well as a slight increase in total REEs content relative to Stage I, with a further intensification of the Ce anomaly. These systematic geochemical variations demonstrate stage-dependent elemental mobility during weathering processes, highlighting differential leaching behaviors between major cations (Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺) and transition metals under evolving redox conditions.

Ca and Mg are the primary compositional elements of dolomite, forming the fundamental structural framework of the mineral through their coordination with carbonate groups within the lattice. The similar depletion rates of Mg and Ca (REMg = -0.74; RECa = -0.75) suggest that the depletion of these elements in Stage I is likely attributable to the dissolution of dolomite (where the Mg:Ca ratio is approximately 1:1), a finding corroborated by petrographic observations of a disaggregated dolomite matrix resulting from dissolution. The ongoing depletion of Mg and Ca in Stage II (REMg = -0.85; RECa = -0.98), with a greater degree of depletion observed for Ca compared to Mg, can be attributed to the continued reaction of reprecipitating carbonate minerals with water and air, leading to further loss of Ca.

The geochemical properties of Co and Ni indicate their solubility in acidic oxidizing environments and precipitation under alkaline conditions [

42]. The depletion of Co and Ni in Stage I may be attributed to the formation of H₂CO₃ through the reaction between water and CO₂, resulting in a more acidic environment and the subsequent leaching of these elements via weakly acidic fluids. The lack of further significant depletion of Co and Ni in Stage II suggests an increase in the pH of the acidic fluid, potentially due to the reaction of dolomite with water and CO₂ to generate HCO₃⁻, leading to elevated HCO₃⁻ concentrations and an increase in pore water pH.

Mo enrichment in oxic environments is primarily regulated by adsorption or co-precipitation with manganese oxides[

43,

44,

45]. In contrast, under anoxic or suboxic conditions, the concentration of hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) in the aqueous solution governs Mo behavior, with elevated H

2S levels promoting Mo precipitation [

43,

44,

45]. Considering the oxidative environment of dolomite during weathering and the notable enrichment of both Mn and Mo in Stage II, it is likely that Mo enrichment during the incipient weathering process results from co-precipitation with manganese oxides. Zinc ions also tend to adsorb onto the surfaces of manganese oxides and subsequently precipitate [

46], indicating that Zn enrichment in Stage II may be associated with Mn enrichment. Furthermore, variations in pH can affect Mn precipitation, which is more prevalent under neutral or near-neutral conditions [

47,

48]. This phenomenon occurs because Mn(II) is more readily oxidized to insoluble Mn(III) or Mn(IV) oxides under these conditions [

47,

48]. Consequently, the enrichment of Mn in Stage II is likely attributable to the reaction of Mn(II) in the fluid with atmospheric oxygen following an increase in fluid pH. Conversely, the absence of significant Mn enrichment in Stage I may be due to excessively low pH values. The Mn(II) present in pore water likely originates from the overlying Datangpo manganese ore deposits [

22].

In summary, as weathering progresses from Stage I to Stage II, there is a notable decrease in Ca and Mg contents, accompanied by a significant increase in the Mg/Ca ratio (

Figure 6 &

Figure 7). The reduction in Mg and Ca is attributed to the dissolution of dolomite during weathering, with these ions being transported away by fluid movement, consistent with petrographic observations. The enrichment of Mo, Zn, and Mn in Stage II, coinciding with increased weathering intensity (

Figure 7d &

Figure 7e), is likely related to the precipitation of Mn(II) reacting with oxygen in neutral or near-neutral environment, facilitated by the increase in fluid pH.

5.3. Variation of REEs

REEs pattern of the dolomite exhibits a characteristic depletion of LREE (

Figure 8), which parallels the pattern observed in shallow pore waters [

33]. The concentration of REEs in carbonate rocks is significantly lower than that found in clastic rocks; therefore, even a minor incorporation of clastic REEs components can substantially influence the overall results [

30,

33]. Petrographic analysis reveals that the dolomite used in this study contains a significant amount of detrital material. As a result, the data obtained from LA-ICP-MS primarily reflect a comprehensive REEs distribution of the whole rock. This methodology captures the combined effects of both the original carbonate matrix and the incorporated detrital components, thereby providing a more integrated understanding of the REEs distribution patterns within the studied dolomite. REEs mapping presented in

Figure 9 further corroborates these findings, illustrating a general decline in REEs distribution with increasing weathering intensity, alongside localized increases at the edges, consistent with quantitative measurements (

Figure 9). This pattern underscores the dynamic interactions between REEs release, transport, and re-adsorption during the weathering process, with manganese mineral precipitation playing a pivotal role in the retention of REEs during Stage II. This trend can be attributed to the dissolution of REEs from dolomite into acidic fluids during the dissolution of dolomite in Stage I, resulting in their loss via fluid transport. Conversely, in Stage II, some REEs are re-adsorbed onto minerals, leading to their retention. As previously noted, the precipitation of Mn(II) occurs in Stage II, resulting in Mn enrichment; REEs are known to be readily adsorbed by manganese minerals [

22], thus contributing to the observed increase in REEs during this stage.

Ce is a redox-sensitive element predominantly existing as Ce

3+ and Ce

4+. In oxidizing aquatic environments, Ce

3+ is oxidized to Ce

4+, which is insoluble and tends to precipitate [

33]. The gradual increase in the Ce/Ce* ratio from Stage I to Stage II indicates an escalation in oxidation during the weathering process, with a greater quantity of Ce

4+ precipitating from the fluid, thereby enhancing the Ce/Ce* value. This trend of increasing oxidation associated with progressive weathering, from Stage I to Stage II, is consistent with the weathering characteristics of carbonate rocks observed in other regions [

11,

17,

18].

5.4. Variations in Oxygen Isotopes

The oxygen isotopic composition of carbonates is influenced by the fluid and temperature conditions present during diagenesis [

30,

49,

50]. In studies of stalagmites, oxygen isotope values are believed to correlate with those found in atmospheric precipitation, serving as indicators of monsoon rainfall and the effects of monsoon climate [

51,

52,

53]. During the formation of carbonate rocks, oxygen isotopes predominantly inherit the isotopic signal from atmospheric precipitation [

51,

52]. Notably, variations in the oxygen isotopes of atmospheric precipitation display a significant latitude effect, with higher latitudes resulting in greater isotopic fractionation and consequently lighter oxygen isotope values [

50,

54,

55,

56]. Zhijin Cave, located in Guizhou Province (26°46′ N, 105°53′ E), which has a latitude similar to the study area (28°05′ N, 109°02′ E), shows a range of oxygen isotope values in its modern stalagmite carbonates from -10 to -8‰ [

57,

58].

The dolomite strata examined in this study were formed during the Neoproterozoic Era, a period characterized by the presence of numerous glacial deposits in the Yangtze Block. This suggests that the latitude of the Yangtze Block during the Neoproterozoic was higher than it is today [

23]. Consequently, due to the latitude effect on atmospheric precipitation, carbonates formed during the Neoproterozoic are expected to exhibit lighter oxygen isotope values compared to modern carbonates. The range of oxygen isotope values in the pristine dolomite of this study, from -14.73 to -12.40‰, is indeed lighter than those of modern carbonates formed in Zhijin Cave (-10 to -8‰), aligning with the isotopic characteristics of carbonates formed during the Neoproterozoic. This suggests that the origin of the pristine dolomite may be comparable to that of stalagmites, influenced by the oxygen isotopic composition of atmospheric precipitation during the Neoproterozoic.

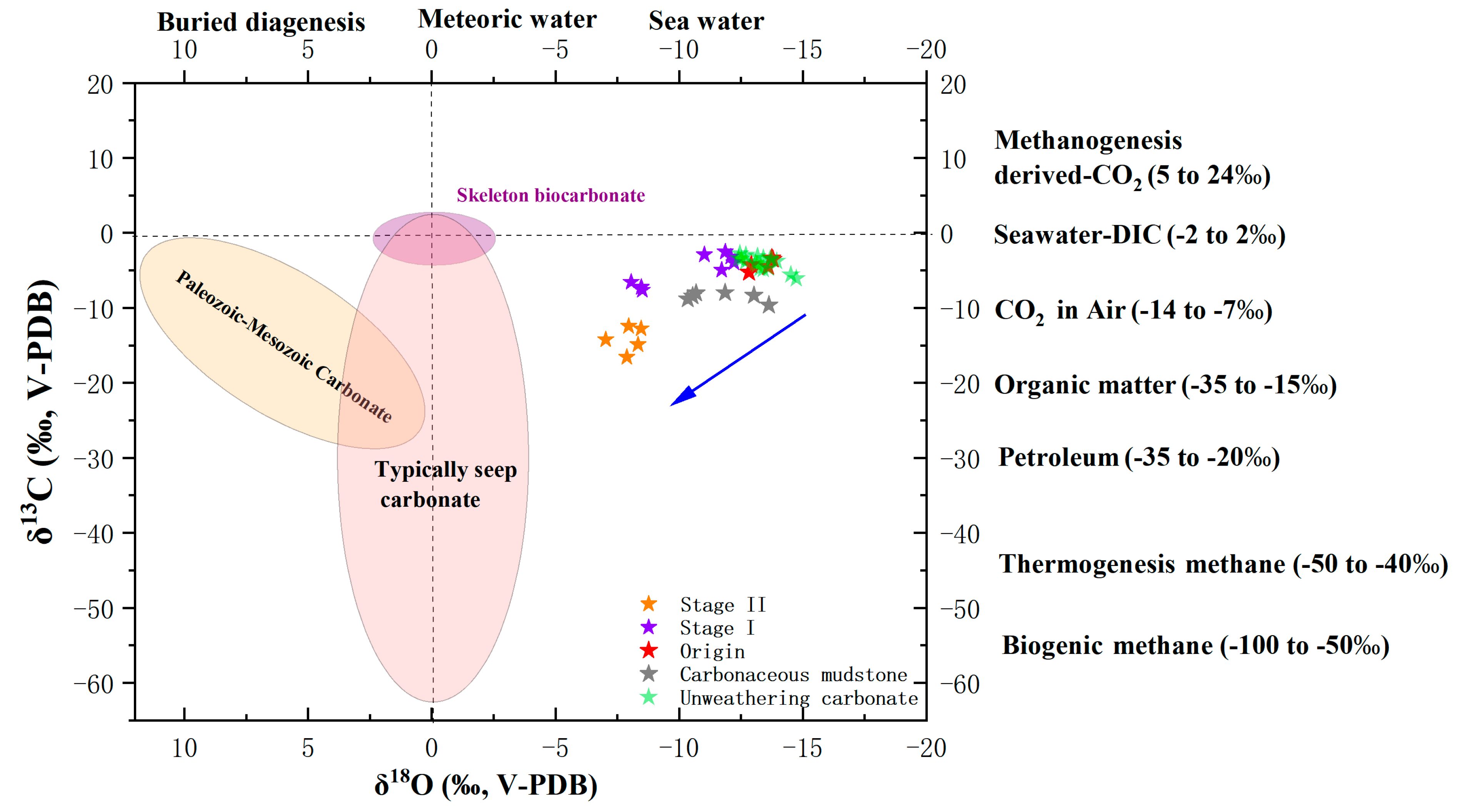

In Stage II, characterized by the increase intense weathering, the range of oxygen isotope values is -8.46 to -7.04‰, with an average of -7.83‰, which is consistent with the isotopic characteristics of modern carbonates from Zhijin Cave (

Figure 10 &

Figure 11).

These modern carbonates are in isotopic equilibrium with atmospheric precipitation, inheriting the isotopic signature of current atmospheric precipitation [

57,

58,

59]. Stage I displays oxygen isotope values that are intermediate between those of pristine dolomite and Stage II, indicating a gradual increase in weathering intensity from Stage I to Stage II, accompanied by a progressive alignment with the oxygen isotope values of Zhijin Cave. This observation suggests that variations in oxygen isotope values during weathering are influenced by the oxygen isotopic composition of atmospheric precipitation (

Figure 10).

5.5. Variations in Carbon isotopes

The carbon isotope composition of carbonates can provide insights into the composition and origin of the fluids involved in their formation [

57,

58,

60]. During the formation of carbonates, the carbon isotopic signature is closely linked to the isotopic composition of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in the fluids utilized, with minimal isotopic fractionation occurring during the precipitation of carbonates from DIC [

57,

60]. The formation of DIC through the reaction of CO

2 with water involves negligible carbon isotopic fractionation [

49,

61], meaning that the carbon isotopic signature of DIC is primarily determined by its source. There are three main sources of DIC: 1) dissolution from surrounding rocks; 2) the reaction between atmospheric CO

2 and water; and 3) the reaction between CO

2 produced by plant and root respiration and water [

49,

60,

61].

The dolomite examined in this study is embedded within the sandstone strata of the Liangjiehe Formation (

Figure 1). Given that the surrounding rocks are sandstone, the influence of DIC from these rocks on the dolomite lenses is considered minimal. Moreover, the dolomite lenses are encased by sandstone of the Liangjiehe Formation (

Figure 1), which suggests limited exposure to the atmosphere during their formation. This indicates that the DIC during dolomite formation was primarily derived from the reaction between CO

2 produced by plant and root respiration and water. The CO

2 generated by vegetation and root respiration in the overlying strata reacted with water to form DIC, which was subsequently transported by pore water to precipitate as dolomite lenses. The similarity in REEs partitioning patterns between the pristine dolomite and pore water further supports this hypothesis.

The influence of vegetation on DIC is regulated by two factors: vegetation cover and the ratio of C

3 to C

4 plants. Increased vegetation cover results in a higher proportion of organic matter in the soil, which enhances respiration and organic matter decomposition [

57,

58,

60]. This decomposition typically produces CO

2 with lighter δ

13C values, leading to lighter δ

13C values for DIC. Additionally, the C

3/C

4 plant ratio affects DIC values, as different plant types (C

3 and C

4) employ distinct photosynthetic pathways, resulting in the release of CO

2 with varying δ

13C values [

57,

60]. C

3 plants (e.g., trees and most shrubs) exhibit lower δ

13C values (-32 to -25‰), whereas C

4 plants (e.g., corn, sorghum, and prairie grasses) have higher δ

13C values (-14 to -10‰). C

3 plants thrive in moist and cool climates, while C

4 plants are adapted to hot and arid environments. An increase in the C

3/C

4 plant ratio would consequently lead to lighter δ

13C values for DIC [

57,

58].

During the Neoproterozoic Period, the Yangtze Block was characterized as a relatively cold region, exhibiting lower vegetation cover compared to contemporary conditions [

20,

21,

23]. This cold climate was not conducive to the growth of C

3 plants, resulting in a lower C

3/C

4 plant ratio than is observed today. Consequently, it is hypothesized that carbonates formed during the Neoproterozoic should display heavier carbon isotope values than those of modern carbonates. The carbon isotope composition of the pristine dolomite analyzed in this study supports this hypothesis. Specifically, the carbon isotope values of the pristine dolomite (-6.07 to -2.76‰) are heavier than those of stalagmites from Zhijin Cave (-11 to -6‰), aligning with the isotopic characteristics expected for carbonates formed during the Neoproterozoic Period.

In Stage II, carbon isotope values fluctuate between -16.56 and -12.43‰, with an average of -14.17‰ (

Figure 10 &

Figure 11). Atmospheric CO

2 typically has carbon isotope values ranging from -12 to -8‰. During rapid carbonate precipitation, carbon isotope values can be approximately 2‰ lighter than those of DIC [

62]. Therefore, the carbon isotope signature of Stage II carbonates is consistent with those expected from rapid precipitation influenced by atmospheric CO

2. This observation suggests that the carbonates formed during Stage II assimilated atmospheric CO

2 during weathering, thereby acquiring the carbon isotope signature characteristic of atmospheric CO

2. Stage I exhibits carbon isotope values that are intermediate between those of pristine dolomite and Stage II, indicating a gradual increase in weathering intensity from Stage I to Stage II, along with a progressive approach toward the carbon isotope values of atmospheric CO

2. This implies that variations in carbon isotope values during weathering are influenced by the carbon isotopic composition of atmospheric CO

2.

In summary, this study demonstrates that the oxygen and carbon isotope compositions of Neoproterozoic pristine dolomite lenses were governed by the oxygen isotope composition of atmospheric precipitation and the carbon isotope composition of DIC, which was influenced by the vegetation cover decrease during the Neoproterozoic Period. Due to the cold climate and high latitudes prevalent during this time, carbon isotopes in carbonates were heavier than those formed in modern times, while oxygen isotopes were lighter. During incipient weathering processes, the oxygen isotope composition of carbonates was influenced by contemporary atmospheric precipitation, whereas the carbon isotope composition was affected by modern atmospheric CO2.

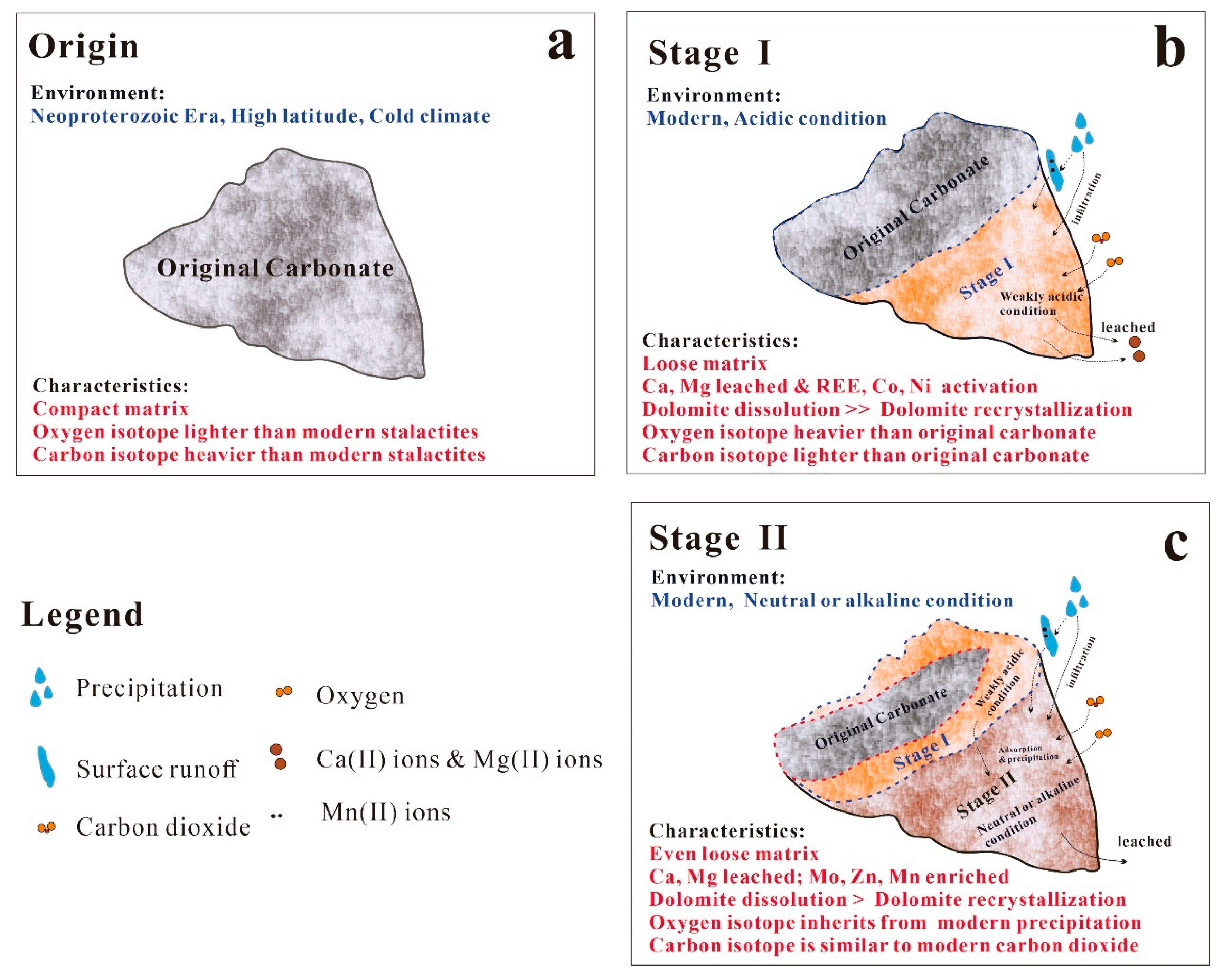

5.6. Implications for Understanding Carbonate Incipient Weathering Processes

This study delineates two distinct stages in the incipient weathering process of carbonates (

Figure 12).

In Stage I, carbonates interact with atmospheric CO2 and water to produce weakly acidic carbonic acid (H2CO3). This reaction initiates the leaching of Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ from the carbonates via interstitial water, resulting in dolomite dissolution and structural disintegration. During this stage, elements such as Ni and Co are solubilized in the weakly acidic interstitial water and subsequently removed, leading to their depletion.

Stage II is characterized by an increased production of HCO3⁻ as the reaction between carbonates, water, and CO2 continues. This process gradually elevates the pH and enhances the alkalinity of the interstitial water, which is evidenced by the absence of Ni and Co depletion in this stage. Concurrently, Mn(II) present in the interstitial water react with oxygen to form manganese oxides or hydroxides, which adsorb elements such as Mo, Zn, and REEs, leading to their enrichment during Stage II. Furthermore, the increasing alkalinity facilitates the recombination of HCO3⁻ with Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ ions, resulting in the recrystallization of carbonates. These newly formed carbonates inherit the oxygen isotopic composition of atmospheric precipitation and the carbon isotopic composition of atmospheric CO2, thereby defining the carbon-oxygen isotopic characteristics of Stage II.

6. Conclusion

In recent years, carbonate weathering has emerged as a significant global carbon sink, highlighting the critical need to investigate the mechanisms underlying the weathering of carbonate rocks. Research on these mechanisms primarily relies on weathered soil profiles; however, intense carbonate weathering often leads to the absence of the incipient weathering horizon within these profiles, which hinders a comprehensive understanding of incipient weathering processes and their regulatory mechanisms. In this study, we utilize surface-weathered carbonate rocks to elucidate the processes of incipient weathering in carbonates. The following conclusions were drawn:

1. The δ13C and δ18O isotope ratios of pristine dolomite, ranging from -5.26 to -3.35‰ and -13.79 to -12.83‰, respectively, suggest that dolomite formation occurred under high-latitude, cold climatic conditions during the Nanhua Period.

2. The study identifies two distinct stages of incipient weathering in dolomite. In Stage I, there is a significant decrease in REEs content, along with the leaching of Ni and Co. The fluctuating δ13C values (-7.61 to -2.52‰) and δ18O values (-12.22 to -8.06‰) indicate the presence of a weakly acidic microenvironment, during which dolomite is re-precipitated. In Stage II, there is an enrichment of Mn, Mo, and Zn, with δ13C values ranging from -16.56 to -12.43‰ and δ18O values from -8.46 to -7.03‰, reflecting a transition to a neutral environment where dolomite isotopes are influenced by atmospheric CO2 and atmospheric precipitation.

3. The mineralogical, geochemical, and carbon-oxygen isotopic characteristics of the surface-weathered carbonate rock provide a systematic documentation of the incipient weathering processes of carbonate rocks, positioning it as a potential proxy for studying these processes.

Author Contributions

X.Y. & X.Sun. designed the experiments and wrote this paper; Q.S. contributed to the sample preparation and analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed by the Lingnan Normal University Youth Doctor Project (ZL22037).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the author.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Zhou Qi for providing information on the sampling sites. Gratitude is extended to Yang LiMing and others for their assistance during sampling. Appreciation is expressed to Hu Wanwan for supplying information regarding paleogeography and paleoclimatology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could appear to have influenced the work reported.

References

- Jiao, K.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Yu, K.; Mcgrath, M.J.; Xu, W. Carbon cycle responses to climate change across China’s terrestrial ecosystem: Sensitivity and driving process. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Deng, Z.; Davis, S.J.; Giron, C.; Ciais, P. Monitoring global carbon emissions in 2021. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Deng, Z.; Davis, S.; Ciais, P. Monitoring global carbon emissions in 2022. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 205–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvia, M. Worldwide fluctuations in carbon emissions: Characterization and synchronization. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2024, 6, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Sayer, E.J.; Deng, M.; Li, P.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Yang, S.; Huang, J.; Luo, J.; Su, Y.; et al. The grassland carbon cycle: Mechanisms, responses to global changes, and potential contribution to carbon neutrality. Fundam. Res. 2023, 3, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayavenkataraman, S.; Iniyan, S.; Goic, R. A review of climate change, mitigation and adaptation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 878–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, J.N.; Govers, G.; Van Oost, K.; Bardgett, R.D. The impact of agricultural soil erosion on biogeochemical cycling. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Zhou, H.; Cao, Y.; Liao, H.; Lu, X.; Yu, Z.; Yuan, W.; Liu, Z.; Lei, Y.; Sitch, S.; et al. Large potential of strengthening the land carbon sink in China through anthropogenic interventions. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 2622–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y. Impact of land use change on regional carbon sink capacity: Evidence from Sanmenxia, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnscheidt, C.W.; Rothman, D.H. Presence or absence of stabilizing Earth system feedbacks on different time scales. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Liu, Z.; Kaufmann, G. Sensitivity of the global carbonate weathering carbon-sink flux to climate and land-use changes. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; Liu, Z.; Groves, C. Large-scale CO2 removal by enhanced carbonate weathering from changes in land-use practices. Earth-Science Rev. 2022, 225, 103915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechuga-Crespo, J.L.; Sauvage, S.; Ruiz-Romera, E.; van Vliet, M.T.H.; Probst, J.L.; Fabre, C.; Sánchez-Pérez, J.M. Global carbon sequestration through continental chemical weathering in a climatic change context. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bufe, A.; Hovius, N.; Emberson, R.; Rugenstein, J.K.C.; Galy, A.; Hassenruck-Gudipati, H.J.; Chang, J.M. Co-variation of silicate, carbonate and sulfide weathering drives CO2 release with erosion. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, M.F.; Lavallee, J.M. Soil organic matter formation, persistence, and functioning: A synthesis of current understanding to inform its conservation and regeneration; 1st ed.; Elsevier Inc., 2022; Vol. 172; ISBN 9780323989534.

- Gaillardet, J.; Calmels, D.; Romero-mujalli, G.; Zakharova, E.; Hartmann, J. Global climate control on carbonate weathering intensity. Chem. Geol. 2018, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckford, H.O.; Chu, H.; Song, C.; Chang, C.; Ji, H. Geochemical characteristics and behaviour of elements during weathering and pedogenesis over karst area in Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau, southwestern China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, W.J.; Tipper, E.T. The efficacy of enhancing carbonate weathering for carbon dioxide sequestration. Front. Clim. 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, N.; Shi, X. Distribution of Nanhua-Sinian rifts and proto-type basin evolution in southwestern Tarim Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 1206–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Liu, X.; Yu, W.; Du, Y.; Du, Q. Redox conditions and manganese metallogenesis in the Cryogenian Nanhua Basin: Insight from the basal Datangpo Formation of South China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2019, 529, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Tan, Z.; Jia, W.; Chen, J.; Peng, P. Nitrogen isotopes and geochemistry of the basal Datangpo Formation: Contrasting redox conditions in the upper and lower water columns during the Cryogenian interglaciation period. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2024, 637, 112005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wu, C.; Hu, X.; Yang, B.; Zhang, X.; Du, Y.; Xu, K.; Yuan, L.; Ni, J.; Hu, D.; et al. A new metallogenic model for the giant manganese deposits in northeastern Guizhou, China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 149, 105070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Shi, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, S. Stratigraphy and paleogeography of the Ediacaran Doushantuo Formation (ca. 635-551Ma) in South China. Gondwana Res. 2011, 19, 831–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Sun, X.; Xu, H.; Konishi, H.; Lin, Z.; Xu, L.; Chen, T.; Hao, X.; Lu, H.; Mann, J.P. Formation of dolomite catalyzed by sulfate-driven anaerobic oxidation of methane: Mineralogical and geochemical evidence from the northern South China Sea. Am. Mineral. 2018, 103, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sun, X.; Li, D.; Lin, Z.; Chen, T.; Lin, H. Sediment Mineralogy and Geochemistry and Their Implications for the Accumulation of Organic Matter in Gashydrate Bearing Zone of Shenhu, South China Sea. Minerals 2023, 13, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. Marine sediment nitrogen isotopes and their implications for the nitrogen cycle in the sulfate-methane transition zone. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sun, X.; Li, D.; Lin, Z.; Lu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Elemental and isotopic response of different carbon components to anaerobic oxidation of methane: A case study of marine sediments in the Shenhu region, northern South China Sea. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2021, 206, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, X.; Lin, Z.; Sun, X.; Yang, Y.; Peckmann, J. Reducing microenvironments promote incorporation of magnesium ions into authigenic carbonate forming at methane seeps: Constraints for dolomite formation. Sedimentology 2021, 68, 2945–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Sun, X.; Peckmann, J.; Lu, Y.; Xu, L.; Strauss, H.; Zhou, H.; Gong, J.; Lu, H.; Teichert, B.M.A. How sulfate-driven anaerobic oxidation of methane affects the sulfur isotopic composition of pyrite: A SIMS study from the South China Sea. Chem. Geol. 2016, 440, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Filho, S.; Paula-Santos, G.M.; Dias-Brito, D. Carbonate REE + Y signatures from the restricted early marine phase of South Atlantic Ocean (late Aptian – Albian): The influence of early anoxic diagenesis on shale-normalized REE + Y patterns of ancient carbonate rocks. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2018, 500, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Sun, X.; Li, D.; Sa, R.; Lu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhan, R.; Pan, Y.; Xu, H. New insights into nanostructure and geochemistry of bioapatite in REE-rich deep-sea sediments: LA-ICP-MS, TEM, and Z-contrast imaging studies. Chem. Geol. 2019, 512, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayon, G.; Birot, D.; Ruffine, L.; Caprais, J.C.; Ponzevera, E.; Bollinger, C.; Donval, J.P.; Charlou, J.L.; Voisset, M.; Grimaud, S. Evidence for intense REE scavenging at cold seeps from the Niger Delta margin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 312, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaram, V. Rare earth elements: A review of applications, occurrence, exploration, analysis, recycling, and environmental impact. Geosci. Front. 2019, 10, 1285–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai X, Zhang S, Smith P, Li C, Xiong L, Du C, Xue Y, Li Z, Long M, Li M, Zhang X, Yang S, Luo Q, Shen X. 2024. Resolving controversies surrounding carbon sinks from carbonate weathering. Science China Earth Sciences, 67(9): 2705–2717.

- Ott, R.; Gallen, S.F.; Helman, D. Erosion and weathering in carbonate regions reveal climatic and tectonic drivers of carbonate landscape evolution. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2023, 11, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcé, R.; Obrador, B.; Morguí, J.A.; Lluís Riera, J.; López, P.; Armengol, J. Carbonate weathering as a driver of CO2 supersaturation in lakes. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nõges, P.; Cremona, F.; Laas, A.; Martma, T.; Rõõm, E.I.; Toming, K.; Viik, M.; Vilbaste, S.; Nõges, T. Role of a productive lake in carbon sequestration within a calcareous catchment. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 550, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.W.; Arvidson, R.S.; Lüttge, A. Calcium carbonate formation and dissolution. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 342–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, B.H.; Kaczmarek, S.E.; Rivers, J.M. Dolomite dissolution: An alternative diagenetic pathway for the formation of palygorskite clay. Sedimentology 2019, 66, 1803–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sheng, H.; Ross, R.D.; Han, J.; Wang, X.; Song, B.; Jin, S. Modifying redox properties and local bonding of Co3O4 by CeO2 enhances oxygen evolution catalysis in acid. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, R.E.; Koper, M.T.M. Nickel as Electrocatalyst for CO(2) Reduction: Effect of Temperature, Potential, Partial Pressure, and Electrolyte Composition. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 4432–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinklebe, J.; Shaheen, S.M. Geochemical distribution of Co, Cu, Ni, and Zn in soil profiles of Fluvisols, Luvisols, Gleysols, and Calcisols originating from Germany and Egypt. Geoderma 2017, 307, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Sun, X.; Strauss, H.; Eroglu, S.; Böttcher, M.E.; Lu, Y.; Liang, J.; Li, J.; Peckmann, J. Molybdenum isotope composition of seep carbonates – Constraints on sediment biogeochemistry in seepage environments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2021, 307, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helz, G.R.; Miller, C. V.; Charnock, J.M.; Mosselmans, J.F.W.; Pattrick, R.A.D.; Garner, C.D.; Vaughan, D.J. Mechanism of molybdenum removal from the sea and its concentration in black shales: EXAFS evidence. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1996, 60, 3631–3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smrzka, D.; Feng, D.; Himmler, T.; Zwicker, J.; Hu, Y.; Monien, P.; Tribovillard, N.; Chen, D. Trace elements in methane-seep carbonates : Potentials, limitations, and perspectives. Earth-Science Rev. 2020, 208, 103263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, F.; Liu, Y.; Shang, Y.; Lv, C.; Xu, L.; Pei, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, G.; Yan, C. Dual ions intercalation drives high-performance aqueous Zn-ion storage on birnessite-type manganese oxides cathode. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 49, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; He, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, F.; He, Z.; Zeng, T.; Lu, X.; Wang, L.; Song, S.; Ma, J. Electron transfer enhancing the Mn(II)/Mn(III) cycle in MnO/CN towards catalytic ozonation of atrazine via a synergistic effect between MnO and CN. Water Res. 2023, 230, 119574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Shobnam, N.; Sun, Y.; Löffler, F.E.; Im, J. The relative contributions of Mn(III) and Mn(IV) in manganese dioxide polymorphs to bisphenol A degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehlert, A.M.; Swart, P.K. Interpreting carbonate and organic carbon isotope covariance in the sedimentary record. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vystavna, Y.; Matiatos, I.; Wassenaar, L.I. Temperature and precipitation effects on the isotopic composition of global precipitation reveal long-term climate dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, S.I.; Nordt, L.; Atchley, S. Determining terrestrial paleotemperatures using the oxygen isotopic composition of pedogenic carbonate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2005, 237, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, X.; Tripati, A.; Feng, S.; Elliott, B.; Whicker, C.; Arnold, A.; Kelley, A.M. Factors controlling the oxygen isotopic composition of lacustrine authigenic carbonates in Western China: implications for paleoclimate reconstructions. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, J.; Kwiecien, O. Coeval primary and diagenetic carbonates in lacustrine sediments challenge palaeoclimate interpretations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.; Jiang, H.; Wan, B.; Ducea, M.N.; Gao, L.; Wu, F.Y. Latitude-dependent oxygen fugacity in arc magmas. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, L.; Tian, L.; Sha, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, P.; Liang, Q.; Zong, B.; Duan, P.; Cheng, H. Triple oxygen isotope compositions reveal transitions in the moisture source of West China Autumn Precipitation. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Wang, L.; Kaseke, K.F.; Bird, B.W. Stable isotope compositions (δ2H, δ18O and δ17O) of rainfall and snowfall in the central United States. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.S.; Liu, Z.Q.; Li, H.C.; Wan, N.J.; Shen, C.C.; Ku, T.L. Climate and environmental changes during the past millennium in central western Guizhou, China as recorded by Stalagmite ZJD-21. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2011, 40, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Yan, J.; Chen, F. New insights on Chinese cave δ18O records and their paleoclimatic significance. Earth-Science Rev. 2020, 207, 103216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettger, J.D.; Kubicki, J.D. Equilibrium and kinetic isotopic fractionation in the CO2 hydration and hydroxylation reactions: Analysis of the role of hydrogen-bonding via quantum mechanical calculations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2021, 292, 37–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolivet, M.; Boulvais, P. Global significance of oxygen and carbon isotope compositions of pedogenic carbonates since the Cretaceous. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 101132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, V.J.; Loftus, E.; Jeffrey, A.; Ramsey, C.B. Atmospheric CO2 effect on stable carbon isotope composition of terrestrial fossil archives. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Deng, W.; Wei, G. Experimental Constraints on Clumped Isotope Fractionation During BaCO3 Precipitation. Geochemistry, Geophys. Geosystems 2022, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Bao, H.; Jiang, G.; Crockford, P.; Feng, D.; Xiao, S.; Kaufman, A.J.; Wang, J. A transient peak in marine sulfate after the 635-Ma snowball Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022, 119, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Jin, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, N. The effects of diagenetic processes and fluid migration on rare earth element and organic matter distribution in seep-related sediments: A case study from the South China Sea. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2020, 191, 104233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesson, K.H.; Lyons, W.B.; Bird, D.A. Rare earth element concentrations and speciation in alkaline lakes from the western U.S.A. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1994, 21, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Location information of sampling sites. a. The study area, located in the Datangpo region of Songtao County, Guizhou Province, corresponds to the paleogeographic junction of the Yangtze Block within the Nanhua Basin and the Jiangnan Orogenic Belt (modified after Peng et al., 2022). b. The sampling sites for this study were positioned within the strata which was formed during the Nanhua Period (modified after Zhou et al., 2022). c. The Nanhuan (Cryogenian) System stratigraphic sections involved in this study include Liangjiehe, Tiesiao, and Datangpo Group (modified after Zhou et al., 2022). d. Datangpo Group carbonaceous mudstone outcrop. e. The surface-weathered carbonate lens at the top of the Liangjiehe Group. f. The surface-weathered carbonate lens at the bottom of the Liangjiehe Group.

Figure 1.

Location information of sampling sites. a. The study area, located in the Datangpo region of Songtao County, Guizhou Province, corresponds to the paleogeographic junction of the Yangtze Block within the Nanhua Basin and the Jiangnan Orogenic Belt (modified after Peng et al., 2022). b. The sampling sites for this study were positioned within the strata which was formed during the Nanhua Period (modified after Zhou et al., 2022). c. The Nanhuan (Cryogenian) System stratigraphic sections involved in this study include Liangjiehe, Tiesiao, and Datangpo Group (modified after Zhou et al., 2022). d. Datangpo Group carbonaceous mudstone outcrop. e. The surface-weathered carbonate lens at the top of the Liangjiehe Group. f. The surface-weathered carbonate lens at the bottom of the Liangjiehe Group.

Figure 2.

Samples collected from study region. a. The surface-weathered carbonate rock shows three distinctly different colored zones, representing the original carbonate, the Stage I of incipient weathering, and the Stage II of incipient weathering. b. The weathered carbonate surface exhibits fine laminated structures. c&d. Carbonate rocks with a yellow-brown weathering crust. e.The sandstone from Liangjiehe Group. f.The sandstone from Tiesiao Group. g. The carbonaceous mudstone from Datangpo Group. h.The interior of the carbonate lens that has not been affected by weathering.

Figure 2.

Samples collected from study region. a. The surface-weathered carbonate rock shows three distinctly different colored zones, representing the original carbonate, the Stage I of incipient weathering, and the Stage II of incipient weathering. b. The weathered carbonate surface exhibits fine laminated structures. c&d. Carbonate rocks with a yellow-brown weathering crust. e.The sandstone from Liangjiehe Group. f.The sandstone from Tiesiao Group. g. The carbonaceous mudstone from Datangpo Group. h.The interior of the carbonate lens that has not been affected by weathering.

Figure 3.

Carbonate samples slice. a.The carbonaceous mudstone from Datangpo Group, with interspersed pyrite. b. In the surface-weathered cross carbonate section, three distinct color zones are clearly visible. c.Pristine carbonates appear blueish-gray.

Figure 3.

Carbonate samples slice. a.The carbonaceous mudstone from Datangpo Group, with interspersed pyrite. b. In the surface-weathered cross carbonate section, three distinct color zones are clearly visible. c.Pristine carbonates appear blueish-gray.

Figure 4.

Comparative analysis of mineralogy with varying degrees of weathering. a. SEM image of pristine dolomite, revealing a dense matrix and quartz grains. b. SEM image of Stage I dolomite, showing a more porous matrix and fractures. c. SEM image of Stage II dolomite, displaying an even more porous and cavernous matrix, with fillings in fractures resembling the matrix. Fillings in fractures are identified as calcite through energy-dispersive spectroscopy. d.Microscope image of pristine dolomite, displaying a relatively dense, bluish-gray matrix with quartz grains visible. e. Microscope image of Stage I dolomite, distinctly showing a yellowish-brown matrix with a decrease in bluish-gray dolomite minerals. f. Microscope image of Stage II dolomite, observing a significant increase in quartz grains, leading to a cloudier matrix, alongside residual milky-white dolomite.

Figure 4.

Comparative analysis of mineralogy with varying degrees of weathering. a. SEM image of pristine dolomite, revealing a dense matrix and quartz grains. b. SEM image of Stage I dolomite, showing a more porous matrix and fractures. c. SEM image of Stage II dolomite, displaying an even more porous and cavernous matrix, with fillings in fractures resembling the matrix. Fillings in fractures are identified as calcite through energy-dispersive spectroscopy. d.Microscope image of pristine dolomite, displaying a relatively dense, bluish-gray matrix with quartz grains visible. e. Microscope image of Stage I dolomite, distinctly showing a yellowish-brown matrix with a decrease in bluish-gray dolomite minerals. f. Microscope image of Stage II dolomite, observing a significant increase in quartz grains, leading to a cloudier matrix, alongside residual milky-white dolomite.

Figure 5.

The XRD in different incipient weathering stages. a.The whole-rocks XRD data, when compared with Cu-target standard minerals, identified the main minerals in the dolomite as dolomite, quartz, and feldspar. The peak intensities of quartz and feldspar increase from pristine dolomite to Stage II dolomite. b.The in-situ XRD data of carbonate matrix grains in different incipient weathering stages, when compared with Mo-target standard minerals, no diagenetic transformation between carbonate species occurred. Quartz and feldspar likely originated from contamination by quartz and feldspar minerals from the Liangjiehe Formation during the formation of the dolomite.

Figure 5.

The XRD in different incipient weathering stages. a.The whole-rocks XRD data, when compared with Cu-target standard minerals, identified the main minerals in the dolomite as dolomite, quartz, and feldspar. The peak intensities of quartz and feldspar increase from pristine dolomite to Stage II dolomite. b.The in-situ XRD data of carbonate matrix grains in different incipient weathering stages, when compared with Mo-target standard minerals, no diagenetic transformation between carbonate species occurred. Quartz and feldspar likely originated from contamination by quartz and feldspar minerals from the Liangjiehe Formation during the formation of the dolomite.

Figure 6.

Element migration during incipient weathering processes. a. In Stage I, significant depletion of Mg and Ca elements is observed, accompanied by notable depletion of Ni and Co elements. Conversely, there is significant enrichment of Mo. b. In Stage II, Mg and Ca elements continue to be significantly depleted, while Mn, Zn, and Mo elements exhibit notable enrichment.

Figure 6.

Element migration during incipient weathering processes. a. In Stage I, significant depletion of Mg and Ca elements is observed, accompanied by notable depletion of Ni and Co elements. Conversely, there is significant enrichment of Mo. b. In Stage II, Mg and Ca elements continue to be significantly depleted, while Mn, Zn, and Mo elements exhibit notable enrichment.

Figure 7.

Variation of element concentrations in carbonate with different stages of incipient weathering. a. Variation of Ca content during incipient weathering processes. The Ca content gradually decreases with increasing weathering intensity. b. Variation of Mg content during incipient weathering processes. The Mg content also gradually decreases in incipient weathering processes. c. Variation of Mg/Ca ratio during weathering processes. The further dissolution of carbonates formed through recrystallization results in a greater loss of Ca than Mg, leading to an increase in the Mg/Ca ratio in incipient weathering processes. d.Variation of Mo content. The Mo content gradually enriches in incipient weathering processes. e. Variation of Mn content during weathering processes. There is a gradual enrichment of Mn with increasing weathering intensity. f. Variation of Ce/Ce* ratio during weathering processes. The Ce/Ce* ratio progressively increases with the degree of weathering.

Figure 7.

Variation of element concentrations in carbonate with different stages of incipient weathering. a. Variation of Ca content during incipient weathering processes. The Ca content gradually decreases with increasing weathering intensity. b. Variation of Mg content during incipient weathering processes. The Mg content also gradually decreases in incipient weathering processes. c. Variation of Mg/Ca ratio during weathering processes. The further dissolution of carbonates formed through recrystallization results in a greater loss of Ca than Mg, leading to an increase in the Mg/Ca ratio in incipient weathering processes. d.Variation of Mo content. The Mo content gradually enriches in incipient weathering processes. e. Variation of Mn content during weathering processes. There is a gradual enrichment of Mn with increasing weathering intensity. f. Variation of Ce/Ce* ratio during weathering processes. The Ce/Ce* ratio progressively increases with the degree of weathering.

Figure 8.

REEs patterns in carbonate with different stages of incipient weathering. a. REEs pattern for pristine dolomite. b. REEs pattern for Stage I dolomite. c. REEs pattern for Stage II dolomite. d. REEs patterns of biogenic apatite and iron-manganese micronodules [

30,

33]. e. REEs patterns of deep-sea seawater and marine biogenic skeletons [

31]. f. REEs patterns of shallow and deep pore waters [

33,

64,

65].

Figure 8.

REEs patterns in carbonate with different stages of incipient weathering. a. REEs pattern for pristine dolomite. b. REEs pattern for Stage I dolomite. c. REEs pattern for Stage II dolomite. d. REEs patterns of biogenic apatite and iron-manganese micronodules [

30,

33]. e. REEs patterns of deep-sea seawater and marine biogenic skeletons [

31]. f. REEs patterns of shallow and deep pore waters [

33,

64,

65].

Figure 9.

Distribution of REEs in a typical surface-weathered carbonate slice. a. Distribution of total REEs content in different stages of incipient weathering. b. Distribution of LREE content in different stages of incipient weathering . c. Distribution of HREE content in different stages of incipient weathering.

Figure 9.

Distribution of REEs in a typical surface-weathered carbonate slice. a. Distribution of total REEs content in different stages of incipient weathering. b. Distribution of LREE content in different stages of incipient weathering . c. Distribution of HREE content in different stages of incipient weathering.

Figure 10.

Variations in carbon and oxygen isotopes a typical surface-weathered carbonate slice. a. In situ carbon and oxygen isotope analysis of surface-weathered carbonate. b-b’. The variation of carbon and oxygen isotopes from the interior to the exterior (Transect A). c-c’. The variation of carbon and oxygen isotopes in pristine dolomite zone(Transect B). d-d’. Distribution of carbon and oxygen isotopes in surface-weathered carbonate. e-e’. Carbon isotope values become progressively lighter with ongoing weathering, while oxygen isotopes become progressively heavier .

Figure 10.

Variations in carbon and oxygen isotopes a typical surface-weathered carbonate slice. a. In situ carbon and oxygen isotope analysis of surface-weathered carbonate. b-b’. The variation of carbon and oxygen isotopes from the interior to the exterior (Transect A). c-c’. The variation of carbon and oxygen isotopes in pristine dolomite zone(Transect B). d-d’. Distribution of carbon and oxygen isotopes in surface-weathered carbonate. e-e’. Carbon isotope values become progressively lighter with ongoing weathering, while oxygen isotopes become progressively heavier .

Figure 11.

Carbon and oxygen isotope plot. Pristine dolomite exhibits similar carbon and oxygen isotope characteristics to the carbonaceous mudstone; The carbon and oxygen isotopes of Stage I dolomite fall between pristine dolomite and Stage II dolomite; Stage II dolomite displays lighter carbon isotopes and heavier oxygen isotopes compared to pristine dolomite.

Figure 11.

Carbon and oxygen isotope plot. Pristine dolomite exhibits similar carbon and oxygen isotope characteristics to the carbonaceous mudstone; The carbon and oxygen isotopes of Stage I dolomite fall between pristine dolomite and Stage II dolomite; Stage II dolomite displays lighter carbon isotopes and heavier oxygen isotopes compared to pristine dolomite.

Figure 12.

Schematic diagram of the carbonate incipient weathered process for Datangpo surface-weathered carbonate. a. Primary carbonate rocks formed during the Neoproterozoic Era in high latitudes and cold climates, with tightly compacted carbonate bases, oxygen isotopes lighter than those of modern stalactites, and carbon isotopes heavier than those of modern stalactites. b. During the Stage I of incipient weathering, CO2 and water react with carbonates to form a weakly acidic micro-environment, resulting in the leaching of Mg, Ca, REEs, Co, and Ni ions, the loosening of the substrate, the enrichment of oxygen isotopes, and the depletion of carbon isotopes. c. During the Stage II of incipient weathering, HCO3- accumulate and form a circumneutral micro-environment, Mg and Ca continue to leach, while Mo, Zn, and Mn are weakly enriched. Carbon isotopes are similar to.

Figure 12.

Schematic diagram of the carbonate incipient weathered process for Datangpo surface-weathered carbonate. a. Primary carbonate rocks formed during the Neoproterozoic Era in high latitudes and cold climates, with tightly compacted carbonate bases, oxygen isotopes lighter than those of modern stalactites, and carbon isotopes heavier than those of modern stalactites. b. During the Stage I of incipient weathering, CO2 and water react with carbonates to form a weakly acidic micro-environment, resulting in the leaching of Mg, Ca, REEs, Co, and Ni ions, the loosening of the substrate, the enrichment of oxygen isotopes, and the depletion of carbon isotopes. c. During the Stage II of incipient weathering, HCO3- accumulate and form a circumneutral micro-environment, Mg and Ca continue to leach, while Mo, Zn, and Mn are weakly enriched. Carbon isotopes are similar to.

Table 1.

Elements concentration of surface-weathered carbonate.

Table 1.

Elements concentration of surface-weathered carbonate.

| Scheme |

Mg |

Al |

Ca |

Ti |

Mn |

Fe |

Cr |

Co |

Ni |

Cu |

Zn |

Mo |

Th |

U |

Mn/Fe |

Ni/Co |

U/Th |

| Unit |

‰ |

‰ |

‰ |

‰ |

‰ |

‰ |

ppm |

ppm |

ppm |

ppm |

ppm |

ppm |

ppm |

ppm |

|

|

|

| P-1 |

17.77 |

45.76 |

37.79 |

1.66 |

0.78 |

8.51 |

24.78 |

1.61 |

2.56 |

1.25 |

34.94 |

0.00 |

2.05 |

0.51 |

0.09 |

1.59 |

0.25 |

| P-2 |

52.59 |

27.58 |

157.64 |

2.01 |

2.48 |

25.56 |

14.75 |

1.56 |

2.96 |

1.26 |

57.71 |

0.16 |

8.81 |

2.29 |

0.10 |

1.89 |

0.26 |

| P-3 |

92.45 |

9.44 |

212.06 |

0.91 |

4.1 |

33.40 |

9.27 |

2.38 |

3.22 |

1.18 |

77.48 |

0.21 |

2.44 |

0.44 |

0.12 |

1.35 |

0.18 |

| P-4 |

57.51 |

24.09 |

130.39 |

1.76 |

2.73 |

40.88 |

16.63 |

407.35 |

314.18 |

68.18 |

88.00 |

0.16 |

4.70 |

1.00 |

0.07 |

0.77 |

0.21 |

| P-5 |

88.57 |

13.25 |

196.03 |

0.40 |

3.65 |

33.10 |

10.21 |

1.70 |

3.21 |

1.63 |

102.24 |

0.21 |

1.80 |

0.25 |

0.11 |

1.89 |

0.14 |

| S1-1 |

89.06 |

9.9 |

179.80 |

0.51 |

5.36 |

54.65 |

23.52 |

21.48 |

10.75 |

7.76 |

249.17 |

0.63 |

2.12 |

0.96 |

0.10 |

0.50 |

0.45 |

| S1-2 |

34.48 |

16.14 |

68.05 |

0.85 |

2.35 |

27.91 |

14.98 |

2.37 |

5.01 |

13.01 |

101.97 |

0.30 |

2.47 |

0.75 |

0.08 |

2.12 |

0.31 |

| S1-3 |

5.78 |

41.96 |

5.67 |

1.94 |

0.56 |

12.60 |

16.61 |

1.02 |

3.77 |

1.61 |

31.13 |

-0.01 |

4.07 |

0.90 |

0.04 |

3.68 |

0.22 |

| S1-4 |

5.44 |

108.74 |

11.59 |

2.73 |

0.84 |

9.10 |

61.11 |

1.18 |

3.70 |

1.71 |

57.14 |

0.12 |

1.14 |

0.29 |

0.09 |

3.13 |

0.25 |

| S1-5 |

6.74 |

41.5 |

23.80 |

1.12 |

1.66 |

18.69 |

15.92 |

2.39 |

6.45 |

2.65 |

75.03 |

0.09 |

2.69 |

0.53 |

0.09 |

2.70 |

0.20 |

| S1-6 |

1.89 |

12.54 |

0.80 |

0.56 |

2.79 |

22.80 |

10.57 |

2.97 |

7.36 |

5.19 |

62.84 |

0.21 |

2.08 |

0.66 |

0.12 |

2.48 |

0.32 |

| S1-7 |

5.32 |

20.14 |

41.11 |

1.47 |

1.61 |

23.09 |

13.13 |

2.72 |

8.64 |

15.31 |

150.29 |

0.39 |

2.85 |

0.70 |

0.07 |

3.17 |

0.25 |

| S1-8 |

6.65 |

46.18 |

15.06 |

1.94 |

0.58 |

11.73 |

33.33 |

2.72 |

6.40 |

2.46 |

79.07 |

0.20 |

3.29 |

0.95 |

0.05 |

2.35 |

0.29 |

| S1-9 |

3.04 |

17 |

23.39 |

0.31 |

1.26 |

12.52 |

4.88 |

1.12 |

3.65 |

2.81 |

44.89 |

0.17 |

1.04 |

0.19 |

0.10 |

3.26 |

0.18 |

| S1-10 |

2.32 |

32.36 |

0.40 |

0.93 |

2.75 |

17.04 |

16.74 |

7.41 |

10.11 |

20.91 |

93.10 |

0.21 |

1.87 |

0.64 |

0.16 |

1.36 |

0.34 |

| S2-1 |

0.76 |

11.53 |

0.09 |

0.59 |

0.3 |

3.33 |

5.42 |

0.44 |

0.88 |

0.85 |

21.90 |

0.03 |

0.95 |

0.33 |

0.09 |

2.01 |

0.35 |

| S2-2 |

2.96 |

33.06 |

1.36 |

1.61 |

3.78 |

26.55 |

22.90 |

5.17 |

11.79 |

11.98 |

199.42 |

0.38 |

1.87 |

0.86 |

0.14 |

2.28 |

0.46 |

| S2-3 |

2.91 |

8.96 |

2.17 |

0.48 |

11.51 |

51.73 |

52.54 |

5.70 |

15.82 |

16.49 |

256.20 |

1.25 |

1.28 |

0.41 |

0.22 |

2.78 |

0.32 |

| S2-4 |

2.25 |

31.26 |

0.48 |

1.25 |

1.39 |

19.47 |

31.65 |

3.08 |

8.71 |

7.50 |

172.93 |

0.45 |

1.70 |

0.73 |

0.07 |

2.83 |

0.43 |

| S2-5 |

3.69 |

32.6 |

0.89 |

1.35 |

2.76 |

37.79 |

31.98 |

3.65 |

10.70 |

10.55 |

254.11 |

0.80 |

2.84 |

1.72 |

0.07 |

2.93 |

0.61 |

| S2-6 |

1.49 |

20.79 |

0.45 |

1.04 |

2.32 |

17.69 |

9.52 |

1.09 |

3.53 |

4.49 |

103.79 |

0.28 |

2.33 |

0.62 |

0.13 |

3.24 |

0.26 |

Table 2.

REEs concentration of weathered carbonate .

Table 2.

REEs concentration of weathered carbonate .

| Sample No.* |

La |

Ce |

Pr |

Nd |

Sm |

Eu |

Gd |

Tb |

Dy |

Ho |

Er |

Tm |

Yb |

Lu |

Ce/Ce* |

Eu/Eu* |

| P-1 |

0.51 |

1.29 |

0.18 |

0.89 |

0.51 |

0.30 |

0.99 |

0.20 |

1.49 |

0.31 |

0.89 |