3. Results

This results section is divided into four subsections, which are mapped with the four possibilities arising from the two binary variables (namely, two alkali seed types and two oxidizer types). For each case of these four conditions, we present first the variation of the plasma electric conductivity () after thermal equilibrium, as a function of the total pre-ionization absolute pressure () with the mole fraction of the neutral alkali seed metal () being a parameter. Thus, the variation of () is visualized versus () as five curves (one curve per ), and this visualization is presented four times (for two seed types and two oxidizer types). Similarly, the estimated ideal volumetric power density () is visualized as a function of () four times in the four coming subsections, at five values of () in each () plot.

To aid in interpreting the electric conductivity, it is voluntarily expressed as a multiple of the typical seawater electric conductivity, which is assigned here a value of 5 S/m [

233,

234,

235]. The secondary (right) vertical axis in the electric conductivity (

) plots is utilized for this purpose, while the primary (left) vertical axis is utilized for expressing the absolute (unscaled) value of (

), expressed in the SI unit of S/m.

Regarding the pre-ionization speed of sound (), and thus the plasma speed (); because () is independent of the total pressure, it does not need to be visualized as a dependent variable of (). Instead, we only tabulate its values for the five values of () at the beginning of each of the four coming subsections, along with other thermochemical properties that are also independent of the total absolute pressure (such as the pre-ionization mixture’s molecular weight).

In addition to the visualized curves, we also list the numerical values for the variations in () and (). This is useful for the sake of precision, as well as for subsequent utilization of these values by interested readers in external quantitative analysis or comparisons conducted by themselves.

For effective contrast and use of the plots, the ranges of the axes are retained the same regardless of the actual range of the data being visualized. This allows for quick identification of the relative size of the data visualized in different figures, which correspond to different operational cases or the H2MHD channel.

For effective identification of the individual influence of the seed type and the oxidizer type, we intentionally order the four coming subsections such that in the transition from one subsection to the next, only one change is made. This change is either altering the seed type or altering the oxidizer type (but not altering both of them at once; which makes it difficult to separate the influence of each alteration from the other).

3.1. Cesium Seed and Air Oxidizer

The first set of results corresponds to the condition of using cesium vapor as the ionizable gas, and using air as the oxidizer for the hydrogen combustion.

In

Table 6, we provide our computed thermochemical characteristics for the seeded gas mixture before ionization, according to the mathematical model presented in the previous section.

It is noticed that as the mole fraction of cesium increases, the mixture’s gas constant () decreases (because the mixture’s molecular weight increases). This is justified by the heavier molecular weight of cesium (Cs) compared to either water vapor (H2O) or molecular nitrogen (N2). One mole of cesium (Cs) is 4.744 times heavier than one mole of molecular nitrogen (N2), and 7.377 times heavier than one mole of water (H2O). One of the implications of the decline in the mixture’s gas constant () is a decline in the speed of sound (), and thus the plasma’s bulk speed (given that it is always twice the speed of sound in the current study). However, these influences of the additive cesium remain marginal up to a mole fraction of 1%. The remarkable changes at the large mole fraction of 16% are quite virtual, because practically it is not expected to have such a big portion of the seed.

Despite the seed content, the mole fraction ratio () is always 1.881, as implied by the stoichiometry reaction in Equation (13), which stipulates that this ratio should be in the cases of air-hydrogen combustion.

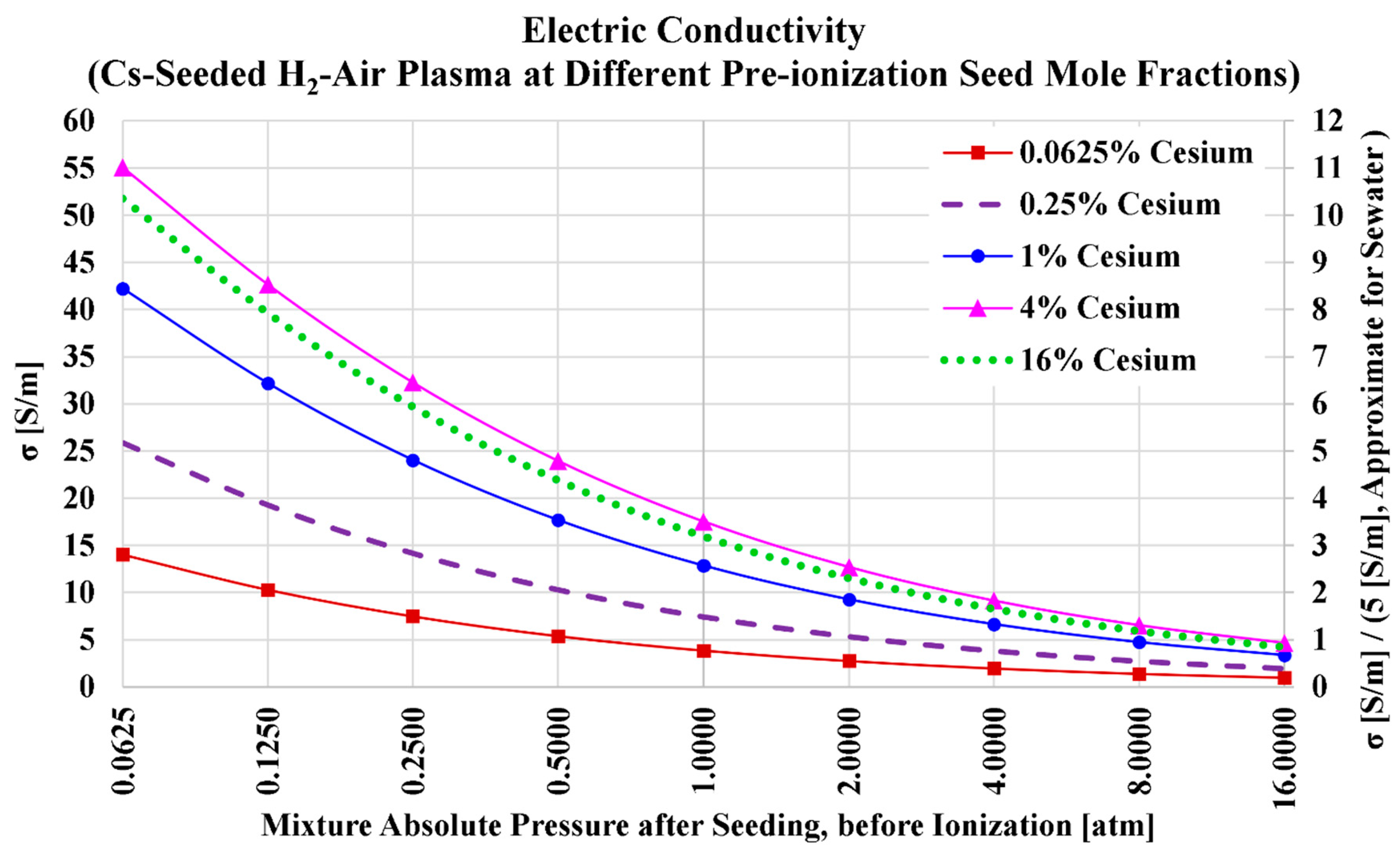

Figure 2 shows how the electric conductivity of the hydrogen plasma drops monotonically and nonlinearly as the total pre-ionization absolute pressure increases. This trend is identical for the five seed levels of cesium vapor. This drop in the electric conductivity can be explained by the larger number density of neutral heavy particles (atoms and molecules) in the plasma at higher pressures, which retards the directional movement of the liberated electrons from the ionized cesium atoms due to more frequent collisions with these neutral particles [

236,

237,

238].

Unlike the effect of the pressure, the effect of the cesium additive is non-monotonic. Starting from a small level of (Cs), adding more (Cs) initially improves the electric conductivity. This boost slows down and reaches a peak near a cesium mole fraction of

, and then the electric conductivity starts to drop as more cesium vapor is added in place of water vapor and nitrogen. This peaking behavior of the electric conductivity (

) can be attributed to the presence of two factors that impact the electric conductivity due to the free electrons produced by the ionization of a fraction of the cesium atoms. The first factor is the large number density of electrons, due to more cesium atoms; this improves the electric conductivity as more cesium is added. The other factor is the electron-ion interaction (attraction) and electron-electron interaction (repulsion) due to their electric charges. As the number of electrons (and thus the number of cesium ions) increases beyond an appreciable level, the attenuating effect on the electric conductivity caused by these interactions (Coulomb scattering) [

239,

240,

241] overpowers the accentuating effect on the electric conductivity caused by the electrons’ number density; and thus the electric conductivity declines after reaching a peak value. This explains why the electric conductivity with a higher cesium mole fraction of 16% is less than the electric conductivity with a lower cesium mole fraction of 4%. From the shown figure, it may be inferred qualitatively that a pre-ionization cesium mole fraction of 1% or 2% is preferred, because the weak increase in the electric conductivity beyond these levels does not seem to justify such additions of cesium content.

Table 7 lists the numerical values of the plasma electric conductivity as visualized in the previous figure. We also add in the table the electric conductivity values at a pre-ionization cesium mole fraction of

, which approximately corresponds to the maximized electric conductivity for this case (air-hydrogen combustion plasma with cesium seed).

Considering the five selected seed levels (0.0625%, 0.25%, 1%, 4%, and 16%), the highest obtained electric conductivity is (at and ), and this is about 11 times the electric conductivity of seawater. At the higher (and the same total pressure of 0.0625 atm), the electric conductivity is slightly lower, with a value of 51.7766 S/m; while at the lower (and the same total pressure of 0.0625 atm), the electric conductivity is mildly lower, with a value of 42.2099 S/m. If we take a total pressure of 1 atm (atmospheric MHD channel) as a reference, one can see that the electric conductivity can exceed 10 S/m (twice the conductivity of seawater) with only 1% cesium level.

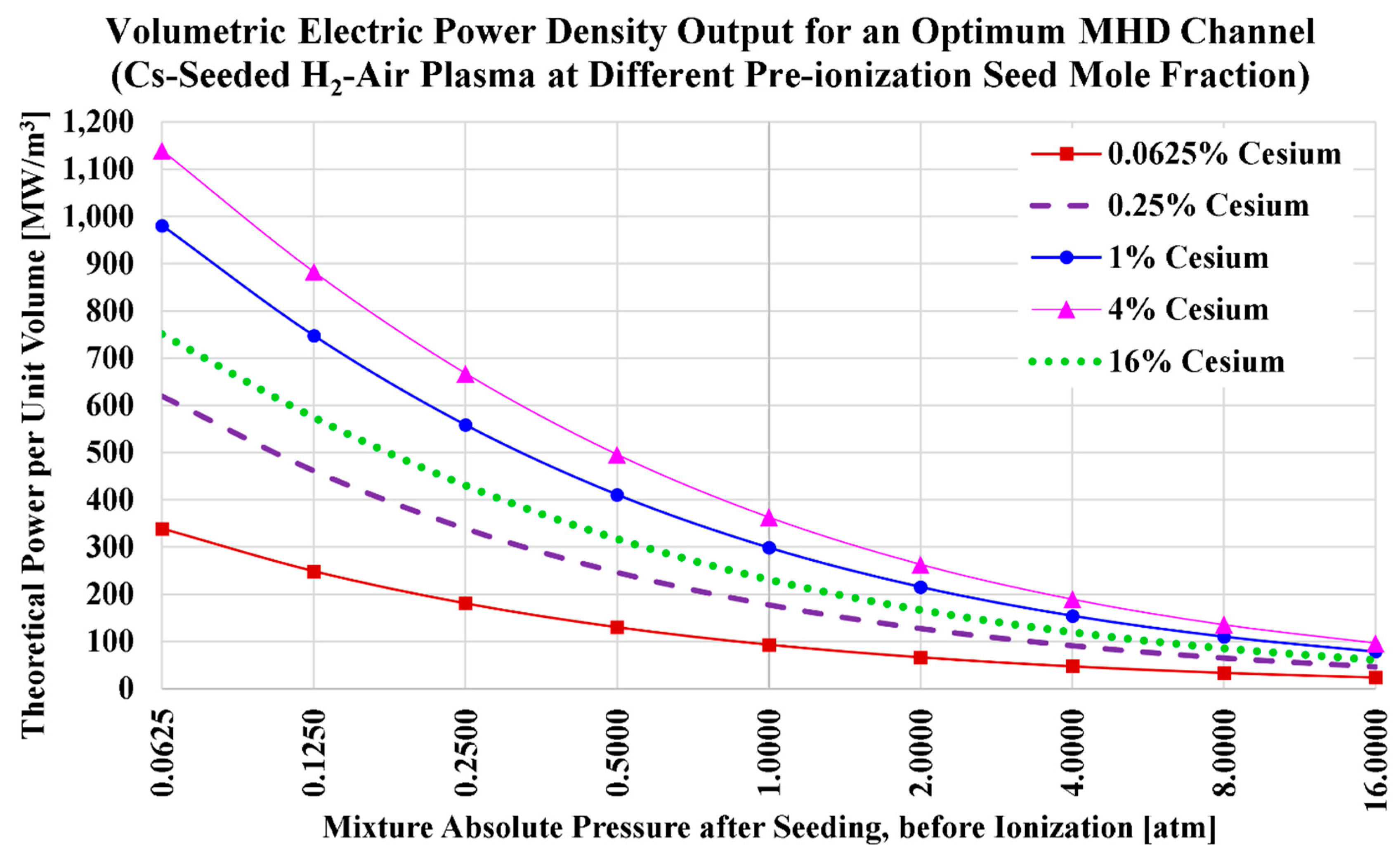

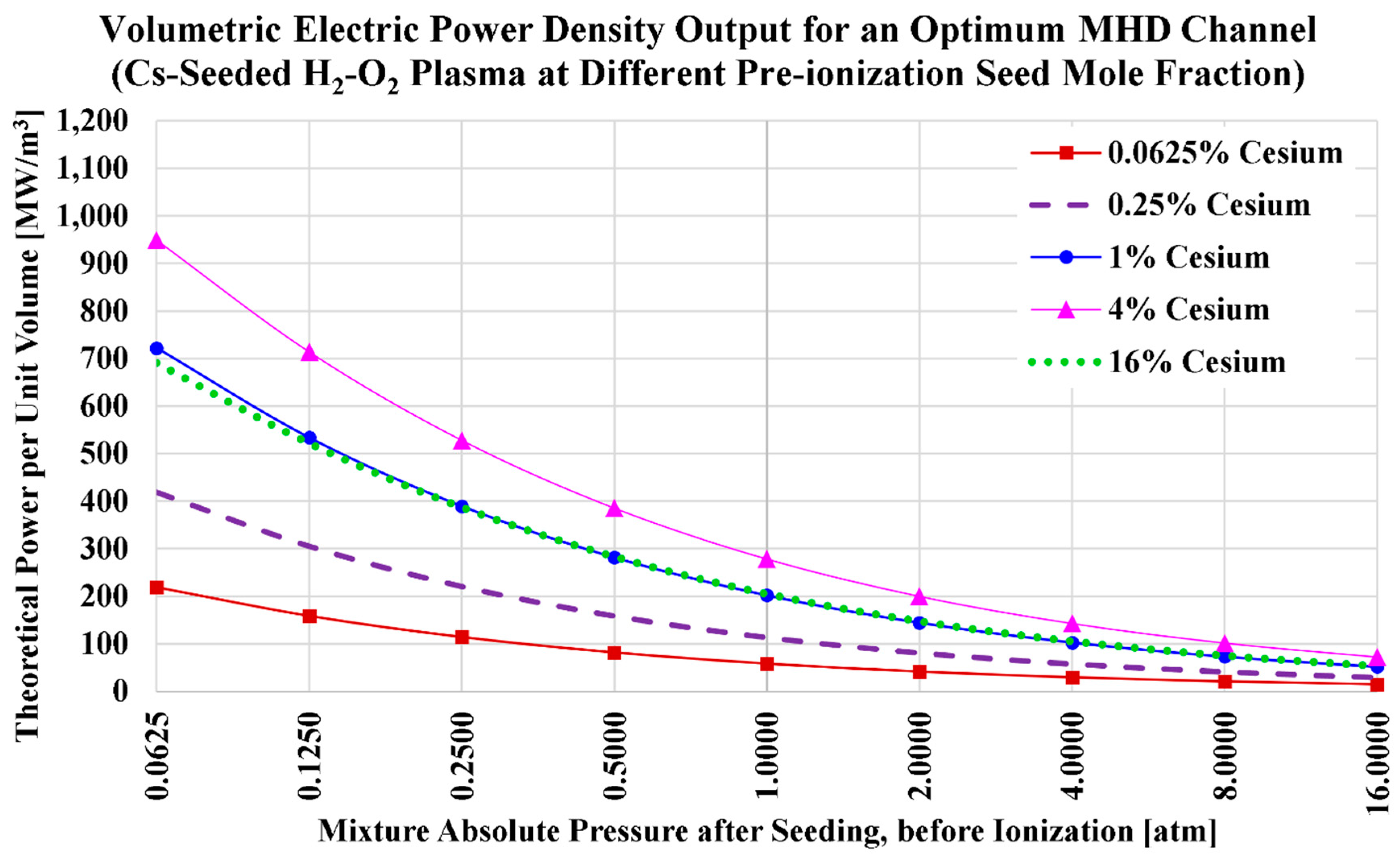

Using the presented values of the speed of sound (see

Table 6) and the values of the electric conductivity (see

Table 7) in Equation (16) gives the corresponding ideal volumetric power densities (

) for the current H2MHD case of cesium seeding and air oxidizer. The (

) results are visualized in

Figure 3, and listed in

Table 8. We also add in the table the power density values at a pre-ionization cesium mole fraction of

, which approximately corresponds to the maximized power density for this case (air-hydrogen combustion plasma with cesium seed).

Like the electric conductivity, the power density declines monotonically and nonlinearly as the total pressure increases. Also, like the electric conductivity, the power density exhibits a peak when the cesium level increases, and then it starts to decrease. However, unlike the case of the electric conductivity (), the cesium level for maximizing the power density () has shifted down from being close to 6% to being close to 3%. This shift is explained by the simultaneous decline in the speed of sound as the cesium level increases. This added effect of the speed of sound (which quadratically affects the power density) favors lower cesium values for maximizing the power density.

The tabulated data is helpful in quantifying potential ranges of the power density in the current case of cesium seed and air oxidizer. Considering the five selected seed levels (0.0625%, 0.25%, 1%, 4%, and 16%); the best obtained power density is 1,139.332 MW/m3 (at 4% cesium and 0.0625 atm); and the worst obtained power density is 23.854 MW/m3 (at 0.0625% cesium and 16 atm). At an atmospheric pressure, a promising power density of 362.806 MW/m3 is attainable with 4% cesium, and an attractive power density of 298.752 MW/m3 is attainable with only 1% cesium. Even with 0.25% cesium, a power density of 177.106 MW/m3 can be achieved at atmospheric combustion. These are favorably intense power densities, and all of them exceed well our voluntary threshold criterion of 100 MW/m3; which we found to require a minute amount of cesium seed (at 1 atm) that is not more than 0.08% Cs (at which ).

3.2. Potassium Seed and Air Oxidizer

The second set of results corresponds to the condition of using potassium vapor as the ionizable gas, and using air as the oxidizer for the hydrogen combustion. Thus, compared to the previous set of results in the preceding subsection, the only change made here is changing the seed type from cesium to potassium.

Before presenting the results of this change, it is useful to mention here that due to the higher ionization energy of potassium compared to cesium; potassium is harder to lose its valence electron in its outermost orbital (4s

1) [

242,

243,

244] upon heating compared to cesium, whose outermost valence electron is in (6s

1) [

245,

246,

247]. Therefore, it is expected that this change is accompanied by a drop in the H2MHD performance, primarily because of a decline in the electric conductivity. However, due to the nonlinearity of the problem and the present influence from other factors (particularly the speed of sound), the exact effect of this change in the seed type is not easy to predict analytically. Thus, our computational modeling becomes valuable in understanding quantitatively and qualitatively the implications of this single change.

In

Table 9, we provide our computed thermochemical characteristics for the seeded gas mixture before ionization. Similar to the case of cesium seeding, the mixture’s gas constant (

) decreases (and the mixture’s molecular weight increases) as the level of potassium increases. However, this decrease in the case of potassium additive is much weaker than in the case of cesium additive due to the weaker difference in the molecular weight between potassium (K) and either molecular nitrogen (N

2) or water vapor (H

2O). One mole of potassium (K) is only 1.396 times heavier than one mole of molecular nitrogen (N

2), and 2.170 times heavier than one mole of water (H

2O).

As a reference; the molecular weight of the combustion products without any seeding (34.710170% H2O and 65.289830% N2 by mole) is 24.54304 kg/kmol; the unseeded-mixture’s gas constant is 338.7707 J/(kg.K); the unseeded-mixture’s specific heat ratio is 1.243900; and the unseeded-mixture’s speed of sound (at 2,300 K) is 984.486 m/s.

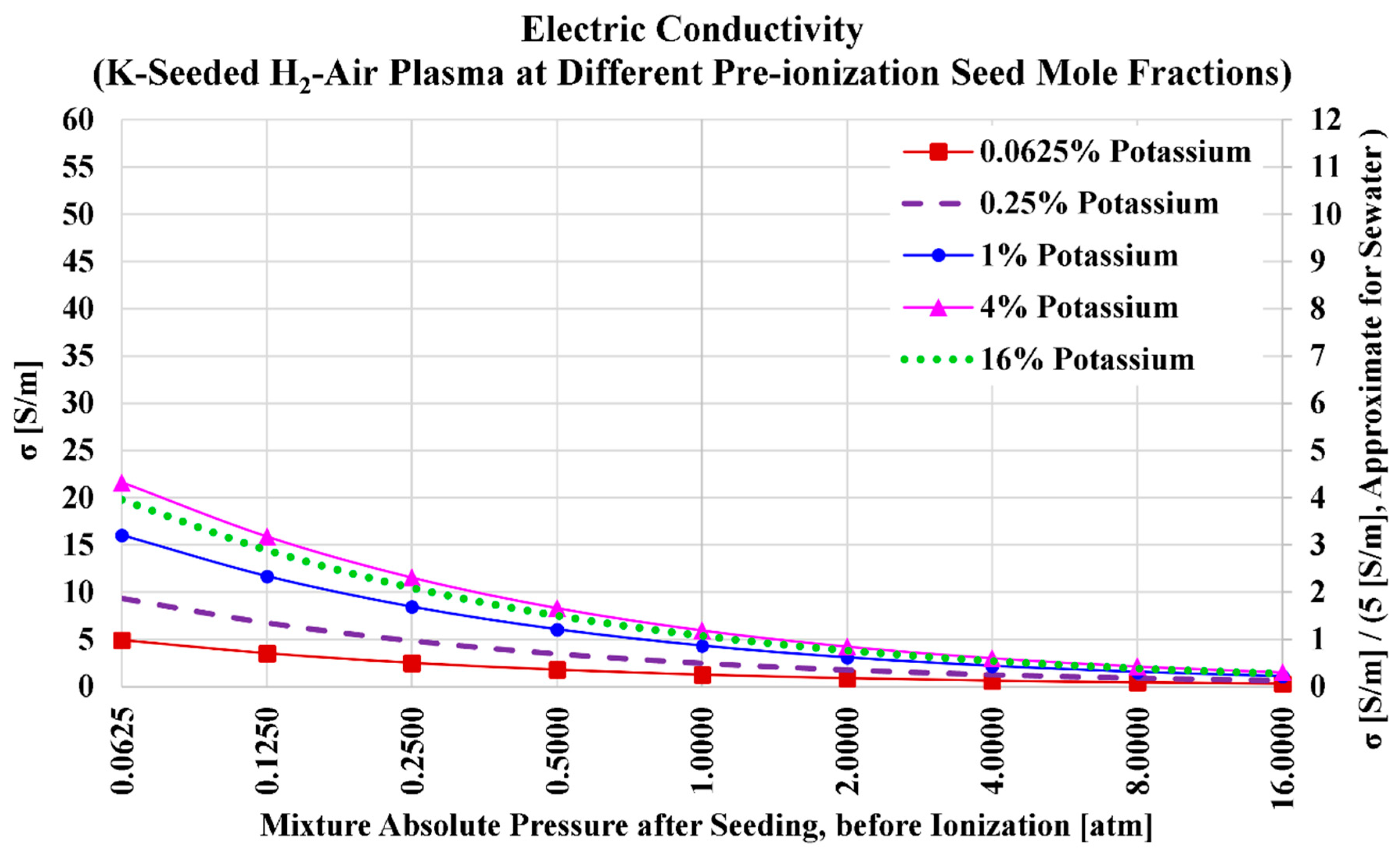

Figure 4 shows how the electric conductivity of the hydrogen plasma monotonically and nonlinearly drops as the total pre-ionization absolute pressure increases. This is qualitatively similar to what was observed when cesium was the additive seed. Also, the existence of a peak electric conductivity at a certain level of potassium seed is similar to what was observed in the case of cesium. This potassium level that maximizes the electric conductivity is again (as was the case in the cesium case) approximately near 6%. It is noticeable that the electric conductivity (or any given level of seeding) dropped strongly when the seed is changed from cesium to potassium. For example, the maximum obtained electric conductivity in the case of cesium was 55.0610 S/m (at

and 0.0625 atm) is 2.55 times the maximum obtained electric conductivity in the case of potassium, which is 21.6201 S/m (at

and 0.0625 atm).

Table 10 lists the numerical values of the plasma electric conductivity as visualized in the previous figure. We also add in the table the electric conductivity values at a pre-ionization cesium mole fraction of

, which approximately corresponds to the maximized electric conductivity for this case (air-hydrogen combustion plasma with potassium seed).

Considering the five selected seed levels (0.0625%, 0.25%, 1%, 4%, and 16%), the highest obtained electric conductivity is (at and ). At the higher (and the same total pressure of 0.0625 atm), the electric conductivity is slightly lower, with a value of 19.7671 S/m; while at the lower (and the same total pressure of 0.0625 atm), the electric conductivity is mildly lower, with a value of 16.0343 S/m. If we take a total pressure of 1 atm (atmospheric MHD channel) as a reference, one can see that the electric conductivity is restricted to 6 S/m.

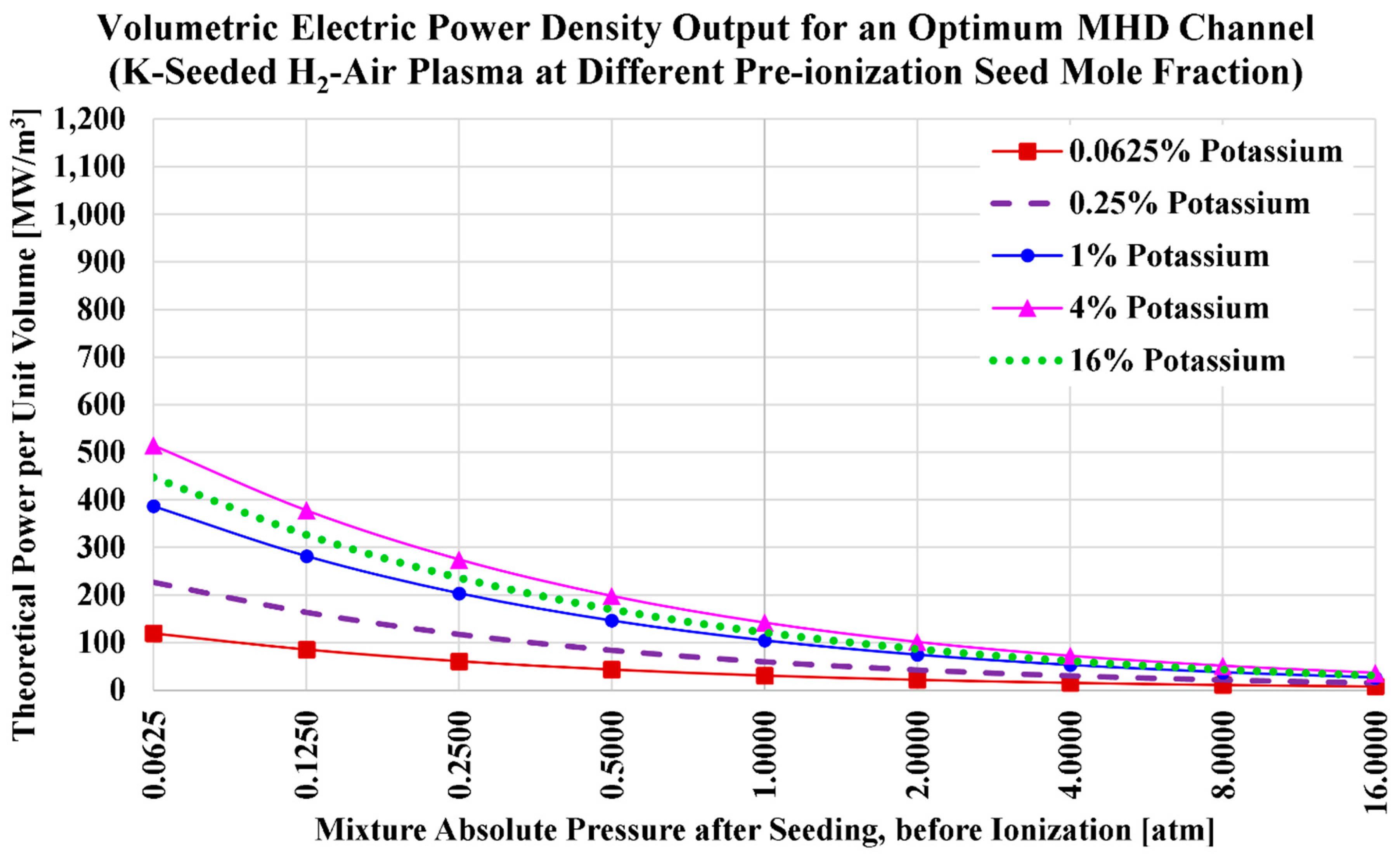

The ideal volumetric power densities (

) for the current H2MHD case of potassium seeding and air oxidizer are visualized in

Figure 5, and listed in

Table 11. We also add in the table the power density values at a pre-ionization cesium mole fraction of

, which approximately corresponds to the maximized power density for this case (air-hydrogen combustion plasma with potassium seed).

Unlike the case of cesium seeding, the peak power density with potassium seeding occurs near a seed level of 5% (not 3%), which is close to the potassium seeding level that maximizes the electric conductivity. This similarity of the potassium seed level () that maximizes the electric conductivity and the one that maximizes the power density is related to the near-neutral influence of the seed level on the speed of sound for the case of potassium seed (much weaker influence than the case of cesium seed). A nonlinear monotonic decline in the power density () as the total pressure () increases is noted for any potassium level, and this behavior resembles the one found earlier for the case of cesium seeding.

The power density with potassium seeding is clearly smaller than the one with cesium seeding (when other settings are kept the same). For example; considering the five selected seed levels (0.0625%, 0.25%, 1%, 4%, and 16%), the largest obtained power density at 1 atm in the case of potassium seeding is 141.808 MW/m3 (with ). This is 2.56 times the power density at 1 atm and , which was 362.806 MW/m3. Although potassium seeding is associated with higher speeds of sound compared to cesium seeding, this small advantage for potassium seeding is largely counteracted by the big penalty in the electric conductivity due to changing the seed vapor from cesium to potassium.

Despite the drop in the power density in the case of potassium seeding, the power density can still exceed 100 MW/m3 at 1 atm, with as small potassium levels as 1%. Thus, the H2MHD concept is still viable.

3.3. Potassium Seed and Oxygen Oxidizer

The third set of results corresponds to the condition of using potassium vapor as the ionizable gas, and using pure oxygen as the oxidizer for the hydrogen combustion. Thus, compared to the previous set of results in the preceding subsection, the only change made here is changing the oxidizer type from air (oxygen-nitrogen mixture) to pure oxygen.

Before presenting the results of this change, it is useful to mention here that due to the absence of nitrogen from the combustion products, hydrogen combustion results in pure water vapor (H2O). Water vapor has a relatively low molecular weight and thus has a relatively high specific gas constant. Therefore, the speed of sound in the current case of oxy-combustion of hydrogen is higher than the speed of sound in the previous case of air-combustion of hydrogen (for the same level of potassium seed). Therefore, it is expected that the change of the oxidizer (from air to oxygen) improves the speed of sound, and thus the plasma speed (given its fixed relation to the speed of sound in our study). It is thus the change in the electric conductivity that determines how eventually the power density is affected by the change of the oxidizer (from air to oxygen). This is difficult to predict without numerical simulations as done in our study. This emphasizes the value and contribution made by our study to the field of MHD power generation, through quantitatively and qualitatively investigating the influence of the oxidizer on the MHD power generation process.

In

Table 12, we provide our computed thermochemical characteristics for the seeded gas mixture before ionization. As mentioned earlier, the specific gas constant and the speed of sound in the current case of oxy-hydrogen combustion are higher than their values in the previous case of air-hydrogen combustion. For example, with 1% potassium seed; the speed of sound with oxy-hydrogen combustion (1,114.801 m/s) is 1.135 times the speed of sound with air-hydrogen combustion (982.178 m/s) with the same level of potassium seeding. Due to the larger molecular weight of potassium compared to water waver; the more the added potassium, the higher the mixture’s molecular weight and thus the lower the mixture’s gas constant and the lower the speed of sound in that mixture of water vapor and potassium vapor. The mixture’s specific gas constant (

) increases as the potassium level increases, but the decrease in the mixture’s gas constant (

) is stronger; and thus, ultimately the speed of sound decreases when the potassium level increases.

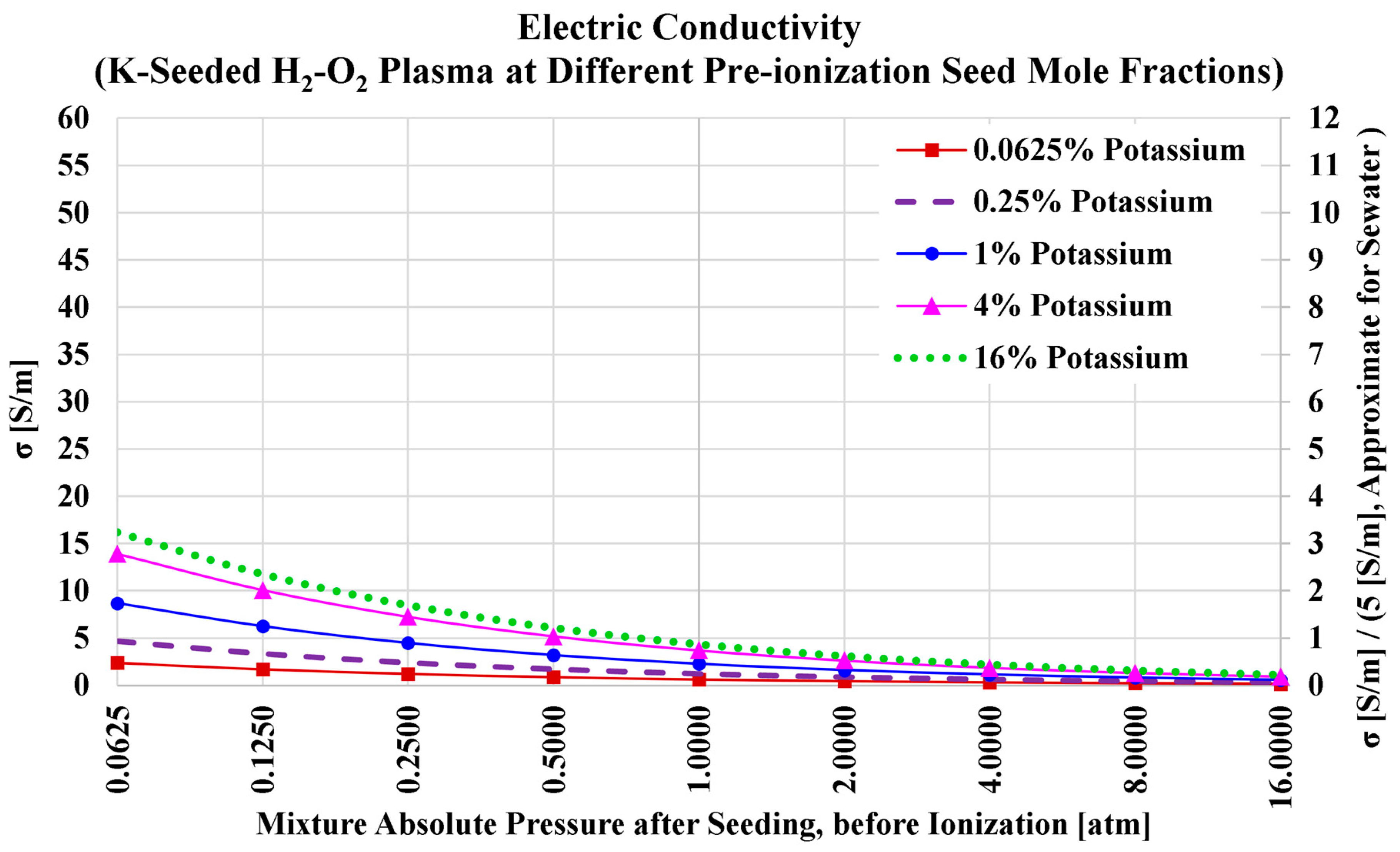

Figure 6 shows the profiles of the electric conductivity of the hydrogen plasma. The monotonic and nonlinear drop as the total pre-ionization absolute pressure increases is retained, similar to the previous case of air-hydrogen combustion. However, there are two remarkable changes that can be observed from the figure when compared to its counterpart in the previous subsection of air-hydrogen combustion (with the same potassium seeding).

The first change worthy of attention is the overall suppression of the electric conductivity. This can be attributed to the larger effective electron-neutral momentum transfer collision cross-section for water vapor compared to molecular nitrogen [

248,

249,

250,

251]. Thus, when the molecular nitrogen in the combustion products is replaced with water vapor, the electrons mobility is retarded, and this suppresses the electric conductivity of the plasma.

The second change worthy of attention is that now with oxy-hydrogen combustion, the electric conductivity with 16% potassium is larger than the electric conductivity with 4% potassium. In the previous case of air-hydrogen combustion, the electric conductivity with 16% potassium was smaller than the electric conductivity with 4% potassium, due to the detrimental effect of over-seeding. In fact, while the electric conductivity with 16% potassium is larger than the electric conductivity with 4% potassium in the current case of oxy-hydrogen combustion, the peak electric conductivity has been already passed at . This means that this peaking phenomenon of the electric conductivity is actually still present in the current case of oxy-hydrogen plasma. The main difference is that this peak was easy to notice in the previous electric conductivity figure corresponding to air-hydrogen plasma with potassium seeding (in the previous subsection) because the potassium mole fraction () that maximized the electric conductivity was closer to the intermediate value of 4% than the terminal value of 16%. Changing the oxidizer from air to oxygen causes this particular () of maximized electric conductivity () to shift to a larger position, becoming closer to the terminal value of 16% (but below it; located nearly at ). Despite the gain in the electric conductivity when the potassium seed mole fraction () is increased from 4% to 16% (or 13%), the gain is too small to justify the need for exceeding the seed level beyond 4%.

Table 13 lists the numerical values of the plasma electric conductivity as visualized in the previous figure. We also add in the table the electric conductivity values at a pre-ionization potassium mole fraction of

, which approximately corresponds to the maximized electric conductivity for this case (oxy-hydrogen combustion plasma with potassium seed).

Considering the five selected seed levels (0.0625%, 0.25%, 1%, 4%, and 16%), the highest obtained electric conductivity is (at and ). At the lower (and the same total pressure of 0.0625 atm), the electric conductivity is mildly lower, with a value of 13.9154 S/m. If we take a total pressure of 1 atm as a reference, one can see that the electric conductivity is below 5 S/m (the approximate electric conductivity of seawater) regardless of the seeding level.

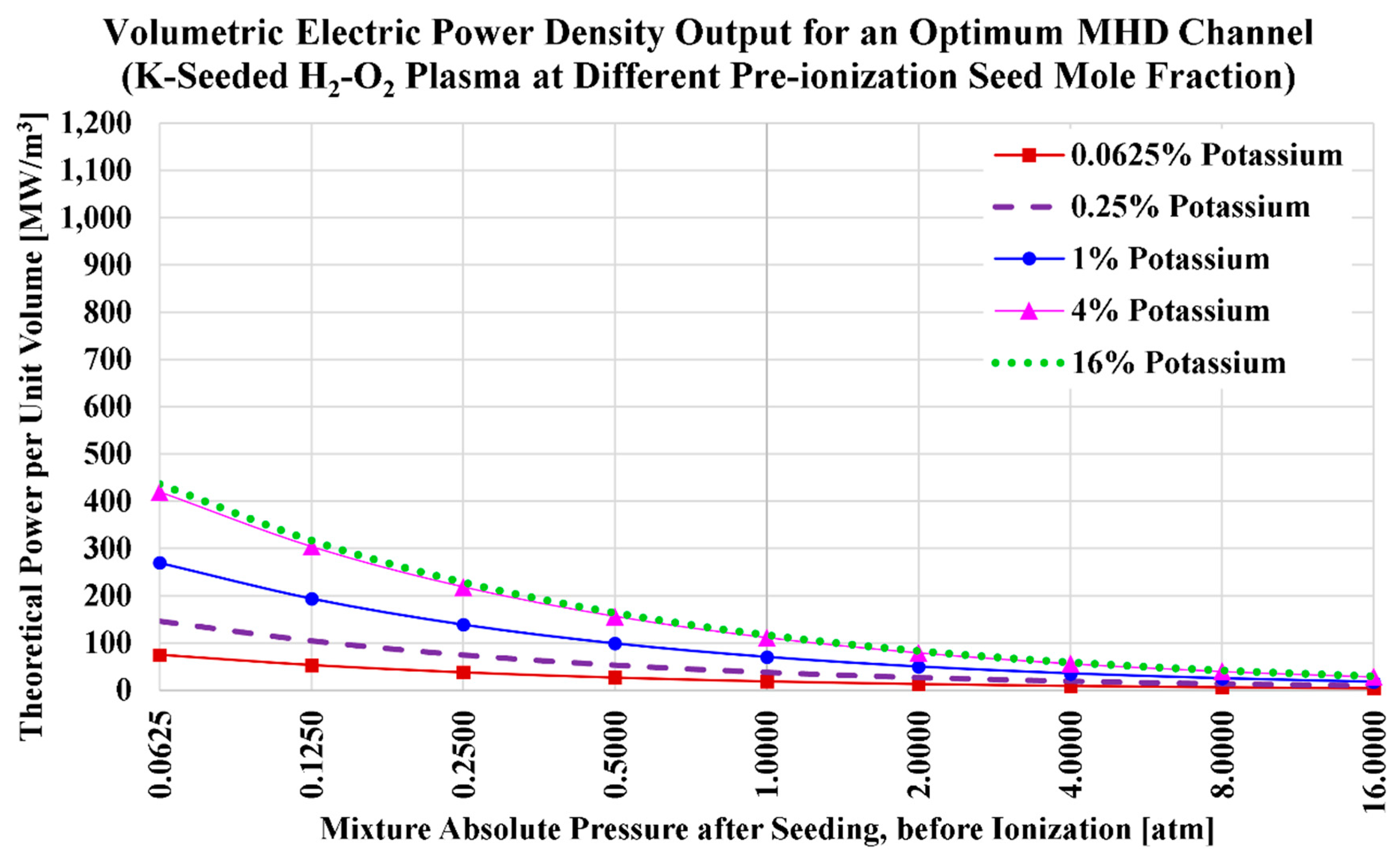

The ideal volumetric power densities (

) for the current H2MHD case of potassium seeding and oxygen oxidizer are visualized in

Figure 7, and listed in

Table 14. We also add in the table the power density values at a pre-ionization cesium mole fraction of

, which approximately corresponds to the maximized power density for this case (oxy-hydrogen combustion plasma with potassium seed).

The electric conductivity () at a potassium seed level () was found to be larger than the electric conductivity at (). Similarly, the volumetric power density () at a potassium seed level () is larger than the power density at (). However; because the speed of sound (and thus the plasma speed) at () is larger than its value at (), the gap in () is diminished when the seed levels of 4% and 16% are compared.

When comparing the range of () here with those in the previous subsection (air-combustion instead of oxy-combustion); we notice that although the power density dropped, this drop is not large. For example, at 1 atm and 4% potassium, the power density here with oxy-combustion is 111.573 MW/m3, while it was 141.808 MW/m3 in the previous case of air-combustion. The difference (30.2350 MW/m3) is 23.9% of the average of both values (126.6905 MW/m3).

For exceeding the threshold power density of 100 MW/m3, the potassium seed level should not be below 3% (at which we found that and ; thus, )

3.4. Cesium Seed and Oxygen Oxidizer

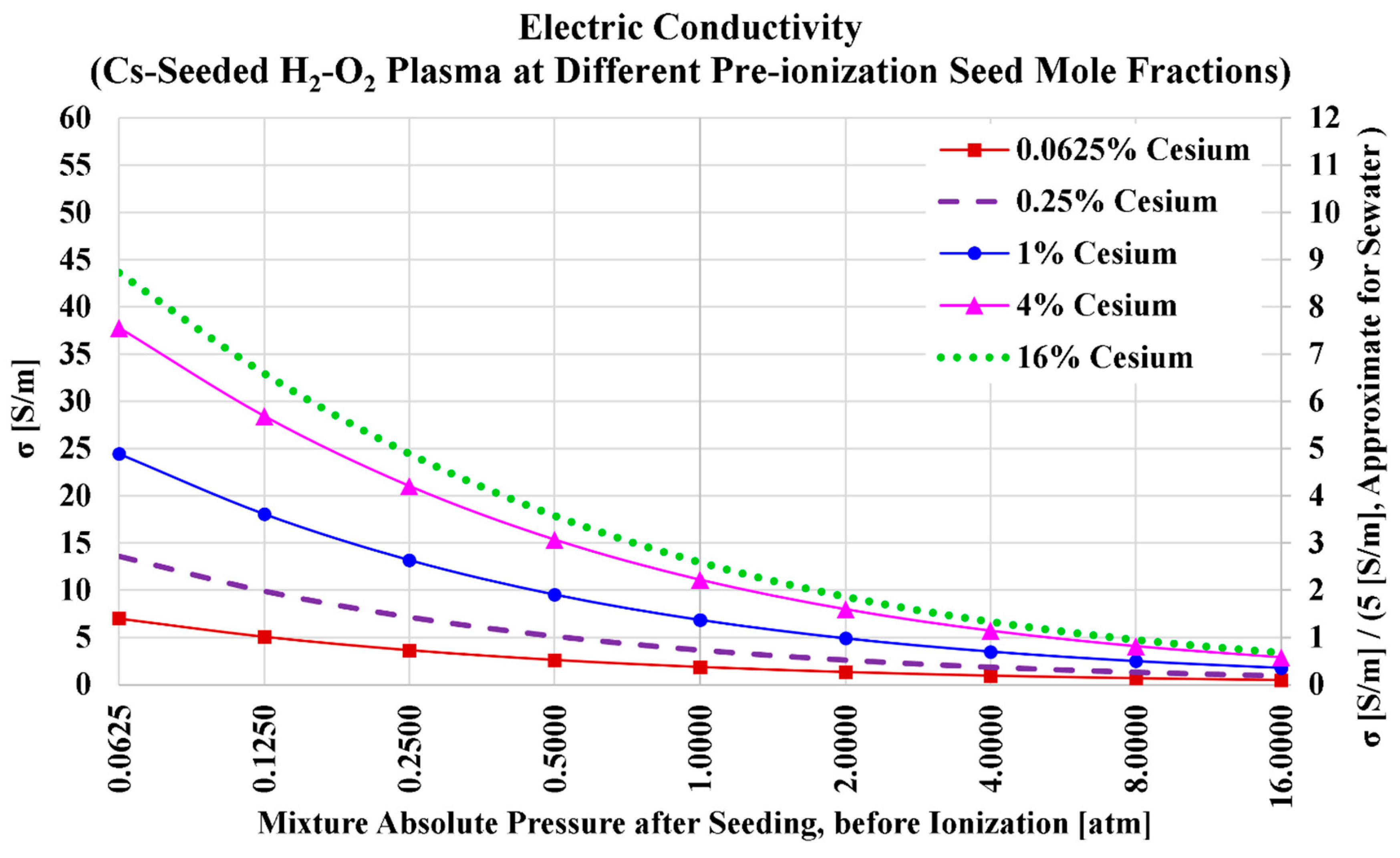

The fourth (and final) set of results corresponds to the condition of using cesium vapor as the ionizable gas, and using pure oxygen as the oxidizer for the hydrogen combustion. Thus, compared to the previous set of results in the preceding subsection, the only change made here is changing the seed type from potassium to cesium.

In

Table 15, we provide our computed thermochemical characteristics for the seeded gas mixture before ionization. The speed of sound drops faster with the cesium fraction compared to the previous case of potassium seeding, due to the large influence of cesium on the mixture’s gas constant compared to potassium; this is because the cesium atom is 3.399 times heavier than the potassium atom. For example; at the same mole fraction of 4%, the speed of sound in the case of cesium seeding is 1,002.552 m/s, which was larger (1,097.826 m/s) in the case of potassium seeding. For comparison purposes, the speed of sound in pure water vapor (at 2,300 K) is 1,120.682 m/s. Thus, introducing a fraction of 4% cesium vapor causes a relative drop in this original speed of sound (1,120.682 m/s) by 118.130 m/s or 10.54%. On the other hand, introducing a fraction of 4% potassium vapor causes a relative drop in the original speed of sound (1,120.682 m/s) by only 22.856 m/s or 2.04%.

In addition, it may be useful to add that for unseeded water vapor (H2O), the specific gas constant is 461.5223 J/(kg.K), and the specific heat ratio is 1.183162.

Figure 8 shows how the variation of the electric conductivity of the hydrogen plasma with the total absolute pressure at the five selected cesium levels. The variations show a monotonical nonlinear drop as observed in all previous cases (the three preceding subsections). However, compared to the previous subsection particularly, the electric conductivity is largely boosted here after replacing the seed from potassium (the previous subsection) to cesium (the current subsection). For example, at 1 atm and

, the electric conductivity (

) here is 11.0877 S/m. But in the previous case, at 1 atm and

, this electric conductivity was 3.7030 S/m. The ratio of the two values of (

) is 2.99.

Also, as in the previous set of results (oxy-hydrogen combustion with potassium seeding), the seeding level at which the electric conductivity is maximized is larger than that level in the case of air-hydrogen combustion. That seeding level of maximum () is approximately 13% in the current case of oxy-hydrogen combustion with cesium seeding (while it was near 6% in the case of air-hydrogen combustion with cesium seeding).

Table 16 lists the numerical values of the plasma electric conductivity as visualized in the previous figure. We also add in the table the electric conductivity values at a pre-ionization cesium mole fraction of

, which approximately corresponds to the maximized electric conductivity for this case (oxy-hydrogen combustion plasma with cesium seed).

Considering the five selected seed levels (0.0625%, 0.25%, 1%, 4%, and 16%), the highest obtained electric conductivity is (at and ). At the lower (and the same total pressure of 0.0625 atm), the electric conductivity is mildly lower, with a value of 37.7620 S/m (thus, 13.36% of the value of 43.5831 S/m at 16% cesium is lost). If we take a total pressure of 1 atm as a reference, an electric conductivity of 10 S/m is achievable with a cesium mole fraction of 3% (at which the electric conductivity is 10.2333 S/m).

The ideal volumetric power densities (

) for the current H2MHD case of cesium seeding and oxygen oxidizer are visualized in

Figure 9, and listed in

Table 17. We also add in the table the power density values at a pre-ionization cesium mole fraction of

, which approximately corresponds to the maximized power density for this case (oxy-hydrogen combustion plasma with cesium seed).

Like the case of cesium seeding with air-hydrogen combustion, but unlike the previous case of potassium seeding and oxy-hydrogen combustion; the power density here with 4% Cs is larger than the power density with 16% seed. This is a combined effect of how the electric conductivity () and the speed of sound () respond to changes in the cesium mole fraction (); which is different from their responses to changes in the potassium mole fraction ().

The power density with cesium seeding (the current subsection) is clearly larger than the one with potassium seeding (the previous subsection).

A power density of 100 MW/m3 or more is easily attainable at 1 atm, requiring a small mole fraction of cesium seed such as 0.25% only. Even with , we obtain .

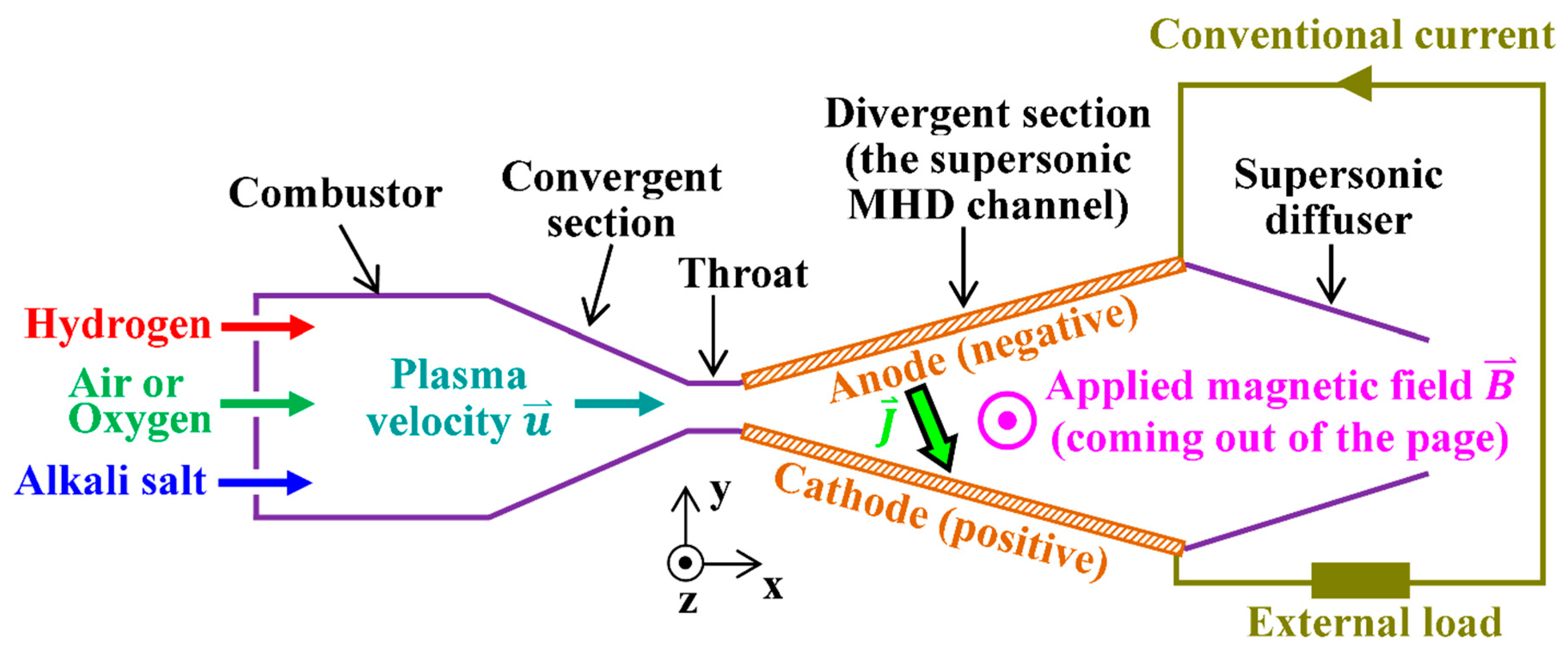

Figure 1.

The hydrogen magnetohydrodynamic (H2MHD) generator power system.

Figure 1.

The hydrogen magnetohydrodynamic (H2MHD) generator power system.

Figure 2.

Electric conductivity in the case of cesium seed and air oxidizer.

Figure 2.

Electric conductivity in the case of cesium seed and air oxidizer.

Figure 3.

Ideal power density in the case of cesium seed and air oxidizer.

Figure 3.

Ideal power density in the case of cesium seed and air oxidizer.

Figure 4.

Electric conductivity in the case of potassium seed and air oxidizer.

Figure 4.

Electric conductivity in the case of potassium seed and air oxidizer.

Figure 5.

Ideal power density in the case of potassium seed and air oxidizer.

Figure 5.

Ideal power density in the case of potassium seed and air oxidizer.

Figure 6.

Electric conductivity in the case of potassium seed and oxygen oxidizer.

Figure 6.

Electric conductivity in the case of potassium seed and oxygen oxidizer.

Figure 7.

Ideal power density in the case of potassium seed and oxygen oxidizer.

Figure 7.

Ideal power density in the case of potassium seed and oxygen oxidizer.

Figure 8.

Electric conductivity in the case of cesium seed and oxygen oxidizer.

Figure 8.

Electric conductivity in the case of cesium seed and oxygen oxidizer.

Figure 9.

Ideal power density in the case of cesium seed and oxygen oxidizer.

Figure 9.

Ideal power density in the case of cesium seed and oxygen oxidizer.

Table 1.

Example uses of Hydrogen.

Table 1.

Example uses of Hydrogen.

| Serial number |

Characteristics |

References |

| 1. |

Oil refinery |

[7,8,9] |

| 2. |

Fuel cell power units |

[10,11,12] |

| 3. |

Synthetizing ammonia |

[13,14,15,16] |

| 4. |

Electrified-type hydrogen-powered transport |

[17,18,19,20,21,22] |

| 5. |

Synthetizing methanol |

[23,24,25] |

| 6. |

Gas turbines powered by hydrogen or hydrogen-blended gas |

[26,27,28] |

| 7. |

Synthetizing hydrocarbon fuels |

[29,30,31,32] |

| 8. |

Aerospace and rocket propulsion |

[33,34,35,36,37] |

| 9. |

Reduction processes to extract a metal from its ore |

[38,39,40,41] |

| 10. |

Combustion-type hydrogen-powered transport |

[42,43,44] |

| 11. |

Specialized welding operations |

[45,46,47] |

| 12. |

Food industry |

[48,49,50] |

| 13. |

Cooling of turbogenerator winding |

[51,52,53,54] |

Table 2.

Three fixed parameters in the current study.

Table 2.

Three fixed parameters in the current study.

| Fixed Parameter |

Value |

References |

| Temperature |

2,300 K = 2,026.85 °C |

[149,150,151] |

| Magnetic-field flux density |

5 T (5 teslas) = 5,000 G (50,000 gausses) |

[152,153,154,155] |

| Mach number |

2 |

[156,157,158] |

Table 3.

Molecular weights used in the current study.

Table 3.

Molecular weights used in the current study.

| Gaseous Species |

Molecular Weight [kg/kmol] |

Reference |

| Water vapor (H2O) |

18.0153 |

[184] |

| Nitrogen (N2) |

28.0134 |

[185] |

| Cesium vapor (Cs) |

132.9054519 |

[186] |

| Potassium vapor (K) |

39.0983 |

[187] |

Table 4.

Fitting coefficients of the specific heat capacities at constant pressure.

Table 4.

Fitting coefficients of the specific heat capacities at constant pressure.

|

) |

) |

| H2O |

N2 |

Cs |

K |

|

1.034972096e06 |

5.877124060e05 |

6.166040900e06 |

–3.566422360e06 |

|

–2.412698562e03 |

–2.239249073e03 |

–1.896175522e04 |

1.085289825e04 |

|

4.646110780e00 |

6.066949220e00 |

2.483229903e01 |

–1.054134898e01 |

|

2.291998307e–03 |

–6.139685500e–04 |

–1.251977234e–02 |

8.009801350e–03 |

|

–6.836830480e–07 |

1.491806679e–07 |

3.309017390e–06 |

–2.696681041e–06 |

|

9.426468930e–11 |

–1.923105485e–11 |

–3.354012020e–10 |

4.715294150e–10 |

|

–4.822380530e–15 |

1.061954386e–15 |

9.626500908e–15 |

–2.976897350e–14 |

Table 6.

Pre-ionization properties of cesium-seeded air-hydrogen combustion mixture.

Table 6.

Pre-ionization properties of cesium-seeded air-hydrogen combustion mixture.

| Property |

) |

| 0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

4% |

16% |

|

[%]

|

0.062500% |

0.250000% |

1.000000% |

4.000000% |

16.000000% |

|

[%]

|

34.688476% |

34.623395% |

34.363068% |

33.321763% |

29.156543% |

|

[%]

|

65.249024% |

65.126605% |

64.636932% |

62.678237% |

54.843457% |

|

[kg/kmol]

|

24.611 |

24.814 |

25.627 |

28.878 |

41.881 |

|

[J/(kg.K)]

|

337.8384 |

335.0721 |

324.4457 |

287.9214 |

198.5258 |

|

[-]

|

1.243991 |

1.244265 |

1.245365 |

1.249869 |

1.269668 |

|

[m/s]

|

983.166 |

979.241 |

964.014 |

909.773 |

761.408 |

|

[m/s]

|

1,966.33 |

1,958.48 |

1,928.03 |

1,819.55 |

1,522.82 |

Table 7.

Electric conductivity [S/m] of hydrogen plasma (cesium seed, air oxidizer).

Table 7.

Electric conductivity [S/m] of hydrogen plasma (cesium seed, air oxidizer).

| Pressure [atm] |

Plasma Electric Conductivity [S/m] (at the Different Cesium Levels) |

| 0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

4% |

6% |

16% |

| 0.0625 |

14.0116 |

25.8383 |

42.2099 |

55.0610 |

56.0605 |

51.7766 |

| 0.125 |

10.2858 |

19.2426 |

32.1752 |

42.6407 |

43.4010 |

39.6267 |

| 0.25 |

7.4702 |

14.1237 |

24.0379 |

32.2535 |

32.8188 |

29.6901 |

| 0.5 |

5.3830 |

10.2551 |

17.6829 |

23.9483 |

24.3616 |

21.8837 |

| 1 |

3.8573 |

7.3878 |

12.8589 |

17.5335 |

17.8321 |

15.9340 |

| 2 |

2.7530 |

5.2923 |

9.2729 |

12.7050 |

12.9189 |

11.4995 |

| 4 |

1.9593 |

3.7762 |

6.6470 |

9.1379 |

9.2904 |

8.2470 |

| 8 |

1.3917 |

2.6869 |

4.7447 |

6.5378 |

6.6461 |

5.8882 |

| 16 |

0.9871 |

1.9081 |

3.3768 |

4.6603 |

4.7371 |

4.1912 |

Table 8.

Power density [MW/m3] of hydrogen plasma (cesium seed and air oxidizer).

Table 8.

Power density [MW/m3] of hydrogen plasma (cesium seed and air oxidizer).

| Pressure [atm] |

Volumetric Power Density [MW/m3] (at the Different Cesium Levels) |

| 0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

3% |

4% |

16% |

| 0.0625 |

338.596 |

619.417 |

980.665 |

1,146.828 |

1,139.332 |

750.427 |

| 0.125 |

248.561 |

461.299 |

747.529 |

886.885 |

882.329 |

574.332 |

| 0.25 |

180.520 |

338.585 |

558.474 |

670.107 |

667.395 |

430.315 |

| 0.5 |

130.082 |

245.844 |

410.828 |

497.150 |

495.543 |

317.173 |

| 1 |

93.213 |

177.106 |

298.752 |

363.771 |

362.806 |

230.940 |

| 2 |

66.527 |

126.871 |

215.438 |

263.484 |

262.894 |

166.669 |

| 4 |

47.347 |

90.526 |

154.430 |

189.454 |

189.083 |

119.528 |

| 8 |

33.631 |

64.413 |

110.234 |

135.521 |

135.281 |

85.341 |

| 16 |

23.854 |

45.743 |

78.453 |

96.591 |

96.432 |

60.745 |

Table 9.

Pre-ionization properties of potassium-seeded air-hydrogen combustion mixture.

Table 9.

Pre-ionization properties of potassium-seeded air-hydrogen combustion mixture.

| Property |

) |

| 0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

4% |

16% |

|

[%]

|

0.062500% |

0.250000% |

1.000000% |

4.000000% |

16.000000% |

|

[%]

|

34.688476% |

34.623395% |

34.363068% |

33.321763% |

29.156543% |

|

[%]

|

65.249024% |

65.126605% |

64.636932% |

62.678237% |

54.843457% |

|

[kg/kmol]

|

24.552 |

24.579 |

24.689 |

25.125 |

26.872 |

|

[J/(kg.K)]

|

338.6451 |

338.2691 |

336.7734 |

330.9206 |

309.4112 |

|

[-]

|

1.243994 |

1.244278 |

1.245418 |

1.250087 |

1.270686 |

|

[m/s]

|

984.341 |

983.906 |

982.178 |

975.430 |

950.935 |

|

[m/s]

|

1,968.68 |

1,967.81 |

1,964.36 |

1,950.86 |

1,901.87 |

Table 10.

Electric conductivity [S/m] of hydrogen plasma (potassium seed, air oxidizer).

Table 10.

Electric conductivity [S/m] of hydrogen plasma (potassium seed, air oxidizer).

| Pressure [atm] |

Plasma Electric Conductivity [S/m] (at the Different Potassium Levels) |

| 0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

4% |

6% |

16% |

| 0.0625 |

4.9217 |

9.3443 |

16.0343 |

21.6201 |

21.9827 |

19.7671 |

| 0.125 |

3.5282 |

6.7405 |

11.6895 |

15.8856 |

16.1504 |

14.4434 |

| 0.25 |

2.5189 |

4.8334 |

8.4459 |

11.5428 |

11.7342 |

10.4518 |

| 0.5 |

1.7931 |

3.4513 |

6.0630 |

8.3195 |

8.4568 |

7.5108 |

| 1 |

1.2739 |

2.4570 |

4.3325 |

5.9617 |

6.0597 |

5.3707 |

| 2 |

0.9037 |

1.7456 |

3.0859 |

4.2546 |

4.3243 |

3.8271 |

| 4 |

0.6405 |

1.2383 |

2.1931 |

3.0277 |

3.0772 |

2.7205 |

| 8 |

0.4536 |

0.8776 |

1.5561 |

2.1502 |

2.1853 |

1.9307 |

| 16 |

0.3211 |

0.6215 |

1.1029 |

1.5250 |

1.5499 |

1.3686 |

Table 11.

Power density [MW/m3] of hydrogen plasma (potassium seed and air oxidizer).

Table 11.

Power density [MW/m3] of hydrogen plasma (potassium seed and air oxidizer).

| Pressure [atm] |

Volumetric Power Density [MW/m3] (at the Different Potassium Levels) |

| 0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

4% |

5% |

16% |

| 0.0625 |

119.219 |

226.149 |

386.697 |

514.268 |

518.972 |

446.874 |

| 0.125 |

85.464 |

163.132 |

281.914 |

377.864 |

381.364 |

326.521 |

| 0.25 |

61.016 |

116.977 |

203.689 |

274.564 |

277.128 |

236.283 |

| 0.5 |

43.435 |

83.528 |

146.221 |

197.892 |

199.751 |

169.796 |

| 1 |

30.858 |

59.464 |

104.486 |

141.808 |

143.144 |

121.415 |

| 2 |

21.890 |

42.247 |

74.422 |

101.202 |

102.158 |

86.519 |

| 4 |

15.515 |

29.969 |

52.891 |

72.019 |

72.698 |

61.502 |

| 8 |

10.988 |

21.239 |

37.528 |

51.146 |

51.631 |

43.647 |

| 16 |

7.778 |

15.041 |

26.598 |

36.275 |

36.618 |

30.940 |

Table 12.

Pre-ionization properties of potassium-seeded oxy-hydrogen combustion mixture.

Table 12.

Pre-ionization properties of potassium-seeded oxy-hydrogen combustion mixture.

| Property |

) |

| 0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

4% |

16% |

|

[%]

|

0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

4% |

16% |

|

[%]

|

99.9375% |

99.75% |

99% |

96% |

84% |

|

[kg/kmol]

|

18.028 |

18.068 |

18.226 |

18.859 |

21.389 |

|

[J/(kg.K)]

|

461.1850 |

460.1760 |

456.1837 |

440.8839 |

388.7337 |

|

[-]

|

1.183244 |

1.183490 |

1.184479 |

1.188543 |

1.206766 |

|

[m/s]

|

1,120.311 |

1,119.201 |

1,114.801 |

1,097.826 |

1,038.727 |

|

[m/s]

|

2,240.62 |

2,238.40 |

2,229.60 |

2,195.65 |

2,077.45 |

Table 13.

Electric conductivity [S/m] of hydrogen plasma (potassium seed, oxygen oxidizer).

Table 13.

Electric conductivity [S/m] of hydrogen plasma (potassium seed, oxygen oxidizer).

| Pressure [atm] |

Plasma Electric Conductivity [S/m] (at the Different Potassium Levels) |

| 0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

4% |

13% |

16% |

| 0.0625 |

2.3874 |

4.6735 |

8.6753 |

13.9154 |

16.2537 |

16.1854 |

| 0.125 |

1.7027 |

3.3408 |

6.2385 |

10.0857 |

11.8100 |

11.7558 |

| 0.25 |

1.2112 |

2.3803 |

4.4635 |

7.2563 |

8.5119 |

8.4704 |

| 0.5 |

0.8601 |

1.6920 |

3.1821 |

5.1932 |

6.0993 |

6.0683 |

| 1 |

0.6099 |

1.2008 |

2.2628 |

3.7030 |

4.3527 |

4.3300 |

| 2 |

0.4322 |

0.8513 |

1.6063 |

2.6335 |

3.0974 |

3.0809 |

| 4 |

0.3060 |

0.6030 |

1.1389 |

1.8696 |

2.1997 |

2.1878 |

| 8 |

0.2166 |

0.4269 |

0.8068 |

1.3256 |

1.5601 |

1.5516 |

| 16 |

0.1533 |

0.3021 |

0.5712 |

0.9391 |

1.1054 |

1.0993 |

Table 14.

Power density [MW/m3] of hydrogen plasma (potassium seed, oxygen oxidizer).

Table 14.

Power density [MW/m3] of hydrogen plasma (potassium seed, oxygen oxidizer).

| Pressure [atm] |

Volumetric Power Density [MW/m3] (at the Different Potassium Levels) |

| 0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

4% |

9% |

16% |

| 0.0625 |

74.910 |

146.352 |

269.538 |

419.279 |

458.894 |

436.583 |

| 0.125 |

53.426 |

104.618 |

193.827 |

303.888 |

333.446 |

317.099 |

| 0.25 |

38.004 |

74.540 |

138.679 |

218.636 |

240.334 |

228.479 |

| 0.5 |

26.988 |

52.985 |

98.866 |

156.474 |

172.221 |

163.685 |

| 1 |

19.137 |

37.603 |

70.304 |

111.573 |

122.907 |

116.797 |

| 2 |

13.561 |

26.659 |

49.907 |

79.349 |

87.463 |

83.104 |

| 4 |

9.601 |

18.883 |

35.385 |

56.332 |

62.116 |

59.013 |

| 8 |

6.796 |

13.368 |

25.067 |

39.941 |

44.054 |

41.853 |

| 16 |

4.810 |

9.460 |

17.747 |

28.296 |

31.215 |

29.652 |

Table 15.

Pre-ionization properties of cesium-seeded oxy-hydrogen combustion mixture.

Table 15.

Pre-ionization properties of cesium-seeded oxy-hydrogen combustion mixture.

| Property |

) |

| 0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

4% |

16% |

|

[%]

|

0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

4% |

16% |

|

[%]

|

99.9375% |

99.75% |

99% |

96% |

84% |

|

[kg/kmol]

|

18.087 |

18.303 |

19.164 |

22.611 |

36.398 |

|

[J/(kg.K)]

|

459.6900 |

454.2795 |

433.8539 |

367.7191 |

228.4336 |

|

[-]

|

1.183242 |

1.183482 |

1.184449 |

1.188419 |

1.206172 |

|

[m/s]

|

1,118.493 |

1,112.004 |

1,087.161 |

1,002.552 |

796.065 |

|

[m/s]

|

2,236.99 |

2,224.01 |

2,174.32 |

2,005.10 |

1,592.13 |

Table 16.

Electric conductivity [S/m] of hydrogen plasma (cesium seed, oxygen oxidizer).

Table 16.

Electric conductivity [S/m] of hydrogen plasma (cesium seed, oxygen oxidizer).

| Pressure [atm] |

Plasma Electric Conductivity [S/m] (at the Different Cesium Levels) |

| 0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

4% |

13% |

16% |

| 0.0625 |

6.9878 |

13.5501 |

24.4282 |

37.7620 |

43.6710 |

43.5831 |

| 0.125 |

5.0633 |

9.8700 |

18.0514 |

28.4084 |

33.0271 |

32.9308 |

| 0.25 |

3.6427 |

7.1273 |

13.1716 |

21.0071 |

24.5184 |

24.4295 |

| 0.5 |

2.6073 |

5.1146 |

9.5223 |

15.3342 |

17.9480 |

17.8732 |

| 1 |

1.8595 |

3.6539 |

6.8382 |

11.0877 |

13.0034 |

12.9440 |

| 2 |

1.3227 |

2.6023 |

4.8876 |

7.9629 |

9.3514 |

9.3060 |

| 4 |

0.9392 |

1.8492 |

3.4818 |

5.6913 |

6.6899 |

6.6560 |

| 8 |

0.6661 |

1.3121 |

2.4746 |

4.0541 |

4.7684 |

4.7435 |

| 16 |

0.4719 |

0.9300 |

1.7559 |

2.8812 |

3.3901 |

3.3721 |

Table 17.

Power density [MW/m3] of hydrogen plasma (cesium seed, oxygen oxidizer).

Table 17.

Power density [MW/m3] of hydrogen plasma (cesium seed, oxygen oxidizer).

| Pressure [atm] |

Volumetric Power Density [MW/m3] (at the Different Cesium Levels) |

| 0.0625% |

0.25% |

1% |

4% |

5% |

16% |

| 0.0625 |

218.548 |

418.885 |

721.804 |

948.874 |

947.117 |

690.486 |

| 0.125 |

158.358 |

305.119 |

533.382 |

713.839 |

714.060 |

521.722 |

| 0.25 |

113.928 |

220.332 |

389.194 |

527.861 |

528.886 |

387.036 |

| 0.5 |

81.545 |

158.112 |

281.365 |

385.314 |

386.524 |

283.165 |

| 1 |

58.157 |

112.956 |

202.055 |

278.609 |

279.721 |

205.072 |

| 2 |

41.368 |

80.447 |

144.419 |

200.090 |

201.008 |

147.435 |

| 4 |

29.374 |

57.166 |

102.880 |

143.010 |

143.725 |

105.451 |

| 8 |

20.833 |

40.562 |

73.119 |

101.870 |

102.409 |

75.151 |

| 16 |

14.759 |

28.750 |

51.883 |

72.398 |

72.793 |

53.424 |