1. Introduction

Sensory deprivation represents a classical experimental approach in neurobiology [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The pioneering studies were conducted in the visual system of developing kittens [

5], where complete or partial sensory deprivation during critical periods resulted in permanent functional impairments of visual processing. Unlike visual or auditory systems, the rodent somatosensory system permits non-invasive sensory deprivation through whisker trimming. This approach avoids tissue damage while effectively studying deprivation effects without systemic compromise [

6].

The precisely organized somatotopic structure of rodents' vibrotactile system provides exceptional opportunities for investigating critical developmental periods and neuronal plasticity [

7,

8]. The barrel cortex - the primary somatosensory representation of whiskers - derives its name from its distinctive cylindrical functional units. Each barrel receives tactile input exclusively from a single whisker, creating a precise topographic map in somatosensory cortex that mirrors the whisker arrangement on the snout [

9,

10,

11]. Whisking represents one of the earliest active behavioral patterns for environmental exploration [

12], beginning its functional maturation during postnatal days (PND) 8-9 [

13]. Extensive research has characterized both the neuronal mechanisms underlying whisking behavior and the anatomical consequences of whisker removal. Neonatal whisker trimming (vibrissectomy, VE) in rat pups does not prevent barrel formation but leads to expanded excitatory and reduced inhibitory receptive fields [

14,

15]. The affected cortical regions show area expansion, with spiny stellate neurons exhibiting increased dendritic arborization, greater spine density [

6], and modified intracortical connectivity patterns [

16] in layer IV of the somatosensory cortex in adulthood.

Despite substantial data on anatomical and electrophysiological consequences of early vibrissectomy in laboratory rodents, simple quantitative measures of immediate behavioral responses to vibrissectomy during spontaneous behavior remain lacking. Vibrissectomy from PND 0 to PND 3 resulted in impaired whisker-specific tactile function at PND30-35 [

6] and altered behavioral strategies in gap-crossing tests [

17]. Vibrissectomy impaired nipple attachment and huddling behavior when performed at PND 3-5 [

12]. Early postnatal whisker removal significantly reduced exploratory activity [

18], while prolonged vibrissectomy (PND 9-20) altered defensive behavior development, including threat response patterns [

19]. Neonatal whisker ablation caused lasting tactile discrimination deficits, with adult rats showing severe impairments in texture differentiation [

20]. Thus, nipple attachment appears to be the earliest behavioral marker sensitive to VE. However, the vibrotactile system in pups should also guide various movements before visual cues become functionally available.

In developing rat pups, locomotor activity emerges before maturation of auditory and visual systems [

21]. Initial locomotor actes are driven by olfactory and haptic input. Spatial exploration begins with spontaneous nest departures at PND 10-12 [

22]. Immature locomotor patterns (forelimb-driven propulsion and pivoting) mature to quadrupedal locomotion at PND 10-11, with digitigrade gait detectable by PND 14-15 [

23,

24,

25]. Therefore, prior to visual system activation, the role of the vibrotactile system in spatial exploration can be assessed by experimentally modulating whisker sensory input.

Movement trajectories of organisms exhibit complex characteristics due to measurement noise, micromovements, and inherent path fractality [

26,

27,

28], raising practical questions about track smoothing and quantification of its nonlinear features. By the end of the second postnatal week, rat pup locomotor patterns include both rapid progressions and lingering phases [

29,

30], the latter involving environmental scanning (lateral head movements, air sniffing, and small-step displacements). Consequently, sensory deprivation effects are more evident in lingering-related behaviors than during rapid movements, though quantifying such intermittent behaviors remains challenging [

31,

32].

At PND 13, when rat pups' vibrissae can sweep bilaterally [

13] but visual cues remain unavailable, we hypothesized that locomotion patterns at the scale of vibrissal length would be altered in vibrissectomized pups. The hypothesis was checked in the present study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals Housing

Outbred Wistar rats were obtained from the Stolbovaya breedery and mated at the Animal Chapter of IHNA&NPh, RAS. Gravid dams were individually housed in standard polycarbonate cages (dimensions: 40 × 60 × 19 cm) with wood saw bedding and additional nesting material (shredded paper towels). The housing facility maintained a 12:12 hr light/dark cycle (lights on at 08.00 A.M), controlled temperature (22 ± 2°C), and humidity (50 ± 10%). Food (standard pellet chow) and water were provided ad libitum. Cage beddings were changed twice weekly to ensure hygiene while minimizing stress. Dams were monitored daily for pups' appearance and signs of distress. To reduce disturbance near parturition, cages were left undisturbed from until postnatal day 1 (PND) 1. The birth date was designated PND 0; litters were left intact until PND 9.

2.2. Vibrissectomy

Before handling the rat pups, the dams were removed from the home cage. Immediately before the procedure, the pups were extracted from the home cage and housed temporarily in a separate cage. On PND 9, pups from each litter were assigned to either an experimental group or a control group. In the experimental group (n=21), all vibrissae on both sides of the snout were gently trimmed to the fur level daily from PND 9 to 12. In the control group (n=21), a sham procedure was performed during the same period by gently applying scissors to the vibrissae bases without cutting. During the procedure, pups were restrained by hand to limit movement and keep warmth. Both procedures (vibrissae trimming and sham) lasted 60–120 seconds per pup. After processing, pups were weighed and marked, then returned to the home cage. The dams were reintroduced afterward.

2.3. Open Field Test

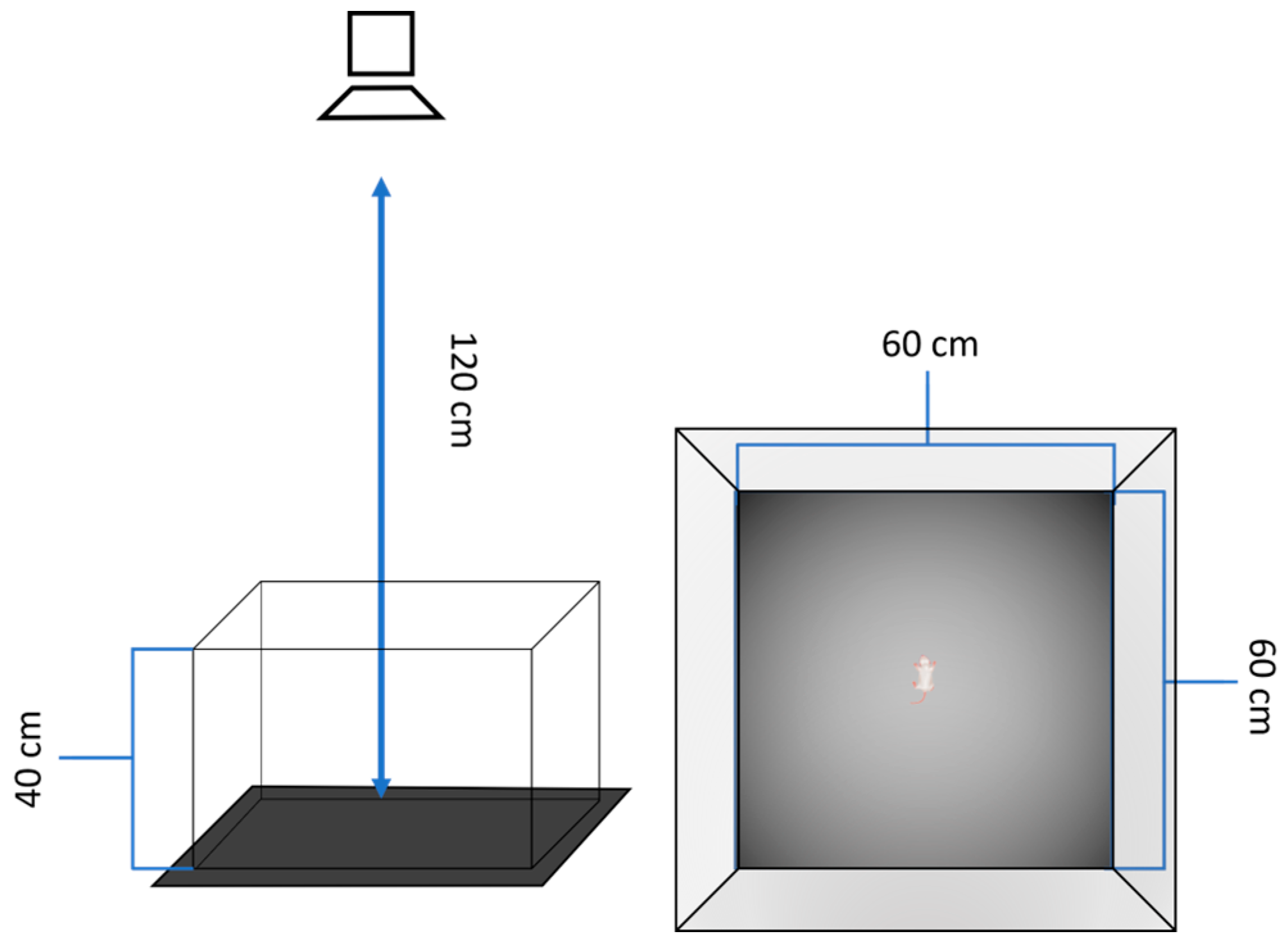

The behavioral testing protocol was performed as described earlier [ DOI: 10.1016/j.beproc.2022.104780] with minor modifications. To minimize stress, dams were separated from their litters only after voluntarily leaving the nest. Pups were then allowed to remain undisturbed in their huddles for 30 minutes to achieve stable baseline behavioral states prior to testing. Individual pups were carefully grasped from the periphery of the huddle and transported to the adjacent testing room. Each trial began immediately upon placement of the pup in the center of the arena. The open field apparatus consisted of two detachable pieces: 60cm*60 cm vertical walls, constructed of plywood and painted with black, and replaceable plywood floor plate, covered by black plastic. The design ensured the absence of possible dust and olfactory cues kept in the corners and gaps. Between trials, the arena was cleaned with wet paper towel, 50% ethanol solution and dried with lint-free wipes to eliminate residual olfactory cues that could influence subsequent testing sessions. A video camera was placed 120cm above. The arena had a lighted center (98-102 Lx) and dimmed corners (32-38Lx). A standard spatial orientation of the landed pup was with its head away from the experimenter, directed to the middle of the opposite wall. At the pup's placement, videotracking started and lasted for 120 seconds. After the test, the pups were sexed, weighed, and numbered; the information is summarized in

Table 1. The eye status was checked individually. This standardized protocol ensured consistent testing conditions while minimizing potential confounds from handling stress or environmental contamination

2.4. Offline Tracking

2.4.1. ToxTrack

Figure 1.

The experimental setup consisted of an open field arena with removable walls constructed from black-painted plywood and a removable plywood floor covered with black plastic. This detachable design prevented the accumulation of potential odor cues in the arena's crevices. A video camera was positioned directly above the center of the arena and connected to a computer in adjacent room.

Figure 1.

The experimental setup consisted of an open field arena with removable walls constructed from black-painted plywood and a removable plywood floor covered with black plastic. This detachable design prevented the accumulation of potential odor cues in the arena's crevices. A video camera was positioned directly above the center of the arena and connected to a computer in adjacent room.

All experimental sessions were video-recorded using a digital camera synchronized with a computer located in a next room. Offline tracking of the animals' movements throughout all trials was conducted utilizing the open-source software ToxTrac (v 25.1.1, Umeå, Sweden [

33]). The tracking process employed Toxld (Ssi.Rep.)'s proprietary identification algorithm, ToxTrac [

34], which calculated the centroid of the white body mass against the black background at 400 ms intervals, thereby digitizing the motion trajectories. Automated measurement included the cumulative distances, and the incidence and duration of freezing episodes.

2.4.2. Trajectory Coating

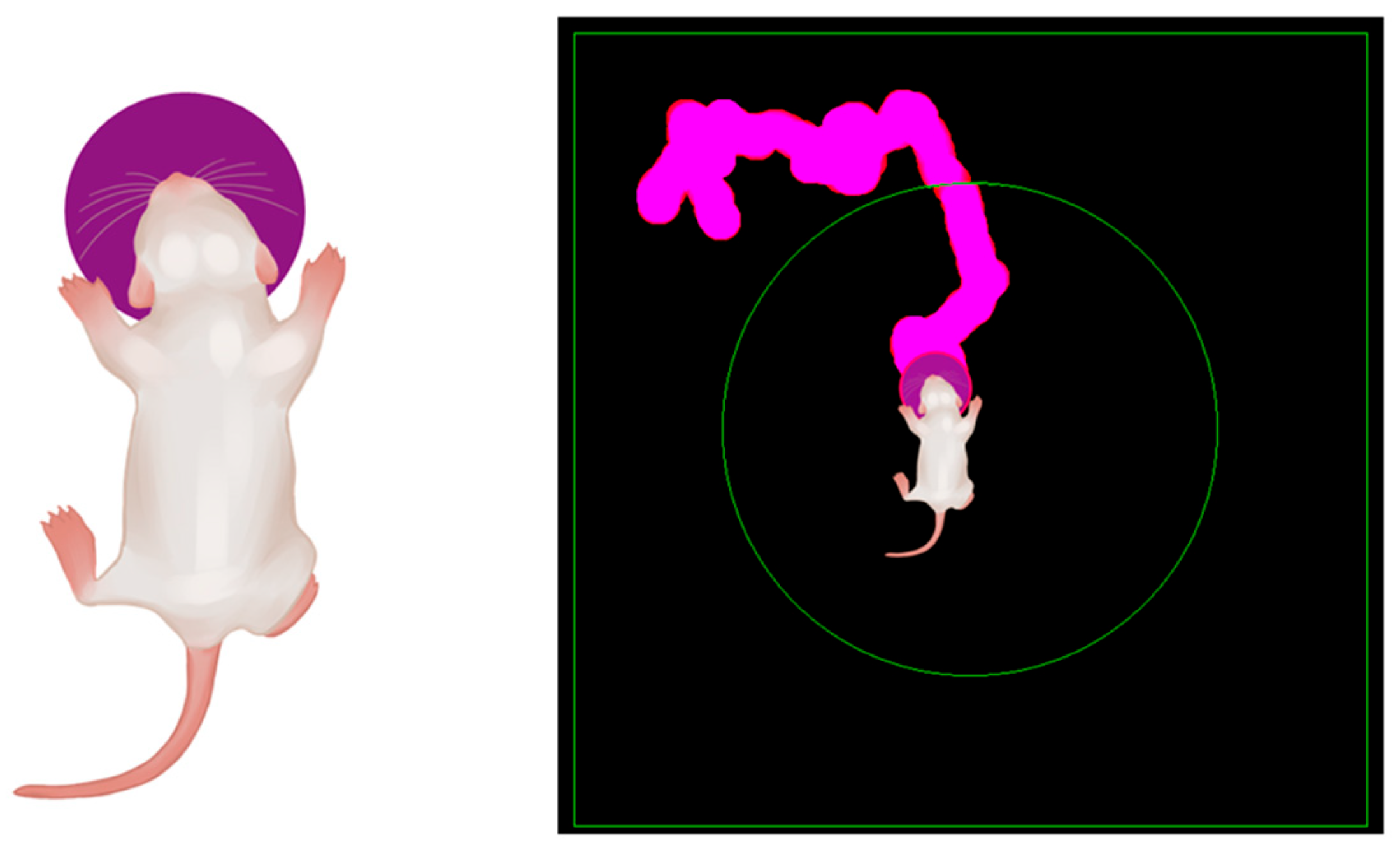

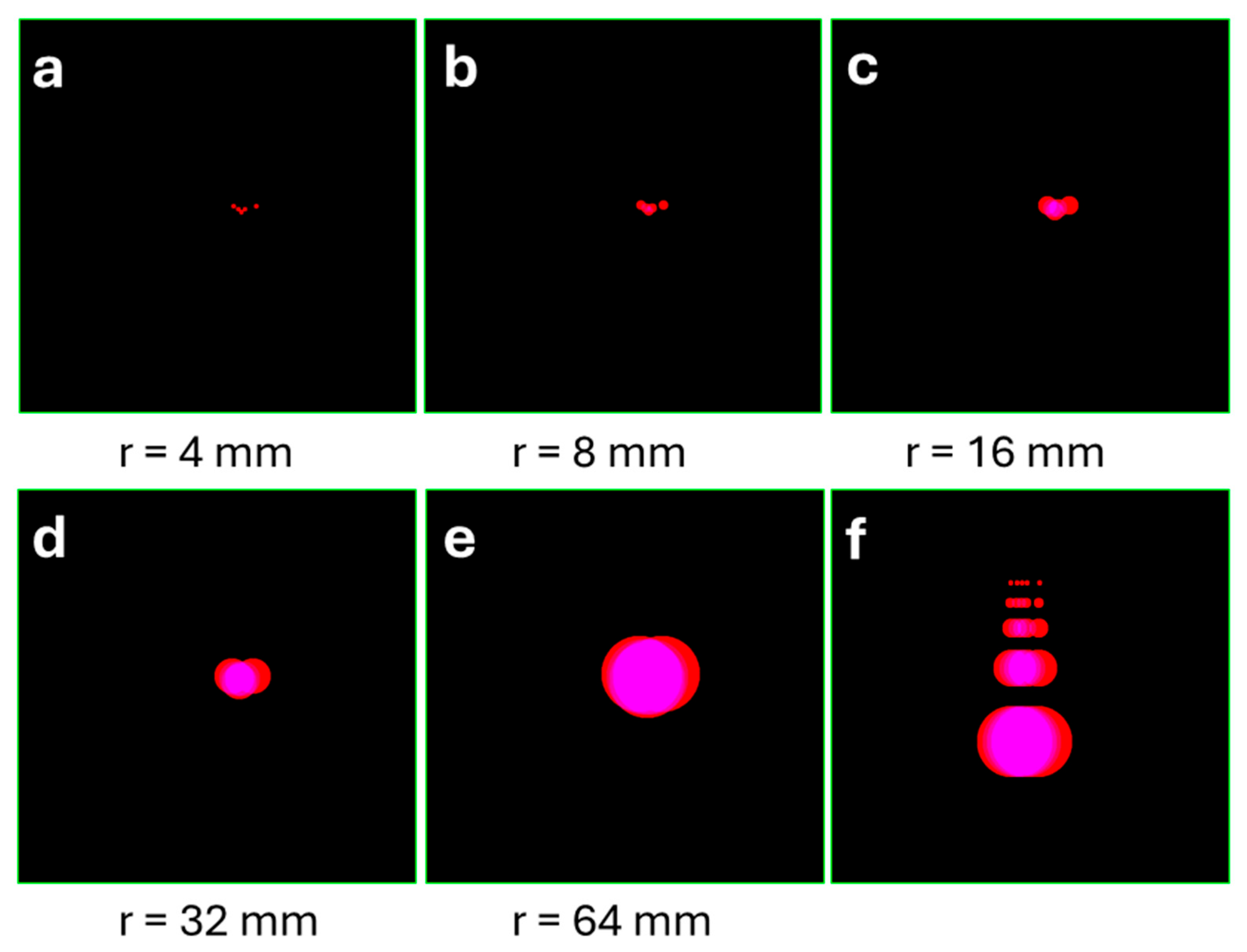

To quantify the area covered by experimental trajectories, while minimizing graphical noise, we developed a simple method of track coating (

Figure 2). Each detected point of the original trajectory was overlaid with a virtual circle (Rv-circle) whose radius matched the mean vibrissal length (Rv) at the given age (PND 13; Rv = 16 mm according to the laboratory data). This coating process smoothed the trajectory with a characteristic spatial scale of Rv (

Figure 2). The total area of all superimposed circles was calculated in pixels. The same procedure was applied to the linearized trajectories, where consecutive points maintained their original spacing (see

Figure 3 a, f), to construct an individual reference for each experimental trajectory.

The degree of trajectorial self-attraction (understood as partial or complete returns to the self-track or its vicinity) was quantified using the track compaction ratio:

Cr = S_coated_linearized_track / S_coated_original_track

To differentiate between behaviors with and without haptic support from the arena walls, we established two virtual zones: (1) a central region (20 cm diameter) and (2) the periphery (remaining arena area). All trajectory coating and subsequent analyses focused exclusively on the central zone to isolate locomotor parameters independent of thigmotactic behavior.

2.4.3. Statistics

The data were analyzed using a general linear model (GLM) ANOVA, with ToxTrac-derived locomotor parameters as dependent variables, group and litter as categorical predictors, and of the session number within a litter as a continuous covariate. It was followed by post-hoc Tukey tests if applicable. Additionally, the Cr values, calculated per pup for a set of coating R (see above), were subjected to the repeated measures ANOVA GLM.

3. Results

3.1. Gross Locomotor Parameters

Inter-litter variability emerged as the primary factor influencing locomotor parameter variation. The experimental manipulation (vibrissectomy) did not significantly alter gross locomotor measures, including total distance traveled, average speed, or freezing duration (

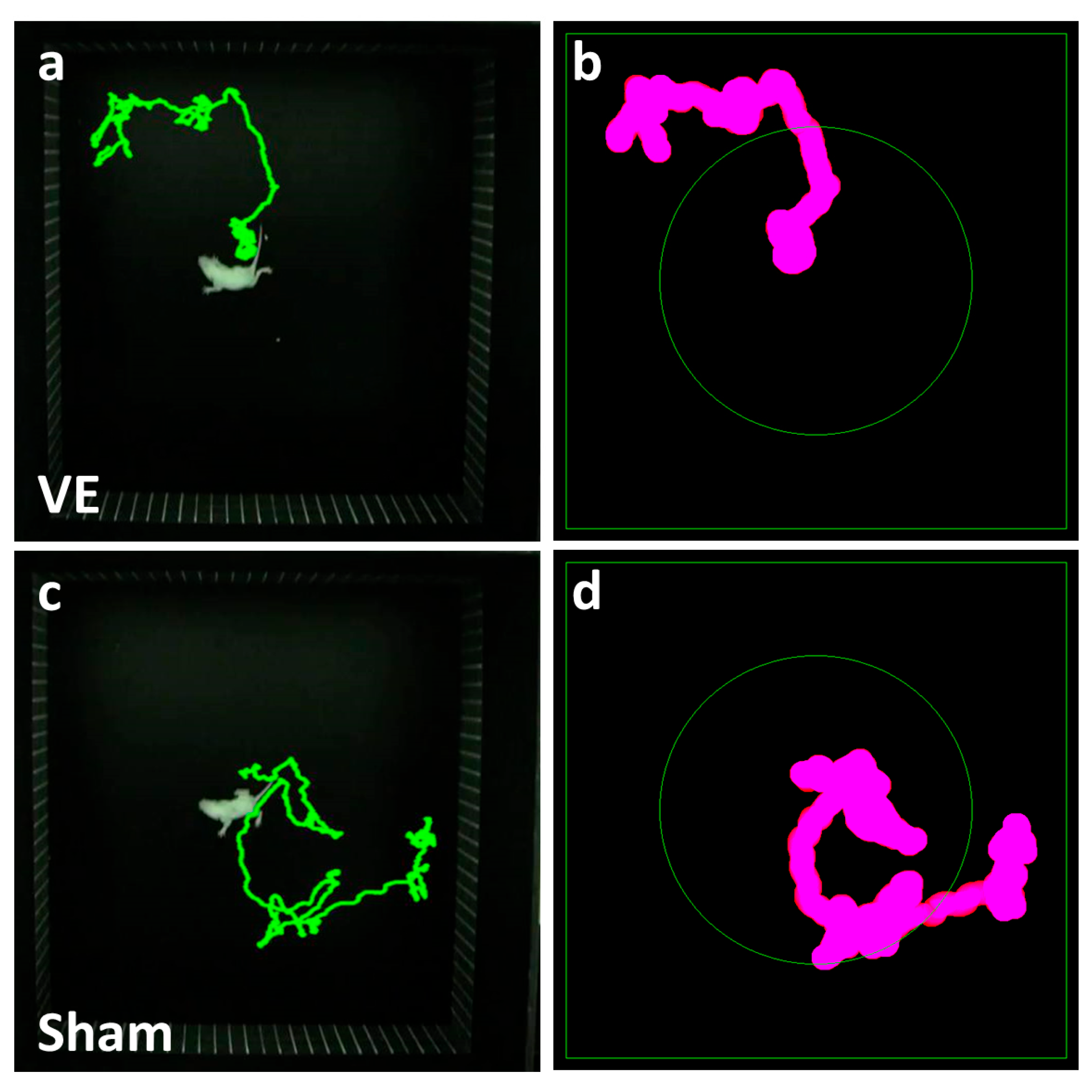

Table 1). However, we observed significant between-group differences in exploration rate, with VE pups demonstrating reduced area coverage (

Table 1). This parameter showed a tendency to interaction effect (p=0.08), reflecting differential VE impact across litters.

The experimental and control groups showed comparable body weights (VE: 22.7 ± 1.5 g vs control: 23.2 ± 2 g; p>0.10), confirming that observed behavioral differences were not attributable to developmental or nutritional factors.

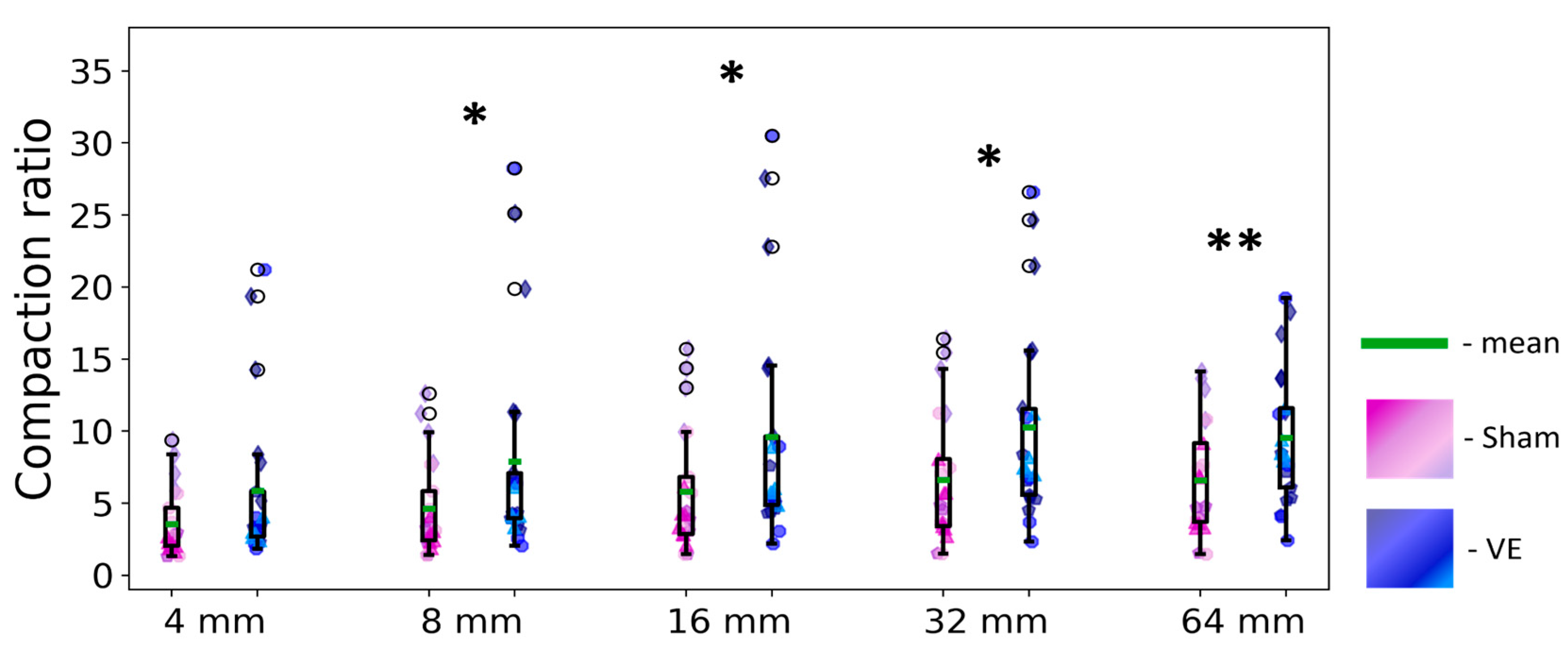

3.2. Compaction of Trajectories Within the Central Zone

The experimental and control pups demonstrated very similar distances travelled within the central zone (VE-group: 1392 ± 690 mm; Sham-group: 1242 ± 723 mm, p>0.05). The trajectorial density in the central zone was additionally studied by the developed “Compaction ratio” approach (see Method Section, 2.4.2.).

The sets of the compaction ratios (Cr) were obtained by comparing the covered surface for the original and linearized trajectories, coated with R-circles of radii Rv, and also for Rv/4, Rv/2, 2Rv, 4Rv (

Table 2,

Figure 3).

The between-litter variability showed the strongest effect on track compaction (

Table 2), suggesting potential sensitivity of these parameters to mother-offspring interactions. Beyond this primary familial difference, the vibrissectomy (VE) effect became apparent starting at R=8mm and remained significant for R=16mm, 32mm, and 64mm, with no significant differences observed between these three largest radii conditions (as confirmed by repeated measures ANOVA: R1, {F(2,66)= 1.03, p=0.35}; R1*VE interaction, {F(2,66)= 1.08, p=0.34}). This indicates that these compaction ratios remained remarkably stable across the 16-64mm scale. The Cr values show that VE pup trajectories were approximately 10 times more compact than their linearized references, compared to about 6 times for control pups. Notably, the vibrissectomy effect was consistent across litters - in each litter, VE pups developed more compact trajectories than their sham-operated counterparts.

4. Discussion

We demonstrate that early vibrissectomy significantly alters spontaneous spatial behavior in previsual rat pups, with tactile-deprived animals exhibiting markedly higher track compaction than controls (

Table 1 and

Table 2,

Figure 5). This finding suggests that loss of vibrissal input causes pups to remain closer to their previous paths, while sham controls distribute their movement more broadly across the environment - a phenomenon not previously reported in the literature.

Notably, vibrissectomy did not affect standard locomotor parameters, mirroring observations in epileptic rat models [

35,

36] and consistent with reports that even spinal cord injury fails to disrupt gross locomotor activity in mouse pups [

37]. This remarkable stability of fundamental motor patterns highlights the need for more sensitive behavioral measures.

Several analytical challenges emerge when studying such movement patterns. The inherent complexity of natural trajectories, compounded by measurement artifacts, can mask underlying locomotor strategies [

28]. Modern tracking systems (e.g., DeepLabCut, ToxTrac) inevitably combine: (1)Whole-body translations, (2) Pause-associated scanning behaviors [

31,

32,

38], Postural microadjustments [

39,

40].

To address these challenges, we adapted our recently reported space potential method [

29], which differentiates pivoting/scanning from directed movement, to create a simplified compaction metric (Cr). This ratio compares R-coated original trajectories to their individual linearized references, which accounting for natural speed. Our prior work established that previsual pups typically show imprecise path retracing, detectable through velocity autocorrelation analysis [

29].

The Cr values showed surprising consistency across spatial scales (16-64mm), with VE pups maintaining ratios near 10 versus approximately 6 for controls. This scale-invariant effect, persisting well beyond vibrissal length, implies contributions from additional factors. Presumably, proprioceptive mechanisms related to body size (inter-paw distances: 4-8 cm at this age) may be involved [

41,

42,

43], though plantar tactile contributions remain poorly understood [

44]. Local plantar anesthesia studies could help in future studies.

Alternative interpretations also warrant consideration. Increased compaction in VE pups may reflect not just sensory impairment but also heightened maternal dependence [

18], potentially including retrieval anticipation [

45]. Thus, while our data clearly establish enhanced path compaction following vibrissectomy (

Table 2,

Figure 5), the precise mechanistic balance between sensory and affective factors requires further investigation.

These results underscore the essential role of somatosensory input in previsual spatial behavior, with potential relevance for neurodevelopmental disorders featuring sensory integration deficits. The compaction ratio (Cr) proves particularly valuable for detecting moderate yet consistent behavioral consequences of vibrissal deprivation.

5. Conclusions

While sensory-deprived animals maintain unchanged gross locomotor parameters, they exhibit significantly increased trajectorial compaction. The demonstrated sensitivity of the compaction ratio to whisker removal establishes this measure as an easy and robust metric for evaluating vibrotactile function in behaving rodent pups. This approach shows particular promise for translational applications in neurodevelopmental disorder research, where quantitative behavioral markers are urgently needed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: The gross locomotor parameters in individual pups. Table 2S. The compaction ratios in individual pups. Table 3S: The script details. Figures S1-S8: origimal trajetories of VE and sham pups of each litter.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M; software, P.A.; validation, I.M and A.R; investigation, E.S; data curation, P.A. and A.R; writing— I.M. and M.O.; visualization, M.O, A.R and P.A.; supervision, I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the reviewer vouchers to IM.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The IHNA EC approved the given protocol (the Statement of Opinion N4, 29.05.24). The experimental protocol also agrees with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All efforts were made to minimize animal discomfort, and the number of animals used.

Data Availability Statement

All the original trajectories are published as Supplementary materials to this manuscript

Acknowledgments

The authors are extremely grateful to Prof. V.V. Raevsky and Dr. O.A. Chichigina for valuable scientific discussion. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors utilized DeepSeek's AI-assisted language processing solely for partial text refinement. All AI-generated content was rigorously reviewed, modified as needed, and ultimately approved by the authors, who assume complete responsibility for the final manuscript's content and scientific integrity.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Cr |

compaction ratio |

| PND |

postnatal day |

| mm |

millimeter |

| R |

radius |

| s |

second |

| VE |

vibrissectomy |

References

- Morrison, A. Changing Concepts of the Nervous System: Proceedings of the First Institute of Neurological Sciences Symposium in Neurobiology; Elsevier, 2012; ISBN 978-0-323-14224-3.

- Solomon, P.; Leiderman, P.H.; Mendelson, J.; Wexler, D. Sensory Deprivation; a Review. Am J Psychiatry 1957, 114, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubzansky, P.E.; Leiderman, P.H. Sensory Deprivation: An Overview. In Sensory Deprivation; Harvard University Press, 2013; pp. 221–238 ISBN 978-0-674-86481-8.

- Caras, M.L.; Sanes, D.H. Sustained Perceptual Deficits from Transient Sensory Deprivation. J Neurosci 2015, 35, 10831–10842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubel, D.H.; Wiesel, T.N. Receptive Fields, Binocular Interaction and Functional Architecture in the Cat’s Visual Cortex. J Physiol 1962, 160, 106–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.-J.; Chen, W.-J.; Chuang, Y.-W.; Wang, Y.-C. Neonatal Whisker Trimming Causes Long-Lasting Changes in Structure and Function of the Somatosensory System. Experimental Neurology 2009, 219, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, K. A Critical Period for Experience-Dependent Synaptic Plasticity in Rat Barrel Cortex. J. Neurosci. 1992, 12, 1826–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzurumlu, R.S.; Kind, P.C. Neural Activity: Sculptor of ‘Barrels’ in the Neocortex. Trends in Neurosciences 2001, 24, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, K.F.; Killackey, H.P. Terminal Arbors of Axons Projecting to the Somatosensory Cortex of the Adult Rat. I. The Normal Morphology of Specific Thalamocortical Afferents. J Neurosci 1987, 7, 3529–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolsey, T.A.; Van der Loos, H. The Structural Organization of Layer IV in the Somatosensory Region (S I) of Mouse Cerebral Cortex: The Description of a Cortical Field Composed of Discrete Cytoarchitectonic Units. Brain Research 1970, 17, 205–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassihi, A.; Zuo, Y.; Diamond, M.E. Making Sense of Sensory Evidence in the Rat Whisker System. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2020, 60, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R.M.; Landers, M.S.; Flemming, J.; Vaught, C.; Young, T.A.; Jonathan Polan, H. Characterizing the Functional Significance of the Neonatal Rat Vibrissae Prior to the Onset of Whisking. Somatosensory & Motor Research 2003, 20, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.A.; Mitchinson, B.; Prescott, T.J. The Development of Whisker Control in Rats in Relation to Locomotion. Developmental Psychobiology 2012, 54, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, D.J.; Land, P.W. Early Experience of Tactile Stimulation Influences Organization of Somatic Sensory Cortex. Nature 1987, 326, 694–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoykhet, M.; Land, P.W.; Simons, D.J. Whisker Trimming Begun at Birth or on Postnatal Day 12 Affects Excitatory and Inhibitory Receptive Fields of Layer IV Barrel Neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology 2005, 94, 3987–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, A.; Carlson, G.C. Neonatal Whisker Clipping Alters Intracortical, but Not Thalamocortical Projections, in Rat Barrel Cortex. J Comp Neurol 1999, 412, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, S.; Brigham, L.; Krieger, P. Sensory Deprivation during Early Development Causes an Increased Exploratory Behavior in a Whisker-Dependent Decision Task. Brain Behav 2013, 3, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, K.; Tsvetaeva, D.; Sitnikova, E. Neonatal Whisker Trimming in WAG/Rij Rat Pups Causes Developmental Delay, Encourages Maternal Care and Affects Exploratory Activity in Adulthood. Brain Research Bulletin 2018, 140, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishelova, A.Yu. Effect of Whisker Removal on Defensive Behavior in Rats during Early Ontogenesis. Neurosci Behav Physiol 2006, 36, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvell, G.; Simons, D. Abnormal Tactile Experience Early in Life Disrupts Active Touch. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 2750–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilam, D.; Golani, I. The Ontogeny of Exploratory Behavior in the House Rat ( Rattus Rattus ): The Mobility Gradient. Developmental Psychobiology 1988, 21, 679–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, M.J.; Pierre, P.J. Development of Exploration and Investigation in the Norway Rat ( Rattus Norvegicus ). The Journal of General Psychology 1998, 125, 270–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarac, F.; Brocard, F.; Vinay, L. The Maturation of Locomotor Networks. In Progress in Brain Research; Brain Mechanisms for the Integration of Posture and Movement; Elsevier, 2004; Vol. 143, pp. 57–66.

- Jamon, M.; Clarac, F. Early Walking in the Neonatal Rat: A Kinematic Study. Behavioral Neuroscience 1998, 112, 1218–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swann, H.E.; Brumley, M.R. Locomotion and Posture Development in Immature Male and Female Rats (Rattus Norvegicus): Comparison of Sensory-Enriched versus Sensory-Deprived Testing Environments. Journal of Comparative Psychology 2019, 133, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchin, P. Fractal Analyses of Animal Movement: A Critique. Ecology 1996, 77, 2086–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartumeus, F.; Levin, S.A. Fractal Reorientation Clocks: Linking Animal Behavior to Statistical Patterns of Search. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 19072–19077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benhamou, S. How to Reliably Estimate the Tortuosity of an Animal’s Path:: Straightness, Sinuosity, or Fractal Dimension? Journal of Theoretical Biology 2004, 229, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midzyanovskaya, Inna S.; Strelkov, Vasily V. Measuring Locomotor Strategies of Freely Moving Previsual Rat Pups. Behavioural Processes 2022, 203, 104780. [CrossRef]

- Golani, I. The Developmental Dynamics of Behavioral Growth Processes in Rodent Egocentric and Allocentric Space. Behavioural Brain Research 2012, 231, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golani, I.; Benjamini, Y.; Eilam, D. Stopping Behavior: Constraints on Exploration in Rats (Rattus Norvegicus). Behavioural Brain Research 1993, 53, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drai, D.; Benjamini, Y.; Golani, I. Statistical Discrimination of Natural Modes of Motion in Rat Exploratory Behavior. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2000, 96, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, A.; Zhang, H.; Klaminder, J.; Brodin, T.; Andersson, P.L.; Andersson, M. ToxTrac : A Fast and Robust Software for Tracking Organisms. Methods Ecol Evol 2018, 9, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.; Zhang, H.; Klaminder, J.; Brodin, T.; Andersson, M. ToxId: An Efficient Algorithm to Solve Occlusions When Tracking Multiple Animals. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 14774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, K.; Sitnikova, E. Developmental Milestones and Behavior of Infant Rats: The Role of Sensory Input from Whiskers. Behavioural Brain Research 2019, 374, 112143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishelova, A.Yu.; Raevskii, V.V. Effects of Vibrissectomy during Early Postnatal Ontogenesis in Rat Pups on Behavioral Development. Neurosci Behav Physi 2010, 40, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martes, A.C.; Bozeman, A.L.; Doell, J.; Weedn, K.; Collins, N.; Campbell, T.; Roth, T.L.; Brumley, M.R. Developmental Changes in Locomotion and Sensorimotor Reflexes Following Spinal Cord Transection. Dev Psychobiol 2024, 66, e22558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drai, D.; Kafkafi, N.; Benjamini, Y.; Elmer, G.; Golani, I. Rats and Mice Share Common Ethologically Relevant Parameters of Exploratory Behavior. Behavioural Brain Research 2001, 125, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, W.; Masip Rodo, D. Computer Methods for Automatic Locomotion and Gesture Tracking in Mice and Small Animals for Neuroscience Applications: A Survey. Sensors 2019, 19, 3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.M.; Martin, M.E.; Shepherd, G.M.G. Manipulation-Specific Cortical Activity as Mice Handle Food. Current Biology 2022, 32, 4842–4853.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, J.; Sudarshan, K. Postnatal Development of Locomotion in the Laboratory Rat. Animal Behaviour 1975, 23, 896–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarac, F.; Vinay, L.; Cazalets, J.-R.; Fady, J.-C.; Jamon, M. Role of Gravity in the Development of Posture and Locomotion in the Neonatal Rat. Brain Research Reviews 1998, 28, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Neifert, C.; Rosete, A.; Albeely, A.M.; Yang, Y.; Pratelli, M.; Brecht, M.; Clemens, A.M. Tactile Mechanisms and Afferents Underlying the Rat Pup Transport Response. Current Biology 2024, 34, 5595–5601.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varejão, A.S.P.; Filipe, V.M. Contribution of Cutaneous Inputs from the Hindpaw to the Control of Locomotion in Rats. Behavioural Brain Research 2007, 176, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Nungaray, K.; Garza, M.; Raska, J.; Kercher, M.; Lutterschmidt, W.I. Sit down and Stay Here! Transport Response Elicitation Modulates Subsequent Activity in Rat Pups. Behavioural Processes 2008, 77, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).