1. Introduction

The objective is to show that the known features of global average sea-level can be accounted for by eleven periodic functions associated with planetary orbits – the hypothesis. The method will be to show that proxy data for relative sea-level during the last glacial cycle and a modern sea-level reconstruction are fit accurately using these periodic functions. The modern sea-level reconstruction has errors measured in millimeters while the Proxy data errors are measured in tens of meters.

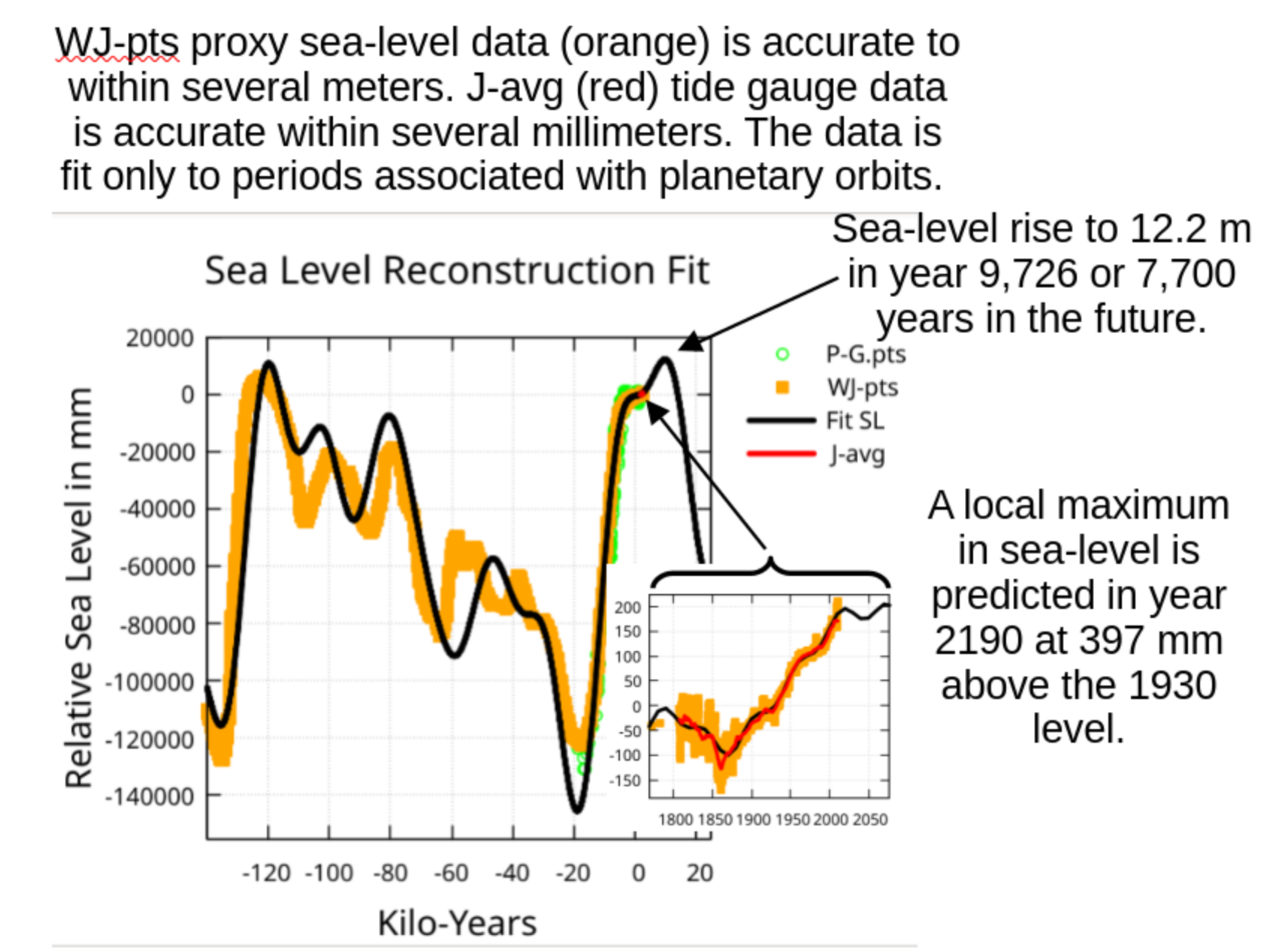

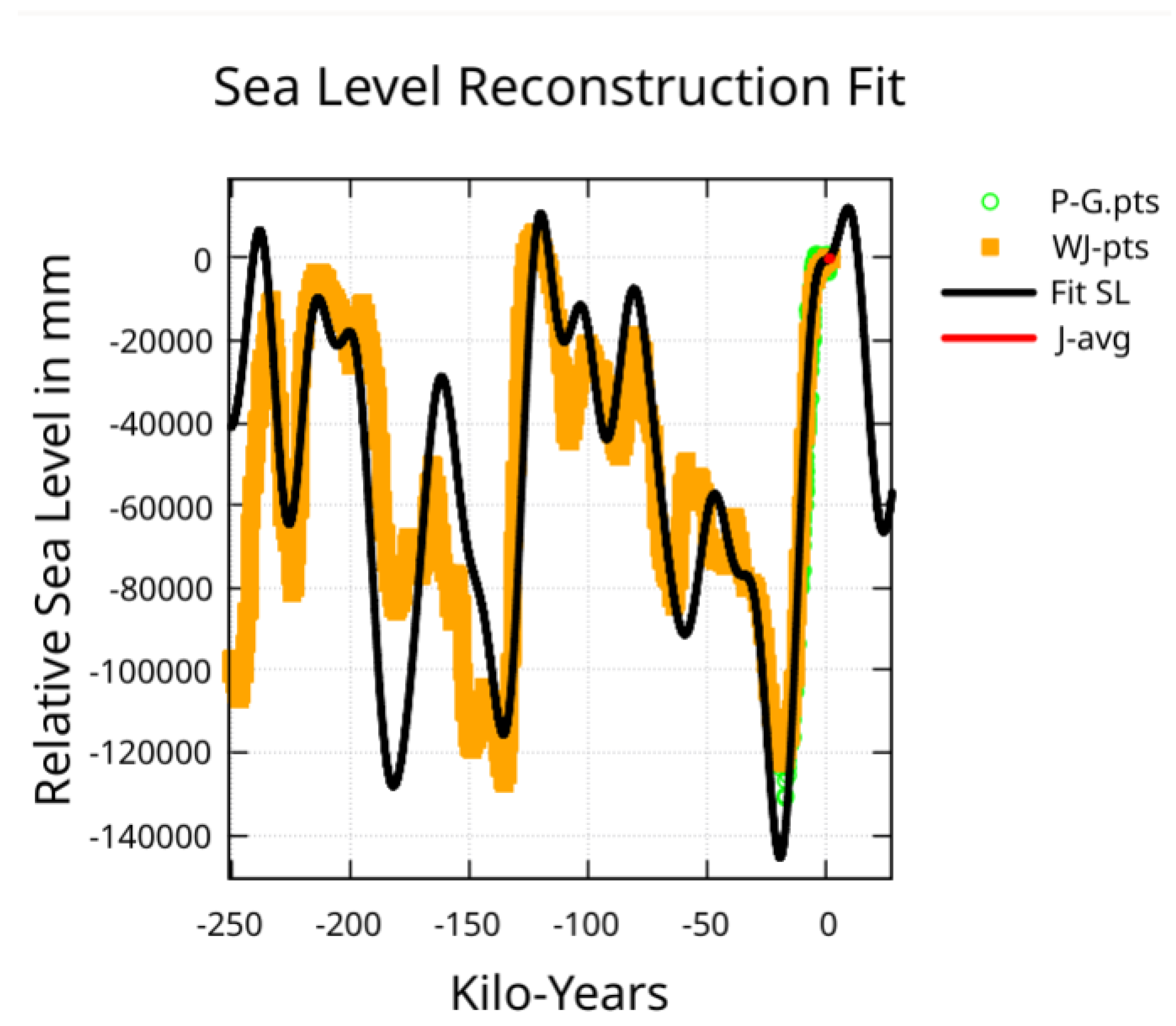

Figure 1 gives an early look at the fit.

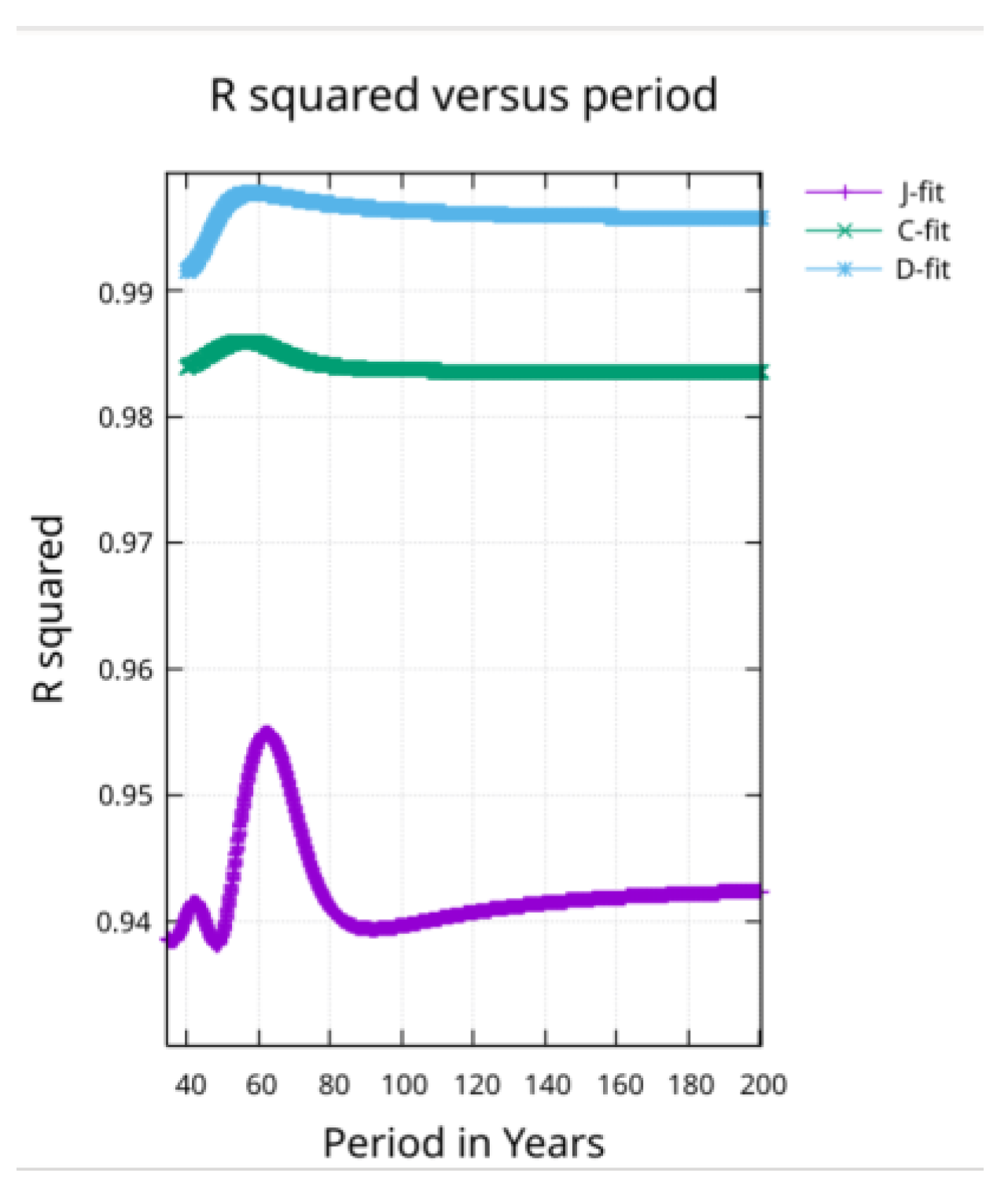

This analysis begins by fitting three modern global average sea level (GASL) reconstructions, J-fit, C-fit, and D-fit, to establish that there exists an approximate sixty-year periodic variation in all three, see

Figure 2, which corresponds to one of the periods associated with planetary motion. For these modern reconstructions, spanning 200 years or less, the initial background change in GASL will be represented by a cubic function of time. Later, when fitting 250,000 years of information this background variation will be determined by longer period functions associated with planetary orbits rather than polynomials.

An approximate sixty-year periodic variation in sea- level has been suggested by several authors, Jevrejeva [

11], Chambers [

3], Kalenda [

14]. Recent information on sea-level is available from satellite measurements. However, early sea-level information (from 1800 to before 1993) comes from tide gauge measurements.

Global average sea-level from tide gauges is a difficult quantity to measure since it is influenced by multiple factors. Some of these factors actually change sea-level itself while others change the elevation of measurement stations.

Proxy information has been used to approximate sea-level back through the last glacial period [

8] and beyond [

21]. This data will be used to determine the contribution of long orbital periods.

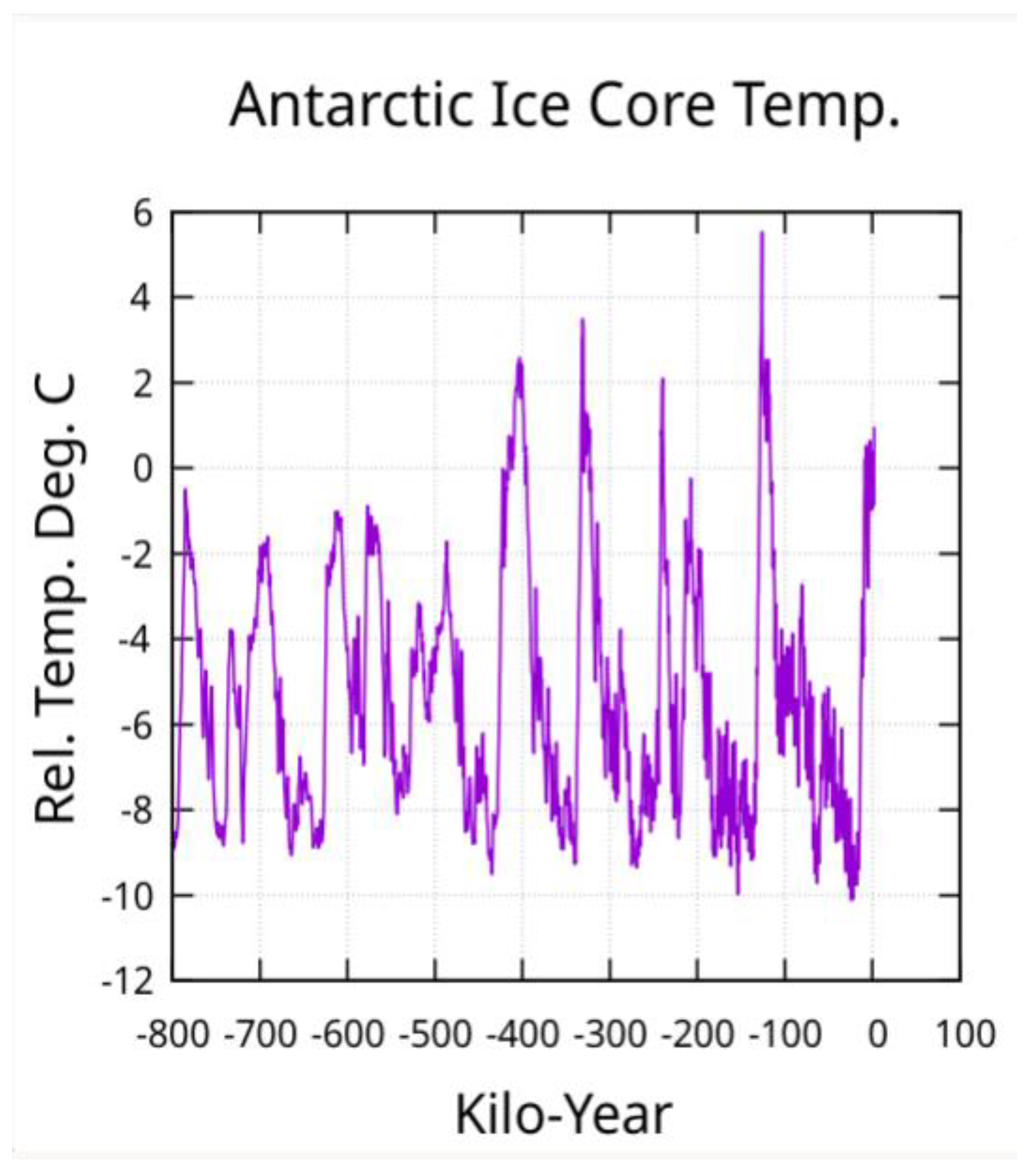

A long time is required for ice to accumulate on the Antarctic land mass and Greenland and a long time is required to melt such accumulations of ice. While sea-level is closely tied to climate temperature through ice accumulation/loss, there is a damping effect that will filter out transient events. The Younger Dryas cold period is a good example of a major transient event in temperature that is difficult to detect in the proxy sea-level data. So sea-level may be a preferred physical quantity for detection of cyclical properties of climate temperature.

Factors that can actually change sea-level are: (1) thermal expansion or contraction of ocean water due to temperature change [

9], (2) melting and run off or accumulation of ice and snow over land masses, [

13], (3) plate tectonics that may change the volume of the basin, [

6], (4) sediment displacing basin volume, (5) fresh water dams that retain water on land rather than allowing it to flow into oceans, [

7], (6) draining of subsurface aquifers with some of this water ultimately flowing into ocean basins.

Factors that change the elevation of measurement stations are: (1) subsidence of land from groundwater extraction, (2) slow rebound of the land from the weight of melted glaciers called glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA), (3) vertical surface change due to earthquakes.

Other problems with measurements are associated with tides causing variations in local sea-level and other gravitational effects together with the Coriolis force associated with the Earth’s rotation and ocean current.

Three reconstructions of global average sea-level that attempt to account for the above factors are considered: Jevrejeva et al. [

11], Church and White [

4], and Dangendorf et al. [

5]. These will be called

modern reconstructions of sea-level.

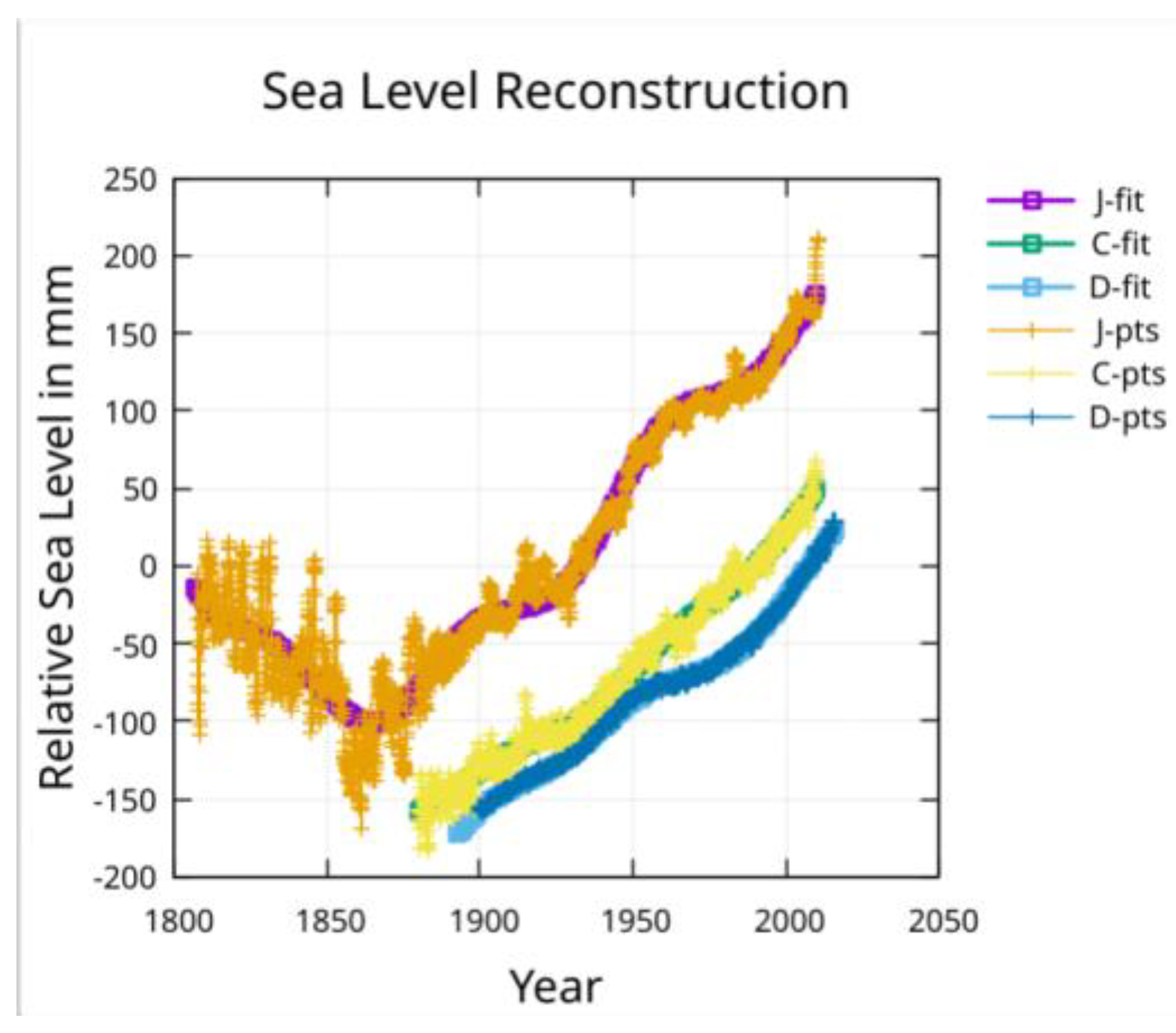

For brevity the Jevrejeva et al. reconstruction data points will be referred to as the J-pts and a fit to the reconstruction will be referred to as a J-fit. Similarly, the Church and White reconstruction data points will be referred to as the C-pts while a fit to the reconstruction will be referred to as a C-fit. The Dangendorf et al. reconstruction data points will be referred to as the D-pts while a fit to the reconstruction will be referred to as a D-fit.

In the following text the term sea-level will refer to Global Average Sea-Level. Whenever an elevation is given, it is with respect to the year 1930.

3. Results

The 60 year period:

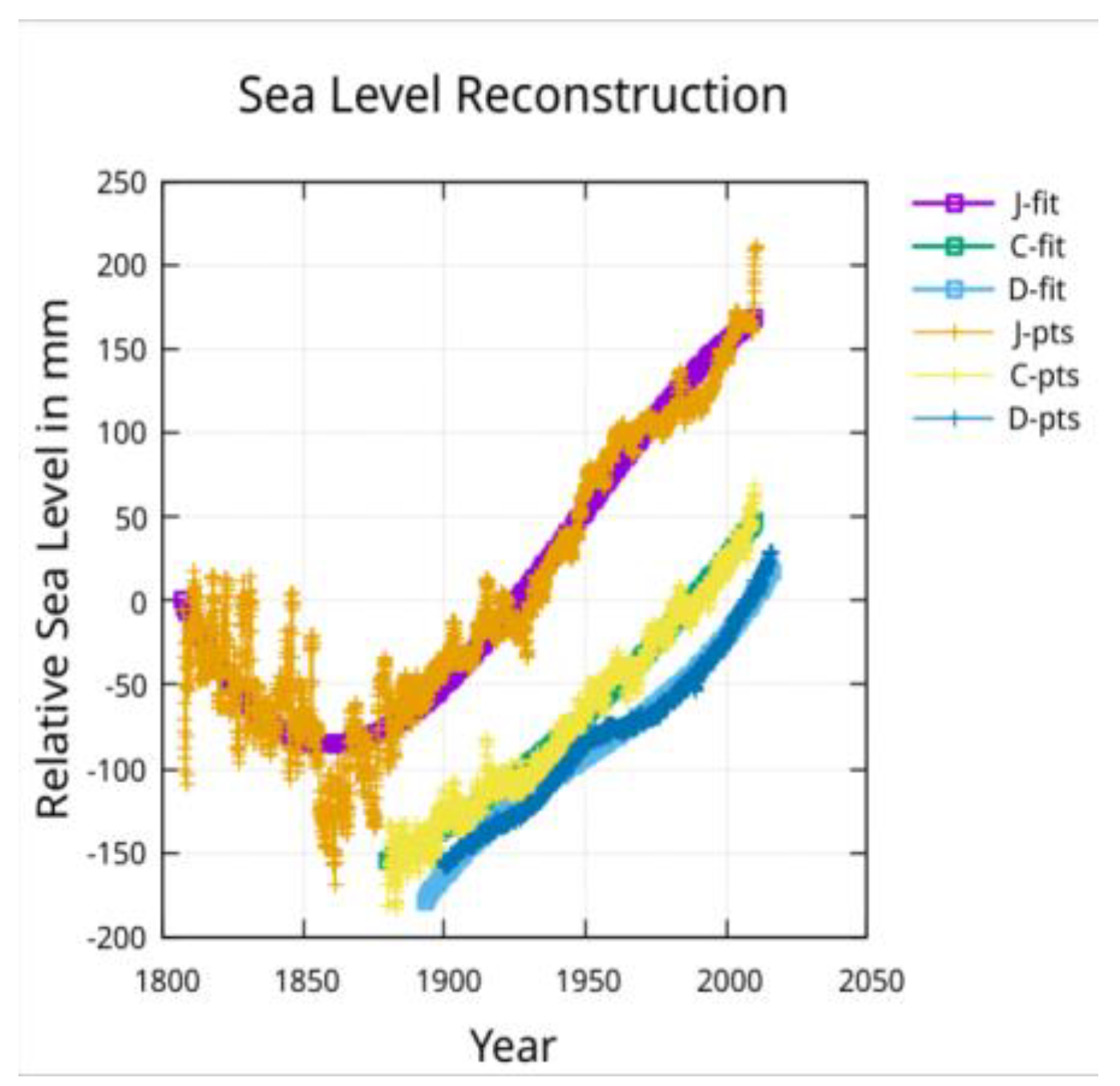

The data for each modern reconstruction is fit with a cubic function of time and a single period (sine and cosine having that period). The result is shown in

Figure 4.

The periods found to work best for each reconstruction were shown in

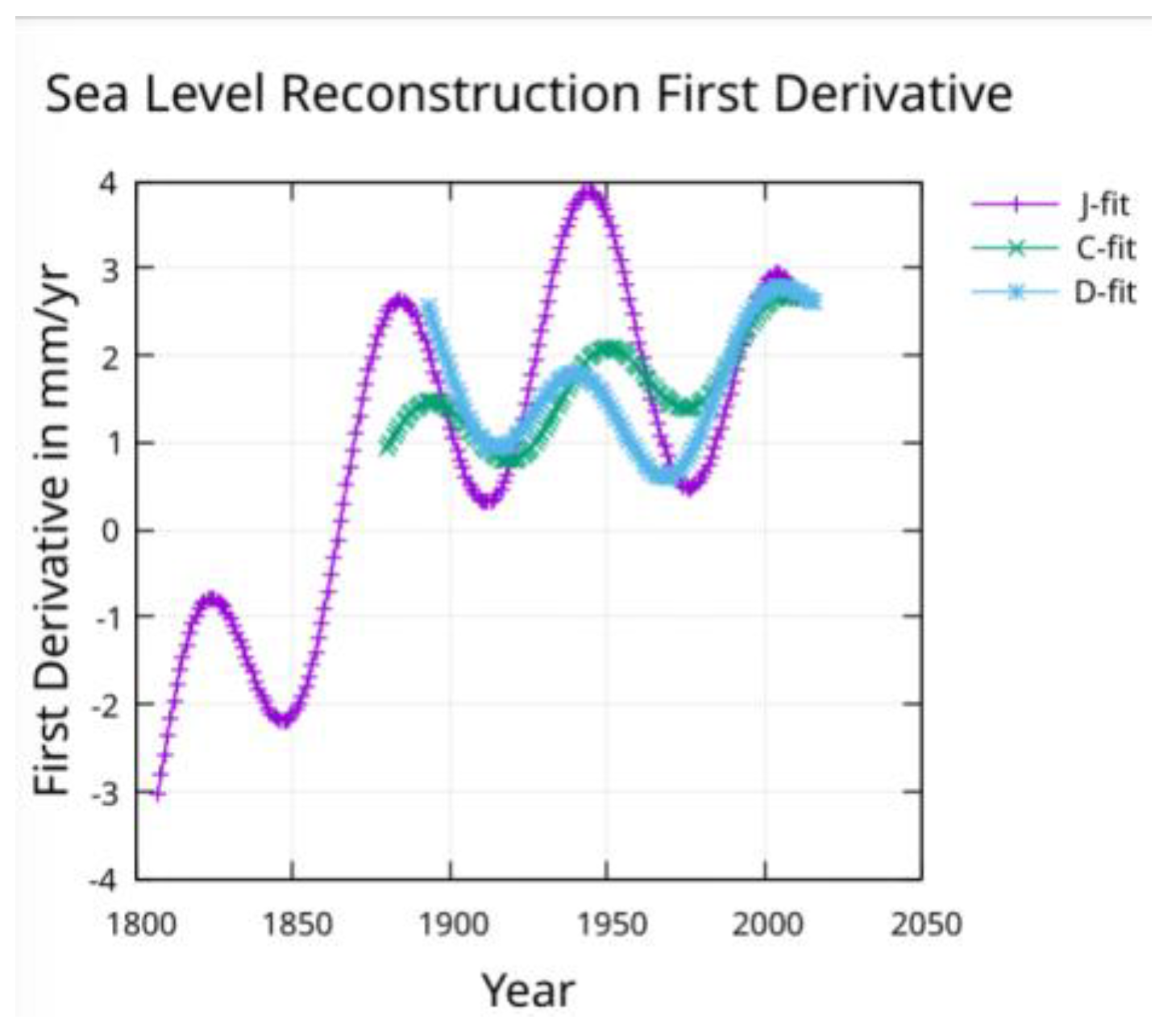

Figure 2. It is obvious in

Figure 4 that the Dangendorf et al. reconstruction points show the least (almost no) scatter while the Jevrejeva et al. reconstruction points show the most scatter, which increases as the reconstructed points move further into the past.

In addition, we see that only the Jevrejeva et al. reconstruction extends back in time to the last few decades of the Little Ice Age.

As shown in

Figure 2, a scan through fits using different periods show a peak in R squared at periods near 60 years. The peak is most obvious for the J-fit and least obvious for the D-fit.

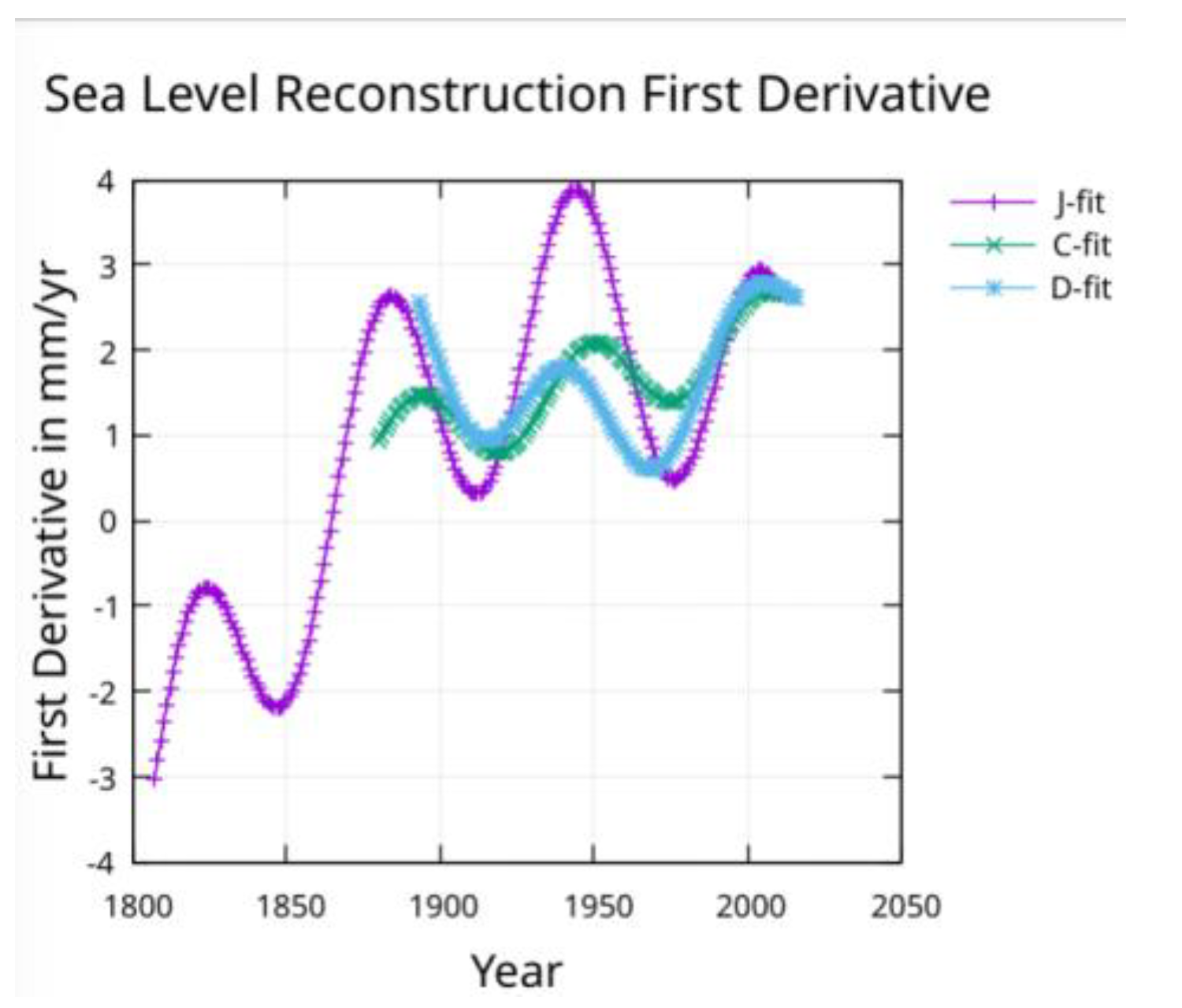

Derivatives of the fit functions can now be used to find the slope and acceleration.

The approximate 60-year period stands out in the slope of sea-level rise

Figure 5, and the acceleration,

Figure 6.

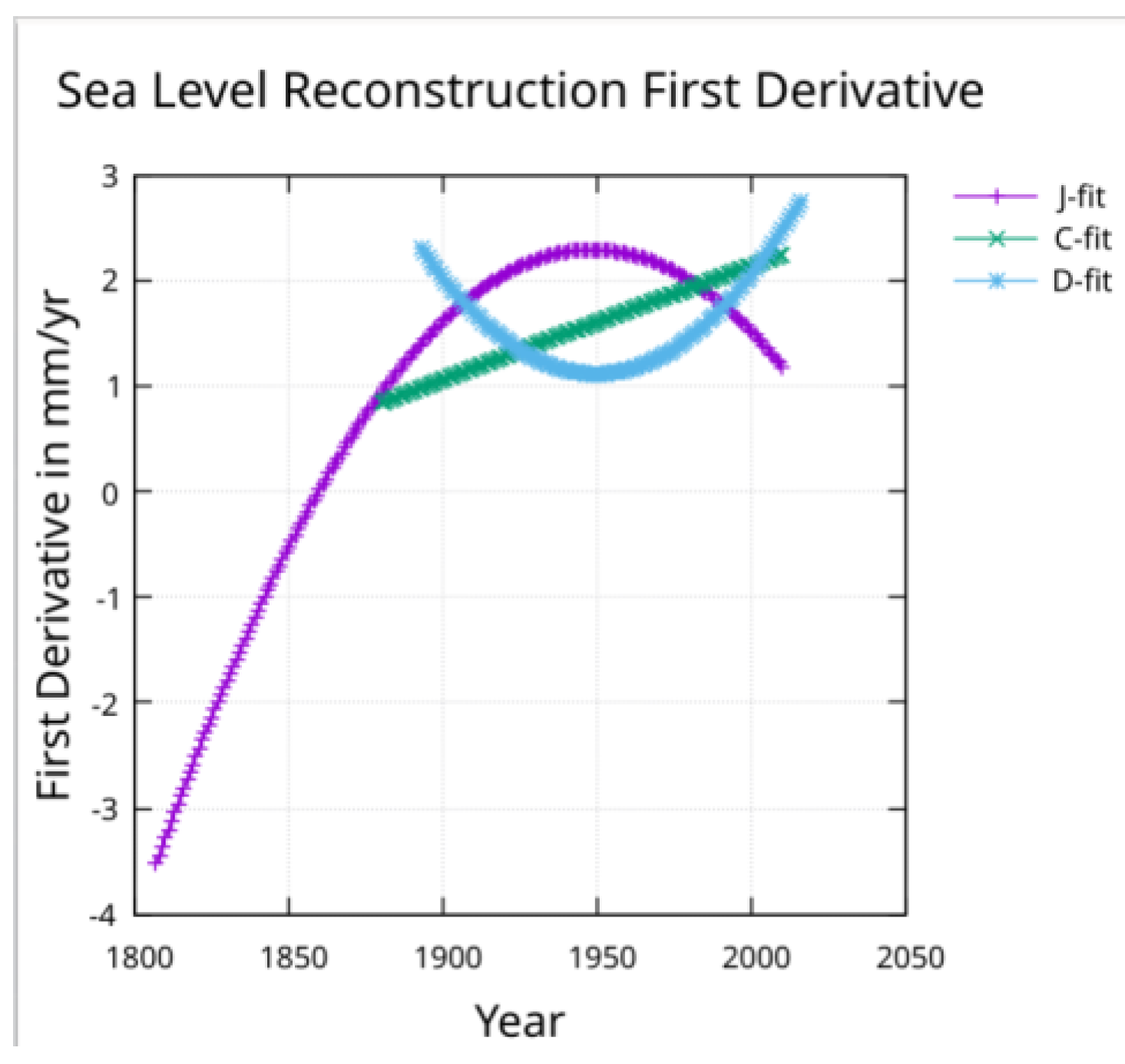

The 60-year periodic function can be removed from the fit,

Figure 7, to view the underlying un-modulated slope,

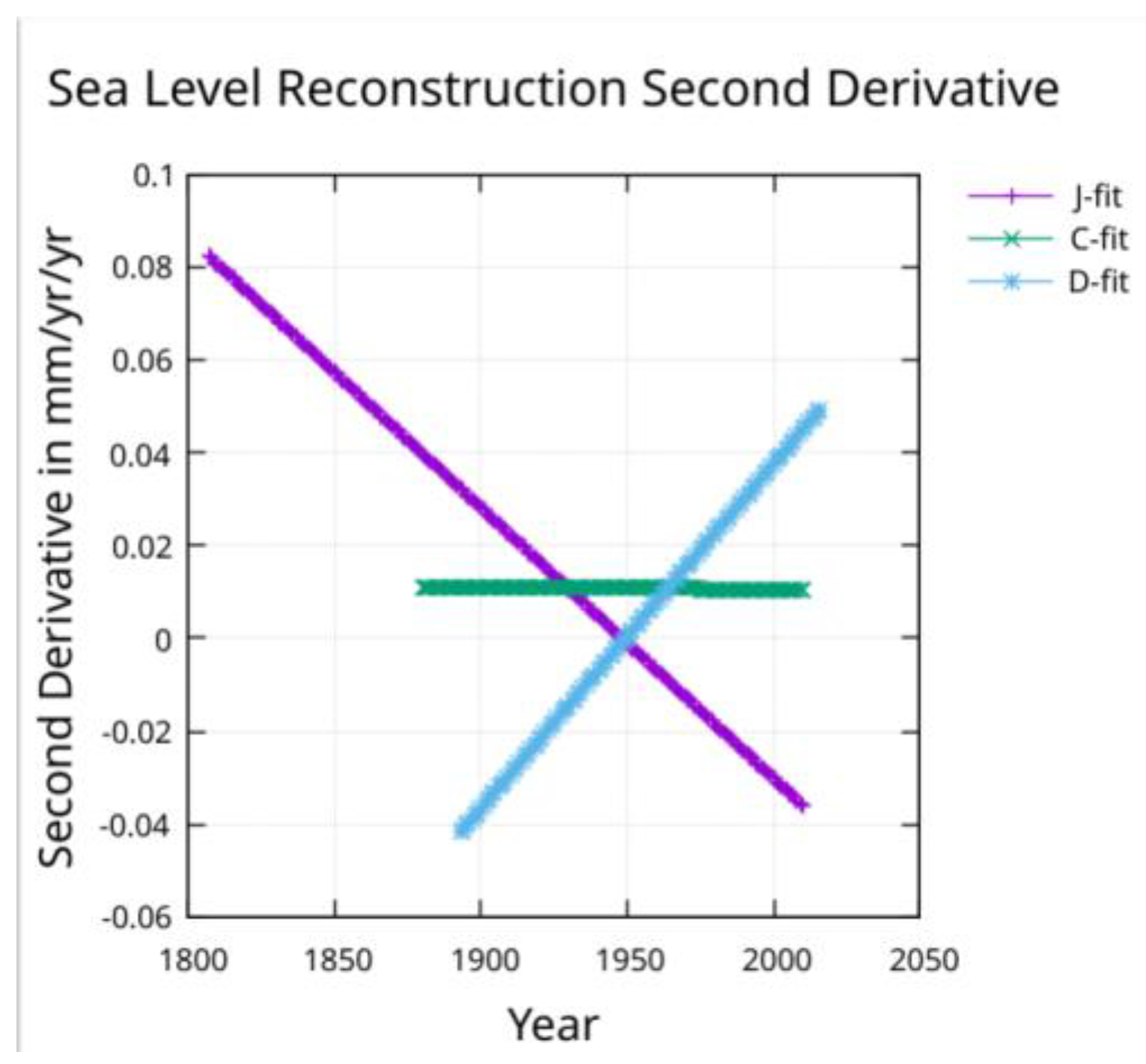

Figure 8, and acceleration

Figure 9.

The underlying slope from 1900 to 2010 is roughly 2 mm/yr for all three reconstructions in

Figure 8.

The acceleration measured by Church and White is constant and agrees with the acceleration shown in

Figure 8 for the C-fit. The acceleration found by Dangendorf et al. is 0.09 mm/yr/yr from a quadratic fit which will only provide a constant value.

Figure 9 shows an acceleration that is negative (about -0.04) in 1900 but increasing and reaching zero in about 1950 and continuing to increase to about 0.05 by 2010. The acceleration for the fit to the Jevrejeva et al. reconstruction after removing the 60-year modulation, is decreasing to zero around 1950 and continuing to decrease to about -0.035 mm/yr/yr by 2010. The acceleration at the midpoint of the J-fit line in

Figure 9 is about 0.02 mm/yr/yr which agrees with the acceleration found with a quadratic fit by Jevrejeva et al. [

11] .

Why should there be a 60-year periodic oscillation of GASL? Scafetta [

18] and Kalenda et. al. [

14] identified an approximately 60-year oscillation in temperature associated with astronomical oscillations. Stefani et al. [

19] have identified gravitational beat periods associated with planetary motion. These beat periods may play an important role in solar activity. To quote Stefani et al.: “In view of the growing evidence for a link between solar activity and climate-related observations, …, we consider a deepened understanding of any such kind of (quasi-) deterministic triggers of the solar dynamo as worthwhile and timely. “

The beat periods identified are shown in Stefani et al. [

18]

Figure 10 and discussed in the surrounding text. These periods are

: 579-yr, 193-yr, 144-yr, 89-yr, and

58-yr. Obviously the 58-year period matches well with the periods identified in

Figure 2 for the three GASL reconstructions.

The gravitational beat periods are associated with the planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. These planets are generally ten or more times as far from the Sun as the Earth. As a result, the tidal forces associated with these beat periods would act on the Earth as well as on the Sun. There are therefore two possible ways these beat periods might affect sea-level. The first is associated with inducing periodic variations in solar activity/position (solar tides, or distance from Earth) thereby changing Earth’s temperature. The second is a possible periodic gravitational distortion of Earth’s oceans. So, the 58-year (57.8 year) Saturn-Neptune gravitational beat is an explanation for the near 60-year oscillation apparent in GASL.

Hypothesis accounting for 250,000 years of global average sea-level:

Fernandez-Palacios et al., [

8] provide an estimate of sea-level (their

Figure 1) spanning dates -117,460 to +1732. Digitizing (WebPlotDigitizer,

https://apps.automeris.io/wpd4/ ) and interpolating to a 10-year spacing, this data is referred to as the F-P-pts. This data is easily fit using orbital periods but it was not used here because only one cycle of the longest period is spanned by this data. This fit will be briefly discussed later.

Waelbroeck et al. [

21] provide a plot of relative sea-level for the last 430,000 years that never exceeds 10 meters above the 1930 level. Only the data for the last 250,000 years was used assuming the curve representing earlier times to be less accurate and also more strongly subject to the long-term base temperature variation change discussed above. This provides two periods of data for the longest orbital period in the fit.

Approximately evenly spaced points were digitized from that plot and then linearly interpolated to a 10-year spacing. This smooth line representing this data will be essentially orthogonal to the short period functions and will not influence their fit coefficients. The normalized covariance matrix confirms this assertion. If the actual measured points were used instead, the error in these would contaminate the fit amplitudes for the five short term periods. These data points will be referred to as the W-pts.

Additional points from Figure 17.4.1 of Physical Geology, [

6](see Appendix) were digitized for the last 21,000 years (P-G-pts). The P-G-pts were not used in the fit but are plotted with the fit in some figures for comparison.

Finally, the GASL data points of the Jevrejeva et al. reconstruction points (J-pts data) were added.

Zero levels for these data sets had to be adjusted to the Jevrejeva et al. reconstruction. This was accomplished by computing a 10-year moving average of the J-pts data (J-avg) and then shifting the W-pts data to match this average at the year 1807. The P-G-pts was shifted down 735 mm and the W-pts data was shifted down by 110 mm. This put all the data at sea-level relative to 1930. The W-pts combined with the J-pts will be referred to as the WJ-pts data. The WJ-pts constitutes the input data for the least squares fit.

The least squares fit:

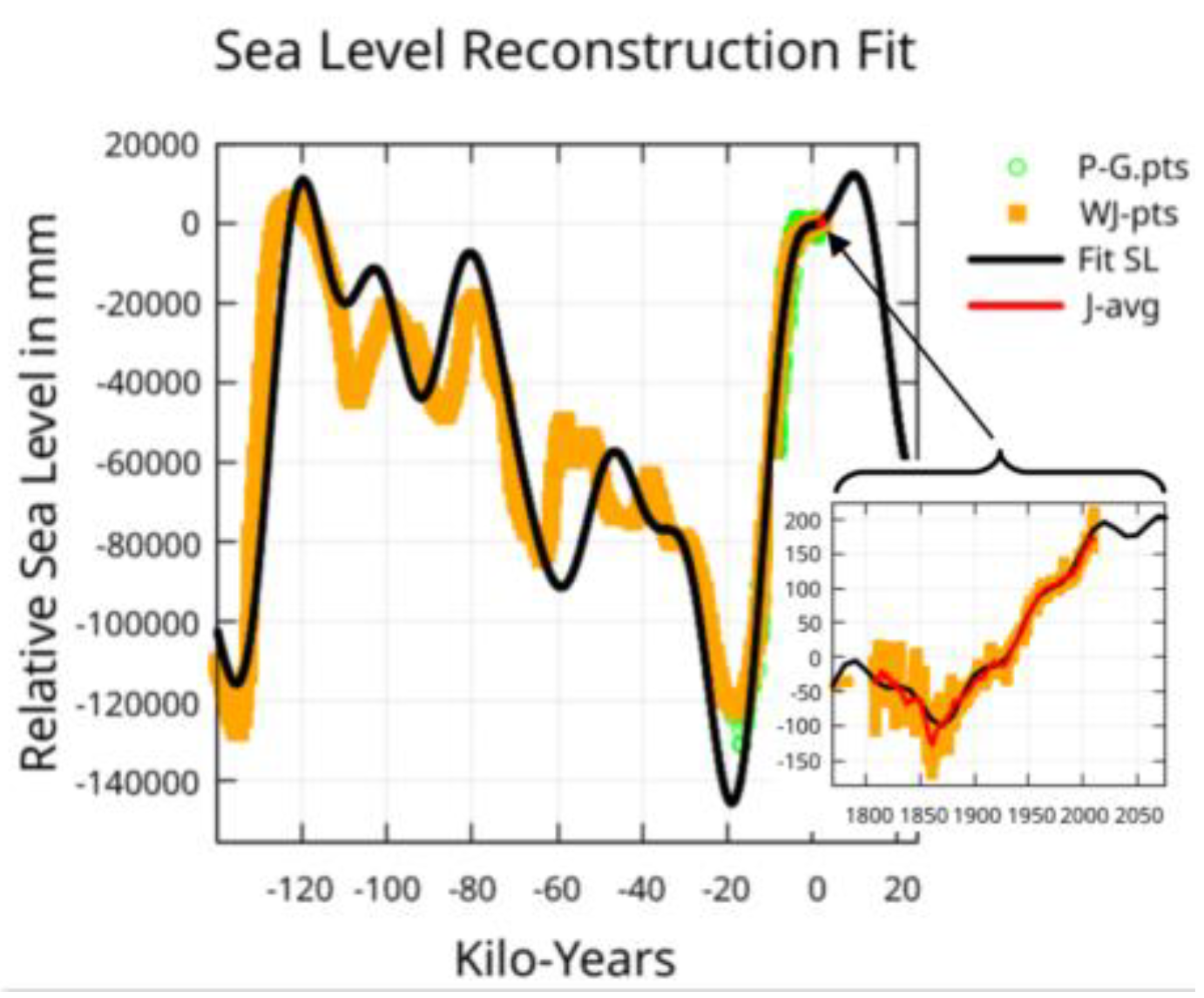

The data (WJ-pts) was fit with a constant and eleven periods, see

Appendix A. The fit is shown in

Figure 10. The fit includes the five periods identified by Stefani et al mentioned above, and the Milankovitch orbital cycles from Berger et al (1991): Table 6 precession,

23,105-yr, 19,022-yr; Table 7 obliquity

, 40,720-yr, 53,864-yr; Table 8 eccentricity

, 126787-yr, 96,492-yr. These periods are weighted averages of similar periods listed in the named tables. Averaging weights are determined by associated amplitudes in the same tables.

Figure 10 shows the fit and input data at kilo-year scaling. Some extrapolation is shown in

Figure 10. When the extrapolation was extended a million years into both the past and future, the projected sea-level rise never exceeded 40 meters above the 1930 level. This satisfies constraint (3).

The GASL of Jevrejeva et al. spans about 200 years which would represent less than two thousandth of the horizontal axis of

Figure 1 and is shown as an inset to the figure.

Figure 1 provides a visual evaluation of how well the fit matches the last 120,000 years of sea-level as well as a recent modern sea-level reconstruction over a 200-year period.

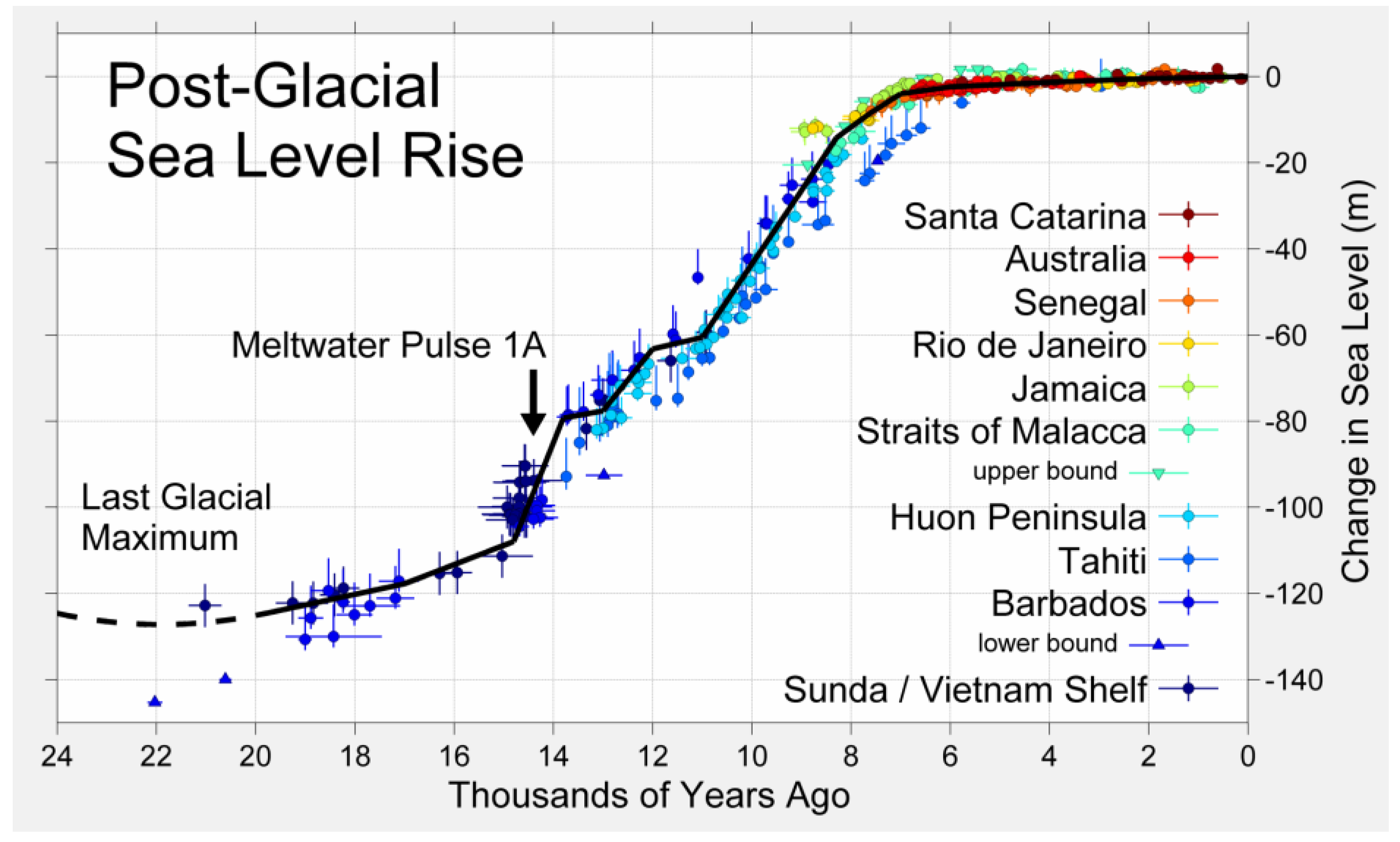

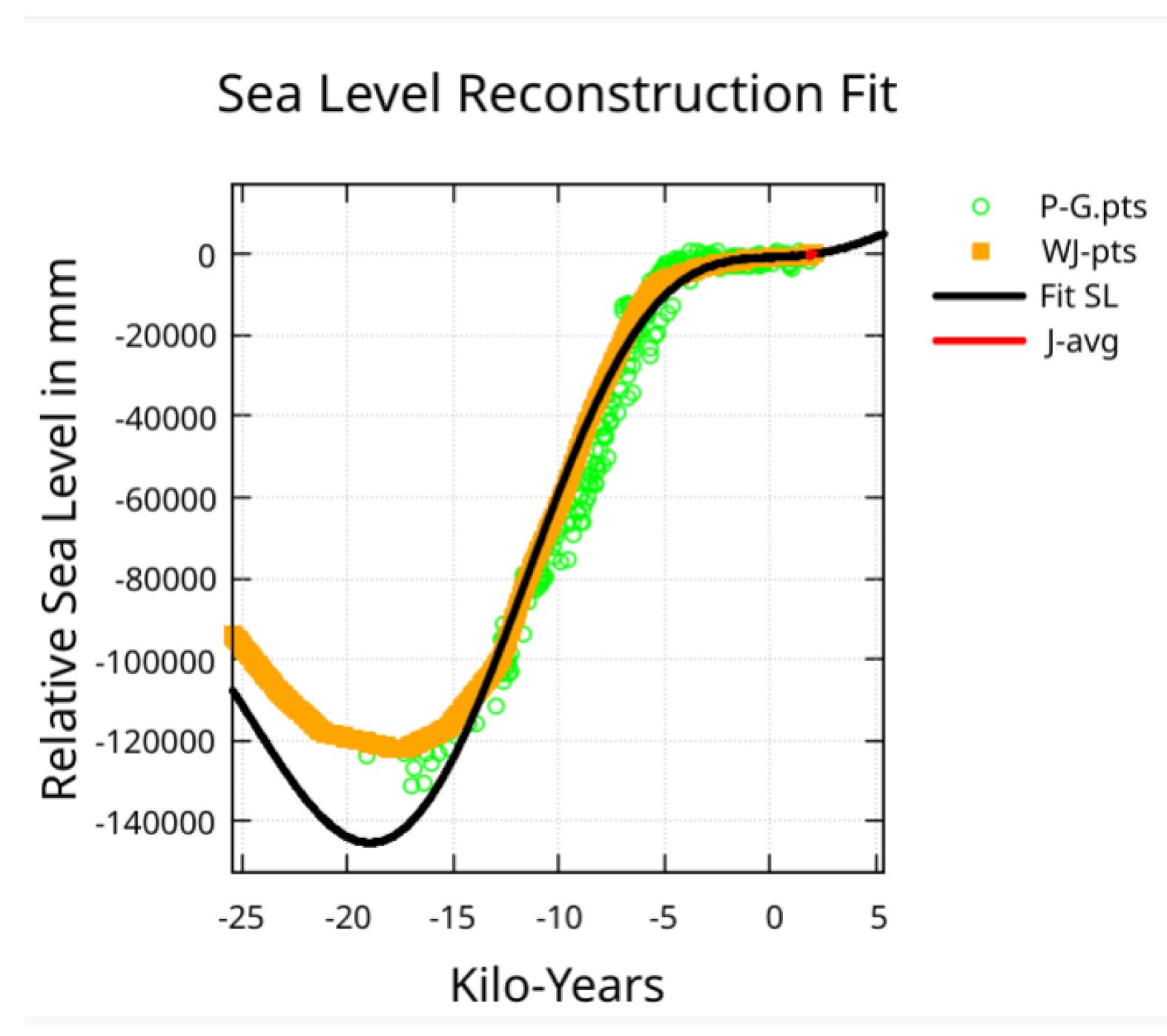

Figure 11 provides a visual evaluation of how well the fit matches with the W-pts coming out of the last glacial period. The deviation at -20 ky is troubling but the P-G-pts data shows considerable variation, and the fit is within the P-G-pts indicated lower bound. Options that fit this region more accurately will be discussed below.

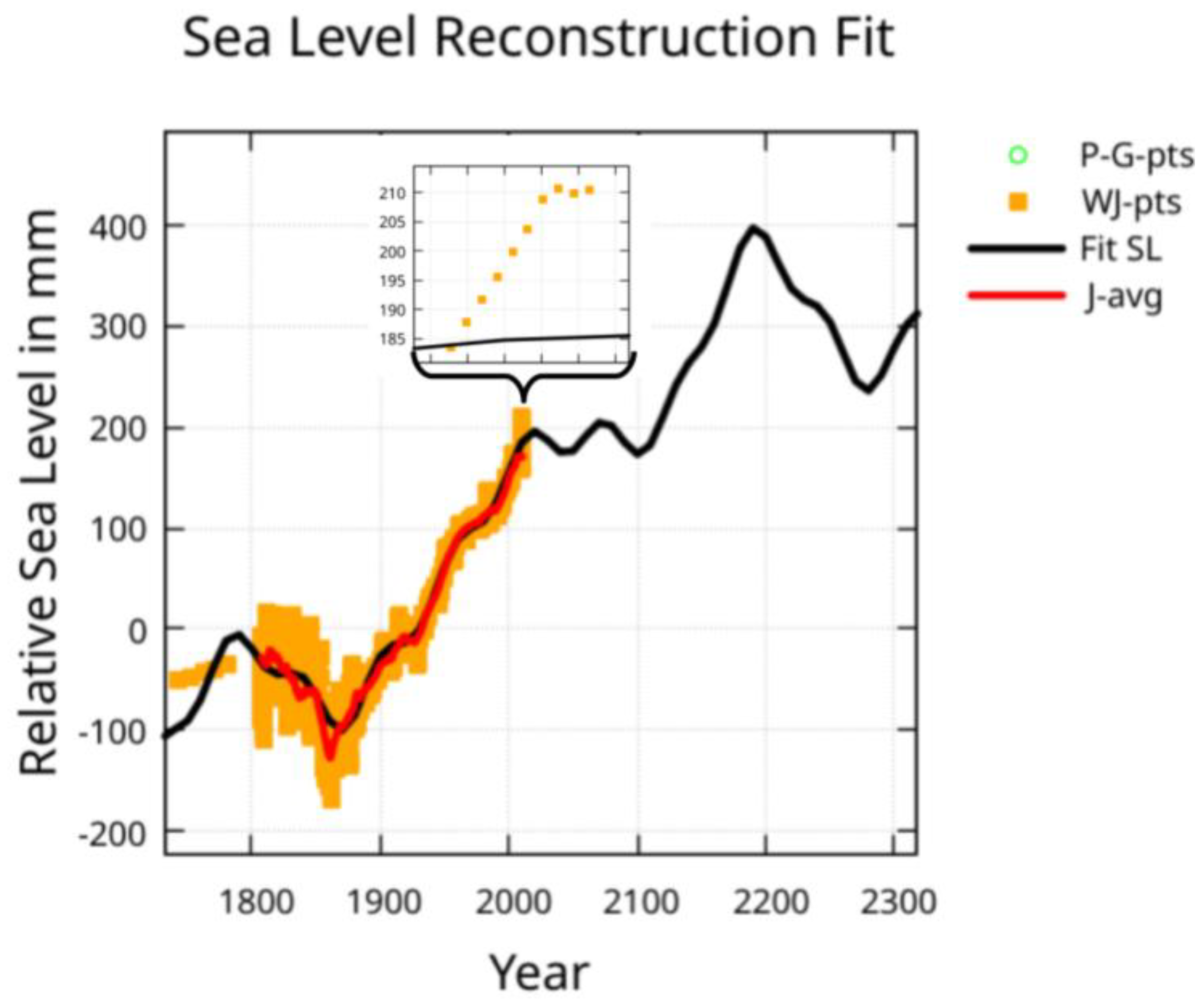

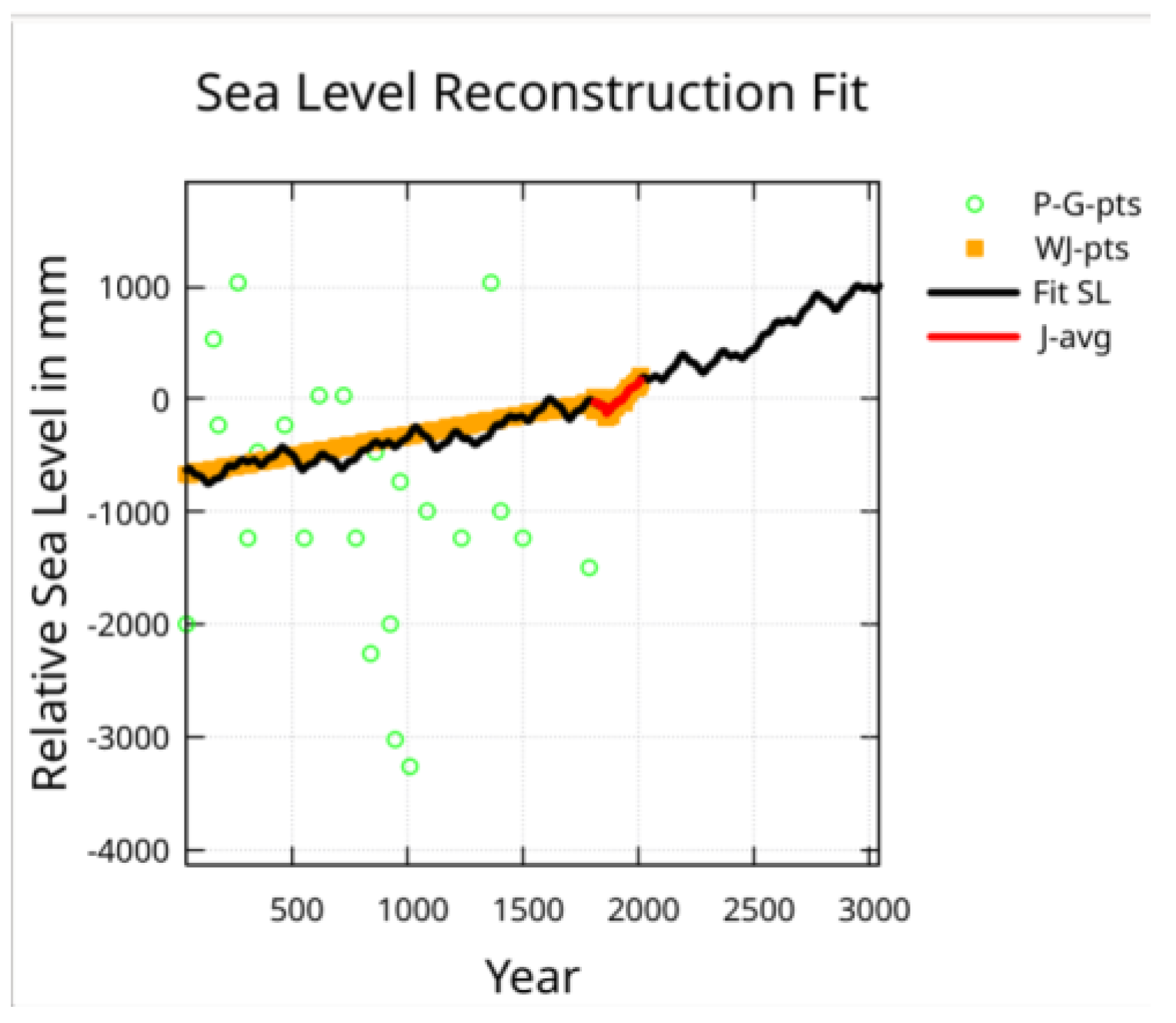

Figure 12 shows the fit leading up to the J-pts data and slightly beyond. Here the effect of the shorter periods becomes evident. The normalized covariance matrix indicates no fit interaction between the five shortest periods and the six longest periods except for a 14% interaction between the 19,022-yr period and the 579-yr period.

Figure 13 shows the J-pts input data covering the points of the fit evaluation with the 10-year average (J-avg) plotted on top. The shorter orbital periods identified by Stefani et al. have amplitudes primarily determined by the strongly weighted J-pts data with an obvious background slope determined by the longer orbital periods.

Figure 13.

Here is shown the Jevrejeva et al. reconstruction data and fit. The red line is a 10 year moving average of the input points. The local peak of 397 mm above the 1930 level is at year 2190.

Figure 13.

Here is shown the Jevrejeva et al. reconstruction data and fit. The red line is a 10 year moving average of the input points. The local peak of 397 mm above the 1930 level is at year 2190.

In

Figure 13 the extrapolation shows a rise of 397 mm above the 1930 level (about 200 mm above today’s level) by the year 2190 followed by a fall to near today’s levels by 2280 before rising again.

Rejected periods:

Berger et al. mentions an additional period in Table 8 for eccentricity of 404 ky. When this period was used in the fit the past and future extrapolation blew up to high sea-levels far exceeding 60 meters above 1930 levels thus violating constraint (3). Similar results were found when similar periods from the tables were not combined in a weighted average but entered into the fit together. This increased the number of fit periods but again the fit violated constraint (3).

Options:

If no weighting is applied (weight 1.0 for all points) and the J-pts data is part of the input, the fit R squared is 0.866 from -250 ky to +2 ky (up from 0.574). However, the fit finds sea-level for the year 2000 to be 11.7 meters below the 1930 level and falling. So weighing data corresponding to the far past the same as the near past improves the far past fit at the expense of large errors in the near past and present. This is especially true for the modern sea-level reconstructions since the year 1800, which are 1000 to 10,000 times more accurate. This supports: (1) the assumption of an unknown weak long term base temperature variation producing a corresponding long term base sea-level variation or (2) increasing error in the sea-level information as the date moves farther into the past or (3) possibly both.

Option B:

If the J-pts data is removed and the fit performed with the same weighting, then the peak in

Figure 1 at year 9,726 shifts to the year 9,746 with sea-level maximum of 13.0 meters above the 1930 level.

Option C:

As mentioned earlier there exists other approximate sea-level reconstructions for the last glacial period, Fernandez-Palacios et al., [

8] called F-P-pts here and shifted up by 1,670 mm to match J-pts. When this data is combined with the J-pts data and is fit, over this ~119,000-year time interval, using the same weighting as described in the Appendix, the R squared is 0.987. The R squared from -15,000 to +2010 is 0.997. The peaks and troughs in F-P-pts for this time interval are fit much closer (max deviation of 3 meters). There is an extrapolated peak, similar to the peak shown in

Figure 1, at year 12,584 with sea-level at 40.0 meters above the 1930 level.

Option D:

Limiting the WJ-pts input to the same date interval as the F-P-pts does not yield a better fit to the deep trough at date -17,500 years. The extrapolated peak shifts to the year 12,605 reaching 33.6 meters.

Option E:

The major difference between the F-P-pts and the WJ-pts over the last 119,000 years is the doublet peak between -60 ky and -50 ky in the WJ-pts that is missing from the F-P-pts data. If the 250 ky span of the WJ-pts data is fit while using a low weight for the date interval -60 ky to -50 ky, then the fit to the deep trough at -17,500 years deviates from the input by less than 2 meters. The extrapolated peak is at the year 10,269 with sea-level at 19 meters above the 1930 level.

Option A:

The fit shown in the figures to the WJ-pts, with the weights given in the appendix, is considered more reliable for extrapolation than the fit to the F-P-pts because it has input data extending back 250,000 years to stabilize the fit of the long periods. In addition, the extrapolated sea-level rise maximum for the current interglacial more closely matches that of the previous interglacial warm period. See

Table 1 for a summary of option characteristics.

Anything can be fit with 23 parameters:

The fit involves 23 parameters. With that many parameters how do we know the fit is meaningful?

The periods are associated with physical processes. Also recall that the four constraints applied and note that they involve more than just a minimum deviation fit. These constraints have already been used to eliminate some orbital periods from the fit.

As mentioned earlier when discussing

Figure 12, the normalized covariance matrix indicates almost no interaction between the five short periods and the six long periods.

The five short periods:

Holding the fit weight as specified in the Appendix, the fit to the 252,000 years of WJ-pts was performed using only the shortest of the five short periods. Then the fit was repeated using the two shortest periods, and so on. The R squared value for year 1800 is shown in

Table 2 for the five versions of the fit.

It is obvious that the R squared value is significantly improving as more periods are included until the 579-yr period is added. Why then use 579-yr period? When the 579-yr period is included, the fit is closer to the 10-year moving average of the Jevrejeva et al. reconstruction. If the 579 year period is omitted, then the future extrapolation immediately begins to fall and by year 2093 reaches a local minimum of only 14 mm above the 1930 sea-level. The R squared of 0.950 is essentially the same as the value found when fitting the J-pts data with a cubic and one period.

The six long periods:

If the 126,787-year period is omitted from the fit then R squared for year -250,000 falls to 0.33 and R squared for year -120,000 falls to 0.77. The maximum in sea-level for year -120,000 becomes -22.5 meters which is unacceptable.

If the 96,492-year period is omitted from the fit the only significant change is the peak sea-level at year -120,000 becomes 16.6 meters (6 meters higher).

If the 53,864-year period is omitted from the fit the R squared for year -250,000 falls to 0.29 and R squared for year -120,000 falls to 0.65. The maximum extrapolated sea-level is 64.3 meters, which is unacceptable.

If the 40,720-year period is omitted from the fit the maximum extrapolated sea-level is 76.5 meters which is unacceptable. The peak near year 10,000 becomes 49.7 meters which is an unlikely value.

If the 23,105-year period is omitted, then R squared for year -120,000 becomes 0.77 – significantly lower.

If the 19,022-year period is omitted from the fit then R squared for year -250,000 becomes 0.45 . The maximum extrapolated sea-level becomes 63.9 meters which is unacceptable.

Based on these findings the 96,492-year period is the only one that might be omitted from the fit. However, it is a physically indicated period and including it does not violate any constraints. Therefore, this period has been included in the reported fit.