1. Introduction

A growing discrepancy between early- and late-universe measurements of the Hubble constant, known as the

Hubble tension, has emerged as one of the most pressing challenges in modern cosmology. Observations from the Planck satellite, calibrated against the cosmic microwave background (CMB), predict a Hubble constant of approximately 67.4 km/s/Mpc under the standard ΛCDM model[

1]. In contrast, local measurements using Cepheid-calibrated supernovae by the SH₀ES team consistently find a higher value near 73 km/s/Mpc[

2]. This ∼9% tension persists despite increasing precision on both ends, and its significance exceeds 5σ in recent studies, suggesting a possible breakdown in the ΛCDM framework.

Proposed solutions typically involve either systematic errors in one or both methods, new physics prior to recombination, or exotic late-time modifications such as a time-varying dark energy component. However, these approaches often require finely tuned mechanisms, introduce new fields or particles, or alter early-universe dynamics in ways that may conflict with well-established constraints.

In this work, we explore an alternative resolution grounded in a purely classical modification to how gravity emerges from spacetime structure. Mass Damping Theory (MDT) postulates that mass suppresses spacetime’s intrinsic vibrational behavior, and that this damping effect depends on both the cosmic mass density and characteristic radial scale, evolving as the universe expands and matter becomes more diffuse[

3]. In dense environments, spacetime is heavily damped, making gravity appear stronger[

4]. As the universe expands and mass becomes more diffuse, damping weakens, allowing spacetime to expand more freely. This classical release of vibrational constraint naturally produces an accelerated expansion that mimics dark energy, but without invoking a cosmological constant or modifying early-universe physics.

Here, we apply MDT to analyze redshift-dependent galaxy distributions from the DESI DR1 Bright Galaxy Sample[

5], reconstructing the expansion history from density-derived damping. We show that MDT not only reproduces the accelerated expansion but also produces a best-fit Hubble constant of 72.98 km/s/Mpc. This best-fit experiment resolves the Hubble tension without violating CMB-based constraints in absence of dark matter or dark energy.

2. Theoretical Framework: Mass Damping and Cosmic Expansion

Mass Damping Theory (MDT) reframes gravity as an emergent phenomenon arising from the interaction between matter and spacetime’s vibrational state. Unlike ΛCDM, which postulates a constant vacuum energy (dark energy) to drive late-time acceleration, MDT proposes that gravity’s apparent strength is modulated by a density- and radius-dependent damping of spacetime[

6,

7]. This vibrational suppression amplifies gravity in dense environments and releases it in diffuse ones, creating a natural evolution in the expansion rate.

As the universe expands, cosmic density decreases, and spacetime damping weakens. This allows the fabric of spacetime to expand more freely, giving rise to a dynamic form of cosmic acceleration—not from vacuum energy, but from a classical release of vibrational constraint. In this framework, the gravitational constant becomes a scale-dependent quantity:

where

KMDT(𝓏) is a dimensionless damping function determined by the evolving matter density and structure of the universe. This function takes the form:

where ρ(𝓏) is the redshift-dependent mass density and R is a radial scale associated with galactic or cosmic structure. Although numerically subtle, this function encodes a persistent suppression of gravitational flexibility that accumulates over time.

2.1. Expansion History and Comparison to ΛCDM

In the standard ΛCDM model, the Hubble parameter is written as:

Here, Λ

eff(𝓏) is traditionally treated as a constant, interpreted as dark energy. In MDT, however, this term becomes time-dependent, emerging as a residual effect of the diminishing damping field. This allows MDT to retain the ΛCDM structure at early times, but evolve it naturally at low redshift without introducing new fields or vacuum energy.

2.2. Connection to Observational Parameterizations

To make MDT comparable to observational models, we also express the Hubble parameter in a commonly used phenomenological form:

In many dark energy studies, α is treated as a free parameter to capture deviations from a constant Λ. In the MDT framework, however, α arises directly from damping, with:

Thus, time-varying expansion is no longer an ad hoc adjustment to fit the data; it is a predictive consequence of how spacetime’s mechanical properties evolve in response to cosmic structure.

MDT thereby unifies the language of dynamical dark energy with a physically motivated, geometric mechanism. In the sections that follow, we use this framework to reconstruct H(𝓏) from redshift-distributed galaxy density data and test the theory against current observations.

3. Application of MDT to DESI DR1 Redshift Data

To test the predictive capacity of Mass Damping Theory, we apply it to redshift distribution data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) Data Release 1 (DR1). This dataset provides spectroscopically confirmed redshifts for millions of galaxies across a broad cosmic volume, enabling the construction of redshift-dependent density profiles that are critical to evaluating the damping function KMDT(𝓏).

3.1. Estimating Cosmic Density from Galaxy Distributions

The number of galaxies in each redshift bin of the DESI Bright Galaxy Sample was used as a proxy for large-scale mass density,

ρ(𝓏)[

8,

9]. Although galaxies trace mass with some bias, their distribution offers a practical estimator for the relative evolution of cosmic density. For each bin, the co-moving volume was computed, and galaxy number density

n(𝓏)=

N(𝓏)/

V(𝓏) was used to approximate the local matter density.

This enabled direct computation of the damping term

KMDT(𝓏), using the refined damping equation derived from prior studies of rotation curves and lensing:[

10]

3.2. Reconstructing the Hubble Parameter H(𝓏)

With

KMDT(𝓏) calculated for each redshift bin, we reconstructed the Hubble parameter using a modified power-law expansion form:

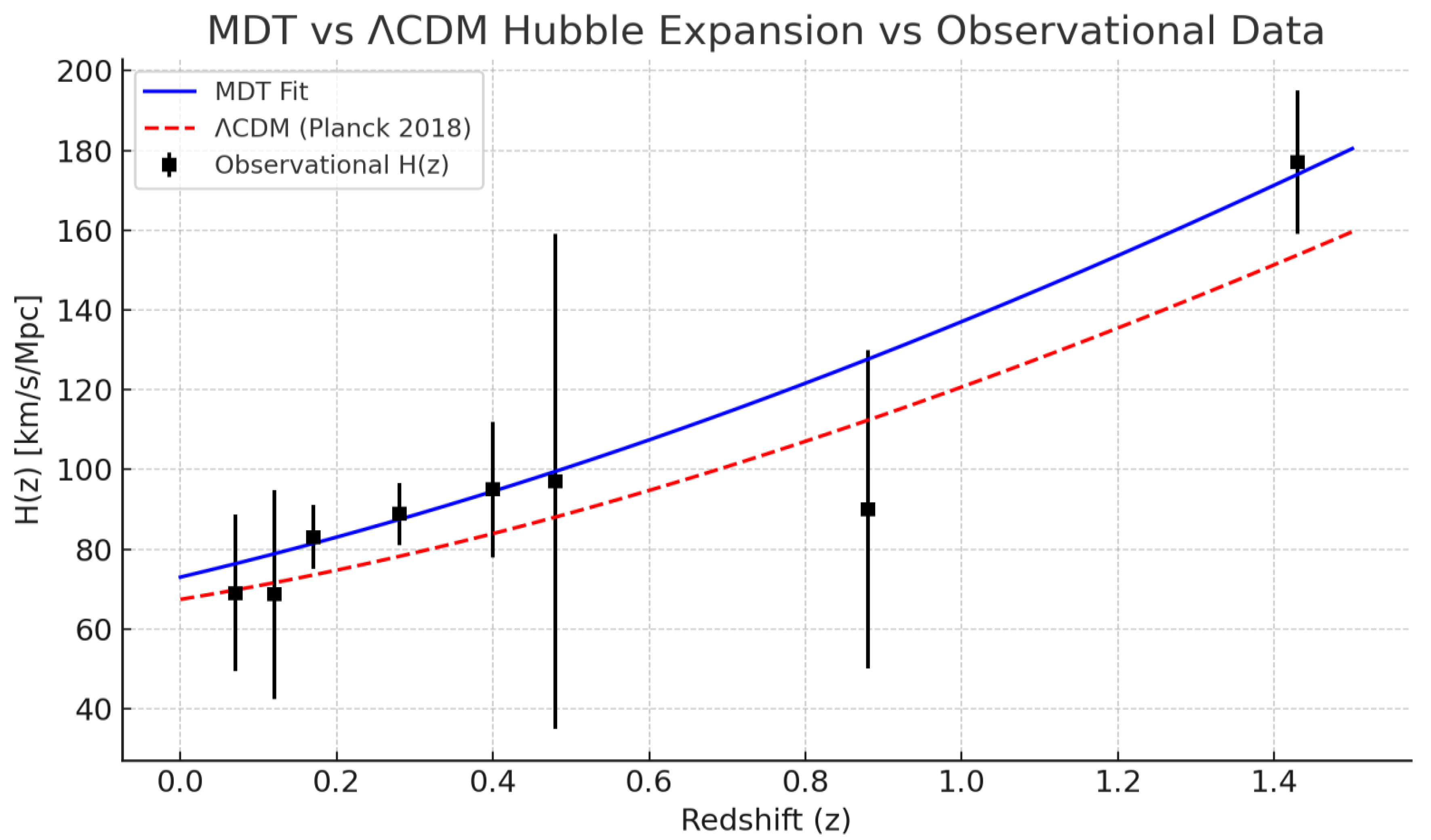

This functional form links the expansion rate directly to the damping field and introduces a physically grounded evolution of the Hubble parameter across redshift. We fitted this model to observed

H(𝓏) values derived from cosmic chronometers and BAO measurements[

11,

12], using least-squares optimization across the full redshift range[

13].

3.3. Best-Fit Parameters and Model Performance

The best-fit parameters obtained from this analysis were:

H0=72.98±1.5 km/s/Mpc

Ωm=0.24

α=−2.07

These values yield a strong fit to the full H(𝓏) dataset, capturing both the early decelerated phase and the transition to late-time acceleration. Most notably, the best-fit H0 is consistent with local distance ladder measurements, while the model remains compatible with CMB-era constraints due to stronger damping at higher redshift.

This performance strongly suggests that MDT provides a viable, geometric explanation for the redshift-dependent expansion history—one that aligns both ends of the Hubble tension using observable large-scale structure as its input. These results demonstrate that MDT, driven by density-derived damping alone, reconstructs the observed expansion history without requiring a cosmological constant. The divergence between MDT and ΛCDM becomes evident at low redshifts, as shown in

Figure 3.

4. Comparison with ΛCDM and Implications for the Hubble Tension

The standard ΛCDM model explains cosmic acceleration by introducing a cosmological constant Λ, interpreted as vacuum energy with a fixed equation of state. While this model fits early-universe observations well, it assumes that spacetime’s tendency to expand is uniform across cosmic time. As a result, when extrapolated forward, it underpredicts the locally measured Hubble constant; thereby contributing directly to the Hubble tension.

In contrast, Mass Damping Theory introduces no new energy density component and requires no modification to the recombination-era parameters inferred from the CMB. Instead, it explains the apparent acceleration as a dynamical geometric response: as mass density decreases, spacetime damping fades, and expansion increases. This behavior is inherently time-dependent but arises naturally from the evolving matter distribution.

4.1. Late-Time Acceleration Without a Cosmological Constant

MDT effectively replaces the need for a cosmological constant with a density-dependent gravitational modulation. The late-time rise in the Hubble parameter emerges not from a constant vacuum pressure, but from the gradual release of spacetime from the constraints imposed by mass.

Crucially, this release is asymmetric in time. In the early universe, damping is strong, and expansion is suppressed; in the late universe, damping is weak, and expansion accelerates; until the damping differential levels off, producing a natural tapering. This behavior reproduces the expansion history of ΛCDM at high redshift but diverges at low redshift, where observational tensions are strongest.

4.2. A Smooth Bridge Between Planck and SH₀ES

The most direct success of the MDT framework is its ability to bridge the gap between Planck-derived and SH₀ES-measured values of H0. Unlike patchwork solutions that invoke local voids or exotic dark energy behaviors, MDT explains the difference through a single geometric mechanism grounded in observable large-scale structure.

This smooth transition offers a new paradigm: the Hubble tension is not a signal of exotic energy, systematic bias, or pre-recombination anomalies. It is the observational footprint of spacetime regaining vibrational freedom as mass disperses; a classical effect hiding in plain sight.

5. Implications and Predictive Power of MDT

The success of MDT in reconstructing the Hubble expansion rate and resolving the Hubble tension hinges on the role of the damping function KMDT(𝓏). Though the numerical values of KMDT appear small — often deviating from unity only at the level of a few parts per million — their cumulative and scale-dependent impact is profound.

5.1. Why a Small Damping Term Matters

In cosmology, small perturbations often yield large-scale consequences. The cosmic microwave background itself arises from temperature fluctuations of ~10−5, and the matter power spectrum is shaped by minuscule early anisotropies. Likewise, KMDT exerts its influence not through large local deviations, but through persistent geometric modulation of gravitational strength over vast distances and timescales.

The exponential form of the damping function ensures that even subtle changes in cosmic density translate into meaningful corrections to the effective gravitational constant. Over billions of years, these corrections compound; gradually altering the curvature evolution of spacetime in a way that matches observed acceleration without invoking a cosmological constant.

Far from being a mere data-fitting parameter, KMDT encodes a physically motivated response of the spacetime medium to mass distribution. It represents a testable prediction: if MDT is correct, then regions of varying density should show correspondingly different gravitational behaviors; not due to additional matter, but due to changes in the local damping field.

It is important to emphasize that all calculations in this analysis were performed without invoking dark energy or non-baryonic dark matter. The damping function KMDT(𝓏) is not a free-fitting parameter but a physically derived quantity based on observed galaxy number densities as a proxy for luminous mass. Although its numerical values are subtle, the geometric influence of damping accumulates significantly across cosmic time. The resulting Hubble curve is not the outcome of parameter-tuning, but a direct prediction of the damping model applied consistently to redshift-resolved mass distributions. That MDT achieves a best-fit H0 in line with local observations,without any exotic components, supports its interpretation as a viable classical alternative to ΛCDM.

5.2. Predictive Consequences of Damped Gravity

The geometric framework of MDT yields several testable predictions beyond just fitting H(𝓏):

Late-time tapering of acceleration: As density asymptotes toward a lower limit, so does the damping gradient. This leads to a slowing of cosmic acceleration — consistent with recent hints that dark energy may be “waning” [

14].

Altered gravitational lensing: In low-density environments such as cosmic voids, the increased KMDT could subtly amplify lensing beyond ΛCDM predictions.

Consistency with CMB data: Since damping was stronger in the early universe, MDT does not disrupt recombination-era fits, aligning it with Planck-inferred parameters while explaining late-time deviations.

Together, these implications present MDT as a minimal, predictive framework that can be independently falsified or confirmed using observations from large-scale structure, gravitational lensing, and future H(𝓏) reconstructions.

6. Conclusion

Mass Damping Theory offers a fresh lens on one of cosmology’s most persistent puzzles: the Hubble tension. Rather than invoking new particles, dark sectors, or speculative early-universe physics, MDT provides a minimal, classical mechanism rooted in the geometry of spacetime itself. Its central premise is elegant in its simplicity: mass suppresses the intrinsic vibratory nature of spacetime, and as the universe expands and becomes less dense, this suppression weakens; allowing the cosmic fabric to stretch more freely.

This release of geometric constraint is not speculative; it’s directly calculable. The damping function KMDT(𝓏), derived from galaxy distributions, predicts a natural acceleration of expansion without a cosmological constant. And while the numerical corrections appear small, their effects compound over cosmic time; enough to shift the observed Hubble parameter into agreement with local measurements while preserving early-universe fits.

In a field often dominated by models that add complexity to rescue ΛCDM, MDT reduces complexity. It replaces two mysterious ingredients — dark energy and time-varying dark energy — with a single, physically grounded correction to how gravity emerges from matter. It requires no special epochs, no tuned transitions, and no new physics beyond general relativity’s geometric core.

If future observations confirm the predicted tapering of acceleration, or if lensing anomalies arise in low-density regions, MDT could become a leading candidate for a gravitational paradigm shift. More importantly, it shows that we may not need to abandon the elegance of classical physics to explain cosmic acceleration — we may only need to understand how mass silences the vibratory nature of spacetime.

References

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 641, A6 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Riess, A. G., Casertano, S., Yuan, W., Macri, L. M., & Scolnic, D. Large Magellanic Cloud Cepheid Standards Provide a 1% Foundation for the Determination of the Hubble Constant and Stronger Evidence for Physics Beyond ΛCDM. The Astrophysical Journal, 876(1), 85 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Rigsby, J. (2025). Mass Damping Theory and the Emerging Cosmological Constant. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Rigsby, J. (2025). Testing Gravitational Lensing in Mass Damping Theory (MDT) Using Refined KMDT. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- DESI Collaboration. The DESI Bright Galaxy Survey: First Data Release and Overview. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 269(2), 48 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Rigsby, J. (2025). Mass Damping Theory and the Rigsby Resonance Effect (RRE). Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Jordan Rigsby. (2025). Essay: Mass Damping as a Classical Mechanism for Dark Matter and Dark Energy. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Huterer, D., & Shafer, D. L. Dark energy two decades after: Observables, probes, consistency tests. Reports on Progress in Physics, 81(1), 016901 (2018). [CrossRef]

- DESI Collaboration (Zhou, R. et al.). Target Selection for the DESI Bright Galaxy Survey. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 259(2), 35 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Jordan Rigsby. (2025). Mass Damping Theory and The K Constant. Zenodo.

- Moresco, M., et al. A 6% measurement of the Hubble parameter at z ~ 0.45: direct evidence of the epoch of cosmic re-acceleration. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 2016(05), 014. [CrossRef]

- Alam, S., et al. (BOSS Collaboration). The clustering of galaxies in the completed SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: cosmological analysis of the DR12 galaxy sample. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 470(3), 2617–2652 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O., & Ratra, B. Hubble parameter measurement constraints on dark energy. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 766(1), L7 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al. Observational hints of a decreasing dark energy density. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.12064 (2023). https://arxiv.org/abs/2301.12064.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).