Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Extraction and Purification

2.2. Purification of the Active Fraction via Cationic Exchange Chromatography

2.3. Biofilm Eradication Assay

2.4. Proteolytic Activity Measurement

2.5. Effect of Standard Inhibitors on Protease Activity

2.6. Effect of Detergents, Organic Solvents and Metal Ions on Proteolytic Activity

2.7. Effect of pH and Temperature on Proteolytic Activity

2.8. Zymography

2.9. Determination of Vmax and km

3. Results and Discussion

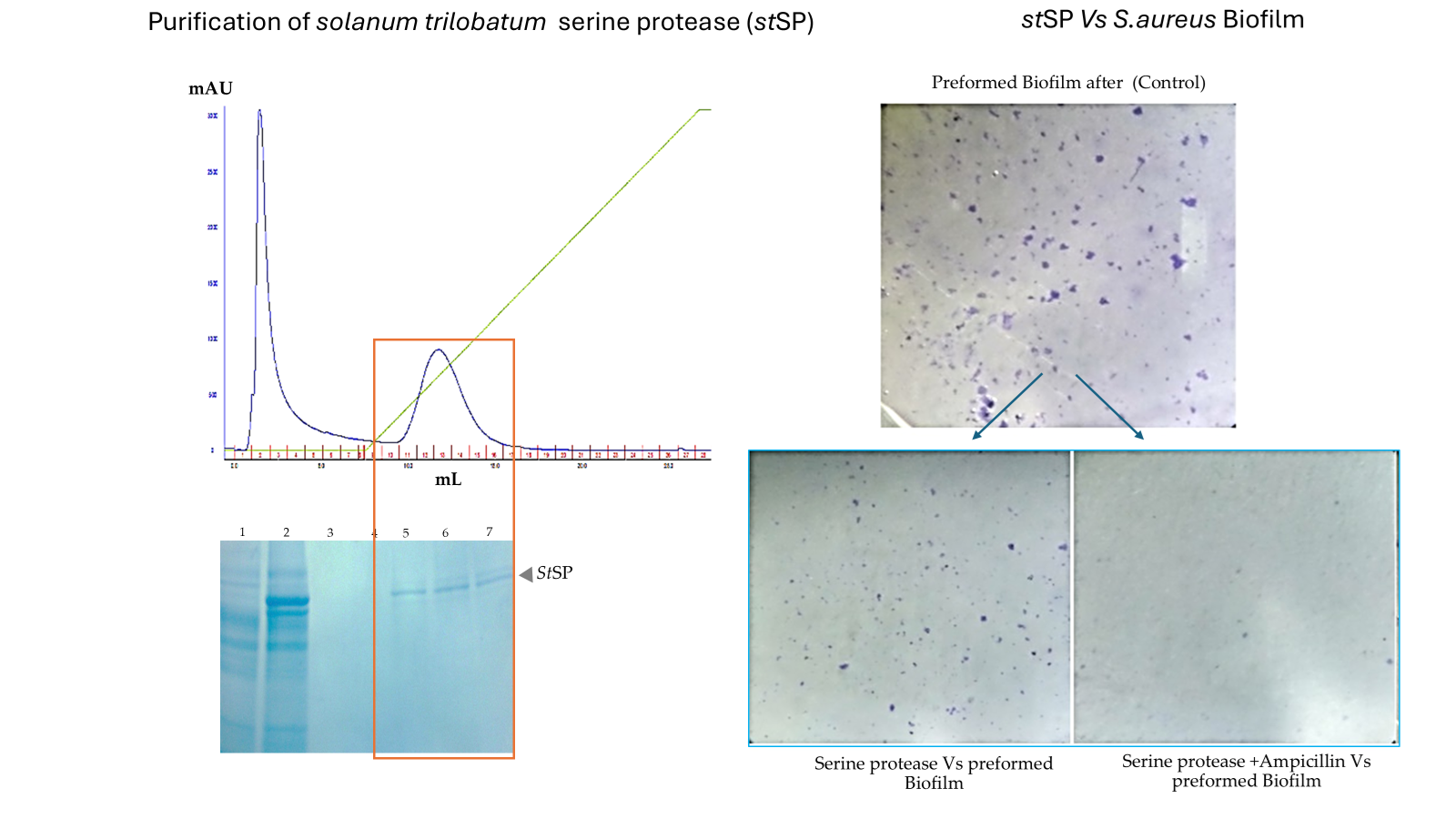

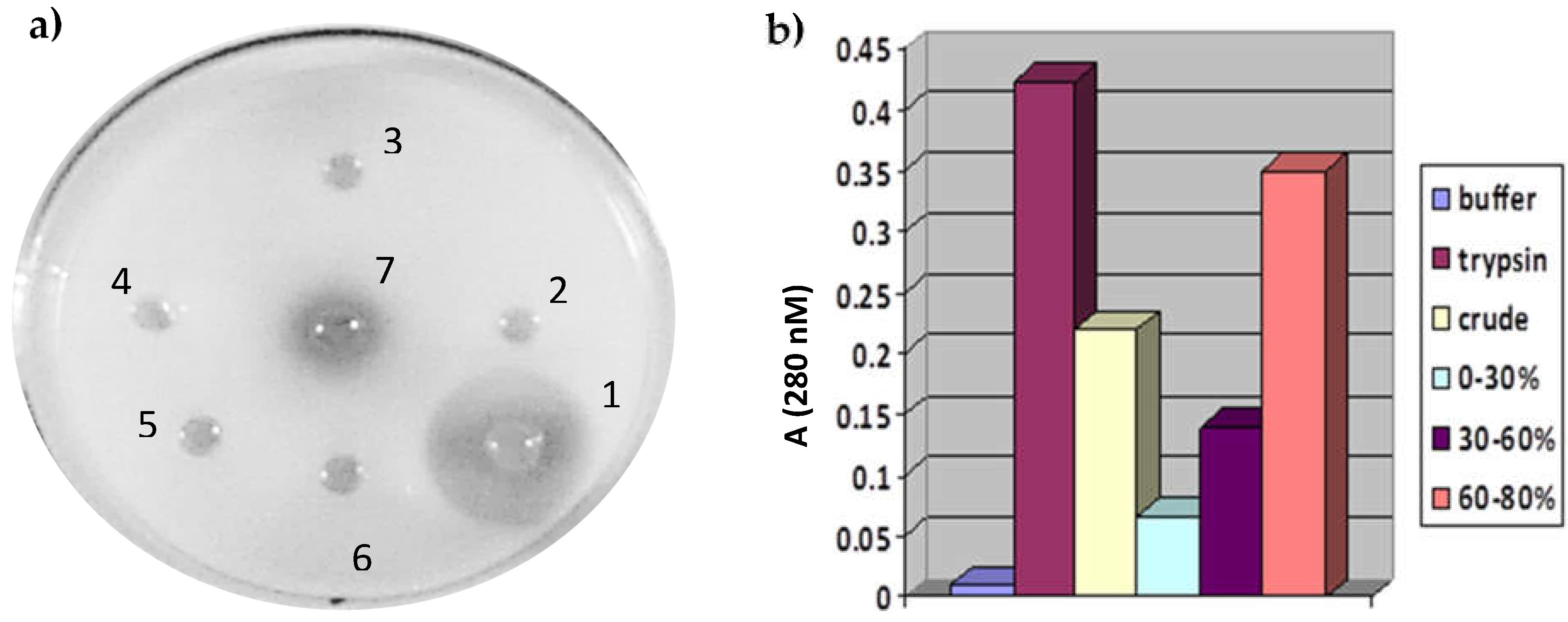

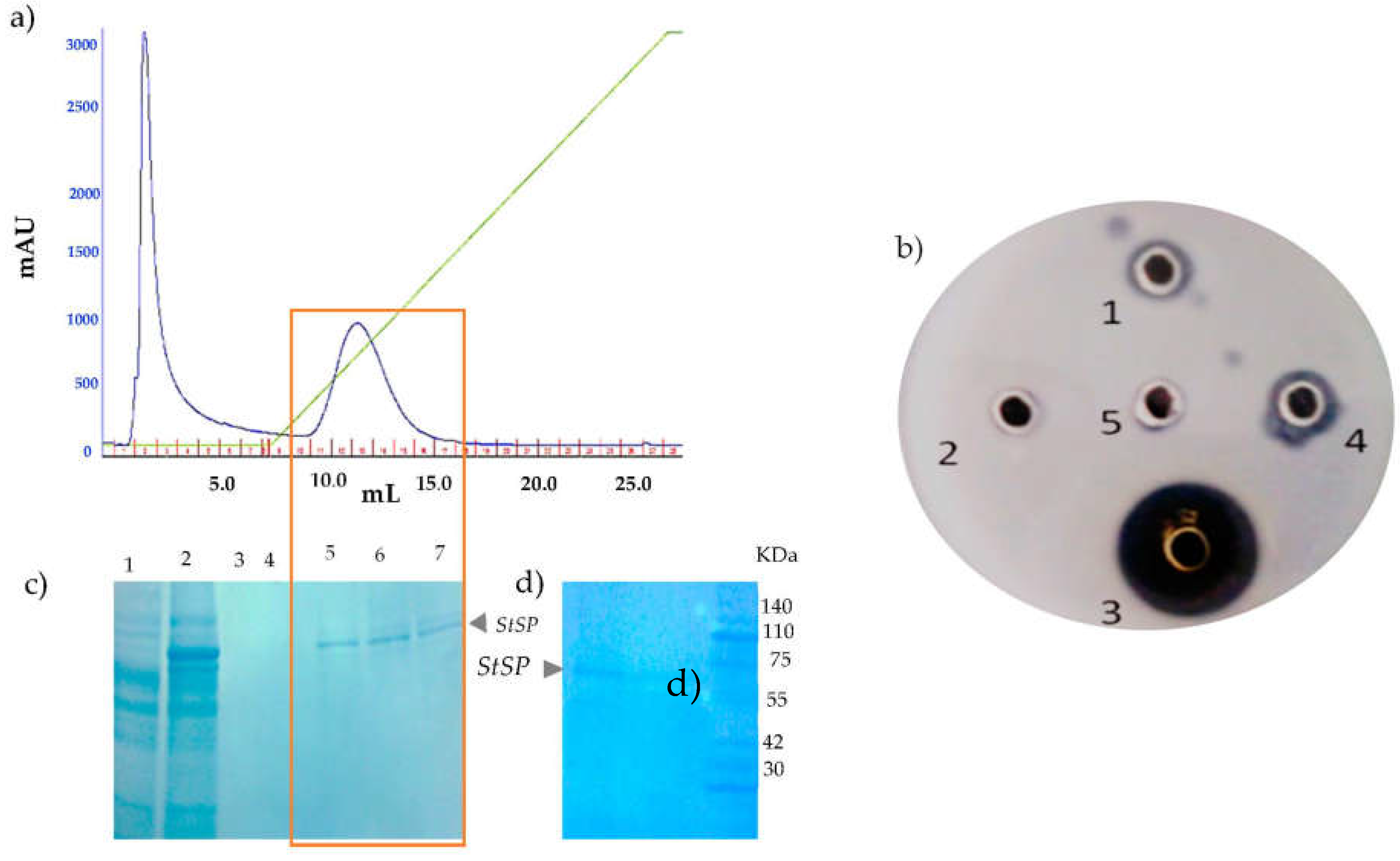

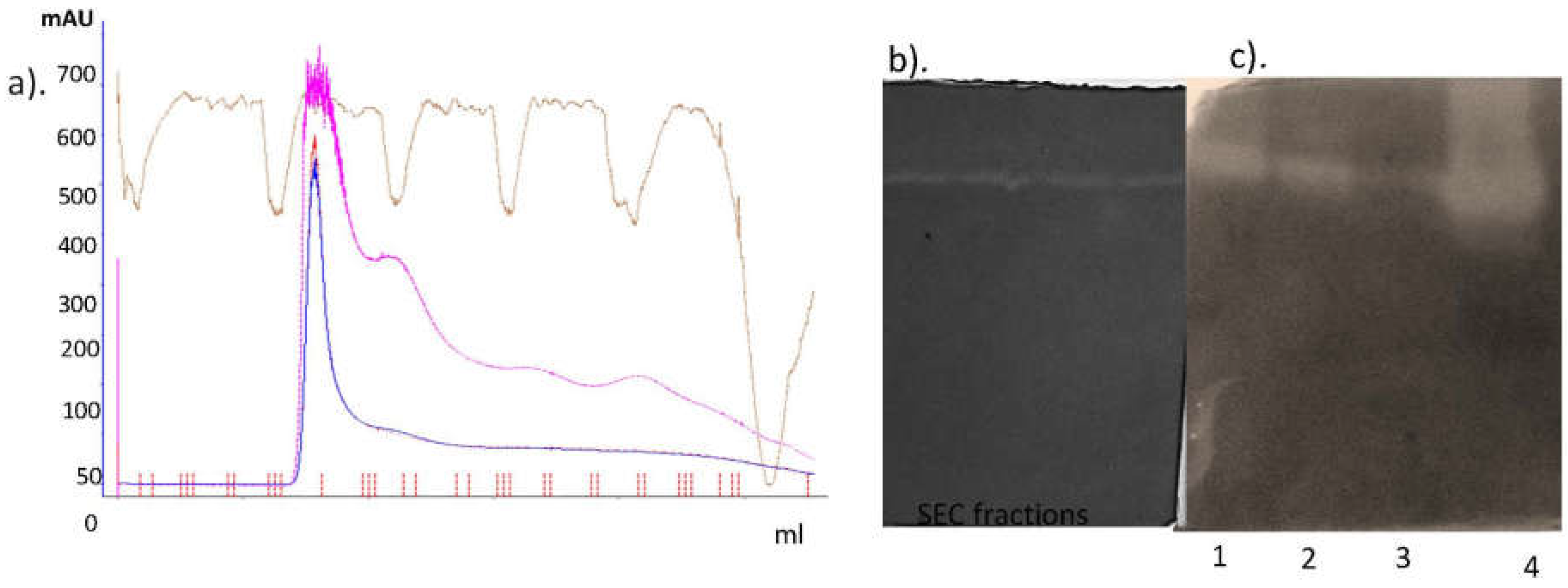

3.1. Isolation, and Purification of Protease from Solanum trilobatum

3.2. Inhibition of Serine Protease by Serine Protease Inhibitor (PMSF)

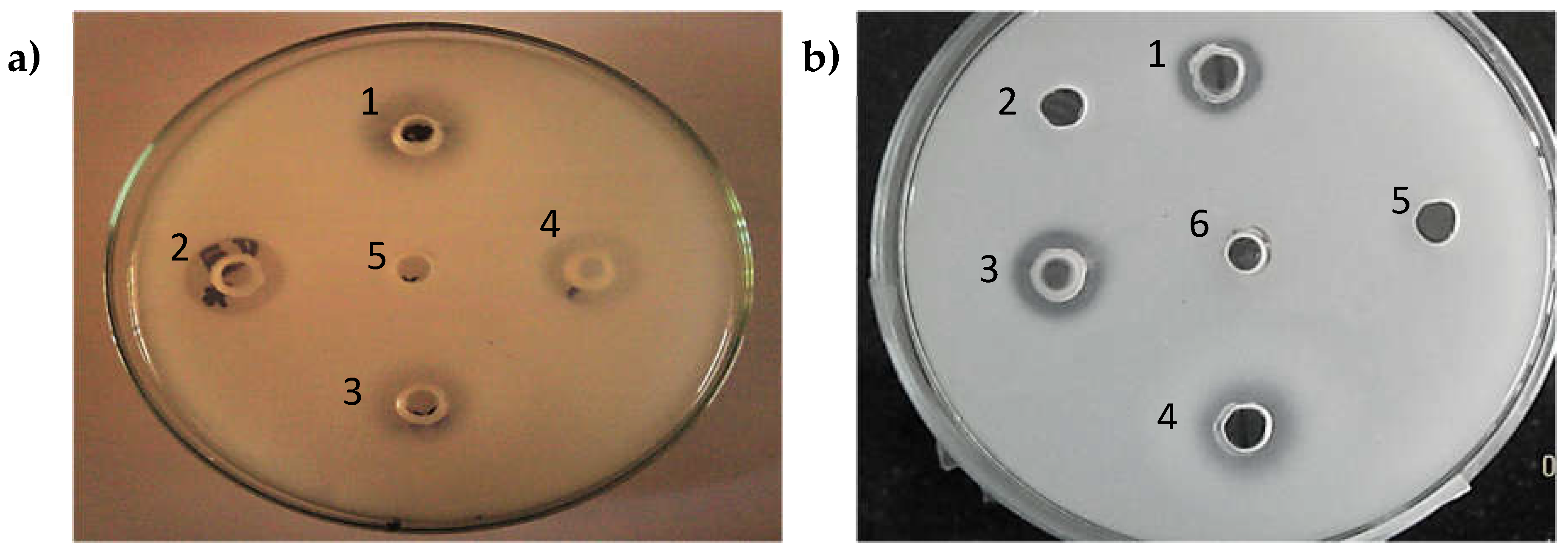

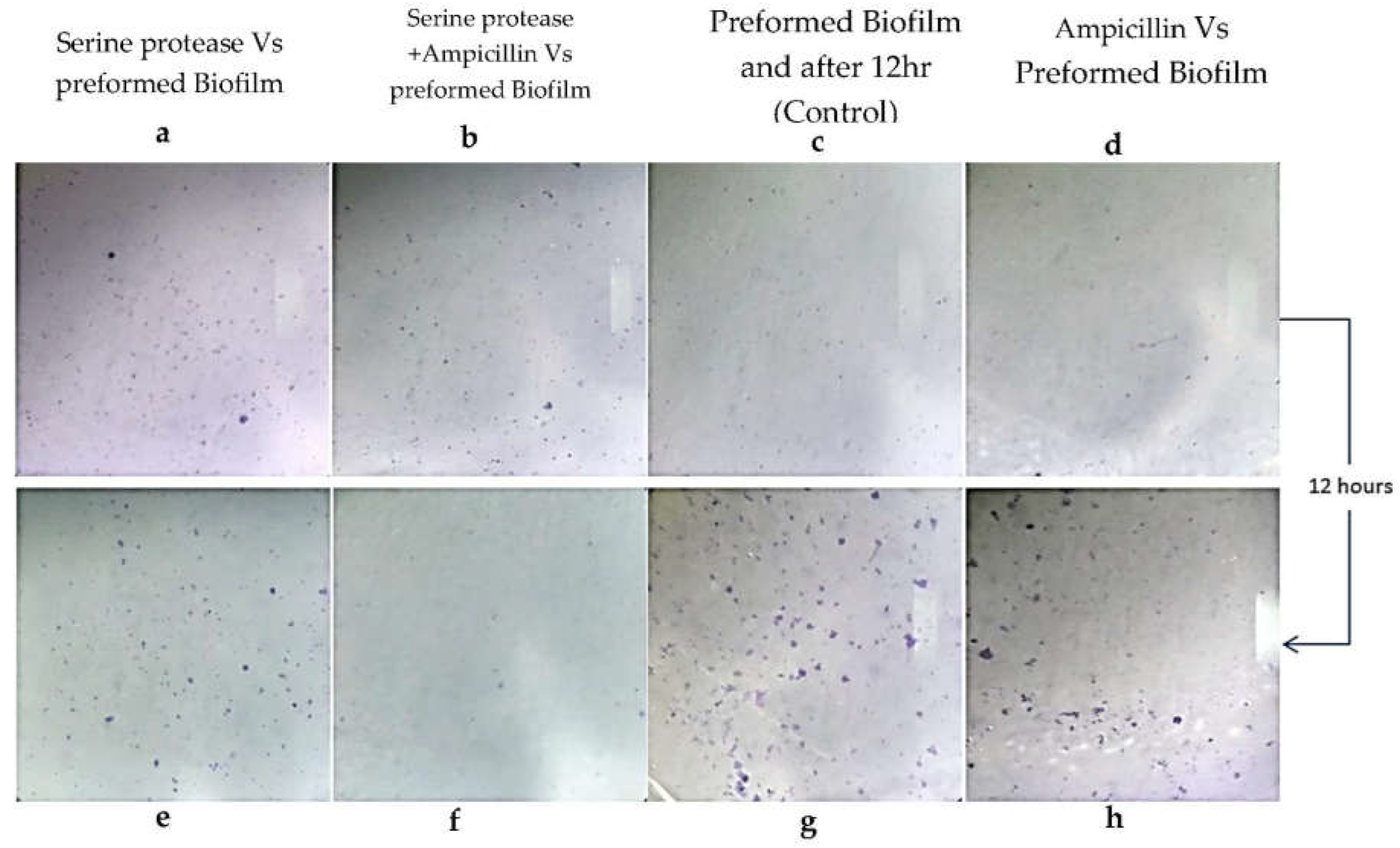

3.3. Staphylococcus aureus Pre-Formed Biofilm Eradicated by StSP

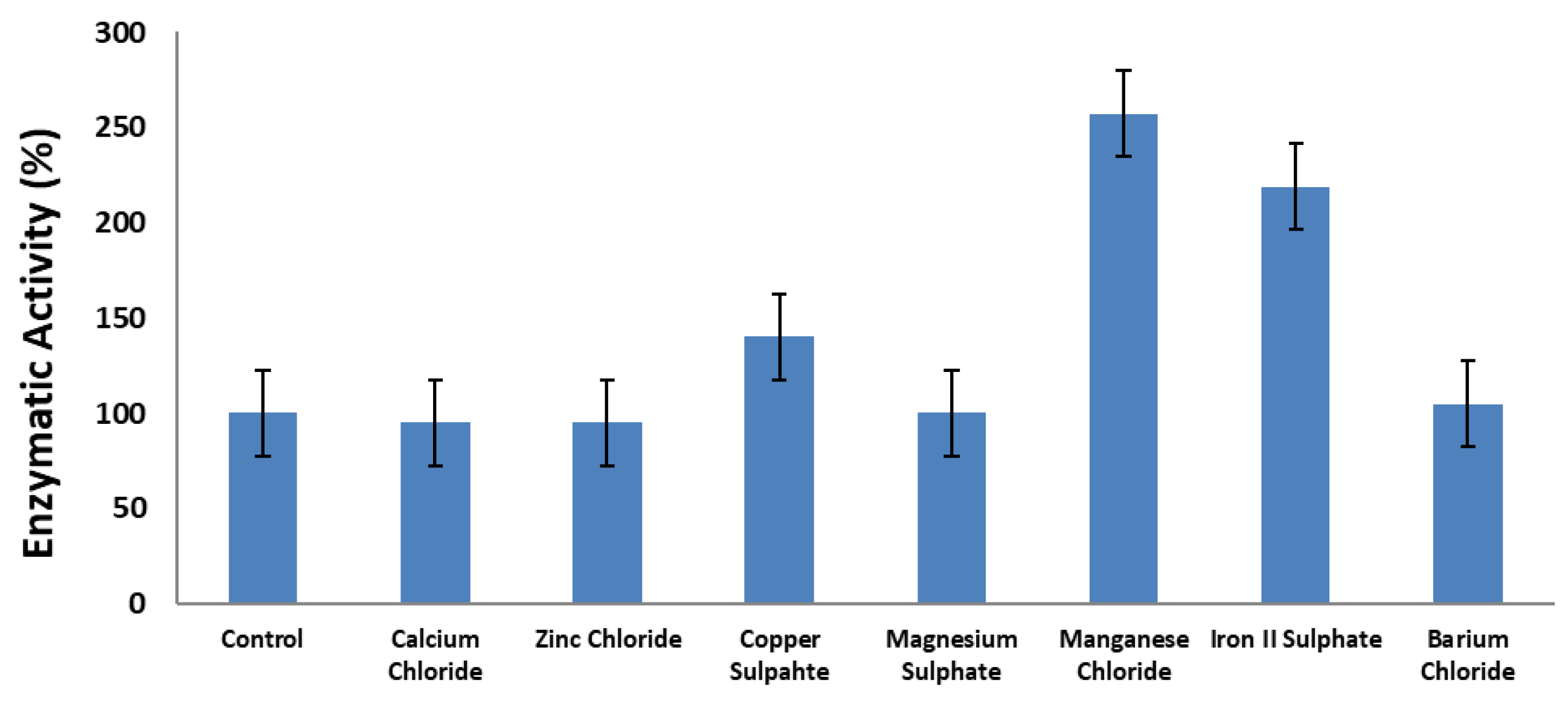

3.4. Effect of Metal Ions

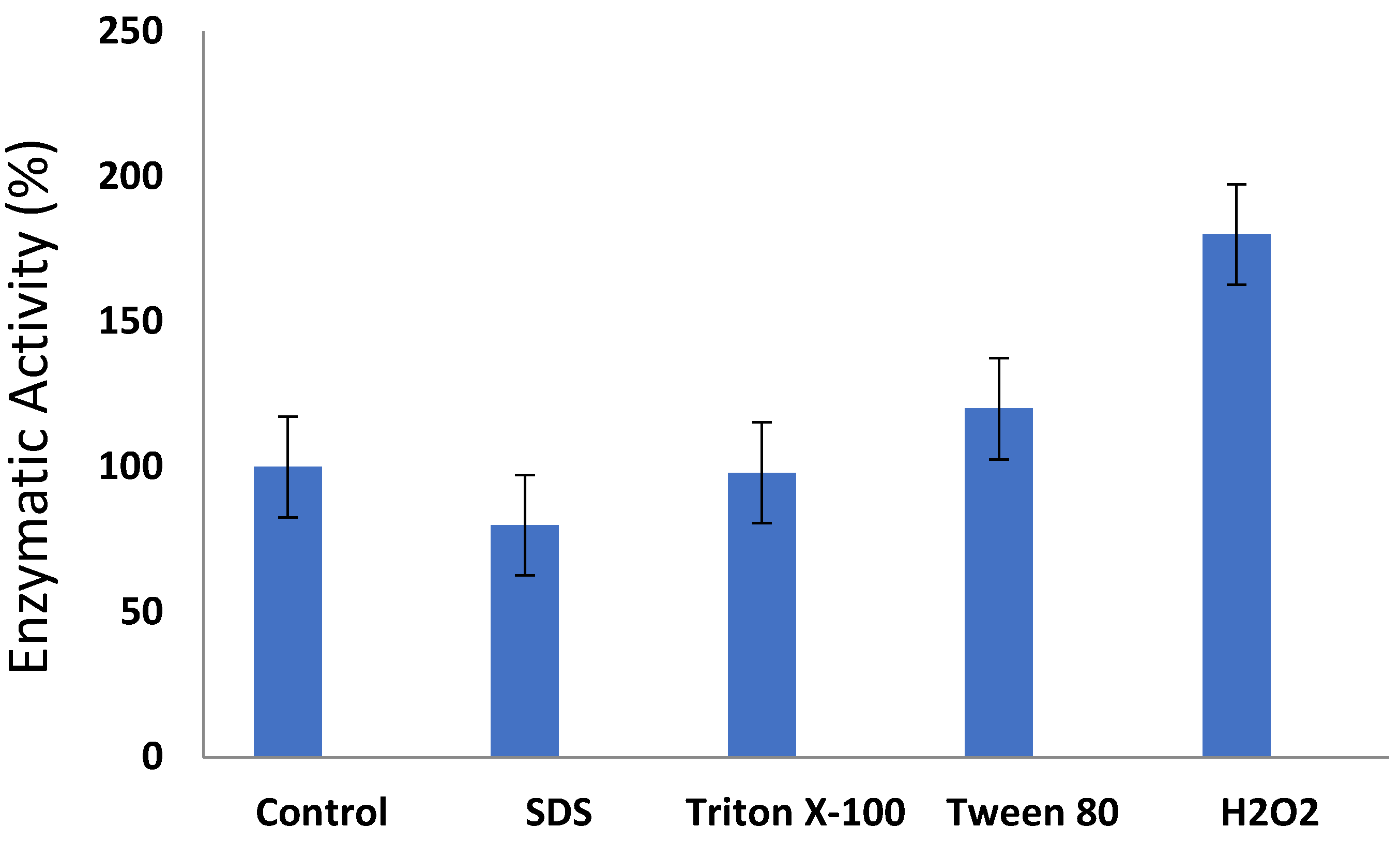

3.5. Effect of Surfactants

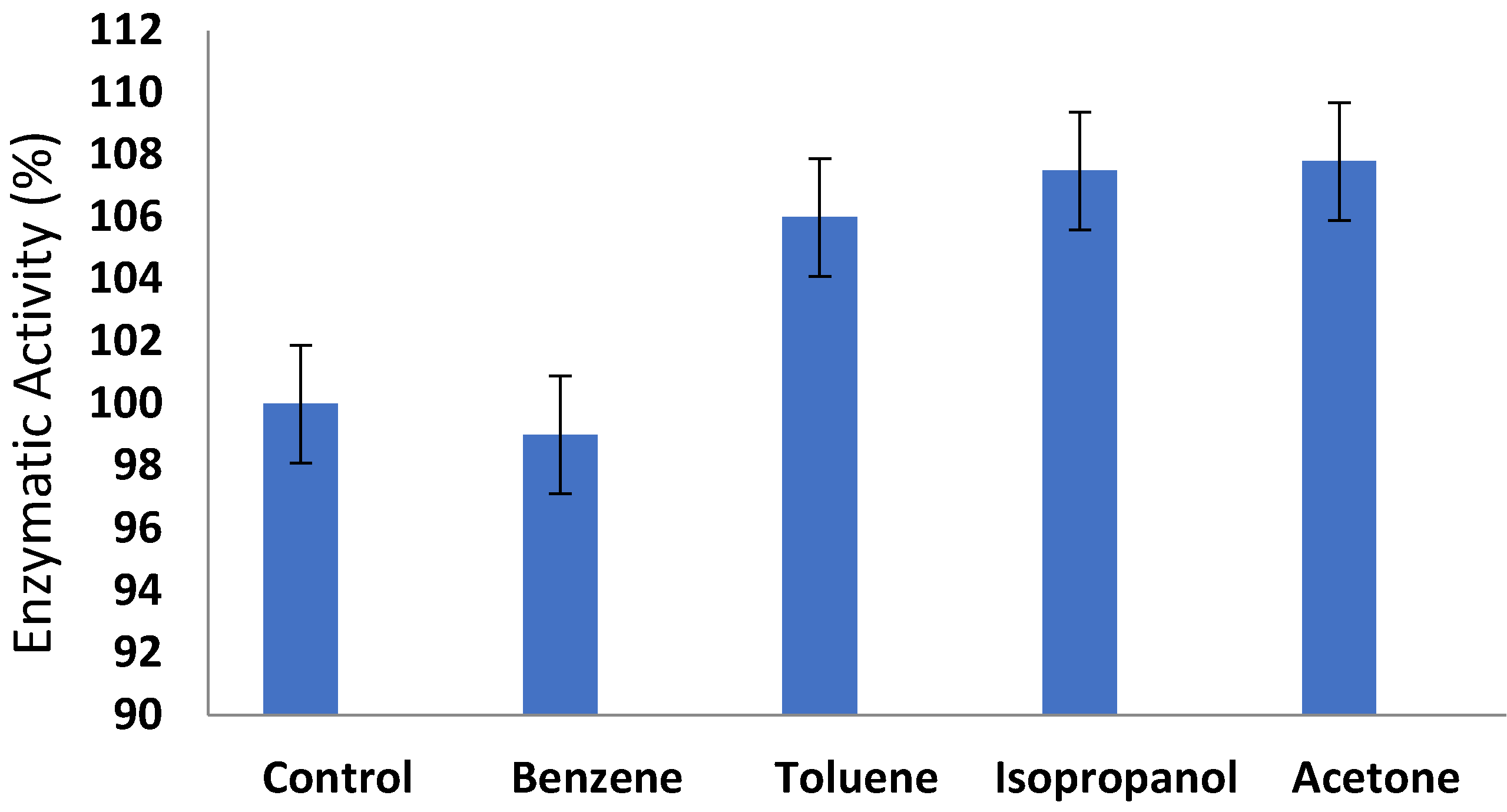

3.6. Effect of Organic Solvents

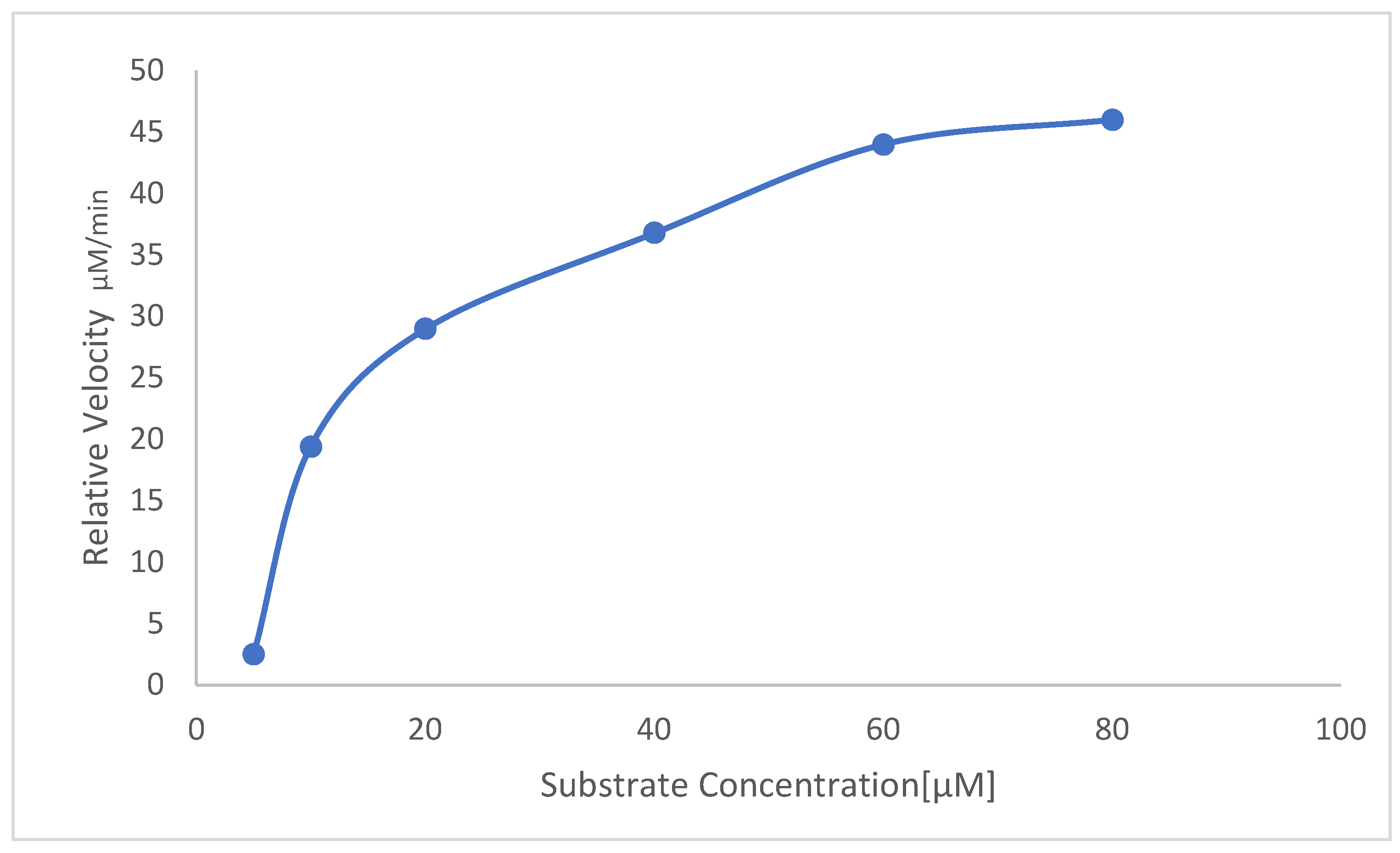

3.7. Determination of Kinetic Parameters

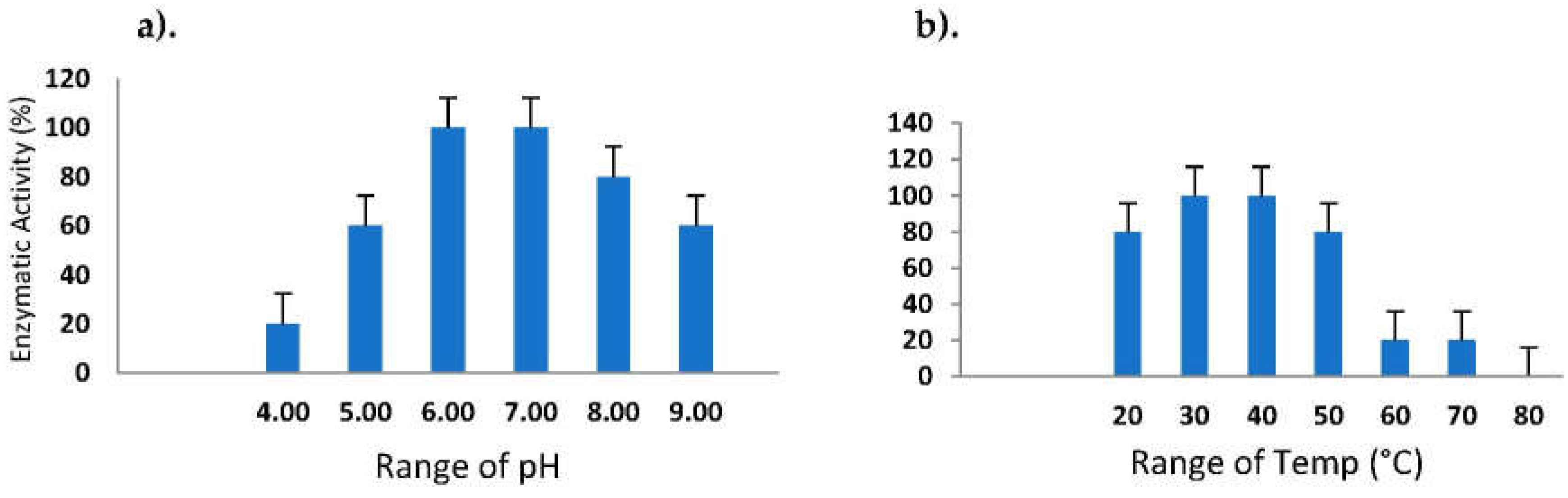

3.8. Sustainability of Various pH and Temperature

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ch’ng J.-H., Chong K. K., Lam L. N., Wong J. J., & Kline K. A. (2019). Biofilm-associated infection by Enterococci. Nat. Rev. Microbiol, 17, 82–94.

- Hall-Stoodley L., Costerton J. W., & Stoodley P. (2004). Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol, 2, 95–108. [CrossRef]

- Gunn J. S., Bakaletz L. O., & Wozniak D. J. (2016). What’s on the outside matters: the role of the extracellular polymeric substance of gram-negative biofilms in evading host immunity and as a target for therapeutic intervention. J. Biol. Chem, 291, 12538–12546. [CrossRef]

- Jones E. A., McGillivary G., & Bakaletz L. O. (2013). Extracellular DNA within a nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae-induced biofilm binds human defensin-3 and reduces its antimicrobial activity. J. Innate Immun, 5, 24–38. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Moser, C., Wang, H. Z., Høiby, N., & Song, Z. J. (2015). Strategies for combating bacterial biofilm infections. International Journal of Oral Science, 7(1), 1–7.

- Haaber, J., Cohn, M. T., Frees, D., Andersen, T. J., & Ingmer, H. (2012). Planktonic aggregates of Staphylococcus aureus protect against common antibiotics. PLoS One, 7(7), e41075.

- Ciofu, O., Mandsberg, L. F., Wang, H., & Hoiby, N. (2012). Phenotypes selected during chronic lung infection in cystic fibrosis patients: implications for the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm infections. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology, 65, 215–225. [CrossRef]

- Roy, R., Tiwari, M., Donelli, G., & Tiwari, V. (2018). Strategies for combating bacterial biofilms: A focus on anti-biofilm agents and their mechanisms of action. Virulence, 9(1), 522–554. [CrossRef]

- Salli, K. M., & Ouwehand, A. C. (2015). The use of in vitro model systems to study dental biofilms associated with caries: a short review. Journal of Oral Microbiology, 7, 26149. [CrossRef]

- Giordani, B., Costantini, P. E., Fedi, S., Cappelletti, M., Abruzzo, A., Parolin, C., ... & Vitali, B. (2019). Liposomes containing biosurfactants isolated from Lactobacillus gasseri exert antibiofilm activity against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, 139, 246-252. [CrossRef]

- Hogan, S., Zapotoczna, M., Stevens, N. T., Humphreys, H., O’Gara, J. P., & O’Neill, E. (2017). Potential use of targeted enzymatic agents in the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm-related infections. Journal of Hospital Infection, 96(2), 177–182.

- Gudiña, E. J., Rangarajan, V., Sen, R., & Rodrigues, L. R. (2013). Potential therapeutic applications of biosurfactants. Trends in pharmacological sciences, 34(12), 667-675.

- Römling, U. & C. Balsalobre. (2012). Biofilm infections, their resilience to therapy and innovative treatment strategies. J Intern Med, 272(6), 541–561. [CrossRef]

- Gharieb, R. M. A., Saad, M. F., Mohamed, A. S., & Tartor, Y. H. (2020). Characterization of two novel lytic bacteriophages for reducing biofilms of zoonotic multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and controlling their growth in milk. LWT, 124, 109145.

- Manohar, R., Kutumbarao, N. H. V., Krishna Nagampalli, R. S., Velmurugan, D., & Gunasekaran, K. (2018). Structural insights and binding of a natural ligand, succinic acid with serine and cysteine proteases. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 495(1), 679-685.

- Smith, A., Datta, S. P., Smith, G. H., Campbell, P. N., Bentley, R., & McKenzie, H. (2000). Oxford dictionary of biochemistry and molecular biology. Oxford University Press.

- Antão, C. M., & Malcata, F. X. (2005). Plant serine proteases: biochemical, physiological and molecular features. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 43(7), 637-650.

- Ahmed, I. A. M., Morishima, I., Babiker, E. E., & Mori, N. (2009). Characterisation of partially purified milk-clotting enzyme from Solanum dubium Fresen seeds. Food Chemistry, 116(2), 395-400.

- Govindan, S., Viswanathan, S., Vijayasekaran, V., & Alagappan, R. (1999). A pilot study on the clinical efficacy of Solanum xanthocarpum and S. trilobatum in bronchial asthma. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 66(2), 205-210. [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, S., & Balu, S. (2000). Ethnobotanical studies on S. trilobatum L.-an Indian drug plant. In Ethnobotany and medicinal plants of Indian subcontinent (pp. 43-46). Jodhpur: Scientific Publishers.

- Mohanan, P., & Devi, K. (1996). Cytotoxic potential of the preparations from S. trilobatum and the effect of sobatum on tumour reduction in mice. Cancer Letters, 110(1), 71-76.

- Shahjahan, M., Sabitha, K., Jainu, M., & Devi, C. S. (2004). Effect of S. trilobatum against carbon tetra chloride induced hepatic damage in albino rats. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 120, 194-198.

- Emmanuel, S., Ignacimuthu, S., Perumalsamy, R., & Amalraj, T. (2006). Antiinflammatory activity of S. trilobatum. Fitoterapia, 77(7), 611-612.

- Doss, A., Mubarack, H. M., & Dhanabalan, R. (2009). Antibacterial activity of tannins from the leaves of S. trilobatum Linn. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 2(2), 41-43.

- Radhakrishnan, M., Palayam, M., Altemimi, A. B., Karthik, L., Krishnasamy, G., Cacciola, F., ... Leucine-Rich, P. (2022). Anti-Bacterial Protein against Vibrio cholerae, Staphylococcus aureus from Solanum trilobatum Leaves. Molecules, 27(4), 1167.

- Kannabiran, K., & Thanigaiarassu, R. R. (2008). Antibacterial Activity of Saponin Isolated from the Leaves of S. trilobatum Linn. Journal of Applied Biological Sciences, 2(3).

- Shahjahan, M., Vani, G., & Shyamaladevi, C. (2005). Effect of S. trilobatum on the antioxidant status during diethyl nitrosamine induced and phenobarbital promoted hepatocarcinogenesis in rat. Chemico-biological Interactions, 156(2), 113-123.

- Rajkumar, S., & Jebanesan, A. (2005). Oviposition deterrent and skin repellent activities of S. trilobatum leaf extract against the malarial vector Anopheles stephensi. Journal of Insect Science, 5(1), 15.

- Thirumalaiandi, R., Selvaraj, M. G., Rajasekaran, R., & Subbarayalu, M. (2008). Cloning and characterization of resistance gene analogs from under-exploited plant species. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, 11(4), 4-5.

- Jantorn, P., Tipmanee, V., Wanna, W., Prapasarakul, N., Visutthi, M., & Sotthibandhu, D. S. (2023). Potential natural antimicrobial and antibiofilm properties of Piper betle L. against Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and methicillin-resistant strains. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 317, 116820.

- Gomes, F., Martins, N., Ferreira, I. C., & Henriques, M. (2019). Anti-biofilm activity of hydromethanolic plant extracts against Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bovine mastitis. Heliyon, 5(5). [CrossRef]

- Jeyarajan, S.; Ranjith, S.; Veerapandian, R.; Natarajaseenivasan, K.; Chidambaram, P.; & Kumarasamy, A. (2024). Antibiofilm Activity of Epinecidin-1 and Its Variants Against Drug-Resistant Candida krusei and Candida tropicalis Isolates from Vaginal Candidiasis Patients. Infect. Dis. Rep, 16, 1214-1229.

- Beynon, R.J., & Bond, J.S. (1989). Proteolytic enzymes: A practical approach. IRL Press at Oxford University Press.

- Nagampalli, R. S. K., Gunasekaran, K., Narayanan, R. B., Peters, A., & Bhaskaran, R. (2014). A structural biology approach to understand human lymphatic filarial infection. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 8(2), e2662. [CrossRef]

- Zanphorlin, L. M., Cabral, H., Arantes, E., Assis, D., Juliano, L., Juliano, M. A., ... & Bonilla-Rodriguez, G. O. (2011). Purification and characterization of a new alkaline serine protease from the thermophilic fungus Myceliophthora sp. Process Biochemistry, 46(11), 2137-2143.

- Damare S, Mishra A, D'Souza-Ticlo-Diniz D, Krishnaswamy A, & Raghukumar C. (2020). A deep-sea hydrogen peroxide-stable alkaline serine protease from Aspergillus flavus. 3 Biotech, 10(12), 528.

- Alagarasan, C., Ramya, K. S., Manohar, R., & Siva, G. V. (2018). PARTIAL PURIFICATION OF CYSTEINE PROTEASE FROM NIGELLA SATIVA L SEEDS.

- Karthik, L., Manohar, R., Elamparithi, K., & Gunasekaran, K. (2019). Purification, characterization and functional analysis of a serine protease inhibitor from the pulps of Cicer arietinum L.(Chick Pea). Indian Journal of Biochemistry and Biophysics (IJBB), 56(2), 117-124..

- Asif-Ullah, M., Kim, K.-S., & Yu, Y.G. (2006). Purification and characterization of a serine protease from Cucumis trigonus Roxburghi. Phytochemistry, 67(9), 870-875.

- Fan, T., Bykova, N.V., Rampitsch, C., & Xing, T. (2016). Identification and characterization of a serine protease from wheat leaves. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 1-12.

- Ahmed, I.A.M., Morishima, I., Babiker, E.E., & Mori, N. (2009). Dubiumin, a chymotrypsin-like serine protease from the seeds of Solanum dubium Fresen. Phytochemistry, 70(4), 483-491. [CrossRef]

- Alici, E. H., & Arabaci, G. (2018). A novel serine protease from strawberry (Fragaria ananassa): Purification and biochemical characterization. International journal of biological macromolecules, 114, 1295-1304.

- Nadaroglu, H., & Demır, N. (2012). Purification and characterization of a novel serine protease compositain from compositae (Scorzonera hispanica L.). European Food Research and Technology, 234, 945-953.48.

- Rawaliya, R. K., Patidar, P., Sharma, S., & Hajela, K. (2022). Purification and biochemical characterization of protease from the seeds of Cyamopsis tetragonoloba. J Appl Biol Biotechnol, 10, 172-180.

- Tomar, R., Kumar, R., & Jagannadham, M. V. (2008). A stable serine protease, wrightin, from the latex of the plant Wrightia tinctoria (Roxb.) R. Br.: purification and biochemical properties. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 56(4), 1479-1487. [CrossRef]

- Mehrnoush, A., Mustafa, S., Sarker, M.Z.I., & Yazid, A.M.M. (2011). Optimization of the conditions for extraction of serine protease from Kesinai Plant (Streblus asper) leaves using response surface methodology. Molecules, 16(11), 9245-9260. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).