1. Introduction

Fruit tree cultivation is a strategic sector of rural economies in Africa, providing essential income for farmers and contributing significantly to food security and the socio-economic development of rural areas. Among the major fruit crops, mango (

Mangifera indica L.) stands out due to its economic value and nutritional benefits, holding a central position in agricultural exports from the continent [

1]. However, the mango sector faces major phytosanitary challenges, particularly infestations by pest insects, with fruit flies being the most damaging, leading to significant yield losses and threatening the sustainability of this crop [

2].

Phytophagous Diptera, particularly fruit flies, pose an increasing threat to fruit production, especially in West Africa. In addition to direct harvest losses, their presence also leads to strict trade restrictions imposed by importing countries, limiting the export of African mangoes [

3].

Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel), or the oriental fruit fly, is one of the most concerning species due to its ability to rapidly infest orchards, with its short reproductive cycle and strong dispersal capacity [

4].

In Senegal,

B. dorsalis has been reported on more than 58 fruit species, particularly in the Niayes region, a key horticultural area. This infestation is particularly problematic as the peak of the insect's proliferation coincides with the mango production period, exacerbating post-harvest losses. Since its detection in 2004, controlling this species has become critical for Senegalese producers, with yield losses ranging from 30 to 60% depending on the production area. This impacts both local and international marketing of mangoes and increases the need for quarantine measures and phytosanitary controls [

5].

In response to this threat, several management strategies have been developed, including the collection of infested fruit [

6,

7,

8], the use of insecticides and protein baits [

9,

10], the installation of attractive traps [

11,

12], the introduction of natural enemies [

13,

14], and the sterile insect technique [

15]. However, the intensive use of pesticides raises concerns due to their harmful effects on human health and the environment [

16,

17], which has led to the search for alternative, eco-friendly solutions, particularly through the use of plant extracts.

Essential oils present a promising approach for managing

B. dorsalis infestations. Some essential oils, particularly those derived from

Syzygium spiceum [

16],

Melaleuca bracteata [

17], and the

Ocimum genus [

17,

18], rich in methyleugenol, have shown strong attractant properties for male

B. dorsalis. In contrast, other oils, such as that of

Pogostemon cablin, have repellent properties [

19], while the essential oil of

Limnophila geoffrayi, with high levels of

d-Pulegone (27.1%) and perillaldehyde (19.1%), exhibits insecticidal effects against

B. dorsalis [

20]. In Senegal, the leaves of

Ocimum americanum, used for several years to control

B. dorsalis, contain 77% methyl eugenol in their essential oil, as revealed by our study [

21].

In this context,

Melaleuca leucadendra, a plant species found in Senegal, is of particular interest due to its essential oil, which is rich in methyleugenol [

22], a compound known for its effectiveness in controlling

B. dorsalis. The aim of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the essential oil from

M. leucadendra. in attracting and eliminating

male B. dorsalis, with the ultimate goal of significantly reducing post-harvest losses and ensuring the production and marketing of Senegalese mangoes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

Samples of M. leucadendra fresh leaves were collected from Fatick-Senegal (14°20’24.99” N, 16°23’1.284'O): The leaves of a sample were taken on the same tree. The plant material was identified by the technicians from the department of botanical of the Fundamental Institute of Black Africa (IFAN) of University Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar.

2.2. Extraction of Essential Oil

Plant material was air-dried for 14 days at room temperature. Samples were hydrodistilled (5h) using a Clevenger-type apparatus according to the method recommended in the European Pharmacopoeia [

23]. The yields of essential oils (w/w, calculated on dry weight basis) were given in the

Table 1.

2.3. GC and GC/MS Analysis

The chromatographic analyses were carried out using a Perkin-Elmer Autosystem XL GC apparatus (Walthon, MA, USA) equipped with dual flame ionisation detection (FID) system and fused-silica capillary columns, namely, Rtx-1 (polydimethylsiloxane) and Rtx-wax (poly-ethyleneglycol) (60 m × 0.22 mm i.d; film thickness 0.25 μm). The oven temperature was programmed from 60 to 230°C at 2°C/min and then held isothermally at 230°C for 35 min: hydrogen was employed as carrier gas (1 mL/min). The injector and detector temperatures were maintained at 280°C, and samples were injected (0.2 μL of pure oil) in the split mode (1:50). Retention indices (RI) of compounds were determined relative to the retention times of a series of n-alkanes (C5–C30) by linear interpolation using the Van den Dool and Kratz (1963) equation with the aid of software from Perkin-Elmer (Total Chrom navigator). The relative percentages of the oil constituents were calculated from the GC peak areas, without application of correction factors.

Samples were also analysed with a Perkin-Elmer Turbo mass detector (quadrupole) coupled to a Perkin-ElmerAutosystem XL, equipped with fused-silica capillary columns Rtx-1 and Rtx-Wax. The oven temperature was programmed from 60 to 230°C at 2°C/min and then held isothermally at 230°C (35 min): hydrogen was employed as carrier gas (1 mL/min). The following chromatographic conditions were employed: injection volume, 0.2 μL of pure oil; injector temperature, 280°C; split, 1:80; ion source temperature, 150°C; ionisation energy, 70 eV; MS (EI) acquired over the mass range, 35–350 Da; scan rate, 1 s.

Identification of the components was based on: (a) comparison of their GC retention indices (RI) on non-polar and polar columns, determined from the retention times of a series of n-alkanes with linear interpolation, with those of authentic compounds or literature data; (b) on computer matching with commercial mass spectral libraries [

24,

25,

26] and comparison of spectra with those of our personal library; and (c) comparison of RI and MS spectral data of authentic compounds or literature data.

2.4. Attractiveness of Essential Oil

2.4.1. Attractiveness of Essential Oil (EO) Compared to Synthetic Methyleugenol (ME)

The study of the comparison between essential oil and synthetic methyleugenol was conducted in Kabar, a village located in Kafountine, in three orchards (KV1, KV2, and KV3), each at least 1 hectare in size. These are traditional orchards, mainly consisting of Kent and Keitt mangoes, with a few citruses occasionally present. The distance between the trees was not consistent. The fallen mangoes were not picked, and the grass cover was dense, with no irrigation. The orchards were not fenced against livestock. The presence of Biofeed feed traps was noted in the third orchard. In the Niayes area, the survey was conducted in Seugheul. The site consisted of three grafted mango orchards, where the Kent and Keitt varieties were dominant. A large number of weeds were present, and sanitation was not applied in the orchards. The irrigation system used was drip irrigation in the SV2 orchard and sprinkler irrigation in the SV1 and SV3 orchards. The experimental design implemented was in randomized dispersed blocks, with an "Attractant factor" consisting of EO and ME treatments, each with three replicates. In each block, three methyl eugenol (ME) traps and three Melaleuca leucadendra essential oil traps were placed, with a dose of 2.5 mL in each. Each trap was provided with a DDVP wafer to kill the captured insects. Tephritraps were used with synthetic methyl eugenol as the reference control. The required amount of essential oil was soaked in hydrophilic cotton. The attractants were renewed after one month of exposure in the traps. The distance between traps was 100 meters to limit interactions between attractants.

2.4.2. Evaluation of the Attractiveness of Different Doses of Essential Oil

The evaluation of the effect of essential oil dose on Tephritidae catches was carried out in Kafountine and Notto in the Niayes. In Kafountine, three orchards (MV1, YV2, and SV3) of 10 hectares, consisting mainly of Kent and Keitt grafted mango trees, were used. The mangoes were not harvested and had not been subjected to phytosanitary treatments.

The effect of different doses of essential oil was studied in these orchards. The Notto site consisted of three orchards, two of which were contiguous (NV2 and NV3). These orchards mainly consisted of grafted mango trees over 4 years old. Phytosanitary treatments had not been applied in these orchards. The fallen mangoes were collected and incinerated in all the orchards.

Thirty-six traps were placed at this site, with 12 traps per orchard. The traps were hung on tree branches at a height of 1.5 m to 1.8 m. To prevent any predatory activity, especially that of red ants, the branches supporting the traps were coated with solid grease on both sides of the attachment points. Four doses of M. leucadendra essential oil were tested: 1.5 mL, 2 mL, 2.5 mL, and 3 mL per trap to determine the optimal dose. Each dose was repeated 3 times in all three orchards. A distance of 100 m was maintained between traps to avoid interactions between doses. Trap surveys were conducted weekly in the morning at a specific time for 16 weeks. The captured flies were placed in bags with the trap number and the name of the orchard and transported to the laboratory for counting and species identification. Tephritrap traps were used with essential oil soaked in cotton wool, accompanied by DDVP insecticide wafers.

2.5. Mesurements

The parameter measured was the number of flies caught per trap. This parameter was expressed as the number of fruit flies per day per trap (FTD). It was calculated using the following formula:

F is the total number of flies; T is the number of traps; D is the number of days of exposure

2.6. Data Processing

The data were subjected to the Shapiro-Wilk normality test to verify their normal distribution. A comparison of capture averages was performed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with R software version 3.6.0. Bonferroni comparison tests were then conducted after ANOVA when the effect of the factors tested was significant at a 95% confidence interval and the 5% significance level.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition of Essential Oils

This essential oil yield, calculated with relative to the mass of dry plant material, was 2.75%. Analysis of the leaf essential oil by GC/FID and GC/MS allowed the identification of 4 compounds accounting 100% of the total composition (

Table 1). Methyleugenol was the main constituent of the essential oil. The richness in methyleugenol of leaf essential oils from

M. leucadendra has also been reported from Australia (99.0%) [

27], Brazil (96.6%) [

28] and Senegal (98.4–99.5%)[

22].

3.2. Attractiveness of Essential Oil

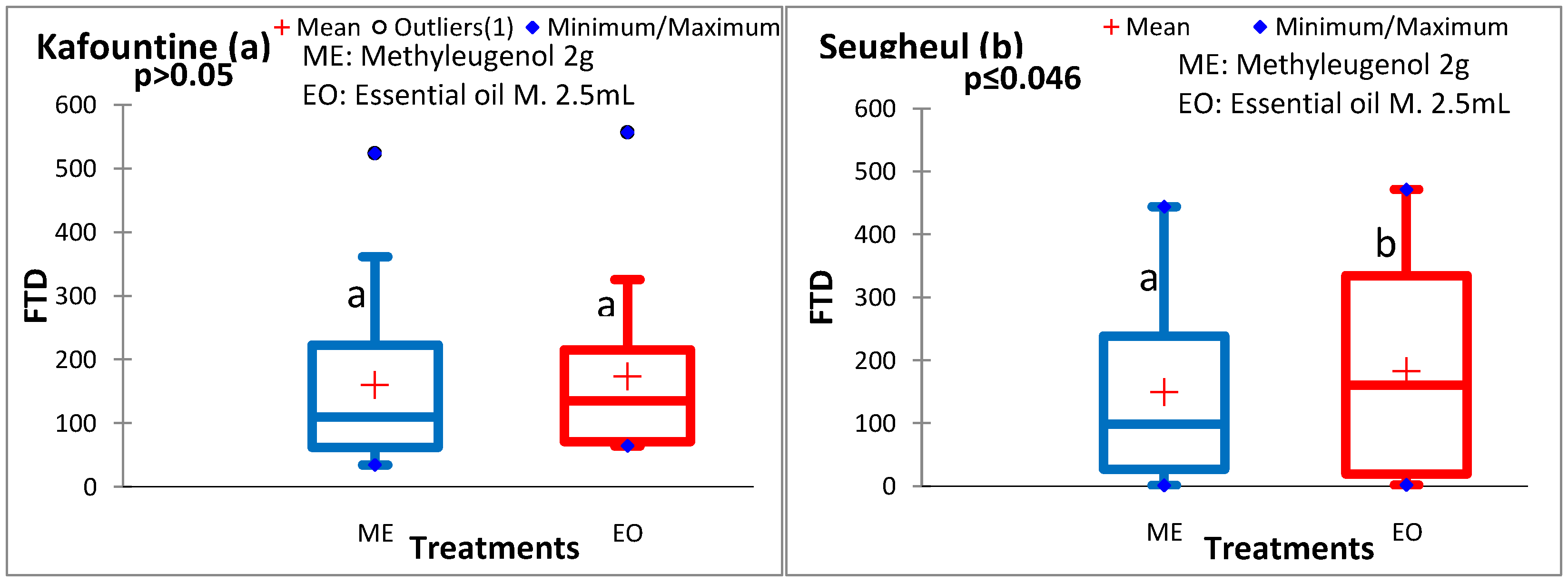

3.2.1. Effect of the Attractant on the Number of Fly Captures

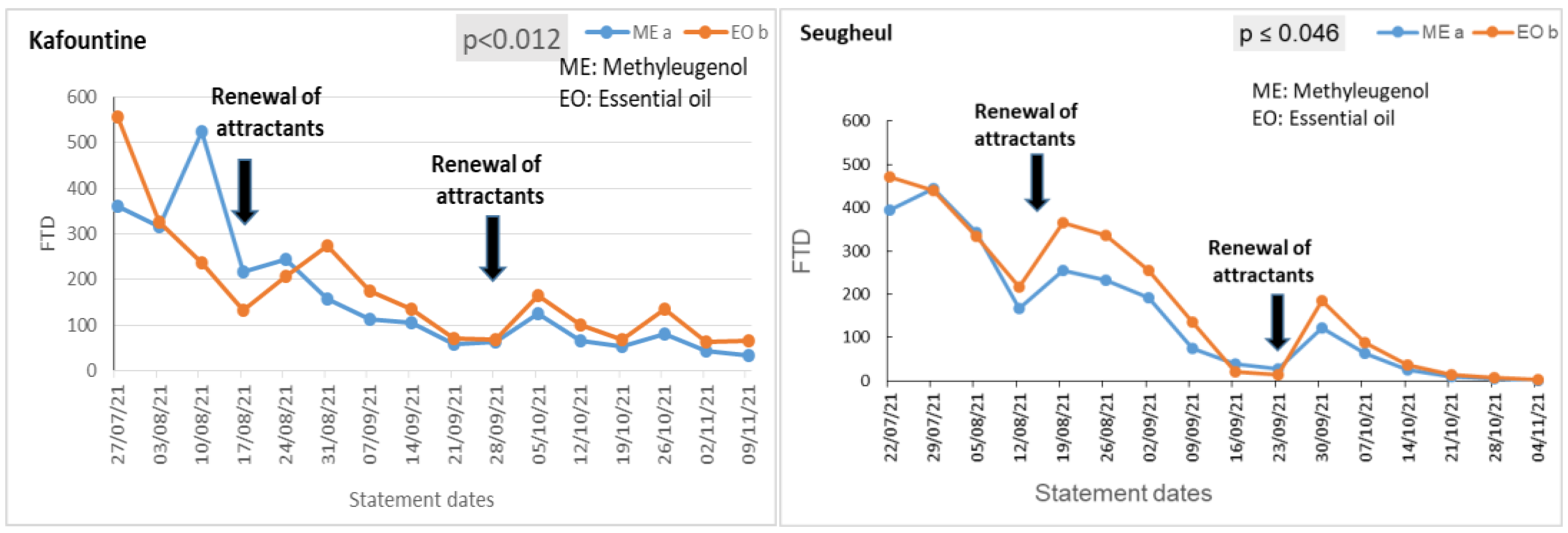

The number of flies caught (FTD) as a function of the two types of attractants was evaluated in both study areas (

Figure 1). In Kafountine, the number of

B. dorsalis captured (FTD) with

M. leucadendra essential oil at a dose of 2.5 ml was 173.75 flies/day/trap. These fly captures were higher than those recorded with synthetic methyleugenol, which reached 160.29 flies/day/trap. This indicates a statistically non-significant difference between catches with essential oil and methyleugenol (p > 0.05). However, in Niayes, the number of flies caught per trap per day with

Melaleuca leucadendra essential oil was 182.62 flies, while the trap with synthetic methyleugenol caught 149.65 flies/day/trap. A statistically significant difference was noted between catches with EO and ME (p ≤ 0.046).

Nevertheless, the number of flies caught with

M. leucadendra essential oil was greater than that with synthetic methyleugenol. Studies conducted by [

29] showed larger captures of

B. dorsalis (226 flies) at a dose of 0.2 mL with

Ocimum sanctum essential oil, which contained 82.29% methyleugenol. Chemical analysis revealed that 40% of the essential oil of

O. sanctum was composed of methyleugenol, based on an experiment conducted in the mango orchard from December 2016 to May 2017 in Kapur, India. The attractive effect of all parts of the

O. sanctum plant was tested on

B. dorsalis. The results showed that the maximum number of standard fruit flies was attracted by basil leaf extract, with an average of 12.67 flies, followed by stems (8.67 flies), inflorescences (10.67 flies), roots (10.33 flies), and synthetic methyleugenol, which attracted an average of 127 fruit flies [

30].

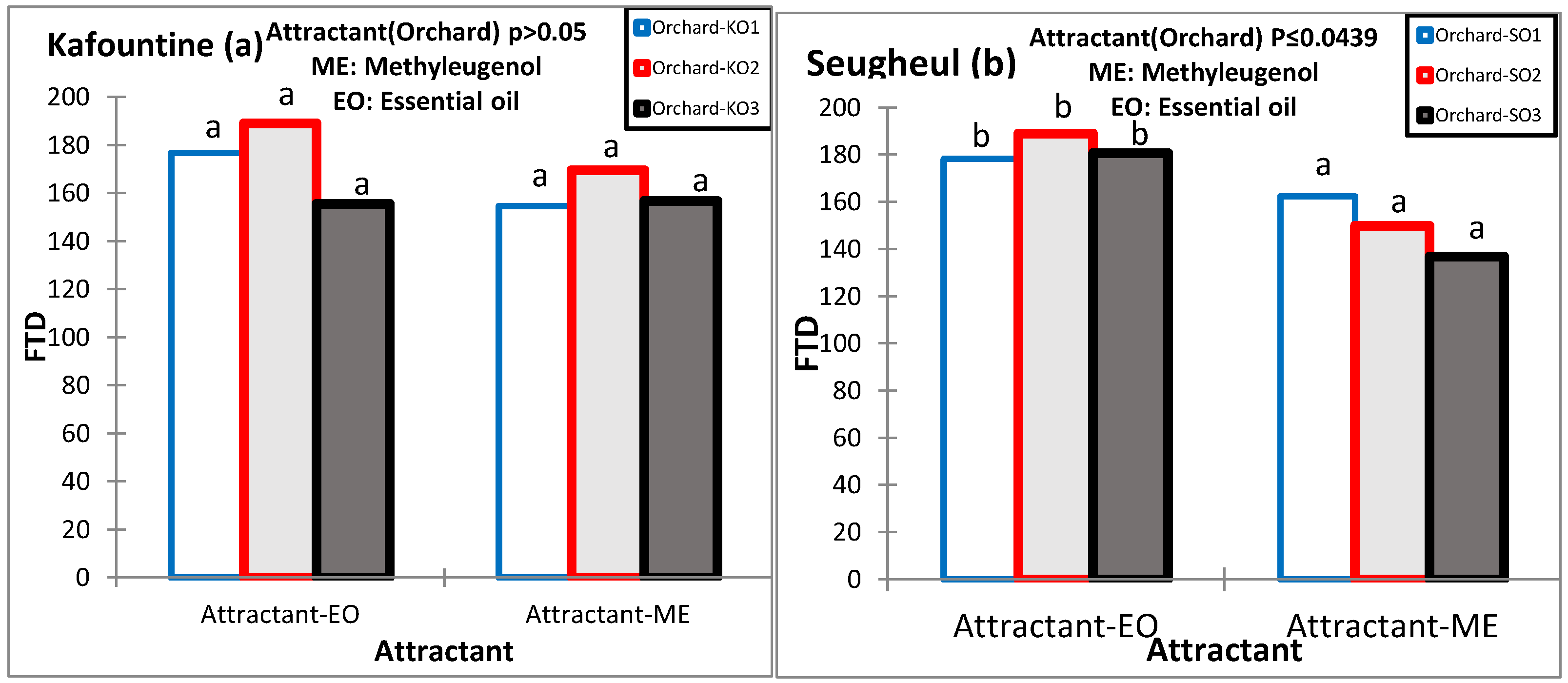

3.2.2. Attractive Power of Essential Oil

The results in

Figure 2 show the attractiveness of essential oil and methyleugenol in orchards. Fly captures were 154.51, 169.62 and 156.75 flies/day/trap in orchards KO1, KO2, and KO3 with methyleugenol, and 176.76, 189.01 and 155.49 flies/day/trap in the same orchards KO1, KO2, and KO3, respectively, with essential oil in Kafountine. These data show a statistically non-significant interaction between the attractant and the orchards. The effect of the attractant on FTD varied between orchards. Moreover, in Seugheul, the attractive power of the essential oil was 178.16, 189 and 180.72 flies/day/trap in orchards SO1, SO2, and SO3, respectively, compared to 162.25, 149.91 and 136.8 flies/day/trap in the same orchards SO1, SO2 and SO3 with methyleugenol. The analysis conducted on these data shows a non-significant interaction between the attractant and the orchards. A similar study was conducted in Sri Lanka. The species

Ocimum tenuiflorum (MT1 purple and MT2 purple-green) grown in Sri Lanka has a methyleugenol content of 72.50% for MT1 and 64.23% for MT2. Bioassays performed on MT1, MT2 essential oils, and synthetic metyleugenol demonstrated that the attractiveness of

B. dorsalis from MT1 essential oil (106 ± 8.1), MT2 essential oil (104 ± 2), and commercial methyleugenol (111 ± 8.5) was not significantly different. [

31].

3.2.3. Abundance of Fruit Fly Populations in Orchards

Population dynamics of

B. dorsalis in the Kafountine and Seugheul orchards showed that the highest peak catches were obtained from July to August, and the lowest from September to October. From the first to the fourth week,

M. leucadendra essential oil caught 556 to 131 flies in Kafountine and 417 to 217 flies in Seugheul. For synthetic methyleugenol, it was 361 to 224 flies, with an increase in catch during the third week, from 141 to 524 flies in Kafountine and from 168 to 395 flies in Seugheul. From the fifth to the tenth week, catches increased after product renewal in the fourth week, with a decrease noted in the tenth week. For essential oil, catches ranged from 273 to 67 flies in the orchards of Kafountine and from 370 to 3 flies in Seugheul. For synthetic methyleugenol, it was 215 to 63 flies in Kafountine and 255 to 5 flies in Seugheul. From the eleventh to the sixteenth week, an increase in catches was noted in the eleventh week after product renewal in the tenth week, followed by a gradual decrease in fly catches until the sixteenth week. The number of flies caught by

M. leucadendra essential oil and synthetic methyleugenol was higher in July-August and lower in October and November. This finding is consistent with those of [

32,

33,

34] which showed peaks and

B. dorsalis damage recorded in July and August. The high proliferation of fruit flies can be explained by the maturity of many mango varieties and the emergence of generations of pupae that evolved on the young fruits that fell under the crowns of mango trees during this period [

35].

B. dorsalis is very abundant during the rainy season, which coincides with the mango ripening period in areas where it has been [

36,

37,

38]. Added to this is the intensity of the rain and the ripening of other mango varieties. Vayssieres et al., (2008 ; 2009)[

39,

40] reported that

B. dorsalis is a species that grows best in conditions of high humidity. According to Ouedraogo (2007) [

41], humidity affects the abundance of Tephritidae populations through the reduction of fecundity of females during dry periods and by the high mortality of newly emerged adults in dry conditions. Humidity influences fluctuations in fruit fly populations during host plant fruiting periods [

42]. The synchronization of fruiting time and abiotic factors (rainfall, temperature, and humidity) is essential for fruit fly population dynamics [

43]. This would explain the higher abundance of flies in Kafountine, with 336,730 individuals captured, compared to 334,948 individuals in Seugheul, because it rains more in the south than in the Niayes area.

The duration of effectiveness of essential oils is four weeks in mango orchards. This result corroborates that of [

44] which showed an efficacy of four weeks in mango orchards in Djibélor. In contrast, Kardinan et al. (1980) [

45] showed a two-week efficacy with

M. bracteata in star fruit and guava orchards. This difference in the duration of effectiveness can be explained by the amount of methyl eugenol in the essential oil, which is 76% in

M. bracteata and 99.5% in

M. leucadendra. Indeed, [

45] showed that the efficacy duration of the product is longer if the percentage of methyl eugenol is greater. Also, the amount of methyl eugenol is decreased by environmental factors (temperature, humidity, and wind), which cause it to evaporate over time [

46].

Figure 3.

Population dynamics captured in the Kafountine and Seugheul orchards.

Figure 3.

Population dynamics captured in the Kafountine and Seugheul orchards.

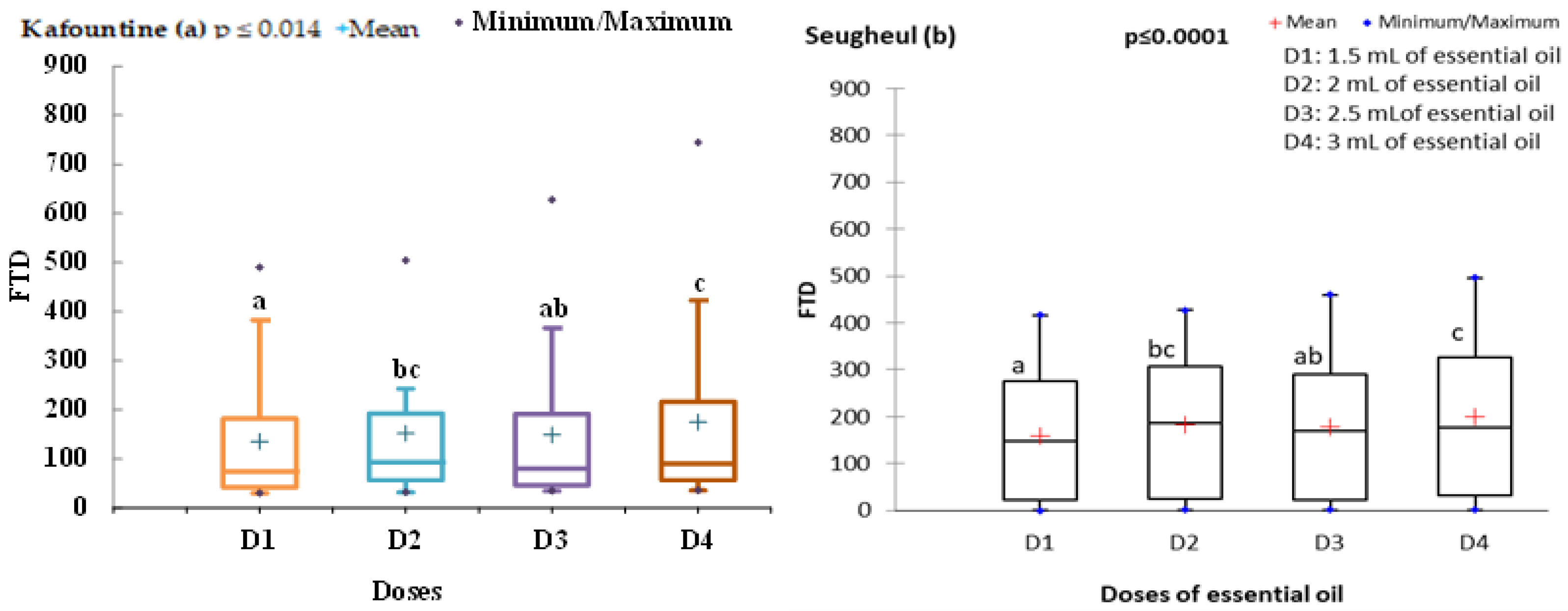

3.2.4. Effect of Different Doses of Essential Oil in Orchards

At Kafountine the number of flies caught was high with D4 (174 flies/trap/day), followed by D2 (151 flies/trap/day), then D3 (148 flies/trap/day) and finally D1 (135 flies/trap/day) (

Figure 4). The highest catches were obtained with the D4 dose (174) and the lowest with the D1 dose (135 flies/day/trap) (

Figure 4). At Seugheul, the catches obtained with Dose 1 (159.72) were lower than those with doses D2 (182.89 flies/day/trap), D3 (176.75 flies/trap/day), and D4 (200.26 flies/trap/day), with a significant difference between dose D1 and the other doses (D2 and D4) at p<0.05. However, there was no significant difference between doses D1 and D3 (p>0.05). In the set of catches with the different doses of

M. leucadendra, the number of catches increased with the doses. This result is consistent with that of [

47]

], where

B. dorsalis catches varied with the amount of methyl eugenol in the mixture. The higher the concentration of

Melaleuca lecadendra oil used, the more fruit flies are trapped, and the greater the amount of methyleugenol that evaporates.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the essential oil of M. leucadendra, rich in methyl eugenol, is an effective alternative to synthetic attractants for trapping B. dorsalis. Trials conducted in the orchards of Kafountine and Seugheul confirmed its strong attractiveness, comparable to or even superior to synthetic methyl eugenol. The application of 3 ml per trap proved to be optimal. This agroecological approach reduces the use of chemical pesticides, thereby preserving health and the environment. Its integration into a sustainable fruit fly control strategy is promising. Further studies are needed to assess its large-scale effectiveness and cost-effectiveness for producers.

Author Contributions

Y.T., SN. CS., J.D, A.A.C.S., A.W., J.C., O.N. designed and coordinated the study. Y.T., A.D., C.G., A.W., JC., CS. carried out the extraction and chemical characterization of essential oils. S.N., CS., JD., A.S., O.N. evaluated the antifungal activity of these oils. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was funded by SyRIMAO/ECOWAS Project. The APC was funded by SyRIMAO/ECOWAS Project.

Acknowledgments

We thank the SyRIMAO/ECOWAS Project for its financial and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Diatta, P.; Rey, J.-Y.; Vayssieres, J.-F.; Diarra, K.; Coly, E.V.; Lechaudel, M.; Grechi, I.; Ndiaye, S.; Ndiaye, O. Fruit Phenology of Citruses, Mangoes and Papayas Influences Egg-Laying Preferences of Bactrocera Invadens (Diptera: Tephritidae). Fruits 2013, 68, 507–516. [CrossRef]

- N’Dépo, O.R.; Hala, N.; Allou, K.; Aboua, L.R.; Kouassi, K.P.; Vayssières, J.-F.; De Meyer, M. Abondance des mouches des fruits dans les zones de production fruitières de Côte d’Ivoire : dynamique des populations de Bactrocera invadens (Diptera : Tephritidae). Fruits 2009, 64, 313–324. [CrossRef]

- Vannière, H.; Didier, C.; Rey, J.-Y.; Diallo, T.M.; Kéita, S.; Sangaré, M. La mangue en Afrique de l’Ouest francophone : les systèmes de production et les itinéraires techniques. Fruits 2004, 59, 383–398. [CrossRef]

- Nugnes, F.; Russo, E.; Viggiani, G.; Bernardo, U. First Record of an Invasive Fruit Fly Belonging to Bactrocera Dorsalis Complex (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Europe. Insects 2018, 9, 182. [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, O.; Vayssieres, J.-F.; Rey, J.Y.; Ndiaye, S.; Diedhiou, P.M.; Ba, C.T.; Diatta, P. Seasonality and Range of Fruit Fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) Host Plants in Orchards in Niayes and the Thiès Plateau (Senegal). Fruits 2012, 67, 311–331. [CrossRef]

- Salmah, M.; Adam, N.A.; Muhamad, R.; Lau, W.H.; Ahmad, H. Infestation of Fruit Fly, Bactrocera (Diptera: Tephritidae) on Mango (Mangifera Indica L.) in Peninsular Malaysia. Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences 2017, 9, 799–812. [CrossRef]

- Verghese, A.; Tandon, P.L.; Stonehouse, J.M. Economic Evaluation of the Integrated Management of the Oriental Fruit Fly Bactrocera Dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Mango in India. Crop Protection 2004, 23, 61–63. [CrossRef]

- Verghese, A.; Sreedevi, K.; Nagaraju, D.K. Pre and Post Harvest IPM for the Mango Fruit Fly, Bactrocera Dorsalis (Hendel). 2006.

- Vayssieres, J.-F.; Sinzogan, A.; Korie, S.; Ouagoussounon, I.; Thomas-Odjo, A. Effectiveness of Spinosad Bait Sprays (GF-120) in Controlling Mango-Infesting Fruit Flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Benin. Journal of economic entomology 2009, 102, 515–521. [CrossRef]

- Kibira, M.; Affognon, H.; Njehia, B.; Muriithi, B.; Mohamed, S.; Ekesi, S. Economic Evaluation of Integrated Management of Fruit Fly in Mango Production in Embu County, Kenya. African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 2015, 10, 343–353.

- Ugwu, J.A. Efficacy of Methyl Eugenol and Food-Based Lures in Trapping Oriental Fruit Fly Bactrocera Dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) on Mango Homestead Trees. International Journal of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering 2019, 13, 309–313.

- Ballo, S.; Demissie, G.; Tefera, T.; Mohamed, S.A.; Khamis, F.M.; Niassy, S.; Ekesi, S. Use of Para-Pheromone Methyl Eugenol for Suppression of the Mango Fruit Fly, Bactrocera Dorsalis (Hendel)(Diptera: Tephritidae) in Southern Ethiopia. Sustainable management of invasive pests in Africa 2020, 203–217.

- Vargas, R.I.; Leblanc, L.; Putoa, R.; Eitam, A. Impact of Introduction of Bactrocera Dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) and Classical Biological Control Releases of Fopius Arisanus (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) on Economically Important Fruit Flies in French Polynesia. Journal of economic entomology 2007, 100, 670–679.

- Gnanvossou, D.; Hanna, R.; Bokonon-Ganta, A.H.; Ekesi, S.; Mohamed, S.A. Release, Establishment and Spread of the Natural Enemy Fopius Arisanus (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) for Control of the Invasive Oriental Fruit Fly Bactrocera Dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Benin, West Africa. Fruit Fly Research and Development in Africa-Towards a Sustainable Management Strategy to Improve Horticulture 2016, 575–600.

- Reddy, P.V.; Rashmi, M.A. Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) as a Component of Area-Wide Integrated Management of Fruit Flies: Status and Scope. Pest Management in Horticultural Ecosystems 2016, 22, 1–11.

- Hu, Z.-J.; Yang, J.-W.; Chen, Z.-H.; Chang, C.; Ma, Y.-P.; Li, N.; Deng, M.; Mao, G.-L.; Bao, Q.; Deng, S.-Z. Exploration of Clove Bud (Syzygium Aromaticum) Essential Oil as a Novel Attractant against Bactrocera Dorsalis (Hendel) and Its Safety Evaluation. Insects 2022, 13, 918. [CrossRef]

- Kardinan, A.K.; Hidayat, P. Potency of Melaleuca Bracteata and Ocimum Sp. Leaf Extractsas Fruit Fly (Bactrocera Dorsalis Complex) Attractants in Guava and Star Fruit Orchards in Bogor, West Java, Indonesia. Journal of Developments in Sustainable Agriculture 2013, 8, 79–84.

- Dharmadasa, R.M.; Siriwardhane, D.A.S.; Samarasinghe, K.; Rangana, S.; Nugaliyadda, L.; Gunawardane, I.; Aththanayake, A.M.L. Screening of Two Ocimum Tenuiflorum L.(Lamiaceae) Morphotypes for Their Morphological Characters, Essential Oil Composition and Fruit Fly Attractant Ability. World J. Agric. Res 2015, 3, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Sari, D.E.; Sulfiani, N. Effect of Camphor and Patchouli Oil to Control Fruit Fly Pest (Bactrocera Sp.) on Chillies (Capsicum annum L.). 2022. [CrossRef]

- Thongdon-A, J.; Inprakhon, P. Composition and Biological Activities of Essential Oils from Limnophila Geoffrayi Bonati. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2009, 25, 1313–1320. [CrossRef]

- Tine, Y.; Sinzogan, A.A.C.; Ndiaye, O.; Sambou, C.; Diallo, A.; Mbenga, I.; Badji, K.; Dieng, E.H.O.; Balayara, A.; Diatta, J. The Essential Oil of Ocimum Americanum from Senegal and Gambia as a Source of Methyleugenol for the Control of Bactrocera Dorsalis, Fruit Fly. Journal of Agricultural Chemistry and Environment 2023, 13, 133–141. [CrossRef]

- Diallo, A.; Tine, Y.; Sène, M.; Diagne, M.; Diop, A.; Ngom, S.; Ndoye, I.; Boye, C.S.B.; Sy, G.Y.; Costa, J.; et al. The Essential Oil of Melaleuca Leucadendra L. (Myrtaceae) from Fatick (Senegal) as a Source of Methyleugenol. Composition, Antibacterial and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Journal of Essential Oil Research 2022, 34, 322–328. [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. European Pharmacopoeia.; 3rd ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, 1997; ISBN 978-92-871-2991-8.

- Joulain, D.; König, W.A. The Atlas of Spectral Data of Sesquiterpene Hydrocarbons; EB-Verlag, 1998;

- Adams, R.P.; others Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry.; Allured publishing corporation, 2007;

- NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology), N. PC Version of the NIST/EPA/NIH Mass Spectra Library. Available online: http://www.nist.gov/srd/nist1a.cfm (accessed on 4 July 2016).

- Brophy, J.J.; Lassak, E.V. Melaleuca Leucadendra L. Leaf Oil:Two Phenylpropanoid Chemotypes. Flavour and Fragrance Journal 1988, 3, 43–46. [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.J.; Barbosa, L.C.A.; Maltha, C.R.A.; Pinheiro, A.L.; Ismail, F.M.D. Comparative Study of the Essential Oils of Seven Melaleuca (Myrtaceae) Species Grown in Brazil. Flavour and Fragrance Journal 2007, 22, 474–478. [CrossRef]

- Susanto, A.; Subahar, T.S.S. Response of Fruit Fly, Bactrocera Dorsalis Complex on Methyl Eugenol Derived from Basil Plant, Ocimum Sanctum L. 2008, 5.

- Singh, S.P.; Agrawal, N.; Singh, R.K.; Singh, S. Management of Fruit Flies in Mango, Guava and Vegetables by Using Basil Plants (Ocimum Sanctum L.) as Attractant. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2019, 4.

- Dharmadasa, R.M.; Siriwardhane, D.A.S.; Samarasinghe, K.; Rangana, S.H.C.S.; Nugaliyadda, L.; Gunawardane, I.; Aththanayake, A.M.L. Screening of Two Ocimum Tenuiflorum L. (Lamiaceae) Morphotypes for Their Morphological Characters, Essential Oil Composition and Fruit Fly Attractant Ability. WJAR 2015, 3, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, S.; Diédhiou, P.M.; Ndiaye, O.; Rey, Y.; Mbaye, N.; Ballayéra, A.; Touré, T. Dynamique des populations, tests d’attractivité, de contrôle dans des vergers de la zone de Niayes (06 – 11/2008). 2008.

- Konta, I.S.; Djiba, S.; Sane, S.; Diassi, L.; Ndiaye, A.B.; Noba, K. Etude de la dynamique de Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae) dans les vergers de mangues en Basse Casamance : influence des facteurs climatiques. Int. J. Bio. Chem. Sci 2016, 9, 2698. [CrossRef]

- Boinahadji, A.K.; Coly, E.V.; Dieng, E.O.; Diome, T.; Sembene, P.M. Interactions between the Oriental Fruit Fly Bactrocera Dorsalis (Diptera, Tephritidae) and Its Host Plants Range in the Niayes Area in Senegal. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2019.

- Konta, I.S.; Djiba, S.; Sane, S.; Diassi, L.; Ndiaye, A.B.; Noba, K. Etude de La Dynamique de Bactrocera Dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae) Dans Les Vergers de Mangues En Basse Casamance : Influence Des Facteurs Climatiques. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences 2015, 9, 2698–2715. [CrossRef]

- Mwatawala, M.W.; De Meyer, M.; Makundi, R.H.; Maerere, A.P. Biodiversity of Fruit Flies (Diptera, Tephritidae) in Orchards in Different Agro-Ecological Zones of the Morogoro Region, Tanzania. Fruits 2006, 61, 321–332. [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo, S.N.; Vayssières, J.-F.; Rémy Dabiré, A.; Rouland-Lefèvre, C. Biodiversité des mouches des fruits (Diptera : Tephritidae) en vergers de manguiers de l’ouest du Burkina Faso : structure et comparaison des communautés de différents sites. Fruits 2011, 66, 393–404. [CrossRef]

- Vayssières, J.-F.; Sinzogan, A.; Adandonon, A.; Rey, J.-Y.; Dieng, E.O.; Camara, K.; Sangaré, M.; Ouedraogo, S.; Hala, N.; Sidibé, A.; et al. Annual Population Dynamics of Mango Fruit Flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in West Africa: Socio-Economic Aspects, Host Phenology and Implications for Management. Fruits 2014, 69, 207–222. [CrossRef]

- Vayssieres, J.-F.; Korie, S.; Coulibaly, O.; Temple, L.; Boueyi, S.P. The Mango Tree in Central and Northern Benin: Cultivar Inventory, Yield Assessment, Infested Stages and Loss Due to Fruit Flies (Diptera Tephritidae). Fruits 2008, 63, 335–348. [CrossRef]

- Vayssières, J.-F.; Korie, S.; Ayegnon, D. Correlation of Fruit Fly (Diptera Tephritidae) Infestation of Major Mango Cultivars in Borgou (Benin) with Abiotic and Biotic Factors and Assessment of Damage. Crop protection 2009, 28, 477–488. [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo, S. Etude Des Attaques Des Mouches Des Fruits (Diptera: Tephritidae) Sur La Mangue Dans La Province Du Kénédougou (Ouest Du Burkina Faso). Mémoire de diplôme d’étude approfondie (DEA) en gestion intégrée des Ressources naturelles (GIRN) à l’Institut du développement Rural (IDR) de l’Université Polytechnique de Bobo-Dioulasso (UPB) 2007.

- Tan, K.-H.; Serit, M. Adult Population Dynamics of Bactrocera Dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Relation to Host Phenology and Weather in Two Villages of Penang Island, Malaysia. Environmental Entomology 1994, 23, 267–275. [CrossRef]

- Vayssières, J.-F.; Korie, S.; Ayegnon, D. Correlation of Fruit Fly (Diptera Tephritidae) Infestation of Major Mango Cultivars in Borgou (Benin) with Abiotic and Biotic Factors and Assessment of Damage. Crop Protection 2009, 28, 477–488. [CrossRef]

- Sambou, C. Attractivité des huiles essentielles de Melaleuca leucadendra Linn. (Myrtaceae) et Zanthoxylum zanthoxyloides (Lam.) (Rutaceae) vis-à-vis de Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera, Tephritidae) dans des vergers de manguiers à Djibélor en Casamance. 2020, 40.

- Kardinan, A.K.; Hidayat, P. Potency of Melaleuca Bracteata and Ocimum Sp. Leaf Extracts as Fruit Fly (Bactrocera Dorsalis Complex) Attractants in Guava and Star Fruit Orchards in Bogor, West Java, Indonesia. 2013.

- Shaver, T.; Bull, D. Environmental Fate of Methyl Eugenol. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 1980, 24, 619–626.

- Vargas, R.I.; Stark, J.D.; Kido, M.H.; Ketter, H.M.; Whitehand, L.C. Methyl Eugenol and Cue-Lure Traps for Suppression of Male Oriental Fruit Flies and Melon Flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Hawaii: Effects of Lure Mixtures and Weathering. ec 2000, 93, 81–87. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).