1. Introduction

Neuroscience has undergone a paradigm shift in understanding the cellular composition of the brain. For decades, it was often repeated that glial cells outnumber neurons by at least 10:1 in the human brain. This notion has been debunked in recent years: the adult human brain contains on the order of 86 billion neurons and a roughly equal number of glial (non-neuronal) cells (von Bartheld et al., 2016). The myth of one trillion glia (and a 10:1 ratio) arose from misinterpretations of early data and was propagated in textbooks (von Bartheld et al., 2016). Modern stereological counts and the isotropic fractionator method introduced by Herculano-Houzel and colleagues have provided more accurate estimates. For example, Azevedo et al. (2009) found ~86 billion neurons and ~85 billion nonneuronal cells in the human brain, an overall glia/neuron ratio of approximately 1:1. This finding reframed the human brain not as an outlier with excess glia, but as an “isometrically scaled-up primate brain” in terms of cellular composition (Azevedo et al., 2009).

Crucially, while the total numbers are roughly equal, the glia/neuron ratio is far from uniform within the brain or across species. Herculano-Houzel (2014) synthesized cross-species data and revealed that glia/neuron ratios vary systematically: they increase not as a simple function of brain size but inversely with neuronal density. In other words, brain structures or species with more densely packed neurons tend to have lower glial support per neuron, whereas structures or species with larger neurons (hence lower packing density) have higher glia per neuron (Herculano-Houzel, 2014). This scaling rule appears to hold across mammalian brains from mice to primates that diverged over 90 million years ago (Herculano-Houzel, 2014), pointing to a fundamental evolutionary constraint or design principle. The glia/neuron ratio thus encapsulates how brains allocate supportive glial cells relative to neurons under varying constraints of size, density, and metabolic demand.

Why Does This Ratio Matter?

Neurons are often termed the “information-processing” cells, but they do not operate in isolation. Glial cells – astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, and NG2 glia – are now understood to be indispensable partners to neurons, contributing to virtually every aspect of brain function. An adequate number of glia per neuron is required for metabolic support (e.g., supplying nutrients and oxygen, removing waste), maintaining extracellular homeostasis (ion and neurotransmitter balance), myelination of axons for efficient signal conduction, and modulating synaptic activity and plasticity. One may only imagine the consequences of this to information exchange between the brain and the environment, something that we are still far from understand, but close to apply in Artificial Intelligence (Montgomery, 2025). As new roles of glia continue to be discovered, researchers have proposed that the glia/neuron ratio in a given brain region might influence that region’s computational capacity, plasticity, and resilience to stress or injury (Elsayed & Magistretti, 2015). Indeed, increased glial densities are associated with higher brain functional complexity across species (Elsayed & Magistretti, 2015). It has even been hypothesized that the evolution of human cognitive abilities was not only a story of adding more neurons, but also upgrading glial support, with human astrocytes showing unique attributes compared to those of smaller-brained mammals (Oberheim et al., 2009). The conclusion that a serious neuroscientist takes of this is that there is no excuse to study the central nervous system without accounting for the glial cells, with the evident risk of writing an antiquate understanding of brain functions.

This article explores the functional significance of the glia/neuron ratio, building on Herculano-Houzel (2014) and incorporating research from 2014 onward. We first compare glia/neuron ratios across species and brain regions, highlighting patterns and evolutionary interpretations. We then examine how varying glia/neuron ratios relate to brain physiology – specifically metabolic support and plasticity – and how glia contribute to cognitive function and behavior. Functional roles of different glial types are discussed, including astrocytic support of synapses and blood flow, oligodendrocyte myelination and metabolism, and microglial roles in circuit refinement and immunity. We also review evidence that disturbances in neuron-glia proportions or glial function are linked to diseases (from neurodevelopmental to neurodegenerative and psychiatric conditions). Throughout, we cite recent peer-reviewed studies that illuminate why the brain’s glia/neuron ratio matters for both normal function and pathology. In doing so, we aim to paint a comprehensive, up-to-date picture of how glia/neuron ratios have shaped brain evolution and continue to impact brain health.

(No experimental Methods were employed, as this is a synthesis of published literature. Instead, relevant methodological advances (such as cell counting techniques) are discussed within the text where appropriate.)

2. Discussion

2.1. Interspecies Comparisons and Brain Regional Variations in Glia/Neuron Ratio

Early neuroanatomists noted that larger brains tend to appear “glia-richer” than smaller brains, an observation now quantifiable through comparative studies. Herculano-Houzel (2014) demonstrated that the glia/neuron ratio does not simply rise with brain size, but correlates strongly with average neuronal cell size and inversely with neuronal density. This means species with larger neurons (often in larger brains) allocate more glia per neuron. For example, rodents with small brains have very densely packed neurons and relatively fewer glia per neuron, whereas primates (and especially humans) with larger neurons have more glia per neuron on average (Elsayed & Magistretti, 2015). Notably, these differences are evident even within a single brain: the cerebellum, which contains an enormous number of small granule neurons packed at high density, has a much lower glia/neuron ratio than the cerebral cortex, which contains fewer, larger neurons.

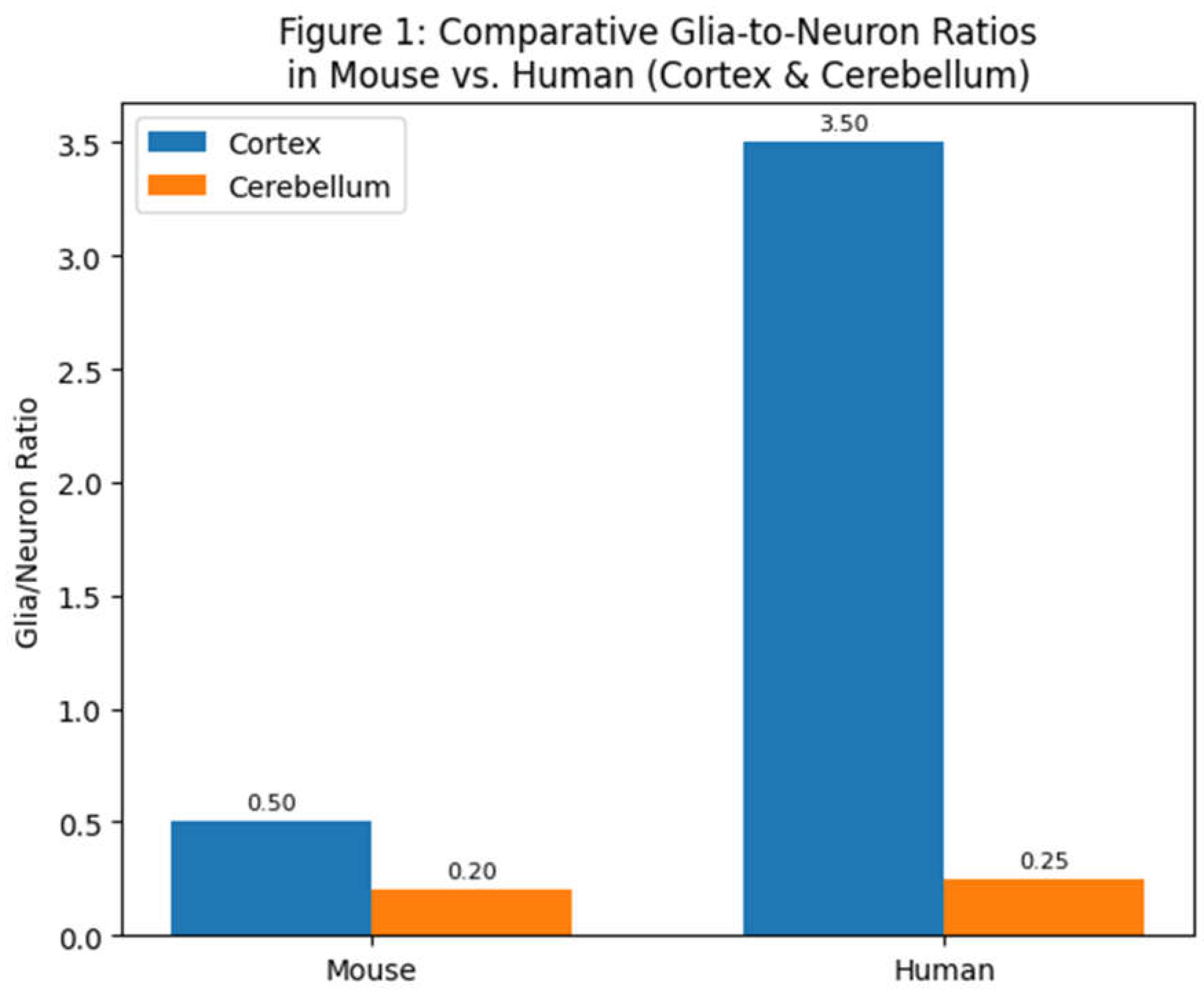

Figure 1.

Comparative glia-to-neuron ratios in two brain structures (cerebral cortex and cerebellum) of a small rodent (mouse) versus a human. The human cortex contains several-fold more glia per neuron than the mouse cortex, whereas both species’ cerebella have low glia/neuron ratios due to the extremely high density of cerebellar neurons (most of which are small granule cells). Data are drawn from cell-counting studies (Azevedo et al., 2009; Williams, 2000).

Figure 1.

Comparative glia-to-neuron ratios in two brain structures (cerebral cortex and cerebellum) of a small rodent (mouse) versus a human. The human cortex contains several-fold more glia per neuron than the mouse cortex, whereas both species’ cerebella have low glia/neuron ratios due to the extremely high density of cerebellar neurons (most of which are small granule cells). Data are drawn from cell-counting studies (Azevedo et al., 2009; Williams, 2000).

In humans, the cerebral cortex houses only ~19% of the brain’s neurons but about ~72% of the brain’s glial cells (Azevedo et al., 2009). This yields a glia/neuron ratio in the human cortex on the order of 3–4:1, indicating roughly three to four glial cells for each cortical neuron. By contrast, the human cerebellum contains ~80% of all neurons but only ~19% of glial cells (Azevedo et al., 2009) – a glia/neuron ratio of only about 0.2–0.3 (glia per neuron). These stark regional differences reflect the different cellular architecture and metabolic needs: cerebellar granule neurons are tiny and energetically inexpensive, allowing many neurons per glia, whereas cortical neurons are larger, more complex, and require more support. In the “rest of brain” (subcortical structures such as brainstem, diencephalon, etc.), neuron densities are low and neurons often large, and accordingly glia/neuron ratios can be high (estimates suggest >10:1 in the human brainstem [Azevedo et al., 2009]).

Across species, similar patterns hold. A mouse brain (~0.4 grams) contains on the order of 7.5×107 neurons and about 2.3×107 glial cells (Williams, 2000), for an overall ratio of ~0.3 glia per neuron. In a much larger primate brain like that of humans (~1.5 kg, with ~8.6×1010 neurons), the overall ratio is ~1.0 (von Bartheld et al., 2016). In an elephant cerebral cortex (which has exceptionally large neurons), published data indicate a glia/neuron ratio around 1.8 (Herculano-Houzel, 2014). These comparisons reinforce that as brains increase in size and neurons become larger and more sparsely distributed, glial cell numbers increase proportionally. Evolution seems to have maintained a balance such that each neuron – regardless of species – is provided with an adequate glial entourage. Indeed, Herculano-Houzel (2014) found a remarkably uniform relationship: brain structures from mice, guinea pigs, monkeys, and humans all fall along the same curve relating neuronal density to glia/neuron ratio. This suggests that the neuron-glia partnership was optimized early in mammalian evolution and conserved thereafter. In essence, neurons do not scale up in size or number without commensurate scaling of glial support, underlining how fundamental glia-neuron interactions are for brain function.

2.2. Why Would Larger or Sparsely Distributed Neurons Need More Glia?

One intuitive explanation is metabolic support and signaling distance. Large neurons have extensive dendrites and axons that impose greater energy demands and homeostatic challenges (for example, more synapses to service, larger volumes of cytoplasm to maintain, longer axonal lengths to myelinate). Glial cells, especially astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, fulfill these support roles – providing energy substrates, clearing neurotransmitters, buffering ions, and insulating axons. The uniform scaling of glia with neuron size/density implies that brain physiology has a built-in requirement for a certain glial investment per neuron, likely reflecting metabolic and signaling constraints (Herculano-Houzel, 2014). This principle places the glia/neuron ratio as a crucial factor in brain evolution: one cannot simply add neurons (to increase cognitive capacity, say) without also adding glia to support those neurons. The human brain’s roughly equal numbers of glia and neurons, similar to other primates (Azevedo et al., 2009), indicates that our evolutionary path involved increasing both types of cells in tandem to maintain functional stability.

In summary, interspecies and regional comparisons show that the glia/neuron ratio is a scaling variable that encapsulates differences in neuron size and energetic requirements. Brains as different as a mouse’s and a human’s conform to the same underlying rule – pointing to deep evolutionary conservation. Next, we delve into the functional implications of these differences: how do glia support neurons, and what advantages might a higher glia/neuron ratio confer in terms of physiology, cognition, and adaptability?

2.3. Functional Significance of Glia/Neuron Ratio: Physiology and Metabolism

Glial cells are indispensable for maintaining the brain’s physiological equilibrium. A higher glia/neuron ratio generally means each neuron has more glial partners to help meet its needs. Astrocytes, the most abundant type of glia in grey matter, play a central role in metabolic support. They ensheathe capillaries with endfeet, constituting nearly 99% of the surface of brain microvasculature (Elsayed & Magistretti, 2015). Through this neurovascular coupling, astrocytes regulate blood flow and nutrient delivery in response to neuronal activity (Elsayed & Magistretti, 2015). Astrocytes express glucose transporters (GLUT1) on their endfeet (Magistretti & Allaman, 2018), and when neurons become active and release glutamate, astrocytes take up the glutamate and undergo glycolysis – a process known as the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle (ANLS) (Magistretti & Allaman, 2018). In ANLS, astrocytes metabolize glucose to lactate and then export lactate to neurons as a fuel (Magistretti & Allaman, 2018). This shuttling is not only an energy supply mechanism; lactate has been found to act as a signaling molecule that can enhance neuronal plasticity. Studies have shown that astrocyte-derived lactate is required for long-term memory formation and induces gene expression changes related to learning (Magistretti & Allaman, 2018). Thus, an ample presence of astrocytes (high glia/neuron ratio) in metabolically demanding regions like the cortex ensures a robust support system for active neurons: they can rapidly deliver energy substrates and even modulate plasticity via metabolic signals (Magistretti & Allaman, 2018).This features of astrocytes should be studied more deeply before we reach major conclusions about neurons physiology as an interaction, more that a single neuron to neuron chain neural network.

Another critical function tied to glia is the storage of energy reserves. Astrocytes are the only brain cells that store glycogen. Although the brain’s glycogen levels are small, astrocytic glycogen can be mobilized during intense neuronal activity or glucose scarcity, providing lactate to neurons in need (Magistretti & Allaman, 2018). Neurotransmitters and neuromodulators (e.g., norepinephrine, VIP) can trigger astrocytes to break down glycogen (Magistretti & Allaman, 2018). In regions with a high glia/neuron ratio, neurons may have better access to such emergency energy reserves, potentially contributing to resilience against transient energy deficits. This is particularly relevant for large brains or regions like the human cortex, where energy demand is high and a dense network of astrocytes is on standby to maintain fuel supply.

Glia also maintain the ionic and neurotransmitter environment that neurons require to function properly. Astrocytes buffer extracellular K+ released during action potentials and uptake excess neurotransmitters (e.g., glutamate via astrocytic glutamate transporters GLT-1/GLAST) (Elsayed & Magistretti, 2015). If neurons are densely packed with insufficient astrocytic coverage, potassium and glutamate could accumulate to neurotoxic levels or cause synaptic “crosstalk.” Indeed, the large human cortex with its profuse astrocyte population benefits from efficient clearance of neurotransmitters and regulation of the extracellular milieu. This may be one reason why the cortex cannot simply be scaled up with neurons alone; without proportional astrocyte increase, information processing would be compromised by runaway excitation or energy shortfall. The glia/neuron ratio thus relates to metabolic homeostasis: more and larger astrocytes per neuron improve the precision of ionic control and metabolite exchange, which is essential for sustained high-frequency firing and complex network activity (Herculano-Houzel, 2014).

Beyond astrocytes, oligodendrocytes (the myelinating glia of the CNS) contribute to metabolic efficiency and signaling speed. Oligodendrocytes wrap myelin sheaths around axons, drastically increasing conduction velocity. In large brains, neurons often have long axons; without sufficient oligodendrocytes, signals would be slow and energetically costly. Each oligodendrocyte can myelinate segments of multiple axons, but a certain number are needed to myelinate all long-range fibers (Han et al., 2013). Moreover, recent research reveals that oligodendrocytes provide metabolic support to axons by supplying lactate through myelin, helping to fuel neuronal firing (Verkhratsky et al., 2014). Thus, more oligodendrocytes per neuron can mean better insulated and nourished axons, which is vital in large, complex brains. Interestingly, the NG2 glia (oligodendrocyte progenitor cells) also persist into adulthood and can generate new oligodendrocytes (Verkhratsky et al., 2014). They constitute a portion of the “glial” cell count. In healthy conditions, NG2 cells proliferate and differentiate as needed to maintain myelin; a higher glia/neuron ratio may reflect a reservoir of these progenitors available for plasticity and repair.

In summary, brain regions or species with a high glia/neuron ratio benefit from enhanced metabolic support and homeostatic regulation. Abundant astrocytes secure energy supply lines and create a stable extracellular environment for neurons, while oligodendrocytes ensure rapid, efficient communication along axons. These advantages likely contributed to the evolution of larger brain regions: as neuron number and size expanded, glial support had to upscale to preserve the metabolic equilibrium. The consequences are evident in functional brain imaging: the human brain’s high glial content underlies phenomena like the blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) signal in fMRI, which is largely driven by astrocyte-mediated blood flow responses to neuronal activity. In the next section, we examine how glia also directly participate in information processing and synaptic function, further explaining why evolution has tightly linked glia numbers to neuron numbers.

2.4. Glial Contributions to Synaptic Modulation and Signaling

Once considered mere “glue,” glial cells (especially astrocytes) are now known to actively participate in synaptic communication. The concept of the tripartite synapse captures this: most excitatory synapses in the CNS have a presynaptic neuron, a postsynaptic neuron, and surrounding astrocytic processes that influence synaptic function (Magistretti & Allaman, 2018). Astrocytes express many of the same receptors and ion channels that neurons do (Magistretti & Allaman, 2018), allowing them to sense neurotransmitter release. In response, they can release their own signals – so-called gliotransmitters – such as ATP, D-serine, or even glutamate (Coyle & Schwarcz, 2000). These gliotransmitters modulate neuronal activity; for example, astrocytic D-serine is a critical co-agonist at NMDA receptors necessary for certain forms of synaptic plasticity (Coyle & Schwarcz, 2000). A higher glia/neuron ratio means a greater density of astrocyte processes per synapse, potentially enhancing the regulation of synaptic transmission and plasticity. Indeed, regions like the cortex (with many astrocytes per neuron) exhibit pronounced forms of synaptic plasticity (like long-term potentiation, LTP) that are known to depend on astrocytic function (Oberheim et al., 2009).

Astrocytes also coordinate network-level signaling through interastrocytic calcium waves. They are coupled by gap junctions forming syncytia; a local excitation can spread as a Ca2+ wave through astrocyte networks, modulating activity in adjacent neuronal populations. This form of glial signaling might integrate information across groups of synapses or even across different brain regions. Larger brains with more astrocytes may have greater capacity for such integrative signaling. For instance, human astrocytes are not only larger but propagate calcium signals significantly faster than rodent astrocytes (Oberheim et al., 2009). Faster and more extensive Ca2+ waves in human astrocytes could allow a form of long-range inhibition or priming of neuronal assemblies that simpler brains lack. The evolutionary increase in astrocyte size and complexity (with human astrocytes having up to 10× more processes than mouse astrocytes) (Oberheim et al., 2009) suggests an expansion of these roles. More astrocytic processes per neuron means more points of contact to sense synaptic activity and modulate it. It has been suggested that astrocytes contribute to tuning synaptic circuits, for example by preferentially strengthening or weakening certain connections via local release of growth factors or modulators.

Other glial cell types also influence synapses. Microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells (which make up a smaller fraction of glia), have emerged as key players in synaptic pruning and plasticity. During development, microglia physically engulf and eliminate excess synapses, a process crucial for refining neural circuits. Even in the adult brain, microglia continuously survey the extracellular space (“canvassing” with their motile processes) and can strip away synaptic elements or release cytokines that alter synaptic function (Verkhratsky et al., 2014). A proper neuron-to-microglia ratio is needed to maintain synaptic health; too few microglia might lead to accumulation of faulty synapses, whereas too many or overactive microglia might prune connections excessively. Interestingly, some neurodevelopmental disorders like autism and schizophrenia have been linked to dysregulated synaptic pruning by microglia. Postmortem studies in autism have found increased microglial densities and activation in certain regions, potentially reflecting abnormal circuit refinement (Rajkowska, 2000). The glia/neuron ratio concept, in this context, extends to the idea that glial oversight of synapses must scale with neural circuit complexity. In larger brains, not only are there more synapses that might require monitoring, but the consequences of synaptic dysregulation are greater for cognitive function, so robust microglial presence is beneficial.

Oligodendrocytes and NG2 glia also affect synaptic function indirectly. Proper myelination by oligodendrocytes ensures synchronous arrival of action potentials, which can influence timing-dependent synaptic plasticity. Myelin also reduces the energy cost and latency of signal propagation, thus shaping the integration of information across brain regions. Recent evidence indicates oligodendrocyte precursors (NG2 cells) receive synaptic input from neurons and might modulate neuronal firing patterns or serve as intermediaries in signaling networks, though these roles are still being explored (Verkhratsky et al., 2014). A higher oligodendrocyte count per neuron (as in human brains) could thus contribute to more finely tuned neural communication and timing.

Overall, the functional implication is that brain regions with higher glia/neuron ratios have a greater capacity for modulating and fine-tuning synaptic activity. They can maintain low noise (via neurotransmitter uptake), high fidelity (via ion buffering), and adaptive plasticity (via gliotransmission and synapse pruning). These features are crucial for complex learning and memory. Conversely, if glial support is insufficient (low glia/neuron ratio), synaptic function might be more rudimentary or less plastic, potentially limiting computational complexity. This concept aligns with comparative studies suggesting that primate brains (with more astrocytes relative to neurons) have more efficient synaptic information processing and plasticity than rodent brains (Elsayed & Magistretti, 2015). We next examine direct evidence that differences in glia are tied to differences in cognitive capability.

2.5. Glia, Cognition, and Evolution of Brain Complexity

One of the most striking findings of the past decade is that glial cells can enhance cognitive processing. A pivotal experiment by Han et al. (2013) demonstrated this directly: when human glial progenitor cells were transplanted into newborn mice (repopulating the mouse brain with human astrocytes), the chimeric mice exhibited improved learning and memory performance compared to normal mice. These mice outperformed controls in multiple tasks (maze navigation, fear conditioning, object-location memory) and showed heightened long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices (Han et al., 2013). What was different in their brains? The human astrocytes, which had matured and integrated, were morphologically and functionally distinct – they were much larger than native mouse astrocytes and communicated faster. In fact, human astrocytes in the mouse brain retained their species-typical size and complexity, coupling to the mouse neural circuitry yet propagating calcium signals three times faster than mouse astrocytes (Han et al., 2013). They also released higher levels of certain modulatory molecules (e.g., TNF-α) that enhanced synaptic strength by increasing neuronal glutamate receptors (Oberheim et al., 2009). These findings suggest that the evolutionary increase in glia/neuron ratio and in glial sophistication in humans contributes directly to cognitive advantages. Human astrocytes appear to endow neural networks with faster information integration and greater plasticity, thereby “upgrading” the brain’s computational power (Oberheim et al., 2009).

Even aside from transplantation studies, comparative neuroanatomy hints that glial evolution went hand-in-hand with neuronal evolution. Human astrocytes are not only larger, but come in subtypes not seen in rodents (such as interlaminar astrocytes in cortex) and have more diverse gene expression. They also respond to neurotransmitters in ways that can fine-tune neuronal firing patterns. Such differences likely required an increase in the number and complexity of glia relative to neurons. The glia/neuron ratio in human association cortex (which subserves higher cognitive functions) might be especially high to support prolonged firing, extensive synaptic networks, and learning processes. Indeed, in primates, cortical glia density increases with cortical expansion, correlating with cognitive capacity (Elsayed & Magistretti, 2015). Researchers have proposed that astrocytes participate in computations by regulating the gain and timing of neuronal responses, effectively acting as a form of parallel processing unit in the brain’s circuitry (albeit slower than neurons). While neurons handle fast point-to-point signaling, astrocytes handle modulatory volume signaling and metabolic budgeting – both of which are critical for complex cognition, from attention to memory consolidation.

It is also noteworthy that the evolution of brain size in mammals did not result in substantially higher neuronal densities – instead, brains got bigger by having more neurons of roughly similar size in primates (isometric scaling) or somewhat larger neurons in some lineages (Azevedo et al., 2009). In both cases, glial numbers rose commensurately. The uniform scaling law observed by Herculano-Houzel (2014) implies that any deviation (e.g., a hypothetical primate brain that tried to pack neurons more densely without adding glia) may have been non-viable or non-advantageous. Evolution seemingly “chose” to keep glia/neuron ratio within an optimal range, sacrificing neuron packing density if necessary, so that each neuron has adequate support. This speaks to how crucial glia are: you can’t just shrink neurons and cram more in to get a smarter brain, because those neurons would starve or seize without enough glia. Instead, primates increased neuron count while maintaining enough glia, resulting in larger brains. In humans, this manifests as a cortex that, despite housing fewer neurons than a rodent cortex of equal size would, can sustain far more complex activity patterns – likely because of richer glial support per neuron.

From an evolutionary perspective, certain glial innovations may have been as important as neuronal innovations. The emergence of fast communication pathways (myelinated fibers) was only possible with oligodendrocytes evolving; the capacity for fine synaptic modulation grew with elaboration of astrocytic networks. Some scientists have even speculated that genomic changes in human evolution that affect glia (such as gene expression differences in astrocytes) could underlie traits like enhanced learning or longer attentional span. While neurons are often the focus in discussions of human brain evolution, it may be more accurate to consider humans as having a uniquely optimized neuron–glia partnership.

In summary, ample evidence now supports that glia are integral to cognitive function. A higher glia/neuron ratio can endow a brain with superior abilities to process information, learn, and adapt, by virtue of more robust synaptic modulation and metabolic resilience. The human brain, with its roughly equal numbers of glia and neurons (von Bartheld et al., 2016) and especially high glial investment in the cortex (Azevedo et al., 2009), represents an extreme point on this spectrum – one where glial support has been maximized to allow our neurons to fire energetically and plastically through decades of life. The next section examines what happens when this delicate balance is disturbed: how changes in glial number or function relative to neurons can lead to brain disorders.

2.6. Glia/Neuron Ratio and Brain Disorders

Given the vital roles of glia in supporting neurons, it is not surprising that disturbances in glia/neuron ratio or glial function are implicated in many brain diseases. Pathology can upset the neuron-glia balance in two main ways: loss of neurons (which increases the ratio by leaving glia without their neuronal partners) or loss/dysfunction of glia (which lowers the support for each neuron). Both scenarios occur in different conditions, and both can have serious consequences for brain function.

In neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease (AD), neurons gradually die, especially in the cortex and hippocampus. Initially, glial cells (particularly astrocytes and microglia) become reactive and may even proliferate – an attempt to contain damage and clear debris. Postmortem cell counts in advanced AD brain tissue have found not only neuron loss but also an increase in activated glial cells in affected regions (Rajkowska, 2000). This reactive gliosis can lead to a locally elevated glia/neuron ratio, but the glia that remain are often dysfunctional (astrogliosis involves altered astrocyte states that may not support synapses effectively, and microglia can become inflammatory). One stereological study of AD patients reported significant astrocyte loss in some regions despite overall gliosis, indicating heterogeneous glial responses (Rajkowska, 2000). In sum, AD features a misbalance: too few neurons and sometimes also impaired glia, breaking the normal supportive ratio and contributing to synaptic failure and cognitive decline.

In psychiatric and mood disorders, a subtler glial pathology has been documented. Unlike neurodegeneration, classic psychiatric illnesses (depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder) do not involve massive neuron loss – instead, they have been linked to glial changes. Postmortem analyses of brains from patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and schizophrenia have consistently found reduced glial cell counts or density in key cortical areas (such as prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate) (Rajkowska, 2000). For example, one study found a glia/neuron ratio decrease in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in depression associated with glial atrophy. Verkhratsky et al. (2014) have termed depression and schizophrenia as “gliopathologies” to highlight that glial dysfunction (astrocyte atrophy, loss of synaptic support, oligodendrocyte and myelin abnormalities) may underlie the neuronal dysregulation in these conditions. Reduced astrocyte numbers could lead to impaired glutamate uptake and potassium buffering, contributing to the glutamate hyperactivity and impaired synaptic plasticity observed in depression (Coyle & Schwarcz, 2000). Oligodendrocyte deficits and demyelination have also been noted in some depression cases, possibly slowing down neural circuits involved in mood regulation. Intriguingly, antidepressant treatments and electroconvulsive therapy have been shown in animal models to increase astrocyte numbers or restore glial function, suggesting that part of their therapeutic effect might be through normalizing neuron-glia interactions (Coyle & Schwarcz, 2000).

In neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), glial cells are again central. ASD brains can show increased glial cell densities and activation (microglial activation and astrocytosis) in cortical regions (Rajkowska, 2000). Some theories posit that an excessive glia/neuron ratio early in development (due to overproduction of glia or under-pruning of neurons) could disrupt the formation of neural circuits. Microglia-mediated synaptic pruning is critical during development; if microglia are dysfunctional, an imbalance can persist in synaptic connectivity, which is one proposed mechanism in ASD. Recent transcriptomic studies also find that many risk genes for autism and schizophrenia are highly expressed in glial cells, implicating glial biology in the etiology of these disorders.

Even in the aging brain, changes in glia/neuron ratio are observed. Normal aging involves some neuron loss in certain areas and often an increase in activated microglia and hypertrophic astrocytes. The ratio of glia to neurons tends to increase with age, and while some glial changes are compensatory, others may impair neuronal function (for instance, aged astrocytes become less efficient at supporting synapses). An imbalance in the aged brain might contribute to age-related cognitive decline or increased susceptibility to neurodegenerative disease.

From a clinical perspective, the recognition that glial cells are key players in brain disorders has led to what some have called a “glial revolution” in neuropathology (Coyle & Schwarcz, 2000). As one commentary noted, for too long glia were “grossly neglected” in studies of psychiatric disease, but now they are considered potential targets for treatment (Coyle & Schwarcz, 2000). For example, therapies that bolster astrocyte function or number (such as certain neurotrophic factors, or drugs that enhance glutamate uptake) are being investigated for depression. In multiple sclerosis (an autoimmune attack on oligodendrocytes), strategies to protect or replenish oligodendrocytes are fundamental to preventing neuron loss. Even in Alzheimer’s, there is interest in modulating microglial activation to promote clearance of amyloid without causing neuroinflammation. In all these cases, the underlying principle is to restore a healthy balance between neurons and glia – either by preventing glial loss or mitigating glial overactivation.

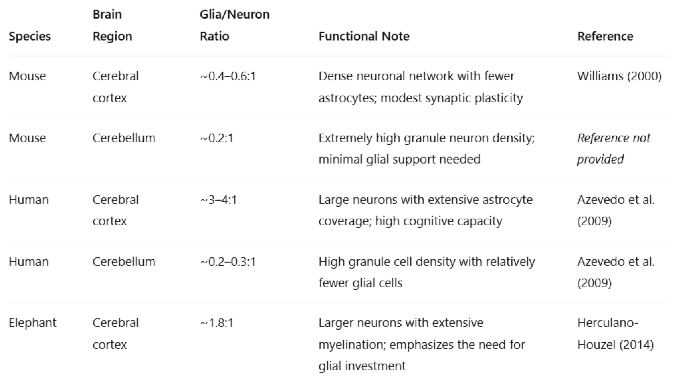

Table 1.

Functional Interpretation:Low glia/neuron ratio (e.g., cerebellum) → dense packing of small neurons with less metabolic overhead. High glia/neuron ratio (e.g., human cortex) → increased metabolic support, synaptic modulation, and plasticity, correlating with advanced cognitive functions.

Table 1.

Functional Interpretation:Low glia/neuron ratio (e.g., cerebellum) → dense packing of small neurons with less metabolic overhead. High glia/neuron ratio (e.g., human cortex) → increased metabolic support, synaptic modulation, and plasticity, correlating with advanced cognitive functions.

It is important to note that not all changes in glia/neuron ratio are detrimental. The brain can sometimes compensate for neuron loss by astrocytic proliferation (gliosis) to support remaining neurons. However, this compensation has limits, and reactive glia often cannot fully mimic the functionality of the neuron–glia units that were lost. Additionally, because of the interdependence of neurons and glia, a primary pathology in one will inevitably affect the other. For instance, if neurons degenerate (primary neuronal disease), glia will react and the ratio changes secondarily; if glia are primarily affected (as in some leukodystrophies or astrocytopathies), neuron function suffers downstream.

In summary, a growing body of evidence links abnormal glia/neuron ratios to disease states. Reductions in glial support (lower glia per neuron) are associated with psychiatric and mood disorders, potentially weakening synaptic regulation and metabolic support, whereas excess or aberrant glia (higher glia/neuron due to neuron loss or glial reactivity) characterize many neurodegenerative conditions, potentially contributing to inflammation and network dysfunction. These insights reinforce that the glia/neuron ratio is a sensitive indicator of brain health. Keeping the proper ratio – or restoring it after injury – could be a new frontier in treating brain disorders, aligning with the concept that neurons and glia must be treated as a unified system in any therapeutic strategy.

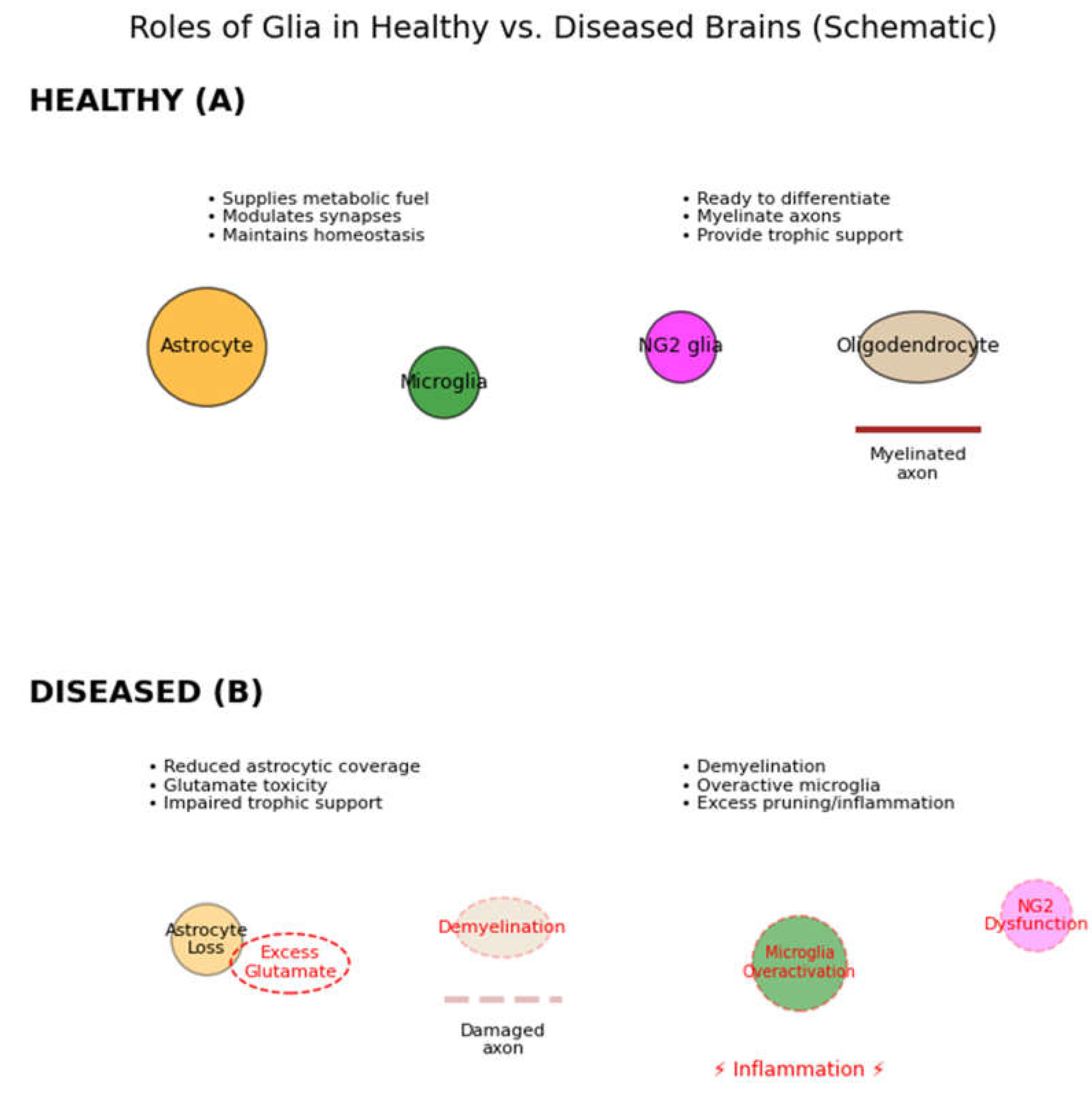

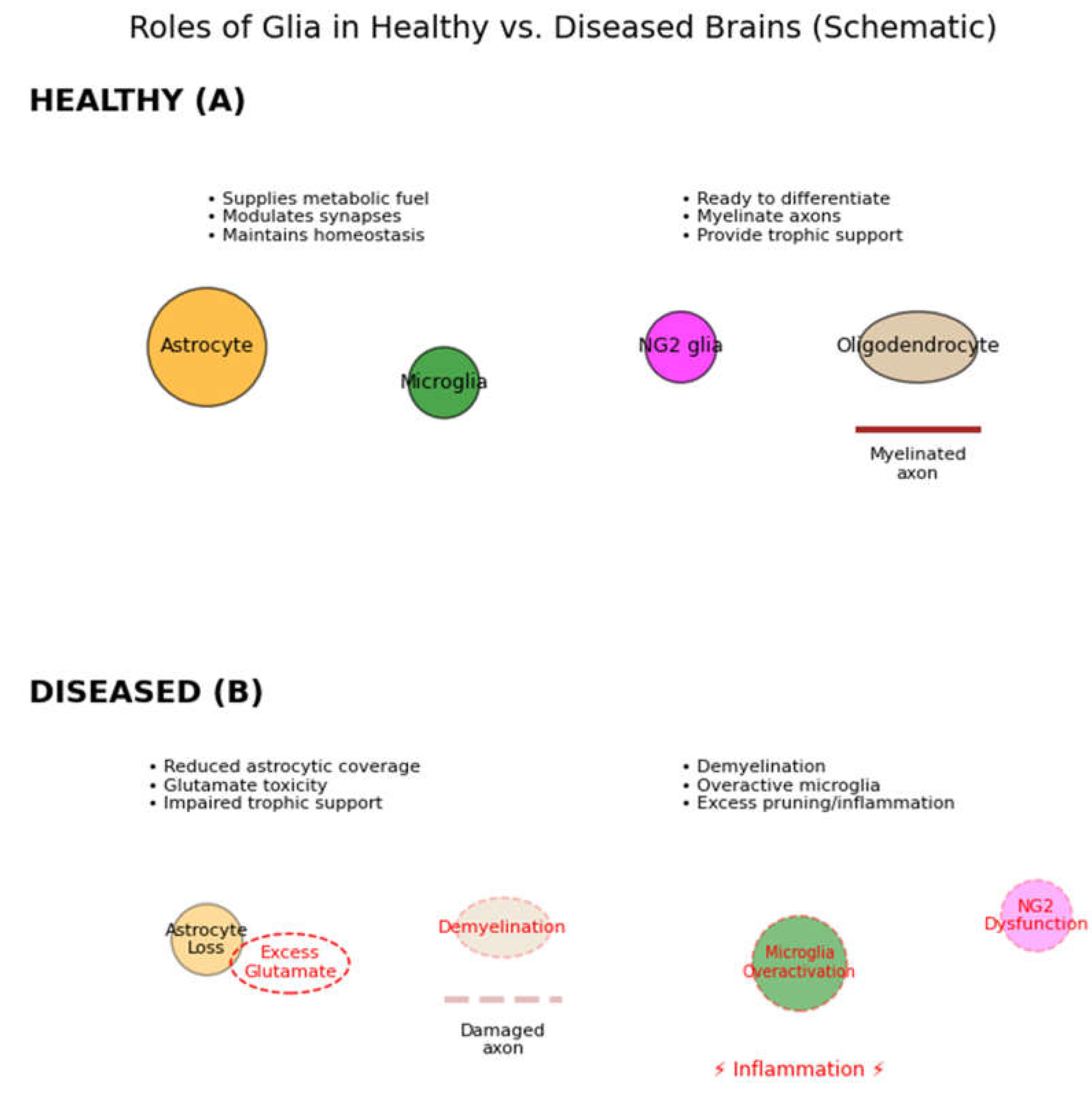

Figure 2.

Roles of glia in healthy versus diseased brains (schematic). In healthy conditions (A, top), multiple types of glial cells support neurons: Astrocytes (orange) supply metabolic fuels (e.g. lactate), growth factors, and neurotransmitter uptake (glutamate recycling); they also modulate synapses via gliotransmitters (purple vesicles) to facilitate synaptic plasticity. Microglia (green) survey the CNS, pruning unnecessary synapses and clearing debris (phagocytosing apoptotic cells), thus refining neural circuits. NG2 glia (magenta) serve as oligodendrocyte precursors, ready to proliferate and differentiate into new oligodendrocytes (tan) which myelinate axons (brown myelin wrapping) and metabolically support neurons. Together these glial functions (trophic support, homeostasis, insulation) are essential for normal neuronal communication. In pathological conditions (B, bottom), glial loss or dysfunction leads to multiple failures: loss of astrocytes causes reduced trophic support and impaired neurotransmitter clearance (glutamate overspill, leading to excitotoxicity); loss of or damage to oligodendrocytes results in demyelination (slowing conduction and straining neurons); microglial dysfunction can result in inadequate synaptic pruning or, conversely, excessive inflammation (red thunderbolt) that harms neurons. Such imbalances ultimately impair neuronal activity and can manifest as cognitive or behavioral deficits. (Elsayed & Magistretti, 2015).

Figure 2.

Roles of glia in healthy versus diseased brains (schematic). In healthy conditions (A, top), multiple types of glial cells support neurons: Astrocytes (orange) supply metabolic fuels (e.g. lactate), growth factors, and neurotransmitter uptake (glutamate recycling); they also modulate synapses via gliotransmitters (purple vesicles) to facilitate synaptic plasticity. Microglia (green) survey the CNS, pruning unnecessary synapses and clearing debris (phagocytosing apoptotic cells), thus refining neural circuits. NG2 glia (magenta) serve as oligodendrocyte precursors, ready to proliferate and differentiate into new oligodendrocytes (tan) which myelinate axons (brown myelin wrapping) and metabolically support neurons. Together these glial functions (trophic support, homeostasis, insulation) are essential for normal neuronal communication. In pathological conditions (B, bottom), glial loss or dysfunction leads to multiple failures: loss of astrocytes causes reduced trophic support and impaired neurotransmitter clearance (glutamate overspill, leading to excitotoxicity); loss of or damage to oligodendrocytes results in demyelination (slowing conduction and straining neurons); microglial dysfunction can result in inadequate synaptic pruning or, conversely, excessive inflammation (red thunderbolt) that harms neurons. Such imbalances ultimately impair neuronal activity and can manifest as cognitive or behavioral deficits. (Elsayed & Magistretti, 2015).

3. Conclusions

Glia and neurons stand as co-equals in the brain’s cellular society: neither can thrive without the other. The glia/neuron ratio encapsulates this partnership, offering a quantitative lens on how brains are built and how they function. As we have seen, this ratio varies uniformly with neuronal size and density across species – a finding that emphasizes an evolutionary throughline that brain computation is a team effort, requiring proportional investment in supportive glia for every neuron added. Functionally, a higher glia/neuron ratio endows brain tissue with greater metabolic resilience, finer control of synaptic transmission, and enhanced capacity for plasticity and information processing. Conversely, deviations in this ratio are at the heart of many neuropathologies, from the subtle glial deficits in depression to the reactive gliosis of neurodegeneration.

What does the glia/neuron ratio teach us about brain evolution and physiology? First, it teaches humility in our neuron-centric view of the brain: the “other” cells are equally important in enabling the feats of cognition and consciousness we often attribute solely to neurons. The human brain’s remarkable abilities likely stem not just from having many neurons, but from providing those neurons with unsurpassed glial support. Second, it highlights a design principle – scalability with stability – indicating that evolution increased brain size by scaling up supportive infrastructure in tandem with computational elements. Third, it suggests new metrics for brain health. Going beyond neuron counts, assessing glial populations and neuron-glia ratios in different regions could improve our understanding of disorders and even serve as biomarkers (for instance, via advanced imaging that can estimate glial content).

Looking ahead, several intriguing questions remain. Does increasing the glia/neuron ratio beyond natural levels (through cell therapy or genetic manipulation) further enhance cognitive function, or are there diminishing returns? Could we treat certain brain injuries by transplanting or stimulating glia to re-establish a healthy ratio and prevent secondary neuronal loss? Are there regional variations in optimal glia/neuron ratio even within the cortex that correlate with functional specialization? As methods to label and observe glia in vivo improve, we are likely to gain deeper insight into how dynamic fluctuations in the neuron-glia relationship underlie learning, sleep, mood, and more.

In conclusion, the glia/neuron ratio is a unifying concept linking brain structure, function, evolution, and pathology. As one commentary presciently noted, for too long glia were “grossly neglected” – they are now recognized as indispensable (Coyle & Schwarcz, 2000). Brain physiology is fundamentally the story of neurons and glia. By studying their ratio and relationships, we enrich our understanding of how brains—from mice to humans—operate at peak performance and how we might intervene when that partnership falters. The uniformity of glia/neuron ratio scaling across 90 million years of evolution (Herculano-Houzel, 2014) speaks to a simple truth: to build a bigger or better brain, nature did not just add neurons, it carefully added glia in lockstep, and any future therapies to rebuild or enhance brains must do the same.