Introduction

Part one of this analysis, highlights the critical role of elemental ratios, particularly nitrogen to carbon, in metabolic processes and epigenetic adaptations. When all biological pathways are stripped back to their core, elements like nitrogen, phosphorus, oxygen (O2), sulphur, and carbon are driving metabolic processes. O2 is required for acetylation and demethylation; hydrogen and carbon are required for methylation, and nitrogen, sulphur, and phosphorus are required for their respective epigenetic modifications (Sedley L 2023). Nutritional biochemistry has advanced significantly; quantum biology which analyses the dynamic interactions at the atomic level allows us to fine tune organic pathways presenting new opportunities for personalised disease prevention and health optimisation (Sedley L 2025).

Moreover, advances in technology, along with a modern understanding how our environment, diets and lifestyle impact epigenetics and evolution, emphasises the need for a thorough reevaluation of our current techniques, methods, and concepts. By tracing these ideas back to their origins and analysing early data, we can validate or challenge existing mechanisms, ultimately for enhancing public health outcomes.

Elemental Ratios

An imbalanced ratio of elements requires epigenetic adaptation of elementary pathways (Sedley L 2023). Still renowned for their harmful effects, gaseous molecules present in our environments like nitric oxide (NO), sulphur dioxide (SO2 ), hydrogen sulphide (H2S), carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4) and hydrogen cyanide (HCN), when are endogenously produced, possess significant and essential epigenetic properties of which we are only beginning to understand (Kuschman HP, Palczewski MB et al 2021) & (Sedley L 2023). This highlights the biological significane of a concept, that was once thought to be minor.

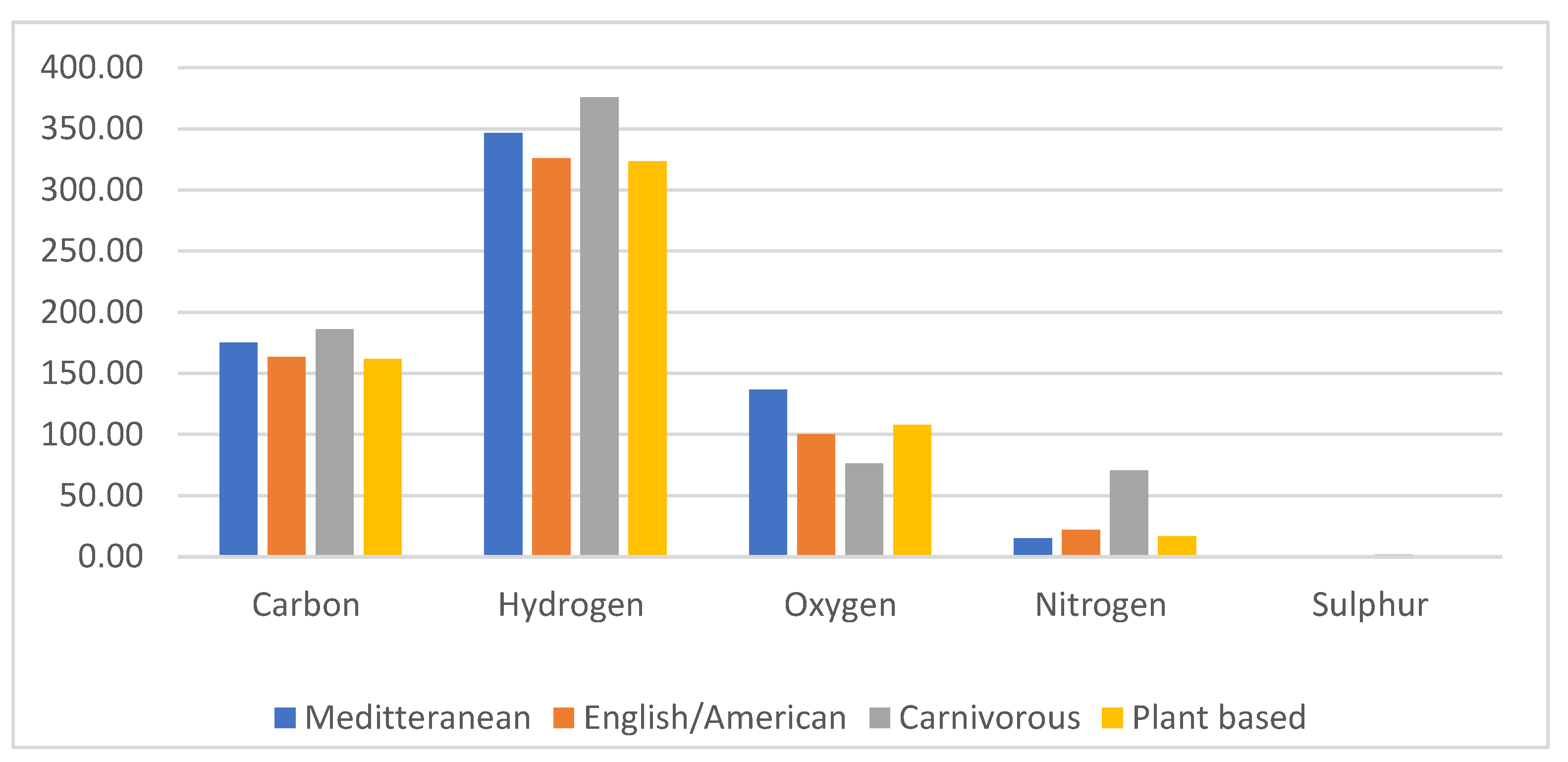

The elemental composition of various diets were analysed and compared for their influence on epigenetic mechanisms and for comparison of early and modern literature. Evidence of the Indigenous Australian's diet was documented in 1803, animal produce was highly preferred; consuming very little seasonal roots, seeds and fruit (Morgan J 1979) Their body composition was very lean (Morgan J 1979) & (Hicks CS 1963), and like the Inuit population, they consumed a high calorie diet, comprised of a large portion of meat to sustain significant daily physical activity (Kommissionen for Ledelsen af de Geologiske og Geografiske Undersøgelser i Grønland, Meddelelser om Grønland 1915).

The analysis of carnivorous diets provides insight into the benefits of low carbohydrate dietary preferences on metabolism, this is important to advance with personalised medicine, considering populations like Indigenous Australians, who have experienced a rapid decline in health since British colonisation, largely due to environmental changes and dietary disruptions (Valeggia & Snodgrass, 2015).

The carnivorous diet was compared to the modern Mediterranean diet, (Mantzioris E, Villani A 2019) & (Dietitian/Nutritionists from the Nutrition Education Materials Online “NEMO” team - Queensland Government (2021) & (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2014). a plant-based diet (Hess JM 2022) and an early traditional English/American diet (1749- 1830) & (Simmons A 1796) & (Irwin D (1830) & (Glasse H 1747).

Figure 1: Elemental Ratios of 3000 Calorie Diets.

Protein

Tracing back to 1839, Gerritt Mulder discovered that a radical substance derived from animal organs contained 16-17% nitrogen; sulphur and phosphorus. The radical substance was named protein (Carpenter KJ 2003) & (Bregory W, London M (Ed) 1842). In 1842, Justus Liebig, a German organic chemist demonstrated that protein derived from plants and animals were chemically comparable, containing the same carbon to nitrogen ratio of 4:1. He was fascinated by the fact that plant proteins although identical to animal proteins, served different purposes. He suggested plant proteins comprised the animal’s blood, since animals could not constitute its organs as it can’t produce an elemental body like nitrogen, from something it did not contain or consume (Bregory W, London M (Ed) 1842).

He later described medicinal components to be nitrogenous or non-nitrogenous, with the former being essential for the composition of graminivorous blood. He concluded radical proteins were essential to health, and animal extracts like ox bile could be used as medicine despite describing it as a waste product and toxic. Liebig went on to develop the animal extract OXO which was marketed to stimulate digestion (Bregory W, London M (Ed) 1842).

Adaptation to Plant-Based Diets

Despite the known adaptation to increased starch consumption in some cultures, adjusting to a plant-based diets has not been seamless. Poor adaptation became obvious in the early 19th century. It was not until much later that changes in dietary practices could be linked to nutritional deficiencies (Leitzmann C 2014).

In 1882, German Physician M. Koeniger was travelling the Philippines and recognised a disease that appeared among the natives as beriberi, which he described to be identical to kakke a disease which was prevalent in Japan at the time (De Bevoise K 1995). Beriberi became a common disease in southeast Asia delivering high mortality and disability until the 1930's. It was suggested that plant-based diets or diets containing polished rice, which removed the thiamine during the hulling process, was responsible for the disease (World Health Organisation 1999).

The true origin of beriberi is undocumented, yet the literature suggests it may have much deeper roots than thiamine deficiency. For a long time, vegetable colic, lead wine Poitou, feather white wine disease, Barbier’s disease and beriberi were mistaken for each other (Gaüzère BA, Aubry P 2014) & (McDonald ABL 1939) & (Bregory W, London M (Ed) 1842). Polioencephalomalacia is a neurological disease of ruminants which can explain the indisputable connection between the clinical manifestations and the cause of confusion. Polioencephalomalacia can be caused by thiamine deficiency, lead, sulphur, thiaminase or sodium toxicity (Niles GA, Morgan SE et al 2002), which suggests an underlying epigenetic commonality.

The catalogue of neurological symptoms caused significant confusion throughout the World for centuries (Gaüzère BA, Aubry P 2014). The earliest reports of an unidentified disease causing gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms was in Italy 600AD. In the 1572, a colic stormed the French wine region of Poitou, causing major gastrointestinal, neurological disease and death and remained in the region for over 60 years. Likely due to epigenetic adaptation and pre-evolution (Sedley 2023), overtime, the disease got less intractable and less severe. In 1696, German physician named the disease lead wine Poitou after discovering lead used in the preservation of wine. The colic is considered one of the longest lasting and widespread epidemics known (Eisinger J 1982).

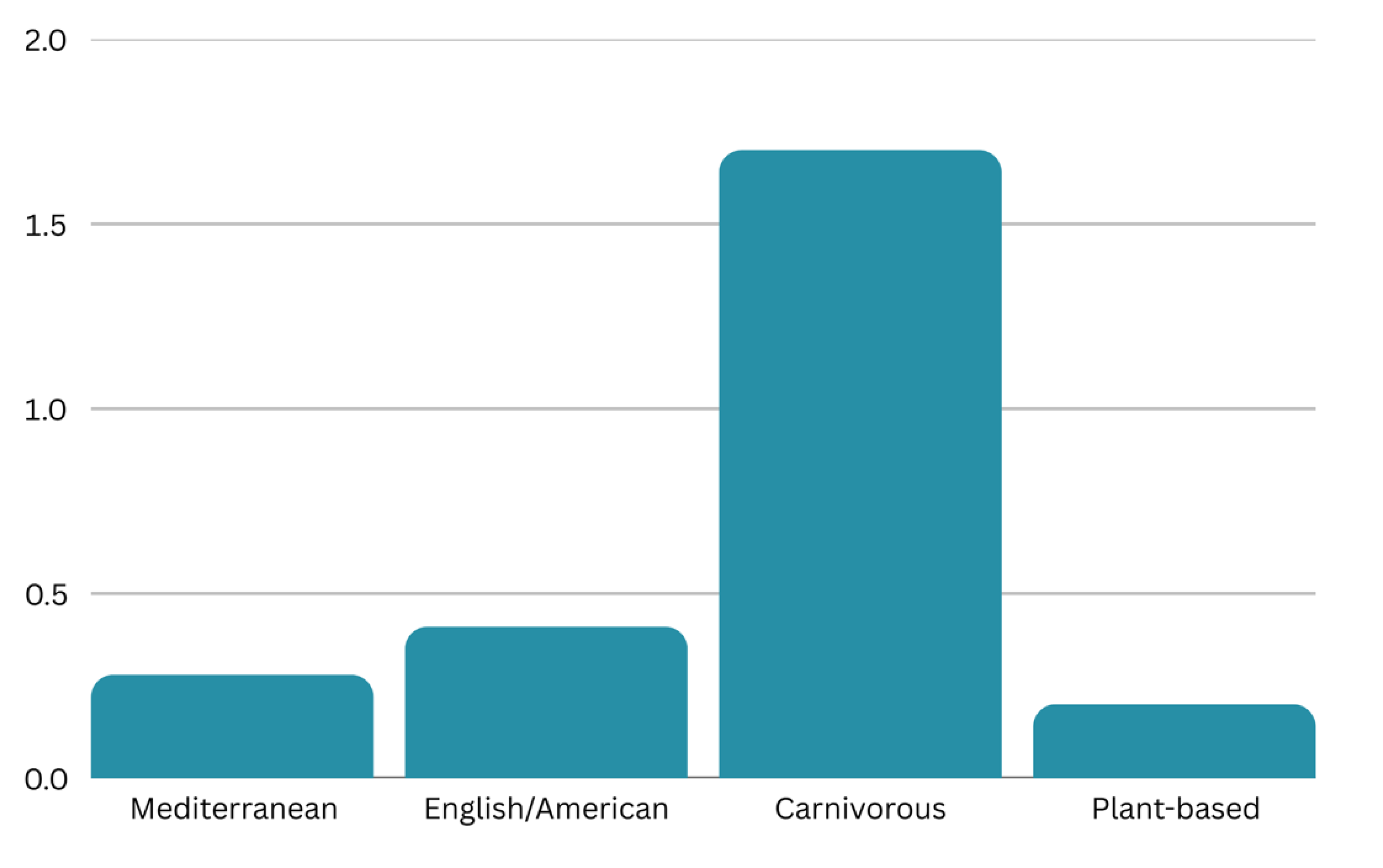

Sulphur

Lead may not have been the only influence in the Poitou epidemic. Yeast wine fermentation can produce highly potent sulphurous compounds. Different strains of yeast and different grape varieties produce various levels of sulphurous compounds, which can be toxic (Cordente AG, Curtin CD et al 2012) & (Sáenz-Navajas MP, Sánchez C et al 2023). Excess sulphates in the diet are shown to deactivate thiamine through the formation of thiamine disulfide (Williams RR, Waterman RE et al 1935) & (Kritikos G, Parr JM et al 2017) & (Lenz AG, Holzer H 1985).An excess of sulphur in the diet can lead to a beriberi like neurological degeneration and death which is also observed in cats, dogs and ruminants (Kritikos G, Parr JM et al 2017) & (Niles GA, Morgan SE et al 2002). Sulphites have been used as a preservative in the food, drug and cosmetic industries for a long time (Malik MM, Hegarty MA et al 2007). Throughout the 19th century, the consumption of sulphate preserved canned meats may have played a role in the high incidence of ship beriberi (Unspecified 1866) & (D’Amore T, di Taranto A et al 2020). Sulphites are reported to induce a range of adverse clinical effects in sensitive individuals, including life- threatening anaphylaxis, asthma (Vally H, Misso N et al 2012), and paralysis (Robert K, Bush M 1986). Exogenously supplied sulphur compounds like sodium bisulphite are genotoxic (Meng Z, Nie A 2005). Sodium bisulphite, which is sometimes used to preserve food, is also used to modify nucleotides through dehalogenation or deamination in genomic sequencing (Hayatsu H, Wataya Y et al 1970). Sodium metabisulfite reacts with acids in water and releases toxic sulphur dioxide (SO2) gas, which in excess is neurotoxic due to its influence on potassium currents (Meng Z, Nie A 2005). Sulphation is one of the least understood epigenetic post-translational modifications. There are often discrepancies due to the mass of the sulphate group being remarkably like the phosphate group, and the ability to modify the same histone residues (Taylor SW, Sun C et al 2008) & (Yu W, Zhou R et al 2023) & (Singh RK, Kabbaj MHM et al 2009).

Due to significant variation of sulphur content in food stuffs, only the protein portion of the four diets were analysed for sulphur (Food Stand Editors at Food Standards Australia and New Zealand 2020). Given the carnivorous diet contains 4-5 times more sulphur, suggests that the early concomitant consumption of animal protein and wine, would push sulphur beyond metabolic capacity. This is evidenced by cats and dogs, who consume a high protein diet, but are very sensitive to sulphur in grapes (Kritikos G, Parr JM et al 2017) & (Niles GA, Morgan SE et al 2002). Therefore, given that dietary sulphur is very low in comparison to

As discussed, we have only just begun learning more about the role gas transmitters play in critical metabolic processes (Sedley 2023). If we consider the toxicity of exogenous gaseous molecules, we can understand how a dietary imbalance can lead to ill health. Heme Oxygenase (HO) is an oxygen sensor and mediator of endogenous gas transmitters such as carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), and sulfur dioxide (SO₂), Nitric oxide (NO). Their synthesis is epigenetically programmed and tightly regulated (Sedley L 2023). Under hypoxic conditions, haem oxygenase (HO) activity is reduced, leading to decreased production of CO. This reduction in CO, lifts its inhibitory effect on cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS), thereby activating the trans-sulfuration pathway, a key extension of the one-carbon metabolism (1-CM) cycle, which results in increased production of H₂S and SO₂ (Sedley, 2023). Prolonged anaerobic states within muscle tissue, can lead to the accumulation of H₂S, a bioactive gas with significant physiological impact. Under normoxic conditions, H₂S is enzymatically oxidised into SO₂ (Veeranki & Tyagi, 2015), a gaseous molecule with precise roles in cardiovascular regulation, including vasodilation and blood pressure modulation (Huang, Tang et al., 2016).

Although toxic when inhaled, endogenous H2S plays an essential role neurogenesis, and suggests that the sulphur component of animal protein diets, played an important role in human brain evolution (Sharif AH et al 2023).

At the elemental level, a change from a carnivorous diet to a Mediterranean diet, results in a reduction in carbon, hydrogen and sulphur, and increase in oxygen. For example, the concomitant reduction in hydrogen, would allow for more SO2, than H2S. At the level of dietary preference, early, there was a sudden increase in wine sulphur, thiaminase in plant foods, preservation of canned and dried foods and eventually a reduction in thiamine from the rice hulling process and various unknown changes due to the use of pesticides. Therefore, even today, without a thorough analysis elemental ratio, rapidly switching diets, may be dangerous, but sulphur sensitivity may provide insight into dietary excess. It is vital that finding elemental equilibrium should be prioritised as we progress towards personalised medicine, and with the assistance of modern technological advances, this is very achievable. This concept is discussed in greater depth in part three.

Figure 2: Protein Sulphur of 3000 Calorie Diets.

Nitrogen

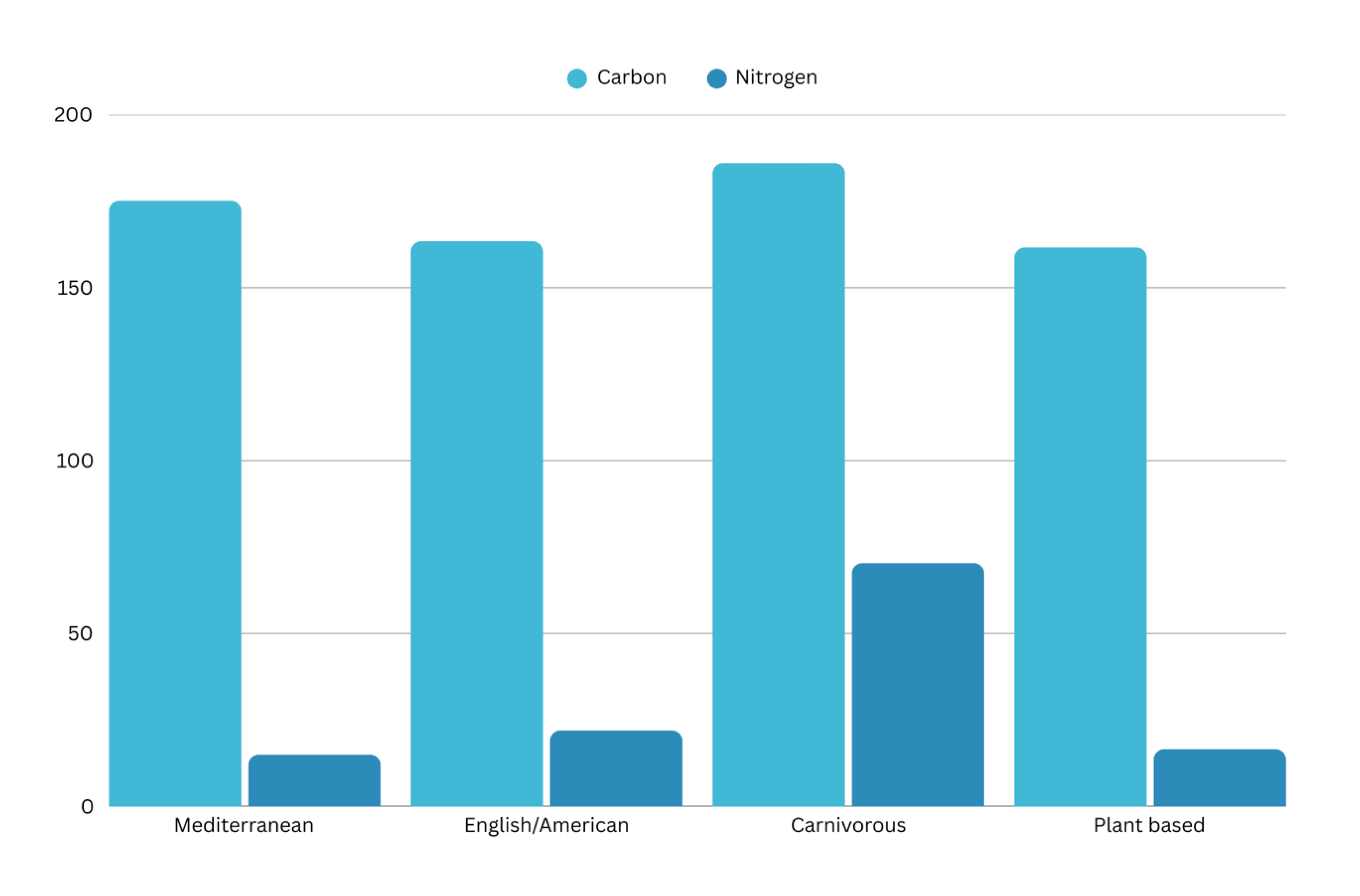

In studies of ship beriberi in the Japanese Navy, medical officer Kanehiro Takaki noticed that beriberi was mostly associated with the poor and was prevalent amongst those receiving dietary rations. Takaki analysed the elemental dietary ratios which determined that healthy subjects consumed a nitrogen:carbon ratio of 1:15.5 and a ratio of over 1:28 was always associated with beriberi (Sugiyama Y, Seita A 2013). In 1884, Takaki proposed a meal plan richer in nitrogen and eliminated the disease amongst the Japanese navy (Sugiyama Y, Seita A 2013) (Takaki B 1906). Together, this reveals dysregulated core elemental were the driving mechanisms of these neurological conditions.

But despite beriberi being successfully treated with nitrogen, in 1911, Suzuki identified and isolated thiamine from rice bran extracts which was said to be essential for preventing beriberi (Suzuki U, Shimamura TT 1911). However, Funk (1913) demonstrated that a number of other nucleotides could also prevent the symptoms of beriberi, once again, confusing the situation.

Given the confusion between the neurological presentation of beriberi, it should be notedthat free thiamine, binds lead in the gastrointestinal tract, enhancing its absorption, therefore, thiamine in fortified food may increase the risk of lead poisoning which may be masked as thiamine deficiency leading to a vicious cycle (Reddy SY, Pullakhandam R et al 2010).

Animal Extracts, Meat and Health

Barbier’s disease may have also indicated an imbalance in dietary elements. In etymology, the term barbarian or barbari was adopted from the Greek term barbaros meaning foreign or pagan (The Editors of the Online Etymology Dictionary 2023). The racial term was adopted to all people not under Greek- Roman domination (The Editors of Encyclopaedia 2023). The barbaric references adopted a deeply negative meaning in 1125, and was used to describe uncivilised country savages who ate primarily meat and little bread (Grant A, Stringer K 1995). More specifically, the term Barbier is derived from the Latin word barba, meaning beard (Editors of the Online Etymology Dictionary 2023). Interestingly, the hair trimming profession of a barber, was introduced to Rome, 454 years after the establishment of the city (Nicolson FW 1891). For over six centuries, barbers practiced as surgeons, this was following a papal decree in 1163 by Pope Alexander the III, which forbade the clergy to act as surgeons (Unspecified 1906). The Pope’s personal barber became the office’s phlebotomist which helped to establish the profession, which included bloodletting for disease treatment (Unspecified 1906). Bloodletting was adopted as a panacea to cleanse the blood of impurities (Bell TM 2016). Yet, despite the barbarian's negative reputation, the blood of fallen barbarian gladiators was considered medicinal, and documented to cure neurological conditions, like epilepsy (Moog FP, Karenberg A 2003). Blood was the subject of longevity experimentation for centuries. In 1492, surgeons fed Pope Innocent VIII the blood of 3 young boys in an experiment to revive him from a coma (Scott CT, DeFrancesco L 2015) & (Tucker H 2011).

Moving into the 20th century, it became widely known that animal derived constituents were essential to health and extracts could be used as medicines in those lacking dietary elements (Unspecified 1894) & (Osborne T, Mendel L 1911) & (Webster LT, Pritchett IW 1924) & (Hammond WA 1884).

The macronutrient analysis of equivalent caloric diets shows the carnivorous diet contains up to 15% more carbon and up to 70% more nitrogen than the other diets, yet all standard diets are well under the limitation of neurological disease. However, what is concerning is these diets do not consider, alcohol, medication, environmental influence and carbonated beverages which all have the potential to tip the ratio in excess of carbon, pushing beyond the limits described by Takaki B (1906)

Figure 3: Carbon to Nitrogen Ratio of 3000 Calorie Diets.

Table 1: Nitrogen to carbon ratio extracted from supplementary data.

Table 1.

Nitrogen to Carbon Ratio.

Table 1.

Nitrogen to Carbon Ratio.

| Diet |

Nitrogen to Carbon Ratio |

| Mediterranean |

1/ 11 |

| Plant-Based |

1/ 9.78 |

| Carnivorous |

1/ 2.64 |

| Traditional English/Australian/American (1747-1830) |

1/ 7.43 |

Nitrogen essentiality is defined by nitrogen balance. Negative nitrogen balance, where excretion of nitrogen surpasses dietary nitrogen intake, has been linked to detrimental health effects such as ageing, atrophy, as well as the development of neurological and psychological disorders (Sedley L 2023).

In the event of sudden dietary limitation, like incarceration, or prolonged dietary rations, epigenetic adaptation of all organ systems is required to prevent negative nitrogen balance and prevent hyper catabolism and atrophy of tissues like the brain (Kim TJ, Park SH et al 2020). So despite thiamine supplementation and its known ability to modulate carbohydrate pathways, and prevent the negative effects of increased thiaminase in plant foods, it is not sufficient to in replacing lost nitrogen.

Animal meat adopted a negative reputation due its association with nitrates and nitrosamines (Johnson M 2012) and was therefore considered a pharmakon (Leroy F 2018).

Laboratory Accuracy and Carcinogenicity

Cell culture and animal studies reporting the carcinogenic effects of red meat and nitrosamines are far from equivalent to endogenous human conditions. Many variables are not considered, for example, in cell cultures, the use of serum derived from animals, usually bovine, is essential for the growth and maintenance of a cell, due to the presence of specific transcription factor proteins and hormones (Johnson M 2012). Some excipients added to cell culture media, are used to immortalise cell lines. (Sedley L 2020) & (Ha G, Roth A 2014). In one particular study on the carcinogenicity of animal meat, reported by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (2018), cells were cultivated in abnormal light conditions impairing deoxynucleic acid (DNA) repair (Sedley L 2025), and in a synthetic media promoting immortality. Moreover, cells/tissues were prepared by washing in reagents, enabling a loss of natural epigenetic marks. Animal models like the wild type C57Bl/6J-APC Min murine strain, which are used to quantify adenoma formation following red meat consumption, are bred by crossing a murine strain that carries up to 60,000 pathogenic mutations (C57BL6J), with one that carries the murine T cell leukaemia virus (AKr/J), and is highly prone to developing tumours (International Agency for Research on Cancer 2018). In another significant study, the control group was fed extra calcium which is known to influence APC Regulator Of WNT Signaling Pathway (APC) gene activity reducing the incidence of adenoma (Liu S, Barry EL et al 2017). These studies on carcinogenicity often overlook key epigenetic mechanisms and the oversights may contribute to skewed results, making the risks appear more severe than necessary.

Nitrosamines

Nitrosamines are naturally occurring and synthesised endogenously by eukaryotes and prokaryotes (Fahrer J, Christmann M 2023). Some nitrosamine products are essential for epigenetic mechanisms, like the formation of 7-methylguanine which is essential for eukaryotic tRNA protein synthesis (Fahrer J, Christmann M 2023). In doses exceeding metabolic capacity, nitrosamines are genotoxic transferring methyl groups to DNA, forming carcinogenic adducts (Fahrer J, Christmann M 2023).

Nitrates alone, demonstrate a reduced risk of cancer, whereas the addition of nitrosamine N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) increases the risk (Song P, Wu L et al 2015). NDMA is a common nitrosamine produced endogenously in humans, at rate of approximately 1mg per day (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease 2023). NDMA is a contaminant of many industrially produced compounds including cosmetics, tobacco, and pesticides (up to 2.32 ug/g) and in a selection of foods like saurkraut (6.6 ug/kg) fried fish (1.69 ug/g) wine, beer (0.25-2.2 ug/L) and bacon (03.-20.2 ug/g) & (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease 2023). This demonstrates that consuming one rasher of bacon (30g), with maximum nitrosamines, is consuming only half of the daily endogenous production. With that said, like sulphur, it is also possible for nitrosamines to tip nitrogen levels over the threshold, particularly for a person who consumes a carnivorous diet. In contrast, it may be beneficial for a person who consumes minimal protein. Since foods may only mildly influence excessive nitrosamine levels, we need to look at what factors influence metabolic capacity.

Nitrosamine Synthesis

Most nitrosamines are formed by reactions with nitrates and methylated amines in an acidic medium (Gosar A, Shaikh T 2020). NDMA can be produced during manufacturing with formaldehyde or dimethalamine/diethalamine (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease 2023) & (Keeper LK,& Roller PP 1973). Formaldehyde is a dose dependant carcinogen and like nitrates, and its aqueous counterpart formalin is naturally present in many fruits, vegetables, and animal products (Jung HJ, Kim SH et al 2021).

The heating of dietary constituents like sugar, contributes significantly to local atmospheric formaldehyde (Jung HJ, Kim SH et al 2021), which may contribute to gastrointestinal nitrosamine formation. Recently, it has been discovered that many common pharmaceuticals contain NDMA impurities of up to 20 ug/g (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease 2023) & (Gosar A, Shaikh T 2020) & (Nasr NEH, Metwaly M, G et al 2021). Moreover, contaminated water also contributes to impurities throughout drug manufacture. The use of potable water is standard for the manufacture of active pharmaceutical ingredients (Committee for Propriety Medicinal Products Committee for Veterinary Medicinal Products 2002). The chlorination process contributes to NMDA concentrations of (0.004 - 0.008 ug/l) in drinking water (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease 2023). Henry’s law of gas demonstrates that even distilled water would gradually increase trace amounts of dissolved gases including NO, increasing the nitrous acid concentration of the water (Davishay DM, Kevin M et al 2023). Despite many textbooks suggesting nitrous acid does not react with amines, it does in dealkylating reactions forming N-nitrosamine (Ashworth IW, Dirat O et al 2020). Therefore, regardless of the application, the potential for N-nitrosation, S-nitrosylation and the formation nitrosamine products during laboratory exercises are possible without strict environmentally controlled conditions and may contribute to inaccuracies in molecular quantification of nitrosamines, carcinogenicity, and the analysis of any nitrogen containing biochemical pathways or epigenetic modifications. Moreover, B vitamins are a class of nitrogen containing methylated amines that can influence nitrosamine formation in the gastrointestinal tract, and therefore excessive supplementation could push levels beyond metabolic capacity.

Nitrosamine Degradation

In drinking water and the gastrointestinal tract, NDMA is naturally degraded by photolysis and microbial degradation, respectively (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease 2023). The gastrointestinal microbiome also contributes to the pool of nitrosamines (Suzuki TM 1984) & (Mills AL, Alexander M 1976), and reduces the nitrosamine load through reduction of nitrate and nitrosamine (Carpenter KJ 2003) & (Rowland IR, Grasso P 1975). Beyond the GIT, NDMA is metabolised by cytochrome P450 CYP2E1, forming hydroxymethylnitrosamine which is further degraded back to formaldehyde and a methyldiazonium ion (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease 2023). The residual formaldehyde contributes to the pool of single carbon units for methylation reactions (Sedley L 2023).

Conclusions

This paper argues that past misconceptions around nutritional deficiencies may stem from elementary imbalances and a lack of personalisation in dietary science. Historical dietary patterns, especially those of Indigenous populations, must be considered, considering these insights. Evidence suggests that nitrogen-rich, carnivorous diets may offer benefits to certain groups, such as Indigenous Australians, who have experienced disproportionate metabolic health challenges since colonisation. However, modern dietary practices and the increase in sulphurous compounds, continue to make personalised nutritional medicine difficult. However, the validity of longstanding laboratory studies, such as those linking red meat to carcinogenic outcomes, warrants reconsideration, considering current epigenetic knowledge. The use of modern computer technologies will utilised to clearly define elemental ratios to optimise personalised healthcare.

This study calls for a re-evaluation of current dietary guidelines, to better align with personalised, evolutionary, and elementally-informed approaches to health and nutrition.

References

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease (2023) Toxicological Profile for N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA).

- Ashworth IW, Dirat O et al Potential for the formation of n-nitrosamines during the manufacture of active pharmaceutical ingredients: an assessment of the risk posed by trace nitrite in water. Organic Process Research & Development 2020, 24, 1629–1646. [CrossRef]

- Bell, T. M. (2016). A Brief History of Bloodletting. Journal of Lancaster General Hospital, 11(4). Originally published in the Winter 2016 issue.

- Bregory W, London M (Ed) & Animal Chemistry or Organic Chemistry in its applications to Physiology and Pathology. Med Chir Rev LXXIV 1842, 34.

- Carpenter KJ (2003) History of Nutrition - A Short History of Nutritional Science: Part 1(1785-1885).

- Committee for Propriety Medicinal Products Committee for Veterinary Medicinal Products (2002) Note for guidance on quality of water for pharmaceutical use. European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, EMEA/CVMP/115/01, Effective 2023 https://www,tga.gov,au/resources/resource/international-scientific-guidelines/international-scientific- guideline-note-guidance-quality-water-pharmaceutical-use.

- Cordente AG, Curtin CD et al Flavour-active wine yeasts. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2012, 96, 601–618. [CrossRef]

- D’Amore T, di Taranto A et al Sulfites in meat: occurrence activity toxicity regulation and detection, A comprehensive review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2020, 19, 2701–2720. [CrossRef]

- Davishay DM, Kevin M et al (2023) Henry’s Law, StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- De Bevoise K (1995) Beriberi: Fallout from Cash Cropping. Agents of Apocalypse Epidemic disease in the Colonial Philippines, 118–141 Princeton University Press https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400821426.118. [CrossRef]

- Dietitian/Nutritionists from the Nutrition Education Materials Online “NEMO” team (Queensland Government) & (2021) Mediterranean-style diet. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/nutrition, Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- Editors at Food Standards Australia and New Zealand (2020) Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) Australian Food Composition Database, https://www,foodstandards,gov,au/science/monitoringnutrients/afcd/Pages/foodsbynutrientsearch, Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- Editors at Nutrition Australia (2013) Nutrition Australia. Australian Dietary Guidelines.

- Editors of the Online Etymology Dictionary (2023) Online Etymology Dictionary, Barbarian, Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- Editors of the Online Etymology Dictionary (2023) Online Etymology Dictionary, Barbier, Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- Eisinger J Lead wine and eberhard gockel and the colica pictonum. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 1982, 26.

- Fahrer J, Christmann M DNA Alkylation damage by nitrosamines and relevant DNA repair pathways. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Funk C. Studies on beri-beri: VII. Chemistry of the vitamine-fraction from yeast and rice-polishings. The Journal of Physiology, Jun 2013, 46, 173–179. [CrossRef]

- Gaüzère BA, Aubry P () La maladie appelée « Le Barbiers » au XIXe siècle. Médecine et Santé Tropicales 2014, 241–246. [CrossRef]

- Glasse H (1747) The art of cookery made plain and easy.

- Gosar A, Shaikh T Nitrosamine impurities and drug substance. Journal of Advances in Pharmacy Practices 2020, 2.

- Grant A, Stringer K (1995) Late medieval foundations. Uniting the Kingdom? The Making of British History. Routledge, London.

- Ha G, Roth A TITAN: inference of copy number architectures in clonal cell populations from tumor whole-genome sequence data. Genetic Resources 2014, 24, 1881–1893.

- Hammond WA (1884) Original communications on certain animal extracts- their mode of preparations and physiological and therapeutical effects. The Atlanta Medical and Surgical Journal 1884, 5–14.

- Hayatsu H, Wataya Y et al Addition of sodium bisulfite to uracil and to cytosine. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1970, 92, 724–726. [CrossRef]

- Hess JM Modeling dairy-free vegetarian and vegan USDA food patterns for non-pregnant nonlactating adults. The Journal of Nutrition 2022, 152, 2097–2108. [CrossRef]

- Hicks CS Climatic adaptation and drug habituation of the central Australian Aborigine. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 1963, 42, 39–57.

- Huang Y, Tang C et al Endogenous sulfur dioxide: A new member of gasotransmitter family in the cardiovascular system. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2016, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Barry EL et al Effects of supplemental calcium and vitamin D on the APC/β-catenin pathway in the normal colorectal mucosa of colorectal adenoma patients. Molecular Carcinogenesis 2017, 56, 412–424. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer Red Meat and Processed Meat, IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, 2018, 114.

- Irwin D (1830) The housewife’s guide or an economical and domestic art of cookery. William Mason, London.

- Johnson M (2012) Fetal Bovine Serum. Materials and Methods 2, Labome, World of Laboratories. https://www.thermofisher.com/au/en/home/references/gibco-cell-culture-basics/cell-culture-environment/culture-media/fbs-basics.html.

- Jung HJ, Kim SH et al Changes in acetaldehyde and formaldehyde contents in foods depending on the typical home cooking methods. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 414. [CrossRef]

- Keeper LK, Roller PP. N-Nitrosation by nitrite ion in neutral and basic medium. Science 1973, 181, 1245–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, TJ, Park, SH et al. Optimizing nitrogen balance is associated with better outcomes in neurocritically Ill patients. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommissionen for Ledelsen af de Geologiske og Geografiske Undersøgelser i Grønland, Meddelelser om Grønland (1915) København C, A, Reitzels Forlag 49.

- Kritikos G, Parr JM et al The role of thiamine and effects of deficiency in dogs and cats. Veterinary Science 2017, 4. [CrossRef]

- Leitzmann C Vegetarian nutrition: past present future. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2014, 100, 496S–502S. [CrossRef]

- Lenz AG, Holzer H Cleavage of thiamine pyrophosphate by sulfite in saccharomyces cerevisiae. Zeitschrift Fr Lebensmittel-Untersuchung Und -Forschung 1985, 181, 417–421. [CrossRef]

- Leroy F Meat as a pharmakon: an exploration of the biosocial complexities of meat consumption. Advances in Food and Nutrition Research 2018, 87, 409–446.

- Malik MM, Hegarty MA et al Sodium metabisulfite; a marker for cosmetic allergy? Contact Dermatitis 2007, 56, 241–242. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantzioris E, Villani A Translation of a Mediterranean-style diet into the Australian Dietary Guidelines: a nutritional ecological and environmental perspective. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2507. [CrossRef]

- McDonald ABL The aphorisms of corvisart. Ann Med Hist 1939, 1, 374–387.

- Meng Z, Nie A Effects of sodium metabisulfite on potassium currents in acutely isolated CA1 pyramidal neurons of rat hippocampus. Food Chemical Toxicology 2005, 43, 225–232. [CrossRef]

- Mills AL, Alexander M N-Nitrosamine formation by cultures of several microorganisms. Appl Environmental Microbiology 1976, 31, 892–895. [CrossRef]

- Moog FP, Karenberg A Between horror and hope: gladiator’s blood as a cure for epileptics in ancient medicine. Journal of the History of Neurosciences 2003, 12, 137–143. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan J (1979) The life and adventures of William Buckley. ANU Press.

- Nasr NEH, Metwaly M, G et al Investigating the root cause of N-nitrosodimethylamine formation in metformin pharmaceutical products. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety 2021, 20, 855–862. [CrossRef]

- Nicolson FW Greek and Roman barbers. Classical Physiology 1891, 2.

- Niles GA, Morgan SE et al The relationship between sulfur thiamine and polioencephalomalacia-a review. Bovine Practitioner, (Stillwater) 2002, 36, 93–99.

- Osborne T, Mendel L The role of different proteins in nutrition and growth Nutritional. Science, XXXXIV 1911, 882.

- Reddy SY, Pullakhandam R et al Thiamine reduces tissue lead levels in rats: Mechanism of interaction. BioMetals 2010, 23, 247–253. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert K, Bush M A critical evaluation of clinical trials in reactions to sulfites. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 1986, 78, 191–201. [CrossRef]

- Rowland IR, Grasso P (1975) Degradation of n-nitrosamines by intestinal bacteria. Applied Microbiology.

- Sáenz-Navajas MP, Sánchez C et al (2023) Natural versus conventional production of Spanish white wines: an exploratory study Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. [CrossRef]

- Scott CT, DeFrancesco L Selling long life. Nature Biotechnology 2015, 33, 31–40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedley, L. (2023). Epigenetics. In T. G. Dinan (Ed.), Nutritional Psychiatry: A Primer for Clinicians, pp. 172–211 Cambridge University Press.

- Sedley, L. (2025). The epigenetics and biological clock of skin cancer. The Institute of Environment and Nutritional Epigenetics. [Preprint].

- Simmons A (1796) American cookery or the art of dressing viands fish poultry and vegetables. Hudson Goodwin, Hartford.

- Sharif AH, Iqbal M, Manhoosh B, Gholampoor N, Ma D, Marwah M, Sanchez-Aranguren L Hydrogen Sulphide-Based Therapeutics for Neurological Conditions: Perspectives and Challenges. Neurochemical Ressearch 2023, 48, 1981–1996. [CrossRef]

- Song P, Wu L et al Dietary nitrates nitrites and nitrosamines intake and the risk of gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9872–9895. [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama Y, Seita A Kanehiro Takaki and the control of beriberi in the Japanese Navy. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 2013, 106, 332–334. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki TM N-nitrosamine formation by intestinal bacteria. IARC Sci Publ 1984, 57, 275–281.

- Suzuki U, Shimamura TT About one active ingredient in rice bran. Tokyo Chemical Society 1911, 32, 4–17.

- Takaki B Three-lectures-on-the-preservation-of-health-amongst-the-personnel of the Japanese Navy and Army. Lancet 1906, 1451–1455.

- Taylor SW, Sun C et al A sulfated phosphorylated 7 kDa secreted peptide characterized by direct analysis of cell culture media. Journal of Proteome Research 2008, 7, 795–802. [CrossRef]

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia (2023) Barbarian. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/haggis. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (2014) Mediterranean diet: reducing cardiovascular disease risk.

- Tucker H (2011) Blood work: a tale of medicine and murder in the scientific revolution.

- Unspecified (1906) The barber the surgeon and the taster.

- Unspecified The new meat preserving process. Edinburgh Medical Journal 1866, 11, 676–678, Unspecified (1894) The treatment of disease by animal extracts. Hospital 345.

- Vally H, Misso N et al (2012) Adverse reactions to the sulphite additives.

- Valeggia CR, Snodgrass JJ Health of indigenous peoples. Annual Review Anthropology 2015, 44, 117–135. [CrossRef]

- Veeranki S, Tyagi SC Role of hydrogen sulfide in skeletal muscle biology and metabolism. Nitric Oxide 2015, 46, 66–71. [CrossRef]

- Webster LT, Pritchett IW Microbic virulence and host susceptibility in paratyphoid- enteritidis infection of white mice. Journal of Experimental Medicine 1924, 40, 397–404. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams RR, Waterman RE et al Studies of crystalline vitamin B1, III cleavage of vitamin with sulfite. Columbia University 1935, 57, 536–537.

- World Health Organisation (1999) Thiamine deficiency and its prevention and control in major emergencies, World Health Organisation. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NHD-99.13. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- Yu W, Zhou R et al (2023) Histone tyrosine sulfation by SULT1B1 regulates and gene transcription. Nature Chemical Biology.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).