Submitted:

06 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

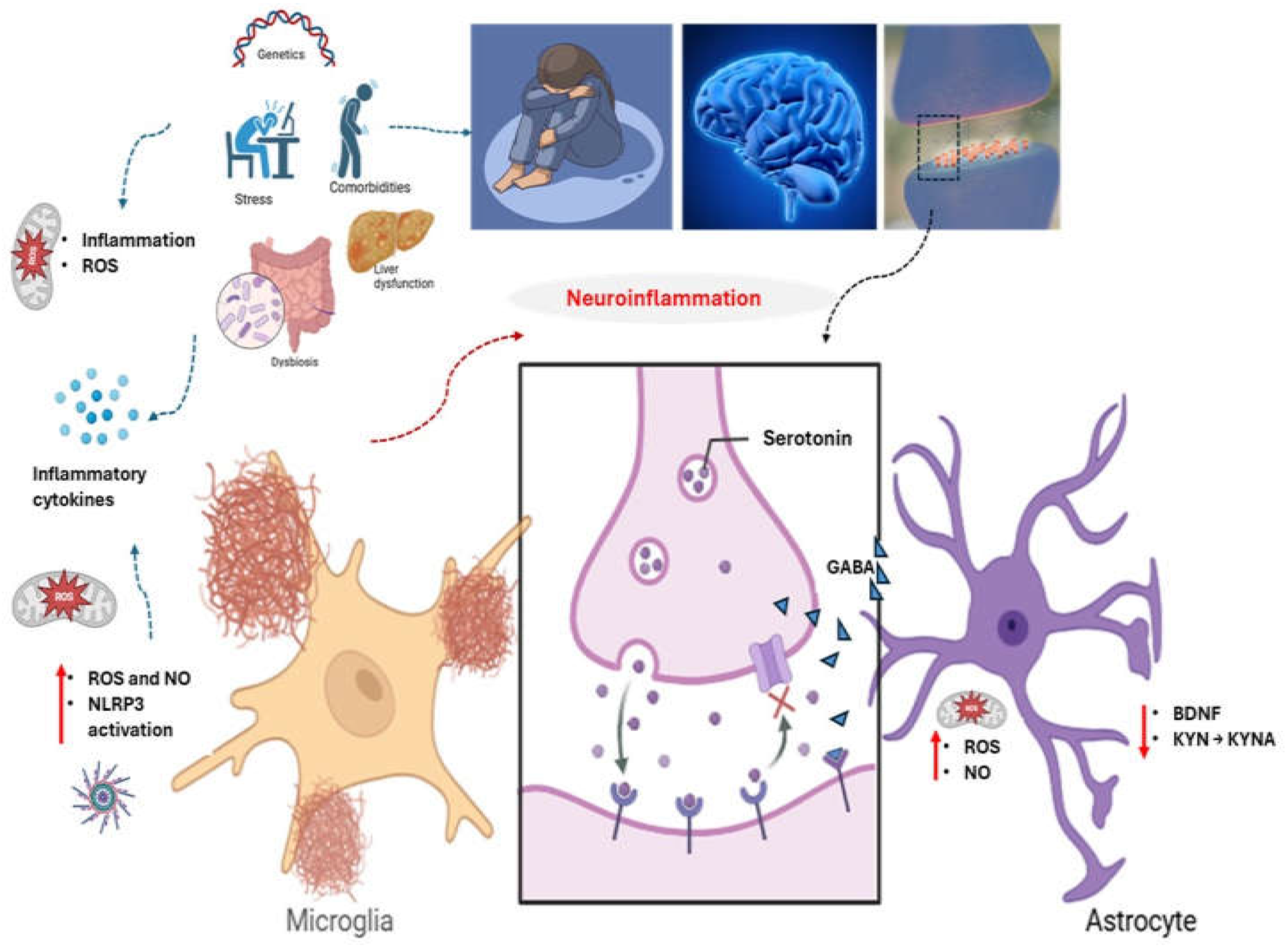

1. Introduction

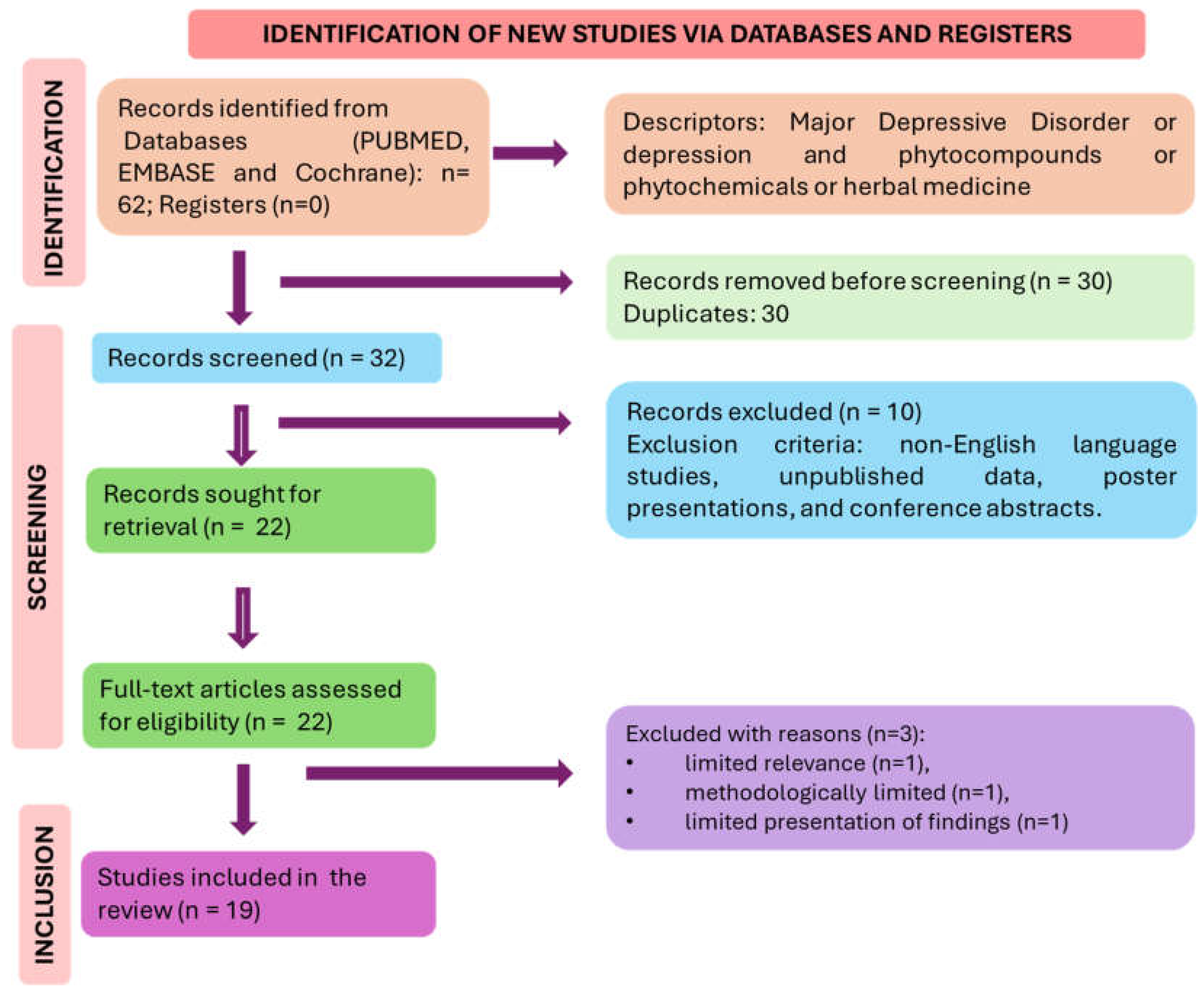

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focused Question

2.2. Language

2.3. Literature Search and Databases

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Search and Selection of the Relevant Articles

2.7. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search and Study Selection

| REFERENCE | MODEL/COUNTRY | POPULATION | INTERVENTION/ COMPARISON | OUTCOMES | SIDE EFFECTS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [48] | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial/ Iran |

42 patients with CSFP; 35–70 y, 25 ≤ body mass index < 40 kg/m2) | Participants received 80 mg/day nano-curcumin or placebo for 12 weeks. | Mental component summary scores significantly improved in the treated group; more patients with lower degrees of depression were found in the intervention group (p = 0.046). | Nausea, headache, diarrhea. | |

| [49] [50] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35745176/ (Não conseguimos citar, mas encontramos no endnote) [51] [52] [53] [54] [55] [56] |

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled / Iran. Randomized, simple blind, controlled/ South Korea. Randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled / Japan. Randomized, simple-blind, controlled / South Korea. Randomized, parallel and open/ Slovakia. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled/ United Kingdom. Randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled / Italy Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled/ Japan. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled/ Japan. |

76 individuals – all ♂ - 35 to 65 y. Study 40 young ♂ and ♀ with MDD – Age: 18 to 29 y. Study with 15 individuals – 4 (♂) and 11 (♀) – Age: 50–70 y. Study with 40 individuals – 16 (♂) and 24 (♀) – Age: 20-30 y. Study with 67 individuals of both sexes with MDD -20 (♂) and 47 (♀) -Age: 18-65 y. Study 1 with 21 individuals – 2 (♂) and 19 (♀) – Age: 18 - 21 y; Study 2 with 52 children – 23 (♂) and 29 (♀) – Age: 7 - 10 y. Study with 60 (♂) recently menopausal - 50 - 55 y. Study 87 women's who presented at least one symptom of menopause in MSS – Age: 40 - 60 y. Study with 91 women with at least one symptom of menopause – Age: 40 – 60 years. |

G1: quercetin, 500 mg/day; G2: placebo, 500 mg/day; for 8 weeks. G1: FR ou FL; They consumed FR or FL three times a day (30–60 minutes before breakfast, lunch, and dinner; 190 mL per bottle); for 8 weeks. G1: Potatoes – SQ - Naturally contains anthocyanins - containing 45 mg of anthocyanin; G2: Potatoes – Haruka; Subjects ate potatoes (75 g) cooked - microwaved for 2 min once a day / for 8 weeks, evaluated MSC counts and various stress responses. G1: FR or FL - 190 mL, twice daily (30–60 min before breakfast and dinner); for 8 weeks. G1: ESC + PYC (34 individuals – 11♂ and 23♀ - 10 to 20 mg/day of ESC+ 50 mg/day of PYC) or ESC no additional supplementation (33 individuals – 9♂ and 24♀ - 10 to 20 mg/day of ESC), for 12 weeks. G1: Flavonoid-rich WBB, with 253 mg of anthocyanins + 30 g of freeze-dried WBB with 30 mL of low-flavonoid Rocks Orange Squash and 220 mL of water; G2: vitamin C (4 mg), sugars (8.90 g fructose, 7.99 g glucose), 30 mL Rocks Orange Squash and 220 mL water; Study 2 content identical to study 1, but with 170 ml of water. Não achamos o tempo do estudo. G1: food supplement with 200 mg of fermented soy (with 10 mg of equol + 80 mg of isoflavone aglycones) + 25 mg of resveratrol (1 tablet/day) G2: placebo; for 12 weeks. G1: ultra-low dose (12.5 mg/day) or low dose (25 mg/day) isoflavone aglycone tablets; G2: placebo; for 8 weeks G1: low dose (100 mg/day – 25 mg of GSPE - 33 women) or high dose (200 mg/day – 50 mg of GSPE - 32 women) – GSPE tablets; G2: Placebo – 0 mg of GSPE - 38 women In both groups, women were instructed to take 4 tablets per day at any time of the day; For 8 weeks. |

G1: depression rates decreased significantly in the quercetin group post-intervention [median (IQR): −1.00 (6.00); P = 0.04) but not compared with the placebo group. Orange flavonoid interventions significantly improved HAMD-17, BDI, and CES-D scores in patients with MDD. In addition to having probiotics potential in the treatment of depression. Intake of SQ significantly improved the response to psychological stress, irritability and depression in BJSQ compared to "Haruka". The health benefits of anthocyanins are established, especially in preventing diseases related to oxidative stress. After the intervention, the mean CES-D scores in the FR and FL groups decreased to <20 points; Flavonoids exhibit a neuroprotective effect by counteracting inflammatory reactions Treatment with ESC reduced the MADRS score and extra administration of PYC did not bring about changes. In both studies, an increase in PA was observed 2 h after consumption of the WBB drink rich in flavonoids, but it had no effect on NA. The effect of flavonoids on mood was consistent across both populations. Treatment significantly reduced the number of individuals affected by depressive symptoms assessed by HAM-D. These significant improvements occurred at week 12 and were observed in work and activities (-94.1%) (p<0.001). G1 low dose: A significant improvement in the HADS score was obtained; AIS; MSS somatic symptoms after 4 to 8 weeks of treatment; In the ultra-low dose and placebo groups, there was no significant change in HADS and AIS. In the HADS-depression subscale, the score was not significantly changed in any of the groups, whereas in the HADS-anxiety subscale, the score in the low and high dose groups improved after 4 weeks of treatment. Furthermore, the change in the anxiety subscale score was substantially greater in the high-dose group than in the placebo group. |

G1: headache, joint pain, tingling in extremities, abdominal discomfort. No significant AD. No significant AD. No significant AD? No significant AD. No significant AD.? The most common adverse events associated with the use of resveratrol is mild diarrhea. No significant AD. No significant AD. |

|

| [57] | Block randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial / Iran (multicenter). | 50 patients with MS and Depression - 12% (♂) and 88% (♀); 18-55 y. | G1: 180 mg of ellagic acid - 90mg/2x day; G2: Placebo /12 weeks. |

Ellagic acid significantly reduced serum levels of IFN-γ, NO, and cortisol. It significantly increased serum levels of serotonin and BDNF and promoted a favorable effect in reducing BDI-II and EDSS scores. | No significant AD. | |

| [50] |

Randomized, simple blind, controlled/ South Korea. |

40 young ♂ and ♀ with MDD; 18 to 29 y. |

G1: FR or FL; Participants consumed FR or FL three times a day (30–60 minutes before breakfast, lunch, and dinner; 190 mL per bottle); for 8 weeks. | Orange flavonoid interventions significantly improved HAMD-17, BDI, and CES-D scores in patients with MDD. In addition to having probiotics potential in the treatment of depression. | No significant AD. |

|

| [58] |

Randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled / Japan. |

15 individuals – 4 (♂) and 11 (♀); 50–70 y. |

G1: Potatoes – SQ (contains anthocyanins 45 mg; G2: Potatoes – Haruka. Subjects ate potatoes (75 g) cooked - microwaved for 2 min once a day / for 8 weeks | Intake of SQ significantly improved the response to psychological stress, irritability, and depression in BJSQ compared to "Haruka". Anthocyanins can help preventing diseases related to oxidative stress. | No significant AD. |

|

| [59] | Randomized, controlled, exploratory study, clinical trial / United Kingdom. |

38 mothers who had babies under 12 months (baby age ranged from 5 to 48 weeks). | G1: 21 mothers (consumption of an average of 15.45 items with a high flavonoid content); G2: changes in their diet/ for 2 weeks. | Mothers who ate a high level of flavonoids had significantly lower state anxiety after the intervention. The quality of perceived physical health, perceived psychological health, and the quality of social relationships were significantly higher after the intervention | No significant AD. | |

| [60] |

Randomized, single-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover, parallel clinical trial / Spain. | 63 healthy young, middle-aged adults with overweight; 19♂) 44♀; 18-33 y. | G1: 2 groups, namely: 25g of SRP, and 32 g/day of PB; G2: 32g/day of CB /for 6 months or 7 months in some cases (pandemic). | The SRP groups; PB and CB showed a significant decrease in depression, with the P-value: (p= 0.007, p= 0.026 and p= 0.032, respectively). | n=5 in the SRP group: digestive symptoms; 3 who consumed PB or CB: softening of stool and reduced constipation. | |

| [61] | Multi-center, randomized, Open-Label with 4 parallel groups Intervention / France, Italy, Germany. | 125 participants (67 ♀, 70.4 y). | Participants of treated group received a diet rich in antioxidants (vitamin E, C, carotenoid, polyphenols), | In 2-month there was a reduction of depressive symptoms according to Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in the four arms | No serious AE. | |

| [62] | Randomized, controlled, parallel-group, single-blinded trial, /United Kingdom | 99 mildly hypertensive participants; 40–65 y | Patients were enrolled in a 4-week low polyphenol diet washout period and then randomized to an low polyphenol diet or an high polyphenol diet / 8 weeks. | High Polyphenol Diest group showed reduction in depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory-II), and an amelioration of mental health component scores | Not reported. | |

| [51] |

Randomized, simple-blind, controlled / South Korea. |

40 individuals – 16 (♂) and 24 (♀) –20-30 y. |

G1: FR or FL - 190 mL, twice daily (30–60 min before breakfast and dinner); 8 weeks. | After the intervention, the mean CES-D scores in the FR and FL groups decreased to <20 points; Flavonoids exhibit a neuroprotective effect by counteracting inflammatory reactions. | No significant AD |

|

| [52] |

Randomized, parallel, and open/ Slovakia. | 67 individuals of both sexes with MDD -20 (♂) and 47 (♀) - 18-65 y. |

G1: ESC + PYC (34 individuals – 11♂ and 23♀ - 10 to 20 mg/day of ESC+ 50 mg/day of PYC) or ESC no additional supplementation (33 individuals – 9♂ and 24♀ - 10 to 20 mg/day of ESC), for 12 weeks. | Treatment with ESC reduced the MADRS score, and extra administration of PYC did not bring about changes. |

No significant AD. |

|

| [63] | Randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial / Thailand, Brazil, Bulgaria, and Australia. | 61 patients who had at least 1 episode of MDD (♂/♀); 18-63 y. | G1: curcumin 500 - 1500 mg/day orally; G2: placebo /for 1 week; then 1 dose each week and after 4 weeks (1500 mg of curcumin/placebo); 12 to 16 weeks. | No significant difference in blood parameters, heart rate, and PR and QRS intervals between G1 and G2 curcumin improved MADRS score. | G1: dizziness; nausea/vomiting; insomnia; diarrhea; G2: dizziness; nausea/vomiting; insomnia. | |

| [54] | Randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled / Italy. | 60 (♂) recently menopausal; 50 - 55 y. |

G1: food supplement (200 mg of fermented soy/ 10 mg of equol + 80 mg of isoflavone aglycones) + 25 mg of resveratrol (1 tablet/day); G2: placebo; for 12 weeks. | Treatment significantly reduced the number of individuals affected by depressive symptoms assessed by HAM-D. These significant improvements occurred in week 12 and were observed in work and activities (-94.1%) (p<0.001). | The most common adverse event associated with the use of resveratrol is mild diarrhea. |

|

| [53] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled/ United Kingdom. |

Study 1 with 21 individuals – 2 (♂) and 19 (♀); 18 - 21 y; Study 2 with 52 children – 23 (♂) and 29 (♀); 7-10 y. |

G1: Flavonoid-rich WBB, with 253 mg of anthocyanins + 30 g of freeze-dried WBB with 30 mL of low-flavonoid Rocks Orange Squash (OS) and 220 mL of water; G2: vitamin C (4 mg), 30 mL Rocks OS, and 220 mL water; Study 2 content same as study 1, but with 170 ml of water. | In both studies, an increase in PA was observed 2 h after consumption of the WBB drink rich in flavonoids, but it had no effect on NA. The effect of flavonoids on mood was consistent across both populations. |

No significant AE |

|

| [55] |

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled/ Japan. |

87 women who presented at least one symptom of menopause in MSS;40 - 60 y. |

G1: ultra-low dose (12.5 mg/day) or low dose (25 mg/day) isoflavone aglycone tablets or G2: placebo/ 8 weeks |

G1 low dose: A significant improvement in the HADS score was obtained; AIS; MSS somatic symptoms after 4 to 8 weeks of treatment. There was no significant change in HADS and AIS in the ultra-low dose and placebo groups. | No significant AE |

|

| [64] |

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover, clinical trial / Iran and the United Kingdom. | 30 obese individuals - 83% (♀) and 17% (♂); mean age: 38.37 ± 11.51 y. | G1: curcumin, 1 g/day; G2: placebo/ 30 days; after that, inversion of the groups and perform the same intervention. |

G1: presented a significantly reduced mean BAI score; however, no significant impact on BDI scores. Therefore, curcumin has a potential anxiolytic effect on obese people. | No significant AE. |

|

| [56] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled/ Japan. | 91 women with at least one symptom of menopause; 40 – 60 years. | G1: low dose (100 mg/day – 25 mg of GSPE or high dose (200 mg/day – 50 mg of GSPE) – GSPE tablets; G2: Placebo – 0 mg of GSPE. In both groups, women were instructed to take 4 tablets per day at any time of the day for 8 weeks. | In the HADS-depression subscale, the score did not change significantly in any of the groups, whereas in the HADS-anxiety subscale, the score in the low and high-dose groups improved after 4 weeks. The change in the anxiety subscale score was substantially greater in the high-dose group than in the placebo group. | No significant AE. |

|

| [10] | Double-blind parallel trial / Australia | Participants: 39% ♂; 40–65 years | Participants consumed dark chocolate drink with 500 mg, 250 mg or 0 mg of polyphenols (placebo)/ once day / 30days. | The high dose polyphenols diet significantly increased self-rated calmness and contentedness compared to placebo. Mood scale and cognition was unchanged. | No AE | |

| [65] | Double blinded, randomised, clinical pilot crossover study/ United Kingdon |

10 participants | Comparison of a high polyphenol chocolate with iso-calorific chocolate (cocoa liquor free/low polyphenols). | The Hospital Anxiety and Depression score showed improvement after the consumption of olyphenol rich chocolate but deteriorated after isocaloric diet. | No AE | |

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

| STUDY | QUESTION FOCUS | APPROPRIATE RANDOMIZATION | ALLOCATION BLINDING - | DOUBLE-BLIND | LOSSES (<20%) | PROGNOSTICS DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS | OUTCOMES | ITT |

| [48] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| [49] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| [57] | Yes | Yes | Triple-blinded | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [50] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [58] | Yes | Yes | Ye | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| [59] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No? |

| [60] | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| [51] | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes? |

| [62] | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| [61] | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| [52] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [63] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [54] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [53] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| [55] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| [64] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [56] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| [10] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| [65] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

3.3. Summary of Findings

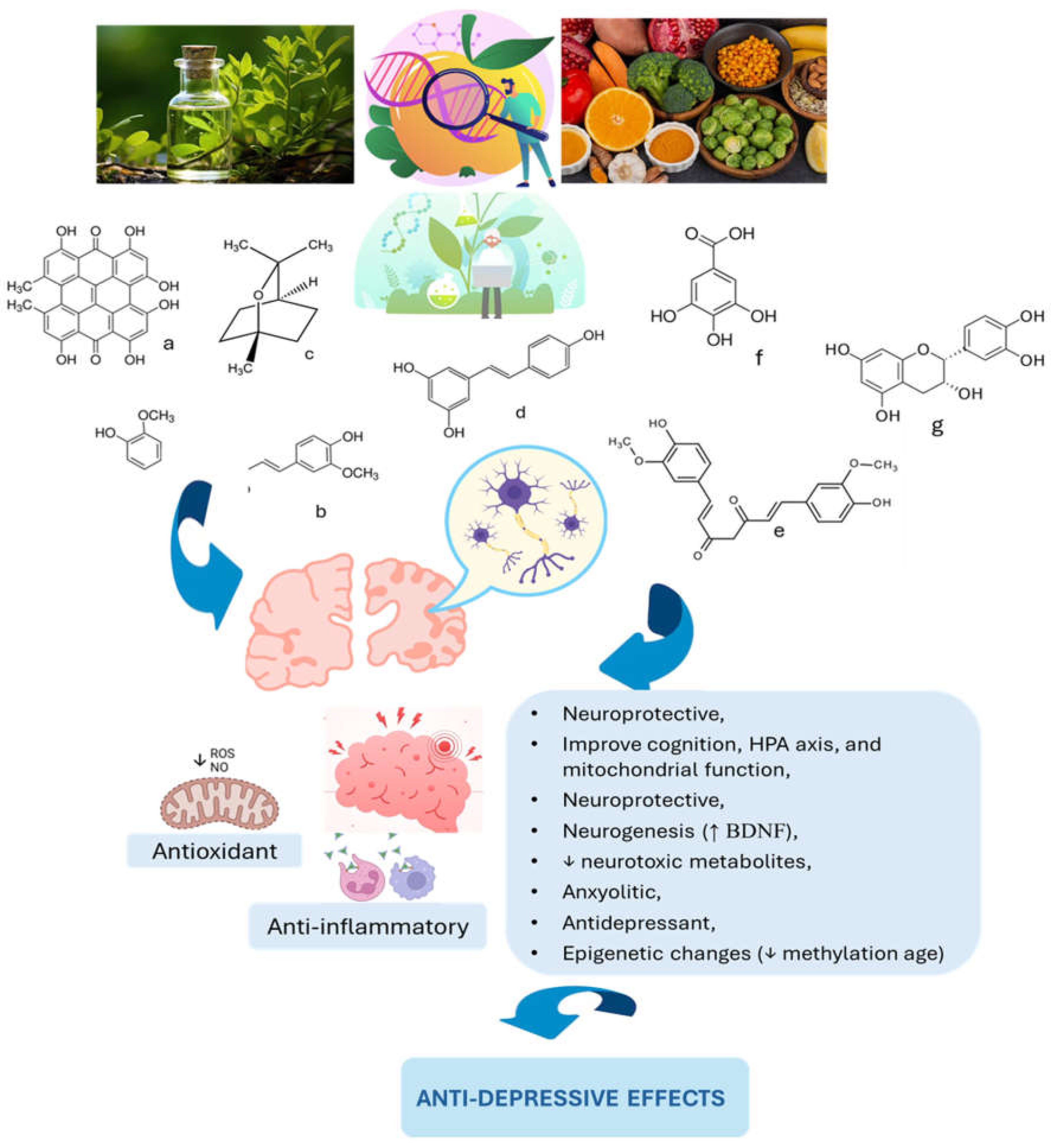

4. Synthesis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| HAM-D | Hamilton depression rating scale |

| IL | Interleukin |

| MMA | methylmalonic acid |

| MDD | major depressive disorder |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SSRI | selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

| TCA | tricyclic antidepressant |

References

- Manosso, L.M.; Arent, C.O.; Borba, L.A.; Abelaira, H.M.; Réus, G.Z. Natural Phytochemicals for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder: A Mini-Review of Pre- and Clinical Studies. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2023, 22, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Suzuki, K.; Kavalali, E.T.; Monteggia, L.M. Ketamine: Mechanisms and Relevance to Treatment of Depression. Annu Rev Med 2024, 75, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeller, F.; Jain, A.; Adrien, V.; Maes, P.; Reggente, N. Aesthetic chills mitigate maladaptive cognition in depression. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Averina, O.V.; Poluektova, E.U.; Zorkina, Y.A.; Kovtun, A.S.; Danilenko, V.N. Human Gut Microbiota for Diagnosis and Treatment of Depression. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagby, S.P.; Martin, D.; Chung, S.T.; Rajapakse, N. From the outside in: biological mechanisms linking social and environmental exposures to chronic disease and to health disparities. American journal of public health 2019, 109, S56–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusar-Poli, P.; Tantardini, M.; De Simone, S.; Ramella-Cravaro, V.; Oliver, D.; Kingdon, J.; Kotlicka-Antczak, M.; Valmaggia, L.; Lee, J.; Millan, M. Deconstructing vulnerability for psychosis: meta-analysis of environmental risk factors for psychosis in subjects at ultra high-risk. European Psychiatry 2017, 40, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesch, K.-P. When the serotonin transporter gene meets adversity: the contribution of animal models to understanding epigenetic mechanisms in affective disorders and resilience. Molecular and functional models in neuropsychiatry 2011, 251–280. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, R.L.; Lei, M.K.; Stewart, E.A.; Beach, S.R.; Brody, G.H.; Philibert, R.A.; Gibbons, F.X. Social adversity, genetic variation, street code, and aggression: A genetically informed model of violent behavior. Youth violence and juvenile justice 2012, 10, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, M.; Li, B. Major depressive disorder: hypothesis, mechanism, prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pase, M.P.; Scholey, A.B.; Pipingas, A.; Kras, M.; Nolidin, K.; Gibbs, A.; Wesnes, K.; Stough, C. Cocoa polyphenols enhance positive mood states but not cognitive performance: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 2013, 27, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Hou, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhao, X. Flavonoids for depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2023, 63, 8839–8849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Liu, T.; Jiang, P.; Dang, R. The interaction between autophagy and neuroinflammation in major depressive disorder: from pathophysiology to therapeutic implications. Pharmacological research 2021, 168, 105586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertollo, A.G.; Mingoti, M.E.D.; Ignácio, Z.M. Neurobiological mechanisms in the kynurenine pathway and major depressive disorder. Reviews in the Neurosciences 2025, 36, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Cai, X.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Y.; Pan, C.W.; Zhu, X.; Ke, C. Metabolomics on depression: A comparison of clinical and animal research. J Affect Disord 2024, 349, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Leme Boaro, B.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Patočka, J.; Barbalho Lamas, C.; Tanaka, M.; Laurindo, L.F. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Neuroinflammation Intervention with Medicinal Plants: A Critical and Narrative Review of the Current Literature. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.P.; Laurindo, L.F.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Direito, R.; Tanaka, M.; Jasmin Santos German, I.; Lamas, C.B.; Guiguer, E.L.; Araújo, A.C.; Fiorini, A.M.R.; et al. Polyphenols, Alkaloids, and Terpenoids Against Neurodegeneration: Evaluating the Neuroprotective Effects of Phytocompounds Through a Comprehensive Review of the Current Evidence. Metabolites 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.P.; Tanaka, M.; Lamas, C.B.; Quesada, K.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Araújo, A.C.; Guiguer, E.L.; Catharin, V.; de Castro, M.V.M.; Junior, E.B.; et al. Vascular Impairment, Muscle Atrophy, and Cognitive Decline: Critical Age-Related Conditions. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, K.; Beier, K.; Mardis, T.; Munoz, B.; Zaidi, A. The Neurochemistry of Depression: The Good, The Bad and The Ugly. Mo Med 2024, 121, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, R.; Khan, M.; Shah, S.A.; Saeed, K.; Kim, M.O. Natural antioxidant anthocyanins—A hidden therapeutic candidate in metabolic disorders with major focus in neurodegeneration. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Xu, X.; Chen, X.; Qi, W.; Lu, J.; Yan, X.; Zhao, D.; Cong, D.; Li, X.; Sun, L. Protective effect of pig brain polypeptides against corticosterone-induced oxidative stress, inflammatory response, and apoptosis in PC12 cells. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2019, 115, 108890. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Chen, Z.; Leng, S.X. Connection between systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation underlies neuroprotective mechanism of several phytochemicals in neurodegenerative diseases. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2018, 2018, 1972714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Avenanti, A.; Vécsei, L.; Tanaka, M. Neural correlates and molecular mechanisms of memory and learning. 2024, 25, 2724.

- Yoder, R.; Michaud, A.; Feagans, A.; Hinton-Froese, K.E.; Meyer, A.; Powers, V.A.; Stalnaker, L.; Hord, M.K. Family-Based Treatment for Anxiety, Depression, and ADHD for a Parent and Child. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J.; Machado, M.; Dias-Teixeira, M.; Ferraz, R.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Grosso, C. The neuroprotective effect of traditional Chinese medicinal plants—A critical review. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2023, 13, 3208–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajao, A.A.-n.; Sabiu, S.; Balogun, F.O.; Adekomi, D.A.; Saheed, S.A. The Ambit of Phytotherapy in Psychotic Care. In Psychosis-Biopsychosocial and Relational Perspectives; IntechOpen: 2018.

- Rajpal, V.R.; Koul, H.K.; Raina, S.N.; Kumar, H.M.S.; Qazi, G.N. Phytochemicals for Human Health: The Emerging Trends and Prospects. Curr Top Med Chem 2024, 24, v–vi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.M.S.; Rajpal, V.R.; Koul, H.K.; Raina, S.N.; Qazi, G.N. Phytochemicals for Human Health: The Emerging Trends and Prospects, Part-3. Curr Top Med Chem 2024, 24, 1011–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Bai, W. Bioactive phytochemicals. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2019, 59, 827–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fais, A.; Era, B. Phytochemical Composition and Biological Activity. Plants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscolo, A.; Mariateresa, O.; Giulio, T.; Mariateresa, R. Oxidative Stress: The Role of Antioxidant Phytochemicals in the Prevention and Treatment of Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Cao, G.; Zhao, D.; Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Yan, M. Ethnic, Botanic, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of the. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.; Stafford, G.I.; Makunga, N.P. Skeletons in the closet? Using a bibliometric lens to visualise phytochemical and pharmacological activities linked to. Front Plant Sci 2024, 15, 1268101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, G.; Ganesan, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, F.; Zheng, Y. Ononin ameliorates depression-like behaviors by regulating BDNF-TrkB-CREB signaling in vitro and in vivo. J Ethnopharmacol 2024, 320, 117375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. From Lab to Life: Exploring Cutting-Edge Models for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seung, H.-B.; Kwon, H.-J.; Kwon, C.-Y.; Kim, S.-H. Neuroendocrine Biomarkers of Herbal Medicine for Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaberi, K.R.; Alamdari-Palangi, V.; Savardashtaki, A.; Vatankhah, P.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Tajbakhsh, A.; Sahebkar, A. Modulatory Effects of Phytochemicals on Gut-Brain Axis: Therapeutic Implication. Curr Dev Nutr 2024, 8, 103785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liloia, D.; Zamfira, D.A.; Tanaka, M.; Manuello, J.; Crocetta, A.; Keller, R.; Cozzolino, M.; Duca, S.; Cauda, F.; Costa, T. Disentangling the role of gray matter volume and concentration in autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analytic investigation of 25 years of voxel-based morphometry research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2024, 105791. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, C.C.; Choisy, P. Medicinal plants meet modern biodiversity science. Curr Biol 2024, 34, R158–R173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakarla, R.; Karuturi, P.; Siakabinga, Q.; Kasi Viswanath, M.; Dumala, N.; Guntupalli, C.; Nalluri, B.N.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Prasanna, V.S.; Gutti, G.; et al. Current understanding and future directions of cruciferous vegetables and their phytochemicals to combat neurological diseases. Phytother Res 2024, 38, 1381–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, P.; Thapa, K.; Kanojia, N.; Rani, L.; Singh, T.G.; Rohilla, P. Exploring Therapeutic Potential of Phytoconstituents as a Gut Microbiota Modulator in the Management of Neurological and Psychological Disorders. Neuroscience 2024, 551, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. From Serendipity to Precision: Integrating AI, Multi-Omics, and Human-Specific Models for Personalized Neuropsychiatric Care. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. Beyond the boundaries: Transitioning from categorical to dimensional paradigms in mental health diagnostics. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2024, 33, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, M.L.d.S.; Martins, V.G.d.Q.A.; Silva, A.P.d.; Rocha, H.A.O.; Rachetti, V.d.P.S.; Scortecci, K.C. Phenolic acids as antidepressant agents. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazilat, S.; Tahmasbi, F.; Mirzaei, M.R.; Sanaie, S.; Yousefi, Z.; Asnaashari, S.; Yaqoubi, S.; Mohammadi, A.B.; Araj-khodaei, M. A systematic review on the use of phytotherapy in managing clinical depression. BioImpacts 2024, 15, 30532–30532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.J.A.I.M. Liberat i A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Chandler, J.; Welch, V.A.; Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J.J.T.C.d.o.s.r. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2019, 2019.

- Soltani, M.; Hosseinzadeh-Attar, M.J.; Rezaei, M.; Alipoor, E.; Vasheghani-Farahani, A.; Yaseri, M.; Rezayat, S.M. Effect of nano-curcumin supplementation on cardiometabolic risk factors, physical and psychological quality of life, and depression in patients with coronary slow flow phenomenon: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Trials 2024, 25, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehghani, F.; Vafa, M.; Ebrahimkhani, A.; Găman, M.A.; Sezavar Seyedi Jandaghi, S.H. Effects of quercetin supplementation on endothelial dysfunction biomarkers and depression in post-myocardial infarction patients: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2023, 56, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, M.; Lee, H.J. Effects of Flavonoid-Rich Orange Juice Intervention on Major Depressive Disorder in Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Choi, J.; Lee, H.J. Flavonoid-Rich Orange Juice Intake and Altered Gut Microbiome in Young Adults with Depressive Symptom: A Randomized Controlled Study. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetanka, A.; Stara, V.; Farsky, I.; Tonhajzerova, I.; Ondrejka, I. Pycnogenol supplementation as an adjunct treatment for antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. Physiol Int 2019, 106, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Barfoot, K.L.; May, G.; Lamport, D.J.; Reynolds, S.A.; Williams, C.M. Effects of Acute Blueberry Flavonoids on Mood in Children and Young Adults. Nutrients 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davinelli, S.; Scapagnini, G.; Marzatico, F.; Nobile, V.; Ferrara, N.; Corbi, G. Influence of equol and resveratrol supplementation on health-related quality of life in menopausal women: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Maturitas 2017, 96, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirose, A.; Terauchi, M.; Akiyoshi, M.; Owa, Y.; Kato, K.; Kubota, T. Low-dose isoflavone aglycone alleviates psychological symptoms of menopause in Japanese women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2016, 293, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terauchi, M.; Horiguchi, N.; Kajiyama, A.; Akiyoshi, M.; Owa, Y.; Kato, K.; Kubota, T. Effects of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract on menopausal symptoms, body composition, and cardiovascular parameters in middle-aged women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Menopause 2014, 21, 990–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajiluian, G.; Karegar, S.J.; Shidfar, F.; Aryaeian, N.; Salehi, M.; Lotfi, T.; Farhangnia, P.; Heshmati, J.; Delbandi, A.A. The effects of Ellagic acid supplementation on neurotrophic, inflammation, and oxidative stress factors, and indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase gene expression in multiple sclerosis patients with mild to moderate depressive symptoms: A randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phytomedicine 2023, 121, 155094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda-Yamamoto, M.; Honmou, O.; Sasaki, M.; Haseda, A.; Kagami-Katsuyama, H.; Shoji, T.; Namioka, A.; Namioka, T.; Magota, H.; Oka, S.; et al. The Impact of Purple-Flesh Potato (Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Barfoot, K.L.; Forster, R.; Lamport, D.J. Mental Health in New Mothers: A Randomised Controlled Study into the Effects of Dietary Flavonoids on Mood and Perceived Quality of Life. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parilli-Moser, I.; Domínguez-López, I.; Trius-Soler, M.; Castellví, M.; Bosch, B.; Castro-Barquero, S.; Estruch, R.; Hurtado-Barroso, S.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Consumption of peanut products improves memory and stress response in healthy adults from the ARISTOTLE study: A 6-month randomized controlled trial. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2021, 40, 5556–5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdel-Marchasson, I.; Ostan, R.; Regueme, S.C.; Pinto, A.; Pryen, F.; Charrouf, Z.; d'Alessio, P.; Baudron, C.R.; Guerville, F.; Durrieu, J.; et al. Quality of Life: Psychological Symptoms-Effects of a 2-Month Healthy Diet and Nutraceutical Intervention; A Randomized, Open-Label Intervention Trial (RISTOMED). Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogianni, M.D.; Vijayakumar, A.; Rooney, C.; Noad, R.L.; Appleton, K.M.; McCarthy, D.; Donnelly, M.; Young, I.S.; McKinley, M.C.; McKeown, P.P.; et al. A High Polyphenol Diet Improves Psychological Well-Being: The Polyphenol Intervention Trial (PPhIT). Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanatawan, B.; Tangwongchai, S.; Sughondhabhirom, A.; Suppapitiporn, S.; Hemrunrojn, S.; Carvalho, A.F.; Maes, M. Add-on Treatment with Curcumin Has Antidepressive Effects in Thai Patients with Major Depression: Results of a Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Neurotox Res 2018, 33, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaily, H.; Sahebkar, A.; Iranshahi, M.; Ganjali, S.; Mohammadi, A.; Ferns, G.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M. An investigation of the effects of curcumin on anxiety and depression in obese individuals: A randomized controlled trial. Chin J Integr Med 2015, 21, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyapalan, T.; Beckett, S.; Rigby, A.S.; Mellor, D.D.; Atkin, S.L. High cocoa polyphenol rich chocolate may reduce the burden of the symptoms in chronic fatigue syndrome. Nutrition journal 2010, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Garg, M.; Prajapati, P.; Singh, P.K.; Chopra, R.; Kumari, A.; Mittal, A. Adaptogenic property of Asparagus racemosus: Future trends and prospects. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Szabó, Á.; Vécsei, L.; Giménez-Llort, L. Emerging translational research in neurological and psychiatric diseases: from in vitro to in vivo models. 2023, 24, 15739.

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. A decade of dedication: pioneering perspectives on neurological diseases and mental illnesses. 2024, 12, 1083.

- Kessler, R.C.; van Loo, H.M.; Wardenaar, K.J.; Bossarte, R.M.; Brenner, L.; Ebert, D.; De Jonge, P.; Nierenberg, A.; Rosellini, A.; Sampson, N. Using patient self-reports to study heterogeneity of treatment effects in major depressive disorder. Epidemiology and psychiatric sciences 2017, 26, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malgaroli, M.; Calderon, A.; Bonanno, G.A. Networks of major depressive disorder: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review 2021, 85, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mew, E.J.; Monsour, A.; Saeed, L.; Santos, L.; Patel, S.; Courtney, D.B.; Watson, P.N.; Szatmari, P.; Offringa, M.; Monga, S. Systematic scoping review identifies heterogeneity in outcomes measured in adolescent depression clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2020, 126, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Zhang, J. Neuroinflammation, memory, and depression: new approaches to hippocampal neurogenesis. J Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurcau, A.; Simion, A. Neuroinflammation in Cerebral Ischemia and Ischemia/Reperfusion Injuries: From Pathophysiology to Therapeutic Strategies. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornari Laurindo, L.; Aparecido Dias, J.; Cressoni Araújo, A.; Torres Pomini, K.; Machado Galhardi, C.; Rucco Penteado Detregiachi, C.; Santos de Argollo Haber, L.; Donizeti Roque, D.; Dib Bechara, M.; Vialogo Marques de Castro, M.; et al. Immunological dimensions of neuroinflammation and microglial activation: exploring innovative immunomodulatory approaches to mitigate neuroinflammatory progression. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1305933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Barbalho, S.M.; Araújo, A.C.; Guiguer, E.L.; Mondal, A.; Bachtel, G.; Bishayee, A. Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) in Health and Disease: A Critical Review. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Simili, O.A.G.; Araújo, A.C.; Guiguer, E.L.; Direito, R.; Valenti, V.E.; de Oliveira, V.; de Oliveira, J.S.; Yanaguizawa Junior, J.L.; Dias, J.A.; et al. Melatonin from Plants: Going Beyond Traditional Central Nervous System Targeting-A Comprehensive Review of Its Unusual Health Benefits. Biology (Basel) 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Tuka, B.; Vécsei, L. Navigating the Neurobiology of Migraine: From pathways to potential therapies. 2024, 13, 1098.

- Zanella, I. Neuroinflammation: From Molecular Basis to Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassamal, S. Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1130989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletti, S.; Mazza, M.G.; Benedetti, F. Inflammatory mediators in major depression and bipolar disorder. Transl Psychiatry 2024, 14, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.Y.; Guo, Y.X.; Lian, W.W.; Yan, Y.; Ma, B.Z.; Cheng, Y.C.; Xu, J.K.; He, J.; Zhang, W.K. The NLRP3 inflammasome in depression: Potential mechanisms and therapies. Pharmacol Res 2023, 187, 106625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Li, W.; Chen, P.; Wang, L.; Bao, X.; Huang, R.; Liu, G.; Chen, X. Microglial NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation and therapeutic strategies in depression. Neural Regen Res 2024, 19, 1890–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakasugi, D.; Kondo, S.; Ferdousi, F.; Mizuno, S.; Yada, A.; Tominaga, K.; Takahashi, S.; Isoda, H. A rare olive compound oleacein functions as a TrkB agonist and mitigates neuroinflammation both in vitro and in vivo. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, Y. Progress of plant polyphenol extracts in treating depression by anti-neuroinflammatory mechanism: A review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024, 103, e37151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, A.; Dolcetti, E.; Rizzo, F.R.; Fresegna, D.; Musella, A.; Gentile, A.; De Vito, F.; Caioli, S.; Guadalupi, L.; Bullitta, S.; et al. Corrigendum: Inflammation-Associated Synaptic Alterations as Shared Threads in Depression and Multiple Sclerosis. Front Cell Neurosci 2020, 14, 647259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Q.; Escobar Galvis, M.L.; Madaj, Z.B.; Keaton, S.A.; Smart, L.; Edgerly, Y.M.; Anis, E.; Leach, R.; Osborne, L.M.; Achtyes, E.; et al. Dysregulated placental expression of kynurenine pathway enzymes is associated with inflammation and depression in pregnancy. Brain Behav Immun 2024, 119, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtyes, E.; Keaton, S.A.; Smart, L.; Burmeister, A.R.; Heilman, P.L.; Krzyzanowski, S.; Nagalla, M.; Guillemin, G.J.; Escobar Galvis, M.L.; Lim, C.K.; et al. Inflammation and kynurenine pathway dysregulation in post-partum women with severe and suicidal depression. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 83, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. Revolutionizing our understanding of Parkinson’s disease: Dr. Heinz Reichmann’s pioneering research and future research direction. Journal of Neural Transmission 2024, 1-21.

- Pontillo, G.; Cepas, M.B.; Broeders, T.A.A.; Koubiyr, I.; Schoonheim, M.M. Network Analysis in Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2024, 34, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Gao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, A.; Li, G.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; et al. Immunoregulatory role of the gut microbiota in inflammatory depression. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Galindo, L.S.; Gonzalez-Escamilla, G.; Fleischer, V.; Grotegerd, D.; Meinert, S.; Ciolac, D.; Person, M.; Stein, F.; Brosch, K.; Nenadić, I.; et al. Concurrent inflammation-related brain reorganization in multiple sclerosis and depression. Brain Behav Immun 2024, 119, 978–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, P.; Sun, Y.; Li, L. Mitochondrial dysfunction in chronic neuroinflammatory diseases (Review). Int J Mol Med 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, T.; You, F. Oxidative Stress and Bio-Regulation. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.; Nagappa, A.N.; Patil, C.R. Role of oxidative stress in depression. Drug Discov Today 2020, 25, 1270–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Deng, Z.; Lei, C.; Ding, X.; Li, J.; Wang, C. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Tumorigenesis and Progression. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.S.; Cardoso, A.; Vale, N. Oxidative Stress in Depression: The Link with the Stress Response, Neuroinflammation, Serotonin, Neurogenesis and Synaptic Plasticity. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilavská, L.; Morvová, M.; Paduchová, Z.; Muchová, J.; Garaiova, I.; Ďuračková, Z.; Šikurová, L.; Trebatická, J. The kynurenine and serotonin pathway, neopterin and biopterin in depressed children and adolescents: an impact of omega-3 fatty acids, and association with markers related to depressive disorder. A randomized, blinded, prospective study. Front Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1347178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, Á.; Galla, Z.; Spekker, E.; Szűcs, M.; Martos, D.; Takeda, K.; Ozaki, K.; Inoue, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Toldi, J. Oxidative and Excitatory Neurotoxic Stresses in CRISPR/Cas9-Induced Kynurenine Aminotransferase Knock-out Mice: A Novel Model for Experience-Based Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. 2024.

- Larrea, A.; Sánchez-Sánchez, L.; Diez-Martin, E.; Elexpe, A.; Torrecilla, M.; Astigarraga, E.; Barreda-Gómez, G. Mitochondrial Metabolism in Major Depressive Disorder: From Early Diagnosis to Emerging Treatment Options. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lu, M.; Lyu, Q.; Shi, L.; Zhou, C.; Li, M.; Feng, S.; Liang, X.; Zhou, X.; Ren, L. Mitochondrial dynamics dysfunction: Unraveling the hidden link to depression. Biomed Pharmacother 2024, 175, 116656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martos, D.; Lőrinczi, B.; Szatmári, I.; Vécsei, L.; Tanaka, M. The impact of C-3 side chain modifications on Kynurenic Acid: a behavioral analysis of its analogs in the Motor Domain. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, S.; Avenanti, A.; Vécsei, L.; Tanaka, M. Neurodegeneration in cognitive impairment and mood disorders for experimental, clinical and translational neuropsychiatry. 2024, 12, 574.

- Cao, Y.; Chen, H.; Tan, Y.; Yu, X.D.; Xiao, C.; Li, Y.; Reilly, J.; He, Z.; Shu, X. Protection of p-Coumaric acid against chronic stress-induced neurobehavioral deficits in mice via activating the PKA-CREB-BDNF pathway. Physiol Behav 2024, 273, 114415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Cao, H.; Zuo, C.; Gu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Miao, J.; Fu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, F. Mitochondrial dysfunction: A fatal blow in depression. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 167, 115652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masenga, S.K.; Kabwe, L.S.; Chakulya, M.; Kirabo, A. Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress in Metabolic Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ren, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wei, J. Oxidative stress: The nexus of obesity and cognitive dysfunction in diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1134025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Garza, S.L.; Laveriano-Santos, E.P.; Moreno, J.J.; Bodega, P.; de Cos-Gandoy, A.; de Miguel, M.; Santos-Beneit, G.; Fernández-Alvira, J.M.; Fernández-Jiménez, R.; Martínez-Gómez, J.; et al. Metabolic syndrome, adiposity, diet, and emotional eating are associated with oxidative stress in adolescents. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1216445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, L.; Cen, M.; Fu, X.; Gao, X.; Zuo, Q.; Wu, J. Oxidative balance scores and depressive symptoms: Mediating effects of oxidative stress and inflammatory factors. J Affect Disord 2023, 334, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E. Effect of High-Fat Diets on Oxidative Stress, Cellular Inflammatory Response and Cognitive Function. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, Y.C.; Mendes, N.M.; Pereira de Lima, E.; Chehadi, A.C.; Lamas, C.B.; Haber, J.F.S.; Dos Santos Bueno, M.; Araújo, A.C.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; et al. Curcumin: A Golden Approach to Healthy Aging: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagotto, G.L.O.; Santos, L.; Osman, N.; Lamas, C.B.; Laurindo, L.F.; Pomini, K.T.; Guissoni, L.M.; Lima, E.P.; Goulart, R.A.; Catharin, V.; et al. Ginkgo biloba: A Leaf of Hope in the Fight against Alzheimer's Dementia: Clinical Trial Systematic Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, L.N.; Omine, A.; Laurindo, L.F.; Araújo, A.C.; Machado, N.M.; Dias, J.A.; Kavalakatt, J.; Banerjee, S.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; Atanasov, A.G.; et al. Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa Bonpl.) in health and disease: A narrative review. Food Chem 2025, 477, 143425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhuo, Y.; Wan, S.; Guo, R. Association between mitochondrial DNA levels and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Wang, L.; Sheng, H. Mitochondria in depression: The dysfunction of mitochondrial energy metabolism and quality control systems. CNS Neurosci Ther 2024, 30, e14576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valotto Neto, L.J.; Reverete de Araujo, M.; Moretti Junior, R.C.; Mendes Machado, N.; Joshi, R.K.; Dos Santos Buglio, D.; Barbalho Lamas, C.; Direito, R.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Tanaka, M.; et al. Investigating the Neuroprotective and Cognitive-Enhancing Effects of Bacopa monnieri: A Systematic Review Focused on Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Apoptosis. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaini, G.; Mason, B.L.; Diaz, A.P.; Jha, M.K.; Soares, J.C.; Trivedi, M.H.; Quevedo, J. Dysregulation of mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy and apoptosis in major depressive disorder: Does inflammation play a role? Molecular psychiatry 2022, 27, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, F.; Lin, G.; Su, L.; Xue, L.; Duan, K.; Chen, L.; Ni, J. The association between methylmalonic acid, a biomarker of mitochondrial dysfunction, and cause-specific mortality in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, S.; Wan, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Liang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yan, M.; Wu, P.; et al. Mitochondria-derived methylmalonic acid aggravates ischemia-reperfusion injury by activating reactive oxygen species-dependent ferroptosis. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, D. Associations of methylmalonic acid and depressive symptoms with mortality: a population-based study. Transl Psychiatry 2024, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.N.; Watanabe, F.; Koseki, K.; He, R.E.; Lee, H.L.; Chiu, T.H.T. Effect of roasted purple laver (nori) on vitamin B(12) nutritional status of vegetarians: a dose-response trial. European journal of nutrition 2024, 63, 3269–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, P.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Zheng, M.; Gao, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.H.; Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Albuhadily, A.K.; Hamad, R.S.; Alexiou, A.; Papadakis, M.; Saad, H.M.; Batiha, G.E. Role of brain renin-angiotensin system in depression: A new perspective. CNS Neurosci Ther 2024, 30, e14525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muha, J.; Schumacher, A.; Campisi, S.C.; Korczak, D.J. Depression and emotional eating in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appetite 2024, 200, 107511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekinci, G.N.; Sanlier, N. The relationship between nutrition and depression in the life process: A mini-review. Exp Gerontol 2023, 172, 112072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrzastek, Z.; Guligowska, A.; Sobczuk, P.; Kostka, T. Dietary factors, risk of developing depression, and severity of its symptoms in older adults-A narrative review of current knowledge. Nutrition 2023, 106, 111892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Travica, N.; Dissanayaka, T.; Ashtree, D.N.; Gauci, S.; Lotfaliany, M.; O'Neil, A.; Jacka, F.N.; Marx, W. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejtahed, H.S.; Mardi, P.; Hejrani, B.; Mahdavi, F.S.; Ghoreshi, B.; Gohari, K.; Heidari-Beni, M.; Qorbani, M. Association between junk food consumption and mental health problems in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmir, H.; Mahdavi, F.S.; Ejtahed, H.S.; Kazemian, E.; Chaharrahi, A.; Mohammadian Khonsari, N.; Mahdavi-Gorabi, A.; Qorbani, M. Junk food consumption and psychological distress in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Neurosci 2023, 26, 807–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, R.; Selvamani, T.Y.; Zahra, A.; Malla, J.; Dhanoa, R.K.; Venugopal, S.; Shoukrie, S.I.; Hamouda, R.K.; Hamid, P. Association Between Dietary Habits and Depression: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e32359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbachev, D.; Markina, E.; Chigareva, O.; Gradinar, A.; Borisova, N.; Syunyakov, T. Dietary Patterns as Modifiable Risk Factors for Depression: a Narrative Review. Psychiatr Danub 2023, 35, 423–431. [Google Scholar]

- Magzal, F.; Turroni, S.; Fabbrini, M.; Barone, M.; Vitman Schorr, A.; Ofran, A.; Tamir, S. A personalized diet intervention improves depression symptoms and changes microbiota and metabolite profiles among community-dwelling older adults. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1234549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, S.; Zheng, B.; Xu, H.; Long, W.; Xiong, X. Association between dietary intake and symptoms of depression and anxiety in pregnant women: Evidence from a community-based observational study. Food Sci Nutr 2023, 11, 7555–7564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaseem, A.; Owens, D.K.; Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta, I.; Tufte, J.E.; Cross, J.T.; Wilt, T.J.; Physicians, C.G.C.f.t.A.C.o. Nonpharmacologic and Pharmacologic Treatments of Adults in the Acute Phase of Major Depressive Disorder: A Living Clinical Guideline From the American College of Physicians (Version 1, Update Alert 2). Ann Intern Med 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direito, R.; Barbalho, S.M.; Sepodes, B.; Figueira, M.E. Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds: Exploring Neuroprotective, Metabolic, and Hepatoprotective Effects for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayes, A.; Parker, G. How to choose an antidepressant medication. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2019, 139, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillman, P.K. Tricyclic antidepressant pharmacology and therapeutic drug interactions updated. Br J Pharmacol 2007, 151, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, R.; Stenkrona, P.; Takano, A.; Svensson, J.; Andersson, M.; Nag, S.; Asami, Y.; Hirano, Y.; Halldin, C.; Lundberg, J. Venlafaxine ER Blocks the Norepinephrine Transporter in the Brain of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: a PET Study Using [18F]FMeNER-D2. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2019, 22, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A.F.; Sharma, M.S.; Brunoni, A.R.; Vieta, E.; Fava, G.A. The Safety, Tolerability and Risks Associated with the Use of Newer Generation Antidepressant Drugs: A Critical Review of the Literature. Psychother Psychosom 2016, 85, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishi, T.; Ikuta, T.; Sakuma, K.; Okuya, M.; Hatano, M.; Matsuda, Y.; Iwata, N. Antidepressants for the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder in the maintenance phase: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichniak, A.; Wierzbicka, A.; Walęcka, M.; Jernajczyk, W. Effects of Antidepressants on Sleep. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2017, 19, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Li, P.; Lv, X.; Lai, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, F.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yu, X.; et al. Adverse effects of 21 antidepressants on sleep during acute-phase treatment in major depressive disorder: a systemic review and dose-effect network meta-analysis. Sleep 2023, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beach, S.R.; Kostis, W.J.; Celano, C.M.; Januzzi, J.L.; Ruskin, J.N.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Huffman, J.C. Meta-analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-associated QTc prolongation. J Clin Psychiatry 2014, 75, e441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheysens, T.; Van Den Eede, F.; De Picker, L. The risk of antidepressant-induced hyponatremia: A meta-analysis of antidepressant classes and compounds. Eur Psychiatry 2024, 67, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, W. Reminiscence therapy-based care program alleviates anxiety and depression, as well as improves the quality of life in recurrent gastric cancer patients. Front Psychol 2023, 14, 1133470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, C.; Fornai, M.; Antonioli, L.; Blandizzi, C.; Calderone, V. Phytochemicals as Novel Therapeutic Strategies for NLRP3 Inflammasome-Related Neurological, Metabolic, and Inflammatory Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; de Carvalho, G.M.; de Oliveira Zanuso, B.; Figueira, M.E.; Direito, R.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; Buglio, D.S.; Barbalho, S.M. Curcumin-Based Nanomedicines in the Treatment of Inflammatory and Immunomodulated Diseases: An Evidence-Based Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikito, D.F.; Borges, A.C.A.; Laurindo, L.F.; Otoboni, A.; Direito, R.; Goulart, R.A.; Nicolau, C.C.T.; Fiorini, A.M.R.; Sinatora, R.V.; Barbalho, S.M. Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Other Health Effects of Dragon Fruit and Potential Delivery Systems for Its Bioactive Compounds. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.; Iqbal, H.; Kim, S.M.; Jin, M. Phytochemicals That Act on Synaptic Plasticity as Potential Prophylaxis against Stress-Induced Depressive Disorder. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2023, 31, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xi, Y.; Zhou, H.; Tang, Z.; Xiong, L.; Qin, D. Polyphenols: Natural Food-Grade Biomolecules for the Treatment of Nervous System Diseases from a Multi-Target Perspective. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yang, C.; Li, Z.; Li, T.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, T.; Zong, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, D.; et al. Flavonoid 4,4'-dimethoxychalcone selectively eliminates senescent cells via activating ferritinophagy. Redox Biol 2024, 69, 103017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Sun, Y.; Su, Y.; Guan, W.; Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, B.; Wang, Q.; Kuang, H. Luteolin: A promising multifunctional natural flavonoid for human diseases. Phytother Res 2024, 38, 3417–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmus, P.; Kozłowska, E. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Carotenoids in Mood Disorders: An Overview. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Direito, R.; Laurindo, L.F.; Marton, L.T.; Guiguer, E.L.; Goulart, R.A.; Tofano, R.J.; Carvalho, A.C.A.; Flato, U.A.P.; Capelluppi Tofano, V.A.; et al. Ginkgo biloba in the Aging Process: A Narrative Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Laurindo, L.F.; de Oliveira Zanuso, B.; da Silva, R.M.S.; Gallerani Caglioni, L.; Nunes Junqueira de Moraes, V.B.F.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Dogani Rodrigues, V.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Beluce, M.E.; et al. AdipoRon's Impact on Alzheimer's Disease-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buglio, D.S.; Marton, L.T.; Laurindo, L.F.; Guiguer, E.L.; Araújo, A.C.; Buchaim, R.L.; Goulart, R.A.; Rubira, C.J.; Barbalho, S.M. The Role of Resveratrol in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review. J Med Food 2022, 25, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, R.O.; Martins, L.F.; Tahiri, E.; Duarte, C.B. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-induced regulation of RNA metabolism in neuronal development and synaptic plasticity. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2022, 13, e1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadad, B.S.; Vargas-Medrano, J.; Ramos, E.I.; Najera, K.; Fagan, M.; Forero, A.; Thompson, P.M. Altered levels of interleukins and neurotrophic growth factors in mood disorders and suicidality: an analysis from periphery to central nervous system. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, A.; Batool, Z.; Sadir, S.; Liaquat, L.; Shahzad, S.; Tabassum, S.; Ahmad, S.; Kamil, N.; Perveen, T.; Haider, S. Therapeutic Potential of Curcumin in Reversing the Depression and Associated Pseudodementia via Modulating Stress Hormone, Hippocampal Neurotransmitters, and BDNF Levels in Rats. Neurochem Res 2021, 46, 3273–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idayu, N.F.; Hidayat, M.T.; Moklas, M.A.; Sharida, F.; Raudzah, A.R.; Shamima, A.R.; Apryani, E. Antidepressant-like effect of mitragynine isolated from Mitragyna speciosa Korth in mice model of depression. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Prabowo, W.C.; Arifuddin, M.; Fadraersada, J.; Indriyanti, N.; Herman, H.; Purwoko, R.Y.; Nainu, F.; Rahmadi, A.; Paramita, S.; et al. Species as Pharmacological Agents: From Abuse to Promising Pharmaceutical Products. Life (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Fei, S.; Olatunji, O.J. LC/ESI/TOF-MS Characterization, Anxiolytic and Antidepressant-like Effects of. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathinezhad, Z.; Sewell, R.D.E.; Lorigooini, Z.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. Depression and Treatment with Effective Herbs. Curr Pharm Des 2019, 25, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.; Bae, H. Therapeutic Effects of Phytochemicals and Medicinal Herbs on Depression. Biomed Res Int 2017, 2017, 6596241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manosso, L.M.; Arent, C.O.; Borba, L.A.; Abelaira, H.M.; Réus, G.Z. Natural Phytochemicals for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder: A Mini-Review of Pre-and Clinical Studies. CNS & Neurological Disorders-Drug Targets-CNS & Neurological Disorders) 2023, 22, 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Picheta, N.; Piekarz, J.; Daniłowska, K.; Mazur, K.; Piecewicz-Szczęsna, H.; Smoleń, A. Phytochemicals in the treatment of patients with depression: a systemic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1509109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Behl, T.; Rana, T.; Sehgal, A.; Wal, P.; Saxena, B.; Yadav, S.; Mohan, S.; Anwer, M.K.; Chigurupati, S. Exploring the pathophysiological influence of heme oxygenase-1 on neuroinflammation and depression: A study of phytotherapeutic-based modulation. Phytomedicine 2024, 155466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, N.; Everson, J.; Pariante, C.M.; Borsini, A. Modulation of microglial activation by antidepressants. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 2022, 36, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Siddiqui, S.; Husain, S.A.; Mazurek, S.; Iqbal, M.A. Phytocompounds Targeting Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer: An Assessment of Role, Mechanisms, Pathways, and Therapeutic Relevance. J Agric Food Chem 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzuto, G.; Calcabrini, A.; Colone, M.; Condello, M.; Dupuis, M.L.; Pellegrini, E.; Stringaro, A. Phytocompounds and Nanoformulations for Anticancer Therapy: A Review. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak-Celińska, A.; Studzińska-Sroka, E. New Avenues and Major Achievements in Phytocompounds Research for Glioblastoma Therapy. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).