Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Media, and Cultivation

2.2. Preparation of Linear Gradient Plates

2.3. Sample Preparation for Siderophore Screening Analysis

2.4. UHPLC-MS Method

3. Results

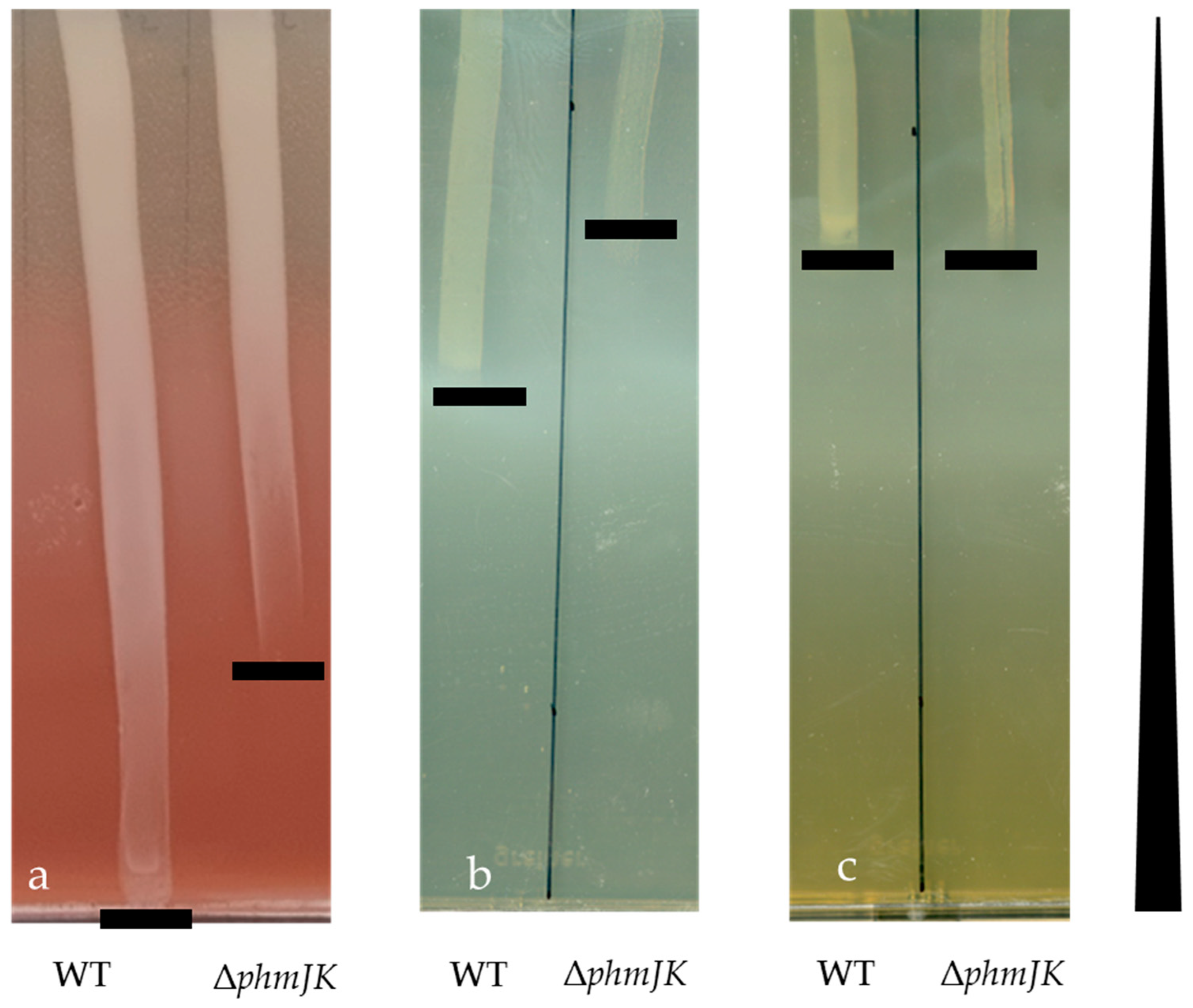

3.1. The Siderophore Phymabactin Is Important for the Growth of P. phymatum in Martian Soil and in Aluminium-Rich Medium

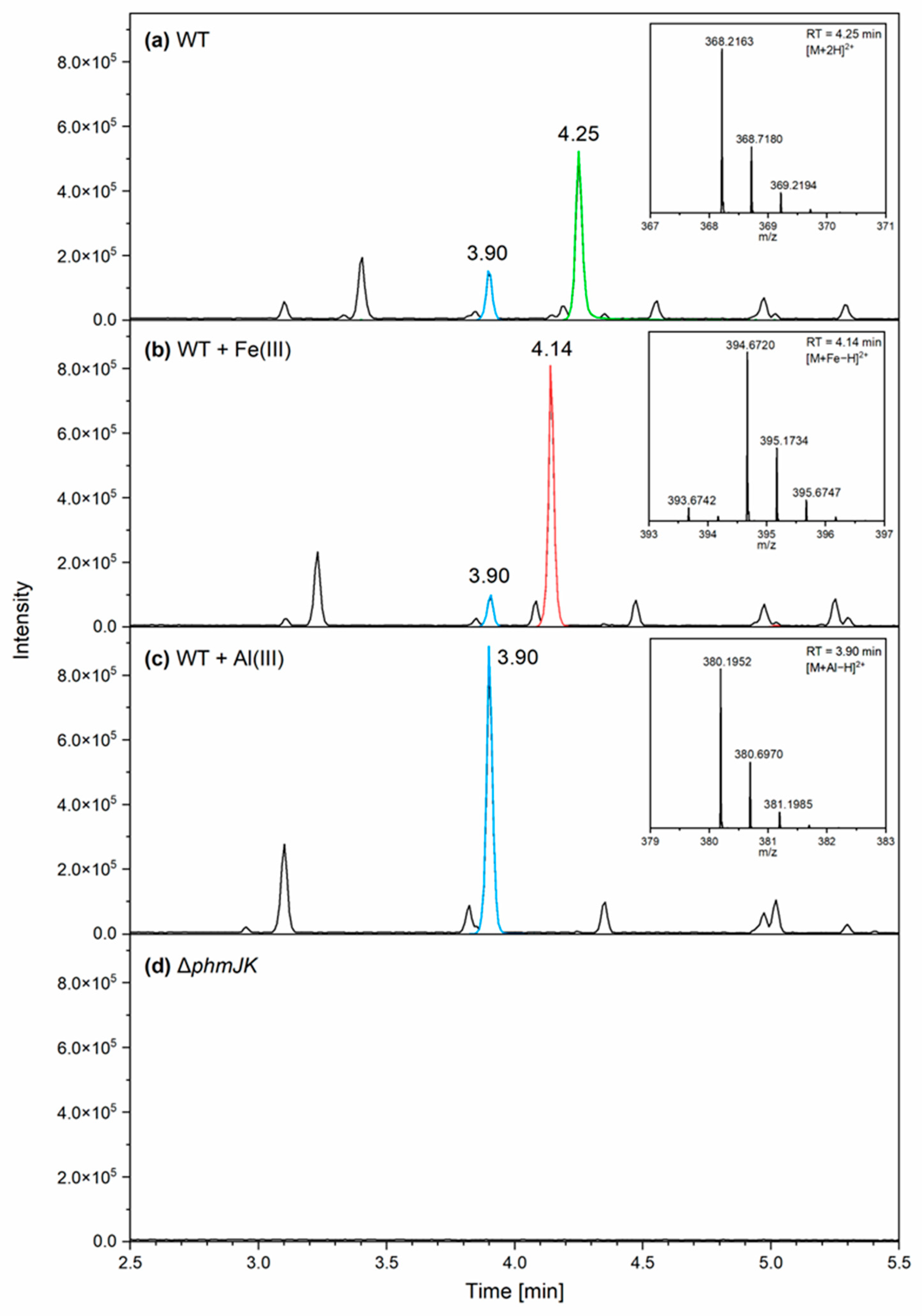

3.2. Phymabactin Chelates Fe(III) and Al(III)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MMS-2 | enhanced Mojave Mars Simulant 2 |

| UHPLC MS | Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| wt% | Percent per weight |

References

- Nguyen, M.; Knowling, M.; Tran, N.N.; Burgess, A.; Fisk, I.; Watt, M.; Escribà-Gelonch, M.; This, H.; Culton, J.; Hessel, V. Space farming: Horticulture systems on spacecraft and outlook to planetary space exploration. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 194, 708–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovane, M.; Izzo, L.G.; Romano, L.E.; Aronne, G. Simulated microgravity affects directional growth of pollen tubes in candidate space crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.M.; Lane, H.W.; Zwart, S.R. Spaceflight Metabolism and Nutritional Support, 413–439. [CrossRef]

- Odeh, R.; Guy, C.L. Gardening for Therapeutic People-Plant Interactions during Long-Duration Space Missions. Open Agriculture 2017, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasseri, A.T.; Rasoul-Ami, S.; Morowvat, M.H.; Ghasemi, Y. Single Cell Protein: Production and Process. American J. of Food Technology 2011, 6, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.P.; Ahmadi, F.; Kariman, K.; Lackner, M. Recent advances and challenges in single cell protein (SCP) technologies for food and feed production. NPJ Sci. Food 2024, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tei, F.; Neve, S. de; Haan, J. de; Kristensen, H.L. Nitrogen management of vegetable crops. Agricultural Water Management 2020, 240, 106316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyetunji, O.; Bolan, N.; Hancock, G. A comprehensive review on enhancing nutrient use efficiency and productivity of broadacre (arable) crops with the combined utilization of compost and fertilizers. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 317, 115395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindström, K.; Mousavi, S.A. Effectiveness of nitrogen fixation in rhizobia. Microb. Biotechnol. 2020, 13, 1314–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson-Boivin, C.; Sachs, J.L. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation by rhizobia-the roots of a success story. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 44, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellés-Sancho, P.; Beukes, C.; James, E.K.; Pessi, G. Nitrogen-Fixing Symbiotic Paraburkholderia Species: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Nitrogen 2023, 4, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, B.; Chu, C. Nitrogen assimilation in plants: current status and future prospects. J. Genet. Genomics 2022, 49, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, L.K.; Volpiano, C.G.; Lisboa, B.B.; Giongo, A.; Beneduzi, A.; Passaglia, L.M.P. Potential of Rhizobia as Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria, 153–174. [CrossRef]

- Bellés-Sancho, P.; Liu, Y.; Heiniger, B.; Salis, E. von; Eberl, L.; Ahrens, C.H.; Zamboni, N.; Bailly, A.; Pessi, G. A novel function of the key nitrogen-fixation activator NifA in beta-rhizobia: Repression of bacterial auxin synthesis during symbiosis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 991548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellés-Sancho, P.; Lardi, M.; Liu, Y.; Hug, S.; Pinto-Carbó, M.A.; Zamboni, N.; Pessi, G. Paraburkholderia phymatum Homocitrate Synthase NifV Plays a Key Role for Nitrogenase Activity during Symbiosis with Papilionoids and in Free-Living Growth Conditions. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, B.J.; Mathesius, U. Phytohormone regulation of legume-rhizobia interactions. J. Chem. Ecol. 2014, 40, 770–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.Z.; Huang, J.; Gyaneshwar, P.; Zhao, D. Rhizobium sp. IRBG74 Alters Arabidopsis Root Development by Affecting Auxin Signaling. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dong, C.; Chu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Liu, H.; Xie, B. Synthesis, characterization and application of ion exchange resin as a slow-release fertilizer for wheat cultivation in space. Acta Astronautica 2016, 127, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, S.; Liu, Y.; Heiniger, B.; Bailly, A.; Ahrens, C.H.; Eberl, L.; Pessi, G. Differential Expression of Paraburkholderia phymatum Type VI Secretion Systems (T6SS) Suggests a Role of T6SS-b in Early Symbiotic Interaction. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 699590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, S.; Heiniger, B.; Bolli, K.; Paszti, S.; Eberl, L.; Ahrens, C.H.; Pessi, G. Paraburkholderia sabiae Uses One Type VI Secretion System (T6SS-1) as a Powerful Weapon against Notorious Plant Pathogens. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0162223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, S.J.; Joshi, S.J. Engineering rhizobial bioinoculants: a strategy to improve iron nutrition. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013, 2013, 315890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Kang, J.P.; Ahn, J.C.; Kim, Y.J.; Piao, C.H.; Yang, D.U.; Yang, D.C. Siderophore-producing rhizobacteria reduce heavy metal-induced oxidative stress in Panax ginseng Meyer. J. Ginseng Res. 2021, 45, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahde, S.; Boughribil, S.; Sijilmassi, B.; Amri, A. Rhizobia: A Promising Source of Plant Growth-Promoting Molecules and Their Non-Legume Interactions: Examining Applications and Mechanisms. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalk, I.J.; Hannauer, M.; Braud, A. New roles for bacterial siderophores in metal transport and tolerance. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 2844–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellés-Sancho, P.; Lardi, M.; Liu, Y.; Eberl, L.; Zamboni, N.; Bailly, A.; Pessi, G. Metabolomics and Dual RNA-Sequencing on Root Nodules Revealed New Cellular Functions Controlled by Paraburkholderia phymatum NifA. Metabolites 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, S.B. de; Lardi, M.; Gandolfi, A.; Eberl, L.; Pessi, G. Mutations in Two Paraburkholderia phymatum Type VI Secretion Systems Cause Reduced Fitness in Interbacterial Competition. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardi, M.; Campos, S.B. de; Purtschert, G.; Eberl, L.; Pessi, G. Competition Experiments for Legume Infection Identify Burkholderia phymatum as a Highly Competitive β-Rhizobium. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardi, M.; Pessi, G. Functional Genomics Approaches to Studying Symbioses between Legumes and Nitrogen-Fixing Rhizobia. High Throughput 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golaz, D.; Papenfuhs, C.K.; Bellés-Sancho, P.; Eberl, L.; Egli, M.; Pessi, G. RNA-seq analysis in simulated microgravity unveils down-regulation of the beta-rhizobial siderophore phymabactin. NPJ Microgravity 2024, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.H.; Abbey, W.; Bearman, G.H.; Mungas, G.S.; Smith, J.A.; Anderson, R.C.; Douglas, S.; Beegle, L.W. Mojave Mars simulant—Characterization of a new geologic Mars analog. Icarus 2008, 197, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B A E Lehner; C N Haenggi; J Schleppi; S J J Brouns; A Cowley. Bacterial modification of lunar and Martian regolith for plant growth in life support systems 2018.

- Yan, L.; Riaz, M.; Li, S.; Cheng, J.; Jiang, C. Harnessing the power of exogenous factors to enhance plant resistance to aluminum toxicity; a critical review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 203, 108064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peys, A.; Isteri, V.; Yliniemi, J.; Yorkshire, A.S.; Lemougna, P.N.; Utton, C.; Provis, J.L.; Snellings, R.; Hanein, T. Sustainable iron-rich cements: Raw material sources and binder types. Cement and Concrete Research 2022, 157, 106834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.J.; Maaløe, O. DNA replication and the division cycle in Escherichia coli. Journal of Molecular Biology 1967, 23, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szybalski, W. Gradient plates for the study of microbial resistance to antibiotics. Bacteriological Proceedings 1952.

- Costa, N.; Bonetto, A.; Ferretti, P.; Casarotto, B.; Massironi, M.; Altieri, F.; Nava, J.; Favero, M. Analytical data on three Martian simulants. Data Brief 2024, 57, 111099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, K.M.; Britt, D.T.; Smith, T.M.; Fritsche, R.F.; Batcheldor, D. Mars global simulant MGS-1: A Rocknest-based open standard for basaltic martian regolith simulants. Icarus 2019, 317, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilles, C.N.; Downs, R.T.; Ming, D.W.; Rampe, E.B.; Morris, R.V.; Treiman, A.H.; Morrison, S.M.; Blake, D.F.; Vaniman, D.T.; Ewing, R.C.; et al. Mineralogy of an active eolian sediment from the Namib dune, Gale crater, Mars. JGR Planets 2017, 122, 2344–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaroshevsky, A.A. Abundances of chemical elements in the Earth’s crust. Geochem. Int. 2006, 44, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoli, K.; Lowe, C.A.; Farmer, K.L.; Husnain, S.I.; Thomas, M.S. The ornibactin biosynthesis and transport genes of Burkholderia cenocepacia are regulated by an extracytoplasmic function sigma factor which is a part of the Fur regulon. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 3631–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, A.; Jenul, C.; Carlier, A.L.; Eberl, L. The role of siderophores in metal homeostasis of members of the genus Burkholderia. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2016, 8, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuvaneshwari, M.; Bairoliya, S.; Parashar, A.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Mukherjee, A. Differential toxicity of Al2O3 particles on Gram-positive and Gram-negative sediment bacterial isolates from freshwater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016, 23, 12095–12106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botté, A.; Zaidi, M.; Guery, J.; Fichet, D.; Leignel, V. Aluminium in aquatic environments: abundance and ecotoxicological impacts. Aquat Ecol 2022, 56, 751–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M.; Munot, H.P.; Shouche, Y.; Meyer, J.M.; Goel, R. Isolation and functional characterization of siderophore-producing lead- and cadmium-resistant Pseudomonas putida KNP9. Curr. Microbiol. 2005, 50, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, M.; Kumar, S.; Makarana, G.; Goel, R. Metal-Tolerant Bioinoculant Pseudomonas putida KNP9 Mediated Enhancement of Soybean Growth under Heavy Metal Stress Suitable for Biofuel Production at the Metal-Contaminated Site. Energies 2023, 16, 4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, M.R.H.; Rahman, M.; Mahmud, N.U.; Adak, M.K.; Islam, T.; Fujita, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Application of Rhizobacteria, Paraburkholderia fungorum and Delftia sp. Confer Cadmium Tolerance in Rapeseed (Brassica campestris) through Modulating Antioxidant Defense and Glyoxalase Systems. Plants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulin, L.; Munive, A.; Dreyfus, B.; Boivin-Masson, C. Nodulation of legumes by members of the beta-subclass of Proteobacteria. Nature 2001, 411, 948–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).