3.1. Verification of the Wynn-Epsilon Method for Solving the FKV Oscillator Equation

To validate the numerical method used to evaluate the series solutions of Eq. (19), we consider the special case . In this case, Eq. (19) reduces to the classical damped harmonic oscillator equation (28), with parameters given by and . Accordingly, we substitute into Eqs. (21), (22), and (24), and compare the results obtained using the Wynn-epsilon method with the known analytical functions and appearing in Eq. (29). This comparison allows us to verify the correctness and numerical accuracy of the proposed approach.

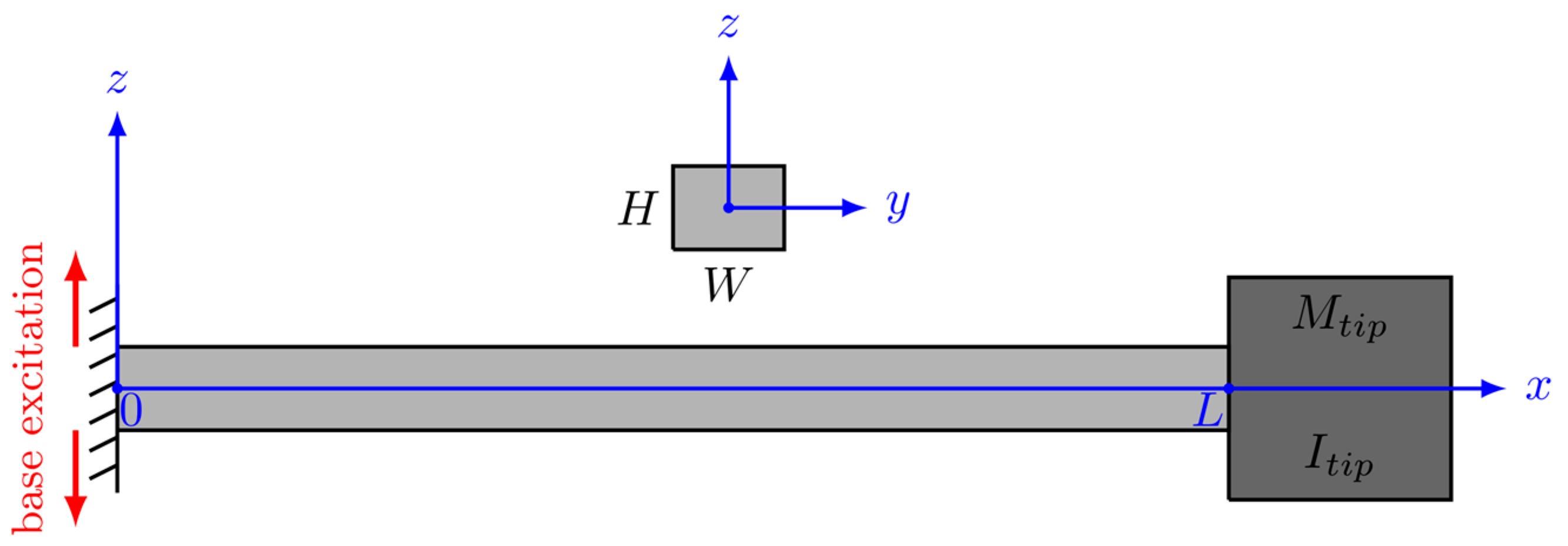

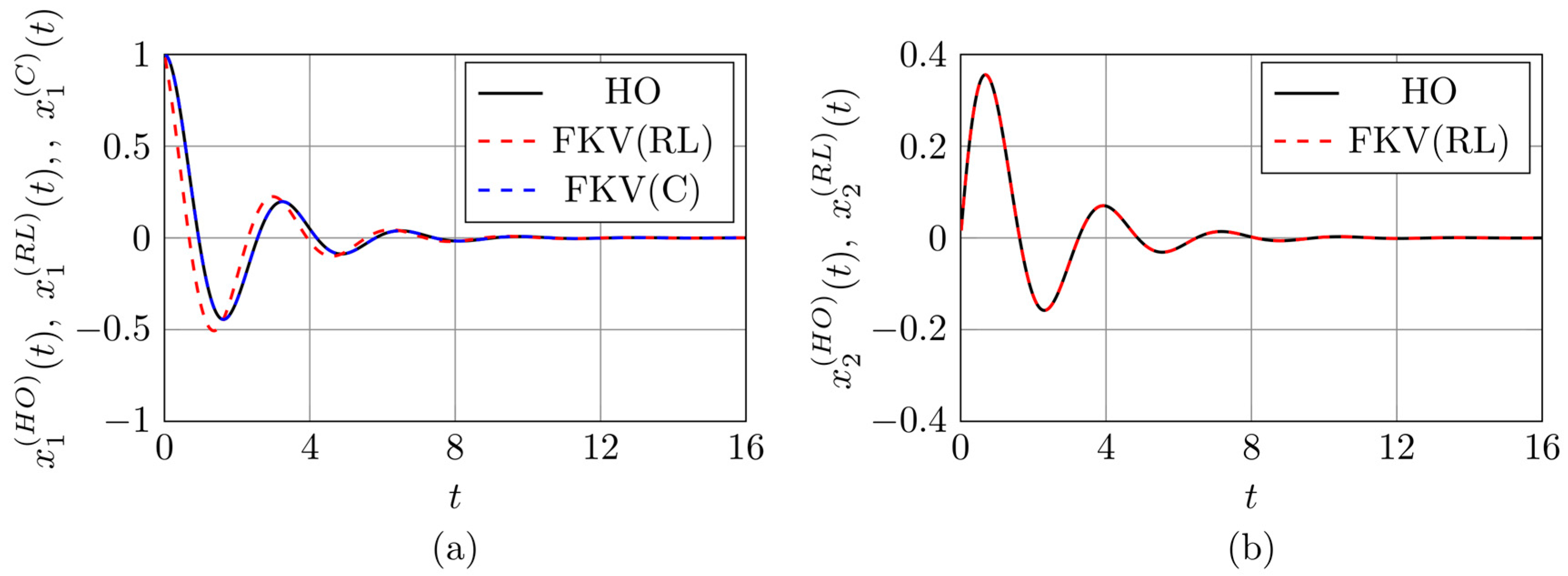

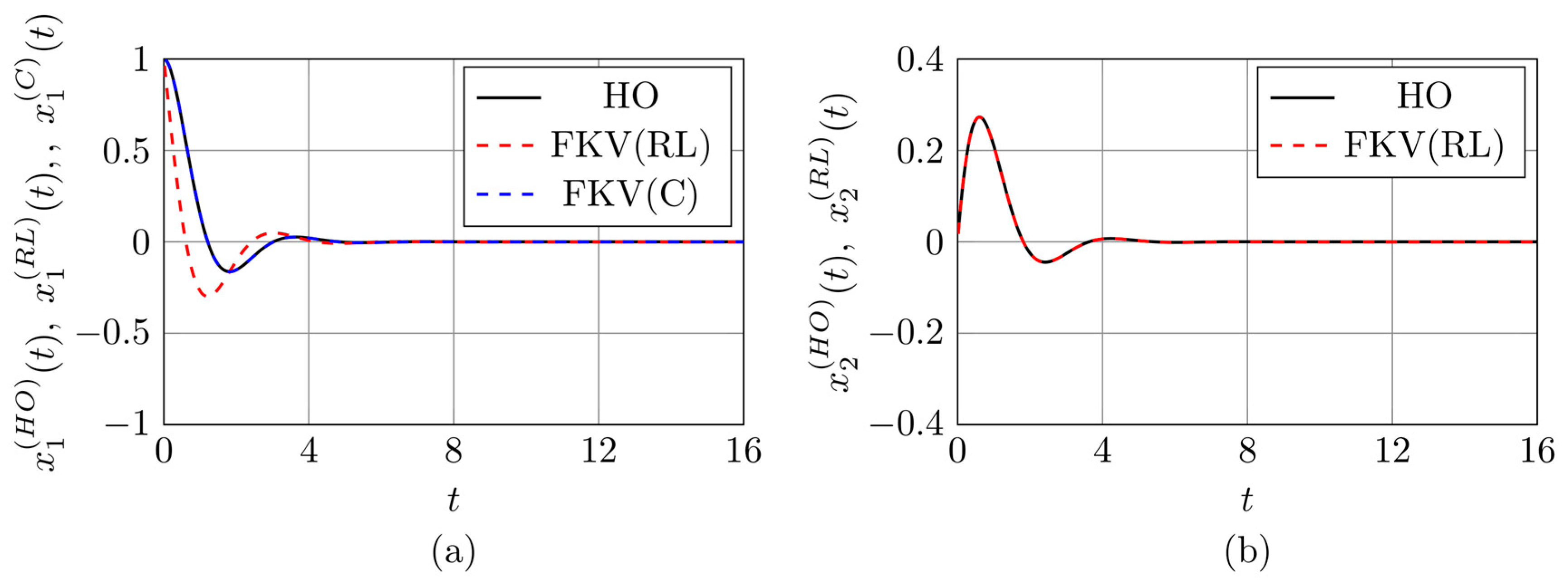

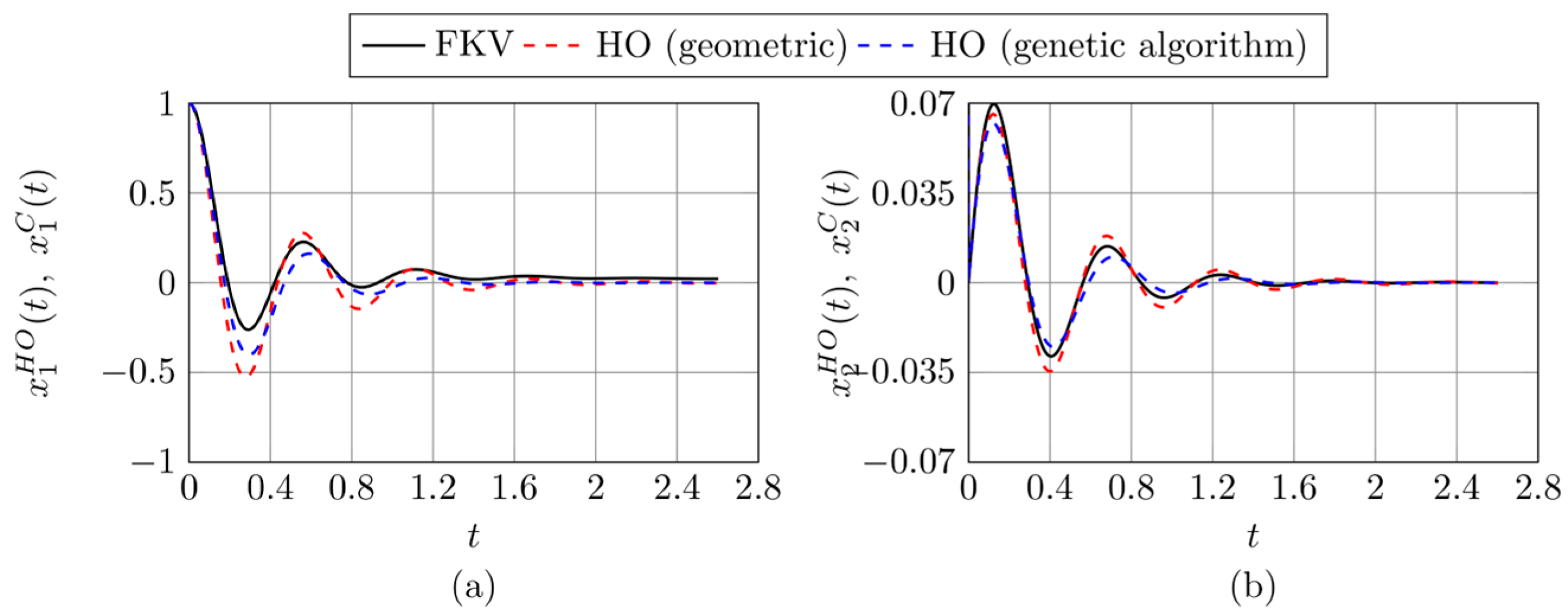

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 present a comparison between the analytical solution components of the classical harmonic oscillator,

and

(solid black lines), and the corresponding approximations obtained using the Wynn-epsilon method for the fractional model with Riemann–Liouville (red dashed lines) and Caputo (blue dashed lines) derivatives.

Subfigures labeled (a) show the components associated with the initial displacement condition , while subfigures labeled (b) correspond to the initial velocity condition . It should be noted that in the subfigures (b), only two curves are plotted, since the solution components related to the initial velocity are identical for both the Riemann–Liouville and Caputo cases.

A very good agreement can be observed between the Wynn-

approximation of the

and the function

in

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4(a), with the maximum relative absolute difference being on the order of

. A similar observation holds for the Wynn-

approximation

and the function

shown in

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4(b).

In contrast, noticeable discrepancies occur between

(red dashed lines in

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4(a)) and

, with maximum relative differences reaching approximately 0.36 in Figure 2(a), 0.55 in Figure 3(a), and 0.09 in Figure 4(a). These deviations are related to the incompatibility of initial conditions in the Riemann–Liouville formulation. However, it can be shown that the difference

tends to zero as

, indicating that the solutions converge asymptotically.

To validate the numerical solutions of the nonhomogeneous fractional Kelvin–Voigt oscillator equation with zero initial conditions, we once again consider the limiting case

. In this case, the equation reduces to the classical nonhomogeneous damped harmonic oscillator:

where

,

, and the forcing function

is defined in Eq. (18). We denote the solution of Eq. (33) under zero initial conditions by

. This solution serves as a reference for assessing the accuracy of the numerical results obtained for the fractional model with

.

Let denote the solution of Eq. (1) with zero initial conditions for . In this case, the homogeneous component vanishes, and the solution is given by the convolution integral appearing in Eq. (25).

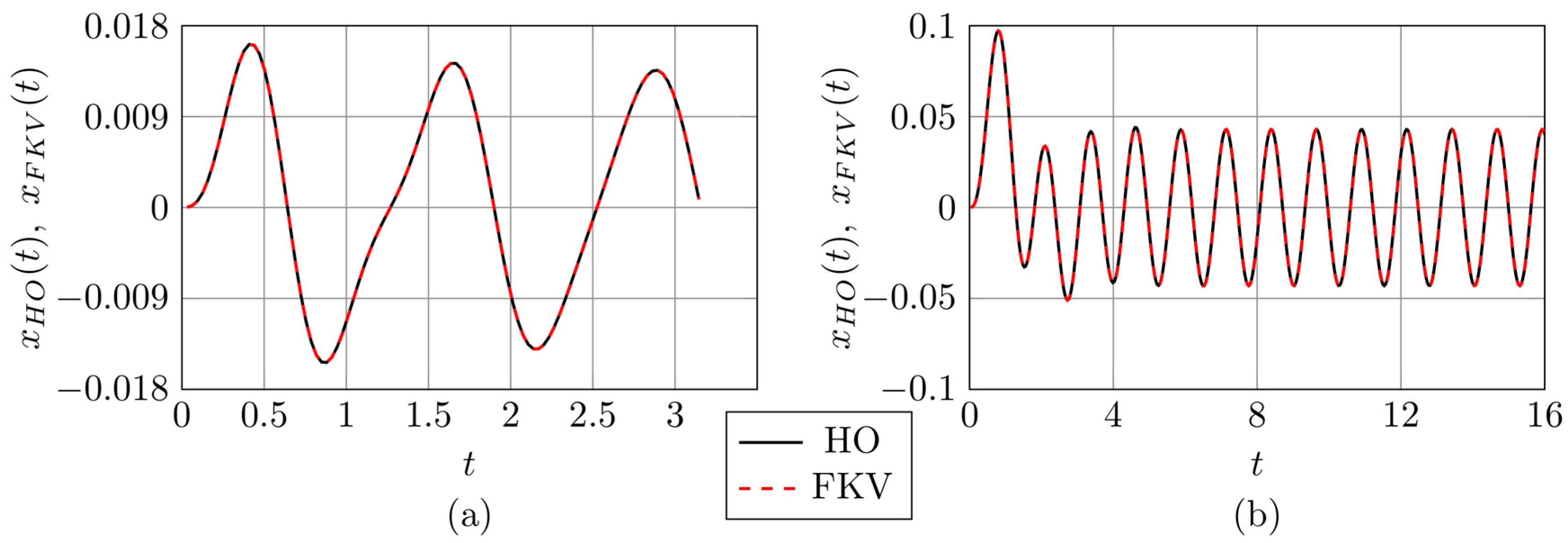

To illustrate the accuracy of the proposed numerical approach, Figure 5 presents a comparison between the exact solution of the classical oscillator equation (33) and the approximation obtained using the Wynn-epsilon method. The comparison is carried out for two selected fractional Kelvin–Voigt oscillators subjected to the external excitation defined in Eq. (18), with parameters fixed as and .

The agreement between the exact solution and the Wynn-epsilon approximation is very good. The maximum relative difference between the two curves is on the order of .

3.2. Identification of Equivalent Harmonic Oscillator Parameters: Geometric and Optimization Approaches

In this section, we compare two methods for identifying the parameters of a classical harmonic oscillator that best approximates the response of a given fractional Kelvin–Voigt (FKV) oscillator. For each method, denoted by the superscript , we define the identified optimal parameters of the equivalent harmonic oscillator as and , corresponding to the undamped natural frequency and the damping ratio, respectively.

The resulting optimal approximation is denoted by , and its accuracy is evaluated using formula , where denotes the divergence coefficient defined in Eq. (32), which quantifies the discrepancy between the fractional and harmonic oscillator responses.

Table 1 presents a comparison of parameter identification results for several fractional Kelvin–Voigt (FKV) with parameters shown in the first column. For each case, the identified parameters of the equivalent harmonic oscillator obtained using the geometric method (second column) and the genetic algorithm (third column) are listed, along with the corresponding values of the divergence coefficient , which quantifies the discrepancy between the fractional and classical models.

Analysis of the results reveals that the genetic algorithm generally yields lower values of the divergence coefficient

, indicating better agreement between the models. However, this is not always the case, as illustrated by rows 1 and 7 of

Table 1, where the geometric method performs slightly better. In certain cases (rows 7 and 10), the divergence coefficient reaches relatively high values, suggesting that the classical harmonic model may not always provide a satisfactory approximation of the fractional dynamics.

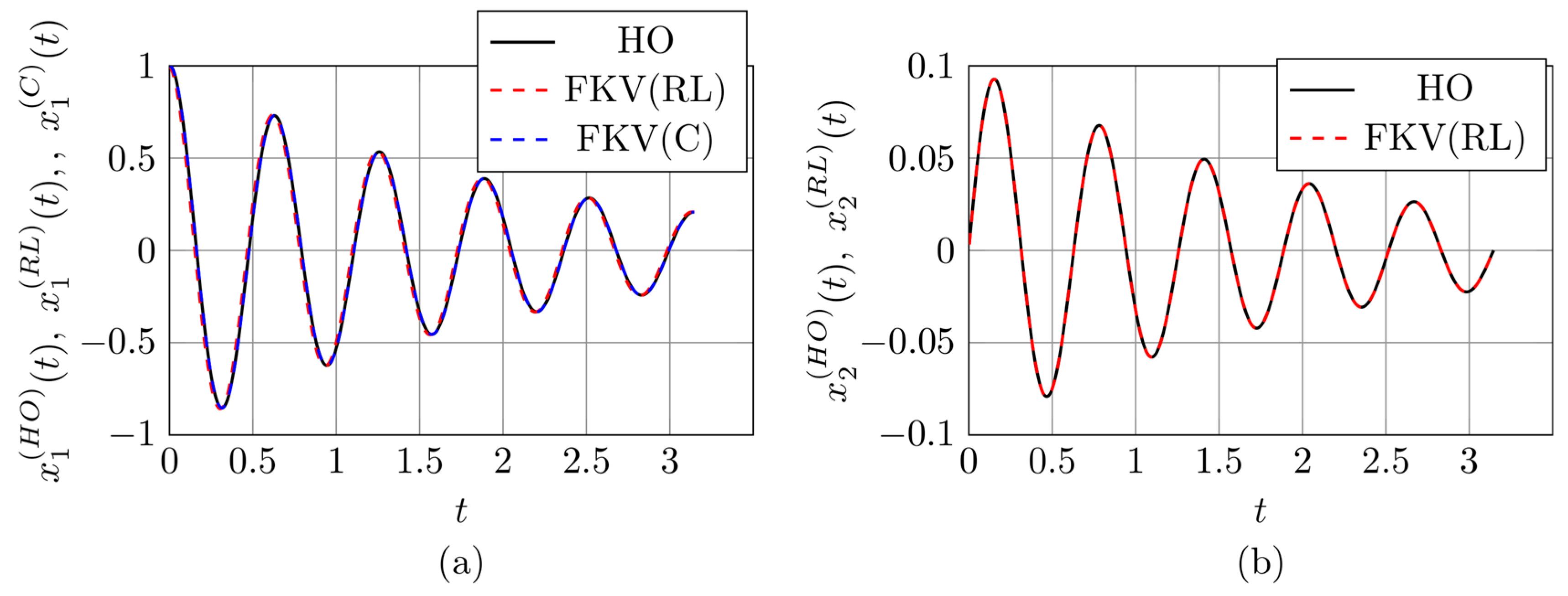

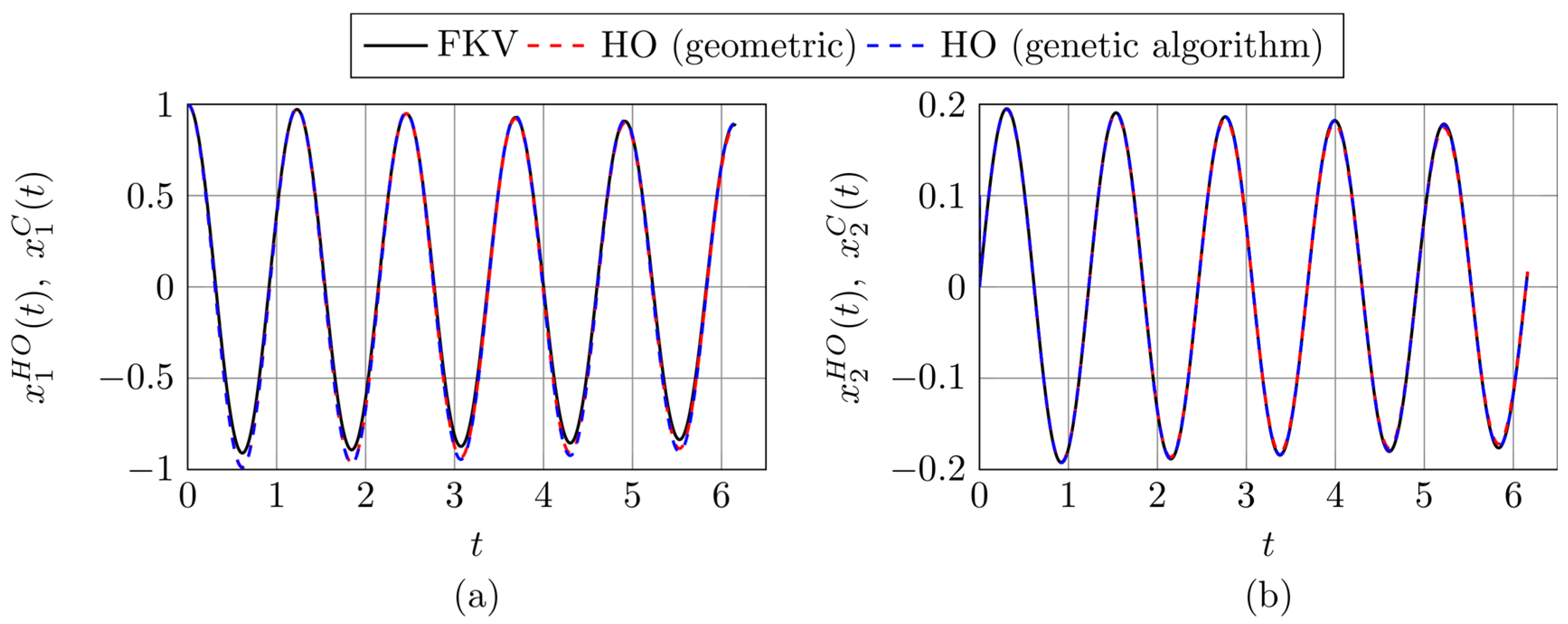

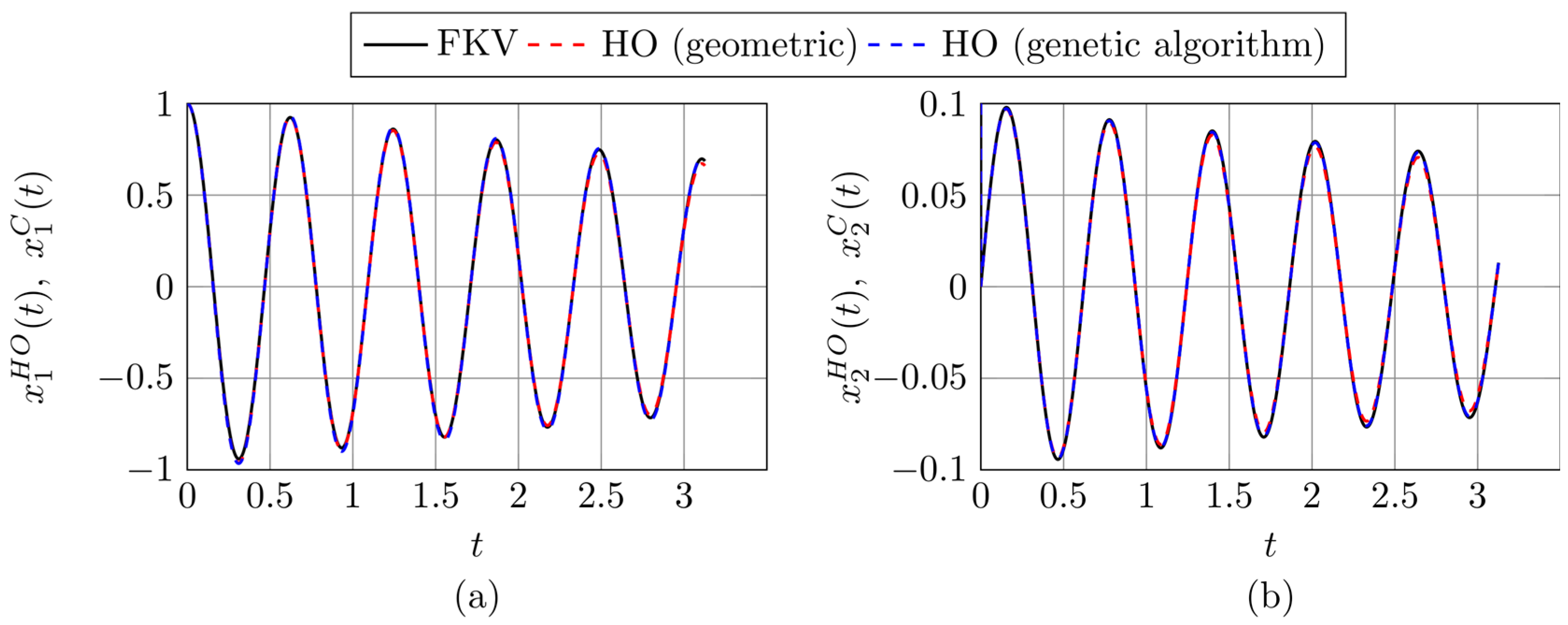

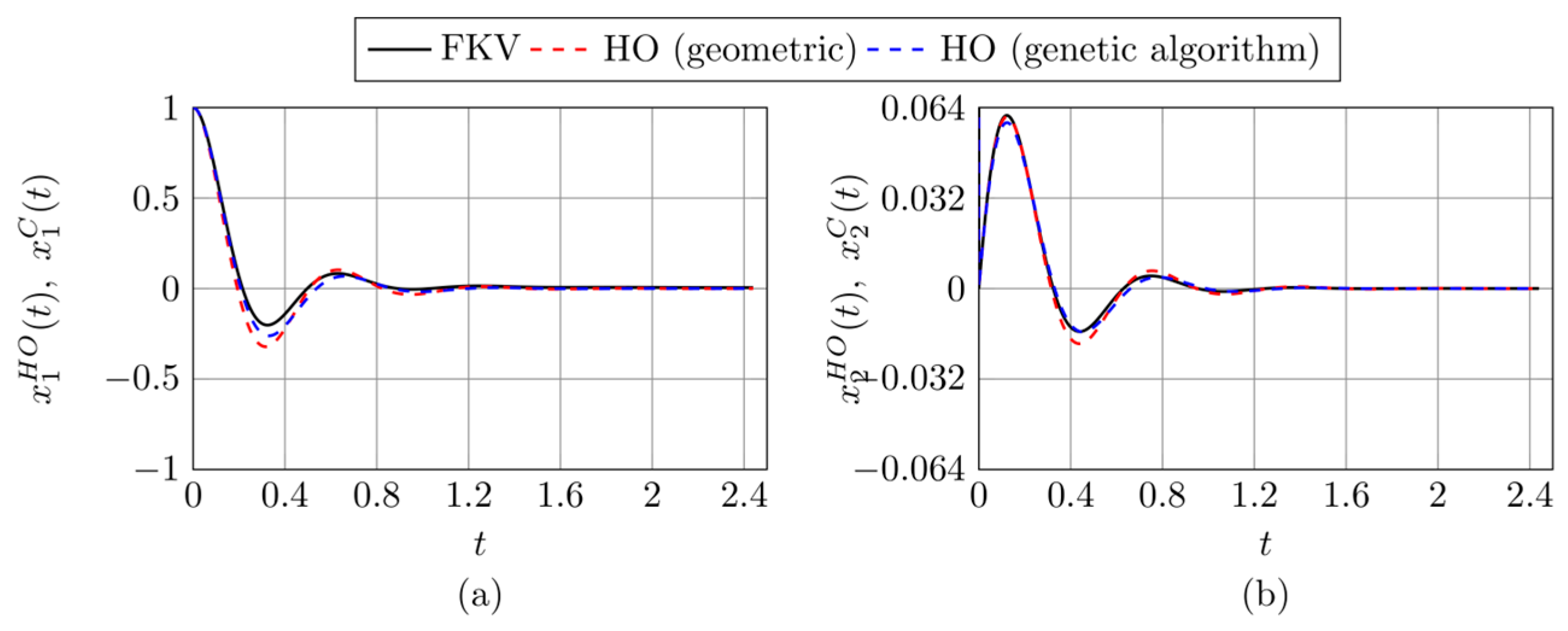

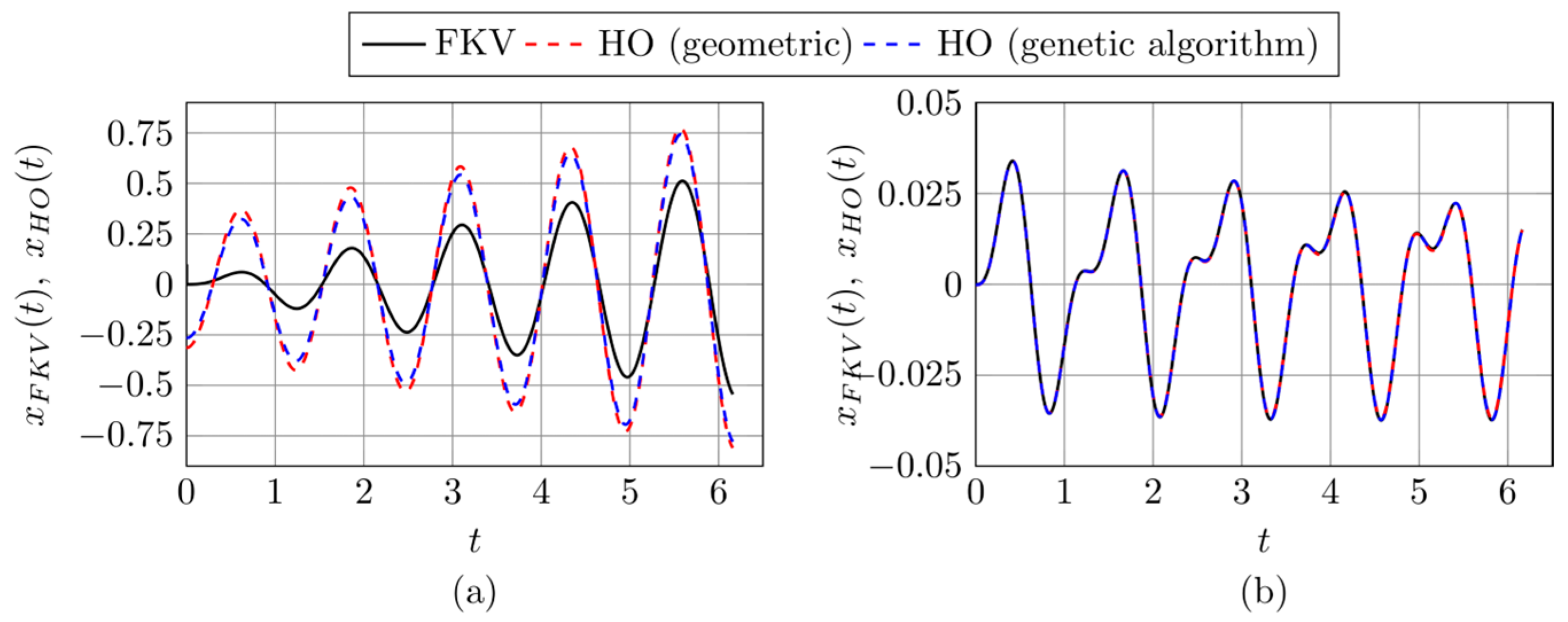

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 6–9 present a comparison between the solution components of selected FKV oscillators and those of classical harmonic oscillators identified using two different methods: a geometric approach and a genetic algorithm. Each figure is composed of two parts (a) and (b). Figures (a) show comparison of the displacement-related components

and

, while figures (b) comparison of the velocity-related components

and

. Here,

and

correspond to components of the harmonic oscillator solution

computed using the optimal parameters obtained via the respective identification method.

The results illustrated in

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 provide additional insight into the effectiveness of both identification methods in approximating the behavior of various FKV oscillators. The observations are consistent with the divergence values

reported in Table 1.

In

Figure 6, corresponding to parameters

, both methods yield harmonic oscillators with relatively high divergence values (around 0.08), despite the overall good visual agreement of the solution components. Deviations are mainly noticeable near the extrema of the curves, as seen in part (a) of the figure.

Figure 7 shows results for

, where the divergence coefficients are somewhat different—0.037 for the geometric method and 0.026 for the genetic algorithm—yet in both cases the visual agreement between the fractional and classical components is excellent.

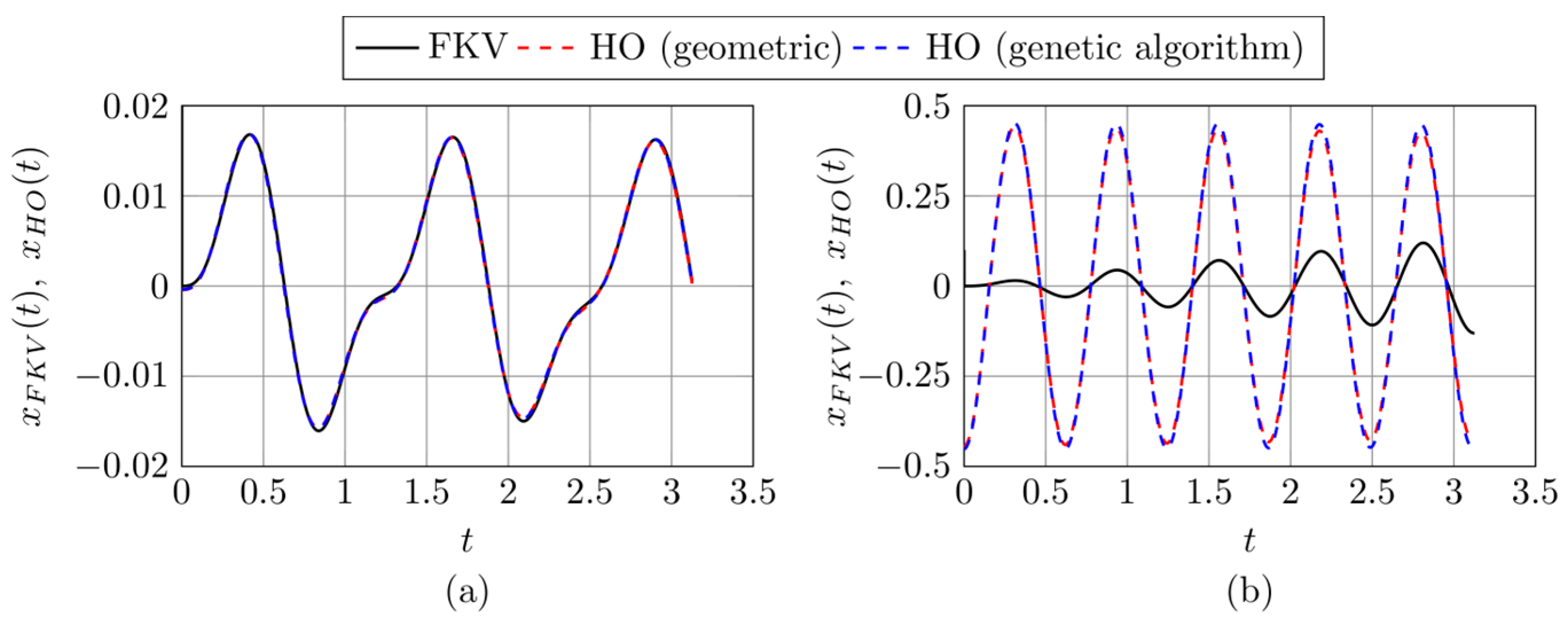

In

Figure 8, with parameters

, a more pronounced discrepancy is observed: the geometric approach produces a relatively large value of the

, while the genetic algorithm yields a smaller value. This case corresponds to a system with strong damping, which may contribute to the increased difficulty in achieving an accurate harmonic approximation.

Finally,

Figure 9, representing

, shows that neither method succeeds in producing a good match. The divergence coefficient exceeds 0.1 in both cases, reaching as high as 0.25 for the geometric approach. This poor agreement, clearly visible in both components, suggests that for this configuration, a classical harmonic oscillator may not adequately capture the dynamics of the fractional system.

3.3. Testing Harmonic Models in the Nonhomogeneous Case

In this subsection, we investigate the performance of the identified harmonic oscillator models in the context of the nonhomogeneous fractional Kelvin–Voigt equation (Eq. (1)) with zero initial conditions. The solution of this equation, given by Eq. (25), reduces to a convolution integral, as the homogeneous part vanishes. For comparison, we consider the classical damped harmonic oscillator (Eq. (33)) with zero initial conditions and identical sinusoidal forcing, whose solution can be expressed in closed form using elementary functions such as sine, cosine, and exponential terms.

The harmonic oscillator parameters used in this comparison were obtained using the identification methods described in the previous subsection, for fixed values of the FKV model parameters . Two representative FKV oscillators were selected for this analysis: and . The corresponding harmonic oscillator parameters are listed in Table 1 (rows 1 and 5, respectively).

To quantitatively assess the agreement between the solutions of the fractional model

and the classical harmonic oscillator

, we use a modified version of the divergence coefficient (32) introduced earlier:

Specifically, when the indicator defined in Eq. (34) is evaluated using the solution obtained with parameters identified in the previous subsection (using either the geometric method or the genetic algorithm), we denote its value by .

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 present a comparison between the time-domain responses of the fractional oscillator

and the corresponding harmonic oscillator approximations

, obtained using the geometric method (red dashed lines) and the genetic algorithm (blue dashed lines). The fractional response is plotted in black as a reference.

For each selected FKV oscillator, two scenarios are considered: one in which the forcing frequency is far from the resonance frequency of the harmonic model, and another in which is chosen to match the resonance frequency of the harmonic model (we set ). This setup allows us to examine how the accuracy of the harmonic approximation depends on the proximity to resonance.

The results shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 highlight the influence of the forcing frequency on the accuracy of harmonic oscillator approximations in the nonhomogeneous case. Each figure compares the solution of the FKV equation with those of two harmonic oscillators identified using the geometric method and the genetic algorithm, respectively.

For the FKV oscillator with parameters , subfigure 10(a) illustrates the resonance case with , where substantial discrepancies are observed: the divergence coefficients reach for the geometric method and for the genetic algorithm. In contrast, subfigure 10(b), corresponding to the off-resonance case with , shows very good agreement, with dropping to and , respectively.

A similar trend is visible for the oscillator defined by . In this case, the off-resonance response (subfigure 11(a)), yields relatively low divergence values: for the geometric method and for the genetic algorithm. However, the resonance case shown in subfigure 11(b), with , leads to a complete breakdown of the harmonic approximation, with divergence values near to 1 for both methods.

These results demonstrate that while harmonic oscillator models can accurately reproduce the fractional response under off-resonance excitation, they may fail dramatically near resonance. This is due to the high sensitivity of the system’s steady-state behavior in the resonant regime, where subtle differences in the underlying dynamics—especially those introduced by the fractional-order operator—are strongly amplified and no longer well captured by classical models.

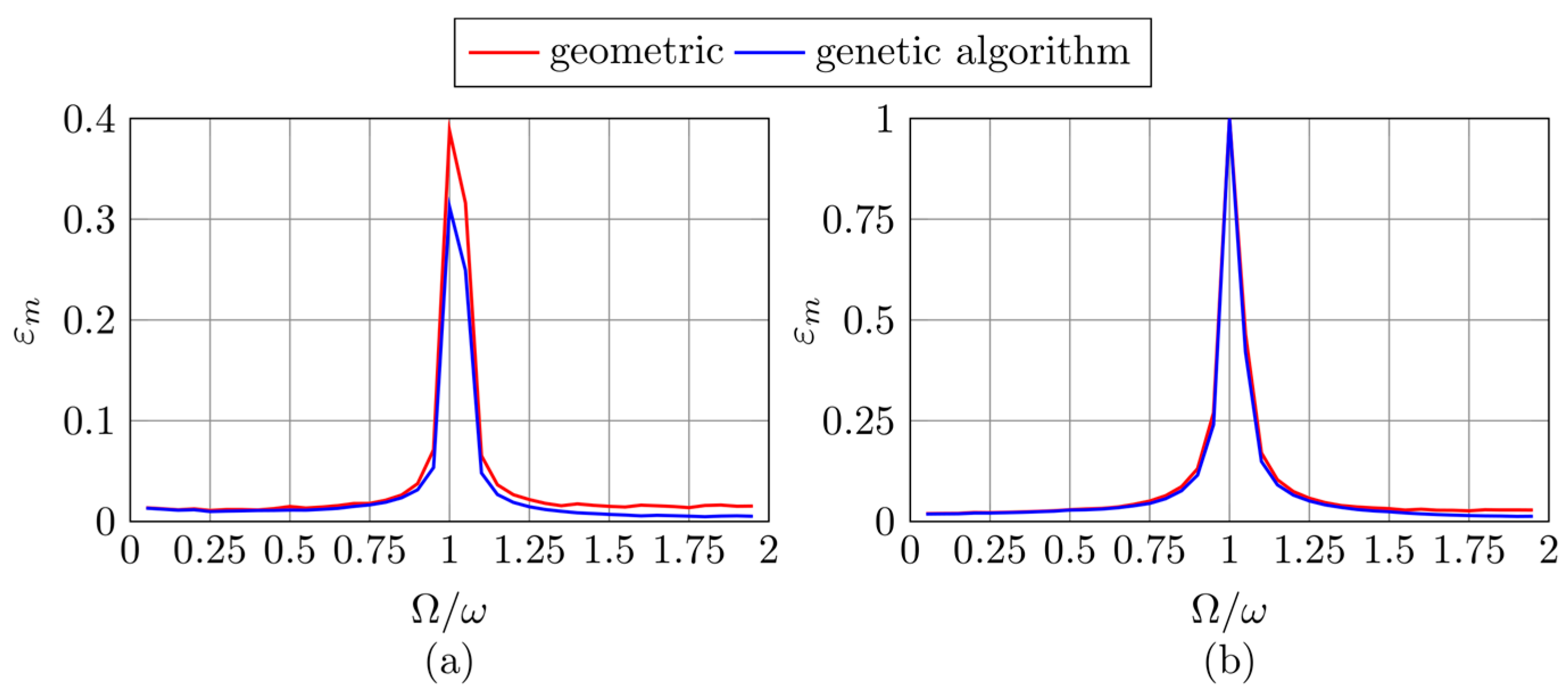

To further investigate the sensitivity of the harmonic approximation with respect to the forcing frequency, we compute the divergence coefficient for a range of excitation frequencies. Specifically, we vary the ratio from to in steps of , while keeping the parameters of the FKV oscillator fixed. This analysis is performed for both identification methods and for the two representative FKV oscillators considered earlier.

The plots in

Figure 12 reveal that the divergence coefficient

reaches a sharp peak in the vicinity of

, confirming that the accuracy of the harmonic approximation deteriorates significantly near resonance.

For the first FKV oscillator (

Figure 12(a)), the peak is less pronounced and slightly shifted away from

. This shift reflects the fact that the actual resonance frequency of the corresponding harmonic oscillator does not exactly match the parameter

of the FKV model.

In contrast, for the second oscillator (

Figure 12(b)), the resonance frequency of the harmonic model is close to

, resulting in a stronger and more centered peak. These observations highlight the limitations of harmonic approximations in capturing resonant behavior in fractional-order systems.