Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Objectives

- To analyse the current state of female representation in STEM fields in South Africa.

- To identify the key barriers hindering female participation in STEM.

- To recommend strategies for fostering gender inclusivity and diversity in STEM.

1.2. Problem Statement and Significance of the Study

2. Literature Review

2.1. Socio-Cultural Norms

2.2. The Men's Club Culture in STEM

2.3. Educational Challenges

2.4. Limited Participation

2.5. Workplace Inequalities

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Extraction

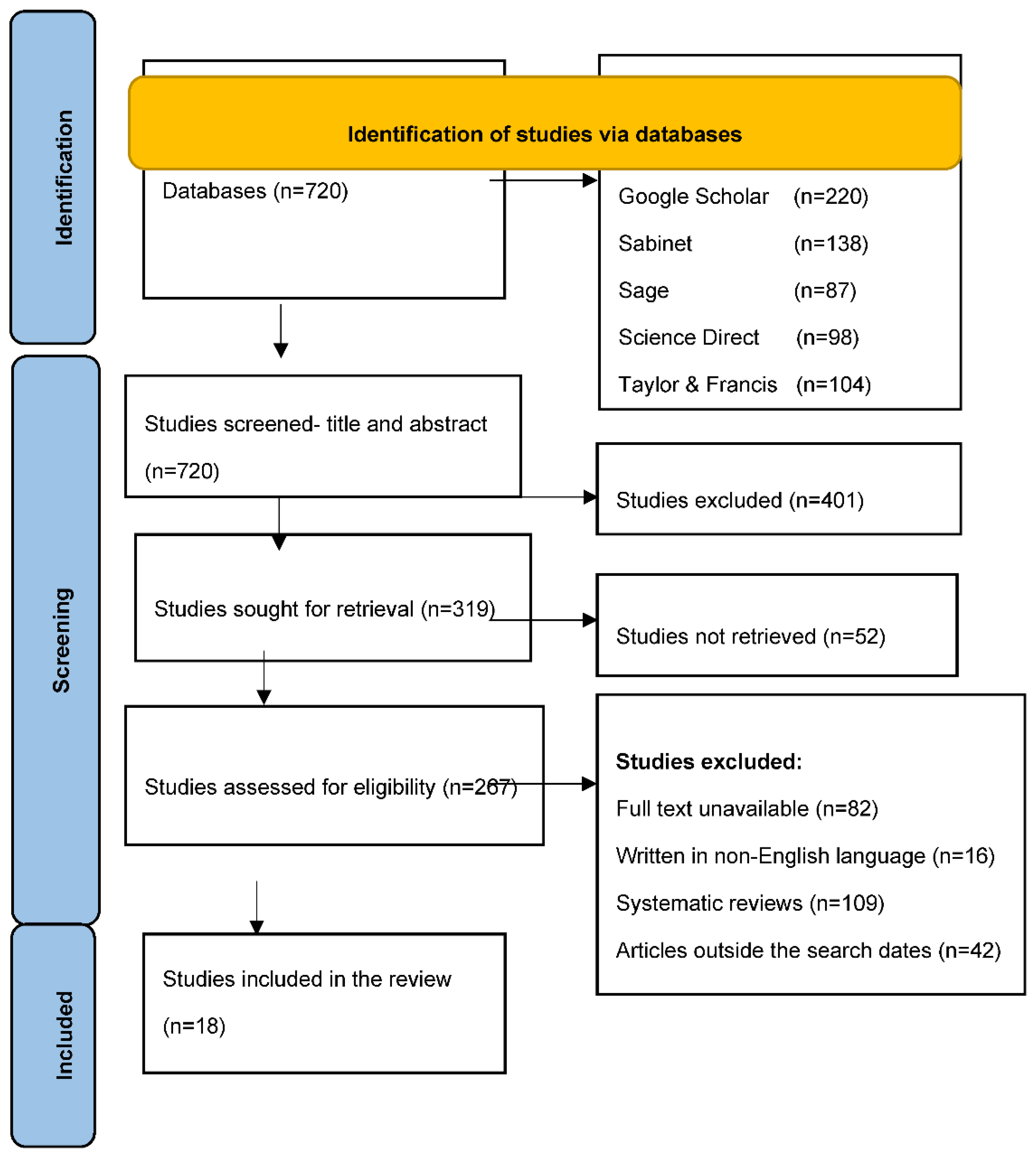

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Studies on gender equity in STEM education and careers | Studies focusing exclusively on non-STEM disciplines. |

| Publications from 2010 to 2025 | Studies published in a language other than English |

| Journal articles, books, and grey literature | Systematic reviews and meta-analysis |

3.3. Screening Process

3.4. Data Analysis

| Title | Authors | Year | Objective | Methods | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patterns of Persistence Among Engineering Students | Bengesai & Pocock | 2021 | To examine patterns of persistence in engineering education in South Africa | Quantitative: Descriptive statistics and decision tree analysis | Persistence rates were shaped by gender, race, financial aid, and admission points |

| Curriculum Bridging the Gap between Secondary and Higher STEM Education – The Case of STEM school | De Meester et al. | 2020 | To examine ways to close the gap between secondary and higher STEM education to ensure an adequate number of well-prepared and qualified students enrolling in STEM programs at the tertiary level | Quantitative: Quasi-experimental | The study found that integrating STEM subjects authentically, as seen in real-world challenges, enhances understanding and fosters creativity, inquiry, and collaboration among students and teachers. |

| Gender Bias Produces Gender Gaps in STEM Engagement | Moss-Racusin et al. | 2018 | To explore the impact of gender bias on STEM engagement | Experimental: Simulated scenarios | Gender bias diminishes women's sense of belonging and lowers their aspirations in STEM fields. |

| Analysis of barriers supports and the gender gap in the choice of STEM studies in secondary education | Merayo & Ayuso | 2022 | To analyse gender disparities in STEM education, | Quantitative: Chi-square and Lambda tests | Boys receive more encouragement toward STEM careers, while girls lean toward health and education fields. The lack of visibility of female scientists reinforces the perception of physics as a male-dominated field. |

| Challenging gender stereotypes: Young women's views on female role models in secondary school science textbooks | Lindner & Makarova | 2024 | To investigate the effects of gender disparity in physics teaching materials on female students aged 15 to 18 and to assess the significance they attribute to female role models in their learning experience. | Qualitative: Interviews | The lack of awareness of female scientists among female students reinforces the perception of physics as a male-dominated field. |

| STEM education and the gender gap: Strategies for encouraging girls to pursue stem careers | Warsito, et al |

2023 | To investigate the reasons women often steer away from STEM careers and to identify effective strategies for increasing their participation and engagement in STEM fields. | Qualitative: Interviews | The study highlights key factors for increasing women's participation in STEM: (1) early exposure, (2) positive role models, (3) an inclusive and supportive learning environment, and (4) active efforts to eliminate gender bias and stereotypes. |

| Gender gap in STEM education and career choices: what matters? | Tandrayen-Ragoobur & Gokulsing | 2022 | To explore how a combination of personal, environmental, and behavioural factors may impact engagement and participation in STEM education and careers. | Mixed methods | The results indicate a gender disparity in STEM degree choices, with female students being less likely to enroll in STEM programs compared to their male counterparts. |

| Overcoming the STEM Gender Gap: from School to Work | Cavaletto & Berra | 2020 | To establish best practices aimed at closing the gender gap in STEM, both in education and the workforce, ensuring greater inclusion and representation for women in these fields. | Mixed methods | The study highlights a gap between perception and reality, showing that the imagined labor market differs significantly from actual workforce conditions. |

| Challenging Media Stereotypes of STEM: Examining an Intervention to Change Adolescent Girls' Gender Stereotypes of STEM Professionals | Steinke & Duncan | 2023 | To evaluate the effectiveness of a media-based intervention in reducing gender-STEM stereotypes among adolescent girls and enhancing their awareness of STEM career opportunities. | Mixed methods | Quantitative and qualitative data confirm positive shifts in adolescent girls' perceptions of women in STEM professions. |

| Black African Women in Engineering Higher Education in South Africa Contending with History, Race, and Gender | Mlambo | 2021 | To investigate how race and gender, shaped by historical and national contexts, impact the career decisions of Black women engineers in South Africa, leading them to pursue industry roles over academic careers. | Qualitative: Interviews | Black African women remain underrepresented in South African engineering academia, where faculty remains predominantly white and male despite efforts to increase Black student access. |

| "A Bridge Between High School and College": A Case Study of a STEM Intervention Program Enhancing College Readiness Among Underserved Students | Lane, Morgan, & Lopez | 2017 | To assess the impact of a STEM intervention program in helping underserved students overcome academic challenges and gain context-specific knowledge necessary for success in STEM fields | Qualitative: Case study | Findings identified nine key practices that enhanced students' readiness for the STEM curriculum and college expectations |

| Increasing Student Engagement, Fraction Knowledge, and STEM Interest Through Game-Based Intervention |

Hunt, Taub, Marino, Holman, & Womack-Adams |

2025 | To assess the impact of a game-based supplemental fraction curriculum on student engagement, fraction comprehension, and STEM interest in inclusive elementary mathematics classrooms. | Quantitative: Experimental pretest-post-test | These findings underscore the potential of game-based learning in mathematics education for foundational STEM concepts, advocating for further research on scalability and broader application |

| Girls in STEM: Is It a Female Role-Model Thing? |

González-Pérez, de Cabo & Sáinz | 2020 | To examine the impact of female role models on girls' interest and preferences for STEM education and careers. | Quantitative: Experimental pretest-post-test | The role-model intervention positively impacts math enjoyment, perceived importance, success expectations, and girls' STEM aspirations while reducing gender stereotypes. |

| The Impact of Female Role Models Leading a Group Mentoring Program to Promote STEM Vocations among Young Girls |

Guenaga, Eguíluz, Garaizar & Mimenza | 2022 | To evaluate the impact of a group mentoring initiative led by a female STEM role model on participants' perceptions and experiences, while examining gender-based differences in its effects. | Quantitative: Experimental pretest-post-test | The program influenced students' attitudes toward technology, expanded their awareness of female STEM figures, and improved their perceptions of science and technology careers. The impact was stronger among girls, though they still showed lower enthusiasm for technology compared to boys. |

| The impact of longitudinal stem careers introducing Intervention on students' career aspirations and on Relating occupational images |

Kotkas & Rannikmäe | 2019 | To investigate the impact of a two-year STEM-career intervention on middle school students and their perceptions of the competence needed for their desired careers. | Quantitative: longitudinal pre- & post-test experimental-control group design |

The study found that integrating career education into science teaching positively supports students' aspirations in STEM fields. |

| Enhancing 21st-Century Skills, STEM Attitudes, and Career Interests Through STEM-Based Teaching: A Primary School Intervention Study | Çalişkan & Pehlivan | 2024 | To examine how STEM-based teaching influences students' 21st-century skills, attitudes toward STEM, and their interest in pursuing careers in STEM fields. | Quantitative: Experimental pretest-post-test | Posttest results showed improvement in students' 21st-century skills, STEM attitudes, and career interest, with the highest gains in career awareness over other skills like critical thinking, innovation, and leadership. |

| Gender gap in STEM education and career choices: what matters? | Tandrayen-Ragoobur, & Gokulsing | 2021 | To assess the gender gap in STEM tertiary education and career | Mixed methods approach | The study found that parental and teacher support significantly increases young women's likelihood of enrolling in STEM higher education compared to males. |

| Exploring the Challenges of Teaching and Learning of Scarce Skill Subjects in Selected South African High Schools | Dlamini et al | 2021 | To explore the perspectives of teachers on learners' performance in scarce skill subjects. | Qualitative: Semi-structured interviews | Overcrowded classrooms, inadequate infrastructure, and insufficient teacher appointments contributed to poor academic performance in scarce skill subjects. |

4. Discussion

4.1. Promoting Role Models

4.2. Mentorship Programmes

4.3. Initiatives to Improve STEM Education at High School Level

4.4. Professional Development of Educators

4.5. Practical and Experiential Learning

5. Parental Involvement

6. Conclusion

7. Recommendations

- To strengthen STEM education and early exposure, ECSA must advocate for STEM curriculum enhancements in collaboration with the Department of Basic Education and engineering companies.

- To promote the visibility of successful women in STEM, ECSA must establish a mentorship framework to support young engineering females.

- To promote diversity in hiring and career advancement, ECSA must encourage industry compliance with gender equity in engineering firms through policy recommendations and professional standards.

- To address socio-cultural barriers, ECSA must collaborate with government and civil society to promote gender-inclusive STEM education and professional practice policies.

- To improve access to STEM technology for hands-on learning, ECSA must work with engineering firms and universities to develop internship and experiential learning programs for aspiring female engineers.

- To increase scholarships and financial support for women pursuing STEM degrees, ECSA must lead policy advocacy efforts to influence national strategies on STEM gender equity and monitor industry compliance.

References

- Ahn, J.N., M. Luna-Lucero, and M. Lamnina. (2016) Motivating Students' STEM Learning Using Biographical Information. International Journal of Designs for Learning, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Ayar, M. C. (2015). First-hand Experience with Engineering Design and Career Interest in Engineering: An Informal STEM Education Case Study. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 15(6), 1655-1675.

- Banchefsky, S., & Park, B. (2018). Negative gender ideologies and gender-science stereotypes are more pervasive in male-dominated academic disciplines. Social Sciences, 7(2), 27. [CrossRef]

- Bengesai, A. V., & Pocock, J. (2021). Patterns of persistence among engineering students at a South African university: A decision tree analysis. South African Journal of Science, 117(3-4), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Burke, & Simmons, 2020; Dengate, Peter, Farenhorst, & Franz-Odendaal, 2019; Robinson, McGee, Bentley, Houston & Botchway, 2016).

- Burke, P. R., & Simmons, K. (2020). Beating the odds: Winning strategies of women in STEM. Center for Creative Leadership.

- Çalışkan, C., & Şenler, B. (2024). Enhancing 21st-Century Skills, STEM Attitudes, and Career Interests Through STEM-Based Teaching: A Primary School Intervention Study. International Primary Education Research Journal, 8(2), 221-232.

- Cavaletto, G. M., & Berra, M. (2020). Overcoming the stem gender gap: From school to work. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 12(Italian Journal of Sociology of Education 12/2), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, K. (2024). A Review on Gender Stereotypes and Career Preferences Among Students. Library of Progress-Library Science, Information Technology & Computer, 44(1).

- Dasgupta, N., & Stout, J. G. (2014). Girls and women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics: STEMing the tide and broadening participation in STEM careers. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(1), 21-29.

- Department of Science and Innovation. (2024). Department of Science and Innovation honours the best and brightest in science at the 2024 South African Women in Science Awards. Accessed from: https://www.dsti.gov.za/index.php/media-room/latest-news/4351-department-of-science-and-innovation-honours-the-best-and-brightest-in-science-at-the-2024-south-african-women-in-science-awards#:~:text=The%20Department%20of%20Science%20and,(STEMI)%20in%20South%20Africa. Date Accessed: 2 February 2025.

- De Meester, J., Boeve-de Pauw, J., Buyse, M. P., Ceuppens, S., De Cock, M., De Loof, H.,... & Dehaene, W. (2020). Bridging the Gap between Secondary and Higher STEM Education–the Case of STEM@ school. European Review, 28(S1), S135-S157. [CrossRef]

- Dengate, J., Peter, T., Farenhorst, A., & Franz-Odendaal, T. (2019). Selective incivility, harassment, and discrimination in Canadian sciences & engineering: A sociological approach. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology, 11(2), 332-353.

- Dlamini, S. D., Gamede, B. T., & Ajani, O. A. (2021). Exploring the challenges of teaching and learning of scarce skills subjects in selected South African high schools. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity, and Change, 15(9), 200-217.

- Engineering Council of South Africa. 2024. Annual report. Accessed from: Date Accessed: 28 January 2025.

- Engineering Profession Act, 46 of 2000.

- González-Pérez, S., Mateos de Cabo, R., & Sáinz, M. (2020). Girls in STEM: Is it a female role-model thing?. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 564148. [CrossRef]

- Guenaga, M., Eguíluz, A., Garaizar, P., & Mimenza, A. (2022). The impact of female role models leading a group mentoring program to promote STEM vocations among young girls. Sustainability, 14(3), 1420. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J. H., Taub, M., Marino, M., Holman, K., & Womack-Adams, K. (2025). Increasing Student Engagement, Fraction Knowledge, and STEM Interest Through Game-Based Intervention. Journal of Special Education Technology, 0(0). [CrossRef]

- Kotkas, T., Holbrook, J., & Rannikmäe, M. (2019). The impact of longitudinal stem careers introducing intervention on students' career aspirations and on relating occupational images. In EduLearn19 Proceedings (pp. 1678-1686). IATED.

- Lane, T. B., Morgan, K., & Lopez, M. M. (2020). "A Bridge Between High School and College": A Case Study of a STEM Intervention Program Enhancing College Readiness Among Underserved Students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 22(1), 155-179. [CrossRef]

- Letsoalo, M. E., Masha, J. K., & Maoto, R. S. (2019). The overall performance of Grade 12 mathematics and physical science learners in South Africa's Gauteng Province. African Journal of Gender, Society & Development, 8(1), 9. [CrossRef]

- Lindner, J., & Makarova, E. (2024). Challenging gender stereotypes: Young women's views on female role models in secondary school science textbooks. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 7, 100376. [CrossRef]

- Manavathu, M., & Zhou, G. (2012). The impact of differentiated instructional materials on English language learner (ELL) students' comprehension of science laboratory tasks. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 12(4), 334-349. [CrossRef]

- Master, A. H., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2020). Cultural stereotypes and sense of belonging contribute to gender gaps in STEM. Grantee Submission, 12(1), 152-198.

- Matshidze, P., Kugara, S. L., & Mdhluli, T. D. (2017). Human rights violations: probing the cultural practice of ukuthwala in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. Gender and Behaviour, 15(2), 9007-9015.

- Merayo, N., & Ayuso, A. (2023). Analysis of barriers, supports and gender gap in the choice of STEM studies in secondary education. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 33(4), 1471-1498. [CrossRef]

- Mkhize, G., & Vilakazi, F. (2021). Rethinking gender and conduits of control: A feminist review. Image & Text, (35), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Mkhize, Z. (2023). Is it transformation or reform? The lived experiences of African women doctoral students in STEM disciplines in South African universities. Higher Education, 86(3), 637-659. [CrossRef]

- Mlambo, Y. A. (2021). Black African women in engineering higher education in South Africa: Contending with history, race, and gender. In Gender Equity in STEM in Higher Education International Perspectives on Policy, Institutional Culture, and Individual Choice (pp. 160-176). Routledge.

- Moore, K. K. (2024). Resilience in the face of sexism: attracting, retaining, and promoting women and girls in STEM (Doctoral dissertation, Pepperdine University).

- Moss-Racusin, C. A., Sanzari, C., Caluori, N., & Rabasco, H. (2018). Gender bias produces gender gaps in STEM engagement. Sex Roles, 79(11), 651-670. [CrossRef]

- Nelson Mandela University. (2025). Change the world: STEM in ACTION. Accessed from: https://steminaction.mandela.ac.za/projects Date accessed: 3 February 2025.

- Nkosi, M. (2014). Ukuthwala "bride abduction" and education: critical challenges and opportunities faced by school principals in rural Kwazulu-Natal. Journal of Social Sciences, 41(3), 441-454. [CrossRef]

- Pollack, E. (2015). The Only Woman in the Room: Why Science Is Still a Boys' Club. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Rainey, K., Dancy, M., Mickelson, R., Stearns, E., & Moller, S. (2018). Race and gender differences in how sense of belonging influences decisions to major in STEM. International journal of STEM education, 5, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Reinking, A., & Martin, B. (2018). The gender gap in STEM fields: Theories, movements, and ideas to engage girls in STEM. Journal of new approaches in educational research, 7(2), 148-153.

- Robinson, W. H., McGee, E. O., Bentley, L. C., Houston, S. L., & Botchway, P. K. (2016). Addressing negative racial and gendered experiences that discourage academic careers in engineering. Computing in Science & Engineering, 18(2), 29-39. [CrossRef]

- Ruder, B., Plaza, D., Warner, R., & Bothwell, M. (2018). STEM women faculty struggling for recognition and advancement in a "men’s club” culture. Exploring the toxicity of lateral violence and microaggressions: Poison in the water cooler, 121-149.

- Saxton, E., Burns, R., Holveck, S., Kelley, S., Prince, D., Rigelman, N., & Skinner, E. A. (2014). A common measurement system for K-12 STEM education: Adopting an educational evaluation methodology that elevates theoretical foundations and systems thinking. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 40, 18-35. [CrossRef]

- Sedebo*, G. T., Shafi, A. A., Muchie, M., & Shatalov, M. Y. (2024). Inclusive STEM education to fight poverty and inequality: The case of South Africa. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Sikhosana, H., Malatji, H., & Munyoro, A. (2023). Experiences and challenges of black women enrolled in a STEM field in a South African urban university: A qualitative study. Cogent Education, 10(2), 2273646. [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. N., & Gayles, J. G. (2018). “Girl power”: Gendered academic and workplace experiences of college women in engineering. Social sciences, 7(1), 11. [CrossRef]

- Steinke, J., & Duncan, T. (2023). Challenging media stereotypes of STEM: Examining an intervention to change adolescent girls’ gender stereotypes of STEM professionals. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology, 15(2), 136-165.

- Student Equity And Talent Management Unit. (2022). Annual Report. Accessed from: https://www.wits.ac.za/media/wits-university/students/setmu/documents/setmu-annual-report2022.pdf Date Accessed: 04 February 2025.

- Kotkas, J. Holbrook, M. Rannikmäe (2019). The impact of longitudinal stem careers introducing intervention on students´ career aspirations and on relating occupational images. The 11th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies Proceedings, pp. 1678-1686.

- Tandrayen-Ragoobur, V., & Gokulsing, D. (2022). Gender gap in STEM education and career choices: what matters?. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 14(3), 1021-1040. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2024). What You Need to Know about the Challenges of STEM in Africa. Accessed from: https://www.iicba.unesco.org/en/what-you-need-know-about-challenges-stem-africa Date Accessed: 03 February 2025.

- United Nations Children’s Fund. 2021. Towards Ending Child Marriage: Global trends and profiles of progress, UNICEF, New York.

- University of Pretoria. (2025). Community Project Module: Joint Community-Based Project (JCP). Accessed from: https://www.up.ac.za/community-project-module/article/3029594/preview?module=cms&slug=content-pages&id=3029594 Date Accessed: 05 February 2025.

- Warsito, W., Siregar, N. C., & Rosli, R. (2023). STEM education and the gender gap: Strategies for encouraging girls to pursue STEM careers. Prima: Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika, 7(2), 191-205. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C., & Lastrapes, R. E. (2022). Impact of STEM sense of belonging on career interest: The role of STEM attitudes. Journal of Career Development, 49(6), 1215-1229. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).