Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Model Description, Data, and Methodology

3.1. Model Description

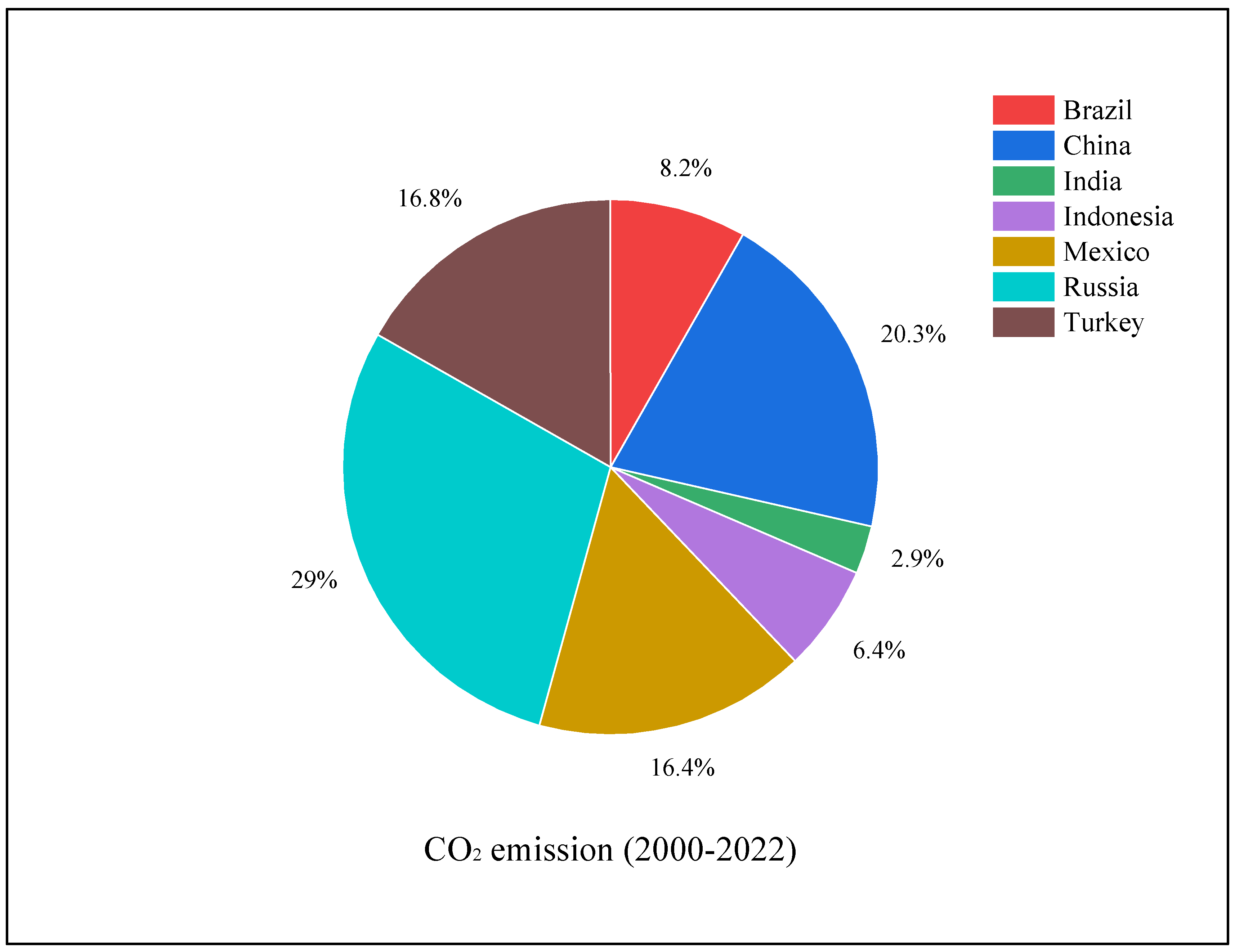

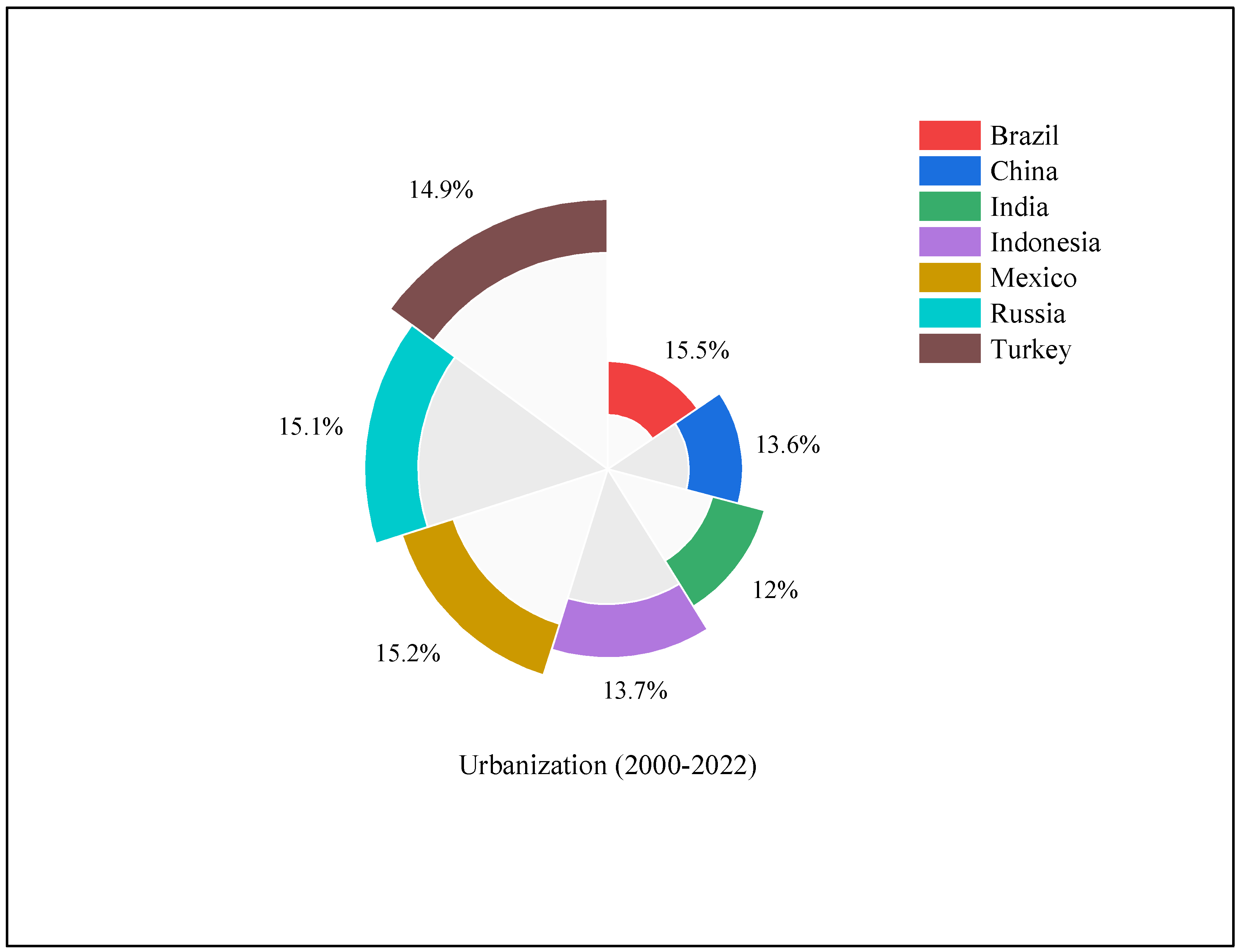

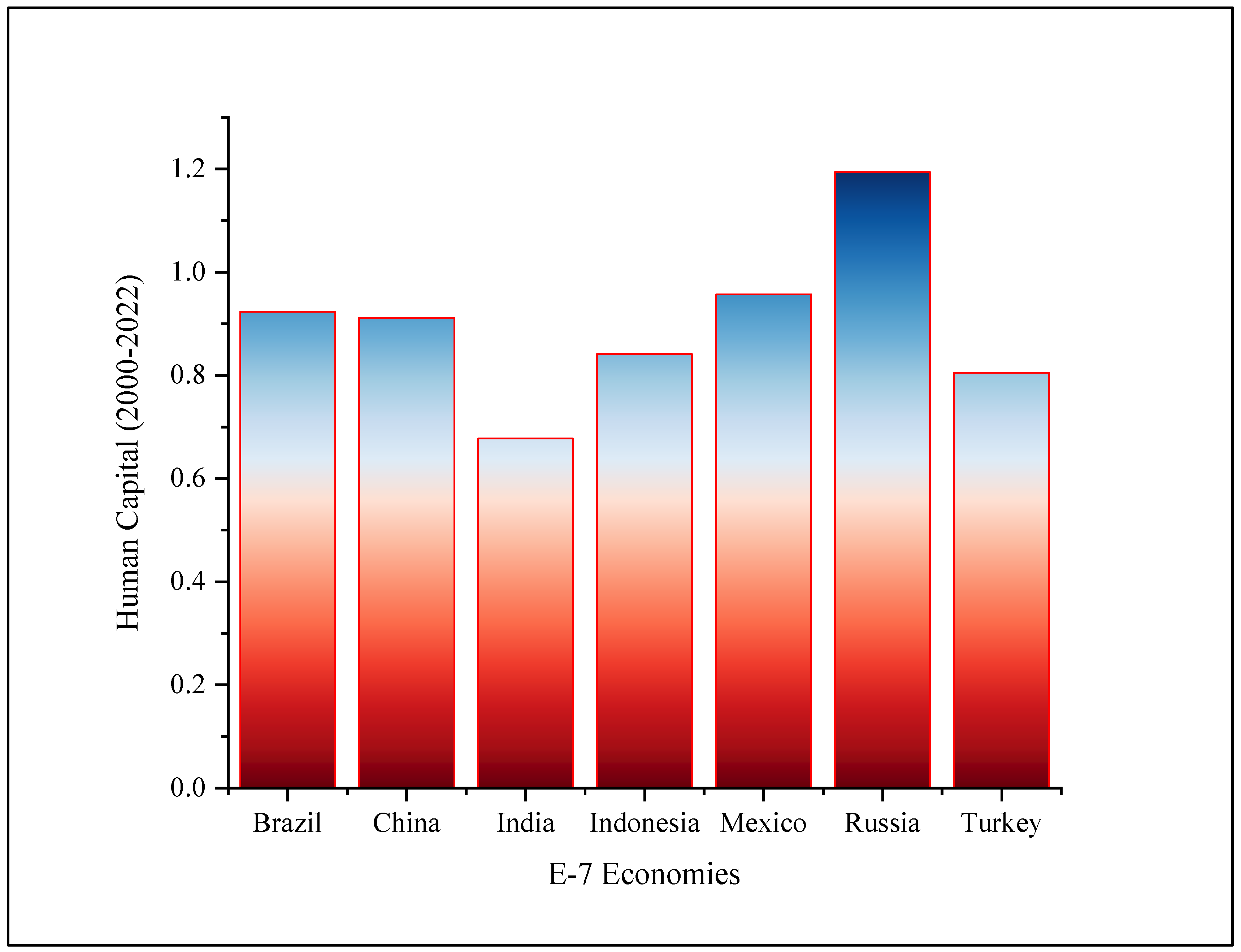

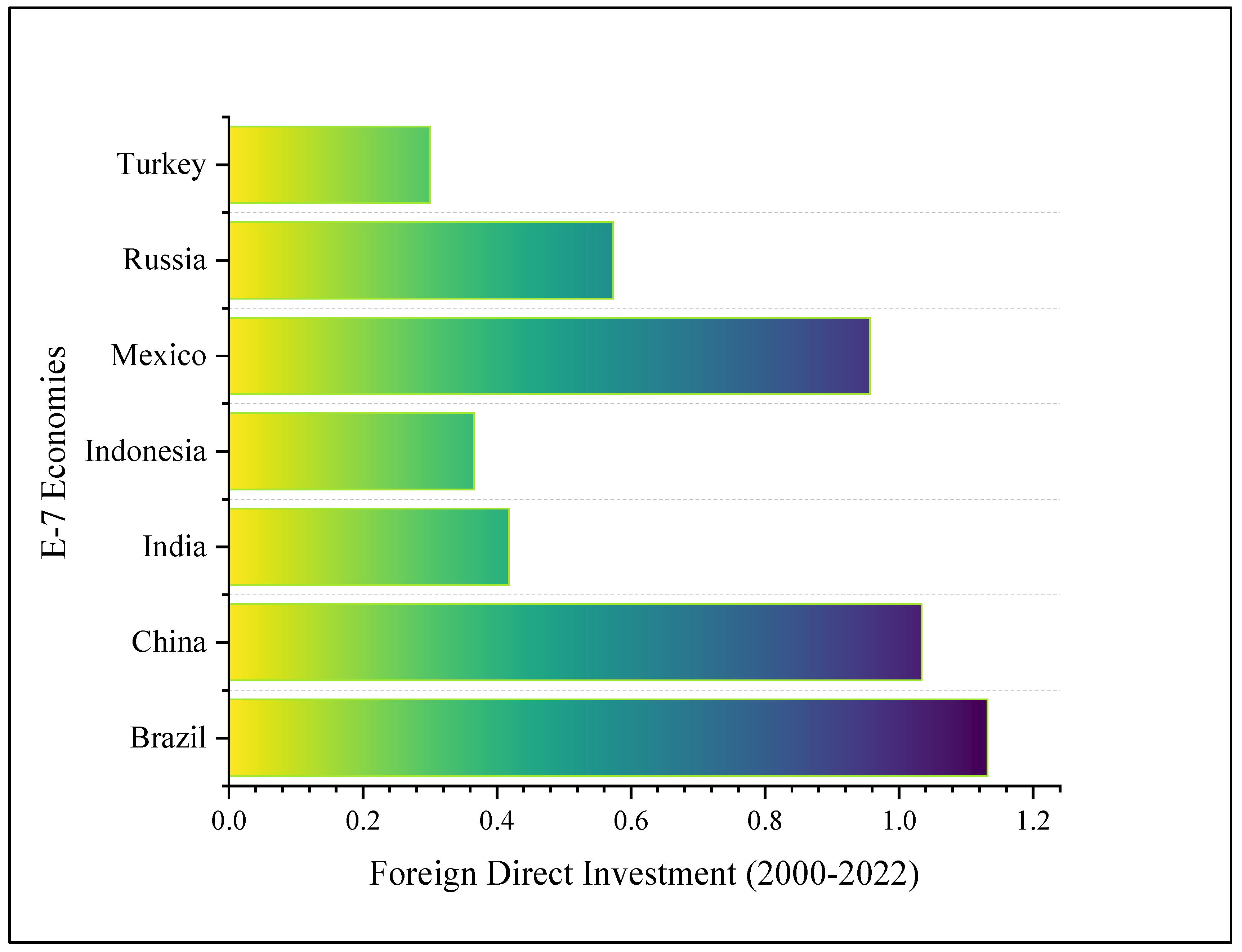

3.2. Data

3.3. Methodology

3.3.1. Cross-Sectional Dependency Test

3.3.2. Panel Unit Root Tests

3.3.3. Panel Cointegration Test

3.3.4. CUP-FM and CUP-BC Approaches

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusion and Policy Propositions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sethi, P.; Chakrabarti, D.; Bhattacharjee, S. Globalization, Financial Development and Economic Growth: Perils on the Environmental Sustainability of an Emerging Economy. J. Policy Model. 2020, 42, 520–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, R.; Deng, Q.; Tillaguango, B.; Méndez, P.; Bravo, D.; Chamba, J.; Alvarado-Lopez, M.; Ahmad, M. Do Economic Development and Human Capital Decrease Non-Renewable Energy Consumption? Evidence for OECD Countries. Energy 2021, 215, 119147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmeen, H.; Tan, Q.; Zameer, H.; Tan, J.; Nawaz, K. Exploring the Impact of Technological Innovation, Environmental Regulations and Urbanization on Ecological Efficiency of China in the Context of COP21. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 274, 111210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, K.; el Moemen, M.A. Energy Consumption, Carbon Dioxide Emissions and Economic Development: Evaluating Alternative and Plausible Environmental Hypothesis for Sustainable Growth. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 74, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, B.; Tzeremes, P.G.; Tzeremes, N.G. Energy Consumption, Economic Growth and Environmental Degradation in OECD Countries. Econ. Model. 2020, 84, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Duan, L.; Guo, Y.; Yu, K. The Effects of FDI, Economic Growth and Energy Consumption on Carbon Emissions in ASEAN-5: Evidence from Panel Quantile Regression. Econ. Model. 2016, 58, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ak, A.; Serener, B.; Xiong, D. Natural Resource Abundance and Financial Development: A Case Study of Emerging Seven (E−7) Economies. Resour. Policy 2020, 67, 101660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, L.; Wei, Z.; Majeed, A.; Alam, I. How FDI and Technology Innovation Mitigate CO2 Emissions in High-Tech Industries: Evidence from Province-Level Data of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 4641–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank World Bank Available online:. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Ozturk, I. Measuring the Impact of Alternative and Nuclear Energy Consumption, Carbon Dioxide Emissions and Oil Rents on Specific Growth Factors in the Panel of Latin American Countries. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2017, 100, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, X. Does Foreign Direct Investment Lead to Lower CO2 Emissions? Evidence from a Regional Analysis in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poumanyvong, P.; Kaneko, S. Does Urbanization Lead to Less Energy Use and Lower CO2 Emissions? A Cross-Country Analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 70, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, R.; Rosa, E.A.; Dietz, T. STIRPAT, IPAT and ImPACT: Analytic Tools for Unpacking the Driving Forces of Environmental Impacts. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 46, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhet, H.A.; Othman, N.S. Impact of Urbanization Growth on Malaysia CO2 Emissions: Evidence from the Dynamic Relationship. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 154, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, A.; Vagnoni, E. A Multi-Level Perspective Analysis of Urban Mobility System Dynamics: What Are the Future Transition Pathways? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 126, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, E.; Norland, I.T. Three Challenges for the Compact City as a Sustainable Urban Form: Household Consumption of Energy and Transport in Eight Residential Areas in the Greater Oslo Region. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 2145–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin, M.; Ali, M.I.; Vink, N.; Gow, J. The Effects of Urbanization and Globalization on CO 2 Emissions: Evidence from the Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) Countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 2699–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Lin, B. Impacts of Urbanization and Industrialization on Energy Consumption/CO2 Emissions: Does the Level of Development Matter? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 1107–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakwa, P.A.; Alhassan, H.; Adu, G. Effect of Natural Resources Extraction on Energy Consumption and Carbon Dioxide Emission in Ghana. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2020, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassi, D.F.; Li, Y.; Riaz, A.; Wang, X.; Batala, L.K. Conditional Effect of Governance Quality on the Finance-Environment Nexus in a Multivariate EKC Framework: Evidence from the Method of Moments-Quantile Regression with Fixed-Effects Models. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 52915–52939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effiong, E.L. On the Urbanization-Pollution Nexus in Africa: A Semiparametric Analysis. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, S. Environmental Kuznets Curve Hypothesis: A Survey. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement. Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. 1991, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoman, W.; Majeed, A.; Vasbieva, D.G.; Yameogo, C.E.W.; Hussain, N. Natural Resources Abundance, Economic Globalization, and Carbon Emissions: Advancing Sustainable Development Agenda. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Muniba; Kirikkaleli, D. Modeling the Dynamic Links among Natural Resources, Economic Globalization, Disaggregated Energy Consumption, and Environmental Quality: Fresh Evidence from GCC Economies. Resour. Policy 2021, 73, 102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, B. The High Cost of Turning Green. Wall Str. J. 1994, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Economic Growth and the Environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.; Ye, C.; Chenyun, Y.; Wei, X. ; Muniba Roles of Natural Resources, Globalization, and Technological Innovations in Mitigation of Environmental Degradation in BRI Economies. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0265755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mulali, U.; Ozturk, I. The Effect of Energy Consumption, Urbanization, Trade Openness, Industrial Output, and the Political Stability on the Environmental Degradation in the MENA (Middle East and North African) Region. Energy 2015, 84, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, N.; Usman, M.; Radulescu, M.; Sinisi, C.I.; Secara, C.G.; Tolea, C. Revisiting EKC Hypothesis in Context of Renewable Energy, Human Development and Moderating Role of Technological Innovations in E-7 Countries? Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1077658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.N.; Li, Z.; Yang, S. Heterogeneous Effects of Urbanization and Environment Kuznets Curve Hypothesis in Africa. Nat. Resour. Forum 2023, 47, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostakis, I.; Armaos, S.; Abeliotis, K.; Theodoropoulou, E. The Investigation of EKC within CO2 Emissions Framework: Empirical Evidence from Selected Cross-Correlated Countries. Sustain. Anal. Model. 2023, 3, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya Kanlı, N.; Küçükefe, B. Is the Environmental Kuznets Curve Hypothesis Valid? A Global Analysis for Carbon Dioxide Emissions. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 2339–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorember, P.T.; Jelilov, G.; Usman, O.; Işık, A.; Celik, B. The Influence of Renewable Energy Use, Human Capital, and Trade on Environmental Quality in South Africa: Multiple Structural Breaks Cointegration Approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 13162–13174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Işık, C.; Ongan, S.; Ozdemir, D.; Jabeen, G.; Sharif, A.; Alvarado, R.; Amin, A.; Rehman, A. Renewable Energy, Climate Policy Uncertainty, Industrial Production, Domestic Exports/Re-Exports, and CO2 Emissions in the USA: A SVAR Approach. Gondwana Res. 2024, 127, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Ullah, S. Effectiveness of Energy Depletion, Green Growth, and Technological Cooperation Grants on CO2 Emissions in Pakistan’s Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Marcel, B.; Majeed, A.; Tsimisaraka, R.S.M. Effects of Transport–Carbon Intensity, Transportation, and Economic Complexity on Environmental and Health Expenditures; Springer Netherlands, 2023; ISBN 0123456789.

- PWT Penn World Table Available online:. Available online: https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/productivity/pwt/?lang=en (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Gu, X.; Baig, I.A.; Shoaib, M.; Zhang, S. Examining the Natural Resources-Ecological Degradation Nexus: The Role of Energy Innovation and Human Capital in BRICST Nations. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haini, H. Examining the Impact of ICT, Human Capital and Carbon Emissions: Evidence from the ASEAN Economies. Int. Econ. 2021, 166, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.J.; Magnani, E. An Exploration of the Conceptual and Empirical Basis of the Environmental Kuznets Curve. Aust. Econ. Pap. 2002, 41, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, R. Relative Backwardness, Direct Foreign Investment, and the Transfer of Technology: A Simple Dynamic Model. Q. J. Econ. 1978, 92, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.H. How Does Foreign Direct Investment Affect Economic Growth in China? Econ. Transit. 2001, 9, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, L. Can Outward Foreign Direct Investment Improve China’s Green Economic Efficiency? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 37295–37309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.; Jiang, P.; Majeed, A.; Raza, M.Y. Does Financial Development and Foreign Direct Investment Improve Environmental Quality? Evidence from Belt and Road Countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 23586–23601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villadsen, A.R.; Wulff, J.N. Statistical Myths About Log-Transformed Dependent Variables and How to Better Estimate Exponential Models. Br. J. Manag. 2021, 32, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.H. General Diagnostic Tests for Cross-Sectional Dependence in Panels. Empir. Econ. 2020, 0435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. A Simple Panel Unit Root Test in the Presence of Cross-section Dependence. J. Appl. Econom. 2007, 22, 265–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C. Spurious Regression and Residual-Based Tests for Cointegration in Panel Data. J. Econom. 1999, 90, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P. Panel Cointegration: Asymptotic and Finite Sample Properties of Pooled Time Series Tests with an Application to the PPP Hypothesis. Econom. Theory 2004, 20, 597–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, J. Testing for Error Correction in Panel Data. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2007, 69, 709–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Kao, C. On the Estimation and Inference of a Panel Cointegration Model with Cross-Sectional Dependence. In; Elsevier, 2006; Vol. 274, pp. 3–30.

- Mark, N.C.; Ogaki, M.; Sul, D. Dynamic Seemingly Unrelated Cointegrating Regressions. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2005, 72, 797–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ivanovski, K.; Inekwe, J.; Smyth, R. Human Capital and CO2 Emissions in the Long Run. Energy Econ. 2020, 91, 104907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Wang, X.; Cong, X. How Does Foreign Direct Investment Affect CO2 Emissions in Emerging Countries?New Findings from a Nonlinear Panel Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Zhao, X.; Yan, X.; Wang, C.; Li, Q. Energy Technological Progress, Energy Consumption, and CO2 Emissions: Empirical Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitić, P.; Ivanović, O.M.; Zdravković, A. A Cointegration Analysis of Real Gdp and CO2 Emissions in Transitional Countries. Sustainability 2017, 9, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Sun, T.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Modeling the Nexus between Carbon Dioxide Emissions and Economic Growth. Energy Policy 2015, 86, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Shahzad, S.J.H.; Ahmad, N.; Alam, S. Financial Development and Environmental Quality: The Way Forward. Energy Policy 2016, 98, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Zhao, Y.N. Heterogeneity Analysis of Factors Influencing CO2 Emissions: The Role of Human Capital, Urbanization, and FDI. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 185, 113644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, B.; Lorente, D.B.; Ali Nasir, M. European Commitment to COP21 and the Role of Energy Consumption, FDI, Trade and Economic Complexity in Sustaining Economic Growth. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 273, 111146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdouli, M.; Omri, A. Exploring the Nexus Among FDI Inflows, Environmental Quality, Human Capital, and Economic Growth in the Mediterranean Region. J. Knowl. Econ. 2021, 12, 788–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Breusch-Pagan LM Test | Pesaran Scaled LM Test | Adjusted LM Test | Pesaran CD Test | ∆ | Adj.∆ | |

| CO2 | 315.302a | 17.833a | 127.934a | 12.582a | 29.87a | 103.109a |

| HC | 235.733a | 18.356a | 224.55a | 42.186a | 70.144a | 138.655a |

| URB | 179.885a | 37.878a | 138.041a | 54.954a | 57.97a | 126.852a |

| FDI | 244.548a | 27.477a | 109.788a | 21.012a | 49.767a | 122.94a |

| EC | 406.663a | 26.557a | 123.517a | 53.829a | 59.177a | 55.843a |

| GDP | 169.386a | 31.385a | 213.025a | 30.683a | 33.853a | 87.594a |

| Variables | CADF statistic | CIPS statistic | CADF statistic | CIPS statistic | ||||

| Constant | Constant | Constant and trend | Constant and trend | |||||

| Level | 1st difference | Level | 1st difference | Level | 1st differences | Level | 1st difference | |

| CO2 | -2.005 | -4.048a | -1.821 | -6.149a | -2.634 | -7.823a | -1.14 | -3.253a |

| HC | -1.527 | -4.299a | -1.209 | -6.532a | -1.808 | -4.677a | -2.531 | -2.973a |

| URB | -2.923 | -2.868a | -2.932 | -3.473a | -2.052 | -3.786a | -2.463 | -4.604a |

| FDI | -1.886 | -3.007a | -1.851 | -2.094a | -1.851 | -3.191a | -2.782 | -7.095a |

| EC | -2.827 | -7.876a | -2.069 | -4.573a | -1.413 | -4.898a | -1.918 | -7.423a |

| GDP | -1.471 | -6.487a | -2.304 | -5.759a | -2.956 | -3.241a | -2.635 | -4.775a |

| Pedroni [50] | |||||

| Within-dimension | Statistics | Prob. | Between-dimension | Statistic | Prob. |

| Panel v-Statistic | 1.788b | 0.038 | Group rho-Statistic | 1.313 | 0.904 |

| Panel rho-Statistic | 0.648 | 0.742 | Group PP-Statistic | -2.228b | 0.014 |

| Panel PP-Statistic | -2.328b | 0.010 | Group ADF-Statistic | -2.315b | 0.010 |

| Panel ADF-Statistic | -2.418a | 0.008 | |||

| Kao [49] | t-Statistic | Prob. | Westerlund [51] | Z-Value | P-Value |

| ADF | -2.175b | 0.014 | Gt | -4.069a | 0.000 |

| Ga | 1.658 | 0.951 | |||

| Pt | -3.145a | 0.000 | |||

| Pa | -0.862 | 0.194 | |||

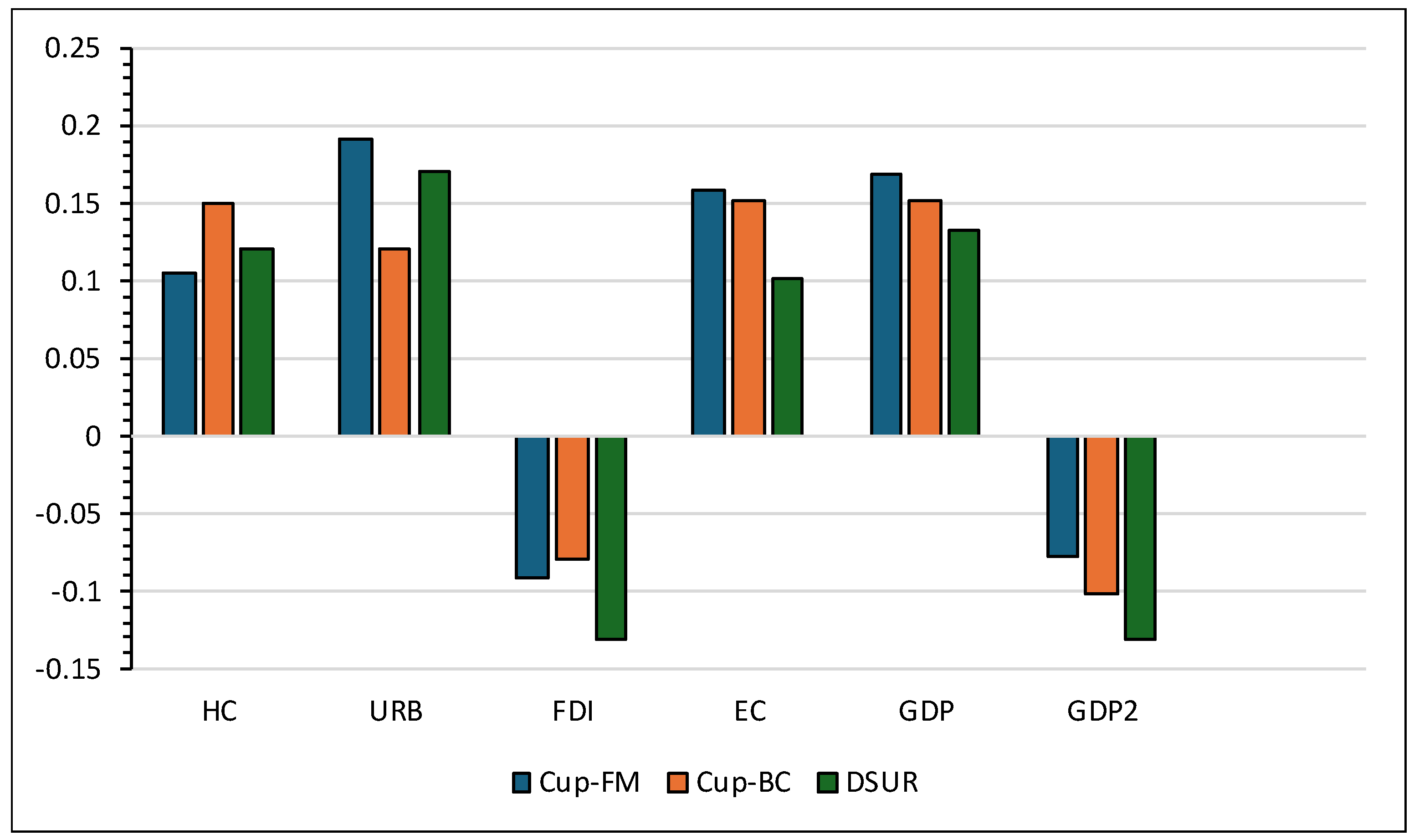

| Variables | CUP-FM | CUP-BC | DSUR | ||||||

| Coeff. | Std. error | t-stat | Coeff. | Std. error | t-stat | Coeff. | Std. error | t-stat | |

| HC | 0.105a | 0.036 | 3.052 | 0.149a | 0.039 | 3.858 | 0.121a | 0.018 | 7.989 |

| URB | 0.191b | 0.038 | 2.414 | 0.120a | 0.023 | 5.956 | 0.170a | 0.027 | 6.543 |

| FDI | -0.092a | 0.023 | -3.693 | -0.080b | 0.037 | -2.131 | -0.131a | 0.016 | -7.707 |

| EC | 0.158a | 0.022 | 7.254 | 0.151a | 0.022 | 7.189 | 0.102a | 0.018 | 5.655 |

| GDP | 0.168a | 0.026 | 6.151 | 0.151a | 0.033 | 5.006 | 0.133a | 0.022 | 6.377 |

| GDP2 | -0.077b | 0.035 | -2.148 | -0.101a | 0.020 | -4.871 | -0.131a | 0.026 | -4.672 |

| C | 11.238a | 0.242 | 46.797 | 10.843a | 0.241 | 45.151 | 16.942a | 0.242 | 70.548 |

| R2 | 0.889 | 0.898 | 0.906 | ||||||

| Adj R2 | 0.951 | 0.937 | 0.945 | ||||||

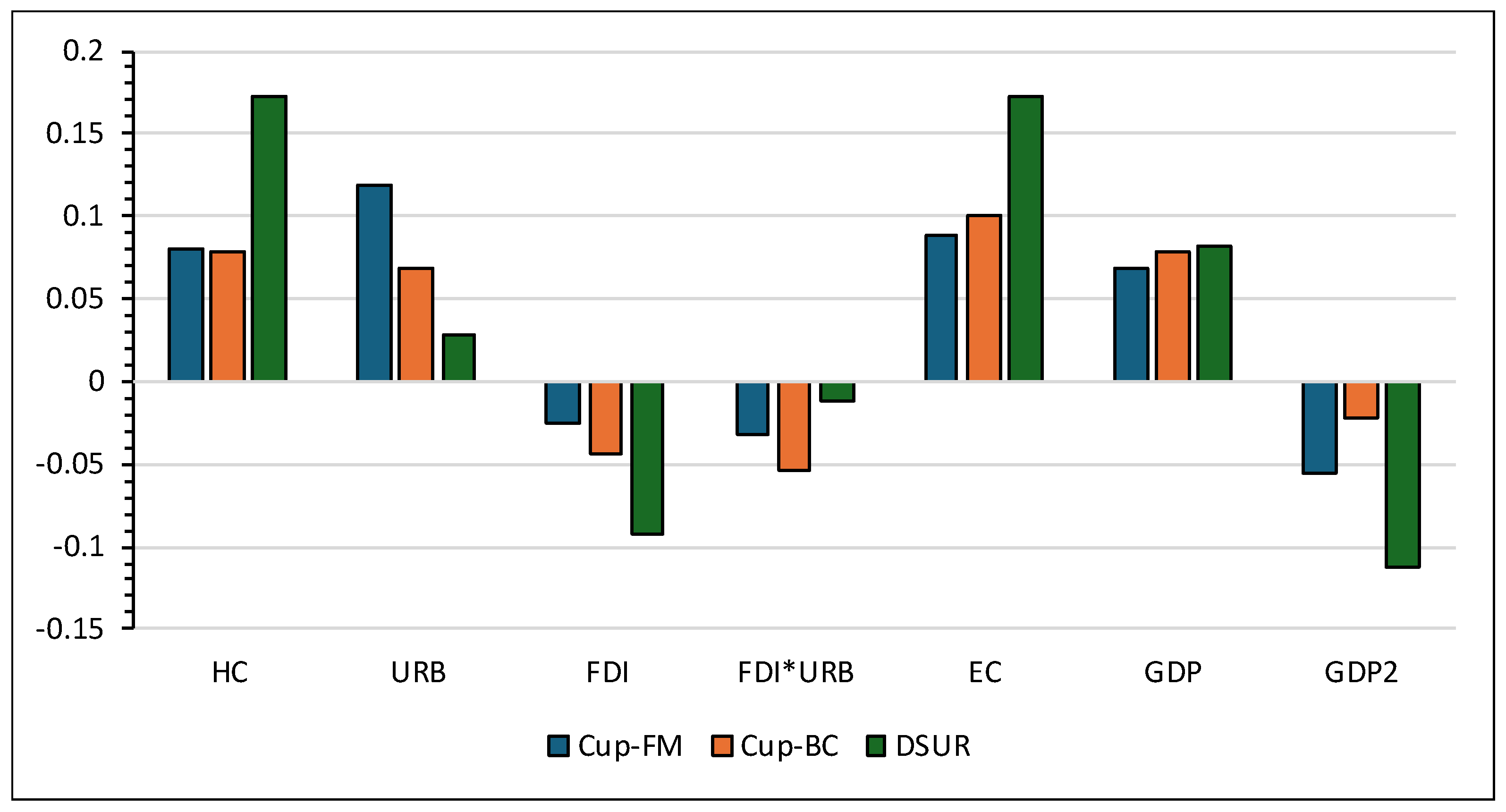

| Variables | CUP-FM | CUP-BC | DSUR | ||||||

| Coeff. | Std. error | t-stat | Coeff. | Std. error | t-stat | Coeff. | Std. error | t-stat | |

| HC | 0.080a | 0.016 | 3.665 | 0.078a | 0.004 | 27.808 | 0.172a | 0.005 | 27.125 |

| URB | 0.118a | 0.018 | 11.128 | 0.068a | 0.008 | 12.505 | 0.028a | 0.012 | 2.624 |

| FDI | -0.025a | 0.007 | -3.493 | -0.043a | 0.005 | -7.927 | -0.092a | 0.009 | -9.408 |

| FDI*URB | -0.032a | 0.013 | -2.661 | -0.054a | 0.008 | -24.456 | -0.012a | 0.009 | -22.654 |

| EC | 0.088a | 0.009 | 9.436 | 0.100a | 0.003 | 25.743 | 0.173a | 0.011 | 17.362 |

| GDP | 0.068a | 0.008 | 22.654 | 0.078a | 0.009 | 10.202 | 0.082a | 0.007 | 10.505 |

| GDP2 | -0.055a | 0.007 | -13.133 | -0.022a | 0.005 | -3.656 | -0.112a | 0.003 | -23.664 |

| C | 10.365a | 0.360 | 42.568 | 11.324a | 0.356 | 42.453 | 18.467a | 0.356 | 77.678 |

| R2 | 0.901 | 0.910 | 0.920 | ||||||

| Adj R2 | 0.961 | 0.957 | 0.967 | ||||||

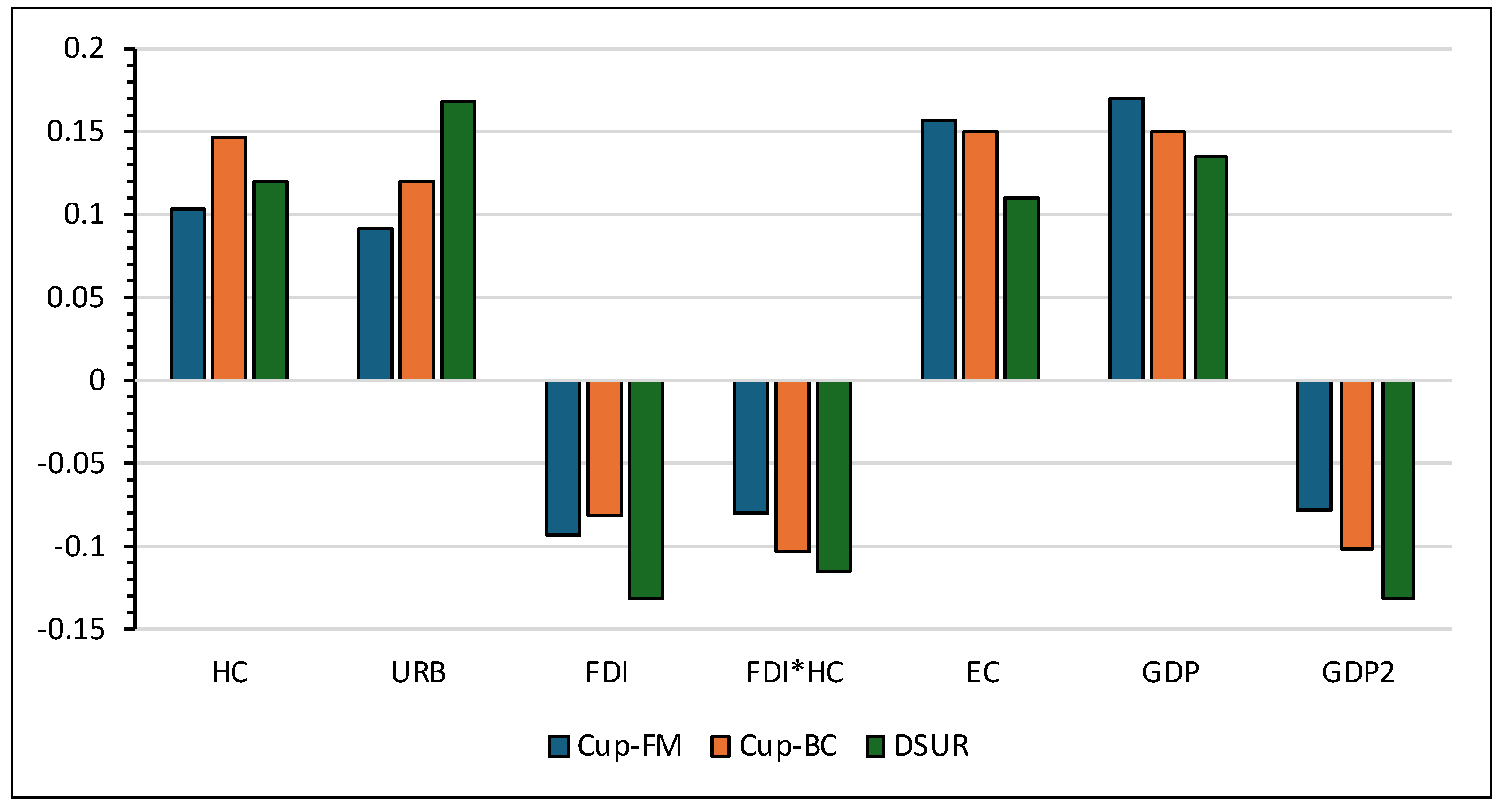

| Variables | CUP-FM | CUP-BC | DSUR | ||||||

| Coeff. | Std. error | t-stat | Coeff. | Std. error | t-stat | Coeff. | Std. error | t-stat | |

| HC | 0.103c | 0.033 | 3.050 | 0.147b | 0.038 | 3.851 | 0.119a | 0.015 | 7.988 |

| URB | 0.091c | 0.037 | 2.412 | 0.119a | 0.022 | 5.955 | 0.168a | 0.025 | 6.540 |

| FDI | -0.094b | 0.025 | -3.696 | -0.081b | 0.038 | -2.130 | -0.132a | 0.017 | -7.708 |

| FDI*HC | -0.080a | 0.028 | -4.987 | -0.103a | 0.044 | -6.346 | -0.115a | 0.033 | -5.876 |

| EC | 0.157a | 0.021 | 7.253 | 0.150a | 0.021 | 7.188 | 0.109a | 0.019 | 5.654 |

| GDP | 0.169a | 0.027 | 6.152 | 0.150a | 0.033 | 5.007 | 0.135a | 0.021 | 6.379 |

| GDP2 | -0.078c | 0.036 | -2.149 | -0.102a | 0.021 | -4.872 | -0.132a | 0.028 | -4.674 |

| C | 11.237a | 0.240 | 46.795 | 10.842a | 0.240 | 45.150 | 16.941a | 0.240 | 70.549 |

| R2 | 0.888 | 0.899 | 0.905 | ||||||

| Adj R2 | 0.950 | 0.938 | 0.944 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).