Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

2.2. RNA Extraction, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Amplification, Sequencing, and Genome Assembly

2.3. HIV Sequencing and Subtyping

2.4. HIV Drug Resistance Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

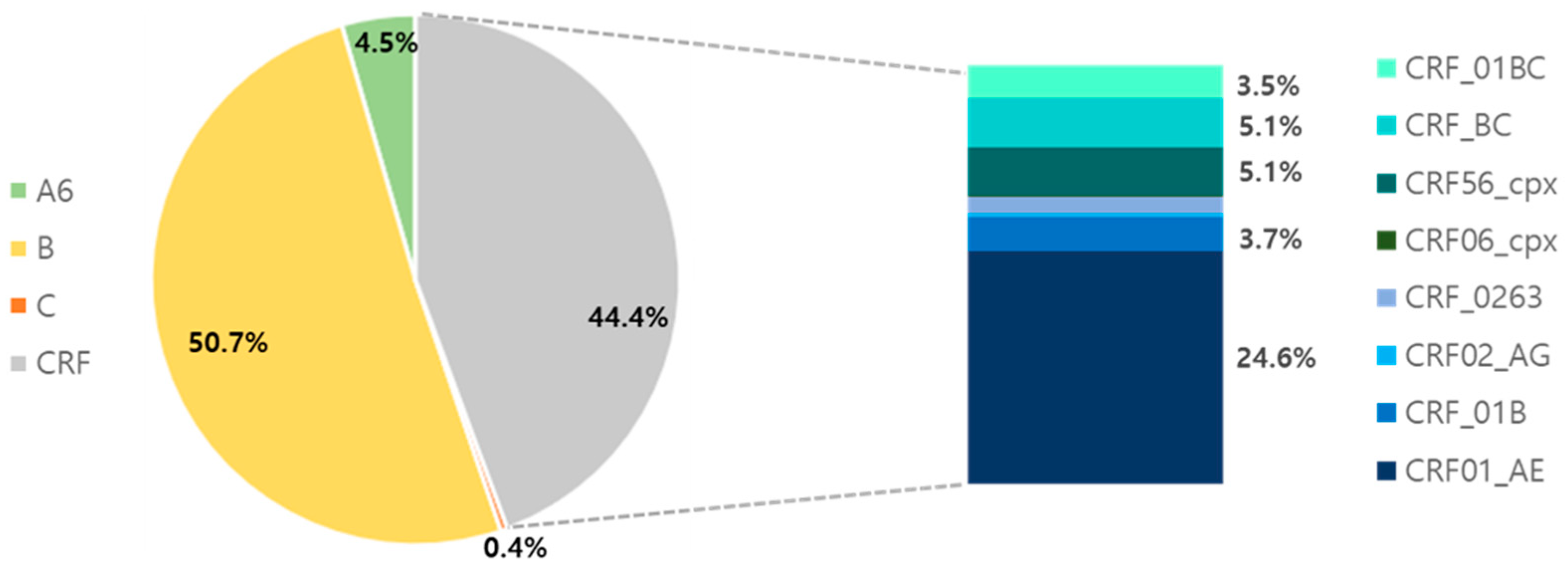

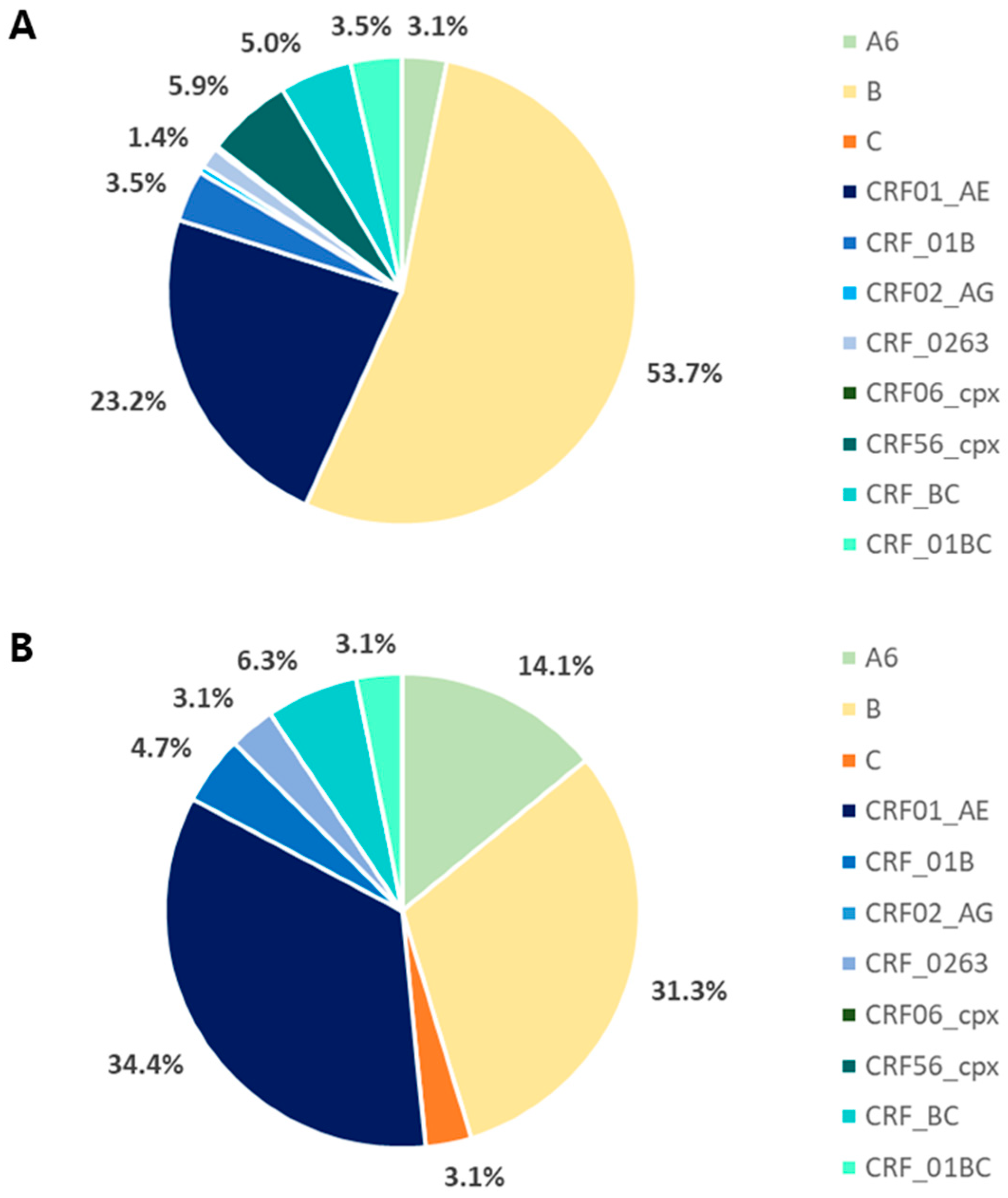

3.2. Genetic Diversity

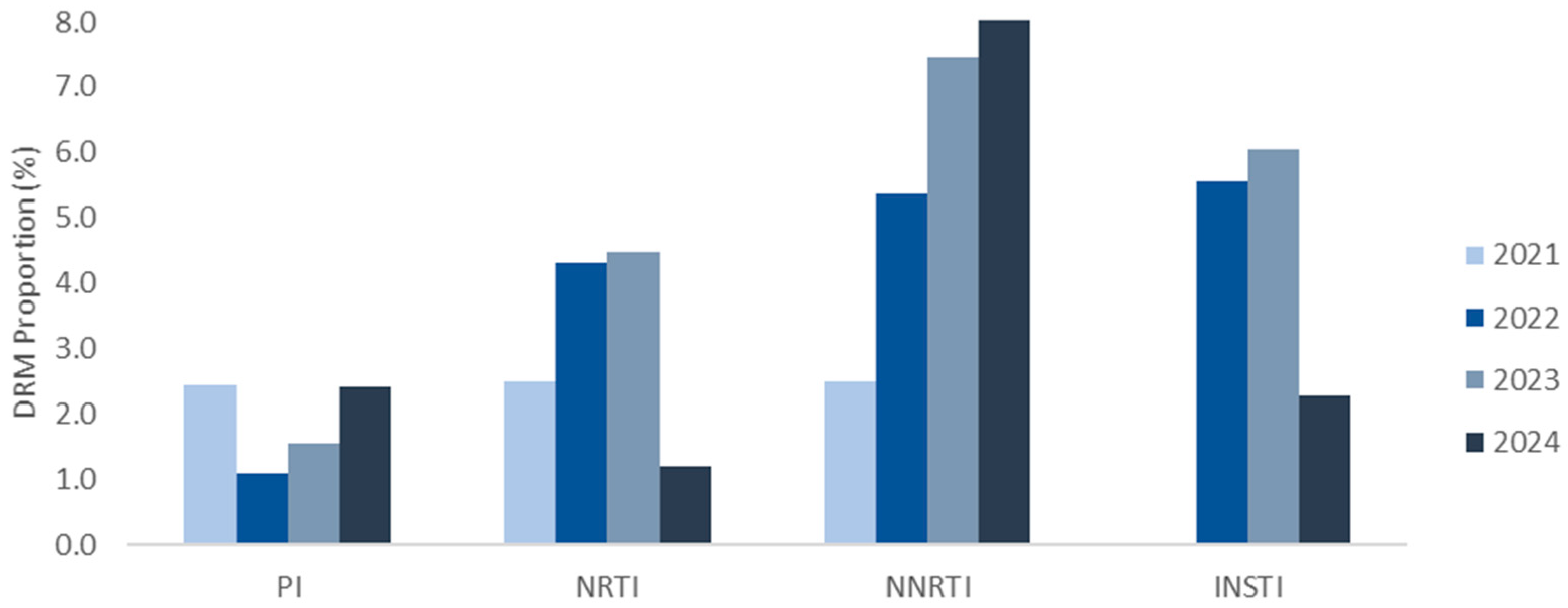

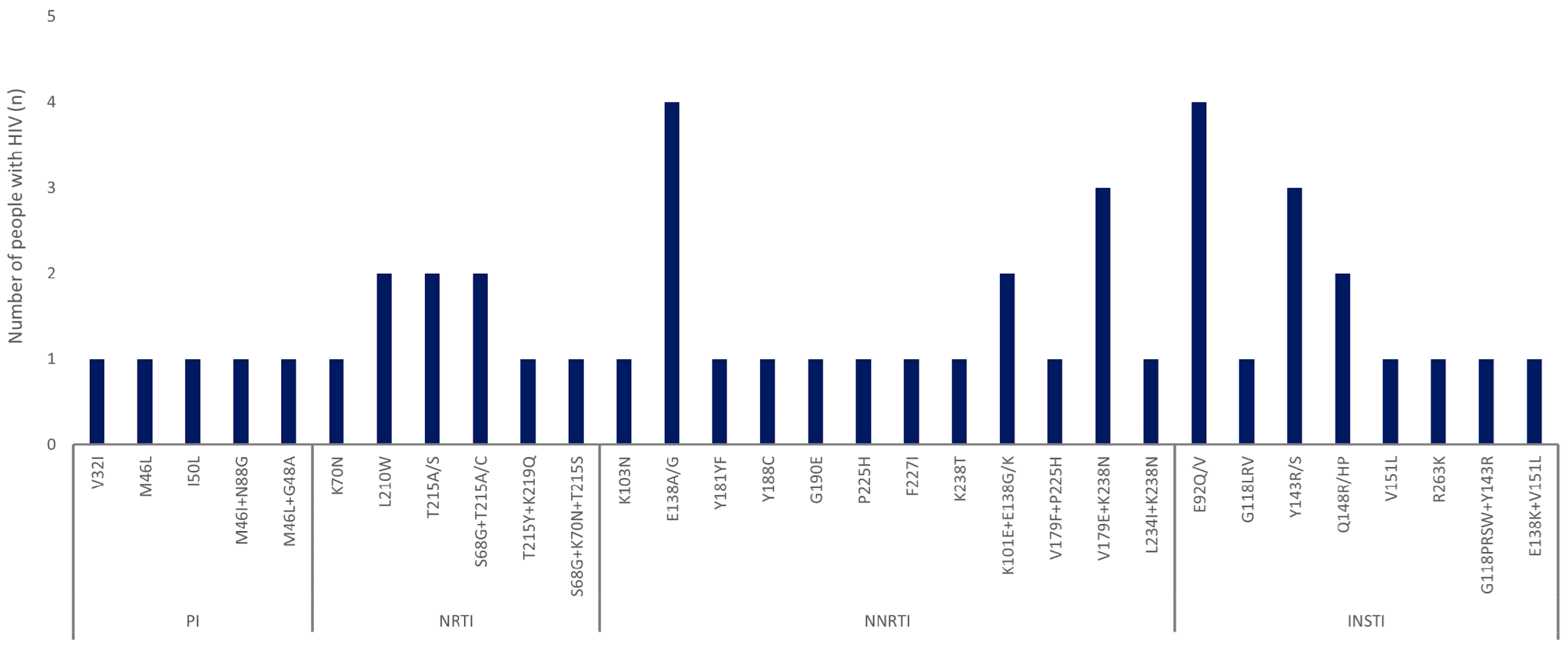

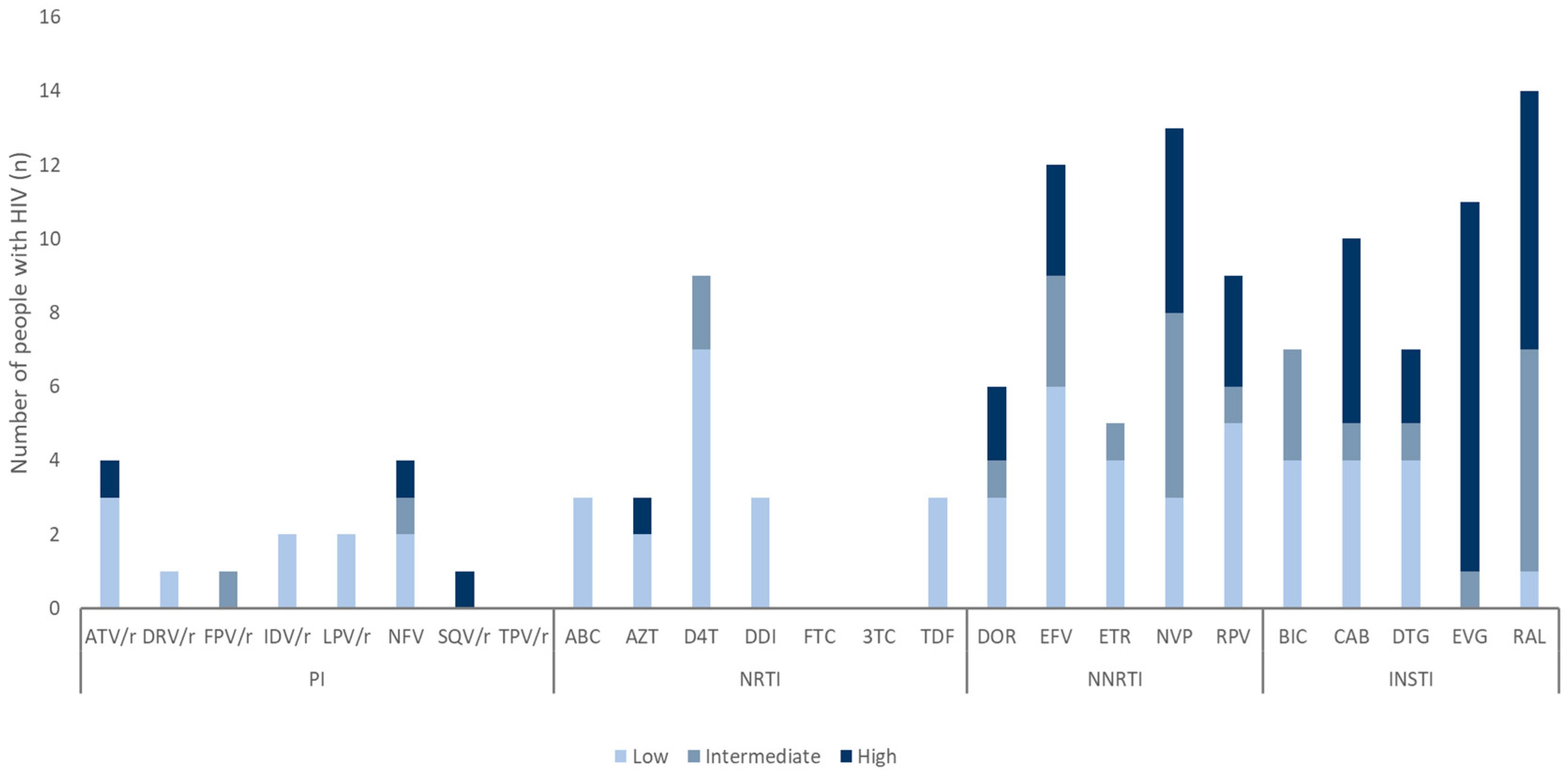

3.3. Distribution and Characterization of DRMs

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PWH | People with HIV |

| ARV | Antiretroviral |

| ART | Antiretroviral therapy |

| DRMs | Drug resistance mutations |

| TDRMs | Transferred drug resistance mutations |

| KDCA | Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| S | Susceptible |

| PLR | Potential low-level resistance |

| LR | Low-level resistance |

| IR | Intermediate resistance |

| HR | High-level resistance |

| PI | Protease inhibitor |

| ATV/r | Atazanavir |

| DRV/r | Darunavir |

| FPV/r | Fosamprenavir |

| IDV/r | Indinavir |

| LPV/r | Lopinavir |

| NFV | Nelfinavir |

| SQV/r | Saquinavir |

| TPV/r | Tipranavir |

| NRTIs | Nucleoside |

| ABC | Abacavir |

| AZT | Zidovudine |

| D4T | Stavudine |

| DDI | Didanosine |

| FTC | Emtricitabine |

| 3TC | Lamivudine |

| TDF | Tenofovir |

| NNRTI | Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor |

| DOR | Doravirine |

| EFV | Efavirenz |

| ETR | Etravirine |

| NVP | Nevirapine |

| RPV | Rilpivirine |

| INSTI | Integrase strand transfer inhibitor |

| BIC | Bictegravir |

| CAB | Cabotegravir |

| DTG | Dolutegravir |

| EVG | Elvitegravir |

| RAL | Raltegravir |

| CRF | Circulating recombinant form |

References

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global HIV Statistics Fact sheet 2024. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf (accessed on 15 Jan 2025).

- Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Annual Report on HIV/AIDS Notifications in Korea, 2023.

- Peter, T.; Ellenberger, D.; Kim, A.A.; Boeras, D.; Messele, T.; Roberts, T.; Stevens, W.; Jani, I.; Abimiku, A.; Ford, N.; et al. Early antiretroviral therapy initiation: access and equity of viral load testing for HIV treatment monitoring. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e26–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blassel, L.; Zhukova, A.; Villabona-Arenas, C.J.; Atkins, K.E.; Hué, S.; Gascuel, O. Drug resistance mutations in HIV: new bioinformatics approaches and challenges. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2021, 51, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geremia, N.; Basso, M.; De Vito, A.; Scaggiante, R.; Giobbia, M.; Battagin, G.; Dal Bello, F.; Giordani, M.T.; Nardi, S.; Malena, M.; et al. Patterns of transmitted drug resistance mutations and HIV-1 subtype dynamics in ART-naïve individuals in Veneto, Italy, from 2017 to 2024. Viruses 2024, 16, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, S.G.; Andreis, S.; Scaggiante, R.; Cruciani, M.; Ferretto, R.; Manfrin, V.; Panese, S.; Rossi, M.C.; Francavilla, E.; Boldrin, C.; et al. Decreasing trends of drug resistance and increase of non-B subtypes amongst subjects recently diagnosed as HIV-infected over the period 2004–2012 in the Veneto Region, Italy. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2013, 1, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.; Gettins, L.; Fuller, M.; Kirtley, S.; Hemelaar, J. Global and regional genetic diversity of HIV-1 in 2010–21: systematic review and analysis of prevalence. Lancet Microbe. 2024, 5, 100912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.R.; Sim, H.J.; Wang, J.; Han, M. Analysis of genotype and drug resistance of human immunodeficiency virus in Korea from 2018–2019. Public health weekly report (PHWR). 2020, 13, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Wang, J.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, S.; Kim, E.J.; Han, M. Genetic diversity and drug resistance of human immunodeficiency virus from newly diagnosed human immunodeficiency virus positive in Korean. 2022–2023. Public Health Weekly Report (PHWR) 2024, 17, 44.

- World Health Organization. WHO manual for HIV drug resistance testing using dried blood spot specimens. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240009424 (accessed on 3 Febr 2025).

- Stanford University. HIV Drug resistance database. HIVDB User Guide [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://hivdb.stanford.edu/pages/documentPage/user_guide.pdf (accessed on 20 Jan 2025).

- Los Alamos National Laboratory. HIV circulating recombinant forms (CRFs) [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.hiv.lanl.gov/components/sequence/HIV/crfdb/crfs.comp (accessed on 20 Jan 2025).

- Chung, Y.S.; Choi, J.Y.; Yoo, M.S.; Seong, J.H.; Choi, B.S.; Kang, C. Phylogenetic transmission clusters among newly diagnosed antiretroviral drug-naïve patients with human immunodeficiency virus-1 in Korea: A study from 1999 to 2012. PLOS One 2019, 14, e0217817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Kim, N.J.; Choi, J.Y.; Chin, B.S. History of acquired immune deficiency syndrome in Korea. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 52, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Menon, S.; Crowe, M.; Agarwal, N.; Biccler, J.; Bbosa, N.; Ssemwanga, D.; Adungo, F.; Moecklinghoff, C.; Macartney, M.; et al. Geographic and population distributions of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 and HIV-2 circulating subtypes: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis (2010–2021). J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228, 1583–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bbosa, N.; Kaleebu, P.; Ssemwanga, D. HIV subtype diversity worldwide. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 2019, 14, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Society for AIDS. Summary of 2021 clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of HIV/AIDS in HIV-infected Koreans. Infect. Chemother. 2021, 53, 592–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluis-Cremer, N.; Jordan, M.R.; Huber, K.; Wallis, C.L.; Bertagnolio, S.; Mellors, J.W.; Parkin, N.T.; Harrigan, P.R. E138A in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase is more common in subtype C than B: implications for rilpivirine use in resource-limited settings. Antiviral Res. 2014, 107, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford University. HIV Drug resistance database. nnrti Resistance Notes. HIVdb version 9.8 [Internet]. Available online: https://hivdb.stanford.edu/dr-summary/resistance-notes/nnrti (accessed on 6 Mar 2025).

- Hatano, H.; Lampiris, H.; Fransen, S.; Gupta, S.; Huang, W.; Hoh, R.; Martin, J.N.; Lalezari, J.; Bangsberg, D.; Petropoulos, C.; et al. Evolution of integrase resistance during failure of integrase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2010, 54, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; Yin, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Z.; et al. HIV-1 transmitted drug resistance-associated mutations and mutation co-variation in HIV-1 treatment-naïve MSM from 2011 to 2013 in Beijing, China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.L.; Liang, H.Y.; Xiao, J.; Li, R.; Yu, F.T.; Zeng, Y.Q.; Pang, X.L.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, B.; et al. The effect of pretreatment potential resistance to NNRTIs on antiviral therapy in patients with HIV/AIDS. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2022, 91, S27–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vink, J.; McFaul, K.; Bradshaw, D.; Nelson, M. Does the presence of a mutation at position V179 impact on virological outcome in patients receiving antiretroviral medication? J. Infect. 2016, 72, 632–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzon-Martin, L.; Navarro-San Francisco, C.; Fernandez-Regueras, M.; Sanchez-Gomez, L. Integrase strand transfer inhibitor resistance mediated by R263K plus E157Q in a patient with HIV infection treated with bictegravir/tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine: case report and review of the literature. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 1153–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charpentier, C.; Descamps, D. Resistance to HIV integrase inhibitors: about R263K and E157Q mutations. Viruses. 2018, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbhele, N.; Chimukangara, B.; Gordon, M. HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitors: a review of current drugs, recent advances and drug resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2021, 57, 106343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainberg, M.A.; Han, Y.S. HIV-1 resistance to dolutegravir: update and new insights. J. Virus Erad. 2015, 1, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washaya, T.; Manasa, J.; Kouamou, V. HIV drug resistance monitoring in the era of dolutegravir and injectable long-acting cabotegravir in resource-limited settings. AIDS 2023, 37, 1629–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. New Report Documents Increase in HIV Drug Resistance to Dolutegravir. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-03-2024-new-report-documents-in-hiv-drug-resistance-to-dolutegravir (accessed on 23 Jan 2025).

- World Health Organization. HIV Drug Resistance: Brief Report, 2024.

- Lessells, R.J.; Katzenstein, D.K.; de Oliveira, T. Are subtype differences important in HIV drug resistance? Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012, 2, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.S.; Mesplède, T.; Wainberg, M.A. Differences among HIV-1 subtypes in drug resistance against integrase inhibitors. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016, 46, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, B.; Akanmu, A.S.; Inzaule, S.C.; Samuels, J.O.; Okonkwo, P.; Ilesanmi, O.; Adewole, I.F.A.; Asadu, C.; Khamofu, H.; Mpazanje, R.; et al. Association between HIV-1 subtype and drug resistance in Nigerian infants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO HIVResNet HIV drug resistance laboratory operational framework. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978-92-4-000987-5 (accessed on 3 Febr 2025).

| Variables | n (%) by collection year | ||||

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||

| Sex | Male | 92 (92.9) | 137 (95.8) | 142 (95.9) | 93 (95.9) |

| Female | 7 (7.1) | 5 (3.5) | 6 (4.1) | 4 (4.1) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Country of origin | Korean | 83 (83.8) | 121 (84.6) | 133 (89.9) | 86 (88.7) |

| Non-Korean | 16 (16.2) | 22 (15.4) | 15 (10.1) | 11 (11.3) | |

| Antiretroviral drug resistance n (%) | |||||||

| PI | NRTI | NNRTI | INSTI |

PI +NRTI |

PI +NNRTI |

NRTI +NNRTI |

|

| Total | 3 (1.1) | 5 (1.8) | 14 (4.9) | 14 (3.8) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.1) |

| B | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.8) | 7 (4.2) | 8 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.8) |

| Non-B | 2 (1.7) | 2 (1.7) | 7 (5.9) | 6 (3.4) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).