Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

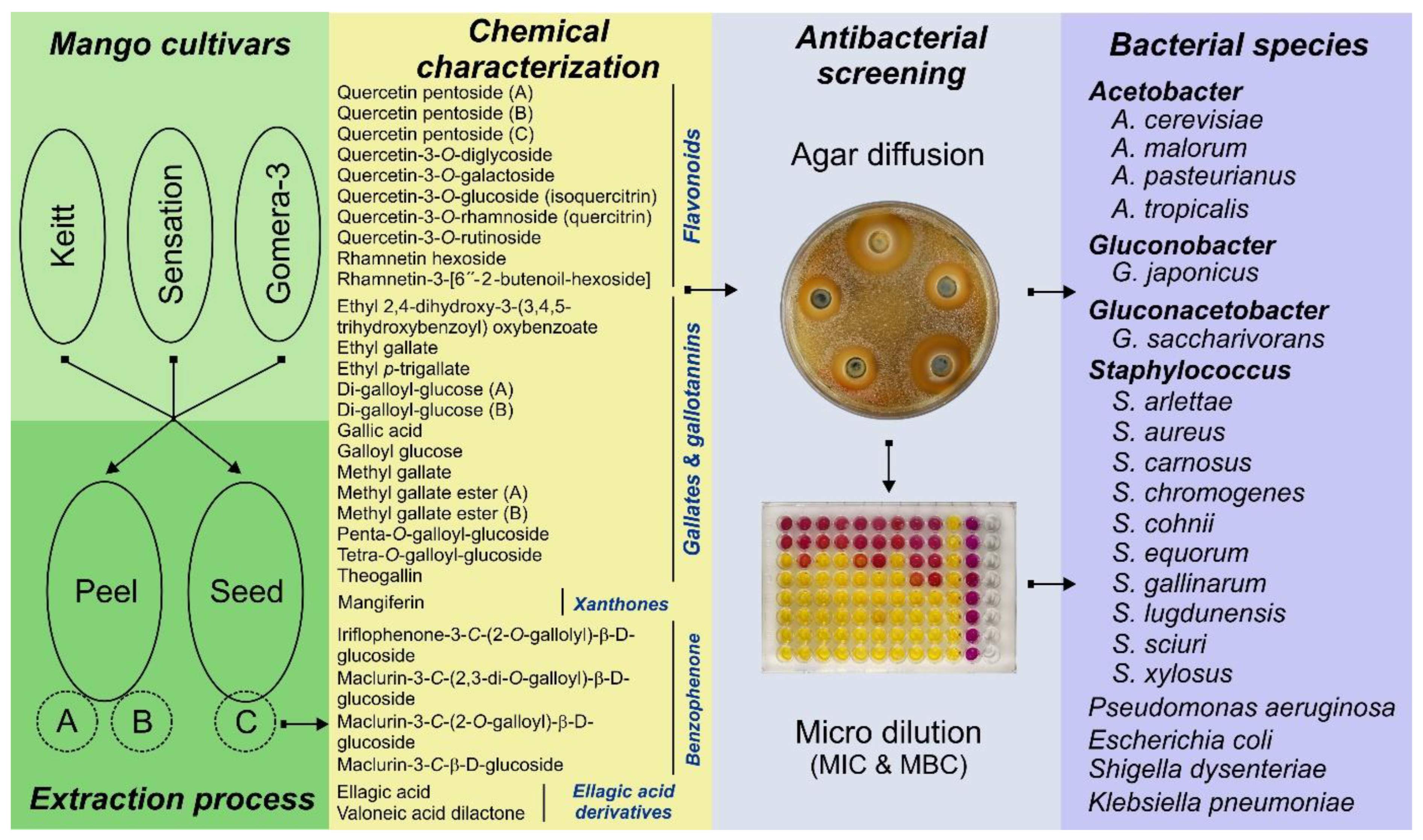

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Collection and Preparation of Mango By-Products Extracts

2.2. Bacterial Species and Culture Conditions

2.3. Antibacterial Screening

2.3.1. Agar Diffusion Assay

2.3.2. Micro-Dilution Antibacterial Assay

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

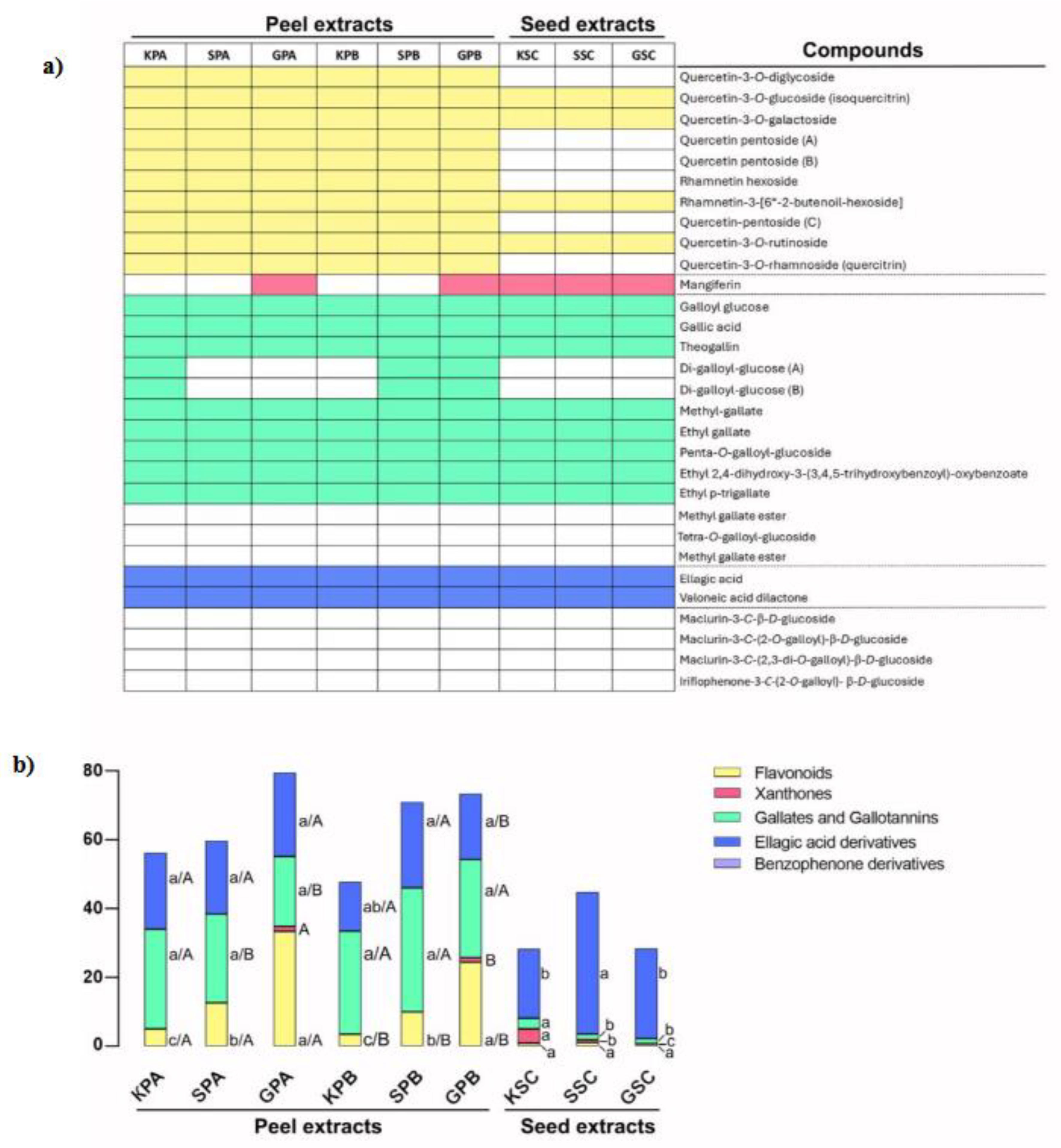

3.1. Bioactive Compound in Mango By-Products Extracts

3.2. Antibacterial Activity of Mango By-Products

3.2.1. Acetic Acid Bacteria

3.2.2. Staphylococcus Species

3.2.3. Human Pathogenic Bacteria

4. Discussion

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAB | Acetic Acid Bacteria |

| FAE | Fermentation-Assisted Extraction |

| GAE | mg gallic acid equivalents per mL |

| GPA | Gomera Peel, extraction A |

| GPB | Gomera Peel, extraction B |

| GSC | Gomera Seed, extraction C |

| MBC | Minimum Bactericidal Concentration |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| KPA | Keitt Peel, extraction A |

| KPB | Keitt Peel, extraction B |

| KSC | Keitt Seed, extraction C |

| SAE | Solvent-Assisted Extraction |

| SPA | Sensation Peel, extraction A |

| SPB | Sensation Peel, extraction B |

| SSC | Sensation Seed, extraction C |

References

- Sabel, A.; Bredefeld, S.; Schlander, M.; Claus, H. Wine Phenolic Compounds: Antimicrobial Properties against Yeasts, Lactic Acid and Acetic Acid Bacteria. Beverages 2017, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaiya, M.A.; Odeniyi, M.A. Utilisation of Mangifera indica plant extracts and parts in antimicrobial formulations and as a pharmaceutical excipient: a review. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barata, A.; Caldeira, J.; Botelheiro, R.; Pagliara, D.; Malfeito-Ferreira, M.; et al. Survival patterns of Dekkera bruxellensis in wines and inhibitory effect of sulphur dioxide. Int J Food Microbiol 2008, 121, 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Widsten, P.; Cruz, C.D.; Fletcher, G.C.; Pajak, M.A.; McGhie, T.K. Tannins and Extracts of Fruit By products: Antibacterial Activity against Foodborne Bacteria and Antioxidant Capacity. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2014, 62, 11146–11156. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.K.; Gurjar, P. S.; Beer, K.; Pongener, A.; Ravia, S.C.; Singh, S.; Verma, A.; Singh, A.; Thakure, M.; Tripathyf, S.; Vermaf, D.K. A review on valorization of different byproducts of mango (Mangifera indica L. ) for functional food and human health. Food Biosc. 2022, 48, 101783. [Google Scholar]

- García-Mahecha, M. Bioactive compounds in extracts from the agro-industrial waste of mango. Molecules 2023, 28, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucuk, N.; Primožiˇc, M.; Kotnik, P.; Knez, Ž.; Leitgeb, M. Mango peels as an industrial by-product: a sustainable source of compounds with antioxidant, enzymatic, and antimicrobial activity. Foods 2024, 13, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-León, C.; de Azevedo Ramos, B.; dos Santos Correi, M.T.; Carneiro-da-Cunha, M.G.; Ramirez-Guzman, N., Alves; Ascacio-Valdes, J.; Álvarez-Pérez, O.B.; Aguilar, C.N. Antioxidant and anti-staphylococcal activity of polyphenolic-rich extracts from Ataulfo mango seed. LWT – Food Sci Tech 2021, 148, 111653.

- Abdullah, A.; Saeed Mirghani, M.; Jamal, P. Antibacterial activity of malaysian mango kernel. Afr J Biotechnol 2011, 10, 18739–18748. [Google Scholar]

- Dorta, E.; González, M.; Lobo, M.G.; Laich, F. Antifungal activity of mango peel and seed extracts against clinically pathogenic and food spoilage yeast. Nat Prod Res 2015, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorta, E.; Lobo, M.G.; González, M. Improving the efficiency of antioxidant extraction from mango peel by using microwave-assisted extraction. Plant Food Hum Nutr 2013, 68, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorta, E.; Lobo, M.G.; González, M. Optimization of factors affecting extraction of antioxidants from mango seed. Food Bioproc Tech 2013, 6, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorta, E.; Gonzalez, M.; Lobo, M.G.; Sanchez-Moreno, C.; de Ancos, B. Screening of phenolic compounds in by-product extracts from mangoes (Mangifera indica L. ) by HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS and multivariate analysis for use as a food ingredient. Food Res Int 2014, 57, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- WHO, World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Prestinaci, F.; Pezzotti, P.; Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial resistance: a global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathogens and Global Health 2015, 109, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahurul, M.H.A.; Jahurul, I.S.M.; Ghafoor, Z.K.; Al-Juhaimi, F.Y. Mango (Mangifera indica L. ) by-products and their valuable components: a review. Food Chem 2015, 183, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Parvez, G.M. Pharmacological activities of mango (Mangifera indica): a review. J Pharmacognosy Phytochem 2016, 5, 01–07. [Google Scholar]

- Ediriweera, M.K.; Tennekoon, K.H.; Samarakoon, S.R. A review on ethnopharmacological applications, pharmacological activities and bioactive compounds of Mangifera indica (mango). Evid-Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, A.; Naidoo, Y.; Dewir, Y.H.; Rihan, H. Phytochemical screening and antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Mangifera indica L. Leaves. Hortcf 2022, 8, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzur, A. G.; Junior, S.M.; Morais-Costa, F.; Mariano, E.G.; Careli, R.T.; da Silva, L.M.; Duarte, E.R. Extract of Mangifera indica L. leaves may reduce biofilms of Staphylococcus spp. in stainless steel and teat cup rubbers. Food Sci Technol int 2019, 108201321985852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, C.; Gänzle, M. G.; Schieber, A. Fast LC–MS analysis of gallotannins from mango (Mangifera indica L. ) kernels and effects of methanolysis on their antibacterial activity and iron binding capacity. Food Res Int 2012, 45, 422–426. [Google Scholar]

- Kabuki, T.; Nakajima, H.; Arai, M.; Ueda, S.; Kuwabara, Y.; et al. Characterization of novel antimicrobial compounds from mango (Mangifera indica L. ) kernel seeds. Food Chem 2000, 71, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.R.; Moss, M.O. Food Microbiology, 2nd ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnison, A.F.; Jacobsen, D.W. Sulfite hypersensitivity. A critical review. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1987, 17, 185–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bomhard, E.M.; Brendler-Schwaab, S.Y.; Freyberger, A.; Herbold, B.A.; Leser, K.H.; Richter, M. Ophenylphenol and its sodium and potassium salts: A toxicological assessment. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2002, 32, 551–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oms-Oliu, G.; Rojas-Graü, M.A.; González, L.A.; Varela, P.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Hernando, M.I.H.; Munuera, I.P.; Fiszman, S.; Martín-Belloso, O. Recent approaches using chemical treatments to preserve quality of fresh-cut fruit: A review. Posth. Biol. Technol. 2010, 57, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Cho, A. R.; Han, J. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of leafy green vegetable extracts and their application to meat product preservation. Food Control 2013, 29, 112e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, V. M.; Board, R. G. Future prospects for natural antimicrobial food preservation systems. In V. M. Dillon, & R. G. Board (Eds.), Natural antimicrobial systems and food preservation (pp. 297e303). 1994, Wallingford: CAB International.

- Parke, D. V.; Lewis, D. F. V. Safety aspects of food preservatives. Food Addit. Contam 1992, 9, 561e577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañón, S.; Díaz, P.; Rodríguez, M.; Garrido, M. D.; Price, A. Ascorbate, green tea and grape seed extracts increase the shelf-life of low sulphite beef patties. Meat Scie 2007, 77, 626e633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartowsky, E.J.; Henschke, P.A. Acetic acid bacteria spoilage of bottled red wine - A review. Int J Food Microbiol 2008, 125, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alañón, M.E.; García-Ruíz, A.; Díaz-Maroto, M.C.; Pérez-Coello, MS.; et al. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of pressurized liquid extracts from oenological woods. Food Control, 2015, 50, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorkova, E.; Zakova, T.; Landa, P.; Novakova, J.; Vadlejch, J.; et al. Growth inhibitory effect of grape phenolics against wine spoilage yeasts and acetic acid bacteria. Int J Food Microbiol 2013, 161, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, A.; Cueva, C.; González-Rompinelli, E.M.; Yuste, M.; Torres Martín-Álvarez, J.; et al. Antimicrobial phenolic extracts able to inhibit lactic acid bacteria growth and wine malolactic fermentation. Food Control 2012, 28, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguant, C.; Bordons, A.; Arola, L.; Rozès, N. Influence of phenolic compounds on the physiology of Oenococcusoeni from wine. J Appl Microbiol 2000, 88, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas, N.; Lonvaud-Funel, A.; Glories, Y. Effect of phenolic acids and anthocyanins on growth, viability and malolactic activity of a lactic acid bacterium. Food Microbiol 1997, 14, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, L.; Ascacio, L.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Aguilera-Carbó, A.; Aguilar, C.N. Ellagic acid: Biological properties and biotechnological development for production processes. Afr. J. Biotechnol 2011, 10, 4518–4523. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos, J.L.; Giner, R.M.; Marín, M.; Recio, M.C. A Pharmacological Update of Ellagic Acid. Planta Med 2018, 84, 1068–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA – European Food Safety Authority, The European Union Summary Report on Trends and Sources of Zoonoses, Zoonotic Agents and Food-borne Outbreaks in 2012. The EFSA Journal 2014, 12, 3547.

- Götz, F.; Bannerman, T.; Schleifer, K.H. The Genera Staphylococcus and Macrococcus. In: M Dworkin, S Falkow, E Rosenberg, K-H Schleifer, E Stackebrandt. (Eds.). The Prokaryotes (New York: Springer) 2006, 4, 5–75. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, K.; Heilmann, C.; Peters, G. Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014, 27, 870–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieber, L.; Kahlmeter, G. Staphylococcus lugdunensis in several niches of the normal skin flora. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010, 16, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.M.; Price, L.B.; Hungate, B.A.; Abraham, A.G.; Larsen, L.A.; Christensen, K.; Stegger, M.; Skov, R. ; Andersen, Staphylococcus aureus and the ecology of the nasal microbiome. Sci Adv 2015, 1, e1400216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, H.; Raju, F.; Shaikh, A.Z.; Lin, A.N.; Lin, A.T.; Abboud, J.; Reddy, S. Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis and cerebrovascular accident: a systemic review of risk factors and clinical outcome. Cureus 2018, 10, e2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.Y.; Huang, Y.F.; Tang, C.W.; Chen, Y.Y.; Hsieh, K.S.; Ger, L.P.; Chen, Y.S.; Liu, Y.C. Staphylococcus lugdunensis infective endocarditis: a literature review and analysis of risk factors. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2010, 43, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, K.L.; Del Pozo, J.L.; Patel, R. From clinical microbiology to infection pathogenesis: how daring to be different works for Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2008, 21, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douiri, N.; Hansmann, Y.; Lefebvre, N.; Riegel, P.; Martin, M.; Baldeyrou, M.; Christmann, D.; Prevost, G.; Argemi, X. Staphylococcus lugdunensis: a virulent pathogen causing bone and joint infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016, 22, 747–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argemi, X.; Prevost, G.; Riegel, P.; Keller, D.; Meyer, N.; Baldeyrou, M.; Douiri, N.; Lefebvre, N.; Meghit, K.; Ronde Oustau, C.; Christmann, D.; Cianferani, S.; Strub, J.M.; Hansmann, Y. VISLISI trial, a prospective clinical study allowing identification of a new metalloprotease and putative virulence factor from Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017, 23, 334.e1–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaes Nunes, R.S.; Pires de Souza, C.; Pereira, K.S.; Del Aguila, E.M.; Flosi Paschoalin, V.M. Identification and molecular phylogeny of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolates from Minas Frescal cheese in southeastern Brazil: Superantigenic toxin production and antibiotic resistance. J Dairy Sci 2016, 99, 2641–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiamboonsri, P.; Pithayanukul, P.; Bavovada, R.; Chomnawang, M.T. The inhibitory potential of Thai mango seed kernel extract against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Molec 2011, 16, 6255–6270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Deshmukh, P.; Ravishankerv. Antimicrobial and phytochemical screening of Mangifera indica against skin aliments. J Pure ApplMicrobio 2010, 4, 387–392. [Google Scholar]

- Mirghani, M.E.S.; Yosuf, F.; Kabbashi, N.A.; Vejayan, J.; Yosuf, Z.B.M. Antibacterial activity of mango Kernel extracts. J Appl Sci 2009, 9, 3013–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabuki, T.; Nakajima, H.; Arai, M.; Ueda, S.; Kuwabara, Y.; Dosako, S. Characterization of novel antimicrobial compounds from mango (Mangifera indica L.) kernel seeds. Food Chem. 2001, 71, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F. L.v.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, G.; Huang, G.; et al. Quantification and purification of mangiferin from chinese mango (Mangifera indica L.) cultivars and its protective effect on human umbilical vein endothelial cells under H2O2 induced stress. Int J Mol Sci 2012, 13, 11260–11274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, S.; Sevilla, I.; Betancourt, R.; Romero, A.; Nuevas-Paz, L.; et al. Extraction of mangiferin from Mangifera indica L. leaves using microwave assisted technique. Emir J Food Agr 2014, 26, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Kumar, Y.; Sadish, K.S.; Sharma, V.K.; Dua, K.; et al. Antimicrobial evaluation of mangiferin analogues. Indian J Pharma Sci 2009, 71, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| AceticAcid Bacteria | Peel extracts (mg GAE/mL) | Seed extracts (mg GAE/mL) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPA | SPA | KPA | GPB | SPB | KPB | GSC | SSC | KSC | |||||

| Group I | Acetobacter A. cerevisiae(Ac3-6A2) |

MIC | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 1.7 | 8.3 | 1.7 | 8.3 | 17 | 17 | ||

| MBC | 25 | 25 | 25 | 17 | 25 | 17 | 50 | 50 | 50 | ||||

| A. cerevisiae(Ac5- T5) | MIC | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 1.7 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 17 | 17 | 17 | |||

| MBC | 25 | 25 | 25 | 17 | 25 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 50 | ||||

| A. cerevisiae (Ac2-6A1) | MIC | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 8.3 | 25 | 17 | |||

| MBC | 25 | 25 | 25 | 17 | 25 | 17 | 25 | 50 | 50 | ||||

| A. pasteurianus(Ap16-Lz75) | MIC | 50 | 50 | 25 | 8.3 | 50 | 25 | 17 | 8.3 | 8.3 | |||

| MBC | 100 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 50 | ||||

| A. malorum(Am17-T33) | MIC | 50 | 50 | 50 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 25 | 25 | 100 | |||

| MBC | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 200 | ||||

| A. malorum(Am25-P21) | MIC | 50 | 50 | 50 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 25 | 25 | 100 | |||

| MBC | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 200 | ||||

| A. malorum(Am26-Lz67) | MIC | 50 | 50 | 50 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 25 | 25 | 100 | |||

| MBC | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 200 | ||||

| Group II | A. tropicalis(At1-T191) | MIC | 100 | 200 | 200 | 100 | 200 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 200 | ||

| MBC | 200 | 400 | 400 | 200 | 400 | 200 | 100 | 100 | 400 | ||||

| A. tropicalis(At2-T59) | MIC | 100 | 200 | 200 | 100 | 200 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 200 | |||

| MBC | 200 | 400 | 400 | 200 | 400 | 200 | 100 | 100 | 400 | ||||

| Gluconobacter G. japonicus(Gj1-P37) |

MIC | 100 | 50 | 200 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | |||

| MBC | 200 | 100 | 400 | 200 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| G. japonicus(Gj3-Lz59) | MIC | 100 | 50 | 200 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | |||

| MBC | 200 | 100 | 400 | 200 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| G. japonicus(Gj2-P92) | MIC | 100 | 100 | 200 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | |||

| MBC | 200 | 200 | 400 | 200 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 200 | 100 | ||||

| Gluconacetobacter G. saccharivorans(Gs1-T80) |

MIC | R* | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | |||

| MBC | R* | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | ||||

| Species | Isolate code | Flavonoids | Xanthones | Gallates gallotannins |

Ellagic acid derivatives |

Total phenol compounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetobacter | ||||||

| A. cerevisiae | Ac3-6A2 | -0,4518 | 0,3708 | -0,5809 | 0,5809 | -0,5164 |

| A. cerevisiae | Ac5-T5 | -0,8385* | 0,2725 | -0,7267* | 0,5404 | -0,8385* |

| A. cerevisiae | Ac2-6A1 | -0,4433 | 0,4445 | -0,7714* | 0,4699 | -0,5497 |

| A. pasteurianus | Ap16-Lz75 | 0,5285 | -0,5339 | 0,4766 | 0,0693 | 0,5632 |

| A. malorum | Am17-T33 | 0,0559 | 0 | 0,3354 | -0,4099 | -0,0745 |

| A. malorum | Am25-P21 | 0,0559 | 0 | 0,3354 | -0,4099 | -0,0745 |

| A. malorum | Am26-Lz67 | 0,0559 | 0 | 0,3354 | -0,4099 | -0,0745 |

| A. tropicalis | At1-T191 | 0,2673 | -0,2745 | 0,5612 | -0,3742 | 0,1604 |

| A. tropicalis | At2-T59 | 0,2673 | -0,2745 | 0,5612 | -0,3742 | 0,1604 |

| Gluconobacter | ||||||

| G. japonicus | Gj1-P37 | 0,5578 | 0,13 | 0,2191 | -0,1594 | 0,5578 |

| G. japonicus | Gj3-Lz59 | 0,5578 | 0,13 | 0,2191 | -0,1594 | 0,5578 |

| G. japonicus | Gj2-P92 | 0,4781 | -0,2445 | 0,1394 | 0 | 0,3984 |

| Staphylococcus | ||||||

| S. arlettae | NRRL B-14764 | 0,414 | -0,1622 | -0,1035 | 0,6211 | 0,5175 |

| S. equorum subsp. equorum | NRRL B-14765 | 0,414 | -0,1622 | -0,1035 | 0,6211 | 0,5175 |

| S. carnosus subsp. carnosus | NRRL B-14760 | 0,1369 | 0,3575 | -0,4108 | 0,5477 | 0,1369 |

| S. xylosus | NRRL B-14776 | 0,1369 | 0,3575 | -0,4108 | 0,5477 | 0,1369 |

| S. sciuri subsp. sciuri | NRRL B-14767 | 0,1369 | 0,3575 | -0,4108 | 0,5477 | 0,1369 |

| S. gallinarum | NRRL B-14763 | 0,3651 | 0,0953 | -0,2739 | 0,5477 | 0,4564 |

| S. cohnii subsp. cohnii | NRRL B-14756 | 0,6739 | -0,4167 | 0,7625* | -0,5763 | 0,6739 |

| S. lugdunensis | 99705-65 | -0,0791 | -0,2615 | 0,4480 | -0,4216 | -0,0264 |

| S. aureus | 11923-76 | 0,4099 | -0,0973 | 0,4845 | -0,5963 | 0,4099 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ATCC 27853 | -0,8216* | 0,4767 | -0,8216* | 0,4564 | -0,8216* |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | ATCC 13883 | -0,2739 | 0,286 | -0,7303* | 0,4564 | -0,3651 |

| Staphylococcus species | Peel extracts (mg GAE/mL) |

Seed extracts (mg GAE/mL) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPA | SPA | KPA | GPA | SPA | KPA | GSC | SSC | KSC | |||||

| Group I |

S. arlettae NRRL B-14764 |

MIC | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | ||

| MBC | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | ||||

|

S. equorum subsp. equorum NRRL B-14765 |

MIC | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | |||

| MBC | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | ||||

|

S. carnosus subsp. carnosus NRRL B-14760 |

MIC | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |||

| MBC | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 5 | ||||

|

S. xylosus NRRL B-14776 |

MIC | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |||

| MBC | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | ||||

|

S. sciuri subsp. sciuri NRRL B-14767 |

MIC | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |||

| MBC | 30 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 15 | 15 | 120 | 120 | 120 | ||||

|

S. chromogenes NRRL B-14759 |

MIC | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |||

| MBC | 5 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 5 | ||||

| Group II |

S. gallinarum NRRL B-14763 |

MIC | 10 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 5 | ||

| MBC | 30 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 10 | 240 | 240 | 240 | ||||

|

S. aureus subsp. aureus NRRL B-767 |

MIC | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |||

| MBC | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | ||||

|

S. aureus 11923-76 |

MIC | 30 | 10 | 30 | 30 | 10 | 120 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |||

| MBC | 60 | 15 | 60 | 60 | 15 | 240 | 30 | 15 | 15 | ||||

|

S. cohnii subsp. cohnii NRRL B-14756 |

MIC | 15 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 60 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |||

| MBC | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | ||||

|

S. lugdunensis 99705-65 |

MIC | 30 | 60 | 30 | 120 | 120 | 240 | 60 | 60 | 60 | |||

| MBC | 120 | >240 | 120 | 240 | 240 | >240 | 120 | 120 | 120 | ||||

| Species | Peel extracts (mg GAE/mL) |

Seed extracts (mg GAE/mL) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPA | SPA | KPA | GPB | SPB | KPB | GSC | SSC | KSC | |||||

|

Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 |

MIC | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 30 | 30 | |||

| MBC | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 60 | 60 | 30 | ||||

|

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 |

MIC | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | |||

| MBC | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | ||||

|

Shigella dysenteriae ATCC 13313 |

MIC | 120 | 120 | 120 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 120 | 120 | 120 | |||

| MBC | >240 | >240 | >240 | >240 | >240 | >240 | >240 | >240 | >240 | ||||

|

Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883 |

MIC | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | |||

| MBC | >240 | >240 | >240 | >240 | >240 | >240 | >240 | >240 | >240 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).