1. Introduction

Invasive insect species impose profound ecological and economic burdens across the globe [

1,

2,

3] with annual costs attributed to these pests estimated at US

$70 billion [

4,

5,

6]. Among the most destructive invaders are fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae), a family encompassing over 5,000 species [

7,

8,

9], of which approximately 200 hold significant economic importance [

9]. Over 250 tephritid species are now classified as potential quarantine threats to the European Union [

7], while Australia, China, New Zealand, Africa, South America, Asia, and North America similarly prioritise these insects among their top-regulated pests [

10,

11]. Fruit flies inflict devastating crop losses, often exceeding 80% in fruit-producing regions [

12], and remain a critical barrier to horticultural trade and productivity, demanding urgent attention from policymakers and agricultural managers [

13].

The Baluchistan melon fly,

Myiopardalis pardalina (Bigot, 1891), exemplifies this threat. As a highly invasive tephritid pest, it jeopardises global cucurbit production—a cornerstone of both local livelihoods and international markets. Melon (

Cucumis melo), a key Cucurbitaceae crop cultivated in 105 countries, spans 1.1 million hectares worldwide, yielding 28.5 million tonnes annually [

14,

15]. Asia dominates production, contributing 75% of cultivated land and 83% of output [

16]. Alongside watermelon (

Citrullus lanatus), cucumber (

C.

sativus), and pumpkin (

Cucurbita maxima), melons underpin diets and economies in warm regions [

17,

18], rendering them acutely vulnerable to

M.

pardalina.

Infestations by this oligophagous pest trigger crop losses of 15–90%, with severe outbreaks annihilating entire harvests [

19,

20,

21]. Such losses destabilise supply chains, inflate consumer prices, and imperil food security in regions reliant on cucurbits for nutrition and income. Compounding these challenges,

M.

pardalina’s capacity to overwinter in sub-zero temperatures [

22] and its expanding range—fueled by trade or natural dispersal into North America and Southern Europe [

23]—intensify risks. Conventional insecticides often fail against its internal-feeding larvae, underscoring the need for innovative, integrated management strategies.

Despite its destructive potential, M. pardalina has received relatively scant attention to date. This review synthesises current knowledge on the species’ biology, ecology, and control methods, evaluating cultural, chemical, biological, and genetic interventions. By addressing critical research gaps, we aim to equip researchers, policymakers, and agricultural practitioners with insights to develop sustainable solutions. Protecting cucurbit crops from M. pardalina is not solely an agricultural priority but a vital step in safeguarding rural economies, cultural traditions, and global food security amid escalating environmental and economic uncertainties.

2. Systematic Literature Review

The Baluchistan melon fly

M.

pardalina, belongs to the kingdom Animalia, phylum Arthropoda, class Insecta, order Diptera, and family Tephritidae. The genus

Carpomya is a synonym of

Myiopardalis [

24], which explains the dual nomenclature of “

Myiopardalis pardalina” and “

Carpomya pardalina” in literature. To conduct a comprehensive review, we performed a systematic search using the search string (Carpomya OR Myiopardalis) AND (pardalina) on

Scopus, targeting titles, keywords, and abstracts, which yielded 13 relevant papers. In parallel, an advanced search on

Google Scholar was executed by entering “pardalina” in the “with all the words” field and “Carpomya Myiopardalis” in the “with at least one of the words” field, with results filtered to include occurrences anywhere in the articles. This search returned 206 papers. After removing duplicates and evaluating relevance, 98 unique and pertinent papers were retained for analysis.

The use of

Scopus and

Google Scholar was international, as these platforms complement each other in scope.

Scopus primarily indexes peer-reviewed academic articles from commercial publishers, whereas

Google Scholar encompasses a broader range of sources, including both academic and grey literature. Grey literature—defined as information produced and distributed by governmental, academic, business, and industrial entities outside traditional commercial publishing channels—has gained recognition for its value in systematic reviews and meta-analyses [

25,

26]. By incorporating grey literature, our review captures recent and interdisciplinary research on

M.

pardalina that may not yet be indexed in commercial databases, ensuring a more thorough and current synthesis of knowledge.

3. Overview of the Baluchistan Melon Fly

3.1. Morphological Characteristics

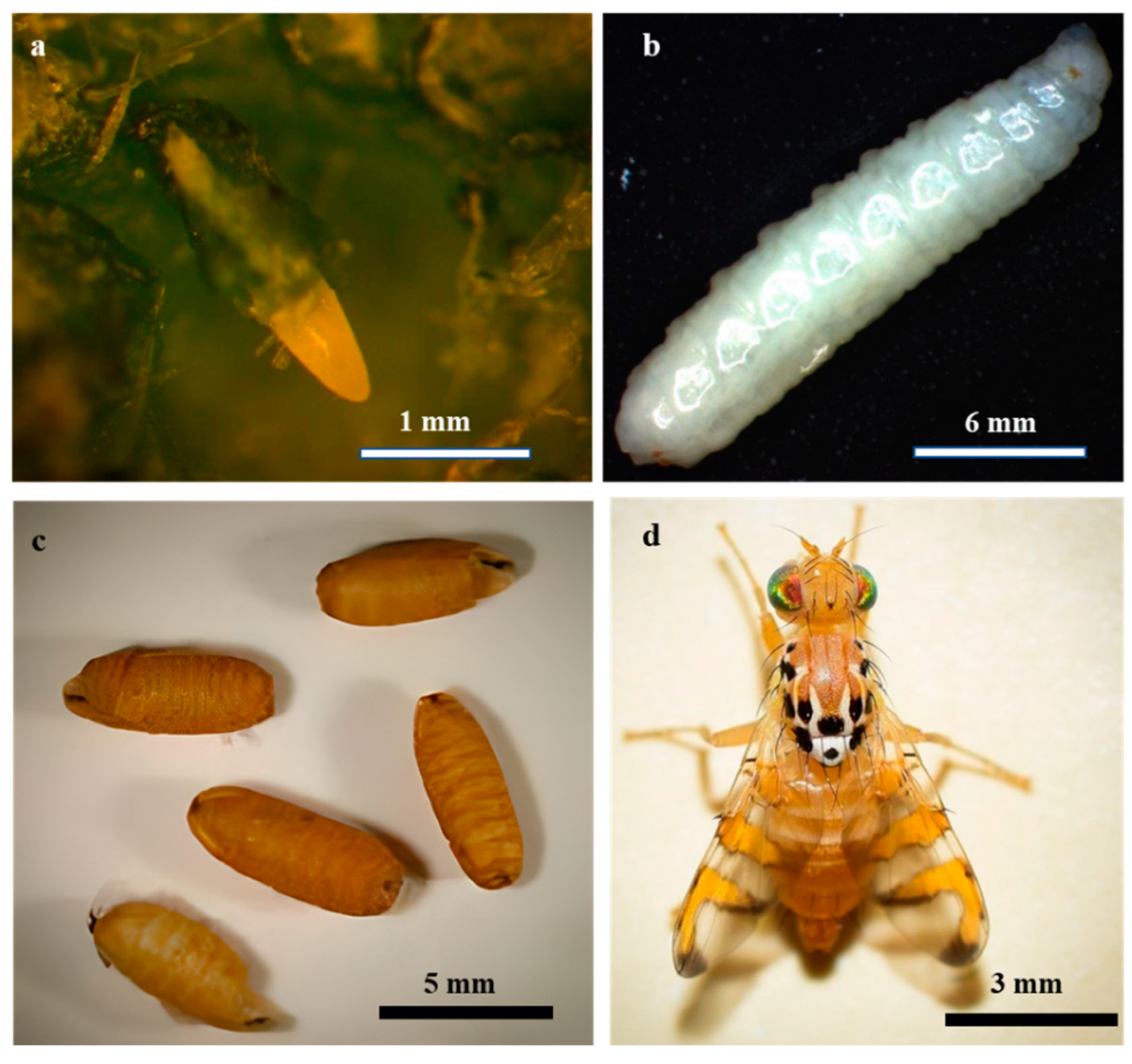

The life stages of

M.

pardalina exhibit distinct morphological traits (

Figure 1). Eggs are elliptical, glossy white, and measure 1.2 × 2.0 mm (

Figure 1a). Larvae, reaching approximately 10 mm in length, are cream-white and apodous [

27] (

Figure 1b). Pupation yields coarctate, brown pupae averaging 7.2 mm in length [

27,

28,

29] (

Figure 1c). Adults exhibit sexual dimorphism: Males possess a body length of 5.0–6.4 mm with wings spanning 4.0–4.6 mm, whereas females are larger, measuring 6.3–7.3 mm in body length with wings extending 4.5–5.3 mm [

30] (

Figure 1d).

The head is dark yellow, broader than long, and lacks facial spots or silvery markings on the frons and para-frons. A flat or convex face features distinct antennal grooves and tubercles, accompanied by elongated compound eyes. Antennae are shorter than the facial length, paired with a short, capitate proboscis. The mesonotum ranges from light yellow to brown, adorned with five black lateral spots and a central black spot at the posterior basal margin. The scutellum is light yellow, bearing a small medial black dot on its disc. Legs are unmarked by dark femoral maculations. The abdomen, yellow to orange-brown, comprises separate tergites; tergites III–V lack dark median longitudinal stripes, and tergite V is devoid of glandular spots. Males lack dark setae on tergite III, while females exhibit an exposed tergite VI equal in length to tergite V [

31].

Wings are light yellow with banding patterns akin to

Rhagoletis, featuring basal, median, and pre-apical crossbands that extend to the posterior margin. The pre-apical crossband is partially or fully detached from vein C, with a hyaline region distally in cell

R2+3. Vein

R2+3 is straight, terminating in a distinct, anteriorly inclined spur. The radio-medial crossvein intersects the discal medial cell near its midpoint. The basal medial cell is narrow and triangular, 2.5–3 times longer than wide, matching the width of cell Cup. An anal streak is absent or incomplete. Male terminalia include an elongated tergite IX lobe posteriorly, surstyli exceeding half its length, and a narrower posterior lobe in lateral view. The female ovipositor tapers to a flattened, needle-like apex lacking serrations, accompanied by three sclerotised spermathecae [

27,

31,

32].

3.2. Geographic Distribution and Spread

The Baluchistan melon fly exhibits a wide geographic distribution across Africa, Asia, and Europe, with a documented presence in over 20 countries, including Sudan, Egypt, Afghanistan, China, India, Iran, Kazakhstan, Turkey, and Russia (

Table 1). Regional prevalence varies: the pest is widespread in Iran and Turkey, whereas in China and Israel, detections are largely limited to interceptions or sporadic occurrences.

First described in the Baluchistan region—spanning southeastern Iran to western Pakistan, where it remains a major agricultural threat—

M.

pardalina has expanded aggressively since the 1990s. Severe outbreaks in Afghanistan catalysed its spread across Central Asia, including Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan [

19]. Its presence extends to additional countries in Asia and Europe—such as Georgia, Lebanon, Syria, Armenia, and Jordan—and in Africa, notably Sudan (

Table 1). Classified as a quarantine pest by the EU, Egypt, China, the United States, Kazakhstan, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Ecuador, Indonesia, Japan, Peru, Thailand, and New Zealand [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36],

M.

pardalina faces stringent import controls in non-endemic regions to curb its introduction.

A key factor amplifying its invasive potential is its ability to overwinter as pupae in sub-zero, snow-prone environments [

19,

22,

37], posing significant risks to temperate cucurbit-growing zones such as North America and Southern Europe. Dispersal is primarily mediated through the movement of infested fruits harbouring larvae or pupae [

37,

38]. Although currently confined to Central Asia and parts of Eastern Europe, MaxEnt models project its potential global establishment under current and future climatic conditions [

23]. While invasion pathways into the Americas and Oceania remain unclear, Europe and China face direct risks due to extensive host availability [

23]. The pest’s accelerating range expansion highlights the critical need for enhanced phytosanitary protocols and cross-border cooperation to safeguard uninfested regions. Proactive monitoring, public awareness campaigns, and international data-sharing frameworks are essential to mitigate further spread.

3.3. Host Range and Life Cycle

The Baluchistan melon fly is an oligophagous specialising in cucurbitaceous plants, infesting both cultivated and wild species. Primary cultivated hosts include melon (

C.

melo), with significant infestations also reported in watermelon (

C.

lanatus), cucumber (

C.

sativus), snake melon (

C.

melo var.

flexuosus), and giant pumpkin (

C.

maxima) [

29,

32,

79,

80]. Wild hosts include

C.

trigonus and

Ecballium elaterium [

23,

38], underscoring the pest’s adaptability to diverse ecological niches.

The life cycle of

M.

pardalina encompasses four stages: Egg, larva, pupa, and adult, with the pupal stage acting as the overwintering phase [

37,

53]. Pupae typically reside in the soil at depths of 1–2 cm to 15–16 cm, surviving under snow cover and temperatures just below freezing [

19,

37,

44]. Adults emerge synchronously with the melon flowering season, typically from mid-May to early June in the eastern Mediterranean [

19,

38,

44]. Both sexes are polygamous, mating repeatedly post-emergence [

52]. Females oviposit at least 100 eggs beneath the epidermis of developing fruits; upon hatching, larvae immediately tunnel into the pulp to feed [

37,

44]. After completing development, mature larvae exit the fruit and pupate in the soil, where they overwinter. The overwintering pupal stage presents a critical target for control measures, as interventions during this phase can significantly suppress populations in subsequent generations [

32,

70].

Developmental duration varies with temperature: Under summer conditions, eggs hatch in 2–3 days, larvae mature in 8–18 days, and pupae develop in 13–20 days, completing the life cycle within approximately 30 days. This rapid progression facilitates two to three overlapping generations annually, with up to four generations reported in Iran and Israel (

Table 2).

3.4. Symptoms of Infestation and Damage Caused

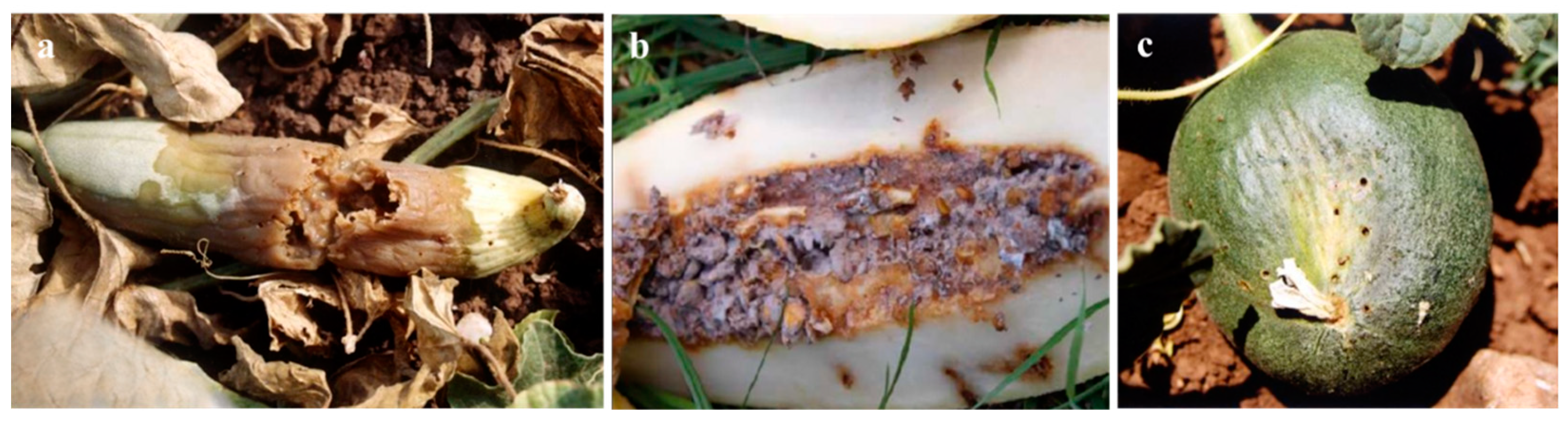

Infestation by

M.

pardalina larvae cause catastrophic damage to cucurbit fruits (

Figure 2). Internal larval feeding triggers rapid tissue decay, leading to fruit rot, foul odours, and premature decomposition [

37,

38,

73,

84] (

Figure 2a,b). Mature larvae exit fruits through visible holes to pupate in soil, further compromising structural integrity and rendering produce unmarketable and inedible [

80] (

Figure 2c).

Economic losses vary regionally but consistently threaten agricultural stability. In Israel, melon losses reach 85–90%, with watermelons suffering 60% damage [

85]. Turkmenistan reports 56.7% losses in melons, alongside declines of 2.8% in watermelon, 1.1% in pumpkin, and 0.1% in cucumber, with the pest’s spread causing an 80–90% decline in melon yields [

19]. Armenia documents melon losses of 6.7–34.5% [

86], while Afghanistan faces 30–40% losses in unprotected melons and <5% in cucumber and watermelon [

19]. In Kazakhstan’s Kyzylorda region, infestations affect 50% of farms, with losses ranging from 10% to 25%, escalating to total crop failure in severe cases [

21].

Severe outbreaks see females ovipositing in unopened flowers, enabling larvae to tunnel into stems and leaf stalks before fruit formation [

19,

37,

84]. This internal feeding behaviour renders surface-applied contact insecticides ineffective, necessitating systemic pesticides or strategies targeting vulnerable life stages (e.g., overwintering pupae or emerging adults). Such approaches are critical to disrupt the pest’s lifecycle and mitigate its compounding economic and agricultural impacts.

4. Control

4.1. Monitoring and Quarantine

Effective monitoring and quarantine measures are essential for managing the spread of

M.

pardalina. Advanced molecular detection techniques have been developed to improve detection accuracy. For example, Jiang et al. (2024) [

87] introduced a visualised Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) method, which identifies

M.

pardalina through a simple colour-change reaction, making it viable even in resource-limited settings. Complementing this, Rao et al. (2024) [

88] developed a Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA)-CRISPR/Cas12a detection kit, enabling rapid, on-site identification with high specificity and sensitivity at constant temperatures (37–42°C), without requiring complex equipment. Additionally, the 2024 sequencing and analysis of the

M.

pardalina mitochondrial genome have provided critical insights into species diagnosis, evolutionary biology, and potential targets for control strategies [

18]. This genomic data supports precise diagnostics for early detection and informs innovative control methods, such as targeting genes linked to insecticide resistance or pheromone reception.

Regarding quarantine measures, physical controls such as ionising radiation (e.g., a 65 Gy sterilisation dose, which balances male survival and female sterility [

22] and temperature manipulation show promise. However, further research into the pest’s thermal biology is required to optimise quarantine protocols [

89].

4.2. Cultural Control

Cultural and physical methods aim to disrupt

M.

pardalina infestations by modifying environmental conditions. Adults favour shaded areas, such as foliage or plant bases, during peak heat [

17]; maintaining weed-free fields with ample sunlight and airflow can deter pest activity. In dense plantings, repositioning fruits to sunlit areas and trimming excess foliage during early fruiting enhances canopy light penetration [

19]. Proper disposal of infested fruits—critical to breaking population cycles—traditionally involves burial at 1 m depth with lime, though research suggests depths exceeding 50 cm may be necessary to ensure adult mortality [

38]. Additional strategies include: Crop rotation and early planting to disrupt pest life cycles; bagging young fruits to block oviposition—for instance, in Pakistan, bagging melons to protect against

M.

pardalina increased production from 2,500 to 40,000 units [

85]; post-harvest management, such as removing plant residues, pruning vines, and thinning fruits to an optimal density [

19,

20,

42,

44,

51]. While eco-friendly, these methods face limitations under high pest pressure or in shallow-ploughed soils and may require labour-intensive implementation.

4.3. Chemical Control

Chemical insecticides remain a cornerstone of

M.

pardalina management. Early Soviet studies demonstrated efficacy with 0.25% Zitan-85 combined with Trichlorphon or Carbaryl, though repellent formulations (e.g., Phosalone, Dimethoate and Endosulfan) proved less effective [

43]. Field trials found that straight-spray or bait-spray applications of Tamaron and E.P.N. (600 and 810 g a.i./ha every 10 days) provided superior control against larvae, followed by Padan, Sumicidin, and Dimilan, while granular applications of Thimet and Fundal (1800 and 900 g a.i./ha) outperformed Miral, Marshal, and Dacamax [

62]. Laboratory experiments identified Apholate (0.1%) and Thiotepa (0.05%) as effective options [

71]. In Pakistan, localised Endosulfan (3 ml/L water) or bait sprays (protein hydrolysate + Diptrex™ 80SP) applied to the 5-meter periphery of melon fields reduced infestations and increased yields [

63]. Similarly, in Iran, Phosalone at 35%, Trichlorfon at 80%, and Fenvalerate at 20% reduced

M.

pardalina populations effectively [

53]. In Afghanistan, Deltamethrin lowered infestation rates, and spot applications of carbaryl dust at removal sites of infested melons effectively targeted emerging adults [

19]. A 2014 study in Badghis, Afghanistan, showed that combining insecticides (e.g., Diazinon, Monitor, Danadium, Laser, Confidor) with pupae removal and fruit bagging further reduced fly numbers and fruit damage [

28]. In Kazakhstan, sequential applications of Thiamethoxam/Cyhalothrin followed by Chlorpyrifos/Cypermethrin sustained population control and improved fruit quality for 14 days [

21]. Further research in the region demonstrated that a specific treatment regimen—applying Enjio 247 SC (Thiamethoxam, 141 g/L + Lambda-Cyhalothrin, 106 g/L) at 0.25 L/ha at the end of melon flowering, followed by Nurelle D, C.E. (Chlorpyrifos, 500 g/L + Cypermethrin, 50 g/L) at 0.7 L/ha during fruit formation, and a second application of Enjio 247 SC at 0.25 L/ha during the mass emergence of the second generation of melon flies—reduced melon fruit infection by 89.0-91.3% [

22]. Additionally, applying Nurelle D, C.E. at 0.7 L/ha during the same period decreased damage by 83.9-90.4%, and the yield of healthy fruits increased by 80.2-77.5 c/ha [

22]. In the Khorezm region, the effectiveness of Belmak 5% em.k., Detsis 2.5% em.k., and Tsipi 25% em.k. against M. pardalina was examined, with all treatments showing biological efficacy over 80%, and Belmak 5% em.k. demonstrating the best results [

90]. Despite efficacy, rising resistance and environmental concerns drive demand for sustainable alternatives.

4.4. Biological Control

Biological control may provide a sustainable approach to managing

M.

pardalina, with several promising methods under investigation. The sterile insect technique (SIT), which involves releasing sterile males to suppress fertile offspring, has been tested but is limited by the fly’s multiple mating behaviour, though sex attractants showed promise [

52]. Traditional fruit fly lures, such as Cue-lure, Methyl Eugenol, have proven ineffective in regions like Turkey and Afghanistan [

19,

28]. In contrast, monitoring techniques in Kazakhstan—including pheromone traps (with unspecified chemical composition), yellow sticky traps, and feeding traps baited with melon juice syrup and sugar—have shown promise for

M.

pardalina surveillance [

21]. Similarly, in Herat, Afghanistan a bait made from boiled beef, cucumber extract, and urea has proven effective [

41]. Tests of various baits (melon fruit, sugars, and proteins—revealed that only melon fruit consistently attracts

M.

pardalina [

19]. Recent research has pinpointed species-specific attractants: in Uzbekistan, 4-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-butanone and 1,4-benzyl dicarboxylate have been isolated for effective male traps [

70], while a synthesised food attractant, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester of 1,4-benzene dicarboxylic acid, has enhanced monitoring efforts [

29]. Additionally, laboratory trials with the entomopathogenic nematode

Heterorhabditis bacteriophora have demonstrated efficacy against

M.

pardalina pupae [

77], suggesting potential for future field applications. These advancements highlight the potential of biological control, yet further research is needed to refine and integrate these methods into comprehensive pest management strategies for

M.

pardalina.

4.5. Host Resistance

Host plant resistance is an important component in integrated pest management programs. Research shows that cucurbit susceptibility to

M.

pardalina often correlates with physical traits, particularly thinner skins, which are more easily penetrated by the fly’s ovipositor, resulting in greater damage [

38]. By leveraging genomic insights, breeders can target specific traits, such as skin thickness or other resistance mechanisms, to develop melon cultivars less vulnerable to

M.

pardalina and other pests or diseases [

75]. In Kazakhstan, for example, ongoing breeding programs are focused on developing resistant melon varieties [

21]. In Iran’s Sistan region, the Sefidak and Firoozi99 melon cultivars exhibited the lowest pest damage (18–20%), with longer fruiting periods associated with reduced infestation, although skin thickness showed no significant effect in this case. These cultivars are now recommended for pest-resistant planting strategies [

91]. Similarly, in Şükurlu, Turkey, four melon varieties—Balhan, Balözü, VT21B, and the local ‘Winter melon’ genotype ‘VN2136’—were assessed for damage by

M.

pardalina. All displayed damage rates below 10%, with no notable differences among them, indicating potential inherent resistance [

76]. If successfully developed and widely adopted, these genetically resistant varieties could provide sustainable, long-term protection against

M.

pardalina infestations, reducing reliance on continuous pest control measures and mitigating economic losses [

19,

86].

5. Discussion

Our review strongly suggests that the Baluchistan melon fly, poses a rapidly intensifying threat to cucurbit production in Central Asia, the Middle East, and beyond, with profound implications for agricultural economies and global food security. Capable of devastating up to 90% of yields during outbreaks, M. pardalina imposes substantial economic burdens in regions where cucurbits serve as critical cash crops. Its resilience—evidenced by sub-zero overwintering capacity and oligophagous host specificity—coupled with climate-driven range expansion and global trade networks, magnifies the urgency for coordinated action. Unmitigated, this pest risks invading temperate cucurbit-growing zones such as North America and Southern Europe, endangering livelihoods and disrupting international supply chains. Addressing this challenge demands an integrated approach, combining advances in pest biology, innovative control technologies, and transnational policy frameworks to preempt further spread.

Approximately two-thirds of the information synthesised in our review originated from grey literature including governmental and regional institutional reports. This reliance reflects the pest’s current concentration in Central Asia and the Middle East, where local agricultural agencies prioritise

M.

pardalina as an emerging threat. While grey literature offers critical insights into regional priorities and practical challenges [

26], its dominance highlights a stark disparity: The pest remains understudied in high-impact, peer-reviewed international journals. This asymmetry likely stems from

M.

pardalina’s limited establishment in larger economies with robust research infrastructures, reducing incentives for global scientific engagement. Compounding this issue, financial and institutional constraints in Central Asian and Middle Eastern nations may hinder researchers’ capacity to publish in international forums, inadvertently obscuring the scale of the problem.

The scarcity of peer-reviewed studies on

M.

pardalina in global literature signals a broader neglect of pests endemic to developing agricultural systems, despite their potential for cross-border proliferation. Given the pest’s capacity to inflict severe economic losses and modelling projections of its global establishment under climate change [

23], this research gap demands urgent redress. Strengthening collaborations between affected regions and international agronomic institutions is imperative to bridge knowledge divides, allocate resources equitably, and develop scalable solutions. Prioritising M.

pardalina in global pest surveillance frameworks and funding initiatives will not only mitigate regional vulnerabilities but also preempt future crises as trade and climate patterns evolve.

Future efforts must prioritise a holistic integrated pest management (IPM) framework for M.

pardalina, combining cultural, chemical, biological, and genetic strategies. Cultural tactics, such as optimising planting schedules and field layouts to disrupt the pest’s life cycle through enhanced sunlight exposure and airflow, require systematic evaluation. With the phasing out of broad-spectrum insecticides [

89,

92], chemical control must evolve beyond traditional neurotoxins—where resistance is escalating—towards precision technologies like drone-targeted applications [

93], bioinformatics-driven compound discovery [

94], and AI-enabled monitoring systems [

95]. While parasitoids, entomopathogens, and nematodes are widely used against other fruit flies [

96],

M.

pardalina’s known natural enemies remain limited to three ant species (

Cataglyphis bicolor,

C.

megalocola, and

Pheidole pallidula) that prey on larvae [

83]; their field efficacy, however, remains unquantified. Although

H.

bacteriophora achieved 80% pupal mortality in laboratory trials [

77], its field applicability demands validation. Expanding biocontrol exploration to include parasitoid wasps and fungi is critical. Concurrently, refining attractants—such as pheromonal and food attractants [

21,

29,

70]—requires deeper insights into the pest’s chemical ecology to improve scalability [

97,

98,

99,

100]. Genomic advances, including CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing [

101] and RNA interference [

102] informed by mitochondrial sequencing [

18], could disrupt pest reproduction or accelerate resistant crop development. Climate modelling to predict range expansion under warming scenarios will further enable pre-emptive containment strategies.

Policymakers must act decisively to translate research into actionable measures, preventing M. pardalina from becoming a global crisis. Governments should allocate targeted funding for interdisciplinary projects that bridge laboratory innovations with on-farm solutions, offering subsidies or certification schemes to incentivise adoption of resistant cultivars and IPM practices. International bodies, including the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation (EPPO) and the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), must standardise quarantine protocols, facilitate germplasm exchange, and coordinate transnational monitoring. Equally vital is bolstering agricultural extension services to train farmers—particularly smallholders—in IPM techniques, ensuring access to tools like pheromone traps and climate-resilient seeds. By uniting researchers, policymakers, and farming communities through structured collaboration, nations can mitigate economic losses, protect food security, and build long-term resilience against this escalating threat.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L., W.G. and J.D.; methodology, J.L., M.G., W.G. and J.D.; investigation, J.L., Y.X., M.G., K.F., X.D., S.Y., and X.G.; original draft preparation, J.L., Y.X., S.Y. and X.G.; writing—review and editing, J.L., Y.X., M.G., K.F., X.D., W.G. and J.D.; funding acquisition, W.G. and J.D.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Major Science and Technology Projects in Xinjiang, China (2023A02006).

Data Availability Statement

This study is a review article; no original datasets were generated, analysed, or otherwise used in its preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ullah, F.; Zhang, Y.; Gul, H.; Hafeez, M.; Desneux, N.; Qin, Y. Potential economic impact of Bactrocera dorsalis on Chinese citrus based on simulated geographical distribution with MaxEnt and CLIMEX models. Entomol. Gen. 2023, 43, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, J.; Ota, N.; Goergen, G.; Fagbohoun, J.R.; Tepa-Yotto, G.T.; Kriticos, D.J. Spodoptera eridania: Current and emerging crop threats from another invasive, pesticide-resistant moth. Entomol. Gen. 2022, 42, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Feng, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, Z. Modeling the potential climatic suitability and expansion risk of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick, 1917) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) under future climate scenarios. Insects 2025, 16, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C.J.; Leroy, B.; Bellard, C.; Roiz, D.; Albert, C.; Fournier, A.; Barbet-Massin, M.; Salles, J.-M.; Simard, F.; Courchamp, F. Massive yet grossly underestimated global costs of invasive insects. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diagne, C.; Leroy, B.; Vaissière, A.-C.; Gozlan, R.E.; Roiz, D.; Jarić, I.; Salles, J.-M.; Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Courchamp, F. High and rising economic costs of biological invasions worldwide. Nature 2021, 592, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Zhang, Y.; Gul, H.; Hafeez, M.; Desneux, N.; Qin, Y.; Li, Z. Estimation of the potential geographical distribution of invasive peach fruit fly under climate change by integrated ecological niche models. CABI A&B 2023, 4, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA PLH; Bragard, C. ; Dehnen-Schmutz, K.; Di Serio, F.; Gonthier, P.; Jacques, M.-A.; Jaques Miret, J.A.; Justesen, A.F.; Magnusson, C.S.; Milonas, P.; et al. Pest categorisation of non-EU Tephritidae. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e05931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, T.; Blagoderov, V.; Mostovski, M.B. Order Diptera Linnaeus (1758). Zootaxa 2011, 3148, 222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, N.T.; De Meyer, M.; Terblanche, J.S.; Kriticos, D.J. Fruit flies: Challenges and opportunities to stem the tide of global invasions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2024, 69, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C.J.; Hoskins, A.J.; Haubrock, P.J.; Cuthbert, R.N.; Diagne, C.; Leroy, B.; Andrews, L.; Page, B.; Cassey, P.; Sheppard, A.W. Detailed assessment of the reported economic costs of invasive species in Australia. NeoBiota 2021, 67, 511–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, F.; Ma, X.; Fang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Q. Review on prevention and control techniques of Tephritidae invasion. Plant Quar. 2013, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrichs, J.; Vera, T.; de Meyer, M.; Clarke, A. Resolving cryptic species complexes of major tephritid pests. ZooKeys 2015, 540, 5–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekesi, S.; De Meyer, M.; Mohamed, S.A.; Virgilio, M.; Borgemeister, C. Taxonomy, ecology, and management of native and exotic fruit fly species in Africa. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2016, 61, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, H.S.; Amar, Z.; Lev, E. Medieval emergence of sweet melons, Cucumis melo (Cucurbitaceae). Ann. Bot. 2012, 110, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization Statistics, 2022, accessed 2022 Jun 22. Available online: https://www.faostat.fao.org/site/567/default.

- Benkebboura, A.; Zoubi, B.; Akachoud, O.; Ghoulam, C.; Qaddoury, A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improves yield and quality attributes of melon fruit grown under greenhouse. N.Z. J. Crop Hort. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M. Economic insect pests and phytophagous mites associated with melon crops in Afghanistan. Trop. Pest Manag. 1987, 33, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, H.; Fu, K.; Ding, X.; Deng, J.; Guo, W.; Rao, Q. First report of the complete mitochondrial genome of Carpomya pardalina (Bigot) (Diptera: Tephritidae) and phylogenetic relationships with other Tephritidae. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonehouse, J.; Sadeed, S.M.; Harvey, A.; Haiderzada, G.S. Myiopardalis pardalina in Afghanistan from basic to applied knowledge. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Fruit Flies of Economic Importance, Salvador, Brazil, 1–12. https://inis.iaea.org/records/0f3pf-kds76/files/42109308.pdf; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- EPPO. Mini data sheet on Myiopardalis pardalina (Diptera: Tephritidae). EPPO Global Database, 2020. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/download/doc/1434_minids_CARYPA.

- Toyzhigitova, B.; Yskak, S.; Łozowicka, B.; Kaczyński, P.; Dinasilov, A.; Zhunisbay, R.; Wołejko, E. Biological and chemical protection of melon crops against Myiopardalis pardalina Bigot. J. Plant. Dis. Protect. 2019, 126, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyzhigitova, B.B.; Yskak, S.; Dinasilov, A.S.; Kochinski, P.; Ershin, Z.R.; Raimbekova, B.; Zhunussova, A. Quarantine protective measures against the melon flies (Myiopardalis pardalina Big.) in Kazakhstan. OJBS 2017, 17, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Clarke, A.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Z. Including host availability and climate change impacts on the global risk area of Carpomya pardalina (Diptera: Tephritidae). Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 724441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrbom, A. The genus Carpomya Costa (Diptera: Tephritidae): New synonymy, description of first American species, and phylogenetic analysis. P. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 1997, 99, 338–347. [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Collins, A.M.; Coughlin, D.; Kirk, S. The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0138237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, M.; Ninnin, P.; Ten Hoopen, M.; Alvarado, J.; Cabezas Huayllas, O.; Valderrama, B.; Alguilar, G.; Perrier, C.; Dedieu, F.; Bagny Beilhe, L. The American cocoa pod borer, Carmenta foraseminis, an emerging pest of cocoa: A review. Agr. Forest. Entomol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baris, A.; Cobanoglu, S. Morphological characteristics of melon fly [Myiopardalis pardalina (Bigot, 1891) (Diptera: Tephritidae)]. J. Agric. Fac. Gaziosmanpasa Univ. 2014, 31, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Ullah, A.; Badshah, H.; Younus, M. Management of melon fruit fly (Myopardalis pardalina Bigot) In Badghis, Afghanistan. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2015, 24, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kholbekov, O.; Shakirzyanova, G.; Mamadrahimov, A.; Babayev, B.; Jumakulov, T.; Turdibayev, J. The study of allelochemicals of the melon fly (Myiopardalis pardalina Bigot.). Agric. Sci. 2023, 14, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kütük, M.; Özaslan, M. Faunistical and systematical studies on the Trypetinae (Diptera: Tephritidae) in the Turkey along with a new record to Turkish fauna. Mun. Ent. Zool. 2006, 1, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Korneyev, V.; Mishustin, R.; Korneyev, S. The Carpomyini fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) of Europe, Caucasus, and Middle East: New records of pest species, with improved keys. Vestn. Zool. 2017, 51, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Wang, J.; Pan, J.; Gao, J. Paying attention to threat of Baluchistan meIon fly to the watermelon and melon industry in Xinjiang. Plant Quar. 2024, 38, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Plant health newsletter on horizon scanning–September 2022. EFSA Supporting Publications 2022, 19, 7580E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MPI. Official New Zealand Pest Register: Pests of concern to New Zealand. Available online: https://pierpestregister.mpi.govt.nz/pests-of-concern/?scientificName=&organismType=&freeSearch=Carpomyia+pardalina. 2025.

- DSDA, U.S. Regulated plant pest table. Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/plant-imports/regulated-pest-list.

- EPPO Global Database: Myiopardalis pardalina (CARYPA). Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/CARYPA/categorization. 2025.

- Baris, A.; Cobanoglu, S. Investigation on the biology of melon fly Myiopardalis pardalina (Bigot, 1891) (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Ankara province. Turk. J. Entomol. 2013, 37, 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- CABI. Carpomya pardalina (Baluchistan melon fly). CABI Compendium 2019, 11410. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.E.E.; Abdellah, A.M.; Basher, M.I.; Mohamed, S.A.; Ekesi, S. Chronological review of fruit fly research and management practices in Sudan. In Sustainable Management of Invasive Pests in Africa. Sustainability in Plant and Crop Protection; Niassy, S., Ekesi, S., Migiro, L., Otieno, W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Harym, Y.; Belqat, B. First checklist of the fruit flies of Morocco including new records (Diptera, Tephritidae). Zookeys 2017, 702, 137–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stride, B.; Habibi, Z.; Ahmad, G. Control of melon fly (Bactrocera cucurbitae Diptera:Tephritidae) with insecticidal baits, in Afghanistan. IPC 2002, 44, 304–306. [Google Scholar]

- Falahzadah, M.H.; Karimi, J.; Gaugler, R. Biological control chance and limitation within integrated pest management program in Afghanistan. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2020, 30, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novozhilov, K.; Zhukovskii, S. The effectiveness of attractants for the melon fly Carpomyia (Myiopardalis) pardalina Big. and their prospective uses in plant protection. Byulleten' Vsesoyuznogo Nauchno-issledovatel'skogo Instituta Zashchity Rastenii 1967, 1, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rekach, V.N. Studies on the biology and control of the melon-fly Carpomyia (Myiopardalis) caucasica Zaitz. (M. pardalina Big.). CABI Databases 1930, 9, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Georghiu, G. Technical bulletin, Department of Agriculture Cyprus, 1957, No. TB-7, 22.

- Kapoor, V.C.; Agarwal, M.L.; Grewal, J.S. Zoogeography of Indian Tephritidae (Diptera). Orient. Insects 1977, 11, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.L.; Sueyoshi, M. Catalogue of Indian fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). Orient. Insects 2005, 39, 371–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, V. Taxonomy and biology of economically important fruit flies of India. Isr. J. Entomol. 2005, 35, 459–475. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, E.S.; Batra, H.K. Fruit flies and their control. Indian J. Agric. Res. Available online: https://archive.org/details/unset0000unse_u7o1/page/n15/mode/2up. 1960; 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zaka-ur-Rab, M. Host plants of the fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) of Indian subcontinent, exclusive of the subfamily Dacinae. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 1984, 81, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kashi, A.; Abedi, B. Investigation on the effects of pruning and fruit thinning on the yield and fruit quality of melon cultivars (Cucumis melo L.). Iran. J. Agric. Sci. 1998, 29, 619–626. [Google Scholar]

- Movahedi, M. Mating frequency, duration and time in Baluchistan melon fly Myiopardalis pardalina (Bigot) (Diptera: Tephritidae). Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2014, 7, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Eghtedar, E. Biology and chemical control of Myiopardalis pardalina. Appl. Entomol. Phytopathol. 1991, 58, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, J.; Darsouei, R. Presence of the endosymbiont Wolbachia among some fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) from Iran: A multilocus sequence typing approach. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2014, 17, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namin, S.M.; Korneyev, V.A. An annotated checklist of fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) of Iran. Zootaxa 2018, 4369, 377–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghaei, N. A checklist of the fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) of the province of Fars in southern Iran. Arquivos Entomolóxicos 2016, 103–117. Available online: https://www.aegaweb.com/arquivos_entomoloxicos/ae16_2016_saghaei_fruit_flies_diptera_tephritidae_fars_iran.pdf.

- Arghand, B. Dacus sp. a new pest on cucurbitaceous plants in Iran. Entomologie et Phytopathologie Appliquées 1983, 51, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Y.R. A preliminary list of insect pests of Iraq. CABI Databases 1921, 7, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saffar, H.H.; Augul, R.S.; Ali, Z.A.A. Survey of insects associated with some species of Cucurbitaceae in Iraq. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. The 7th International Conference on Agriculture, Environment, and Food Security, Medan, North Sumatera, Indonesia, 26-27 September 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gabeielith-shpan, R. Bionomics of Myiopardalis pardalina Bigot on sweet melons in Israel. In XI. Internationaler Kongress für Entomologie, August 1960.

- Win, N.Z.; Mi, D.K.M.; Oo, T.T.; Win, K.K.; Park, J.K. Species richness of fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) and incidence of Bactrocera species on mango, guava and jujube during fruiting season in Yezin area in Myanmar. In Proceedings of the Korean Society of Applied Entomology Conference 2013, Seoul, Korea, 24 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sharfuddin Khan; Chughtai, G. H.; Qamar-ul-Islam. Chemical control of melon fruit fly (Myiopardalis pardalina). Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Research 1984, 5, 40–42.

- Abdullah, K.; Latif, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, M. Field test of the bait spray on periphery of host plants for the control of the fruit fly, Myiopardalis pardalina Bigot (Tephritidae: Diptera). PE 2007, 29, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Arif, M.J.; Wakil, W.; Gogi, M.D.; Khan, R.R.; Arshad, M.; Sufyan, M.; Nawaz, A.; Ali, A.; Majeed, S. , A., Butt, M.S., Eds.; CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: New York, USA, 2018; pp. 442–510. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781351208239-21pests. In Developing Sustainable Agriculture in Pakistan.; EdSameen, A., Butt, M.S., Eds.; CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: New York, USA, 2018; Francis Group: New York, USA, 2018; pp. 442–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, E. Report of the government entomologist for the year 1st April, 1935 to 31st March, 1936. Ann. Rept. Dept. Agr. For. Palestine. 1937, 202–205. [Google Scholar]

- AlAnsari, S.M.; AlWahaibi, A.K. Fruit flies fauna, bio-ecology, economic importance and management with an overview of the current state of knowledge in the Sultanate of Oman and the Arabian Peninsula. JAMS 2024, 29, 15–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawah, H.A.; Abdullah, M.A. An overview of the Tephritidae (Diptera) of Saudi Arabia with new records and updated list of species. J. Jazan. Univ. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Najjar, H. The melon fruit fly (Myiopardalis pardalina, Big.). Circ. Inst. Rur. Life Nr. East Fdn Amer. Univ. Beirut. 1936, 8, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Saparmamedova, N. To the knowledge of the melon fly, Myiopardalis pardalina Big. (Diptera, Tephritidae) in Turkmenia. Entomol. Obozr. 2004, 83, 517–520. [Google Scholar]

- Yuldashev, L.; Djumakulov, T.; Turdibaev, Z.; Rifky, M. Application of pheromone trap against the melon fly (Miopardalis pardalina Big.) in agriculture. E3S Web of Conferences 2024, 537, 8023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaryan, G.K.; Babayan, A.S.; Mkrtumyan, K.L.; Melkonyan, T.M. On the results of tests of chemosterilants in Armenia. CABI Databases, https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/19720503214. 1969; 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Prokudina, F.V.; Shevchenko, V.V. Protection of cucurbitaceous crops. Zasch. Rast. 1983, 4, 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- Baris, A.; Cobanoglu, S.; Babaroglu, N.E. Effect of fruit size on egg laying and damage type of Baluchistan melon fly [Myiopardalis pardalina (Bigot, 1891) (Diptera: Tephritidae)]. Plant Prot. Bul. 2019, 59, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giray, H. A preliminary list of the fauna of Turkish Trypetidae (Diptera). Turk. Bit. Kor. Derg. 1979, 3, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram, Y.; Bayhan, S.; Bayhan, E. Some biological parameters of melon fly Myiopardalis pardalina (Bigot 1891) (Diptera: Tephritidae) a major pest of melons in Turkey. IJAAS 2019, 4, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Alabouid, A.; Bayhan, E. Determination of the loss ratio on some melon varieties from the melon fly, Myiopardalis pardalina (Bigot, 1891) (Diptera: Tephritidae). JOTAF 2022, 19, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabouid, A.; Bayhan, E.; Gozel, U. The efficacy of entomopathogenic nematodes against Myiopardalis pardalina (Bigot, 1891) (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Turkey. Turkiye Biyol. Mucadele Derg. 2019, 10, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneyev, V. On the checklist of Ukrainian Diptera Tephritoidea: Tephritidae. Ukrainska Entomofaunistyka 2024, 15, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giray, H. Investigations on the species and the food-plants of the family Trypetidae (fruit-flies) attacking cultivated plants in the Aegean region. Ege. Univ. Zir. Fak. Yaym. 1966, 126, 61. [Google Scholar]

- EPPO. Outbreaks of Myiopardalis pardalina (Baluchistan melon fly) in Central Asia: Addition to the EPPO alert list. EPPO Global Database https://gd.eppo.int/reporting/article-2590. 2013, 128. [Google Scholar]

- Cleghorn, J. Melon culture in Peshin, Baluchistan, and some account of the melon-fly pest. Indian J. Agric. Res. 1914, 9, 124–140. [Google Scholar]

- Janjua, N.A. Biology of the melon fly, Myiopardalis pardalina Big. (Trypetidae) in Baluchistan. Indian J. Entomol. 1954, 16, 227–233. [Google Scholar]

- Giray, H. Studies on the bionomics of the melon fly in the vicinity of Elazig. CABI Databases 1961, 43, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Baris, A.; Cobanoglu, S.; Cavusoglu, S. Determination of changes in tastes of Ipsala and Kırkagac melons against melon fly [Myiopardalis pardalina (Bigot, 1891) (Diptera: Tephritidae)]. Derim 2016, 33, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. Myiopardalis pardalina. Insects not known to occur in the United States. APHIS–USDA. 1957.

- Manukyan, G. Reducing fruit damage by Myiopardalis pardalina. Kartofel. Ovoshchi 1974, 7, 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.; Guo, W.; Ding, X.; Fu, K.; Yang, D.; Jia, Z.; Wang, X.; Liang, L.; Tu er xun, A.; Wang, J.; Gao, J. RPA-CRISPR/Cas-Based Detection Kit and Protocol for Myiopardalis pardalina. Chinese Invention Patent 2024: CN202410634082.9 2024.

- Rao, Q.; Guo, X.; Fu, K.; Deng, J.; Xu, F.; Ding, X.; Guo, W. Visual lamp-assisted identification of Myiopardalis pardalinae: Methodology and practical implementation. Chinese Invention Patent 2024: CN202410813785.8 2024.

- Dias, N.P.; Zotti, M.J.; Montoya, P.; Carvalho, I.R.; Nava, D.E. Fruit fly management research: A systematic review of monitoring and control tactics in the world. Crop Protection 2018, 112, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madiyarovich, S.S.; Qadamboy qizi, K.S. Study of the effectiveness of the drug Belmak 5% em. K against melon fly (Carpomya pardalina Bigot) in the conditions of the Khorezm region. EduVision 2025, 1, 614–618. [Google Scholar]

- Shahriari, M.; Sarani, M. Study on susceptibility of four cultivars of melon to melon fruit fly Myiopardalis pardalina in Sistan region. Plant Pest Res. 2024, 14, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckmann, E.; Köppler, K.; Hummel, E.; Vogt, H. Bait spray for control of European cherry fruit fly: An appraisal based on semi-field and field studies. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014, 70, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivezić, A.; Trudić, B.; Stamenković, Z.; Kuzmanović, B.; Perić, S.; Ivošević, B.; Buđen, M.; Petrović, K. Drone-related agrotechnologies for precise plant protection in western Balkans: Applications, possibilities, and legal framework limitations. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, Z.J.; Banik, A.; Robin, T.B.; Chowdhury, M.R. Deciphering the potential of plant metabolites as insecticides against melon fly Zeugodacus cucurbitae: Exposing control alternatives to assure food security. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kariyanna, B.; Sowjanya, M. Unravelling the use of artificial intelligence in management of insect pests. Smart Agr. Technol. 2024, 8, 100517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, N.P.; Montoya, P.; Nava, D.E. A 30-year systematic review reveals success in tephritid fruit fly biological control research. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2022, 170, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yu, Z.; He, X.Z.; Zhou, G.; Guo, M.; Deng, J. Attraction of the Indian meal moth Plodia interpunctella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) to commercially available vegetable oils: Implications in integrated pest management. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Lan, C.; Zhou, J.; Yao, Y.; Yin, X.; Fu, K.; Ding, X.; Guo, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, N.; Wang, F. Analysis of sex pheromone production and field trapping of the Asian corn borer (Ostrinia furnacalis Guenée) in Xinjiang, China. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Guo, M.; Deng, J. Inhibition effect of non-host plant volatile extracts on reproductive behaviors in the diamondback moth Plutella xylostella (Linnaeus). Insects 2024, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Shen, Z.; Wang, F.; Liu, T.; Hong, W.; Fang, M.; Wo, L.; Chu, S. Enhancement of attraction to sex pheromone of Grapholita molesta (Busck) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) by structurally unrelated sex pheromone compounds of Conogethes punctiferalis (Guenée) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2022, 25, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Aumann, R.A.; HÄCker, I.; Schetelig, M.F. CRISPR-based genetic control strategies for insect pests. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilez-Molina, A.I.; Niño Sanchez, J.; Merino, D. The role of polymers in enabling RNAi-based technology for sustainable pest management. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).